Configurational Entropy in Intermolecular Interactions: From Theory to Application in Drug Design

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the critical role configurational entropy plays in governing intermolecular interactions, with a specific focus on biomedical and pharmaceutical applications.

Configurational Entropy in Intermolecular Interactions: From Theory to Application in Drug Design

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the critical role configurational entropy plays in governing intermolecular interactions, with a specific focus on biomedical and pharmaceutical applications. It explores the fundamental thermodynamic principles that define configurational entropy and its relationship to binding free energy. The scope extends to contemporary computational and experimental methodologies for its quantification, strategies to overcome ubiquitous challenges such as enthalpy-entropy compensation, and validation through case studies in successful drug optimization. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes foundational knowledge with cutting-edge applications to guide the rational design of high-affinity molecular binders.

The Thermodynamic Pillar: Defining Configurational Entropy and Its Role in Binding Free Energy

This technical guide explores the fundamental roles of enthalpy and entropy in driving molecular interactions, with a specific focus on the critical contribution of configurational entropy in biomolecular binding processes. For researchers in drug development, understanding this delicate balance is paramount for overcoming challenges such as enthalpy-entropy compensation and for designing high-affinity therapeutic compounds. This whitepaper synthesizes current research findings, presents quantitative data on entropy changes, details experimental methodologies for its measurement, and provides visual tools for conceptualizing these complex thermodynamic relationships.

Core Thermodynamic Principles

The Gibbs free energy change (ΔG) dictates the spontaneity of molecular binding events and is described by the fundamental equation:

ΔG = ΔH - TΔS

Where ΔH is the change in enthalpy, T is the absolute temperature, and ΔS is the change in the total entropy of the system. A negative ΔG indicates a favorable reaction. The total entropy change (ΔS_system) comprises both solvent entropy and the configurational entropy of the solute molecules themselves [1]. Configurational entropy is the portion of a system's entropy related to the number of discrete representative positions or conformations its constituent particles can adopt [2].

For a system, the configurational entropy can be calculated using the Gibbs entropy formula: S = -kB * Σ(Pn * ln Pn) where kB is the Boltzmann constant and P_n is the probability of the system being in state n out of W possible states [2].

The Critical Role of Configurational Entropy in Biomolecular Binding

Traditionally, the driving force for non-covalent binding was attributed predominantly to favorable enthalpy changes (ΔH) and solvent entropy gains. However, recent experimental and computational studies demonstrate that the loss of configurational entropy upon binding is a major and often unfavorable term that must be overcome [1] [3].

When a receptor and ligand bind, their motions become restricted, leading to a significant loss of configurational entropy. This entropy penalty can be of similar magnitude to the solvent entropy contribution and thus critically influences the overall binding affinity [1]. For example, in protein-ligand binding, this entropy loss can contribute a free energy penalty on the order of 14 kcal mol⁻¹, a substantial value on the scale of typical binding free energies [3]. The table below summarizes key quantitative findings from recent research.

Table 1: Quantified Configurational Entropy Changes in Protein Interactions

| Protein/Complex System | Key Finding on Configurational Entropy | Magnitude / Impact |

|---|---|---|

| General Protein Binding | Total configurational entropy change (ΔS_conf) is a central constituent of the free energy change (ΔG) [1]. | Similar magnitude to solvent entropy contribution [1]. |

| Tsg101 / PTAP Peptide Binding | First-order MIE approximation of entropy change (neglecting correlations) [3]. | Free energy penalty of 14 kcal mol⁻¹ (12 from protein, 2 from ligand) [3]. |

| Ubiquitin Complexes (e.g., 1S1Q, 1YD8) | Unfavorable entropy change from internal degrees of freedom without coupling terms (-TΔS_1D) [1]. | Ranges from 44.0 to 527.4 kJ mol⁻¹ per partner, showing system-dependent variability [1]. |

| Protein-Ligand Binding | Change in pairwise correlation is a major contributor to the total computed change in configurational entropy [3]. | Major contribution to overall entropy loss [3]. |

Decomposing Configurational Entropy: Insights from Mutual Information Expansion

The Mutual Information Expansion (MIE) provides a powerful, systematic framework for dissecting the total configurational entropy into contributions from individual molecular degrees of freedom and their correlations [3]. The second-order MIE approximation is given by:

S ≈ S^(2) = Σ Si - Σ Iij

where Si is the entropy of the i-th degree of freedom, and Iij is the mutual information between coordinates i and j, which accounts for both linear and nonlinear correlations [3].

Applying this analytical framework reveals that contrary to traditional assumptions, coupling terms between internal and external degrees of freedom contribute significantly to the overall configurational entropy change upon binding [1]. This decomposition is vital for a precise understanding of binding thermodynamics.

Experimental and Computational Protocols

Molecular Dynamics (MD) with MIE/MIST Analysis

This protocol is used to calculate configurational entropy changes from atomistic simulations [1] [3].

- System Preparation: Construct the all-atom model of the free binding partners and their bound complex using a molecular modeling suite. Solvate the systems in an explicit water box and add ions to neutralize the charge.

- Equilibration: Run a series of MD simulations, first relaxing the solvent and ions, then the entire system, under NPT (constant Number of particles, Pressure, and Temperature) conditions to achieve stable temperature, density, and potential energy.

- Production Simulation: Perform microsecond-long MD simulations for each state (free and bound) to ensure adequate sampling of conformational space. Multiple independent replicates (MMDS) are recommended to improve statistical reliability [3].

- Trajectory Analysis in BAT Coordinates: Convert the Cartesian coordinates from the MD trajectories into internal Bond-Angle-Torsion (BAT) coordinates.

- Entropy Calculation: Apply the Maximum Information Spanning Tree (MIST) algorithm or the second-order MIE approximation to the BAT coordinate trajectories. This yields the total configurational entropy and its decomposition into uncoupled and coupling terms for each state [1].

- Calculate Change: The configurational entropy change of binding (ΔS_conf) is the difference between the entropy of the complex and the sum of the entropies of the isolated partners.

NMR Spectroscopy-Based Estimation

This method uses experimental data to estimate changes in molecular flexibility.

- Sample Preparation: Prepare isotopically labeled samples of the free protein and the protein-ligand complex.

- NMR Data Collection: Conduct NMR relaxation experiments (e.g., measuring T1, T2, and NOE) to determine generalized order parameters (S²) for backbone N-H bond vectors.

- Entropy Estimation: Relate the order parameters to conformational entropy using a model, such as the "diffusion-in-a-cone" model. The entropy is inversely related to the order parameter (higher S² indicates less motion and lower entropy) [3].

- Limitation: This approach typically provides an estimate based on internal degrees of freedom only and may not account for all correlation effects [1] [3].

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Configurational Entropy Studies

| Item / Resource | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Molecular Dynamics Software (e.g., GROMACS, AMBER, NAMD) | Performs all-atom simulations to generate conformational ensembles of molecules and complexes. |

| MIE/MIST Analysis Code (e.g., custom parallel implementations) | Computes configurational entropy and its components from MD simulation trajectories [1]. |

| Isotopically Labeled Proteins (¹⁵N, ¹³C) | Essential for NMR relaxation experiments to measure dynamics and order parameters. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | Provides the computational power required for microsecond-scale MD simulations and subsequent entropy analysis. |

| Force Fields (e.g., CHARMM, AMBER) | Defines the potential energy functions and parameters governing interatomic interactions in MD simulations. |

Implications for Drug Discovery and Development

The insights from configurational entropy research directly impact rational drug design.

- Overcoming Enthalpy-Entropy Compensation: This common phenomenon, where optimizing favorable enthalpy leads to a compensating loss of entropy (or vice versa), is a major hurdle. A detailed understanding of entropy contributions can guide strategies to mitigate this effect [1].

- Identifying "Entropy Hotspots": MIE analysis can pinpoint specific molecular degrees of freedom (e.g., key torsional angles) that lose the most entropy upon binding. This information can be used to design ligands that pre-organize into the bioactive conformation, reducing the entropic penalty paid upon binding.

- Stabilizing Specific Protein Dynamics: In some cases, a ligand might increase the flexibility (and thus entropy) of the receptor in specific modes, which can be a mechanism for high-affinity binding [3]. Targeting such dynamics is a sophisticated design strategy.

- Amorphous Pharmaceutical Formulations: The high configurational entropy of amorphous drugs compared to their crystalline counterparts is a key factor in their enhanced solubility. However, this same property provides the thermodynamic driving force for recrystallization, which is a primary stability challenge. Understanding this balance is critical for formulating stable amorphous solid dispersions [4].

