Bridging the Gap: A Comprehensive Guide to Validating Molecular Dynamics Diffusion Coefficients with Experimental Measurements

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals seeking to validate diffusion coefficients derived from Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations against experimental data.

Bridging the Gap: A Comprehensive Guide to Validating Molecular Dynamics Diffusion Coefficients with Experimental Measurements

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals seeking to validate diffusion coefficients derived from Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations against experimental data. It covers the foundational principles of diffusion in biomedical contexts, details step-by-step methodologies for both MD and experimental techniques like UV-vis spectroscopy and ATR-FTIR, and addresses common challenges in achieving accuracy. A strong emphasis is placed on troubleshooting discrepancies and implementing robust validation protocols to ensure that in-silico predictions reliably inform critical decisions in drug delivery system design and biophysical research.

The Principles of Diffusion: From Fick's Laws to Biomedical Imperatives

Diffusion coefficients are fundamental physicochemical parameters that quantify the rate at which molecules spread through a medium due to random molecular motion. In pharmaceutical development, these coefficients play a critical role in determining drug bioavailability and biodistribution—the journey of a drug from administration to its site of action. A drug's efficacy is fundamentally governed by its ability to traverse biological barriers and reach therapeutic concentrations at target sites. The diffusion coefficient (D*) serves as a key predictor of this behavior, influencing release rates from delivery systems, transport across biological membranes, and distribution within tissues and cells. Understanding and accurately quantifying diffusion coefficients is therefore essential for rational drug design and the development of effective therapeutic systems.

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations have emerged as a powerful computational tool for predicting diffusion coefficients by bridging microscopic particle motion with macroscopic transport properties. At the heart of these studies lies the Einstein relation, which connects the mean squared displacement (MSD) of particles over time to the self-diffusion coefficient. However, the accurate estimation of diffusion coefficients from MD simulations presents significant challenges, including statistical uncertainties arising from finite system sizes, early ballistic regimes, and limited simulation times. Recent methodological advances have focused on improving the statistical treatment of MSD data and validating computational predictions with experimental measurements, creating a more robust framework for pharmaceutical applications.

Computational Methods for Estimating Diffusion Coefficients

Molecular Dynamics Fundamentals

Molecular dynamics simulations calculate diffusion coefficients by tracking the motion of atoms and molecules over time. The primary mathematical relationship used is the Einstein relation, which links the mean squared displacement (MSD) of particles to the diffusion coefficient:

⟨Δr(t)²⟩ = 6D*t + c

where ⟨Δr(t)²⟩ represents the ensemble-average mean squared displacement over time interval t, D* is the self-diffusion coefficient, and c is a constant. In practice, D* is estimated by fitting a linear model to the observed MSD values obtained from simulation data. The accuracy of this estimation depends critically on both the quality of the simulation data and the statistical methods used for analysis. Enhanced techniques such as isolating the ballistic stage and applying thermodynamic corrections have been developed to refine these estimates and improve their agreement with experimental values.

Statistical Analysis Protocols and Uncertainty Quantification

The statistical treatment of MSD data significantly impacts the accuracy and reliability of estimated diffusion coefficients. Different regression methods yield substantially different uncertainty estimates, highlighting that uncertainty depends not only on input simulation data but also on the choice of statistical estimator and data processing decisions.

Table 1: Comparison of Regression Methods for MSD Analysis

| Method | Key Assumptions | Statistical Efficiency | Uncertainty Estimation | Applicability to MSD Data |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) | Data points are statistically independent and identically distributed | Low | Significantly underestimates true uncertainty | Poor - MSD data are correlated and heteroscedastic |

| Weighted Least Squares (WLS) | Accounts for unequal variances (heteroscedasticity) but not correlations | Moderate | Better than OLS but still suboptimal | Moderate - addresses heteroscedasticity only |

| Generalized Least Squares (GLS) | Accounts for both heteroscedasticity and correlation structure | High (theoretically maximal) | Accurate when true covariance is known | Excellent - matches true MSD data structure |

| Bayesian Regression | Uses probability model incorporating covariance structure | High (theoretically maximal) | Provides full posterior distribution | Excellent - naturally handles MSD characteristics |

Recent research has demonstrated that ordinary least squares regression, while simple to implement, is statistically inefficient for MSD analysis and significantly underestimates uncertainty because MSD data points are serially correlated and exhibit unequal variances. Advanced methods like generalized least-squares and Bayesian regression account for this correlation structure and heteroscedasticity, providing statistically efficient estimates with accurate uncertainty quantification. The Bayesian approach, implemented in tools such as the kinisi Python package, models the population of simulation MSDs as a multivariate normal distribution using an analytical covariance matrix derived for freely diffusing particles, then uses Markov chain Monte Carlo to sample the posterior distribution of compatible linear models.

Hybrid and Machine Learning Approaches

Beyond traditional MD analysis, researchers are developing innovative hybrid approaches that combine physical models with machine learning. One recent study created a novel method for analyzing drug diffusion in three-dimensional spaces by solving mass transfer equations computationally and using the generated data to train machine learning models. The research employed three tree-based ensemble models—Kernel Ridge Regression, ν-Support Vector Regression, and Multi Linear Regression—with hyperparameter optimization performed using the Bacterial Foraging Optimization algorithm. The results demonstrated that the ν-SVR model achieved exceptional predictive accuracy with an R² score of 0.99777, significantly outperforming other approaches. This hybrid methodology enables precise prediction of concentration distributions throughout complex three-dimensional domains, which is crucial for optimizing drug delivery systems.

Experimental Methods for Diffusion Coefficient Validation

Standard Experimental Techniques

Experimental validation of computationally derived diffusion coefficients is essential for establishing their reliability in pharmaceutical applications. Various experimental methods have been developed to measure diffusion coefficients across different systems, with particular considerations for drug delivery contexts such as hydrogel-based systems.

Table 2: Experimental Methods for Diffusion Coefficient Measurement

| Method | Principle | Applications | Key Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fluorescence-based Microplate Measurement | Measures fluorescence intensity at different penetration distances in hydrogels | Drug delivery systems, tissue engineering platforms | Simplicity, sensitivity to diffusion variations, adaptable to different hydrogel stiffnesses | Limited to fluorescent molecules or those that can be labeled |

| Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) | Tracks molecular mobility using pulsed field gradients | Broad applicability to various molecular systems | Non-destructive, applicable to diverse molecular types | Equipment cost, technical complexity |

| Diffusion Cells (Franz cells) | Measures transport across membranes or barriers | Transdermal, mucosal, and membrane transport | Physiological relevance for barrier penetration | May not capture full complexity of in vivo environment |

| Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) | Analyzes Brownian motion via scattering fluctuations | Nanoparticles, macromolecules in solution | Rapid measurement, minimal sample preparation | Limited size range, concentration effects |

Experimental Case Study: Hydrogel Diffusion Measurements

A recent study developed a straightforward fluorescence-based method for determining diffusion coefficients in soft hydrogels relevant to drug delivery and biomedical applications. This approach uses fluorescence intensity measurements from a microplate reader to determine solute concentrations at different penetration distances within agarose hydrogels. Researchers analyzed the diffusion behavior of fluorescent particles of varying molecular weights, including fluorescein, mNeonGreen, and fluorophore-labeled bovine serum albumin, in low-percentage agarose hydrogels. The experimental concentration profiles were fitted to a one-dimensional diffusion model to extract diffusion coefficients. The method demonstrated sensitivity to variations in diffusion conditions, enabling the study of solute-hydrogel interactions critical for designing controlled release systems. This experimental approach provides valuable validation data for computational predictions, particularly for systems where solute-carrier interactions significantly influence transport properties.

Integration of Computational and Experimental Approaches

Validation Frameworks

The integration of molecular dynamics simulations with experimental measurements creates a powerful framework for validating diffusion coefficients. A compelling example comes from a study of the (H₂ + CH₄ + H₂O) system, where researchers combined experimental methods with molecular dynamics analysis to investigate gas solubility and diffusivity across a range of temperatures and pressures. The findings demonstrated that pressure has negligible effect on gas diffusivity in water, while temperature dependence follows Arrhenius and Stokes-Einstein relationships. The study revealed that hydrogen diffusion coefficients were 2-3 times higher than those of methane, attributed to methane's stronger interactions with water molecules. This complementary approach, where experimental and molecular dynamics methods mutually validate each other, provides both macroscopic parameters and molecular-level insights into diffusion mechanisms.

