Calculating Diffusion Coefficients from MD Simulations: A Complete Guide to MSD Analysis

This comprehensive guide details the calculation of diffusion coefficients from molecular dynamics simulations using mean square displacement analysis.

Calculating Diffusion Coefficients from MD Simulations: A Complete Guide to MSD Analysis

Abstract

This comprehensive guide details the calculation of diffusion coefficients from molecular dynamics simulations using mean square displacement analysis. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it covers foundational theory, practical implementation of MSD and VACF methods, troubleshooting for common pitfalls like finite-size effects and sub-diffusive dynamics, and advanced validation techniques including the novel T-MSD approach. The article synthesizes current best practices with emerging methodologies to enhance accuracy in studying drug delivery systems, battery materials, and biological diffusion processes.

Understanding Diffusion Fundamentals: From Einstein's Relation to MSD Theory

The Einstein relation stands as a cornerstone of modern physical chemistry and materials science, providing a fundamental bridge between the random microscopic motion of particles and their macroscopic diffusion properties. This principle, pioneered by Albert Einstein in his seminal 1905 paper on Brownian motion, enables researchers to quantify diffusion coefficients from the statistical analysis of particle displacements. In contemporary molecular dynamics (MD) research, this relationship has become an indispensable tool for characterizing molecular transport in systems ranging from simple liquids to complex biological environments.

The core of the Einstein relation lies in its elegant mathematical formulation: the mean squared displacement (MSD) of particles grows linearly with time, and the slope of this relationship directly yields the diffusion coefficient. For researchers investigating drug delivery systems, membrane permeability, and protein dynamics, this approach provides a powerful method to extract critical transport parameters from MD simulations [1] [2]. This application note examines the theoretical foundation of the Einstein relation, provides detailed protocols for its implementation in MD analysis, and presents key applications in pharmaceutical development, equipping researchers with practical methodologies for calculating diffusion coefficients from mean square displacement data.

Theoretical Foundation

The Einstein Relation and Mean Squared Displacement

The Einstein relation establishes a direct proportionality between the mean squared displacement of particles and elapsed time, expressed through the Einstein-Smoluchowski equation:

[ \langle [r(t) - r(0)]^2 \rangle = 2dDt ]

where (\langle [r(t) - r(0)]^2 \rangle) represents the mean squared displacement in (d) dimensions, (D) is the diffusion coefficient, and (t) is time [2]. In three dimensions ((d = 3)), this simplifies to:

[ MSD = \langle [r(t) - r(0)]^2 \rangle = 6Dt ]

The diffusion coefficient (D) is subsequently calculated from the slope of the linear portion of the MSD versus time plot:

[ D = \frac{1}{2d} \lim_{t \to \infty} \frac{d}{dt} MSD(t) ]

This formulation applies to particles undergoing normal diffusion in homogeneous systems where their motion follows Fick's laws [3].

Table 1: Key Parameters in the Einstein Relation

| Parameter | Symbol | Units | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean squared displacement | MSD | Ų, nm² | Average squared distance particles move over time |

| Diffusion coefficient | D | cm²/s, m²/s | Measure of how rapidly particles diffuse |

| Dimensionality | d | - | Number of dimensions considered (1, 2, or 3) |

| Time | t | ps, ns, µs | Elapsed simulation time |

The Stokes-Einstein Relation

For spherical particles in a continuous medium, the diffusion coefficient can be further related to system properties through the Stokes-Einstein relation:

[ D = \frac{k_B T}{6\pi\eta r} ]

where (k_B) is Boltzmann's constant, (T) is temperature, (\eta) is solvent viscosity, and (r) is the hydrodynamic radius of the diffusing particle [2] [4]. This extension allows researchers to connect microscopic MD simulations with macroscopic experimental measurements, though it's important to note that breakdowns of this relation can occur in supercooled liquids, polymer systems, and confined environments [4].

Experimental Protocols

MD Trajectory Preparation

Proper trajectory preparation is essential for accurate MSD calculation. The following protocol ensures appropriate starting conditions for analysis:

- System Equilibration: Confirm that the system has reached equilibrium before beginning production runs by monitoring potential energy, temperature, and pressure stability.

- Trajectory Unwrapping: Process trajectories to account for periodic boundary conditions using unwrapped coordinates or "nojump" correction to prevent artificial displacement artifacts [3]. In GROMACS, this can be achieved using:

- Frame Selection: Specify appropriate time intervals using parameters such as

-b(begin time),-e(end time), and-dt(time interval) to ensure adequate sampling while managing computational expense [5].

MSD Calculation Methods

Single Time Origin Approach

The simplest approach calculates MSD using a single reference point at time zero:

[ MSD(t) = \frac{1}{N} \sum{i=1}^{N} [ri(t) - r_i(0)]^2 ]

where (N) is the number of particles and (r_i(t)) is the position of particle (i) at time (t). While computationally efficient, this method provides poor statistics for longer time intervals due to decreasing numbers of measurable frames [3].

Multiple Time Origin Approach

For improved statistical accuracy, the multiple time origin method averages over multiple starting points:

[ MSD(t) = \frac{1}{N(M-m+1)} \sum{i=1}^{N} \sum{k=0}^{M-m} [ri(tk + tm) - ri(t_k)]^2 ]

where (M) is the total number of frames, (m) is the lag time in frame units, and (t_k) are the multiple time origins [6]. This approach significantly enhances statistical quality, particularly for longer time scales, by averaging over all possible time origins within the trajectory. Implementation should ensure non-overlapping time blocks where n_sigma >= n_tau for optimal results [6].

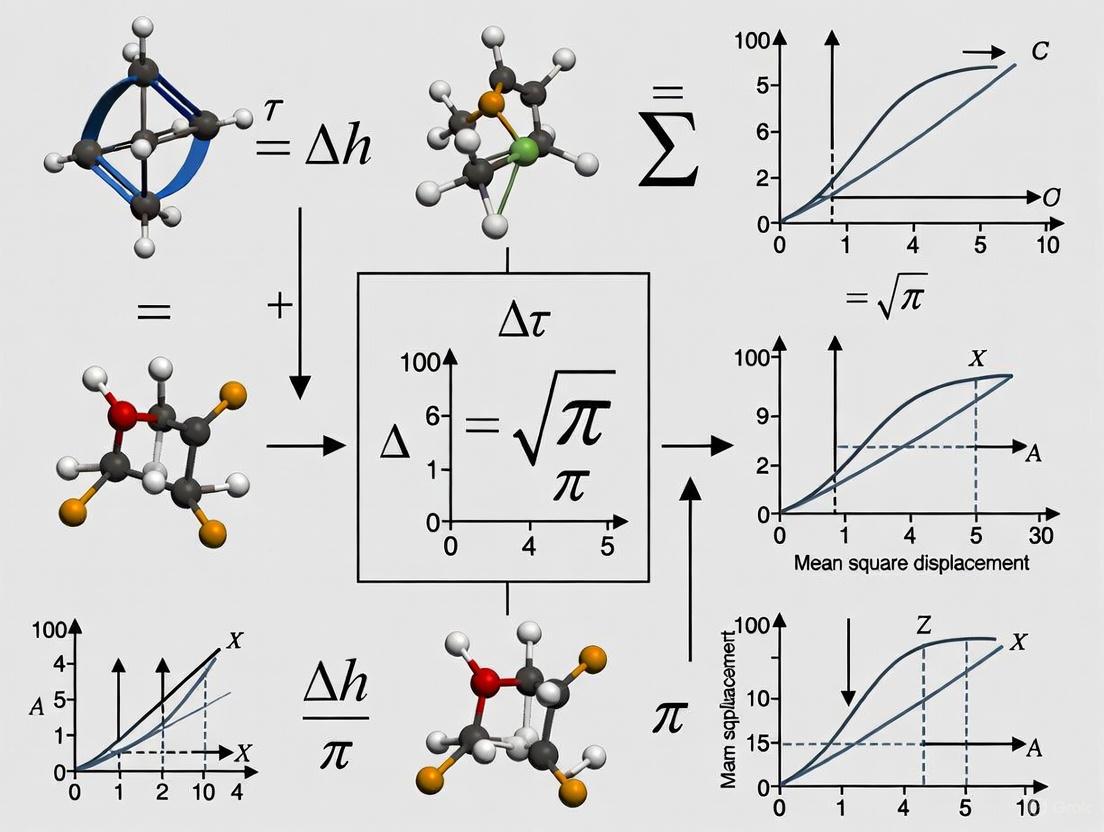

Workflow for Diffusion Coefficient Calculation

The following diagram illustrates the complete workflow for calculating diffusion coefficients from MD simulations using the Einstein relation:

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Tools for MSD Analysis and Diffusion Coefficient Calculation

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| MD Software Packages | GROMACS [5], AMBER, NAMD, CHARMM [1] | Perform molecular dynamics simulations |

| Analysis Tools | MDAnalysis [3], PyBILT [6], LAMMPS [7] | Analyze trajectories and compute MSD |

| Force Fields | AMBER, CHARMM, GROMOS, OPLS [1] | Define molecular interactions and potentials |

| Visualization Software | VMD, PyMOL, Chimera | Visualize trajectories and verify system behavior |

| Specialized Modules | gmx msd in GROMACS [5], EinsteinMSD in MDAnalysis [3] |

Directly compute MSD and diffusion coefficients |

Data Analysis and Interpretation

Identifying the Linear MSD Regime

Accurate diffusion coefficient calculation requires careful identification of the linear regime in MSD plots:

- Short-Time Exclusion: Exclude short-time ballistic regime where MSD ∝ (t^2), characteristic of inertial particle motion before randomization by collisions.

