Bridging the Gap: A Practical Guide to Validating MD-Predicted Protein Folding Pathways

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to validate molecular dynamics (MD) simulations of protein folding pathways against experimental data.

Bridging the Gap: A Practical Guide to Validating MD-Predicted Protein Folding Pathways

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to validate molecular dynamics (MD) simulations of protein folding pathways against experimental data. It covers foundational concepts, from the fundamental challenges of the protein folding problem revealed by the Levinthal paradox to the revolutionary impact of AI-based structure prediction tools like AlphaFold. The content explores integrated methodological approaches that combine machine learning models with MD simulations to explore conformational ensembles, details common pitfalls in simulation accuracy and sampling, and establishes robust protocols for quantitative comparison with experimental observables. By synthesizing insights across computational and experimental disciplines, this guide aims to enhance confidence in MD-predicted folding mechanisms for critical applications in biomedical research and therapeutic development.

The Protein Folding Landscape: From Anfinsen's Dogma to AI Revolution

In 1969, Cyrus Levinthal posed a fundamental challenge to our understanding of protein folding: if a protein were to fold by randomly sampling all possible conformational states, it would require astronomical timescales far exceeding the age of the universe, yet proteins typically fold in milliseconds to seconds [1]. This discrepancy between theoretical calculation and experimental observation became known as Levinthal's paradox. The resolution of this paradox lies not in faster conformational sampling, but in the nature of the folding process itself—proteins do not fold by exhaustive random search but follow biased, energetically favorable pathways guided by a funnel-shaped energy landscape [2].

The energy landscape theory revolutionized our understanding of protein folding by introducing the concept of a rugged funnel where the folding process is directed toward the native state by decreasing free energy and increasing native-like contacts [2] [3]. This theoretical framework has profound implications for modern structural biology, particularly in validating molecular dynamics (MD)-predicted folding pathways with experimental data. As we move beyond static structure prediction toward dynamic conformational ensembles, integrating computational approaches with experimental validation becomes crucial for understanding protein function and dysfunction in disease states [4].

Theoretical Framework: From Paradox to Funnel

The Levinthal Paradox and Its Implications

Levinthal's paradox highlights a fundamental mathematical contradiction: for a typical protein of 100 amino acids, the number of possible conformations is astronomically large (~3¹⁰⁰), and random sampling would require timescales orders of magnitude longer than observed folding times [2] [1]. This paradox initially suggested that protein folding represented an unsolvable search problem, potentially requiring new physical laws for its explanation [2].

The critical insight for resolving this paradox came from recognizing that proteins are not random heteropolymers. Instead, natural protein sequences have been evolutionarily selected for folding efficiency and minimal frustration [2]. As Bryngelson and Wolynes established, such minimally frustrated sequences exhibit energy landscapes with two key characteristics: a folding transition temperature (TF) and a glass transition temperature (Tg). Easy-to-fold sequences maintain a high TF/Tg ratio, enabling efficient folding without kinetic trapping [2].

Energy Landscape Theory and the Folding Funnel

Energy landscape theory conceptualizes protein folding as navigation on a rugged funnel-shaped landscape [2] [3]. This landscape is "funneled" because its overall slope biases the conformational search toward the native state, while "rugged" due to the presence of metastable intermediates and kinetic barriers [3].

The funnel metaphor captures several essential features of protein folding:

- Global bias: The overall downward slope represents the decreasing free energy as the protein approaches its native state

- Ruggedness: Local minima and barriers correspond to metastable states and folding intermediates

- Progressive narrowing: The funnel narrows toward the native state, reflecting the decrease in conformational entropy

- Multiplicity of pathways: Unlike specific stepwise chemical reactions, folding can proceed through multiple dominant routes [2]

Quantitative studies have confirmed this funneled landscape paradigm. For ordered proteins like HP-35 and WW domain, the landscape slope is approximately -50 kcal/mol, meaning free energy decreases by ~5 kcal/mol upon formation of 10% native contacts. In contrast, intrinsically disordered proteins like pKID exhibit shallower landscapes (slope of -24 kcal/mol), explaining their disorder in isolation. Upon binding to their partners, their landscapes become significantly steeper (slope of -54 kcal/mol), enabling folding [5].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Protein Folding Energy Landscapes

| Characteristic | Ordered Proteins | Intrinsically Disordered Proteins | Minimally Frustrated Sequences |

|---|---|---|---|

| Landscape Slope | ~ -50 kcal/mol [5] | ~ -24 kcal/mol (free); -54 kcal/mol (bound) [5] | Steeply funneled |

| Frustration Level | Minimal | Varies | Minimal by evolutionary design |

| Metastable States | Limited | Multiple | Few deep traps |

| Folding Timescale | Microseconds to seconds | Context-dependent | Optimized for rapid folding |

| Response to Mutations | Often destabilizing | Can alter binding-induced folding | Sensitive to conservative changes |

Computational Methodologies for Exploring Folding Landscapes

Molecular Dynamics Simulations

Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations provide an atomistic approach to studying protein folding by numerically solving Newton's equations of motion for all atoms in the system. Conventional all-atom MD with explicit solvent offers high accuracy but comes at extreme computational cost, limiting its application to relatively small proteins and shorter timescales [6].

Advanced sampling techniques have been developed to overcome these limitations:

- Parallel Tempering/Replica Exchange: Simultaneously runs simulations at multiple temperatures, enabling enhanced conformational sampling [6]

- Metadynamics and OPES: Bias simulations along collective variables (CVs) to accelerate rare events like folding/unfolding transitions [3]

- Variational Force-Matching: Uses machine learning to develop coarse-grained force fields that maintain near-atomistic accuracy [6]

Recent work has demonstrated the critical importance of designing effective CVs that capture slow degrees of freedom relevant to folding. Bioinspired CVs that explicitly distinguish protein-protein from protein-water hydrogen bonds and account for side-chain packing can significantly enhance state resolution and reduce degeneracy problems that plague traditional CVs [3].

Machine-Learned Coarse-Grained Models

The development of transferable coarse-grained (CG) models represents a major advancement for simulating folding processes. By combining deep learning with diverse training sets of all-atom simulations, researchers have developed bottom-up CG force fields with chemical transferability that can extrapolate to sequences not used during parameterization [6].

These machine-learned CG models successfully predict metastable states of folded, unfolded, and intermediate structures, fluctuations of intrinsically disordered proteins, and relative folding free energies of protein mutants while being several orders of magnitude faster than all-atom models [6]. For example, CGSchNet demonstrates remarkable transferability, accurately reproducing folding landscapes for proteins with low (<40%) sequence similarity to training examples, indicating that the model learns to represent effective physical interactions rather than merely memorizing structural templates [6].

Table 2: Comparison of Protein Folding Simulation Methods

| Method | Spatial Resolution | Timescale Accessible | Key Applications | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All-Atom MD | Atomic | Nanoseconds to milliseconds | Folding mechanisms, atomistic details | Extreme computational cost |

| Coarse-Grained MD | 3-5 heavy atoms per bead | Microseconds to seconds | Folding thermodynamics, larger proteins | Loss of atomic detail |

| Machine-Learned CG | Coarse-grained (Cα or backbone) | Microseconds to seconds | Metastable states, folding free energies | Training data dependency |

| Enhanced Sampling | Atomic or coarse-grained | Effectively extends accessible times | Free energy landscapes, rare events | Dependent on collective variables |

| Go̅ Models | Cα or backbone | Milliseconds and beyond | Folding principles, large systems | Native-centric, limited for misfolding |

Cotranslational Folding Simulations

The Generalized Protein Cotranslational Folding (GPCTF) simulation framework represents a significant innovation by modeling ribosomal exit tunnels and translation processes. This approach reveals fundamental differences between cotranslational folding in vivo and free folding in vitro, showing that CTF provides more helix-rich initial structures with fewer nonnative long-range contacts compared to FF [7].

GPCTF simulations demonstrate that while subsequent folding follows similar pathways as free folding, the distribution among these pathways is modulated by translation speed. This pathway regulation mechanism helps reconcile discrepancies in previous experimental results and offers significant insights into protein folding processes in physiological contexts [7].

