Benchmarking Force Fields for Atomic Motion: A Practical Guide for Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on evaluating the accuracy of force fields in simulating atomic motion.

Benchmarking Force Fields for Atomic Motion: A Practical Guide for Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on evaluating the accuracy of force fields in simulating atomic motion. It covers foundational principles of universal potential energy surfaces and key force field types, practical methodologies for benchmarking using modern platforms like LAMBench and CHIPS-FF, strategies for troubleshooting common optimization and stability issues, and rigorous validation techniques for comparative analysis across scientific domains. By synthesizing insights from cutting-edge benchmarking studies, this resource aims to empower scientists in selecting and optimizing force fields for reliable biomolecular simulations, ultimately enhancing the predictive power of computational methods in drug discovery and materials design.

Understanding Force Field Fundamentals: From Universal Potentials to Domain-Specific Applications

The accurate modeling of a system's potential energy surface (PES)—which represents the total energy as a function of atomic coordinates—is a fundamental challenge in computational chemistry and materials science. The PES enables the exploration of material properties, reaction mechanisms, and dynamic evolution by providing access to energies and, through differentiation, the forces acting on atoms [1]. For decades, researchers have faced a stark trade-off: quantum mechanical methods like density functional theory (DFT) offer high accuracy but at prohibitive computational costs for large systems, while classical force fields provide efficiency but often lack the accuracy and transferability for studying chemical reactions [2] [1] [3].

The concept of a Universal Potential Energy Surface (UPES), a single model capable of providing quantum-level accuracy across the entire periodic table and diverse structural dimensionalities, has thus emerged as a paramount goal. The recent advent of universal machine learning interatomic potentials (UMLIPs) has been heralded as a transformative step toward this goal, promising to combine the accuracy of quantum mechanics with the speed of classical force fields [4] [3]. This guide objectively benchmarks the current state of these universal models, framing the discussion within the critical context of force field accuracy research for atomic motion.

Theoretical Foundations of Force Fields

A Hierarchy of Approximations

The methods for constructing a PES form a hierarchy, categorized primarily by their functional form and the source of their parameters. They can be broadly classified into three groups [1]:

- Classical Force Fields: These use simplified physics-based potential functions (e.g., harmonic bonds, Lennard-Jones potentials) to calculate a system's energy. They are highly efficient and interpretable but are generally incapable of modeling bond formation and breaking, as their fixed bonding terms preclude chemical reactions [1] [5].

- Reactive Force Fields (e.g., ReaxFF): Designed to simulate chemical reactions, these force fields introduce bond-order formalism, allowing for dynamic bond formation and breaking. While more versatile than classical force fields, they often struggle to achieve DFT-level accuracy across diverse systems [6].

- Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials (MLIPs): This newest class uses machine learning to map atomic configurations directly to energies and forces. MLIPs do not rely on pre-defined functional forms but learn the underlying quantum mechanical relationships from reference data, allowing them to approach quantum accuracy at a fraction of the computational cost [6] [3].

Table 1: Comparison of Primary Force Field Types for PES Construction.

| Force Field Type | Number of Parameters | Parameter Interpretability | Ability to Model Reactions | Typical Computational Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classical | 10 - 100 | High (Physical terms) | No | Very Low |

| Reactive (ReaxFF) | 100 - 1,000 | Medium (Semi-empirical) | Yes | Low to Medium |

| Machine Learning (MLIP) | 100,000 - 10s of Millions | Low (Black-box) | Yes | Medium (Inference) |

The Rise of Universal MLIPs

Traditional MLIPs are trained on a narrow domain of chemical space for a specific application. UMLIPs represent a paradigm shift. They are pre-trained on massive, diverse datasets encompassing millions of atomic configurations from molecules to crystalline materials, enabling them to make predictions across vast swathes of chemistry without system-specific retraining [4] [3]. Key enabling developments include:

- Large-Scale Datasets: Initiatives like Meta's Open Molecules 2025 (OMol25), comprising over 100 million quantum chemical calculations, provide the comprehensive data needed for training robust UMLIPs [7]. Other critical datasets include the Materials Project (MPtrj), Alexandria (Alex), and OC22 [8].

- Advanced Architectures: Modern UMLIPs employ sophisticated neural network architectures that incorporate physical constraints. Key models include eSEN (equivariant Smooth Energy Network), EquiformerV2, MACE, and Orb, which ensure predictions are invariant to translation, rotation, and atom indexing [7] [4] [3].

- Conservative vs. Direct Forces: A critical architectural distinction lies in how forces are predicted. Conservative models compute forces as the analytical gradient of the energy, guaranteeing energy conservation and are more reliable for molecular dynamics. Direct-force models predict forces directly, which can be faster but may lead to non-conservative artifacts [7] [4].

Benchmarking Methodologies for UMLIPs

Evaluating the performance of UMLIPs requires a multi-faceted approach that moves beyond simple energy and force errors on standardized quantum chemistry datasets.

Computational Accuracy Across Dimensionality

A true UPES must perform consistently across all structural dimensionalities, from 0D molecules to 3D bulk materials. A 2025 benchmark evaluated 11 UMLIPs on a consistent dataset to test this [4]. The core protocol involves:

- Model Selection: Selecting a range of state-of-the-art UMLIPs (e.g., eSEN, Orb, MACE, MatterSim).

- Test Set Creation: Constructing a benchmark set containing matched 0D (molecules, clusters), 1D (nanowires), 2D (monolayers, slabs), and 3D (bulk crystals) structures, all computed at the same level of DFT theory to avoid functional-driven discrepancies.

- Property Calculation: For each structure in the test set, using the UMLIP to predict the equilibrium geometry and its energy.

- Error Analysis: Quantifying errors by comparing UMLIP predictions to reference DFT values, typically using metrics like the root mean square error (RMSE) in energy per atom and in atomic positions.

This benchmark reveals a common trend: many UMLIPs exhibit degrading accuracy as dimensionality decreases, with errors highest for 0D molecular systems. However, the top-performing models, such as eSEN and Orb-v2, can achieve average errors in atomic positions below 0.02 Å and energy errors below 10 meV/atom across all dimensionalities [4].

Experimental Validation: The Ultimate Test

Computational benchmarks can create a circularity where models are evaluated on data similar to their training sources. The UniFFBench framework, introduced in 2025, addresses this by validating UMLIPs against a curated dataset of approximately 1,500 experimentally characterized mineral structures (MinX) [8]. The experimental workflow probes practical applicability:

- Dataset Curation: The MinX dataset is organized into subsets to test different aspects: MinX-EQ (ambient conditions), MinX-HTP (high temperature/pressure), MinX-POcc (compositional disorder), and MinX-EM (elastic properties).

- Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations: Running finite-temperature MD simulations on the mineral structures using each UMLIP.

- Property Comparison: Measuring key experimentally accessible properties from the simulations, including:

- Density and Lattice Parameters: Comparing against X-ray diffraction data.

- Radial Distribution Functions: Assessing local atomic structure.

- Elastic Tensors: Deriving mechanical properties from stress-strain relationships.

- Stability Assessment: Recording simulation failure rates, which can occur due to unphysical forces or memory overflows from unstable structures.

This experimental grounding reveals a significant "reality gap". Models with excellent computational benchmark performance can fail dramatically when confronted with experimental complexity, exhibiting high simulation failure rates and property errors that exceed thresholds required for practical application [8].

Table 2: Key UMLIPs and Their Characteristics (as of 2025).

| Model Name | Key Architecture | Training Dataset Size | Notable Strengths / Weaknesses |

|---|---|---|---|

| eSEN [7] [4] | Equivariant Transformer | ~113 Million Frames | High accuracy across dimensionalities; conservative forces. |

| Orb-v2/v3 [4] [8] | Orbital Attention | ~32-133 Million Frames | Top-tier stability and accuracy on experimental benchmarks. |

| MACE [4] [8] | Atomic Cluster Expansion | ~12 Million Frames | Strong performance, efficient. |

| MatterSim [4] [8] | Graph Neural Network | ~17 Million Frames | High simulation stability on minerals. |

| CHGNet [8] | GNN with Charge Features | Not Specified | Prone to high simulation failure rates on complex solids. |

| M3GNet [4] [8] | Graph Neural Network | ~0.19 Million Frames | An early UMLIP; lower performance than newer models. |

Practical Limitations and Research Challenges

Despite their promise, current UMLIPs face several critical limitations that preclude the realization of a truly universal PES.

