Computing Diffusion Coefficients with the Einstein Relation: A Practical Guide for Molecular Dynamics Simulations

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and scientists on utilizing the Einstein relation within molecular dynamics (MD) simulations to compute diffusion coefficients.

Computing Diffusion Coefficients with the Einstein Relation: A Practical Guide for Molecular Dynamics Simulations

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and scientists on utilizing the Einstein relation within molecular dynamics (MD) simulations to compute diffusion coefficients. It covers foundational theory, from the basic Einstein-Smoluchowski equation to its connection with other formulations like the Stokes-Einstein relation. The guide details practical methodologies for implementation in both classical and ab initio MD, highlighting automated tools and workflows. It further addresses critical troubleshooting aspects, including finite-size effects and distinguishing diffusive from ballistic motion, and discusses validation strategies through comparison with experimental data and alternative computational methods. The content is tailored for applications in materials science and drug development, offering actionable insights for obtaining accurate and reliable transport properties.

The Einstein Relation: From Brownian Motion to Modern Molecular Dynamics

The Einstein-Smoluchowski equation represents a foundational pillar in statistical mechanics and diffusion theory, establishing a fundamental connection between microscopic particle motion and macroscopic transport phenomena. This relationship, developed independently by Albert Einstein and Marian Smoluchowski in the early 1900s, provides the theoretical framework for understanding Brownian motion and serves as the first quantitative expression of the fluctuation-dissipation theorem [1] [2]. The historical significance of this equation cannot be overstated—it established a quantitative link between the diffusion coefficient (D) and the Avogadro number, enabling Perrin's experiments that definitively confirmed the physical reality of atoms [2].

In contemporary research, this relationship remains indispensable across diverse fields, from pharmaceutical development and materials science to the study of complex systems exhibiting anomalous diffusion. The equation originally derived for ideal systems has since been extended to encompass non-equilibrium thermodynamics, generalized statistical mechanics, and molecular dynamics simulations, maintaining its relevance in cutting-edge scientific investigations [1] [2]. This technical guide examines the theoretical foundations, practical implementations, and research applications of the Einstein-Smoluchowski relation with particular emphasis on its role in molecular dynamics studies of diffusion phenomena.

Theoretical Foundations and Mathematical Formalism

The Original Formulation

The classical Einstein-Smoluchowski relation establishes a fundamental connection between the diffusion coefficient (D), mobility (μ), and thermodynamic temperature:

[ μ = \frac{D}{k_B T} ]

where (k_B) is Boltzmann's constant and T is the absolute temperature of the thermal bath [1] [2]. This relationship emerges naturally from comparing the equilibrium distribution obtained from the Smoluchowski equation with the canonical Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution of statistical mechanics.

In the original Smoluchowski formulation, the time evolution of a probability density function (f(x,t)) in configuration space under an external potential (V(x)) is described by:

[ \frac{∂f}{∂t} - ∇ ⋅ [μ∇V(x)f + D∇f] = 0 ]

which models the kinetic approach toward equilibrium [2]. The stationary solution to this equation takes the form:

[ f(x,t) = \exp\left(Γ - \frac{μ}{D}V(x)\right) ]

where Γ is a normalization constant [2].

The Einstein Relation in Molecular Dynamics

In molecular dynamics simulations, the Einstein relation provides a powerful method for calculating diffusion coefficients from particle trajectories. The mean-square displacement (MSD) of particles undergoing Brownian motion relates to the diffusion coefficient through:

[ D = \frac{1}{2d} \lim{t \to \infty} \frac{d}{dt} ⟨|\mathbf{r}i(t + t0) - \mathbf{r}i(t0)|^2⟩{t_0} ]

where d is the dimensionality (typically 3 for three-dimensional systems), (\mathbf{r}_i(t)) represents the position vector of atom i at time t, and the angle brackets denote averaging over time origins and particles of the same species [3] [4]. This approach enables the computation of self-diffusion coefficients directly from atomic displacements recorded during molecular dynamics simulations.

Generalized Formulations

For complex systems exhibiting anomalous diffusion behavior, the classical Einstein-Smoluchowski relation has been extended within the framework of generalized statistical mechanics. These systems, characterized by non-exponential stationary distributions and nonlinear mean-square displacement time dependence ((⟨x^2(t)⟩ ∝ t^α) with α ≠ 1), require modified theoretical approaches [2]. In this context, the formal relationship between mobility and diffusion coefficient may be preserved ((μ = βD)), but the parameter β acquires a different physical interpretation distinct from the conventional inverse temperature [2].

Computational Methodologies and Protocols

Molecular Dynamics Implementation

The calculation of diffusion coefficients via the Einstein relation requires careful implementation of molecular dynamics methodologies. The following experimental protocol has been established for accurate determination of diffusivity in various systems:

System Preparation and Equilibration

- Construct molecular structures from atomic-level coordinates and perform geometry optimization using algorithms such as the Smart algorithm, which typically employs steepest descent followed by conjugate gradient and Newton methods [3]

- Create simulation boxes with appropriate dimensions (e.g., 78.8×78.8×78.8 ų for long-chain molecules) containing the target molecules and solvent molecules [3]

- Employ ensemble choices such as NVT (canonical) or NPT (isothermal-isobaric) with periodic boundary conditions to mimic realistic thermodynamic environments [4]

Production Dynamics and Trajectory Analysis

- Execute sufficiently long production trajectories to capture diffusive regimes, typically requiring tens to hundreds of picoseconds for convergence [4]

- Extract unwrapped atomic trajectories from molecular dynamics outputs, accounting for periodic boundary conditions [4]

- Compute mean-square displacement (MSD) profiles for relevant species using time-averaging approaches:

[ \text{MSD}α(t) = \frac{1}{Nα} ∑{i∈α} ⟨|\mathbf{r}i(t0 + t) - \mathbf{r}i(t0)|^2⟩{t_0} ]

where (N_α) represents the number of atoms of species α [4]

Diffusion Coefficient Extraction

- Calculate the diffusion coefficient from the slope of the MSD versus time curve in the linear regime:

[ Dα = \frac{1}{6} \lim{t \to \infty} \frac{d}{dt} \text{MSD}_α(t) ]

for three-dimensional systems [3]

- Implement block averaging techniques to quantify statistical uncertainties and ensure convergence [4]

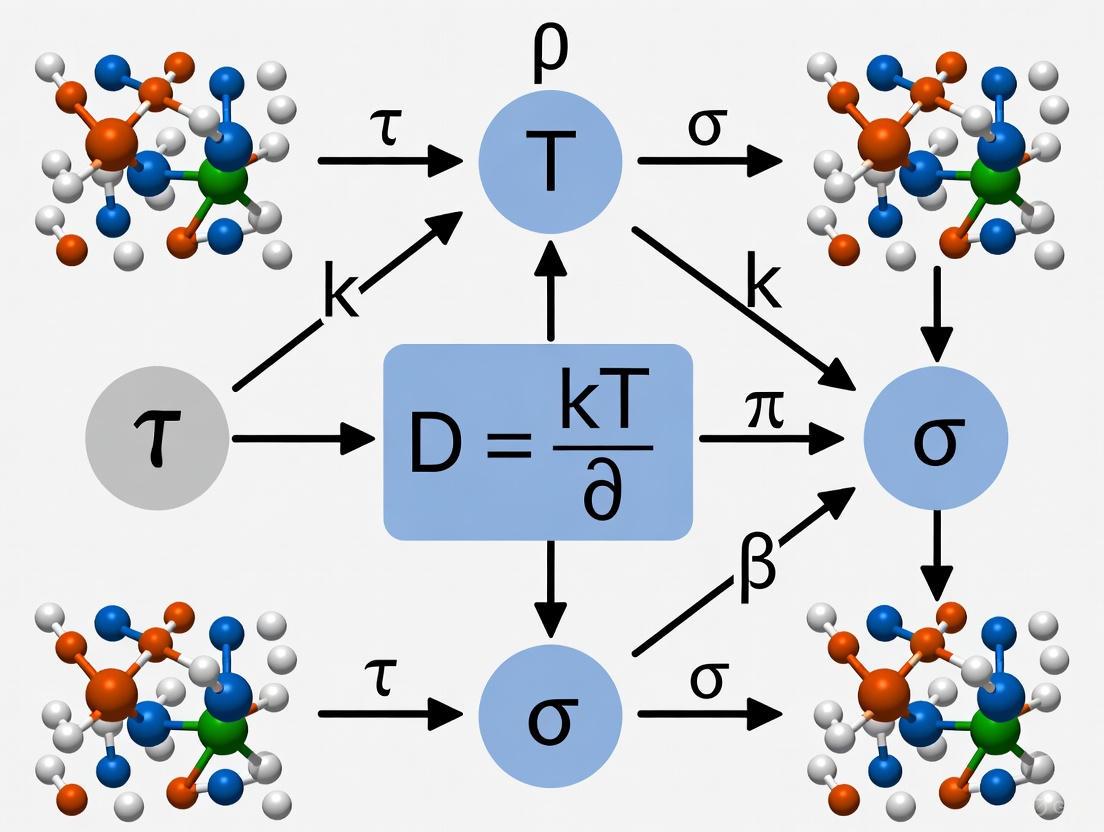

Figure 1: Molecular Dynamics Workflow for Diffusion Coefficient Calculation

Forcefield Selection and Validation

The accuracy of molecular dynamics predictions depends critically on the choice of interaction potentials. Multiple forcefields have been developed and validated for diffusion coefficient calculations:

Table 1: Forcefields for Diffusion Calculations in Molecular Dynamics

| Forcefield | Type | Basis | Applications | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| COMPASS | Class II | Ab initio data | Condensed phase materials | [3] |

| UFF | General | Atomic parameters | Wide range of elements | [3] |

| CVFF | Class II | Empirical | Biomolecules, polymers | [3] |

| PCFF | Class II | Empirical | Polymers, carbohydrates | [3] |

| OPLS-AA | Optimized | Liquid simulations | Drug molecules in solution | [5] |

| MMFF94x | Merck | Molecular mechanics | Small molecule conformations | [6] |

Comparative studies indicate that different forcefields can yield varying diffusion coefficient estimates, highlighting the importance of forcefield selection and validation against available experimental data [3]. For pharmaceutical applications, the OPLS-AA forcefield has demonstrated strong performance in predicting solvation and transport properties of drug molecules [5].

Research Applications and Case Studies

Pharmaceutical Development

In drug discovery and development, the Einstein-Smoluchowski relation enables computational prediction of key pharmacokinetic properties. Molecular dynamics simulations coupled with Einstein-based diffusion analysis provide insights into molecular transport behavior that directly influences drug efficacy [6] [5].

Table 2: Experimental Diffusion Coefficients of Pharmaceutical Compounds

| Compound | Molecular Formula | Temperature (K) | Experimental D (10⁻⁶ cm²/s) | Computational Method | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gabapentin | C₉H₁₇NO₂ | 310 | ~0.5-0.7 (estimated) | MD with OPLS-AA/TIP3P | [5] |

| Paracetamol | C₈H₉NO₂ | 310 | ~0.5-0.7 (estimated) | MD with OPLS-AA/TIP3P | [5] |

| Albuterol | C₁₃H₂₁NO₃ | 310 | ~0.5-0.7 (estimated) | MD with OPLS-AA/TIP3P | [5] |

| Glucose | C₆H₁₂O₆ | 298 | 0.67 | Stokes-Einstein with re | [6] |

| Sucrose | C₁₂H₂₂O₁₁ | 298 | 0.52 | Stokes-Einstein with re | [6] |

Studies of gabapentin, paracetamol, and albuterol in aqueous solution demonstrate how molecular dynamics simulations employing the Einstein relation can predict diffusion coefficients consistent with experimental values, providing valuable insights for drug formulation and delivery optimization [5]. The solvation-free energy, which critically influences diffusion behavior, can be computed using thermodynamic integration (TI) and free energy perturbation (FEP) methods across multiple coupling constant (λ) values [5].

Materials Science Applications

In materials science, the Einstein-Smoluchowski relation facilitates the investigation of atomic transport in complex systems, including:

Glass-Forming Melts Molecular dynamics simulations of Ni₃₆Zr₆₄, Cu₆₅Zr₃₅, and Ni₈₀Al₂₀ have revealed the breakdown of the Stokes-Einstein relation at temperatures approaching the glass transition (TSE ≈ 2.0Tg) [7]. This breakdown manifests as a decoupling between component diffusion coefficients and viscosity, providing insights into the fundamental nature of glass formation.

Liquid Alloys and Oxides First-principles molecular dynamics employing the SLUSCHI framework enables automated diffusion calculations in complex systems such as Al-Cu liquid alloys, Li₇La₃Zr₂O₁₂, Er₂O₃, and oxygen transport in bcc/fcc Fe [4]. These investigations provide atomic-level understanding of diffusion mechanisms under conditions difficult to access experimentally.

Anomalous Diffusion in Complex Systems

The classical Einstein-Smoluchowski relation assumes normal diffusion characterized by mean-square displacement linear with time ((⟨x^2(t)⟩ ∝ t)). However, many complex systems exhibit anomalous diffusion behavior:

[ ⟨x^2(t)⟩ ∝ t^α ]

where α < 1 indicates subdiffusion and α > 1 indicates superdiffusion [2]. Such anomalous behavior arises in systems with long-range interactions, time-persistent memory effects, or structural heterogeneity, including:

- Cell dynamics and biophysical systems [2]

- Worm-like micellar solutions [2]

- Glass-forming materials near the glass transition [7]

For these systems, generalized statistical mechanics approaches incorporating nonlinear Smoluchowski equations and extended entropy formulations provide a theoretical framework for understanding deviation from classical behavior [2].

Table 3: Computational Tools for Diffusion Coefficient Calculations

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application Context | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SLUSCHI-Diffusion | Workflow Manager | Automated AIMD diffusion analysis | Metals, oxides, alloys | [4] |

| GROMACS | MD Software | Classical molecular dynamics | Biomolecules, drugs in solution | [5] |

| VASP | DFT Software | Ab initio molecular dynamics | Electronic structure analysis | [4] |

| MOE | Modeling Suite | Conformational analysis, radius calculation | Small molecule drugs | [6] |

| COMPASS Forcefield | Forcefield | Ab initio based potential | Organic/inorganic materials | [3] |

| OPLS-AA | Forcefield | Optimized biomolecular potential | Drug molecules in solution | [5] |

Figure 2: Forcefield Selection Guide for Diffusion Studies

Future Perspectives and Research Directions

The continuing evolution of the Einstein-Smoluchowski relation encompasses several emerging research frontiers:

Generalized Thermodynamics Frameworks Ongoing theoretical work extends the Einstein-Smoluchowski relation to systems described by generalized entropies, such as Tsallis and Rényi statistics, which enable description of non-Boltzmann stationary distributions and anomalous diffusion phenomena [2]. These approaches provide powerful tools for understanding complex systems with long-range interactions or memory effects.

High-Throughput Computational Screening Automated workflow systems like SLUSCHI-Diffusion demonstrate the potential for high-throughput first-principles calculation of diffusion coefficients across composition spaces, generating extensive datasets for materials design and drug development [4]. Such approaches enable rapid screening of diffusion properties in complex multi-component systems.

Multiscale Modeling Integration Future research directions include tighter integration between molecular dynamics employing the Einstein relation and coarse-grained or continuum models, facilitating prediction of diffusion behavior across longer length and time scales relevant to technological applications [3] [6] [5].

Machine Learning Enhancement Emerging approaches combine molecular dynamics with machine learning techniques to accelerate diffusion coefficient prediction and extend simulation timescales, potentially overcoming current computational limitations for studying slow diffusion processes [4].

The Einstein-Smoluchowski equation remains a cornerstone of kinetic theory more than a century after its initial derivation. While its fundamental physical insight remains unchanged, ongoing theoretical and computational developments continue to expand its applicability to increasingly complex systems. From pharmaceutical design to materials engineering, the integration of this foundational relationship with modern molecular dynamics simulations and generalized thermodynamic frameworks ensures its continued relevance at the forefront of scientific research. As computational methodologies advance, the Einstein-Smoluchowski relation will continue to provide essential theoretical foundation for understanding and predicting transport phenomena across diverse scientific disciplines.

The Mean Squared Displacement (MSD) serves as a fundamental bridge in molecular science, connecting the observable random motion of individual particles at the microscopic level to macroscopic transport properties that can be measured experimentally. This quantitative measure reveals how far particles move over time, providing critical insights into diffusion processes relevant across scientific disciplines—from pharmaceutical development to materials science. The theoretical foundation of MSD traces back to Albert Einstein's seminal 1905 work on Brownian motion, which established that the average squared distance travelled by particles in a fluid is proportional to the elapsed time [8] [9].

In contemporary research, MSD analysis has become indispensable in molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, where it enables the computation of diffusion coefficients directly from atomic-level trajectories [10] [11]. For drug development professionals, this is particularly valuable for predicting how therapeutic compounds diffuse through delivery systems and biological barriers [12] [13]. The power of MSD lies in its ability to quantify seemingly random particle motions into mathematically tractable and physically meaningful parameters that describe system behavior across multiple scales.

Theoretical Foundations

The Einstein Relation and Diffusion

The fundamental connection between microscopic particle motion and macroscopic diffusion is formally established through the Einstein relation, which states that the mean squared displacement of particles undergoing Brownian motion grows linearly with time [9]. In three dimensions, this relationship is expressed as:

⟨|r(t) - r(0)|²⟩ = 6Dt

where r(t) represents the position of a particle at time t, D is the diffusion coefficient, and the angle brackets denote an ensemble average over all particles in the system [14] [15]. The factor 6 applies specifically to three-dimensional diffusion; for two-dimensional systems it becomes 4, and for one-dimensional systems it becomes 2.

