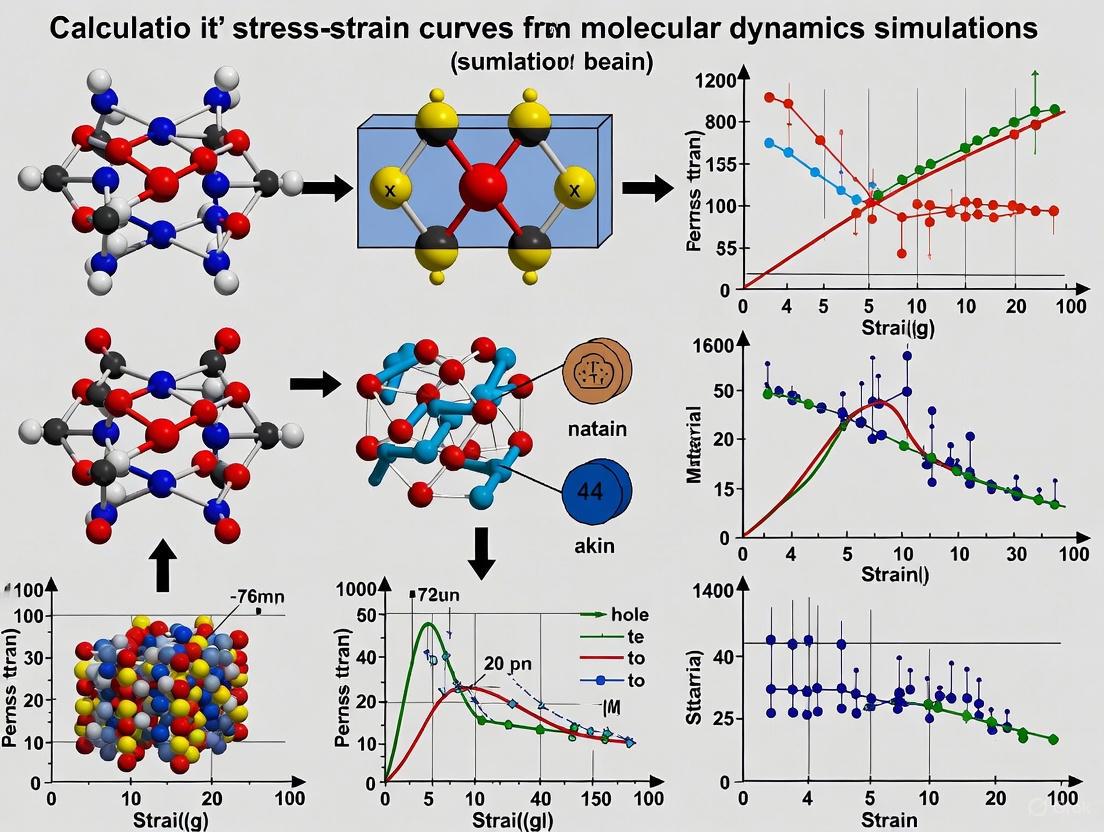

Calculating Stress-Strain Curves from Molecular Dynamics Simulations: A Comprehensive Guide for Materials and Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and scientists on calculating stress-strain curves from molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, covering foundational theory to advanced applications.

Calculating Stress-Strain Curves from Molecular Dynamics Simulations: A Comprehensive Guide for Materials and Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and scientists on calculating stress-strain curves from molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, covering foundational theory to advanced applications. It explores the fundamental principles connecting atomic-scale interactions to macroscopic mechanical properties and details practical implementation methods using popular MD engines like LAMMPS and QuantumATK. The content addresses common troubleshooting scenarios and optimization strategies for reliable results, while also examining validation techniques and emerging approaches that integrate machine learning with MD simulations. Special consideration is given to applications in biomedical and pharmaceutical contexts, including protein mechanics, polymer failure, and composite material performance under physiological conditions.

Understanding the Fundamentals: From Atomic Interactions to Macroscopic Mechanical Properties

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation serves as a fundamental computational technique for predicting the atomic-scale mechanical behavior of materials, bridging the gap between interatomic interactions and macroscopic mechanical properties. At the heart of any MD simulation lies the interatomic potential, a mathematical function that describes the potential energy of a system of atoms as a function of their nuclear coordinates. The accuracy of stress-strain curves derived from MD simulations directly depends on the fidelity of these potentials in capturing the underlying physics of atomic interactions. Stress-strain relationships emerge from the collective response of thousands to millions of atoms to applied deformation, with interatomic potentials calculating the forces that determine this response. This application note establishes the theoretical foundation connecting interatomic potential selection to the prediction of stress-strain behavior, providing protocols for researchers requiring accurate mechanical property prediction from molecular simulations.

Theoretical Framework: Classes of Interatomic Potentials

The choice of interatomic potential represents a critical decision point in MD studies of mechanical properties, with different potential classes offering distinct trade-offs between accuracy, computational cost, and transferability. The table below summarizes the primary categories of interatomic potentials used in materials modeling.

Table 1: Classification of Interatomic Potentials for Mechanical Properties Simulation

| Potential Class | Theoretical Basis | Strengths | Limitations | Representative Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classical Empirical Potentials (e.g., EAM, MEAM) | Parameterized analytical functions fitted to experimental data and/or DFT calculations [1] | Computationally efficient; suitable for large systems and long timescales [2] | Limited transferability; accuracy restricted to fitting domain [3] | MEAM for FeCr alloys [3]; Morse/Buckingham for HAP [2] |

| Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials (MLIPs) | Machine-learned models trained on DFT datasets [4] | DFT-level accuracy; near-ab initio transferability [3] [4] | Higher computational cost than classical potentials; training data dependent [4] | Deep Potential (DP) [3]; MACE [4] |

| Ab Initio (Density Functional Theory) | Quantum mechanical treatment of electron interactions [4] | Highest fundamental accuracy; no empirical parameters [4] | Extremely computationally expensive; limited to small systems (~100-1000 atoms) [4] | r2SCAN meta-GGA [4]; PBE GGA [4] |

The recent emergence of machine learning interatomic potentials (MLIPs) has significantly narrowed the gap between quantum mechanical accuracy and molecular dynamics scalability. For instance, Deep Potential models for FeCr alloys demonstrate remarkable accuracy in predicting high-temperature tensile strength (15 GPa at 1200 K) and fracture strain (32%), outperforming traditional MEAM potentials which struggle with transferability to high-temperature regimes [3]. Universal MLIPs trained on comprehensive datasets like MP-ALOE, which contains nearly 1 million DFT calculations using the accurate r2SCAN meta-GGA across 89 elements, now enable reliable mechanical property prediction across diverse chemical spaces [4].

Computational Protocol: From Atomic Structure to Stress-Strain Curves

This section provides a detailed protocol for calculating stress-strain curves from molecular dynamics simulations, with specific reference to a study on hydroxyapatite (HAP) bi-crystals [2].

System Preparation and Equilibration

- Initial Structure Construction: Build bi-crystal models with specific misorientation angles (e.g., 0°, 14.1°, and 47.0°) to study interface effects on mechanical properties. The system size in the referenced study was approximately 20-30 nm [2].

- Interatomic Potential Selection: Employ a potential that appropriately describes the material chemistry. For ionic crystals like HAP, this requires potentials with Coulombic charge interactions and Buckingham potential for non-bonded interactions, with Morse-type potential for covalent bonds [2].

- Structure Relaxation Protocol:

- Relax the structure at target temperature (300 K) and pressure (1 bar) using an isothermal-isobaric (NPT) ensemble until the root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) indicates convergence [2].

- For interface systems, apply a multi-stage sintering process:

- Stage 1: Increase pressure perpendicular to the interface from 1 bar to 1 GPa over 10 ps

- Stage 2: Maintain 1 GPa pressure for 10 ps

- Stage 3: Decrease pressure back to 1 bar over 10 ps

- Stage 4: Further relax at 1 bar for 10 ps [2]

- Repeat this cycle five times to achieve well-sintered interfaces [2].

Tensile Deformation Simulation

- Crack Introduction: For fracture studies, carefully insert a sharp crack (~5 nm) while maintaining charge neutrality by adjusting the number of molecules based on their charges [2].

- Boundary Condition Application:

- Deformation Protocol: Apply tensile loading by stretching the simulation box along the desired axis at a controlled strain rate (e.g., 0.05 Å/ps) [2]. To minimize fluctuations and hysteresis, use the slowest feasible strain rate given computational constraints [5].

Stress Calculation and Data Processing

- Stress Tensor Calculation: Use the pressure tensor from the simulation for stress calculation, as the virial tensor is primarily appropriate for zero-Kelvin simulations [5]. The pressure tensor components (Px, Py, Pz) provide the stress state in different directions.

- Stress-Strain Curve Generation: Calculate engineering stress as -Pz (for tension along z-axis) and engineering strain as (L - L₀)/L₀, where L is the instantaneous box length and L₀ is the initial length.

- Data Smoothing: Apply smoothing algorithms like running averages to reduce fluctuations in stress-strain data while preserving the underlying trend [5].

Diagram 1: MD Stress-Strain Calculation Workflow. This workflow outlines the key steps for obtaining stress-strain curves from molecular dynamics simulations, from initial structure preparation to final curve generation.

Stress-Strain Interpretation and Physical Insights

The stress-strain curves generated from MD simulations provide atomic-scale insights into deformation mechanisms that are often inaccessible experimentally. In the HAP bi-crystal study, researchers observed distinct mechanical responses depending on interface misorientation angles [2]. The 14.1° mis-oriented bi-crystal exhibited clear crack deflection at the interface, resulting in toughening behavior manifested in the stress-strain curve as continued load-bearing capacity after initial cracking [2]. This demonstrates how MD simulations can directly correlate interfacial atomic structure with macroscopic mechanical performance.

Diagram 2: From Atomic Interactions to Macroscopic Response. This diagram illustrates the theoretical pathway connecting interatomic potentials to macroscopic stress-strain behavior through the calculation of atomic forces and stress tensors.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Computational Tools for Stress-Strain Analysis from MD Simulations

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Function in Stress-Strain Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| MD Simulation Engines | LAMMPS [2], Desmond [6] | Core simulation platforms for performing tensile deformation experiments |

| Interatomic Potentials | MEAM [1], EAM, MLIP [3] [4] | Define energy-force relationships between atoms; critical for accuracy |

| Visualization & Analysis | MS Maestro [6], VMD, OVITO | System setup, trajectory analysis, and result interpretation |

| Data Processing Tools | xmgrace [5], Python (Matplotlib, Seaborn) [7] | Stress-strain curve plotting, data smoothing, and statistical analysis |

| Quantum Mechanics Reference | DFT (r2SCAN [4], PBE) | Generate training data for MLIPs and validate potential accuracy |

The theoretical connection between interatomic potentials and stress-strain behavior represents a cornerstone of molecular dynamics simulation in materials science and drug development. The accuracy of predicted mechanical properties hinges critically on selecting appropriate potentials that capture the essential physics of atomic interactions for the specific material and conditions of interest. While classical potentials offer computational efficiency for large systems, the emerging paradigm of machine learning interatomic potentials trained on high-quality DFT data increasingly provides the accuracy required for predictive materials design. The protocols outlined in this application note provide researchers with a framework for conducting reliable stress-strain calculations, from careful system preparation through appropriate deformation protocols to physically meaningful data interpretation. As MLIP methodologies continue to mature and computational resources expand, MD simulations will play an increasingly vital role in predicting mechanical behavior across diverse materials systems, from structural alloys to pharmaceutical formulations.

In molecular dynamics (MD), the calculation of stress-strain curves provides a critical bridge between atomistic simulations and continuum material properties. This process allows researchers to predict macroscopic mechanical behavior, such as Young's modulus and yield strain, directly from the interactions and motions of atoms. The core of this methodology involves carefully applying engineering strain to a simulated system and calculating the resulting stress tensor from atomic forces and velocities [8]. These calculations are fundamental to materials science, drug development (e.g., characterizing polymeric carriers), and the design of micro/nano-electromechanical systems [8]. This guide details the protocols for performing these calculations accurately, addressing common challenges such as finite-size effects, deformation rate artifacts, and the proper treatment of virial stress in periodic systems.

Foundational Concepts

Engineering Strain

Engineering strain (ε) is a dimensionless measure of deformation representing the displacement between particles in a material relative to an original reference length. In MD simulations, it is typically defined as: ε = (Lt - L0) / L0] where L0 is the initial box length in the deformation direction, and Lt is the instantaneous length at time t [9]. For quasi-two-dimensional materials like membranes or graphene, the definition of L0 and the volume can be ambiguous and often requires correction [10].

The Stress Tensor in Molecular Dynamics

The stress tensor (σ) in MD is not a single value but a 3x3 matrix that describes the state of stress at a point. The total stress tensor consists of two primary components: a kinetic (ideal gas) part due to atomic motion and a virial (configurational) part due to interatomic forces [11] [12].

The total stress tensor is calculated as [11]: σαβ = [Wαβ + Σi miviαviβ] / V

Where:

- Wαβ is the virial tensor.

- mi is the mass of atom i.

- viα and viβ are the velocity components of atom i.

- V is the system volume.

The virial tensor W is a sum over atomic virials. For a system where Newton's third law is obeyed, the atomic virial can be computed as [11]: Wi = -(1/2) Σj≠i rij ⊗ Fij]

Where rij is the position vector between atoms i and j, and Fij is the force on atom i due to atom j. This formulation is valid for small deformations and low temperatures where thermal vibrations are negligible [8]. For polarizable force fields, the derivation of the internal stress tensor must account for induced dipoles and their dependence on system shape [13].

Young's Modulus

Young's modulus (E) is the slope of the initial linear (elastic) region of the stress-strain curve, defined by Hooke's law: σ = E ⋅ ε

In MD, it is calculated as the derivative of stress with respect to applied strain [9] [10]. For disordered materials, the choice of method for determining E significantly impacts the result, with stress-strain methods generally being more reliable than energy-scaling approaches [10].

Computational Protocols

Workflow for Stress-Strain Curve Calculation

The following diagram illustrates the general workflow for performing a deformation simulation and calculating a stress-strain curve in MD.

Protocol 1: Continuous Deformation (Strain-Ramp) Simulation

This protocol mimics a macroscopic tensile test and is widely used for polymers and crystalline materials [14].

- Step 1: System Preparation. Generate an initial atomic structure and equilibrate it thoroughly at the target temperature and pressure (e.g., 300 K, 1 atm) using an NPT ensemble. This ensures the system is in a stable, representative state before deformation begins [14].

- Step 2: Apply Uniaxial Strain. Choose a deformation direction (e.g., z-axis). At each deformation step, increase the simulation box length in that direction by a small factor (ΔL). Use a slow, quasi-static deformation velocity (e.g., 1×10⁻⁴ nm/ps) to approximate static conditions and avoid rate-dependent artifacts [9].

- Step 3: Control Transverse Stresses. To account for the Poisson effect (lateral contraction upon axial stretching), use a semi-isotropic or anisotropic barostat (e.g., Parrinello-Rahman) in the non-deforming directions. This allows the box dimensions perpendicular to the strain axis to relax, maintaining a target stress (often zero) in those directions [9] [12].

- Step 4: Calculate Stress. After each deformation and equilibration step, compute the components of the internal stress tensor. The relevant stress is typically the component in the deformation direction (e.g., σzz). In some software, this is reported as the negative of the pressure tensor component (σ = -Pz) [9].

- Step 5: Iterate and Construct Curve. Repeat Steps 2-4 until the desired maximum strain is reached. Plot the engineering stress (σ) against engineering strain (ε) to generate the stress-strain curve [14].

- Step 6: Extract Young's Modulus. Identify the initial linear region of the curve (e.g., 0.3% to 3% strain). Perform a linear regression on this data; the slope is the Young's modulus [9].

Protocol 2: Deformation-Recovery for Yield Strain

This protocol is particularly effective for identifying the yield strain (εy) in crosslinked polymers and glasses, where stress-strain curves can be noisy [15].

- Step 1: Strain Incrementally. Starting from an equilibrated structure, apply a small, volume-conserving strain increment (Δε).

- Step 2: Equilibrate under NVT. Run a simulation in the NVT ensemble (constant Number of atoms, Volume, and Temperature) at the new strained configuration, allowing the stress to converge.

- Step 3: Save Structure. Save the atomic coordinates and box dimensions of the strained state.

- Step 4: Repeat. Return to Step 1, incrementing the total applied strain (ε) until a sufficient range is covered. This generates a series of saved structures at different strain levels.

- Step 5: Relax without Constraints. For each saved structure, perform an NPT simulation with zero applied external stress, allowing the system to fully relax.

- Step 6: Calculate Residual Strain. After relaxation, measure the new box dimensions. The residual strain (εr) is defined as the strain that remains after the applied stress is released. It can be calculated using the formula [15]: εr = Σi=13 |(Li - ℓi) / Li| where Li and ℓi are the original and relaxed box lengths, respectively.

- Step 7: Determine Yield Strain. Plot the residual strain (εr) against the previously applied maximum engineering strain (ε). The yield strain εy is identified as the onset of permanent deformation, marked by a sharp transition of εr from zero to positive values [15].

Data Presentation and Analysis

Comparison of Methods for Young's Modulus Determination

The choice of method can lead to different results, especially for disordered materials.

| Method | Principle | Best For | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Continuous Deformation [14] | Direct simulation of a tensile test; slope of σ-ε curve. | Crystalline materials, ordered polymers. | Intuitive, replicates experiment. | Sensitive to deformation rate; can be noisy. |

| Deformation-Recovery [15] | Onset of permanent deformation from residual strain. | Crosslinked polymers, glasses (disordered systems). | Sharper yield signal; less sensitive to relaxation times. | Computationally more intensive. |

| Scaling Approach [10] | Curvature of potential energy with respect to scaling factor: E = (1/V0) (∂²U/∂α²) | Low-temperature, crystalline systems. | No explicit dynamics needed. | Not suitable for finite-temperature properties; fails for complex/disordered bonds [10]. |

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Components for MD Mechanical Testing

A successful simulation relies on the appropriate selection of computational tools and parameters.

| Item | Function | Examples & Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Force Field | Describes interatomic potentials. | OPLS-AA (polymers, organics) [14], EDIP (carbon systems) [10]. Must be validated for the target material. |

| MD Engine | Software that performs the simulation. | LAMMPS [10] [14], GROMACS [9], AMBER [13]. |

| Barostat | Controls pressure/stress in non-deforming directions. | Parrinello-Rahman (allows shape change, preferred for anisotropic stress) [12], Berendsen (simple scaling, isotropic only) [12]. |

| Stress Compute | Command to calculate the stress tensor. | In LAMMPS: compute stress/atom or compute pressure [16]. The virial formulation must be consistent with the force field [11]. |

| Deformation Algorithm | How the box is strained. | fix deform (LAMMPS), change_box (LAMMPS with remap) [10]. Use deform-init-flow in GROMACS to update velocities during deformation [9]. |

Advanced Considerations and Troubleshooting

Special Cases and System-Specific Advice

- Quasi-2D Materials (Graphene, Membranes): The volume (V) is ambiguous. Use corrections by constructing a surface mesh (e.g., in OVITO) or by calculating the density profile to define an effective thickness. The reported Young's modulus is highly sensitive to this volume definition [10].

- Polarizable Force Fields: The stress tensor derivation must include contributions from the polarization energy and the dependence of induced dipoles on the simulation box shape and size [13].

- Free Surfaces: The virial stress definition is consistent with traction-free boundary conditions near surfaces, unlike some other stress definitions [8].

Troubleshooting Common Issues

- Young's modulus is too low/high: Verify the force field is parameterized and validated for mechanical properties [14]. Ensure the deformation rate is sufficiently slow for the system to equilibrate internally at each step [9].

- Excessive noise in stress-strain curve: Increase the sampling time at each strain step for better averaging. For yield strain determination, consider switching to the deformation-recovery method, which provides a sharper transition [15].

- Non-physical system behavior during deformation: When using periodic boundary conditions, ensure that options like

remap(LAMMPS) ordeform-init-flow(GROMACS) are used to correctly update atomic coordinates and velocities as the box deforms [9] [10].

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation has emerged as a pivotal tool for investigating the mechanical properties of materials at the atomic scale, providing insights not readily accessible through experimental methods [17]. This application note details protocols for calculating stress-strain curves and analyzing key mechanical properties—yield strength, plastic deformation, and fracture—within MD simulations. The guidance is framed within the context of a broader thesis on extracting quantitative mechanical data from atomic-scale simulations, with specific examples from metallic and ceramic systems [18] [19] [17]. We present standardized methodologies to ensure researchers obtain reliable, reproducible results that accurately capture material behavior under mechanical loading.

Theoretical Foundation of Stress-Strain Analysis in MD

In MD simulations, stress is typically calculated using the virial theorem, which accounts for both kinetic energy contributions from atomic velocities and potential energy contributions from interatomic forces. The virial stress formula for a multicomponent system is given by:

[ \sigma{ij} = \frac{1}{V} \left[ \sum{\alpha} -m^{\alpha}vi^{\alpha}vj^{\alpha} + \frac{1}{2} \sum{\alpha, \beta \neq \alpha} ri^{\alpha\beta}F_j^{\alpha\beta} \right] ]

where (V) is the volume of the simulation cell, (m^{\alpha}) is the mass of atom (\alpha), (vi^{\alpha}) is the velocity component, (ri^{\alpha\beta}) is the distance between atoms (\alpha) and (\beta), and (F_j^{\alpha\beta}) is the force component [17].

Strain is computed from the deformation of the simulation cell boundaries. For uniaxial tension, the engineering strain along the loading direction (e.g., x-direction) is calculated as:

[ \varepsilon{xx} = \frac{Lx - Lx^0}{Lx^0} ]

where (Lx^0) is the initial length and (Lx) is the instantaneous length during deformation.

The accurate computation of these quantities forms the basis for constructing stress-strain curves, from which yield strength, plastic deformation mechanisms, and fracture points can be extracted.

Computational Protocols

System Preparation and Equilibration

- Initial Structure Generation: Create an atomistic model of the material with appropriate crystallographic orientation. For single crystals, this involves defining the unit cell and replicating it in three dimensions [19]. For composite systems, such as Ni/graphene, carefully position the constituent phases to represent the desired morphology [17].

- Energy Minimization: Use conjugate gradient or steepest descent algorithms to relax the initial structure to its local energy minimum, eliminating unrealistic atomic overlaps and high-energy configurations.

- Thermal Equilibration: Employ an appropriate thermostat (e.g., Nose-Hoover or Berendsen) to bring the system to the target temperature (e.g., 300 K) and maintain it for a sufficient duration (e.g., 20-50 ps) in an NVT ensemble (constant Number of particles, Volume, and Temperature). This establishes the realistic atomic velocities and configurations for the subsequent deformation simulation [17].

Deformation Simulation Setup

Two primary methodologies are employed for applying deformation in MD simulations:

- Dynamic Tension/Compression: Continuously deform the simulation cell at a constant strain rate by applying a velocity to the boundary atoms or by resizing the simulation cell dimensions at each time step [19] [17].

- Incremental (Step-wise) Loading: Apply small strain increments (e.g., 0.25-1.0%) followed by a relaxation period at constant strain. This approach more closely approximates quasi-static loading conditions and allows the system to relax between deformation steps [17].

Table 1: Comparison of Deformation Methodologies in MD Simulations

| Feature | Dynamic Tension | Incremental Loading |

|---|---|---|

| Implementation | Continuous cell scaling | Strain steps with relaxation |

| Computational Cost | Generally lower | Higher due to relaxation steps |

| Approximation to Quasi-Static | Less accurate | More accurate |

| Strain Rate Control | Directly controlled | Effective strain rate depends on step size and relaxation time |

| Suitability | High strain-rate studies, large systems | Theoretical strength, equilibrium properties |

Critical Simulation Parameters

The following parameters significantly influence the results of mechanical properties simulations and must be carefully selected:

- Strain Rate: MD simulations typically use strain rates orders of magnitude higher ((10^7)-(10^{10}) s⁻¹) than experiments due to computational constraints. Studies show that lower strain rates ((5 \times 10^{-4}) fs⁻¹) may result in lower critical strain values compared to higher rates ((5 \times 10^{-3}) fs⁻¹) [17]. The strain rate sensitivity must be considered when interpreting results.

- Temperature Control: Temperature significantly affects mechanical response. Simulations at cryogenic temperatures (e.g., 0 K) yield higher ultimate tensile strength values closer to the theoretical strength, while room temperature simulations (300 K) show reduced strength and earlier onset of plasticity due to enhanced thermal activation of dislocation nucleation and motion [19] [17].

- Boundary Conditions: Periodic boundary conditions are commonly applied to simulate an infinite crystal, but careful attention must be paid to image interactions. For non-periodic systems, fixed boundary layers are often used to apply the deformation, while allowing free movement of atoms in the interior region.

- Time Step: The integration time step must be short enough to capture the highest frequency atomic vibrations (typically 0.1-2.0 fs for metals and ceramics).

Analysis of Critical Points on the Stress-Strain Curve

Identifying Yield Strength

The yield strength marks the transition from elastic to plastic deformation. In MD simulations, it can be identified through several complementary methods:

- Proportional Limit Method: The point where the stress-strain curve first deviates from linearity.

- Offset Method (e.g., 0.2% Strain): The stress at which the curve intersects a line parallel to the elastic region but offset by a specified plastic strain (challenging in MD due to discrete data).

- Onset of Plasticity Indicators: A more reliable approach in MD involves correlating the stress with the emergence of permanent structural changes:

- Dislocation Nucleation: The first appearance of dislocations, detectable using techniques like Common Neighbor Analysis (CNA) or Dislocation Analysis (DXA) [19].

- Phase Transformations: In materials like SiC, the onset of crystal-to-amorphous transformation can signify yielding [18].

- Irreversible Volume Change: Deviation from the linear relationship between volume change and applied strain.

Characterizing Plastic Deformation

The plastic regime is characterized by irreversible structural changes and dissipation of energy. Key analysis techniques include:

- Dislocation Density Evolution: Track the length of dislocation lines per unit volume over time. Variations in dislocation density directly correlate with features in the stress-strain curve, such as strain hardening and softening [19].

- Slip Band Formation and Propagation: Visualize the development and extension of slip bands, which are planes of intense plastic slip. In 4H-SiC, for example, slip band extension in the later stages of plastic deformation was identified as the direct cause of crack initiation [18].

- Analysis of Amorphization: For brittle materials like SiC, plastic deformation often occurs via amorphization rather than dislocation-mediated slip. The volume fraction of the amorphous phase can be quantified using CNA [18].

Determining Fracture Point

Fracture represents the final loss of structural integrity. In MD, it is identified by:

- Stress Drop: A sudden, significant decrease in the stress-strain curve, often to near zero, indicates complete failure of the material [20].

- Crack Initiation and Propagation: Visual inspection of atomic configurations reveals the nucleation and growth of voids and cracks. Stress analysis demonstrates that the maximum principal stress at the crack tip drives propagation, with the direction depending on the direction of this stress [18].

- Atomic Coordination Analysis: A sharp change in the average coordination number of atoms signifies bond breaking and material separation.

Table 2: Key Analysis Techniques for Critical Points in MD Stress-Strain Curves

| Critical Point | Primary Identification Method | Supplementary Analysis Techniques | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yield Strength | Deviation from linear elasticity | Common Neighbor Analysis (CNA), Dislocation Analysis (DXA) | First nucleation of dislocations in Cu nano-beams [19] |

| Plastic Deformation | Plateau or hardening in stress-strain curve | Dislocation density calculation, Slip vector analysis, Amorphization volume | Slip band extension leading to crack initiation in 4H-SiC [18] |

| Fracture Point | Sudden stress drop to near-zero | Visual tracking of crack propagation, Radial Distribution Function (RDF) | Chain snapping in polyacetylene, reducing stress to zero [20] |

Case Study: Tensile Loading of Nanosized Cu Beams

A systematic investigation of nanosized, single-crystal Cu beams provides a clear example of the above protocols [19]. The study examined the influence of strain rate, temperature, and crystallographic orientation ([100], [110], [111]).

- Simulation Setup: Defect-free Cu beams of square cross-section were subjected to displacement-controlled tensile loading using MD with an embedded atom method (EAM) potential.

- Strain Rate Effect: An increasing strain rate showed only a small influence on the stress-strain curves but significantly affected the development of plasticity, both in terms of its spread and initiation point [19].

- Temperature Effect: An increase in temperature led to lower strain and stress at plastic initiation, as well as reduced stiffness, highlighting the importance of thermal effects on mechanical properties.

- Dislocation Correlation: The variation in dislocation density was directly correlated with variations in the stress-strain curve, providing a microstructural explanation for the macroscopic mechanical response.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Software for MD Simulations of Mechanical Properties

| Item/Reagent | Function/Application | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Interatomic Potentials | Defines the forces between atoms. Critical for accuracy. | EAM potentials for metals (Cu, Ni [19] [17]), Tersoff/REAXFF for ceramics/covalent systems (SiC [18], CHO [20]) |

| MD Simulation Software | Engine for performing the calculations. | LAMMPS, GROMACS, AMS (as used in [20]) |

| Visualization & Analysis Tools | For post-processing trajectory data and quantifying results. | OVITO, VMD, AMSmovie [20] |

| Structure Generation Tools | Creates initial atomic configurations. | Packmol, ASE, built-in builders in MD packages |

| Analysis Scripts (Python) | Custom scripts for extracting specific metrics (e.g., stress, dislocation density). | PLAMS library used to extract stress-strain data [20] |

Workflow Visualization

Diagram 1: MD Simulation Workflow for Stress-Strain Analysis. This diagram outlines the key steps in a molecular dynamics simulation for calculating mechanical properties, highlighting the iterative deformation-computation loop.

Diagram 2: Correlation of Macroscopic Curve Features with Atomic-Scale Events. This diagram maps the critical points on a stress-strain curve to the underlying atomic-scale deformation mechanisms observed in MD simulations.

This application note has detailed the protocols for simulating and analyzing the critical points on stress-strain curves using molecular dynamics. From system preparation and equilibration to the identification of yield strength, characterization of plastic deformation, and determination of the fracture point, each step requires careful attention to parameters such as strain rate, temperature, and appropriate analysis techniques. The case studies on Cu nano-beams, Ni/graphene composites, and 4H-SiC illustrate the practical application of these protocols. By adhering to these standardized methodologies, researchers can ensure the acquisition of reliable, mechanistically insightful data on material mechanical properties, thereby enhancing the predictive power of molecular dynamics simulations in materials science and engineering.

The mechanical behavior of materials diverges significantly between the nanoscale and macroscopic regimes due to the increasing dominance of surface and interfacial effects as dimensions shrink. Understanding these differences is critical for interpreting data from computational methods like Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations and translating nanoscale findings to macroscopic applications. MD simulations serve as a computational microscope, providing atomic-level insights into deformation mechanisms that are often inaccessible experimentally [21]. This article details the protocols for calculating stress-strain curves using MD, framed within a broader thesis on how size effects govern mechanical properties from atoms to bulk materials.

Theoretical Foundation: Core Concepts and Divergence

At the heart of the divergence between nanoscale and macroscopic mechanics are the relative influences of surface atoms and discrete defects. In macroscopic samples, the bulk material's behavior averages out these atomic-scale fluctuations, and deformation is typically governed by the statistics of many pre-existing defects, such as dislocations. The material's response can often be treated as a continuum. In contrast, at the nanoscale, the high surface-to-volume ratio means the energy and structure of surface atoms play a disproportionately large role in mechanical response [22]. Furthermore, plastic deformation is often initiated by the nucleation of the first defect, a discrete and stochastic event, rather than the motion of existing ones.

Key Conceptual Differences: The table below summarizes the fundamental differences that underlie the distinct mechanical behaviors observed at different scales.

Table 1: Fundamental Differences Between Nanoscale and Macroscopic Mechanical Behavior

| Aspect | Nanoscale Regime | Macroscopic Regime |

|---|---|---|

| Governing Principles | Discrete atomic interactions, stochasticity | Continuum mechanics, statistical averages |

| Surface-to-Volume Ratio | Very high; surface energy dominates [22] | Very low; bulk energy dominates |

| Defect Mechanics | Nucleation-controlled (stochastic) [21] | Propagation-controlled (more predictable) |

| Material Strength | Often approaches theoretical maximum | Limited by pre-existing defects |

| Size Effect | Mechanical properties are strongly size-dependent | Properties are treated as intrinsic constants |

The following diagram illustrates the conceptual framework for how these scale-dependent factors integrate within an MD simulation workflow to produce a stress-strain curve.

Quantitative Data Comparison

The theoretical differences manifest as quantifiable discrepancies in measured mechanical properties. The table below provides a comparative summary of key properties, highlighting the dramatic influence of scale.

Table 2: Comparative Summary of Mechanical Properties at Different Scales

| Property | Nanoscale (MD Simulation) | Macroscopic (Experiment) | Primary Reason for Discrepancy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Young's Modulus | Can be higher or lower | Bulk value | Surface stress effects, different loading conditions [21] |

| Yield Strength | Approaches theoretical strength (~G/10) [21] | 2-3 orders of magnitude lower | Absence of stress-concentrating defects in pristine simulation volume |

| Fracture Behavior | Often brittle fracture; clean separation | Ductile tearing or complex crack propagation | Limited system size restricts plastic zone ahead of crack tip |

| Stress-Strain Curve | Significant noise; stochastic yielding [20] | Smooth curve after elastic region | Thermal fluctuations and limited sampling of defect nucleation events |

Protocols for MD Stress-Strain Calculations

This section provides a detailed, step-by-step protocol for calculating stress-strain curves via Molecular Dynamics, incorporating critical considerations for accurately modeling nanoscale phenomena.

Protocol 1: Standard Tensional Deformation

Objective: To simulate the uniaxial tensile deformation of a nanoscale material and compute the resulting stress-strain curve up to the point of fracture.

Materials & Reagents:

- Initial Atomic Structure: A data file containing the initial coordinates of all atoms (e.g., in .xyz, .pdb, or LAMMPS-data format) [21].

- Interatomic Potential: A parameterized force field file (e.g., CHO.ff for organic polymers [20], IFF-R for reactive simulations [23], or other relevant potentials).

- MD Software: A molecular dynamics package such as LAMMPS, AMS, or GROMACS.

Procedure:

- System Preparation: Import the initial atomic structure into the MD software. Apply periodic boundary conditions (PBCs) as needed to minimize surface effects or to model a bulk material [22].

- Energy Minimization: Run an energy minimization algorithm (e.g., conjugate gradient) to relax the structure to its nearest local energy minimum, removing any unrealistic atomic overlaps or high-energy configurations.

- Equilibration: Perform an MD simulation in the NPT (constant Number of particles, Pressure, and Temperature) or NVT (constant Number, Volume, and Temperature) ensemble for a sufficient duration (e.g., 100-500 ps) to equilibrate the system at the desired temperature (e.g., 300 K) and pressure. This ensures the system is in a thermally stable state before deformation.

- Deformation Setup: a. Define the direction of tensile strain (e.g., the y-axis). b. Set the strain rate, a critical parameter. A common approach is to use a high strain rate (e.g., 0.00002 Å/fs [20]) due to computational limits, but this should be acknowledged as a source of discrepancy with experiment. c. Set the deformation frequency, which determines how often the simulation cell is stretched (e.g., every 10-100 time steps).

- Deformation Run: Conduct the MD simulation while applying the deformations. At each sampling step, the software automatically calculates the internal stress tensor using the virial theorem, which relates the atomic velocities and forces to the macroscopic pressure [20].

- Data Collection: The simulation outputs a trajectory file containing the atomic positions and the stress tensor components (e.g.,

stress_yyfor the tensile stress) at various strain values. The engineering strain is tracked by the change in simulation box length.

The workflow for this protocol, including the critical step of applying a reactive potential for fracture studies, is summarized below.

Protocol 2: Analyzing the Stress-Strain Curve

Objective: To process the raw MD output to generate a stress-strain curve and extract key mechanical properties.

Procedure:

- Data Parsing: Extract the relevant stress and strain data from the simulation output files. For uniaxial tension, this is typically the

stress_yycomponent plotted against thestrain_yvalue [20]. - Curve Generation: Plot the stress versus strain to generate the curve. The initial, linear portion of the curve defines the elastic region.

- Young's Modulus Calculation: Perform a linear regression analysis on the linear elastic region of the curve. The slope of this line is the Young's Modulus [21].

- Yield Strength Identification: Identify the yield point, which is the stress at which the curve first deviates from linearity by a defined amount (e.g., 0.2% strain offset) or where the stress reaches a maximum before dropping. This marks the onset of plastic deformation.

- Fracture Point Identification: Identify the point of ultimate tensile strength (the highest stress on the curve) and the fracture point (where the stress drops catastrophically to near zero, indicating complete material separation) [20].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details key computational "reagents" and tools essential for conducting MD simulations of mechanical properties.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for MD Stress-Strain Analysis

| Item Name | Function / Description | Example Sources/Forms |

|---|---|---|

| Interatomic Potentials | Mathematical functions describing the energy of atomic interactions; the core of any MD simulation. | Harmonic (IFF, CHARMM): For elastic deformation.Morse (IFF-R): For bond breaking and fracture [23].REBO/ReaxFF: For complex chemical reactions. |

| Initial Structure Databases | Sources of experimentally determined or predicted atomic structures for simulation setup. | Materials Project, AFLOW (inorganic crystals).Protein Data Bank (PDB) (biomolecules).PubChem (small molecules) [21]. |

| Molecular Dynamics Engines | Software that performs the numerical integration of Newton's equations of motion for the atomic system. | LAMMPS, GROMACS, AMS [20], NAMD. |

| Visualization & Analysis Tools | Software for visualizing atomic trajectories and analyzing simulation data. | OVITO, VMD, AMSmovie [20], PyMOL, MDAnalysis. |

| Thermostats/Barostats | Algorithms to control temperature (e.g., Nose-Hoover - NHC [20]) and pressure during equilibration and simulation. | Essential for simulating realistic experimental conditions (NPT, NVT ensembles). |

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations have emerged as a powerful tool for probing the mechanical behavior of materials at the atomic and molecular scales. For biomaterials and drug delivery systems, understanding mechanical properties through stress-strain prediction is not merely an academic exercise but a critical component in rational design and development. Stress-strain curves derived from MD simulations provide fundamental insights into material strength, elasticity, ductility, and failure mechanisms under physiological conditions—parameters that directly influence device functionality and therapeutic efficacy.

This application note details how MD simulations can predict the stress-strain behavior of biomaterials, using fibrin fibers in blood clots as a primary case study. We provide a validated computational protocol, summarize key quantitative findings in structured tables, and illustrate the workflow and molecular composition of the system through specialized diagrams. This framework empowers researchers to translate simulation data into design principles for advanced biomaterials and drug delivery systems.

A Case Study: Predicting the Mechanical Behavior of Fibrin Fibers

Blood clots perform the critical mechanical task of stemming blood flow after vascular injury. The mechanical backbone of clots is a mesh of fibrin fibers, which are remarkably extensible and elastic, capable of stretching to over 200% of their original length before rupture [24]. The origin of this exceptional elasticity has been a subject of scientific debate, with proposed mechanisms including the unfolding of α-helical coiled-coils, γ-nodules, and the α-C region of the fibrinogen molecule.

A groundbreaking MD simulation study developed a three-component model that successfully captures the experimentally determined stress-strain behavior of single fibrin fibers [24]. This model dissects the fibrinogen molecule into:

- The folded fibrinogen core (as seen in the crystal structure)

- The unstructured α-C connector

- The partially folded α-C domain

Steered molecular dynamics (SMD) simulations were performed on the folded core and the α-C domain, while a wormlike chain model was used for the α-C connector. The results demonstrated that the α-C domains are a crucial contributor to the fibrin fiber's stress-strain behavior, particularly its strain-hardening characteristic where the modulus increases by a factor of 2-3 when strained beyond twice its original length [24]. This exemplifies how MD simulations can deconstruct complex biomechanical behavior into the contributions of specific molecular domains.

The table below summarizes key mechanical parameters for fibrin fibers, obtained from both MD simulations and experimental validation.

Table 1: Mechanical Properties of Fibrin Fibers from Simulation and Experiment

| Property | Value from MD Simulation/Model | Experimental Reference Value (AFM) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Young's Modulus | Model successfully reproduced experimental values | ~10 MPa [24] | Modulus increases with strain (strain hardening) |

| Breaking Strain | Model captured full stress-strain curve | >200% for un-cross-linked fibers [24] | Extraordinary extensibility |

| Persistence Length of α-C Connector | 0.8 nm (Kuhn length = 1.6 nm) [24] | N/A | Parameter used in the Wormlike Chain model for the unstructured region |

| SMD Pulling Velocity | 0.025 Å/ps [24] | N/A | Velocity used in steered MD simulations of core and domain |

The following table outlines the core components of the molecular model and their functions, which can be considered the essential "research reagents" for in silico studies of this nature.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions: Key Components of the Fibrin Model

| Component / "Reagent" | Description / Source | Function in the Simulation |

|---|---|---|

| Fibrinogen Core Structure | Protein Data Bank (e.g., crystal structure of fibrinogen) [25] | Provides the atomic coordinates for the structured, folded core of the molecule. |

| α-C Domain Structure | Protein Data Bank (e.g., PDB: 2BAF for bovine α-C domain) [24] | Provides the atomic coordinates for the partially folded C-terminal domain. |

| α-C Connector Model | Wormlike Chain Model [24] | Represents the mechanical behavior of the unstructured, flexible polypeptide linker. |

| Molecular Force Field | e.g., ffG53A7 in GROMACS [25] | Defines the empirical parameters for bonded and non-bonded interatomic forces. |

| Solvation Box | Explicit water molecules (e.g., SPC/E model) [25] | Mimics the physiological aqueous environment for the protein. |

| Counter Ions | e.g., Na⁺, Cl⁻ ions [25] | Added to neutralize the system's net charge, ensuring physical correctness. |

Experimental Protocol: MD Simulation for Stress-Strain Prediction

This protocol outlines the key steps for obtaining stress-strain data from MD simulations, based on established methodologies [24] [25] [26].

A. System Setup

- Obtain Protein Coordinates: Download the initial atomic coordinates of your protein of interest (e.g., fibrinogen) from the RCSB Protein Data Bank (http://www.rcsb.org/) [25].

- Generate Topology and Coordinates: Use a tool like

pdb2gmxin GROMACS to convert the PDB file into the software's format (.gro) and generate a molecular topology file (.top). This step adds hydrogen atoms and assigns a force field. - Define the Simulation Box: Place the protein in a periodic box (e.g., cubic, dodecahedron) with a defined distance (e.g., 1.0 nm) from the box edge to avoid spurious self-interactions.

- Solvate the System: Fill the box with explicit water molecules to mimic an aqueous environment using the

solvatecommand. The topology file is automatically updated to include water. - Neutralize the System: Add ions (e.g., Na⁺, Cl⁻) to neutralize the net charge of the system using the

geniontool. This is a critical step for simulation stability.

B. Energy Minimization and Equilibration

- Energy Minimization: Run an energy minimization (e.g., using the steepest descent algorithm) to remove any steric clashes or unrealistic geometry in the initial structure [27].

- Equilibration: Equilibrate the system in stages to reach the desired thermodynamic state (e.g., 300 K, 1 bar).

- NVT Ensemble: Equilibrate the temperature for ~25-100 ps.

- NPT Ensemble: Equilibrate the pressure for ~25-100 ps.

C. Production Run and Mechanical Testing

- Uniaxial Deformation: Apply a constant velocity (strain rate) to the simulation box in one direction while maintaining zero pressure in the perpendicular directions [24] [27]. This is typically done by scaling the atomic coordinates and box dimensions.

- Control Parameters:

- Strain Rate: Due to computational limits, MD simulations use high strain rates (e.g., 0.004 - 0.012 ps⁻¹). The results should be interpreted with this limitation in mind [27].

- Temperature: Use a thermostat (e.g., Nosé-Hoover) to maintain the target temperature (e.g., 300 K) during deformation.

- Duration: Run the simulation until the fiber or structure undergoes full rupture to capture the entire stress-strain curve to failure.

D. Data Analysis

- Stress Calculation: The stress (force per unit area) is typically calculated from the internal pressure tensor of the simulation box, which is a standard output of MD software like LAMMPS or GROMACS.

- Strain Calculation: The engineering strain is calculated as

ε = (L - L₀) / L₀, whereLis the instantaneous box length andL₀is the initial length. - Generate Stress-Strain Curve: Plot the stress against strain to obtain the characteristic mechanical response curve.

Workflow and System Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the sequential workflow for performing steered molecular dynamics simulations to obtain a stress-strain curve, as described in the protocol.

Diagram 1: MD Stress-Strain Workflow

This diagram provides a simplified representation of the key molecular components in a fibrin fiber and their response to mechanical stress, based on the three-element model.

Diagram 2: Fibrin Molecular Mechanics Model

Application to Drug Delivery Systems and Biomaterials

The principles and techniques demonstrated for fibrin fibers can be directly applied to the design and optimization of drug delivery systems and other biomaterials.

- Polymeric Nanoparticles and Hydrogels: MD simulations can predict the mechanical stability of polymeric drug carriers, which influences their circulation time, biodistribution, and cellular uptake. For hydrogels used in controlled drug release, stress-strain behavior dictates their swelling capacity and resistance to deformation under physiological loads [28].

- Targeted Drug Delivery: The binding affinity of targeting ligands on a nanoparticle's surface can be mechanically modulated. MD simulations can help understand how strain in a polymer tether affects ligand-receptor binding kinetics.

- Understanding Failure Mechanisms: By simulating stress-strain behavior to the point of failure, MD can identify molecular weak points in a biomaterial's structure. This allows for the rational design of more durable implants and delivery vehicles by reinforcing these vulnerable domains, perhaps through strategic cross-linking or the choice of more rigid molecular building blocks.

In conclusion, the ability of MD simulations to predict stress-strain relationships at the molecular level provides an indispensable tool for the bottom-up design of next-generation biomaterials and drug delivery systems, reducing the need for costly and time-consuming empirical trial-and-error in the lab.

Practical Implementation: Step-by-Step Protocols for Stress-Strain Calculations

Calculating stress-strain curves from molecular dynamics (MD) simulations is a fundamental technique for predicting the mechanical properties and failure mechanisms of materials across atomic, meso, and continuum scales. The selection of appropriate simulation software, which dictates the available force fields, analysis tools, and computational efficiency, is a critical first step in such investigations. This application note provides a structured comparison of three prominent MD packages—LAMMPS, GROMACS, and QuantumATK—framed within the context of generating stress-strain data. We detail their specific capabilities, provide validated protocols for stress-strain curve calculation, and visualize the associated workflows to equip researchers with the knowledge to select the optimal tool for their material system.

Software Capabilities and Comparison

The core features of LAMMPS, GROMACS, and QuantumATK are summarized in the table below, highlighting their applicability for stress-strain simulations.

Table 1: Software comparison for stress-strain calculations in molecular dynamics.

| Feature | LAMMPS | GROMACS | QuantumATK |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Classical MD for atomic, meso, and continuum scales [29] | High-performance MD, strong in biomolecules [30] | Atomistic simulation with ab initio and force fields [31] [32] [33] |

| Interatomic Potentials | Extremely wide variety: pairwise, many-body (EAM, Tersoff), reactive (ReaxFF), ML potentials (SNAP, RANN) [34] [35] | Strong support for biomolecular force fields (AMBER, CHARMM, OPLS-AA) [30] [36] | Wide range: Lennard-Jones, Tersoff, REBO, EAM, MEAM, ReaxFF, ML force fields [33] |

| Stress-Strain Deformation | Built-in 'fix deform'/'fix npt' for uniaxial/triclinic strain; extensive thermo/stat output [34] | Requires custom parameterization via 'define_strain.m4' or external tools [30] | Specialized 'StrainConfigurationHook' for easy application of uniaxial/shear strain during MD [31] |

| Key Strength | Unmatched flexibility, model variety, and scalability for complex/inorganic systems [34] [29] | Exceptional performance and optimization for (bio)polymer systems in solution [30] [36] | Seamless integration from classical MD to quantum-accurate forces for nanomaterials [31] [33] |

| System Type | Polymers, metals, ceramics, granular materials, coarse-grained models [34] | Proteins, lipids, nucleic acids, polymers in implicit/explicit solvent [30] | Nanostructures, 2D materials, surfaces, interfaces, doped semiconductors [31] [33] |

Experimental Protocols for Stress-Strain Curve Calculation

Protocol 1: Calculating Young's Modulus with QuantumATK

This protocol uses the specialized StrainConfigurationHook in QuantumATK to perform a tensile test and extract Young's Modulus, ideal for nanoscale and low-dimensional materials [31].

- System Preparation: Construct or import the initial atomic configuration (e.g., a bulk crystal, nanowire, or 2D sheet). Assign an appropriate classical or machine-learned force field [33].

- Hook Definition: Define the strain hook to apply uniaxial strain along the desired Cartesian direction (e.g., 'x').

- MD Simulation Setup: Configure an NVT (constant number, volume, and temperature) MD simulation. Pass the

strain_hookto thepre_step_hookargument. Set up a measurement hook to record stress and strain at every step or a defined interval [31]. - Simulation Execution: Run the simulation. The hook automatically deforms the simulation cell and records the data.

- Data Analysis: After the simulation, extract the stress and strain data from the trajectory object. Perform a linear fit on the initial, elastic portion of the stress-strain curve. The slope of this fit is the Young's Modulus [31].

Protocol 2: Uniaxial Tensile Test with LAMMPS

This general-purpose protocol leverages LAMMPS' flexibility for simulating the deformation of a wide range of materials, including polymers and metals [34].

- System Construction: Create a bulk material sample using the

latticeandregioncommands. Use thecreate_atomscommand to populate the region. Assign a potential using thepair_styleandpair_coeffcommands [34]. - Equilibration: Minimize the system energy and run an NPT (constant number, pressure, and temperature) simulation to equilibrate the system at the target temperature and zero pressure for a sufficient duration (e.g., 100-500 ps).

- Deformation Simulation: Switch to an NVT ensemble and use the

fix deformcommand to apply a constant strain rate. Theunits boxoption ensures the engineering strain is computed relative to the initial box size. Set athermooutput frequency to record global stress values. - Data Collection: Use the

thermo_style customcommand to output the Lagrangian strain (etrueoreng) and the corresponding stress component (e.g.,pxxfor stress in the x-direction) at regular intervals. - Post-Processing: Plot the stress component against the strain to generate the stress-strain curve. The yield strength can be identified as the point where the curve deviates from linearity, and the ultimate tensile strength is the maximum stress value.

Critical Validation and Comparison Steps

- Force Field Consistency: When comparing results between packages (e.g., LAMMPS and GROMACS), ensure force field parameters, including 1-2, 1-3, and 1-4 neighbor exclusions (

special_bondsin LAMMPS,fudgeLJin GROMACS), are identical [30]. - Energy Validation: For a single configuration, compare potential energies and forces between different engines after accounting for unit conversions and different values of Coulomb's constant to ensure model equivalence [36].

- NVE Validation: As a debugging step, run short simulations in the NVE ensemble in both packages to verify that forces and basic dynamics are comparable before introducing thermostating and deformation [30].

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the general decision-making workflow and the specific computational process for conducting a stress-strain simulation.

Diagram 1: Software selection workflow.

Diagram 2: Generic simulation protocol.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Essential research reagents and computational tools for stress-strain MD simulations.

| Tool / Reagent | Function / Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Reactive Potentials (IFF-R, ReaxFF) | Enable bond breaking and formation during deformation for studying fracture and chemical reactions under stress [35]. | Simulating failure of polymers or crack propagation in ceramics. |

| Machine Learning Potentials (MTP, SNAP) | Provide near-quantum accuracy at a fraction of the computational cost for studying complex or multi-element materials [33]. | Calculating mechanical properties of amorphous carbon or multi-principal element alloys. |

| InterMol / ParmEd | Automated conversion tools for molecular topologies and force fields between different MD software formats [36]. | Ensuring force field consistency when validating a LAMMPS model against a GROMACS benchmark. |

| OVITO / PyL3dMD | Visualization and advanced trajectory analysis. PyL3dMD calculates over 2000 3D molecular descriptors from MD trajectories [37] [38]. | Visualizing dislocation dynamics; correlating mechanical properties with geometric descriptors via machine learning. |

| StrainConfigurationHook | A specialized function in QuantumATK to apply controlled strain along a specified direction during an MD simulation [31]. | Simplified setup for tensile tests of nanowires or 2D materials like graphene. |

The accurate calculation of stress-strain curves from molecular dynamics (MD) simulations is fundamentally dependent on the selection of an appropriate interatomic potential. These mathematical functions describe the potential energy of a system as a function of nuclear coordinates, thereby determining how atoms interact and respond to mechanical loads. For researchers investigating mechanical properties, the choice of potential dictates the reliability of predictions for properties such as elastic constants, yield strength, and fracture points. This application note provides a structured comparison of three widely used potential classes—Embedded Atom Method (EAM), Tersoff, and Reactive Potentials—focusing on their theoretical foundations, applicability to different material systems, and implementation protocols for simulating stress-strain response.

Theoretical Framework and Key Characteristics

Embedded Atom Method (EAM)

The Embedded Atom Method is a potent approach for metallic systems. Its core concept is that the energy of an atom embedded in a host solid depends on the electron density of the the host at the position of the atom. The total energy ( E_i ) of an atom ( i ) is given by:

- Energy Equation: ( Ei = F\alpha\left(\sum{j \neq i} \rho\beta(r{ij})\right) + \frac{1}{2}\sum{j \neq i} \phi{\alpha\beta}(r{ij}) ) [39] In this formulation, ( F\alpha ) is the embedding function representing the energy to embed atom ( i ) of type ( \alpha ) into the local electron density, ( \rho\beta ) is the electron density function from atom ( j ) of type ( \beta ) at the location of atom ( i ), and ( \phi_{\alpha\beta} ) is a pair-wise potential interaction. EAM is classified as a multi-body potential, making it particularly suitable for metals where bonding is strongly delocalized [39].

Tersoff and Bond-Order Potentials

Tersoff potentials belong to the class of bond-order potentials and are primarily designed for covalent materials like semiconductors, carbon, and silicon carbide. Their key feature is that the strength of a bond between two atoms depends on its local coordination environment.

- Bond-Order Concept: The potential energy incorporates a bond-order term that decreases with increasing coordination number of the involved atoms. This naturally captures the weakening of individual bonds in a highly coordinated environment. While highly effective for many covalent solids, some implementations of the Tersoff potential can exhibit unphysical strain-hardening behavior during tensile deformation, which has been addressed in modified versions [40].

Reactive Potentials

Reactive potentials are designed to simulate chemical reactions, including bond breaking and formation, within a classical MD framework. The two most prominent examples are the Reactive Force Field (ReaxFF) and the more recent Reactive INTERFACE Force Field (IFF-R).

- ReaxFF: This method uses Pauling's bond order concept to describe bond strength based on interatomic distances and the local chemical environment. It contains numerous energy terms (e.g., for over-coordination, conjugation, lone pairs) to accurately reproduce reaction energies and barriers from quantum mechanics, but this complexity increases computational cost [41] [23].

- IFF-R: This approach replaces harmonic bond potentials in classical force fields with reactive, energy-conserving Morse potentials. The Morse potential for a bond between atoms i and j is defined by three interpretable parameters: the equilibrium bond length (( ro )), the dissociation energy (( D{ij} )), and a parameter (( \alpha_{ij} )) that controls the width of the potential well. This method maintains the accuracy of non-reactive force fields while being about 30 times faster than ReaxFF for bond-breaking simulations [23].

Table 1: Comparative Overview of Interatomic Potentials for Mechanical Properties

| Potential Class | Theoretical Basis | Typical Parameter Count per Element/Bond | Computational Cost | Key Strengths | Primary Material Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EAM | Density-functional inspired | ~3-5 functions (F, ρ, φ) [39] | Low | Efficient for metals; captures metallic bonding | Pure metals, metallic alloys |

| Tersoff | Bond-order dependence | ~12-15 parameters [42] | Medium | Describes covalent bonding directionality | Semiconductors (Si, C), ceramics |

| ReaxFF | Bond-order & environment | >50 parameters & terms [23] | High | Enables complex chemical reactions | Combustion, catalysis, complex materials |

| IFF-R (Morse) | Morse potential replacement | 3 Morse parameters (De, r0, α) [23] | Medium (30x faster than ReaxFF) [23] | Interpretable parameters; enables bond breaking in standard force fields | Polymers, proteins, composites, failure analysis |

Application-Specific Selection and Performance

Performance for Stress-Strain and Fracture Simulations

The choice of potential directly impacts the accuracy of simulated mechanical properties. The following table summarizes key considerations and documented performance for each potential class.

Table 2: Performance in Stress-Strain and Fracture Simulations

| Potential Class | Representative Materials Studied | Fracture Strength Prediction | Typical System Size (Atoms) | Notable Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EAM | Metals (Cu, Ni, Fe, alloys) | Accurate for metallic yield, ductile failure | Millions | Not suitable for covalent/ceramic systems |

| Tersoff | Graphene, h-BN, silicon | Can overestimate strength; modified versions needed [40] | Hundreds of thousands | Unphysical strain-hardening in original forms [40] |

| ReaxFF | Polymers, fuels, oxides | Good for combined chemical/mechanical failure [41] | ~100,000 | High computational cost; parameter set dependence [41] [23] |

| IFF-R (Morse) | Carbon nanotubes, PAN, spider silk | Accurate failure stress & strain for polymers/CNTs [23] | Millions (due to speed) | Requires template methods for bond formation [23] |

Case Study: Modified Tersoff Potential for 2D Materials

The mechanical properties of a hexagonal BCN (h-BCN) monolayer were investigated using a modified Tersoff potential. The original Tersoff potential was found to predict unrealistically high fracture strength (110–211 GPa) and fracture strain (0.21–0.68). To address this, a modified cut-off scheme was implemented to eliminate unphysical strain-hardening behavior. With this modification, the predicted fracture strength of h-BCN fell to a reasonable range of 81.4–93.5 GPa, which is about 35% lower than that of graphene. This case highlights the critical importance of validating and potentially modifying potentials for specific material classes and loading conditions [40].

Case Study: IFF-R for Polymer Failure

The IFF-R method with Morse potentials was used to simulate the stress-strain response and failure of syndiotactic polyacrylonitrile (PAN). The simulation successfully captured bond dissociation and chain scission during tensile loading, leading to a quantitative prediction of the stress-strain curve up to failure. The computational speed of IFF-R (approximately 30 times faster than ReaxFF) enabled the simulation of significantly larger systems or longer timescales, making it practical for studying failure in complex polymer systems [23].

Protocols for Calculating Stress-Strain Curves

General Workflow for Stress-Strain Calculation

The following diagram outlines the high-level workflow for calculating a stress-strain curve using molecular dynamics, from potential selection to result analysis.

Protocol 1: Stress-Strain with ReaxFF for Polymers (Based on Polyacetylene)

This protocol details the steps to simulate the stress-strain curve of a polymer chain until fracture, as demonstrated for cis-polyacetylene [20].

Initial System Setup:

- Import the initial coordinate file for the polymer chain (e.g., cis-polyacetylene).

- Select the appropriate ReaxFF force field parameter file (e.g.,

CHO.fffor organic systems) [20].

Molecular Dynamics Parameters:

- Ensemble: Conduct the simulation at constant temperature (NVT).

- Thermostat: Use a Nosé-Hoover Chain (NHC) thermostat with a damping constant of 100.0 fs.

- Temperature: Set to 300.15 K.

- Total Steps: Set to a large number, e.g., 850,000 steps, to ensure the simulation runs until fracture.

- Sampling: Set sampling and checkpoint frequencies (e.g., 1000 and 50000 steps, respectively) [20].

Applying Deformation:

- In the MD deformation settings, define a deformation along the desired axis (e.g., the polymer chain axis).

- Set a constant Length velocity (e.g., 0.00002 Å/fs) to apply a constant strain rate [20].

Stress Calculation:

- Enable the Stress Tensor calculation in the properties settings. This is crucial for recording the internal stress during deformation [20].

Running the Simulation and Analysis:

- Run the simulation. The polymer will undergo cis-to-trans isomerization and eventually snap.

- Use visualization tools (e.g., AMSmovie) to plot the stress versus strain.

- Extract the numerical data for stress and strain. The fracture point is identified by a sharp drop in stress to zero [20].

Protocol 2: Modified Tersoff for 2D Materials (Based on h-BCN/Graphene)

This protocol is adapted from studies on h-BCN and graphene, where a modified Tersoff potential was necessary to obtain physically realistic fracture strengths [40].

Potential Selection and Validation:

- Obtain a modified Tersoff potential parameter file that addresses the unphysical strain-hardening of the original potential. This may involve a new cut-off scheme.

- Critical Step: Validate the modified potential by replicating the known mechanical properties (e.g., fracture strength) of a benchmark material like graphene before applying it to new systems [40].

Model Construction:

- Construct a 2D sheet of the material (e.g., h-BCN, graphene) with periodic boundary conditions in the plane.

- For h-BCN, ensure the correct atomic ratio (B/C/N = 1:1:1) and the most energetically stable atomic configuration [40].

Equilibration:

- Energy minimize the structure.

- Equilibrate the system in the NPT ensemble at the target temperature (e.g., 300 K) for at least 50 ps, allowing the box dimensions to relax to zero pressure.

Uniaxial Tensile Test:

- Apply a uniaxial strain along a specific crystal direction (e.g., zigzag or armchair).

- Use a constant engineering strain rate. A typical value used is 0.0005 ps⁻¹, but this can be varied to study strain rate effects [40].

- At each strain increment, allow the lateral dimensions of the simulation box to relax to zero stress.

- Calculate the stress tensor using the virial theorem at each step.

Analysis of Mechanical Properties:

- Plot the stress-strain curve. The initial slope provides the Young's modulus.

- Identify the fracture stress (maximum stress) and fracture strain (strain at maximum stress).

Table 3: Essential Resources for Interatomic Potentials and Simulations

| Resource Name / Tool | Type | Primary Function | Relevance to Stress-Strain Simulations |

|---|---|---|---|

| NIST Interatomic Potentials Repository [43] | Online Database | Hosts and evaluates potential parameter files. | Source for validated EAM, Tersoff, and other potentials. Check computed elastic properties. |

| LAMMPS | MD Software | A highly versatile and widely used MD simulator. | Used to run deformation simulations and compute the stress tensor. |

| ReaxFF Parameter Set (CHO.ff) [20] | Force Field File | Parameters for C/H/O systems in ReaxFF. | Essential for simulating combustion, polymers, and organic materials under mechanical load. |

| Modified Tersoff Potential [40] | Force Field Parameter Set | A Tersoff potential corrected for unphysical strain-hardening. | Crucial for obtaining realistic fracture strengths in 2D materials like graphene and h-BCN. |

| IFF-R / Morse Potential [23] | Method & Parameters | Enables bond breaking in classical force fields. | A faster alternative to ReaxFF for simulating failure in polymers and composites. |

The following decision diagram provides a visual guide for selecting the most appropriate potential function based on the material type and research objective.

Conclusions and Outlook

Selecting the correct interatomic potential is the cornerstone of obtaining reliable stress-strain curves from molecular dynamics simulations. EAM potentials are the gold standard for metallic systems, Tersoff potentials are effective for covalent materials but may require modification for fracture studies, and reactive potentials like ReaxFF and IFF-R are indispensable for modeling chemical changes and failure in complex materials. The emerging IFF-R approach, with its use of Morse potentials, offers a compelling combination of interpretability and computational efficiency for simulating bond dissociation. As the field advances, machine learning potentials are showing promise in achieving quantum-mechanical accuracy at a fraction of the cost, representing the next frontier in high-fidelity atomistic modeling of mechanical properties [44]. Researchers are advised to consult evaluation databases like the NIST repository to rigorously benchmark potentials for their specific system and property of interest [42] [43].

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation serves as a crucial computational tool for probing the mechanical behavior and underlying deformation mechanisms of materials at the atomic scale. The core of this investigation often involves subjecting a model system to controlled deformation and calculating the resulting stress-strain response. This application note details the fundamental methodologies for performing three primary types of deformation—uniaxial strain, shear, and complex deformation paths—within the context of generating stress-strain curves. Adherence to the protocols outlined herein ensures the generation of physically meaningful and reproducible data, facilitating a deeper understanding of material properties under mechanical load for researchers in materials science and computational physics.

Quantitative Comparison of Deformation Methods

The table below summarizes the characteristic parameters, primary applications, and key outcomes associated with the three deformation methods as demonstrated in recent MD studies.

Table 1: Summary of Deformation Methods in Molecular Dynamics Simulations

| Deformation Method | Characteristic Parameters | Primary Applications | Key Findings from Literature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Uniaxial Strain | Strain rate: 10⁻⁵ to 10⁻¹ nm/ps [45]Temperature: 290 K - 580 K [45]Applied pressure: 1 atm - 2.5 GPa [45] | Elastic modulus determination [45]Study of plasticity onset and fracture [20] [19] | Elastic modulus shows logarithmic dependence on deformation rate [45].Higher strain rates increase peak stress but have minor impact on curve shape in Cu nanobeams [19].Fracture point identified by stress drop to zero [20]. |

| Shear | Shear velocity: 0.05 - 0.15 Å/fs [46]Temperature: 250°C - 500°C [46] | Crystal phase transformation [46]Viscosity measurement [47] | In PVDF, higher temperature decreases shear modulus, hindering α- to β-phase transition [46].Higher shear velocity increases shear modulus, also hindering crystal transformation [46].Can be implemented via cell deformation or wall motion [47]. |

| Complex Paths | Non-uniaxial deformations (e.g., combined tension/compression and shear) [48]Deformation up to 100% strain [48] | Extraction of critical stress surfaces [48]Studying diverse deformation mechanisms [48] | Method involves applying rigid body rotation to realign simulation cell with MD software constraints [48].Provides a fingerprint of all deformation mechanisms in a material [48]. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Deformation Methods

Protocol 1: Uniaxial Deformation of a Thermoplastic Polyimide

This protocol outlines the procedure for determining the elastic modulus of amorphous thermoplastic polyimide R–BAPO via uniaxial deformation, based on the work of Nazarychev et al. [45].

System Preparation and Equilibration:

- Model Construction: Construct an initial system using 27 polymer chains with a degree of polymerization (Nₚ) of 8. Use the Gromos53a5 force field within the GROMACS MD package [45].

- Compression and Annealing: Compress the initial "polymer gas" to the target density. Perform cyclic annealing within the temperature range of 300 K to 600 K to relieve residual stresses.

- High-Temperature Equilibration: Equilibrate the system at 600 K (above its glass transition temperature) for 2 μs to ensure a well-equilibrated amorphous state [45].

Cooling and Sample Generation:

- Cooling Procedure: Cool the equilibrated system from 600 K down to 290 K. To investigate the effect of thermal history, apply different cooling rates (γc), for example, from 1.5 × 10¹⁰ to 1.5 × 10¹⁴ K/min [45].

- Sample Replication: Save multiple instantaneous configurations (e.g., 11 states) from the production run at 600 K to use as independent starting points for the cooling and deformation process, improving statistical reliability [45].

Application of Uniaxial Deformation:

- Barostat Configuration: Disable algorithms that constrain bond lengths (e.g., LINCS) and describe chemical bonds with a harmonic potential. Switch from an isotropic barostat to an anisotropic barostat.

- Deformation Setup: Set the compressibility in the deformation direction to zero, allowing the system to be strained. In the transverse directions, set the compressibility to that of the material (e.g., 4.5 × 10⁻¹⁰ Pa⁻¹ for the polyimide) [45].

- Straining: Deform the periodic simulation cell at a constant strain rate (γd) along one axis (X, Y, or Z). A range of strain rates from 10⁻⁵ to 10⁻¹ nm/ps should be explored to analyze rate dependence [45].

Data Analysis:

- Stress-Strain Curve: Calculate and plot the stress tensor component along the deformation direction against the applied strain.