Beyond the Timescale Barrier: Advanced Strategies to Overcome Sampling Limitations in Molecular Dynamics Simulations

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations are a cornerstone of modern computational biology and drug discovery, providing atomic-level insights into biomolecular function.

Beyond the Timescale Barrier: Advanced Strategies to Overcome Sampling Limitations in Molecular Dynamics Simulations

Abstract

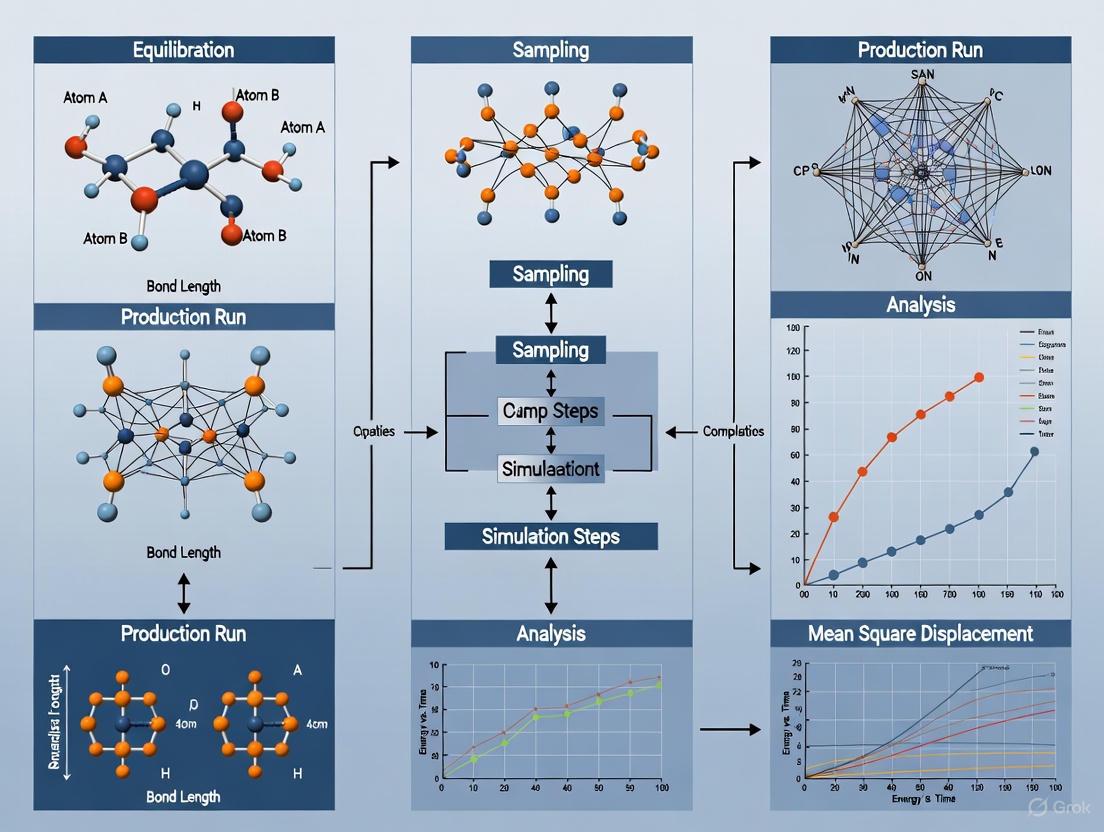

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations are a cornerstone of modern computational biology and drug discovery, providing atomic-level insights into biomolecular function. However, their predictive power is fundamentally constrained by sampling limitations, which prevent the simulation of rare but critical events like protein folding, ligand unbinding, and large conformational changes. This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the latest strategies to overcome these barriers. We first explore the foundational roots of sampling challenges, including high energy barriers and finite computational resources. We then detail a suite of solutions, from established physics-based enhanced sampling techniques to transformative AI and machine learning methods. The article further offers practical troubleshooting advice for optimizing simulations and a framework for validating results against experimental data. By synthesizing these approaches, we demonstrate how overcoming sampling limitations is unlocking new frontiers in the rational design of drugs and nanomaterials.

The Core Challenge: Understanding the Roots of Sampling Limitations in MD

Technical Support & Troubleshooting Hub

This support center provides solutions for researchers tackling the fundamental challenge of accessing biologically relevant timescales in molecular dynamics (MD) simulations.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My MD simulations cannot reach the millisecond-plus timescales needed to observe protein-ligand unbinding. What accelerated sampling methods can I use? A1: Several enhanced sampling methods can help bridge this timescale gap. You can leverage collective variables (CVs) or use novel unbiased methods. The table below compares key approaches:

| Method | Type | Key Principle | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|

| dcTMD + Langevin [1] | Coarse-grained | Applies a constraint force to pull a system, decomposing work into free energy and friction; used to run efficient Langevin simulations [1]. | Predicting binding/unbinding kinetics (seconds to minutes) [1]. |

| Unbiased Enhanced Sampling [2] | Unbiased | Iteratively projects sampling data into multiple low-dimensional CV spaces to guide further sampling without biasing the ensemble [2]. | Complex systems where optimal CVs are unknown; provides thermodynamic and kinetic properties [2]. |

| Machine-Learning Integrators [3] | AI-driven | Uses structure-preserving (symplectic) maps to learn the mechanical action, allowing for much larger integration time steps [3]. | Long-time-step simulations while conserving energy and physical properties [3]. |

Q2: How can I analyze the massive amount of data generated from long-timescale or multiple simulation trajectories? A2: The key is to use specialized, scalable analysis libraries. We recommend the following tools and techniques:

| Tool/Technique | Function | Key Feature |

|---|---|---|

| MDAnalysis [4] | Python library for analyzing MD trajectories | Reads multiple trajectory formats; provides efficient tools to analyze atomic coordinates and dynamics [4]. |

| Interactive Visual Analysis [5] | Visual analysis of simulation embeddings | Uses Deep Learning to embed high-dimensional data for easier visualization and analysis [5]. |

| Virtual Reality [5] | Immersive visualization of MD trajectories | Allows for an intuitive and interactive way to explore simulation data in a 3D space [5]. |

Q3: My enhanced sampling simulation is not converging or exploring the correct states. What could be wrong? A3: This is often related to the choice of Collective Variables (CVs). The diagram below outlines a troubleshooting workflow for this common issue.

Q4: How can I effectively visualize my simulation results to communicate findings? A4: Effective visualization is crucial. Adhere to these best practices for color and representation:

- Use Intuitive Color Palettes: Leverage established color palette types for different kinds of data [6] [7]:

- Qualitative: Use distinct colors for categorical data (e.g., different protein chains).

- Sequential: Use a single-color gradient for ordered, continuous data (e.g., energy values).

- Diverging: Use two contrasting colors to show deviation from a central value (e.g., positive/negative charge).

- Limit Colors: Use seven or fewer colors in a single visualization to avoid overwhelming the viewer [7].

- Ensure Accessibility: Test visualizations with colorblindness simulators (like Coblis) to ensure they are interpretable by a wide audience [6].

- Leverage Advanced Tools: Consider web-based tools for sharing or VR for immersive, interactive exploration of complex systems [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

This table details key computational "reagents" and their functions for tackling the timescale problem.

| Item | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Structure-Preserving (Symplectic) Map [3] | A geometric integrator that conserves energy and physical properties over long simulation times, enabling larger time steps. |

| Collective Variable (CV) [2] | A low-dimensional descriptor (e.g., a distance or angle) used to guide enhanced sampling simulations and monitor slow biological processes. |

| Langevin Equation [1] | A stochastic equation of motion that coarse-grains fast degrees of freedom into friction and noise, drastically accelerating dynamics. |

| MDAnalysis Library [4] | A core Python software library for processing and analyzing molecular dynamics trajectories and structures. |

| Free Energy Landscape [2] | A map of the system's thermodynamics as a function of CVs, revealing stable states and the barriers between them. |

High Energy Barriers and the Inaccessibility of Rare Events

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the main molecular simulation techniques used to overcome sampling limitations?

Molecular simulations primarily use two categories of methods to sample molecular configurations: Molecular Dynamics (MD) and Monte Carlo (MC). MD numerically integrates equations of motion to generate a dynamical trajectory, allowing investigation of structural, dynamic, and thermodynamic properties. MC uses probabilistic rules to generate new configurations, producing a sequence of states useful for calculating structural and thermodynamic properties, but it lacks any concept of time and cannot provide dynamical information [8].

