Capturing Motion: How Molecular Dynamics Simulations Reveal Biomolecular Conformational Changes for Drug Discovery

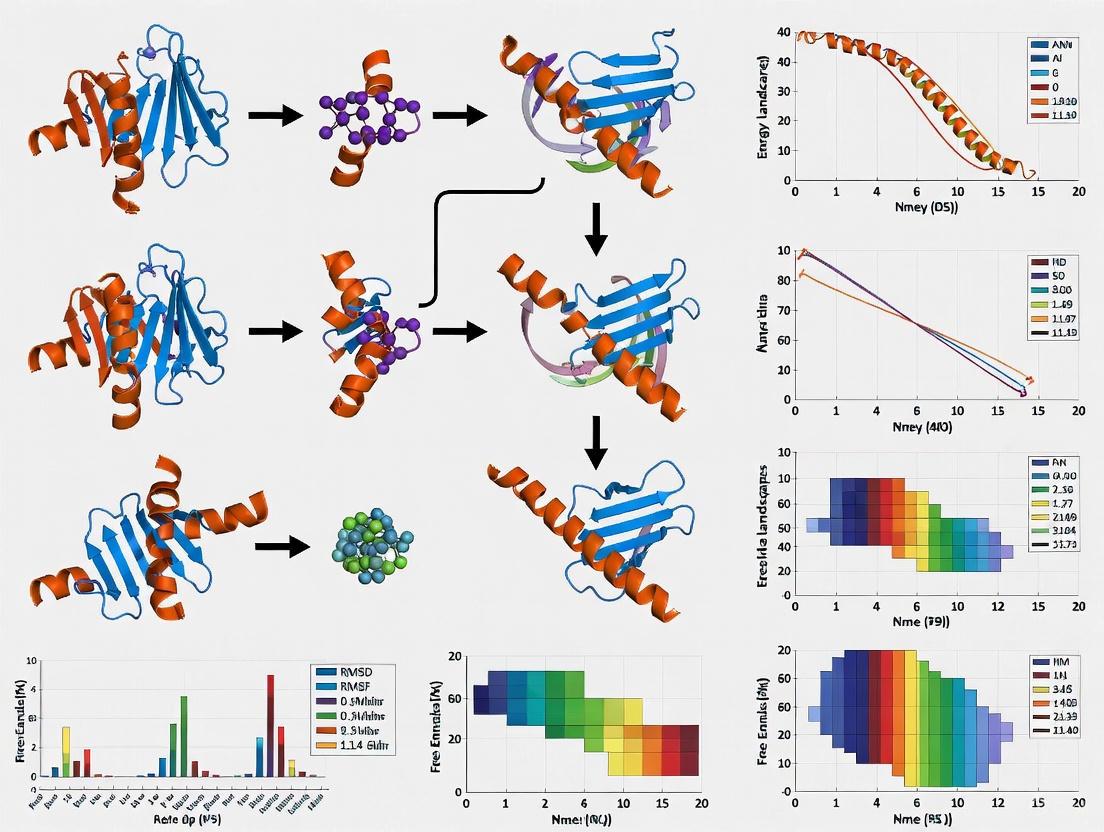

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the application of Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations in studying biomolecular conformational changes, a critical process in understanding biological function and enabling structure-based drug...

Capturing Motion: How Molecular Dynamics Simulations Reveal Biomolecular Conformational Changes for Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the application of Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations in studying biomolecular conformational changes, a critical process in understanding biological function and enabling structure-based drug design. It covers the foundational principles of MD, detailing how these simulations act as 'virtual molecular microscopes' to capture atomic-level motions. The article explores advanced methodologies and key applications, including the detection of cryptic binding sites and the use of Markov state models to extend timescales. It also addresses common challenges such as sampling limitations and force field accuracy, presenting solutions like enhanced sampling and AI integration. Finally, it discusses the critical process of validating simulations against experimental data and compares the performance of different MD software and force fields. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes how MD simulations complement experimental techniques to drive discovery in biochemistry and pharmacology.

The Atomic Movie: Foundational Principles of Biomolecular Dynamics

The Paradigm Shift: From Single Structures to Dynamic Ensembles

Proteins are not static entities; their functions are fundamentally governed by dynamic transitions between multiple conformational states [1]. For decades, static three-dimensional structures, often derived from X-ray crystallography, provided the primary snapshot of protein architecture. However, this static view fails to capture the essential molecular motions that underlie biological function, including catalysis, allosteric regulation, and signal transduction [1]. The emerging paradigm recognizes proteins as conformational ensembles—collections of interconverting structures that represent the full scope of a protein's functional repertoire under given conditions [1].

This shift is crucial for understanding the mechanistic basis of protein function and regulation. Many pathological conditions, including Alzheimer's disease and Parkinson's disease, stem from protein misfolding or abnormal dynamic conformations [1]. Consequently, systematically elucidating transitions between conformational states is essential for designing conformation-specific drugs and treating a wide range of diseases [1]. The limitations of single-structure approaches are particularly pronounced for intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs), which comprise approximately 30–40% of the human proteome and lack a stable tertiary structure altogether [2]. The dynamic ensemble view thus represents not merely a technical refinement but a fundamental transformation in how we conceptualize and investigate protein structure-function relationships.

Methodological Approaches for Studying Conformational Dynamics

Experimental and Computational Landscape

Both experimental and computational methods contribute to characterizing protein dynamics. Experimental techniques like nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM), and hydrogen-deuterium exchange mass spectrometry can capture conformational changes to varying degrees [1]. However, these methods often face limitations due to rigorous crystallization requirements, or the challenges of interpreting sparse, ambiguous, and noisy data [1].

Computational approaches have emerged as powerful complements, with molecular dynamics (MD) simulations providing particularly valuable insights by directly simulating the physical movements of atoms and molecules over time [3] [1]. MD simulations model protein conformational change by implementing fundamental laws of motion on an atom-by-atom basis, accurately predicting dynamic behavior in various environments [3]. The resulting trajectories provide a time-dependent sampling of conformational space, offering a representation of a system's potential energy landscape [3].

Advanced Sampling and Ensemble Methods

Conventional molecular dynamics (cMD) faces timescale limitations, often preventing direct assessment of rare transition events between conformational states [3]. To overcome these barriers, accelerated molecular dynamics (aMD) utilizes a robust bias potential function to simulate transitions between different potential energy minima more efficiently [3]. This approach reduces computational time spent at energy minima and increases the system's ability to overcome potential barriers, all while converging to the proper canonical distribution [3].

In the post-AlphaFold era, artificial intelligence has revolutionized structural prediction. Ensemble methods like FiveFold combine predictions from multiple complementary algorithms (AlphaFold2, RoseTTAFold, OmegaFold, ESMFold, and EMBER3D) to model conformational diversity explicitly [2]. This approach acknowledges and captures the inherent conformational heterogeneity of proteins, moving beyond single-structure paradigms toward ensemble-based approaches that are particularly valuable for modeling IDPs and multiple conformational states relevant to drug discovery [2].

Table 1: Comparison of Computational Methods for Studying Protein Dynamics

| Method | Key Principle | Advantages | Limitations | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classical MD (cMD) | Simulates physical movements based on Newton's laws [3] | Physically realistic, all-atom detail [3] | Limited to nanosecond-microsecond timescales; computationally expensive [3] | Local fluctuations, solvent interactions, small-scale transitions [3] |

| Accelerated MD (aMD) | Adds bias potential to overcome energy barriers [3] | Enhanced sampling of conformational space; preserves canonical distribution [3] | Requires careful parameter selection (boost energy); reweighting needed for kinetics [3] | Rare events, large-scale conformational transitions [3] |

| FiveFold Ensemble | Combines predictions from five algorithms [2] | Models conformational diversity; less dependent on MSAs [2] | Consensus building adds complexity; computational cost of multiple algorithms [2] | IDPs, multiple conformational states, drug discovery [2] |

| PCA-MD Analysis | Reduces dimensionality of MD trajectories [4] | Identifies dominant collective motions; simplifies trajectory analysis [4] | Limited to linear transformations; may miss rare events [4] | Identifying essential dynamics, functional motions [4] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Accelerated Molecular Dynamics (aMD) Simulation

Application: Modeling rare events and conformational transitions in proteins, such as neurotransmitter transporters or enzyme functional cycles [3].

Principle: aMD enhances conformational sampling by applying a nonnegative, continuous bias potential (ΔV(r)) when the system's potential energy falls below a defined threshold (E). This raises potential energy surfaces near minima while leaving barrier regions relatively unaffected, facilitating transitions between states [3].

Step-by-Step Workflow:

System Preparation:

- Obtain initial coordinates from experimental structures (e.g., PDB) or homology models.