Configurational entropy is a fundamental thermodynamic property originating from the disorder inherent in the spatial and energetic degrees of freedom of molecules. In biomolecular interactions, particularly noncovalent binding events, the change in configurational entropy constitutes a central component of the free energy change, profoundly influencing binding affinity and specificity. Despite its significance, configurational entropy remains challenging to quantify experimentally or computationally. This whitepaper provides an in-depth examination of configurational entropy's theoretical foundations, presents advanced computational methodologies for its dissection, and discusses its critical implications for rational drug design, where overcoming enthalpy-entropy compensation is a pivotal challenge.

Configurational entropy is the component of total entropy that arises specifically from the number of distinct spatial arrangements accessible to a molecule's atoms, excluding contributions from solvent molecules [1]. In the context of noncovalent interactions between biomacromolecules—processes fundamental to transcription, translation, and cell signaling—the change in configurational entropy (ΔS_conf) upon binding represents a substantial contribution to the overall Gibbs free energy change (ΔG) [1].

Traditional assumptions held that configurational entropy change was negligible compared to solvent entropy changes in biomolecular interactions. However, experimental evidence now demonstrates that configurational entropy contributions in proteins can be of similar magnitude to solvent entropy contributions, potentially exerting a strong influence on interaction thermodynamics [1]. This recognition has significant applied implications, as deeper insight into configurational entropy and the physical principles governing its response to biomolecular dynamics could substantially improve computational drug design by helping to overcome persistent enthalpy/entropy compensation effects [1].

The theoretical framework for configurational entropy derives from the quasi-classical entropy integral. For a single molecule or complex, configurational entropy can be expressed as [1]: $$S_{config} = -R \int \rho(\vec{q}) \ln [h^{3N} J(\vec{q}) \rho(\vec{q})] d\vec{q} + R \ln (8\pi^2 V^\circ)$$ Where R is the universal gas constant, h is Planck's constant, N is the number of atoms, ρ is the classical phase-space probability density function, $\vec{q}$ represents spatial degrees of freedom, J($\vec{q}$) denotes the Jacobian of the chosen internal coordinates, and V° is the standard concentration volume.

Theoretical Framework and Decomposition

Molecular Degrees of Freedom

The configurational entropy of a biomolecule can be conceptually and mathematically decomposed into contributions from different classes of molecular degrees of freedom:

- Internal degrees of freedom: These include bond stretching, angle bending, and torsional rotations, typically described in Bond-Angle-Torsion (BAT) coordinates or anchored Cartesian coordinates [1].

- External (rigid body) degrees of freedom: These comprise rotational and translational motions of the molecule as a whole [1].

- Coupling terms: These account for correlations and mutual information between internal and external degrees of freedom [1].

A comprehensive framework for this decomposition employs Mutual Information Expansion (MIE) in its analytical form, which enables dissection of the configurational entropy change of binding into contributions from molecular internal and external degrees of freedom while accounting for all coupled and uncoupled contributions [1].

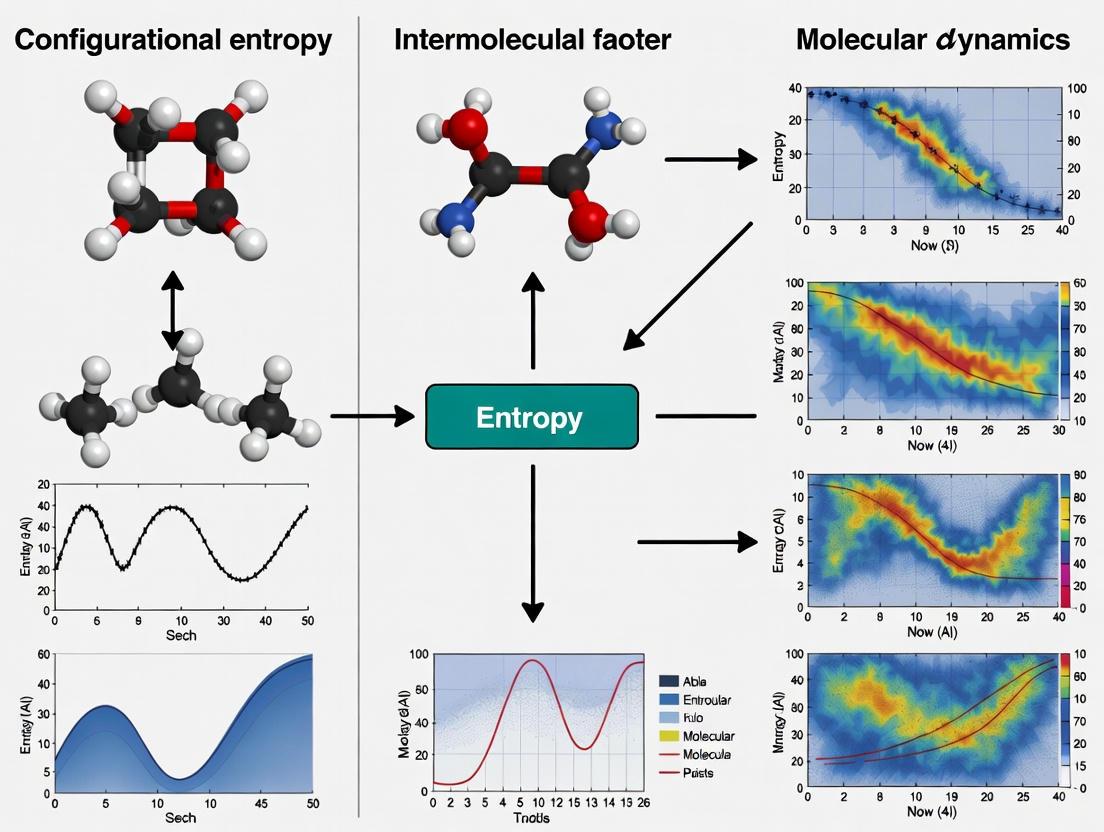

Entropy Decomposition Framework

The following diagram illustrates the analytical framework for decomposing configurational entropy into its constituent components, accounting for couplings between different degrees of freedom:

Contrary to commonly accepted assumptions, different coupling terms contribute significantly to the overall configurational entropy change in protein binding processes [1]. While the magnitude of individual terms may be largely unpredictable a priori, the total configurational entropy change can often be approximated by rescaling the sum of uncoupled contributions from internal degrees of freedom only, providing theoretical support for NMR-based approaches to configurational entropy change estimation [1].

Computational Methodologies and Protocols

Maximum Information Spanning Tree (MIST) Algorithm

The Maximum Information Spanning Tree (MIST) algorithm represents a sophisticated approach for configurational entropy calculation from molecular dynamics simulations [1]. This method, which can be considered a variant of Mutual Information Expansion (MIE), enables efficient approximation of the high-dimensional integrals required for entropy computation.

Protocol Implementation:

- Trajectory Generation: Perform microsecond-level classical molecular dynamics simulations of both isolated binding partners and their binary complexes [1].

- Coordinate Transformation: Convert Cartesian coordinates to internal coordinates (typically BAT coordinates) to separate internal and external degrees of freedom [1].

- Probability Density Estimation: Compute marginal and joint probability distributions for all degrees of freedom from simulation trajectories.

- Mutual Information Calculation: Determine mutual information between all pairs of degrees of freedom.

- Spanning Tree Construction: Build the maximum information spanning tree that connects all degrees of freedom while maximizing total mutual information.

- Entropy Computation: Calculate configurational entropy using the MIST approximation, which decomposes the total entropy into individual and pairwise correlated contributions.

Recent parallel implementations of the MIST algorithm have enabled comprehensive numerical analysis of individual contributions to configurational entropy change across extensive sets of protein binding processes [1].

Dynamic Disorder in Molecular Crystals

Beyond biomolecules in solution, computational approaches also address dynamic disorder in molecular crystals, where molecular segments or entire molecules exhibit large-amplitude motions [5]. These methods sample potential energy surfaces to model atomic displacements related to disorder and quantify contributions of internal dynamics to macroscopic material properties.

Computational Workflow for Dynamic Disorder Analysis:

- Potential Energy Surface Mapping: Identify flat potential energy basins related to dynamic degrees of freedom using quantum chemical calculations [5].

- Anharmonicity Assessment: Evaluate the extent of anharmonicity in dynamic degrees of freedom through potential energy profile analysis along libration modes [5].

- Thermodynamic Integration: Incorporate anharmonic models (e.g., hindered rotor models) into quasi-harmonic treatment of thermodynamic properties [5].

- Property Prediction: Calculate contributions of dynamic disorder to entropy, volatility, solubility, and other material properties [5].