- Long-Time Exclusion: Discard long-time portions where MSD plateaus or becomes noisy due to insufficient sampling and averaging [3].

- Linear Selection: Identify the intermediate time scale where MSD shows clear linear behavior with time. This represents the diffusive regime appropriate for Einstein relation application.

- Log-Log Verification: Use log-log plots of MSD versus time to confirm linear regime, which should exhibit a slope of approximately 1 [3].

Diffusion Coefficient Extraction Protocol

The following step-by-step protocol details diffusion coefficient extraction from MSD data:

- Plot MSD versus Time: Generate MSD plot using multiple time origin method for optimal statistics [6].

- Define Fitting Range: Select appropriate start and end points for linear fitting. The GROMACS

gmx msdtool uses-beginfitand-endfitparameters, with default values of 10% and 90% of total time respectively when set to -1 [5]. - Perform Linear Regression: Apply least squares fitting to the linear region: [ MSD(t) = m \cdot t + c ] where (m) is the slope and (c) is the intercept.

- Calculate Diffusion Coefficient: Compute (D) using (D = \frac{m}{2d}), where (d) is the dimensionality.

- Estimate Error: Determine statistical uncertainty using methods such as block averaging or by comparing diffusion coefficients from multiple trajectory segments [7].

Dimensionality Considerations

The Einstein relation can be applied to different dimensionalities based on the system of interest:

- 3D Diffusion: Use (D = \frac{MSD}{6t}) for bulk diffusion [3]

- 2D Diffusion: Use (D = \frac{MSD}{4t}) for surface or membrane diffusion [8] [5]

- 1D Diffusion: Use (D = \frac{MSD}{2t}) for constrained linear diffusion

In GROMACS, dimensionality can be specified using the -type option for specific axes or -lateral for lateral diffusion in membranes [5].

Applications in Drug Discovery

The Einstein relation provides critical insights across multiple stages of pharmaceutical development:

Drug Delivery System Design

In nanoparticle drug formulations, MSD analysis enables quantification of nanoparticle diffusion through biological barriers, predicting delivery efficiency and distribution patterns [1]. Diffusion measurements inform the design of targeted delivery systems by characterizing how carrier properties affect transport rates.

Membrane Permeability Assessment

For transmembrane drug transport, lateral MSD analysis in lipid bilayers yields diffusion coefficients that correlate with permeability, particularly for passive diffusion mechanisms [1] [6]. This approach helps predict drug absorption and distribution without expensive experimental measurements.

Solubility and Formulation Optimization

Diffusion coefficients calculated via the Einstein relation contribute to solubility prediction through their relationship with molecular size and interaction parameters [1] [2]. This enables rapid screening of candidate molecules and formulation components during pre-clinical development.

Table 3: Experimentally Determined Diffusion Coefficients of Pharmaceutical Compounds

| Compound | Molecular Weight (g/mol) | Experimental D (×10⁻⁶ cm²/s) | Calculated D (×10⁻⁶ cm²/s) | Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Xylose | 150 | 7.50 | 7.24-7.94 | Monosaccharide drug vehicle |

| Glucose | 180 | 6.79 | 6.65-7.48 | Metabolic drug targeting |

| Sucrose | 342 | 5.23 | 5.07-6.09 | Pharmaceutical stabilizer |

| Aspirin | 180 | 6.67 | 6.64-7.47 | NSAID drug |

| Loxoprofen | 246 | 5.79 | 5.79-6.51 | Anti-inflammatory drug |

Data adapted from PMC7709040 [2]

Technical Considerations and Limitations

Practical Implementation Challenges

Researchers should address these common challenges in MSD analysis:

- Trajectory Requirements: Ensure sufficient trajectory length to observe diffusive behavior, typically 10-100 times longer than the characteristic diffusion time [3].

- Statistical Sampling: For molecular systems, average over multiple molecules (≥100) to achieve reliable statistics [7].

- Finite-Size Effects: Account for system size limitations that can artificially suppress long-time diffusion [7].

- Force Field Dependence: Verify that results are consistent across different force fields, as diffusion coefficients can be sensitive to interaction parameters [7].

Advanced Applications

Recent methodological developments have expanded Einstein relation applications:

- Aging Systems: Generalized Einstein relations have been developed for systems with time-dependent temperatures and friction, relevant to granular materials and cooling processes [9].

- SER Breakdown Analysis: In phase-change materials and supercooled liquids, the breakdown of the Stokes-Einstein relation provides insights into dynamic heterogeneities and fragmentation transitions [4].

- Heterogeneous Systems: Anisotropic diffusion analysis (Dx, Dy, Dz) reveals directional transport limitations in ordered or confined environments [7].

The Einstein relation remains a fundamental pillar connecting microscopic particle dynamics to macroscopic diffusion phenomena in molecular dynamics research. Through careful application of the protocols outlined in this application note - including proper trajectory preparation, appropriate MSD calculation methods, and rigorous linear regime selection - researchers can reliably extract diffusion coefficients from MD simulations. These measurements provide valuable insights into drug transport mechanisms, material properties, and biological processes, enabling more efficient pharmaceutical development and materials design. As MD simulations continue to evolve in scale and accuracy, with recent studies encompassing systems of billions of atoms [1], the Einstein relation will maintain its critical role in bridging molecular-level interactions with observable macroscopic properties.

The Mean Square Displacement (MSD) is a fundamental statistical measure in molecular dynamics (MD) simulations used to quantify the average squared distance particles travel over time. It provides crucial insights into atomic and molecular mobility, serving as a primary connection between microscopic particle motion and macroscopic transport properties. In the context of a broader thesis on calculating diffusion coefficients, the MSD is indispensable because it directly enables the computation of self-diffusivity through the Einstein relation [10] [11].

Formally, the MSD for a system of N particles is defined as:

MSD(t) = ⟨|r(t) - r(0)|²⟩ [10]

where r(t) is the position vector of a particle at time t, and the angle brackets ⟨...⟩ represent an ensemble average. In practical MD simulations, this average is computed over all equivalent particles in the system and over multiple time origins along the trajectory to improve statistics [11] [12]. The most common computational expression becomes:

MSD(τ) = 1/N Σᵢ [rᵢ(t) - rᵢ(t₀)]² averaged over all time origins t₀ [11].

Table: Fundamental Characteristics of Mean Square Displacement

| Aspect | Description | Mathematical Relation |

|---|---|---|

| Core Definition | Average squared distance particles move from initial positions over time [11] | MSD(t) = ⟨|r(t) - r(0)|²⟩ |

| Computational Form | Average over all particles and multiple time origins [13] | MSD(τ) = 1/N Σᵢ [rᵢ(t) - rᵢ(t₀)]² |

| Dimensional Dependency | MSD increases with system dimensionality for same diffusion coefficient [11] | MSD = 2dDτ (d=dimensions, D=diffusion coeff.) |

| Time Regimes | Short-time ballistic vs. long-time diffusive behavior [10] [14] | MSD ∼ t² (ballistic); MSD ∼ t (diffusive) |

Physical Significance and Theoretical Background

The physical significance of MSD extends across multiple domains of materials science and soft matter physics. It represents the most common measure of the spatial extent of random motion and can be thought of as measuring the portion of the system "explored" by the random walker [11]. In molecular systems, particles undergo constant collisions that prevent simple straight-line motion, resulting instead in a path that approximates a random walk [14]. This random motion is fundamental to fluidity and diffusion processes in gases, liquids, and even solids to some extent.

The time dependence of MSD reveals critical information about the system's dynamics and state. At very short time scales (before significant collisions occur), particles move with approximately constant velocity, resulting in parabolic, quadratic growth of MSD with time (MSD ∼ t²) [14]. This is known as the ballistic regime. After numerous collisions have occurred, the motion transitions to diffusive behavior characterized by linear growth with time (MSD ∼ t) [10]. The crossover between these regimes provides information about collision rates and system density. In complex systems like polymer melts, additional intermediate scaling regimes may appear with characteristic exponents that reveal constraints on molecular motion, such as the famous t¹/⁴ scaling predicted by tube models for entangled polymers [15].