Methodological Considerations for Accurate Determination

Several critical factors must be addressed to ensure accurate determination of diffusion coefficients:

- Time scale selection: MD simulations must be sufficiently long to capture diffusive rather than ballistic motion, typically requiring observation beyond the initial non-linear MSD regime.

- Finite-size effects: Simulation cell size impacts calculated diffusion coefficients, necessitating appropriate corrections or sufficiently large systems.

- Statistical efficiency: Advanced regression methods like Bayesian approaches provide more reliable uncertainty estimates than conventional least-squares fitting.

- Force field selection: The choice of interaction potentials significantly influences molecular dynamics results, particularly for complex pharmaceutical systems.

- Experimental calibration: Computational methods should be calibrated against experimental measurements for similar systems to establish reliability.

The synergy between computational and experimental approaches allows researchers to overcome the limitations of either method alone. MD simulations provide atomic-level insights and can explore conditions difficult to achieve experimentally, while experimental measurements ground computational predictions in physical reality and validate methodological approaches.

Implications for Drug Bioavailability and Biodistribution

Role in Bioavailability Optimization

Diffusion coefficients directly impact key pharmaceutical parameters including drug release rates, membrane permeation, and ultimately bioavailability. For small-molecule drugs, adequate aqueous solubility is fundamental to bioavailability, as drugs must dissolve in gastrointestinal fluids before permeating biological membranes. The Biopharmaceutics Classification System categorizes drugs based on solubility and permeability characteristics, both of which are governed by diffusion processes. Computational models that accurately predict diffusion coefficients enable researchers to optimize molecular structures and formulation approaches during early development stages, reducing late-stage attrition due to poor bioavailability.

Advanced Delivery System Design

In controlled release systems, diffusion coefficients determine drug release kinetics from carrier materials. Accurate knowledge of these parameters allows precise engineering of release profiles to maintain therapeutic concentrations. For tissue engineering applications, nutrient diffusion coefficients guide scaffold design to ensure adequate nutrient transport throughout constructed tissues. The integration of MD simulations with machine learning approaches, as demonstrated in hybrid 3D diffusion models, enables the prediction of concentration distributions throughout complex delivery systems, supporting the rational design of next-generation drug formulations.

Essential Research Tools and Reagents

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Diffusion Studies

| Tool/Reagent | Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Dynamics Software | Simulates atomic-level molecular motion | Calculating MSD from particle trajectories |

| Kinisi Python Package | Implements Bayesian regression for MSD analysis | Uncertainty quantification in diffusion coefficients |

| Microplate Reader with Fluorescence Detection | Measures solute concentration in hydrogels | Experimental diffusion coefficient determination |

| Agarose Hydrogels | Model matrix for diffusion measurements | Studying solute transport in biomaterials |

| Isolation Forest Algorithm | Identifies outliers in datasets | Data preprocessing for machine learning approaches |

| Bacterial Foraging Optimization | Optimizes hyperparameters in machine learning models | Fine-tuning regression models for diffusion prediction |

| ν-Support Vector Regression | Machine learning model for relationship modeling | Predicting concentration distributions in 3D space |

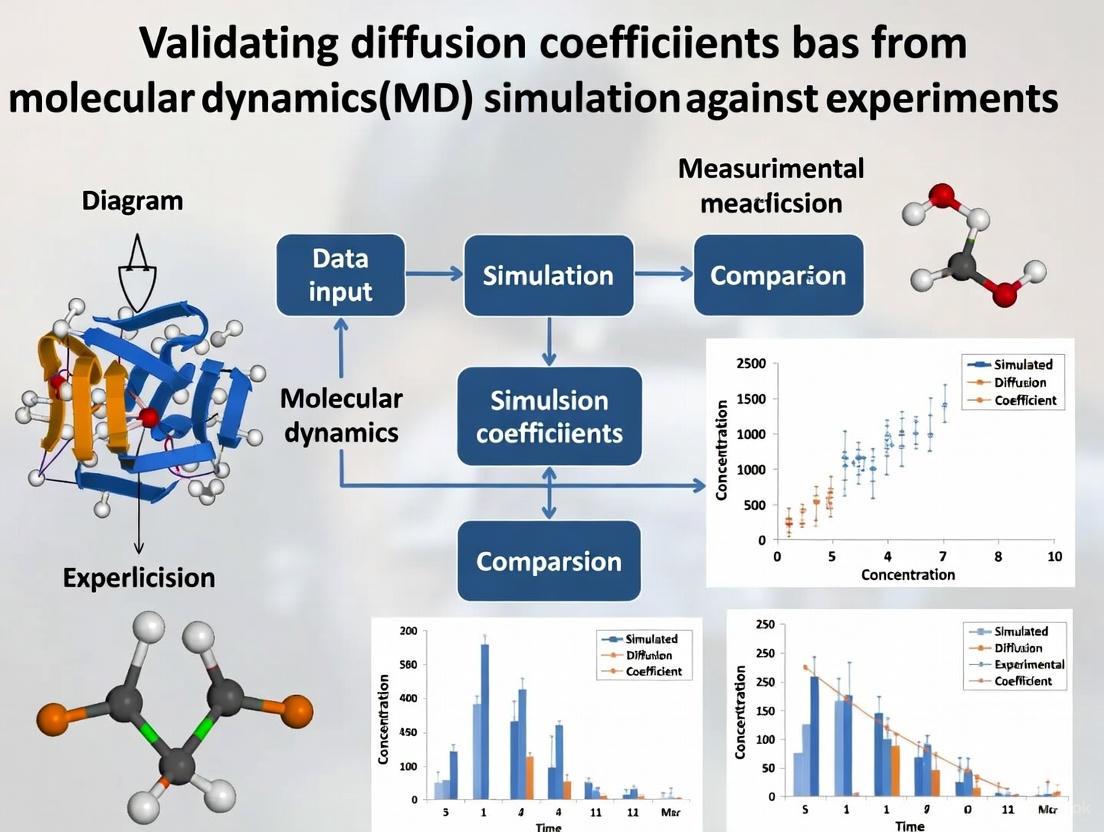

Visualizing Methodologies and Relationships

Computational-Experimental Validation Workflow

MSD Analysis and Uncertainty Quantification

Accurate determination of diffusion coefficients through validated computational and experimental approaches is fundamental to advancing pharmaceutical development. Molecular dynamics simulations, particularly when employing statistically efficient analysis methods like Bayesian regression, provide powerful tools for predicting these parameters with quantified uncertainties. Experimental techniques, especially those tailored to specific drug delivery contexts such as hydrogel systems, offer essential validation and context for computational predictions. The integration of these approaches through robust validation frameworks enables researchers to establish reliable structure-diffusion relationships critical for optimizing drug bioavailability and biodistribution. As methodology continues to advance, particularly through hybrid models combining physical principles with machine learning, the pharmaceutical field moves closer to predictive design of drug delivery systems with precisely controlled release and distribution properties. This progression supports the development of more effective therapeutics with optimized performance characteristics tailored to specific clinical needs.

First posited by Adolf Fick in 1855, Fick's Laws of Diffusion provide the fundamental mathematical framework for describing mass transport phenomena across scientific disciplines [1]. These principles have evolved from describing simple salt diffusion in water to forming the core of our understanding of diffusion in solids, liquids, and gases [1]. In contemporary research, Fick's Laws serve as the critical link between experimental measurements and computational predictions, particularly in the validation of diffusion coefficients derived from molecular dynamics (MD) simulations. This guide objectively compares the performance of modern methodologies for determining diffusion coefficients, with a specific focus on how molecular dynamics simulations are validated against experimental measurements—a crucial process for ensuring predictive accuracy in fields ranging from drug development to materials science.

The enduring relevance of Fick's work lies in its analogous relationship with other fundamental transport laws discovered in the same era: Darcy's law (hydraulic flow), Ohm's law (charge transport), and Fourier's law (heat transport) [1]. This cross-disciplinary foundation makes Fick's Laws particularly valuable for researchers seeking to bridge microscopic simulations with macroscopic experimental observations.

Mathematical Foundations of Fick's Laws

Fick's First Law: The Steady-State Condition

Fick's First Law establishes the fundamental relationship between diffusive flux and concentration gradient, serving as the cornerstone for steady-state diffusion analysis. The law postulates that the flux goes from regions of high concentration to regions of low concentration, with a magnitude proportional to the concentration gradient [1]. In its most common one-dimensional form on a molar basis, the law is expressed as:

[ J = -D \frac{d\varphi}{dx} ]

where J represents the diffusion flux (amount of substance per unit area per unit time), D is the diffusion coefficient or diffusivity (area per unit time), φ is the concentration (amount of substance per unit volume), and x is position [1]. The negative sign indicates that diffusion occurs down the concentration gradient. For systems with more than one spatial dimension, this relationship is generalized using the del operator (∇): J = -D∇φ [1].