For caged molecules with rotational disorder, such as adamantane and diamantane derivatives, this approach has revealed significant additional entropy contributions due to dynamic disorder originating from phonon anharmonicity [5].

Quantitative Analysis of Configurational Entropy

Protein Binding Entropy Changes

Computational studies on extensive sets of protein complexes have quantified the magnitude of configurational entropy changes and their components in biological binding processes. The table below summarizes representative data from molecular dynamics simulations of protein binding processes, highlighting the significant variation in entropy contributions across different systems:

Table 1: Configurational Entropy Changes in Protein Binding Processes

| Protein System | PDB Code | Uncoupled Internal Entropy Change (-TΔS_1D) | Total Atoms in Complex | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tsg101/Ubiquitin | 1S1Q | 190.0 kJ/mol (Tsg101) | 2,240 | Different coupling terms contribute significantly to total entropy change |

| gGGA3 Gat/Ubiquitin | 1YD8 | 44.0 kJ/mol (gGGA3) | 1,709 | Magnitude of individual terms largely unpredictable a priori |

| Subtilisin/Ovomucoid | 1R0R | 527.4 kJ/mol (Subtilisin) | 2,931 | Total entropy change approximatable by rescaling uncoupled internal contributions |

| Uracil-DNA Glycosylase/Inhibitor | 1UGH | -65.7 kJ/mol (Glycosylase) | 3,121 | Supports NMR-based entropy estimation approaches |

The data reveal several important patterns. First, the magnitude of uncoupled internal entropy changes varies substantially across different protein systems, ranging from strongly favorable to slightly unfavorable contributions. Second, the data demonstrate that different coupling terms contribute significantly to the overall configurational entropy change, contrary to commonly accepted assumptions in the field. Finally, despite the complexity of these contributions, the total configurational entropy change can often be approximated by rescaling the sum of uncoupled contributions from internal degrees of freedom, providing support for experimental NMR-based approaches to configurational entropy estimation [1].

Dynamic Disorder Entropy Contributions

In molecular crystals, computational studies have quantified the entropy contributions from dynamic disorder, particularly in systems exhibiting rotational freedom or large-amplitude motions:

Table 2: Entropy Contributions from Dynamic Disorder in Molecular Crystals

| Material Class | Representative Compound | Energy Barrier for Rotation | Entropy Contribution from Dynamic Disorder | Experimental Manifestation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caged Hydrocarbons | Diamantane | 4-8 kJ/mol | Significant additional contributions beyond harmonic model | Plastic crystal behavior, barocaloric effects |

| Pharmaceutical Compounds | Various APIs | System-dependent | Affects solubility, stability, and polymorphism | Altered dissolution rates, phase transformations |

| Organic Semiconductors | Various OSCs | System-dependent | Influences charge carrier mobility | Temperature-dependent conductivity |

For diamantane, calculations show rotational energy barriers of 4-8 kJ/mol, which are comparable to thermal energy at ambient conditions (≈2.5 kJ/mol), justifying the need for explicitly anharmonic models. The additional entropy contributions from dynamic disorder in such systems significantly impact material properties including volatility, solubility, and charge transport characteristics [5].

Research Reagent Solutions Toolkit

The computational analysis of configurational entropy requires specialized software tools and theoretical frameworks. The following table details essential "research reagents" for investigating configurational entropy in molecular systems:

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Configurational Entropy Research

| Tool/Algorithm | Type | Primary Function | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maximum Information Spanning Tree (MIST) | Algorithm | Approximates configurational entropy from molecular dynamics trajectories | Protein binding entropy changes, allosteric regulation studies |

| Mutual Information Expansion (MIE) | Theoretical Framework | Decomposes entropy into correlated and uncoupled contributions | Entropy component analysis, coupling term quantification |

| Molecular Dynamics Simulations | Computational Method | Generates conformational ensembles for entropy calculation | Biomolecular dynamics, binding free energy calculations |

| Hindered Rotor Model | Theoretical Model | Treats anharmonic rotational degrees of freedom | Dynamic disorder in molecular crystals, plastic crystal behavior |

| Bond-Angle-Torsion (BAT) Coordinates | Coordinate System | Separates internal and external degrees of freedom | Entropy decomposition, internal coordinate analysis |

These computational tools enable researchers to move beyond simplistic harmonic approximations and address the complex, anharmonic nature of molecular motions that contribute to configurational entropy in both biomolecular systems and molecular materials.

Implications for Intermolecular Interactions Research

Drug Design and Discovery

In rational drug design, accurate accounting of configurational entropy changes upon binding is crucial for predicting binding affinities and optimizing lead compounds. The recognition that configurational entropy can be similar in magnitude to solvent entropy contributions necessitates more sophisticated computational approaches that properly account for entropy changes in both binding partners [1].

The decomposition of configurational entropy into internal, external, and coupling components provides insights for structure-based drug design. For instance, strategies that restrict flexible moieties in drug candidates may reduce unfavorable entropy losses upon binding, while targeting rigid regions of protein binding sites may minimize entropy penalties.

Material Science Applications

Beyond biomolecular interactions, understanding and controlling configurational entropy has important implications for material design:

- Barocaloric materials: Caged molecules with rotational disorder exhibit significant entropy changes under pressure, enabling solid-state cooling applications [5].

- Pharmaceutical solids: Dynamic disorder in active pharmaceutical ingredients affects solubility, stability, and bioavailability, with metastable disordered forms often exhibiting enhanced dissolution rates [5].

- Organic semiconductors: Configurational entropy influences charge transport properties through its effect on molecular dynamics and disorder in the solid state [5].

Configurational entropy, originating from the disorder in molecular degrees of freedom, represents a fundamental thermodynamic property with far-reaching implications across biochemistry, drug discovery, and materials science. Advanced computational frameworks that decompose configurational entropy into internal, external, and coupling components provide crucial insights into the molecular determinants of entropy changes in binding processes and phase behaviors.

The integration of sophisticated algorithms like MIST with molecular dynamics simulations has enabled quantitative analysis of configurational entropy contributions across diverse systems, from protein-protein interactions to dynamically disordered molecular crystals. These approaches reveal the significant role of correlation terms often neglected in simplified treatments and provide a more complete picture of the entropy changes driving molecular recognition and assembly.

As computational methodologies continue to advance, incorporating increasingly accurate treatments of anharmonicity and dynamic disorder, our ability to predict and manipulate configurational entropy will further enhance rational design in pharmaceutical development and materials engineering. The integration of these computational insights with experimental approaches promises to unlock new opportunities for controlling molecular interactions through entropy engineering.

The binding affinity and spontaneity of intermolecular interactions, a cornerstone in drug discovery and molecular biology, are governed by the delicate balance of enthalpic and entropic forces as defined by the Gibbs free energy equation, ΔG = ΔH - TΔS. While often overshadowed by the more intuitive concept of enthalpy, the loss of configurational entropy (ΔSconf) of a ligand upon binding to its protein target frequently constitutes the primary thermodynamic barrier to association. This in-depth technical guide explores the central, and often decisive, role of ΔSconf in spontaneous binding. We elucidate the theoretical underpinnings, detail advanced computational and experimental methodologies for its quantification, and present quantitative data from seminal studies. Framed within the context of a broader thesis on the role of configurational entropy in intermolecular interactions research, this review provides researchers and drug development professionals with the foundational knowledge and practical protocols necessary to navigate and leverage this critical thermodynamic parameter.

Molecular recognition, the specific and reversible binding between a protein and a ligand, is fundamental to virtually all biological processes, from enzyme catalysis to cellular signaling [6]. The formation of a protein-ligand complex is a spontaneous process only if the associated change in Gibbs free energy (ΔG) is negative. The Gibbs free energy equation, ΔG = ΔH - TΔS, elegantly partitions this energy into its constituent drivers: the change in enthalpy (ΔH), representing the net strength of molecular interactions, and the change in entropy (TΔS), representing the net change in system disorder, scaled by temperature [7]. A deep understanding of this equation is paramount for rational drug design, where the goal is to engineer ligands that achieve a highly negative ΔG.

The entropic term, -TΔS, is multifaceted. The total entropy change upon binding, ΔS_total, is a composite of several contributions:

- Configurational Entropy (ΔS_conf): The loss of rotational and translational freedom of the ligand upon moving from a 3D solution to a confined binding pocket, coupled with a reduction in the conformational flexibility of both the ligand and the protein.

- Solvation Entropy (ΔS_solv): The change in the entropy of the water molecules surrounding the binding partners, often a major favorable driving force due to the release of ordered water molecules from the interface into the bulk solvent [8].