- The Experimental Reality Gap: As identified by UniFFBench, even the best UMLIPs struggle to predict properties like density within the 2% error margin required for many practical applications. This gap is attributed to biases in training data (e.g., overrepresentation of certain elements and 3D crystals) and the inherent limitations of DFT reference data itself, which may not perfectly match experimental observations [2] [8].

- Handling of Long-Range Interactions: Electrostatic and van der Waals interactions are critical in many systems, such as biomolecules and semiconductors. Standard UMLIPs, which have a localized receptive field, often fail to describe these interactions accurately, limiting their application to polarizable systems and interfaces [9] [3].

- Data Efficiency and Specialization: Training a UMLIP from scratch requires immense computational resources, limiting development to well-funded organizations. Consequently, a growing trend involves fine-tuning large pre-trained UMLIPs on smaller, application-specific datasets, which can be a more resource-efficient path to high accuracy for specialized tasks [7] [6].

- Transferability Across Electronic States: Standard UMLIPs are typically ground-state models. They cannot handle changes in electronic states, such as those occurring in excited-state dynamics or in magnetic materials with different spin orderings, without significant architectural modifications [3].

For researchers embarking on using or developing UMLIPs, a suite of resources and tools is available.

- Pre-trained Models: Most state-of-the-art UMLIPs (e.g., eSEN, MACE, Orb) are available on platforms like Hugging Face and are integrated into software like ASE and LAMMPS for running simulations [7] [3].

- Training Datasets: Large-scale datasets such as OMol25 (biomolecules, electrolytes), the Materials Project (crystalline solids), and SPICE (organic molecules) serve as the foundation for training and fine-tuning [7] [4].

- Specialized Software: Tools like DPmoire are emerging to automate the construction of accurate MLIPs for specific challenging systems like twisted moiré materials, which are poorly represented in universal training sets [9].

- Benchmarking Frameworks: UniFFBench and the multidimensional benchmark [4] [8] provide standardized protocols for evaluating model performance against both computational and experimental targets, which is crucial for assessing real-world utility.

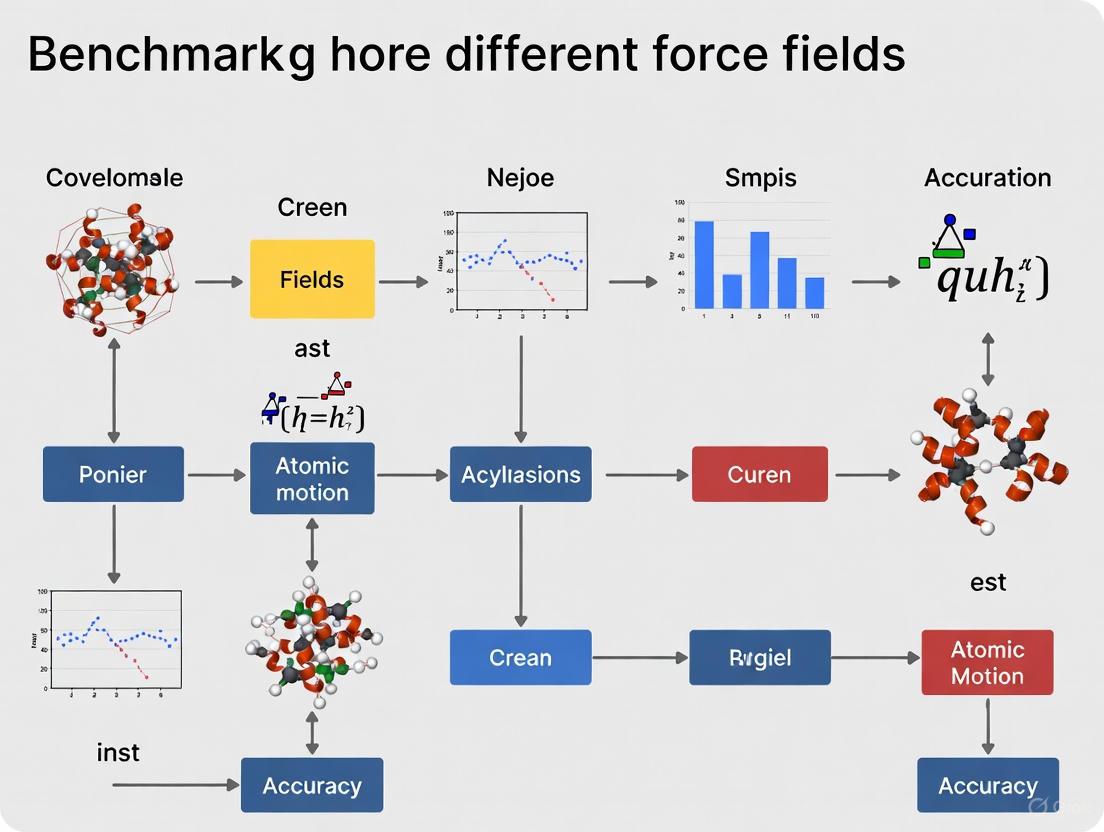

Diagram 1: A standardized workflow for benchmarking Universal Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials (UMLIPs), highlighting the two primary validation pathways against computational (DFT) and experimental data.

The quest for a Universal Potential Energy Surface has entered an exhilarating new phase, driven by the development of large-scale UMLIPs. These models demonstrate remarkable performance, often matching DFT accuracy for a wide range of systems at a fraction of the computational cost, and are beginning to enable the simulation of complex, multi-dimensional systems [7] [4].

However, this guide's benchmarking analysis underscores that the goal has not yet been fully realized. Significant practical limitations remain, most notably the "reality gap" identified through rigorous experimental validation [8]. The accuracy of a UMLIP is intrinsically tied to the quality, breadth, and physical fidelity of its training data. Future progress will likely depend on strategies that fuse computational and experimental data during training [2], improve the description of long-range interactions [3], and develop more efficient fine-tuning protocols. For now, researchers should select UMLIPs with a clear understanding of their strengths and weaknesses, always validating model predictions against domain-specific knowledge or experiments to ensure reliability.

The accurate simulation of atomic motion is foundational to advancements in materials science, chemistry, and drug development. The fidelity of these simulations hinges on the quality of the interatomic potential, or force field, which approximates the potential energy surface (PES) of a system. Traditionally, the field has been dominated by classical force fields, which use fixed mathematical forms to describe interactions but cannot model chemical reactions. The development of reactive force fields (ReaxFF) bridged this gap by introducing a bond-order formalism, enabling the simulation of bond formation and breaking. Most recently, machine learning potentials (MLPs) have emerged, leveraging data from quantum mechanical calculations to achieve near-quantum accuracy at a fraction of the computational cost. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these three paradigms—Classical, Reactive (ReaxFF), and Machine Learning Potentials—framed within the context of benchmarking their performance for atomic motion accuracy research. We summarize key quantitative data, detail experimental protocols from foundational studies, and provide visualizations to aid researchers in selecting the appropriate tool for their scientific inquiries.

Force Field Classification and Theoretical Foundations

Classical Force Fields

Classical force fields (or empirical potentials) use pre-defined analytical functions to describe the potential energy of a system based on atomic positions. The total energy is typically decomposed into bonded and non-bonded terms, with the functional form remaining fixed regardless of the chemical environment [10] [11]. For example, the total energy in a classical force field might be expressed as a sum of bond stretching, angle bending, torsion, and non-bonded interactions (van der Waals and electrostatics). Their primary advantage is computational efficiency, allowing for simulations of millions of atoms over micro- to millisecond timescales. However, their fixed bonding topology prevents them from simulating chemical reactions, and their parameterization is often not transferable beyond the specific systems for which they were developed [12] [11].

Reactive Force Fields (ReaxFF)

ReaxFF was developed to overcome the limitation of fixed connectivity in classical force fields. It employs a bond-order formalism, where the bond order between atoms is empirically calculated from interatomic distances and is updated continuously throughout the simulation [12]. This allows bonds to form and break organically. The total energy in ReaxFF includes bond-order-dependent terms (e.g., bond energy, angle strain, torsion) and bond-order-independent terms (e.g., van der Waals, Coulomb interactions) [13] [12]. A key feature is its use of a charge equilibration (QEq) method at each step to handle electrostatic interactions dynamically. While ReaxFF is more computationally expensive than classical potentials, it is significantly cheaper than quantum mechanics (QM), providing a powerful compromise for simulating reactive processes in complex, multi-phase systems [12].