The diffusion coefficient D embodies the physicochemical nature of the system, exhibiting proportionality to the squared velocity of diffusing particles while depending on temperature, viscosity, and particle size as described by the Stokes-Einstein relation [1]. In dilute aqueous solutions at room temperature, typical diffusion coefficients range from (0.6–2)×10⁻⁹ m²/s for most ions, while biological molecules generally demonstrate coefficients between 10⁻¹⁰ and 10⁻¹¹ m²/s [1].

Fick's Second Law: The Transient Diffusion Equation

Fick's Second Law predicts how diffusion causes concentration to change with time, making it essential for modeling non-steady-state processes. This partial differential equation describes the temporal evolution of concentration fields and in one dimension reads:

[ \frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial t} = D \frac{\partial^2 \varphi}{\partial x^2} ]

where φ is the concentration, t is time, D is the diffusion coefficient, and x is position [1]. For multidimensional systems, this generalizes to ∂φ/∂t = D∇²φ, where ∇² is the Laplacian operator [1]. This law derives directly from Fick's First Law combined with mass conservation in the absence of chemical reactions, and it shares identical mathematical form with the heat equation [1].

The fundamental solution to Fick's Second Law for a point source in one dimension is given by:

[ \varphi(x,t) = \frac{1}{\sqrt{4\pi Dt}} \exp\left(-\frac{x^2}{4Dt}\right) ]

This Gaussian distribution reflects the random walk nature of diffusive processes and provides the theoretical foundation for many experimental and computational analysis techniques [1].

Methodological Comparison: Experimental, Simulation, and Hybrid Approaches

Determining reliable diffusion coefficients remains challenging due to the inherent instability, nonlinearity, and computational demands of inverse problems in parameter identification [2]. The scientific community has developed multiple approaches to address this challenge, each with distinct advantages and limitations.

Traditional Experimental Methods

Experimental measurements typically employ indirect methods where an initial state is established, followed by measurements of physical quantities related to the diffusion coefficient, such as diffusion flux and concentration distributions [2]. For example, diffusion welding experiments with hot isostatic pressing (HIP) processes have been used to study atomic diffusion at Fe-Ti interfaces, with samples characterized using scanning electron microscopy and energy-dispersive spectroscopy [3]. These methods provide tangible physical evidence but often lack the spatial and temporal resolution needed to probe fundamental atomic-scale mechanisms.

Molecular Dynamics Simulation Approaches

Molecular Dynamics simulations have emerged as powerful computational tools for investigating diffusion phenomena at the atomic scale. MD simulations integrate classical equations of motion to generate time-resolved atomistic trajectories, enabling direct calculation of dynamic properties based on interatomic interactions [4]. The accuracy of these simulations heavily depends on the employed interaction potential, with the Lennard-Jones potential being a common choice for its simplicity and computational efficiency [4].

Two primary MD approaches exist for calculating diffusion coefficients: equilibrium MD (EMD) and reverse non-equilibrium MD (R-NEMD) [5]. EMD methods analyze spontaneous concentration fluctuations in systems at equilibrium, while R-NEMD imposes a mass flow and measures the resulting composition gradient [5]. Recent innovations include the modified Fourier Correlation Method (mFCM), which extends the original FCM approach to handle complex molecular systems beyond simple Lennard-Jones fluids [5].

Emerging Hybrid and Machine Learning Methodologies

Recent methodological advances combine physical principles with data-driven approaches. Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs) integrate Fick's laws directly into neural network architectures, embedding physical constraints that enhance reliability while reducing computational demands [2]. These models can estimate diffusion coefficients under varying data availability scenarios—when both diffusion flux and concentration gradient are known, when only flux is known, or when only concentration gradient is available [2].

Symbolic regression (SR), a supervised machine learning technique, has also been employed to derive accurate, interpretable expressions for self-diffusion coefficients based on macroscopic properties like density, temperature, and confinement size [4]. This approach generates simple symbolic equations that capture fundamental physical relationships while bypassing computationally intensive atomistic calculations [4].

Table 1: Comparison of Diffusion Coefficient Determination Methodologies

| Methodology | Underlying Principle | Key Applications | Primary Advantages | Inherent Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Experiments [3] [2] | Physical measurement of concentration gradients or diffusion fluxes | Material interfaces, biological systems | Direct physical evidence, established protocols | Limited resolution, difficult to isolate parameters |

| Equilibrium MD [5] [4] | Analysis of spontaneous fluctuations at equilibrium | Bulk fluids, confined systems | Fundamental approach, no external perturbation | Computational cost, statistical uncertainty |

| Reverse NEMD [5] | Imposition of mass flow with measurement of resulting gradient | Binary mixtures, interface systems | Controlled driving force, better signal-to-noise | Non-physical perturbation, potential artifacts |

| Physics-Informed Neural Networks [2] | Integration of Fick's laws into neural network loss functions | Inverse problems with partial data | Physical consistency, computational efficiency | Training data requirements, potential overfitting |

| Symbolic Regression [4] | Genetic programming to derive analytical expressions | Bulk and confined fluids, material design | Interpretability, physical consistency | Domain limitation, expression complexity tradeoffs |

Validation Protocols: Integrating MD Simulations with Experimental Measurements

The critical challenge in diffusion coefficient determination lies in validating computational predictions with experimental measurements. Several sophisticated protocols have emerged to address this challenge, each providing a distinct pathway for confirmation.

Direct Trajectory-to-Continuum Fitting

A recently developed procedure estimates diffusion coefficients by fitting MD trajectories to finite-difference simulations of continuum diffusion equations [6]. This approach involves conducting MD simulations of gas mixtures interacting through potentials like Lennard-Jones, while simultaneously performing finite-difference calculations to solve continuum diffusion equations with a given diffusion coefficient [6]. The optimal diffusion coefficient is estimated by minimizing the difference between binned MD data and finite-difference solutions using nonlinear least squares optimization [6]. This direct comparison provides a rigorous bridge between atomistic and continuum descriptions.

The Modified Fourier Correlation Method (mFCM)

The mFCM approach calculates Fick diffusion coefficients directly from equilibrium MD simulations by analyzing concentration fluctuations in the Fourier domain [5]. This method builds upon the original Fourier Correlation Method but introduces modifications to generalize it for complex molecular systems beyond simple Lennard-Jones fluids [5]. The approach establishes that for a binary mixture in the linear regime, the time derivative of concentration fluctuations is proportional to the negative product of the diffusion coefficient and wavevector squared [5]. This method has demonstrated particular utility for studying mixtures at high pressures, such as CO₂ and n-alkane systems relevant to oil and gas reservoirs [5].

Multi-technique Cross-Validation

Comprehensive validation often requires cross-referencing multiple determination methods. For instance, researchers may calculate Fick diffusivities through both direct approaches (like mFCM) and indirect routes involving Maxwell-Stefan coefficients converted to Fick diffusivities using thermodynamic factors [5]. This multi-technique approach provides robust validation through methodological triangulation, helping researchers identify potential systematic errors and strengthen confidence in the resulting diffusion coefficients.