This guide focuses on ΔSconf, a quantity that is almost always unfavorable for binding (i.e., ΔSconf < 0) as the ligand loses degrees of freedom. Overcoming this large entropic penalty is a key challenge. In many cases, a sufficiently favorable, negative ΔH (e.g., from strong electrostatic or van der Waals interactions) or a highly favorable, positive ΔSsolv (from the hydrophobic effect) compensates for the configurational entropy loss. In certain systems, however, binding is entropy-driven, where a small ΔH is overcome by a large, favorable ΔSsolv, resulting in a negative ΔG [9] [6]. The following sections dissect the mechanisms, calculations, and experimental implications of this critical parameter.

Theoretical Framework: Deconstructing Configurational Entropy

The Statistical Mechanical Perspective

From a statistical mechanics viewpoint, entropy is a measure of the number of microscopic states, or microstates, accessible to a system. Configurational entropy is directly related to the probability distribution of a molecule's conformations. For a discrete set of states, it can be expressed as ( S{conf} = -kB \sum pi \ln pi ), where ( kB ) is Boltzmann's constant and ( pi ) is the probability of the system being in microstate i [10]. Upon binding, the diversity of accessible conformational states for the ligand and sometimes the protein active site is drastically reduced, leading to a significant decrease in Sconf and thus a negative ΔSconf.

The Thermodynamic Cycle and Absolute Binding Free Energy

The "double-decoupling method" provides a rigorous statistical mechanical framework for calculating absolute binding free energies (ΔG_bind) and decomposing them into entropic and enthalpic components [9]. This alchemical approach uses a thermodynamic cycle to avoid simulating the physical association process. The ligand is first decoupled from bulk solvent, followed by being coupled into the protein binding site in a series of non-physical steps. The absolute binding free energy is calculated as:

ΔGbind = ΔGgas→complex + ΔG_gas→gas - ΔG_gas→water [9]

Here, ΔG_gas→gas* is the free energy cost of restraining the ligand's position and orientation in the gas phase, which directly relates to the loss of its external (translational and rotational) entropy. The entropic component TΔS can be obtained from the temperature dependence of the free energy using the relationship ΔS = -(∂ΔG/∂T) [9].

Table 1: Key Entropic Contributions in Protein-Ligand Binding

| Entropic Component | Typical Sign upon Binding | Physical Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Ligand Translational Entropy | Unfavorable (Negative ΔS) | Loss of 3D translational freedom in solution. |

| Ligand Rotational Entropy | Unfavorable (Negative ΔS) | Loss of rotational freedom in solution. |

| Ligand Conformational Entropy | Unfavorable (Negative ΔS) | Reduction in the number of accessible bond rotations and angles. |

| Protein Conformational Entropy | Unfavorable (Negative ΔS) | Reduction in the flexibility of the protein's side chains or backbone upon ligand binding. |

| Solvent Reorganization Entropy | Favorable (Positive ΔS) | Gain in entropy from the release of ordered water molecules from the binding pocket and ligand surface into the bulk solvent. |

The diagram below illustrates the thermodynamic cycle and key entropy changes involved in the double-decoupling method for calculating absolute binding free energy.

Computational Protocols for Quantifying ΔS_conf

Accurately calculating configurational entropy is a significant challenge in computational chemistry. Below are detailed protocols for two prominent methods.

The Double-Decoupling Method (DDM) with MD Simulations

The DDM, also known as alchemical free energy simulation, is considered a gold standard for calculating absolute binding free energies and their entropic components [9].

Detailed Protocol:

System Preparation: Obtain the atomic coordinates of the protein-ligand complex from a database like the PDB. Parametrize the ligand using tools like

antechamber(GAFF force field) and the protein/water using a standard force field (e.g., AMBER, CHARMM). Solvate the complex in a water box (e.g., TIP3P) and add ions to neutralize the system.Equilibration: Perform energy minimization to remove steric clashes. Heat the system to the target temperature (e.g., 300 K) and equilibrate first with positional restraints on heavy atoms, followed by a full unrestrained equilibration run under constant pressure (NPT ensemble).

Production MD for Bound State: Run a long-scale (e.g., >100 ns) molecular dynamics simulation of the fully solvated complex in the NPT ensemble. Save snapshots at regular intervals (e.g., 100 ps) for analysis.

Alchemical Transformation - Decoupling from Water:

- The ligand in a water box is gradually decoupled from its environment. Its interactions with water are "turned off" in a series of windows (e.g., λ = 0.0, 0.1, ..., 1.0).

- At each λ window, perform extensive sampling (MD/MC) to calculate the free energy change (ΔG_gas→water) using methods like Thermodynamic Integration (TI) or Free Energy Perturbation (FEP).

Alchemical Transformation - Coupling to Protein:

- The ligand, now in the gas phase, is gradually coupled into the protein binding site. Its interactions with the protein and any bound waters are "turned on" across similar λ windows.

- Critical Step: Apply harmonic restraints to the ligand's center of mass to prevent it from drifting away from the binding site when its interactions are weak. The free energy cost of applying these restraints (ΔG_gas→gas*) is calculated analytically and accounts for the loss of translational and rotational entropy [9].

- Calculate the free energy change (ΔG_gas*→complex) for this leg.

Entropy Calculation:

- To extract the total binding entropy (TΔS), repeat the entire DDM process at multiple temperatures (e.g., 290 K, 300 K, 310 K).

- Use finite differences to compute the derivative: ΔSbind = - (ΔGbind(T2) - ΔG_bind(T1)) / (T2 - T1) [9].

The MM/GBSA Method and Normal Mode Analysis

MM/GBSA (Molecular Mechanics/Generalized Born Surface Area) is a more efficient, but less rigorous, end-point method that estimates binding free energy from snapshots of an MD simulation of the complex.

Detailed Protocol:

Generate Trajectory: Run an MD simulation of the protein-ligand complex, as described in Steps 1-3 of the DDM protocol.

Post-Processing and Truncation:

- Extract hundreds or thousands of snapshots from the stable part of the trajectory.

- To make entropy calculation feasible, truncate the system. A common strategy is to include only the ligand and all protein residues within a certain cutoff (e.g., 8-16 Å) from the ligand's center of mass [11]. A more advanced method involves creating a single, connected component that preserves the biological interface.

Calculate Energy Components:

- For each snapshot, the gas-phase energy (ΔE_MM) is calculated using molecular mechanics force fields.

- The solvation free energy (ΔGsolv) is decomposed into polar (ΔGpol) and non-polar (ΔG_nonpol) components. The polar term is computed by solving the Generalized Born (GB) equation, while the non-polar term is often estimated from the solvent-accessible surface area (SASA).

Entropy Calculation with Normal Mode Analysis (NMA):

- Perform NMA on a subset of snapshots (or an average structure) from the truncated system.

- NMA calculates the vibrational frequencies of the system, from which the configurational entropy (quasiharmonic approximation) is derived using statistical mechanics formulae.

- Note: This calculation is computationally expensive and is often the bottleneck. Studies show that a significant reduction in the number of snapshots used for NMA may not drastically affect accuracy but can greatly lower computation time [11].

Final Binding Free Energy Calculation:

- The final estimate is an average over all snapshots: ΔGbind = ΔEMM + ΔGsolv - TΔSconf

Table 2: Comparison of Computational Methods for ΔS_conf Calculation

| Method | Theoretical Basis | Advantages | Disadvantages | Typical Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Double-Decoupling Method (DDM) | Statistical Mechanics / Alchemical Pathway | High theoretical rigor; Can decompose entropy explicitly; Gold standard for absolute ΔG. | Extremely computationally expensive; Convergence can be slow (error ≥2 kcal/mol [9]); Complex setup. | Detailed mechanistic studies of high-affinity drug candidates. |

| MM/GBSA with NMA | End-point / Empirical Solvation | Much faster than DDM; Provides energy decomposition; Suitable for larger systems. | Relies on quasiharmonic approximation, which can be inaccurate; Sensitive to truncation method; Less rigorous. | High-throughput virtual screening and binding pose ranking. |

| k-th Nearest Neighbor (kNN) | Information Theory / Density Estimation | Can provide absolute entropy from MD ensembles; Accounts for correlated motions. | Requires high-dimensional sampling; Can be sensitive to parameters. | Analyzing conformational entropy in protein folding and flexibility. |

Case Studies and Quantitative Data

HIV-1 Protease Inhibitors: A Tale of Two Thermodynamics

A classic example highlighting the role of entropy is the binding of inhibitors to HIV-1 protease. Calculations using the DDM revealed stark contrasts:

- Nelfinavir (NFV): Binding is entropy-driven. The calculated ΔG_bind was in general agreement with experiment, showing a large favorable entropy change. This was attributed to a very favorable desolvation entropy (release of water from the hydrophobic binding site) that overwhelmingly compensated for the configurational entropy loss [9].