This linear relationship emerges from the random walk nature of particle trajectories in fluids, where each particle experiences numerous collisions that prevent it from following a simple path [8]. At very short timescales, before the first collisions occur, particle motion may appear ballistic with MSD proportional to time squared, but this quickly gives way to the diffusive regime where the linear relationship dominates [8].

The MSD Calculation Framework

Mathematically, the MSD is calculated as the average squared distance that particles travel from their initial positions over a specific time interval:

[MSD(\tau) = \left\langle \frac{1}{N} \sum{i=1}^{N} |ri(\tau) - r_i(0)|^2 \right\rangle]

where N is the number of particles, r_i(τ) is the position of particle i at lag time τ, and the outer angle brackets indicate averaging over all possible time origins [16] [13]. In practical terms, this calculation involves comparing particle positions at different time intervals and computing the squared displacement, then averaging across all particles and multiple starting points throughout the simulation trajectory.

Table 1: MSD Formulations Across Different Dimensionalities

| Dimensionality | MSD Formula | Diffusion Coefficient Relation | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1D | ⟨Δx²⟩ = 2Dt | D = ⟨Δx²⟩/(2t) | Single-file diffusion, confined transport |

| 2D | ⟨Δr²⟩ = 4Dt | D = ⟨Δr²⟩/(4t) | Membrane studies, surface diffusion |

| 3D | ⟨Δr²⟩ = 6Dt | D = ⟨Δr²⟩/(6t) | Bulk diffusion, solution chemistry |

Computational Approaches

Molecular Dynamics Implementation

In molecular dynamics simulations, calculating MSD requires careful consideration of algorithm selection and trajectory processing. The MDAnalysis package implements two primary approaches: the simple "windowed" algorithm that averages over all possible lag times, and a more computationally efficient Fast Fourier Transform (FFT)-based algorithm that scales as N log(N) rather than N² with respect to trajectory length [16]. The FFT approach requires the tidynamics package but offers significant performance advantages for long trajectories.

A critical prerequisite for accurate MSD calculation in MD simulations is the use of unwrapped coordinates. When atoms cross periodic boundaries, they must not be wrapped back into the primary simulation cell, as this would introduce artificial discontinuities in particle trajectories [16]. Various simulation packages provide utilities for this conversion—for example, GROMACS offers gmx trjconv with the -pbc nojump flag to generate appropriate trajectories for MSD analysis.

Workflow for MSD Analysis

The complete workflow for MSD analysis in molecular dynamics simulations follows a systematic process from trajectory preparation to diffusion coefficient calculation:

The first critical step involves loading the appropriate trajectory data and selecting particles for analysis. In MDAnalysis, this is accomplished through the EinsteinMSD class:

Following MSD calculation, the results can be accessed via MSD.results.timeseries for the averaged MSD or MSD.results.msds_by_particle for individual particle MSDs [16]. The msd_type parameter offers flexibility to compute MSD in specific dimensions ('xyz', 'xy', 'xz', 'yz', 'x', 'y', or 'z'), which is particularly useful for studying anisotropic diffusion in confined systems or at interfaces.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

MSD Analysis Protocol

A robust protocol for MSD analysis requires careful attention to both simulation parameters and analysis techniques:

- Trajectory Preparation: Ensure trajectories contain unwrapped coordinates using tools like

gmx trjconv -pbc nojumpin GROMACS or equivalent functions in other MD packages [16]. - Particle Selection: Choose appropriate atoms or molecules for analysis based on research questions—for drug delivery systems, this typically involves selecting active pharmaceutical ingredients or polymer components [12].

- MSD Computation: Execute the MSD calculation using either the windowed or FFT-based algorithm, with the latter preferred for longer trajectories due to better computational efficiency [16].

- Visualization and Validation: Plot MSD against lag time using both linear and log-log scales to identify the diffusive regime and detect potential anomalies at short or long time scales [16].

- Linear Regression: Select the appropriate linear segment of the MSD plot, typically excluding the short-time ballistic regime and long-time poorly averaged data, then perform linear regression to obtain the slope [16].

- Diffusion Coefficient Calculation: Compute the diffusion coefficient using D = slope/(2d), where d is the dimensionality of the MSD [16].

Handling Multiple Replicates

In research involving multiple simulation replicates, proper combination of MSD results is essential. Rather than concatenating trajectories, which introduces artificial discontinuities, MSDs should be computed separately for each replicate and then combined:

This approach preserves the statistical integrity of the MSD calculation while leveraging the enhanced sampling provided by multiple replicates [16].

Research Applications and Case Studies

Drug Delivery Systems

MSD analysis has proven particularly valuable in the development and characterization of drug delivery systems. In a 2024 study investigating ampicillin-loaded polyelectrolyte complexes (PECs) for periodontitis treatment, MD simulations and MSD analysis provided molecular-level insights into drug release mechanisms [12]. Researchers developed chitosan-hyaluronic acid PECs with varying HA content and used MSD-derived diffusion coefficients to understand how polymer composition affects ampicillin mobility.

The study found that increased HA content resulted in higher drug release percentages and swelling indices, correlations that were explained through MSD analysis of the molecular dynamics [12]. The diffusion coefficients obtained from Einstein relation calculations offered valuable insights into the molecular behavior of ampicillin-PEC drug delivery systems, demonstrating how MSD analysis can guide the rational design of therapeutic formulations.

Table 2: Diffusion Scenarios and Corresponding MSD Signatures

| Diffusion Type | MSD Pattern | Mathematical Form | System Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Normal Diffusion | Linear | MSD ~ t | Simple liquids, unconfined particles |

| Subdiffusion | Power law with exponent <1 | MSD ~ t^α (α<1) | Crowded environments, gels |

| Superdiffusion | Power law with exponent >1 | MSD ~ t^α (α>1) | Active transport, directed motion |

| Ballistic Motion | Quadratic | MSD ~ t² | Very short timescales, cold atoms |

| Confined Diffusion | Plateau after linear rise | MSD ~ constant | Trapped particles, porous materials |

Materials Science Applications

Beyond pharmaceutical applications, MSD analysis provides crucial insights in materials science. A 2017 study investigated the diffusion of three plastic additives—UV-P, BHT, and DEHP—in polyethylene terephthalate (PET) using MD simulations [11]. Researchers calculated diffusion coefficients through the Einstein relationship by analyzing mean-square displacement data across temperatures ranging from 293-433 K.

The MD-simulated values agreed with experimental measurements within one order of magnitude for most samples, validating the computational approach [11]. The MSD analysis further revealed the microscopic diffusion mechanism, showing that additive molecules oscillate slowly within the polymer matrix with occasional jumps into adjacent free-volume holes when sufficiently large voids become available. This detailed mechanistic understanding, enabled by MSD analysis, helps predict migration levels of additives from PET packaging materials.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Essential Computational Tools

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for MSD Analysis

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| MDAnalysis [16] | Trajectory analysis | MSD computation from MD trajectories |

| tidynamics [16] | FFT-accelerated MSD | Efficient MSD calculation for long trajectories |

| Unwrapped trajectories [16] | Correct boundary handling | Accurate displacement calculation in periodic systems |

| EinsteinMSD Class [16] | MSD implementation | Direct MSD calculation with various dimensionality options |

| Force fields [10] | Interaction potentials | Determining system evolution in MD simulations |

| Linear regression fitting [16] | Slope calculation | Diffusion coefficient extraction from MSD data |

Best Practices and Validation

Implementing robust MSD analysis requires adherence to several best practices:

- Linear Regime Identification: Always validate the linear portion of MSD plots using log-log scales where the "middle" segment should exhibit a slope of 1 [16].

- Statistical Sampling: Ensure adequate sampling by using multiple replicates and sufficiently long simulation times to reduce uncertainty in diffusion coefficients [16] [10].

- Finite-Size Corrections: Apply appropriate corrections for system size effects, which can significantly influence calculated diffusion coefficients, particularly in confined systems [10].

- Force Field Validation: Confirm that selected force fields accurately reproduce experimental diffusion behavior, as different parameterizations can yield substantially different transport properties [10].

Advanced Methodologies

Complementary Approaches

While MSD analysis based on the Einstein relation remains the most common approach for computing diffusion coefficients from MD simulations, several complementary methods offer additional insights:

- Green-Kubo Formalism: This approach calculates diffusion coefficients from the velocity autocorrelation function using the formula D = (1/3)∫₀∞⟨v(t)·v(0)⟩dt, providing an alternative route that may offer better convergence in some systems [14].

- Excess Entropy Scaling (EES): Recent advances have explored relationships between structural entropy and transport properties, enabling diffusion coefficient estimation with potentially reduced computational expense [10].

