Assessing the Accuracy of MD-Derived Thermodynamic Properties: A Guide for Computational Researchers and Drug Developers

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations have become an indispensable tool for predicting thermodynamic properties critical to drug design and materials science, such as binding free energy, entropy, and enthalpy.

Assessing the Accuracy of MD-Derived Thermodynamic Properties: A Guide for Computational Researchers and Drug Developers

Abstract

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations have become an indispensable tool for predicting thermodynamic properties critical to drug design and materials science, such as binding free energy, entropy, and enthalpy. However, the accuracy of these predictions is influenced by multiple factors, including force field choice, sampling adequacy, and the handling of quantum effects. This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals to critically assess and improve the reliability of their MD-derived thermodynamic data. We explore the fundamental principles connecting MD to thermodynamics, review advanced methodological approaches and their practical applications, outline key strategies for troubleshooting and optimizing simulations, and establish robust protocols for validation against experimental data. By synthesizing insights across these four core intents, this guide aims to empower scientists to generate more accurate, reproducible, and biologically meaningful thermodynamic predictions.

The Fundamental Link: How Molecular Dynamics Simulations Capture Thermodynamics

In rational drug design, the binding affinity between a small molecule (ligand) and its target protein is the crucial parameter determining a potential drug's efficacy [1]. This affinity is governed by the fundamental thermodynamic equation: ΔG = ΔH - TΔS, where ΔG represents the change in Gibbs free energy, ΔH is the change in enthalpy, and ΔS is the change in entropy [1] [2] [3]. A negative ΔG value indicates a spontaneous binding event, with more negative values signifying stronger binding [1]. However, this single number belies a complex interplay of forces; similar ΔG values can result from dramatically different combinations of ΔH and ΔS, a phenomenon known as enthalpy-entropy compensation [1] [3]. Understanding this balance is critical, as the thermodynamic signature of binding (whether it is enthalpically- or entropically-driven) provides deep insight into the nature of the molecular interactions and guides optimization strategies [3].

Experimental Methods for Measuring Binding Thermodynamics

Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC)

Methodology: ITC directly measures the heat released or absorbed during a binding event. In a typical experiment, sequential injections of a ligand solution are made into a sample cell containing the protein. The instrument measures the heat required to maintain a constant temperature between the sample and reference cells with each injection. A single experiment provides the binding constant (K~a~), which yields ΔG, alongside the enthalpy change (ΔH) and the stoichiometry of binding (N). The entropy change (ΔS) is then calculated from ΔG and ΔH [1].

Performance Context: ITC is often considered a "gold standard" for binding thermodynamics because it provides a complete thermodynamic profile from a single experiment without requiring labeling or immobilization [4] [1]. Its primary limitation is relatively high sample consumption and moderate throughput, though instrumentation continues to improve [1].

Thermal Shift Assay (TSA)

Methodology: Also known as Differential Scanning Fluorimetry (DSF), TSA is based on ligand-induced protein stabilization. The protein is heated in the presence and absence of a ligand, and a fluorescent dye (e.g., SYPRO Orange) binds to hydrophobic regions exposed as the protein unfolds. The midpoint of the unfolding transition, the melting temperature (T~m~), shifts (ΔT~m~) in the presence of a stabilizing ligand. This ΔT~m~ is related to the binding affinity [4].

Recent Advances: Conventional TSA analysis required a full titration of ligand concentrations, but recent methods (designated ZHC and UEC) enable accurate determination of binding affinity from a single ligand concentration. This significantly simplifies the protocol and enhances its suitability for high-throughput screening of drug-like molecules [4].

Performance Context: TSA is a cost-effective, rapid, and high-throughput technique, making it excellent for initial screening [4]. It is particularly advantageous for studying very high-affinity interactions that are challenging for ITC [4]. However, its reliance on a ligand-induced stabilization effect means it may not be suitable for all protein-ligand systems.