Table: MSD Time Dependence in Different Physical Regimes

| System Type | Short-Time Behavior | Long-Time Behavior | Intermediate Behaviors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Simple Liquids/Gases [10] [14] | Ballistic: MSD ∼ t² |

Diffusive: MSD ∼ t |

Exponential transition |

| Polymer Melts (Long Chains) [15] | MSD ∼ t¹/² |

MSD ∼ t |

MSD ∼ t¹/⁴ (hypothesized) |

| Entangled Polymers [15] | Rouse-like: MSD ∼ t¹/² |

Center-of-mass diffusion: MSD ∼ t |

Tube confinement effects |

| Anomalous Diffusion [16] | Varies by system | Varies by system | Subdiffusion: MSD ∼ tᵅ (α<1) |

MSD Calculation Protocols in Molecular Dynamics

Fundamental Computational Methodology

The accurate calculation of MSD in MD simulations requires careful attention to several implementation details. The core algorithm involves tracking particle positions over time and computing the squared displacement from reference positions. For a trajectory with N frames, the MSD for lag time τ = nΔt is typically computed using a "windowed" approach that averages over all possible time origins:

MSD(τ) = 1/(N-n) Σᵢ [r(iΔt + τ) - r(iΔt)]² where the sum is over all possible starting times iΔt [11].

For enhanced computational efficiency, particularly with long trajectories, a Fast Fourier Transform (FFT)-based algorithm can reduce the scaling from O(N²) to O(N log N) [12]. The tidynamics package implements this FFT-based approach and can be accessed in MDAnalysis by setting fft=True [12]. However, this requires careful handling of periodic boundary conditions and trajectory unwrapping.

Critical Implementation Considerations

Several practical considerations are essential for obtaining physically meaningful MSD results:

Trajectory Unwrapping: MSD calculation requires coordinates in the unwrapped convention, meaning atoms that pass periodic boundaries must not be wrapped back into the primary simulation cell [12]. In GROMACS, this can be achieved using

gmx trjconvwith the-pbc nojumpflag.Statistical Averaging: For reliable statistics, average both over all particles of the same type and over multiple time origins. For even better statistics, combine multiple independent simulation replicates by concatenating MSD results rather than trajectories [12].

Frame Rate Selection: Maintain a relatively small elapsed time between saved frames to properly capture the short-time dynamics while balancing storage requirements [12].

Finite-Size Corrections: For accurate diffusion coefficients, apply corrections for finite system size effects, which can be significant in small simulation boxes [12].

MSD Calculation Workflow

Calculating Diffusion Coefficients from MSD

The primary application of MSD in many research contexts is determining self-diffusion coefficients through the Einstein relation [10] [12]. This relationship emerges from the long-time limit of the MSD's time derivative:

D = lim(t→∞) 1/(2d) * d/dt MSD(t)

where d is the dimensionality of the MSD calculation [10] [11].

For practical computation from discrete MD data, the diffusion coefficient is obtained by fitting a straight line to the MSD curve in the linear regime:

D = slope / (2d)

where slope is obtained from linear regression of MSD versus time in the diffusive regime [12]. The dimensionality factor d depends on the type of MSD calculated: d=3 for 3D MSD (xyz), d=2 for planar MSD (xy, xz, yz), and d=1 for one-dimensional MSD (x, y, z) [12].

The critical step in this process is identifying the appropriate linear regime for fitting. This represents the "middle" of the MSD plot, excluding both ballistic trajectories at short time-lags and poorly averaged data at long time-lags [12]. A log-log plot of MSD versus time can help identify this regime, where the slope should be approximately 1 for normal diffusion [12]. For example, in a 3D random walk system, the MSD should follow MSD(τ) = 6Dτ, meaning the slope of the MSD plot is 6D [12].

Table: Diffusion Coefficient Calculation from MSD

| Dimension | MSD Type | Einstein Relation | Example System |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1D [11] | x, y, or z only |

D = slope/2 |

Confined diffusion |

| 2D [11] | xy, xz, or yz |

D = slope/4 |

Surface diffusion |

| 3D [11] [12] | xyz (all spatial dimensions) |

D = slope/6 |

Bulk liquids, gases |

| Anomalous [16] | Any, with MSD ∼ tᵅ |

D_α = MSD/(2dtᵅ) |

Complex, crowded systems |

Advanced Applications and Research Contexts

Polymeric Systems

In polymer physics, MSD analysis reveals rich dynamical behavior across different time and length scales. Rather than a single mean-square displacement, polymer simulations typically track three distinct types [15]:

- g₁(t): Atomic MSD of individual beads or segments

- g₂(t): MSD of monomer beads relative to their polymer's center of mass

- g₃(t): Center-of-mass MSD of entire polymer chains

These different MSDs exhibit distinct scaling behaviors that theoretically follow power laws g(t) ∼ tᵅ with different exponents α depending on chain length and time scale [15]. For instance, the tube-reptation model predicts g₁(t) ∼ t¹/⁴ for entangled polymers at intermediate times, though recent careful numerical analysis suggests these hypothesized power-law regimes are often not present, with plots of log(g(t)) against log(t) showing smooth curves whose slopes vary continuously with time [15].

Biological and Soft Matter Applications

In biophysical applications, MSD analysis helps characterize internal motions in proteins and other biomolecules. For example, atomic mean-square displacements can measure variability in atomic position distribution functions, with applications in understanding protein flexibility, thermostability, and function [17]. When analyzing protein dynamics, special attention must be paid to multimodal distribution functions, where atoms occupy multiple distinct positions, requiring within-block MSD calculations rather than total MSD for meaningful results [17].

In drug development contexts, MSD analysis can optimize how therapeutic compounds diffuse through biological membranes and cellular environments [16]. The technique helps characterize materials at the atomic level, which is crucial for designing better delivery systems with tailored properties for specific applications [16].

Materials Science Applications

MSD analysis finds extensive application in materials science, particularly in characterizing transport properties of complex fluids and energy storage materials. For instance, in studying aqueous solutions for binary ice preparation, MSD helps elucidate how additives like ethanol, NaCl, and SiO₂ nanoparticles affect water molecule mobility and hydrogen bonding networks [18]. These interactions directly influence macroscopic properties like viscosity and diffusion rates, enabling rational design of more efficient energy storage systems.

Table: Essential Resources for MSD Analysis in MD Simulations

| Resource/Reagent | Function/Purpose | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| MDAnalysis [12] | Python toolkit for MD trajectory analysis | msd.EinsteinMSD(u, select='all', msd_type='xyz', fft=True) |

| tidynamics [12] | Fast FFT-based MSD computation | Required for fft=True in MDAnalysis to enable O(N log N) scaling |

| Unwrapped Trajectories [12] | Prevents boundary artifacts in MSD | GROMACS: gmx trjconv -pbc nojump |

| Linear Regression Tools [12] | Fitting diffusion coefficients from MSD | scipy.stats.linregress(lagtimes, msd) |

| Multiple Replicates [12] | Improves statistical reliability | Concatenate MSD results, not trajectories, from independent runs |

| Hydrogen Bond Analysis [18] | Correlates MSD with molecular interactions | Complementary analysis explaining diffusion changes with additives |

In molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, the Mean Squared Displacement (MSD) is a fundamental metric for quantifying the spatial extent of random particle motion and for calculating the self-diffusion coefficient (D), a critical parameter in materials science and drug development [11] [10]. The diffusion coefficient reveals the speed at which molecules, such as solvents, APIs, or excipients, move through a medium, directly influencing crucial pharmaceutical processes like drug release, permeation, and transport [12] [19].

This Application Note delineates the core mathematical formulations, provides a validated protocol for deriving diffusion coefficients from MD trajectories, and contextualizes the findings within a broader thesis on molecular transport.

Key Mathematical Foundations

The Mean Squared Displacement (MSD)

The MSD is defined as the average squared distance a particle travels from its reference position over a given time interval, ( t ) [11]. For a single particle ( i ), the MSD over time ( t ) is:

[ \text{MSD}i(t) = \langle | \mathbf{r}i(t) - \mathbf{r}_i(0) |^2 \rangle ]

In practice, this is averaged over an ensemble of ( N ) equivalent particles to improve statistics [11] [10]:

[ \text{MSD}(t) = \frac{1}{N} \sum_{i=1}^N | \mathbf{r}^{(i)}(t) - \mathbf{r}^{(i)}(0) |^2 ]

Here, ( \mathbf{r}(t) ) and ( \mathbf{r}(0) ) represent the particle's position vector at time ( t ) and the reference time, respectively. The angle brackets ( \langle \rangle ) denote the ensemble average [11].

The Einstein Relation: From MSD to Diffusion Coefficient

The self-diffusivity, ( D ), is related to the long-time slope of the MSD versus time plot via the Einstein relation [12] [10]:

[ Dd = \frac{1}{2d} \lim{t \to \infty} \frac{d}{dt} \text{MSD}(t) ]

In this equation, ( d ) represents the dimensionality of the MSD calculation. For the common case of a 3-dimensional (3D) MSD (( d=3 )), this simplifies to:

[ D = \frac{\text{slope(MSD)}}{6} ]

This formulation is widely used in MD analysis tools such as LAMMPS [20] and GROMACS [21]. The MSD of a randomly diffusing particle exhibits a linear relationship with time in the long-time limit, and the diffusion coefficient is proportional to the slope of this linear regime [10].