- Embed the protein in a physiologically relevant environment (e.g., lipid bilayer for membrane proteins) [3].

- Solvate the system in a water box and add ions to achieve physiological concentration and neutralize the system.

Energy Minimization and Equilibration:

- Perform energy minimization to remove steric clashes.

- Conduct gradual equilibration with position restraints on protein atoms, slowly increasing temperature to the target (e.g., 310 K) and pressure to 1 bar.

aMD Parameter Calculation:

- Run a short conventional MD simulation (1-10 ns) to collect potential energy statistics.

- Calculate the average potential energy (Vavg) and standard deviation from the cMD trajectory.

- Set the boost energy (E) for aMD: E = Vavg + (4-6 × standard deviation) for aggressive acceleration, or lower multiples for more moderate boosting [3].

- Set the tuning parameter (α) to 0.15-0.20 × the number of atoms in the system to determine the depth of the modified potential energy basin [3].

aMD Production Simulation:

- Implement the bias potential using the "snow drift" function: ΔV(r) = (E - V(r))² / (α + (E - V(r))) [3].

- Run the production simulation using aMD-enabled software (NAMD [3] or Amber [3]).

- The simulation clock advances nonlinearly: Δt* = Δt × e^(βΔV[r(ti)]), where β = 1/kBT, accelerating the observed transitions [3].

Trajectory Analysis:

Protocol: Principal Component Analysis (PCA) of MD Trajectories

Application: Identifying essential collective motions and dominant conformational changes from MD simulation data [4].

Principle: PCA reduces the high-dimensionality of MD trajectories (3N coordinates for N atoms) to a lower-dimensional space defined by principal components (PCs)—orthogonal vectors representing the directions of maximum variance in the data, corresponding to the most significant collective motions [4].

Step-by-Step Workflow:

Trajectory Preprocessing:

- Concatenate and align all trajectory frames to a reference structure (usually the first frame or an average structure) using least-squares fitting to remove global rotation and translation.

- Select specific atoms for analysis (typically Cα atoms to capture backbone motions).

Covariance Matrix Construction:

- Calculate the covariance matrix C of atomic positional fluctuations:

- Cij = ⟨(xi - ⟨xi⟩)(xj - ⟨xj⟩)⟩, where xi and xj are the Cartesian coordinates of atoms i and j, and ⟨⟩ represents the time average over all frames [4].

- Calculate the covariance matrix C of atomic positional fluctuations:

Diagonalization:

- Diagonalize the covariance matrix to obtain eigenvalues (λi) and eigenvectors (pi).

- Each eigenvector (pi) represents a principal component—a collective motion direction.

- Each eigenvalue (λi) corresponds to the mean square fluctuation along that PC, indicating its contribution to the total variance [4].

Projection and Analysis:

- Project the original trajectory onto the principal components to generate PC projections: PCi(t) = p_i · (x(t) - ⟨x⟩) for each frame t.

- Analyze the free energy landscape by projecting the trajectory onto the first few PCs: ΔG(PC1, PC2) = -kBT ln P(PC1, PC2), where P is the probability distribution [4].

Interpretation:

- Use a scree plot (eigenvalues vs. mode index) to determine how many PCs are significant [4].

- Visually inspect the motions along each dominant PC to identify biologically relevant conformational changes.

- Analyze the conformational clusters in the reduced PC space.

Workflow for PCA of Molecular Dynamics Trajectories

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagents & Computational Solutions

Table 2: Essential Resources for Protein Dynamics Research

| Resource / Tool | Type | Primary Function | Application Example | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMBER [1] | MD Software Suite | Force field development and MD simulation | Simulation of proteins, nucleic acids, and carbohydrates [1] | Comprehensive set of force fields; supports aMD [3] |

| GROMACS [1] | MD Software Package | High-performance MD simulation | Large-scale systems on HPC clusters [1] | Extremely fast calculation algorithms; free software |

| OpenMM [1] | MD Library | Hardware-accelerated MD simulations | Custom simulation workflows via Python API [1] | GPU acceleration; high flexibility |

| CHARMM [1] | MD Program | Simulation with empirical force field | Complex biomolecular systems [1] | All-atom additive force field |

| ATLAS Database [1] | MD Database | Repository of protein MD simulations | Access to pre-computed simulations of ~2000 proteins [1] | Covers vast structural space; facilitates comparative analysis |

| GPCRmd [1] | Specialized Database | GPCR-focused MD trajectories and analysis | Understanding GPCR activation mechanisms and drug binding [1] | Systematically organized data for membrane protein family |

| AlphaFold2 [2] | AI Structure Prediction | Predicts protein structures from sequence | Initial coordinates for MD simulations; static structure prediction [2] | High accuracy for many single-domain proteins |

| FiveFold [2] | Ensemble Prediction | Generates multiple conformations via algorithm combination | Modeling conformational diversity and IDPs [2] | Integrates 5 algorithms; Protein Folding Shape Code (PFSC) |

Biological Applications and Case Studies

Case Study: CRISPR-Cas12a Activation Mechanism

Research employing Gaussian accelerated MD simulations has revealed how specific mutations (e.g., K949A) in the CRISPR-Cas12a system induce conformational changes that drive an effective target-binding mechanism [5]. These simulations demonstrated that mutations can alter the energy landscape and facilitate conformational transitions essential for function, providing insights crucial for optimizing genome-editing tools.

Case Study: SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein Dynamics

Deep learning approaches applied to MD simulations of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein receptor-binding domain (RBD) have successfully identified non-trivial conformational changes induced by point mutations [6]. These structural alterations influence viral infectivity and immunogenicity. The 2D-RMSD analysis revealed significant fluctuations in the receptor-binding motif (RBM), particularly in the β₁′/β₂′-C loop, with RMSD values reaching 5Å during simulation for mutations that enable immune evasion [6].

Case Study: HIV-1 Protease and Drug Resistance

PCA of MD simulations has provided crucial insights into drug resistance mechanisms in HIV-1 protease (HIV-1-pr) variants [4]. Studies comparing inhibitors DRV and 4UY revealed that 4UY binds more strongly to mutant HIV-1-pr variants, with PCA showing that 4UY binding promotes flap closing—a key conformational change in protease function [4]. Thermodynamic calculations confirmed 4UY's stronger binding affinity by 4.3–6.4 kcal/mol, demonstrating how dynamics inform drug design [4].

Integrating Methods for Conformational Ensemble Determination

The transition from analyzing static snapshots to characterizing dynamic ensembles represents a fundamental advancement in structural biology. Methods like aMD, PCA, and AI-driven ensemble modeling are providing unprecedented insights into the conformational landscapes that govern protein function. This paradigm shift is particularly transformative for drug discovery, where understanding dynamic transitions enables targeting of previously "undruggable" proteins through allosteric mechanisms and conformation-specific inhibitors. As these methodologies continue to evolve and integrate with experimental data, they will deepen our understanding of biological mechanisms and accelerate the development of novel therapeutic strategies.

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation stands as a cornerstone technique in computational biology, enabling researchers to probe the structural and dynamic properties of biomolecules at an atomistic level. This application note details the core components of MD simulations, focusing on the synergistic application of Newton's classical mechanics and empirically derived force fields to study biomolecular conformational changes. Within drug development, these simulations provide critical insights into mechanisms of action, protein-ligand interactions, and allosteric regulation that are difficult to capture through experimental methods alone. We present here both the theoretical foundation and practical protocols for implementing these methods effectively, with particular emphasis on recent advancements in force field technology.

Theoretical Foundation: The Physics of Molecular Simulation

Newton's Laws as the Governing Framework

At its core, molecular dynamics relies on Newton's second law of motion, expressed mathematically for a particle i as: Fi = m__i_a_i_, where *Fi is the force exerted on the particle, m_i_ is its mass, and *ai is its acceleration [7] [8]. In MD simulations, this equation is recast in terms of the potential energy gradient: F1 = -∇iV({rj}), where F1 represents conservative forces, -∇iV is the gradient of potential energy, and {rj} denotes atomic positions [8]. This formulation directly connects the forces driving atomic motion to the underlying potential energy function, creating a deterministic framework where initial atomic positions and velocities dictate subsequent system evolution.

