Beyond Force Metrics: A Practical Guide to Improving Stability and Convergence in Molecular Dynamics Simulations

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations are indispensable in drug discovery and materials science, yet achieving stable and converged results remains a significant challenge.

Beyond Force Metrics: A Practical Guide to Improving Stability and Convergence in Molecular Dynamics Simulations

Abstract

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations are indispensable in drug discovery and materials science, yet achieving stable and converged results remains a significant challenge. This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and scientists to enhance the reliability of their MD studies. We move beyond traditional force error metrics to explore foundational principles, advanced methodological strategies like machine-learning force fields and enhanced sampling, practical troubleshooting for common pitfalls, and rigorous validation techniques. By integrating insights from the latest research, this guide aims to equip professionals with the knowledge to design robust simulations, optimize computational resources, and generate thermodynamically meaningful data for biomedical applications.

Understanding the Roots of Instability and Poor Convergence in MD

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the difference between a system being "stable" and being "converged"?

A1: In molecular dynamics, stability often refers to the numerical robustness of a simulation—preventing it from "blowing up" or entering unphysical regions of phase space. Convergence, however, means that the statistical properties of interest (e.g., average energy, RMSD) have reached a steady state and their fluctuations are small relative to the infinite-time average.

A system can be numerically stable yet not converged. For instance, a simulation can run for microseconds without crashing (stable) but its measured properties might still be drifting because it has not adequately sampled the relevant conformational space (not converged) [1] [2].

Q2: My simulation has low force errors according to my MLFF training metrics. Why does it still become unstable?

A2: Low force errors on a training dataset do not guarantee simulation stability. This is because:

- Distributional Shift: During a simulation, the system can explore regions of phase space that were not represented in the original training data. The machine learning force field (MLFF) may make poor predictions on these new, out-of-distribution configurations, leading to unphysical forces and eventual instability [2].

- Error Accumulation: Small force errors can accumulate over thousands of integration steps, causing the system to gradually drift into an unphysical state, such as breaking bonds that should be stable at the simulated temperature [2].

- Insufficient Data: The training data may lack examples of rare but important events (e.g., transition states), making the model unreliable for long-timescale simulations where such events might occur [2].

Q3: How can I check if my simulation has reached equilibrium for the property I care about?

A3: You can perform the following checks:

- Time-series analysis: Plot the property of interest (e.g., potential energy, RMSD, radius of gyration) as a function of simulation time. Look for when the moving average of the property reaches a plateau and the fluctuations around this plateau remain small for a significant portion of the trajectory after a convergence time, ( t_c ) [1].

- Block averaging: Divide your trajectory into consecutive blocks. Calculate the average of your property within each block. If the block averages do not show a systematic trend and their variance is consistent with statistical noise, it is a good indicator of convergence.

- Start from different points: Run multiple simulations starting from different initial conditions (e.g., different velocities). If they all converge to the same average value for the property, you can have greater confidence in the result.

The following table summarizes the convergence characteristics of different property types:

Table 1: Convergence Behavior of Different Molecular Properties

| Property Type | Typical Convergence Time | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Structural Properties (e.g., average distance, angle) | Multi-microsecond trajectories often sufficient [1] | Depends mostly on high-probability regions of conformational space. |

| Dynamical Properties (e.g., diffusion coefficients) | Can require very long simulations [1] | Requires adequate sampling of molecular motion pathways. |

| Transition Rates / Free Energy Barriers | May not converge in currently accessible timescales [1] | Explicitly depends on thorough exploration of low-probability regions. |

Q4: What are some practical steps I can take to improve the stability and convergence of my simulations?

A4:

- Ensure Proper Equilibration: Double-check that temperature and pressure coupling parameters in your production run match those used during the NVT and NPT equilibration steps [3].

- Be Cautious with Time Steps: Discretization errors from too large a time step can introduce artifacts. For TIP4P water at 300 K, step sizes up to 7 fs (70% of the stability threshold) can be used, but this is system-dependent [4].

- Validate Your Topology: Use tools like

gmx checkandgmx energyto monitor your simulation's energy, temperature, and pressure for unexpected drifts or artifacts [5]. - Leverage Advanced Training: For MLFFs, consider methods like Stability-Aware Boltzmann Estimator (StABlE) Training, which uses system observables to correct instabilities without requiring additional quantum-mechanical calculations [2].

- Run Longer Simulations: For properties with biological interest, multi-microsecond trajectories are often necessary for convergence [1].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Simulation Instability and "Blow Ups"

Symptoms: The simulation crashes with errors about constrained bonds breaking, atoms flying apart, or numerical instability.

Possible Causes and Solutions:

- Cause 1: Incorrect topology or missing parameters.

- Solution: Carefully check for missing atoms or residues in your initial structure file. Use

pdb2gmxwith the correct force field and ensure all residue names and atom types are recognized. Manually parameterize any missing residues or molecules [5].

- Solution: Carefully check for missing atoms or residues in your initial structure file. Use

- Cause 2: Integration time step is too large.

- Cause 3: Machine learning force field (MLFF) instability.

- Solution: Retrain the MLFF using advanced methods like StABlE training, which incorporates system observables to penalize and correct unphysical trajectories [2]. Expand the training dataset's coverage of phase space via active learning.

Problem: Lack of Convergence in Key Observables

Symptoms: The average value of a property (e.g., RMSD, energy) continues to drift over time and does not reach a stable plateau.

Possible Causes and Solutions:

- Cause 1: Insufficient simulation time.

- Solution: Extend the simulation length. Research indicates that for many biomolecular systems, multi-microsecond trajectories are needed for biologically relevant properties to converge [1].

- Cause 2: The system started from a high-energy, non-equilibrium structure (e.g., directly from a crystal structure).

- Cause 3: The property of interest depends on sampling rare events or low-probability conformational states.

- Solution: Use enhanced sampling techniques (e.g., metadynamics, umbrella sampling) to force the system to explore these states. Be aware that convergence for such properties is one of the most challenging aspects of MD [1].

Problem: Discretization Artifacts in Measurements

Symptoms: Measured quantities like kinetic and configurational temperatures differ, or pressure profiles are non-uniform in a homogeneous system, even when the simulation appears stable.

Possible Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: The use of a numerically stable but relatively large time step introduces a discretization error. The simulation is effectively sampling a "shadow" Hamiltonian rather than the intended one [4].

- Solution 1 (Extrapolation): Run the simulation at two or more different time steps and extrapolate the results to a zero time step [4].

- Solution 2 (Reduction): Simply reduce the time step until the discretization error is smaller than your required statistical error [4].

- Solution 3 (Correction): For advanced users, use weighted thermostating or modified measurement expressions derived from backward error analysis to correct for the leading-order discretization error [4].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Assessing Convergence of an Observable

This protocol outlines a general method to test if a property from an MD trajectory has converged [1].

- Trajectory Preparation: Obtain a single, long, unrestrained MD production trajectory.

- Property Calculation: Calculate the property of interest ( A ) (e.g., RMSD, radius of gyration, potential energy) for every frame of the trajectory.

- Compute Running Average: Calculate the running average ( \langle A \rangle(t) ), which is the average of ( A ) from time 0 to time ( t ).

- Identify Convergence Time (( tc )): Examine the plot of ( \langle A \rangle(t) ) versus ( t ). The convergence time ( tc ) is the point after which the fluctuations of ( \langle A \rangle(t) ) remain small relative to its final value ( \langle A \rangle(T) ), where ( T ) is the total trajectory length.

- Check for Plateau: Verify that a significant portion of the trajectory (e.g., the second half) is spent in this fluctuating plateau state. A property is considered "equilibrated" if this condition is met.