Experimental Protocol: Calculating D from MD Simulations

This protocol provides a step-by-step methodology for extracting the diffusion coefficient of a species (e.g., water, ions, a drug molecule) from an MD trajectory, utilizing common software frameworks.

Prerequisites and Input Data

- MD Trajectory File: A molecular dynamics trajectory file in a format such as XTC, TRR, DCD, or binary format. The trajectory should represent the system's evolution over time.

- Topology File: A file containing structural information (e.g., GRO, PDB, PSF, or topology format).

- Software: An MD analysis package capable of computing MSD (e.g., MDAnalysis [12], GROMACS

gmx msd[21], or LAMMPS [20]). - Critical Consideration - Unwrapped Coordinates: The atomic coordinates in the trajectory must be in the "unwrapped" convention [12]. When atoms cross periodic boundaries, they must not be wrapped back into the primary simulation cell, as this would artificially truncate displacements and invalidate the MSD calculation. In GROMACS, this can be achieved using

gmx trjconv -pbc nojump.

Step-by-Step Procedure

Step 1: Compute the MSD Profile Use your analysis software to calculate the MSD as a function of lag time (( \tau ) or ( \Delta )).

Step 2: Identify the Linear (Diffusive) Regime Plot the MSD against lag time on a log-log scale. The MSD will typically show:

- A ballistic regime at very short times (slope ~2).

- A linear, diffusive regime at intermediate-to-long times (slope ~1) [10].

Select the linear segment for fitting. As a rule of thumb, many implementations (like

gmx msd) default to using the central 10% to 90% of the data to avoid non-diffusive artifacts at the extremes [21].

Step 3: Perform Linear Regression

Fit the selected linear segment of the MSD vs. time data to the model:

[ \text{MSD}(t) = m \cdot t + c ]

where ( m ) is the slope. Using a tool like scipy.stats.linregress is appropriate [12]:

Step 4: Calculate the Diffusion Coefficient Apply the Einstein relation for a 3D system: [ D = \frac{\text{slope}}{6} ] Ensure unit consistency. The slope is typically in nm²/ps. To convert to the more common cm²/s, multiply by a factor of 0.01: ( D{cm^2/s} = \frac{\text{slope}{nm^2/ps} \times 0.01}{6} ) [21].

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the complete experimental protocol from MD simulation to the final diffusion coefficient.

Diagram 1: The complete workflow for calculating a diffusion coefficient from an MD trajectory, highlighting the critical pre-processing, analysis, and result phases.

Data Presentation and Analysis

Table 1: Key parameters and their descriptions for MSD analysis.

| Parameter | Symbol | Description | Typical Units in MD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Squared Displacement | MSD((t)) | Average squared displacement over time. | nm² |

| Lag Time | ( \tau ), ( \Delta ), ( t ) | Time interval for displacement measurement. | ps, ns |

| Dimensionality | ( d ) | Spatial dimensions of the MSD calculation. | Dimensionless |

| Slope | ( m ) | Slope of the linear fit of MSD vs. time. | nm²/ps |

| Diffusion Coefficient | ( D ) | Measure of molecular mobility from Einstein relation. | cm²/s |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key software and computational resources for MSD analysis in molecular research.

| Item / Resource | Function / Description | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| MDAnalysis [12] | A Python library for MD trajectory analysis. | Used for MSD calculation and other trajectory analyses. Supports FFT-based algorithms for efficiency. |

GROMACS gmx msd [21] |

A built-in tool in the GROMACS suite for MSD analysis. | Directly calculates MSD and can fit D. Uses the 10%-90% of the time axis for fitting by default. |

| LAMMPS [20] | A classical molecular dynamics simulator. | Offers the compute msd command to calculate MSD during a simulation run. |

| Unwrapped Trajectory [12] | A trajectory where atoms are not reinserted into the primary unit cell. | Critical input. Ensures correct measurement of long-distance diffusion. |

| Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) [12] | An algorithm for efficient MSD computation. | Reduces computational cost from O(N²) to O(N log N). Implemented in MDAnalysis and tidynamics. |

Critical Methodological Considerations

- Trajectory Length and Sampling: The simulation must be long enough to clearly observe the linear diffusive regime. A good rule of thumb is that the MSD should grow by at least one order of magnitude within this regime for a reliable fit [21].

- Statistical Averaging: For a robust MSD, average over as many particles and as many time origins as possible. Combining multiple independent simulation replicates can further improve statistics and error estimation [12].

- Finite-Size Effects: The calculated diffusion coefficient can be influenced by the size of the simulation box. Larger system sizes are generally preferred, and corrections (e.g., based on the system's viscosity) may be necessary for publication-quality results [12].

- Error Analysis: The diffusion coefficient should be reported with an uncertainty estimate. This can be derived from the standard error of the linear regression slope or by block-averaging over multiple trajectory segments [21].

The study of molecular diffusion is fundamental to understanding a vast array of processes in chemical, biological, and materials sciences. In molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, diffusion characterizes the stochastic, random motion of particles over time and provides critical insights into system dynamics and transport properties. The mean-squared displacement (MSD), defined as the average squared distance a particle travels over time, serves as the primary metric for quantifying diffusion, measuring the deviation of a particle's position with respect to a reference position over time [11]. Through MSD analysis, researchers can extract diffusion coefficients that quantify transport rates—essential parameters for predicting molecular behavior in applications ranging from membrane design to drug delivery systems [22].

A crucial aspect of interpreting MSD data lies in recognizing that particle transport manifests in three distinct temporal regimes: ballistic, subdiffusive, and normal (Fickian) diffusion. Each regime exhibits a characteristic relationship between MSD and time, governed by different underlying physical mechanisms. Molecular dynamics simulations provide the unique capability to explore all three regimes of penetrant transport from a molecular-level viewpoint, offering insights that are often challenging to obtain experimentally [22]. This protocol outlines the theoretical foundations, computational methodologies, and analytical frameworks required to identify, characterize, and quantify these diffusion regimes within MD simulations, with particular emphasis on calculating diffusion coefficients for research and development applications.

Theoretical Foundations of Diffusion Regimes

The Mean-Squared Displacement Framework

The mean-squared displacement is a statistical measure that quantifies the spatial extent of random particle motion. In three-dimensional systems, the MSD is calculated as the average over all particles of the squared displacement from their initial positions:

[ \text{MSD}(t) = \langle | \mathbf{r}(t) - \mathbf{r}(0) |^2 \rangle = \frac{1}{N} \sum_{i=1}^{N} | \mathbf{r}^{(i)}(t) - \mathbf{r}^{(i)}(0) |^2 ]

where (\mathbf{r}^{(i)}(t)) is the position of particle (i) at time (t), and (N) is the total number of particles [11]. The time evolution of the MSD reveals fundamental information about the nature of the particle's motion and its interaction with the surrounding environment.

Characteristic Diffusion Regimes

Particle diffusion in MD simulations typically progresses through three temporal regimes, each with distinct MSD signatures:

Ballistic Regime: At very short time scales (typically less than picoseconds), particles move with nearly constant velocity before experiencing significant collisions. In this regime, the MSD increases quadratically with time: (\text{MSD} \propto t^2) [22]. This behavior reflects Newtonian mechanics before randomizing collisions dominate.

Subdiffusive Regime: At intermediate time scales, particles experience restricted motion due to trapping phenomena, molecular crowding, or binding events. This manifests as a power-law scaling where (\text{MSD} \propto t^\alpha) with (0 < \alpha < 1) [22]. Research has shown that the random walk on a fractal (RWF) model often provides the most appropriate explanation for these subdiffusion phenomena [22].

Normal (Fickian) Diffusion Regime: At sufficiently long time scales, particle motion becomes randomized through numerous collisions, leading to linear MSD scaling with time: (\text{MSD} \propto t) [22] [11]. This regime represents standard Brownian motion where the Einstein relation for diffusion coefficient calculation becomes valid.

Table 1: Characteristics of Diffusion Regimes in Molecular Dynamics

| Regime | Time Scale | MSD Scaling | Physical Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ballistic | Short (ps) | MSD (\propto t^2) | Free motion before significant collisions |

| Subdiffusive | Intermediate | MSD (\propto t^\alpha) ((0<\alpha<1)) | Trapping, crowding, or binding effects |

| Normal (Fickian) | Long (ns-µs) | MSD (\propto t) | Randomized Brownian motion |

The transitions between these regimes provide molecular-level insights into material properties. For example, studies of methane transport in polypropylene (PP), poly(propylmethylsiloxane) (PPMS), and poly(4-methyl-2-pentyne) (PMP) revealed that the duration of the ballistic regime correlates with polymer cavity size and accessibility—PPMS with the largest cavities exhibits the longest ballistic regime, followed by PMP and PP [22].

Computational Protocols for MSD Analysis

MD Simulation Setup Requirements

Proper simulation setup is essential for obtaining meaningful diffusion data. Several critical factors must be considered:

Trajectory Length and Sampling: Simulations must be sufficiently long to capture the Fickian diffusion regime. While solvent self-diffusion coefficients often converge within nanoseconds, reliable solute diffusion in solution may require much longer simulations—up to tens or hundreds of nanoseconds for convergence [23].