- Helfand Moments: This approach relates diffusion to fluctuations in particle positions relative to the system center of mass, particularly useful for multicomponent systems.

Each method has distinct advantages and limitations, and researchers often employ multiple approaches to validate their results and obtain more reliable diffusion coefficients.

Current Challenges and Developments

Despite its established utility, MSD analysis faces several challenges in practical implementation. Finite-size effects, where simulated system dimensions influence calculated diffusion coefficients, remain a significant concern [10]. Additionally, the separation of timescales between ballistic and diffusive regimes requires careful treatment, particularly for complex systems with heterogeneous mobility [8].

Recent methodological developments have focused on enhanced sampling techniques to address the computational expense of simulating slow diffusion processes, as well as improved algorithms for more efficient MSD calculation [16] [10]. The integration of machine learning approaches with traditional MD simulations shows promise for accelerating diffusion coefficient prediction while maintaining accuracy, potentially expanding the accessible timescales for MSD analysis in complex systems.

Mean Squared Displacement analysis represents a powerful methodology that continues to bridge microscopic particle dynamics with macroscopic observable properties across diverse scientific domains. From optimizing drug delivery systems to designing advanced materials, the Einstein relation provides a fundamental connection between molecular-level motion and bulk diffusion behavior. As computational capabilities advance and methodologies refine, MSD analysis remains an essential tool in the molecular simulator's toolkit, enabling deeper insights into transport phenomena and facilitating the rational design of complex systems with tailored diffusion characteristics.

The Stokes-Einstein-Sutherland equation represents a cornerstone of kinetic theory, establishing a fundamental connection between the random motion of microscopic particles and macroscopic fluid properties. This equation, derived independently by William Sutherland (1904), Albert Einstein (1905), and Marian Smoluchowski (1906), provides a theoretical framework for understanding diffusion in liquids with low Reynolds number [9]. Its development was instrumental in confirming the molecular theory of matter, with Einstein's derivation being particularly notable for enabling the first absolute measurement of Avogadro's number, thereby providing conclusive evidence for the existence of atoms [17]. Within contemporary research, particularly in molecular dynamics investigations of diffusion coefficients, the Stokes-Einstein-Sutherland relation serves as a critical link between atomic-scale simulations and experimentally observable transport phenomena [18] [10] [19].

This equation finds extensive application across diverse scientific domains, from analyzing transport in complex plasmas [18] to predicting molecular diffusion in pharmaceutical development [20] [21]. Its robustness has been validated through numerous molecular dynamics simulations and experimental studies, confirming its utility in describing diffusion processes in systems ranging from simple liquids to complex molecular fluids [21] [19].

Theoretical Foundation

Fundamental Equation and Derivation

The classical Stokes-Einstein-Sutherland equation describes the diffusion coefficient, (D), of a spherical particle in a viscous fluid at low Reynolds number. The fundamental form of the equation is expressed as:

[ D = \frac{k_B T}{6 \pi \eta r} ]

where:

- (D) is the diffusion coefficient (m²s⁻¹)

- (k_B) is the Boltzmann constant

- (T) is the absolute temperature (K)

- (\eta) is the dynamic viscosity of the fluid (Pa·s)

- (r) is the radius of the spherical particle (m) [9]

Einstein's original derivation employed a brilliant thermodynamic argument, considering a suspension of Brownian particles at equilibrium under their own weight. He equated two perspectives: (1) a balance between the net weight of particles and the gradient of particle pressure in the direction of gravity, and (2) a balance between the diffusion flux and the settling flux due to gravity. By applying van't Hoff's law for osmotic pressure and the Stokes drag formula for the settling velocity, Einstein arrived at the now-famous relation [17].

The equation represents an early example of a fluctuation-dissipation relation, connecting the fluctuating random motion of particles (diffusion) with the dissipative drag force (mobility) they experience in the fluid [9].

Relationship to Broader Einstein Relations

The Stokes-Einstein-Sutherland equation is a special case of the more general Einstein relation:

[ D = \mu k_B T ]

where (\mu) is the mobility, defined as the ratio of the particle's terminal drift velocity to an applied force ((\mu = v_d/F)) [9].

For spherical particles in the low Reynolds number regime, the mobility is inversely related to the drag coefficient (\zeta) through (\mu = 1/\zeta), with the drag coefficient given by Stokes' law as (\zeta = 6\pi\eta r) for a spherical particle, leading directly to the Stokes-Einstein-Sutherland form [9].

Table 1: Different Forms of Einstein Relations

| Equation Name | Mathematical Form | Application Context | Key Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| General Einstein Relation | (D = \mu k_B T) | General particle motion | Mobility (\mu), Temperature (T) |

| Einstein-Smoluchowski Equation | (D = \frac{\muq kB T}{q}) | Charged particle diffusion | Electrical mobility (\mu_q), Charge (q) |

| Stokes-Einstein-Sutherland Equation | (D = \frac{k_B T}{6\pi\eta r}) | Spherical particles in liquid | Viscosity (\eta), Radius (r) |

| Rotational Diffusion Equation | (Dr = \frac{kB T}{8\pi\eta r^3}) | Rotational diffusion of spheres | Viscosity (\eta), Radius (r) |

Microscopic Formulation Without Hydrodynamic Radius

At the atomic scale, the conventional Stokes-Einstein-Sutherland relation undergoes an important modification. For self-diffusion in simple pure fluids, the equation transforms to:

[ \frac{D\eta\Delta}{kB T} = \alpha{SE} ]

where (\Delta = \rho^{-1/3}) is the mean interatomic separation ((\rho) is the atomic number density), and (\alpha_{SE}) is a numerical coefficient that is only weakly system- and state-dependent [19].

This microscopic version replaces the explicit hydrodynamic radius with the characteristic interatomic separation (\Delta), effectively making the tracer sphere radius an emergent property of the fluid structure rather than an external parameter. Theoretical models based on a vibrational picture of atomic dynamics suggest that (\alpha{SE}) can be expressed in terms of the longitudinal ((cl)) and transverse ((ct)) sound velocities as (\alpha{SE} \simeq 0.132(1 + ct^2/2cl^2)), confining the SE coefficient to a relatively narrow range of (0.132 \lesssim \alpha_{SE} \lesssim 0.181) for most systems [19].

Computational Methods

Molecular Dynamics Framework

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations provide a powerful computational framework for evaluating diffusion coefficients and validating the Stokes-Einstein-Sutherland relation at the atomic scale. MD integrates the classical equations of motion to generate time-resolved atomistic trajectories, enabling direct calculation of both static and dynamic properties from microscopic details [20].

In equilibrium molecular dynamics (EMD), two primary approaches are employed to compute self-diffusion coefficients:

- Einstein Relation Method: Based on the linear growth of mean squared displacement (MSD) with time

- Green-Kubo (G-K) Method: Based on the integration of the velocity autocorrelation function (VACF) [18]

For normal diffusion processes, both methods should yield consistent results, though discrepancies can arise in systems exhibiting anomalous diffusion [18].

Mean Squared Displacement Analysis

The Einstein relation for self-diffusion coefficients in MD simulations is expressed as:

[ D^* = \frac{1}{6} \lim_{t \to \infty} \frac{d}{dt} \langle |\mathbf{r}(t) - \mathbf{r}(0)|^2 \rangle ]

where (D^*) is the self-diffusion coefficient, and (\langle |\mathbf{r}(t) - \mathbf{r}(0)|^2 \rangle) is the ensemble-average mean squared displacement (MSD) [22].

In practice, the observed MSD from simulation data is calculated as:

[ x(t) = \frac{1}{N(t)} \sum{i=1}^{N(t)} |\mathbf{r}i(t) - \mathbf{r}_i(0)|^2 ]

where (N(t)) is the total number of observed squared displacements at time (t) [22].

The self-diffusion coefficient (D^*) is then estimated by fitting a linear model to the observed MSD versus time data and applying:

[ \hat{D}^* = \frac{1}{6} \times \text{slope} ]

where (\hat{D}^*) is the estimated self-diffusion coefficient [22].

Advanced Regression Techniques for Diffusion Coefficient Estimation

Accurate estimation of diffusion coefficients from MD simulations requires careful statistical treatment of MSD data, which exhibits inherent serial correlations and heteroscedasticity (unequal variances). Ordinary least-squares (OLS) regression produces statistically inefficient estimates with underestimated uncertainties [22].

Generalized least-squares (GLS) regression addresses these limitations by incorporating the covariance matrix (\Sigma) of the observed MSD values:

[ \hat{\beta} = (A^\intercal \Sigma^{-1} A)^{-1} A^\intercal \Sigma^{-1} x ]

where (A) is the model matrix ([1 \quad t]), (t) is the vector of observed times, and (x) is the observed MSD vector [22].

Bayesian regression provides a powerful alternative, generating a posterior probability distribution for the regression coefficients that fully accounts for data uncertainty. The posterior distribution (p(m|x)) for a linear model (m = 6D^*t + c) given observed data (x) is:

[ p(m|x) = \frac{p(x|m)p(m)}{p(x)} ]

where (p(x|m)) is the likelihood function [22].