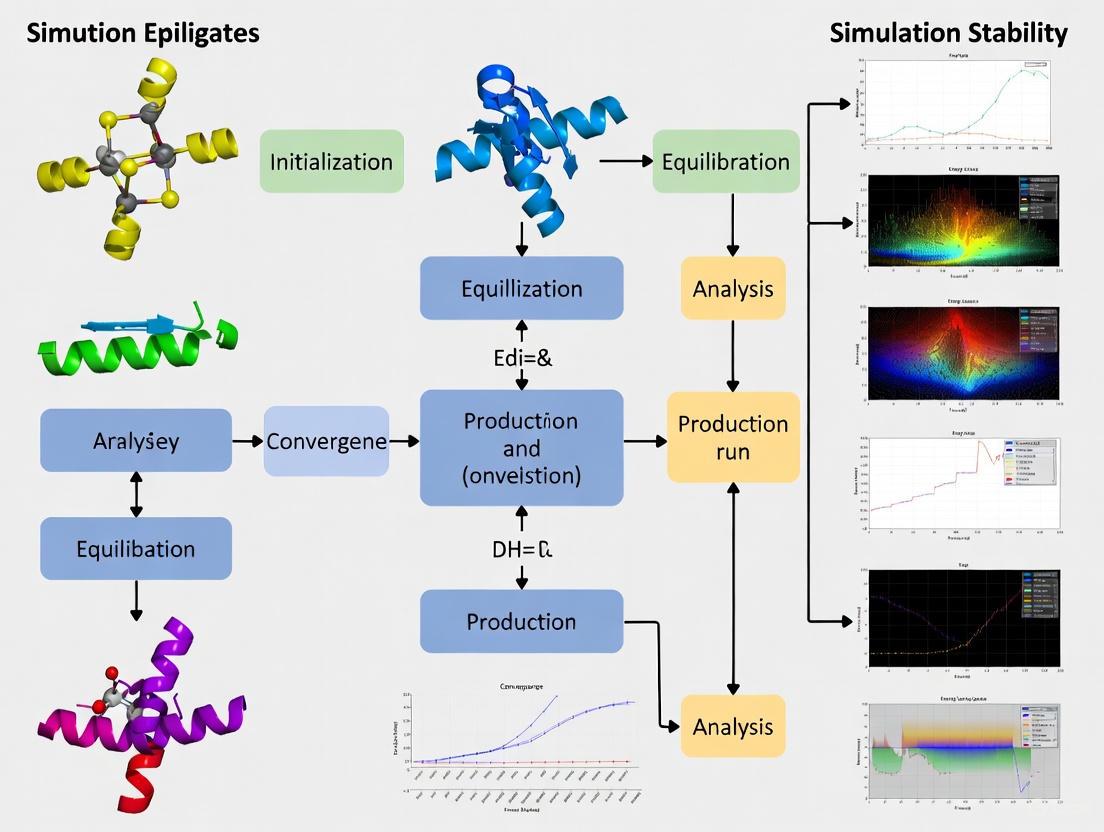

The logical flow of this analysis is shown below:

Protocol 2: StABlE Training for Machine Learning Force Fields

This protocol describes the methodology for the Stability-Aware Boltzmann Estimator training, which improves MLFF stability by leveraging system observables [2].

- Initial Training: Begin with a pre-trained MLFF model on a standard quantum-mechanical (QM) dataset of energies and forces.

- Parallel MD Exploration: Launch many short MD simulations in parallel using the current MLFF. This is done to efficiently seek out regions of phase space where the model becomes unstable.

- Identify Unstable Regions: Monitor these simulations for unphysical events (e.g., bond breaking in a non-reactive system, simulation collapse) or significant deviation from expected observables.

- Observable-Based Refinement: For configurations sampled from unstable regions, calculate a reference system observable (e.g., radial distribution function, virial stress). Compute the loss between the observable predicted by the MLFF-sampled trajectory and the reference observable.

- Differentiable Boltzmann Estimator: Use the Boltzmann Estimator to efficiently compute gradients through the MD simulation without backpropagation, enabling end-to-end gradient-based learning.

- Model Update: Update the MLFF parameters by combining the gradient signals from the standard QM loss (energies/forces) and the new observable-based loss. This penalizes the model for leading to unphysical configurations.

- Iterate: Repeat steps 2-6 until the model produces stable simulations and accurately reproduces the reference observables.

The following workflow illustrates this iterative self-improvement cycle:

Table 2: Key Software and Methodological "Reagents" for Stable MD

| Tool / Resource | Function | Relevance to Stability/Convergence |

|---|---|---|

| GROMACS [5] [6] | A versatile package for performing MD simulations and analysis. | The industry-standard engine for production MD. Proper setup of its parameters (.mdp options) is critical for stability. |

| StABlE Training [2] | A multi-modal training procedure for MLFFs. | Directly addresses the instability of MLFFs by using observables to correct unphysical predictions, moving beyond low force errors. |

| Backward Error Analysis [4] | A numerical analysis framework for understanding discretization errors. | Provides the theoretical foundation for identifying and correcting artifacts caused by finite time steps. |

| Convergence Assessment Protocol [1] | A defined method for checking equilibration of a property. | Offers a practical, quantitative workflow to determine if a simulation has run long enough for a property of interest. |

| Time-Series Analysis | Plotting running averages of key properties. | The primary diagnostic tool for visually assessing convergence during or after a simulation. |

| Potential of Mean Force (PMF) [7] | A free energy profile along a reaction coordinate. | Used to quantify the stability of specific molecular configurations or pathways, such as the energy gain from forming a columnar assembly. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) on MD Simulation Failures

FAQ 1: What are the most common causes of a simulation "blow-up," where the system energy becomes unphysical and the simulation crashes?

Simulation blow-ups, characterized by a sudden, catastrophic increase in system energy, are often caused by incorrect system setup rather than software bugs. The most common precursors are steric clashes (atoms placed too close together) and incorrectly defined bonded interactions. These errors generate immense, unphysical forces that propagate through the system. Initial energy minimization is designed to resolve minor clashes, but severe initial overlaps can produce forces too large for the integrator to handle, leading to instability. Ensuring a physically realistic initial structure and carefully validating the generated topology are the most effective preventive measures [5].

FAQ 2: My simulation fails immediately with "Atom XXX has an unphysical velocity." What does this mean and how can I fix it?

This error is a direct consequence of the unphysical forces described above. When atoms are subjected to extremely high forces (e.g., from a steric clash), the velocity Verlet integrator calculates correspondingly high velocities for the next time step. If these velocities exceed a sanity threshold, GROMACS will halt the simulation to prevent a full blow-up [5]. To resolve this, you should: 1) Re-run energy minimization to ensure all clashes are resolved, 2) Check your initial structure for missing atoms or incorrect bond lengths [5], and 3) If the problem persists, consider using shorter time steps or applying position restraints to allow the system to equilibrate gradually.

FAQ 3: Why does pdb2gmx fail with "Residue not found in residue topology database," and how can I add a new residue?

This error occurs when the force field you have selected does not contain a definition for the residue or molecule in your coordinate file [5]. Force fields are not "magical"; they can only handle building blocks (residues) that are provided in their database. Your options are:

- Renaming: Check if the residue exists in the database under a different name and rename your residue accordingly [5].

- Find a Topology: Search the literature for a topology file (

*.itp) for your molecule that is compatible with your force field and include it manually [5]. - Parameterize Yourself: If no parameters exist, you must parameterize the residue yourself, which is a significant undertaking even for experts. This involves deriving bond, angle, and charge parameters from quantum mechanical calculations or experimental data [8] [5].

FAQ 4: How can I avoid "Out of memory" errors when running analysis on large trajectories?

"Out of memory" errors during analysis indicate that the system does not have enough RAM to hold the required data. The computational cost of analysis can scale poorly (e.g., order N²) with the number of atoms or trajectory frames [5]. Solutions include:

- Reduce Scope: Analyze a subset of atoms or a shorter segment of the trajectory [5].

- Check System Size: A common mistake is generating a simulation box that is far too large (e.g., confusion between Ångström and nm can create a box 10³ times larger than intended) [5].

- Upgrade Hardware: Use a computer with more RAM [5].

FAQ 5: What does "Invalid order for directive" mean in my topology file?

This error means the directives in your .top or .itp files are in the wrong sequence. The topology file has strict rules for the order of sections [5]. The force field must be fully defined before any molecules are described. A common mistake is placing a [moleculetype] directive or including a molecule's itp file before the necessary [atomtypes] or other parameter directives. Always #include the force field first, followed by molecule definitions, to ensure the correct order [5].

Troubleshooting Guide: From Errors to Solutions

This guide provides a structured workflow to diagnose and fix the most common MD simulation failures.

Troubleshooting Logic and Workflow

The following diagram outlines a systematic approach to diagnosing and resolving common MD simulation failures.

Advanced Protocol: Improving Thermal Stability Prediction

A major challenge in MD is the accurate prediction of material properties like thermal stability. Conventional simulations with periodic boundary conditions and high heating rates can overestimate decomposition temperatures (Td) by over 400 K [9]. The following optimized protocol, developed for energetic materials but applicable to other systems, significantly improves reliability.