Experimental Validation of Predicted Folding Pathways

Biophysical Techniques for Monitoring Folding

Experimental validation of computationally predicted folding pathways employs multiple biophysical techniques that probe different aspects of protein structure and dynamics:

- Hydrogen-Deuterium Exchange Mass Spectrometry: Measures solvent accessibility and dynamics by tracking deuterium incorporation, providing insights into folding intermediates and protected regions [4]

- Single-Molecule Fluorescence Resonance Energy Transfer (smFRET): Monitors intra-molecular distances and conformational changes in real-time, enabling detection of transient intermediates [4]

- Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectroscopy: Provides atomic-resolution information on structure and dynamics, particularly powerful for characterizing folding intermediates and residual structure in disordered states [4] [5]

- Circular Dichroism (CD) Spectroscopy: Tracks secondary structure formation during folding by measuring differential absorption of left- and right-circularly polarized light [1]

These techniques generate complementary data that collectively constrain possible folding mechanisms and enable validation of MD-predicted pathways. For example, NMR measurements of protection factors can directly validate predicted hydrogen bonding patterns in folding intermediates, while smFRET time trajectories can confirm predicted folding routes and rates.

Quantitative Landscape Mapping

Advanced experimental approaches now enable quantitative mapping of folding energy landscapes. By combining site-directed mutagenesis with phi-value analysis, researchers can probe the structure of transition states and folding intermediates. Phi-values between 0 and 1 indicate the extent to which a residue's native interactions are formed in the transition state, providing crucial information about folding mechanisms [7].

Recent methodological developments allow explicit construction of free energy landscapes from simulation data. The reduced landscape f(Q) is obtained by averaging the free energy f(r) = Eu(r) + Gsolv(r) over configurations with specific values of an order parameter Q (typically the fraction of native contacts) [5]. This approach distinguishes between the globally funneled landscape f(Q) and the free energy profile F(Q) = -k_BT log P(Q), which includes configurational entropy effects and typically shows unfolded and folded minima separated by a barrier [5].

Case Studies: Successes and Limitations

Mini-Protein Folding Landscapes

Comprehensive studies on mini-proteins like Chignolin and TRP-cage have provided detailed validation of energy landscape principles. Enhanced sampling simulations using specialized collective variables that capture hydrogen bonding and side-chain packing have successfully resolved complex free-energy landscapes and revealed critical intermediates such as the dry molten globule state [3].

These studies demonstrate that convergent folding pathways emerge naturally from the energy landscape, with proteins incrementally forming native contacts through stochastic search. The dry molten globule intermediate, characterized by substantial native-like secondary structure but incomplete side-chain packing and dehydration, appears to be a general feature of the folding process for many small proteins [3].

Multi-Domain Proteins and Prediction Challenges

Despite significant advances, substantial challenges remain, particularly for multi-domain proteins and systems with limited evolutionary information. A case study on the SAML protein revealed severe deviations between experimental structures and AI predictions, with positional divergences exceeding 30 Å and overall RMSD of 7.7 Å [8].

These discrepancies were particularly pronounced in the relative orientation of protein domains, which could not be resolved even with customized searches using low MSA depth, different random seeds, and multiple recycling steps [8]. This highlights current limitations in capturing inter-domain interactions and conformational flexibility, especially when experimental structures represent specific conformations stabilized by crystallization conditions that predictions may not account for [8].

Cotranslational vs. Free Folding

Systematic comparison of cotranslational folding (CTF) and free folding (FF) using the GPCTF framework has revealed fundamental differences in folding mechanisms. Simulations totaling over 8 milliseconds across three proteins with different topologies revealed that CTF produces nascent peptides with more helix-rich structures and fewer long-range contacts upon expulsion from the ribosomal exit tunnel compared to FF [7].

While subsequent folding follows similar pathways, their relative probabilities are modulated by translation speed, demonstrating a pathway regulation mechanism inherent to cotranslational folding. This provides a mechanistic basis for understanding how synonymous codon substitutions that alter translation speed can impact protein structure without changing the amino acid sequence [7].

Research Toolkit: Essential Methods and Reagents

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Protein Folding Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Application | Key Features | Example Uses |

|---|---|---|---|

| GROMACS [4] | Molecular dynamics simulation package | High performance, versatile | Folding/unfolding simulations |

| AMBER [4] | Molecular dynamics software | Specialized for biomolecules | Detailed folding pathway analysis |

| CHARMM [4] | MD simulation program | Comprehensive force fields | Free energy calculations |

| OpenMM [4] | Toolkit for MD simulation | GPU acceleration, customizability | Enhanced sampling methods |

| ATLAS Database [4] | MD simulation database | ~2000 proteins, diverse structural space | Reference dynamics data |

| GPCRmd [4] | Specialized MD database | GPCR-focused, 705 simulations | Membrane protein folding |

| AlphaFold2 [4] | Structure prediction | High accuracy static structures | Initial coordinates for MD |

| CoDNaS 2.0 [4] | Conformational diversity database | Native state ensembles | Conformational variability studies |

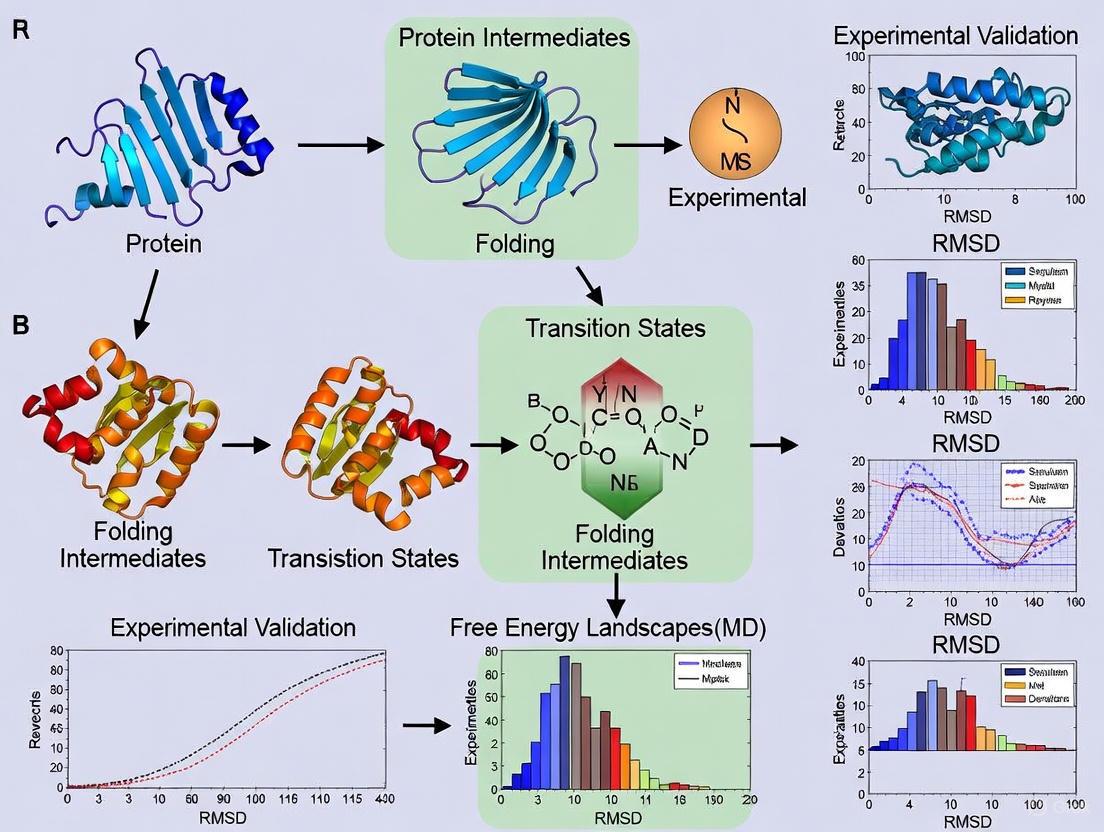

Signaling Pathways and Workflows

Protein Folding Pathway Validation Workflow

Folding Funnel with Key Intermediates

The resolution of Levinthal's paradox through energy landscape theory has fundamentally transformed our understanding of protein folding, replacing the concept of random search with guided navigation through funneled landscapes. This theoretical framework provides a robust foundation for integrating computational predictions with experimental validations, enabling increasingly accurate models of folding pathways.