- Amprenavir (APV): Binding is driven by both enthalpy and entropy. The entropy change, while still favorable, was much less so than for Nelfinavir. The decomposition showed that Amprenavir binding benefited more from strong electrostatic interactions with the protein (enthalpy) [9].

Table 3: Experimental and Calculated Binding Energetics for HIV-1 Protease Inhibitors

| Ligand | Experimental ΔG_bind (kcal/mol) | Calculated ΔG_bind (kcal/mol) | Driving Force | Key Entropic Insight from Calculation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nelfinavir (NFV) | ~ -12.5 [9] | ~ -12 to -16 [9] | Primarily Entropy | Large favorable desolvation entropy dominates. |

| Amprenavir (APV) | ~ -13.4 [9] | ~ -13 to -17 [9] | Enthalpy & Entropy | Less favorable total entropy than NFV; stronger electrostatic enthalpy. |

The Critical Role of Solvent Entropy

Beyond the configurational entropy of the solute, the entropy of the solvent water is a powerful driving force. Research applying the Asakura-Oosawa theory to protein folding and binding demonstrates that the translational entropy (TE) of water can be the dominant contributor to the free energy change [8]. When two hydrophobic surfaces on a protein and ligand come together, the excluded volumes for water molecules overlap. This overlap increases the total volume available for the translational movement of water molecules in the system, leading to a gain in their entropy and a consequent decrease in the system's free energy. This effect is particularly potent in biological systems due to the small size of water molecules and the complex geometries of binding interfaces, which can create large overlapping excluded volumes [8].

The following diagram visualizes the competing entropy changes that determine the spontaneity of a binding event, highlighting the critical, often decisive, role of solvent entropy.

Table 4: Key Research Tools for Investigating Configurational Entropy

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application in ΔS_conf Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| AMBER | Software Suite | Molecular Dynamics Simulation | Performs MD equilibration/production runs for DDM and MM/GBSA; includes modules for alchemical free energy calculations (e.g., TI). |

| GROMACS | Software Suite | Molecular Dynamics Simulation | High-performance MD engine used to generate trajectories for subsequent entropy analysis with MM/GBSA or other methods. |

| Normal Mode Analysis (NMA) | Computational Algorithm | Entropy Calculation | Calculates the vibrational entropy of a molecular system from a set of snapshots; often integrated into MM/GBSA workflows. |

| Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) | Experimental Instrument | Measuring Binding Thermodynamics | Directly measures the ΔG, ΔH, and TΔS of binding in a single experiment, providing experimental validation for computational predictions. |

| Linear Interaction Energy (LIE) | Computational Method | Binding Affinity Estimation | A simpler, semi-empirical method to estimate ΔG_bind; less direct for entropy decomposition but useful for screening. |

| GBNSR6 Model | Implicit Solvent Model | Solvation Free Energy Calculation | A specific Generalized Born (GB) model used in MM/GBSA to compute the polar solvation component (ΔG_pol) efficiently and accurately [11]. |

Configurational entropy loss, ΔSconf, is a fundamental and unavoidable thermodynamic tax levied on every intermolecular binding event. Its significant unfavorable contribution means that spontaneous binding is always a story of compensation, whether through strong, specific enthalpic interactions or through the powerful, omnipresent drive of solvent entropy gain. For researchers and drug developers, moving beyond a simplistic focus on ligand-receptor interactions to embrace a holistic view that includes water and flexibility is no longer optional. The advanced computational protocols detailed here, such as the double-decoupling method and MM/GBSA, provide the means to quantify these effects. Integrating these insights into the rational design pipeline—for instance, by designing ligands that minimize conformational entropy loss through pre-organization or that optimally leverage hydrophobic desolvation—holds the key to developing the next generation of high-affinity, selective therapeutic agents. As a central theme in intermolecular interactions research, mastering the implications of ΔSconf is essential for translating structural knowledge into functional prediction and control.

Configurational entropy (Sconf) is a fundamental thermodynamic property that quantifies the disorder associated with the spatial arrangement of molecules in a material. This in-depth technical guide examines the role of Sconf across three physical states—crystalline, amorphous, and super-cooled liquids—with particular emphasis on its implications for intermolecular interactions research, especially in pharmaceutical and materials science applications. The crystalline state exhibits minimal configurational entropy due to its highly ordered, periodic structure. In contrast, amorphous solids and super-cooled liquids possess significantly higher Sconf, influencing their stability, molecular mobility, and functional properties. This whitepaper synthesizes current theoretical frameworks, experimental methodologies, and computational approaches for quantifying Sconf, providing researchers with practical tools for investigating its critical role in processes ranging from protein-ligand binding to the stabilization of amorphous drug formulations.

Configurational entropy is a measure of the number of accessible molecular arrangements, or microstates, available to a system due to its molecular configuration [10]. In the context of intermolecular interactions research, it provides a crucial link between molecular structure, dynamics, and thermodynamic stability. Unlike thermal entropy, which arises from the distribution of energy, configurational entropy stems from the diversity of spatial arrangements a molecule can adopt.

The formal definition of the configurational entropy for a single molecule or complex can be derived from the quasi-classical entropy integral [1]: [ S{config} = R \ln(8\pi^2 V^\circ) - R \int \rho(\vec{q}{int}) \ln [h^{3N} J(\vec{q}{int}) \rho(\vec{q}{int})] d\vec{q}{int} ] where R is the universal gas constant, (V^\circ) is the standard volume, ( \rho(\vec{q}{int}) ) is the probability density function, (J(\vec{q}_{int})) is the Jacobian of the internal coordinates, and h is Planck's constant.

In molecular systems, S_conf arises from various internal degrees of freedom, including bond rotations, vibrations, and large-scale conformational changes [10]. Its accurate estimation remains challenging due to the complexity of high-dimensional phase spaces and the necessity to account for correlated motions. Recent advances in computational methodologies, such as the application of the k-th nearest neighbour algorithm and force covariance techniques, have significantly improved our ability to extract absolute entropy values from dynamic ensembles [10].

Theoretical Foundations

Thermodynamic Relationships

The configurational entropy represents the difference in entropy between amorphous and crystalline states [12]: [ S{conf}(T) = S{amorph}(T) - S_{crystal}(T) ]

This relationship forms the basis for experimental determination of Sconf through calorimetric measurements. The corresponding configurational enthalpy and Gibbs free energy are defined as [12]: [ H{conf}(T) = H{amorph}(T) - H{crystal}(T) ] [ G{conf}(T) = H{conf}(T) - TS_{conf}(T) ]

These configurational properties can be calculated from their relationship with heat capacity: [ H{conf} = \Delta Hm + \int{Tm}^{T} C{p}^{conf} dT ] [ S{conf} = \Delta Sm + \int{Tm}^{T} \frac{C{p}^{conf}}{T} dT ] where ( \Delta Hm ) and ( \Delta Sm ) are the enthalpy and entropy of melting, respectively, and ( C_{p}^{conf} ) is the configurational heat capacity, defined as the difference between amorphous and crystalline heat capacities [12].

The Kauzmann Paradox and Glass Transition

The temperature dependence of configurational entropy reveals fundamental aspects of material behavior. If a super-cooled liquid maintained equilibrium below the glass transition temperature (Tg), its entropy would eventually fall below that of the crystalline state at the Kauzmann temperature (TK), violating thermodynamic laws [12]. This paradox is resolved by the glass transition, where the system falls out of equilibrium, preventing the entropy catastrophe.

The relationship between temperature and thermodynamic properties for different states is visualized below:

Figure 1: Thermodynamic relationship between states. At Tg, the super-cooled liquid falls out of equilibrium, forming a glass and avoiding the entropy catastrophe at TK.

Configurational Entropy Across Physical States

Crystalline State

In crystalline materials, molecules are arranged in a periodic, repeating lattice structure with minimal disorder. The configurational entropy approaches zero for perfect crystals, as only one microstate (or a very limited number of equivalent arrangements) is accessible. Any residual entropy in crystals typically arises from:

- Point defects: Vacancies, substitutions, or interstitial atoms

- Dislocations: Line defects disrupting the perfect lattice

- Polymorphism: Different crystalline packing arrangements

The highly constrained nature of crystalline materials makes them valuable reference states for calculating configurational entropy differences.