Optimized MD Protocol for Thermal Stability Ranking [9]:

- Model Preparation: Use nanoparticle models instead of periodic bulk models. Surface initiation of decomposition is critical for accurate Td.

- Potential Selection: Employ a Neural Network Potential (NNP) for a more accurate description of bond breaking and formation compared to classical force fields.

- Simulation Parameter: Apply an extremely low heating rate (e.g., 0.001 K/ps) during the heating simulation to better approximate experimental conditions.

- Data Analysis: Use the Kissinger analysis method on data from multiple heating rates to establish a robust Td and correlate it with experimental values.

Performance of Optimized vs. Traditional Protocol [9]:

| Simulation Protocol | Model Type | Heating Rate | Average Td Error vs. Experiment | Correlation with Experiment (R²) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional | Periodic Bulk | High (e.g., 1 K/ps) | > 400 K | 0.85 |

| Optimized | Nanoparticle with NNP | Low (0.001 K/ps) | ~80 K | 0.96 |

This protocol demonstrates how addressing fundamental limitations (model, potential, and kinetics) can dramatically improve simulation convergence with experimental reality.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table: Key Computational Reagents for Stable MD Simulations

| Item/Reagent | Function in Simulation | Key Consideration for Stability |

|---|---|---|

| Force Field [8] | Defines the potential energy function and parameters for bonded and non-bonded interactions. | Choice is critical. Must be appropriate for the system (e.g., biomolecules, polymers, materials). Mixing force fields is not recommended [5]. |

| Residue Topology Database [5] | A library of building blocks (e.g., amino acids, nucleotides, solvents) for the force field. | If your molecule is not in the database (rtp file), pdb2gmx will fail. Residue and atom names must match exactly [5]. |

| Neural Network Potential (NNP) [9] | A machine-learning-driven potential that offers higher accuracy for modeling reactive processes and complex interactions. | Used in advanced protocols to replace classical force fields, significantly improving predictions for properties like thermal stability [9]. |

| Position Restraint File [5] | Applies harmonic restraints to atom positions, typically during initial equilibration. | Prevents large movements from unresolved steric clashes. Must be included in the correct order within the topology file, directly after its corresponding [moleculetype] [5]. |

Future Directions: Enhancing Stability through Multiscale and AI Methods

The future of robust MD simulation lies in bridging scale and accuracy gaps. Current research focuses on two key paradigms:

1. Multiscale Simulation Methodologies: The integration of different computational models is crucial for studying complex systems like oil-displacement polymers or drug delivery nanoparticles. For instance, studying drug release from a hexagonal liquid crystalline phase requires atomic-level detail to understand drug partitioning and the interaction of the polymer shell with the lipid interface [10]. A multiscale approach can link this detailed view to the larger-scale behavior of the entire nanoparticle, leading to more stable and predictive models of system performance [11] [10].

2. Integration of Artificial Intelligence: AI is being leveraged to directly improve simulation stability and accuracy. As demonstrated in the thermal stability protocol, Neural Network Potentials (NNPs) can dramatically reduce errors by providing a more precise quantum-mechanical description of interactions [9]. Furthermore, AI and machine learning are being combined with MD in drug discovery to enhance target modeling, binding pose prediction, and virtual screening, creating more reliable workflows for identifying and optimizing lead compounds [12]. The development of automated, AI-driven parameterization workflows also promises to reduce human error and improve the reproducibility of force field development [8].

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

FAQ: Addressing Common Force Field Challenges

1. Why does my simulated supramolecular structure not form the expected ordered assembly?

This is a common issue where the force field may not accurately capture the delicate balance of non-covalent interactions. Even small errors in parametrization are amplified in self-assembling systems due to their repetitive nature [13]. The stability of a pre-built fiber structure varies significantly across force fields; for instance, it remains stable in CHARMM Drude, GAFF, and polarized Martini but collapses in standard CGenFF [13]. Before long simulations, verify your force field's performance for your specific molecular motifs by checking dedicated studies or databases [8] [13].

2. How does the choice of force field impact the prediction of hydration free energy (HFE), a key property in drug design?

Systematic errors in HFE prediction are often linked to specific functional groups [14]. For example:

- Nitro-groups: Tend to be over-solubilized in CGenFF but under-solubilized in GAFF.

- Amine-groups: Are consistently under-solubilized, more severely in CGenFF.

- Carboxyl groups: Are over-solubilized, more significantly in GAFF [14]. If your molecule contains these groups, be aware of these inherent biases. Cross-validate results with alternative force fields or experimental data when possible.

3. My simulation fails to reach equilibrium. Could the force field be a cause?

Yes. The convergence of properties is highly dependent on the force field's accurate description of the potential energy surface, particularly torsional barriers [15]. An inadequate force field can trap the system in incorrect local energy minima, preventing the exploration of the true conformational space. This is distinct from the issue of simply needing longer simulation times. Ensuring you are using a modern, well-parameterized force field for your specific chemical space is a critical first step in achieving convergence [16] [15].

4. The chemical molecule I want to simulate is not well-covered by standard force fields. What are my options?

Traditional "look-up table" approaches can struggle with expansive chemical space [16]. Modern solutions include:

- Specialized Parameter Builders: Tools like the OPLS4 Force Field Builder allow for optimizing custom torsion parameters for novel chemistry [17].

- Data-Driven Force Fields: New approaches like ByteFF use machine learning to predict parameters for a vast range of drug-like molecules, offering broad, accurate coverage without manual intervention [16] [18].

- Polarizable Force Fields: For cases where electronic polarization is critical, models like CHARMM Drude offer higher accuracy, though at a significantly increased computational cost [13].

5. When should I use an all-atom vs. a coarse-grained force field?

The choice involves a trade-off between computational efficiency and chemical detail [8].

- All-atom (AA) force fields (e.g., GAFF, CGenFF, CHARMM Drude) provide the highest level of detail, representing every atom. They are essential for studying specific atomic interactions, like hydrogen bonding, but are computationally expensive [13].

- Coarse-grained (CG) force fields (e.g., Martini) group multiple atoms into a single interaction "bead." They sacrifice chemical details to simulate larger systems and longer timescales, making them ideal for studying large-scale self-assembly or membrane dynamics [8] [13].

Troubleshooting Guide: Force Field Selection and Validation

| Problem Description | Underlying Force Field Issue | Recommended Corrective Actions |

|---|---|---|

| Unphysical collapse or distortion of a known stable structure during simulation. | The force field does not place the experimental structure in a free energy minimum; non-bonded or torsional parameters may be inaccurate [13]. | 1. Test the stability of your structure with multiple force fields (e.g., GAFF, CGenFF).2. For self-assembling systems, consider polarized models like CHARMM Drude or polarized Martini [13].3. Check for known issues with your functional groups in the literature [14]. |

| Systematic error in predicting solvation or binding free energies. | Inaccurate atomic charges or van der Waals parameters, often specific to certain functional groups, lead to erroneous solute-solvent interactions [14]. | 1. Identify problematic functional groups in your molecule (e.g., nitro, amine) [14].2. Use alchemical free energy methods to validate HFE predictions against experimental data if available.3. Consider a data-driven force field like ByteFF for improved charge and parameter assignment [16]. |

| Failure to observe spontaneous self-assembly or correct conformational distribution. | The energy landscape is incorrect, often due to poor-quality torsion parameters that bias conformational sampling [16] [15]. | 1. Prioritize force fields with a focus on accurate torsional profiles (e.g., OPLS4, ByteFF) [16] [17].2. Manually refine torsional parameters using a force field builder tool [17].3. Increase system size to promote nucleation of ordered structures [13]. |

| Poor transferability of parameters for novel molecules. | Traditional force fields rely on discrete atom types and look-up tables, which lack coverage for unexplored chemical environments [16]. | 1. Adopt a force field with a modern chemical perception approach, such as OpenFF (using SMIRKS) or ByteFF (using a Graph Neural Network) [16].2. Use a machine learning-based parameterization workflow to generate consistent parameters [18]. |

Key Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol: Benchmarking Force Field Performance for Supramolecular Assembly

This protocol is designed to assess a force field's ability to model self-assembling systems, based on the methodology from studies like [13].