Table 1: Comparison of Key Experimental Techniques

| Method | Primary Measured Parameters | Key Advantages | Key Limitations | Typical Throughput |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) | ΔG, ΔH, K~a~ (directly); ΔS (calculated) | Label-free, provides full thermodynamic profile from one experiment, considered highly accurate | High protein consumption, moderate throughput | Low to Moderate |

| Thermal Shift Assay (TSA) | ΔT~m~ (used to derive K~d~) | Low cost, rapid, suitable for high-throughput screening, works for very high-affinity binders | Indirect measurement, requires protein unfolding, may not be universally applicable | High |

| Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) | Binding kinetics (k~on~, k~off~); K~d~ (from k~off~/k~on~) | Can measure binding kinetics, requires low analyte consumption | Requires immobilization of one binding partner, which can affect binding | Moderate to High |

Computational Prediction of Binding Energetics

Computational methods offer a complementary approach, enabling the prediction of binding affinity and its components before a compound is synthesized.

End-State Methods

These methods calculate free energies using simulations of only the bound and unbound (free) states.

- MM/PB(GB)SA: This method approximates the binding free energy by combining molecular mechanics (MM) energies in the gas phase with implicit solvation models (Poisson-Boltzmann/PB or Generalized Born/GB) and surface area (SA) corrections [5]. While faster than more rigorous methods, its accuracy is limited, with root-mean-square errors (RMSE) often reported around 2-4 kcal/mol [5].

- Linear Interaction Energy (LIE): This method uses simulations of the ligand in water and the protein-ligand complex to calculate the binding free energy based on scaled averages of the ligand's interaction energies [6]. A recent advance, ANI_LIE, incorporates machine-learning potentials (ANI-2x) to compute interaction energies at near-quantum mechanical accuracy (wb97x/6-31G* level), significantly improving correlation with experimental data (R=0.87-0.88) while maintaining a reduced computational cost [6].

Alchemical Perturbation Methods

These highly accurate methods calculate the free energy difference between two states by simulating a series of non-physical intermediate states along an alchemical pathway.

- Free Energy Perturbation (FEP) & Thermodynamic Integration (TI): These are the most accurate binding free energy prediction methods, with RMSE values often below 1 kcal/mol [5] [2]. They are, however, computationally intensive, requiring significant sampling and 12+ hours of GPU time per calculation, making them impractical for screening tens of thousands of molecules [5].

Table 2: Comparison of Key Computational Techniques

| Method | Computational Cost | Typical Accuracy (vs. Experiment) | Primary Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Docking | Low (minutes on CPU) | Low (RMSE: 2-4 kcal/mol, R ~0.3) [5] | Ultra-high-throughput virtual screening |

| MM/PB(GB)SA | Low to Moderate | Low to Moderate (RMSE: 2-4 kcal/mol) [5] | Post-docking scoring, moderate-throughput analysis |

| ANI_LIE | Moderate | Moderate to High (R: 0.87-0.88) [6] | End-state method with improved accuracy |

| FEP/TI | High (12+ hours on GPU) | High (RMSE: <1 kcal/mol, R: >0.65) [5] | Lead optimization for a small number of compounds |

A Practical Workflow: Integrating Experiment and Computation

The most effective drug design platforms integrate structural, thermodynamic, and biological information [1]. The following workflow, derived from the search results, illustrates how these methods can be combined.