FAQ 2: Why are rare events and high energy barriers a significant problem in molecular dynamics?

Conventional MD techniques are limited to relatively short timescales, often microseconds or less. Many essential conformational transitions in proteins, such as folding or functional state changes, occur on timescales of milliseconds to seconds or longer and involve the rare crossing of high energy barriers. These infrequent events are critical for understanding protein function but are often not observed in standard simulations due to these timescale limitations [9] [8].

FAQ 3: What is Accelerated Molecular Dynamics (aMD) and how does it help?

Accelerated Molecular Dynamics (aMD) is an enhanced sampling technique that improves conformational sampling over conventional MD. It applies a continuous, non-negative boost potential to the original energy surface. This boost raises energy wells below a predefined energy level, effectively reducing the height of energy barriers and making transitions between states more frequent. This allows the simulation to explore conformational space more efficiently and observe rare events that would be inaccessible in standard MD timeframes [9].

FAQ 4: What common errors occur during system preparation in GROMACS?

Common errors during the pdb2gmx step in GROMACS include:

Residue 'XXX' not found in residue topology database: The chosen force field lacks parameters for a molecule in your structure.Long bonds and/or missing atoms: Atoms are missing from the input PDB file, which disrupts topology building.WARNING: atom X is missing in residue...: The structure is missing atoms that the force field expects, often hydrogens or atoms in terminal residues.Atom X in residue YYY not found in rtp entry: A naming mismatch exists between atoms in your structure and the force field's building blocks [10].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Poor Conformational Sampling in Trajectories

Problem: Your simulation remains trapped in a single conformational state and fails to transition to other relevant states, even when such transitions are expected.

Diagnosis and Solutions:

Diagnosis 1: Insufficient Simulation Time The simulation may not have run long enough to observe a rare but spontaneous barrier crossing.

- Solution: Extend the simulation time if computationally feasible. For straightforward sampling issues, tools like StreaMD can automate the process of continuing or extending existing simulations [11].

Diagnosis 2: The System is Dominated by a High Energy Barrier If the barrier is significantly higher than the thermal energy (kBT), transitions will be exceedingly rare.

- Solution: Implement an enhanced sampling method.

- Accelerated MD (aMD): This method applies a boost potential to the entire potential energy surface or specific components like dihedral angles, smoothing the landscape and accelerating transitions [9].

- Gaussian accelerated MD (GaMD): This method, available in software like BIOVIA Discovery Studio, adds a harmonic boost potential, enabling simultaneous unconstrained enhanced sampling and free energy calculations [12].

- Replica Exchange MD (REMD): This technique runs multiple replicas of the system at different temperatures and periodically exchanges configurations, helping to overcome local energy barriers.

- Solution: Implement an enhanced sampling method.

Recommended Workflow: The following diagram illustrates a logical workflow for diagnosing and addressing poor sampling.

Issue 2: System Preparation and Topology Errors

Problem: Errors occur during the initial setup of the simulation, particularly when using pdb2gmx in GROMACS to generate topology files.

Diagnosis and Solutions:

Diagnosis: Missing Residue or Atom Parameters The force field you selected does not contain definitions for a specific residue (e.g., a non-standard ligand or cofactor) or there is a mismatch in atom names.

- Solution A (Standard Residues): For standard amino acids or nucleotides, use the

-ignhflag to allowpdb2gmxto ignore existing hydrogens and add them correctly according to the force field. Ensure terminal residues are properly specified (e.g., asNALAfor an N-terminal alanine in AMBER force fields) [10]. - Solution B (Non-Standard Molecules): For ligands, drugs, or unusual cofactors, you cannot use

pdb2gmxdirectly.- Use specialized tools to generate the topology and parameters for the molecule. Tools like CHARMM-GUI, ACEMD, or OpenMM can assist with this [11] [8].

- Manually create an Include Topology File (

.itp) for the molecule. - Integrate the

.itpfile into your main topology (.top) file using an#includestatement.

- Solution A (Standard Residues): For standard amino acids or nucleotides, use the

Diagnosis: Force Field Not Found

- Solution: The error "No force fields found" indicates an improperly configured GROMACS environment. Ensure the

GMXDATAenvironment variable is set correctly, pointing to the directory containing the force field (.ff) subdirectories. You may need to reinstall GROMACS [10].

- Solution: The error "No force fields found" indicates an improperly configured GROMACS environment. Ensure the

Recommended Workflow: The diagram below outlines the decision process for resolving common topology errors.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Software for MD Simulations

The table below summarizes key software tools used in the field for molecular mechanics modeling and simulation, highlighting their primary functions and licensing models [13] [12].

| Software Name | Key Simulation Capabilities | License Type | Key Features / Use-Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| GROMACS | MD, Min, REM | Free Open Source (GPL) | High-performance MD, extremely fast for biomolecules, comprehensive analysis tools [13] [11]. |

| AMBER | MD, Min, REM, QM-MM | Proprietary, Free open source | Suite of biomolecular simulation programs, includes extensive force fields and analysis tools [13]. |

| CHARMM | MD, Min, MC, QM-MM | Proprietary, Commercial | Versatile simulation program, often used with BIOVIA Discovery Studio and NAMD [13] [12]. |

| NAMD | MD, REM | Free academic use | High-performance, parallel MD; excellently scaled for large systems; integrated with VMD for visualization [13] [12]. |

| OpenMM | MD, Min, MC, REM | Free Open Source (MIT) | Highly flexible, scriptable in Python, optimized for GPU acceleration [13] [11]. |

| BIOVIA Discovery Studio | MD (CHARMm/NAMD), Min, GaMD | Proprietary, Commercial | Comprehensive GUI, integrates simulation with modeling and analysis, user-friendly [12]. |

| StreaMD | Automated MD setup/run | Python-based tool | Automates preparation, execution, and analysis of MD simulations across multiple servers [11]. |

Experimental Protocols: Key Methodologies

Protocol 1: Setting up and Running an Accelerated MD (aMD) Simulation

This protocol outlines the key steps for applying the aMD method, which is designed to improve sampling of rare events [9].

- System Preparation: Prepare your protein-ligand complex or other system as for a conventional MD simulation. This includes solvation, ionization, and energy minimization. Automated tools like StreaMD can handle these steps [11].

- Conventional MD Equilibration: Run a short conventional MD simulation to equilibrate the system and collect potential energy statistics.

- Calculate Boost Parameters: From the short cMD, calculate the average dihedral potential energy

⟨V(r)⟩. The boost energyEis typically set close to or slightly above this average to ensure acceleration. Theαparameter modulates the roughness of the modified potential surface. - Run aMD Production: Execute the production aMD simulation using the calculated boost parameters. The simulation will now sample configurations on the modified, "boosted" potential energy surface.

- Reweighting (Post-Processing): To recover the true canonical ensemble, each frame of the aMD trajectory must be reweighted using the Boltzmann factor of the boost potential applied at that step,

eβΔV[r]. This corrects for the bias introduced by the acceleration.

Protocol 2: Gaussian accelerated MD (GaMD) for Free Energy Calculation

GaMD is a variant that facilitates both enhanced sampling and free energy calculation [12].

- System Preparation: Standard preparation of the molecular system.

- Conventional MD Equilibration: Run a short cMD to equilibrate and collect potential energy statistics.

- GaMD Parameterization: The software automatically parametrizes the harmonic boost potential based on the collected statistics. This step determines the parameters needed to ensure the boost potential is Gaussian-distributed, which simplifies subsequent free energy analysis.

- GaMD Equilibration and Production: Run the GaMD simulation using the calculated boost parameters.

- Free Energy Estimation: The free energy landscape can be estimated directly from the GaMD trajectory using statistical reweighting techniques, such as the Boltzmann reweighting method, allowing you to project the landscape onto reaction coordinates of interest.