Current research is extending these principles beyond single-domain folding to complex cellular processes. The emerging paradigm recognizes that protein function often depends on dynamic transitions between multiple conformational states rather than static structures [4]. Future advances will require continued development of multi-scale models that connect folding mechanisms to physiological contexts, including cotranslational folding, chaperone-assisted folding, and the impact of cellular environment on energy landscapes.

As computational methods continue to advance, particularly through machine-learned force fields and enhanced sampling techniques, and experimental approaches provide ever more detailed structural and dynamic information, we move closer to a comprehensive understanding of protein folding that bridges from quantum mechanics to biological function. This integrated approach promises not only to solve the fundamental challenge posed by Levinthal but to enable predictive modeling of protein behavior in health and disease.

The remarkable success of AI-based protein structure prediction systems, acknowledged by the 2024 Nobel Prize in Chemistry, has created a paradigm where three-dimensional protein structures can be determined from sequence alone with unprecedented accuracy [9] [10]. However, this triumph of static structure prediction has inadvertently overshadowed a more fundamental biological process: how proteins dynamically navigate their conformational landscape to reach these native states. For researchers in drug discovery and biomedical science, this folding process is not merely academic; misfolded proteins underlie pathologies from Alzheimer's disease to Type II Diabetes, and a protein's folding pathway can determine its functional state, cellular localization, and susceptibility to aggregation [11] [9]. While static snapshots provide crucial architectural blueprints, they cannot reveal the dynamic journey—the multiple routes, transitional intermediates, and kinetic traps—that proteins experience in living systems. This guide examines the critical experimental and computational methodologies bridging this gap, comparing their capabilities in validating and elucidating these essential biological pathways.

Fundamental Concepts: From Energy Landscapes to Multiple Pathways

The conceptual framework for understanding protein folding has evolved significantly from simplistic linear models to a more nuanced energy landscape theory. This theory visualizes folding as a funnel-like multidimensional surface where a protein navigates from an ensemble of unfolded states toward the native conformation with the lowest free energy [12]. A key implication of this landscape is the potential existence of multiple folding pathways, where different molecules of the same protein may reach the identical native state via distinct structural routes [13] [12].

The question of whether proteins with similar architectures fold via conserved pathways remains actively debated. Experimental studies comparing proteins with similar tertiary structures but divergent sequences reveal that some folds display highly conserved transition state structures, while others do not [14]. This suggests that certain topologies may restrict folding to a limited number of pathways, whereas others permit many potential routes to the native state [14]. This principle extends beyond proteins to RNA molecules, where studies have demonstrated that co-transcriptional folding during synthesis in the cellular environment can steer molecules along pathways distinct from those taken during refolding of full-length sequences in vitro [15].

Computational Approaches for Pathway Prediction

Computational methods, particularly Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations, provide the primary tools for generating atomic-resolution hypotheses about folding pathways. The table below compares the fundamental approaches used to simulate these dynamic processes.

Table 1: Computational Methods for Simulating Folding Pathways

| Method | Fundamental Principle | Key Applications | Notable Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Classical MD [13] | Numerically solves Newton's equations of motion for all atoms under physiological conditions. | Simulating unfolding at high temperature; analyzing denatured state ensembles. | Extremely computationally expensive; limited to microsecond-millisecond timescales. |

| Essential Dynamics Sampling (EDS) [16] | Biases MD simulation to explore configurations along collective motions derived from native state dynamics. | Folding simulations from unfolded states; studying large proteins like cytochrome c. | Relies on predefined collective coordinates; may miss novel pathways. |

| Targeted MD [16] | Applies time-dependent harmonic restraints to steer the system from an initial to a target structure. | Calculating reaction paths between two known conformations. | The chosen path may not be the physiologically relevant one. |

| AI-Based Prediction (AlphaFold) [17] [9] [10] | Uses deep learning on known structures to predict static native conformations from sequence. | Rapid generation of native state models; protein-ligand interaction prediction. | Provides static snapshots; does not model folding kinetics or pathways. |

A significant challenge in comparing MD-generated pathways is developing robust analytical methods. Researchers employ both geometry-based approaches (like root-mean-squared deviation between structures) and property-based analyses (tracking time-dependent changes in parameters like radius of gyration or solvent-accessible surface area) to objectively compare multiple unfolding trajectories and identify convergent and divergent pathways [13].

Experimental Methods for Pathway Validation

Computational predictions require rigorous experimental validation. The following table summarizes key techniques used to probe folding pathways and their specific applications in pathway characterization.

Table 2: Experimental Methods for Validating Folding Pathways

| Method | Measured Parameter | Application to Folding Pathways | Key Innovation for Pathway Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Φ-value (Phi) Analysis [14] | Changes in transition state stability upon mutation. | Inferring transition state structure and key stabilizing residues. | Quantitative comparison of folding pathways for proteins with similar structures. |

| Single-Molecule Spectroscopy [12] | FRET efficiency, force-extension curves of individual molecules. | Direct detection of multiple pathways and transient intermediates. | Observes heterogeneity hidden in bulk measurements; reveals parallel pathways. |

| Bulk Kinetics with Multiple Probes [12] | Fluorescence, circular dichroism, NMR chemical shift. | Detecting sequence of structure formation from different structural perspectives. | Using multiple probes on the same protein can reveal pathway complexity. |

| cDNA Display Proteolysis [18] | Protease resistance of protein variants linked to their cDNA. | Mega-scale measurement of folding stability for hundreds of thousands of variants. | Identifies stability determinants and quantifies thermodynamic couplings. |

A critical advancement is the development of high-throughput experimental methods like cDNA display proteolysis. This method combines cell-free molecular biology with next-generation sequencing to measure thermodynamic folding stability for up to 900,000 protein domains in a single experiment [18]. By comprehensively measuring all single mutants across hundreds of natural and designed domains under identical conditions, this approach provides the quantitative data necessary to test computational predictions of how sequence encodes folding behavior on an unprecedented scale [18].

Detailed Experimental Protocol: cDNA Display Proteolysis

The following workflow outlines the key steps in this high-throughput stability profiling method [18]:

- Library Preparation: A DNA library is created using synthetic oligonucleotide pools, where each oligonucleotide encodes a single test protein variant.

- cDNA Display: The DNA library is transcribed and translated in vitro using a cell-free cDNA display system, resulting in each protein being covalently attached to its own encoding cDNA at the C-terminus.

- Proteolysis Reaction: The protein-cDNA complexes are incubated with a series of increasing concentrations of protease (e.g., trypsin or chymotrypsin).

- Pull-Down and Quantification: Protease-resistant (folded) proteins are isolated via a pull-down step targeting an N-terminal tag. The relative abundance of each variant in the surviving pool is quantified by deep sequencing.

- Stability Inference: A Bayesian kinetic model is applied to the sequencing count data. The model, based on single-turnover protease cleavage kinetics, infers a K50 value (protease concentration for half-maximal cleavage) for each sequence. Thermodynamic folding stability (ΔG) is then calculated by comparing the measured K50 to the sequence's estimated susceptibility in the unfolded state (K50,U) and a universal folded state susceptibility (K50,F).

Diagram 1: cDNA Display Proteolysis Workflow

Integrated Workflow: Validating Predicted Pathways

Bridging computational prediction and experimental validation requires a structured, iterative workflow. The following diagram synthesizes the methodologies from previous sections into a cohesive framework for testing and refining models of protein folding pathways.

Diagram 2: Pathway Validation Workflow

Successful investigation of folding pathways relies on a suite of specialized reagents, databases, and computational tools. The following table details key resources for researchers in this field.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function in Pathway Research |

|---|---|---|

| ACPro Database [11] | Curated Database | Provides verified protein folding kinetics data (lnkf) and experimental conditions for 126 proteins, enabling confident benchmarking of predictive models. |

| AlphaFold Protein Structure Database [17] | Structure Database | Offers open access to over 200 million predicted protein structures, providing initial native state models for simulation and analysis. |

| AMBER ff99bsc0+χOL3 [15] | Force Field | A refined all-atom force field for MD simulations of nucleic acids, critical for studying RNA folding pathways and co-transcriptional folding. |

| GROMACS [16] | MD Software Package | A high-performance molecular dynamics toolkit used to simulate folding/unfolding trajectories with various force fields. |

| cDNA Display Proteolysis Library [18] | Experimental Reagent | A mega-scale library of protein variants enables high-throughput measurement of folding stability for mutational scanning. |

The journey to fully understand protein folding is transitioning from a focus on static endpoints to a dynamic investigation of pathways. While AI-based structure prediction provides an invaluable starting point, the biological imperative lies in deciphering the kinetic and thermodynamic principles that govern the folding process itself [9] [10]. The synergy between sophisticated computational simulations like MD and groundbreaking high-throughput experimental methods is creating an unprecedented opportunity to achieve this goal. For drug discovery professionals and researchers, embracing this shift from static snapshots to dynamic pathways is not merely an academic exercise. It is essential for understanding disease mechanisms, designing stable biologics, and developing therapeutic strategies that target the folding process itself. The future of structural biology lies not just in knowing the destination, but in comprehensively mapping the journey.