Numerical Integration of Equations of Motion

Solving Newton's equations for complex biomolecular systems requires robust numerical integration techniques. The Velocity Verlet algorithm has emerged as the preferred method due to its numerical stability and favorable energy conservation properties [7]. This algorithm calculates particle positions and velocities at each time step through the following sequence:

- Compute new positions: r(t + Δt) = r(t) + v(t)Δt + (1/2)a(t)Δt²

- Calculate velocities at half-step: v(t + Δt/2) = v(t) + (1/2)a(t)Δt

- Determine new forces and accelerations: a(t + Δt) = -∇V({r(t + Δt)})/m

- Complete velocity update: v(t + Δt) = v(t + Δt/2) + (1/2)a(t + Δt)Δt

This symplectic integrator preserves phase space volume, ensuring excellent energy conservation even with relatively large time steps (typically 1-2 femtoseconds) [7]. The alternative semi-implicit Euler method demonstrates significantly poorer energy conservation, with errors approximately 100 times greater than Velocity Verlet at equivalent time steps [7].

Force Fields: The Molecular Mechanics Engine

Force fields constitute the mathematical framework that defines potential energy contributions within a molecular system. These empirically parameterized functions describe both bonded interactions (maintaining structural integrity) and non-bonded interactions (capturing intermolecular forces) [9] [10].

Table 1: Fundamental Components of Biomolecular Force Fields

| Energy Component | Mathematical Form | Physical Basis | Key Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bond Stretching | V = ½kb(r - r₀)² | Harmonic vibration along covalent bonds | Equilibrium bond length (r₀), force constant (k*b) |

| Angle Bending | V = ½kθ(θ - θ₀)² | Harmonic vibration of bond angles | Equilibrium angle (θ₀), force constant (k*θ) |

| Torsional Rotation | V = ½Vn[1 + cos(nφ - γ)] | Rotation around bonds with periodicity | Barrier height (V*n), periodicity (n), phase (γ) |

| van der Waals | V = 4ε[(σ/r)¹² - (σ/r)⁶] | Lennard-Jones potential for transient dipoles | Well depth (ε), collision diameter (σ) |

| Electrostatic | V = (q_i_q_j_)/(4πε₀εr*r) | Coulomb's law for charged interactions | Atomic partial charges (q), dielectric constant (ε*r) |

Table 2: Comparison of Modern Force Field Types for Biomolecular Simulations

| Force Field Type | Representative Examples | Resolution | Strengths | Limitations | Best Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Additive All-Atom | AMBER, CHARMM, OPLS-AA | Atomistic with fixed charges | Computational efficiency; extensive validation | Limited polarization effects; fixed charge distribution | Routine protein folding; ligand binding [9] |

| Polarizable | Drude-2013, AMOEBABio09 | Atomistic with responsive charges | Enhanced accuracy for electrostatic interactions | Increased computational cost (~3-5x); complex parameterization | Membrane systems; ion channel permeation [9] |

| Coarse-Grained | Martini 3, GōMartini | 3-5 heavy atoms per bead | Extended spatiotemporal access (μs-ms scale) | Loss of atomic detail; empirical parameterization | Large complexes; membrane remodeling [11] |

| Structure-Based | Gō-like models | Simplified contact maps | Efficient sampling of folding landscapes | Requires known native structure; limited transferability | Protein folding mechanisms; mechanical unfolding [11] |

| Machine Learning | ANI, Neural Network Potentials | Varies by implementation | High accuracy from quantum data | Extensive training requirements; computational cost | Quantum-mechanical property prediction [9] |

The Martini 3 protein model represents a significant advancement in coarse-grained force fields, now utilizing uniform P2 beads for most backbone particles regardless of secondary structure, with exceptions for specific residues (GLY, ALA, VAL, PRO) to better represent polarity and size variations [11]. This evolution from the previous Martini 2 implementation, which used different bead types (P5, Nda, N0) based on secondary structure, improves the balance between chemical specificity and computational efficiency.

GōMartini 3: A Hybrid Approach for Conformational Changes

The GōMartini 3 model represents an innovative synthesis of structure-based and physics-based approaches, combining a virtual-site implementation of Gō models with the Martini 3 coarse-grained force field [11]. This hybrid methodology maintains the computational advantages of coarse-grained modeling while enabling the study of substantial conformational changes in diverse biological environments.

The potential energy in the Gō model is constructed as: U_Gō_ = ∑i

Table 3: Performance Metrics of GōMartini 3 Across Application Domains

| Application Domain | System Type | Simulation Timescale | Key Performance Outcome | Comparison to All-Atom |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein-Membrane Binding | Pleckstrin Homology (PH) domain with PI(4,5)P₂ | Microsecond | Accurate membrane recruitment and orientation | Comparable binding pose at 1/1000th computational cost |

| Protein-Ligand Interactions | Benzene binding to T4 Lysozyme | Microsecond | Reproduced binding pocket geometry and affinity | Similar binding free energy (±0.5 kcal/mol) |

| Allosteric Pathways | Cu,Zn Superoxide Dismutase | Sub-millisecond | Identified conserved communication networks | Confirmed by mutant simulations and experimental data |

| AFM Force Spectroscopy | Antigen:Antibody complexes | Nanosecond | Quantified mechanical stability and unfolding pathways | Force profiles within experimental error margins |

Experimental Protocols

Standard Protocol for MD Simulation of Protein Conformational Changes

Objective: Characterize the conformational landscape of a biomolecule using all-atom molecular dynamics. System Preparation:

- Obtain initial coordinates from experimental structure (PDB) or homology modeling.

- Solvate the protein in an appropriate water box (TIP3P, TIP4P) with ≥10 Å padding.

- Add physiological ion concentration (0.15 M NaCl) using Monte Carlo ion placement.

- Energy minimize using steepest descent (1000 steps) until convergence (<1000 kJ/mol/nm).

Equilibration:

- Perform NVT equilibration (100 ps) using velocity rescaling thermostat (310 K) with heavy atom position restraints (1000 kJ/mol/nm²).

- Conduct NPT equilibration (100 ps) using Parrinello-Rahman barostat (1 atm) with reduced position restraints (400 kJ/mol/nm²).

- Execute unrestrained NPT equilibration (1 ns) to stabilize density.

Production Simulation:

- Initiate production MD using Velocity Verlet integration with 2 fs time step.

- Maintain temperature (310 K) with velocity rescaling thermostat and pressure (1 atm) with Parrinello-Rahman barostat.

- Employ LINCS constraints for all bonds involving hydrogen.

- Use Particle Mesh Ewald for long-range electrostatics with 1.2 nm cutoff.

- Simulate for duration sufficient to observe phenomenon of interest (typically 100 ns - 1 μs).

Analysis:

- Calculate root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) to assess stability.

- Determine root-mean-square fluctuation (RMSF) for residue flexibility.

- Perform principal component analysis (PCA) on trajectory to identify essential dynamics.

- Employ Markov state models to characterize conformational states.

Specialized Protocol for GōMartini 3 Simulations

Objective: Study large-scale conformational changes or protein-environment interactions. System Setup:

- Convert all-atom structure to Martini 3 representation using martinize2 script.

- Define elastic network using Cα atoms within 0.9-1.2 nm cutoff (if maintaining native structure).

- For GōMartini, define native contacts from reference structure (5 Å heavy atom cutoff).

- Solvate with standard Martini water at 1.1 nm minimum padding.

- Add ions to neutralize and achieve 0.15 M salt concentration.

Simulation Parameters:

- Use 20-30 fs time step for integration.

- Maintain temperature with velocity rescaling thermostat (310 K) and pressure with Berendsen barostat (1 atm).

- Apply reaction-field electrostatics with 1.1 nm cutoff and ε*rf = 15.

- Run simulation for 1-10 μs depending on system size and biological process.

Enhanced Sampling:

- Implement metadynamics for free energy calculations of conformational transitions.

- Use umbrella sampling for potential of mean force along reaction coordinates.

- Employ parallel tempering for improved sampling of rugged energy landscapes.

Workflow for Standard All-Atom MD Simulation

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Software Tools for Biomolecular MD Simulations

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| GROMACS | MD Engine | High-performance MD simulation | Optimal for large systems on HPC clusters; extensive analysis tools |

| AMBER | MD Suite | Biomolecular simulation package | Specialized force fields for proteins/nucleic acids; advanced sampling |

| CHARMM-GUI | Web Portal | Input file generation | Streamlines setup of complex systems (membranes, solutions) |

| VMD | Visualization | Trajectory analysis and rendering | Flexible scripting; extensive plugin ecosystem |

| MDAnalysis | Python Library | Trajectory analysis | Programmatic analysis workflow; customization |

| PLUMED | Plugin | Enhanced sampling | Meta-dynamics; umbrella sampling; collective variables |

| PACKMOL | Tool | Initial system configuration | Molecular packing in simulation boxes |

| CCP5 | Software Suite | Materials modeling | Polymeric materials; interfacial systems |

Table 5: Key Force Fields for Biomolecular Conformational Studies

| Force Field | Best Applications | Strengths | Water Model | Latest Version |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CHARMM36 | Membrane proteins; lipids | Accurate lipid bilayers; extensive validation | TIP3P | 2021 update |

| AMBER ff19SB | Proteins; nucleic acids | Optimized backbone torsions | OPC, TIP4P-Ew | 2019 |

| Martini 3 | Large complexes; membranes | Speed; chemical specificity | Martini water | 2023 |

| GōMartini 3 | Conformational changes | Hybrid approach; environmental effects | Martini water | 2025 [11] |

| CHARMM Drude | Polarizable systems | Electronic responsiveness | SWM4-NDP | 2020 |

Advanced Applications in Drug Discovery

The integration of advanced force fields with molecular dynamics has enabled transformative applications in structure-based drug design. Free energy perturbation (FEP) calculations now provide reliable predictions of relative binding affinities for congeneric ligand series, with accuracy approaching experimental uncertainty (±1 kcal/mol) [9]. These methods directly support lead optimization campaigns by prioritizing synthetic efforts toward high-affinity compounds.