Data Presentation: Boost Potential Equations in aMD

The evolution of aMD methods has led to different equations for the boost potential, each designed to address specific sampling challenges. The table below summarizes three key implementations [9].

| Boost Potential | Mathematical Form | Key Feature | Primary Challenge |

|---|---|---|---|

| Original (ΔVa) | ΔVa(r) = (E - V(r))2 / (α + (E - V(r))) | Raises energy wells below a threshold energy E. |

Difficult statistical reweighting due to large boosts in deep energy minima. |

| Barrier-Lowering (ΔVb) | ΔVb(r) = (V(r) - E)2 / (α + (V(r) - E)) | Lowers energy barriers above a threshold energy E. |

Oversamples high-energy regions in large systems like proteins. |

| New Regulated (ΔVc) | ΔVc(r) = (V(r) - E)2 / [ (α1 + (V(r) - E)) * (1 + e-(E2 - V(r))/α2) ] | Introduces a second energy level E2 to protect very high barriers from being oversampled. |

Requires tuning two energy parameters (E1, E2) and two modulation parameters (α1, α2). |

Computational Cost and Resource Constraints in Long-Timescale Simulations

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations have become an indispensable tool for investigating biological processes and guiding drug discovery. However, simulating phenomena on biologically relevant timescales—much longer than 10 picoseconds—presents immense challenges related to computational cost, sampling efficiency, and data management. This technical support center provides targeted guidance for researchers navigating these constraints, offering practical solutions to advance your simulations beyond current limitations.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What defines a "long-timescale" simulation, and why is it so challenging? In computational photochemistry, "long timescales" are loosely defined as periods much longer than 10 ps [14]. The primary challenge is that simulating these timescales with conventional methods requires unrealistic computational resources. The costs stem from the need to perform quantum mechanical calculations for excited state energies, forces, and state couplings over millions of time steps [14].

How can I reduce the computational cost of my electronic structure calculations? There are three main strategies to reduce these costs:

- Use parameterized/approximated electronic structure methods, such as FOMO-CI, OM2/CI, or time-dependent DFTB (TD-DFTB), which replace computationally intensive steps with precomputed quantities [14].

- Employ parameterized Hamiltonian models, like the spin-boson Hamiltonian (SBH) or vibronic coupling (VC) models, which bypass the high costs of solving the full quantum electronic problem [14].

- Implement machine learning (ML) as a surrogate model for quantum mechanical predictions, which can learn potential energy surfaces and drastically accelerate calculations [14] [15].

What are the main data challenges in large-scale simulations? Large-scale simulations generate terabyte to petabyte-scale trajectory data, creating significant logistical challenges for storage, management, and dissemination [16]. Furthermore, the wealth of information in these datasets is often underutilized because traditional manual analysis becomes impossible. This presents a classical data science challenge ideally suited for machine learning and artificial intelligence techniques [16].

How do enhanced sampling methods help overcome timescale limitations? Enhanced sampling techniques allow simulations to overcome high energy barriers that separate different conformational states—rare transitions that would normally require immensely long simulation times to observe. Methods like replica-exchange molecular dynamics (REMD), metadynamics, and simulated annealing algorithmically improve sampling efficiency, enabling the study of slow biological processes such as protein folding and ligand binding [17] [18].

Can specialized hardware really make a difference? Yes, significantly. The adoption of graphics processing units (GPUs) has dramatically accelerated MD calculations [15]. Furthermore, purpose-built supercomputers like the Anton series, which use application-specific integrated circuits (ASICs), have achieved a 460-fold speedup for a 2.2-million-atom system compared to general-purpose supercomputers [15]. These hardware advances are crucial for accessing longer, biologically relevant timescales.

Troubleshooting Common Simulation Issues

Problem: Simulation Crashes Due to "Out of Memory" Errors

- Error Message:

Out of memory when allocating...[10] - Possible Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: The program is attempting to allocate more memory than is available, often during trajectory analysis [10].

- Solution 1: Reduce the scope of your analysis by selecting a smaller number of atoms for processing [10].

- Solution 2: Shorten the length of the trajectory file being analyzed in a single operation [10].

- Solution 3: Check for unit errors (e.g., confusion between Ångström and nm) during system setup that may have created an excessively large simulation box [10].

- Solution 4: Use a computer with more RAM or install more memory in your current system [10].

Problem: Residue or Ligand Not Recognized by the Force Field

- Error Message:

Residue 'XXX' not found in residue topology database[10] - Possible Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: The force field you selected does not have a database entry for the residue or molecule "XXX" [10].

- Solution 1: Check if the residue exists in the database under a different name and rename your molecule accordingly [10].

- Solution 2: Find a topology file (

*.itp) for the molecule from a reliable source and include it in your main topology file [10]. - Solution 3: Parameterize the residue yourself (requires significant expertise) or search the literature for published parameters compatible with your force field [10].

- Solution 4: Consider using a different force field that already includes parameters for your molecule [10].

Problem: Missing Atoms or Incorrect Bonding During Topology Generation

- Error Message:

WARNING: atom X is missing in residue XXX...orLong bonds and/or missing atoms[10] - Possible Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: The initial coordinate file (e.g., PDB file) is incomplete or has atom names that do not match the expectations of the force field's residue template (

rtp) file [10]. - Solution 1: Use the

-ignhflag withpdb2gmxto ignore existing hydrogen atoms and allow the tool to add hydrogens with correct nomenclature [10]. - Solution 2: For terminal residues, ensure the nomenclature matches the force field requirements (e.g.,

NALAfor an N-terminal alanine in AMBER force fields) [10]. - Solution 3: Check for

REMARK 465andREMARK 470entries in your PDB file, which indicate missing atoms. These atoms must be modeled back in using external software before topology generation [10]. - Note: Avoid using the

-missingflag, as it produces unrealistic topologies for standard biomolecules [10].

- Cause: The initial coordinate file (e.g., PDB file) is incomplete or has atom names that do not match the expectations of the force field's residue template (

Problem: Visualization Shows Broken Bonds During a Trajectory

- Symptoms: In visualization software like VMD, bonds between atoms appear to break when playing the trajectory [19].

- Possible Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Visualization software guesses bonds based on ideal distances. If a bond length becomes "strange" in a simulation frame, the visualizer may not display it. The actual chemical bonds defined in your topology cannot break during a classical MD simulation [19].

- Solution 1: Load an energy-minimized frame of your system alongside the trajectory for comparison [19].

- Solution 2: Visually inspect the

[ bonds ]section of your topology file to confirm the bond in question is properly defined [19].

Optimization and Resource Allocation

Strategies for Efficient Long-Timescale Sampling

| Strategy | Description | Key Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Machine Learning Surrogates | Using ML models to learn potential energy surfaces from quantum mechanical data, bypassing expensive on-the-fly calculations. | ANI-2x force fields [15], Autoencoders for collective variables [15]. |

| Enhanced Sampling | Accelerating the crossing of high energy barriers to sample rare events. | Metadynamics, Replica-Exchange MD (REMD), Simulated Annealing [17] [15]. |

| Conformational Ensemble Enrichment | Generating diverse protein conformations for drug discovery without ultra-long simulations. | Coupling MD with AlphaFold2 variants, Clustering from shorter simulations [15]. |

| Optimal Resource Allocation | Intelligently distributing a fixed computational budget (total simulation time) across different parameters for maximum accuracy. | Gaussian Process (GP) based optimization frameworks [20]. |

Quantitative Factors Influencing Computational Cost

The table below summarizes key factors that impact the resource requirements of molecular simulations, helping you plan your projects effectively.

| Factor | Impact on Computational Cost | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| System Size (N atoms) | Calculations often scale with N, NlogN, or N² depending on the algorithm [10]. | Electrostatic calculations (PME) typically scale as NlogN. |

| Simulation Length (T) | Cost increases linearly with the number of time steps. | Longer simulations are essential for capturing slow biological processes [15]. |

| Electronic Structure Method | Ab initio QM > Semi-empirical QM > Machine-Learned QM > Classical Force Fields [14]. | ML force fields offer a promising balance of accuracy and speed [15]. |

| Enhanced Sampling | Increases cost per time step but drastically reduces the total simulated time needed to observe an event. | The net effect is often a massive reduction in wall-clock time for studying rare events [17]. |

| Path Length (L) (Adiabatic quantum dynamics) | Computational cost for maintaining adiabaticity can scale superlinearly, e.g., ~ L log L [21]. | Relevant for state preparation in quantum simulations. |

Workflow for Optimal Time Allocation

The following diagram illustrates a Gaussian Process-based optimization framework for allocating a fixed computational budget across multiple simulation parameters, such as temperature.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

The table below lists key computational "reagents" and their functions for setting up and running advanced molecular dynamics simulations.