The release of AlphaFold represents a watershed moment in structural biology, largely solving the decades-old protein structure prediction problem with unprecedented accuracy. By demonstrating remarkable performance in CASP14 with a global distance test (GDT) score exceeding 90, AlphaFold achieved approximately three times the accuracy of the next best method and a level comparable to experimental methods [19] [20]. This breakthrough has democratized access to protein structural information, with the AlphaFold Protein Structure Database now providing over 200 million predicted structures to the scientific community and supporting research into diseases, antibiotic resistance, and crop resilience [21] [20].

However, beneath this success lies a significant limitation: despite its exceptional ability to predict static structures, AlphaFold provides limited insight into protein dynamics—the conformational changes, folding pathways, and transient states that underlie biological function. This review examines AlphaFold's performance against alternative computational approaches, with a specific focus on its capabilities and limitations in capturing the dynamic nature of proteins, a crucial aspect for understanding cellular mechanisms and advancing rational drug design.

Performance Comparison: AlphaFold Versus the Computational Toolkit

Accuracy in Static Structure Prediction

Independent validations against experimental structures consistently demonstrate AlphaFold's superiority in predicting static protein folds. In comprehensive comparisons with experimental nuclear receptor structures, AlphaFold 2 achieves high accuracy for stable conformations with proper stereochemistry, though systematic limitations emerge in capturing flexible regions and ligand-binding pockets [22].

Table 1: Quantitative Performance Comparison of Protein Structure Prediction Tools

| Method | Primary Strength | Global Structure Accuracy (GDT_TS) | Ligand Binding Pocket Prediction | Dynamic Sampling |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold 2/3 | Static fold accuracy | ~90 [19] | Underestimates volumes by 8.4% on average [22] | Single conformation [23] [24] |

| Molecular Dynamics (mdCATH) | Conformational sampling | N/A (sampling method) | Captues flexibility [25] | Excellent (62 ms accumulated simulation) [25] |

| Boltz 2 | Binding affinity prediction | High (comparable to AF3) [24] | Dual-head affinity prediction [24] | Limited multi-conformation handling [24] |

| Traditional Docking | Pose prediction | N/A | ~60% accuracy (vs AF3's 93%) [26] | Rigid or flexible docking options |

The table reveals a consistent pattern: while AlphaFold excels at global structure prediction, it systematically underestimates ligand-binding pocket volumes by 8.4% on average and misses functionally important conformational diversity, particularly in homodimeric receptors where experimental structures show functionally important asymmetry [22].

Case Studies Highlighting Limitations in Dynamic Prediction

Real-world applications underscore these limitations, particularly for complex multi-domain proteins and flexible systems:

- Marine Sponge Receptor (SAML): A striking case study reveals severe deviations between experimental and AlphaFold-predicted structures for a two-domain protein, with positional divergences beyond 30 Å and an overall RMSD of 7.7 Å. The relative orientation between domains was incorrectly predicted despite moderate confidence metrics (pLDDT) from AlphaFold [27].

- Nuclear Receptor Flexibility: Comprehensive analysis shows that while AlphaFold accurately predicts stable conformations of nuclear receptors, it captures only single conformational states, missing the spectrum of biologically relevant states particularly in flexible ligand-binding domains, which show higher structural variability (CV = 29.3%) compared to more rigid DNA-binding domains (CV = 17.7%) [22].

- Adversarial Testing Reveals Physical Principles Gap: When challenged with binding site mutagenesis that should physically displace ligands, co-folding models like AlphaFold 3 continue to predict biologically implausible binding modes, indicating potential overfitting to training data rather than learning fundamental physical principles [26].

Experimental Protocols for Validation

Experimental Validation Workflows

The accuracy of computational predictions must be validated against experimental data through standardized protocols:

Table 2: Experimental Validation Methods for Computational Predictions

| Experimental Method | Validation Target | Protocol Summary | Key Findings for AlphaFold |

|---|---|---|---|

| X-ray Crystallography | Global fold accuracy | Molecular replacement using predicted structures as search models | AF2 structures work well as search models, closely resembling crystal structures [19] |

| Cryo-EM | Complex architecture | Fitting predicted models into experimental density maps | AF2 structures fit well into cryo-EM maps [19] |

| NMR Spectroscopy | Solution-state conformation | Comparing predicted models with NMR-derived structures | Excellent fit in majority of cases, indicating predictions not overly biased to crystal state [19] |

| Cross-linking Mass Spectrometry | Distance constraints | Validating residue-residue distances in predicted models | Majority of AF2 predictions correct for single chains and complexes [19] |

| Molecular Dynamics | Conformational stability | Running simulations from predicted structures | mdCATH dataset provides 62 ms simulation data for validation [25] |

Diagram 1: Experimental validation workflow for computational predictions

Methodologies for Assessing Dynamic Properties

Specialized experimental and computational protocols are required to evaluate protein dynamics:

Molecular Dynamics Simulation Protocol (based on mdCATH dataset generation):

- System Preparation: Protein domains solvated in TIP3P water with at least 9 Å padding, neutralized and ionized with Na+ and Cl− ions at 0.150 M concentration [25]

- Force Field Parameterization: CHARMM22* forcefield with particle-mesh Ewald summation for long-range electrostatics [25]

- Sampling Strategy: Five replicates at five temperatures (320 K, 348 K, 379 K, 413 K, 450 K) in geometric progression to capture thermal unfolding [25]

- Data Collection: Coordinates and forces recorded every 1 ns, with over 62 ms of accumulated simulation time enabling statistical analysis of unfolding thermodynamics and kinetics [25]

Sequence-Based Dynamics Prediction (based on folding dynamics method):

- Evolutionary Field Extraction: Obtaining precise evolutionary field from observed variations in homologous protein sequences [28]

- Energy Mapping: Mapping energetics to coarse-grained folding model treating protein as string of interacting foldons [28]

- Equilibrium Calculation: Computing equilibrium folding curve and identifying emergence of protein folding sub-domains for any given protein sequence [28]

- Mutation Analysis: Analyzing how mutations perturb both folding stability and cooperativity [28]

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Resources

| Resource | Type | Primary Function | Access Information |

|---|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold Protein Structure Database | Database | Access to 200+ million predicted structures | https://www.alphafold.ebi.ac.uk/ [20] |

| mdCATH Dataset | Molecular Dynamics Dataset | Proteome-wide dynamic trajectories for 5,398 domains | Available at HuggingFace under CC BY 4.0 license [25] |

| CHARMM22* | Force Field | Empirical energy functions for MD simulations | Standard parameterization in MD packages [25] |

| AlphaFold Server | Prediction Tool | Biomolecular interaction predictions powered by AF3 | Free for non-commercial research [20] |

| Boltz 2 | Prediction Tool | Binding affinity prediction with physics-based steering | Open access to model weights and inference pipeline [24] |

Integrating Static and Dynamic Approaches

The limitations of current AI methods in capturing protein dynamics have prompted the development of integrated approaches that combine deep learning with physics-based simulations:

Diagram 2: Integration of static and dynamic prediction methods

Emerging solutions address AlphaFold's dynamical limitations through several mechanisms:

- Neural Network Potentials: Machine learning approaches that enhance computational protein research by enabling more accurate simulations of dynamic behaviors, potentially trained on MD datasets like mdCATH that include instantaneous forces [25].

- Physics-Informed AI: Models like Boltz 2 that incorporate physics-based steering during inference to improve physical plausibility and overcome limitations like steric clashes and incorrect stereochemistry [24].