For challenging targets involving protein-protein interactions (PPIs), the emergence of molecular glues and proteolysis-targeting chimeras (PROTACs) has created new demands for accurate modeling of ternary complex formation [9]. The GōMartini 3 approach demonstrates particular promise in this domain, enabling simulations of target-ligand-target systems on biologically relevant timescales while maintaining sufficient chemical specificity to inform molecular design.

Force Field Selection Guide for Biomolecular Applications

Molecular dynamics simulations, powered by the continuous refinement of force fields and integration of Newtonian physics, have become an indispensable tool for investigating biomolecular conformational changes. The emergence of hybrid approaches like GōMartini 3 represents a significant advancement, bridging structure-based and physics-based methodologies to address complex biological questions. As force fields continue to evolve—incorporating polarizability, addressing chemical modifications, and leveraging machine learning—the predictive power of MD simulations will further expand. For drug development professionals, these computational approaches now provide actionable insights that complement experimental structural biology, enabling more rational and efficient therapeutic design across diverse target classes.

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations have become an indispensable tool for probing the dynamic nature of biomolecules, providing atomic-level insights into processes that are often difficult to capture experimentally. This application note explores how MD simulations reveal critical biomolecular processes—folding, binding, and allostery—within the context of research on biomolecular conformational changes. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding these processes is fundamental to elucidating disease mechanisms and designing novel therapeutics, particularly as allosteric drugs offer advantages in specificity and reduced off-target effects [12]. MD simulations facilitate the investigation of conformational changes over various timescales, from sub-nanosecond to millisecond events, enabling the identification of transient states and cryptic allosteric sites crucial for protein function and regulation [12].

Key Biomolecular Processes and Quantitative Insights

MD simulations provide quantitative data on the dynamic behavior of biomolecular systems. The table below summarizes key metrics and parameters used to investigate folding, binding, and allostery.

Table 1: Key Quantitative Metrics in Biomolecular MD Simulations

| Process | Key Metric | Typical Scale/Value | Computational Method | Biological Insight |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Folding | Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) | 1-10 Å (Backbone) | MD Trajectory Analysis [13] | Protein structural stability and convergence. |

| Radius of Gyration | Molecular dependent (Å) | MD Trajectory Analysis [13] | Compactness of the protein structure. | |

| Binding | Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF) | Per-residue (Å) | MD Trajectory Analysis [14] | Flexibility of residues; identifies key binding regions. |

| Binding Free Energy (ΔG) | kcal/mol | MM/PBSA, Thermodynamic Integration | Quantification of binding affinity. | |

| Protein-Ligand Interaction Fingerprints | - | Post-MD Analysis [15] | Specific atomic interactions over time. | |

| Allostery | Dynamic Residue Network (DRN) | Shortest Path Length (residues) | Network Analysis of MD Trajectories [16] | Identifies potential allosteric communication pathways. |

| Correlation Analysis | Covariance Matrix | Essential Dynamics (PCA) [15] | Collective motions and correlated residues. | |

| Free Energy Landscape (FEL) | kcal/mol vs. Collective Variables | Enhanced Sampling (MetaD, aMD) [12] | Maps stable states and transition pathways. |

Advanced computational methods have been developed to analyze these complex biomolecular processes. For instance, the Neural Relational Inference (NRI) model, a graph neural network, can learn long-range allosteric interactions from MD trajectories by treating proteins as dynamic networks of interacting residues [14]. Furthermore, tools like STINGAllo leverage machine learning with 54 optimized internal protein nanoenvironment descriptors to predict allosteric site-forming residues at single-residue resolution, achieving a 78% success rate on benchmark datasets [17].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Probing Allosteric Inhibition of hACE2 for Viral Entry Blockade

This protocol details an MD-based approach to identify and characterize a novel allosteric site on the host-cell receptor hACE2 (angiotensin-converting enzyme 2) to disrupt its interaction with the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein [16].

Workflow Diagram: Allosteric hACE2 Modulation Study

Detailed Methodology:

System Preparation:

- Structures: Retrieve the crystal structure of the hACE2-spike RBD complex (e.g., PDB ID: 6M0J). Separate the spike RBD and hACE2 into individual PDB files.

- Ligand: A reference allosteric modulator (e.g., SB27012) is drawn and optimized using density functional theory (DFT) at the B3LYP/6-311G (d,p) level with Gaussian 16 [16].

Molecular Docking:

- Perform blind docking of the optimized reference molecule into the entire hACE2 protein using AutoDock Vina in PyRx 0.8 to identify a potential allosteric site.

- Dock the wild-type spike RBD to the resulting protein-ligand complex using HADDOCK2.4 to model the ternary system [16].

MD Simulation Setup (using GROMACS):

- Force Fields: Generate protein topology with AMBER ff99SB. Generate ligand topology and parameters using ACPYPE (AnteChamber).

- Solvation and Ions: Solvate the complex in a cubic box with a 10 Å diameter using the TIP3P water model. Neutralize the system with 0.15 mol L⁻¹ of Na⁺ and Cl⁻ counterions.

- Energy Minimization: Employ the steepest descent integrator for 5000 steps until the force convergence is below 1000 kcal mol⁻¹ nm⁻¹ [16].

Production and Analysis:

- Run unbiased, microsecond-scale MD simulations of the hACE2-RBD complex with and without the allosteric modulator.

- Dynamic Network Analysis: Construct a dynamic residue network (DRN) of Cα atoms. Calculate the shortest suboptimal path to identify the allosteric communication pathway between the allosteric site and the RBD interface [16].

- Pharmacophore Modeling & HTVS: Develop a structure-based pharmacophore from critical modulator-protein interactions. Use it for high-throughput virtual screening (HTVS) of large molecular databases (e.g., ~0.35 billion molecules) to identify more effective modulators [16].

Protocol 2: Uncovering Long-Range Allosteric Pathways with Neural Relational Inference

This protocol uses a Graph Neural Network (GNN) to infer latent allosteric interactions and pathways from MD simulation trajectories [14].

Workflow Diagram: NRI-Based Allostery Analysis

Detailed Methodology:

System Setup and MD Simulation:

- Prepare the system of interest (e.g., full-length Pin1) in both apo and ligand-bound (e.g., FFpSPR-bound) states.

- Perform MD simulations for both systems to generate trajectories capturing the dynamics.

Data Preparation for NRI:

- Extract the Cα atom coordinates from the MD trajectories to represent each residue as a node in the graph.

NRI Model Training:

- Architecture: Use an encoder-decoder architecture. The encoder takes the MD trajectories and infers a distribution over latent edge types (interactions) between residue nodes. The decoder learns a generative model of the dynamics based on these inferred interactions.

- Training: Train the model by minimizing the reconstruction error between the reconstructed and original MD trajectories [14].

Pathway Analysis:

- After training, the model outputs a latent interaction graph. Analyze this graph to identify the strongest learned edges between residues and different domains.

- Calculate the shortest pathways from the allosteric site (e.g., the WW domain in Pin1) to the active site (e.g., the catalytic loop in Pin1) based on the learned edges.