System Size Effects: Small simulation boxes can artificially restrict diffusion due to periodic boundary condition artifacts. The Yeh-Hummer correction accounts for this finite-size effect: (D\text{corrected} = D\text{PBC} + 2.84 k_\mathrm{B}T/(6 \pi \eta L)), where (L) is the box dimension [24].

Trajectory Unwrapping: MSD analysis requires unwrapped coordinates where atoms passing periodic boundaries are not artificially wrapped back into the primary simulation cell [25]. Various simulation packages provide utilities for this conversion (e.g.,

gmx trjconvwith the-pbc nojumpflag in GROMACS).

MSD Calculation Workflow

The following workflow diagram illustrates the complete protocol for MSD analysis and diffusion coefficient calculation:

Figure 1: Workflow for calculating diffusion coefficients from MD simulations

Step 1: MSD Calculation The MSD can be computed efficiently using Fast Fourier Transform (FFT)-based algorithms with (N \log(N)) scaling [25]. For a 3D system, the MSD is calculated as:

[ \text{MSD}(\tau) = \langle | \mathbf{r}(t+\tau) - \mathbf{r}(t) |^2 \rangle_t ]

where (\tau) is the lag time, and the average is performed over all possible time origins (t) [25]. Specialized software packages like MDAnalysis.analysis.msd provide optimized implementations with FFT acceleration [25].

Step 2: Diffusion Regime Identification Plot MSD versus lag time on a log-log scale to visually identify the three diffusion regimes [25]. The ballistic regime appears with slope ≈ 2, the subdiffusive regime with slope between 0 and 1, and the normal diffusion regime with slope ≈ 1. This graphical approach enables clear demarcation of regime boundaries.

Step 3: Diffusion Coefficient Calculation For normal diffusion, the diffusion coefficient (D) relates to the MSD slope through the Einstein relation:

[ D = \frac{1}{2d} \lim_{t \to \infty} \frac{d}{dt} \text{MSD}(t) ]

where (d) is the dimensionality [25] [24]. In three dimensions, this simplifies to:

[ D = \frac{1}{6} \lim_{t \to \infty} \frac{d}{dt} \text{MSD}(t) ]

Select a linear segment from the Fickian regime and perform linear regression to estimate the slope. The diffusion coefficient equals one-sixth of this slope for 3D systems [24].

Advanced Analysis Techniques

- Velocity Autocorrelation Method: As an alternative approach, diffusion coefficients can be calculated using the Green-Kubo relation:

[ D = \frac{1}{3} \int_0^\infty \langle \mathbf{v}(0) \cdot \mathbf{v}(t) \rangle dt ]

where (\mathbf{v}(t)) is the velocity vector at time (t) [24].

Block Averaging for Inhomogeneous Systems: For systems with multimodal atomic position distributions, divide trajectories into blocks and compute within-block mean-square displacements to obtain unbiased variance estimates [17].

Uncertainty Quantification: Recent research emphasizes that uncertainty in MD-derived diffusion coefficients depends not only on simulation data but also on analysis protocol choices, including statistical estimator selection and fitting window extent [26].

Research Reagent Solutions and Tools

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools for Diffusion Analysis

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| MD Simulation Software | GROMACS, AMBER, LAMMPS | Production MD trajectories |

| MSD Analysis Tools | MDAnalysis.analysis.msd, GROMACS gmx msd |

Calculate mean-squared displacements |

| Trajectory Processing | MDAnalysis, MDTraj | Handle trajectory formatting and unwrapping |

| Statistical Analysis | Python SciPy, GraphPad Prism | Linear regression of MSD data |

| Visualization | LabPlot, Matplotlib, VMD | Plot MSD and analyze diffusion regimes |

Specialized analysis tools like MDAnalysis implement efficient FFT-based MSD algorithms, significantly accelerating computation compared to naive approaches [25]. GROMACS includes built-in MSD analysis through the gmx msd command, which can calculate diffusion coefficients for selected atom groups or molecules [8]. For statistical analysis and curve fitting, packages like SciPy provide robust linear regression capabilities, while specialized scientific graphing software like LabPlot offers publication-quality visualization [27].

Application Notes for Drug Development

Understanding diffusion regimes has direct relevance to pharmaceutical research and development:

Membrane Permeation Studies: Investigating the transport of drug molecules through biological membranes or polymer barriers requires analysis of all three diffusion regimes. The duration of the ballistic and subdiffusive regimes reveals information about membrane porosity and drug-polymer interactions [22].

Protein Diffusion and Aggregation: The diffusion behavior of proteins in solution affects drug binding kinetics and aggregation phenomena. Block averaging techniques help analyze mean-square displacements in proteins, particularly when comparing thermophilic and mesophilic variants [17].

Solubility and Formulation Optimization: Studies of small molecule diffusion in solvents and excipients inform formulation development. The General AMBER Force Field (GAFF) has demonstrated good performance in predicting diffusion coefficients for organic solutes in aqueous solution, with average unsigned error of 0.137 ×10⁻⁵ cm²s⁻¹ [23].

When applying these protocols in drug development contexts, particular attention should be paid to the statistical reliability of diffusion coefficients. For solutes at infinite dilution, efficient sampling strategies that average MSD collected in multiple short-MD simulations often provide optimal convergence [23].

The analysis of diffusion regimes through MSD in molecular dynamics simulations provides a powerful framework for understanding molecular transport phenomena across diverse scientific domains. The three-regime model—ballistic, subdiffusive, and normal diffusion—offers molecular-level insights that connect material microstructure with macroscopic transport properties. The protocols outlined herein for simulation setup, MSD calculation, regime identification, and diffusion coefficient estimation provide researchers with a comprehensive methodology for extracting meaningful dynamical information from MD trajectories. As MD simulations continue to grow in temporal and spatial scale, applying these robust analysis techniques will remain essential for advancing our understanding of diffusion-driven processes in drug development, materials design, and biological systems.

Comparison of 1D, 2D, and 3D Diffusion Coefficient Calculations

In molecular dynamics (MD) research, the calculation of diffusion coefficients is fundamental for understanding mass transport, molecular interactions, and dynamic processes in biological and materials systems. The mean squared displacement (MSD), which measures the average squared distance particles travel over time, provides a direct pathway to determining these coefficients through the Einstein relation [11] [25]. This relation links microscopic particle motion to macroscopic diffusion properties, making it a cornerstone of MD analysis [28]. While the fundamental principles of diffusion are consistent across dimensionalities, the mathematical formulations and physical interpretations of diffusion coefficients differ significantly between one-dimensional (1D), two-dimensional (2D), and three-dimensional (3D) analyses. These differences arise from the varying degrees of freedom available for molecular motion in each dimension [29]. This application note details the theoretical foundations, practical calculation methods, and critical considerations for computing diffusion coefficients across different dimensional frameworks within the context of MD research, particularly relevant for drug development professionals studying molecular transport phenomena.

Theoretical Foundation: MSD and the Einstein Relation

The mean squared displacement is a measure of the deviation of a particle's position from a reference position over time, providing the most common measure of the spatial extent of random motion [11]. For a single particle, the MSD is defined as:

[MSD(t) = \langle | \mathbf{r}(t) - \mathbf{r}(0) |^2 \rangle]

where (\mathbf{r}(t)) is the position of the particle at time (t), and the angle brackets represent an ensemble average [11]. In practice, for MD simulations with multiple particles, the MSD is typically averaged over all particles of the same type:

[MSD(t) = \frac{1}{N} \sum{i=1}^{N} | \mathbf{r}i(t) - \mathbf{r}_i(0) |^2]

where (N) is the number of particles [11].

The connection between MSD and the diffusion coefficient (D) is established through the Einstein relation (Einstein-Smoluchowski equation), which states that for normal diffusion, the MSD grows linearly with time [25] [8]:

[\lim_{t \to \infty} MSD(t) = 2nDt]

where (n) is the dimensionality of the system (1, 2, or 3) [11] [8]. Thus, the diffusion coefficient can be extracted from the slope of the MSD versus time plot:

[D = \frac{1}{2n} \lim_{t \to \infty} \frac{d}{dt} MSD(t)]

For computational purposes, this is implemented by performing a linear regression on the MSD curve over an appropriate time interval where the relationship is linear [25].

Dimensionality in Diffusion Analysis

The dimensionality parameter (n) in the Einstein relation fundamentally affects the calculated diffusion coefficient value. This dependence arises from the number of independent degrees of freedom available for molecular motion in each dimensional context [29].