- Multi-Temperature Sampling: The mdCATH approach of simulating at multiple temperatures (320-450 K) captures a variety of conformations, including higher energy states encountered during molecular dynamics simulations [25].

AlphaFold has unquestionably revolutionized structural biology by providing rapid, accurate protein structure predictions at an unprecedented scale. However, its limitation in capturing protein dynamics represents a significant frontier for future development. The integration of deep learning with physics-based simulations, enhanced by comprehensive dynamical datasets like mdCATH, points toward a future where computational methods can accurately predict both protein structures and their dynamic behaviors.

For researchers in drug discovery and protein engineering, this evolution is critical. Understanding conformational dynamics, allosteric mechanisms, and folding pathways will enable more sophisticated interventions in biological systems. As the field progresses, the combination of AlphaFold's structural accuracy with the dynamic sampling of molecular dynamics and the emerging class of hybrid AI-physics models promises a more complete computational understanding of protein function, ultimately accelerating therapeutic development and fundamental biological discovery.

Why Validate? Addressing the Sampling and Accuracy Problems in MD Simulations

Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulation has emerged as a fundamental tool for studying protein folding and dynamics at atomic resolution, offering insights that often remain elusive to experimental methods alone [29]. However, MD simulations face two fundamental challenges that necessitate rigorous validation: the sampling problem, where simulations often fail to explore all relevant conformational states due to high-energy barriers and limited timescales, and the accuracy problem, where force field inaccuracies and numerical artifacts can produce unrealistic dynamics [30] [31]. Without proper validation, researchers risk drawing conclusions from incomplete or physically implausible simulations, potentially leading to misleading scientific interpretations [31].

The validation gap becomes particularly critical in the context of protein folding pathway prediction, where the transition between unfolded and native states involves numerous metastable intermediates that are difficult to sample comprehensively [32]. As MD simulations increasingly inform drug discovery and protein engineering, establishing robust validation frameworks ensures that computational predictions align with biophysical reality. This review examines how integrating experimental data with enhanced sampling algorithms and emerging artificial intelligence approaches addresses these fundamental challenges, creating more reliable frameworks for understanding protein folding mechanisms.

Understanding the Core Problems in MD Simulations

The Sampling Problem: Limited Timescales and Energy Barriers

The sampling problem in MD simulations stems from the rough energy landscapes characteristic of biomolecular systems, with many local minima separated by high-energy barriers that govern biomolecular motion [30]. This landscape topography makes it easy for simulations to become trapped in non-functional states for durations exceeding practical simulation timescales. As noted in research on enhanced sampling techniques, "insufficient sampling often limits MD application" due to these inherent energy landscape characteristics [30].

The temporal limitations of MD further exacerbate this sampling challenge. Despite advances in computing power, all-atom MD simulations typically run for tens to hundreds of nanoseconds, up to 1-2 microseconds for state-of-the-art setups [29]. This remains insufficient for many biologically relevant processes, including the folding of many proteins, where folding times can range from microseconds to seconds or longer near physiological conditions. As one analysis of protein folding simulations noted, "refolding from extended states using explicit solvent has been out of reach at these timescales" for many systems of biological interest [29].

The consequences of inadequate sampling are profound for folding pathway studies. A single trajectory rarely captures all relevant conformations, particularly for biological systems with vast conformational spaces that must overcome numerous energy barriers to explore significant states [31]. Without sufficient sampling, simulations may follow pathways that are not statistically representative, potentially missing rare but functionally crucial transition states or intermediates.

The Accuracy Problem: Force Fields and Physical Realism

Beyond sampling limitations, accuracy problems present equally significant challenges for reliable MD simulations. Force field selection profoundly impacts simulation outcomes, as these mathematical models are carefully designed and parameterized for specific molecular classes [31]. Using an inappropriate force field—such as applying a protein-specific model to carbohydrates or nucleic acids—leads to inaccurate energetics, incorrect conformations, or unstable dynamics [31].

Physical realism can be compromised through various other mechanisms as well:

- Incorrect protonation states or missing atoms in starting structures [31]

- Inappropriate simulation parameters, including timestep selection, thermostat/barostat settings, and treatment of periodic boundary conditions [31]

- Mixing incompatible force fields without proper parameterization, disrupting the balance between bonded and non-bonded interactions [31]

- Inadequate equilibration, resulting in systems that don't represent the correct thermodynamic ensemble [31]

These accuracy concerns are particularly problematic because, as noted in common MD mistakes, "MD engines will happily simulate a system even when key components are incorrect" [31]. The simulation may run without crashing while producing physically meaningless results, creating a false sense of security for researchers.

Established Solutions: Enhanced Sampling and Experimental Integration

Enhanced Sampling Algorithms

To address the sampling problem, several enhanced sampling algorithms have been developed that accelerate exploration of conformational space. These methods effectively reduce the energy barriers that limit sampling in conventional MD simulations. The table below compares three major enhanced sampling approaches:

Table 1: Enhanced Sampling Techniques for MD Simulations

| Method | Key Principle | Best For | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Replica-Exchange MD (REMD) | Parallel simulations at different temperatures exchange configurations [30] | Studying free energy landscapes and folding mechanisms [30] | Computational cost increases with system size; temperature selection critical [30] |

| Metadynamics | "Fills free energy wells" with computational bias potential to discourage revisiting states [30] | Protein folding, molecular docking, conformational changes [30] | Depends on proper selection of a small set of collective coordinates [30] |

| Simulated Annealing | Gradual temperature decrease to reach global energy minimum [30] | Characterizing very flexible systems; large macromolecular complexes [30] | May require multiple runs with different cooling schedules [30] |

These algorithms have demonstrated particular value in studying protein folding pathways. For example, replica-exchange molecular dynamics has been successfully employed to study free energy landscapes and folding mechanisms of various peptides and proteins [30]. Metadynamics has proven effective for exploring protein folding landscapes and conformational changes that would be inaccessible to conventional MD [30].

Experimental Data Integration

Integrating experimental data with MD simulations provides a powerful approach to addressing both sampling and accuracy problems. Biophysical methods including NMR, EPR, HDX-MS, SAXS, and cryo-EM provide valuable but often indirect signals about protein structure and dynamics [33]. Integrative modeling approaches combine these experimental data with physics-based simulations to reveal both stable structures and transient, functionally important intermediates [33].

The workflow below illustrates how experimental data can be integrated with MD simulations to validate and refine folding pathway predictions:

Figure 1: Integrative Framework for Validating Folding Pathways

This integrative approach is particularly valuable for characterizing partially folded states that are "heterogeneous, consisting of many rapidly exchanging conformations" [29]. Ensemble averaging from such states complicates the interpretation of experimental data, while MD provides a molecular framework for interpretation. For example, experimental observables such as B-factors from X-ray crystallography can be compared to root mean square fluctuations (RMSF) from simulations, while NMR measurements like Nuclear Overhauser Effect (NOE) distances and scalar coupling constants can be compared to their simulated counterparts [31].

AI-Generated Ensemble Approaches: A Paradigm Shift

Next-Generation Generative Models for Protein Dynamics

Recent advances in artificial intelligence have introduced a new paradigm for addressing sampling limitations in MD simulations. Generative AI models trained on MD simulation data can now produce structural ensembles at a fraction of the computational cost, effectively learning the underlying physics from expensive simulations and generating diverse conformations without simulating every intermediate step [34].

Several innovative architectures have emerged in this space:

- BioEmu: A diffusion model-based generative AI system that simulates protein equilibrium ensembles with 1 kcal/mol accuracy using a single GPU, achieving a 4-5 orders of magnitude speedup for equilibrium distributions in folding and native-state transitions compared to traditional MD [35].

- AlphaFlow: An AF2-based generative model trained on the ATLAS dataset of protein simulations that accurately reproduces residue fluctuations but struggles with complex multi-state ensembles [34].

- aSAM/aSAMt: A latent diffusion model that generates heavy atom protein ensembles, with a temperature-conditioned version (aSAMt) capable of producing conformational ensembles under varying environmental conditions [34].

These approaches represent a fundamental shift from simulating dynamics to learning and generating physically realistic ensembles. As the BioEmu developers note, their approach "overcomes the sampling bottleneck of traditional MD simulations," sampling thousands of structures per hour on a single GPU compared to months on supercomputing resources [35].