| Item | Function / Purpose | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| GROMACS | A versatile software package for performing MD simulations. | Highly optimized for CPU and GPU performance; widely used in academia [10]. |

| AMBER/CHARMM Force Fields | Class I empirical potentials defining bonded and non-bonded interactions for biomolecules. | AMBER and CHARMM use Lorentz-Berthelot combining rules for Lennard-Jones parameters [22]. |

| Lennard-Jones Potential | Approximates non-electrostatic (van der Waals) interactions between atom pairs. | Expressed as V(r)=4ε[(σ/r)¹² - (σ/r)⁶]. The repulsive r⁻¹² term can overestimate pressure [22]. |

| Lorentz-Berthelot Rules | Combining rules for LJ interactions between different atom types: σᵢⱼ = (σᵢᵢ + σⱼⱼ)/2; εᵢⱼ = √(εᵢᵢ × εⱼⱼ). | Default in many force fields (AMBER, CHARMM). Known to sometimes overestimate the well depth εᵢⱼ [22]. |

| Buckingham Potential | An alternative to LJ for van der Waals interactions, using an exponential repulsive term. | More realistic but computationally more expensive. Risk of "Buckingham catastrophe" at very short distances [22]. |

| Particle Mesh Ewald (PME) | An algorithm for efficient calculation of long-range electrostatic interactions. | Essential for maintaining accuracy with periodic boundary conditions; scales as NlogN [22]. |

| Gaussian Process Regression | A nonlinear regression technique used to build surrogate models for expensive simulations. | Enables optimal allocation of computational time across parameter space with uncertainty estimates [20]. |

| Plumed | A plugin for enhancing sampling and analyzing MD simulations. | Commonly used for implementing metadynamics and other advanced sampling techniques [17]. |

The Critical Role and Pitfalls of Collective Variable (CV) Selection

In molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, collective variables (CVs) are low-dimensional parameters that describe the essential dynamics of a system without significant loss of information [23]. They are crucial for generating reduced representations of free energy surfaces and calculating transition probabilities between different metastable states [23]. The choice of CVs is fundamental for overcoming sampling limitations, as they drive enhanced sampling methods like metadynamics and umbrella sampling, allowing researchers to study rare events such as protein folding and ligand binding that occur on timescales beyond the reach of conventional MD [24] [25].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the most common mistake in initial CV selection? The most common mistake is selecting a CV that is degenerate, meaning a single CV value corresponds to multiple structurally distinct states of the system [24]. For example, using only the radius of gyration might group a partially folded state and a misfolded compact state under the same value, preventing the method from accurately resolving the free energy landscape.

2. How can I determine if my CV is causing poor sampling convergence? A key indicator is observing hysteresis, where the free energy profile differs depending on whether the simulation is started from state A or state B [24]. Additionally, if your enhanced sampling simulation fails to reproduce the expected equilibrium between known metastable states after reasonable simulation time, the CVs may not be capturing the true reaction coordinate [25].

3. My CV seems physically sound, but the simulation won't cross energy barriers. Why? The CV might be physically sound but not mechanistically relevant. It may describe the end states well but not capture the specific atomic-scale interactions that need to break or form to facilitate the transition [23] [24]. For instance, a distance CV may be insufficient if the transition also requires a side-chain rotation or the displacement of a key water molecule.

4. When should I use abstract machine learning-based CVs over geometric ones? Geometric CVs (distances, angles) are preferred for simpler systems where the slow degrees of freedom are known and intuitive [23]. Abstract CVs (from PCA, autoencoders, etc.) are powerful for complex systems with high-dimensional conformational changes where the relevant dynamics are not obvious. However, they can be less interpretable, so their application should be justified [23].

5. How does solvent interaction impact CV choice for conformational changes? Ignoring solvent can be a critical pitfall. For processes like protein folding, the egress of water from the hydrophobic core and the replacement of protein-water hydrogen bonds with protein-protein bonds are key steps [24]. CVs that explicitly distinguish protein-protein from protein-water hydrogen bonds can significantly improve state resolution and convergence [24].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Degenerate Collective Variable

Symptoms:

- Inability to distinguish between critical intermediate states.

- Poor convergence and overlapping states in the free energy landscape.

- The simulation oscillates between states without settling into defined minima.

Solution: Implement a bottom-up strategy to construct complementary, bioinspired CVs [24].

- Featurization: From short unbiased simulations of the end states (e.g., folded and unfolded), automatically collect microscopic features. Focus on:

- Feature Filter: Use a Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA)-like criterion to filter the most relevant features that best distinguish your states of interest [24].

- CV Construction: Construct two intuitive CVs:

- CV Combination: Use these CVs simultaneously in your enhanced sampling method, or merge them as a simple linear combination [24].

Problem: Inadequate Sampling of Rare Events

Symptoms:

- The simulation remains trapped in a single metastable state.

- Calculated free energy differences and barriers are not reproducible across independent runs.

- Failure to observe a known conformational transition or binding/unbinding event.

Solution: Adopt a hybrid sampling scheme to mitigate dependencies on suboptimal CVs.

- Technique Selection: Combine multiple enhanced sampling methods. The OneOPES method is an example that hybridizes:

- Protocol:

- Set up multiple replicas of your system.

- Apply the hybrid scheme (e.g., OneOPES) even with non-optimal CVs. The combination of methods makes the requirement for perfect CVs less severe, leading to more robust convergence, especially for complex systems like the 20-residue TRP-cage mini-protein [24].

Problem: Poor Convergence in Free Energy Calculations

Symptoms:

- The free energy profile continues to shift significantly with simulation time.

- High uncertainty in the estimation of free energy barriers between states.

- Results are sensitive to the initial configuration of the simulation.

Solution: Systematically validate and refine your CVs and simulation parameters.

- Validation: Compare your results with long, unbiased MD simulations (if available) or experimental data (e.g., NMR spectroscopy) [24] [25].

- CV Refinement: If discrepancies exist, refine your CVs by:

- Convergence Testing: Run multiple independent enhanced sampling simulations (e.g., quintuplicates) from different starting points. True convergence is indicated when all replicates yield statistically identical free energy profiles [24].

Key Data and Metrics

Table 1: Common Types of Collective Variables and Their Characteristics

| CV Type | Examples | Primary Applications | Key Advantages | Common Pitfalls |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Geometric | Distance, Dihedral Angle, Radius of Gyration, RMSD [23] | Ligand unbinding, side-chain rotation, loop dynamics [23] | Physically intuitive, simple to implement and compute [23] | High degeneracy in complex systems; may miss key microscopic details [24] |

| Abstract (Linear) | Principal Component Analysis (PCA), Independent Component Analysis (ICA) [23] | Identifying large-scale concerted motions from an unbiased trajectory [23] | Data-driven; can capture correlated motions without prior knowledge [23] | Can be difficult to interpret physically; linear combinations may not suffice for complex transitions [23] |

| Abstract (Non-Linear) | Autoencoders, t-SNE, Diffusion Map [23] | Complex conformational changes with non-linear dynamics [23] | Can capture complex, non-linear relationships in high-dimensional data [23] | High computational cost; risk of overfitting; can produce uninterpretable CVs [23] |

Table 2: Diagnostic Metrics for CV Performance

| Metric | Description | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Hysteresis | Difference in free energy profile when sampling from opposite directions (e.g., folded vs. unfolded) [24] | Strong hysteresis indicates a poor CV that does not align with the true reaction coordinate [24]. |

| State Resolution | Ability of the CV to cleanly separate known metastable states in the free energy landscape [24]. | Poor resolution (overlapping states) suggests CV degeneracy [24]. |

| Convergence Rate | The simulation time required for free energy estimates to stabilize within a statistical error [25]. | Slow convergence can be due to poor CVs, insufficient sampling, or high energy barriers not overcome by the method [25]. |

| Committor Value | The probability that a trajectory initiated from a configuration will reach one state before another [24]. | For an ideal CV, configurations with the same CV value have a committor probability of 0.5 (the isocommittor surface) [24]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Building Bottom-Up CVs for Protein Folding

Objective: To construct and validate interpretable CVs for simulating protein folding that explicitly capture hydrogen bonding and side-chain packing [24].

Materials:

- Molecular system: Solvated protein of interest.

- Software: MD engine (e.g., GROMACS, AMBER) coupled with an enhanced sampling plugin (e.g., PLUMED).

- Hardware: High-performance computing (HPC) cluster with multiple CPU/GPU nodes.

Methodology:

- End-State Sampling: Run short (nanoseconds) conventional MD simulations starting from the crystallographic native state and a well-solvated unfolded state.

- Feature Identification: From these trajectories, automatically extract:

- All potential protein-protein and protein-water hydrogen bonds.

- All side-chain contacts within a defined cutoff distance.

- Feature Selection: Apply a feature filter (e.g., LDA) to identify which hydrogen bonds and side-chain contacts are most discriminatory between the folded and unfolded ensembles.