1. Research Question: How do different force fields perform in simulating the spontaneous assembly and stability of a supramolecular fiber?

2. System Setup:

- Molecule: A derivative of 1,3,5-trisamidocyclohexane (CTA), which is known to form ordered fibers via trifold hydrogen-bonding [13].

- Force Fields for Comparison: A selection of all-atom, coarse-grained, and polarizable force fields (e.g., GROMOS, CGenFF, CHARMM Drude, GAFF, Martini, polarized Martini) [13].

- Software: A molecular dynamics package like GROMACS, CHARMM, or OpenMM.

3. Simulation Details:

- Spontaneous Self-Assembly: Place 8 CTA molecules randomly in a small solvated box (e.g., a 4.5 x 4.0 x 4.1 nm³ dodecahedron). Run multiple independent simulations for a defined time (e.g., 500 ns) [13].

- Fiber Stability: Build a pre-assembled stack of 24 CTA molecules based on a known crystal structure. Simulate this fiber in the NVT ensemble for ~300 ns or until collapse [13].

4. Key Metrics for Analysis:

- Structural Order: Monitor the number of hydrogen bonds between CTA amides over time [13].

- Aggregation State: Calculate the Solvent Accessible Surface Area (SASA) to track the formation of compact clusters [13].

- Visual Inspection: Analyze final snapshots for the formation of long-range ordered structures.

5. Expected Outcomes: As demonstrated in [13], different force fields will yield vastly different results. Some may form stable, ordered fibers, while others may produce disordered clusters or cause a pre-built fiber to collapse. This protocol directly reveals the suitability of a force field for simulating self-assembling systems.

Performance Comparison of Common Force Fields

Table 1: Comparative analysis of force fields for simulating a CTA fiber system. Data adapted from [13].

| Force Field | Type / Resolution | Spontaneous Assembly (500 ns) | Fiber Stability (300 ns) | Computational Cost (approx.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GROMOS | United-atom | Forms compact, slowly ordering cluster | Collapses after ~130 ns | ~8 hours/ns |

| CGenFF | All-atom | Forms flexible, unordered cluster | Collapses immediately | ~8 hours/ns |

| CHARMM Drude | All-atom (Polarizable) | Forms flexible cluster (shorter simulation) | Remains stable | ~28 hours/ns |

| GAFF | All-atom | Forms several ordered dimers | Remains stable | N/A |

| Martini | Coarse-grained | Forms compact cluster | Collapses | ~3 minutes/ns |

| Polarized Martini | Coarse-grained (Polarizable) | Forms small, ordered fragments | Remains stable | ~3 minutes/ns |

Table 2: Functional group-specific errors in Hydration Free Energy (HFE) prediction for generalized force fields. Based on analysis of over 600 molecules from the FreeSolv dataset [14].

| Functional Group | CGenFF Tendency | GAFF Tendency | Molecular Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nitro-group (-NO₂) | Over-solubilized in water | Under-solubilized in water | Affects solvation and membrane permeability predictions. |

| Amine-group (-NH₂) | Under-solubilized | Under-solubilized (less than CGenFF) | May lead to underestimation of aqueous solubility. |

| Carboxyl-group (-COOH) | Over-solubilized | More over-solubilized than CGenFF | Can overestimate solubility and influence protonation state modeling. |

Workflow Diagrams

Force Field Parametrization Workflow

Force Field Selection Logic

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential resources for force field application and development in computational research.

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function | Key Features / Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Generalized Force Fields (GAFF, CGenFF) | Software Parameters | Provide pre-derived parameters for a wide range of drug-like small molecules. | GAFF uses AM1-BCC charges; CGenFF uses charges from QM interaction with water. Good starting points for most organic molecules [14]. |

| Specialized Force Fields (CHARMM Drude) | Software Parameters | An all-atom polarizable force field for more accurate modeling of electrostatic interactions. | Higher computational cost but can be critical for systems where electronic polarization is significant [13]. |

| Coarse-Grained Models (Martini) | Software Parameters | Accelerate simulations by grouping atoms into interaction beads, enabling longer and larger simulations. | Sacrifices atomic detail for scale. Essential for studying processes like large-scale membrane remodeling [8] [13]. |

| Force Field Builder (OPLS4) | Software Tool | Allows researchers to generate and optimize custom torsion parameters for novel molecules. | Ensures force field extensibility into new chemical space not covered by the core parameter set [17]. |

| Data-Driven Force Fields (ByteFF, OpenFF) | Software / ML Model | Use machine learning to predict consistent force field parameters directly from chemical structure. | A modern approach offering broad, accurate chemical space coverage and improved transferability [16] [18]. |

| Force Field Databases (MolMod, openKim) | Data Repository | Collect and categorize force fields and parameters for different materials. | Provides a centralized resource for finding and comparing force fields [8]. |

| Alchemical Free Energy Tools (FEP+) | Software / Protocol | Calculate precise binding affinities or hydration free energies using advanced sampling. | Used for critical validation of force field performance against experimental data [14] [17]. |

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation is an essential computational method for understanding the physical basis of the structures, functions, and dynamics of biological macromolecules. It provides detailed information on the fluctuations and conformational changes of proteins and nucleic acids that are often difficult to capture experimentally [19]. However, a fundamental challenge persists: the time and length scale sampling problem. Biological phenomena occur across vast spatial and temporal ranges, from atomic vibrations (femtoseconds) to cellular processes (seconds), while all-atom MD simulations face significant computational constraints [20] [21]. This technical support guide addresses how to identify, troubleshoot, and mitigate sampling issues to improve simulation stability and convergence.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: How long does my simulation need to run to reach equilibrium? There is no universal simulation time that guarantees equilibrium. Convergence depends on the system size, property of interest, and the biological process being studied. For some average structural properties, multi-microsecond trajectories may be sufficient, but transition rates to low-probability conformations may require significantly more time [15]. The key is to perform convergence tests for your specific system and properties of interest.

Q2: How can I verify if my simulation has converged and reached true equilibrium? Convergence should not be assessed by a single metric. A robust approach includes:

- Monitoring time series of multiple properties (RMSD, energy, radius of gyration)

- Checking if averages and fluctuations stabilize to a relatively constant value (plateau)

- Comparing results from independent simulations starting from different initial conditions

- Ensuring that the system is not trapped in a deep local energy minimum that prevents adequate sampling of conformational space [15]

Q3: What is the difference between partial and full equilibrium in MD simulations? A system can be in partial equilibrium when some properties have reached their converged values while others have not. This occurs because different properties depend on different regions of the conformational space. Average properties (like distances between domains) may converge relatively quickly as they depend mainly on high-probability regions, while properties like free energy and transition rates require thorough exploration of low-probability regions and thus longer simulation times [15].

Q4: How do I select appropriate temporal and spatial scales for my biological question? The appropriate scale depends entirely on the biological phenomenon under investigation. For fast processes like side-chain rotations, nanoseconds may suffice. For larger conformational changes or protein folding, microseconds to milliseconds or longer may be required [20] [21]. Spatially, consider whether your question addresses single-molecule behavior, protein complexes, or cellular environments, as this determines the required system size and model complexity.

Troubleshooting Guides

Diagnosing Sampling Problems

| Symptom | Possible Causes | Diagnostic Tests | Solutions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-converging averages | Simulation time too short; trapped in local minimum | Calculate running averages; compare multiple independent runs | Extend simulation time; enhance sampling techniques; increase temperature |

| High variance in properties | Inadequate phase space sampling; unstable integrator | Monitor energy drift; check property distributions | Adjust thermostat/barostat; use longer equilibration; check force field parameters |

| Unphysical structural changes | Incorrect force field; poor solvation; parameter errors | Compare to experimental data (NMR, crystallography) | Validate with known structural properties; check solvent model; review system preparation |

| Slow conformational transitions | High energy barriers; insufficient simulation time | Calculate potential energy landscape; monitor dihedral transitions | Implement enhanced sampling (metadynamics, replica exchange) |

Quantitative Data for Simulation Planning

Table 2: Characteristic Time Scales of Biological Processes

| Biological Process | Typical Time Scale | Minimum Recommended Simulation | Key Convergence Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Side-chain rotations | Picoseconds - nanoseconds | 10-100 ns | Dihedral angle distributions |

| Loop motions | Nanoseconds - microseconds | 0.1-10 μs | RMSD, distance fluctuations |

| Domain movements | Microseconds - milliseconds | 10-100+ μs | Inter-domain distances, cross-correlations |

| Protein folding | Microseconds - seconds | 1+ ms | RMSD, native contacts, energy landscape |

| Allosteric transitions | Nanoseconds - milliseconds | 1-100+ μs | Dynamic cross-correlation, contact maps |

Table 3: System Size Considerations

| System Type | Typical Atom Count | Recommended Minimum Simulation Time | Computational Resource Estimate* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Small peptide (e.g., dialanine) | 100-1,000 atoms | 100 ns - 1 μs | Hours - days on single GPU |

| Medium protein (25-50 kDa) | 50,000-100,000 atoms | 1-10 μs | Days - weeks on single GPU |

| Large complex (e.g., ribosome) | 1-3 million atoms | 0.1-1 μs | Weeks - months on multi-GPU cluster |

| Viral envelope (e.g., SARS-CoV-2) | 300+ million atoms | 10-100 ns | Months - years on supercomputer |

*Resource estimates assume modern GPU acceleration and vary significantly by hardware and software efficiency.