Performance Comparison: AI vs. Traditional Methods

The table below quantitatively compares the performance of AI-based generative approaches with traditional MD simulations for ensemble generation:

Table 2: Performance Comparison of MD and AI-Based Ensemble Generation Methods

| Method | Computational Cost | Sampling Rate | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional MD | Months on supercomputers [35] | Limited by simulation time | Physical realism, explicit solvent [29] | Inadequate for large conformational changes [30] |

| Enhanced Sampling MD | Days to weeks on HPC clusters [30] | Improved for specific coordinates | Accelerates barrier crossing [30] | Requires prior knowledge; may bias sampling [30] |

| BioEmu | Hours on single GPU [35] | Thousands of structures/hour [35] | High thermodynamic accuracy; identifies cryptic pockets [35] | Primarily single-chain proteins; larger complexes require optimization [35] |

| AlphaFlow | Minutes to hours on GPU [34] | Varies by system size | Good local flexibility reproduction [34] | Struggles with multi-state ensembles; poor side chain torsions [34] |

| aSAM/aSAMt | Minutes to hours on GPU [34] | Varies by system size | Accurate backbone/side chain torsions; temperature conditioning [34] | Requires energy minimization; lower MolProbity scores [34] |

The performance advantages of AI approaches are particularly evident in their ability to capture thermodynamic properties. BioEmu demonstrates exceptional thermodynamic accuracy in quantitative prediction tasks, achieving less than 1 kcal/mol accuracy in relative free energy through its Property Prediction Fine-Tuning (PPFT) algorithm, which fine-tunes the model on hundreds of thousands of experimental stability measurements [35].

Implementation Guide: Validation Protocols and Research Tools

Essential Validation Workflow

Implementing a robust validation protocol is essential for ensuring the reliability of MD-predicted protein folding pathways. The following workflow outlines key validation steps:

Figure 2: MD Simulation Validation Workflow

This validation workflow emphasizes several critical aspects often overlooked in MD studies:

- Multiple replicate runs are essential because "a single trajectory rarely captures all relevant conformations" for biological systems with vast conformational spaces [31].

- Verification of equilibration through stabilization of key thermodynamic properties including temperature, pressure, total energy, and system density [31].

- Comparison with experimental observables such as B-factors, NMR measurements, or SAXS profiles to ensure physical realism [31].

Table 3: Essential Tools for MD Simulation and Validation

| Tool Category | Specific Tools | Key Function | Application in Folding Studies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structure Preparation | PDBFixer, H++ [31] | Fix missing atoms; assign protonation states | Ensures realistic starting structures for folding simulations |

| MD Engines | GROMACS, AMBER, NAMD [30] [31] | Perform molecular dynamics calculations | Provides production MD with various enhanced sampling methods |

| Enhanced Sampling | PLUMED, COCOMO [30] [34] | Implement advanced sampling algorithms | Accelerates exploration of folding energy landscape |

| AI Generators | BioEmu, AlphaFlow, aSAM [35] [34] | Generate structural ensembles from learned distributions | Rapidly explores conformational diversity in folding pathways |

| Validation & Analysis | MDAnalysis, Bio3D, cpptraj [31] | Analyze trajectories and compare to experiments | Quantifies sampling quality and agreement with experimental data |

| Experimental Data Integration | MAXENT, Bayesian Weighing [33] | Incorporate experimental constraints | Refines ensembles using NMR, cryo-EM, SAXS data |

This toolkit provides researchers with essential resources for each stage of folding pathway investigation, from initial structure preparation to final validation against experimental data. Particularly important are tools for experimental data integration, which enable the "integrative approaches that combine experiments with physics-based simulations" needed to reveal both stable structures and transient intermediates [33].

The sampling and accuracy problems in MD simulations present significant but addressable challenges for predicting protein folding pathways. Traditional enhanced sampling algorithms combined with experimental validation provide robust frameworks for improving simulation reliability, while emerging AI-based generative models offer revolutionary advances in computational efficiency. The key insight across all methodologies is that validation against experimental data is not optional—it is essential for transforming computationally convenient narratives into scientifically valid mechanistic models.

As MD simulations continue to inform drug discovery—helping identify cryptic pockets in Fascin for anti-metastatic cancer drugs or revealing binding sites in sialic-acid binding factors for novel antibiotics [35]—the stakes for accurate folding pathway prediction continue to rise. The integration of physical simulations with AI acceleration and experimental constraints represents the most promising path forward, potentially enabling researchers to achieve both the sampling comprehensiveness and physical accuracy needed to fully elucidate protein folding mechanisms.

Integrated Workflows: Combining AI, MD, and Global Optimization for Pathway Prediction

Leveraging AI-Predicted Structures and Distograms as MD Starting Points

The integration of artificial intelligence (AI)-predicted protein structures into molecular dynamics (MD) simulations represents a rapidly evolving paradigm in computational structural biology. AI systems like AlphaFold have demonstrated remarkable accuracy in predicting static protein structures from amino acid sequences alone, even achieving accuracy competitive with experimental methods in many cases [36]. However, proteins are dynamic entities, and understanding their function, folding pathways, and functional mechanisms often requires insight into their conformational dynamics and energy landscapes. Molecular dynamics simulations provide this dynamical perspective by simulating the physical movements of atoms over time, but their success heavily depends on starting from physiologically relevant conformations [37]. This comparison guide objectively examines the performance of using AI-predicted structures—particularly atomic coordinates and distograms (pairwise distance maps)—as initial conditions for MD simulations, evaluating this hybrid approach against traditional MD initialization methods within the critical context of experimental validation.

Performance Comparison: AI-MD Hybrid vs. Traditional Approaches

The table below summarizes key performance metrics when using AI-predicted structures as MD starting points compared to traditional ab initio or homology-modeled starting structures.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of MD Starting Protocols

| Performance Metric | AI-Predicted Starting Structures | Traditional Homology Models | Ab Initio Folding |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time to Reach Converged Ensemble | Significantly reduced for structured regions [37] | Variable; depends on template quality | Prohibitively long for most proteins |

| Sampling of Rare/Transient States | Enhanced through bias-free initialization; improved identification of folding intermediates [37] [38] | Potentially biased by template conformation | Theoretically complete but practically unachievable |

| Accuracy vs. Experimental Data (NMR, SAXS) | Good agreement for ensemble-averaged properties; potential domain orientation errors [37] [27] | Good if correct template is used | Not applicable on relevant timescales |

| Computational Resource Requirements | Lower overall due to faster convergence [37] | Moderate | Extremely high |

| Applicability to IDPs/IDPRs | Emerging methods show promise [37] | Poor due to lack of structured templates | Only practical for very short peptides |

Quantitative Experimental Data

Several studies have provided quantitative data supporting the hybrid AI-MD approach:

Table 2: Experimental Validation Data for AI-MD Hybrid Methods

| Study System | Key Experimental Validation | Result of AI-MD Integration |

|---|---|---|

| ArkA IDP (Yeast) | Circular Dichroism (CD) Spectroscopy [37] | GaMD simulations initiated from AI-generated ensembles better matched experimental CD data, revealing proline isomerization as a conformational switch [37]. |

| SAML (Marine Sponge Receptor) | X-ray Crystallography [27] | Significant deviation (7.7 Å RMSD) in inter-domain orientation between AlphaFold prediction and experimental structure highlighted the need for MD refinement of AI-predicted multi-domain proteins [27]. |

| Ubiquitin | Topological Data Analysis of Folding Landscape [38] | Novel analysis methods on simulation data showed 10x speed improvement in identifying key topological folding features when leveraging efficient representations [38]. |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol 1: Generating AI-Initialized Conformational Ensembles for IDPs

Intrinsically Disordered Proteins (IDPs) lack stable tertiary structures, existing instead as dynamic ensembles. The following protocol leverages AI to generate structurally diverse starting ensembles for MD simulation of IDPs [37].

- Input Preparation: Provide the amino acid sequence of the IDP or IDPR (Intrinsically Disordered Protein Region).

- Deep Learning Sampling: Employ a deep learning model (e.g., trained on large-scale MD data or experimental ensemble data) to generate a diverse set of conformations. These models learn sequence-to-structure relationships without being constrained by physical force fields.