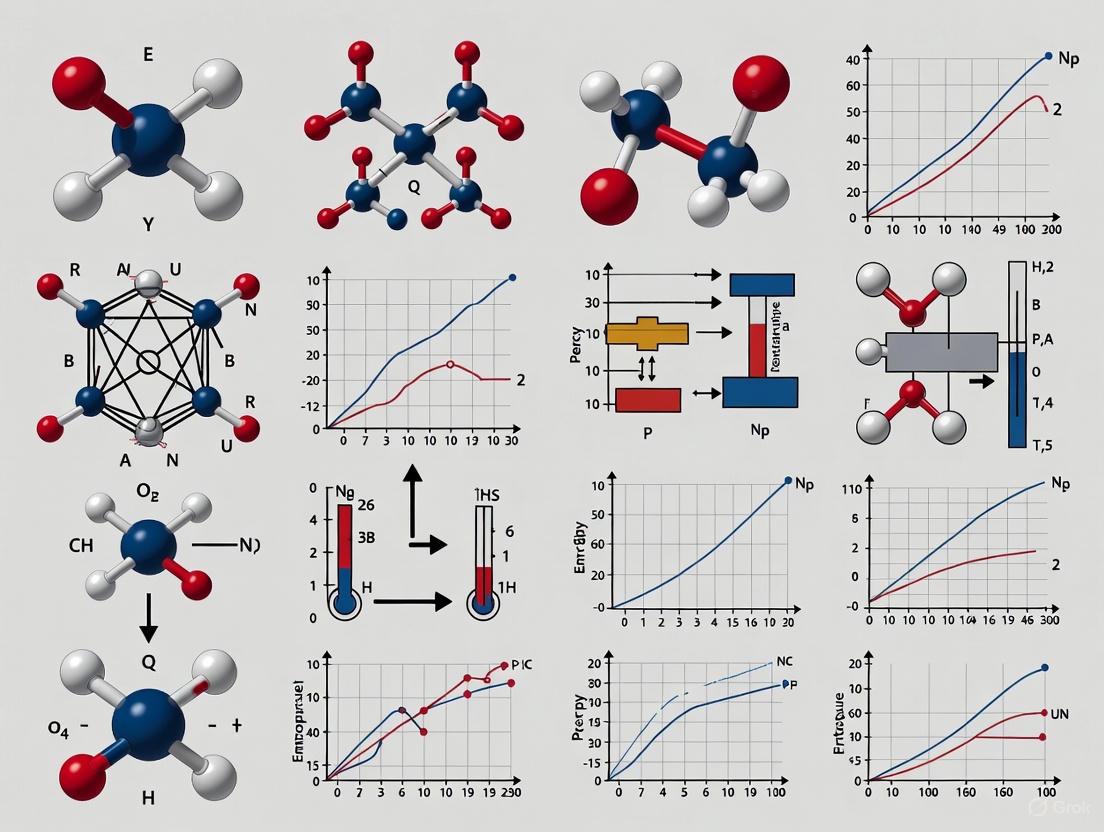

Diagram 1: An Integrated Drug Discovery Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Thermodynamic Studies

| Item / Reagent | Function / Application | Example in Use |

|---|---|---|

| SYPRO Orange Dye | Fluorescent dye that binds hydrophobic patches exposed upon protein denaturation, used to monitor unfolding. | Used as the fluorescent probe in Thermal Shift Assays (TSA) to determine the protein melting temperature (T~m~) [4]. |

| Purified Target Protein | The protein of interest, ideally >98% pure, required for both experimental and simulation studies. | Used in TSA (at 5-20 µM) [4] and ITC experiments; also the target for molecular dynamics simulations and docking [6] [5]. |

| Small Molecule Ligands | The drug-like compounds to be tested for binding to the target protein. | Prepared as stock solutions in appropriate buffers for TSA and ITC experiments [4]. Represented as small organic molecules in computational studies [6] [7]. |

| Molecular Dynamics (MD) Software | Software to simulate the physical movements of atoms and molecules over time. | LAMMPS, GROMACS, and OpenMM are used for MD simulations to generate conformational sampling for free energy calculations [6] [7] [8]. |

| Neural Network Potentials (NNPs) | Machine-learning models trained on quantum mechanical data to provide accurate potential energy surfaces. | The ANI-2x potential is used in the ANI_LIE method to compute interaction energies at DFT-level accuracy, improving binding free energy predictions [6]. |

A comprehensive understanding of the thermodynamic properties ΔG, ΔH, and ΔS is no longer a niche pursuit but a central element of efficient drug discovery. The trend observed in successful drug classes, such as HIV-1 protease inhibitors and statins, indicates that "best-in-class" drugs often achieve their superior profile through better enthalpic optimization [3]. While entropic optimization via hydrophobic interactions is more straightforward, it can lead to compounds with poor solubility [1] [3]. The future of rational drug design lies in the continued integration of experimental techniques like ITC and TSA, which provide rigorous thermodynamic data, with increasingly accurate computational methods like FEP and ANI_LIE. This powerful synergy allows researchers to not only predict binding affinity but also to understand and engineer the underlying energetic forces, thereby increasing the likelihood of developing successful therapeutic agents.