- CV Definition: Define the final CVs as:

- HB-CV = Σ(Native Protein-Protein H-Bonds) - Σ(Non-Native Protein-Protein H-Bonds)

- SC-CV = Σ(Native Side-Chain Contacts) - Σ(Non-Native Side-Chain Contacts)

- Enhanced Sampling: Use these CVs in an OPES or metadynamics simulation to explore the folding landscape. Run multiple independent replicas to ensure convergence [24].

Protocol 2: Hybrid Sampling with OneOPES

Objective: To achieve robust sampling and convergence for complex transitions where optimal CVs are not known a priori [24].

Materials:

- As in Protocol 1.

Methodology:

- Initial Setup: Prepare the system and choose a set of reasonable, though potentially suboptimal, CVs (e.g., radius of gyration, native contacts).

- Replica Configuration: Launch multiple replicas of the simulation.

- Apply OneOPES: Implement the hybrid OneOPES scheme, which concurrently applies:

- OPES Explore: To bias the simulation along the chosen CVs and encourage escape from local minima.

- OPES MultiThermal: To run replicas at different temperatures, accelerating the crossing of high energy barriers.

- Replica Exchange: Periodically attempt to swap configurations between replicas based on their thermodynamic weights, ensuring better global sampling [24].

- Analysis: Reconstruct the free energy landscape from the combined trajectory data and validate against any available reference data.

Workflow Visualization

CV Selection and Validation Workflow

Troubleshooting Poor CV Performance

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Software and Analysis Tools for CV Discovery

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function | Relevance to CV Discovery |

|---|---|---|---|

| PLUMED [23] | Software Plugin | Enhanced Sampling & CV Analysis | Industry-standard for defining, applying, and analyzing a vast array of CVs within MD simulations. |

| MDAnalysis [23] | Python Library | Trajectory Analysis | Provides tools to compute geometric CVs and perform preliminary analysis to inform CV selection. |

| GROMACS (with plugins) [23] | MD Engine | Molecular Dynamics Simulations | High-performance MD software, often integrated with PLUMED, to run simulations biased by CVs. |

| Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA) [24] | Statistical Method | Dimensionality Reduction & Classification | Used to automatically filter and select the most relevant features from a pool for CV construction. |

| Time-Lagged Independent Component Analysis (TICA) [23] | Algorithm | Identification of Slow Dynamics | A linear method to find the slowest modes (good CV candidates) in high-dimensional simulation data. |

| Variational Autoencoders (VAE) [23] | Machine Learning Model | Non-Linear Dimensionality Reduction | Can be trained to find non-linear, low-dimensional representations (CVs) of molecular configurations. |

Inherent Force Field Inaccuracies and Their Impact on Sampling

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What are the primary sources of inaccuracy in classical force fields? Classical force fields employ simplified empirical functions to describe atomic interactions, which inherently introduces approximations. Major sources of inaccuracy include: the use of fixed point charges, which cannot capture electronic polarization effects; simplified functional forms for bonded and non-bonded terms (e.g., harmonic bonds instead of more realistic anharmonic potentials); and the parameterization process itself, which may not fully represent all possible molecular environments or chemistries encountered in a simulation [22] [26]. These limitations can lead to errors in calculated energies and forces.

2. How do force field inaccuracies directly impact conformational sampling? Inaccuracies in the force field distort the potential energy surface (PES). This means the relative energies of different molecular conformations are computed incorrectly. As a result, the simulation may over-stabilize certain non-native conformations or create artificial energy barriers that hinder transitions to other relevant states [17] [27]. Since sampling relies on accurately overcoming energy barriers to explore phase space, an inaccurate PES can trap the simulation in incorrect regions, preventing the observation of biologically critical motions or leading to incorrect population statistics [17] [28].

3. My simulation runs without crashing. Does this mean my force field is accurate? No, a stable simulation is not a guarantee of accuracy. Molecular dynamics engines will integrate the equations of motion based on the provided forces, even if those forces are physically unrealistic due to an inadequate force field or model [29]. A simulation can appear stable while sampling an incorrect conformational ensemble. Proper validation against experimental data (e.g., NMR observables, scattering data, or crystallographic B-factors) is essential to build confidence in the results [29].

4. Can machine learning interatomic potentials (MLIPs) solve the problem of force field inaccuracies? MLIPs are a powerful emerging technology that can achieve near-quantum accuracy for many systems. However, they are not a panacea. MLIPs can still exhibit significant discrepancies when predicting atomic dynamics, defect properties, and rare events, even when their overall average error on standard test sets is very low [27]. Their accuracy is entirely dependent on the quality and breadth of the training data, and they may fail for atomic configurations far from those included in their training set [27].

5. What is the difference between sampling error and force field error? These are two fundamentally different sources of uncertainty in simulations. Force field error is a systematic error arising from inaccuracies in the model itself—the mathematical functions and parameters used to describe atomic interactions. Sampling error, on the other hand, is a statistical uncertainty that arises because the simulation was not run long enough or with sufficient breadth to adequately represent the true equilibrium distribution of the system, even if the force field were perfect [30] [28]. It is crucial to distinguish between the two when interpreting results.

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Poor Sampling and Non-Physical Trapping

Problem Description The simulation becomes trapped in a specific conformational substate and fails to transition to other known or biologically relevant states, even during long simulation times. This can manifest as an unrealistically stable non-native structure or a lack of expected dynamics.

Diagnostic Steps

- Check Multiple Observables: Do not rely solely on root-mean-square deviation (RMSD). Monitor a diverse set of metrics simultaneously, such as radius of gyration, solvent accessible surface area, specific dihedral angles, and hydrogen bond networks. A flat RMSD curve can be misleading if other properties are still evolving [29].

- Calculate Effective Sample Size: Use statistical tools to estimate the effective sample size of your trajectory. This quantifies how many statistically independent configurations you have sampled. An effective sample size below ~20 is a strong indicator of poor sampling and unreliable estimates [28].

- Run Multiple Replicas: Initiate several independent simulations from the same starting structure but with different initial velocities. If all replicas become trapped in the same non-physical state, it strongly suggests a force field bias. If they become trapped in different states, it indicates a general sampling problem with high energy barriers [29].

Resolution Strategies

- Employ Enhanced Sampling: Utilize algorithms like replica-exchange molecular dynamics (REMD), metadynamics, or simulated annealing to help the system overcome energy barriers. Metadynamics, for instance, works by adding a history-dependent bias potential that "fills up" free energy minima, encouraging the system to explore new regions [17].

- Validate with Experiment: Compare simulation-derived observables (e.g., NMR order parameters, NOE distances) with experimental data. A systematic discrepancy often points to a force field issue that needs to be addressed [29].

- Review Force Field Selection: Ensure the chosen force field is appropriate for your specific molecule (e.g., protein, nucleic acid, carbohydrate, organic ligand). Using a protein force field for a carbohydrate system can lead to significant errors [29].

Issue 2: Energy and Force Discrepancies in MLIPs

Problem Description A Machine Learning Interatomic Potential (MLIP) reports low root-mean-square errors (RMSE) on its test set, but when used in molecular dynamics simulations, it produces incorrect physical properties, such as diffusion coefficients, vacancy formation energies, or migration barriers [27].

Diagnostic Steps

- Go Beyond Average Errors: Low average force errors can mask large inaccuracies for specific, critically important atoms. Conventional testing on random structural splits is insufficient [27].

- Analyze Forces on Key Atoms: Identify atoms involved in rare events (e.g., a diffusing atom or a transitioning dihedral) and calculate the force error specifically for these atoms. This "rare-event force error" is often a better predictor of dynamic performance than the global average [27].

- Test on Targeted Configurations: Create a dedicated test set containing snapshots from ab initio molecular dynamics of key processes like defect migration or chemical reactions, which may be underrepresented in standard training sets [27].

Resolution Strategies

- Augment Training Data: Enrich the MLIP's training dataset with configurations that highlight the problematic rare events or transition states.

- Use Improved Metrics for Selection: When optimizing and selecting between different MLIP models, use metrics based on the force errors of rare-event atoms rather than just the overall RMSE. This directly targets the improvement of dynamic properties [27].

- Adjust Loss Functions: Modify the training loss function to assign higher weights to these critical configurations or atomic forces, forcing the model to prioritize accuracy in these regions.

Quantitative Data on Force Field and MLIP Errors

The following table summarizes common types of inaccuracies and their quantitative impact as observed in simulation studies.

