Atomic Motion Tracking: The Fundamental Principles and Biomedical Applications of Molecular Dynamics

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations, a computational technique that tracks the physical movements of every atom in a system over time.

Atomic Motion Tracking: The Fundamental Principles and Biomedical Applications of Molecular Dynamics

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations, a computational technique that tracks the physical movements of every atom in a system over time. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it covers the foundational principles of MD, from solving Newton's equations of motion to the critical role of force fields. It details methodological workflows and cutting-edge applications in drug discovery, including binding affinity calculation and drug delivery system optimization. The content also addresses practical challenges like computational limits and force field accuracy, while outlining strategies for validation against experimental data and comparing traditional physics-based methods with emerging machine learning potentials. This guide serves as a bridge between theoretical simulation and real-world therapeutic innovation.

The Core Engine: Understanding the Basic Principles of Molecular Dynamics

The quest to predict the motion of physical objects, from celestial bodies to subatomic particles, represents a cornerstone of scientific inquiry. At the heart of this endeavor lies Newton's second law of motion, which establishes a fundamental relationship between the force acting on an object, its mass, and its resulting acceleration. This principle provides the foundational framework for classical mechanics, governing the behavior of systems across countless scales and contexts [1] [2]. In modern scientific research, particularly in the field of molecular dynamics (MD), this classical equation transforms into a powerful computational tool that enables scientists to track atomic trajectories with remarkable precision. Molecular dynamics simulations leverage Newton's equations to model the time evolution of molecular systems, offering unprecedented insights into processes critical for drug development, materials science, and biomedical research [3]. This technical guide examines the mathematical foundation, computational implementation, and practical application of Newton's laws in atomic-scale modeling, providing researchers with the theoretical background and methodological protocols necessary to implement these principles in cutting-edge scientific investigations.

Theoretical Foundations: Newton's Laws and Their Mathematical Formulation

Newton's Laws of Motion

Sir Isaac Newton's three laws of motion, first published in his 1687 work "Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica," provide the complete description necessary to understand and predict the motion of objects under the influence of forces [1] [2]:

Newton's First Law (Law of Inertia): "An object at rest remains at rest, and an object in motion remains in motion at constant speed and in a straight line unless acted upon by an unbalanced force" [2] [4]. This principle establishes the concept of inertia, describing the natural tendency of objects to maintain their state of motion. In molecular dynamics, this implies that atoms will maintain their velocity unless influenced by interatomic forces.

Newton's Second Law (Fundamental Equation of Motion): "The acceleration of an object depends on the mass of the object and the amount of force applied" [2]. Mathematically, this is expressed as ( \mathbf{F} = m\mathbf{a} ), where ( \mathbf{F} ) represents the net force acting on an object, ( m ) is its mass, and ( \mathbf{a} ) is its acceleration. In the more general form, force equals the rate of change of momentum: ( \mathbf{F} = \frac{d\mathbf{p}}{dt} ), where ( \mathbf{p} = m\mathbf{v} ) is momentum [1]. This equation serves as the central governing principle for molecular dynamics simulations.

Newton's Third Law (Action-Reaction): "Whenever one object exerts a force on another object, the second object exerts an equal and opposite force on the first" [2]. This principle of reciprocal forces ensures conservation of momentum in closed systems and is fundamental to modeling interatomic interactions in molecular simulations.

The Fundamental Equation in Classical and Molecular Contexts

The mathematical expression of Newton's second law provides the direct link between macroscopic physics and atomic-scale modeling. In its standard form for constant mass systems, the equation is:

[ \mathbf{F} = m\mathbf{a} = m\frac{d^2\mathbf{s}}{dt^2} ]

where ( \mathbf{s} ) represents position [1]. In molecular dynamics, this relationship transforms into a computational algorithm where the force ( \mathbf{F}_i ) on each atom ( i ) is derived from the potential energy function ( U(\mathbf{r}^N) ) of the system:

[ \mathbf{F}i = -\nablai U(\mathbf{r}^N) = mi \frac{d^2\mathbf{r}i}{dt^2} ]

Here, ( \mathbf{r}i ) denotes the position vector of atom ( i ), ( mi ) its mass, and ( \nabla_i ) represents the gradient with respect to the coordinates of atom ( i ) [3]. This equation forms the core of molecular dynamics integration, where the continuous equation is discretized into finite time steps to numerically solve for atomic trajectories.

Table 1: Key Physical Quantities in Newtonian Mechanics and Molecular Dynamics

| Quantity | Symbol | Macroscopic Interpretation | Molecular Dynamics Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Force | ( \mathbf{F} ) | Push or pull acting on an object | Negative gradient of potential energy: ( -\nabla U ) |

| Mass | ( m ) | Measure of inertia | Atomic mass from force field parameters |

| Acceleration | ( \mathbf{a} ) | Rate of change of velocity | Second derivative of atomic position |

| Momentum | ( \mathbf{p} ) | Product of mass and velocity | Conservation ensured by Newton's third law |

| Position | ( \mathbf{s}, \mathbf{r} ) | Location in coordinate system | Atomic coordinates in simulation box |

Computational Implementation: From Mathematical Formalism to Atomic Trajectories

Numerical Integration Methods for Atomic Motion

The practical application of Newton's equation in molecular dynamics requires discretization of time into finite steps ( \Delta t ), typically ranging from 0.5 to 2 femtoseconds (10⁻¹⁵ seconds). Several algorithms have been developed to numerically integrate the equations of motion:

Verlet Algorithm: One of the most widely used integration methods in MD, the Verlet algorithm calculates new positions using current positions, previous positions, and current accelerations:

[ \mathbf{r}(t + \Delta t) = 2\mathbf{r}(t) - \mathbf{r}(t - \Delta t) + \mathbf{a}(t)\Delta t^2 ]

where ( \mathbf{a}(t) = \mathbf{F}(t)/m ) is calculated from the force field at each step [3].

Velocity Verlet Algorithm: This variant explicitly includes velocity calculations and is often preferred for its numerical stability:

[ \mathbf{r}(t + \Delta t) = \mathbf{r}(t) + \mathbf{v}(t)\Delta t + \frac{1}{2}\mathbf{a}(t)\Delta t^2 ] [ \mathbf{v}(t + \Delta t) = \mathbf{v}(t) + \frac{\mathbf{a}(t) + \mathbf{a}(t + \Delta t)}{2}\Delta t ]

Leap-frog Algorithm: This method calculates velocities at half-time steps, offering computational efficiency:

[ \mathbf{v}(t + \frac{1}{2}\Delta t) = \mathbf{v}(t - \frac{1}{2}\Delta t) + \mathbf{a}(t)\Delta t ] [ \mathbf{r}(t + \Delta t) = \mathbf{r}(t) + \mathbf{v}(t + \frac{1}{2}\Delta t)\Delta t ]

These integration methods enable the step-by-step propagation of the system through time, generating atomic trajectories that can be analyzed to extract thermodynamic, kinetic, and structural properties of the molecular system.

Force Calculation in Molecular Systems

The accurate computation of forces represents the most computationally intensive component of molecular dynamics simulations. Forces are derived from the potential energy function ( U(\mathbf{r}^N) ), which typically includes multiple terms:

[ U(\mathbf{r}^N) = U{bonded} + U{nonbonded} = \sum{bonds} \frac{1}{2}kb(b - b0)^2 + \sum{angles} \frac{1}{2}k{\theta}(\theta - \theta0)^2 + \sum{dihedrals} k{\phi}[1 + \cos(n\phi - \delta)] + \sum{i

The force on each atom ( i ) is then calculated as the negative gradient of this potential: ( \mathbf{F}i = -\nablai U(\mathbf{r}^N) ) [3].

Table 2: Molecular Dynamics Integration Methods Comparison

| Method | Computational Cost | Numerical Stability | Energy Conservation | Implementation Complexity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Verlet | Low | High | Good | Low |

| Velocity Verlet | Medium | High | Excellent | Medium |

| Leap-frog | Low | Medium | Good | Low |

| Beeman | Medium | High | Excellent | High |

| Runge-Kutta | High | Medium | Good | High |

Molecular Dynamics Workflow: From Newton's Equations to Scientific Insight

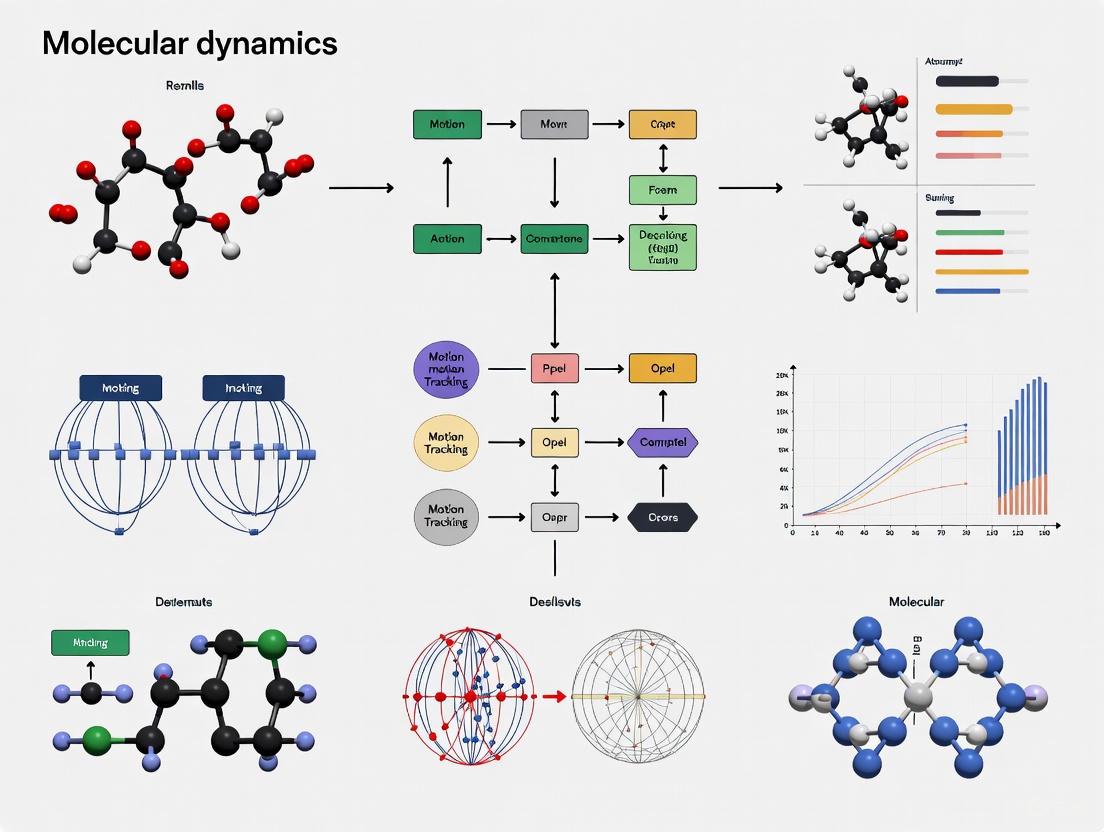

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive workflow of a molecular dynamics simulation, highlighting how Newton's laws are applied at each stage:

Molecular Dynamics Simulation Workflow

Experimental Protocols: Practical Implementation for Research Applications

Standard Molecular Dynamics Protocol for Protein-Ligand Systems

System Preparation:

- Obtain initial coordinates for the protein and ligand from experimental structures (Protein Data Bank) or homology modeling.

- Parameterize the ligand using quantum chemical calculations (GAUSSIAN, ORCA) or force field toolkits (CGenFF, ACPYPE).

- Solvate the system in a water box (TIP3P, TIP4P water models) with dimensions ensuring at least 10 Å between the protein and box edges.

- Add counterions to neutralize system charge using Monte Carlo ion placement methods.

Energy Minimization:

- Perform steepest descent minimization for 5,000 steps to remove steric clashes.

- Continue with conjugate gradient minimization until the energy convergence criterion is met (force tolerance < 1000 kJ/mol/nm).

- Verify minimized structure by analyzing potential energy and maximum force components.

System Equilibration:

- Conduct NVT equilibration for 100 ps with position restraints on heavy atoms (force constant 1000 kJ/mol/nm²) at 300 K using the Berendsen thermostat.

- Perform NPT equilibration for 100-500 ps with semi-isotropic pressure coupling at 1 bar using the Parrinello-Rahman barostat.

- Gradually release position restraints during additional NPT equilibration until all restraints are removed.

Production Simulation:

- Run unrestrained MD simulation for timescales appropriate to the biological process (typically 100 ns to 1 μs).

- Use a 2-fs time step with bonds to hydrogen atoms constrained using LINCS.

- Employ Particle Mesh Ewald method for long-range electrostatics with 10 Å real-space cutoff.

- Save atomic coordinates every 10-100 ps for subsequent analysis.

Advanced Sampling Methods for Enhanced Conformational Exploration

For processes with high energy barriers or rare events, standard MD protocols may be insufficient. Advanced sampling techniques include:

Umbrella Sampling: Apply harmonic biases along a reaction coordinate to sample high-energy regions, then reconstruct the free energy surface using the Weighted Histogram Analysis Method (WHAM).

Metadynamics: Add history-dependent Gaussian potentials along collective variables to discourage revisiting of conformational space, effectively filling energy wells to facilitate barrier crossing.

Replica Exchange MD (REMD): Run parallel simulations at different temperatures (or Hamiltonian parameters), allowing periodic exchange of configurations between replicas according to the Metropolis criterion, enhancing conformational sampling.

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Components for Molecular Dynamics

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Molecular Dynamics

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Application Context | Example Implementations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Force Fields | Define potential energy functions | Parameterize interatomic interactions | CHARMM, AMBER, OPLS, GROMOS |

| Water Models | Solvent representation | Biomolecular solvation environment | TIP3P, TIP4P, SPC, TIP5P |

| Integration Algorithms | Solve equations of motion | Propagate system through time | Verlet, Velocity Verlet, Leap-frog |

| Enhanced Sampling Methods | Accelerate rare events | Overcome energy barriers | Umbrella Sampling, Metadynamics, REMD |

| Analysis Tools | Extract properties from trajectories | Calculate observables and statistics | MDAnalysis, GROMACS tools, VMD |

| Quantum Chemistry Software | Parameter development | Derive force field parameters | GAUSSIAN, ORCA, NWChem |

Applications in Drug Development and Biomedical Research

Molecular dynamics simulations leveraging Newton's equations have become indispensable tools in modern drug discovery and development pipelines. Recent advances highlighted in comprehensive reviews demonstrate how MD simulations provide critical insights for polymer design in pharmaceutical formulations and drug delivery systems [3]. Key applications include:

Drug-Target Binding Mechanisms: MD simulations enable researchers to characterize the binding pathways of small molecule drugs to their protein targets, providing atomic-level details of binding kinetics and thermodynamics that inform structure-based drug design.

Membrane Permeability Prediction: Simulations of drug molecules crossing lipid bilayers yield permeability coefficients that correlate with experimental measurements, aiding in the optimization of drug candidates for improved bioavailability.

Protein Conformational Changes: Long-timescale simulations capture large-scale protein rearrangements that often play critical roles in biological function and drug action, including allosteric regulation and activation mechanisms.

Polymer-Based Drug Delivery Systems: As highlighted in recent literature, MD techniques enable the rational design of polymers for controlled drug release by modeling polymer-drug interactions, degradation kinetics, and release mechanisms at the atomic scale [3].

The integration of machine learning approaches with molecular dynamics represents a frontier in the field, with potential to dramatically accelerate sampling and improve prediction accuracy for complex biological systems relevant to drug development.

Validation and Analysis: Connecting Simulation to Experimental Data

Trajectory Analysis Methods

The validation of molecular dynamics simulations requires rigorous comparison with experimental data through comprehensive trajectory analysis:

Structural Properties:

- Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) to assess structural stability

- Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF) to identify flexible regions

- Radius of gyration to monitor global compaction

Dynamic Properties:

- Mean Square Displacement (MSD) for diffusion coefficient calculation

- Velocity autocorrelation functions for spectral density

- Hydrogen bond lifetime analysis for interaction stability

Energetic Properties:

- Potential energy time series for stability assessment

- Free energy calculations using umbrella sampling or metadynamics

- Binding energy estimation through MM/PBSA or MM/GBSA methods

Statistical Mechanics Connection

Molecular dynamics simulations provide a bridge between Newton's classical equations and statistical mechanics through the ergodic hypothesis, which states that the time average of a property along an MD trajectory equals the ensemble average. This connection enables the calculation of thermodynamic observables:

[ \langle A \rangle = \lim{T \to \infty} \frac{1}{T} \int0^T A(t)dt ]

where ( A ) is any observable property, and the angle brackets denote the ensemble average. This fundamental relationship allows researchers to extract experimentally relevant thermodynamic quantities from atomic-level simulations based on Newtonian mechanics.

From its formulation in the 17th century to its current application in cutting-edge molecular simulations, Newton's fundamental equation of motion continues to provide the theoretical foundation for understanding and predicting physical behavior across scales. The transformation of ( \mathbf{F} = m\mathbf{a} ) into a computational algorithm for tracking atomic trajectories represents one of the most successful applications of classical physics in modern scientific research. As molecular dynamics methodologies continue to evolve, particularly through integration with machine learning approaches and advances in high-performance computing [3], Newton's laws remain firmly at the core of these developments. For researchers in drug development and biomedical sciences, mastering the principles and applications outlined in this guide provides the necessary foundation to leverage molecular dynamics simulations for investigating complex biological processes, designing novel therapeutics, and advancing scientific knowledge at the atomic scale.

In molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, the precise tracking of atomic motion relies on the fundamental laws of classical mechanics, where the forces acting on every atom determine their trajectories and velocities. At the heart of this computational methodology lies the force field, a mathematical model that describes the potential energy of a system as a function of the nuclear coordinates. Force fields serve as the critical link between atomic structure and molecular behavior, enabling the prediction of physicochemical properties from the atomistic level upward. Their accuracy is paramount, as the force field directly governs the simulated evolution of the molecular system, making it a cornerstone of research in structural biology, materials science, and computer-aided drug design [5] [6].

This technical guide details the core principles of force fields, their functional forms, parameterization strategies, and application within MD workflows. The content is framed to support a broader thesis on the basic principles of molecular dynamics atomic motion tracking research, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a comprehensive overview of the tools and methodologies essential for rigorous simulation studies.

Fundamental Concepts and Classification

A force field is a computational model composed of a functional form and a corresponding set of parameters. The functional form is a collection of mathematical functions that describe how the potential energy of a system depends on the positions of its atoms. The parameters are the numerical values that define the specific characteristics of different atom types and their interactions [5]. In MD simulations, the force on each particle is derived as the negative gradient of this potential energy with respect to the particle's coordinates [5].

Force fields can be systematically classified based on several key attributes, as illustrated in the ontology below [7].

The primary classification of force fields is based on their modeling approach and level of detail:

- Modeling Approach: Component-specific force fields are developed to describe a single, specific substance (e.g., a particular water model), offering high accuracy for that substance at the cost of transferability. In contrast, transferable force fields are constructed from building blocks (e.g., atom types or functional groups) that can be applied to a wide range of molecules, providing broad applicability [5] [7]. This guide focuses predominantly on transferable force fields, which form the basis for most biomolecular simulations.

- Level of Detail: The model resolution is a key differentiator.

- All-Atom: Explicitly represents every atom in the system, including hydrogen atoms. This provides the highest level of detail but is computationally demanding [5] [8].

- United-Atom: Treats hydrogen atoms attached to carbon (e.g., in methyl or methylene groups) as a single interaction center with the carbon atom. This reduces the number of particles and increases computational efficiency [5] [7].

- Coarse-Grained: Groups multiple atoms into a single "bead" or interaction site, sacrificing chemical details to simulate larger systems and longer timescales [5] [6].

Mathematical Formulation of Force Fields

The total potential energy ( E_{\text{total}} ) in a typical additive force field is a sum of bonded and nonbonded interaction terms [5] [8] [6]:

[ E{\text{total}} = E{\text{bonded}} + E_{\text{nonbonded}} ]

Where the bonded energy is further decomposed as:

[ E{\text{bonded}} = E{\text{bond}} + E{\text{angle}} + E{\text{dihedral}} ]

And the nonbonded energy is given by:

[ E{\text{nonbonded}} = E{\text{electrostatic}} + E_{\text{van der Waals}} ]

The following sections detail the standard functional forms for each term.

Bonded Interactions

Bonded interactions describe the energy associated with the covalent bond structure of the molecule.

Bond Stretching: The energy required to stretch or compress a chemical bond from its equilibrium length is typically modeled by a harmonic potential, analogous to a spring obeying Hooke's law [5] [6]: [ E{\text{bond}} = \sum{\text{bonds}} \frac{k{ij}}{2}(l{ij} - l{0,ij})^2 ] Here, ( k{ij} ) is the force constant, ( l{ij} ) is the instantaneous bond length, and ( l{0,ij} ) is the equilibrium bond length between atoms ( i ) and ( j ). For a more realistic description that allows for bond dissociation, the Morse potential can be used, though it is computationally more expensive [5].

Angle Bending: The energy penalty for distorting the angle between three bonded atoms from its equilibrium value is also commonly described by a harmonic function [8] [6]: [ E{\text{angle}} = \sum{\text{angles}} \frac{k{\theta{ijk}}}{2}(\theta{ijk} - \theta{0,ijk})^2 ] Here, ( k{\theta{ijk}} ) is the angle force constant, ( \theta{ijk} ) is the instantaneous angle, and ( \theta{0,ijk} ) is the equilibrium angle formed by atoms ( i ), ( j ), and ( k ).

Dihedral Torsions: This term describes the energy associated with rotation around a central bond connecting four atoms. It is typically modeled by a periodic cosine series [5] [6]: [ E{\text{dihedral}} = \sum{\text{dihedrals}} k{\chi{ijkl}} (1 + \cos(n\chi{ijkl} - \delta)) ] Here, ( k{\chi{ijkl}} ) is the dihedral force constant, ( n ) is the multiplicity (defining the number of energy minima in a 360° rotation), ( \chi{ijkl} ) is the dihedral angle, and ( \delta ) is the phase angle.

Improper Torsions: These terms are not true torsions but are used to enforce out-of-plane bending, such as maintaining the planarity of aromatic rings and other conjugated systems [5]. Their functional form can vary between force fields.

Cross-terms: Some advanced force fields include cross-terms that account for coupling between different internal coordinates, such as the influence of bond stretching on angle bending [8].

Nonbonded Interactions

Nonbonded interactions occur between atoms that are not directly bonded or are separated by more than three covalent bonds. They are computationally intensive as they must be calculated for a vast number of atom pairs.

Van der Waals Forces: These short-range forces account for attractive dispersion and repulsive Pauli exclusion interactions. The most common model is the Lennard-Jones (LJ) 12-6 potential [5] [6]: [ E{\text{van der Waals}} = \sum{i \neq j} \epsilon{ij} \left[ \left( \frac{R{\min, ij}}{r{ij}} \right)^{12} - 2 \left( \frac{R{\min, ij}}{r{ij}} \right)^6 \right] ] Here, ( \epsilon{ij} ) is the well depth, ( R{\min, ij} ) is the distance at which the potential is minimum, and ( r{ij} ) is the distance between atoms ( i ) and ( j ). The ( r^{-12} ) term describes repulsion, while the ( r^{-6} ) term describes attraction.

Electrostatic Interactions: These long-range forces arise from the attraction between partial charges on different atoms. They are modeled using Coulomb's law [5] [6]: [ E{\text{electrostatic}} = \sum{i \neq j} \frac{qi qj}{4\pi\varepsilon0 r{ij}} ] Here, ( qi ) and ( qj ) are the partial charges on atoms ( i ) and ( j ), ( r{ij} ) is their separation, and ( \varepsilon0 ) is the vacuum permittivity. The accurate assignment of atomic partial charges is critical, as this term often dominates the potential energy, especially in polar systems and ionic compounds [5].

Table 1: Summary of Standard Force Field Potential Energy Functions

| Interaction Type | Standard Functional Form | Key Parameters |

|---|---|---|

| Bond Stretching | ( E = \frac{k{ij}}{2}(l{ij} - l_{0,ij})^2 ) | Force constant ( k{ij} ), equilibrium length ( l{0,ij} ) |

| Angle Bending | ( E = \frac{k{\theta{ijk}}}{2}(\theta{ijk} - \theta{0,ijk})^2 ) | Force constant ( k{\theta{ijk}} ), equilibrium angle ( \theta_{0,ijk} ) |

| Dihedral Torsion | ( E = k{\chi{ijkl}} (1 + \cos(n\chi_{ijkl} - \delta)) ) | Force constant ( k{\chi{ijkl}} ), multiplicity ( n ), phase ( \delta ) |

| Van der Waals | ( E = \epsilon{ij} \left[ \left( \frac{R{\min, ij}}{r{ij}} \right)^{12} - 2 \left( \frac{R{\min, ij}}{r_{ij}} \right)^6 \right] ) | Well depth ( \epsilon{ij} ), minimum distance ( R{\min, ij} ) |

| Electrostatics | ( E = \frac{qi qj}{4\pi\varepsilon0 r{ij}} ) | Partial atomic charges ( qi ), ( qj ) |

Force Field Parameterization

Parameterization is the process of determining the numerical values for the force field parameters (e.g., ( l{0,ij} ), ( k{ij} ), ( q_i )), and it is crucial for the accuracy and reliability of the model [5]. This process involves several key concepts and methodologies.

The Concept of Atom Typing

A foundational principle in transferable force fields is atom typing. Instead of treating every atom of an element as identical, atoms are assigned a "type" based on their element, hybridization state, and local chemical environment [8]. For example, an oxygen atom in a carbonyl group and an oxygen atom in a hydroxyl group would be assigned different atom types with distinct parameters [5]. This allows the force field to more accurately capture the physics of different chemical functionalities.

Parameterization Strategies and Workflows

The parameters for a force field can be derived from experimental data, high-level quantum mechanical (QM) calculations, or a hybrid approach that combines both [5] [9].

- Quantum Mechanical Data: Ab initio QM calculations can provide high-quality data on molecular geometries, conformational energies, and electrostatic potentials. This data is used to fit parameters for bonded terms (bond lengths, angles, torsions) and to assign partial atomic charges, for example, by fitting to the electrostatic potential (ESP) [5] [6].

- Experimental Data: Macroscopic experimental properties, such as liquid densities, enthalpies of vaporization, and free energies of solvation, are used to refine parameters, particularly for nonbonded interactions (Lennard-Jones and electrostatic terms) [5] [9]. This ensures the force field reproduces key bulk properties.

Modern parameterization often employs systematic, automated optimization algorithms. A prominent example is the ForceBalance method, which optimizes parameters by minimizing a weighted objective function that quantifies the difference between simulated properties and reference data (both QM and experimental) [9]. This method can efficiently handle parameter interdependencies and uses thermodynamic fluctuation formulas to compute parametric derivatives of properties without running multiple expensive simulations [9].

The following diagram illustrates a generalized automated parameterization workflow.

Advanced Force Field Types

While traditional "additive" force fields use fixed partial charges, more advanced models are being developed to address their limitations.

Polarizable Force Fields: A key limitation of additive force fields is the lack of explicit electronic polarizability—the ability of a molecule's electron cloud to distort in response to its local electric field [6]. Additive force fields attempt to account for this implicitly by using enhanced, "effective" charges, but this approach fails in environments of differing polarity (e.g., when a ligand moves from aqueous solution to a protein binding pocket) [6]. Polarizable force fields explicitly model this response, leading to a more physical representation. One common approach is the Drude oscillator model (or induced dipole model), where a charged dummy particle (Drude particle) is attached to each atom by a spring, allowing the dipole moment to fluctuate [6]. These force fields show improved accuracy in simulating ion permeation, protein-ligand binding, and interactions at lipid-water interfaces [6].

Reactive Force Fields: Most standard force fields cannot model chemical reactions because their harmonic bond potentials do not allow for bond breaking and formation. Reactive force fields (such as ReaxFF) address this by using bond-order formalisms, where the strength of a bond and its associated parameters depend on the local geometry, enabling dynamic changes in connectivity during a simulation [5] [10].

Machine-Learned Force Fields (MLFFs): MLFFs represent a paradigm shift. They use machine learning models (e.g., neural networks) trained directly on high-quality QM data to predict the potential energy and forces of a system [11]. The VASP software, for instance, implements on-the-fly MLFFs where a Bayesian-learning algorithm is used during an MD simulation. If the uncertainty in the force prediction exceeds a threshold, an ab initio QM calculation is triggered, and the new data is used to update the MLFF, iteratively improving its accuracy and reliability [11]. This approach aims to achieve the accuracy of QM at a fraction of the computational cost.

Table 2: Comparison of Additive and Advanced Force Fields

| Feature | Additive (Non-polarizable) | Polarizable (e.g., Drude) | Machine-Learned (MLFF) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electrostatics | Fixed partial atomic charges | Fluctuating dipoles (inducible) | Learned from QM electron density |

| Bond Breaking | Not possible (harmonic bonds) | Not typically possible | Possible (depending on training) |

| Computational Cost | Low | ~5x higher than additive [9] | Variable (high training, lower inference) |

| Primary Data Source | Experiment & QM | High-level QM | Ab initio QM calculations |

| Key Advantage | Speed, stability for MD | Physical accuracy in different environments | High QM-level accuracy |

| Key Challenge | Implicit treatment of polarization | Parameter complexity, cost | Transferability, computational demand |

Essential Research Reagents and Software

Table 3: Essential Resources for Force Field Application and Development

| Resource / Tool | Type | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| CHARMM General FF (CGenFF) [6] | Transferable Additive Force Field | Parameters for drug-like molecules compatible with CHARMM biomolecular FFs. |

| General AMBER FF (GAFF) [6] | Transferable Additive Force Field | Parameters for small organic molecules compatible with AMBER biomolecular FFs. |

| Merck Molecular FF (MMFF94) [8] | Transferable Additive Force Field | Well-parameterized for small, drug-like molecules; often used for ligand geometry optimization. |

| OPLS-AA/OPLS5 [6] [12] | Transferable Additive/Polarizable FF | Widely used force field for proteins, organic liquids, and drug discovery (e.g., in FEP+). |

| ForceBalance [9] | Parameterization Software | Automated, systematic tool for optimizing force field parameters against reference data. |

| NIST IPR [10] | Force Field Database | Repository of interatomic potentials, particularly for metals, semiconductors, and ceramics. |

| AnteChamber [6] | Parameter Assignment Tool | Automated tool for generating GAFF/AMBER topologies and parameters for new molecules. |

| ParamChem [6] | Parameter Assignment Tool | Web-based service for generating CGenFF/CHARMM topologies and parameters for new molecules. |

| OpenMM [9] [7] | MD Simulation Engine | High-performance, GPU-accelerated toolkit for running molecular dynamics simulations. |

Protocol for Force Field Parameterization

The following is a generalized protocol for parameterizing a new molecule within an existing transferable force field framework, reflecting modern best practices [9] [6].

Initial Structure and Atom Typing:

- Obtain a 3D molecular structure from a database or via quantum chemical geometry optimization.

- Use an automated tool (e.g., ParamChem for CGenFF or AnteChamber for GAFF) to assign atom types based on the chemical structure and connectivity.

Parameter Assignment:

- The automated tool will assign initial parameters for all bonds, angles, dihedrals, and partial charges. These are typically based on analogy to existing parameters in the force field's database.

- Carefully review the assigned parameters, paying special attention to dihedral terms and partial charges, as these are often the greatest sources of error and require refinement.

Target Data Selection:

- Gather high-quality target data for optimization. This should include:

- Quantum Mechanical Data: Conformational energies, torsional energy profiles, and electrostatic potential (ESP) maps derived from QM calculations (e.g., at the DFT or MP2 level of theory).

- Experimental Data: Liquid properties such as density (( \rho )) and enthalpy of vaporization (( \Delta H_{vap} )), if available.

- Gather high-quality target data for optimization. This should include:

Iterative Optimization and Validation:

- Employ an optimization system like ForceBalance. The objective function ( O(p) ) to be minimized is often of the form: [ O(p) = \sum{i} wi \left( \frac{X{i}^{\text{sim}}(p) - X{i}^{\text{ref}}}{\sigmai} \right)^2 + R(p) ] where ( p ) are the parameters, ( X{i}^{\text{sim}} ) and ( X{i}^{\text{ref}} ) are the simulated and reference properties, ( wi ) is a weight, ( \sigma_i ) is the uncertainty in the reference data, and ( R(p) ) is a regularization term to prevent overfitting [9].

- The optimization loop involves running simulations, comparing results to target data, and updating parameters until convergence is achieved.

- Crucially, validate the final parameters against a set of experimental data that was not included in the training set (e.g., free energy of solvation, viscosity, or NMR observables) to ensure the model's transferability and robustness.

Force fields are the fundamental engine that powers molecular dynamics research, translating atomic coordinates into forces and energies that drive simulated motion. The choice and quality of the force field directly determine the physical realism and predictive power of the simulation. The field is dynamic, with ongoing research focused on improving accuracy through polarizable models, extending applicability through systematic parameterization tools like ForceBalance, and pushing the boundaries of efficiency and accuracy with machine-learned potentials. For researchers engaged in atomic motion tracking, a deep understanding of force field construction, limitations, and application protocols is not merely beneficial—it is essential for producing rigorous, reliable, and interpretable scientific results.

The genesis of computational physics and the theoretical foundations of modern molecular dynamics (MD) share a common origin: a numerical experiment on a nonlinear string conducted in 1953 by Enrico Fermi, John Pasta, Stanislaw Ulam, and Mary Tsingou [13] [14]. What began as a study of thermalization in solids has evolved into a rich field of nonlinear physics that underpins our understanding of atomic-scale dynamics in complex biomolecular systems. The Fermi-Pasta-Ulam-Tsingou (FPUT) problem represents one of the earliest uses of digital computers for mathematical research and simultaneously launched the study of nonlinear systems [13]. This historical journey from the FPUT paradox to contemporary biomolecular simulation represents more than a chronological progression; it embodies the evolution of our conceptual understanding of how energy flows and distributes in complex many-body systems—a fundamental question that remains central to interpreting MD trajectories in computational biology and drug design.

The core insight connecting these seemingly disparate fields lies in their shared physical and mathematical foundations. Both involve solving Newton's equations of motion for complex, nonlinear systems—whether for a one-dimensional string or a massive biomolecule comprising hundreds of thousands of atoms [15]. The FPUT problem revealed unexpected behavior in such systems, while modern MD simulations leverage these insights to predict the behavior of biological macromolecules with remarkable accuracy. This article traces this intellectual and technical lineage, examining how a foundational paradox in statistical mechanics paved the way for computational tools that now drive innovation in drug development and materials science.

The FPUT Problem: A Paradigm Shift in Nonlinear Physics

The Original Experiment and Its Unexpected Outcome

In the summer of 1953, Fermi, Pasta, Ulam, and Tsingou conducted computer simulations on the MANIAC computer at Los Alamos National Laboratory to study how energy distributes in a nonlinear system [13]. Their model consisted of a one-dimensional chain of 64 mass points connected by springs with nonlinear forces, governed by the discrete equation of motion:

[ m\ddot{x}j = k(x{j+1} + x{j-1} - 2xj)[1 + \alpha(x{j+1} - x{j-1})] ]

where (x_j(t)) represents the displacement of the j-th particle from its equilibrium position, and α controls the strength of the nonlinear quadratic term [13]. The team also studied cubic (β) and piecewise linear approximations.

Fermi and colleagues expected that the nonlinear interactions would cause the system to thermalize rapidly, with energy eventually distributed equally among all vibrational modes according to the equipartition theorem of statistical mechanics [13] [16]. Contrary to these expectations, their simulations revealed a remarkably different behavior: instead of thermalizing, the system exhibited complicated quasi-periodic behavior with near-recurrences to the initial state—a phenomenon now known as FPUT recurrence [13] [14]. This apparent paradox challenged fundamental assumptions about statistical mechanics and ergodicity, showing that even with nonlinear interactions, the system did not necessarily behave ergodically over computationally accessible timescales.

Mathematical Formulations and Key Concepts

The FPUT problem can be formulated through several mathematical frameworks that have proven essential for understanding its behavior:

- α-FPUT Model: Features a cubic potential, (V_α(r) = \frac{r^2}{2} + \frac{α}{3}r^3), providing asymmetric nonlinearity [16].

- β-FPUT Model: Employs a quartic potential, (V_β(r) = \frac{r^2}{2} + \frac{β}{4}r^4), creating symmetric nonlinearity [16].

- Normal Mode Transformation: The transformation ( \left( \begin{array}{c} qn \ pn \end{array} \right) = \sqrt{\frac{2}{N+1}} \sum{k=1}^N \left( \begin{array}{c} Qk \ P_k \end{array} \right) \sin \left( \frac{nk\pi}{N+1} \right) ) diagonalizes the harmonic lattice but leaves coupling terms in the presence of nonlinearities [16].

- Connection to Integrable Systems: The α-FPUT model can be viewed as a truncation of the Toda lattice, which has the potential (V{\text{Toda}}(r) = V0[e^{λr} - 1 - λr]) and is completely integrable [16].

Table 1: Key Models in the FPUT Paradigm

| Model | Potential Energy | Nonlinearity Type | Key Properties |

|---|---|---|---|

| Harmonic | (\frac{r^2}{2}) | Linear | Exactly solvable, no energy sharing |

| α-FPUT | (\frac{r^2}{2} + \frac{α}{3}r^3) | Cubic, asymmetric | Truncation of Toda lattice |

| β-FPUT | (\frac{r^2}{2} + \frac{β}{4}r^4) | Quartic, symmetric | Not a truncation of integrable system |

| Toda Lattice | (V_0(e^{λr} - 1 - λr)) | Exponential | Completely integrable, soliton solutions |

The discovery of the FPUT recurrence phenomenon prompted six decades of research into nonlinear systems, leading to groundbreaking developments including soliton theory [13] [17], chaos theory [14], and wave turbulence theory [14]. The connection to the Korteweg-de Vries (KdV) equation through the continuum limit was particularly significant, as it revealed the existence of soliton solutions—special waves that maintain their shape while propagating [13].

From Nonlinear Strings to Atomic Simulations: The Emergence of Molecular Dynamics

Fundamental Principles of Molecular Dynamics

Molecular dynamics simulations track the motion of individual atoms and molecules over time by numerically solving Newton's equations of motion for complex many-body systems [18]. Often described as a "microscope with exceptional resolution," MD provides atomic-scale insights into physical and chemical processes that are difficult or impossible to observe experimentally [18]. The core principles of MD directly extend the conceptual framework established by the FPUT problem—both involve understanding how energy distributes and dynamics evolve in nonlinear systems with many degrees of freedom.

The mathematical foundation of MD relies on Newton's second law applied to each atom i in a system:

[ mi \frac{d^2\mathbf{r}i}{dt^2} = \mathbf{F}i = -\nablai U(\mathbf{r}1, \mathbf{r}2, ..., \mathbf{r}_N) ]

where (mi) is the atomic mass, (\mathbf{r}i) is the position vector, (\mathbf{F}_i) is the force acting on the atom, and (U) is the potential energy function describing interatomic interactions [18]. This system of coupled differential equations is structurally similar to the FPUT lattice equations, though dramatically more complex in dimensionality and interaction potentials.

The MD Workflow: From Initial Conditions to Analysis

The standard workflow for MD simulations comprises several well-defined stages, each with its own technical considerations:

Initial Structure Preparation: The process begins with preparing the initial atomic coordinates, often obtained from crystallographic databases (e.g., Protein Data Bank for biomolecules) or built from scratch for novel materials [18].

System Initialization: Initial velocities are assigned to all atoms, typically sampled from a Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution corresponding to the desired simulation temperature [18].

Force Calculation: This computationally intensive step determines forces between atoms based on interatomic potentials. Modern approaches include machine learning interatomic potentials (MLIPs) trained on quantum chemistry data [18] [15].

Time Integration: Using algorithms like Verlet or leap-frog, the equations of motion are solved numerically to update atomic positions and velocities. Time steps typically range from 0.5 to 1.0 femtoseconds to accurately capture the fastest atomic motions [18].

Trajectory Analysis: The resulting time-series data of atomic positions and velocities are analyzed to extract physically meaningful insights, such as structural properties, dynamics, and thermodynamic quantities [18].

Figure 1: Molecular Dynamics Simulation Workflow

Technical Parallels: FPUT Concepts in Modern Biomolecular Simulation

Metastable States and the Timescale Problem

The FPUT problem introduced the concept of metastable states—quasi-stationary states that delay the approach to thermal equilibrium [16]. In the FPUT context, this metastable state is characterized by the system remaining localized in mode space for unexpectedly long durations, exhibiting recurrences to the initial condition instead of rapid thermalization [16]. This phenomenon finds direct parallels in biomolecular simulations, where systems often become trapped in metastable conformational states for timescales that challenge computational resources.

In FPUT systems, researchers have quantified the lifetime of metastable states ((t_m)) using measures like spectral entropy (η) to track the distance from equipartition [16]. Similarly, in biomolecular simulations, analysis techniques like Markov state models are employed to identify and characterize metastable states and transitions between them. The FPUT recurrence timescale has been shown to follow power-law scaling with system parameters [16], analogous to the timescale problems encountered in simulating rare events in biomolecular dynamics, such as protein folding or ligand unbinding.

Energy Transfer and Equipartition

The original FPUT study fundamentally questioned the applicability of the equipartition theorem to nonlinear systems—a concern that remains relevant in modern MD. In FPUT systems, energy initially concentrated in low-frequency modes unexpectedly fails to distribute equally among all modes over computationally accessible timescales [13] [16]. In biomolecular simulations, similar issues manifest as difficulties in achieving proper thermalization or as non-ergodic behavior where certain regions of phase space are inadequately sampled.

Table 2: Quantitative Measures in FPUT and MD Simulations

| Property | FPUT Context | Biomolecular MD Context | Measurement Technique |

|---|---|---|---|

| Energy Distribution | Mode energies (E_k) | Potential energy terms | Normal mode analysis, energy decomposition |

| Timescales | Recurrence time (T_R) | Correlation times, folding times | Autocorrelation functions, Markov models |

| Metastability | Spectral entropy η | Free energy landscapes | Principal component analysis, MSMs |

| Thermalization | Approach to equipartition | Temperature equilibration | Thermostat coupling, kinetic temperature |

| Nonlinearity | α, β parameters | Force field anharmonic terms | Potential energy surface analysis |

Research has shown that the route to thermalization in FPUT systems occurs through specific resonance mechanisms, particularly four-wave and six-wave resonances as described by wave turbulence theory [14] [16]. These findings have implications for understanding how energy flows in biomolecules—for instance, how vibrational energy from ATP hydrolysis might propagate through specific channels in enzymes or how allosteric signals are transmitted through protein structures.

The Modern Biomolecular Simulation Toolkit

Advanced Force Fields and Nuclear Quantum Effects

Contemporary biomolecular simulations rely on sophisticated force fields that accurately represent interatomic interactions. The Arrow force field represents a significant advancement as it is parameterized entirely using quantum mechanical calculations without reliance on experimental data [15]. This ab initio approach achieves chemical accuracy (∼0.5 kcal/mol) for neutral organic compounds in the liquid phase, enabling reliable prediction of properties like solvation free energies and partition coefficients [15].

Key innovations in modern force fields include:

- Polarizability: Modeling how atomic charge distributions respond to their environment, enabling transferability from gas to liquid phase [15].

- Charge Penetration Effects: Accounting for the overlap of electron clouds between nearby atoms [15].

- Anisotropic Atomic Shapes: Representing the directional nature of atomic interactions beyond simple spheres [15].

- Nuclear Quantum Effects (NQE): Modeling quantum mechanical behavior of atomic nuclei using techniques like ring polymer MD, which is particularly important for simulating hydrogen bonding and proton transfer reactions [15].

The inclusion of NQE has proven essential for achieving accurate free energy predictions, bringing computational results into excellent agreement with experimental measurements for various molecular systems [15].

Specialized Simulation Techniques

Modern biomolecular simulation employs specialized methodologies to address specific scientific questions:

- Enhanced Sampling Methods: Techniques like metadynamics, replica exchange, and accelerated MD overcome timescale limitations by promoting transitions between metastable states [19].

- Free Energy Calculations: Methods such as thermodynamic integration and free energy perturbation provide quantitative predictions of binding affinities and partition coefficients crucial for drug design [15].

- Multiscale Simulations: QM/MM approaches combine quantum mechanical accuracy for a reaction center with molecular mechanics efficiency for the surrounding environment [15].

- Machine Learning Potentials: MLIPs trained on quantum chemistry datasets enable accurate simulations of complex material systems that were previously computationally prohibitive [18].

Figure 2: Advanced Biomolecular Simulation Techniques

Applications in Drug Discovery and Materials Science

Biomolecular Applications

Molecular dynamics simulations have become indispensable tools in pharmaceutical research and development. A recent study on uncoupling protein 1 (UCP1) illustrates the power of MD simulations to elucidate biological mechanisms at atomic resolution [20]. Researchers employed all-atom MD simulations combined with membrane conductance measurements and site-directed mutagenesis to identify novel pathways for fatty acid anion translocation at the UCP1 protein-lipid interface [20]. This work revealed how key arginine residues (R84 and R183) form stable complexes with fatty acid anions, facilitating transport essential for mitochondrial thermogenesis.

Additional biomolecular applications include:

- Protein-Ligand Binding: Predicting binding modes and affinities for drug candidates [15].

- Membrane Permeability: Studying how molecules traverse lipid bilayers [20].

- Allosteric Regulation: Identifying long-range communication pathways in proteins [18].

- Drug Solubility and Formulation: Predicting solvation free energies and partition coefficients [15].

Materials and Industrial Applications

Beyond biomedicine, MD simulations drive innovation in materials science and industrial processes:

- Ion Conductivity: Analyzing diffusion mechanisms in solid electrolytes for battery applications [18].

- Mechanical Properties: Computing stress-strain relationships and predicting yield strength in structural materials [18].

- Phase Behavior: Studying crystallization, glass formation, and phase transitions [18].

- Nanomaterial Design: Understanding self-assembly and properties of nanostructured materials [18].

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function | Relevance to FPUT Concepts |

|---|---|---|---|

| Force Fields | AMBER, CHARMM, Arrow FF | Define interatomic potentials | Nonlinear interaction potentials |

| Analysis Software | MDAnalysis, VMD, GROMACS | Process MD trajectories | Mode analysis, recurrence quantification |

| Enhanced Sampling | PLUMED, MetaD | Accelerate rare events | Metastable state characterization |

| Quantum Calibration | DFT, CCSD(T) | Generate training data for ML potentials | Connection to fundamental physics |

| Structure Databases | PDB, Materials Project | Provide initial configurations | Initial condition dependence |

Future Perspectives: FAIR Principles and Next-Generation Simulations

The biomolecular simulation community is currently embracing the FAIR principles (Findability, Accessibility, Interoperability, and Reusability) to transform research practices [17]. A recent initiative signed by 128 researchers advocates for creating a comprehensive database for MD simulation data, aiming to democratize the field and enhance the impact of simulations on life science research [17]. This development represents a natural evolution from the early days of computational science exemplified by the FPUT problem—where each simulation was a unique, barely reproducible effort—toward a future of open, collaborative, and cumulative science.

Future directions in biomolecular simulation include:

- Integration with AI and Machine Learning: Leveraging deep learning for structure prediction, force field development, and analysis of high-dimensional data [18] [15].

- Exascale Computing: Harnessing next-generation supercomputers to access biologically relevant timescales and system sizes [17].

- Automated Workflows: Developing streamlined protocols for non-experts to perform reliable simulations [18].

- Experimental Validation and Integration: Strengthening connections between simulation predictions and experimental observables [20].

The intellectual journey from the Fermi-Pasta-Ulam problem to modern biomolecular simulation demonstrates how fundamental research into basic principles of nonlinear systems can yield transformative practical applications. What began as a numerical experiment on a simple nonlinear string has evolved into a sophisticated computational framework that provides unprecedented insights into biological processes at atomic resolution. The FPUT problem introduced conceptual challenges—metastable states, limited ergodicity, and the importance of nonlinear resonances—that continue to resonate in contemporary MD simulations of biomolecules.

As simulation methodologies advance, incorporating more accurate physical models, machine learning approaches, and FAIR data principles, the legacy of the FPUT problem endures in our continued fascination with understanding how energy flows and distributes in complex systems. This historical continuum, stretching from Fermi's vision to today's cutting-edge biomolecular simulations, underscores the enduring value of foundational research in shaping the scientific tools of tomorrow—tools that are increasingly essential for addressing challenges in drug discovery, materials science, and beyond.

The ergodic hypothesis is a foundational principle in statistical mechanics that links the microscopic dynamics of atoms and molecules to the macroscopic thermodynamic properties we observe. This hypothesis states that, over long periods, the time a system spends in any region of its phase space is proportional to the volume of that region [21]. In practical terms, this means that all accessible microstates with the same energy are equally probable over a sufficiently long timeframe. For researchers tracking atomic motion in molecular dynamics, this principle provides the crucial justification for using statistical ensembles to predict molecular behavior. The profound implication is that the time average of a property for a single system equates to the average of that property across an ensemble of identical systems at one instant [22]. This equivalence enables scientists to extract meaningful thermodynamic information from the chaotic motion of individual atoms, forming the theoretical bedrock for molecular dynamics simulations and atomic motion tracking research.

Within the context of molecular dynamics and atomic motion tracking, ergodicity provides the mathematical justification for why simulating a single system over time can yield the same statistical properties as studying multiple identical systems simultaneously. This is particularly vital in drug development and materials science, where researchers must predict bulk behavior from limited simulation data. The hypothesis, first proposed by Boltzmann in the late 19th century, remains intensely relevant today as advanced experimental techniques like ultrafast X-ray scattering and computational methods enable unprecedented tracking of individual atomic motions [23] [24].

Core Theoretical Framework

Time Averages vs. Ensemble Averages

In statistical mechanics, two distinct averaging methods provide the connection between microscopic dynamics and macroscopic observables:

Time Average: The average value of a property obtained from tracking a single system over an extended period. For an observable ( f ), this is mathematically expressed as ( \overline{f} = \lim{T \to \infty} \frac{1}{T} \int0^T f(x(t)) dt ) [22]. In molecular dynamics research, this corresponds to tracking atomic positions and energies throughout a simulation trajectory.

Ensemble Average: The average value of a property across a theoretical collection (ensemble) of identical systems at a specific moment, expressed as ( \langle f \rangle = \int f(x) \rho(x) dx ), where ( \rho(x) ) represents the probability density in phase space [22]. This approach is used when analyzing multiple parallel simulations or experimental replicates.

The ergodic hypothesis fundamentally asserts the equivalence of these two averages: ( \overline{f} = \langle f \rangle ) [22]. For molecular dynamics researchers, this equivalence means that sufficiently long simulations of a single molecular system can provide the same statistical information as studying multiple identical systems simultaneously—a crucial justification for the methodology underpinning computational drug design and materials science.

Mathematical Formulation

The mathematical rigor behind ergodicity is established through several key theorems:

Birkhoff's Ergodic Theorem (1931) provides the formal foundation, stating that for measure-preserving dynamical systems, the time average of a function along trajectories equals the space average for almost all starting points [22]. Mathematically, this is expressed as ( \lim{T \to \infty} \frac{1}{T} \int0^T f(T^t x) dt = \int f(x) d\mu(x) ), where ( \mu ) represents the invariant measure.

Liouville's Theorem further supports this framework by establishing that for Hamiltonian systems, the local density of microstates following a particle path through phase space remains constant [21]. This conservation property implies that if microstates are uniformly distributed initially, they remain so over time, providing a mathematical basis for the equal probability of accessible states.

The following diagram illustrates the conceptual relationship between these averaging methods in ergodic systems:

Ergodicity in Molecular Dynamics and Atomic Motion Tracking

Computational Validation Through Molecular Dynamics

Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations serve as the primary computational tool for testing and leveraging ergodic principles in studying atomic-scale phenomena. These simulations apply Newton's laws of motion to model molecular behavior over time, with discrete time steps typically on the femtosecond scale ((10^{-15}) seconds) to capture atomic vibrations and movements [25]. The connection to ergodicity emerges through the simulation ensembles employed:

Table 1: Molecular Dynamics Ensembles and Their Relation to Ergodicity

| Ensemble Type | Conserved Quantities | Connection to Ergodicity | Primary Research Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| NVE (Microcanonical) | Number of particles (N), Volume (V), Energy (E) | Directly corresponds to isolated systems exploring constant-energy surface; fundamental test of ergodic hypothesis | Gas-phase simulations, molecular reactions, fundamental validation studies |

| NVT (Canonical) | Number of particles (N), Volume (V), Temperature (T) | Ergodic exploration of states at fixed temperature; enables comparison with experimental conditions | Biological systems at physiological conditions, protein folding studies |

| NPT (Isothermal-Isobaric) | Number of particles (N), Pressure (P), Temperature (T) | Ergodic sampling under constant pressure and temperature; mimics common laboratory conditions | Liquid simulations, large biomolecular systems, materials design |

MD simulations validate ergodicity by demonstrating that time averages of properties like energy, pressure, and molecular conformation converge to ensemble averages over sufficiently long simulation times [25]. This convergence is particularly crucial in drug discovery, where researchers simulate drug-protein binding events and rely on ergodic sampling to ensure adequate exploration of conformational space for accurate binding affinity predictions.

Experimental Validation Through Advanced Atomic Tracking

Recent experimental breakthroughs in tracking atomic and electronic motion provide striking validation of ergodic principles:

In a landmark study at SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, researchers used ultrafast X-ray laser pulses from the Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS) to track the motion of a single valence electron during the dissociation of hydrogen from an ammonia molecule [23]. The experimental protocol involved:

- Sample Preparation: Creating an enclosure of high-density ammonia gas

- Photoexcitation: Using an ultraviolet laser pulse to initiate the chemical reaction

- Probing: Scattering X-rays from LCLS off electrons during the reaction

- Data Collection: Capturing the scattered X-rays to reconstruct electron positions

- Theoretical Validation: Comparing results with advanced quantum simulations

The entire process occurred within 500 femtoseconds, capturing the electron rearrangement that drives nuclear repositioning [23]. This direct observation of electron motion throughout a complete reaction pathway demonstrates the fundamental principle that molecular systems explore accessible states over time—a core requirement for ergodic behavior.

Complementary research at the Max Planck Institute has developed techniques to track atomic motion in single graphene nanoribbons using femtosecond coherent anti-Stokes Raman spectroscopy (CARS) within a scanning tunneling microscope (STM) [24]. This approach can track atomic motions on timescales as short as 70 femtoseconds, providing direct experimental observation of phase space exploration in nanoscale systems.

Ergodicity Breaking and Modern Research Applications

When Ergodicity Fails: Limitations and Broken Ergodicity

Despite its foundational status, the ergodic hypothesis has well-established limitations. Ergodicity breaking occurs when systems fail to explore their entire accessible phase space within observable timescales [21] [22]. Notable examples include:

- Glassy Systems: Structural glasses, spin glasses, and polymers exhibit extremely slow relaxation times due to complex energy landscapes with many local minima [22]. These systems remain trapped in non-equilibrium states for experimentally relevant timescales.

- Spontaneous Symmetry Breaking: Ferromagnetic materials below the Curie temperature maintain non-zero magnetization instead of exploring all possible states [21].

- Biological Systems: Large biomolecules like proteins may have folding timescales exceeding practical simulation times, leading to inadequate sampling [25].

The Fermi-Pasta-Ulam-Tsingou experiment of 1953 provided an early surprising counterexample, where a nonlinear system failed to equilibrate as expected [21]. Instead of energy equipartition, the system exhibited recurrent behavior with energy returning to initial modes—a direct violation of ergodic expectations that led to the discovery of solitons.

Implications for Drug Development and Molecular Design

For pharmaceutical researchers, understanding ergodicity and its limitations has profound practical implications:

- Drug Binding Calculations: Molecular dynamics simulations of drug-receptor interactions rely on ergodic sampling to accurately compute binding free energies. Inadequate sampling caused by ergodicity breaking can lead to inaccurate predictions of drug efficacy [25].

- Protein Folding Studies: The prediction of protein structure from sequence depends on the assumption that simulations can explore the relevant conformational space. Non-ergodic behavior in folding pathways presents significant challenges for reliable prediction [25].

- Enhanced Sampling Methods: Techniques like metadynamics and replica exchange are specifically designed to address ergodicity breaking by encouraging systems to overcome energy barriers and explore wider regions of phase space [25].

Recent computational advancements address these challenges through massive datasets like Open Molecules 2025 (OMol25), which contains over 100 million 3D molecular snapshots calculated with density functional theory [26]. This unprecedented resource, representing six billion CPU hours of computation, enables training machine learning interatomic potentials that can simulate systems with up to 350 atoms across most of the periodic table, dramatically improving ergodic sampling for complex molecular systems [26].

Experimental Protocols and Research Tools

Key Experimental Methodologies

Cutting-edge experimental techniques for tracking atomic and electronic motion employ sophisticated protocols to validate ergodic principles:

Ultrafast X-ray Scattering Protocol [23]:

- Sample Preparation: Purified molecular samples (e.g., ammonia) are prepared in high-density gas phase or thin-film environments

- Pump Laser Excitation: Ultraviolet laser pulses (typically 100-400 nm) initiate photochemical reactions with precise temporal control

- X-ray Probing: Femtosecond X-ray pulses from free-electron lasers scatter from electron clouds

- Detection: Area detectors capture diffraction patterns with single-shot capability

- Data Reconstruction: Computational algorithms transform time-resolved diffraction into real-space electron density maps

- Theoretical Comparison: Advanced quantum simulations validate interpretations of electron dynamics

STM-CARS Protocol for Atomic Tracking [24]:

- Sample Fabrication: Nanoscale materials (e.g., graphene nanoribbons) are synthesized on atomically flat substrates

- Laser Excitation: Two time-delayed broadband laser pulses generate vibrational wave packets

- STM Detection: Scanning tunneling microscope tips detect local electronic changes induced by atomic motion

- Signal Processing: Coherent anti-Stokes Raman spectroscopy extracts specific vibrational frequencies

- Atomic Reconstruction: Position-dependent signals are reconstructed into time-resolved atomic trajectories

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Atomic Motion Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function in Research | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Ultrafast Laser Systems | Generate femtosecond optical pulses for initiating and probing reactions | Pump-probe spectroscopy, coherent control experiments |

| X-ray Free Electron Lasers | Provide intense, femtosecond X-ray pulses for scattering experiments | Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS), European XFEL facilities |

| Scanning Tunneling Microscopes | Atomic-scale imaging and local spectroscopy | Single-molecule studies, surface science, nanomaterial characterization |

| High-Purity Molecular Samples | Ensure reproducible experimental conditions with minimal impurities | Ammonia for dissociation studies, custom-synthesized organic molecules |

| Cryogenic Cooling Systems | Reduce thermal noise and stabilize fragile quantum states | Helium flow cryostats, closed-cycle refrigerators |

| Ultrahigh Vacuum Chambers | Create pristine environments free from contamination | Surface science experiments, single-molecule tracking |

| Quantum Chemistry Software | Perform advanced simulations for experimental interpretation | Density functional theory, ab initio molecular dynamics |

Future Directions and Research Frontiers

The integration of ergodic principles with emerging technologies is creating new research frontiers:

Machine Learning-Enhanced Molecular Dynamics leverages neural network potentials trained on massive datasets like OMol25 to achieve accurate simulations at dramatically reduced computational cost, effectively improving ergodic sampling for complex systems [26] [25]. These approaches can predict molecular properties with density functional theory accuracy while being thousands of times faster, enabling previously impossible simulations of biologically relevant systems.

Quantum-Classical Hybrid Methods combine quantum mechanical accuracy with classical simulation efficiency, particularly important for studying processes like electron transfer and catalytic reactions where electronic structure changes drive atomic motion [25]. The recent experimental tracking of single electrons during chemical reactions provides crucial validation for these approaches [23].

Single-Molecule Experimental Techniques are increasingly capable of directly testing ergodic assumptions by tracking individual molecules over extended periods, revealing molecular heterogeneity that ensemble measurements average out [22]. These techniques are particularly valuable for studying biological systems where ergodicity breaking may have functional significance.

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow combining computational and experimental approaches in modern ergodicity research:

As these technologies mature, the ergodic hypothesis continues to provide the conceptual framework connecting nanoscale atomic motion to macroscopic observables, enabling researchers to design more effective drugs, novel materials, and advanced biomolecules through a fundamental understanding of molecular behavior across timescales.

The fidelity of a molecular dynamics (MD) simulation is fundamentally contingent upon the integrity of its initial setup. The processes of defining accurate initial structures, applying appropriate boundary conditions, and meticulously preparing the system constitute the foundational steps that determine the physical relevance and numerical stability of the entire simulation. Within the broader context of basic principles of molecular dynamics atomic motion tracking research, a rigorous setup is paramount for distinguishing physical phenomena from computational artifacts and for generating trajectories that can be meaningfully compared with experimental data. This guide details the core methodologies and current best practices for preparing MD simulations, with a focus on protocols relevant to researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

The initial atomic coordinates, or the starting structure, define the system's initial conformational state. The choice and preparation of this structure directly influence the simulation's equilibration time and the biological relevance of the sampled dynamics.

- Experimental Structures: The most reliable starting points are experimentally determined structures from databases such as the Protein Data Bank (RCSB PDB) [27]. These provide atomistic details of macromolecules but often require preprocessing to add missing residues, protons, or correct for unresolved loops.

- Previous Simulations: Structures obtained from previous MD simulations can be used as starting points for new simulations, for instance, to extend simulation time or to study a different thermodynamic state. A critical consideration in such cases is the handling of molecules that may cross the periodic box boundaries in the saved structure. It is often permissible to proceed, as periodic boundary conditions will correctly map atoms that exit the box to the opposite side, but verification of the system's integrity is necessary [28].

- De Novo and Homology Models: For targets without an experimental structure, computational models built through homology modeling (e.g., with MODELLER [27]) or other de novo methods are used. These require careful validation and often extensive equilibration.

Structure Preprocessing and Energy Minimization

Raw initial structures frequently contain steric clashes or geometrically unfavorable conformations. Energy minimization (EM) is a critical preprocessing step that adjusts atomic coordinates to find a local minimum on the potential energy surface, relieving these strains before dynamics begin [29].

The energy of a molecule is a function of its nuclear coordinates, and EM algorithms iteratively adjust these coordinates to reduce the net forces on the atoms. The general update formula is: xnew = xold + correction

Common minimization algorithms include [29]:

- Steepest Descent: A robust method for initial steps that moves atoms opposite the direction of the largest gradient. It is computationally inexpensive per step but can be slow to converge.

- Conjugate Gradient: A more efficient method that incorporates information from previous steps to avoid oscillation, leading to faster convergence towards the minimum.

Table 1: Key Energy Minimization Algorithms

| Method | Principle | Computational Cost | Typical Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Steepest Descent | Moves atoms against the largest force gradient | Low per step, but requires many steps | Initial minimization of poorly structured systems with steric clashes |

| Conjugate Gradient | Combines current gradient with previous search direction | Moderate per step, fewer steps than Steepest Descent | Refined minimization after initial Steepest Descent steps |

| Newton-Raphson | Uses first and second derivatives (Hessian) for high accuracy | Very high per step | Final precision minimization for small systems |

The following workflow outlines a standard procedure for obtaining and preparing an initial structure for simulation.

Boundary Conditions and System Definition

Boundary conditions (BCs) are a critical computational tool for simulating a small part of a much larger system, such as a solute in a continuous solvent, while avoiding unphysical surface effects.

Types of Boundary Conditions

- Periodic Boundary Conditions (PBC): PBCs are the most common approach in biomolecular simulations. The simulation box containing the solute and solvent is treated as a repeating unit cell in all three spatial dimensions. As a molecule moves and an atom exits the box through one face, it simultaneously re-enters the box through the opposite face [28]. This maintains a constant number of atoms and effectively models a bulk environment. Forces between atoms are calculated using minimum image conventions, where each atom interacts with the closest periodic image of every other atom.

- Isolated Boundary Conditions (IBC): Also known as vacuum or gas-phase BCs, this approach places the molecule in a vacuum without periodic images. It is less computationally intensive but ignores solvation effects, which can be critical for modeling biological processes. Its use is typically limited to gas-phase calculations or very initial testing [29].

Implementing Periodic Boundary Conditions

The following diagram illustrates the logic and consequences of applying PBCs in a molecular dynamics simulation, addressing a common challenge when using structures from previous simulations.

Integrated System Preparation Workflow

Preparing a solvated, neutralized, and energetically stable system for production MD is a multi-step process. Integrated web-based platforms like CHARMM-GUI have streamlined this workflow, providing a reproducible interface for building complex systems and generating input files for numerous simulation packages like GROMACS, AMBER, NAMD, and OpenMM [30]. The general protocol involves:

- Solvation: The preprocessed biomolecule is placed in a box of explicit solvent molecules, most commonly water models like TIP3P or SPC/E.

- Neutralization and Ion Concentration: Counterions (e.g., Na⁺, Cl⁻) are added to replace water molecules at positions of favorable electrostatic potential, first to neutralize the system's net charge, and then to achieve a physiologically relevant salt concentration.

- Final Energy Minimization and Equilibration: The fully assembled system undergoes a final round of energy minimization to relieve any steric strain introduced during solvation and ion placement. This is followed by a phased equilibration process, where positional restraints on the solute are gradually released while the solvent and ions relax around it.

Table 2: Key System Preparation Steps and Their Functions

| Preparation Step | Primary Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Solvation | Embeds the solute in a realistic chemical environment (e.g., aqueous solution) | Choice of water model; Box size and shape (e.g., cubic, rhombic dodecahedron) |

| Neutralization | Adds counterions to achieve a net zero charge for the system | Ion placement is based on solving the Poisson-Boltzmann equation to find favorable electrostatic locations |

| Ion Concentration | Adds salt ions to match experimental or physiological conditions (e.g., 150 mM NaCl) | Ionic strength affects biomolecular electrostatics and stability |

| Final Energy Minimization | Relieves atomic clashes introduced during the building process, especially between solute and solvent | A combination of Steepest Descent and Conjugate Gradient methods is typically used |

| Equilibration | Relaxes the system to the target temperature and density while preserving the solute's structure | Performed in stages with strong, then weak, positional restraints on the solute heavy atoms |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Software

The following table details key software tools and computational "reagents" essential for modern molecular dynamics research, particularly in drug development where understanding membrane permeability and ligand binding is crucial [31] [32] [27].

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for MD Simulation Setup

| Tool / Reagent | Category | Primary Function in Setup |

|---|---|---|

| RCSB PDB [27] | Data Repository | Source for experimentally determined initial atomic coordinates of proteins, nucleic acids, and complexes. |

| CHARMM-GUI [30] | Web-Based Platform | Streamlines system building: solvation, ion placement, lipid bilayer assembly, and input file generation for major MD engines. |

| AMBER [31] | MD Software Suite | Provides the LEaP module for system preparation and the PMEMD engine for GPU-accelerated dynamics and free energy calculations. |

| GROMACS [31] | MD Software Suite | A highly optimized, open-source package for MD simulation and analysis, known for exceptional performance on GPU hardware. |