Understanding and predicting the thermodynamic properties of materials and biomolecules remains a central challenge in computational physics and chemistry. The core of this challenge lies in bridging the gap between the nanoscopic world of atoms and their interactions, and the macroscopic world of observable material properties. Statistical mechanics provides the fundamental theoretical framework for this bridge, defining the direct relationship between the potential energy of a system and its thermodynamic free energies. In modern computational science, Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations serve as the practical engine for traversing this bridge, generating the atomic trajectories from which macroscopic properties are derived. However, the accuracy of these derived properties is highly dependent on the computational methods employed. This guide provides a comparative analysis of current state-of-the-art methodologies, assessing their performance in delivering accurate, computationally efficient, and reliable predictions of thermodynamic properties for applications ranging from materials design to drug discovery.

Comparative Analysis of Methodologies and Performance

The landscape of computational methods for extracting thermodynamic data from MD simulations is diverse, encompassing techniques from traditional alchemical transformations to modern machine-learning-driven workflows. The table below provides a high-level comparison of the core methodologies discussed in this review.

Table 1: Comparison of Key Methodologies for MD-Derived Thermodynamic Properties

| Methodology | Core Principle | Key Outputs | Reported Advantages | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alchemical Free Energy (AFE) [9] [10] | Calculates free energy difference ((\Delta G)) between two end states via unphysical (alchemical) intermediates defined by a coupling parameter (\lambda). | Binding free energy, solvation free energy. | Well-established; readily implemented in major MD packages (GROMACS, DESMOND); ideal for relative binding affinities. | Drug discovery (ranking ligand binding) [11] [9]. |

| Bayesian Free-Energy Reconstruction [12] [13] | Reconstructs the Helmholtz free-energy surface from MD data using Gaussian Process Regression (GPR). | Heat capacity, thermal expansion, bulk moduli, melting properties. | Automated; provides uncertainty quantification (confidence intervals); works for solids and liquids [12]. | High-throughput materials screening; benchmarking interatomic potentials [12]. |

| Machine-Learning Potentials (MLPs) with TI [14] [15] | Uses ML potentials (e.g., Moment Tensor Potentials, Deep Potential) for efficient sampling, with Thermodynamic Integration (TI) to a high-accuracy ab initio reference. | High-accuracy free energies for complex properties up to the melting point. | Near-ab initio accuracy with significantly lower computational cost; captures strong anharmonicity [14]. | Predicting thermodynamic properties of alloys and elements where explicit anharmonicity is critical [14] [15]. |

A critical assessment of quantitative performance reveals the strengths of each approach. The Bayesian Free-Energy Reconstruction method has been demonstrated to compute key thermodynamic properties for nine elemental FCC and BCC metals using 20 different interatomic potentials, with all predictions accompanied by quantified confidence intervals [12] [13]. This uncertainty quantification is a significant advancement for assessing prediction reliability.

Meanwhile, methods leveraging ML Potentials show remarkable agreement with experimental data. For instance, calculations for bcc Nb, magnetic fcc Ni, fcc Al, and hcp Mg found "remarkable agreement with experimental data," with a reported five-fold speed-up compared to previous state-of-the-art ab initio methods [14]. In a specific study on PtNi alloys, a Deep Potential model demonstrated high accuracy, with "tensile strength deviations below 5% and phonon dispersion errors within 3%" [15].

Finally, the well-established Alchemical Free Energy methods are capable of calculating solvation free energies, such as for ethanol, with high precision, and are routinely used to predict protein-ligand binding free energies, a key task in rational drug design [11] [10].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure reproducibility and provide a clear understanding of the operational details, this section outlines the standard workflows for the featured methodologies.