Table 1: Dimensional Characteristics in Diffusion Analysis

| Dimension | MSD Relation | Degrees of Freedom | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1D | (MSD = 2Dt) | 1 | Restricted diffusion in channels, pore transport |

| 2D | (MSD = 4Dt) | 2 | Membrane diffusion, surface adsorption, lateral transport |

| 3D | (MSD = 6Dt) | 3 | Bulk diffusion, solution-phase transport, protein dynamics |

In 3D space, molecules possess three independent translational degrees of freedom (along x, y, and z axes), and the mean squared displacement represents the sum of displacements in all three dimensions [11]. When a particle diffuses in 3D, the MSD is given by:

[MSD_{3D} = \langle x^2 \rangle + \langle y^2 \rangle + \langle z^2 \rangle = 6Dt]

since the mean squared displacement along each Cartesian coordinate equals (2Dt) [11] [29].

In 2D systems, molecular movement is restricted to a plane (e.g., membrane-associated proteins), and the MSD becomes:

[MSD_{2D} = \langle x^2 \rangle + \langle y^2 \rangle = 4Dt]

where motion is limited to two independent directions [29] [30].

In 1D systems, diffusion is constrained to a single pathway (e.g., molecular motion along polymers or through narrow channels), resulting in:

[MSD_{1D} = \langle x^2 \rangle = 2Dt]

with only one degree of freedom [29].

The differences in these relationships have significant implications. For the same diffusion coefficient (D), the time (t) required for a molecule to travel a Euclidean distance (r) follows (t = \frac{r^2}{4D}) in 2D versus (t = \frac{r^2}{6D}) in 3D, meaning diffusion appears slower in lower-dimensional systems when analyzed with dimensional relationships [29]. This occurs because in higher dimensions, particles have more pathways to explore, leading to more efficient exploration of space [29].

Practical Calculation Methods and Protocols

MSD Calculation from MD Trajectories

The accurate computation of MSD from molecular dynamics trajectories requires careful attention to several technical considerations. The fundamental equation for MSD calculation with time lags is:

[\overline{\delta^2(n)} = \frac{1}{N-n}\sum{i=1}^{N-n} (\vec{r}{i+n} - \vec{r}_i)^2]

where (n) is the lag time in units of frames, (N) is the total number of frames, and (\vec{r}_i) is the position at frame (i) [11]. For continuous time series, this becomes:

[\overline{\delta^2(\Delta)} = \frac{1}{T-\Delta}\int_0^{T-\Delta} [r(t+\Delta) - r(t)]^2 dt]

where (T) is the total simulation time and (\Delta) is the lag time [11].

A critical requirement for accurate MSD calculation is the use of unwrapped coordinates rather than wrapped coordinates. When atoms cross periodic boundaries, they must not be wrapped back into the primary simulation cell, as this would introduce artificial discontinuities in the trajectory [25]. Various simulation packages provide utilities for this conversion; for example, in GROMACS, this can be achieved using gmx trjconv with the -pbc nojump flag [25] [5].

The memory requirements for MSD computation can be intensive due to O(N²) scaling with respect to trajectory length. Implementation of Fast Fourier Transform (FFT)-based algorithms can improve this to O(N log N) scaling [25]. The tidynamics Python package implements such an FFT-based approach for efficient MSD calculation.

Diffusion Coefficient Extraction Protocol

Trajectory Preparation: Ensure trajectories contain unwrapped coordinates and are properly aligned. Remove rotational and translational motion if studying internal dynamics.

MSD Calculation: Compute the MSD for the appropriate dimensional analysis (1D, 2D, or 3D). Most software tools allow specification of the msd_type parameter (e.g., 'x', 'xy', or 'xyz') [25].

Linear Region Identification: Plot MSD versus time on a log-log scale to identify the linear regime, which should exhibit a slope of 1 [25]. Exclude the initial ballistic regime (where particles move quasi-freely before collisions) and the long-time plateau region where statistics are poor.

Linear Regression: Perform least-squares fitting of MSD versus time in the linear region:

[ \text{slope} = \frac{\Delta MSD}{\Delta t} ]

The diffusion coefficient is then calculated as:

[ D = \frac{\text{slope}}{2n} ]

where (n) is the dimensionality [25].

Error Estimation: Compute error estimates using block averaging or by dividing the trajectory into segments and calculating the standard deviation of D across segments [5].

Software Implementation

Table 2: Software Tools for Diffusion Coefficient Calculation

| Software | MSD Command | Key Parameters | Dimensional Options |

|---|---|---|---|

| GROMACS | gmx msd |

-type, -lateral, -beginfit, -endfit |

x, y, z, xy, yz, xz, xyz [5] |

| MDAnalysis | EinsteinMSD() |

msd_type, fft |

x, y, z, xy, yz, xz, xyz [25] |

| AMS | MD Properties → MSD | Atoms, Max MSD Frame | User-defined atom selection [31] |

GROMACS Implementation Example:

This command calculates the 1D diffusion coefficient along the z-axis, fitting the MSD between 100 ps and 1000 ps [5].

MDAnalysis Implementation Example:

This Python code calculates the 3D diffusion coefficient for lithium ions using FFT acceleration [25].

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Diffusion Analysis

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| GROMACS [5] | Molecular dynamics simulator with built-in MSD analysis | Production MD simulations and diffusion analysis |

| MDAnalysis [25] | Python toolkit for trajectory analysis | Flexible, scriptable analysis of MD trajectories |

| AMS [31] | Software platform with ReaxFF engine | Reactive force field simulations for complex materials |

| tidynamics [25] | Python package with FFT-based MSD | Accelerated MSD computation for long trajectories |

| Unwrapped trajectories | Corrected coordinates across periodic boundaries | Essential for accurate MSD calculation [25] |

| ReaxFF force field [31] | Reactive force field for bond formation/breaking | Diffusion in reactive systems (e.g., battery materials) |

| GAFF force field [23] | General Amber Force Field | Diffusion of organic molecules in solution |

Methodological Considerations and Best Practices

Finite-Size Effects and System Preparation

Diffusion coefficients calculated from MD simulations exhibit finite-size effects, where the computed value depends on the simulation box size [31] [23]. This dependence arises from hydrodynamic interactions propagating through periodic boundary conditions. Typically, simulations should be performed for progressively larger supercells, with extrapolation to the "infinite supercell" limit [31]. System preparation should include:

- Proper equilibration: Ensure the system reaches equilibrium before production runs.

- Simulated annealing: For amorphous systems, create realistic structures through heating and rapid cool-down protocols [31].

- Adequate sampling: Use multiple independent trajectories or extended simulation times to improve statistics [23].

Dimensionality Selection Criteria

Choosing the appropriate dimensionality for analysis requires careful consideration of the physical system:

- 3D analysis is appropriate for bulk diffusion in solutions, gases, or amorphous solids [31] [23].

- 2D analysis should be used for surface diffusion, membrane-bound molecules, or layered materials [32] [30].

- 1D analysis applies to diffusion through narrow channels, along polymers, or in other highly constrained environments [29].

In reduced-dimension models, molecular movement is restricted to the focal plane, which introduces a zero-flux assumption that may not hold for all systems [30]. This assumption is valid only when a mesh can be constructed such that molecular flux through the focal plane is balanced.

Validation and Error Analysis

- Linear fit validation: Ensure the MSD plot shows a clear linear regime with sufficient sampling.

- Convergence testing: Verify that extending simulation time does not significantly alter the computed diffusion coefficient.

- Multiple trajectory analysis: Use several independent trajectories to estimate statistical uncertainty.

- Alternative method comparison: Compare results with Green-Kubo integration of the velocity autocorrelation function [31]:

[D = \frac{1}{3}\int_0^{\infty} \langle \mathbf{v}(0) \cdot \mathbf{v}(t) \rangle dt]

The accurate calculation of diffusion coefficients from molecular dynamics simulations requires careful attention to dimensional considerations, proper trajectory processing, and appropriate statistical analysis. The fundamental relationship (D = \frac{\text{slope}}{2n}) highlights the critical importance of correctly specifying dimensionality (n) in the Einstein relation, with values of 1, 2, and 3 corresponding to 1D, 2D, and 3D diffusion, respectively. Researchers must select the appropriate dimensional framework based on the physical constraints of their system, recognizing that reduced-dimension models introduce specific assumptions about molecular motion. By implementing the protocols and considerations outlined in this application note—including the use of unwrapped trajectories, identification of appropriate linear MSD regimes, correction for finite-size effects, and comprehensive validation—researchers can obtain reliable, reproducible diffusion coefficients that provide fundamental insights into molecular transport phenomena across diverse applications in materials science, drug development, and biological research.

The Velocity Autocorrelation Function (VACF) is a fundamental time-dependent correlation function in molecular dynamics (MD) that reveals the underlying nature of dynamical processes operating in molecular systems. In the context of calculating diffusion coefficients, the VACF provides a powerful alternative to the more common mean-squared displacement (MSD) approach, with distinct theoretical advantages for certain systems [33].

The VACF measures how a particle's velocity correlates with itself over time, encapsulating extensive information about a fluid's molecular-structural and hydrodynamic properties [34]. Mathematically, the VACF is defined as the dot product of the velocity vector of a particle at time ( t ) with its velocity at time ( t=0 ), averaged over all particles and initial times [33]:

[ Cv(t) = \langle \mathbf{v}i(t0) \cdot \mathbf{v}i(t_0 + t) \rangle ]

where ( \mathbf{v}_i(t) ) represents the velocity of particle ( i ) at time ( t ), and the angle brackets denote averaging over all particles and time origins [33].