For sufficiently large MD datasets, the central limit theorem justifies modeling the MSD as a multivariate normal distribution with log-likelihood:

[ \log p(x|m) = -\frac{k}{2} \log(2\pi) - \frac{1}{2} \log |\Sigma| - \frac{1}{2} (x - Am)^\intercal \Sigma^{-1} (x - Am) ]

where (k) is the number of time intervals [22].

Table 2: Comparison of Regression Methods for Diffusion Coefficient Estimation

| Method | Key Assumptions | Statistical Efficiency | Uncertainty Estimation | Applicability to MSD Data |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ordinary Least-Squares (OLS) | Data are independent and identically distributed | Low | Significant underestimation | Poor - violates key assumptions |

| Weighted Least-Squares (WLS) | Data are independent but heteroscedastic | Moderate | Underestimation | Moderate - accounts for heteroscedasticity only |

| Generalized Least-Squares (GLS) | Data are correlated and heteroscedastic | Maximum (achieves Cramér-Rao bound) | Accurate with known covariance matrix | Excellent - accounts for all correlation structure |

| Bayesian Regression | Data are correlated and heteroscedastic | Maximum | Accurate posterior distribution | Excellent - naturally incorporates full uncertainty |

Experimental Validation and Applications

Validation in Complex Fluids

The Stokes-Einstein-Sutherland relation has been extensively validated in diverse fluid systems through molecular dynamics simulations. In two-dimensional strongly coupled dusty plasmas (SC-DPs), EMD simulations have demonstrated that the Einstein relation accurately predicts diffusion coefficients ((D_E)) in normal diffusion regimes, particularly in cold liquid states [18].

Notably, comparative studies of Green-Kubo ((DG)) and Einstein-based ((DE)) diffusion coefficients reveal that both decrease linearly with increasing coupling parameter (\Gamma) in warm liquid states and increase with increasing screening parameter (\kappa). At higher temperatures, (DG) and (DE) converge, indicating normal diffusion behavior consistent with the Stokes-Einstein-Sutherland framework, while they diverge at lower temperatures where anomalous diffusion mechanisms become significant [18].

Interfacial Diffusion in Molecular Systems

Molecular dynamics simulations have successfully predicted interfacial diffusion coefficients of rejuvenators in aged bitumen, with experimental validation confirming the computational results. Studies demonstrate diffusion coefficients in the range of (10^{-11}) to (10^{-10}) m²/s for various rejuvenators (bio-oil, engine-oil, naphthenic-oil, and aromatic-oil), following the diffusive capacity order: Bio-oil > Engine-oil > Naphthenic-oil > Aromatic-oil [21].

The concentration distribution of rejuvenator molecules in aged bitumen follows Fick's Second Law, and the underlying diffusion mechanism is governed by both the free volume fraction in aged bitumen and intermolecular forces between rejuvenator and aged bitumen molecules. This application highlights the utility of the Stokes-Einstein framework in predicting molecular-scale transport in complex, multi-component systems relevant to materials science and engineering [21].

Aqueous Systems and Water Models

The Stokes-Einstein relation has been systematically evaluated for various water models, including OPC, OPC3, TIP4P/2005, TIP4P-FB, and TIP3P-FB. For these models, the microscopic version of the relation without hydrodynamic radius:

[ \frac{D\eta\Delta}{kB T} = \alpha{SE} ]

shows excellent agreement, with the coefficient (\alpha_{SE}) remaining relatively constant across different thermodynamic conditions [19].

This consistency across water models demonstrates the robustness of the Stokes-Einstein framework, even for a highly anomalous liquid like water that exhibits numerous deviations from simple fluid behavior. The relation holds despite significant variations in predicted absolute values of viscosity and diffusion coefficients between different water models, particularly at lower temperatures [19].

Advanced Research Applications

Machine Learning Approaches

Recent advances have integrated machine learning methods with molecular dynamics to develop accurate predictive models for diffusion coefficients. Symbolic regression (SR), a supervised machine learning technique, has been employed to derive analytical expressions for self-diffusion coefficients in molecular fluids based on macroscopic properties [20].

For bulk fluids, the general form of these SR-derived expressions is:

[ D{SR}^* = \alpha1 T^{\alpha_2} \rho^{\alpha3} - \alpha4 ]

where (T^) and (\rho^) are reduced temperature and density, and (\alpha_i) are fluid-specific parameters [20].

This approach successfully captures the known physical behavior of diffusion coefficients: linear dependence on temperature (higher temperatures enhance thermal movement and promote diffusion) and inverse relationship with density (low-density fluids exhibit higher diffusion coefficients) [20].

Confined Systems and Nanoscale Transport

In confined nanochannels, the Stokes-Einstein framework requires modification to account for geometric constraints and surface interactions. Symbolic regression analyses reveal that pore size ((H^*)) becomes an additional critical parameter influencing diffusion coefficients in confined systems [20].

Fluid diffusion coefficients generally increase with channel width, approaching bulk values as the channel width exceeds a characteristic scale. Interestingly, for large pore sizes, diffusion coefficients may even exceed bulk values due to structural modifications induced by confinement [20].

Universal Scaling Relations

Research across diverse fluid systems has revealed universal scaling behavior consistent with the microscopic Stokes-Einstein relation without hydrodynamic radius. This relation has been validated for:

- Coulomb and screened Coulomb (complex plasma) fluids [19]

- Lennard-Jones fluids and inverse power law repulsive particle fluids [19]

- Hard sphere fluids and Weeks-Chandler-Andersen fluids [19]

- Real liquids including liquid iron, dense supercritical methane, and silicon melt [19]

- Molecular fluids including linear (N₂, O₂, CO₂), chain (n-alkanes), and discotic molecules [19]

The consistent observation of Stokes-Einstein scaling across this diverse range of systems suggests underlying universal principles governing atomic and molecular transport in dense fluids.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Materials and Computational Tools

| Reagent/Software | Function/Application | Specifications/Properties |

|---|---|---|

| Lennard-Jones Potential | Interaction potential for MD simulations | (\phi(r) = 4\epsilon[(\sigma/r)^{12} - (\sigma/r)^6]); Common choice for simplicity and computational efficiency [20] |

| Water Models (OPC, TIP4P, TIP3P) | Molecular representation of water | Rigid or flexible models with specific charge distributions optimized to reproduce water properties [19] |

| kinisi Python Package | Analysis of diffusion from MD trajectories | Implements Bayesian regression for optimal estimation of D* from MSD data [22] |

| Green-Kubo Formalism | Alternative method for diffusion calculation | Based on integration of velocity autocorrelation function: (D = \frac{1}{3}\int_0^\infty \langle \mathbf{v}(t)\cdot\mathbf{v}(0)\rangle dt) [18] [19] |

| Symbolic Regression Framework | Machine learning for equation discovery | Genetic programming approach to derive physically consistent expressions for diffusion coefficients [20] |

The Stokes-Einstein-Sutherland equation continues to serve as a fundamental pillar in the understanding of diffusion processes, bridging microscopic dynamics and macroscopic transport across an expanding range of scientific applications. Contemporary research has validated its utility in systems ranging from complex plasmas to molecular fluids, while revealing important modifications required for confined systems and anomalous diffusion regimes.

Advanced computational methods, particularly molecular dynamics simulations enhanced by sophisticated regression techniques and machine learning approaches, have extended the applicability of the Stokes-Einstein framework while providing deeper insights into its limitations. The development of universal scaling relations and their successful application to diverse fluid systems underscores the robustness of this century-old relation.

For researchers in drug development and materials science, the Stokes-Einstein-Sutherland equation provides an essential tool for predicting molecular transport, with modern computational methods offering increasingly accurate parameterization for specific systems of interest. The ongoing integration of machine learning with physical principles promises further enhancements in predictive capability while maintaining the physical interpretability that has made the Stokes-Einstein relation an enduring component of the scientific toolkit.

The Fluctuation-Dissipation Theorem (FDT) stands as a cornerstone of statistical physics, providing a profound and fundamental connection between the random thermal fluctuations of a system at equilibrium and its response to external perturbations. This relation serves as the foundational bridge linking the microscopic, random motion of particles to macroscopic, observable transport properties. Within the specific context of Einstein relation diffusion coefficient molecular dynamics research, the FDT provides the theoretical justification for using equilibrium molecular dynamics simulations to predict kinetic properties and diffusion behavior, forming an essential link between computational modeling and experimental observation [23].

This technical guide examines the core principles of the fluctuation-dissipation relation, with a specific focus on the celebrated Einstein relation that connects diffusion, mobility, and temperature. We will delve into the quantitative formulations, detailed computational methodologies for its application in molecular dynamics, current research trends extending these concepts, and the essential tools that enable this research.