Amorphous State

Amorphous solids (glasses) possess significant configurational entropy frozen in below T_g. Unlike crystals, amorphous materials lack long-range order, with molecules trapped in a multitude of configurations. Key characteristics include:

- Non-equilibrium state: Glasses are metastable and undergo relaxation toward lower energy states over time

- Frozen disorder: The configurational entropy is largely immobilized below T_g

- Relaxation behavior: Physical aging occurs as the material slowly relaxes, reducing enthalpy and entropy without crystallization [12]

The high S_conf of amorphous materials contributes to their enhanced solubility and dissolution rates compared to crystalline counterparts, which is particularly valuable in pharmaceutical applications for poorly soluble drugs [12].

Super-Cooled Liquid State

Super-cooled liquids exist in a metastable equilibrium between the melting point (Tm) and glass transition temperature (Tg). They exhibit unique characteristics:

- High molecular mobility: Viscosity is significantly lower than in the glassy state (typically 10^(-3) - 10^(12) Pa·s) [12]

- Temperature-dependent Sconf: Configurational entropy decreases as temperature approaches Tg

- Cooperatively rearranging regions (CRR): According to Adam-Gibbs theory, the liquid consists of regions that rearrange cooperatively, with CRR size increasing as S_conf decreases [12]

Super-cooled liquids are crucial for understanding the glass formation process and crystallization tendencies of materials.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Configurational Entropy in Different Physical States

| Property | Crystalline State | Amorphous State | Super-Cooled Liquid |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structural Order | Long-range periodic order | Short-range order only | Short-range order only |

| S_conf Magnitude | Minimal (approaches 0) | High (frozen below T_g) | High (temperature-dependent) |

| Molecular Mobility | Limited to vibrations/rotations | Very low below T_g | High (decreasing with cooling) |

| Thermodynamic State | Equilibrium | Non-equilibrium, metastable | Metastable equilibrium |

| Stability | Thermodynamically stable | Physically unstable | Kinetically stabilized |

| Experimental Access | Direct calorimetry | Calorimetry relative to crystal | Calorimetry, computational methods |

Quantitative Data and Methodologies

Experimental Determination

Calorimetric Methods

Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) provides the primary experimental approach for determining configurational entropy. The methodology involves [12]:

- Measure heat capacities: Determine C_p for both crystalline and amorphous forms across the temperature range of interest

- Calculate C_p^conf: Compute the difference between amorphous and crystalline heat capacities

- Integrate from melting point: [ S{conf}(T) = \Delta Sm + \int{Tm}^{T} \frac{C{p}^{conf}}{T} dT ] where ( \Delta Sm = \frac{\Delta Hm}{Tm} ) is the melting entropy

The configurational heat capacity (Cp^conf) follows a hyperbolic temperature dependence above Tg [12]: [ Cp^{conf} = \frac{K}{T} = Cp^{conf}(Tg) \frac{Tg}{T} ]

Table 2: Experimental Parameters for Configurational Entropy Determination

| Parameter | Symbol | Measurement Technique | Critical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glass Transition Temperature | T_g | DSC (midpoint of transition) | Heating rate dependence |

| Melting Temperature | T_m | DSC (onset of endotherm) | Purity effects |

| Enthalpy of Melting | ΔH_m | DSC (area under endotherm) | Reference standard calibration |

| Configurational Heat Capacity | C_p^conf | DSC (modulated mode preferred) | Accurate baseline determination |

| Heat Capacity Change at T_g | ΔC_p | DSC (step change height) | Distinguish from relaxation effects |

Protocol: Calorimetric Determination of S_conf

Materials and Equipment:

- Differential scanning calorimeter with temperature modulation capability

- Hermetic pans for sample encapsulation

- Standard reference materials (e.g., indium, sapphire) for calibration

- 5-10 mg of crystalline and amorphous samples

Procedure:

- Calibrate DSC instrument for temperature and enthalpy using certified standards

- Load crystalline sample and perform temperature scan from 50°C below to 50°C above T_m at 10°C/min

- Measure heat capacity using modulated DSC with ±0.5°C amplitude and 60s period

- Quench cool the melt to form amorphous material (rate > 50°C/min)

- Scan amorphous sample using identical conditions to measure C_p of glass and super-cooled liquid

- Calculate Cp^conf as the difference between amorphous and crystalline Cp values

- Integrate Cp^conf/T from Tm to temperature of interest to obtain S_conf(T)

Data Analysis: [ S{conf}(T) = \frac{\Delta Hm}{Tm} + \int{Tm}^{T} \frac{Cp^{amorph}(T) - C_p^{crystal}(T)}{T} dT ]

Computational Approaches

Molecular Dynamics Simulations

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations provide atomic-level insights into configurational entropy by sampling the accessible phase space of molecular systems [10]. Key methodologies include:

- k-th Nearest Neighbour (kNN) Algorithm: A statistical approach for estimating entropy by quantifying distances between data points in high-dimensional spaces [10]

- Mutual Information Expansion (MIE): Accounts for correlations between different degrees of freedom when calculating configurational entropy [10] [1]

- Maximum Information Spanning Tree (MIST): Advanced MIE variant that efficiently captures essential correlations in biomolecular systems [1]

These methods have been particularly valuable for dissecting the configurational entropy change of protein binding into contributions from molecular internal and external degrees of freedom [1].

Protocol: Configurational Entropy from MD Simulations

System Preparation:

- Construct molecular system with appropriate force field parameters

- Solvate in explicit water molecules using periodic boundary conditions

- Energy minimize and equilibrate using NPT ensemble (1 atm, temperature of interest)

Production Simulation:

- Run MD simulation for sufficient duration to sample relevant configurations (typically 100 ns - 1 μs)

- Save trajectories at appropriate intervals (10-100 ps) for entropy analysis

- Monitor convergence of entropy estimates with simulation time

Entropy Calculation (kNN Method):

- Define relevant degrees of freedom (torsional angles, translational, rotational)

- Calculate distances between configurations in the high-dimensional space

- Apply kNN algorithm to estimate probability densities: [ S \approx \frac{1}{N} \sum{i=1}^{N} \log \rho(\vec{x}i) + constant ]

- Account for correlated motions using MIE or MIST frameworks

The following diagram illustrates the workflow for computational determination of configurational entropy:

Figure 2: Computational workflow for S_conf calculation from MD simulations.

Applications in Intermolecular Interactions Research

Pharmaceutical Sciences

Configurational entropy plays a crucial role in amorphous drug formulation and stabilization. Key applications include:

- Solubility Enhancement: The higher free energy of amorphous systems ((G{conf} = H{conf} - TS_{conf})) increases solubility and dissolution rates [12]

- Physical Stability Prediction: Sconf influences molecular mobility through the Adam-Gibbs equation: [ \tau = \tau0 \exp\left(\frac{B}{TS_{conf}}\right) ] where τ is the structural relaxation time [12]

- Crystallization Inhibition: Polymers in solid dispersions reduce molecular mobility partly by decreasing S_conf

The relationship between configurational entropy and molecular mobility explains why storage below Tg enhances stability but doesn't guarantee prevention of crystallization, as molecular motions still occur below Tg [12].

Biomolecular Interactions

In protein-ligand binding and protein-protein interactions, configurational entropy change is a central constituent of the free energy change [1]. Recent studies demonstrate that:

- Configurational entropy contribution can be of similar magnitude as solvent entropy contribution [1]

- Different coupling terms between internal and external degrees of freedom contribute significantly to overall configurational entropy change [1]

- NMR-based approaches for configurational entropy change estimation are supported by the finding that total entropy change can be approximated by rescaling the sum of uncoupled contributions from internal degrees of freedom [1]

These insights significantly impact computational drug design by helping overcome enthalpy/entropy compensation effects [1].

Advanced Materials

Phase-change materials (PCMs) represent another application where configurational entropy plays a critical role. In materials like antimony (Sb) and its alloys, liquid-state anomalies and fragility of super-cooled liquids influence their switching capabilities between amorphous and crystalline states [13]. The relationship between viscosity (η) and configurational entropy follows the Adam-Gibbs equation: [ \eta = \eta0 \exp\left(\frac{D}{TS{conf}}\right) ] where high fragility (strong temperature dependence of viscosity) correlates with unique crystallization behavior in PCMs [13].