Protocol for Alchemical Free Energy Calculations

This protocol is commonly used for calculating binding or solvation free energies in drug discovery [9] [10].

- Define End States and Thermodynamic Cycle: The process begins by defining the physical end states (e.g., ligand bound to protein and ligand in solution). An alchemical pathway is then designed using a thermodynamic cycle to connect these states via non-physical intermediates.

- System Preparation: The protein-ligand complex is prepared and solvated in a water box using a molecular mechanics force field (e.g., OPLS-AA). The ligand's coordinates and topology are defined separately.

- Define λ Pathway: The alchemical pathway is divided into a series of intermediate states (e.g., λ = 0, 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8, 0.9, 1.0). Electrostatic (Coulomb) and van der Waals (Lennard-Jones) transformations are often handled separately or with a "soft-core" potential to avoid singularities.

- Equilibrium Sampling: An equilibrium MD simulation is run at each λ value, storing energy differences (( \Delta U )) and/or the derivative of the potential with respect to λ (( \partial U/\partial \lambda )).

- Free Energy Estimation: The data from all λ windows are analyzed using estimators like the Bennett Acceptance Ratio (BAR) or Thermodynamic Integration (TI) to compute the total free energy difference along the alchemical path [10].

Protocol for Bayesian Free-Energy Reconstruction

This automated workflow is designed for high-throughput prediction of material properties [12] [13].

- MD Trajectory Sampling: Molecular dynamics simulations are run to sample the system's phase space across a range of volumes (V) and temperatures (T). The sampling can be irregular.

- Free-Energy Surface Reconstruction: The Helmholtz free-energy surface is reconstructed directly from the MD data using Gaussian Process Regression (GPR), a machine learning technique. This step captures anharmonic contributions.

- Uncertainty Propagation: The GPR framework natively propagates statistical uncertainties from the MD data through all subsequent calculations.

- Zero-Point Energy Correction: At low temperatures, corrections for quantum mechanical zero-point energy are incorporated based on harmonic or quasi-harmonic theory.

- Property Calculation: Thermodynamic properties (heat capacity, thermal expansion, bulk moduli) are calculated as derivatives of the reconstructed free-energy surface, with all predictions accompanied by quantified confidence intervals.

- Active Learning: The workflow can employ active learning to intelligently select new (V, T) points for simulation, optimizing sampling to maximize accuracy and efficiency.

The following diagram illustrates the logical flow and components of this Bayesian workflow.

Protocol for ML-Potential-Aided Thermodynamic Integration

This protocol achieves high accuracy for materials up to their melting point [14].

- Generate Training Data: Perform ab initio molecular dynamics (AIMD) or density functional theory (DFT) calculations on a diverse set of atomic configurations to create a reference dataset.

- Train Machine-Learning Potential: Train an ML potential (e.g., Moment Tensor Potential, Deep Potential) on the reference data. The DP-GEN framework can be used for active learning to ensure robust sampling of configuration space [15].

- Perform ML-MD Simulations: Run large-scale, efficient MD simulations using the trained ML potential over a dense grid of volume and temperature points.

- Direct Upsampling via TI: Use thermodynamic integration (TI) to calculate the free-energy difference between the system described by the ML potential and the high-accuracy ab initio reference. This "upsampling" step ensures final results are at the ab initio level of fidelity [14].

- Incorporate Excitations: Add contributions from electronic and magnetic excitations to the vibrational free energy, as shown in the equation: (F(V,T) = E_{0K}(V) + F^{el}(V,T) + F^{vib}(V,T) + F^{mag}(V,T)) [14].