- Compare the pathways and residue frequencies in the apo and bound states to understand how ligand binding alters allosteric communication. Validate findings against known functional mutation sites [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Item/Tool Name | Function/Application | Relevant Protocol/Section |

|---|---|---|

| GROMACS | A software package for performing MD simulations; used for energy minimization, equilibration, and production runs. [16] | Protocol 1 |

| AMBER ff99SB | A force field for proteins, providing parameters for calculating potential energy and atomic forces. [16] | Protocol 1 |

| AutoDock Vina | A program for molecular docking, used for predicting bound conformations and binding affinities of small molecules. [16] | Protocol 1 |

| HADDOCK2.4 | An information-driven docking software for modeling biomolecular complexes. [16] | Protocol 1 |

| STINGAllo Web Server | A machine learning-based web server for high-throughput prediction of allosteric sites and residues. [17] | Section 2 |

| Neural Relational Inference (NRI) Model | A graph neural network model to infer latent, dynamic interactions between residues from MD trajectories. [14] | Protocol 2 |

| OpenMM | A high-performance toolkit for MD simulation, used in automated workflows like MDCrow. [13] | Automated Workflows |

| MDTraj | A Python library for analyzing MD simulations trajectories, e.g., calculating RMSD, RMSF. [13] | Automated Workflows |

| Metadynamics (MetaD) | An enhanced sampling technique to accelerate exploration of conformational space and reconstruct free energy landscapes. [12] | Table 1 |

Automated Workflows and Future Perspectives

Automation is transforming MD research. Frameworks like MDCrow leverage Large Language Models (LLMs) to automate complex MD workflows. MDCrow uses over 40 expert-designed tools for tasks ranging from retrieving PDB files and setting up simulations with OpenMM to performing analyses with MDTraj [13]. Similarly, DynaMate provides a modular multi-agent template for generating, running, and analyzing molecular simulations, significantly reducing the time required for repetitive tasks [18]. These tools lower the barrier to entry for non-experts and enhance the productivity of seasoned researchers. The integration of AI agents with advanced simulation and analysis methods, such as the NRI model and STINGAllo, points toward a future where the prediction of allosteric mechanisms and the design of modulators can be conducted with increasing speed and accuracy, accelerating therapeutic discovery [17] [14] [13].

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation is a pivotal tool in structural biology, capable of providing full atomic details of biomolecular processes unmatched by experimental techniques. However, a profound challenge limits its utility: the massive gap between the time scales accessible by standard MD simulation (typically microseconds) and the time scales of fundamental functional processes such as conformational changes, ligand binding, and allostery (milliseconds to hours). This disparity, often referred to as the "timescale barrier," prevents the direct simulation of many biologically critical phenomena, making enhanced sampling methods not merely beneficial but essential for advancing research in drug development and molecular biology.

This application note examines the current state of enhanced sampling methodologies, focusing on practical implementations for studying conformational changes in proteins and RNA. We provide a structured comparison of approaches, detailed experimental protocols, and visualization of workflows to equip researchers with actionable strategies for overcoming the sampling bottleneck in their computational studies.

Current Methodologies for Enhanced Sampling

Enhanced sampling methods can be broadly categorized into two branches: those focusing on sampling important metastable conformations, and those focusing on sampling the transition dynamics between them [19]. The table below summarizes the key methodologies, their underlying principles, and representative applications.

Table 1: Enhanced Sampling Methods for Biomolecular Conformational Changes

| Method Category | Key Principle | Representative Techniques | Typical Applications | Key Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Collective Variable (CV)-Based Sampling | Accelerates sampling by applying bias potentials along user-selected collective variables | Umbrella Sampling, Metadynamics, Adaptive Biasing Force [19] | Conformational transitions, ligand binding/unbinding, free energy calculations | A priori knowledge to select relevant CVs; risk of "hidden barriers" with poor CV choice [19] |

| Generative Deep Learning | Learns physical principles of conformational changes from MD data to generate novel synthetic conformations | Internal Coordinate Net (ICoN) [20] | Sampling conformational ensembles of highly dynamic proteins (e.g., Aβ42 monomer) | Molecular dynamics simulation data for training |

| True Reaction Coordinate (tRC) Methods | Identifies and biases the essential coordinates that control conformational changes and energy relaxation | Generalized Work Functional (GWF) [19] | Protein conformational changes (e.g., HIV-1 protease flap opening) | Single protein structure as input; computes tRCs from energy relaxation simulations [19] |

| Generative Committor-Guided Sampling | Combines generative models with committor analysis to discover transition pathways without predefined variables | Gen-COMPAS [21] | Protein folding, binding-upon-folding, large-scale conformational changes | Short unbiased simulations from metastable states for initial training |

| Coarse-Grained Modeling | Simplifies representation to reduce degrees of freedom and smooth energy landscape | GōMartini 3 [11] | Protein-membrane binding, protein-ligand interactions, large-scale domain motions | Known native structure for Gō model parameterization |

Protocols for Key Enhanced Sampling Techniques

Protocol: Sampling with True Reaction Coordinates via Energy Relaxation

This protocol, adapted from [19], enables predictive sampling of conformational changes using true reaction coordinates (tRCs) computed from energy relaxation simulations, requiring only a single protein structure as input.

Materials and Replicates:

- Starting Structure: A single protein structure (e.g., from PDB, AlphaFold)

- Software: MD package with enhanced sampling capabilities (e.g., GROMACS, NAMD, OpenMM)

- System Setup: Solvate protein in appropriate water model, add ions to physiological concentration

- Replicates: Minimum of 3 independent simulations with different initial random seeds

Procedure:

- System Preparation and Equilibration

- Prepare the initial structure using PDB2GMX or similar tool

- Solvate the protein in a triclinic or dodecahedral water box with 1.0-1.5 nm minimum distance from protein to box edge

- Add ions to neutralize system and achieve 0.15 M NaCl concentration

- Energy minimize using steepest descent until Fmax < 1000 kJ/mol/nm

- Equilibrate with position restraints on protein heavy atoms (NPT ensemble, 310K, 1 bar, 100 ps)

Energy Relaxation Simulation and tRC Identification

- Run 10-50 ns of unbiased MD simulation to sample energy relaxation

- Compute potential energy flows (PEFs) through individual coordinates using: dWᵢ = - (∂U(q)/∂qᵢ) dqᵢ [19]

- Apply Generalized Work Functional (GWF) method to generate singular coordinates (SCs)

- Identify tRCs as SCs with highest PEFs [19]

Enhanced Sampling with tRC Bias

- Apply bias potential (e.g., metadynamics, umbrella sampling) on identified tRCs

- Run biased simulation for 100-500 ns, monitoring convergence

- For HIV-1 protease, this approach accelerated flap opening from ~10⁵ s to 200 ps [19]

Trajectory Analysis and Validation

- Extract conformational clusters using clustering algorithms (e.g., GROMOS)

- Validate against experimental data (e.g., EPR, FRET) where available

- Generate committor distributions to verify transition states (pB ≈ 0.5)

Diagram Title: tRC Identification and Enhanced Sampling Workflow

Protocol: Generative Discovery of Transition Pathways (Gen-COMPAS)

The Gen-COMPAS framework [21] combines generative diffusion models with committor analysis to reconstruct transition pathways without predefined collective variables at a fraction of the cost of conventional methods.

Materials and Replicates:

- Initial Structures: Representative structures of reactant (A) and product (B) states

- Software: Gen-COMPAS implementation (available from authors), MD simulation package

- Computing Resources: GPU-accelerated computing nodes

- Replicates: 5-10 iterations of the generative-sampling cycle

Procedure:

- Initial Sampling of Metastable States

- Run short (1-2 ns) unbiased MD simulations from states A and B

- Collect 100-500 conformations from each state as initial training set

Generative Model Training

- Train diffusion model on collected conformations

- Generate intermediate conformations connecting states A and B

Committor Prediction and Transition State Identification

- Learn high-dimensional committor function (q) directly in conformational space

- Identify near-transition structures with committor values q ≈ 0.5

Targeted Sampling and Iteration

- Run targeted MD simulations from states A and B toward identified intermediates

- Shoot unbiased MD simulations from points near separatrix (q = 0.5)

- Incorporate newly generated data to retrain diffusion model and committor predictor

- Repeat for 5-10 iterations until convergence of free energy landscape

Pathway Analysis and Validation

- Extract transition-state ensembles (TSE)

- Construct committor maps projected onto interpretable CVs

- Compute free-energy landscapes and identify dominant pathways

- Validate against experimental kinetic data where available

Diagram Title: Gen-COMPAS Iterative Sampling Framework

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools and Methods for Enhanced Sampling Studies

| Resource/Method | Type | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| GROMACS | MD Software Package | High-performance molecular dynamics simulations | Production MD runs, efficient on CPU and GPU clusters; widely used for biomolecular systems |

| PLUMED | Enhanced Sampling Plugin | Collective variable definition and analysis | Couples with major MD packages for metadynamics, umbrella sampling, and other CV-based methods |

| Gen-COMPAS | Generative Sampling Framework | Committor-guided path sampling without predefined CVs | Discovering transition pathways for protein folding, conformational changes [21] |

| GōMartini 3 | Coarse-Grained Force Field | Balanced structure- and physics-based modeling | Studying large conformational changes, protein-membrane interactions, mechanostability [11] |

| True Reaction Coordinates (tRCs) | Theoretical Concept & Method | Essential coordinates controlling conformational changes | Optimal CVs for accelerating barrier crossing in protein conformational changes [19] |

| Committor Analysis (pB) | Analytical Method | Probability of reaching product before reactant state | Identifying transition states, validating reaction coordinates, quantifying progress [19] |

| Internal Coordinate Net (ICoN) | Deep Learning Model | Learns physical principles from MD data for conformation generation | Sampling conformational ensembles of highly dynamic proteins and IDPs [20] |

The field of enhanced sampling is undergoing a transformative shift from reliance on intuitive collective variables to physics-based and machine-learning-driven approaches. Methods that identify true reaction coordinates through energy relaxation [19] or leverage generative models with committor analysis [21] represent promising directions for achieving predictive sampling of biomolecular conformational changes. These approaches demonstrate that the key to bridging the timescale gap lies not in brute force computational power, but in smarter sampling strategies that focus on the essential physics governing molecular transitions.