Table 2: Experimental Validation Approaches for MD-Calculated Diffusion Coefficients

| Validation Method | Core Validation Mechanism | Required Input Data | Validation Metrics | Representative Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Finite-Difference Fitting [6] | Minimization of difference between binned MD data and continuum solutions | MD trajectories, initial concentration profiles | Residual sum of squares, convergence iterations | Argon-helium gas mixtures [6] |

| Thermodynamic Factor Conversion [5] | Comparison of direct Fick coefficients with MS-derived values | MS coefficients, activity coefficients, composition data | Deviation in Fick coefficients, consistency across compositions | CO₂/n-alkane mixtures at high pressure [5] |

| Experimental Diffusivity Comparison [3] | Direct comparison of simulated and measured diffusion coefficients | Experimental diffusion data, interface characterization | Relative error, temperature trend agreement | Fe-Ti interface diffusion [3] |

| Symbolic Regression Validation [4] | Agreement between SR predictions and MD/experimental values | Macroscopic system parameters, reference diffusion values | Coefficient of determination (R²), absolute average deviation | Bulk and confined molecular fluids [4] |

Research Toolkit: Essential Materials and Reagent Solutions

The reliable determination of diffusion coefficients requires specialized computational tools and experimental materials. The following table summarizes key resources employed in contemporary diffusion research.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Diffusion Studies

| Tool/Reagent | Type | Primary Function | Example Applications | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LAMMPS | Software | Large-scale Atomic/Molecular Massively Parallel Simulator for MD simulations | Fe-Ti interface diffusion, gas mixture diffusion | [6] [3] |

| MEAM Potential | Computational | Modified Embedded-Atom Method potential for interatomic interactions | Metal interface diffusion studies | [3] |

| Lennard-Jones Potential | Computational | Pair potential for modeling van der Waals interactions | Simple fluids, gas mixtures | [6] [4] |

| SPC/E Water Model | Computational | Extended Simple Point Charge model for water molecules | Aqueous systems, biological diffusion | [7] |

| Hot Isostatic Pressing | Experimental Apparatus | Diffusion welding with controlled temperature and pressure | Metal composite interface formation | [3] |

| Physics-Informed Neural Networks | Computational Framework | Neural networks with embedded physical constraints | Inverse diffusion problems | [2] |

| Symbolic Regression | Computational Algorithm | Genetic programming to derive analytical expressions | Self-diffusion coefficient prediction | [4] |

Workflow Visualization: Methodological Integration Pathways

The validation of molecular dynamics predictions against experimental measurements follows systematic workflows that integrate multiple computational and experimental techniques. The following diagrams illustrate key methodological relationships and processes.

MD-Experimental Validation Workflow

MD-Experimental Validation Workflow

Methodology Relationship Network

Methodology Relationship Network

The determination of reliable diffusion coefficients requires convergent validation across multiple methodologies. While Molecular Dynamics simulations provide atomistic insights into diffusion mechanisms, their predictive accuracy depends on rigorous validation against experimental measurements. Contemporary research demonstrates that no single methodology suffices for all scenarios; instead, the most robust approaches combine MD simulations with experimental measurements, often enhanced by emerging machine learning techniques that embed physical constraints into data-driven models.

This methodological integration is particularly crucial for complex systems such as confined fluids, high-pressure mixtures, and biological environments where simplified models often fail. The continuing development of hybrid approaches—such as Physics-Informed Neural Networks and Symbolic Regression—promises to enhance both the computational efficiency and physical consistency of diffusion coefficient determination, ultimately strengthening the foundation for predictive modeling in drug development, materials design, and industrial process optimization.

Understanding and predicting molecular diffusion is fundamental to advancements in drug delivery, materials science, and energy storage. This guide objectively compares diffusion behavior across three key environments: aqueous solutions, polymers, and complex biological matrices like mucus. A critical theme is the rigorous validation of diffusion coefficients obtained from Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations with experimental measurements. Such validation is essential for developing reliable predictive models that can accelerate research and development across scientific disciplines.

The following sections provide a direct comparison of diffusion characteristics, summarize key experimental data, detail common methodologies, and outline the essential tools for researchers in this field.

Comparative Analysis of Diffusion Environments

The rate and mechanism of molecular diffusion vary significantly depending on the physical and chemical properties of the environment. The table below provides a comparative overview of these key environments.

Table 1: Comparison of Key Diffusion Environments

| Environment | Typical Structure | Dominant Diffusion Mechanism | Key Influencing Factors | Sample Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aqueous Solutions [8] | Homogeneous liquid | Free (Fickian) diffusion | Temperature, pressure, solute size and concentration [8] | Underground hydrogen storage, chemical reactors |

| Polymers | Cross-linked or entangled chains | Reptation (for large chains), hindered diffusion | Mesh size, polymer concentration, chain flexibility, solute-polymer interactions | Drug delivery systems, hydrogels, membranes |

| Biological Matrices (Mucus) [9] [10] [11] | Heterogeneous hydrogel with a mucin fiber network [9] | Hindered diffusion, often anomalous (sub-diffusion) [11] | Pore size (~100 nm), solute size/charge/topology, ionic interactions [9] [10] | Mucosal drug delivery, vaccine development, infection studies |

Experimental and computational studies yield quantitative data on diffusion coefficients, which are crucial for validating molecular models.

Table 2: Experimental and MD-Derived Diffusion Coefficients

| Solute | Environment | Conditions (T, P) | Experimental D (m²/s) | MD-Derived D (m²/s) | Notes | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H₂ | Water | 294-374 K, 5.3-300 bar [8] | — | — | Diffusion coefficient is 2-3x higher than CH₄ [8] | [8] |

| CH₄ | Water | 294-374 K, 5.3-300 bar [8] | — | — | Interacts more strongly with H₂O than H₂ [8] | [8] |

| Linear DNA (2.7-8.3 kb) | Bovine Cervical Mucus | Room Temperature (20°C) [10] | ~1-3 x 10⁻¹² [10] | — | Diffusion not significantly retarded vs. PBS (Dmucus/DPBS ~1) [10] | [10] |

| Supercoiled DNA (>5 kb) | Bovine Cervical Mucus | Room Temperature (20°C) [10] | < ~1 x 10⁻¹² [10] | — | Significantly retarded in mucus (Dmucus/DPBS < 1) [10] | [10] |

| Various Particles | Mucus (from multiple sources) | Varies by study [11] | 10⁻⁵ to 10² μm²/s [11] | — | Effective diffusion (D_eff) spans 7 orders of magnitude [11] | [11] |

Experimental Protocols for Measuring Diffusion

Fluorescence Recovery After Photobleaching (FRAP)

FRAP is a widely used technique to measure the diffusion of fluorescently labeled molecules and particles in fluids and gels, including mucus [10] [12].

- Sample Preparation: The sample (e.g., bovine cervical mucus) is placed on a microscope slide. The solute of interest (e.g., DNA) is fluorescently labeled and mixed into the mucus at a defined concentration [10].

- Bleaching and Recovery: A high-intensity laser beam bleaches a small, defined region of the sample, eliminating fluorescence. The laser power is then drastically reduced, and the recovery of fluorescence into the bleached area is monitored over time [10].

- Data Analysis: The recovery curve (fluorescence intensity vs. time) is analyzed. The diffusion coefficient (D) is calculated using the equation: ( D = \gamma R^2 / 4t{½} ), where ( \gamma ) is a constant related to the extent of bleaching, ( R ) is the radius of the bleached area, and ( t{½} ) is the half-time for recovery [10].

Multiple Particle Tracking (MPT)

MPT is a powerful method for characterizing the microscopic movement of particles in complex, heterogeneous environments like mucus [11] [12].

- Particle Tracking: Fluorescently labeled particles (e.g., drug carriers, viruses) are suspended in the mucus sample. Using fluorescence video microscopy, the trajectories of hundreds to thousands of individual particles are recorded over time [12].

- Trajectory Analysis: An image analysis algorithm processes the video to determine each particle's path. The mean-squared displacement (MSD) is calculated for each particle and then averaged over the ensemble [12].

- Diffusivity Calculation: The effective diffusivity (( D{eff} )) is derived from the MSD using the formula ( D{eff} = \langle MSD \rangle / (2k \Delta t{eff} ) ), where ( k ) is the dimensionality and ( \Delta t{eff} ) is the sampling time window (often 1 second) [11]. MPT can also reveal whether diffusion is normal or anomalous (sub-diffusive) by analyzing the slope of the MSD versus time plot on a log-log scale [11].

Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations

MD simulations provide atomic-level insights into diffusion mechanisms and are used to predict diffusion coefficients.

- System Setup: A simulation box is created containing water molecules and solute molecules (e.g., H₂, CH₄). The choice of force field, which describes the interatomic potentials, is critical for accuracy [8].

- Simulation Run: The classical equations of motion for all atoms are solved numerically over time, typically at a specific temperature and pressure, mimicking experimental conditions [8].