- Experimental Filtering: Filter the generated conformations against available experimental data, such as Small-Angle X-Ray Scattering (SAXS) profiles or NMR chemical shifts, to ensure the ensemble matches known average properties.

- Ensemble Selection: Select a representative subset of conformations spanning the diverse states identified by the AI.

- MD Simulation and Refinement: Use each selected conformation as a starting point for independent, explicit-solvent MD simulations. This step refines the structures and explores the local conformational landscape around each AI-generated state.

- Validation: Compare the resulting simulation trajectories and meta-stable states with experimental observables not used in the filtering step, such as FRET efficiency or hydrodynamic radius.

Protocol 2: Refining AI-Predicted Multi-Domain Proteins with MD

AI models can mispredict the relative orientation of protein domains [27]. This protocol uses MD to refine these structures.

- Initial Structure Prediction: Generate a 3D model of the multi-domain protein using AlphaFold2 or a similar tool.

- Inter-Domain Analysis: Inspect the Predicted Aligned Error (PAE) plot. High PAE between domains suggests low confidence in their relative orientation.

- Targeted MD Setup: If the PAE is high, or if an experimental structure of the full protein is available for validation, place the protein in a solvated simulation box. If the domain orientation is suspected to be incorrect, consider applying weak restraints to the intra-domain atomic coordinates to maintain domain integrity while allowing inter-domain movement.

- Enhanced Sampling: Run an enhanced sampling MD simulation (e.g., Gaussian Accelerated MD (GaMD) or replica-exchange MD). This accelerates the sampling of different domain orientations and identifies the most stable configuration.

- Experimental Cross-Validation: Validate the refined domain arrangement against experimental data. For example, if the crystal structure is available, calculate the RMSD of the MD-refined model. Alternatively, compare with SAXS data or other solution-phase techniques [27].

Diagram 1: AI-MD refinement workflow for multi-domain proteins.

Table 3: Key Resources for AI-MD Integration and Experimental Validation

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function in Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold2/3[citation:2] | AI Structure Prediction | Provides high-accuracy initial atomic coordinates and per-residue/local distance confidence metrics (pLDDT/PAE). |

| RoseTTAFold[ [39]] | AI Structure Prediction | An alternative end-to-end deep learning model for protein structure prediction with capabilities similar to AlphaFold2. |

| GROMACS/AMBER[ [37]] | Molecular Dynamics Engine | Performs the actual MD simulations for refining structures and exploring dynamics using physics-based force fields. |

| Gaussian Accelerated MD (GaMD)[ [37]] | Enhanced Sampling Method | Accelerates the sampling of rare events (e.g., domain reorientation, proline isomerization) in MD simulations. |

| cDNA Display Proteolysis[ [18]] | High-Throughput Experiment | Measures thermodynamic folding stability for hundreds of thousands of protein variants, providing large-scale data for model training and validation. |

| SAXS[ [37]] | Biophysical Technique | Provides low-resolution structural data in solution, used to validate the overall shape and dimensions of AI-generated and MD-refined ensembles. |

| NMR Spectroscopy[ [37]] | Biophysical Technique | Provides atomic-level data on dynamics and chemical environments in solution, a key benchmark for validating MD-predicted conformational states. |

The integration of AI-predicted structures and distograms as starting points for MD simulations presents a powerful hybrid methodology that combines the strengths of deep learning and physics-based simulation. Quantitative data show this approach can significantly accelerate the convergence of MD simulations and enhance the sampling of functionally relevant states, particularly for complex systems like IDPs. However, performance is not universally superior; key limitations remain, especially regarding the prediction of inter-domain orientations in multi-domain proteins and the inherent biases of AI models trained on existing data. The validity of any computational model, including this hybrid approach, must be rigorously assessed against experimental data. The continued development of high-throughput experimental methods, such as cDNA display proteolysis, will provide the essential benchmark data needed to further refine and validate these integrated computational strategies, ultimately enhancing their reliability for drug development and basic biological research.

The accurate prediction of protein folding pathways represents a central challenge in computational biology, with significant implications for understanding cellular function, molecular disease mechanisms, and drug development. This guide objectively compares methodologies for studying these pathways, focusing on their validation against experimental data. While "Action-CSA" is referenced in the title per your requirement, the specific technical details of this particular methodology were not identified in the available literature. This overview instead focuses on well-documented related techniques in the field, framing them within the research context of validating molecular dynamics (MD)-predicted protein folding pathways with experimental data.

The following sections compare the performance, experimental protocols, and applications of these methods, providing researchers with a practical framework for selecting and implementing pathway search methodologies.

Performance Comparison of Pathway Search and Validation Methods

The table below summarizes the primary computational methods used in protein folding studies, highlighting their respective performance characteristics and validation approaches.

Table 1: Comparison of Protein Folding and Stability Analysis Methods

| Method Name | Method Type | Primary Application | Key Performance Metrics | Typical Validation Data |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EFoldMine [40] [41] | Machine Learning (SVM) | Early Folding Residue (EFR) Prediction | Sensitivity: 73.1%, Specificity: 75.2%, AUC: 80.8% [40] | NMR Pulsed-Labelling HDX [40] |

| QresFEP-2 [42] | Physics-Based (MD/FEP) | Protein Stability & Mutational Effects | High accuracy on 600+ mutations; High computational efficiency [42] | Experimental Protein Stability Data (Thermal Denaturation) [42] |

| Molecular Dynamics (MD) [43] | Physics-Based Simulation | VLP Stability & Self-Assembly | Predicts surface hydrophobicity & structural stability [43] | Experimental Hydrophobicity & Stability Assays [43] |

| AlphaFold Systems [44] | Deep Learning | Protein Structure Prediction | High Reliability in Protein Domain Folding (CASP16) [44] | Experimental Structures (e.g., X-ray, Cryo-EM) [44] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

EFoldMine: Protocol for Early Folding Residue Prediction

EFoldMine is a sequence-based predictor that identifies residues involved in the initial stages of folding, providing a target for validating MD-predicted pathways [40].

- Input Feature Generation: For a given protein sequence, calculate three sets of features for each residue:

- Model Application: Process the feature vector for each residue using the pre-trained Support Vector Machine (SVM) with a Radial Basis Function (RBF) kernel. The model outputs a continuous "early folding score" for each residue position [40].

- Validation with Experimental Data:

- Data Source: Perform or obtain NMR pulsed-labelling Hydrogen-Deuterium Exchange (HDX) experiments. This technique identifies backbone amide protons protected from exchange due to stable hydrogen bonding within milliseconds of folding initiation [40].

- Correlation: Compare computationally predicted EFRs with experimentally identified protected residues. A successful prediction shows significant overlap, providing residue-level validation for proposed folding nuclei [40].

QresFEP-2: Protocol for Free Energy Calculation

QresFEP-2 is a hybrid-topology Free Energy Perturbation (FEP) protocol used to quantify the effects of point mutations on protein stability, testing specific hypotheses about the energetic contributions of residues along a folding pathway [42].

- System Setup:

- Construct a hybrid topology file for the wild-type (WT) and mutant protein. This topology uses a single representation for the conserved protein backbone and dual representations for the differing side-chain atoms [42].

- Embed the protein in a spherical water droplet with appropriate boundary conditions [42].

- Alchemical Transformation:

- Define a thermodynamic pathway (λ-schedule) that gradually transforms the WT side chain into the mutant side chain.

- Run molecular dynamics simulations at intermediate λ-states to sample the conformational space [42].

- Free Energy Analysis:

- Use the Bennett Acceptance Ratio (BAR) or similar method to calculate the relative free energy change (ΔΔG) between the WT and mutant from the simulation data [42].

- Validation with Experimental Data:

- Data Source: Obtain experimental stability data, such as changes in melting temperature (ΔTm) or free energy of unfolding (ΔΔGunfolding), from techniques like differential scanning calorimetry or circular dichroism for a set of mutations [42].

- Benchmarking: Calculate the correlation coefficient (R²), mean absolute error (MAE), and root mean square error (RMSE) between the computed ΔΔG values and the experimental measurements [42].

MD Simulation: Protocol for Assembly Pathway Validation

Molecular dynamics can simulate the stability and assembly of complex structures like virus-like particles (VLPs), providing insights into supramolecular folding pathways [43].

- Model Construction:

- Build a partial VLP model comprising multiple protein chains (e.g., 17 chains of a modified Hepatitis B core protein) based on a known structural template [43].

