Comparative Perturbed-Ensembles Analysis: Decoding Functional Protein Dynamics for Drug Discovery

This article explores Comparative Perturbed-Ensembles Analysis, a powerful computational approach that compares conformational ensembles from molecular dynamics simulations under different perturbations to reveal functional protein dynamics.

Comparative Perturbed-Ensembles Analysis: Decoding Functional Protein Dynamics for Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article explores Comparative Perturbed-Ensembles Analysis, a powerful computational approach that compares conformational ensembles from molecular dynamics simulations under different perturbations to reveal functional protein dynamics. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, we cover the foundational shift from static to dynamic structure paradigms, detailed methodologies for implementing the analysis, strategies to overcome computational and analytical challenges, and rigorous validation against experimental data. By synthesizing insights from recent advances in AI structure prediction and ensemble analysis tools, this guide provides a comprehensive resource for leveraging protein dynamics to understand allosteric mechanisms and accelerate the development of conformation-specific therapeutics.

From Static Structures to Dynamic Ensembles: The Paradigm Shift in Protein Science

Proteins are not static, rigid structures; they are inherently dynamic molecules whose functional motions—from loop rearrangements to secondary structure shifts—play pivotal roles in virtually all biological processes, including catalysis, signaling, and molecular interactions [1]. These conformational changes, often occurring on microsecond or slower timescales, are governed by an energy landscape that dictates the populations and interconversion rates of discrete states [1]. The time dependence of biomolecular structural changes remains underexplored yet is essential for defining the roles of transient states and dynamically driven allostery in protein function. Traditional static structural methods, such as X-ray crystallography, provide invaluable but limited snapshots of this complex dynamical repertoire. This application note explores the framework of comparative perturbed-ensembles analysis, a powerful approach for detecting functional dynamics in proteins, and details contemporary protocols and tools enabling this research within drug discovery and biotechnology contexts.

Comparative Perturbed-Ensembles Analysis: A Core Analytical Framework

The central challenge in molecular dynamics (MD) simulation lies not just in sampling the conformational energy landscape but in analyzing the resulting trajectories to extract biologically relevant information. The comparative perturbed-ensembles analysis approach addresses this by systematically comparing two or more conformational ensembles of a system generated by MD simulations under distinct perturbation conditions [2].

In this framework, perturbations can include different sequence variations (e.g., single-point mutations), ligand-binding conditions, post-translational modifications, or other physical/chemical modifications. Each simulation must be sufficiently long (e.g., microsecond-long) to ensure adequate sampling of local substates. Subsequently, sophisticated bioinformatic and statistical tools are applied to extract function-related information, including:

- Principal component analysis (PCA) to identify essential dynamics

- Residue-residue contact analysis

- Difference contact network analysis (dCNA) based on graph theory

- Statistical analysis of side-chain conformations [2]

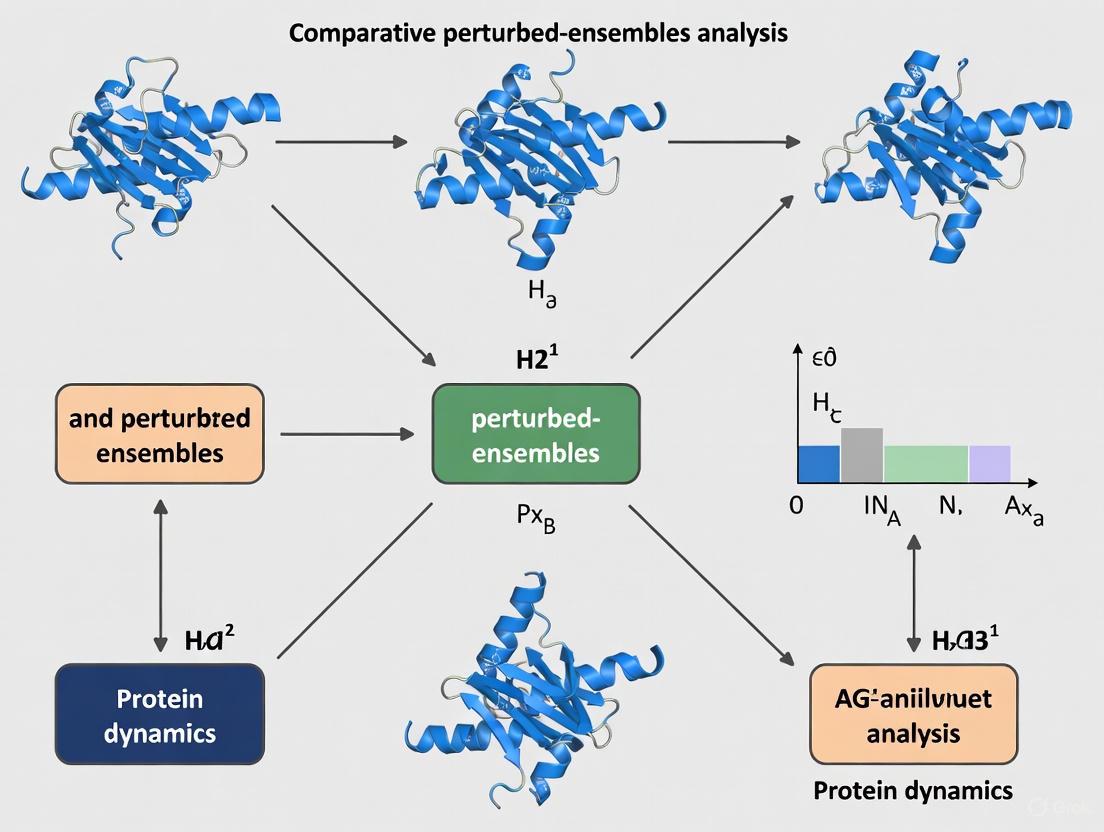

By comparing distinct conformational ensembles, functional micro- to millisecond dynamics can be inferred—a timescale difficult to reach in a single simulation and even more challenging to link to specific functions without comparative analysis [2]. The workflow of this approach is illustrated in Diagram 1.

Diagram 1: Workflow of Comparative Perturbed-Ensembles Analysis

Applications and Validation

This approach has been successfully implemented to identify allosteric pathways in cyclophilin A (CypA), revealing two pathways consistent with NMR experiments and a novel third pathway [2]. It has further enabled dynamical-evolution analysis across human cyclophilin isoforms (CypA, CypD, and CypE), identifying both conserved and divergent conformational dynamics [2]. Computational findings from this approach require validation with experimental data, creating a closed loop of hypothesis generation and testing that significantly enhances the reliability of the functional dynamics detected.

Quantitative Benchmarks for Protein Dynamics Methodologies

The field of protein dynamics simulation employs diverse methodologies, each with distinct strengths, limitations, and performance characteristics. The table below summarizes key quantitative benchmarks for current technologies:

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Protein Dynamics Analysis Methods

| Method | Timescale | Spatial Resolution | Throughput | Key Applications | Sample Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Dynamics (MD) [3] [4] | Nanoseconds to milliseconds | Atomic (~1-3 Å) | Low (months on supercomputers) | Folding/unfolding pathways, allosteric mechanisms | Computational resources intensive |

| Comparative Perturbed-Ensembles MD [2] | Microseconds to milliseconds | Atomic (~1-3 Å) | Medium (multiple μs-length simulations) | Allosteric pathway identification, functional dynamics | Requires multiple simulation conditions |

| BioEmu (AI) [4] | Equilibrium ensembles | Atomic (backbone frames) | Very High (1000s structures/hour on single GPU) | Genome-scale function prediction, cryptic pocket discovery | Single protein sequence; minimal compute |

| 2DIR with ML [5] | Picoseconds to milliseconds | Backbone (Cα RMSD ~2.5-3.3 Å) | Medium (theoretical spectra generation) | Folding trajectories, unknown protein structure prediction | Experimental or theoretical 2DIR spectra |

| Stopped-Flow EPR [1] | Milliseconds | Nanoscale (spin label distances) | Low (stopped-flow measurements) | Folding pathways, allosteric changes in membrane proteins | 10-100 μg of spin-labeled protein |

These methodologies represent complementary approaches, with traditional MD simulations offering high spatial resolution but limited timescales, while emerging AI-based methods like BioEmu dramatically accelerate the sampling of equilibrium ensembles with approximately 1 kcal/mol accuracy [4]. Experimental techniques like 2DIR spectroscopy and stopped-flow EPR provide crucial experimental validation, with the latter enabling investigation of complex, biologically relevant proteins that are often only available in limited quantities [5] [1].

Experimental Protocols for Dynamic Analysis

Protocol 1: Comparative Perturbed-Ensembles MD Analysis

This protocol outlines the procedure for implementing comparative perturbed-ensembles analysis using molecular dynamics simulations [2].

4.1.1 System Preparation and Perturbation Design

- Select a protein system of interest and identify perturbation conditions relevant to biological function (e.g., wild-type vs. mutant, apo vs. holo forms, different ligand-binding states, post-translational modifications)

- Obtain initial coordinates from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) and add missing atoms using standard software tools

- For each perturbation condition, prepare separate simulation systems with identical setup aside from the introduced perturbation

4.1.2 Molecular Dynamics Simulations

- Solvate each system in explicit water using the experimental water density for the temperature of interest

- Employ energy minimization to remove steric clashes, followed by gradual heating and equilibration phases

- Production simulations:

- Perform microsecond-length simulations for each perturbation condition (current benchmarks suggest ≥1 μs)

- Use a fully flexible force field with explicit water representation

- Maintain constant temperature and pressure using appropriate thermostats and barostats

- Save trajectories at sufficient frequency (e.g., every 100 ps) to capture relevant dynamics

4.1.3 Comparative Ensemble Analysis

- Align all trajectories to a reference structure to remove global rotation and translation

- Perform principal component analysis (PCA) to identify essential collective motions:

- Construct and diagonalize the covariance matrix of atomic positional fluctuations

- Compare the projection of each ensemble onto the principal components

- Conduct residue-residue contact analysis using a distance cutoff (e.g., 4.5 Å for heavy atoms)

- Implement difference contact network analysis (dCNA):

- Construct graphs where nodes represent residues and edges represent persistent contacts

- Identify differences in network connectivity between ensembles

- Analyze side-chain torsion-angle distributions to identify significant conformational changes

4.1.4 Validation and Interpretation

- Compare computational findings with available experimental data (NMR, EPR, etc.)

- Identify statistically significant differences between ensembles (e.g., using Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests for distribution comparisons)

- Map identified dynamic pathways and allosteric networks onto protein structure for functional interpretation

Protocol 2: AI-Enhanced Equilibrium Ensemble Generation with BioEmu

BioEmu represents a transformative AI-based approach for generating protein equilibrium ensembles, offering dramatic speed improvements over traditional MD [4].

4.2.1 Input Preparation and Model Configuration

- Input requirement: Protein amino acid sequence (single-chain proteins up to ~500 residues)

- Hardware requirement: Single GPU (recommended) or CPU alternative

- Install BioEmu package and dependencies as specified in the original implementation

- Configure model parameters based on desired trade-off between sampling speed and accuracy

4.2.2 Ensemble Generation Process

- Encode the input sequence using the Evoformer module from AlphaFold2 to generate single and pairwise representations

- Feed representations into the diffusion-based denoising model, which uses coarse-grained backbone frames

- Generate structural samples through 30-50 denoising steps, producing thousands of structures per hour on a single GPU

- For thermodynamic accuracy, employ Property Prediction Fine-Tuning (PPFT) if experimental stability data (e.g., melting temperature) is available

4.2.3 Analysis of Generated Ensembles

- Cluster generated structures to identify predominant conformational states

- Calculate free energy differences between states using Boltzmann distributions

- Identify cryptic pockets by analyzing surface accessibility across the ensemble

- Compare with experimental structures (e.g., from PDB) using RMSD metrics (target: ≤3 Å for domain motions)

Protocol 3: Machine Learning-Enabled 2DIR Spectroscopy for Dynamic Structures

This protocol details the procedure for predicting dynamic protein structures from two-dimensional infrared (2DIR) spectroscopy using machine learning [5].

4.3.1 Data Preparation and Spectral Generation

- Curate a diverse set of protein structures (up to 100 residues for initial training) from RCSB PDB and SWISS-PROT

- Generate theoretical 2DIR spectra for each protein conformation:

- Use the Frenkel exciton Hamiltonian within the amide I spectral window (1,575 to 1,725 cm⁻¹)

- Apply vibrational spectroscopic maps parameterized against experimental findings

- Calculate corresponding Cα distance maps as ground truth for ML training

- Convert 2DIR signals into standardized 3 × 224 × 224 RGB images for model input

4.3.2 Model Training and Validation

- Implement DeepLabV3 architecture for image segmentation to distance map prediction

- Configure model with:

- Feature extraction layers with atrous convolutions for multiscale context

- Upsampling path with skip connections to restore spatial dimensions

- MaskLoss function to handle variable protein sizes via padding

- Train model using Adam optimizer with batch normalization for stabilization

- Validate using k-fold cross-validation with metrics including:

- Mean Absolute Error (MAE) for distance maps (target: ~2.20 Å)

- Long-range precision (Top-L/5, Top-L/2, Top-L)

- Cα RMSD for final 3D structures (target: ~2.54 Å)

4.3.3 Prediction of Dynamic Structures

- For experimental applications, collect 2DIR spectra of the protein under study

- Preprocess experimental spectra to match training data format

- Apply trained model to predict Cα distance maps from input spectra

- Reconstruct 3D backbone structures using gradient-based folding algorithm

- Analyze folding trajectories by applying the protocol to time-resolved 2DIR data

Signaling Pathway Dynamics: Allosteric Regulation

Proteins often employ allosteric mechanisms to regulate their function, where a perturbation at one site (e.g., ligand binding or mutation) dynamically influences a distal functional site. The comparative perturbed-ensembles approach has been instrumental in elucidating these mechanisms, as demonstrated in studies of cyclophilin A and other systems [2]. Diagram 2 illustrates a generalized allosteric signaling pathway in a protein, highlighting the dynamic propagation of structural changes.

Diagram 2: Dynamic Allosteric Signaling Pathways in Proteins

Successful implementation of protein dynamics studies requires specific computational and experimental resources. The table below details key research reagent solutions for the featured methodologies.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Protein Dynamics Analysis

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function | Key Features | Access Information |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dynameomics Database [3] | Data Resource | Repository of native state and unfolding simulation data | Contains ~200 μs of simulation data for >1000 proteins representing majority of globular folds | Publicly accessible at www.dynameomics.org |

| Comparative Perturbed-Ensembles Analysis [2] | Analytical Approach | Compare MD ensembles under different conditions | Identifies function-related dynamics through systematic comparison of perturbation states | Protocol detailed in Application Note Section 4.1 |

| BioEmu [4] | AI Software | Generate protein equilibrium ensembles | 4-5 orders of magnitude speedup vs MD; ~1 kcal/mol accuracy on single GPU | Implementation details in Lewis et al., Science 2025 |

| 2DIR-ML Protocol [5] | Analytical Protocol | Predict 3D structures from 2D IR spectra | Establishes "spectrum-structure" relationship; captures μs-ms dynamics | DeepLabV3-based model as described in PNAS 2025 |

| High-Sensitivity Stopped-Flow EPR [1] | Instrumentation | Monitor millisecond conformational kinetics | Custom dielectric resonator; minimized sample waste; 10-100 μg protein requirement | Technical specifications in Protein Science article |

| ilmm (in lucem molecular mechanics) [3] | MD Software | Perform molecular dynamics simulations | Fully flexible force field parameters; F3C water model | Development version used in Dynameomics project |

The integration of comparative perturbed-ensembles analysis with emerging AI technologies and advanced experimental methods represents a paradigm shift in protein science. By moving beyond static snapshots to embrace the intrinsically dynamic nature of proteins, researchers can uncover deeper insights into allosteric mechanisms, conformational landscapes, and functional dynamics. These approaches are already accelerating drug discovery by revealing cryptic pockets and enabling genome-scale dynamics predictions. As these methodologies continue to evolve and integrate, they promise to transform our understanding of protein function and open new avenues for therapeutic intervention.

The classical sequence-structure-function paradigm, which dominated twentieth-century molecular biology, tacitly stipulated that a single, well-defined three-dimensional structure governs a protein's function [6]. While foundational, this view is insufficient for describing the mechanisms that sustain cell life. Modern molecular biology now recognizes that function requires proteins to exist in more than a single structure, to switch between these structures, and for these structures to be incompletely organized [6]. This recognition has necessitated an updated sequence-conformational ensemble-function paradigm, with the powerful energy landscape concept as its foundation [6].

This framework embraces the reality that proteins are dynamic systems, constantly interconverting between conformational states with varying energies, where the relative stability of a conformation dictates its population within the ensemble [6]. The changes in the populations of these states—driven by interactions with ligands, membranes, other proteins, or through mutations—are fundamental to biological activity and cellular regulation [6]. Understanding these core principles is essential for comparative perturbed-ensembles analysis, a research approach that systematically compares these dynamic ensembles under different conditions to decipher functional mechanisms and dysfunction.

Core Principles and Definitions

The Conformational Ensemble

A protein does not possess a single rigid structure but exists as a collection of interconverting conformations, known as a conformational ensemble [6]. The powerful energy landscape idea, imported from physics and chemistry, forms the foundation for this modern understanding [6]. The ensemble includes the ground state (often the lowest energy, most populated conformation) as well as multiple higher-energy, less populated states. The relative propensities of these states, rather than a single rigid structure, are the true hallmark of cell life [6].

The Energy Landscape

The energy landscape is a multidimensional surface that maps all possible conformations of a protein and their associated energies [6] [7]. It describes the choreography of protein folding and dynamics.

- Energy Minima (Wells): Represent metastable conformational states. The depth of a minimum corresponds to the thermodynamic stability of that state [7].

- Energy Barriers (Peaks): Separate different conformational states. The height of a barrier dictates the kinetic stability—how readily the protein can transition from one state to another [7].

- Basin of Attraction: The region of the landscape surrounding a minimum; a protein within this basin will relax to that stable state.

The sequence of a functional protein is evolutionarily selected to create a "rough" energy landscape with multiple minima, which correlates with frustration in folding. This roughness is not a flaw but a functional necessity, enabling conformational malleability for binding-induced folding and allosteric regulation [7].

Functional States and Population Shifts

Functional properties like activation, inhibition, and allosteric regulation are governed by shifts in the populations of states within the conformational ensemble [6]. Under physiological conditions, proteins often predominantly populate their inactive conformations, with the active state representing only a minor population [6]. Function is triggered when effectors, the membrane, or oncogenic mutations stabilize the active state, increasing its population and driving a bistable switch [6]. The number of molecules in the active state ultimately determines protein function [6]. Allostery, the process by which binding at one site influences activity at a distant site, is a hallmark of this population-based regulation [6].

Quantitative Characterization of Ensembles and Landscapes

Experimental and computational methods are used to quantify the features of energy landscapes and the properties of conformational ensembles. The table below summarizes key parameters and the techniques used to measure them.

Table 1: Quantitative Parameters for Characterizing Conformational Ensembles and Energy Landscapes

| Parameter | Description | Experimental/Computational Methods |

|---|---|---|

| State Populations | The relative proportion of a specific conformation within the ensemble. | Markov Models from single-molecule data [8], NMR, Time-resolved cryo-EM [9]. |

| Transition Rates | The kinetic rate constants for interconversion between two conformational states. | Single-molecule techniques (e.g., NOTs) analyzed with Kramers' theory [8], MD simulations [10]. |

| Free Energy (ΔG) | The relative stability difference between two conformational states. | Inferred from state populations in single-molecule experiments (ΔG = -kT ln(PA/PB)) [8]. |

| Activation Energy (Ea) | The height of the energy barrier separating two states, determining transition kinetics. | Derived from temperature-dependent transition rates using Arrhenius or Kramers' theory [8]. |

| Entropy Change (ΔS) | The change in conformational disorder during a state transition. | Calculated from temperature-dependent free energy measurements (ΔG = ΔH - TΔS) [8]. |

| Molecular Polarizability | A measure of how a protein's electron cloud distorts in an electric field, reporting on structural changes. | Calculated from atomistic models and correlated with transmission signals in nanoaperture optical tweezers [8]. |

The following workflow illustrates the general process for mapping a protein's energy landscape from experimental data, as demonstrated in single-molecule studies:

Experimental Protocols for Ensemble Analysis

Protocol: Mapping Energy Landscapes with Nanoaperture Optical Tweezers (NOTs)

This protocol details the procedure for using NOTs to resolve the energy landscape of a single, unmodified protein, as demonstrated for Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) [8].

I. Principle NOTs trap a single protein without the need for fluorescent labels or tethers. Conformational changes alter the protein's polarizability, which is detected as changes in the transmission intensity of the laser beam through the nanoaperture. This allows for direct, label-free observation of state transitions and the calculation of the underlying energy landscape [8].

II. Materials and Reagents

- Protein of Interest: Purified, e.g., Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA).

- Buffers: Appropriate physiological buffer at neutral pH for initial measurements.

- Nanoaperture Substrate: A chip fabricated with double nanoholes (DNH).

- Nanoaperture Optical Tweezer Setup: Consisting of:

- Laser source (e.g., 980 nm).

- Microscope objective for trapping and signal collection.

- Avalanche Photodiode (APD) for high-sensitivity transmission detection.

- Temperature control system (often via laser power modulation with pre-calibrated local heating).

III. Procedure

- Sample Preparation: Dilute the protein to a low concentration (pM-nM) in the desired buffer to ensure single-molecule trapping events.

- System Calibration:

- Calibrate the system using polystyrene nanoparticles of known size to establish a baseline signal and confirm the absence of discrete state transitions.

- Correlate specific transmission signal levels with known protein conformations, if available (e.g., for BSA, the N-state at neutral pH and F-state at low pH).

- Data Acquisition:

- Flow the protein solution over the DNH chip.

- Initiate trapping with the laser and record the transmission signal at a high sampling rate (e.g., 100 kHz) for an extended period.

- Systematically vary the local temperature by adjusting the laser power to probe temperature-dependent dynamics.

- Data Analysis:

- State Identification: Identify discrete conformational states from the step-like changes in the transmission time-series data.

- Point Spread Function (PSF) Deconvolution: Account for signal broadening due to translational/rotational motion and noise by deconvolving a predetermined PSF from the raw data.

- Probability Density Function (PDF): Generate a binned histogram of the deconvolved transmission signal to obtain the PDF.

- Energy Landscape Calculation: Calculate the free energy landscape using the relationship ( G = -k_B T \ln(P(V)) ), where ( P(V) ) is the PDF and ( V ) is the signal coordinate.

- Kinetic Modeling: Model the state transition dynamics using a Markov model and fit the transition rates with Kramers' theory to extract thermodynamic parameters (e.g., activation energy, entropy changes).

Protocol: The Relaxed Complex Scheme for Drug Discovery

This protocol outlines the Relaxed Complex Method (RCM), a computational strategy that integrates protein dynamics from Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations into structure-based drug discovery [11].

I. Principle The RCM addresses the limitation of traditional docking, which often uses a single, static protein structure. It recognizes that binding involves selection from a pre-existing ensemble of conformations. By docking compound libraries into multiple representative snapshots (including cryptic pockets) from an MD trajectory, the RCM increases the probability of identifying hits that leverage protein flexibility for high-affinity binding [11].

II. Materials and Software

- Protein Structure: A high-resolution starting structure (from crystallography, cryo-EM, or AlphaFold2 prediction).

- MD Software: GROMACS, AMBER, or DESMOND [10].

- Molecular Docking Software: Any standard docking program (e.g., AutoDock Vina, Glide).

- Compound Library: A virtual library of drug-like molecules (e.g., ZINC, Enamine REAL Database) [11].

- High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster: With adequate CPU/GPU resources.

III. Procedure

- System Preparation:

- Prepare the protein structure (adding missing atoms, protonation states) and solvate it in a water box with appropriate ions.

- Molecular Dynamics Simulation:

- Perform an MD simulation of the target protein (apo or in a relevant state) for a timescale sufficient to capture functionally relevant motions (nanoseconds to microseconds).

- Ensure simulation stability by monitoring root-mean-square deviation (RMSD).

- Trajectory Clustering and Snapshot Selection:

- Cluster the MD trajectory based on structural similarity (e.g., using RMSD on the binding site residues).

- Select a set of representative snapshot structures from the major clusters, ensuring conformational diversity.

- Molecular Docking:

- Prepare the selected protein snapshots and the ligand library for docking.

- Perform molecular docking of the entire ligand library against each representative protein snapshot.

- Hit Identification and Analysis:

- Consolidate and rank the docking results from all snapshots based on scoring functions (e.g., binding affinity).

- Analyze top-ranking hits for consistent binding modes across multiple snapshots or for specific stabilization of a particular functional conformation (e.g., DFG-in vs. DFG-out in kinases).

The following diagram illustrates the logical flow of the RCM and its key advantage over static docking:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Solutions

The following table details essential materials, software, and reagents used in the experimental and computational protocols featured in this note.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Conformational Ensemble Studies

| Item Name | Function/Application | Example Specifications/Products |

|---|---|---|

| Nanoaperture Substrate | Creates a highly confined optical trap to immobilize a single protein for label-free detection of conformational changes. | Double Nanohole (DNH) fabricated in a gold film [8]. |

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) | A canonical model protein for method development and validation in single-molecule biophysics studies. | 66 kDa, water-soluble monomer; commercial purity >98% [8]. |

| MD Force Fields | Empirical potential functions defining interatomic interactions; critical for the accuracy of MD simulations. | CHARMM, AMBER, OPLS-AA [10]. |

| MD Simulation Software | Software suites to perform and analyze all-atom MD simulations of biomolecules. | GROMACS, AMBER, DESMOND [10]. |

| Ultra-Large Virtual Libraries | Source of billions of synthesizable compounds for virtual screening against dynamic targets. | Enamine REAL Database, Synthetically Accessible Virtual Inventory (SAVI) [11]. |

| AlphaFold2 | AI tool for highly accurate protein structure prediction from sequence; provides models for targets without experimental structures. | AlphaFold Protein Structure Database [11] [12]. |

| Generative AI Models for SBDD | De novo design of drug-like molecules considering protein flexibility and conformational changes. | DynamicFlow, other deep generative models [13]. |

| Time-Resolved Cryo-EM | Captures high-resolution snapshots of biomolecular machines in action, visualizing rare intermediate states. | Advanced cryo-electron microscopes with rapid plunge-freezing or microfluidics [9]. |

Defining Comparative Perturbed-Ensembles Analysis and its Core Hypothesis

Comparative Perturbed-Ensembles Analysis (CPEA) is a computational structural biology framework for quantifying changes in protein energy landscapes induced by perturbations such as ligand binding, mutations, or post-translational modifications. The methodology operates on the fundamental principle that proteins exist as ensembles of interconverting conformations, and that functional regulation often occurs through population shifts within these ensembles rather than through single, static structural changes [14].

The core hypothesis of CPEA posits that a precise comparison of conformational ensembles—between a reference state (e.g., apo protein) and a perturbed state (e.g., holo, phosphorylated, or mutated protein)—can reveal functionally relevant changes in structure and dynamics that are invisible to static structural comparisons. This hypothesis is formalized through its connection to thermodynamics; the measure used to compare ensembles, the Kullback-Leibler Divergence, is fundamentally a measure of the free energy difference between the two equilibrium ensembles [14]. This provides CPEA with a strong thermodynamic foundation that distinguishes it from simple geometric comparisons.

Key Applications in Protein Research

CPEA is particularly powerful for investigating complex biological phenomena where changes in dynamics are as critical as changes in structure.

- Allosteric Regulation: CPEA can identify changes in conformational distributions and dynamics at sites distant from the location of a perturbation, such as a ligand-binding event or a point mutation [14]. This allows for an unbiased discovery of allosteric networks.

- Post-Translational Modification (PTM) Effects: Systematically assessing the structural consequences of phosphorylation, as demonstrated in a global analysis of phosphorylated protein structures, which revealed that phosphorylation tends to induce small, stabilizing conformational changes and modulate protein dynamics [15].

- Drug Binding and Resistance: Understanding how mutations, particularly those conferring drug resistance, modulate ligand binding by altering the protein's energy landscape and conformational dynamics [14].

- Functional Site Identification: CPEA can help identify key functional residues by pinpointing regions where artificial perturbations cause large changes in the conformational ensemble, as these sites often co-localize with functional epitopes [14].

Quantitative Data from Perturbed-Ensemble Studies

Table 1: Quantitative Findings from a Global Analysis of Phosphorylation-Induced Structural Changes [15]

| Analysis Metric | Finding | Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Global Backbone RMSD | Median change: 1.14 ± 3.13 Å; Only 28.14% of phosphosites showed changes ≥ 2 Å. | Phosphorylation typically induces subtle conformational changes rather than large rearrangements. |

| Structural Uniformity | Median RMSD among phosphorylated structures is smaller than among non-phosphorylated counterparts. | Phosphorylation often stabilizes a particular backbone conformation, reducing structural heterogeneity. |

| Protein Kinase Domains | Median phosphorylation-induced RMSD: 1.51 Å (vs. 0.73 Å for rest of dataset). | Kinases undergo larger conformational changes upon phosphorylation, consistent with their regulatory mechanisms. |

Table 2: Key Metrics for Comparing Conformational Ensembles Using the Kullback-Leibler Divergence (KLD) [14]

| Metric/Parameter | Description | Role in CPEA |

|---|---|---|

| First-Order KLD Terms | KLD calculated for individual torsion angles (φ, ψ, χ). | Captures local population shifts and changes in flexibility at the single-residue level. |

| Second/Higher-Order KLD Terms | KLD calculated for pairs (or more) of correlated degrees of freedom. | Identifies coordinated changes and allosteric coupling between residues. |

| Mutual Divergence | Analogous to mutual information, but uses relative entropy. | Quantifies the co-dependence of conformational changes between two residues upon perturbation. |

Experimental and Computational Protocols

Protocol 1: CPEA Using Molecular Dynamics Simulations and Kullback-Leibler Divergence

This protocol is adapted from the methodology implemented in the MutInf software package [14].

1. Ensemble Generation:

- System Preparation: Create atomic-level structures for both the reference (e.g., apo protein) and perturbed (e.g., ligand-bound, mutated) systems.

- Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulation: Perform multiple, independent MD simulations for each state to generate conformational ensembles. Ensure simulations are sufficiently long to achieve adequate sampling of relevant states. Save molecular snapshots at regular intervals (e.g., every 100 ps) for subsequent analysis.

2. Torsion Angle Space Transformation:

- Coordinate Extraction: For each saved snapshot, extract the backbone (φ, ψ) and side-chain (χ₁, χ₂, ...) torsion angles for all residues. The use of internal torsion coordinates avoids frame-fitting issues inherent in Cartesian coordinate analysis [14].

- Probability Density Estimation: Construct discrete probability distributions for each torsion angle in both the reference and perturbed ensembles. This is typically done by histogramming the torsion angle values over the entire simulation trajectory.

3. Kullback-Leibler Divergence Calculation:

- First-Order (Local) Analysis: Calculate the KLD for each individual torsion angle using the formula:

KLD = Σ [ρ(x) * ln(ρ(x) / ρ*(x))]whereρ(x)is the probability distribution of the perturbed ensemble andρ*(x)is the distribution of the reference ensemble [14]. - Statistical Filtering: Use bootstrap resampling to estimate the statistical significance of the calculated KLD values. Filter out results that are not statistically significant to ensure a low-background, high-signal analysis [14].

- Higher-Order (Correlated) Analysis (Optional): Calculate second-order KLD terms for pairs of torsion angles (e.g., within a residue or between interacting residues) to capture correlated motions using the Generalized Kirkwood Superposition Approximation [14].

4. Visualization and Interpretation:

- Residue-Level Mapping: Map the significant first-order KLD values for all torsions of a residue onto the protein structure, often creating a visualization where color intensity on the structure corresponds to the magnitude of the ensemble change.

- Identification of Allosteric Sites: Residues displaying high KLD values distal to the perturbation site are candidate allosteric residues.

Protocol 2: CPEA Using Experimental Structural Ensembles with EnsembleFlex

This protocol utilizes the EnsembleFlex computational suite for analyzing experimentally derived structural ensembles from the PDB (e.g., from X-ray crystallography, NMR, or cryo-EM) [16].

1. Data Curation and Superposition:

- Ensemble Collection: Compile a set of PDB structures for the protein in its reference and perturbed states. This may include multiple crystal forms, NMR models, or structures with and without a post-translational modification like phosphorylation [15].

- Structural Alignment: Superimpose all structures (both reference and perturbed) onto a common reference frame, typically using a conserved, rigid core of the protein to avoid bias [16].

2. Flexibility and Variability Analysis:

- Backbone Flexibility: Calculate per-residue Root-Mean-Square Fluctuation (RMSF) for the backbone atoms (Cα) within each ensemble to quantify flexibility [16].

- Side-Chain Conformational Heterogeneity: Analyze the rotameric states and spatial occupancy of side chains to identify residues with significant population shifts between ensembles.

- Principal Component Analysis (PCA): Perform PCA on the combined set of superposed structures. This reduces the dimensionality of the conformational data to identify the dominant collective motions that distinguish the reference and perturbed ensembles [16].

3. Binding-Site and Conservation Analysis:

- Ligand-Site Variability Mapping: If applicable, automatically map the variability of binding-site geometries across the ensemble [16].

- Conserved Water Identification: Identify structurally conserved water molecules within the ensembles, as these can be critical for function and their displacement can signal important ensemble shifts [16].

4. Comparative Quantification:

- State Identification: Use clustering algorithms on the principal components to identify distinct conformational states and quantify their populations in the reference versus perturbed ensembles [16].

- Statistical Testing: Perform statistical tests (e.g., Mann-Whitney U test) to rigorously assess whether observed differences in RMSF, state populations, or other metrics are significant [15].

Signaling Pathway and Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and data flow for a typical Comparative Perturbed-Ensembles Analysis, integrating both simulation and experimental approaches.

CPEA Core Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Software and Data Resources for CPEA

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function in CPEA | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| MutInf | Software Package | Calculates the Kullback-Leibler Divergence between conformational ensembles from MD simulations to identify population shifts. | [14] |

| EnsembleFlex | Computational Suite | Performs integrated analysis of experimental structural ensembles (X-ray, NMR, cryo-EM) for flexibility, clustering, and binding-site variability. | [16] |

| CPDB (Protein Data Bank) | Database | Primary repository for experimentally solved protein structures, used as a source for building reference and perturbed ensembles. | [15] |

| GROMACS/AMBER | MD Simulation Engine | Generates conformational ensembles through atomic-level molecular dynamics simulations. | [14] |

| Climateprediction.net (CPDN) | Computing Platform | A distributed computing project that runs large perturbed-parameter ensembles; a conceptual model for large-scale ensemble simulation in biology. | [17] |

Proteins are inherently dynamic molecules that exist as an ensemble of interconverting conformations rather than single, static structures. This conformational heterogeneity is a fundamental determinant of protein function, enabling mechanisms such as allostery, catalysis, and signal transduction. The dynamic nature of proteins arises from two primary sources: intrinsic dynamics governed by the protein's amino acid sequence and energy landscape, and external perturbations induced by environmental factors, ligand binding, or cellular interactions. Understanding these conformational ensembles is crucial for advancing fundamental biology and accelerating drug discovery efforts, particularly for targeting proteins with significant structural flexibility, including many challenging drug targets.

Recent breakthroughs in artificial intelligence, particularly AlphaFold, have revolutionized static structure prediction but face limitations in capturing the full spectrum of protein dynamics [18] [19]. This application note provides a comprehensive overview of contemporary methodologies for studying conformational heterogeneity, presenting quantitative comparisons, detailed experimental protocols, and essential computational tools for researchers investigating protein dynamics.

Quantitative Comparison of Methodologies

The study of conformational ensembles employs diverse computational and experimental approaches, each with distinct strengths, limitations, and applicable resolution ranges. The table below summarizes key quantitative metrics for major methodologies discussed in this application note.

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Methodologies for Studying Conformational Heterogeneity

| Method | Spatial Resolution | Temporal Resolution | Key Measurable Parameters | Throughput | Information Gained |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FiveFold [18] | Atomic (Cα) | Thermodynamic states | PFSC strings, conformational clusters | High | Complete folding space for 5-residue fragments, massive conformational ensembles |

| DIRseq [20] | Single residue | Binding equilibrium | Drug-interacting residue propensity | Very High | Sequence-based prediction of drug-binding residues in IDPs |

| MD-NMR Integration [21] | Atomic | ps-ms | R1, R2, NOE, ηxy rates, order parameters (S²) | Low | Atomistic dynamics, time-resolved 4D conformational ensembles |

| AI-2DIR Spectroscopy [5] | Atomic (Cα backbone) | μs-ms | Cα distance maps, RMSD (2.54 Å average) | Medium | Dynamic folding trajectories, static structures of uncharacterized proteins |

| ProFlex (NMA) [22] | Cα coarse-grained | Harmonic motions | RMSF profiles, flexibility alphabets | Very High | Global flexibility trends, relative dynamics across structural database |

| EnsembleFlex [16] | Backbone & side-chain | Structural snapshots | RMSD/RMSF, PCA/UMAP clusters, binding site variability | High | Conformational heterogeneity from experimental PDB ensembles |

Research Reagent Solutions Toolkit

Implementing conformational ensemble studies requires specialized computational tools and resources. The following table catalogizes essential research reagents and their applications in perturbed-ensemble analysis.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Ensemble Analysis

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| FiveFold [18] | Algorithm & Web Server | Generates massive conformational ensembles using PFSC/PFVM | Web server |

| DIRseq [20] | Prediction Server | Identifies drug-interacting residues in disordered proteins from sequence | https://zhougroup-uic.github.io/DIRseq/ |

| EnsembleFlex [16] | Analysis Suite | Quantifies conformational heterogeneity from experimental PDB ensembles | Open access |

| ProFlex Toolkit [22] | Flexibility Analysis | Encodes protein flexibility into alphabetic representations for large-scale analysis | Available with publication |

| SwissDock 2024 [20] | Docking Server | Small-molecule docking with Attracting Cavities and AutoDock Vina | Web server |

| PDB-PFSC Database [18] | Structural Database | Repository of protein structures converted to PFSC strings | Database |

| 5AAPFSC Database [18] | Conformational Database | All possible folding patterns for five amino acid fragments | Database |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: FiveFold Conformational Ensemble Prediction

The FiveFold approach addresses limitations of single-state predictions by generating comprehensive conformational ensembles based on local folding principles [18].

Materials:

- Protein amino acid sequence

- FiveFold software suite or web server

- PDB-PFSC database

- 5AAPFSC database (3.2 million five-amino-acid permutations)

Procedure:

- PFSC Assignment: Convert the input protein sequence into Protein Folding Shape Code (PFSC) strings using the 27-letter alphabet representing all possible five-residue folding patterns.

- PFVM Construction: Assemble the Protein Folding Variation Matrix (PFVM) to map local folding variations along the entire sequence, revealing intrinsic fluctuation patterns.

- Conformational Sampling: Generate a massive number of possible PFSC strings through optimized combinations of local folding patterns from the PFVM.

- Structure Assembly: Screen the PDB-PFSC database using generated PFSC strings to identify and retrieve compatible structural fragments.

- Ensemble Construction: Assemble complete 3D structures from compatible fragments, generating the final conformational ensemble for analysis.

Applications: Intrinsically disordered proteins, mutational analysis, folding pathway studies, and alternative conformation prediction.

Protocol: Integrative MD-NMR Ensemble Validation

This protocol combines molecular dynamics simulations with NMR relaxation data to generate and validate biologically relevant conformational ensembles [21].

Materials:

- AlphaFold-predicted protein structure or experimental structure

- High-performance computing resources for MD simulations

- NMR spectrometer (≥600 MHz)

- Isotopically labeled protein (¹⁵N, ¹³C)

- NMR data processing software (NMRPipe, CCPN)

- MD simulation software (AMBER, GROMACS, CHARMM)

- Back-calculation and analysis scripts (ABSURDer, MaxEnt)

Procedure:

- Initial Structure Preparation: Obtain starting structure from AlphaFold prediction or experimental determination. Perform energy minimization and solvation.

- MD Simulation: Conduct extensive free MD simulations (≥1 μs) using modern force fields (AMBER, CHARMM). Maintain physiological conditions (temperature, pH, ionic strength).

- NMR Data Acquisition: Collect ¹⁵N relaxation data (R₁, R₂, heteronuclear NOE) and cross-correlated relaxation (ηxy) rates using optimized pulse sequences.

- Trajectory Segmentation: Divide MD trajectory into segments based on RMSD plateaus, identifying structurally stable regions.

- Parameter Back-Calculation: Compute theoretical NMR relaxation parameters (R₁, R₂, NOE, ηxy) from each MD trajectory segment.

- Ensemble Selection: Identify trajectory segments where back-calculated parameters match experimental NMR data within acceptable error margins (χ² minimization).

- Validation: Analyze selected ensembles for functional relevance, particularly in flexible regions with biological significance.

Applications: Validation of dynamic ensembles, identification of functional conformational states, characterization of allosteric mechanisms.

Protocol: AI-Enhanced 2DIR Spectroscopy for Dynamic Structure Prediction

This innovative protocol combines two-dimensional infrared spectroscopy with machine learning to predict dynamic protein structures in real-time [5].

Materials:

- Protein sample (natural or isotopic labeling)

- 2DIR spectrometer with femtosecond laser system

- Curated protein structure database (RCSB PDB, SWISS-PROT)

- High-performance computing resources for spectral simulation

- DeepLabV3-based ML architecture with customized training

- Gradient-based folding algorithm for 3D reconstruction

Procedure:

- Database Curation: Collect diverse protein structures (up to 150 residues) from RCSB PDB and SWISS-PROT. For larger proteins, employ transfer learning approaches.

- Theoretical 2DIR Simulation: Generate 2DIR spectra for each protein conformation using Frenkel exciton Hamiltonian within the amide I spectral window (1575-1725 cm⁻¹).

- ML Model Training: Train DeepLabV3 architecture to predict Cα distance maps from 2DIR spectral descriptors. Use Maskloss function for variable-sized proteins.

- Experimental Data Acquisition: Collect experimental 2DIR spectra of target protein under physiological conditions.

- Structure Prediction: Process experimental 2DIR spectra through trained ML model to generate Cα distance maps.

- 3D Reconstruction: Apply gradient-based folding algorithm to convert distance maps into 3D protein backbone structures.

- Dynamic Tracking: Monitor structural evolution during folding processes (μs-ms timescales) by analyzing time-resolved 2DIR spectra.

Applications: Real-time monitoring of folding intermediates, characterization of previously unstudied proteins, analysis of rapid conformational changes.

Applications in Drug Discovery and Protein Engineering

Targeting Intrinsically Disordered Proteins with DIRseq

Intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs) represent challenging yet valuable drug targets due to their conformational heterogeneity. DIRseq provides a computational framework for predicting drug-interacting residues in IDPs directly from sequence information, bypassing the need for structural data [20].

Implementation:

- Input the IDP amino acid sequence into the DIRseq web server

- The algorithm calculates contribution factors from all residues, with amplitude determined by amino acid type and attenuation with sequence distance

- Output identifies high-probability drug-interacting residues

- Validate predictions against known experimental data (e.g., p53 interactions at L22WK24 and Q52WFT55)

Advantages: Rapid screening of potential binding sites, guidance for NMR and MD studies, virtual screening against IDP targets.

Engineering Conformational Landscapes for Improved Function

Protein engineering campaigns increasingly recognize the importance of conformational dynamics in optimizing enzyme properties. Beneficial substitutions often influence global conformational ensembles rather than merely altering local active site geometry [23] [24].

Strategy:

- Conformational Analysis: Use EnsembleFlex or ProFlex to analyze conformational heterogeneity in parent enzyme

- Substitution Mapping: Introduce beneficial substitutions identified through directed evolution or rational design

- Ensemble Monitoring: Track changes to conformational landscapes using MD-NMR or AI-2DIR approaches

- Network Analysis: Identify allosteric networks and distal effects using amino acid interaction mapping

- Functional Validation: Correlate conformational shifts with improved catalytic properties, stability, or selectivity

Applications: Enzyme engineering for industrial biocatalysis, antibody optimization, and therapeutic protein design.

The integrative analysis of conformational heterogeneity through multiple complementary methodologies provides unprecedented insights into protein function and dynamics. While individual techniques offer specific advantages, the most powerful approaches combine computational predictions with experimental validation, leveraging the strengths of each method. The protocols and tools outlined in this application note empower researchers to move beyond static structural representations toward dynamic ensemble-based understanding, with significant implications for basic biology, drug discovery, and protein engineering. As these methodologies continue to evolve, particularly with advances in AI integration and experimental techniques, the capacity to correlate conformational heterogeneity with biological function will fundamentally transform structural biology and therapeutic development.

The revolutionary development of AlphaFold has provided an unprecedented view of the protein universe by predicting hundreds of millions of static structures with remarkable accuracy [25] [26]. This achievement, recognized by the 2024 Nobel Prize in Chemistry, has fundamentally transformed structural biology by making high-quality protein structure predictions widely accessible [25]. However, this static view represents only the first step toward understanding biological function. Proteins are dynamic entities that sample multiple conformational states, and their functional mechanisms emerge from these dynamic transitions [27]. The post-AlphaFold era is consequently focused on bridging the gap between static structural predictions and the functional dynamics that underlie biological activity, with comparative perturbed-ensembles analysis emerging as a key methodology for quantifying these dynamic properties.

The core challenge lies in the fact that biological function is encoded not in a single static structure but in the energy landscape and the conformational fluctuations within it [28] [27]. As nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) studies have consistently demonstrated, proteins exist as ensembles of interconverting structures, with motions occurring across timescales from femtoseconds to seconds [27]. Understanding how proteins function—how they catalyze reactions, interact with partners, and respond to environmental changes—requires characterizing these ensembles and the transitions between them. This application note outlines integrated computational and experimental frameworks for moving beyond static predictions to capture the dynamic determinants of protein function, with particular emphasis on protocols suitable for drug discovery applications.

Methodological Framework: Integrating Computational and Experimental Approaches

AI-Driven Molecular Dynamics at Quantum Accuracy

The recent introduction of AI2BMD represents a transformative advancement for simulating protein dynamics with quantum-level accuracy while maintaining computational efficiency [28]. This AI-powered molecular dynamics system achieves a critical balance—delivering higher accuracy than classical force fields while being substantially faster than density functional theory (DFT) and other quantum mechanical methods [28]. The system employs a novel protein fragmentation strategy that decomposes proteins into 21 universal building blocks, enabling training on a dataset of over 20 million protein fragments and ensuring broad transferability across diverse protein families [28].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Molecular Dynamics Simulation Methods

| Method | Accuracy Level | Computational Speed | System Size Limit | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AI2BMD | Quantum (ab initio) | Hours to days | ~10,000 atoms | Drug binding, enzyme catalysis, allosteric regulation |

| Classical MD | Newtonian force fields | Minutes to hours | >100,000 atoms | Large-scale conformational changes, folding |

| Density Functional Theory | Quantum (ab initio) | Weeks to months | ~100 atoms | Chemical reactions, electronic properties |

| Hybrid QM/MM | Mixed quantum/classical | Days to weeks | ~1,000 atoms | Enzymatic reactions, spectroscopic properties |

For practical implementation, AI2BMD utilizes a client-server architecture that dynamically schedules CPU and GPU resources to achieve simulation speeds of tens of milliseconds per step [28]. This performance enables microsecond-scale simulations of small to medium-sized proteins at quantum accuracy, permitting direct comparison with experimental data through the calculation of experimental observables including J-couplings, enthalpy changes, heat capacity, folding free energy, melting temperature, and pKa values [28].

Experimental Protocol 1: AI2BMD Simulation for Drug Binding Sites

- System Preparation: Obtain protein structure from AlphaFold Database or experimental source. Define binding site region of interest based on structural or evolutionary data.

- Parameter Configuration: Set simulation temperature (typically 300K), ionic concentration, and simulation duration based on biological context. Use 1 femtosecond time steps.

- Simulation Execution: Run AI2BMD for sufficient duration to observe relevant dynamics (typically 100ns-1μs for local binding site motions).

- Trajectory Analysis: Calculate root-mean-square fluctuations of binding site residues, distance correlations between key residues, and conformational clustering of binding pocket geometries.

- Binding Affinity Prediction: Use free energy perturbation methods on identified conformational states to estimate ligand binding affinities.

Perturbed-Ensembles Analysis Inspired by Meteorological Science

The concept of ensemble perturbation methods has deep roots in numerical weather prediction, where addressing uncertainty in initial conditions is essential for forecast reliability [29] [30]. These methodologies provide a powerful framework for understanding how uncertainties in protein structural models propagate through dynamics simulations to affect functional predictions. Three principal perturbation approaches have been developed in meteorology and show direct applicability to protein dynamics:

- Singular Vector Method (SV): Identifies the fastest-growing perturbations in the initial conditions, emphasizing directions in phase space with maximal error growth [30]. For proteins, this translates to identifying conformational changes with the largest impact on functional states.

- Ensemble Transform Kalman Filter (ETKF): Utilizes a transformation matrix to convert forecast perturbations into analysis perturbations that maintain orthogonality in observation space [29]. This method effectively incorporates experimental constraints into ensemble generation.

- Breeding of Growing Modes (BGM): Generates perturbations through nonlinear model integration and rescaling, effectively capturing the dominant unstable structures [29]. This approach naturally adapts to protein-specific conformational landscapes.

Table 2: Perturbation Methods for Ensemble Generation in Protein Dynamics

| Method | Mathematical Foundation | Key Advantage | Experimental Constraints | Computational Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular Vector (SV) | Linear algebra (singular value decomposition) | Identifies most influential perturbations | Limited incorporation | High (requires adjoint models) |

| Ensemble Transform Kalman Filter (ETKF) | Statistical estimation (Kalman filter) | Optimally integrates experimental data | Strong incorporation | Medium (ensemble operations) |

| Breeding Growing Modes (BGM) | Nonlinear dynamics with rescaling | Captures naturally growing modes | Moderate incorporation | Low (forward integration only) |

Experimental Protocol 2: Multi-Scale Singular Vector Perturbation for Protein Ensembles

- Initial Structure Generation: Create an ensemble of starting structures using AlphaFold 2 or 3 with varying random seeds or template usage policies.

- Singular Vector Calculation: Compute singular vectors for the molecular dynamics force field using the system's linear response properties.

- Perturbation Application: Apply perturbations along the dominant singular vectors with amplitudes consistent with estimated structural uncertainties.

- Ensemble Propagation: Run parallel molecular dynamics simulations for each perturbed initial condition.

- Analysis of Variability: Quantify the growth of perturbations and their impact on functional metrics (e.g., binding site geometries, allosteric networks).

Experimental Probes of Protein Dynamics

On the experimental side, NMR spectroscopy remains the premier technique for site-specific characterization of protein dynamics across multiple timescales [27]. Recent methodological advances have addressed key limitations of traditional approaches:

Selective CPMG/CEST Experiments: Traditional Carr-Purcell-Meiboom-Gill (CPMG) and Chemical Exchange Saturation Transfer (CEST) experiments typically require collecting a series of two-dimensional spectra, which is time-consuming and limits application to proteins with favorable spectroscopic properties [27]. The innovative replacement of INEPT transfer with Hartmann-Hahn polarization transfer enables frequency-selective excitation, converting these experiments into one-dimensional measurements that dramatically reduce acquisition time from days to hours while simultaneously improving signal-to-noise by 3-4 fold [27].

Experimental Protocol 3: Selective 1D CPMG for Functional Site Dynamics

- Sample Preparation: Prepare uniformly 15N-labeled protein sample in appropriate buffer. Protein concentration should be 0.5-1.0 mM for optimal sensitivity.

- Magnetization Transfer: Apply Hartmann-Hahn cross-polarization with the continuous wave frequency set to the specific amide nitrogen resonance of interest.

- CPMG Pulse Train: Implement the CPMG sequence with varying pulsing frequencies (νCPMG typically 50-1000 Hz) to characterize millisecond timescale dynamics.

- Relaxation Dispersion Analysis: Measure effective transverse relaxation rates (R2,eff) as a function of νCPMG and fit to appropriate chemical exchange models to extract kinetic and thermodynamic parameters for conformational exchange processes.

- Site-Specific Mapping: Repeat for all functionally relevant residues (e.g., active site residues, allosteric network residues, flexible linkers).

Integrated Workflow for Drug Discovery Applications

Targeting Dynamic Protein-Ligand Interactions

The integration of AlphaFold 3 with dynamics simulations creates powerful opportunities for structure-based drug design, particularly for challenging targets where static structures provide insufficient insight [25] [31]. AlphaFold 3 demonstrates remarkable capability in predicting protein interactions with diverse ligands, antibodies, nucleic acids, and other molecular partners [31]. When combined with perturbed-ensembles analysis, researchers can map the conformational landscape of drug targets and identify cryptic binding sites that emerge only in specific dynamic states.

Experimental Protocol 4: Dynamic Binding Site Characterization for Drug Discovery

- Initial Complex Prediction: Use AlphaFold Server or AlphaFold 3 to generate models of protein-ligand complexes [25].

- Ensemble Expansion: Apply multi-scale perturbation methods to generate structurally diverse conformations around the predicted binding mode.

- Binding Site Dynamics Simulation: Run AI2BMD simulations on selected ensemble members to characterize the flexibility and solvation of the binding site [28].

- Pharmacophore Analysis: Identify conserved interaction patterns across the dynamic ensemble that could inform ligand design.

- Free Energy Calculations: Use molecular mechanics combined with enhanced sampling to compute relative binding affinities for candidate compounds against multiple conformational states.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Protein Dynamics Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Type | Function in Dynamics Studies | Access Information |

|---|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold Protein Structure Database | Database | Provides static structural models for ensemble initialization | Free access via EMBL-EBI |

| AlphaFold Server | Prediction Server | Generates protein-ligand complex predictions | Free for non-commercial research |

| AI2BMD | Simulation Software | Enables quantum-accurate molecular dynamics | Code available for academic use |

| MoleculeOS | Protein Design Platform | Offers dynamic design capabilities and complex prediction | Commercial platform |

| Protein Unit Dataset | Training Data | Enables development of custom machine learning force fields | Available via GitHub repository |

| Selective CPMG/CEST Pulse Sequences | Experimental Protocol | Enables efficient measurement of site-specific dynamics | Published in Journal of Magnetic Resonance |

AI-Guided Protein Engineering with Dynamics Awareness

The AiCE (AI-informed Constraints for protein Engineering) framework demonstrates how inverse folding models, which predict sequences compatible with given structural scaffolds, can leverage both structural and evolutionary constraints to guide protein engineering [32]. This approach achieves remarkable efficiency, requiring only approximately 1.15 CPU hours to identify single and double mutations for large proteins like SpCas9 (>1000 amino acids) [32]. By incorporating dynamics information through comparative ensemble analysis, the engineering process can optimize not only for structural stability but also for functional dynamics.

Experimental Protocol 5: Dynamics-Aware Protein Engineering with AiCE

- Target Identification: Select protein and desired functional improvement (e.g., thermostability, catalytic efficiency, altered specificity).

- Backbone Ensemble Generation: Create an ensemble of backbone conformations using perturbed-ensembles molecular dynamics simulations.

- Sequence Optimization: Apply AiCEsingle for identifying individual mutations and AiCEmulti for identifying coordinated mutation sets across the structural ensemble [32].

- Library Design: Combine top-ranking mutations into focused libraries for experimental screening.

- Functional Validation: Express and characterize variant proteins, focusing on both structural integrity and dynamic properties relevant to function.

The integration of AlphaFold's static predictions with comparative perturbed-ensembles analysis represents a paradigm shift in structural biology and drug discovery. This unified framework enables researchers to move beyond single-structure models to embrace the inherent dynamism of biological macromolecules. The methodologies outlined in this application note—from quantum-accurate AI2BMD simulations to efficient selective NMR experiments and dynamics-aware protein engineering—provide a comprehensive toolkit for characterizing functional protein dynamics.

As these approaches continue to mature, several exciting frontiers are emerging. The development of multi-scale perturbation methods that seamlessly integrate quantum, atomic, and coarse-grained representations will enable comprehensive characterization of large biomolecular complexes [30]. Advances in AI-driven experimental design will optimize the selection of perturbations and measurements to maximize information gain while minimizing resource expenditure. Finally, the creation of universal density maps that encode the full conformational landscape of proteins will transform our ability to predict functional effects of mutations and design proteins with novel dynamical properties.

The post-AlphaFold era is not merely about refining static structural predictions but about fundamentally reimagining proteins as dynamic systems. By embracing comparative perturbed-ensembles analysis, researchers can accelerate the translation of structural information into functional understanding, ultimately enabling more effective drug design and protein engineering.

Implementing Perturbed-Ensembles Analysis: A Step-by-Step Methodology and Real-World Applications

In the context of a broader thesis on comparative perturbed-ensembles analysis, the strategic selection of perturbations is a cornerstone for deriving biologically and therapeutically relevant insights from protein dynamics research. Proteins are inherently dynamic, and their functional mechanisms, including conformational changes and allosteric regulation, are central to biological activity and therapeutic intervention [33] [34]. Perturbation-based simulation studies aim to systematically manipulate these dynamics—through mutations, ligand binding, or environmental changes—to map the conformational landscape and understand how it is altered in disease or modulated by drug molecules [35] [33]. This application note provides detailed protocols and frameworks for selecting and applying these critical perturbations, ensuring that simulation experiments are robust, reproducible, and directly informative for drug discovery.

The Perturbation Toolkit: Types and Biological Rationale

Meaningful simulation experiments begin with a considered choice of perturbation type, each designed to answer specific biological questions. The table below summarizes the core categories of perturbations used in comparative ensemble analysis.

Table 1: Categories of Perturbations for Protein Dynamics Studies

| Perturbation Category | Specific Examples | Key Biological Questions Addressed |

|---|---|---|

| Mutations | Single-point mutations (e.g., oncogenic mutations like in KRAS), deletion of functional domains, pathogenic variants (e.g., in neurodegenerative diseases) | How do mutations alter stable conformational states? Do they shift populations towards active/inactive states? How is allosteric networking disrupted? |

| Ligands | Small-molecule drugs [33], substrates, co-factors, ions [35], allosteric modulators | How does binding induce conformational changes? Can ligands selectively stabilize rare, functionally relevant states? How does binding affinity correlate with dynamical shifts? |

| Environmental Conditions | pH changes, ionic strength, temperature, oxidative stress, post-translational modifications (phosphorylation) | How do proteins sense and respond to cellular signals? What is the molecular basis for pH-dependent activity? How does phosphorylation trigger long-range conformational changes? |

Ligand-Specific Conformational Selection

A principal goal in therapeutic discovery is understanding ligand-specific conformational selection. Advanced computational methods like DynamicBind demonstrate that drugs exert their effects by binding to specific conformations of a target protein, thereby altering its conformational landscape [33]. This is a critical consideration for selecting ligands; for example, a kinase inhibitor may preferentially stabilize the DFG-out "inactive" conformation over the DFG-out "active" state. When designing simulations, it is essential to include ligands with known divergent efficacies (e.g., agonist vs. antagonist) to decipher the structural basis for their functional differences.

Probing Mutational Impact on Dynamics

Mutations, particularly those associated with diseases, can profoundly alter protein dynamics without necessarily changing the static ground-state structure. In a comparative perturbed-ensembles framework, one would run parallel simulation campaigns for the wild-type and mutant proteins. The analysis focuses on quantifying differences in the collective motions, the population of key intermediate states, and the free energy landscapes. This approach can reveal how a mutation "rewires" the internal network of interactions, leading to gain-of-function or loss-of-function phenotypes [34].

Experimental Protocols for Perturbation Simulations

This section provides a detailed, step-by-step methodology for conducting a simulation study comparing the dynamics of a protein system under different perturbed conditions.

Protocol 1: Comparative Ensemble Analysis with Multiple Perturbations

Objective: To characterize and compare the conformational dynamics of a protein system (e.g., a kinase) under three conditions: wild-type, a pathogenic mutant, and wild-type bound to a small-molecule inhibitor.

Step-by-Step Workflow:

System Setup and Initialization:

- Structure Preparation: Obtain initial coordinates from experimental sources (PDB) or prediction tools (AlphaFold). For ligand-bound simulations, prepare the ligand parameter files using tools like CGenFF or GAUSSIAN. Caution: AlphaFold-predicted structures often represent apo-like conformations and may require careful assessment for ligand docking [33].

- System Building: Solvate the protein in an explicit solvent box (e.g., TIP3P water) and add ions to neutralize the system and achieve a physiologically relevant ionic concentration (e.g., 150 mM NaCl).

Equilibration and Production Run:

- Energy Minimization: Perform steepest descent minimization to remove steric clashes.

- Equilibration: Conduct a multi-stage equilibration under NVT and NPT ensembles to stabilize the temperature and pressure of the system.

- Production MD: Run multiple independent, unbiased MD simulations (≥ 3 replicas per condition) for a duration sufficient to sample the relevant biological motions. For many functional changes, this may range from hundreds of nanoseconds to microseconds. Use a GPU-accelerated MD package for computational efficiency [34].

Trajectory Analysis:

- Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD): Assess the overall structural stability and convergence of simulations.

- Principal Component Analysis (PCA): Identify the dominant collective motions from the combined trajectory of all ensembles. Project trajectories from each condition (wild-type, mutant, ligand-bound) onto the same principal components to visualize their distinct sampling in conformational space [36].

- Distance/RMSD-based Clustering: Group similar conformations from the trajectory to identify and quantify the population of distinct metastable states.

- Analysis of Specific Coordinates: Monitor the behavior of known functional motifs (e.g., the DFG loop in kinases, ionic locks in GPCRs) to determine the state of the protein in each ensemble.

Free Energy Calculation:

- Construct potential of mean force (PMF) along the first principal component or a relevant reaction coordinate to compare the relative stability of states between the perturbed ensembles.

Diagram: Workflow for Comparative Perturbed-Ensembles Analysis

Protocol 2: Using Targeted Perturbations to Accelerate Rare Events

Objective: To generate a transition path between two known conformational states (e.g., active to inactive kinase) using a biased simulation method.

Methodology Selection: For processes that occur on timescales beyond the reach of standard MD, targeted methods are essential. The table below compares three common perturbation MD methods.

Table 2: Comparison of Perturbation Molecular Dynamics Methods

| Method | Key Principle | Perturbation Strength | Typical Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Targeted MD (TMD) | Applies a holonomic constraint to smoothly reduce the RMSD to a target structure over time [37]. | Strongly constrained | Forcing a direct transition between two defined end-states. |

| Steered MD (SMD) | Applies a harmonic restraint (like AFM) on a progress variable, which is moved at a constant rate [37]. | Moderately constrained | Mimicking force-spectroscopy experiments; inducing unfolding or large-scale conformational changes. |

| Biased MD (BMD) | Applies a one-sided potential that only acts when the system moves away from the target, offering the least restraint [37]. | Weakly constrained | Exploring low-energy pathways and identifying metastable intermediates with minimal bias. |

Workflow:

- Define End States: Clearly identify the initial and target conformational states (e.g., from two different crystal structures).

- Select Progress Variable: Choose a suitable reaction coordinate (e.g., RMSD of the protein backbone, a specific inter-atomic distance, or dihedral angle) that distinguishes the two states.

- Run Simulations: Perform multiple independent TMD/SMD/BMD simulations, systematically varying parameters like the simulation length or biasing force constant to ensure the robustness of the observed path [37].

- Path Analysis: Cluster the resulting trajectories to identify common intermediates and transition states. The pathways generated by these different methods are often similar for a given progress variable, but the choice of the progress variable itself is critical [37].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Solutions

A successful simulation study relies on a suite of software tools and resources. The following table details key solutions for different stages of the workflow.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Perturbation Ensemble Studies

| Tool Category | Example Solutions | Function in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Dynamics Engines | GROMACS, NAMD, AMBER, CHARMM [37] [34] | Core simulation software for running energy minimization, equilibration, and production MD or perturbation MD simulations. |

| Specialized Docking & Conformational Sampling | DynamicBind [33] | A deep learning method for "dynamic docking" that predicts ligand-specific protein conformations from apo structures, handling large conformational changes. |

| Visualization & Analysis | ParaView [38], VMD, PyMOL | Post-processing and visualization of large trajectory datasets, creation of publication-quality figures and movies. |

| Data Analysis & Graphing | Prism [39], Python (MDAnalysis, MDTraj) | Statistical analysis of trajectory data, generation of graphs (RMSD, RMSF, PCA plots), and creation of violin/estimation plots for ensemble comparison. |

| Contrast Checking (for Accessibility) | WebAIM Contrast Checker [40] | Ensuring that all diagrams and visualizations generated for publications and presentations meet WCAG guidelines for color contrast, aiding comprehensibility. |

Concluding Remarks on Protocol Design

The design of simulation experiments is as critical as their execution. Adherence to a well-defined simulation plan or protocol is imperative for ensuring the quality, reproducibility, and regulatory credibility of simulation studies in drug development [41]. This document has outlined specific, actionable protocols for applying key perturbations. By integrating these approaches within a comparative perturbed-ensembles analysis framework, researchers can move beyond static structures to generate a dynamic and mechanistic understanding of protein function, ultimately accelerating the development of novel therapeutics for previously undruggable targets [33].