Essential Methodologies

Protocol: Convergence Testing for Equilibrium Verification

Objective: To establish whether a simulation has reached thermodynamic equilibrium and properties have converged.

Procedure:

- Run multiple independent simulations starting from different initial conditions (e.g., different velocities, slightly different structures).

- Calculate time series of key properties (RMSD, potential energy, radius of gyration, secondary structure content).

- Compute running averages for each property throughout the trajectory.

- Monitor fluctuations around the average - they should remain small after convergence time.

- Compare histograms of property distributions from different trajectory segments.

- Check autocorrelation functions - they should decay within the simulation time for equilibrated systems.

Interpretation: A system can be considered equilibrated with respect to a specific property when the fluctuations of its running average remain small for a significant portion of the trajectory after some convergence time tc [15].

Protocol: Dynamic Cross-Correlation Analysis

Objective: To identify networks of correlated motions that may indicate allosteric pathways or functional dynamics.

Procedure using GROMACS and Bio3D:

- Generate MD trajectory using GROMACS with appropriate simulation parameters.

- Ensure trajectory stability by checking energy conservation and structural integrity.

- Process trajectory to remove rotational and translational motions.

- Calculate covariance matrix using GROMACS

g_covaror Bio3D'sdccmfunction: where Δri is the displacement vector of atom i [22]. - Compute cross-correlation coefficients:

- Visualize results as a dynamical cross-correlation matrix (DCCM) where positive values (0 to 1) indicate correlated motion and negative values (-1 to 0) indicate anti-correlated motion [22].

Troubleshooting: Poor convergence of cross-correlations may indicate insufficient sampling of relevant conformational states.

Workflow Diagram: Sampling Problem Diagnosis

Diagram 1: Sampling Problem Diagnosis Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Software Tools for Addressing Sampling Challenges

| Tool Name | Primary Function | Application to Sampling Problems | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| GROMACS | Molecular dynamics simulator | Production MD runs with high performance | Advanced GPU acceleration; Multiple force fields |

| Bio3D (R package) | Dynamics analysis | Cross-correlation and PCA analysis | DCCM calculation; Principal component analysis |

| AMBER | MD simulation and analysis | Enhanced sampling techniques | Advanced force fields; Replica exchange MD |

| VMD | Trajectory visualization | Identify sampling deficiencies | Interactive analysis; Order parameters |

| PLUMED | Enhanced sampling | Overcoming energy barriers | Metadynamics; Umbrella sampling |

Table 5: Critical Force Fields and Their Applications

| Force Field | Best For | Sampling Considerations | Known Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| CHARMM36 | Biomolecules in physiological conditions | Accurate lipid/protein interactions | Limited small molecule parameters |

| AMBER ff19SB | Proteins | Improved side-chain torsions | Less tested for membrane systems |

| OPLS-AA/M | Organic molecules and proteins | Good liquid properties transferability | Fewer protein-specific adjustments |

| Martini | Coarse-grained long simulations | Extended spatial and temporal scales | Loss of atomic detail |

Advanced Sampling Strategies

Enhanced Sampling Techniques

For systems with high energy barriers or rare events, consider these advanced methods:

Replica Exchange MD (REMD)

- Run multiple simulations at different temperatures

- Periodically attempt exchanges between replicas

- Enables better crossing of energy barriers

- Computational cost increases with system size

Metadynamics

- Add bias potential to discourage revisiting sampled states

- Requires careful selection of collective variables

- Can reconstruct free energy surfaces

- Risk of overfilling if simulation too short

Accelerated MD

- Raise energy minima without affecting transition states

- No need for predefined reaction coordinates

- Good for exploring conformational space

- Can distort kinetics

Relationship Between System Properties and Sampling Requirements

Diagram 2: System Properties to Sampling Requirements Mapping

Best Practices for Improved Convergence

Always run multiple independent simulations - Convergence should be verified across runs, not within a single trajectory.

Match simulation time to biological process - Consult Table 2 for guidance on appropriate time scales.

Use enhanced sampling judiciously - These methods can accelerate convergence but require validation.

Monitor simulation stability first - Before assessing convergence, ensure the simulation is physically stable (energy conservation, reasonable fluctuations).

Report convergence metrics transparently - Include running averages, multiple independent runs, and statistical uncertainties in publications.

Consider partial equilibrium - For large systems, recognize that some properties may converge while others require more time [15].

By implementing these troubleshooting guides, methodologies, and best practices, researchers can significantly improve the reliability and interpretability of their MD simulations, leading to more robust conclusions about biological function and mechanism.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My simulation's pressure is unstable during equilibration. What might be wrong? Instabilities in pressure (and temperature) are common and often traceable to the system setup [23]. The causes can include:

- Inappropriate Algorithm Choice: The selected barostat (pressure control) or thermostat (temperature control) may not be suitable for your system. For example, the Berendsen barostat is good for initial equilibration as it strongly dampens fluctuations, but the Parrinello-Rahman barostat is recommended for production runs to generate a correct ensemble [23].

- Poor Coupling Parameters: An incorrect coupling time constant can lead to oscillations or drifts. The time constant should be chosen to match the natural fluctuations of your system.

- System Preparation Errors: An initial structure with atomic overlaps, an incorrectly sized simulation box, or an improper neutralization procedure can create high local forces that no barostat can easily correct.

Q2: How can I tell if my simulation has truly reached equilibrium? Reaching equilibrium is critical for obtaining reliable results. Do not rely solely on the stabilization of potential energy or density, as these can converge rapidly while the system overall has not [24] [15]. A more robust approach includes:

- Monitoring Multiple Properties: Track the convergence of the Radial Distribution Function (RDF), especially between large, slow-moving components like asphaltenes in complex mixtures. The system may only be considered balanced when these RDF curves have converged [24].

- Checking System-Specific Metrics: Monitor the root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) of a biomolecule, or observe if key properties (like distances between domains) fluctuate around a stable average for a significant portion of the trajectory [15].

- Allowing Sufficient Time: Equilibration times are often underestimated. If properties have not stabilized, you must extend the equilibration phase [23].

Q3: I get a "Residue not found in topology database" error. What should I do?

This error occurs when the software (e.g., pdb2gmx in GROMACS) cannot find a definition for a molecule in your structure within the chosen force field [5]. Your options are:

- Check Residue Naming: Ensure the residue name in your coordinate file matches the name used in the force field's database.

- Use a Different Force Field: A residue might be defined in another supported force field.

- Create a Topology Manually: If the molecule is a ligand or non-standard residue, you cannot use

pdb2gmx. You must create a topology for it yourself using other tools or by manually defining the parameters, and then include this file in your system's topology [5].

Q4: Why is correct system neutralization so important? In simulations employing Periodic Boundary Conditions (PBC), a non-neutral total system charge leads to unphysical infinite electrostatic self-interactions, which can destabilize the simulation and produce meaningless results [23]. Neutralization with counterions ensures the integrity of long-range electrostatic calculations (like the Particle Mesh Ewald method) and models the physiological or experimental ionic environment accurately.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Convergence Failure in Energy Minimization Energy minimization is a prerequisite for equilibration. Failure to converge indicates a problem with the initial system state [23].