Machine Learning Potentials

Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials (MLPs or ML-IAPs) represent a paradigm shift. They are data-driven models trained on high-fidelity QM data to learn the mapping from atomic configurations to energies and forces [14]. Unlike classical or ReaxFF, MLPs do not rely on a pre-conceived functional form. Instead, they use flexible architectures like neural networks to directly approximate the PES. Modern MLPs, such as NequIP, Allegro, and MACE, are geometrically equivariant, meaning they explicitly build in physical symmetries like rotation and translation invariance, leading to superior data efficiency and accuracy [15] [14]. They act as surrogates for density functional theory (DFT), offering near-ab initio accuracy while being orders of magnitude faster, thus enabling large-scale molecular dynamics (MD) simulations previously inaccessible to QM methods [15] [16] [14].

The diagram below illustrates the logical relationship and key differentiators between these three classes of force fields.

Comparative Performance Analysis

The choice between force field types involves a trade-off between accuracy, computational cost, and applicability. The following tables provide a consolidated summary of these key performance metrics, drawing from recent benchmarking studies and application papers.

Table 1: Comparison of fundamental characteristics and benchmark performance.

| Feature | Classical Force Fields | Reactive Force Fields (ReaxFF) | Machine Learning Potentials |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Approach | Pre-defined analytical functions [10] | Bond-order formalism [12] | Data-driven model trained on QM data [14] |

| Reactivity | No (fixed bonds) | Yes (dynamic bonds) | Yes, if trained on reactive data [14] |

| Typical Computational Cost | Lowest [10] | Moderate (10-100x classical) [12] | Variable (can be GPU-accelerated); higher than classical but much lower than QM [15] |

| Parameterization | Empirical fitting to experimental/QM data [10] | Trained on extensive QM training sets [13] [12] | Trained on QM datasets (e.g., DFT) [14] |

| Benchmark Accuracy (Forces) | Varies by system; can be poor for defects [10] | Good for trained systems; ~20-50 meV/Å error reported [12] | Highest; can achieve ~1-20 meV/Å error on tested systems [15] [14] |

| Transferability | Low; system-specific | Moderate within trained domain (e.g., combustion branch) [13] | High, but depends on training data diversity [16] |

| Key Benchmarking Study | Graphene fracture toughness [10] | Validation against QM reaction barriers [13] [12] | LAMBench; MLIP-Arena [15] [16] |

Table 2: Performance in specific application domains and system examples.

| Application Domain | Classical Force Fields | Reactive Force Fields (ReaxFF) | Machine Learning Potentials |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carbon Materials (Graphene) | REBO/Tersoff: Good for pristine lattice; AIREBO-m: Recommended for cracks [10] | CHO.ff: For hydrocarbon oxidation [13] | MLIPs show high accuracy but were not benchmarked in the provided study [10] |

| High-Energy Materials | Not suitable for decomposition | HE.ff, HE2.ff: Designed for RDX, TATB explosives [13] | Not specifically mentioned in results |

| Aqueous Systems & Catalysis | Limited by lack of reactivity | CuCl-H2O.ff, FeOCHCl.ff: For aqueous chemistry [13] | MACE, NequIP: High accuracy for Si-O systems [15] |

| General Molecules/Materials | Good for stable, non-reactive systems | HCONSB.ff: For complex compositions (H/C/O/N/S/B) [13] | MACE, Allegro, NequIP lead in accuracy for Al-Cu-Zr, Si-O [15] |

| Primary Limitation | Cannot model bond breaking/formation | Accuracy depends on parameter set; system-specific terms [13] [12] | Data fidelity and quantity; computational cost for large models [16] [14] |

Experimental Protocols for Force Field Benchmarking

Benchmarking Classical Potentials for Graphene Mechanics

A rigorous assessment of classical potentials for graphene provides a clear protocol for evaluating mechanical properties [10].

- System Preparation: A pristine graphene sheet with dimensions of approximately 5.11 nm x 5.16 nm (1008 atoms) is constructed. A separate model with a pre-existing crack is created to study fracture toughness.

- Simulation Setup: Energy minimization is performed first to find a stable configuration. The system is then equilibrated at 300 K and 0 GPa pressure using the NPT ensemble.

- Mechanical Test: A uniaxial tensile test is conducted in the zigzag direction with a constant engineering strain rate of 0.001 per picosecond. The simulation continues until material failure.

- Data Collection & Benchmarking: The stress-strain relationship is recorded throughout the test. Key metrics like Young’s modulus, ultimate strength, and failure strain are extracted. The results from 15 different potentials (e.g., Tersoff, REBO, AIREBO-m) are compared against each other and available experimental data to determine the most accurate potential for a given application (e.g., pristine vs. defective graphene) [10].

Benchmarking Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials

The LAMBench framework and other studies provide standardized methodologies for evaluating MLPs [15] [16].

- Training Protocol: Models are trained on diverse datasets such as MD17 (molecular dynamics trajectories of small organic molecules) or materials-specific datasets like MPtrj. Training involves minimizing the loss function between predicted and DFT-calculated energies and forces.

- Accuracy Evaluation (Generalizability): The model's performance is evaluated on a held-out test set from the same distribution (in-distribution) and on datasets of different materials or phases (out-of-distribution). The primary metrics are Mean Absolute Error (MAE) for energy (meV/atom) and forces (meV/Å) [16].

- Performance & Applicability Tests: The computational speed (simulated time per day) is measured and compared across different hardware (CPUs vs. GPUs). For applicability, the model's stability is tested in extended molecular dynamics simulations, checking for unphysical energy drift or structural collapse [15] [16]. The model's ability to predict other properties, such as phonon spectra or elastic constants, is also a key benchmark.

Table 3: Key software, datasets, and resources for force field research and application.

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function | Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|

| LAMMPS [10] | Software | A highly versatile and widely used open-source MD simulator. | Supports classical, ReaxFF, and many MLP implementations (e.g., through DeePMD-kit [14]). |

| DeePMD-kit [14] | Software | An open-source package for building and running Deep Potential MLPs. | Enables the application of DeePMD models for large-scale MD simulations with near-DFT accuracy. |

| ReaxFF (SCM/AMS) [13] | Software/Force Field | A commercial implementation of ReaxFF within the Amsterdam Modeling Suite. | Provides a user-friendly platform for ReaxFF simulations with a library of parameter sets (e.g., CHO.ff, AuCSOH.ff). |

| LAMBench [16] | Benchmarking Framework | An open-source benchmark system for evaluating Large Atomistic Models (LAMs). | Allows researchers to objectively compare the generalizability, adaptability, and applicability of different MLPs. |

| MPtrj Dataset [16] | Dataset | A large dataset of inorganic materials trajectories from the Materials Project. | Commonly used for pretraining and benchmarking domain-specific MLPs for materials science. |

| QM9 & MD17 [14] | Dataset | Standard benchmark datasets for small organic molecules and their MD trajectories. | Used for training and testing MLPs on molecular systems, predicting energies, forces, and properties. |

The taxonomy of modern force fields reveals a landscape of complementary tools, each with distinct strengths. Classical force fields remain the workhorse for large-scale, non-reactive simulations where computational efficiency is paramount. Reactive force fields (ReaxFF) provide a unique capability to model complex chemical reactions in multi-phase systems across extended scales, filling a crucial gap between classical and quantum methods. Machine learning potentials are rapidly advancing the frontier of accuracy, offering near-ab initio fidelity for large-scale molecular dynamics and showing exceptional performance in benchmark studies like LAMBench.

The future of force field development lies in addressing current limitations. For MLPs, this includes improving data efficiency, generalizability across chemical space, and model interpretability [14]. Multi-fidelity training that incorporates data from different levels of theory (e.g., various DFT functionals) is a promising path toward more universal potentials [16]. For all force field types, robust, community-driven benchmarking—as exemplified by LAMBench and detailed experimental protocols—is essential to guide users in selecting the right tool and to steer developers toward creating more powerful and reliable models for scientific discovery.

The accuracy of atomic motion simulations is foundational to advancements in drug design, materials discovery, and catalyst development. Force fields (FFs)—the mathematical models that describe interatomic potentials—must be meticulously benchmarked to ensure they reproduce physically meaningful behavior. Recent evaluations reveal a substantial performance gap between success on controlled computational benchmarks and reliability in real-world experimental scenarios [17]. This guide objectively compares modern force fields, focusing on machine learning force fields (MLFFs) and empirical FFs, by synthesizing current experimental data and benchmarking studies. It outlines domain-specific requirements, provides performance comparisons in structured tables, and details essential experimental protocols for researchers engaged in force field validation.

Force Field Types and Benchmarking Philosophy

A Spectrum of Force Fields

Modern simulations employ a hierarchy of force fields, each with distinct trade-offs between accuracy, computational cost, and domain applicability.

- Empirical Force Fields (e.g., OPLS-AA, CHARMM, AMBER): Use fixed, parameterized functional forms to represent bonded and non-bonded interactions. They are computationally efficient but can lack transferability, especially for systems far from their parameterization set [18].

- Machine Learning Force Fields (MLFFs) (e.g., MACE, eSEN, UMA): Trained on vast datasets of quantum mechanical calculations. They promise density functional theory (DFT)-level accuracy at a fraction of the computational cost, enabling simulations of large, complex systems that are prohibitively expensive for direct DFT [7] [19].

- Universal Machine Learning Force Fields (UMLFFs): A emerging class of MLFFs, such as Universal Models for Atoms (UMA) [7], trained across multiple datasets (molecules, materials, biomolecules) to achieve broad applicability across the periodic table.

The Critical Importance of Rigorous Benchmarking

Merely achieving low error on a training dataset is an insufficient measure of a force field's quality. A force field must reliably predict experimentally observable properties under realistic simulation conditions.

- The Reality Gap: Comprehensive frameworks like UniFFBench reveal that MLFFs with impressive performance on standard computational benchmarks often fail when confronted with the complexity of experimental measurements, such as the elastic properties of diverse mineral structures [17].

- Beyond Energy and Force Errors: True reliability is assessed through long molecular dynamics (MD) simulations that probe a force field's stability and its ability to reproduce experimental observables like radial distribution functions, free energy landscapes, and dynamical properties [20]. Non-conservative force fields, where forces are not derived from an energy gradient, can appear accurate in static tests but produce unstable MD trajectories [16].

- The Need for "Platinum Standards": In quantum-mechanical benchmarking, robust interaction energies for complex systems like ligand-pocket motifs are now being established by achieving tight agreement (e.g., 0.5 kcal/mol) between independent high-level methods like Coupled Cluster (CC) and Quantum Monte Carlo (QMC), forming a "platinum standard" for validation [21].

Domain-Specific Requirements and Performance

The optimal force field is highly dependent on the specific application domain, as each presents unique challenges and accuracy requirements.

Biomolecular Simulations

Biomolecular simulations, critical for drug discovery, require force fields that accurately model complex non-covalent interactions, protein folding, and ligand binding.

Table 1: Key Requirements and Performance for Biomolecular Simulations

| Requirement | Description | Key Benchmarking Observables | Representative Performance Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Native Structure Stability | Maintaining the correct folded "thumb-palm-fingers" fold of proteins over biologically relevant timescales. | - Root mean square deviation (RMSD) of backbone atoms.- Distance between catalytic residues (e.g., Cα(Cys111)-Cα(His272) in SARS-CoV-2 PLpro) [18]. | In benchmark studies of SARS-CoV-2 PLpro, OPLS-AA/TIP3P outperformed CHARMM and AMBER variants in longer simulations, better reproducing the catalytic domain folding and showing less unfolding of the N-terminal segment [18]. |

| Ligand-Binding Affinity | Accurately predicting the free energy of binding for small molecules to protein pockets. | - Binding free energy (ΔG).- Interaction energy (Eint) for model ligand-pocket systems [21]. | The QUID benchmark shows that even errors of 1 kcal/mol in Eint lead to erroneous binding affinity conclusions. While some dispersion-inclusive DFT methods are accurate, semi-empirical methods and force fields require improvement for non-equilibrium geometries [21]. |

| Solvent Model Fidelity | Correctly representing the impact of water and ions on protein structure and dynamics. | - Protein stability and fluctuation metrics with different water models (TIP3P, TIP4P, TIP5P) [18]. | The choice of water model significantly impacts performance. For SARS-CoV-2 PLpro, the OPLS-AA/TIP3P setup was identified as a top performer [18]. |

Materials Science Simulations

Simulations in materials science focus on predicting structural, mechanical, and electronic properties of bulk materials, surfaces, and defects.

Table 2: Key Requirements and Performance for Materials Simulations

| Requirement | Description | Key Benchmarking Observables | Representative Performance Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Elastic Property Prediction | Accurately calculating bulk modulus, shear modulus, and other mechanical properties. | - Elastic tensor components.- Density prediction error [17]. | In the UniFFBench evaluation against experimental mineral data, even the best UMLFFs exhibited density errors higher than the threshold required for practical applications, revealing a significant gap for materials property prediction [17]. |

| Phase Stability | Correctly identifying the stable crystal structure at a given temperature and pressure. | - Phonon spectra.- Phase transition temperatures and energies.- Defect formation energies [20]. | MLFFs like MACE and SO3krates have shown high accuracy in computing observables like phonon spectra when trained on relevant data, but performance is highly dependent on the training set's representativeness [20]. |

| Surface and Interface Modeling | Describing interactions at interfaces, such as between molecules and catalyst surfaces. | - Adsorption energy and geometry.- Trajectory stability and energy conservation at interfaces [20]. | Long-range noncovalent interactions at molecule-surface interfaces remain challenging for all MLFFs, requiring special caution in system selection and model validation [20]. |

Catalysis Simulations

Catalysis simulations require accurately modeling bond breaking/formation, transition states, and interactions at the complex interface between molecules, surfaces, and solvents.

Table 3: Key Requirements and Performance for Catalysis Simulations

| Requirement | Description | Key Benchmarking Observables | Representative Performance Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reaction Barrier Accuracy | Predicting accurate activation energies for elementary reaction steps. | - Reaction pathway energetics.- Transition state geometry and energy compared to CCSD(T) or QMC benchmarks [21]. | High-level benchmarks like QUID show that achieving chemical accuracy ( ~1 kcal/mol) requires robust quantum methods. MLFFs trained on DFT data inherit the functional's limitations, highlighting the need for training sets that include high-level reference data [21]. |

| Molecular-Surface Interaction | Modeling the adsorption and dissociation of molecules on catalytic surfaces. | - Adsorption energy.- Dissociation pathways and energy profiles. | In the TEA Challenge, different MLFF architectures produced consistent results for molecule-surface interfaces when trained on the same data, suggesting that dataset quality is more critical than model choice for this challenge [20]. |

| Solvation & Electrolyte Effects | Capturing the role of solvents and electrolytes in reaction mechanisms, relevant to electrocatalysis and battery chemistry. | - Solvation free energy.- Ion pairing and clustering behavior.- Redox potentials. | The OMol25 dataset includes extensive sampling of electrolytes, oxidized/reduced clusters, and degradation pathways, providing a foundation for training MLFFs capable of modeling these complex environments [7] [19]. |

Diagram 1: A generalized workflow for force field benchmarking, highlighting the critical steps from force field selection to final performance analysis against reference data.

Comparative Performance Data

Performance Across Architectures and Domains

Rigorous, multi-architecture benchmarks provide the most reliable performance comparisons.

Table 4: Cross-Domain MLFF Performance from the TEA Challenge 2023 [20]

| MLFF Architecture | Type | Reported Performance Highlights |

|---|---|---|

| MACE | Equivariant Message-Passing NN | Showed consistent performance across molecules, materials, and interfaces. When properly trained, results were weakly dependent on architecture. |

| SO3krates | Equivariant Attention NN | Demonstrated high efficiency and accuracy comparable to other top models on the tested systems. |

| sGDML | Kernel-Based (Global Descriptor) | Accurate for molecular systems where its global descriptor is applicable. |

| FCHL19* | Kernel-Based (Local Descriptor) | Strong performance on a variety of chemical systems, leveraging local atom-centered representations. |

| Key Finding | The choice of a specific modern MLFF architecture is less critical than ensuring it is trained on a complete, reliable, and representative dataset for the target system [20]. |

Universal vs. Specialized Force Fields

The pursuit of universal force fields must be balanced against domain-specific accuracy demands.

Table 5: Universal MLFFs vs. Experimental Reality [17]

| Model Evaluation Focus | Typical Performance | Limitations Revealed by Experimental Benchmarks |

|---|---|---|

| Computational Benchmarks(e.g., energy/force error on test splits) | Often impressive, suggesting high reliability and universality. | May overestimate real-world performance when extrapolated to experimentally complex chemical spaces not well-represented in common training sets [17]. |

| Experimental Benchmarks(e.g., UniFFBench vs. mineral data) | Reveals a "substantial reality gap". | - Density errors exceed practical application thresholds.- Disconnect between simulation stability and mechanical property accuracy.- Performance correlates more with training data representation than modeling method. |

Essential Experimental Protocols

Reproducible benchmarking requires detailed methodologies. Below are protocols for key experiments cited in this guide.

Protocol: Benchmarking Protein Force Fields with Experimental Data

This protocol is based on methodologies used to benchmark force fields for protein stability, as seen in studies of SARS-CoV-2 PLpro [18], and can be adapted using datasets curated for this purpose [22].

System Preparation:

- Obtain the protein's initial coordinates from a reliable source (e.g., RCSB PDB).

- Using a tool like Avogadro [23], prepare the protein structure: add missing hydrogen atoms, and determine correct protonation states for histidine and other ionizable residues at the target pH.

- Solvate the protein in a periodic water box (e.g., with ~10 Å buffer) using a water model like TIP3P, TIP4P, or TIP5P.

- Add physiological concentrations of ions (e.g., 100 mM NaCl) to neutralize the system's charge and replicate experimental conditions.

Simulation Setup:

- Use a molecular dynamics engine like GROMACS [23] or LAMMPS [24].

- Apply the force fields to be tested (e.g., OPLS-AA, CHARMM36, AMBER03) under identical simulation conditions.

- Set temperature to 310 K and maintain with a thermostat (e.g., Nosé-Hoover).

- Set pressure to 1 bar and maintain with a barostat (e.g., Parrinello-Rahman).

- Run equilibration steps: energy minimization, NVT (constant particle number, volume, and temperature) equilibration, and NPT (constant particle number, pressure, and temperature) equilibration.

Production Run and Analysis:

- Run multiple, independent long-timescale MD simulations (hundreds of nanoseconds to microseconds) for each force field.

- Compute key observables:

- Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD): Calculate the backbone RMSD relative to the experimental native structure to assess global stability.

- Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF): Analyze per-residue fluctuations to understand local flexibility.

- Specific Structural Metrics: Monitor distances between key catalytic residues (e.g., Cα(Cys111)-Cα(His272) in PLpro) or dihedral angles to check for active site integrity [18].

- Experimental Comparison: Compare simulation ensembles with experimental data from NMR spectroscopy or room-temperature crystallography, where available [22].

Protocol: Crash-Testing MLFFs with the TEA Challenge Framework

This protocol outlines the procedure for stress-testing MLFFs on diverse systems, as performed in the TEA Challenge [20].

System and Model Selection:

- Select a diverse set of benchmark systems: a small biomolecule (e.g., alanine tetrapeptide), a molecule-surface interface (e.g., 1,8-naphthyridine on graphene), and a periodic material (e.g., methylammonium lead iodide perovskite).

- Choose multiple state-of-the-art MLFFs (e.g., MACE, SO3krates, sGDML) for comparison.

Molecular Dynamics Simulations:

- For each system and MLFF, initiate 12 independent MD trajectories from the same starting structure to assess reproducibility.

- Run simulations under ambient conditions (e.g., 300 K, NVT ensemble) using a standard integrator (e.g., Velocity Verlet) with a 0.5-1.0 fs timestep.

- Ensure all simulations are performed for the same duration to allow direct comparison.

Observable Computation and Analysis:

- From the generated trajectories, compute system-specific observables:

- For biomolecules: Calculate free energy surfaces using principal component analysis or dihedral angles.

- For interfaces: Analyze adsorption geometry and energy.

- For materials: Compute radial distribution functions and thermal stability.

- Key Analysis: Where available, use DFT or experimental data as a reference. In the absence of a single ground truth, perform a comparative analysis of the results across all MLFFs. Consistency among different architectures increases confidence in the predictions [20].

- Critically assess simulation stability, energy conservation, and the physical reasonableness of the observed dynamics.

- From the generated trajectories, compute system-specific observables:

Diagram 2: The MLFF validation workflow. A model must pass beyond static accuracy tests (left) to the more rigorous validation through MD-derived observables and experimental comparison (right), where performance gaps are often revealed.

This table details essential computational tools, datasets, and benchmarks for force field development and validation.

Table 6: Essential Resources for Force Field Research

| Resource Name | Type | Function and Purpose | Relevant Domain |

|---|---|---|---|

| OMol25 Dataset [7] [19] | Training Dataset | A massive dataset of >100 million molecular configurations with high-accuracy (ωB97M-V/def2-TZVPD) DFT calculations. Provides unprecedented chemical diversity for training generalizable MLFFs. | Biomolecules, Electrolytes, Metal Complexes |

| QUID Benchmark [21] | Benchmarking Framework | Provides "platinum standard" interaction energies for ligand-pocket model systems via agreement between CC and QMC methods. Crucial for testing methods on non-covalent interactions. | Drug Design, Biomolecules |

| UniFFBench [17] | Benchmarking Framework | Evaluates UMLFFs against a large set of experimental measurements from mineral structures, exposing the "reality gap" between computational and experimental performance. | Materials Science |

| LAMBench [16] | Benchmarking System | A comprehensive benchmark designed to evaluate Large Atomistic Models (LAMs) on generalizability, adaptability, and applicability across diverse scientific domains. | Cross-Domain |

| LAMMPS [24] | Simulation Software | A highly versatile and widely used open-source molecular dynamics simulator that supports a vast range of force fields, including many MLFFs. | Cross-Domain |

| Quantum ESPRESSO [23] | Simulation Software | An open-source suite for electronic-structure calculations based on DFT. Used to generate high-quality training data for MLFFs. | Materials Science, Chemistry |

| Materials Project [23] | Database | A web-based platform providing computed properties of thousands of known and predicted materials, useful for benchmarking and data sourcing. | Materials Science |

Large Atomistic Models (LAMs) as Emerging Foundation Models for Molecular Systems

In the field of molecular modeling, Large Atomistic Models (LAMs) are emerging as foundational machine learning tools designed to approximate the universal potential energy surface (PES) that governs atomic interactions [25] [16]. Inspired by the success of large language models, LAMs undergo pretraining on vast and diverse datasets of atomic structures, learning a latent representation of the fundamental physics described by the Schrödinger equation under the Born-Oppenheimer approximation [26] [16]. The ultimate goal is to create universal, ready-to-use models that can accurately simulate diverse atomistic systems—from small organic molecules to complex inorganic materials—without requiring system-specific reparameterization [25]. However, the rapid proliferation of these models has created an urgent need for comprehensive benchmarking to evaluate their performance, generalizability, and practical utility across different scientific domains [26]. This guide provides an objective comparison of state-of-the-art LAMs using the recently introduced LAMBench benchmarking framework, offering researchers in computational chemistry and drug development critical insights for selecting appropriate models for their specific applications [27].

The LAMBench Benchmarking Framework

Core Evaluation Metrics and Methodology

The LAMBench framework addresses critical limitations of previous domain-specific benchmarks by providing a comprehensive evaluation system that assesses LAMs across three fundamental capabilities: generalizability, adaptability, and applicability [26] [16].

- Generalizability measures how accurately an LAM performs on datasets not included in its training set, particularly out-of-distribution (OOD) data from different chemical domains. This is evaluated through force field prediction tasks (energy, forces, virials) and domain-specific property calculations [26] [27].

- Adaptability assesses the model's capacity to be fine-tuned for tasks beyond potential energy prediction, with emphasis on learning structure-property relationships for specific scientific applications [26] [16].

- Applicability concerns the practical deployment of LAMs, evaluating computational efficiency (inference time) and numerical stability in molecular dynamics simulations [27] [16].

The benchmark employs a rigorous methodology that includes zero-shot inference with energy-bias term adjustments based on test dataset statistics. Performance metrics are normalized against a baseline "dummy" model that predicts energy solely based on chemical formula without structural information, where a perfect model would score 0 and the dummy model scores 1 [27].

Benchmarking Workflow and Experimental Design

The experimental workflow in LAMBench is designed for high-throughput, automated evaluation across multiple tasks and domains [26] [16]. The following diagram illustrates this comprehensive benchmarking process:

The benchmarking system encompasses three primary domains of atomic systems, each with specialized evaluation tasks [27]:

- Molecules: Evaluated on datasets including ANI-1x, MD22, and AIMD-Chig for force field prediction, with property calculation tasks like TorsionNet500 and Wiggle150 assessing torsional profiles and conformer energies.

- Inorganic Materials: Tested using specialized benchmarks (Torres2019Analysis, Batzner2022equivariant, etc.) for force field prediction, with the MDR phonon benchmark evaluating phonon properties and elasticity benchmarks assessing mechanical properties.

- Catalysis: Assessed on datasets including Vandermause2022Active, Zhang2019Bridging, and Villanueva2024Water for force field prediction, with the OC20NEB-OOD benchmark evaluating reaction energy barriers and pathways.

Performance Comparison of State-of-the-Art LAMs

Comprehensive Model Evaluation Metrics

LAMBench evaluates models using normalized error metrics across multiple domains and prediction types. The generalizability error metric (M̄) combines performance on force field prediction (M̄FF) and property calculation (M̄PC) tasks, while applicability is measured through efficiency (ME) and instability (MIS) metrics [27]. The following table presents the comprehensive performance data for state-of-the-art LAMs:

Table 1: Comprehensive LAMBench Performance Metrics for Large Atomistic Models

| Model | Generalizability Force Field (M̄FF) | Generalizability Property (M̄PC) | Efficiency (ME) | Instability (MIS) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DPA-3.1-3M | 0.175 | 0.322 | 0.261 | 0.572 |

| Orb-v3 | 0.215 | 0.414 | 0.396 | 0.000 |

| DPA-2.4-7M | 0.241 | 0.342 | 0.617 | 0.039 |

| GRACE-2L-OAM | 0.251 | 0.404 | 0.639 | 0.309 |

| Orb-v2 | 0.253 | 0.601 | 1.341 | 2.649 |

| SevenNet-MF-ompa | 0.255 | 0.455 | 0.084 | 0.000 |

| MatterSim-v1-5M | 0.283 | 0.467 | 0.393 | 0.000 |

| MACE-MPA-0 | 0.308 | 0.425 | 0.293 | 0.000 |

| SevenNet-l3i5 | 0.326 | 0.397 | 0.272 | 0.036 |

| MACE-MP-0 | 0.351 | 0.472 | 0.296 | 0.089 |

Note: For all metrics, lower values indicate better performance, except for efficiency (ME) where higher values are preferable. M̄FF and M̄PC represent normalized error metrics where 0 represents a perfect model and 1 represents baseline dummy model performance [27].

Performance Analysis and Key Findings

Analysis of the benchmark results reveals several important trends and performance characteristics:

Top Performers: DPA-3.1-3M demonstrates the best overall generalizability for force field prediction tasks (M̄FF = 0.175), significantly outperforming other models. Orb-v3 shows strong balanced performance with zero instability metrics, making it suitable for stable molecular dynamics simulations [27].

Efficiency Trade-offs: GRACE-2L-OAM and DPA-2.4-7M show excellent computational efficiency (ME = 0.639 and 0.617 respectively), but with moderate instability metrics that may affect long-time-scale simulations. SevenNet-MF-ompa offers exceptional stability but at the cost of lower efficiency [27].

Domain-Specific Strengths: The significant variation between force field (M̄FF) and property calculation (M̄PC) metrics across models indicates substantial differences in domain-specific performance. For instance, SevenNet-l3i5 shows better performance on property calculations than force field predictions, suggesting particular strength in structure-property relationship tasks [27].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Force Field Prediction Accuracy Assessment

The evaluation of force field prediction capabilities follows a rigorous protocol designed to assess model performance across diverse chemical domains [27]:

Dataset Curation: Test sets are carefully selected from three primary domains: molecules (ANI-1x, MD22, AIMD-Chig), inorganic materials (Torres2019Analysis, Batzner2022equivariant, etc.), and catalysis (Vandermause2022Active, Zhang2019Bridging, etc.) to ensure comprehensive coverage.

Zero-Shot Inference: Models are evaluated without any task-specific fine-tuning, using energy-bias term adjustments based on test dataset statistics to account for systematic offsets.

Metric Calculation: Root-mean-square error (RMSE) is used as the primary error metric for energy, force, and virial predictions. These are normalized against a baseline model and aggregated using logarithmic averaging to prevent larger errors from dominating the metrics.

Statistical Aggregation: Performance is weighted across prediction types (energy: 45%, force: 45%, virial: 10% when available) to provide balanced overall metrics for each domain.

Molecular Dynamics Stability Testing

Stability testing follows a standardized protocol to evaluate numerical robustness and energy conservation during molecular dynamics simulations [27]:

System Selection: Nine diverse structures are selected to represent different system types and complexities.

Simulation Conditions: NVE (microcanonical) ensemble simulations are performed to assess energy conservation without external thermostatting effects.

Stability Metric: Instability is quantified by measuring the total energy drift throughout the simulations, with lower values indicating better numerical stability and energy conservation properties.

Efficiency Benchmarking: Computational performance is measured by averaging inference time per atom across 900 configurations of varying sizes (800-1000 atoms) to ensure assessment in the computationally saturated regime.

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for LAM Evaluation

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| Benchmark Datasets | ANI-1x, MD22, MPtrj | Training and evaluation data for organic molecules and inorganic materials [26] |

| Domain Test Sets | Torres2019Analysis, Vandermause2022Active | Out-of-distribution evaluation for specific scientific challenges [27] |

| Property Benchmarks | TorsionNet500, Wiggle150, MDR Phonon | Specialized assessment of molecular and materials properties [27] |

| Software Infrastructure | LAMBench, OpenMM | Automated benchmarking workflows and molecular simulation execution [27] [28] |

| Reference Methods | DFT (PBE, ωB97M) | quantum mechanical reference methods for training data generation [26] |

The comprehensive benchmarking of Large Atomistic Models reveals that while significant progress has been made toward developing universal potential energy surfaces, a substantial gap remains between current LAMs and the ideal of a truly universal, accurate, and robust model [25] [16]. The performance analysis demonstrates that different models excel in specific areas—some in force field accuracy, others in property prediction, and others in computational efficiency or stability—highlighting the need for careful model selection based on specific research requirements [27].

Key findings from the LAMBench evaluation indicate that future development should focus on three critical areas: (1) incorporating cross-domain training data to enhance generalizability across diverse chemical spaces; (2) supporting multi-fidelity modeling to accommodate varying accuracy requirements across research domains; and (3) ensuring strict energy conservation and differentiability to enable stable molecular dynamics simulations [16]. As LAMs continue to evolve, benchmarks like LAMBench will play a crucial role in guiding their development toward becoming truly universal, ready-to-use tools that can significantly accelerate scientific discovery across chemistry, materials science, and drug development [25].

In computational chemistry and materials science, force fields are the fundamental mathematical models that describe the potential energy of a system of atoms and molecules, enabling the study of atomic motion through molecular dynamics (MD) simulations [29]. The accuracy and reliability of these simulations are critically dependent on the force field's components and parametrization. This guide objectively compares different force field paradigms by examining three critical components: the treatment of bond order, the formulation of non-bonded interactions, and the property of conservativeness. The benchmarking context focuses specifically on evaluating these force fields for their accuracy in predicting atomic motion, a capability essential for applications ranging from drug discovery to energetic materials development [30] [6].

The performance of force fields has profound implications in biomedical research, where molecular dynamics simulations have become indispensable for studying protein flexibility, molecular interactions, and facilitating therapeutic development [30]. Similarly, in materials science, accurately simulating the behavior of high-energy materials (HEMs) under various conditions relies on force fields that can faithfully represent both mechanical properties and chemical reactivity [6]. This comparison examines traditional molecular mechanics force fields, reactive force fields, and emerging machine learning potentials, providing researchers with a structured framework for selecting appropriate models based on their specific accuracy requirements and computational constraints.

Comparative Analysis of Force Field Components

Bond Order Treatment Across Force Field Types

The treatment of chemical bonding, particularly how bond formation and breaking is handled, represents a fundamental differentiator among force field types. Traditional molecular mechanics force fields typically employ fixed harmonic or Morse potentials for bond stretching, which effectively maintain bond lengths near equilibrium values but cannot simulate bond dissociation or formation [29] [31]. This approach utilizes a simple harmonic oscillator model where the energy term is calculated as (E{\text{bond}} = \frac{k{ij}}{2}(l{ij}-l{0,ij})^2), with (k{ij}) representing the bond force constant, (l{ij}) the actual bond length, and (l_{0,ij}) the equilibrium bond length [29]. While computationally efficient and suitable for many structural biology applications, this fixed-bond approach is limited to simulating systems where covalent bond topology remains unchanged throughout the simulation.

In contrast, bond order potentials, such as those implemented in reactive force fields (ReaxFF), introduce dynamic bonding capabilities by defining bond order as a function of interatomic distance [6]. This formulation allows for continuous bond formation and breaking during simulations, enabling the study of chemical reactions, decomposition processes, and other reactive phenomena. The ReaxFF methodology utilizes bond-order-dependent polarization charges to model both reactive and non-reactive atomic interactions, though it may struggle to achieve quantum-mechanical accuracy in describing reaction potential energy surfaces [6]. For complex reactive systems like high-energy materials, this dynamic bond representation is essential for capturing fundamental decomposition mechanisms and energy release processes.

More recently, machine learning potentials (MLPs) have emerged that implicitly capture bonding behavior through training on quantum mechanical data. Approaches such as the Deep Potential (DP) scheme and graph neural networks (GNNs) can model complex chemical environments without explicit bond order parameters, potentially offering DFT-level accuracy for reactive processes while maintaining computational efficiency [6]. The EMFF-2025 neural network potential, for instance, has demonstrated capability in predicting decomposition characteristics of high-energy materials with C, H, N, and O elements, uncovering surprisingly similar high-temperature decomposition mechanisms across different HEMs [6].

Table 1: Comparison of Bond Treatment Methodologies in Different Force Fields

| Force Field Type | Bond Representation | Reactive Capability | Computational Cost | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classical MM | Fixed harmonic potentials | No | Low | Protein folding, structural biology |

| Reactive (ReaxFF) | Distance-dependent bond order | Yes | Medium-High | Combustion, decomposition, catalysis |

| Machine Learning | Implicit through NN training | Yes (if trained on reactive data) | Varies (training high/inference medium) | Complex reactive systems, materials discovery |

Non-Bonded Interactions: Formulations and Accuracy

Non-bonded interactions encompass both van der Waals forces and electrostatic interactions, playing a critical role in determining molecular conformation, binding affinities, and supramolecular assembly. The standard approach for van der Waals interactions in molecular mechanics force fields utilizes the Lennard-Jones 12-6 potential, formulated as (V{LJ}({r{ij}}) = \frac{C{ij}^{(12)}}{{r{ij}}^{12}} - \frac{C{ij}^{(6)}}{{r{ij}}^6}) or alternatively as (V{LJ}(\mathbf{r}{ij}) = 4\epsilon{ij}\left(\left(\frac{\sigma{ij}} {{r{ij}}}\right)^{12} - \left(\frac{\sigma{ij}}{{r{ij}}}\right)^{6} \right)), where (\epsilon{ij}) represents the well depth and (\sigma{ij}) the collision diameter [32] [29]. This potential captures both short-range repulsive and longer-range attractive dispersion forces, with parameters typically determined through combination rules such as Lorentz-Berthelot ((\sigma{ij} = \frac{1}{2}(\sigma{ii} + \sigma{jj})); (\epsilon{ij} = \left({\epsilon{ii} \, \epsilon_{jj}}\right)^{1/2})) or geometric averaging [32].

For electrostatic interactions, the predominant model in class I additive force fields employs Coulomb's law with fixed partial atomic charges: (Vc({r{ij}}) = f \frac{qi qj}{{\varepsilonr}{r{ij}}}), where (f = \frac{1}{4\pi \varepsilon0} = 138.935\,458) and (\varepsilonr) represents the relative dielectric constant [32] [29]. This treatment assumes charge distributions remain fixed throughout simulations, which represents a significant simplification of electronic polarization effects. In biomolecular force fields, this approach has proven remarkably successful despite its simplicity, though it struggles with environments where electronic polarization significantly varies, such as heterogeneous systems or interfaces between regions with different dielectric properties [31].

The Buckingham potential offers an alternative to the Lennard-Jones formulation for van der Waals interactions, replacing the R⁻¹² repulsion term with an exponential form: (V{bh}({r{ij}}) = A{ij} \exp(-B{ij} {r{ij}}) - \frac{C{ij}}{{r_{ij}}^6}) [32]. While potentially offering a more realistic repulsion profile, this potential is computationally more expensive and less widely supported in modern MD software [32]. For electrostatic interactions in periodic systems, the Particle Mesh Ewald (PME) method has become the standard for efficiently handling long-range electrostatic interactions, while reaction field approaches provide an alternative for non-periodic systems by modeling the solvent as a dielectric continuum beyond a specified cutoff [32].

Machine learning potentials represent non-bonded interactions through trained neural networks rather than explicit functional forms. For example, the EMFF-2025 model demonstrates that neural network potentials can achieve DFT-level accuracy in predicting both energies and forces for complex molecular systems, with mean absolute errors for energy predominantly within ± 0.1 eV/atom and forces mainly within ± 2 eV/Å [6]. This approach can effectively capture many-body effects and complex electronic phenomena without requiring explicit functional forms for polarization, though it demands extensive training data and computational resources for model development.

Table 2: Non-Bonded Interaction Formulations Across Force Field Types

| Interaction Type | Standard Formulation | Advanced Alternatives | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| van der Waals | Lennard-Jones 12-6 potential | Buckingham potential, ML-learned representations | LJ: Hard repulsion; Buckingham: computational cost |

| Electrostatics | Coulomb with fixed charges | Polarizable force fields, ML representations | Missing electronic polarization in fixed-charge models |

| Long-Range Treatments | Particle Mesh Ewald (PME), Reaction field | Accuracy-computational cost trade-offs |

Conservativeness: Energy Conservation in Dynamics

In molecular dynamics simulations, conservativeness refers to a force field's ability to conserve energy in microcanonical (NVE) ensemble simulations, a fundamental requirement for producing physically realistic trajectories. The conservative property depends critically on the functional form of the potential energy expression and the numerical integration methods employed. Traditional molecular mechanics force fields, when combined with appropriate integration algorithms and time steps, generally exhibit excellent energy conservation properties for systems where the potential energy surface is smooth and the bonded interactions remain near their equilibrium values [29] [31].

The class I additive potential energy function, which separates energy into distinct bonded and non-bonded components ((E{\text{total}}=E{\text{bonded}}+E_{\text{nonbonded}})), has demonstrated robust conservation characteristics across diverse biomolecular simulations [29] [31]. This formulation typically includes harmonic bond and angle terms, periodic dihedral functions, and pairwise non-bonded interactions, creating a smoothly varying potential energy surface that facilitates stable numerical integration. However, the introduction of more complex functional forms, such as the cross-terms found in class II and III force fields or the distance-dependent bond orders in reactive force fields, can create more complex energy landscapes that present challenges for numerical integration and energy conservation [31].

For reactive force fields like ReaxFF, the dynamic nature of bonding interactions and the complex functional forms required to describe bond formation and breaking can introduce non-conservative behavior if not carefully parameterized and implemented [6]. Similarly, machine learning potentials face unique challenges regarding conservativeness, as they must learn forces as derivatives of a conservative potential energy field. The Deep Potential scheme and similar approaches address this by constructing networks that explicitly satisfy the relationship between energy and forces, ensuring conservative dynamics by design [6]. The EMFF-2025 neural network potential demonstrates that properly constructed ML potentials can achieve excellent conservation while maintaining DFT-level accuracy, enabling large-scale reactive simulations that were previously infeasible with either traditional force fields or direct quantum mechanical methods [6].

Experimental Benchmarking Methodologies

Protocol for Accuracy Assessment

Benchmarking force field accuracy requires systematic comparison against reference data, typically from quantum mechanical calculations or experimental measurements. A robust assessment protocol involves multiple validation stages, beginning with basic property predictions and progressing to complex dynamic behavior. For structural accuracy, force fields should be evaluated on their ability to reproduce equilibrium geometries, including bond lengths, angles, and dihedral distributions compared to crystallographic data or DFT-optimized structures. The EMFF-2025 validation approach demonstrates this principle, with systematic evaluation of energy and force predictions against DFT calculations across 20 different high-energy materials, providing comprehensive error statistics including mean absolute errors for both energies and forces [6].

For thermodynamic properties, benchmarking should include comparison of formation energies, sublimation enthalpies, vaporization energies, and solvation free energies against experimental measurements or high-level quantum chemical calculations. In materials science applications, mechanical properties such as elastic constants, bulk moduli, and stress-strain relationships provide critical validation metrics [6]. The performance of the EMFF-2025 model in predicting mechanical properties of HEMs at low temperatures illustrates the importance of mechanical property validation even for primarily reactive applications [6].

Reactive force fields and ML potentials designed for chemical transformations require additional validation of reaction barriers, reaction energies, and product distributions. For the CHNO system containing high-energy materials, this includes comparing decomposition pathways, activation energies, and time evolution of reaction products against both experimental data and DFT reference calculations [6]. The ability of the EMFF-2025 model to uncover unexpected similarities in high-temperature decomposition mechanisms across different HEMs demonstrates the value of comprehensive reaction validation [6].

Protocol for Conservativeness Testing

Energy conservation testing requires careful implementation of microcanonical (NVE) ensemble simulations with controlled initial conditions. A standardized protocol begins with energy minimization of the system to remove high-energy contacts and inappropriate geometries that could introduce numerical instabilities. This should be followed by a gradual equilibration phase, typically in the isothermal-isobaric (NPT) or canonical (NVT) ensemble, to establish appropriate starting velocities corresponding to the target temperature. The system is then transitioned to the NVE ensemble for production simulation, during which the total energy is monitored as a function of time.

The key metric for conservativeness assessment is the drift in total energy over time, typically normalized by the number of atoms in the system and expressed as the change per nanosecond of simulation. For a well-conserved force field, this drift should be minimal compared to the fluctuations in potential and kinetic energy. Additional stability metrics include monitoring of temperature drift (which should be minimal in a properly conserved system) and conservation of linear and angular momentum. For reactive systems, special attention should be paid to energy conservation during bond formation and breaking events, as these processes can introduce discontinuities or rapid changes in the potential energy that challenge numerical integration.

Long-time stability testing extends these assessments to multi-nanosecond timescales, evaluating whether small errors accumulate significantly over extended simulations. This is particularly important for machine learning potentials, where the learned energy surface may contain small inaccuracies that become apparent only in prolonged dynamics. The DP-GEN framework used in developing potentials like EMFF-2025 incorporates iterative training and validation cycles to identify and address such limitations, ensuring robust conservation across diverse chemical environments [6].

Comparative Performance Data

Quantitative Benchmarking Results

Systematic benchmarking reveals distinct performance profiles across force field types. Traditional molecular mechanics force fields such as those in the CHARMM, AMBER, and OPLS families typically achieve energy errors of 1-4 kJ/mol for organic molecules relative to high-level quantum chemical calculations, with slightly higher errors for conformational energies [31]. These force fields demonstrate excellent computational efficiency, enabling microsecond to millisecond simulations of biomolecular systems with thousands to millions of atoms. Their fixed bonding topology, however, limits application to non-reactive systems and requires specialized parameterization for non-standard molecules.

Reactive force fields like ReaxFF show significantly higher computational demands—typically 10-50× slower than traditional MM force fields—while offering the critical capability to simulate bond rearrangement and chemical reactions [6]. Accuracy varies considerably across chemical space, with reported errors in reaction barriers often reaching 20-40 kJ/mol or higher depending on the specific system and parameterization [6]. The ReaxFF methodology has demonstrated particular utility in studying decomposition processes in high-energy materials, though it may exhibit "significant deviations" from DFT potential energy surfaces, especially when applied to new molecular systems [6].

Machine learning potentials represent an emerging paradigm offering potentially transformative capabilities. The EMFF-2025 model demonstrates DFT-level accuracy with mean absolute errors for energy predominantly within ± 0.1 eV/atom (∼9.6 kJ/mol) and forces mainly within ± 2 eV/Å [6]. While training requires substantial computational resources, inference during MD simulations can be highly efficient, with some ML potentials achieving performance within one order of magnitude of traditional force fields while maintaining near-quantum accuracy. The transfer learning approach employed in EMFF-2025 development shows particular promise, enabling adaptation to new chemical systems with minimal additional training data [6].

Table 3: Performance Comparison of Force Field Types

| Force Field Type | Typical Energy Error | Reactive Capability | Relative Speed | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional MM | 1-4 kJ/mol | No | 1× (reference) | Protein folding, drug binding |

| Reactive (ReaxFF) | 20-40 kJ/mol (barriers) | Yes | 0.01-0.1× | Combustion, decomposition |

| Machine Learning | 4-10 kJ/mol | Yes (if trained for it) | 0.1-0.5× | Complex materials, reactive systems |

Table 4: Essential Tools for Force Field Development and Validation

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Relevance to Benchmarking |

|---|---|---|---|

| GROMACS | MD Software | High-performance molecular dynamics | Production simulations, efficiency testing |

| DP-GEN | ML Framework | Neural network potential generation | Automated training of ML potentials |

| AMBER/CHARMM | MD Software/Force Field | Biomolecular simulations | Reference implementations for MM force fields |

| LAMMPS | MD Software | General-purpose molecular dynamics | Reactive force field simulations |

| Lennard-Jones Potential | Mathematical Form | van der Waals interactions | Standard non-bonded treatment |

| Particle Mesh Ewald | Algorithm | Long-range electrostatics | Accurate electrostatic treatment in periodic systems |

| Buckingham Potential | Mathematical Form | Alternative van der Waals | More realistic repulsion at short ranges |

The comparative analysis presented in this guide reveals a complex landscape of force field methodologies, each with distinct strengths and limitations for atomic motion accuracy research. Traditional molecular mechanics force fields offer computational efficiency and excellent energy conservation for non-reactive systems but lack capability for modeling chemical transformations. Reactive force fields address this limitation through dynamic bond order formulations but face challenges in achieving quantum-mechanical accuracy across diverse chemical systems. Machine learning potentials represent a promising emerging approach, offering the potential for DFT-level accuracy while maintaining reasonable computational efficiency, though they require extensive training data and careful validation.

For researchers focused on biomolecular systems where covalent bonds remain intact, traditional force fields like those in the CHARMM, AMBER, and OPLS families continue to offer robust performance with well-established parameterization protocols. Those investigating reactive processes in materials science or chemistry should consider reactive force fields or machine learning potentials, with the choice dependent on the required accuracy, available computational resources, and existence of appropriate parameter sets or training data. The EMFF-2025 model demonstrates how transfer learning strategies can extend the applicability of ML potentials to new chemical systems with minimal additional training, suggesting a promising direction for future force field development.

As force field methodologies continue to evolve, particularly with the integration of machine learning approaches, researchers should maintain rigorous benchmarking practices to validate both accuracy and conservation properties. The experimental protocols and comparative data presented here provide a foundation for these assessments, enabling informed selection of appropriate force fields for specific research applications in drug development, materials science, and fundamental chemical physics.

Benchmarking Methodologies: Implementing Robust Evaluation Frameworks

In computational chemistry and materials science, the emergence of machine learning interatomic potentials (MLIPs) has revolutionized molecular and materials modeling. These data-driven models approximate the universal potential energy surface (PES) defined by first-principles quantum mechanical calculations, enabling faster and more accurate simulations of atomic systems [16]. As the number and complexity of MLIPs grow, comprehensive benchmarking platforms have become essential for evaluating their performance, guiding development, and informing users about their relative strengths and limitations. This guide provides an objective comparison of three prominent benchmarking platforms: LAMBench, CHIPS-FF, and MLIP-Arena.

These platforms address critical limitations of earlier, domain-specific benchmarks by offering more comprehensive evaluation frameworks. They move beyond static error metrics tied to specific density functional theory (DFT) references toward assessing real-world applicability, physical consistency, and performance across diverse scientific domains [33] [16]. This shift is crucial for developing robust, generalizable force fields that can accelerate scientific discovery in fields ranging from drug development to materials design.

LAMBench: Evaluating Large Atomistic Models

LAMBench (Large Atomistic Model Benchmark) is designed specifically to evaluate LAMs, also known as machine learning interatomic potentials (MLIPs), which function as foundation models for atomic interactions [27] [16]. Its mission is to provide a comprehensive benchmark covering diverse atomic systems across multiple domains, moving beyond domain-specific benchmarks to assess how closely these models approach a universal potential energy surface [27] [34]. The platform employs a sophisticated benchmarking system that evaluates models across three core capabilities: generalizability, adaptability, and applicability [16].

Generalizability assesses model accuracy on out-of-distribution datasets not included in training, with specialized tests for force field prediction ((MˉFFm)) and property calculation ((MˉPCm)) [27] [16]. Adaptability measures a model's capacity to be fine-tuned for tasks beyond potential energy prediction, particularly structure-property relationships. Applicability concerns the practical deployment of models, evaluating their stability and efficiency in real-world simulations through metrics for efficiency ((MEm)) and instability ((MISm)) [27].

CHIPS-FF: Materials Simulation Framework

CHIPS-FF (CHemical Informatics and Properties Simulation Force Field) provides a comprehensive framework for performing materials simulations with machine learning force fields [35] [36]. Developed in connection with the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) and its JARVIS database, CHIPS-FF integrates closely with materials databases and the Atomic Simulation Environment (ASE) to facilitate various materials simulations and workflows [35]. Unlike the other platforms, CHIPS-FF functions both as a benchmarking tool and a simulation framework.