Table 1: Interpretation of VACF Behavior in Different Systems

| System Type | VACF Behavior | Physical Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Ideal Gas | Near-horizontal line | Very weak forces acting; velocities barely change |

| Weakly Interacting Gas | Simple exponential decay | Weak forces gradually destroy velocity correlation |

| Liquid | One very damped oscillation before decaying to zero | Collisional behavior before diffusion dominates |

| Solid | Strong oscillations decaying in time | Atoms oscillate in stable positions with disruptions |

Theoretical Foundation: Connecting VACF to Diffusion

The connection between VACF and diffusion coefficients is established through the Green-Kubo relations, which relate time-integrated correlation functions to transport coefficients [33]. Specifically, the diffusion coefficient ( D ) can be obtained from the integral of the VACF:

[ D = \frac{1}{3} \int_0^{\infty} \langle \mathbf{v}(0) \cdot \mathbf{v}(t) \rangle dt ]

This relationship emerges from the connection between velocity correlation and particle displacement [33]. The factor of ( 1/3 ) accounts for the three spatial dimensions in an isotropic system.

The VACF approach provides significant theoretical insights compared to the MSD method. While MSD analyzes spatial displacement (( \langle r^2(t) \rangle )), VACF probes the velocity memory of particles, offering a more direct window into the microscopic dynamics governing diffusion [33] [34]. The VACF captures how interatomic forces cause particles to "forget" their initial velocities, a process called decorrelation, with the rate of this decorrelation directly determining the diffusion coefficient [33].

Figure 1: VACF Analysis Workflow for Diffusion Coefficient Calculation

Quantitative Comparison: VACF vs. MSD Approaches

Table 2: Method Comparison for Diffusion Coefficient Calculation

| Parameter | VACF Approach | MSD Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Quantity | Velocity correlation over time | Spatial displacement over time |

| Key Formula | ( D = \frac{1}{3} \int_0^{\infty} \langle \mathbf{v}(0) \cdot \mathbf{v}(t) \rangle dt ) | ( D = \frac{1}{6} \lim_{t \to \infty} \frac{d}{dt} \langle \mathbf{r}^2(t) \rangle ) |

| Convergence | Faster for some systems, but sensitive to statistics | Generally smoother, but requires longer simulations |

| Ballistic Region | Includes ballistic region automatically | Must exclude initial ballistic region (10% typically) |

| Software Implementation | compute vacf (LAMMPS), gmx velacc (GROMACS), PLAMS (AMS) |

compute msd (LAMMPS), gmx msd (GROMACS) |

| Theoretical Foundation | Green-Kubo relations | Einstein relation |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol 1: VACF Calculation in LAMMPS

The LAMMPS MD package provides built-in functionality for VACF calculation through the compute vacf command [20]:

Define VACF Computation: Implement the command

compute vacf all vacfto calculate the velocity autocorrelation function for all atoms.Data Collection: Use the

fix vectorcommand to accumulate instantaneous VACF values in a vector for analysis.Time Integration: Employ the

variable trapfunction to perform time integration of the VACF, as required by the Green-Kubo relation.Diffusion Coefficient Extraction: Calculate the diffusion coefficient using the integrated VACF value with proper normalization [20].

Protocol 2: VACF Analysis with AMS/PLAMS

The Amsterdam Modeling Suite (AMS) provides Python-based analysis through PLAMS for post-processing MD trajectories [35]:

This protocol extracts the VACF directly from MD trajectories and computes the time-dependent diffusion coefficient through integration [35].

Protocol 3: VACF in GROMACS

For GROMACS users, VACF calculation follows this procedure [36]:

Trajectory Production: Run MD simulation with frequent velocity output using

nstvout = 10or similar frequency.VACF Calculation: Use

gmx velaccwith the-molflag for molecular VACF calculation.Integration: Integrate the VACF using

gmx analyzeand divide by 3 to obtain the diffusion coefficient.Unit Considerations: Note that GROMACS VACF output typically uses units of nm²/ps² [36].

Research Reagent Solutions: Computational Tools

Table 3: Essential Software Tools for VACF Analysis

| Software/Tool | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| LAMMPS | compute vacf command |

General MD simulations of various systems |

| GROMACS | gmx velacc utility |

Biomolecular simulations in solution |

| AMS/PLAMS | get_velocity_acf() method |

Materials science and drug discovery applications |

| VASP | Velocity extraction from MD | Ab initio MD for electronic structure effects |

| NumPy/SciPy | Numerical integration and Fourier analysis | Custom analysis scripts and method development |

Advanced Applications and Extensions

Power Spectrum from VACF

The VACF can be Fourier transformed to project out the underlying frequencies of molecular processes, which is closely related to the infra-red spectrum of the system [33]. The implementation in AMS demonstrates this approach [35]:

This power spectrum analysis provides information about vibrational modes and can identify characteristic frequencies in the system [35].

Hydrodynamic Theory and Molecular Interpretation

Advanced hydrodynamic theories of the VACF bridge continuum hydrodynamical behavior and discrete-particle kinetics [34]. The VACF can be interpreted as a superposition of products of quasinormal hydrodynamic modes weighted with the spatial velocity power spectrum, providing a physical bridge between molecular and continuum descriptions [34].

Figure 2: VACF Theoretical Relationships and Experimental Connections

Practical Considerations and Troubleshooting

Sampling and Statistical Precision

VACF analysis requires adequate sampling for statistical precision [36] [37]:

- Velocity Output Frequency: Save velocities frequently enough to resolve the fastest dynamics of interest (typically every 10-50 steps) [36].

- Simulation Length: The simulation should cover at least "two slowest phonon cycles" or the decay time of the normalized VACF to zero [37].

- Averaging: Average over multiple independent trajectories or time origins to improve statistics [33] [37].

Common Issues and Solutions

- Discrepancies with MSD Results: Differences between VACF and MSD diffusion coefficients may arise from insufficient sampling, different treatment of the ballistic region, or unit conversion errors [36].

- Noise in VACF: For noisy VACF, increase sampling statistics or apply appropriate filtering before integration.

- Non-Decaying VACF: If VACF doesn't decay to zero, the simulation may be too short, or the system may have non-diffusive components.

The Velocity Autocorrelation Function approach provides a powerful theoretical framework for calculating diffusion coefficients in molecular dynamics simulations. Its foundation in Green-Kubo relations offers a fundamentally sound methodology that complements the more commonly used MSD approach. For researchers in drug development and materials science, the VACF method not only yields diffusion coefficients but also provides additional insights into system dynamics through frequency analysis and connections to spectroscopic observables. When implemented with careful attention to sampling requirements and statistical precision, the VACF approach constitutes a robust alternative for transport property calculation in MD research.

Practical Implementation: Step-by-Step MSD Calculation and Analysis Workflow

Within the broader thesis of calculating diffusion coefficients from molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, the reliability of results is fundamentally constrained by the quality of the generated trajectory. The mean squared displacement (MSD) analysis, which leverages the Einstein relation to compute diffusion coefficients (D = MSD/(6t) for 3D diffusion), is particularly sensitive to the parameters of the MD simulation [31] [20] [38]. Inadequate simulation duration or improper sampling can lead to results plagued by poor statistics, rendering subsequent analysis meaningless [38]. This application note details the critical trajectory requirements—simulation duration, sampling frequency, and statistical sampling—to ensure the accurate and statistically significant calculation of diffusion coefficients from MD simulations, with a focus on applications in materials science and drug development.

Core Trajectory Parameters for Diffusion Studies

The accuracy of diffusion coefficients calculated via MSD is contingent upon three interdependent parameters: the total simulation duration, the frequency of trajectory sampling, and the subsequent statistical treatment of the data. These parameters must be chosen to ensure sufficient sampling of diffusion events and a linear regime in the MSD plot.

Simulation Duration and Time Scales

The total physical time simulated must be long enough to capture a sufficient number of diffusion events (ion or molecule hops) to achieve statistical significance [38]. Ab initio MD (AIMD) simulations are often limited to sub-nanosecond timescales, which can lead to high variance in results if too few events are sampled [38]. For classical MD, simulations must extend beyond the ballistic regime, where particle motion is non-diffusive, and into the linear MSD regime.