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Severe Atomic Overlaps | Check the initial structure for unrealistically close atoms using visualization software. | Perform a two-stage minimization: first with the steepest descent algorithm to resolve large clashes, then with the conjugate gradient method for finer convergence. |

| Incorrect Topology | Verify all bonds, angles, and charges in the topology file. Look for missing parameters or incorrect atom types. | Use tools like gmx pdb2gmx carefully to generate topologies. For non-standard molecules, ensure their manually created topology is correct and complete. |

| Insufficient Minimization Steps | The log file reports that the maximum number of steps was reached without convergence. | Increase the number of steps (nsteps) in the minimization parameters (.mdp file). |

Problem: Unphysical Densities or Volumes After Equilibration If the system density does not match the expected experimental value, the system setup is likely at fault.

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Incorrect Solvent Model | Compare the simulated density of a pure solvent box with its known experimental value. | Select a solvent model (e.g., SPC, TIP3P, TIP4P) that is well-parameterized with your chosen force field to reproduce accurate densities [25] [26]. |

| Improper Box Size or Solvation | Check if the box has sufficient padding (e.g., 1.0 nm minimum) between the solute and the box edge. | Use the gmx solvate command with a correctly sized box. Ensure the solvent number and placement yield a realistic density before equilibration [23]. |

| Inaccurate Neutralization/Ion Placement | Check the system's final ion distribution; ions may be clustered rather than evenly dispersed. | Use tools like gmx genion to replace solvent molecules with ions. Consider a subsequent energy minimization after ion placement to resolve any new overlaps [23]. |

Problem: Instability During the Production Run A simulation that crashes or shows wild fluctuations after a stable equilibration suggests an underlying issue.

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Incorrect Boundary Conditions | Verify that PBC are correctly applied in all directions and that the chosen treatment for long-range electrostatics (e.g., PME) is active. | In the .mdp file, set pbc = xyz and coulombtype = PME. Always process trajectories with gmx trjconv -pbc mol for analysis. |

| Faulty Temperature/Pressure Control | Examine the temperature and pressure logs for consistent, large deviations from the set point. | Switch to more stable thermostats/barostats for production (e.g., Nosé-Hoover thermostat, Parrinello-Rahman barostat). Adjust coupling time constants [23]. |

| Hidden Topology Error | The system ran fine for tens of nanoseconds before crashing. A rare, high-energy conformation may have exposed a faulty parameter. | Scrutinize the topology for all molecules, paying special attention to non-standard residues or ligands. Re-run the parameterization if necessary. |

Experimental Protocols & Data

Validating Solvent Model and Neutralization Setup This protocol outlines how to validate key aspects of your system setup using a simple solvent-box simulation, a critical step before running a complex, resource-intensive production simulation [26].

- System Construction: Create a cubic box filled only with water molecules (e.g., SPC, TIP3P) using

gmx solvate. - Neutralization and Ion Addition: Add ions to the system to not only neutralize it but also to achieve a desired ionic concentration (e.g., 150 mM NaCl) using

gmx genion. - Simulation Parameters:

- Energy Minimization: Use the steepest descent algorithm until the maximum force is below a set threshold (e.g., 1000 kJ/mol/nm).

- Equilibration: Perform a two-phase equilibration in the NVT and NPT ensembles for at least 100 ps each, using standard thermostats and barostats.

- Production Run: Run an NPT simulation for 1-5 ns.

- Data Collection and Analysis:

- Calculate the average density of the system over the production run.

- Calculate the radial distribution function (RDF) between ions and water oxygen atoms to examine the solvation structure.

- Validation: Compare the simulated density and RDF profiles against known experimental and benchmark simulation data [26]. Successful replication indicates a correct setup.

Quantitative Data from System Setup Validation

Table 1: Example Density Validation for Ionic Liquids at 293 K and 0.1 MPa [26]

| Ionic Liquid | Simulated Density (kg/m³) | Experimental Density (kg/m³) | Relative Deviation (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| [Emim][BF4] | 1298.5 | 1297.0 | 0.1% |

| [Bmim][BF4] | 1200.1 | 1203.4 | -0.3% |

| [Bmim][PF6] | 1325.8 | 1372.0 | -3.4% |

| [Bmim][Tf2N] | 1415.2 | 1430.0 | -1.0% |

Table 2: Key Convergence Metrics for Assessing Equilibration [24] [15]

| Property to Monitor | Time to Converge | Significance for System Equilibrium |

|---|---|---|

| Density / Potential Energy | Fast (ps-ns) | Necessary but not sufficient. Rapid convergence does not guarantee the system is fully equilibrated [24] [15]. |

| Pressure | Slower than energy | Requires more time to stabilize due to its sensitivity to atomic contacts and volume changes. |

| Radial Distribution Function (RDF) | Can be very slow (ns-μs) | A more robust indicator. Convergence of RDFs, especially between large components, suggests structural equilibrium [24]. |

| Root-Mean-Square Deviation (RMSD) | System-dependent | Can indicate the biomolecule has relaxed from its starting conformation, but may not reflect full conformational sampling [15]. |

System Setup and Stability Relationship

The following diagram illustrates the logical chain of how initial system setup decisions directly impact simulation stability and the validity of the results.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Components for Robust Molecular Dynamics System Setup

| Item / Resource | Function / Purpose | Example(s) / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Force Fields | Provides the set of mathematical functions and parameters that describe the potential energy of the system. | GROMOS 53A6/54A7 [25], AMBER, CHARMM. Choice depends on the system (proteins, lipids, ionic liquids). |

| Solvent Models | Represents the water and/or other solvent environment in the simulation. | SPC, TIP3P, TIP4P for water. Must be compatible with the chosen force field [25] [26]. |

| Simulation Software | The computational engine that performs the numerical integration of the equations of motion. | GROMACS [5] [23], AMBER, NAMD. GROMACS is widely used for its speed and extensive toolset. |

| Visualization Tools | Used to inspect initial structures, intermediate results, and final trajectories. | VMD, PyMOL, Chimera. Critical for diagnosing structural problems like atomic overlaps. |

| Parameterization Tools | Helps generate topologies and force field parameters for non-standard molecules (e.g., drugs, ligands). | CGenFF, ACPYPE, SwissParam. Essential for incorporating molecules not in the standard force field database [5]. |

| Ion Parameters | Pre-optimized parameters for ions (Na+, Cl-, K+, etc.) to ensure correct solvation free energy and behavior. | Included in major force fields. Specialized parameter sets, like GROMOS-RONS for reactive species, are also available [25]. |

Advanced Strategies for Robust Simulation Setup and Execution

Leveraging Machine-Learning Force Fields (MLFFs) for Improved Accuracy and Stability

Machine Learning Force Fields (MLFFs) have emerged as a transformative tool for molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, offering near-quantum mechanical accuracy at a fraction of the computational cost. However, their adoption in production and research environments is hampered by a critical challenge: simulation instability. Despite achieving low test errors on standard benchmarks, MLFFs are known to produce unstable simulations that can irreversibly drift into unphysical regions of phase space, leading to unrealistic bond breaking, simulation collapse, and inaccurate estimation of system observables. This technical support guide addresses the core issues surrounding MLFF stability and accuracy, providing researchers with practical troubleshooting methodologies to enhance the reliability of their computational experiments.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ 1: Why do my MLFF simulations become unstable even with low force and energy test errors?

Root Cause: There is a documented weak correlation between conventional error metrics (force/energy MAE) and simulation stability. MLFFs can exhibit excellent performance on test datasets but perform poorly in extended MD simulations due to distributional shift and error accumulation over time.

Troubleshooting Steps:

- Implement Stability-Aware Training: Adopt the StABlE (Stability-Aware Boltzmann Estimator) training procedure. This method uses parallel MD simulations to actively seek out unstable regions during training and corrects them using reference system observables, without requiring additional quantum-mechanical calculations [27] [28].

- Utilize Equivariant Architectures: Transition from invariant models to equivariant architectures like SO3krates. These models use directional information (spherical harmonics) which improves data efficiency, reduces error distribution spread, and enhances robustness to cumulative inaccuracies during simulation [29].

- Expand Phase Space Coverage: Use active learning or similar approaches to ensure your training data covers a broader region of the potential energy surface (PES), including high-energy configurations that might be encountered during long simulations [27].

FAQ 2: How can I improve the transferability and data efficiency of my MLFF model?

Root Cause: Models trained solely on limited data from narrow regions of chemical or conformational space often fail to generalize to unseen molecular structures or different thermodynamic conditions.