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Configurational Entropy Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Dynamics Software (GROMACS, AMBER, NAMD) | Simulates molecular trajectories for entropy calculation | Computational estimation of S_conf from simulated ensembles |

| Differential Scanning Calorimeter | Measures heat capacity differences between states | Experimental determination of S_conf via calorimetry |

| Hermetic Sealing pans | Encapsulates samples during thermal analysis | Prevents moisture loss/absorption during DSC measurements |

| Neural Network Potentials | Machine-learned interatomic potentials | Accelerated MD simulations with near-quantum accuracy (e.g., for antimony studies [13]) |

| kNN Algorithm Software | Implements k-th nearest neighbor entropy estimation | Computational entropy from high-dimensional data |

| MIST Implementation | Calculates mutual information expansion terms | Captures correlated motions in entropy calculations of biomolecules [1] |

Configurational entropy serves as a fundamental bridge between molecular structure, dynamics, and thermodynamic stability across crystalline, amorphous, and super-cooled liquid states. Its quantification through both experimental calorimetric methods and advanced computational approaches provides critical insights for intermolecular interactions research. In pharmaceutical sciences, understanding S_conf enables rational design of amorphous drug formulations with optimized stability and performance. In biomolecular interactions, it reveals the intricate balance between enthalpy and entropy that governs binding affinity. For advanced materials like phase-change systems, configurational entropy helps explain unusual liquid-state properties and crystallization behavior. As computational methodologies continue to advance, particularly through machine-learned potentials and efficient entropy estimation algorithms, our ability to probe and manipulate configurational entropy will further expand, enabling new breakthroughs in materials design and drug development.

Configurational entropy (Sconf), the excess entropy of the amorphous state over the crystalline state, is a pivotal thermodynamic parameter governing the behavior of amorphous pharmaceuticals. It sits at a critical intersection, simultaneously driving the enhanced solubility and dissolution properties that make amorphous forms attractive, while also influencing the molecular mobility that can lead to physical instability and recrystallization. This whitepaper delineates the dual role of Sconf, examining its quantification through calorimetric methods, its direct incorporation into stability models via the Adam-Gibbs equation, and its complex interplay with kinetic factors. For researchers and drug development professionals, a deep understanding of S_conf is not merely an academic exercise but a practical necessity for navigating the trade-offs between bioavailability and stability in amorphous solid dispersions, ultimately enabling a more rational design of robust, high-performance drug products.

In the realm of pharmaceutical sciences, the amorphous state of a drug substance offers a powerful strategy to overcome the solubility limitations of crystalline materials, which constitute a significant portion of modern drug pipelines. The amorphous form is characterized by a disordered, non-crystalline molecular arrangement, resulting in a state of higher energy. This elevated energy state manifests as excess thermodynamic properties, including configurational enthalpy (Hconf), Gibbs free energy (Gconf), and critically, configurational entropy (Sconf). Sconf is formally defined as the difference in entropy between the amorphous and the crystalline states of a compound (Sconf = Samorph - S_crystal) [12]. This parameter is more than a simple descriptor; it is a fundamental property involved in both the thermodynamic driving forces and the kinetic processes that dictate the stability and performance of amorphous pharmaceuticals.

The central challenge in formulating amorphous drugs lies in managing the inherent instability that accompanies their desirable solubility enhancement. The same high energy that favors rapid dissolution also provides a potent thermodynamic driving force for recrystallization, a process that negates the solubility advantage. The stability of the amorphous state is therefore not guaranteed, and its prediction remains a complex challenge. Historically, research has oscillated between emphasizing kinetic parameters, such as molecular mobility, and thermodynamic parameters, such as the free energy difference, as the primary predictors of stability. Emerging from this discourse is the recognition that Sconf is a key bridging parameter, integral to both the thermodynamic and kinetic perspectives [14] [12]. Its role in the Adam-Gibbs theory directly links the configurational state of the system to its molecular mobility, making it a essential quantity for a holistic understanding of amorphous behavior. This whitepaper explores this critical balance, detailing how Sconf influences the solubility-stability paradox and providing methodologies for its quantification and application in rational formulation design.

Theoretical Foundations: The Dual Role of S_conf

S_conf is a critical parameter because it is not merely a static measure of disorder; it actively participates in the key processes that define the fate of an amorphous pharmaceutical. Its influence is twofold, governing both the "why" of recrystallization (thermodynamics) and the "how fast" (kinetics).

Thermodynamic Driving Force

The enhanced apparent solubility and dissolution rate of an amorphous drug are direct consequences of its elevated Gibbs free energy. The configurational free energy (Gconf) is calculated from the configurational enthalpy and entropy as shown in the equation below, which also provides the method for determining Hconf and S_conf from experimental heat capacity data [12]:

Where:

and ΔS_m = ΔH_m / T_m.

The larger the value of Gconf, the greater the thermodynamic driving force for dissolution. However, this same driving force also makes recrystallization thermodynamically favorable. The configurational entropy (Sconf) is a major component of this energy landscape. A high Sconf contributes to a high Gconf, which is beneficial for solubility but detrimental to physical stability, as the system will seek to reduce this excess energy by reverting to the crystalline state [12].

Kinetic Involvement and the Adam-Gibbs Theory

While thermodynamics dictates the direction of change, kinetics controls the rate. The molecular mobility of an amorphous system, often expressed as its reciprocal, the relaxation time (τ), is a key kinetic factor determining the rate of crystallization. The most common theory linking thermodynamics to kinetics is the Adam-Gibbs (AG) theory, which introduces the concept of cooperatively rearranging regions (CRRs). The AG theory posits that molecular rearrangement occurs in coordinated regions, and the size of these regions is determined by the configurational entropy. The central equation is:

where τ_0 and C are constants [14] [12].

Upon cooling, the Sconf decreases, causing the size of the CRRs to increase. This increasing cooperativity slows down molecular motion. The AG equation demonstrates that Sconf is not just a thermodynamic quantity but is the fundamental link between the thermodynamic state of the system and its molecular mobility. A system with low Sconf will have higher molecular mobility (shorter τ), making it more susceptible to crystallization, even if the thermodynamic driving force is significant [12]. This dual role makes Sconf a critical parameter for any comprehensive stability assessment.

Quantitative Analysis: Correlating S_conf with Stability and Mobility

Empirical studies across multiple drug compounds have quantitatively established the significant, and sometimes dominant, role of S_conf in predicting amorphous stability. Moving beyond case studies to larger sample sets provides robust evidence for its utility.

Table 1: Correlation of Thermodynamic and Kinetic Parameters with Physical Stability (n=12 drugs)

| Parameter Category | Specific Parameter | Correlation with Stability (r²) | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kinetic | Relaxation Time (τ) below Tg | No correlation | Stability predictions based on relaxation time alone may be inadequate [14]. |

| Kinetic | Fragility Index below Tg | No correlation | Fragility values spanned 8.9 to 21.3, but did not correlate with stability [14]. |

| Thermodynamic | Configurational Entropy (S_conf) above Tg | 0.685 (Strongest correlation) | S_conf exhibited the strongest correlation with observed physical stability [14]. |

| Thermodynamic | Configurational Enthalpy (H_conf) above Tg | Reasonable correlation | Correlated with stability, but weaker than S_conf [14]. |

A study investigating 12 amorphous drugs found that below the glass transition temperature (Tg), traditional kinetic parameters like relaxation time and fragility index showed no correlation with the observed physical stability. In contrast, thermodynamic parameters, particularly the configurational entropy, demonstrated a much stronger relationship with stability above Tg [14]. This challenges the conventional wisdom that molecular mobility is the sole dominant factor and highlights the necessity of incorporating thermodynamic measurements.

Further supporting this, a study of five structurally diverse compounds (ritonavir, ABT-229, fenofibrate, sucrose, and acetaminophen) revealed that the crystallization tendency under non-isothermal conditions was most closely related to the entropic barrier to crystallization and the molecular mobility. The entropic barrier is inversely related to the probability that molecules are in the proper orientation for crystallization. For instance, ritonavir, which did not crystallize, possessed the highest entropic barrier, while acetaminophen and sucrose, which crystallized readily, had the lowest entropic barriers. This indicates that even with a significant thermodynamic driving force for crystallization, a high entropic barrier can impart stability by making the molecular alignment required for nucleation less probable [15].

Table 2: Ranking of Factors Influencing Crystallization Tendency in Five Model Compounds [15]

| Compound | Crystallization Observed? | Configurational Free Energy (G_c) Driving Force | Entropic Barrier to Crystallization | Molecular Mobility (1/τ) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ritonavir | No | Highest | Highest | Lowest |

| Acetaminophen | Yes | Medium | Lowest | Highest |

| Fenofibrate | Yes | Medium | Medium | Medium |

| Sucrose | Yes | Low | Lowest | Medium |

| ABT-229 | Yes | Lowest | Medium | Low |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

The accurate determination of S_conf is foundational to its application. The primary methodology relies on calorimetric measurements to obtain the heat capacity data required for the calculations outlined in Section 2.1.