Theoretical Foundations

The Fluctuation-Dissipation Theorem

The Fluctuation-Dissipation Theorem exists in several formulations, but its core principle is universal: the spontaneous fluctuations of a physical variable around its equilibrium value are quantitatively related to the dissipation of energy, or the system's linear response, when the same variable is subjected to an external force [24]. In qualitative terms, the same microscopic molecular collisions that cause a suspended particle to jiggle erratically (Brownian motion) also cause it to experience friction, or drag, when it is deliberately pulled through the fluid [24] [23].

The general formulation of the FDT states that for a system in thermal equilibrium at temperature ( T ), the power spectrum ( Sx(\omega) ) of the fluctuations in a variable ( x ) is related to the imaginary part of the corresponding susceptibility ( \hat{\chi}(\omega) ) that describes the system's response to a conjugate force ( f(t) ) [24]: [ Sx(\omega) = - \frac{2 kB T}{\omega} \operatorname{Im} \hat{\chi}(\omega) ] where ( kB ) is the Boltzmann constant. This general relation applies to a wide range of classical and quantum mechanical systems [24].

The Einstein Relation

A seminal and historically pivotal special case of the FDT is the Einstein relation (also known as the Einstein-Smoluchowski relation) for diffusion. This relation, independently discovered by William Sutherland, Albert Einstein, and Marian Smoluchowski in the early 1900s, provides a direct and simple connection between a particle's diffusion and its mobility [9].

The classical form of the Einstein relation is expressed as: [ D = \mu \, k_B T ] where:

- ( D ) is the diffusion coefficient,

- ( \mu ) is the mobility, defined as the ratio of the particle's terminal drift velocity to an applied force (( \mu = v_d / F )),

- ( k_B ) is the Boltzmann constant,

- ( T ) is the absolute temperature [9].

This equation is a quintessential fluctuation-dissipation relation, where the diffusion coefficient ( D ) characterizes the fluctuations (random motion), and the mobility ( \mu ) characterizes the dissipative response to an applied force [9]. Its derivation elegantly shows that the inherent random motion of a particle and its frictional resistance to a directed force share a common microscopic origin.

Table 1: Special Cases of the Einstein Relation

| Relation Name | System / Condition | Mathematical Form | Key Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Einstein-Smoluchowski | Charged Particles | ( D = \dfrac{\muq \, kB T}{q} ) | ( \mu_q ): Electrical mobility, ( q ): Particle charge [9] |

| Stokes-Einstein-Sutherland | Spherical Particles in Liquid (Low Reynolds number) | ( D = \dfrac{k_B T}{6 \pi \, \eta \, r} ) | ( \eta ): Dynamic viscosity, ( r ): Hydrodynamic radius [9] [25] |

| Quantum Case | Fermi Gas / Fermi Liquid (e.g., electrons in metals) | ( D = \dfrac{\muq \, EF}{q} ) | ( E_F ): Fermi energy [9] |

| Nernst-Einstein | Ionic conductivity of an electrolyte | ( \Lambdae = \dfrac{zi^2 F^2}{RT}(D{+} + D{-}) ) | ( \Lambdae ): Molar conductivity, ( zi ): Ion charge, ( F ): Faraday constant, ( D{+}, D{-} ): Cation/Anion diffusivities [9] |

Computational & Experimental Methodologies

Molecular Dynamics and the Einstein Relation

In molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, the Einstein relation provides the most direct and widely used method for calculating the self-diffusion coefficient. This approach leverages the connection between macroscopic diffusion and the microscopic mean-squared displacement (MSD) of particles [10] [26].

The core methodology involves tracking the trajectories of atoms over time and calculating their MSD. For a three-dimensional system, the self-diffusion coefficient ( D\alpha ) for a species ( \alpha ) is given by the Einstein-Smoluchowski relation: [ D\alpha = \frac{1}{6} \lim{t \to \infty} \frac{d}{dt} \left\langle \left| \mathbf{r}i(t + t0) - \mathbf{r}i(t0) \right|^2 \right\rangle{t0} ] where ( \mathbf{r}i(t) ) is the position of atom ( i ) at time ( t ), and the angle brackets denote an average over all atoms of the same species and all possible time origins ( t_0 ) [4] [26]. The diffusion coefficient is extracted from the slope of the linear portion of the MSD versus time curve.

The following workflow diagram illustrates the standard computational protocol for determining diffusion coefficients from molecular dynamics simulations using the Einstein relation:

Diagram 1: Molecular Dynamics Workflow for Diffusion Coefficient Calculation.

Protocol for Accurate Diffusion Coefficient Calculation

Accurate determination of ( D ) from MD simulations requires careful execution and analysis. The following protocol, implemented in tools like the MD2D Python module, outlines key steps and considerations [26]:

System Preparation and Equilibration:

- Construct a simulation cell with periodic boundary conditions to mimic an infinite system.

- Select an appropriate force field (e.g., a polarized ion model for ionic melts [27]).

- Equilibrate the system thoroughly in the desired ensemble (NVT or NPT) until energy and pressure stabilize.

Production Trajectory:

- Run a sufficiently long production simulation to collect atomic trajectories. The simulation must be long enough to capture the diffusive regime, typically tens to hundreds of picoseconds, depending on the system [4].

MSD Calculation and Ballistic Exclusion:

- Parse the trajectory files to compute the MSD for each species.

- A critical step is to recognize and exclude the initial ballistic motion regime from the linear fit. In this short-time regime, particle motion is governed by its initial velocity, leading to MSD ( \propto t^2 ), which invalidates the Einstein relation. Including this regime introduces significant error [26].

Linear Fitting and Error Estimation:

- Perform a linear fit on the MSD curve in the confirmed diffusive regime (where MSD ( \propto t )).

- To reliably estimate the statistical uncertainty, use block averaging techniques. This involves dividing the total trajectory into multiple segments (blocks), calculating ( D ) for each block, and then using the standard deviation of these block values as the error estimate [4] [26].

Finite-Size Correction:

- Finite simulation boxes introduce hydrodynamic constraints that affect the calculated diffusion coefficient. The result from a finite cell, ( D{MD} ), must be corrected to the thermodynamic limit, ( D{\infty} ), using a relation derived from hydrodynamic arguments [26]: [ D{\infty} = D{MD} + \frac{k_B T \xi}{6 \pi \eta L} ] where ( \eta ) is the shear viscosity, ( L ) is the box length, and ( \xi ) is a constant. The viscosity ( \eta ) can often be calculated from the same MD simulation [26].

Current Research and Applications

The principles of the fluctuation-dissipation relation and the Einstein formula remain highly relevant in modern computational materials science and drug development, with active research focused on both methodological refinements and applications to complex systems.

Methodological Advances and Validation

Recent research efforts have been dedicated to enhancing the accuracy and efficiency of diffusion coefficient calculations:

- Reducing Uncertainty: Advanced techniques focus on isolating the early ballistic regime and applying thermodynamic corrections, including viscosity adjustments, to refine estimates and improve accuracy [10].

- High-Throughput Automation: Frameworks like the SLUSCHI package have been extended to automate first-principles MD calculations of diffusion coefficients, enabling high-throughput screening of transport properties in materials such as Al-Cu liquid alloys and oxide materials like Li₇La₃Zr₂O₁₂ [4].

- Excess Entropy Scaling: Complementary approaches that relate diffusion coefficients to the system's excess entropy have emerged as promising routes for rapid estimation, minimizing computational expense while retaining precision [10].

Applications in Complex Systems

The application of these methods often reveals the nuances and limitations of classical models in real-world systems:

- Molten Salts for Nuclear Reactors: MD studies of LiF-NaF molten salts, used as coolants in molten salt reactors, show that while self-diffusion coefficients increase linearly with LiF content, the Nernst-Einstein equation tends to overestimate the ionic conductivity. This highlights the importance of ion correlations not captured by the simple model and demonstrates the need for MD simulations for accurate property prediction [27].

- Drug Discovery and Development: The Stokes-Einstein relation provides a theoretical pathway to estimate the diffusion coefficients of small drug molecules based on their calculated molecular radii. This is valuable for predicting passive transport and distribution in the body, such as the diffusion of central nervous system drugs in the brain after they cross the blood-brain barrier. Computationally derived diffusion coefficients can thus serve as an additional molecular descriptor in drug screening [25].

Table 2: Experimentally Derived vs. Simulated Diffusion Coefficients for Selected Molecules in Water (T=298 K)

| Molecule | Molecular Weight (g/mol) | Experimental D₀ (10⁻⁶ cm²/s) | Simulated Dₑ (10⁻⁶ cm²/s) | Deviation (Dₑ - D₀) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Xylose | 150 | 7.50 | 7.24 | -0.26 |

| Fructose | 180 | 6.93 | 6.84 | -0.09 |

| Glucose | 180 | 6.79 | 6.65 | -0.14 |

| Sucrose | 342 | 5.23 | 5.07 | -0.16 |

| Aspirin | 180 | 6.74 | 6.65 | -0.09 |

| Salbutamol | 239 | 5.94 | 5.91 | -0.03 |

| Data adapted from [25] |

The Scientist's Toolkit

Successful research involving fluctuation-dissipation relations and diffusion requires a combination of specialized software, theoretical frameworks, and computational protocols.