Troubleshooting Steps:

- Leverage Multi-Modal Training: Incorporate supervision from both reference quantum-mechanical calculations and system observables (e.g., radial distribution functions, virial stress). This provides a richer learning signal, especially valuable when large QM datasets are unavailable [27] [28].

- Benchmark Beyond MAE: Move beyond mean absolute error on forces and energies. Introduce new benchmarks that directly assess the model's performance on relevant physical observables and its stability during MD runs [30].

- Architecture Selection: Choose modern equivariant graph neural networks (GNNs) which have demonstrated better generalization and data efficiency compared to invariant models due to their ability to capture more complex, transferable interaction patterns [29].

FAQ 3: What are the practical steps to implement a stability-aware training workflow?

Solution: The following workflow, based on the StABlE training methodology, can be integrated into existing MLFF development pipelines.

FAQ 4: How do I select the right MLFF architecture for my system?

Solution: The choice of architecture involves a trade-off between accuracy, speed, and stability. The table below compares key architectural types.

| Architecture Type | Key Feature | Advantages | Stability Consideration | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Invariant MPNNs [29] | Uses only invariant inputs (e.g., interatomic distances). | Fast computation. | Can struggle with complex, flexible systems; may lack transferability. | Small, rigid organic molecules. |

| Equivariant MPNNs (e.g., NequIP) [27] [29] | Uses equivariant features (spherical harmonics) for directional information. | High accuracy, better data efficiency, improved stability. | Computationally expensive due to tensor products. | High-accuracy studies of peptides, condensed phases. |

| Efficient Equivariant Models (e.g., SO3krates) [29] | Replaces tensor products with Euclidean self-attention. | Unique combo of high accuracy, stability, and speed (~30x faster). | Requires implementation of a newer architecture. | Large-scale systems (e.g., supra-molecular structures), extended MD, PES exploration. |

This section details key computational "reagents" and methodologies essential for developing stable and accurate MLFFs.

Table 1: Key MLFF Architectures and Benchmarking Tools

| Name | Type / Category | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| SchNet [27] | Invariant Graph Neural Network | Learns atomic interactions using continuous-filter convolutions. | Base model for organic molecules; often used in comparative studies. |

| NequIP [27] | Equivariant Message Passing NN | High-accuracy model using SO(3) equivariance via tensor products. | Accurate force fields for materials and molecules; used in StABlE training tests. |

| GemNet-T [27] | Invariant Graph Neural Network | Models many-body interactions explicitly with triplets of atoms. | Complex systems like liquid water; benchmark for condensed phases. |

| SO3krates [29] | Efficient Equivariant Transformer | Uses Euclidean self-attention to avoid costly tensor products. | Fast, stable MD for large, flexible systems (peptides, supra-molecules). |

| StABlE Training [27] [28] | Training Procedure / Algorithm | Multi-modal training for stability using observables and QM data. | Correcting simulation instabilities without extra QM calculations. |

| Differentiable Boltzmann Estimator [27] | Computational Kernel | Enables gradient-based learning through MD simulations. | Core component of StABlE training for efficient end-to-end optimization. |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol 1: Stability-Aware Boltzmann Estimator (StABlE) Training

Purpose: To train an MLFF that is inherently stable for MD simulations by jointly using QM data and system observables [27] [28].

Detailed Methodology:

- Initialization: Pre-train an MLFF model (e.g., SchNet, NequIP) on a dataset of ab-initio calculated energies and forces.

- Parallel MD Exploration: Run a large number (e.g., hundreds) of independent, short MD simulations in parallel using the current MLFF at the target thermodynamic state (e.g., NVT ensemble at 300 K).

- Instability Detection: Monitor these simulations for signatures of instability, such as:

- Unphysical bond stretching or breaking.

- Irreversible drift in system energy.

- Deviation from reference observables (e.g., radial distribution function).

- Boltzmann Estimator Correction: For identified unstable configurations, compute the gradient of the loss function with respect to the model parameters. The loss function penalizes differences between the MLFF-predicted and reference observables. This is achieved efficiently without backpropagating through the entire MD simulation.

- Model Update: Update the MLFF parameters using gradients from both the conventional QM loss and the new stability-aware observable loss.

- Iteration: Repeat steps 2-5 until the model produces stable simulations and accurately reproduces the reference observables.

Expected Outcome: The final MLFF model will exhibit significantly improved stability in long-time MD simulations, more accurate observable prediction, and better generalization to unseen simulation temperatures [27].

Protocol 2: Benchmarking MLFF Stability and Transferability

Purpose: To quantitatively evaluate the performance of an MLFF beyond standard force/energy errors [30] [29].

Detailed Methodology:

- Long-Timescale MD Test: Run a microsecond-scale MD simulation and monitor for simulation collapse (e.g., atom flying away) or unphysical structural changes.

- Observable Comparison: Calculate key system observables from a stable trajectory and compare against experimental data or high-level reference calculations. Critical observables include:

- Radial distribution function (RDF)

- Virial stress tensor

- Diffusion coefficient

- Velocity auto-correlation function

- Extrapolation Test: Run simulations at temperatures not included in the training set. Monitor for rapid degradation in stability or observable accuracy.

- Conformational Exploration: For biomolecules, use a minima hopping algorithm to explore thousands of minima on the potential energy surface. A good MLFF should discover physically valid minima not present in the training data without becoming unstable [29].

The relationship between these benchmarking steps is summarized in the following workflow:

Achieving stability and accuracy in MLFFs requires a paradigm shift from merely minimizing force and energy errors on static datasets to actively designing models and training procedures for robust performance in dynamic simulations. By adopting equivariant architectures, implementing stability-aware training methodologies like StABlE, and employing rigorous stability-centric benchmarking, researchers can significantly enhance the reliability of their MLFFs. This enables the application of these powerful models to long-timescale phenomena, rare events, and the exploration of complex molecular systems with greater confidence, ultimately accelerating discovery in drug development and materials science.

FAQs: Understanding Pre-Training for MLIPs

1. What is the core problem that pre-training aims to solve for Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations? Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials (MLIPs) often demonstrate high accuracy on data similar to their training set (in-distribution) but can fail catastrophically when simulations sample new, unexplored regions of the Potential Energy Surface (PES). These failures manifest as "holes" in the PES where the model predicts unphysically low energies for unrealistic atomic configurations, leading to simulation crashes or nonsensical results. Pre-training on large, diverse datasets is a strategy to condition the model on a wider range of atomic environments, thereby smoothing the PES and improving robustness for out-of-distribution samples [31] [32].

2. How does pre-training on a dataset like OC20 improve simulation stability? Pre-training on large-scale datasets like OC20, which contains millions of data frames across many elements, teaches the model a more general representation of atomic interactions. A model pre-trained on OC20 and fine-tuned on a specific target system was shown to sustain simulation trajectories up to three times longer than a model trained from scratch, despite both models achieving similar low force errors. This indicates that pre-training provides a better foundational understanding of molecular interactions that goes beyond what standard accuracy metrics can capture [32] [33].

3. My MLIP has a low Force Mean Absolute Error (MAE), but my simulations are unstable. Why? Force MAE, while a common benchmark, is not always a sufficient metric for predicting MD simulation stability. A model can achieve a low force MAE on a specific test set but still be prone to failure when it encounters unfamiliar atomic configurations during a long simulation trajectory. Pre-training addresses this by ensuring the model has reasonable "limiting behaviors" across a broader energy landscape, not just high accuracy in the most probable regions [32].

4. What are the practical benefits of a pre-training and fine-tuning workflow? The primary benefit is data efficiency. For example, the DPA-1 model, when pre-trained on single-element and binary alloy data, required 90% fewer ternary samples to achieve good performance on an AlMgCu alloy system compared to a model trained from scratch. This drastically reduces the need for expensive, high-quality ab initio calculations for new downstream tasks [33].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Unstable MD Trajectories with MLIPs

Symptoms: Simulations crash with errors like atoms flying apart (unphysically large distances) or crashing into each other (unphysically small distances) [31].