- Coefficient Calculation: The diffusion coefficient is calculated from the slope of the mean-squared displacement of the solute molecules over time, using the Einstein relation: ( D = \frac{1}{6} \lim_{t \to \infty} \frac{d}{dt} \langle |r(t) - r(0)|^2 \rangle ), where ( r(t) ) is the position of a molecule at time ( t ) [8].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

Successful experimentation in this field relies on a suite of specialized reagents and materials.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Reagent/Material | Function/Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Plasmid DNAs [10] | Model macromolecules of varying sizes and topologies (linear, supercoiled) to study the effect of molecular properties on diffusion. | Used in FRAP studies to probe the pore size and restrictive nature of mucus gels [10]. |

| Fluorescent Labeling Kits [10] | Chemical kits (e.g., Label IT Fluorescein) for covalently attaching fluorophores to molecules like DNA for visualization. | Essential for preparing samples for FRAP and MPT experiments [10]. |

| Native Mucus [12] | Mucus collected from tissues (human/animal) such as gastrointestinal, respiratory, or cervical sources. Presents the most physiologically relevant barrier. | The gold-standard model for ex vivo diffusion studies (MPT, FRAP) to predict in vivo performance [12]. |

| Purified Mucin Preparations [12] | Commercially available or lab-purified mucin glycoproteins used to create synthetic or semi-synthetic mucus gels. | Offers a more reproducible and simplified model for high-throughput screening of drug candidates [12]. |

| Transfection Reagents [10] | Liposomes (e.g., Tfx-20) or dendrimers (e.g., Superfect) that complex with DNA, altering its size, charge, and topology. | Used to study how drug carrier systems navigate the mucus barrier [10]. |

| Carboxylated Polystyrene Particles [11] [12] | Synthetic particles with defined surface chemistry (COOH) and size, used as model drug carriers. | Utilized in MPT studies to systematically investigate the role of particle size and surface charge in mucus diffusion [11] [12]. |

| Mucolytic Agents [12] | Compounds like N-acetylcysteine (NAC) that break down the mucin network by cleaving disulfide bonds. | Used as a control to alter mucus viscosity and confirm that hindered diffusion is due to the mucin mesh [12]. |

Why Validate? The Critical Need to Bridge Computational Predictions and Experimental Reality

Computational models, particularly Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations, have become indispensable tools across scientific disciplines, from metallurgy to drug development. They provide atomistic insights into processes that are often difficult or impossible to observe directly, such as diffusion in molten oxides or atomic behavior at material interfaces [13]. However, the predictive power of these simulations is entirely dependent on the accuracy of their underlying parameters and force fields. Without rigorous experimental validation, computational predictions risk remaining precisely that—predictions, whose relationship to physical reality is uncertain [3]. This guide examines the critical importance of validating diffusion coefficients from MD simulations through experimental measurements, comparing validation approaches across fields, and providing a structured framework for researchers to bridge the computational-experimental divide.

The High Stakes of Diffusion Coefficient Accuracy

Industrial and Scientific Implications

Accurate diffusion coefficients are critical for modeling and optimizing industrial processes. In metallurgy, they govern phase transformations, corrosion resistance, and the properties of composite materials [3]. In pharmaceutical development, they influence drug release rates, membrane permeability, and bioavailability. Discrepancies in predicted diffusion coefficients can lead to substantial errors in process models. For instance, in CaO-Al₂O₃-SiO₂ melts relevant to steelmaking, different force fields can predict diffusion coefficients varying by up to two orders of magnitude at similar temperatures—differences that significantly impact industrial process optimization [13].

Methodological Limitations in Computational Predictions

Classical MD simulations face several inherent limitations that necessitate experimental validation. The accuracy of CMD relies entirely on the quality of the empirical force field used [13]. Force fields are typically parameterized for specific conditions or properties and may not transfer reliably to different compositional ranges or temperature regimes. Ab initio MD provides a more rigorous quantum mechanical description but remains computationally prohibitive for systems larger than a few hundred atoms or timescales beyond tens of picoseconds [13]. This limitation is particularly significant for diffusion studies, where adequate statistical sampling requires following atomic trajectories for nanoseconds or longer.

Comparative Analysis: Validation Across Disciplines

Materials Science and Metallurgy

Table 1: Validation Approaches in Materials Science

| Material System | Computational Method | Experimental Validation | Key Findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CaO-Al₂O₃-SiO₂ melts | Classical MD with BMH/Buckingham potentials | High-temperature density measurements, structural data | Force fields optimized for crystals performed poorly for melt transport properties | [13] |

| Fe-Ti interface | MD with MEAM potential | Diffusion welding with HIP process, SEM/EDS analysis | Polycrystals showed thicker diffusion layers than single crystals due to grain boundaries | [3] |

| Liquid Sn (liq-Sn) | MD with modified EAM | Quasi-elastic neutron scattering, X-ray scattering | Unique "shoulder" structure affects microscopic diffusion behavior | [14] |

Research on Fe-Ti interfaces demonstrates how validation reveals limitations in simulation models. MD simulations initially assumed single-crystal systems, but experimental results showed that polycrystalline samples exhibited different diffusion behavior due to the presence of grain boundaries, which increase atomic disorder and facilitate diffusion [3]. This discrepancy highlighted the importance of modeling realistic microstructures rather than idealized single crystals.

Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Applications

Table 2: Validation in Biomedical Research

| Application Area | Computational Method | Experimental Validation | Performance Metrics | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OCT fluid biomarker segmentation | Diffusion models, U-Net architectures | Manual expert segmentation of retinal scans | Dice coefficients: Diffusion models (0.81±0.12 SRF, 0.66±0.09 IRF, 0.75±0.11 PED) | [15] [16] |

| Bitumen rejuvenation | Molecular Dynamics | Laboratory diffusion measurements | Simulation results aligned with experimental diffusion trends | [17] |

In biomedical imaging, diffusion models for segmenting retinal fluid biomarkers were benchmarked against state-of-the-art architectures like nnU-Net and TransUNet [15]. While diffusion models showed promising sensitivity, the comprehensive benchmarking revealed that nnU-Net generally provided superior overall performance for optical coherence tomography analysis [16]. This comparative validation guides researchers toward the most suitable methods for specific medical imaging tasks.

Experimental Protocols for Validation

Metallurgical Diffusion Studies

The validation protocol for Fe-Ti interface diffusion exemplifies a rigorous approach [3]:

Computational Methodology:

- Software: LAMMPS MD package

- Potential: Modified Embedded Atom Method (MEAM) for Fe-Ti interactions

- System Setup: Both single-crystal and polycrystalline models with Voronoi tessellation

- Simulation Parameters: NPT and NVT ensembles, time step of 0.001 ps, temperatures of 1123 K and 1223 K

- Analysis: Radial distribution function (RDF) and concentration profiles

Experimental Methodology:

- Materials: Commercially pure titanium and 316 stainless steel

- Sample Preparation: Electrical discharge machining, grinding, and polishing

- Diffusion Welding: Hot isostatic pressing (HIP) at 850°C and 950°C with 30 MPa pressure for 40 minutes

- Characterization: Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) with energy-dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) for interface analysis

This protocol revealed that the MEAM potential reliably reproduced the temperature-dependent diffusion trends observed experimentally, validating its use for Fe-Ti system modeling [3].

Oxide Melt Systems

For high-temperature oxide melts, validation faces unique challenges due to extreme experimental conditions [13]:

Computational Framework:

- Force Field Comparison: Born-Mayer-Huggins (Matsui, Bouhadja) and Buckingham (Guillot) potentials

- Property Evaluation: Density, structure factors, coordination numbers, self-diffusion coefficients

- Reference Data: Ab initio MD simulations and experimental data where available

Validation Metrics:

- Structural Properties: Bond lengths and coordination environments compared to AIMD

- Transport Properties: Self-diffusion coefficients and electrical conductivity

- Thermodynamic Properties: Density and thermal expansion coefficients

This approach revealed that force fields parameterized for crystalline phases often perform poorly for transport properties in melts, highlighting the need for force fields specifically optimized for liquid-state properties [13].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Essential Tools for Diffusion Research Validation

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Simulation Software | LAMMPS, OVITO | MD simulations and trajectory analysis [3] [14] |

| Interatomic Potentials | EAM, MEAM, Buckingham, Born-Mayer-Huggins | Describe atomic interactions in specific material systems [13] [3] |

| Experimental Processing | Hot Isostatic Pressing (HIP), Electrical Discharge Machining | Diffusion couple preparation and bonding [3] |

| Characterization Techniques | SEM, EDS, Neutron Scattering, X-ray Diffraction | Microstructural and compositional analysis of diffusion zones [3] [14] |

| Benchmarking Models | nnU-Net, TransUNet, Swin-UNet | Performance comparison for segmentation tasks [15] |

Visualizing Validation Workflows

Molecular Dynamics Validation Pipeline

MD Validation Process

Force Field Selection and Evaluation

Force Field Selection

Validation bridges the gap between computational prediction and experimental reality, transforming speculative models into trustworthy tools for scientific discovery and technological innovation. The comparative analyses presented demonstrate that rigorous benchmarking against experimental data is essential across fields, whether developing force fields for metallurgical systems or diffusion models for medical image segmentation. As computational power grows and algorithms become more sophisticated, the importance of validation only increases—sophisticated wrong models remain wrong. By adopting the structured validation frameworks, experimental protocols, and visualization approaches outlined in this guide, researchers across disciplines can enhance the reliability of their computational predictions and accelerate the translation of simulation results into real-world applications.