Table 1: Recommended Simulation Parameters from Various MD Platforms

| Parameter | AIMD (from [38]) | Classical MD (GROMACS) [31] [5] | Protocol for Proteins [39] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Simulation Duration | Should be long enough to sample an adequate number of diffusion events; often picoseconds to nanoseconds. | 100,000+ production steps (e.g., 250 ps for 0.25 fs/step, plus equilibration) [31] | Setup of multiple independent systems; production run cycles (e.g., 10 ns/cycle) [40] |

| Integration Time Step (dt) | Typically ~1 fs (implied) | 0.25 fs [31] to 1-2 fs (common for classical MD) | Implied use of standard GROMACS time steps (e.g., 2 fs) [39] |

| Sampling Frequency | Not specified, but must be frequent enough to resolve diffusion. | Every 5 steps (e.g., 1.25 fs for dt=0.25 fs) [31] | Use of grompp to preprocess; trajectory output frequency must be set. [39] |

| Key Consideration | Statistical variance is a direct function of the number of observed diffusion events. [38] | Finite-size effects require extrapolation to the "infinite supercell" limit for accurate D. [31] | System must be neutralized with counterions and properly solvated. [39] |

Sampling Frequency and Trajectory Output

The frequency at which atomic coordinates are written to the trajectory file (the "sample frequency" or "nstxout") controls the temporal resolution of the subsequent analysis. A higher sampling frequency is required for methods that involve the velocity autocorrelation function (VACF), as it requires atomic velocities [31]. For MSD analysis, a lower frequency can be used, resulting in smaller trajectory files, provided the resolution is still sufficient to capture the relevant dynamics [31]. A practical guideline is to ensure the time between saved frames is much shorter than the characteristic time scale of the diffusion process being studied.

Statistical Sampling and MSD Analysis

The MSD is calculated by averaging the squared displacements over many time origins along the trajectory [38]. The statistical quality of the MSD curve degrades at long lag times (Δt) because fewer time intervals are available for averaging [41]. The gmx msd tool offers the -trestart option to increase the number of reference time origins, improving statistics at the cost of increased computation [5] [41]. The -maxtau option can cap the maximum time delta for analysis to avoid using poorly sampled segments of the MSD curve [5].

Experimental Protocol for a Diffusion MD Simulation

The following protocol, adapted from established procedures for simulating proteins and battery materials, outlines the key steps for setting up and running an MD simulation for the purpose of calculating diffusion coefficients [31] [39].

System Setup and Equilibration

- Obtain and Prepare Initial Coordinates: Acquire the initial structure in PDB format. For proteins, visual inspection with a tool like RasMol is recommended. Use

pdb2gmxto convert the structure to a GROMACS-compatible format (.gro), generate the topology, and select an appropriate force field (e.g.,charmm36orffG53a7). - Define the Simulation Box: Use

editconfto place the solute in the center of a box (e.g., cubic, dodecahedron) with a margin of at least 1.0 nm from the solute to its periphery. - Solvate the System: Use

solvateto fill the box with water molecules (e.g., TIP3P, TIP4P). The topology file is automatically updated to include water. - Add Ions: Use

gromppto preprocess the system with a parameter file (.mdp) for energy minimization. Then, usegenionto add counterions to neutralize the system's net charge and, optionally, salt to a physiological concentration (e.g., 0.15 M NaCl or KCl). - Energy Minimization: Run an energy minimization (e.g., using the steepest descent algorithm) to remove any steric clashes and relax the structure.

- Equilibration: Perform equilibration runs in the NVT (constant Number of particles, Volume, and Temperature) and NPT (constant Number of particles, Pressure, and Temperature) ensembles to stabilize the system's temperature and density at the desired conditions.

Production Simulation and Analysis

- Run Production MD: Execute a production MD simulation using the parameters established in Table 1. Ensure the simulation is long enough and that coordinates (and optionally velocities) are written at an appropriate frequency for analysis.

- Calculate the MSD: Use the

gmx msdcommand. A typical command is:gmx msd -f production.xtc -s production.tpr -o msd.xvg -type atomic -trestart 50 -beginfit 1000 -endfit 5000-trestart: Sets the time (ps) between new reference points for the MSD calculation, improving statistics.-beginfitand-endfit: Define the temporal region (ps) for the linear fit to the MSD curve to compute D.

- Determine the Diffusion Coefficient: The diffusion coefficient is calculated from the slope of the linear region of the MSD vs. time plot as ( D = \frac{\text{slope}(MSD)}{2d} ), where ( d ) is the dimensionality of the diffusion.

Figure 1: MD Workflow for Diffusion Coefficient Calculation. The diagram outlines the key stages, from initial structure preparation to production simulation and analysis, highlighting the critical trajectory parameters that directly impact the reliability of the calculated diffusion coefficient.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Software Solutions

| Item | Function in Diffusion MD Simulations |

|---|---|

| GROMACS MD Suite | An open-source, robust software package for performing MD simulations and subsequent analysis, including MSD calculation via the gmx msd module. [5] [39] |

| Force Fields (e.g., CHARMM36, AMBER) | A set of empirical parameters that describe the potential energy of a system of particles; critical for modeling interatomic forces accurately during the simulation. [39] [40] |

| Visualization Tools (e.g., RasMol, VMD) | Software for visual inspection of the initial protein structure and rendered trajectories to check for stability and artifacts. [39] |

| Parameter File (.mdp) | A text file containing all the run parameters for a GROMACS simulation (e.g., integrator, temperature, pressure coupling, timestep). [42] [39] |

Analysis Tools (e.g., gmx msd, gmx vacf) |

Integrated GROMACS tools to compute the Mean Squared Displacement (MSD) and Velocity Autocorrelation Function (VACF), from which the diffusion coefficient is derived. [31] [5] [20] |

Calculating statistically robust diffusion coefficients from MD simulations requires careful attention to trajectory parameters. The simulation must be sufficiently long to capture the linear regime of the MSD plot and sample enough diffusion events. The trajectory output frequency must be high enough to resolve the dynamics of interest, and the analysis must use appropriate statistical sampling techniques. Adhering to the protocols and parameters outlined in this note provides a foundation for obtaining reliable diffusional properties, which are critical for validating models against experimental data and making predictive assessments in fields ranging from battery material design to drug development.

Within the broader context of calculating diffusion coefficients from molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, the Mean Squared Displacement (MSD) analysis stands as a cornerstone technique due to its direct relationship with the self-diffusivity via the Einstein relation [8] [3]. The accuracy of the computed diffusion coefficient, however, is not inherent to the data alone but is highly dependent on the analysis protocol, specifically the choice of averaging techniques and the selection of time origins for the MSD calculation [43]. This protocol provides a detailed guide for implementing robust MSD analysis, focusing on these two critical aspects to ensure statistically sound and reproducible results for researchers in computational chemistry, biophysics, and materials science.

Theoretical Foundation

The MSD is a fundamental measure of particle mobility. For a three-dimensional system, the MSD at a lag time ( \tau ) is defined as: [ MSD(\tau) = \langle | \vec{r}(t + \tau) - \vec{r}(t) |^2 \rangle ] where ( \vec{r}(t) ) is the position of a particle at time ( t ), and ( \langle \cdot \rangle ) denotes an averaging procedure [3]. The core of the analysis lies in the Einstein relation, which connects the MSD to the diffusion coefficient ( D ): [ D = \frac{1}{2d} \lim_{\tau \to \infty} \frac{d}{d\tau} MSD(\tau) ] where ( d ) is the dimensionality of the analysis [3]. In practice, for a normal diffusive process in three dimensions, this simplifies to ( D = \frac{1}{6} \times \text{slope}(MSD(\tau)) ) [31]. A crucial prerequisite for a valid analysis is identifying a linear segment in the MSD plot, which signifies the normal diffusive regime, while excluding the short-time ballistic regime and the long-time poorly averaged data [3].

Critical Implementation Parameters

Averaging Techniques

The choice of averaging technique directly impacts the statistical robustness of the MSD and the subsequent diffusion coefficient. The table below summarizes the primary methods.

Table 1: Comparison of MSD Averaging Techniques

| Averaging Technique | Description | Advantages | Limitations | Common Implementation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ensemble-Averaged MSD | Averages the squared displacements over all particles in a group (e.g., all atoms of a given type) for each lag time ( \tau ) [31]. | Improves statistical power by leveraging data from all equivalent particles; standard for homogeneous systems. | Assumes all particles have identical diffusion characteristics; obscures heterogeneity [44]. | MSD = msd.EinsteinMSD(u, select='type Li', msd_type='xyz').run() [3]. |

| Time-Averaged MSD | Averages the squared displacements over multiple time origins ( t_0 ) along a single particle's trajectory [3]. | Better for single-particle trajectories; necessary for analyzing heterogeneous or anomalous diffusion. | Can be noisy for individual trajectories; requires long trajectories for good statistics. | The "windowed" MSD averages over all possible lag times ( \tau \le \tau_{max} ) [3]. |

| Averaged over Replicates | Computes the MSD for each particle across multiple, independent simulation replicates and then averages the results [3]. | Provides the most statistically reliable estimate and a true measure of uncertainty. | Computationally expensive, as it requires running multiple simulations. | average_msd = np.mean(combined_msds, axis=1) where combined_msds contains data from multiple runs [3]. |

Time Origin Selection and Fitting Parameters

The selection of time origins for the MSD calculation and the linear regression window are critical for an accurate diffusion coefficient. The gmx msd program from GROMACS offers a practical implementation of these concepts [5].

Table 2: Key Parameters for MSD Fitting in GROMACS gmx msd

| Parameter | Default Value | Description | Recommendation |

|---|---|---|---|