Diagnosis and Solutions:

| Step | Action | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Verify PES Smoothness | The root cause is often an under-explored PES. Check if your training data comprehensively covers both low-energy and high-energy regions. |

| 2 | Implement a Pre-Training Strategy | Instead of training from scratch, pre-train your model on a large, diverse dataset (e.g., OC20). This provides a physically reasonable baseline for the entire PES [32] [33]. |

| 3 | Fine-Tune on Target Data | Follow pre-training with fine-tuning on a smaller set of high-quality ab initio data specific to your system of interest. This combines broad general knowledge with specific task accuracy [31]. |

| 4 | Use Robust Architectures | Choose model architectures like DPA-1 or GemNet-T that are designed for this paradigm and produce conservative forces, which are essential for accurate dynamics [33]. |

Issue 2: Poor Convergence and Transfer Learning

Symptoms: The fine-tuned model performs poorly on the target system, showing high errors even after pre-training.

Diagnosis and Solutions:

| Step | Action | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Check Dataset Compatibility | Ensure the chemical and conformational space of your pre-training data has a reasonable overlap with your target system. |

| 2 | Inspect Type Embeddings | In models like DPA-1, the learned embeddings for different elements should form a meaningful structure (e.g., a spiral corresponding to the periodic table). This indicates the model has learned chemically meaningful representations [33]. |

| 3 | Adjust Fine-Tuning Parameters | Use a lower learning rate for fine-tuning than for pre-training. Consider "freezing" the early layers of the network that capture general features and only fine-tuning the top layers. |

| 4 | Validate with Simple Properties | Before running long MD, verify the model on simple properties like energy differences between known isomers or lattice constants to ensure basic correctness. |

Data Presentation: Quantitative Evidence for Pre-Training

Table 1: Impact of Pre-Training on Simulation Performance and Data Efficiency

| Model / Strategy | Key Metric | Result | Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| GemNet-T (Pre-trained on OC20) [32] | Simulation Trajectory Length | 3x longer than model trained from scratch | Markedly improved stability for MD runs. |

| DPA-1 (Pre-trained on single/binary data) [33] | Ternary Data Samples Required | ~90% reduction vs. training from scratch | High data efficiency for complex multi-component systems. |

| Force Field Pre-Training (FFPT) [31] | Coverage of PES | Correct limiting behaviors for high-energy states | Prevents atom "crashing" and "flying apart" during simulation. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Force Field Pre-Training (FFPT) and Fine-Tuning

This protocol uses cheap, classical force fields to pre-train the model, followed by fine-tuning on high-quality ab initio data [31].

Dataset Generation (Pre-Training):

- Method: Use "rattling" to generate a large set of diverse molecular structures. This involves creating random atomic displacements to sample high-energy, unphysical conformations that are rarely visited in standard MD runs.

- Labeling: Calculate energies and forces for these structures using a classical, non-reactive force field. This data is computationally inexpensive to generate.

- Goal: Create a dataset that broadly and smoothly covers the potential energy surface.

Pre-Training:

- Train the MLIP from scratch on the force field-labeled dataset. The objective is not chemical accuracy, but to learn a smooth PES with physically reasonable behavior at its extremes.

Dataset Generation (Fine-Tuning):

- Method: Use standard ab initio molecular dynamics (AIMD) or targeted sampling to gather a smaller set of configurations in the chemically relevant regions (e.g., equilibrium states, transition states).

- Labeling: Calculate energies and forces for these structures using high-level ab initio methods (e.g., DFT).

Fine-Tuning:

- Initialize the MLIP with the weights from the pre-trained model.

- Continue training using only the high-quality ab initio dataset. This stage specializes the model for chemical accuracy in the relevant regions of the PES.

The following workflow diagram illustrates this two-stage process:

Protocol 2: Fine-Tuning a Model Pre-trained on OC20

This protocol leverages a model already pre-trained on a massive, general dataset [32] [33].

- Acquire a Pre-trained Model: Obtain a model like DPA-1 or GemNet-T that has been pre-trained on the OC20 dataset or a similar large-scale corpus.

- Prepare Target System Data:

- Run a short AIMD simulation or use other sampling methods for your specific system.

- Perform ab initio calculations to generate a dataset of energies and forces. A few thousand frames may be sufficient.

- Fine-Tuning Execution:

- Use the target system dataset to continue training the pre-trained model.

- Employ a reduced learning rate (e.g., 1/10th of the pre-training learning rate) to avoid catastrophic forgetting.

- Monitor loss on a validation set from your target system to prevent overfitting.

- Validation:

- Run MD simulations and check for stability.

- Compute key thermodynamic or dynamic properties (e.g., radial distribution functions, diffusion coefficients) and compare against benchmark ab initio or experimental data if available.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 2: Essential Components for Pre-Training MLIPs

| Item | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Large-Scale Datasets | Provides diverse examples of atomic environments for foundational model training. | OC20/OC2M dataset [33] with 56 elements for general-purpose pre-training. |

| Pre-Trained Model Architectures | Graph neural networks designed for molecular systems that respect physical symmetries. | DPA-1 [33] (uses attention), GemNet-T [32] (equivariant GNN). |

| Classical Force Fields | Source of cheap, plentiful data for initial pre-training to ensure PES smoothness [31]. | Non-reactive FFs for organic molecules; used in the FFPT-FT strategy. |

| Ab Initio Data | Source of high-quality, accurate labels for the fine-tuning stage on a specific system. | DFT calculations on target molecular systems to achieve chemical accuracy. |

| Active Learning Protocols | For intelligently expanding training data by querying uncertain regions of the PES. | DP-GEN [33] for building compact, high-quality datasets for fine-tuning. |

Fundamental Concepts & FAQs

This section addresses frequently asked questions about the core principles of Gaussian Accelerated Molecular Dynamics (GaMD), accelerated Molecular Dynamics (aMD), and Metadynamics, providing a foundational understanding for researchers.

Q1: What is the primary functional difference between GaMD, aMD, and Metadynamics in how they enhance sampling?

A: These methods differ primarily in how they apply bias to the system's potential energy to facilitate barrier crossing.

- GaMD adds a harmonic boost potential when the system potential is below a threshold energy. This boost smoothens the potential energy landscape by filling low-energy wells [34].

- aMD also applies a boost potential to the system but uses a different formulation. It raises the entire potential energy surface in regions where the energy is below a specified threshold, making energy barriers relatively lower and easier to cross.

- Metadynamics actively discourages the system from revisiting previously sampled states by adding repulsive Gaussian potentials along pre-defined Collective Variables (CVs). Over time, this fills the free energy minima, allowing the system to explore new regions [35].

Q2: I need to directly obtain kinetic properties like transition rates from my simulation. Which method should I choose?

A: Among these three, standard GaMD, aMD, and Metadynamics alter the system's true kinetics, making it difficult to directly extract kinetic properties [34]. However, a hybrid approach like GaMD-WE, which combines GaMD with the Weighted Ensemble (WE) method, is designed for this purpose. In GaMD-WE, GaMD is first used to efficiently sample the thermodynamic landscape. Subsequently, WE, which runs many weighted trajectories in parallel, is used to obtain accurate kinetics and pathways [34].

Q3: Why is reweighting a critical step in GaMD and Metadynamics, and how is it achieved?

A: Reweighting is the process of recovering the original, unbiased Boltzmann distribution and free-energy landscape from the biased simulation data.

- In GaMD, reweighting is typically performed using the cumulant expansion method. The anharmonicity of the boost potential is assumed to be small, allowing the exponential average term ⟨eβΔV(r)⟩ to be approximated to the second order for reweighting [34].

- In Metadynamics, the free-energy surface is recovered as the negative sum of the deposited Gaussian hills. As the simulation converges, the bias potential flattens, providing an estimate of the underlying free energy [35].

Q4: When are Collective Variables (CVs) required, and what are the challenges associated with them?

A: CVs are required for Metadynamics but not for standard GaMD or aMD [34] [35].

- Metadynamics relies on CVs to guide the sampling. These are a small number of descriptors (e.g., distances, angles, root-mean-square deviation) that are thought to capture the slow, relevant motions of the system.

- The challenge is that identifying optimal CVs for a new system can be difficult and often requires prior knowledge or trial and error. Poorly chosen CVs can lead to inefficient or incorrect sampling [35] [36]. GaMD's advantage is its ability to perform enhanced sampling without predefined CVs, making it easier to apply to unfamiliar systems [34].

Troubleshooting Common Errors

This guide helps diagnose and resolve frequent issues encountered during simulations.

Table 1: Common Simulation Errors and Solutions

| Error / Symptom | Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|---|