A Dual-Pronged Approach: Techniques for Measuring and Simulating Diffusion

In the context of materials science and drug development, validating molecular dynamics (MD) simulations with robust experimental data is crucial for reliable model development. Time-resolved UV-Visible (UV-Vis) spectroscopy in unstirred environments represents a powerful experimental method for determining diffusion coefficients, providing essential ground-truth data for computational predictions. This technique probes molecular transport by monitoring temporal absorption changes in diffusion-driven systems without convective interference, creating a direct experimental counterpart to MD simulation conditions.

Traditional UV-Vis spectroscopy measures the absorption of discrete wavelengths of ultraviolet or visible light by a sample, providing information about electronic structure and concentration [18]. When extended to time-resolved measurements in unstirred environments, this method can track the diffusion kinetics of molecules, enabling the determination of diffusion coefficients that can be directly compared to those derived from MD simulations. This comparative approach establishes a critical bridge between computation and experiment, allowing researchers to verify the accuracy of their molecular models and force fields.

Fundamental Principles of Diffusion Measurements via UV-Vis Spectroscopy

Theoretical Foundation of Electronic Absorption Spectroscopy

UV-Vis spectroscopy operates on the principle that molecules absorb specific wavelengths of light in the ultraviolet (100-400 nm) and visible (400-800 nm) regions, promoting electrons to higher energy states [19]. The extent of absorption follows the Beer-Lambert law:

A = ε × c × L

Where A is absorbance, ε is the molar absorptivity (L·mol⁻¹·cm⁻¹), c is the concentration (mol·L⁻¹), and L is the path length (cm) [18]. This relationship forms the quantitative basis for monitoring concentration changes in diffusion experiments. The probability of light absorption depends on the chromophore's properties and the transition probability between electronic states [19].

Molar absorptivities vary significantly between chromophores, ranging from 10-100 for weak absorbers to over 10,000 for strongly absorbing compounds with extensive conjugation [19]. This variation enables selective detection of specific compounds in mixtures based on their absorption characteristics, which is particularly valuable in complex biological or pharmaceutical systems relevant to drug development.

Diffusion Principles in Unstirred Environments

In unstirred environments, molecular transport occurs exclusively through diffusion, driven by concentration gradients according to Fick's laws. The fundamental solution to the diffusion equation for a step-function initial concentration profile is described by:

c(y,t) = C(Dt/L²)

Where D is the diffusion coefficient, t is time, L is the characteristic length, and C is a function of the dimensionless parameter τ = Dt/L² [20]. This mathematical framework enables the extraction of diffusion coefficients from time-dependent concentration measurements obtained through UV-Vis spectroscopy.

For a step-function initial condition where concentration changes from c₀ to 0 at position y=0, the concentration at position L/2 and time t can be approximated by:

c(L/2,t) ≈ (1/2) - (1/√π)×(exp(-1/(4τ)))/(2√τ) [20]

This relationship forms the basis for analyzing experimental data in UV-Vis diffusion-ordered spectroscopy (UV/vis-DOSY), where time-dependent absorption spectra are converted into diffusion coefficients [20].

Instrumentation and Methodology

UV-Vis Spectrometer Components

A time-resolved UV-Vis spectrophotometer for diffusion measurements consists of several key components:

- Light Source: Typically a xenon lamp for broad wavelength coverage across UV and visible regions, though instruments may employ separate deuterium (UV) and tungsten/halogen (visible) lamps [18].

- Wavelength Selector: Monochromators with diffraction gratings (typically 1200-2000 grooves/mm) provide precise wavelength selection [18]. Blazed holographic diffraction gratings offer superior quality compared to ruled gratings [18].

- Sample Compartment: Specialized cells with precisely defined path lengths, typically 1 cm for standard measurements [18]. For diffusion studies, customized cells with injection ports and spatial selection capabilities are employed [20].

- Detector: Photomultiplier tubes (PMTs) provide high sensitivity for low-light detection, while photodiodes and charge-coupled devices (CCDs) offer alternative semiconductor-based detection [18].

Table 1: Key Components of a Time-Resolved UV-Vis Spectrophotometer for Diffusion Studies

| Component | Types/Options | Key Characteristics | Application Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Light Source | Xenon lamp, Deuterium/Tungsten combination | Broad spectrum, Intensity stability | Xenon offers continuous spectrum but higher cost and stability issues |

| Wavelength Selection | Monochromators, Absorption filters, Interference filters | Bandwidth, Stray light rejection | Monochromators offer versatility; 1200+ grooves/mm provides good resolution |

| Sample Cell | Standard cuvettes, Custom diffusion cells | Path length, Material (quartz for UV) | Custom cells with flow injection for initial concentration steps |

| Detection System | PMT, Photodiodes, CCD arrays | Sensitivity, Time resolution | PMTs excellent for low light; array detectors enable simultaneous multi-wavelength detection |

For time-resolved measurements specifically, the setup often includes a pulsed laser system for photoactivation of light-sensitive proteins or compounds, with a second monochromator after the sample chamber to prevent scattered laser light from reaching the detector [21].

UV/Vis Diffusion-Ordered Spectroscopy (UV/vis-DOSY) Protocol

UV/vis-DOSY represents a specialized implementation of time-resolved UV-Vis spectroscopy in unstirred environments, enabling simultaneous determination of molecular size and electronic absorption characteristics [20]. The experimental workflow involves:

Sample Preparation:

- Prepare solutions in appropriate solvents (e.g., demineralized water for aqueous systems) at concentrations in the μM range to ensure absorbance values remain within the instrument's dynamic range (typically A < 1) [20] [18].

- Add viscosity modifiers if necessary (e.g., 2.5 g/L polyethylene glycol) to ensure laminar flow conditions during injection [20].

- Degas samples using an ultrasound bath for at least 15 minutes to eliminate bubbles that could cause convective mixing [20].

Instrument Setup:

- Utilize a specialized diffusion cell with two UV-transparent windows (e.g., CaF₂) separated by a precisely thickness-defined spacer (e.g., 2.2 mm Teflon) [20].

- Mount an optical slit on the sample cell to selectively monitor specific regions of the sample volume, typically at the initially solvent-filled portion [20].

- Employ a double syringe pump system for simultaneous injection of sample solution and pure solvent at identical flow rates (e.g., 0.1 mL/min) [20].

Data Acquisition:

- Establish initial flow to create a sharp interface between solution and solvent.

- Stop flow at t=0 to initiate pure diffusion without convection.

- Acquire time-series absorption spectra at regular intervals (e.g., every minute) using automated data collection [20].

- Use array detectors when possible to capture complete spectra simultaneously without wavelength scanning [20].

- Employ an automated shutter between measurements to prevent sample heating from continuous light exposure [20].

Data Analysis:

- Extract time-dependent absorption profiles at characteristic wavelengths for each diffusing species.

- Fit absorption-time data to the diffusion equation solution to determine diffusion coefficients for each species.

- Construct 2D DOSY spectra with absorption wavelength on one axis and diffusion coefficient (size) on the other, enabling spectral separation of mixture components by size [20].

Experimental Data and Comparison with Alternative Methods

Representative Experimental Results

UV/vis-DOSY has been successfully demonstrated for various molecular systems:

Mixed Dye Solutions:

- In a proof-of-concept experiment with rhodamine B and methylene blue mixtures, UV/vis-DOSY clearly distinguished the two compounds based on their diffusion coefficients [20].

- Methylene blue (D ≈ 4.3×10⁻¹⁰ m²/s) diffused significantly faster than rhodamine B (D ≈ 3.1×10⁻¹⁰ m²/s), consistent with their size differences [20].

- The individual UV-Vis spectra of each dye were successfully separated in the 2D DOSY plot despite significant spectral overlap in the conventional absorption spectrum [20].

Biomolecular Systems:

- Studies have successfully applied the technique to solutions containing N-acetyl-L-tryptophanamide, ATP, and lysozyme, resolving these components by size [20].

- For coffee components, the method separated caffeine and chlorogenic acid based on their distinct diffusion coefficients [20].