Table 1: Quantified Inaccuracies in Interatomic Potentials

| Error Type | System Studied | Reported Error Metric | Impact on Sampled Properties |

|---|---|---|---|

| MLIP Force Error | Si (Various MLIPs) [27] | Force RMSE: 0.15 - 0.4 eV/Å (on vacancy structures) | Errors in vacancy formation and migration energies, despite vacancies being in training data. |

| MLIP Rare Event Error | Al [27] | Force MAE: 0.03 eV/Å (global) | Activation energy for vacancy diffusion error of 0.1 eV (DFT: 0.59 eV). |

| MLIP Generalization Error | Si (Interstitial) [27] | Energy offset: 10-13 meV/atom lower than DFT | Poor prediction of dynamics for structures (interstitials) not included in training data. |

| Force Field Functional Error | General [22] | N/A | Lennard-Jones repulsive term (r⁻¹²) can overestimate system pressure. Buckingham potential risk of "catastrophe" at short distances. |

Experimental Protocol for Validating Sampling Quality

Objective: To determine if a simulation has produced a statistically well-sampled ensemble for a given observable and to estimate the uncertainty of the computed average.

Materials:

- A molecular dynamics trajectory that has reached a stable equilibrium.

- Software for time-series analysis (e.g.,

gmx analyzein GROMACS, or custom scripts in Python/MATLAB).

Methodology:

- Equilibration Assessment: Visually inspect the time series of key observables (potential energy, temperature, RMSD, etc.) to identify a point where the system has stabilized. Discard all data prior to this point as equilibration.

- Calculate the Statistical Inefficiency:

- For an observable ( x(t) ), compute the autocorrelation function ( C(t) = \frac{\langle x(\tau)x(\tau+t)\rangle - \langle x \rangle^2}{\langle x^2 \rangle - \langle x \rangle^2} ).

- Integrate this function to obtain the correlation time, ( \tau ). The statistical inefficiency, ( g ), is approximately ( 2\tau ) [30] [28].

- Compute Effective Sample Size and Uncertainty:

- The effective sample size is ( N{eff} = N / g ), where ( N ) is the total number of time points.

- The standard uncertainty (experimental standard deviation of the mean) is ( s(\bar{x}) = s(x) / \sqrt{N{eff}} ), where ( s(x) ) is the standard deviation of the observable [30].

- Interpretation: An ( N_{eff} ) of less than ~20 indicates that the sampling for that observable is poor and the calculated average is unreliable. The uncertainty ( s(\bar{x}) ) should be reported alongside all simulated observables [28].

Workflow Diagram: Diagnosis and Resolution of Sampling Issues

Figure 1: A diagnostic workflow for resolving sampling problems, helping to distinguish between force field inaccuracies and inherent sampling limitations.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 2: Essential Tools for Addressing Sampling and Force Field Challenges

| Tool / Resource | Function / Purpose | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Enhanced Sampling Algorithms | Accelerate exploration of configuration space by helping systems overcome energy barriers. | Metadynamics to study a ligand unbinding pathway; REMD to study protein folding [17]. |

| Statistical Inefficiency Analysis | Quantify the number of statistically independent samples in a trajectory to assess sampling quality and estimate uncertainty [30] [28]. | Determining if a 100 ns simulation is long enough to reliably compute the average radius of gyration of a protein. |

| Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials (MLIPs) | Provide a more accurate representation of the quantum mechanical potential energy surface at a fraction of the computational cost. | Simulating a chemical reaction or a defect in a material where classical force fields are known to be inaccurate [27]. |

| Multi-Replica Simulations | Generate multiple independent trajectories to assess reproducibility and distinguish force field bias from sampling limitations [29]. | Running 10 independent 100 ns simulations to see if a protein consistently folds into the same non-native structure. |

| Experimental Validation Datasets | Experimental data used to benchmark and validate simulation results. | Comparing simulated NMR scalar coupling constants or NOE distances to experimental values to test force field accuracy [29]. |

A Toolkit of Solutions: Enhanced Sampling and AI-Driven Methods

FAQs: Core Concepts and Method Selection

Q1: What is the fundamental goal of enhanced sampling methods in molecular dynamics? The primary goal is to overcome the timescale limitation of standard MD simulations by facilitating the exploration of configuration space that is separated by high energy barriers. This allows for the accurate calculation of free energies and the observation of rare events, such as conformational changes or ligand binding, that would otherwise be impractical to simulate [31] [32].

Q2: How do I choose between Umbrella Sampling, Metadynamics, and Replica Exchange? The choice depends on the system and the property of interest. The table below summarizes the key considerations:

Table: Guide for Selecting an Enhanced Sampling Method

| Method | Best For | Key Requirement | Primary Output |

|---|---|---|---|

| Umbrella Sampling | Calculating free energy along a pre-defined reaction pathway or collective variable (CV) [33]. | Well-defined CV and initial pathway; good overlap between sampling windows [33]. | Potential of Mean Force (PMF). |

| Metadynamics | Exploring unknown free energy surfaces and finding new metastable states [32]. | Selection of one or a few CVs that describe the slow degrees of freedom [32]. | Free Energy Surface (FES). |

| Replica Exchange | Improving conformational sampling for systems with multiple, complex metastable states (e.g., protein folding). | Careful selection of replica parameters (e.g., temperature range) to ensure sufficient exchange rates [32]. | Boltzmann-weighted ensemble of configurations. |

Q3: What is a Collective Variable (CV) and why is it so important? A Collective Variable (CV) is a function of the atomic coordinates (e.g., a distance, angle, or dihedral) that is designed to describe the slow, relevant motions of the system during a process of interest [34]. The efficiency of methods like Umbrella Sampling and Metadynamics is critically dependent on the correct choice of CVs; poor CVs will not accelerate the relevant dynamics and can lead to inaccurate results [32].

Q4: What does "sufficient overlap" mean in Umbrella Sampling? In Umbrella Sampling, the simulation is divided into multiple "windows," each with a harmonic restraint applied at a different value of the CV. Sufficient overlap means that the probability distributions of the CV from adjacent windows must overlap significantly. This overlap is crucial for methods like the Weighted Histogram Analysis Method (WHAM) to correctly stitch the data together into a continuous free energy profile. Insufficient overlap leads to gaps in the data and high uncertainty in the calculated free energy [33].

Troubleshooting Guides

Umbrella Sampling

Table: Common Umbrella Sampling Issues and Solutions

| Problem | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Poor Overlap between Windows | Windows are too far apart; force constant is too low [33]. | Decrease the spacing between window centers; increase the harmonic force constant. |

| High Uncertainty in PMF | Inadequate sampling within each window; poor overlap [33]. | Run longer simulations for each window; ensure sufficient overlap as above. |

| gmx wham fails or gives erratic PMF | Insufficient overlap; or one or more windows did not sample the restrained region. | Check the individual window trajectories and histograms. Redo pulling simulation to generate better initial configurations for problematic windows. |

The following diagram illustrates the key steps and potential troubleshooting points in a typical Umbrella Sampling workflow.

Replica Exchange (REMD)

Table: Common Replica Exchange Issues and Solutions

| Problem | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low Acceptance Probability | Replicas are too far apart in temperature or Hamiltonian space [32]. | Increase the number of replicas to decrease the spacing between them. |

| System becomes unstable at high temperatures | The force field may be poorly parameterized for high temperatures; or the system was not properly equilibrated. | Check system setup and equilibration. Consider using Hamiltonian Replica Exchange instead of Temperature REMD. |

| One replica gets "stuck" | The energy landscape is too rugged, even at higher replicas. | Use a different enhanced sampling method for the high-temperature replicas, or employ Hamiltonian replica exchange with a smoothing potential [32]. |

Metadynamics

Table: Common Metadynamics Issues and Solutions

| Problem | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Free energy estimate does not converge | Hill deposition rate is too high; or the simulation time is too short. | Use a lower hill deposition rate or well-tempered metadynamics; run the simulation longer. |

| System is trapped in a metastable state | The chosen CVs are not sufficient to describe the reaction. | Reconsider the choice of CVs; consider using multiple CVs. |

| Sampling is inefficient in high-dimensional CV space | The number of CVs is too high, leading to the "curse of dimensionality." | Use a maximum of 2-3 CVs; consider machine-learning techniques for finding optimal low-dimensional CVs [35]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Software

This table lists key software tools and their functions relevant to implementing the enhanced sampling methods discussed.