Table 3: Essential Research Tools and Reagents

| Tool / Solution | Type | Primary Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| MD2D | Python Module | Accurate determination of self-diffusion coefficient from MD; identifies ballistic regime; performs finite-size corrections. | Analysis of diffusion in liquids and geological materials [26]. |

| SLUSCHI-Diffusion | Computational Workflow | Automated first-principles calculation of diffusion coefficients from VASP MD trajectories. | High-throughput screening of diffusivity in alloys and oxide materials [4]. |

| Polarized Ion Model (PIM) | Force Field | Describes ionic interactions including polarization effects for high accuracy in molten salts. | Simulating local structure and transport in LiF-NaF systems [27]. |

| Green-Kubo Formalism | Theoretical Framework | Alternative to Einstein relation; calculates transport coefficients via time integrals of autocorrelation functions. | Calculating ionic conductivity; compared against Nernst-Einstein results [10] [27]. |

| Stokes-Einstein Equation | Theoretical Model | Relates diffusion coefficient to hydrodynamic radius and viscosity. | Estimating diffusion coefficients of small molecules/drugs from their modeled radius [25]. |

This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of three foundational concepts in molecular dynamics (MD) simulations: Mean Squared Displacement (MSD), force fields, and periodic boundary conditions (PBCs). Framed within Einstein relation diffusion coefficient research, this whitepaper details theoretical frameworks, practical implementation methodologies, and critical considerations for researchers applying MD techniques to drug development and materials science. By integrating quantitative data tables, experimental protocols, and visual workflows, we establish robust guidelines for accurately calculating transport properties and mitigating computational artifacts in molecular simulations.

Molecular dynamics simulations serve as a computational microscope, enabling researchers to investigate molecular-level processes that govern diffusion phenomena in biological and materials systems. At the heart of calculating transport properties like diffusion coefficients lies the Einstein relation, which connects microscopic particle motion to macroscopic diffusion through mean squared displacement analysis [10]. The accuracy of these calculations depends critically on two fundamental components: the force fields that describe interatomic interactions, and the periodic boundary conditions that define the simulation environment. This whitepaper examines these interconnected concepts within the context of diffusion coefficient research, providing technical guidance for scientists pursuing molecular-level understanding of diffusion processes in drug discovery and development.

Theoretical Foundations

Mean Squared Displacement and the Einstein Relation

The Mean Squared Displacement (MSD) quantifies the average squared distance particles travel over time, serving as the primary metric for characterizing molecular mobility in MD simulations. According to the Einstein formulation, MSD for a three-dimensional system is computed as:

[MSD(r{d}) = \bigg{\langle} \frac{1}{N} \sum{i=1}^{N} |r{d} - r{d}(t0)|^2 \bigg{\rangle}{t_{0}}]

where (N) represents the number of equivalent particles, (r) denotes atomic coordinates, (d) indicates dimensionality, and angle brackets represent averaging over multiple time origins [28]. The Einstein relation connects MSD to the diffusion coefficient (D) through:

[Dd = \frac{1}{2d} \lim{t \to \infty} \frac{d}{dt} MSD(r_{d})]

where (d) represents the dimensionality of the MSD [28]. For calculations in three dimensions ((d) = 3), this simplifies to (D = \frac{1}{6} \lim_{t \to \infty} \frac{d}{dt} MSD(t)). This relationship enables the determination of self-diffusivity from the slope of the MSD curve in the linear regime [28] [9].

Table 1: Key Equations in Diffusion Coefficient Calculation

| Equation | Formula | Parameters | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Einstein MSD | (MSD(r{d}) = \bigg{\langle} \frac{1}{N} \sum{i=1}^{N} |r{d} - r{d}(t0)|^2 \bigg{\rangle}{t_{0}}) | (N): particle count; (r): coordinates; (d): dimensionality | Fundamental MSD calculation from particle trajectories |

| Diffusion Coefficient | (Dd = \frac{1}{2d} \lim{t \to \infty} \frac{d}{dt} MSD(r_{d})) | (D_d): diffusion coefficient; (d): dimensionality | Relating MSD slope to diffusivity |

| Stokes-Einstein-Sutherland | (D = \frac{k_{B}T}{6\pi\eta r}) | (k_B): Boltzmann constant; (T): temperature; (\eta): viscosity; (r): hydrodynamic radius | Estimating diffusion coefficients for spherical particles in solution [9] |

Force Fields in Molecular Dynamics

Force fields provide the mathematical framework and parameter sets that describe the potential energy surface of a molecular system, dictating how atoms interact during simulations. In diffusion studies, the choice of force field significantly impacts the accuracy of calculated transport properties through its influence on molecular conformation and intermolecular interactions [25]. Recent evaluations of methane/n-hexane mixtures highlight the delicate interplay between force field parameterization and simulation box size, reinforcing the need for systematic approaches in MD studies [10].

In practice, force fields encompass various energy terms:

[U{\text{total}} = U{\text{bond}} + U{\text{angle}} + U{\text{torsion}} + U{\text{electrostatic}} + U{\text{van der Waals}}]

where accurate parameterization of non-bonded interactions ((U{\text{electrostatic}}) and (U{\text{van der Waals}})) proves particularly crucial for realistic diffusion behavior [25]. For drug-sized molecules, the Molecular Operating Environment (MOE) software with force fields like MMFF94x has been used to generate stable conformers for subsequent diffusion analysis [25].

Periodic Boundary Conditions

Periodic boundary conditions (PBCs) represent a computational method that approximates an infinite system by simulating a small unit cell surrounded by identical images in all spatial directions [29]. When a particle exits the central simulation box through one face, it simultaneously re-enters through the opposite face, maintaining particle number conservation [29]. This approach eliminates surface effects that would otherwise dominate small simulation systems but introduces specific computational artifacts that must be addressed.

PBCs generate a special statistical mechanical ensemble (EVNMG) that conserves not only total energy (E), volume (V), and particle number (N), but also total linear momentum (M) and the generator of infinitesimal Galilean boosts (G) [30]. This has implications for ensemble averages of spatial coordinates and can introduce subtle finite-size effects in calculated properties [30].

Computational Methodologies

MSD Calculation and Diffusion Coefficient Determination

Accurate computation of diffusion coefficients from MD trajectories requires careful implementation of MSD calculations and appropriate linear regression. The following protocol outlines the standard approach:

Trajectory Preparation: Use unwrapped coordinates to ensure correct displacement calculations. Wrapped coordinates that adhere to periodic boundaries introduce discontinuities in particle paths and invalidate MSD results [28]. In GROMACS, this can be achieved using

gmx trjconvwith the-pbc nojumpflag [28].MSD Computation: Select appropriate dimensionality (

xyzfor 3D, or individual components for anisotropic diffusion) and algorithm. Fast Fourier Transform (FFT)-based approaches from thetidynamicspackage offer O(N log N) scaling compared to simple algorithms with O(N²) scaling [28].Linear Regression: Identify the appropriate time range for linear fitting, typically excluding early ballistic regime where MSD ∝ t² and late times where statistics are poor [28] [26]. The MD2D Python module implements automated identification of the ballistic stage exclusion [26]. In GROMACS, default fitting ranges from 10% to 90% of the trajectory can be used with

-beginfit -1and-endfit -1[31].Error Estimation: Calculate uncertainties through block averaging or by comparing diffusivities from multiple trajectory segments [26] [31]. GROMACS provides error estimates based on the difference between diffusion coefficients from the first and second halves of the fit interval [31].

Diagram 1: MSD Calculation Workflow for Diffusion Coefficient Determination

Finite-Size Corrections and Artifact Mitigation

The finite size of simulation boxes under PBCs introduces systematic errors in calculated diffusion coefficients. Hydrodynamic interactions become artificially truncated due to the periodic images, reducing the calculated diffusivity [26]. Several correction strategies have been developed:

Thermodynamic Limit Extrapolation: Calculate diffusion coefficients for multiple system sizes and extrapolate to infinite system size [26].

Yeh-Hummer Correction: Apply analytical corrections based on the system size and viscosity [28] [26].

Viscosity Calculations: Compute system viscosity to apply hydrodynamic corrections, as implemented in the MD2D module [26].

Additionally, PBCs can introduce artifacts when the simulation box is too small, causing molecules to interact with their own images—a particular concern for flexible macromolecules like proteins or polymers [29]. A minimum of 1 nm of solvent around molecules of interest in all dimensions is generally recommended to minimize this effect [29].