For drug development professionals, these advances translate to increasingly accurate predictions of ligand binding pathways, allosteric mechanisms, and protein dynamics that underlie biological function and therapeutic intervention. As these methods continue to mature and integrate with experimental structural biology, they promise to make molecular dynamics simulation an even more powerful tool for rational drug design and mechanistic studies of biomolecular function.

Advanced MD Techniques and Their Impact on Drug Discovery

Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations are a cornerstone of modern computational biology, providing atomistic insight into biomolecular function. However, a significant limitation of conventional MD is the insufficient sampling of conformational space due to the rough energy landscapes of biomolecules, which are characterized by many local minima separated by high-energy barriers [22]. This "sampling problem" prevents the simulation of many critical, but rare, biological events, such as large-scale conformational changes in proteins, folding, and ligand binding or unbinding [22] [23].

Enhanced sampling methods have been developed to address this challenge. Among them, accelerated MD (aMD) and its refinement, Gaussian accelerated MD (GaMD), are powerful techniques that enhance conformational sampling without requiring pre-defined collective variables. This application note details the principles, protocols, and applications of these methods, framed within ongoing research on biomolecular conformational changes.

Methodological Foundations

The Sampling Problem in Biomolecular Simulation

Biological molecules possess complex, multi-minima energy landscapes [22]. In conventional MD, the system can become trapped in local energy minima for timescales that far exceed the practical simulation time, leading to non-ergodic sampling where relevant conformational states are never visited. This is particularly problematic for studying functional processes like ligand binding to receptors such as GPCRs, where the timescale can range from microseconds to hours [23]. Enhanced sampling algorithms are designed to mitigate this by facilitating the crossing of energy barriers.

Accelerated Molecular Dynamics (aMD)

Principle: The core idea of aMD is to reduce the height of energy barriers by adding a non-negative boost potential to the system's original potential energy surface [23]. This "boosts" the system in regions where the potential energy is lower than a predefined reference energy, making it easier to escape local minima.

Mathematical Formulation: When the system potential ( V(\vec{r}) ) is below a threshold energy ( E ), a boost potential ( \Delta V(\vec{r}) ) is added [23]: [ \Delta V(\vec{r}) = \frac{(E - V(\vec{r}))^2}{\alpha + (E - V(\vec{r}))} ] where ( \alpha ) is a tuning parameter that controls the shape of the boost potential. The modified potential becomes ( V^*(\vec{r}) = V(\vec{r}) + \Delta V(\vec{r}) ).

Advantages and Limitations: A key advantage of aMD is that it does not require a priori knowledge of the reaction pathway or the selection of collective variables. However, a significant drawback is that the resulting boost potential can exhibit large fluctuations, which complicates the process of reweighting the simulation data to recover unbiased thermodynamic averages [23].

Gaussian Accelerated Molecular Dynamics (GaMD)

Principle: GaMD is an evolution of aMD designed to overcome its reweighting limitations. It adds a harmonic boost potential that follows a near-Gaussian distribution [23]. This property allows for accurate recovery of the original free energy landscape through a "Gaussian approximation" of the reweighting probability.

Mathematical Formulation: The GaMD boost potential is defined as [23]: [ \Delta V(\vec{r}) = \begin{cases} \frac{1}{2} k (E - V(\vec{r}))^2 & V(\vec{r}) < E \ 0 & V(\vec{r}) \geq E \end{cases} ] Here, ( k ) is a harmonic force constant. The parameters ( E ) and ( k ) are determined automatically based on the system's potential energy statistics to ensure the boost potential is both Gaussian and sufficient for overcoming energy barriers [23].

Advantages: GaMD retains the collective-variable-free advantage of aMD while enabling robust energetic reweighting. This makes it particularly suitable for calculating free energy profiles of complex biomolecular processes.

Table 1: Key Features of aMD and GaMD

| Feature | Accelerated MD (aMD) | Gaussian Accelerated MD (GaMD) |

|---|---|---|

| Boost Potential | Non-negative, hyperbolic | Harmonic, Gaussian-distributed |

| Reweighting | Difficult due to large energy noise | Accurate via Gaussian approximation |

| Collective Variables | Not required | Not required |

| Ease of Setup | Requires tuning of (E) and (\alpha) | Parameters (E) and (k) calculated automatically |

| Primary Application | Qualitative exploration of conformational space | Quantitative free energy calculations |

Research Reagent Solutions: A Computational Toolkit

The following table lists key software and computational resources essential for implementing aMD and GaMD simulations.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Tool/Reagent | Function/Description | Availability / Example |

|---|---|---|

| Simulation Software | MD engines with implemented aMD/GaMD algorithms. | AMBER [22] [23], NAMD [22] [23], GROMACS [22] |

| Force Fields | Mathematical functions parameterizing atomic interactions. | CHARMM, AMBER, OPLS-AA |

| System Preparation Tools | Prepares molecular structures for simulation (solvation, ionization). | CHARMM-GUI, tleap (AMBER) |

| Analysis Suites | Tools for trajectory analysis, reweighting, and visualization. | CPPTRAJ (AMBER), VMD, MDAnalysis |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) | CPU/GPU clusters for running computationally intensive simulations. | Local clusters, NSF/XSEDE resources, Cloud computing |

Generalized GaMD Protocol

Below is a detailed workflow for setting up and running a GaMD simulation, which is the recommended method for most applications due to its superior reweighting capabilities.

Step-by-Step Protocol

System Preparation

- Obtain the initial molecular structure (e.g., from PDB, AlphaFold).

- Solvate the system in a water box (e.g., TIP3P water model).

- Add ions to neutralize the system's charge and achieve a physiologically relevant salt concentration.

- Perform energy minimization to remove any steric clashes.

Stage 1: Conventional MD (cMD)

- Run a short, unbiased MD simulation (typically a few nanoseconds) under the desired thermodynamic ensemble (NPT or NVT).

- Purpose: Collect potential energy statistics ((V{max}), (V{min}), (V{avg}), (σV)) required to calculate the GaMD boost parameters ((E) and (k)) [23].

Stage 2: GaMD Equilibration

- Apply the GaMD boost potential using the parameters calculated in Stage 1.

- Run a short simulation to allow the system to equilibrate under the influence of the boost potential.

Stage 3: GaMD Production

- Run an extended GaMD simulation (hundreds of nanoseconds to microseconds) to achieve enhanced sampling.

- Output: Save the trajectory (atomic coordinates), boost potential values, and other relevant energies at a high frequency for subsequent analysis.

Reweighting and Analysis

- Use the recorded boost potential to reweight the simulation and recover the unbiased free energy landscape.

- The Gaussian distribution of the boost potential in GaMD allows for accurate reweighting using the "Gaussian Approximation" method [23].

- Analyze the reweighted trajectory to identify metastable states, conformational changes, and calculate free energy profiles along reaction coordinates of interest.

Applications in Drug Discovery

GaMD has proven particularly effective in elucidating mechanisms central to rational drug design.

Application Note: GPCR Drug Binding

- System: β₂-Adrenergic Receptor (β₂AR) with a bound ligand.

- Objective: Determine the ligand binding pathway and estimate the binding free energy.

- Method: GaMD with dual-potential boost (applied to both total and dihedral potential) for maximum acceleration [23].

- Outcome: GaMD simulations successfully captured the complete pathway of ligand binding and unbinding, providing atomistic details of intermediate states that are difficult to observe experimentally. The free energy profile calculated from reweighted GaMD data gave critical insights into the binding mechanism and affinity [23].

Performance and Acceleration

GaMD can accelerate the simulation of slow biomolecular processes by several orders of magnitude. For instance, in a study on HIV-1 protease, biasing true reaction coordinates identified through advanced methods led to an acceleration of a ligand unbinding process (experimental lifetime of ~10⁶ seconds) to just 200 picoseconds in simulation [19]. This represents a speedup factor of 10¹⁵, demonstrating the immense power of enhanced sampling for probing otherwise inaccessible dynamics.