Table: Key Software Tools for Enhanced Sampling Simulations

| Tool Name | Primary Function | Relevant Methods | Key Feature |

|---|---|---|---|

| GROMACS [36] | Molecular Dynamics Engine | All methods | High-performance MD simulator; includes built-in tools for pulling simulations and umbrella sampling analysis [33] [36]. |

| PLUMED [34] | Enhanced Sampling Plugin | All methods | A versatile plugin for implementing a wide variety of CVs and enhanced sampling methods; works with many MD engines. |

| PySAGES [34] | Enhanced Sampling Library | All methods | Python-based library with full GPU support for advanced sampling methods; offers a user-friendly interface and analysis tools [34]. |

| VMD [37] | Visualization & Analysis | All methods | Visualize trajectories, analyze structures, and create publication-quality images and movies. |

| SSAGES [34] | Advanced Sampling Suite | All methods | The predecessor to PySAGES, designed for advanced general ensemble simulations on CPUs. |

The following diagram outlines a general workflow for setting up and running an enhanced sampling simulation, integrating the tools from the toolkit.

Leveraging Coarse-Grained (CG) Models to Access Larger Systems and Longer Timescales

Fundamental Concepts and FAQs

Q1: What is a Coarse-Grained (CG) model in molecular dynamics? A: A Coarse-Grained (CG) model is a simplified representation of a molecular system where groups of atoms are clustered into single interaction sites, often called "beads." This reduction in the number of degrees of freedom significantly lowers computational cost compared to all-atom models, enabling simulations of larger biomolecular systems over longer, biologically relevant timescales (microseconds to milliseconds) [38] [39].

Q2: What is the physical basis for the forces in CG-MD? A: The motion of CG sites is governed by the potential of mean force, with additional friction and stochastic forces that represent the integrated effects of the omitted atomic degrees of freedom. This makes Langevin dynamics a natural choice for describing the motion in CG simulations [39].

Q3: What are the main categories of CG models? A: CG models can be broadly divided into:

- Molecular-Mechanics (MM)-based: Use simplified, physics-inspired energy terms between beads. They are often used to study large-scale conformational changes and assembly processes [38].

- Folding-based (or Structure-based): These models, like Gō-like models, bias the energy landscape toward known native structures. Multi-basin versions can simulate transitions between different conformational states [38].

- Machine Learning (ML)-based: Use neural networks trained on all-atom simulation data to learn accurate and thermodynamically consistent CG force fields, offering a path to high accuracy and transferability [40] [41].

Q4: What does "bottom-up" and "top-down" coarse-graining mean? A: In a "bottom-up" approach, the CG model is parameterized to reproduce specific properties from a more detailed, all-atom model or quantum mechanical calculation, such as through force matching. A "top-down" scheme, in contrast, is parameterized to reproduce experimental or macroscale emergent properties [41].

Practical Implementation and Troubleshooting

Troubleshooting Common CG Simulation Issues

Problem: Simulation Instability in Large Solvent-Free Systems

- Symptoms: Membrane poration, unphysical undulations, or system failure beyond a critical size in solvent-free CG lipid models [42].

- Solution: Systematically optimize the lipid model parameters to enhance stability for large-scale simulations. This may involve refining interaction potentials to correctly capture the mechanical properties of the bilayer [42].

Problem: Poor Load Balancing and Low Performance

- Symptoms: Drastic slowdown in simulations with non-uniform particle density, such as in liquid-liquid phase separation (LLPS) systems with dense protein droplets [43].

- Solution: Use a dynamic load-balancing domain decomposition scheme. Software like GENESIS CGDYN employs a cell-based kd-tree method to redistribute computational workload among processes, ensuring high efficiency even when particle densities change rapidly [43].

Problem: Unphysical Bonding in Visualization

- Symptoms: Visualization software shows bonds between atoms that are not bonded according to your topology.

- Solution: This is typically a visualization artifact. Most visualization tools determine bonds based on interatomic distances. The true bonding information is defined by your topology file. If the software can read the simulation input file (e.g., a

.tprfile in GROMACS), the displayed bonds will match the topology [44].

Problem: Molecules "Leaving" the Simulation Box When Using PBC

- Symptoms: When visualizing a trajectory, molecules appear to fragment or drift out of the primary simulation box.

- Solution: This is due to molecules crossing periodic boundaries and "wrapping" around to the other side. It is not a simulation error. You can correct the visualization for analysis by using a tool like

trjconvin GROMACS to make molecules whole again [44].

Key Software Tools for Coarse-Grained Modeling

The table below summarizes popular software tools capable of running CG-MD simulations, their key features, and considerations for use.

Table 1: Software Tools for Coarse-Grained Molecular Dynamics

| Software | Key Features and Strengths | Notable CG Models Supported | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| GENESIS [45] [43] | Highly parallelized; multi-scale MD; specialized CG engine (CGDYN) with dynamic load balancing for heterogeneous systems. | AICG2+, HPS, 3SPN, SPICA | Optimized for modern supercomputers; suitable for very large, non-uniform systems. |

| GROMACS [44] | High performance and versatility; extensive tools for setup and analysis; robust parallelization. | MARTINI | A preferred choice for extensive simulations on clusters. |

| LAMMPS [46] | High flexibility and scalability; supports a wide range of potentials; easily customizable. | Various, including user-defined models | Advantageous for custom simulations and novel model development. |

| OpenMM [46] | Ease of use; high-level Python API; strong GPU acceleration. | Various | Excellent for rapid prototyping and simulations on GPU hardware. |

Advanced Methodologies and Protocols

Machine Learning for Coarse-Grained Force Fields

Recent advances use supervised machine learning to create accurate CG force fields. The core of this "bottom-up" approach is the force matching scheme, which can be formulated as a machine learning problem [41].

The objective is to learn a CG potential energy function (U(\mathbf{x}; \boldsymbol{\theta})) that minimizes the loss: [ L(\boldsymbol{\theta}) = \frac{1}{3nM} \sum{c=1}^{M} \| \boldsymbol{\Xi} \mathbf{F}(\mathbf{r}c) + \nabla U(\boldsymbol{\Xi}\mathbf{r}c; \boldsymbol{\theta}) \|^2 ] where (\boldsymbol{\Xi} \mathbf{F}(\mathbf{r}c)) is the mapped all-atom force (the instantaneous coarse-grained force) for configuration (c), and (\nabla U) is the force predicted by the CG model [40] [41]. Architectures like CGSchNet integrate graph neural networks to learn molecular features automatically, improving transferability across molecular systems [41].

Diagram: Workflow for Building a Machine-Learned Coarse-Grained Potential

Protocol: System Setup for Residue-Level CG-MD

This protocol outlines the steps for setting up a CG-MD simulation for a protein system, such as the miniprotein Chignolin, using a residue-level model [41].

- Obtain Initial Structure: Download an atomic-resolution structure (e.g., from the Protein Data Bank) in PDB format.

- Generate CG Topology and Coordinates: Use a CG model tool to convert the all-atom structure into a CG representation.

- Define the Force Field: Specify the functional forms and parameters for the CG potential energy function. This includes:

- Bonded potentials: Harmonic bonds and angles, and often a dihedral potential, to maintain chain integrity and chain stereochemistry [40].

- Non-bonded potentials: Effective pair potentials between non-bonded beads to capture hydrophobic, electrostatic, and other interactions. In ML-based approaches, this is handled by the neural network [40] [41].

- Energy Minimization: Perform an energy minimization to remove any bad contacts in the initial CG structure.

- Equilibration: Run a short CG-MD simulation in the NVT (constant Number, Volume, Temperature) and/or NPT (constant Number, Pressure, Temperature) ensembles to equilibrate the system density and temperature.

- Production MD: Launch a long production simulation to collect data for analysis. The integration time step can often be enlarged (e.g., 10-20 fs) compared to all-atom MD due to the smoother potential energy landscape [38].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Resources for Coarse-Grained Molecular Dynamics Research

| Resource / Reagent | Function / Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| MARTINI Force Field [46] | A widely used generic CG force field for biomolecules and solvents. | Simulating lipid bilayers, membrane proteins, and protein-protein interactions. |

| AICG2+ Model [43] | A structure-based coarse-grained model for proteins. | Studying protein folding and conformational dynamics of folded biomolecules. |

| HPS Model [43] | An implicit-solvent CG model for intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs). | Investigating liquid-liquid phase separation (LLPS) of proteins like TDP-43. |

| 3SPN Model [43] | A series of CG models for nucleic acids (DNA and RNA). | Simulating DNA structure, mechanics, and protein-DNA complexes. |

| Neural Network Potential (NNP) [40] | A machine-learned force field trained on all-atom data. | Creating thermodynamically accurate and transferable models for multiple proteins. |

| GENESIS CGDYN [43] | An MD engine optimized for large-scale, heterogeneous CG systems. | Simulating the fusion of multiple IDP droplets or large chromatin structures. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My AI-generated conformational ensemble lacks structural diversity and seems stuck in a narrow region of space. What could be the cause?