Table 2: Common MD Software and Modules for Diffusion Coefficient Calculation

| Software/Module | Key Features | MSD Algorithm | Special Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| MDAnalysis.analysis.msd | Python library, Einstein relation implementation, multiple dimensionality support | Windowed averaging or FFT-based (with tidynamics) | Requires unwrapped coordinates; FFT algorithm reduces computational complexity [28] |

| GROMACS gmx msd | Integrated with MD package, molecular MSD options, automated fitting | Multiple time origins with -trestart | Default fitting range (10%-90%); error estimate from fit halves difference [31] |

| MD2D | Python module, ballistic stage identification, finite-size corrections | Ensemble averaging over time intervals | Explicitly excludes ballistic regime; calculates viscosity for corrections [26] |

Practical Applications in Drug Development

Diffusion Coefficient Estimation for Small Molecules

Theoretical estimation of diffusion coefficients provides valuable insights for drug screening and delivery system design. The Stokes-Einstein equation enables approximation of molecular diffusivity based on molecular radius:

[D = \frac{k_B T}{6 \pi \eta r}]

where (r) represents the molecular radius, (T) is temperature, (\eta) is solvent viscosity, and (k_B) is Boltzmann's constant [25] [9]. For small drug-like molecules, two radius definitions have shown utility:

- Simple radius (r_s): Derived from van der Waals volume assuming spherical geometry

- Effective radius (r_e): Incorporates radius of gyration with a correction factor (K ≈ 1.29) to account for molecular shape and hydration effects [25]

Studies indicate that for molecules with strong hydration ability, diffusion coefficients are best given by re, while for other compounds, rs provides the best coefficients, with deviations of approximately 0.3 × 10⁻⁶ cm²/s from experimental data [25].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Diffusion Studies

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function in Diffusion Research |

|---|---|---|

| MD Simulation Packages | GROMACS, NAMD, LAMMPS, AMBER | Generate molecular trajectories for MSD analysis through numerical integration of equations of motion [31] |

| Analysis Toolkits | MDAnalysis, MDTraj, MD2D | Process trajectory data to compute MSD and extract diffusion coefficients; implement finite-size corrections [28] [26] |

| Visualization Software | VMD, PyMOL, Chimera | Visualize molecular trajectories, verify PBC handling, and analyze molecular conformations [25] |

| Specialized Modules | MDAnalysis.analysis.msd, GROMACS gmx msd | Implement optimized algorithms for MSD calculation and diffusion coefficient estimation [28] [31] |

Technical Considerations and Best Practices

Critical Implementation Details

Successful calculation of diffusion coefficients requires attention to several technical aspects:

Unwrapped Trajectories: MSD analysis must use unwrapped coordinates that account for molecules crossing periodic boundaries. Most MD packages output wrapped coordinates by default, requiring explicit unwrapping procedures [28].

Sampling Considerations: Maintain relatively small elapsed time between saved trajectory frames to adequately capture diffusion processes. For large systems, judicious use of frame skipping may be necessary to manage memory requirements [28].

Electrostatic Neutrality: Systems with PBCs must have zero net electrostatic charge to avoid infinite summation of Coulomb interactions. Counterions should be added to neutralize charged systems [29].

Diagram 2: Periodic Boundary Conditions: Effects and Mitigation Strategies

Validation and Error Analysis

Robust diffusion coefficient calculation requires comprehensive validation:

MSD Linearity: Verify linearity of MSD versus time in the fitting region using log-log plots where the diffusive regime shows slope = 1 [28].

Convergence Testing: Ensure sufficient simulation time for statistical convergence, typically requiring MSD values that exceed the square of the system size [26].

Ensemble Averaging: Exploit the MD2D approach of calculating diffusion coefficients at different time intervals and performing ensemble averages to estimate uncertainties [26].

Force Field Validation: Compare simulated diffusion coefficients with experimental values where available, particularly when developing new force field parameters [25].

Mean Squared Displacement, force fields, and periodic boundary conditions represent interconnected components in the molecular dynamics determination of diffusion coefficients via the Einstein relation. Accurate implementation requires both theoretical understanding and practical awareness of computational artifacts and their mitigation. As MD simulations continue to bridge microscopic dynamics and macroscopic transport properties in drug discovery contexts, rigorous application of the methodologies outlined in this whitepaper will enhance the reliability of computational predictions and strengthen the connection between molecular modeling and experimental observations in pharmaceutical development.

Implementing the Einstein Relation in MD Simulations: From Code to Application

Within the framework of Einstein relation diffusion coefficient molecular dynamics research, the ability to accurately compute transport properties from atomic-scale simulations represents a cornerstone of computational materials science and drug development. Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations provide a powerful bridge between microscopic particle motion and macroscopic transport properties, enabling researchers to predict diffusion coefficients without extensive experimental measurement [10]. This technical guide provides a comprehensive, step-by-step workflow for extracting diffusion coefficients from atomic trajectories, detailing both fundamental principles and practical implementation strategies essential for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. The methodologies outlined here support diverse applications from carbon sequestration and industrial process design to pharmaceutical development and drug delivery system analysis [10] [25].

The fundamental physical relationship underlying these calculations is the Einstein-Smoluchowski equation, which relates mean squared displacement (MSD) to the diffusion coefficient [25]. For systems where diffusing molecules can be approximated as spheres, the Stokes-Einstein equation provides an alternative approach by connecting the diffusion coefficient to molecular radius, solvent viscosity, and temperature [25]. This guide explores both conceptual frameworks and their practical implementation through modern computational tools.

Core Principles and Theoretical Foundation

Fundamental Relationships

The calculation of diffusion coefficients in molecular dynamics simulations rests on several well-established physical relationships that connect atomic-scale motion to macroscopic transport properties.

Einstein-Smoluchowski Equation: This foundational relation describes Brownian motion where the mean-square travel distance of a particle diffusing in one dimension (x) is given by (\overline{x^2} = 2Dt), where (D) is the diffusion coefficient and (t) is time [25]. In three dimensions, this extends to the Einstein relation expressed in terms of mean squared displacement (MSD): (D\alpha = \frac{1}{2d} \frac{d}{dt} \langle | \mathbf{r}i(t+t0) - \mathbf{r}i(t0) |^2 \rangle{t0}), where (d=3) represents dimensionality, and the angle brackets denote averaging over time origins (t0) [4].

Stokes-Einstein Equation: For systems where molecules can be approximated as spheres, the diffusion coefficient relates to hydrodynamic properties through (D = kBT / (6\pi r \eta0)), where (kB) is the Boltzmann constant, (T) is absolute temperature, (r) is the molecular radius, and (\eta0) is solvent viscosity [25]. This relationship enables estimation of diffusion coefficients from molecular geometry, particularly useful in drug development where molecular radii can be computed from stable conformers [25].

Advanced Methodological Considerations

Recent advances in MD simulations of diffusion coefficients have focused on addressing several computational challenges. Finite-size effects introduce uncertainties that can be mitigated through systematic approaches to force field selection and appropriate correction methods [10]. The early ballistic regime, where particle motion hasn't yet reached the diffusive scale, requires specialized handling through techniques such as isolating the ballistic stage and applying thermodynamic corrections including viscosity adjustments [10].

Excess entropy scaling (EES) has emerged as a promising alternative approach, relating structural disorder of a system (as quantified by excess entropy) to transport properties with reduced sampling error compared to traditional methods based on Einstein-Helfand and Green-Kubo relations [10]. This method offers particular advantages in computational efficiency while retaining precision.

Table 1: Key Physical Relationships for Diffusion Coefficient Calculation

| Relation | Mathematical Form | Application Context | Key Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Einstein-Smoluchowski | (\overline{x^2} = 2Dt) | Brownian motion in 1D | Mean square displacement, time |

| Einstein Relation (3D) | (D\alpha = \frac{1}{6} \frac{d}{dt} \langle | \mathbf{r}i(t+t0) - \mathbf{r}i(t0) |^2 \rangle{t_0}) | MD simulations of liquids/solids | MSD, dimensionality (d=3) |

| Stokes-Einstein | (D = kBT / (6\pi r \eta0)) | Hydrodynamic approximation | Temperature, molecular radius, viscosity |

Computational Tools and Research Reagents

The Scientist's Toolkit

Implementing a robust workflow for diffusion coefficient calculation requires specialized software tools and computational resources. The following table summarizes essential components of the research toolkit:

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools for Diffusion Coefficient Analysis

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Implementation Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| MD Simulation Engines | Software | Generate atomic trajectories | VASP, GROMACS, MOE with MMFF94x force field |

| Trajectory Analysis Tools | Software | Process MD outputs, compute MSD | SLUSCHI-Diffusion, gmx msd, VASPKIT |

| Force Fields | Parameter sets | Define interatomic interactions | MMFF94x, specialized potentials for specific systems |

| Ab Initio Calculators | Software | First-principles MD | DFT in VASP, other plane-wave codes |

| Diffusion Modules | Specialized code | Automate diffusion analysis | SLUSCHI-Diffusion, custom scripts |