Table 3: Quantitative Acceleration of Biomolecular Processes via Enhanced Sampling

| Biological System | Process | Experimental/Timescale | Simulation Timescale with Enhanced Sampling | Speedup Factor |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIV-1 Protease | Ligand Unbinding | 8.9 x 10⁵ s [19] | 200 ps [19] | ~ 10¹⁵ |

| GPCRs (e.g., M3) | Ligand Binding | Microseconds to seconds [23] | Nanoseconds to microseconds [23] | 10³ - 10⁶ |

| Fast-folding Proteins | Folding/Unfolding | Microseconds [23] | Nanoseconds [23] | ~ 10³ |

Enhanced sampling methods, particularly GaMD, have moved beyond mere theoretical interest to become practical tools in the computational scientist's arsenal. By effectively addressing the sampling problem inherent to conventional MD, they enable the study of complex biomolecular events—such as conformational changes, folding, and drug binding—at an atomistic level of detail. The ability of GaMD to provide unconstrained enhanced sampling combined with accurate energetic reweighting makes it exceptionally well-suited for applications in computer-aided drug design, where understanding pathways and quantifying free energies are critical for informing and accelerating the development of new therapeutics.

Markov State Models (MSMs) have emerged as a powerful computational framework for bridging the critical gap between the short timescales accessible by all-atom Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations and the long, biologically relevant timescales of biomolecular conformational changes. Processes such as protein folding, functional conformational shifts, and ligand binding often occur on millisecond to second timescales, far exceeding the microsecond-scale reach of even the most extensive MD simulations [24] [25]. MSMs address this challenge by providing a rigorous statistical methodology for integrating data from many short, disparate MD simulations to model long-time dynamics, predict kinetic and thermodynamic properties, and gain mechanistic insight into biomolecular function [24] [26]. This application note details the core principles, construction protocols, and key applications of MSMs, providing a standardized resource for researchers investigating conformational dynamics.

Theoretical Foundations of Markov State Models

An MSM is a discrete-state, discrete-time stochastic model that approximates the continuous conformational dynamics of a molecular system. Its foundation lies in the transfer operator theory, where the model aims to approximate the dominant eigenfunctions and eigenvalues of this operator, which correspond to the slowest dynamical processes in the system [25] [26].

The model is defined by two key components:

- A state space discretization, where the high-dimensional conformational space is partitioned into a set of discrete states, ( S1, S2, ..., S_n ).

- A transition matrix, ( \mathbf{T}(\tau) ), where each element ( T{ij}(\tau) ) represents the conditional probability of transitioning from state ( i ) to state ( j ) after a lag time ( \tau ), such that ( T{ij}(\tau) = \mathbb{P}(x{t+\tau} \in Sj | xt \in Si ) ) [25] [26].

A fundamental property of the transition matrix is that it can be used to compute the system's stationary distribution, ( \boldsymbol{\pi} ), by solving the eigenvalue problem ( \boldsymbol{\pi}^T \mathbf{T} = \boldsymbol{\pi}^T ) [25] [26]. This means MSMs can recover full equilibrium thermodynamics from ensembles of short, non-equilibrium simulations.

The kinetic relaxation timescales inherent to the dynamics are revealed by the eigenvalues, ( \lambdai(\tau) ), of the transition matrix. These are converted into implied timescales via ( ti = -\tau / \ln |\lambda_i(\tau)| ). A core validation test, the implied timescales plot, checks for Markovianity by ensuring these timescales are constant beyond a sufficiently long lag time [27] [28].

Table 1: Key Kinetic Properties Computable from MSMs and Their Biophysical Significance.

| Property | Mathematical Definition | Biophysical Significance | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stationary Distribution | ( \boldsymbol{\pi}^T \mathbf{T} = \boldsymbol{\pi}^T ) | Equilibrium populations of conformational states; related to free energy. | ||

| Implied Timescales | ( t_i = -\tau / \ln | \lambda_i(\tau) | ) | Intrinsic relaxation rates of slow dynamical processes. |

| Mean First-Passage Time (MFPT) | Average time to reach a state ( j ) for the first time, starting from ( i ). | Measures transition rates between functional states (e.g., folded/unfolded). | ||

| Committor Probability | Probability a trajectory from a state ( i ) reaches a target state ( B ) before state ( A ). | Identifies transition states (where committor ~0.5). |

A significant paradigm shift in MSM construction has moved from maximizing the metastability of states (long state lifetimes) to minimizing the approximation error of the transfer operator's slow eigenspaces [25] [26]. This ensures the MSM most accurately captures the long-time statistical dynamics, even if individual states have shorter lifetimes.

Standardized Protocol for MSM Construction

The construction of a validated MSM follows a multi-stage workflow, from feature selection to model analysis. The following protocol, summarized in the diagram below, is recommended for studying functional conformational changes [29].

MSM Construction and Validation Workflow. The process involves initial simulation, data-driven model construction, and final validation/analysis stages.

Stage 1: Simulation Setup

- A. Generate Initial Pathways: For complex functional transitions, begin by generating initial pathways connecting known metastable states (e.g., from crystal structures). Methods include targeted MD, the String method, or action-based approaches like Action-CSA [29].

- B. Perform Ensemble MD: Launch a large number of parallel, short MD simulations. Initial structures can be seeded from the initial pathways, using enhanced sampling methods, or from stochastic unfolding simulations to ensure broad coverage. This ensemble approach is more effective for sampling than a single long trajectory [24] [29].

Stage 2: Model Construction

- C. Feature Selection: The raw Cartesian coordinates from MD are transformed into a set of structural descriptors ("features"). For functional changes in large systems, automatic feature selection is critical.

- D. Dimensionality Reduction: The high-dimensional feature space is projected onto a low-dimensional space of collective variables (CVs) that capture the slowest dynamics.

- E. Clustering & MSM Building: The projected data is clustered into microstates.

- Microstate Clustering: Use k-means or k-centers clustering on the CVs to create 100 to 10,000+ microstates [27] [24].

- Transition Matrix Estimation: Assign every MD frame to a microstate. Count observed transitions between microstates at a lag time ( \tau ) to build a count matrix ( \mathbf{C}(\tau) ), which is normalized to obtain the row-stochastic transition matrix ( \mathbf{T}(\tau) ) [24].

- Coarse-Graining (Optional): Microstates can be lumped into larger, more interpretable metastable macrostates using algorithms like PCCA+ [27].

Stage 3: Model Application

- F. Validation & Analysis: The final, critical step is to validate the model and use it to compute biologically relevant properties.

- Validation: The Chapman-Kolmogorov test checks the Markovianity of the model by comparing the model's predicted state populations over time ( [\mathbf{T}(n\tau)]^n \mathbf{p}(0) ) to those directly observed in the data [27] [29]. Implied timescales analysis ensures timescales are constant above the chosen lag time ( \tau ) [27].

- Analysis: Use Transition Path Theory (TPT) [27] to analyze mechanisms and fluxes between states. Compute Mean First-Passage Times (MFPTs) [28] and identify key transition states via committor analysis [30] or newer deep learning methods like TS-DAR [30].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Software

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for MSM Construction.

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| PyEMMA [27] | Software Library | End-to-end MSM estimation, validation, and analysis. | Implements TICA, clustering, CK test, and TPT. A comprehensive toolkit for standard analyses. |

| MSMBuilder [28] | Software Library | Construction and analysis of MSMs from MD trajectories. | Known for scalability and flexibility in handling large simulation datasets. |

| VAMPNets [29] | Deep Learning Model | Uses neural networks to simultaneously learn optimal state discretizations and the MSM. | Capable of identifying nonlinear collective variables, improving model accuracy. |

| Time-lagged Independent Component Analysis (TICA) [25] [29] | Algorithm | Dimensionality reduction to find slow collective variables. | The most widely used linear method for projecting dynamics before clustering. |

| WESTPA [31] | Software Toolkit | Weighted Ensemble (WE) sampling for rare events. | Used before MSM construction to enhance sampling of rare transitions for more complete models. |

| TS-DAR [30] | Deep Learning Framework | Identification of transition state structures from MD data. | Frames transition states as out-of-distribution data in a hyperspherical latent space. |

Advanced Applications and Future Directions

MSMs have moved beyond protein folding to address complex problems in molecular biology. Notable applications include studying ligand binding and unbinding pathways, functional conformational changes in large kinases like Src kinase, and processive mechanisms such as the translocation of RNA polymerase and DNA motor proteins [29] [30]. These applications demonstrate MSMs' power in connecting atomistic simulations to functional mechanisms and, through forward simulation of experimental observables, to single-molecule and ensemble kinetics experiments [26].