- Parametrize and Derive Properties: Fit the calculated free energies to a smooth surface and compute thermodynamic properties via analytical derivatives.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

The following table details key software, algorithms, and computational tools that form the essential "reagents" for conducting research in this field.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for MD-Derived Thermodynamics

| Tool / Solution Name | Type | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| GROMACS [9] [10] | MD Software Suite | High-performance MD simulation engine, includes built-in methods for alchemical free energy calculations. | Running equilibrium sampling at multiple λ states for solvation and binding free energies. |

| alchemical-analysis.py [9] | Analysis Tool | Python script implementing best practices for analyzing alchemical free energy calculations (TI, FEP). | Standardized, reliable analysis of free energy simulations from GROMACS, AMBER, etc. |

| Gaussian Process Regression (GPR) [12] [13] | Machine Learning Algorithm | Reconstructs a continuous free-energy surface from sparse, noisy MD data and quantifies uncertainty. | Bayesian free-energy reconstruction; creating a smooth F(V,T) surface from MD trajectories. |

| DeepMD-Kit / DP-GEN [15] | ML Potential Platform | Tools for training and running Deep Potential models and generating datasets via active learning. | Developing accurate and efficient ML force fields for ab initio-level MD simulations of alloys. |

| Moment Tensor Potentials (MTPs) [14] | Machine-Learning Potential | A class of ML-interatomic potentials known for high data efficiency and accuracy. | Accelerating free-energy calculations for solids within the TU-TILD/direct upsampling framework. |

The comparative analysis presented in this guide underscores a paradigm shift in the computation of thermodynamic properties from molecular simulations. While traditional, manually intensive methods like alchemical free energy calculations remain vital for specific tasks such as ranking drug candidates, newer approaches are dramatically expanding the scope and reliability of predictions. The integration of machine learning, both in the analysis phase—as demonstrated by Bayesian free-energy reconstruction with built-in uncertainty quantification—and in the sampling phase—through the use of ML potentials—is providing a pathway to higher accuracy, greater automation, and unprecedented computational efficiency.

The emerging trend is towards unified, automated workflows that require less expert intervention, provide clear measures of confidence, and are applicable across diverse states of matter, from crystalline solids to liquids. As these tools mature and become more integrated into standard research pipelines, they promise to accelerate the discovery of new materials and therapeutics by providing a more robust and trustworthy bridge from atomic-scale simulations to macroscopic reality.

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations have become an indispensable tool in computational chemistry, structural biology, and drug discovery, providing atomistic insights into biomolecular processes that are challenging to capture experimentally [11] [16]. The accuracy of these simulations is fundamentally governed by the quality of the force field—a set of mathematical functions and parameters that describe the potential energy of a system as a function of the nuclear coordinates [17] [16]. Force fields inherently involve approximations that balance computational efficiency with physical accuracy, creating a critical foundation upon which all molecular calculations are built [16].

The development of biomolecular force fields has evolved significantly since the first all-atom MD simulation of a protein in 1977 [16]. Modern force fields can be broadly categorized into several classes: additive all-atom force fields, which use fixed partial atomic charges; polarizable force fields, which account for electronic polarization effects; coarse-grained models, which reduce computational cost by grouping atoms; and emerging machine-learning force fields, which leverage neural networks to represent potential energy surfaces [11] [16]. Each approach involves distinct approximations that impact their ability to accurately reproduce experimental observables and thermodynamic properties.

This review examines the inherent approximations in force field development through the lens of thermodynamic property prediction, comparing performance across different force field classes and providing guidance for researchers seeking to select appropriate models for their molecular simulations.

Methodological Framework: Benchmarking Force Field Accuracy

Experimental Benchmarking Strategies

Rigorous assessment of force field performance requires systematic comparison against experimental data. For biomolecular force fields, key benchmarking datasets include experimental measurements of density, heat capacity, free energies of solvation, and various transport properties [18] [17]. Structure-based experimental data from nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy and room-temperature X-ray crystallography provide crucial information about protein dynamics and conformational ensembles that can be used to validate force field predictions [18].

The benchmarking process typically involves running MD simulations using different force fields and comparing the results with experimentally determined properties. For example, in assessing force fields for polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS), researchers measure properties including density, heat capacities, isothermal compressibility, viscosity, and thermal conductivity across a range of temperatures and pressures, then compare these with simulation outcomes [17]. Similar approaches are applied to biomolecular systems, where force fields are evaluated on their ability to reproduce protein folding landscapes, ligand binding affinities, and conformational dynamics observed experimentally [16].