Determination of Configurational Heat Capacity (Cp_conf)

Objective: To measure the heat capacities of the crystalline and amorphous forms of a drug substance as a function of temperature. Instrumentation: Modulated Temperature Differential Scanning Calorimetry (MTDSC) is the preferred technique due to its ability to separate reversing and non-reversing thermal events. Procedure:

- Calibration: Calibrate the DSC instrument for temperature and heat capacity using standard references (e.g., sapphire).

- Sample Preparation:

- Crystalline Sample: Use the pure, stable crystalline form of the drug. Gently grind if necessary to ensure good thermal contact.

- Amorphous Sample: Prepare the amorphous form directly in a DSC pan. This can be achieved by melting the crystalline sample and subsequently quenching it rapidly (e.g., with liquid nitrogen) to prevent recrystallization.

- Measurement:

- For both crystalline and amorphous samples, perform MTDSC scans from a temperature well below the glass transition (Tg) to above the melting point (Tm) at a controlled heating rate (e.g., 1-2 K/min).

- Ensure the modulation amplitude and period are appropriately set to obtain clear reversing heat flow signals.

- Data Analysis:

- Extract the reversing heat capacity (Cp) as a function of temperature for both the amorphous (Cpamorph) and crystalline (Cpcrystal) forms.

- The configurational heat capacity is calculated as:

Cp_conf = Cp_amorph - Cp_crystal[12]. It is critical to note that Cp_conf is not the same as the heat capacity change (ΔCp) at the glass transition.

Calculation of Configurational Entropy (S_conf)

Objective: To compute the configurational entropy (Sconf) from the melting parameters and the measured Cpconf. Data Requirements: Enthalpy of fusion (ΔHm), Melting temperature (Tm), and the Cp_conf values from the previous protocol. Procedure:

- Obtain Fusion Parameters: From a standard DSC scan of the crystalline material, determine the melting enthalpy (ΔHm) and melting temperature (Tm). Calculate the melting entropy:

ΔS_m = ΔH_m / T_m. - Integrate Cp_conf: Using the data from the MTDSC experiments, perform the integrations as per the equations in Section 2.1:

H_conf(T) = ΔH_m + ∫_{T_m}^{T} Cp_conf dTS_conf(T) = ΔS_m + ∫_{T_m}^{T} (Cp_conf / T) dT

- Consider Temperature Dependence: Note that above Tg, the configurational heat capacity may not be constant. Its temperature dependence has been described by a hyperbolic relation:

Cp_conf(T) = Cp_conf(Tg) * (Tg / T)[12]. The choice of model for Cpconf above Tg can influence the accuracy of the calculated Sconf at temperatures far from Tm.

The following workflow diagram illustrates the experimental and computational pathway for determining S_conf and its application in stability assessment:

Figure 1: Experimental Workflow for Determining Configurational Entropy. This diagram outlines the key steps from sample preparation to the application of S_conf in stability prediction.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

The experimental determination of S_conf and the formulation of stable amorphous systems require a specific set of reagents and analytical tools. The following table details key materials used in this field.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Amorphous Pharmaceutical Studies

| Category | Item / Technique | Function / Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Model Compounds | Ritonavir, Fenofibrate, Acetaminophen, Sucrose, Indomethacin | Structurally diverse model drugs for studying crystallization behavior and validating thermodynamic models [15] [12]. |

| Polymeric Carriers | KOLIONA64 (KVA64), KOLIV17ONA17 (K17PF), HPMCAS, Eudragit EPO | Polymers used to form amorphous solid dispersions (ASDs) to enhance physical stability by increasing Tg and providing kinetic stabilization [16]. |

| Primary Analytical Instrument | Modulated Temperature DSC (MTDSC) | Measures heat capacity (Cp) of amorphous and crystalline forms as a function of temperature, which is the primary data source for calculating Sconf, Hconf, and Tg [15] [12]. |

| Theoretical Models | Adam-Gibbs (AG) Equation, Vogel-Tammann-Fulcher (VTF) Equation | Used to calculate molecular relaxation times (τ) by incorporating S_conf, linking thermodynamic state to kinetic stability [14] [12]. |

| Solubility/Miscibility Modeling | Flory-Huggins (FH) Theory, PC-SAFT, Hansen Solubility Parameters | Predicts the miscibility and phase behavior of API-polymer blends, which is critical for designing stable ASDs [16]. |

Integrated Stability Framework: Bridging Thermodynamics and Kinetics

The evidence clearly indicates that a singular focus on either thermodynamics or kinetics is insufficient for predicting the physical stability of amorphous pharmaceuticals. An effective framework must integrate both. The following diagram synthesizes the interplay of the key factors discussed, with S_conf at its core.

Figure 2: The Dual Role of S_conf in Amorphous Pharmaceuticals. This framework illustrates how a high S_conf simultaneously drives beneficial solubility and, through its effect on mobility, can enhance stability, while also creating a thermodynamic instability.

This framework reveals the critical balance. A high S_conf is a double-edged sword:

- On one hand, it increases the thermodynamic driving force for crystallization, which is detrimental to stability.

- On the other hand, according to the Adam-Gibbs theory, a high S_conf acts to reduce molecular mobility, which is beneficial for stability.

The overall stability of a specific amorphous drug will depend on which of these opposing influences is dominant. For instance, a compound like ritonavir possesses a high Sconf, which results in a high entropic barrier to crystallization and low mobility, making it inherently stable despite a large thermodynamic driving force [15]. This integrated view explains why a parameter like Sconf, which sits at the nexus of these competing effects, shows a stronger correlation with stability than kinetic parameters alone.

Configurational entropy is a fundamental property that critically influences the delicate balance between solubility and stability in amorphous pharmaceuticals. The empirical data demonstrates that Sconf can be a more robust predictor of physical stability than kinetic parameters like relaxation time. Its unique position, embedded in both the thermodynamic equations that define the driving force for crystallization and the Adam-Gibbs equation that governs molecular mobility, makes it an indispensable parameter for rational formulation design. For researchers aiming to develop viable amorphous drug products, the experimental protocols for determining Sconf, combined with the integrated stability framework, provide a powerful approach to navigate the inherent challenges. Moving forward, the continued integration of S_conf into predictive models and formulation strategies will be essential for unlocking the full potential of amorphous systems to deliver poorly soluble drugs, thereby accelerating the development of critical new therapies.

Quantifying Disorder: Computational and Experimental Methods for Measuring S_conf

Configurational entropy, a measure of the number of ways a molecular system can arrange its structure while maintaining the same energy, plays a fundamental role in governing intermolecular interactions. In molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, the calculation of entropy from trajectory data remains one of the most challenging yet crucial aspects for predicting binding affinities, protein stability, and drug-receptor interactions. The trajectory of a MD simulation—a time-series of atomic positions and velocities—encodes the information about the system's exploration of its conformational landscape, from which entropy can be derived [17]. Unlike enthalpy, which can be directly computed from instantaneous coordinates, entropy quantification requires statistical mechanical treatment of the entire trajectory to assess the probability of visited states [18]. This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of trajectory analysis methodologies for entropy calculation, framed within the critical context of understanding configurational entropy's role in intermolecular interactions research for drug development.

Theoretical Foundation: Configurational Entropy in Intermolecular Interactions

The Role of Entropy in Biomolecular Recognition

Intermolecular interactions, particularly in drug binding, are governed by the balance between enthalpy (direct molecular interactions) and entropy (disorder and freedom). While enthalpy contributions from hydrogen bonds, electrostatic, and van der Waals interactions are more intuitively understood, the configurational entropy component of binding free energy represents a critical determinant that can dominate the binding affinity [18]. When a ligand binds to its receptor, the system typically loses configurational entropy due to restricted motion, which opposes binding. However, this loss can be offset by the release of ordered water molecules (solvent entropy gain) and by pre-organization of the binding partners [18]. Neglecting entropy in binding free energy calculations can lead to severely violated thermodynamic principles and inaccurate predictions [18].

The Computational Challenge of Entropy

The fundamental challenge in calculating entropy from MD trajectories lies in the accurate characterization of the system's phase space volume exploration. For a biomolecular system with thousands of atoms, the conformational space is astronomically large, and typical MD simulations (nanoseconds to microseconds) sample only a minuscule fraction of it [17]. Additionally, unlike solids with defined reference states or gases with simple statistical distributions, liquids and biomolecules exhibit complex interplay between strong interatomic interactions and dynamic disorder, making entropy particularly difficult to compute [19]. This has historically led to the perception that entropy cannot be accurately determined from MD simulations, prompting the development of various alternative strategies [19].

Methodologies for Entropy Calculation from MD Trajectories