A1: This is often a problem of limited or biased training data. If the molecular dynamics (MD) data used to train your model does not adequately represent the full energy landscape, the AI cannot learn to sample from it effectively [48]. To address this:

- Verify Training Data: Ensure your training set includes MD simulations initiated from different starting structures and with different random seeds to maximize initial conformational variety [48].

- Inspect the Latent Space: For generative models like Internal Coordinate Net (ICoN), examine the 3D latent space. A clustered or sparse latent space indicates poor representation of the underlying conformational diversity [49].

- Data Augmentation: Consider augmenting your training data with conformations from enhanced sampling methods or experimental data to fill in the gaps [48].

Q2: How can I validate that my deep learning model has learned physically realistic principles and not just memorized the training data?

A2: Validation against independent, non-training data is crucial. A robust workflow includes:

- Quantitative Metrics: Calculate standard metrics like the Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) between original and reconstructed structures to ensure the model's accuracy. For example, a valid ICoN model should reconstruct heavy atoms with an RMSD of less than 1.3 Å [49].

- Comparison with Experiment: Validate the final AI-sampled ensemble against experimental observables, such as data from Small-Angle X-Ray Scattering (SAXS) or Circular Dichroism (CD) [48].

- Thermodynamic Stability: Check the thermodynamic feasibility of novel "synthetic" conformations generated by the model. They should correspond to low-energy states on the energy landscape [49].

Q3: What are the most common pitfalls when integrating a pre-trained deep learning model into an existing MD analysis workflow?

A3:

- Input/Output Mismatch: Ensure your molecular representation (e.g., Cartesian coordinates, internal coordinates) matches the model's expected input format. Incompatible formats will lead to errors [49].

- Software and Hardware Dependencies: Pre-trained models often require specific software libraries (e.g., TensorFlow, PyTorch) and may be optimized for GPU acceleration. Confirm your computing environment meets these requirements [50].

- Force Field Compatibility: Be aware that models trained on data from one molecular force field (e.g., CHARMM, AMBER) may not generalize well to data generated with another due to differences in energy parametrization [51].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Poor Reconstruction Fidelity in Autoencoder-Based Models

Symptoms: High root mean square deviation (RMSD) when comparing original molecular structures to their reconstructed versions from the latent space.

Diagnosis and Solutions:

| Step | Action | Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Check the dimensionality of the latent space. | An excessively low-dimensional latent space may not have enough capacity to encode the structural information. Increasing the dimension may improve fidelity [49]. |

| 2 | Analyze the training data diversity. | If the training set lacks conformational variety, the model cannot learn a robust encoding. Incorporate more diverse MD trajectories or enhanced sampling data [48]. |

| 3 | Validate the internal coordinate representation. For models using vector Bond-Angle-Torsion (vBAT), ensure periodicity issues are correctly handled during the conversion to and from Cartesian coordinates [49]. | Accurate reconstruction of both backbone and sidechain dihedral angles, crucial for capturing large-scale motions and specific interactions like salt bridges [49]. |

Problem: Failure to Generate Novel, Thermodynamically Stable Conformations

Symptoms: The generative model only produces conformations nearly identical to those in the training set, failing to discover new low-energy states.

Diagnosis and Solutions:

| Step | Action | Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Examine the sampling method in the latent space. | Simple random sampling may be inefficient. Use interpolation between known data points in the latent space to systematically explore and generate novel, valid conformations [49]. |

| 2 | Check for over-regularization. | Overly strict regularization terms in the model's loss function can constrain the latent space too much, limiting its generative diversity. Tuning regularization parameters can help [50]. |

| 3 | Implement a hybrid physics-AI validation. | Use a physics-based force field to perform quick energy minimization or short MD refinements on generated structures. This filters out physically unrealistic conformations and confirms stability [48]. |

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol 1: Workflow for Conformational Ensemble Generation with ICoN

This protocol details the use of the Internal Coordinate Net (ICoN) model for efficient sampling of highly dynamic proteins, such as Intrinsically Disordered Proteins (IDPs) or amyloid-β [49].

1. System Preparation and MD Simulation for Training Data

- Objective: Generate a foundational MD trajectory.

- Steps:

- Obtain an initial protein structure from the PDB or via homology modeling.

- Use a system builder like CHARMM-GUI to solvate the protein and generate input files for MD packages like GROMACS, NAMD, or AMBER [51].

- Run a classical MD simulation. For highly flexible systems, this may need to be on the microsecond timescale to capture relevant motions [48].

- Extract a sufficient number of frames (e.g., 10,000 for a protein like Aβ42) for training and validation [49].

2. ICoN Model Training

- Objective: Train the deep learning model to learn the physical principles of conformational changes.

- Steps:

- Feature Conversion: Convert the Cartesian coordinates of the MD frames into a vBAT (vector Bond-Angle-Torsion) representation. This internal coordinate system is invariant to translation and rotation and efficiently describes dihedral rotations [49].

- Network Training: Train the ICoN autoencoder. The encoder reduces the high-dimensional vBAT data into a low-dimensional (e.g., 3D) latent space, and the decoder reconstructs the original conformation from this space.

- Validation: Validate the trained model by reconstructing held-out MD frames and calculating the heavy-atom RMSD. A successful model for a system like Aβ42 should achieve an average RMSD of < 1.3 Å [49].

3. Generation and Analysis of Synthetic Conformations

- Objective: Use the trained model to sample new conformations.

- Steps:

- Latent Space Sampling: Sample new points in the trained latent space, often via interpolation between existing data points.

- Conformation Generation: Decode the sampled points from the latent space back to full-atom Cartesian coordinates using the ICoN decoder.

- Post-processing Analysis: Cluster the generated synthetic conformations and analyze them for novel structural features (e.g., new salt bridges or hydrophobic contacts) not present in the original training data [49].

The following diagram illustrates the core workflow and data transformation of the ICoN method:

Protocol 2: Deep Learning-Based Analysis of MD Trajectories for Mutation Impact

This protocol uses convolutional neural networks (CNNs) to classify functional states and predict the impact of mutations from MD data, as demonstrated in studies of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein [52].

1. Feature Engineering from MD Trajectories

- Objective: Create a rotation- and translation-invariant representation of the protein structure for robust deep learning.

- Steps:

- Generate Distance Maps: For each frame in the MD trajectory, calculate the inter-residue distance map (DM). A DM is a 2D matrix where each element (i, j) represents the distance between the Cα atoms of residue i and residue j.

- Alternative - Pixel Maps: Some studies convert atomic coordinates into RGB components to create pixel maps, though this requires careful preprocessing to remove rotational and translational bias [52].

2. CNN Model Training and Interpretation

- Objective: Train a classifier to identify conformational patterns linked to specific mutations.

- Steps:

- Label Data: Assign class labels to trajectory frames based on the simulated mutant type (e.g., high-affinity vs. low-affinity).

- Train CNN: Train a convolutional neural network (e.g., a 3D ResNet for spatiotemporal patterns) using the distance maps as input to predict the class labels [52].

- Model Interpretation: Use techniques like saliency maps to identify which residues in the distance map most strongly influence the model's prediction, highlighting regions critical for the mutant's functional impact [52].

The logical process for this analysis is shown below:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Key computational tools and resources for AI-driven conformational sampling.

| Tool / Resource | Function / Description | Relevance to Field |

|---|---|---|

| ICoN (Internal Coordinate Net) [49] | A generative deep learning model that uses internal coordinates (vBAT) to efficiently sample protein conformational ensembles. | Rapidly identifies thousands of novel, thermodynamically stable conformations for highly flexible systems like IDPs. |

| CHARMM-GUI [51] | A versatile web-based platform for setting up and simulating complex biomolecular systems for various MD engines (e.g., GROMACS, NAMD, AMBER). | Provides the initial structures and simulation parameters needed to generate training data for deep learning models. |

| CREST [53] | The Conformer-Rotamer Ensemble Sampling Tool, which uses a genetic algorithm (GFN-xTB) for exhaustive conformational searching of (bio)molecules. | Useful for generating diverse initial structures for small molecules or peptides prior to more detailed MD and AI sampling. |

| GNINA [50] | A molecular docking software that utilizes convolutional neural networks for scoring protein-ligand complexes, improving virtual screening accuracy. | Represents the application of DL to a related problem (docking), showcasing the integration of AI into structure-based workflows. |