- Simulation Execution:

- Solvate the model in an explicit water box with ions.

- Run extensive MD simulations (nanoseconds to microseconds) under physiological temperature and pressure to observe stability and subunit interactions [43].

- Property Calculation:

- Analyze simulation trajectories to calculate metrics such as root mean square deviation (RMSD) for stability, radius of gyration (Rg) for compactness, and solvent-accessible surface area (SASA) for surface hydrophobicity [43].

- Validation with Experimental Data:

- Data Source: Perform biochemical assays on the actual VLP candidates. This can include hydrophobicity probes (e.g., ANS dye binding) and stability assays under various stress conditions (e.g., temperature, pH) [43].

- Correlation: Compare the computationally derived properties (e.g., SASA) with experimental measurements (e.g., fluorescence from hydrophobicity dyes). A strong correlation validates the MD model's predictive power for guiding design [43].

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the integrated computational and experimental workflow for validating predicted protein folding pathways, synthesizing the protocols described above.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful validation of folding pathways relies on specific experimental reagents and computational tools.

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for Folding Pathway Research

| Item Name | Function / Application | Relevance to Pathway Validation |

|---|---|---|

| Deuterated Solvent (D₂O) [40] | Solvent for NMR-based Hydrogen-Deuterium Exchange (HDX) experiments. | Enables tracking of protein folding kinetics by identifying backbone amides protected from exchange. |

| Stability Dyes (e.g., ANS) [43] | Fluorescent probes that bind hydrophobic surfaces. | Used to experimentally measure surface hydrophobicity of folding intermediates or designed proteins, validating MD predictions. |

| QresFEP-2 Software [42] | Open-source FEP software integrated with the Q molecular dynamics package. | Calculates the change in free energy upon mutation, providing a physics-based measure of residue stability for benchmark. |

| STRIDE or DSSP | Algorithms for assigning secondary structure from 3D atomic coordinates. | Used to analyze MD simulation trajectories, tracking the formation and dissolution of secondary structures during folding. |

| Start2Fold Database [40] | Public database of experimental data on protein early folding. | Provides a critical benchmark dataset for training and validating computational predictors like EFoldMine. |

The classical challenge of simulating protein dynamics is the immense computational cost of achieving sufficient sampling, particularly for complex processes like folding or the exploration of conformational landscapes by intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs). Traditional all-atom Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations, while highly accurate, are often prohibitively expensive, requiring supercomputers and months of computation to capture rare events [35]. Machine Learning (ML), particularly deep generative models, has emerged as a powerful alternative, offering speedups of several orders of magnitude. However, purely data-driven ML models can sometimes learn statistical shortcuts from their training data rather than underlying physical principles, potentially limiting their generalizability to unseen systems [45]. This guide examines the current state of hybrid pipelines that integrate ML and MD to overcome these individual limitations. By combining the physical rigor of MD with the scalability of ML, these hybrid approaches are enabling the determination of accurate, experimentally-validated conformational ensembles, thereby providing powerful tools for drug discovery and basic research [46] [37].

Comparative Analysis of ML/MD Hybrid Methodologies

The table below summarizes the core architectural and performance characteristics of several contemporary hybrid pipelines, highlighting their distinct approaches to integrating machine learning with molecular dynamics.

Table 1: Comparison of Modern ML/MD Hybrid Pipelines for Conformational Ensemble Generation

| Pipeline Name | Core ML Methodology | MD Integration & Role | Reported Speedup vs. Traditional MD | Key Validation Metrics | Primary Application Scope |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CGSchNet [6] | Deep neural network force field | Bottom-up learning from all-atom MD training data | Several orders of magnitude | Fraction of native contacts, Cα RMSD, folding free energies | Transferable coarse-grained simulation of folded and disordered proteins |

| BioEmu [35] | Diffusion model | Trained on large-scale MD datasets and experimental data; emulates equilibrium ensembles | 4-5 orders of magnitude (on a single GPU) | ~1 kcal/mol thermodynamic accuracy, success rates (55-90%) on domain motion benchmarks | Single-chain protein equilibrium ensembles, cryptic pocket prediction |

| MaxEnt Reweighting [46] | Maximum entropy principle | Reweights frames from long-timescale unbiased MD simulations | N/A (Post-processing of MD data) | Kish ratio, agreement with NMR chemical shifts, SAXS data | Determining force-field independent atomic-resolution ensembles of IDPs |

| DEERFold [47] | Fine-tuned AlphaFold2 | Guided by experimental distance distributions (e.g., from DEER spectroscopy) | N/A (Structure prediction) | Accuracy in switching conformations of membrane transporters | Modeling conformational selection using sparse experimental restraints |

| Hybrid MD-kMC [48] | Kinetic Monte Carlo (kMC) | MD used for local dynamics; kMC for rare events (e.g., secondary/tertiary structure formation) | Faster folding kinetics achieved | Folding intermediates, agreement with experimental folding rates | Protein folding in explicit solvent, pathway exploration |

A critical analysis of these pipelines reveals a trade-off between computational efficiency and physical granularity. CGSchNet and BioEmu represent a paradigm shift toward pure ML emulation, achieving massive speedups by learning to directly generate statistical ensembles from underlying MD or experimental data [6] [35]. In contrast, the MaxEnt Reweighting approach [46] and the Hybrid MD-kMC algorithm [48] represent a tighter, more iterative integration. MaxEnt uses MD as the foundational sampling engine and applies ML principles a posteriori to bias the ensemble toward experimental reality, effectively correcting for force field inaccuracies. The MD-kMC hybrid uses ML-like concepts (kinetic move sets) to steer the MD simulation itself, enabling efficient exploration of complex folding pathways that would be inaccessible to either method alone.

Experimental Protocols and Workflows in Practice

Protocol 1: ML-Driven Coarse-Graining for Transferable Force Fields

The development of a transferable coarse-grained (CG) model like CGSchNet exemplifies a bottom-up hybrid workflow. The protocol involves several key stages [6]:

- Training Set Generation: A diverse dataset of all-atom explicit solvent MD simulations is generated for a wide array of small proteins and peptides. This dataset must encompass varied folded structures and sequences.

- Model Training: A deep neural network (CGSchNet) is trained using the variational force-matching approach. The model learns to predict the effective forces between CG degrees of freedom (e.g., one bead per amino acid) from the all-atom data.

- Simulation and Validation: The trained CG force field is deployed to run simulations on new protein sequences not present in the training data. Performance is validated by comparing the resulting free energy landscapes, metastable states, and fluctuations against reference all-atom simulations and, for larger proteins, experimental data such as relative folding free energies of mutants.

This workflow successfully predicted folding intermediates and unfolded states for several fast-folding proteins, demonstrating that the ML model learned physically meaningful interactions rather than simply memorizing structures [6].

Protocol 2: Integrative Refinement of IDP Ensembles with Maximum Entropy Reweighting

For intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs), a major challenge is deriving an atomic-resolution ensemble that is consistent with experimental observations. The following workflow, which uses maximum entropy reweighting, has proven effective [46]:

- Initial Ensemble Generation: Long-timescale (e.g., 30 µs) all-atom MD simulations of the IDP are performed using one or more state-of-the-art force fields (e.g., a99SB-disp, Charmm36m).

- Forward Calculation of Observables: For every frame in the MD ensemble, experimental observables (NMR chemical shifts, J-couplings, SAXS curves) are calculated using established forward models.

- Automated Reweighting: A maximum entropy algorithm is applied to assign new statistical weights to each frame in the simulation. The goal is to find the set of weights that provides the best agreement with the raw experimental data while minimizing the deviation from the original MD ensemble (i.e., maximizing the entropy of the reweighted distribution).

- Convergence and Validation: The similarity of reweighted ensembles, derived from MD simulations started with different force fields or initial conditions, is assessed. Highly similar final ensembles indicate a robust, force-field independent result that can be considered a accurate model of the solution-state ensemble [46].

The diagram below illustrates the workflow for generating accurate conformational ensembles of IDPs by integrating MD simulations with experimental data.

Protocol 3: Augmenting Structure Prediction with Experimental Restraints

While AlphaFold2 excels at predicting static structures, it can be modified to generate conformational ensembles guided by experimental data. DEERFold is a prime example of this approach [47]: