Beyond the Hype: Building Robust MLIPs for Reliable Molecular Dynamics in Drug Discovery

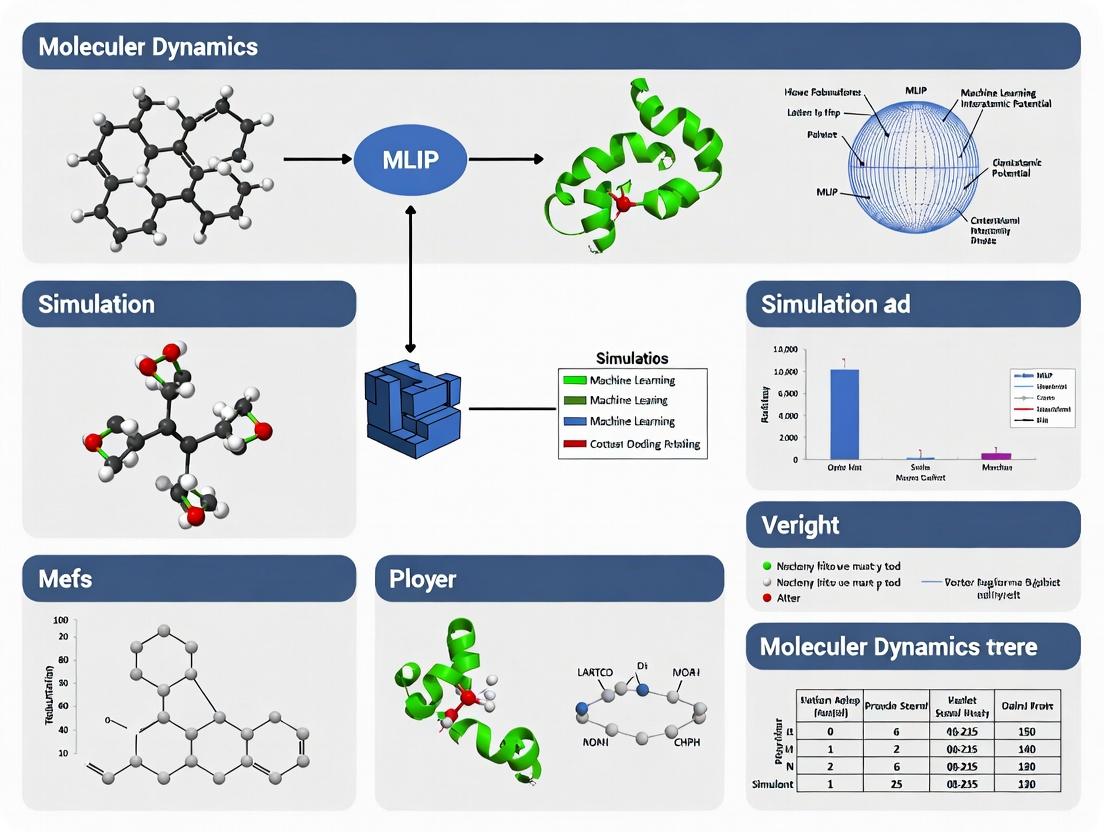

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on ensuring the robustness of Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials (MLIPs) in molecular dynamics (MD) simulations.

Beyond the Hype: Building Robust MLIPs for Reliable Molecular Dynamics in Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on ensuring the robustness of Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials (MLIPs) in molecular dynamics (MD) simulations. We explore the fundamental challenges and promises of MLIPs, detail practical methodologies for application in biomolecular systems, address critical troubleshooting and optimization strategies for production runs, and provide a framework for rigorous validation and comparative analysis against traditional force fields. The content synthesizes current best practices to enable reliable, accurate, and computationally efficient simulations of proteins, ligands, and complex biological environments for accelerating therapeutic discovery.

The Promise and Peril of MLIPs: Understanding Robustness in Molecular Simulation

MLIP Robustness Support Center

Troubleshooting Guide

Issue 1: Poor Energy Prediction on Unseen Structures

- Symptoms: High errors (MAE > 10 meV/atom) on validation sets with new chemical environments.

- Diagnosis: Likely a transferability failure due to limited training data diversity or architecture constraints.

- Resolution: Implement active learning. Use the protocol below to identify and add informative outliers to the training set.

Issue 2: Unphysical Forces and Structural Instability

- Symptoms: Atoms "blowing up" during MD, sudden energy spikes, bond breaking in stable molecules.

- Diagnosis: Inaccuracy in force predictions or lack of stability guarantees (e.g., missing long-range interactions).

- Resolution: Re-evaluate on curated stability benchmarks. Apply a post-processing sanity check using the protocol for stability validation.

Issue 3: Inconsistent Performance Across Property Types

- Symptoms: Good energy accuracy but poor stress or vibrational frequency prediction.

- Diagnosis: The MLIP loss function may be improperly weighted, or the model lacks relevant physical constraints.

- Resolution: Adjust loss function weights and verify using the multi-property benchmark table below.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the primary quantitative metrics to benchmark MLIP robustness? A1: Core metrics should be evaluated across three pillars, as summarized in the table below.

Q2: My MLIP fails catastrophically when simulating a phase transition not present in the training data. How can I improve this? A2: This is a transferability challenge. You need to expand the training configuration space. Use iterative basin hopping or meta-dynamics to sample novel intermediates and include them in training. The workflow for this is provided in Diagram 1.

Q3: How can I diagnose if my MD simulation crash is due to the MLIP or the simulation setup? A3: Follow this diagnostic protocol:

- Run a reference ab initio MD for a few femtoseconds on the initial configuration.

- Run MLIP MD from the same starting point.

- Compare energies and forces at each step. A divergence >20% within 10 steps strongly points to an MLIP instability issue.

Q4: Are there standard datasets to test MLIP transferability for biomolecular systems? A4: Yes. Key resources include:

- rMD17: Enhanced version of MD17 with more stable trajectories.

- SPICE: A diverse dataset of drug-like molecules and peptides.

- BAMBOO: Benchmarks for amorphous and biological systems.

Quantitative Benchmark Data

Table 1: Core Robustness Metrics for MLIP Evaluation

| Pillar | Metric | Target Value (Solid-State Systems) | Target Value (Molecules) | Evaluation Dataset Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | Energy MAE | < 5 meV/atom | < 10 meV/atom | QM9, Materials Project |

| Accuracy | Force MAE | < 100 meV/Å | < 50 meV/Å | rMD17, ANI-1x |

| Stability | Stable MD Steps | > 1 ns without crash | > 100 ps without crash | Crystal melting, protein folding |

| Transferability | Out-of-Domain Error Increase | < 300% of in-domain error | < 200% of in-domain error | Novel catalyst surfaces, folded protein states |

Table 2: Comparison of MLIP Architectures on Robustness Pillars

| MLIP Type | Accuracy | Stability in Long MD | Transferability | Computational Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Behler-Parrinello NN | Moderate | High (with careful training) | Low | Low |

| Message-Passing NN | High | Variable (can be unstable) | Moderate | Moderate-High |

| Equivariant Transformer | Very High | Moderate | High | High |

| Linear ACE/Potential | High | Very High | Moderate | Low |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Active Learning Loop for Improving Transferability

- Initial Training: Train MLIP on baseline dataset (e.g., SPICE).

- Exploration MD: Run extended MD simulations on target system(s) (e.g., protein-ligand complex).

- Uncertainty Quantification: Use committee models or dropout to calculate uncertainty (std. dev.) in energy/force predictions per atom.

- Structure Selection: Extract all configurations where uncertainty exceeds threshold (e.g., force std. dev. > 150 meV/Å).

- Ab Initio Labeling: Perform DFT calculations on selected configurations.

- Retraining: Add new data to training set and retrain model. Iterate steps 2-6 until uncertainty is below target.

Protocol 2: Stability Validation for MD Simulations

- Short-Term Test: Run 10 ps NVT MD at 300K and 1000K. Monitor max atomic force.

- Energy Conservation Test: Run 20 ps NVE MD from equilibrated system. Calculate energy drift:

drift = (E_final - E_initial) / std(E_series). A robust MLIP should have|drift| < 5. - Phase Boundary Test: For materials, simulate gradual heating from 300K to melting point. Compare predicted melting point to reference (error < 10% is good).

Visualizations

Active Learning Workflow for MLIP Robustness

Three Pillars of MLIP Robustness Defined

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Solutions

Table 3: Essential Software Tools for MLIP Robustness Research

| Tool Name | Category | Primary Function in Robustness Research |

|---|---|---|

| ASE (Atomic Simulation Environment) | Python Library | Interface for MD, calculator management, and trajectory analysis. |

| LAMMPS | MD Engine | High-performance MD simulations with MLIP plugin support (e.g., via libtorch). |

| i-PI | MD Engine | Path-integral MD for nuclear quantum effects, tests MLIP under quantum fluctuations. |

| QUICK | Uncertainty Wrapper | Adds ensemble-based uncertainty quantification to any MLIP during MD. |

| FLARE | MLIP Code | Features on-the-fly active learning and Bayesian uncertainty during MD. |

| VASP/Quantum ESPRESSO | Ab Initio Code | Generate reference training data and validate MLIP predictions on critical configurations. |

Table 4: Critical Datasets for Benchmarking

| Dataset | System Type | Relevance to Robustness Pillar |

|---|---|---|

| QM9 | Small organic molecules | Accuracy baseline for energies and forces. |

| rMD17 | Molecular dynamics trajectories | Stability test via MD error propagation. |

| SPICE | Drug-like molecules & peptides | Transferability for biophysical simulations. |

| OC20/OC22 | Catalytic surfaces & reactions | Transferability to complex solid-liquid interfaces. |

| BAMBOO | Amorphous materials, biomolecules | Stability & Transferability for disordered systems. |

Why Traditional Force Fields Fail Where MLIPs Promise to Succeed

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Molecular Dynamics Simulations

FAQ: Understanding the Core Limitations and Promises

Q1: What are the fundamental accuracy limitations of Traditional Force Fields (FFs) that users should be aware of in their simulations?

A: Traditional FFs rely on fixed functional forms with parameters derived from limited quantum mechanical (QM) data and experimental measurements. Their core failures stem from:

- Fixed Functional Forms: Cannot capture complex, context-dependent quantum mechanical effects like bond formation/breaking, charge transfer, or polarizability.

- Limited Transferability: Parameters optimized for specific molecules or conditions (e.g., aqueous solution) perform poorly when applied to different chemical environments or phases (e.g., interfaces, non-aqueous solvents).

- Systematic Errors: Known inaccuracies in describing van der Waals interactions, torsional profiles, and non-covalent interactions like π-π stacking.

Q2: My MLIP simulation crashed or produced unphysical geometries. What are the primary troubleshooting steps?

A: Follow this systematic guide:

- Check Training Domain: Verify that the atomic species and local chemical environments in your simulation system fall within the configuration space covered by the MLIP's training data. Extrapolation is a primary failure mode.

- Review Input Configuration: Ensure your starting structure does not have unrealistic steric clashes, which can force the model into an undefined region.

- Examine Model Logs: Look for warnings about high extrapolation indicators (e.g., high "local uncertainty" or "deviation" scores if the MLIP provides them).

- Validate with Short Run: Run a short energy minimization and a few MD steps while monitoring energy and force components for sudden divergences.

- Consult Documentation: Refer to the specific MLIP's documentation for known limitations (e.g., maximum Z for elements, exclusion of radical states).

Q3: How do I diagnose if my simulation results are suffering from "alchemical hallucinations" or extrapolation errors from an MLIP?

A: Implement these validation protocols:

- Ensemble Uncertainty: If supported by the MLIP, run an ensemble of models. Large variance in forces or energies for specific configurations indicates low confidence/potential hallucination.

- QM Single-Point Validation: Select representative snapshots (especially those with unusual geometries or high uncertainty) and perform QM single-point energy calculations. Compare energies and atomic forces.

- Property Monitoring: Track key properties (e.g., radial distribution functions, coordination numbers, torsion angles) against available experimental or high-level QM reference data. Sudden, unphysical shifts are red flags.

Q4: What are the critical steps for preparing a robust training dataset when developing/retraining an MLIP for my specific system?

A: A robust dataset is foundational. Follow this methodology:

Active Learning Loop:

- Initial Dataset: Start with diverse QM calculations (DFT) of molecular clusters, fragments, and potential reaction intermediates.

- Exploration: Run exploratory MLIP-driven MD simulations (e.g., at elevated temperatures).

- Selection: Use uncertainty/error indicators to select new configurations where the model is uncertain.

- Iteration: Compute QM energies/forces for these new configurations and add them to the training set. Retrain the model. Repeat until uncertainty is low across sampled configurations.

Data Quality: Ensure QM calculations use a consistent, sufficiently high level of theory (e.g., DFT functional, basis set, dispersion correction) and are converged.

Quantitative Comparison: Traditional FF vs. MLIP Performance

Table 1: Benchmark Accuracy on Standard Test Sets (Generalization)

| Property / Test System | Traditional FF (e.g., GAFF2) | MLIP (e.g., ANI, MACE) | High-Quality Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| RMSD in Forces (eV/Å) on diverse molecules | 1.0 - 3.0 | 0.1 - 0.3 | QM (DFT) |

| Torsional Profile Error (kcal/mol) | 1.0 - 5.0 | < 1.0 | QM (CCSD(T)) |

| Liquid Water Density (g/cm³) at 300K | ~0.99 (requires tuning) | 0.997 ± 0.001 | Experiment |

| Organic Molecule Crystal Cell Error | 5-15% | 1-3% | Experiment |

Table 2: Computational Cost Scaling (Typical System: ~1000 Atoms)

| Method | Energy/Force Call Time | Hardware Requirement for Nanosecond MD |

|---|---|---|

| High-Level QM (e.g., DFT) | Hours to Days | HPC Cluster (Impractical) |

| Traditional FF (e.g., AMBER) | < 1 second | Single GPU / Multi-core CPU |

| MLIP (e.g., equivariant model) | ~0.1 - 10 seconds | Single to Multi-GPU |

Experimental Protocols for MLIP Robustness Research

Protocol 1: Active Learning Workflow for Developing a Robust MLIP

Objective: To iteratively generate a training dataset and MLIP model that reliably covers the free energy surface of a drug-like molecule in solvated conditions.

Materials:

- Initial Structures: 3D conformers of the target molecule.

- QM Software: ORCA, Gaussian, or CP2K for reference calculations.

- MLIP Framework: AMPTorch, MACE, or NequIP codebase.

- Sampling Engine: LAMMPS or ASE with MLIP plugin.

- Computing Resources: GPU nodes for MLIP training, CPU/GPU clusters for sampling.

Methodology:

- Step 1 - Initial QM Dataset Generation:

- Perform conformational search on the target molecule using RDKit or CREST.

- Run single-point QM (DFT) calculations on 100-500 diverse conformers and small solute-solvent clusters.

- Extract energies, forces, and atomic coordinates.

- Step 2 - Initial Model Training:

- Split initial data 80/10/10 (train/validation/test).

- Train an MLIP model (e.g., 3-layer MACE network) until validation loss converges.

- Step 3 - Uncertainty-Guided Sampling:

- Run multiple short (10-50 ps) MD simulations of the solvated system using the trained MLIP at various temperatures.

- Use the model's intrinsic uncertainty estimator (or ensemble variance) to flag 50-100 configurations with high predicted error.

- Step 4 - QM Recálculo and Retraining:

- Perform QM calculations on the flagged high-uncertainty configurations.

- Add these new data points to the training set.

- Retrain the MLIP model from scratch or using transfer learning.

- Step 5 - Convergence Test:

- Monitor the reduction in the maximum uncertainty of configurations sampled from new MD runs.

- Repeat Steps 3-4 until no configurations exceed a pre-defined uncertainty threshold.

- Step 6 - Production Simulation & Validation:

- Run µs-scale MLIP-MD simulation.

- Validate against long-timescale experimental data (e.g., NMR J-couplings, scattering profiles) if available.

Diagram: Active Learning Workflow for MLIP Development

Protocol 2: Benchmarking MLIP Robustness Against Known Failure Modes of FFs

Objective: To systematically test an MLIP's performance on systems where traditional FFs are known to fail.

Test Systems:

- Charge Transfer: Zundel cation (H₅O₂⁺) dynamics.

- Aromatic Interactions: Stacking vs. T-shaped configuration of benzene dimer free energy profile.

- Reactive Pathway: A simple SN2 reaction (e.g., Cl⁻ + CH₃Cl → ClCH₃ + Cl⁻).

Methodology:

- Reference Data Generation: Perform high-level QM (e.g., CCSD(T)/DFT) calculations or meta-dynamics to obtain the "ground truth" potential energy surface (PES) or free energy profile for each test.

- MLIP Evaluation: Use the trained MLIP to compute the same PES or run enhanced sampling simulations (e.g., umbrella sampling) to obtain the free energy profile.

- Error Quantification: Calculate RMS errors in energies, forces, and reaction/activation barriers. Compare directly to errors from standard FFs (e.g., GAFF, OPLS) run through identical protocols.

Diagram: MLIP Robustness Benchmarking Protocol

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Software and Materials for MLIP Research

| Item Name (Category) | Function / Purpose | Example Tools / Libraries |

|---|---|---|

| QM Reference Calculator | Generates the "ground truth" energy and force data for training and validation. | ORCA, Gaussian, CP2K, VASP, PSI4 |

| MLIP Architecture Code | Provides the machine learning model framework for representing the PES. | MACE, NequIP, AMPTorch, SchnetPack, Allegro |

| MD Integration Engine | Molecular dynamics software modified to accept MLIPs for calculating forces. | LAMMPS (with ML-IAP), ASE, OpenMM, i-PI |

| Active Learning Manager | Automates the sampling-selection-retraining loop for robust dataset generation. | FLARE, ALF, AmpTorch-AL |

| Uncertainty Quantifier | Estimates the model's confidence on a given atomic configuration, crucial for detecting extrapolation. | Ensemble methods, Dropout, Evidential Deep Learning |

| Enhanced Sampling Suite | Accelerates the exploration of free energy landscapes and rare events in MLIP-MD. | PLUMED, SSAGES, Colvars |

| Data Curation Toolkit | Processes, cleans, and formats quantum chemistry data into ML-ready datasets. | ASE, MDAnalysis, Pymatgen, custom Python scripts |

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Q1: During MD simulation with a NequIP model, my energy explodes to NaN after a few steps. What could be the cause? A: This is typically an out-of-distribution (OOD) failure. NequIP's strict body-ordered equivariance can fail silently when the simulation samples atomic configurations far from the training data (e.g., broken bonds, extreme angles). First, verify your training data covers the relevant phase space. Implement a robust inference-time check using the model's epistemic uncertainty (if calibrated) or a simple descriptor distance check. Restart the simulation from a stable frame with a smaller timestep.

Q2: My MACE model shows excellent accuracy on energy but poor force accuracy, affecting MD stability. How can I diagnose this?

A: Poor force accuracy often stems from inconsistencies in the training dataset or the numerical differentiation used to generate forces. Use the integrated gradient testing in the MACE repository to check for force-noise issues. Ensure your reference data (e.g., from DFT) uses consistent convergence parameters (k-points, cutoffs). Retrain with an increased force weight in the loss function (e.g., energy_weight=0.01, forces_weight=0.99).

Q3: Allegro's inference is fast, but training is slow and memory-intensive on my multi-GPU node. What optimization strategies exist?

A: Allegro's strict separation of interaction layers from chemical species allows for optimization. Use the --gradient-reduction flag in the Allegro trainer for improved multi-GPU scaling. Reduce the max_ell for the spherical harmonics if your system is largely isotropic. Consider pruning the radial basis set (num_basis_functions) as a first step to lower memory, as it has a quadratic impact on certain operations.

Q4: How do I choose the correct r_max cutoff and radial basis for my organic molecule dataset across these architectures?

A: A general guideline is to set r_max just beyond the longest non-bonded interaction critical to your property of interest (e.g., ~5.0 Å for organic systems). Use a consistent basis for fair comparison. The Bessel basis with a polynomial envelope is robust.

Table 1: Key Hyperparameter Comparison & Troubleshooting Focus

| Architecture | Key Equivariance Principle | Common Training Issue | Primary MD Failure Mode | Recommended r_max for Organics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NequIP | Irreducible representations (e3nn) | Slow convergence with high body order. | Silent OOD failures; energy NaN. | 4.5 - 5.0 Å |

| MACE | Higher-order body-ordered tensors | High GPU memory for high L_max. |

Force inaccuracies from noisy data. | 5.0 Å |

| Allegro | Separable equivariance (tensor product) | Memory overhead in early training steps. | Less frequent, but check radial basis. | 5.0 Å |

Experimental Protocol: Benchmarking MLIP Robustness for MD This protocol frames the evaluation within a thesis on MLIP robustness for long-timescale molecular dynamics.

- Dataset Curation: Select a diverse benchmark set (e.g., SPICE, rMD17). Partition into training/validation/test splits. Create a separate "challenge" set containing high-energy conformations, transition states, or rare intermediates.

- Model Training: Train NequIP, MACE, and Allegro models using a consistent radial cutoff (

r_max=5.0) and Bessel radial basis (num_basis_functions=8). Use the same training/validation splits. Optimize other architecture-specific hyperparameters (e.g.,l_max,correlation) via validation error. - Static Benchmarking: Calculate standard metrics (energy and force MAE, RMSE) on the held-out test set. Record computational cost (FLOPs, memory) for a single-point calculation.

- Dynamic Robustness Test: Initialize 10 independent MD simulations (300K, NVT) for a target molecule (e.g., aspirin) from different conformers. Run each simulation for 10 ns using each MLIP. Monitor for instability events (energy NaN, unreasonable bond breaking).

- Analysis: Calculate the Mean First Passage Time to instability or the fraction of stable simulations at 10 ns. Correlate instability events with epistemic uncertainty metrics or local-structure descriptors to identify failure triggers.

Diagram 1: MLIP Robustness Testing Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

| Item | Function in MLIP Research |

|---|---|

| Reference Ab-Initio Data (e.g., SPICE, ANI, rMD17) | Ground-truth dataset for training and benchmarking model accuracy. |

| ASE (Atomic Simulation Environment) | Python library for setting up, running, and analyzing calculations; interfaces with MLIPs. |

| LAMMPS / OpenMM | High-performance MD engines with plugins (e.g., lammps-mace) for running simulations with MLIPs. |

| Equivariant Library (e3nn) | Provides the mathematical framework for building equivariant neural networks (core to NequIP). |

| Weights & Biases (W&B) / MLflow | Experiment tracking tools to log training hyperparameters, losses, and validation metrics. |

| CHELSA | Active learning tool for generating challenging configurations and improving dataset diversity. |

Troubleshooting Guide & FAQ

Q1: In my MLIP-driven molecular dynamics (MD) simulation, the potential energy surface (PES) becomes unstable when simulating a covalent inhibitor binding to a kinase mutant not present in the training set. What is the likely cause and how can I diagnose it?

A: This is a classic out-of-distribution (OOD) problem. The ML Interatomic Potential (MLIP) was likely trained on data that did not adequately represent the specific protein-ligand chemical space or the mutation's conformational impact.

- Diagnostic Protocol:

- OOD Detection: Compute the Mahalanobis distance or use a dedicated OOD detector (like a simple classifier trained on in-distribution vs. random negatives) for the new system's atomic environments against the training data distribution.

- Local Stress Test: Run a short, constrained simulation of just the binding pocket with the mutant residue and ligand. Monitor forces and per-atom energy contributions for sudden, unphysical spikes.

- Reference Calculation: Perform a single-point energy calculation for a few extracted frames from the failing simulation using a higher-level theory (e.g., DFT for the active site, semi-empirical QM for the ligand) to quantify the MLIP's error.

Q2: My dataset for MLIP training is diverse (proteins, solvents, ligands) but simulations show poor generalization to unseen ionic strength conditions. Could data quality be an issue despite high diversity?

A: Yes. Diversity without fidelity to physical laws leads to robust but inaccurate models. Poor handling of long-range electrostatic interactions under varying ionic strengths is a common failure mode.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Quality Audit: Calculate the error distribution (MAE, RMSE) of your MLIP's predictions on a hold-out validation set, stratified by system type (e.g., protein vs. solvent box).

- Physics-Based Filtering: Apply a filter to your training data to remove configurations where the reference DFT or force field calculation may have convergence issues. Ensure electronegativity equilibrium is physically plausible.

- Targeted Augmentation: Generate a small, high-quality dataset of simple electrolyte solutions at various ionic concentrations using robust ab initio MD. Retrain the MLIP with this data added, potentially using a weighted loss function to emphasize these critical examples.

Q3: How can I systematically assess whether my training data has sufficient coverage for a drug discovery project targeting multiple protein conformations?

A: Implement a coverage metric based on a learned latent space or simple descriptors.

- Experimental Protocol for Data Coverage Assessment:

- Descriptor Calculation: For every frame in your training database and your target simulation system, compute a set of atomic environment descriptors (e.g., Smooth Overlap of Atomic Positions (SOAP), ACSF).

- Dimensionality Reduction: Use Principal Component Analysis (PCA) or UMAP to project these high-dimensional descriptors into a 2D/3D space.

- Density Calculation: Plot the kernel density estimate (KDE) of your training data points. Superimpose the projected points from your target simulation (e.g., of a new protein conformation).

- Metric: Define a coverage threshold (e.g., 95% density contour of training data). If a significant portion (>5%) of target points fall outside this contour, your data is likely insufficient for robust simulation.

Table 1: Common MLIP Error Metrics & Target Benchmarks for Robust MD

| Metric | Definition | Target for Drug Discovery MD |

|---|---|---|

| Energy MAE | Mean Absolute Error in total energy per atom | < 1-2 meV/atom |

| Force MAE | Mean Absolute Error in force components | < 100 meV/Å |

| Force RMSE | Root Mean Square Error in forces | < 150 meV/Å |

| Stress RMSE | Error in virial stress components | < 0.1 GPa |

| Inference Speed | Simulation steps per second | > 1 ns/day for >50k atoms |

Table 2: Impact of Training Data Composition on Simulation Stability

| Data Strategy | Conformational Diversity | Chemical Diversity | OOD Failure Rate (in benchmark) | Relative Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Homogeneous (One Protein) | Low | Low | High | Low |

| Curated Diverse Set | Medium-High | Medium | Medium | Medium |

| Maximally Diverse (All Public Data) | High | High | Low (General) but High (Specific) | High |

| Targeted Active Learning | High for Region of Interest | Adaptive | Low for Target | Variable |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Generating High-Quality Training Data via Active Learning for an MLIP

- Initialization: Start with a small seed dataset of representative molecular configurations (e.g., protein folded/unfolded, ligand bound/unbound, solvent boxes).

- Query by Committee: Train an ensemble of 3-5 MLIPs on the current dataset.

- Exploration MD: Run short, exploratory MD simulations with the committee MLIPs on the target system(s).

- Uncertainty Sampling: For each new configuration sampled, calculate the predictive variance (disagreement) among the committee models for energy and forces.

- Selection: Select the N configurations with the highest committee variance.

- Ab Initio Calculation: Perform accurate ab initio (DFT) single-point energy and force calculations for the selected configurations.

- Augmentation: Add these new {configuration, energy, forces} pairs to the training database.

- Iteration: Repeat steps 2-7 until the committee variance falls below a predefined threshold across exploratory simulations.

Protocol 2: Diagnosing an OOD Failure in a Running Simulation

- Monitor Real-time Signals: Track total energy, maximum force on any atom, and local atomic energy outliers.

- Trigger: If a metric exceeds a threshold (e.g., max force > 10 eV/Å), save the immediate simulation trajectory (e.g., 10 frames before and after the event).

- Environment Extraction: From the problematic frame(s), extract all unique atomic environments (within a cutoff radius).

- Similarity Search: Compare each extracted environment against the MLIP's training database using a SOAP kernel or similar metric.

- Flag: Mark environments with a maximum similarity score below a pre-calibrated threshold (e.g., 0.7) as OOD.

- Report: Log the percentage of OOD environments and their spatial location within the simulated system (e.g., specific residue, ligand moiety).

Visualizations

Title: OOD Detection in MLIP Simulation Workflow

Title: High-Quality Diverse Training Data Pipeline

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Tools for MLIP Robustness Research

| Item | Function in Research | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Ab Initio Software | Generate high-quality reference data for training and validation. | CP2K, VASP, Gaussian. Use with hybrid functionals and dispersion correction. |

| MLIP Framework | Provides architecture and training utilities for the interatomic potential. | DeePMD-kit, MACE, Allegro, NequIP. Choose based on performance/accuracy trade-off. |

| Active Learning Platform | Automates the iterative data acquisition and model improvement cycle. | FLARE, ASE with custom scripts, DP-GEN. |

| QM/MM Partitioning Tool | Enables focused high-accuracy calculation on active site while treating bulk with MLIP/FF. | ChemShell, QMMM in CP2K. Critical for efficient ligand binding studies. |

| Trajectory Analysis Suite | Analyzes simulation outputs for stability, energy drift, and OOD signals. | MDTraj, MDAnalysis, VMD with custom Tcl scripts for per-atom energy monitoring. |

| Reference Force Field | Serves as baseline and for generating initial conformational diversity. | CHARMM36, AMBER FF19SB. Use for long, stable pre-sampling before ab initio labeling. |

| High-Performance Compute (HPC) Cluster | Runs large-scale ab initio calculations and production MD simulations. | GPU nodes are essential for training; CPU clusters for reference DFT. |

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting for MLIPs in Molecular Dynamics

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Simulation Instability and Unphysical Bond Lengths

- Observed Symptom: Atoms collapse into each other or bonds stretch to unrealistic lengths during an MD run, leading to a crash.

- Root Cause (Likely): Extrapolation Error. The Machine Learning Interatomic Potential (MLIP) is making predictions for atomic configurations far outside its trained domain (e.g., unusual bond angles, element ratios, or local densities not present in the training set).

- Diagnostic Steps:

- Run a short simulation and log the model's predicted uncertainty or the

max_forceon any atom at each step. - Calculate the local atomic environment descriptors (e.g., SOAP, ACE) for frames where instability begins and compare their distribution to your training data.

- Run a short simulation and log the model's predicted uncertainty or the

- Resolution Protocol:

- Immediate Stop: Halt the simulation.

- Identify Out-of-Distribution (OOD) Configuration: Use the diagnostic logs to pinpoint the first frame where uncertainty spiked.

- Active Learning Loop:

- Extract the high-uncertainty configuration.

- Perform an accurate ab initio (DFT) calculation on this configuration.

- Add this new data to your training set.

- Retrain the MLIP with a balanced dataset (see Catastrophic Forgetting section).

Issue 2: Loss of Accuracy on Previously Known Chemical Spaces

- Observed Symptom: After retraining the MLIP on new data (e.g., for a new molecule), its performance on your original benchmark systems (e.g., bulk water) degrades significantly.

- Root Cause: Catastrophic Forgetting. The neural network has overwritten weights that were important for predicting the original chemical space when learning the new one.

- Diagnostic Steps: Maintain a fixed benchmark set (energy/force errors on diverse, held-out configurations) and test the model on it after every retraining cycle.

- Resolution Protocol:

- Implement rehearsal-based training.

- During each retraining cycle, include a strategically sampled subset of data from all previous training phases.

- Alternatively, use elastic weight consolidation (EWC) or other regularization techniques that penalize changes to weights deemed important for previous tasks.

Issue 3: Non-Conservative Forces and Drifting Total Energy

- Observed Symptom: In an NVE (microcanonical) ensemble simulation, the total energy of the system shows a clear upward or downward drift over time, instead of fluctuating around a mean.

- Root Cause: Energy Drift. The forces predicted by the MLIP are not perfectly conservative; i.e., they cannot be expressed as the negative gradient of a single, well-defined potential energy surface. This is often due to numerical instabilities or architectural limitations in the model.

- Diagnostic Steps: Run a closed-loop (cyclic) MD simulation and monitor the total energy. A non-zero net change after a cycle indicates non-conservative forces.

- Resolution Protocol:

- Ensure the model architecture is explicitly designed to enforce energy conservation (e.g., using strict energy-force consistency in training).

- Check the numerical precision of force calculations (autograd vs. finite difference).

- Increase the convergence thresholds for the ab initio calculations used to generate your training data.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: How can I proactively detect extrapolation errors before a simulation fails? A: Implement an uncertainty quantification (UQ) guardrail. Most modern MLIPs (e.g., those using ensemble, dropout, or evidential methods) can output an epistemic uncertainty estimate. Set a threshold (e.g., 150 meV/atom) and configure your MD engine to pause or trigger an ab initio callback when it is exceeded.

Q2: What is the minimum amount of old data needed to prevent catastrophic forgetting? A: There is no universal minimum. It depends on the diversity of the original chemical space. A common strategy is to use coreset selection (e.g., farthest point sampling on atomic environment descriptors) to retain a representative 5-10% of the original training data for rehearsal. Performance on your benchmark set will guide sufficiency.

Q3: Is a small energy drift in NVE simulations always a problem? A: A minimal drift (e.g., < 0.1% over 1 ns) is often acceptable numerical noise. However, a systematic, physically significant drift (> 1%) invalidates the NVE ensemble and indicates a fundamental issue with the potential. For production NVE runs, the drift should be quantified and reported.

Q4: Can I combine data from different levels of quantum mechanics (QM) theory to train my MLIP? A: This is highly discouraged as it introduces theory inconsistency, which can manifest as extrapolation errors and energy drift. Always train on forces and energies computed at the same, consistent level of theory. If you must mix, treat them as separate data domains and use advanced transfer learning techniques with caution.

Table 1: Common Benchmarks for MLIP Failure Modes

| Failure Mode | Diagnostic Metric | Warning Threshold | Critical Threshold | Typical Measurement Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Extrapolation Error | Predicted Uncertainty (Epistemic) | > 100 meV/atom | > 200 meV/atom | Ensemble Std. Dev. or Dropout Variance |

| Catastrophic Forgetting | RMSE on Held-Out Benchmark | Increase of > 20% from baseline | Increase of > 50% from baseline | Energy & Force Error on Fixed Configs |

| Energy Drift | Total Energy Change in NVE | > 0.5 meV/atom/ps | > 2.0 meV/atom/ps | Linear fit of E_total vs. Time over 100+ ps |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Active Learning Loop for Mitigating Extrapolation Errors

- Initialization: Start with a seed MLIP trained on a diverse but limited ab initio dataset.

- Exploratory Simulation: Run an MD simulation of the target system at the desired thermodynamic conditions.

- Configuration Sampling & Query: At regular intervals (e.g., every 10 fs), compute the MLIP's uncertainty for the atomic configuration. Use a query strategy (e.g., uncertainty maximization) to select candidate configurations where the uncertainty exceeds the threshold (e.g., 150 meV/atom).

- Ab Initio Callback: Perform a high-fidelity DFT calculation on the selected candidate configuration(s).

- Data Augmentation: Add the new (configuration, energy, forces) data pair to the training database.

- Model Retraining: Retrain the MLIP on the augmented dataset. Use a rehearsal buffer to retain past knowledge.

- Iteration: Repeat steps 2-6 until no configurations in a full simulation exceed the uncertainty threshold.

Protocol 2: Benchmarking for Catastrophic Forgetting

- Create Benchmarks: From your primary training data (Phase A), create a held-out test set

Benchmark_A. - Establish Baseline: Train Model v1 on Phase A data. Record its Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) on

Benchmark_A. - Introduce New Data: Train Model v2 on new data from a different chemical space (Phase B).

- Test for Forgetting: Evaluate Model v2 on

Benchmark_A. A significant increase in RMSE indicates forgetting. - Apply Mitigation: Train Model v3 on Phase B data plus a coreset (~10%) sampled from Phase A data.

- Evaluation: Evaluate Model v3 on

Benchmark_A. The RMSE should be close to the Model v1 baseline.

Visualizations

Diagram 1: Active Learning Workflow for MLIPs

Diagram 2: MLIP Failure Mode Relationships

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Tools & Materials for Robust MLIP Development

| Item | Function in Experiments | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| High-Quality QM Dataset | Foundational training data. Must be consistent and cover relevant configurational space. | QM9, ANI-1x, OC20, or custom DFT (e.g., CP2K, VASP) calculations. |

| MLIP Software Framework | Provides architecture, training, and MD integration. | AMPTorch, MACE, NequIP, Allegro, DeepMD-kit. |

| Active Learning Manager | Orchestrates uncertainty querying and ab initio callbacks. | FLARE, Chemiscope, custom scripts using ASE. |

| Rehearsal Buffer / Coreset | Stores representative past data to combat catastrophic forgetting. | Implemented via PyTorch Dataset or FAISS for similarity search. |

| Uncertainty Quantification (UQ) Module | Estimates model uncertainty to flag extrapolation. | Built-in ensemble variance, dropout, or SGLD methods. |

| MD Engine with MLIP Support | Runs the production simulations. | LAMMPS, GROMACS, OpenMM, i-PI. |

| Benchmarking Suite | Tracks performance over time to detect forgetting and regressions. | Custom scripts evaluating energy/force RMSE, radial distribution functions, etc. |

A Practical Pipeline: Implementing Robust MLIPs for Biomolecular Systems

Troubleshooting Guide & FAQs

FAQ 1: Why do my MLIPs fail to generalize to solvent-solute interactions despite training on QM/MM data?

Answer: This is often due to a mismatch in the sampling of configurational space. QM/MM simulations typically focus on a reactive center, leading to an underrepresentation of bulk solvent configurations and long-range interactions in your training set. The MLIP learns the electrostatic and polarization effects present in the small QM region but fails when presented with a fully solvated system where the MM region's empirical treatment differs from the learned QM behavior.

Solution Protocol: Implement a hybrid sampling strategy.

- Core Reaction Sampling: Run your primary QM/MM simulation (e.g., using CP2K, Amber/TeraChem).

- Bulk Solvent Augmentation: Run a short, pure MM molecular dynamics (MD) simulation of the solvent alone.

- Cluster Extraction: Use a tool like

MDTrajto extract diverse solvent cluster snapshots (dimers, trimers, tetrahedrals) from the MM simulation. - Single-Point QM Calculations: Perform high-level ab initio (e.g., DFT with a dispersion correction) single-point energy and force calculations on these clusters.

- Dataset Merging: Combine the QM/MM trajectory data and the ab initio solvent cluster data into a unified training set. Ensure consistent energy offsets between the datasets.

FAQ 2: How should I handle energy and force disparities between ab initio and QM/MM data when merging them into one training set?

Answer: Direct merging causes catastrophic learning failure because the absolute energies from different methods (and system sizes) are on incompatible scales. The MLIP cannot reconcile the different reference states.

Solution Protocol: Data Shifting and Normalization.

- Per-Dataset Shift: Apply a global scalar shift to the energies of each dataset so that their mean energy aligns. Do not shift forces.

- Reference Energy: For each dataset, calculate the mean potential energy:

E_shifted = E_original - mean(E_original). - Consistent Units: Verify all data uses identical units (commonly eV for energy, eV/Å for forces).

- Training Weighting: Assign higher loss function weights to forces (e.g., 1000:1 force-to-energy weight) as they are vector quantities and more critical for MD stability. Use a normalized error metric like RMSE.

Table 1: Recommended Data Preprocessing Steps for a Combined Dataset

| Step | Action | Tool Example | Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Format Standardization | Convert all outputs (.out, .log, .xyz) to a common format (e.g., ASE .db, .extxyz). | ASE, dpdata |

Enables unified processing. |

| 2. Deduplication | Remove near-identical frames using a geometric hash (RMSD < 0.05 Å) or energy/force hash. | QUICK (Quantum Chemistry Integrity Checker) |

Prevents dataset bias and overfitting. |

| 3. Statistical Filtering | Remove high-energy outliers (beyond 4 standard deviations from mean) and frames with implausibly large force components. | Custom Python/Pandas script | Removes unphysical configurations from QM failures. |

| 4. Splitting Strategy | Split data by system composition/cluster size, not randomly. Use 80/10/10 for train/validation/test. | scikit-learn GroupShuffleSplit |

Ensures test set evaluates extrapolation to new sizes. |

Experimental Protocol: Building a Robust Training Dataset for Solvated Enzyme MLIP

Objective: Generate a training dataset for an MLIP to simulate a solvated enzyme with a reactive active site.

Methodology:

- QM/MM Simulation (Source of Reactive Data):

- System Setup: Model the enzyme with a substrate in the active site using CHARMM36/AMBER force fields. Define the QM region (30-100 atoms) encompassing the substrate and key catalytic residues.

- Calculation: Run Born-Oppenheimer MD or metadynamics using CP2K (PBE-D3/def2-SVP for QM; MM field for surroundings). Save snapshots every 5-10 fs.

- Output: Extract coordinates, energies, and forces for the entire system (QM+MM). The MM forces are empirical but provide essential context.

Ab Initio Clustering (Source of Generalizable Solvation Data):

- Configuration Sampling: From a classical MD simulation of pure water, sample 5000 unique solvent clusters (e.g., (H₂O)₂ to (H₂O)₁₀).

- High-Fidelity Calculation: Perform single-point DFT calculations (e.g., PBE0-D3(BJ)/def2-TZVP) using ORCA or PySCF on each cluster to get accurate energies and forces.

Curation & Preprocessing Pipeline:

- Step A: Apply Protocol from FAQ 2 to shift energies within the QM/MM dataset and the ab initio cluster dataset separately.

- Step B: Merge the shifted datasets.

- Step C: Apply the filtering and splitting steps outlined in Table 1.

Diagram: Training Data Curation and Preprocessing Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Software Tools for Data Curation

| Tool Name | Category | Primary Function in Preprocessing |

|---|---|---|

| Atomic Simulation Environment (ASE) | Library/IO | Universal converter for quantum chemistry files; read/write .xyz, .db, and calculate descriptors. |

| dpdata | Library/IO | Specialized library for parsing and converting output from DP, VASP, CP2K, Gaussian, etc., to a uniform format. |

| MDTraj | Analysis | Processes MD trajectories; essential for extracting solvent clusters and computing RMSD for deduplication. |

| QUICK | Quality Control | Quantum chemistry data integrity checker; identifies and removes corrupted or duplicate computations. |

| PySCF | Ab Initio Calculation | Python-based quantum chemistry framework; ideal for scripting high-throughput single-point calculations on clusters. |

| Pandas & NumPy | Data Manipulation | Core libraries for data cleaning, statistical filtering, and managing large datasets in DataFrames/arrays. |

Troubleshooting Guide & FAQs for MLIP Robustness in Molecular Dynamics Simulations

FAQ 1: How do I diagnose if my Active Learning loop is failing to explore relevant chemical spaces?

A: Monitor the candidate pool diversity and model uncertainty metrics. A common failure mode is the "rich-get-richer" scenario where the sampler only selects configurations from a narrow energy basin. Implement a diversity metric (e.g., based on a low-dimensional descriptor like SOAP or atomic fingerprints) and track it alongside the model's uncertainty (e.g., standard deviation of a committee of models). If diversity plateaus while uncertainty remains high, your acquisition function may be too greedy.

Diagnostic Table:

Metric Healthy Trend Warning Sign Corrective Action Pool Diversity Increases steadily, then fluctuates. Plateaus early or decreases. Increase weight of diversity-promoting term in acquisition function. Model Uncertainty Decreases globally over cycles. Spikes in new regions; high variance in known regions. Increase initial random sampling; check feature representation. Energy Range Sampled Expands over time. Remains confined to a narrow window. Manually inject high-energy or rare event configurations into the pool.

FAQ 2: My MLIP training error is low, but simulation properties (e.g., diffusion coefficient, phase transition point) are physically inaccurate. What steps should I take?

A: This indicates a failure in the generalization robustness of the MLIP, likely due to inadequate sampling of key physical phenomena during Active Learning. Your training set lacks configurations critical for the target property.

Protocol: Targeted Sampling for Property Robustness

- Identify Property-Sensitive Degrees of Freedom: Determine which collective variables (CVs) govern the property (e.g., coordination number for diffusion, volume for phase transitions).

- Seed with Enhanced Sampling: Run a short, classical enhanced sampling simulation (e.g., metadynamics, umbrella sampling) using a baseline force field to map the free energy surface along the CVs.

- Extract Critical Configurations: From the enhanced sampling trajectory, extract configurations from high-energy transition states, metastable states, and phase boundaries.

- Inject into AL Pool: Add these configurations to your Active Learning candidate pool. Ensure your acquisition function can prioritize them (e.g., by biasing selection based on CV values or estimated energy).

- Validate with A Posteriori Tests: Always run a full molecular dynamics simulation with the final MLIP and compare the emergent property to benchmark data or experimental values.

FAQ 3: What are the best practices for structuring the initial training set to ensure robust Active Learning from the start?

A: The initial set must be both diverse and representative of basic chemical environments. Avoid random sampling alone.

Protocol: Building a Foundational Training Set

- Generate Configurations: From a small unit cell, generate:

- Perturbed Structures: Apply random atomic displacements (e.g., ±0.1 Å).

- Strained Cells: Apply small tensile and shear strains.

- Molecular Dimers/Trimers: For systems with non-covalent interactions, sample multiple distances and orientations.

- Compute Reference Data: Use DFT (or higher-level theory) to compute energies, forces, and stresses for these configurations.

- Incorporate Known Extremes: Manually include high-symmetry configurations, known transition states from literature, and isolated atom/molecule references for energy anchoring.

- Train Initial Model: Train the first MLIP iteration on this set. Its performance on a separate, small validation set of similar complexity should be good before starting the Active Learning loop.

- Generate Configurations: From a small unit cell, generate:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Tool | Function in MLIP Active Learning |

|---|---|

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) Code (e.g., VASP, Quantum ESPRESSO) | Provides the high-fidelity reference energy, force, and stress labels for training configurations. The "ground truth" source. |

| MLIP Framework (e.g., MACE, NequIP, Allegro) | Software implementing the machine-learned interatomic potential architecture. Enables fast evaluation of energies/forces. |

| Active Learning Manager (e.g., FLARE, ASE, custom scripts) | Orchestrates the loop: selects candidates from the pool, launches DFT calculations, manages the training dataset, and triggers model retraining. |

| Molecular Dynamics Engine (e.g., LAMMPS, OpenMM) | Used to run exploratory and production simulations with the MLIP to generate candidate pools and validate properties. |

| Enhanced Sampling Suite (e.g., PLUMED) | Crucial for probing rare events and phase spaces not easily found by standard MD, generating critical configurations for the AL pool. |

Diagram: Active Learning Loop for Robust MLIPs

Diagram: Key Metrics for AL Diagnostics

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

FAQ 1: My MLIP training loss (MSE) plateaus early, but forces remain physically implausible. What's wrong?

Answer: This is a classic sign of an imbalanced loss function. The Mean Squared Error (MSE) on energies is often orders of magnitude larger than force components, causing the optimizer to ignore force accuracy. Use a composite, weighted loss function.

Protocol: Implement: L_total = w_E * MSE(E) + w_F * MSE(F) + w_ξ * Regularization. Start with w_E=1.0, w_F=100-1000 (to balance scale), and w_ξ=0.001. Monitor energy and force error components separately during training.

FAQ 2: My model overfits on small quantum chemistry datasets and fails on unseen molecular configurations. Answer: This indicates insufficient regularization and a lack of robust uncertainty quantification (UQ). Overfitting is common with flexible neural network potentials. Protocol:

- Add Regularization: Implement Dropout (rate=0.1) or L2 weight decay (λ=1e-5).

- Incorporate UQ: Use Deep Ensemble or Monte Carlo Dropout during training. Train 5-10 models with different random seeds or enable Dropout at inference.

- Use a Validation Set: Monitor loss on a held-out set of configurations; employ early stopping when validation error increases for 50 epochs.

FAQ 3: How do I know if my predicted uncertainty is calibrated and reliable for MD simulation? Answer: A well-calibrated UQ method should show high error where uncertainty is high. Perform calibration checks. Protocol: For a test set, bin predictions by their predicted uncertainty (variance). In each bin, compute the root mean square error (RMSE). Plot RMSE vs. predicted standard deviation. Data should align with the y=x line. Significant deviation indicates poor calibration, requiring adjustment of the UQ method or loss function.

FAQ 4: My MD simulation crashes or produces NaN energies when using the MLIP. Answer: This is often due to the model extrapolating into regions of chemical space not covered in training, where its predictions are uncontrolled. Protocol:

- Implement an Uncertainty Threshold: Compute the predictive variance (e.g., from your ensemble). Define a maximum allowable variance threshold (e.g., 0.05 eV²/atom).

- Create a Safety Net: During MD, if the uncertainty for any atom exceeds the threshold, halt the simulation and flag the configuration.

- Active Learning: Add these high-uncertainty configurations to your training set, recalculate DFT labels, and retrain the model.

Data Tables

Table 1: Comparison of Loss Function Components for MLIP Training

| Component | Typical Weight Range | Purpose | Impact on MD Robustness |

|---|---|---|---|

| Energy MSE (w_E) | 1.0 (reference) | Fits total potential energy | Ensures correct relative stability of isomers. |

| Force MSE (w_F) | 10 - 1000 | Fits atomic force vectors | Critical for stable dynamics; prevents atom collapse. |

| Stress MSE (w_S) | 0.1 - 10 | Fits virial stress tensor | Needed for constant-pressure (NPT) simulations. |

| L2 Regularization (λ) | 1e-6 - 1e-4 | Penalizes large network weights | Reduces overfitting, improves transferability. |

Table 2: Uncertainty Quantification Methods for Robust MD

| Method | Training Overhead | Inference Overhead | Calibration Quality | Recommended Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deep Ensemble | High (5x compute) | High (5x forward passes) | High | Production, high-fidelity simulations. |

| Monte Carlo Dropout | Low (train w/ dropout) | Medium (30-100 passes) | Medium | Rapid prototyping, large systems. |

| Evidential Deep Learning | Medium | Low (single pass) | Variable (architecture-sensitive) | When ensemble costs are prohibitive. |

| Quantile Regression | Medium | Low (single pass) | Good for tails | Focusing on extreme value prediction. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Training a Robust MLIP with Uncertainty-Aware Deep Ensemble

- Dataset Partitioning: Split your DFT dataset into Training (70%), Validation (15%), and Hold-out Test (15%) sets. Ensure no identical configurations leak across sets.

- Model Initialization: Initialize 5 identical neural network architectures (e.g., DimeNet++, NequIP, or MACE) with different random seeds.

- Training Loop (per model):

a. Use the composite loss:

L = MSE(E) + 500 * MSE(F) + 1e-5 * L2(weights). b. Use the AdamW optimizer (learning rate=1e-3, betas=(0.9, 0.999)). c. Train for up to 1000 epochs. After each epoch, evaluate on the Validation set. d. Implement early stopping: restore model weights from the epoch with the lowest validation force MAE. - Uncertainty Quantification: For a new configuration, run a forward pass through all 5 models. Compute the mean prediction (energy, forces). Compute the standard deviation across ensemble outputs as the epistemic uncertainty estimate.

- Deployment in MD: Integrate the ensemble mean forces into your MD engine (e.g., LAMMPS, ASE). Log the per-atom force uncertainty. Set a threshold (e.g., 0.5 eV/Å) to trigger simulation pauses.

Protocol: Active Learning Loop for Improving MLIP Robustness

- Initial Training: Train an MLIP (with UQ) on an initial seed dataset.

- Exploratory Simulation: Run an MD simulation (e.g., at elevated temperature) on your system of interest.

- Configuration Sampling: Periodically (every 10-100 fs) sample and store snapshots from the trajectory.

- Uncertainty Screening: Use the trained ensemble to predict energies/forces and associated uncertainty for each snapshot.

- Selection & Labeling: Select the

Nsnapshots with the highest mean atomic force uncertainty. Run DFT single-point calculations to obtain accurate labels for these configurations. - Model Update: Add the new (configuration, DFT label) pairs to the training set. Retrain the ensemble from scratch or using transfer learning.

- Iterate: Repeat steps 2-6 until the MD simulation no longer samples high-uncertainty regions, indicating robust coverage.

Visualizations

Title: Composition of the MLIP Training Loss Function

Title: Active Learning Loop for Robust MLIP Development

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Tools for MLIP Training & Robustness Research

| Item/Category | Function & Purpose | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Quantum Chemistry Code | Generates the ground-truth training data (energies, forces). | CP2K, VASP, Gaussian, ORCA. Crucial for accurate labels. |

| MLIP Framework | Provides the architecture and training utilities for the potential. | MACE, NequIP, Allegro, SchNetPack. Choose based on system size and accuracy needs. |

| Uncertainty Library | Implements UQ methods (ensembles, dropout, evidential networks). | Uncertainty Baselines, PyTorch Lightning, custom ensembles. |

| Molecular Dynamics Engine | The simulation environment that uses the MLIP for dynamics. | LAMMPS (with PLUMED), ASE, OpenMM. Must have MLIP interface. |

| Active Learning Manager | Automates the sampling, selection, and retraining loop. | FLARE, Chemiscope, custom Python scripts. |

| High-Performance Compute (HPC) | Provides resources for DFT calculations and parallel NN training. | GPU clusters (for NN) + CPU clusters (for DFT). |

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting & FAQs

FAQ 1: I get a "Potential file not found or incompatible" error when running a MLIP in LAMMPS. What are the common causes?

Answer: This error typically stems from a mismatch between the MLIP interface package, the model file format, and the LAMMPS command syntax. Ensure the following:

- Correct Plugin: You have installed a compatible MLIP interface for LAMMPS (e.g.,

mliapwith theneporpacepackage,pair_style deepmd,pair_style aenet). - Model Path: The path to the model file (e.g.,

.pt,.pb,.json,.nep) in thepair_coeffcommand is absolute or correctly relative. - Command Syntax: Your

pair_styleandpair_coeffcommands match the plugin's requirements. For example:- For DeePMD:

pair_style deepmd /path/to/graph.pbandpair_coeff * * - For NEP:

pair_style nep /path/to/model.nepandpair_coeff * *

- For DeePMD:

FAQ 2: My simulation with a MLIP in OpenMM runs but produces unphysical forces or NaN energies. How do I debug this?

Answer: This is often related to the model encountering atomic configurations or local environments far outside its training domain (extrapolation).

- Check for Extrapolation: Most MLIP interfaces (like TorchANI for OpenMM) provide extrapolation warnings or thresholds. Enable verbose logging.

- Validate Input Geometry: Ensure your initial system's coordinates, periodic boundaries, and atom types are sane and match the model's expected chemical space.

- Clip Time Step: Reduce the integration time step (e.g., to 0.1 or 0.5 fs) to prevent atoms from moving too far per step into unexplored regions.

- Use a Thermostat: Implement a gentle thermostat (e.g., Langevin with a low friction coefficient) to stabilize early dynamics.

FAQ 3: How do I ensure consistent energy and force units between different MLIP packages and MD engines?

Answer: Unit inconsistencies are a major source of silent errors. Always consult the specific documentation. Below is a reference table for common combinations.

Table 1: Default Units for Common MLIP-MD Engine Integrations

| MD Engine | MLIP Interface / Package | Default Energy Unit | Default Force Unit | Key Configuration Note |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LAMMPS | pair_style deepmd |

Real units (Kcal/mol) | Real units (Kcal/mol·Å) | DeePMD model files (*.pb) typically store data in eV & Å; LAMMPS plugin performs internal conversion. |

| LAMMPS | pair_style nep |

Metal units (eV) | Metal units (eV/Å) | NEP model files (*.nep) use eV & Å. Ensure LAMMPS units command is set to metal. |

| OpenMM | TorchANI | kJ/mol | kJ/(mol·nm) | OpenMM uses nm, while most MLIPs train on Å. The TorchANI bridge handles the Å→nm conversion. |

| OpenMM | AMPTorch (via Custom Forces) | kJ/mol | kJ/(mol·nm) | User must explicitly manage the coordinate (Å→nm) and energy (eV→kJ/mol) unit conversions in the script. |

FAQ 4: What is the recommended protocol for benchmarking a new MLIP integration before production runs?

Answer: Follow this validation workflow to assess robustness within your thesis research on MLIP reliability.

Experimental Protocol: MLIP Integration Benchmarking

- Single-Point Energy Comparison: Compute the energy and forces for a set of 100-1000 diverse configurations from a classical force field trajectory using both the standalone MLIP code and the integrated MD engine. Use a script to calculate the Mean Absolute Error (MAE).

- Equilibration Stability Test: Run a short (10-100 ps) NVT equilibration of a small, representative system (e.g., a solvated protein or molten salt). Monitor: total energy drift, temperature stability, and the absence of "explosions" or NaN values.

- Property Validation: Perform a micro-second equivalent (using a boosted dynamics method if necessary) simulation to compute a simple thermodynamic property (e.g., radial distribution function (RDF) for liquids, density of a crystal) and compare against a high-level reference or experimental data.

- Extrapolation Guard Testing: Intentionally feed highly distorted or non-physical configurations to the integrated workflow and verify that it fails gracefully (e.g., with a clear error message) rather than returning silent, unphysical results.

Title: MLIP Integration Benchmarking Workflow

FAQ 5: When using GPU-accelerated MLIPs, my performance is lower than expected. What are potential bottlenecks?

Answer: Performance issues often arise from data transfer overheads, especially for small systems.

- System Size: For systems with fewer than 10,000 atoms, the overhead of transferring data between CPU and GPU may outweigh computation benefits. Profile your runs.

- Batch Size: Some MLIP interfaces allow configuration of the batch size for neighbor list and force calculations. Adjust this for your hardware.

- Neighbor List Update Frequency: Tune the neighbor list skin distance and rebuild frequency (

neigh_modifyin LAMMPS) to minimize unnecessary GPU kernel launches.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials & Tools for MLIP Integration Research

| Item / Solution | Function / Purpose | Example (Non-Exhaustive) |

|---|---|---|

| MLIP Model File | The trained potential containing weights and descriptors. Required for inference. | graph.pb (DeePMD), model.pt (MACE), potential.nep (NEP) |

| MD Engine Interface | Plugin/library enabling the MD code to call the MLIP. | LAMMPS mliap or pair_style packages; OpenMM-TorchANI bridge; ASE calculator |

| Unit Conversion Script | Validates and converts energies/forces between code-specific units (eV, Å, kcal/mol, nm, kJ/mol). | Custom Python script using ase.units or openmm.unit constants. |

| Configuration Validator | Checks if atomic configurations stay within model's training domain. | pymatgen.analysis.eos, quippy descriptors, or MLIP's built-in warning tools. |

| Benchmark Dataset | Set of diverse structures and reference energies/forces for validation. | SPICE dataset, rMD17, or a custom dataset from your system of interest. |

| High-Performance Compute (HPC) Environment | Cluster with GPUs (NVIDIA) and compatible software drivers (CUDA, cuDNN). | NVIDIA A100/V100 GPU, CUDA >= 11.8, Slurm workload manager. |

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: My MLIP simulation shows unphysical ligand movement (e.g., "flying ligand") or rapid dissociation at the start of the run. What could be the cause? A: This is often a sign of poor initial system preparation or a "hot" starting configuration.

- Check 1: Initial Minimization. Ensure the system underwent adequate energy minimization (e.g., 5,000-10,000 steps of steepest descent) with constraints on the protein backbone and ligand before applying the MLIP. This relieves steric clashes.

- Check 2: Solvent Equilibration. Run a short (50-100 ps) classical MD simulation (NPT ensemble) using a classical force field to equilibrate the solvent and ions around the rigid protein-ligand complex before starting the MLIP-driven production run.

- Check 3: Restraints. Consider applying soft positional restraints (force constant of 1-10 kcal/mol/Ų) on protein backbone heavy atoms during the initial 10-50 ps of the MLIP simulation, gradually releasing them.

Q2: The binding free energy (ΔG) calculated via MLIP-MM/PBSA shows high variance between replicate simulations. How can I improve convergence? A: High variance typically indicates insufficient sampling of the bound state or unstable binding.

- Protocol Enhancement: Extend simulation time per replica. For robust ΔG estimates, aim for ≥100 ns per replica for mid-sized proteins, with 3-5 independent replicas initiated from different ligand velocities. Ensure the ligand remains bound (RMSD < 2-3 Å) in >80% of frames used for analysis.

- Analysis Refinement: Use the "stable binding" criterion. Discard simulation segments where the ligand RMSD exceeds a threshold (e.g., 3.5 Å) before calculating ΔG for that replica. Perform block averaging to confirm convergence.

Q3: My MLIP simulation crashes with an "out-of-distribution (OOD) error" or "confidence indicator alert." What steps should I take? A: This indicates the simulation has entered a chemical or conformational space not well-represented in the MLIP's training data.

- Immediate Action: Halt the simulation. Analyze the last 10-20 frames before the crash. Check for:

- Bond stretching/breaking: Unusually long or short bonds in the ligand or protein.

- Torsional strain: Ligand dihedrals in unphysical conformations.

- Atomic clashes.

- Mitigation Strategy: Return to the last stable configuration. Increase the frequency of saving the simulation trajectory (e.g., every 1 ps) to better capture the failure point. Consider applying mild torsional restraints to known problematic ligand dihedrals based on classical QM scans, or switch to a hybrid MLIP/classical approach for unstable regions.

Q4: How do I validate that my MLIP simulation of protein-ligand binding is physically credible? A: Employ a multi-faceted validation protocol against known experimental or higher-level theoretical data.

| Validation Metric | Target/Expected Outcome | Typical Acceptable Range |

|---|---|---|

| Ligand RMSD (Bound) | Stable binding pose. | < 2.0 - 3.0 Å from crystallographic pose. |

| Protein Backbone RMSD | Stable protein fold. | < 1.5 - 2.5 Å (dependent on protein flexibility). |

| Ligand-Protein H-Bonds | Consistent with crystal structure. | Counts within ±1-2 of crystal structure. |

| Binding Free Energy (ΔG) | Correlation with experiment. | R² > 0.5-0.6 vs. experimental IC50/Ki; MSE < 1.5 kcal/mol. |

| Interaction Fingerprint | Similarity to reference. | Tanimoto similarity > 0.7 to known active poses. |

Experimental Protocol: MLIP-Driven Binding Pose Stability Assessment

- System Preparation: Obtain PDB structure (e.g., 3ERT with OHT). Prepare with standard protonation (pH 7.4) using

pdb4amber/LEaP. Solvate in a TIP3P water box (≥12 Å padding). Add ions to neutralize and reach 0.15 M NaCl. - Classical Equilibration: Perform 5,000 steps minimization (protein+ligand restrained). Heat system from 0 to 300 K over 50 ps (NVT, restraints on protein backbone). Density equilibration for 100 ps (NPT, same restraints).

- MLIP Production: Switch to the MLIP (e.g., MACE, NequIP, CHGNet). Release all restraints. Run production simulation in the NPT ensemble (300 K, 1 bar) using a Langevin thermostat and Berendsen/MTK barostat for 10-100 ns. Use a 0.5-1.0 fs timestep. Repeat for 3 independent replicas with different random seeds.

- Analysis: Calculate ligand RMSD, protein-ligand contacts, and H-bond occupancy over time using

cpptrajorMDTraj. Discard the first 10% of each replica as equilibration.

Q5: What are the key differences between using an MLIP vs. a classical force field (like GAFF) for binding dynamics? A: The differences are significant and impact protocol design.

| Aspect | Classical Force Field (e.g., GAFF/AMBER) | Machine Learning Interatomic Potential (MLIP) |

|---|---|---|

| Energy Surface | Pre-defined functional form; fixed charges. | Learned from QM data; includes electronic polarization. |

| Computational Cost | Lower (~1-10x baseline). | Higher (~10-1000x classical, but ~10⁶x cheaper than QM). |

| Accuracy for Bonds | Good for equilibrium geometries. | Superior for describing bond breaking/forming & distortions. |

| Parameterization | Required for each new ligand; can be slow. | Transferable across chemical space covered in training. |

| Best Use in Binding | Long-timescale sampling, high-throughput screening. | Accurate binding pose refinement, reactivity, & specific interactions. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|

| MLIP Software (e.g., MACE, NequIP) | Core engine for calculating energies and forces with near-DFT accuracy during MD. |

| MD Engine (e.g., LAMMPS, OpenMM) | Integrates the MLIP to perform the numerical integration of Newton's equations of motion. |

System Prep Tools (e.g., pdb4amber, tleap) |

Standardizes protonation, solvation, and ionization for reproducible simulation setup. |

| QM Reference Dataset (e.g., ANI-1x, QM9) | Used for training/validating the MLIP or performing single-point energy checks on snapshots. |

Trajectory Analysis (e.g., MDTraj, cpptraj) |

Extracts key metrics (RMSD, RMSF, distances, energies) from simulation output files. |

| MM/PBSA or MM/GBSA Scripts | Calculates endpoint binding free energies from ensembles of MLIP-generated snapshots. |

| Enhanced Sampling Suites (e.g., PLUMED) | Interfaces with MLIP-MD to perform metadynamics or umbrella sampling for challenging unbinding events. |

| Visualization (e.g., VMD, PyMOL) | Critical for inspecting initial structures, simulation trajectories, and identifying artifacts. |

Visualizations

Diagram 1: MLIP Protein-Ligand Simulation Workflow

Diagram 2: MLIP Robustness Validation Framework

Debugging the Black Box: Solutions for Common MLIP Failures in MD

Diagnosing and Remedying Simulation Instabilities and Crashes

Troubleshooting Guide & FAQs

Q1: My simulation crashes immediately with a "Bond/angle stretch too large" error. What is the primary cause and fix?

A: This is typically caused by initial atomic overlap or an excessively high starting temperature. The interatomic potential calculates enormous forces, leading to numerical overflow.

- Immediate Fix: Minimize the initial structure using a simpler potential (e.g., classical force field) before applying the MLIP. Use a "soft start" protocol: run the first 100-200 steps with a very small timestep (0.1 fs) and heavy Langevin damping, gradually scaling to normal parameters.

- Preventive Protocol: Implement a three-step equilibration:

- Energy minimization with constraints on mobile species.

- NVT equilibration with a low-temperature thermostat (10-50K) for 1-2 ps.

- Progressive heating to target temperature over 5-10 ps.

Q2: During a long-running simulation, energy suddenly diverges to "NaN" (not a number). How do I diagnose this?

A: A "NaN" explosion indicates a failure in the MLIP's extrapolation regime. The configuration has moved far outside the training domain.

Diagnostic Table:

| Check | Tool/Method | Acceptable Threshold |

|---|---|---|

| Local Atomic Environment | Compute local_norm or extrapolation grade (model-specific). |

< 0.05 for most robust models. |

| Maximum Force | Check force output prior to crash. | > 50 eV/Å is a strong warning sign. |

| Collective Variable Drift | Monitor key distances/angles vs. training data distribution. | > 4σ from training set mean. |

Remediation Protocol:

- Rollback & Restart: Return to the last stable checkpoint (

-1000steps). - Apply a Bias: Introduce a soft harmonic restraint to a known stable geometry.

- Enhance Sampling: If the transition is of interest, switch to an enhanced sampling method (metadynamics, umbrella sampling) to properly sample the high-energy region.

Q3: My NPT simulation exhibits severe box oscillation or collapse. Is this a bug or a physical instability?

A: It can be either. First, rule out numerical/parameter mismatch.

Barostat Parameter Table for MLIPs (Typical Values):

| System Type | Target Pressure | Time Constant | Recommended Barostat |

|---|---|---|---|

| Liquid Water / Soft Materials | 1 bar | 5-10 ps | Parrinello-Rahman (semi-isotropic) |

| Crystalline Solid | 1 bar | 20-50 ps | Martyna-Tobias-Klein (MTK) |

| Surface/Interface | 1 bar (anisotropic) | 10-20 ps | Parrinello-Rahman (fully anisotropic) |

Experimental Protocol for Stable NPT:

- Equilibrate in NVT first for at least 10% of the planned simulation time.

- Couple the barostat only to dimensions that should fluctuate (e.g., Z-axis for surface).

- Use a timestep 25% smaller for NPT than for NVT (e.g., 0.5 fs vs 1 fs for reactive systems).

Q4: How do I distinguish between a genuine chemical reaction (desired) and a MLIP hallucination/instability?

A: This is critical for robust research. Implement a multi-fidelity validation protocol.

Workflow: Validation of Suspected Reaction Event

Q5: What are the essential reagents and tools for maintaining stable MLIP simulations?

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Ensuring Robustness |

|---|---|

| Reference DFT Dataset | Gold-standard energies/forces for spot-checking unstable configurations. |

| Committee of MLIPs | Using 2-3 different models (e.g., MACE, NequIP, GAP) for consensus validation. |

| Local Environment Analyzer | Script to compute σ-distance from training set for any atom (e.g., chemiscope, quippy). |

| Structure Minimizer | Tool for pre-simulation relaxation using a robust classical force field (e.g., FHI-aims, LAMMPS with REAXFF). |

| Trajectory Sanitizer | Utility to clean corrupted trajectory files and recover checkpoint data (e.g., ASE, MDTraj). |

| Enhanced Sampling Suite | Software for applying bias potentials to escape unstable regions (e.g., PLUMED, SSAGES). |

Q6: Are there systematic benchmarks for MLIP stability? What metrics should I track?

A: Yes. Track these Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) for every simulation.

MLIP Simulation Stability Benchmark Table:

| KPI | Measurement Method | Target for Robust Production |

|---|---|---|

| Mean Time Between Failure (MTBF) | Total simulation time / number of crashes. | > 500 ps for condensed phase. |

| Maximum Extrapolation | max(atomic_extrapolation_grade) over trajectory. |

< 0.1 for 99.9% of steps. |

| Energy Drift | Slope of total energy vs. time in NVE ensemble. | < 1 meV/atom/ps. |

| Conservation of Constants | Fluctuation in angular momentum (NVE). | ∆L < 1e-5 ħ per atom. |

Core Stability Testing Protocol:

- NVE Test: Run a 5-10 ps simulation of a well-equilibrated small system (≤ 50 atoms). Monitor total energy drift.

- Shear Test: Apply small, incremental shear strains to a crystal cell, checking for unphysical stress noise.

- High-T Test: Run a short (2-5 ps) simulation at 2x the intended temperature, checking for exaggerated instability rates.

Energy Conservation Tests and Correcting Drift in NVE Ensembles

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: My NVE simulation shows significant total energy drift (>0.01% per ns). What are the primary culprits and how do I diagnose them? A: Energy drift in NVE ensembles violates the fundamental assumption of microcanonical dynamics and directly challenges the robustness of the MLIP used. Follow this diagnostic protocol:

- Isolate the Source: Run a short (10-ps) simulation in the NVE ensemble from a well-equilibrated NPT configuration. Plot the contributions: Kinetic Energy (KE), Potential Energy (PE), and Total Energy (TE).

- Check Time Integrator: Use a symplectic integrator like Velocity Verlet. Ensure the timestep is appropriate (typically 0.5-1.0 fs for all-atom). Halve the timestep and rerun. A reduction in drift implicates integrator error.

- Stress-Test the MLIP: Perform a single-point energy evaluation on a trajectory snapshot. Then, displace one atom by 0.001 Å and re-evaluate. A large, discontinuous change in energy or forces indicates numerical instability or lack of smoothness in the MLIP's potential energy surface.

- Check Constraints: If using constraints (e.g., SHAKE for bonds with H), ensure they are correctly implemented and consistent with the integrator.

Diagnostic Workflow:

Q2: How do I perform a reliable energy conservation test for a new MLIP before production MD? A: A standardized energy conservation test is critical for evaluating MLIP robustness. Here is a definitive protocol:

Experimental Protocol: Energy Conservation Validation

- System Preparation: Solvate your molecule of interest (e.g., a small drug-like compound) in a cubic water box. Equilibrate thoroughly (NPT, 300K, 1 bar) for >100 ps using a classical force field.

- Initialization for NVE: Take the final equilibrated snapshot. Re-evaluate energies and forces using the target MLIP. Initialize velocities from a Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution for the desired temperature (e.g., 300K).

- Production NVE Run: Run a 20-50 ps simulation in the NVE ensemble using Velocity Verlet with a conservative timestep (0.5 fs). Do not apply any temperature or pressure coupling. Disable all barostats and thermostats.

- Data Analysis: Calculate the total energy