Table 2: Quantitative Diffusion Data Obtainable via Time-Resolved UV-Vis Spectroscopy

| Analyte/System | Experimental Conditions | Diffusion Coefficient (m²/s) | Comparison with MD Simulations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rhodamine B | Aqueous solution, 25°C | 3.1 × 10⁻¹⁰ | N/A |

| Methylene Blue | Aqueous solution, 25°C | 4.3 × 10⁻¹⁰ | N/A |

| Zn in α-Cu₆₄Zn₃₆ | 400-600°C annealing | Arrhenius behavior with Q=1.37 eV | MD with single vacancy: close match; Higher vacancy concentrations: poor agreement [22] |

| H in Ni-Mn Alloys | Varying Mn content | Non-monotonic dependence on Mn content | MLIP-MD reproduces experimental trend; Reveals competing Mn-H interactions and lattice expansion effects [23] |

Comparison with Alternative Methodologies

Table 3: Comparison of Techniques for Diffusion Coefficient Measurement

| Method | Principle | Size Range | Concentration Range | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time-Resolved UV-Vis (Unstirred) | Temporal absorption changes from diffusion | Molecular to nanoparticle | μM to mM (depends on ε) | Requires chromophores; Limited to transparent solvents |

| NMR-DOSY | Pulsed field gradient spin-echo NMR | Molecular | mM | Lower sensitivity; Requires NMR-active nuclei |

| Traditional LC-UV/Vis | Chromatographic separation with UV detection | Molecular | nM to μM | Requires calibration standards; Stationary phase interactions |

| Tracer Diffusion with SIMS | Stable isotope tracing with depth profiling | Atomic (alloys) | Trace levels | Destructive; Requires specialized isotopes and instrumentation [22] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for UV/Vis Diffusion Studies

| Item | Function/Role | Technical Specifications | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| UV-Grade Cuvettes/Cell Windows | Sample containment for spectral measurements | Quartz for UV range (down to 190 nm); CaF₂ for specialized cells [20] [18] | Standard 1 cm path length most common; Path length reduction for high absorbance samples |

| Chromophore Standards | Method validation and calibration | Compounds with known ε and D (e.g., rhodamine B, methylene blue) [20] | Essential for establishing experimental reliability and comparing with literature |

| High-Purity Solvents | Sample preparation and blanks | UV-transparent (e.g., water, acetonitrile, hexane) [19] | Must have minimal UV absorption in region of interest; Degas before use |

| Precision Syringe Pumps | Controlled fluid delivery for initial conditions | Low flow rates (0.1 mL/min) with high stability [20] | Critical for creating sharp initial interfaces in DOSY experiments |

| Viscosity Modifiers | Control hydrodynamic conditions | Polyethylene glycol (e.g., 4 M, 2.5 g/L) [20] | Ensures laminar flow during injection phase; Minimizes convective disturbances |

| Stable Isotope Tracers | Element-specific diffusion tracking | e.g., ⁷⁰Zn for metallic systems (0.6% natural abundance) [22] | Enables tracer diffusion studies in alloys; Requires SIMS detection |

Experimental Workflow Visualization

Time-resolved UV-Visible spectroscopy in unstirred environments provides a robust experimental methodology for determining diffusion coefficients across diverse systems, from small molecules in solution to atoms in alloy systems. The quantitative data generated through this approach serves as critical validation for molecular dynamics simulations, creating a feedback loop that enhances computational model accuracy.

Recent advances demonstrate successful integration between experimental diffusion measurements and MD simulations across various material systems. In metallic alloys, Zn tracer diffusion studies in α-Cu₆₄Zn₃₆ show close agreement between experimental measurements and MD simulations using appropriate vacancy concentrations [22]. Similarly, for hydrogen diffusion in Ni-Mn random alloys, machine learning interatomic potentials (MLIPs) have enabled MD simulations to quantitatively reproduce the non-monotonic dependence of hydrogen diffusion coefficients on Mn content observed experimentally [23]. These successful integrations highlight how carefully conducted time-resolved UV-Vis measurements in unstirred environments can provide the essential experimental benchmarks needed to develop and validate increasingly accurate computational models for molecular transport.

Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy with attenuated total reflection (ATR-FTIR) has emerged as a powerful analytical technique for investigating complex media across pharmaceutical, materials, and environmental sciences. This method enables direct analysis of samples with minimal preparation by measuring the interaction between infrared light and a sample in contact with an internal reflection element. The technique is particularly valuable for studying diffusion processes, molecular interactions, and compositional changes in multicomponent systems that are challenging to analyze with conventional transmission spectroscopy. Within the context of validating diffusion coefficients from molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, ATR-FTIR provides crucial experimental data through its ability to monitor time-dependent concentration changes and molecular migration in complex matrices [24] [25].

The fundamental principle of ATR-FTIR involves an infrared beam passing through an optically dense crystal with a high refractive index at an angle greater than the critical angle, resulting in total internal reflection. This process generates an evanescent wave that extends beyond the crystal surface into the sample, typically penetrating 0.5-5 micrometers, where it is absorbed by the sample at characteristic frequencies. The depth of penetration depends on the wavelength of light, the refractive indices of the crystal and sample, and the angle of incidence [25]. This limited penetration makes ATR-FTIR exceptionally suited for analyzing highly absorbing samples like aqueous solutions, gels, and complex biological media that would be challenging for transmission FTIR.

Technical Comparison of Spectroscopic Techniques

Performance Comparison with Alternative Methods

ATR-FTIR occupies a distinct position in the spectroscopic toolkit, offering specific advantages and limitations compared to other advanced techniques. The table below provides a systematic comparison of ATR-FTIR against other commonly used spectroscopic methods in complex media analysis.

Table 1: Performance comparison of ATR-FTIR with alternative spectroscopic techniques

| Technique | Spatial Resolution | Sample Preparation | Quantitative Capability | Key Applications in Complex Media | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATR-FTIR | ~1-10 μm (macro-ATR); <2 μm (micro-ATR) | Minimal; may require contact with crystal | Excellent with chemometrics; PLSR R²: 0.91-0.98 [26] | Diffusion coefficients, polymer degradation, in situ reaction monitoring [24] [25] | Limited penetration depth, potential crystal contact issues, diffraction limit |

| Transmission FTIR | Diffraction-limited (~1-10 μm) | Extensive (dilution, KBr pellets) | Good with thin, uniform samples | Bulk composition analysis, quantitative assays [27] | Challenging for thick/absorbing samples, requires precise pathlength control |

| O-PTIR | Sub-micron (<0.5 μm) [28] | Minimal; non-contact | High signal-to-noise ratio equivalent or better than ATR-FTIR [28] | Sub-cellular imaging, heterogeneous materials, heritage science [28] | Limited availability, higher instrumentation costs |

| NIR Spectroscopy | ~1-10 mm | Minimal; non-contact | Excellent with multivariate calibration | Microplastics identification, pharmaceutical quality control [29] | Limited to overtone/combination bands, less specific molecular information |

| Raman Spectroscopy | Diffraction-limited (~0.5-1 μm) | Minimal; non-contact | Good with internal standards | Polymorph characterization, API distribution in formulations [30] | Fluorescence interference, weak signal for some compounds |

Analytical Performance Metrics

The quantitative performance of ATR-FTIR has been rigorously evaluated across various applications. In bioprocess monitoring, ATR-FTIR demonstrated exceptional capability for quantifying metabolites with coefficients of determination (R²) of 0.91-0.98 for glucose and citric acid when combined with partial least squares regression (PLSR) [26]. Similar performance was reported in meat adulteration studies, where ATR-FTIR coupled with artificial neural networks achieved an R² of 0.999 for quantifying chicken in beef mixtures [27]. For microplastics identification in biosolids, ATR-FTIR showed strong correlation coefficients (r > 0.90) for polymers like polyethylene (LDPE, HDPE), though it was less effective for polypropylene and polystyrene compared to NIR spectroscopy [29].

Recent advancements in optical photothermal infrared (O-PTIR) spectroscopy have addressed certain ATR-FTIR limitations, particularly spatial resolution constraints imposed by the IR diffraction limit. O-PTIR provides sub-micron resolution without requiring crystal contact, producing transmission-like FTIR spectra highly favorable for analyzing heritage samples and complex heterogeneous materials [28]. However, ATR-FTIR maintains advantages in instrumental accessibility, established methodologies, and robust quantitative performance for most complex media applications.

Experimental Protocols for Diffusion Studies

Standardized Workflow for Diffusion Coefficient Measurement

The determination of diffusion coefficients using ATR-FTIR follows a systematic experimental approach that integrates measurement with mathematical modeling:

Table 2: Key steps in ATR-FTIR diffusion coefficient measurement

| Step | Procedure | Critical Parameters |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Sample Preparation | Prepare thin, uniform polymer film or complex matrix; ensure flat surface for crystal contact | Film thickness (L), uniformity, absence of defects |

| 2. ATR Configuration | Select appropriate crystal material (diamond, ZnSe, Ge); set incident angle (θ) | Crystal refractive index (n₂), angle of incidence, penetration depth |

| 3. Baseline Acquisition | Collect background spectrum without permeant | Environmental stability, crystal cleanliness |

| 4. Permeant Introduction | Apply diffusant to sample surface opposite crystal contact; initiate timing | Concentration gradient, initial condition (t=0) |

| 5. Time-Series Measurement | Monitor distinctive permeant absorption peak at regular intervals | Peak selection (unique to permeant), time resolution, total duration (tmax) |

| 6. Data Processing | Normalize absorbance values (A(t)/A∞); apply ATR correction | Plateau identification (A∞), Savitzky-Golay smoothing, derivative processing |

| 7. Model Fitting | Fit normalized data to diffusion model using Fieldson & Barbari equation [25] | Diffusion coefficient (D), film thickness (L), crystal parameters |

The fundamental equation describing the normalized absorbance (A(t)/A∞) as a function of diffusion coefficient (D), film thickness (L), and ATR parameters is derived from Crank's diffusion model convoluted with the penetration-depth dependence of the ATR setup [25]:

A(t)/A∞ = 1 - (8γ/(π(1-exp(-Lγ)))) × Σ[exp(-D(2n+1)²π²t/L²) × ( (π(2n+1)/L)exp(-γL) + (-1)^n(2γ) ) / ( (2n+1)(4γ² + (π(2n+1)/L)²) ) ]

Where γ represents the inverse penetration depth, which depends on the wavelength (λ), crystal refractive index (n₂), angle of incidence (θ), and polymer refractive index (n₁).

Protocol for Validating MD Simulations with ATR-FTIR

Integrating ATR-FTIR with molecular dynamics simulations requires careful experimental design to ensure comparable conditions and parameters:

System Matching: Ensure the chemical composition and physical structure of the experimental system match the simulated environment, including polymer chain length, cross-linking density, and permeant characteristics.

Temperature Control: Maintain isothermal conditions throughout the experiment using temperature-controlled accessories, matching simulation temperature settings precisely.

Concentration Calibration: Establish quantitative relationship between ATR-FTIR absorption intensity and permeant concentration through calibration curves using standard solutions.

Time-Scale Alignment: Adjust experimental time resolution (data collection frequency) to capture diffusion kinetics comparable to simulation timeframes, particularly for slow diffusion processes.

Parameter Extraction: Calculate experimental diffusion coefficients from normalized absorbance data using the Fieldson-Barbari method [25], which properly accounts for ATR experimental geometry.

Statistical Comparison: Perform replicate experiments (minimum n=3) to determine measurement uncertainty and enable statistically meaningful comparison with MD simulation results.

In a recent application validating waste tire-derived pyrolytic oil diffusion in aged asphalt binders, this approach successfully combined operando ATR-FTIR measurements with molecular dynamic simulations, demonstrating complementary insights into the diffusion mechanism and molecular interactions [24].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of ATR-FTIR for complex media analysis requires specific materials and reagents optimized for spectroscopic applications.

Table 3: Essential research reagents and materials for ATR-FTIR experiments

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Technical Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| ATR Crystals | Internal reflection element | Diamond (durability, broad range), ZnSe (high sensitivity), Ge (high refractive index) |

| Calibration Standards | Quantitative method validation | Polystyrene film (frequency calibration), concentration standards for Beer's Law plots |

| Spectroscopic Solvents | Sample preparation, cleaning | Deuterated solvents (D₂O, CDCl₃), HPLC-grade solvents (low UV absorption) |

| Polymer Films | Diffusion study substrates | Uniform thickness (5-100 μm), defined composition, optical quality |

| Chemometric Software | Multivariate data analysis | PLS regression, principal component analysis, artificial neural networks |

| Reference Materials | Spectral validation | USP compendial standards, well-characterized model compounds |

The selection of appropriate ATR crystals represents a critical consideration. Diamond crystals provide exceptional durability for analyzing hard materials and are resistant to damage from pressure, while ZnSe crystals offer higher sensitivity for biological samples but require careful handling due to their fragile nature. Germanium crystals with their high refractive index enable shallow penetration depths ideal for surface analysis and high-resolution imaging applications [25] [30].

Integration with Computational Methods

Bridging Experimental and Computational Approaches

The forward and inverse modeling framework provides a powerful approach for integrating ATR-FTIR experimental data with computational methods. The forward problem involves predicting vibrational spectra from known molecular structures identified through biomolecular simulations, while the inverse problem focuses on inferring structural ensembles directly from experimental IR spectra [31]. This bidirectional framework enables rigorous validation of MD simulations against experimental data.

Two primary computational approaches are employed for spectral prediction: normal-mode analysis (NMA), which calculates vibrational frequencies from the Hessian matrix of equilibrium structures, and Fourier-transformed dipole autocorrelation analysis, which computes spectra directly from MD simulations [31]. While NMA provides straightforward assignment of vibrational bands to specific nuclear motions, the dipole autocorrelation approach naturally incorporates conformational heterogeneity and temperature effects but presents greater challenges for spectral interpretation.

Workflow for MD-ATR-FTIR Integration

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow combining ATR-FTIR experiments with molecular dynamics simulations for validating diffusion coefficients and molecular interactions:

This integrated approach enables researchers to solve both the forward problem (predicting ATR-FTIR spectra from MD-generated structures) and the inverse problem (inferring structural ensembles from experimental spectra). The comparison step provides critical validation of molecular dynamics force fields and simulation parameters, particularly for complex media where intermolecular interactions significantly influence diffusion behavior [24] [31].

Machine learning methods are increasingly enhancing this integration, with ML-force fields and dipole models trained on density functional theory data enabling MD simulations at near-DFT accuracy but substantially reduced computational cost [31]. These advances facilitate more precise spectral predictions that can be directly compared with experimental ATR-FTIR data for validating diffusion mechanisms in complex media.

Applications in Complex Media Analysis

Pharmaceutical and Biopharmaceutical Applications

ATR-FTIR has become an indispensable tool in pharmaceutical development, particularly for characterizing active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) and final drug products. The technique enables identification of polymorphic forms, quantification of crystalline vs. amorphous content, and monitoring of solid-state transformations during processing and storage [30]. These applications are critical since different solid forms of a drug can display significantly different physical and chemical properties, including dissolution behavior and bioavailability [30].

In biopharmaceutical applications, ATR-FTIR has been successfully employed for high-throughput screening of microbial bioprocesses, simultaneously quantifying intra- and extracellular metabolites along with substrate consumption [26]. This unified analytical approach provides comprehensive process information that traditionally required multiple analytical techniques, significantly accelerating bioprocess development. The technique has demonstrated exceptional correlation with reference methods like HPLC, with R² values of 0.91-0.98 for key metabolites including glucose and citric acid [26].

Materials and Environmental Applications

Beyond pharmaceutical applications, ATR-FTIR provides critical insights into material behavior and environmental contaminants. In asphalt research, operando ATR-FTIR has elucidated diffusion mechanisms of waste tire-derived pyrolytic oils used as rejuvenators, revealing how molecular polarity, size, and C/H ratios affect diffusional behavior [24]. This molecular-level understanding enables rational design of more sustainable pavement materials with enhanced self-healing capabilities.

For environmental monitoring, ATR-FTIR has proven effective for identifying microplastics in complex matrices like biosolids, showing high correlation with polyethylene (LDPE, HDPE), polystyrene (PS), and polyamide (PA) polymers [29]. The technique enables rapid screening of environmental samples with minimal preparation, though complementary use with NIR spectroscopy may be necessary for comprehensive polymer identification, particularly for polypropylene and polystyrene [29].

ATR-FTIR spectroscopy represents a versatile and powerful analytical technique for investigating complex media across diverse scientific disciplines. Its ability to provide molecular-level information with minimal sample preparation, combined with robust quantitative capabilities when paired with chemometric analysis, makes it particularly valuable for studying diffusion processes and molecular interactions. The technique's strengths in analyzing highly absorbing samples, including aqueous systems and complex biological matrices, position it as an essential tool for validating molecular dynamics simulations and extracting diffusion coefficients from experimental data.