Recent advancements are addressing key limitations and opening new frontiers:

- History-Augmented MSMs (haMSMs): Standard MSMs can be biased for path-based observables like MFPTs when states are short-lived. haMSMs condition transitions on previous macrostate visitation, significantly improving accuracy for kinetic predictions [28].

- Machine Learning Integration: Beyond VAMPNets, new frameworks like quasi-MSMs (qMSMs) use the generalized master equation to model dynamics with far fewer states, simplifying the interpretation of complex functional changes [29]. Generative models like MarS-FM are now using MSMs as a scaffold to generate physically accurate, long-timescale trajectories at a fraction of the computational cost of MD [32].

- Standardized Benchmarking: The field is moving towards rigorous evaluation with frameworks that leverage enhanced sampling (e.g., Weighted Ensemble) and diverse protein datasets to provide fair, reproducible comparisons between different MD and machine learning methods [31].

In the study of biomolecular conformational changes, understanding the pathway and kinetics of transitions is fundamental. The rate of a reaction is governed by the energy difference between the transition state (TS), the highest energy point on the minimum energy path (MEP) between reactants and products, and the reactants themselves [33]. Locating these first-order saddle points on the potential energy surface is therefore crucial for predicting reaction rates and selectivity, which has direct implications for understanding enzyme catalysis and drug-target interactions [33] [34]. However, the high-dimensional space in which biomolecules exist makes locating these states non-trivial [33]. This article details modern computational protocols for identifying transition states and discovering optimal reaction coordinates, with a focus on applications in biomolecular simulation.

Theoretical Foundation

A transition state is formally defined as a first-order saddle point, characterized by a zero gradient and a Hessian matrix (the matrix of second derivatives) with a single negative eigenvalue, which corresponds to the imaginary frequency of the unstable mode [33]. The minimum energy path (MEP) is the path connecting reactants and products that minimizes energy in all directions orthogonal to the path tangent [33].

The concept of a reaction coordinate (RC) or collective variable (CV) is central to this process. An ideal RC is a low-dimensional representation that distinguishes between metastable states and captures the slow, collective motions essential for the transition [35] [36]. The quality of an RC can be quantified by the committor probability, which measures the likelihood that a trajectory initiated from a specific configuration will reach one metastable state before another [36].

Methodologies for Transition State Location

Several algorithms have been developed to locate transition states, each with specific strengths and optimal use cases. The choice of method often depends on the available prior knowledge, such as known reactant and product structures.

Table 1: Comparison of Transition State Search Methods

| Method | Key Principle | Requirements | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|

| Synchronous Transit (LST/QST) [33] | Finds maximum energy point on an interpolated path (linear or quadratic) between reactants and products. | Reactant and product structures. | Simple reactions with a clear, direct path. |

| Nudged Elastic Band (NEB) [33] | Optimizes a series of "images" along the path, connected by springs, to map the MEP. | Reactant and product structures; multiple path images. | Mapping the entire reaction pathway and identifying approximate TS regions. |

| Climbing-Image NEB (CI-NEB) [33] | A variant of NEB where the highest energy image "climbs" against the gradient to the saddle point. | Reactant and product structures; multiple path images. | Directly locating the TS without needing a separate optimization. |

| Dimer Method [33] | Follows the path of lowest curvature uphill using a pair of geometries to estimate curvature without a Hessian. | An initial guess structure. | Systems where calculating the Hessian is expensive; common in periodic DFT. |

| Coordinate Scanning [34] | Scans a suspected reaction coordinate and uses the highest-energy structure as a TS guess. | A suspected bond/angle/dihedral involved in the reaction. | Systems with a single, obvious reaction coordinate. |

| Machine Learning Potentials [37] | Uses ML models trained on quantum chemistry data to rapidly predict energies and forces for TS search. | A pre-trained, accurate ML potential. | High-throughput screening of reaction networks in organic synthesis. |

Protocol: Transition State Optimization via QST

The following protocol is adapted for biomolecular systems using common computational chemistry software.

- Endpoint Preparation: Optimize the reactant and product conformations to their respective local energy minima. Verify using frequency calculations that no imaginary frequencies exist.

- Initial Guess Generation: Use a synchronous transit method (e.g., LST) to generate an initial guess for the transition state geometry by interpolating between the optimized reactant and product.

- TS Optimization: Submit the initial guess to a quadratic synchronous transit (QST) optimizer, such as QST2 or QST3, which refines the path and optimizes the geometry normal to the constraining curve [33].

- TS Verification:

- Perform a frequency calculation on the optimized TS structure.

- Confirm the presence of a single imaginary frequency (negative eigenvalue).

- Animate the imaginary frequency to ensure it corresponds to the expected bond formation/breaking or conformational change.

- IRC Validation: Perform an Intrinsic Reaction Coordinate (IRC) calculation from the verified TS to confirm that it correctly connects to the reactant and product basins.

Advanced Approaches for Reaction Coordinate Discovery

For complex biomolecular transitions, the relevant RC is often not intuitive. Data-driven and machine learning methods can discover optimal RCs from simulation data.

Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA) on Positions

LDA is a supervised technique that finds the linear combination of features that best separates two predefined states [35].

- Principle: Given two sets of data (e.g., folded and unfolded protein structures), LDA finds a projection vector that maximizes the distance between the class means while minimizing the variance within each class [35].

- Application to MD: Atomic positions, once aligned to a global reference to remove rotational and translational degrees of freedom, serve as the input features. The resulting LDA coordinate provides a highly effective RC for enhanced sampling [35].

- Protocol:

- State Definition: Perform two separate simulations, one trapped in State A (e.g., bound conformation) and another in State B (e.g., unbound conformation).

- Alignment and Sampling: Align all simulation snapshots to a common reference structure (e.g., the crystal structure). Uniformly sample configurations from both State A and State B.

- LDA Training: Compute the within-class and between-class scatter matrices from the aligned atomic coordinates and solve the generalized eigenvalue problem to obtain the LDA transformation vector.

- Biased Simulation: Use the LDA projection value as the collective variable in an enhanced sampling simulation (e.g., Metadynamics or Umbrella Sampling) to drive transitions between states and compute the free energy landscape.

Deep Learning for RC Discovery

Machine learning frameworks can learn non-linear RCs that capture complex conformational changes without pre-defined features.

- The AMORE-MD Framework: This framework uses the ISOKANN algorithm to learn a neural network-based membership function,

χ, which approximates the dominant eigenfunction of the molecular dynamics generator [36]. Thisχ-function acts as an optimal RC for the slowest process in the system. - Interpretability: A key advantage of AMORE-MD is its interpretability. The framework allows for:

- Pathway Reconstruction: The

χ-minimum-energy path (χ-MEP) can be found by integrating along the gradient ofχ, providing a representative, atomically detailed transition pathway [36]. - Sensitivity Analysis: The gradient of

χwith respect to atomic input coordinates identifies which specific atoms or distances contribute most to the reaction coordinate, revealing the atomistic mechanism [36].

- Pathway Reconstruction: The

- Workflow: The process is iterative: run MD, train

χ, useχto initialize new enhanced sampling simulations, and retrain to improve coverage of rare events [36].

Machine Learning for Initial TS Guessing

Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) can generate high-quality initial guesses for TS structures, streamlining the optimization process.

- Bitmap Representation: A 2D bitmap representation of the molecular structure around the reaction center is used as input to a CNN, such as ResNet50 [38].

- Genetic Algorithm: A genetic algorithm explores the configuration space of the reacting molecules, and the trained CNN model scores each candidate structure based on its likelihood of being near the true TS [38].

- Performance: This approach has achieved verified TS optimization success rates of 81.8% for hydrofluorocarbons and 80.9% for hydrofluoroethers in challenging hydrogen abstraction reactions [38].

The following diagram illustrates a generalized workflow integrating traditional and machine learning approaches for identifying transition states and reaction coordinates.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Software

Table 2: Key Computational Tools for TS and RC Analysis

| Tool / Resource | Type | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| PLUMED [35] [36] | Software Library | Industry-standard for implementing enhanced sampling methods and analyzing collective variables in MD simulations. |

| DeePEST-OS [37] | Machine Learning Potential | A generic ML potential for rapid transition state searches in organic synthesis, offering DFT-level accuracy at much lower computational cost. |

| Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA) [35] | Statistical Method | A supervised dimensionality reduction technique to create an optimal reaction coordinate from two predefined states. |

| AMORE-MD Framework [36] | Deep Learning Framework | Learns interpretable reaction coordinates and reveals atomistic mechanisms via sensitivity analysis and minimum-energy paths. |