Quantifying Thermodynamic Accuracy

When benchmarking force fields for thermodynamic property prediction, researchers typically calculate the average relative deviation between simulated and experimental values. For phase behavior calculations, this involves comparing predicted vapor pressures and saturated liquid densities with experimental measurements [19]. In free energy calculations for drug discovery, the accuracy is assessed by computing the root-mean-square error between predicted and experimental binding affinities [11].

Statistical measures such as the Pearson correlation coefficient and linear regression analysis provide quantitative assessments of force field performance across multiple properties. These metrics help identify systematic biases in specific force fields and guide future development efforts toward more physically accurate models [17].

Comparative Analysis of Force Field Performance

Small Molecule Force Fields: The Case of H₂S and CO₂

The phase behavior of hydrogen sulfide (H₂S) and carbon dioxide (CO₂) mixtures presents a challenging test case for force field accuracy, with implications for corrosion prediction and natural gas processing [19]. Different H₂S models vary in their complexity, ranging from simple 3-site models with a single Lennard-Jones center to more sophisticated 4-site and 5-center models that include polarizable sites [19].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of H₂S Force Field Models for Vapor-Liquid Equilibrium Prediction

| Model Type | Description | Computational Cost | Accuracy for H₂S+CO₂ VLE |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3-1 Model | 3 partial charge sites, 1 LJ site on S atom | Low | Moderate |

| 3-3 Model | 3 partial charge sites, 3 LJ sites | Medium | High |

| 4-1 Model | 4 charge sites (negative charge shifted from S), 1 LJ site | Medium | Varies by parameterization |

| 4-3 Model | 4 charge sites, 3 LJ sites | High | High |

| 5-site Polarizable | Includes polarizable sites | Very High | Good but computationally expensive |

Monte Carlo simulations comparing these models have revealed that the more sophisticated 4-3 and 3-3 models generally provide the best agreement with experimental vapor-liquid equilibrium (VLE) data for H₂S+CO₂ mixtures across temperatures ranging from 273.15K to 333.15K [19]. The 4-1 model parameterized by Kristóf and Liszi was found to overestimate the interaction forces between H₂S and CO₂, leading to less accurate VLE predictions [19]. Interestingly, non-polarizable models based on effective potentials have demonstrated good performance in describing the phase behavior of H₂S-containing mixtures, suggesting that proper parameterization can sometimes compensate for the lack of explicit polarization in certain applications [19].

For CO₂, the TraPPE model parameterized by Potoff and Siepmann has shown excellent performance in predicting thermodynamic properties, while the single-site model proposed by Iwai et al. provides reasonable accuracy for volumetric properties with significantly reduced computational cost [19]. The selection of appropriate combination rules for unlike interactions between H₂S and CO₂ molecules significantly impacts the accuracy of mixture predictions, highlighting the importance of cross-interaction parameters in force field development.

Biomolecular Force Fields: Additive and Polarizable Models

Additive all-atom force fields such as AMBER, CHARMM, and OPLS-AA remain the most widely used models for biomolecular simulations due to their computational efficiency and extensive parameter sets for proteins, nucleic acids, and lipids [16]. These force fields assign fixed partial charges to each atom and use pairwise additive approximations for electrostatic interactions, which represents a significant simplification of the true electronic structure [16].

Table 2: Comparison of Biomolecular Force Field Classes

| Force Field Class | Electrostatic Treatment | Computational Cost | Key Applications | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Additive All-Atom | Fixed partial charges, pairwise additive | Low to Medium | Routine protein simulations, ligand binding | No polarization effects, limited transferability |

| Polarizable | Inducible dipoles, fluctuating charges | High | Membrane systems, ion channels, spectroscopy | Parameterization complexity, high computational cost |

| Coarse-Grained | Effective potentials for bead groups | Low | Large systems, long timescales | Loss of atomic detail, limited chemical specificity |

| Machine Learning | Neural network potentials | Varies (training high, inference medium) | Quantum accuracy for specific systems | Limited transferability, data requirements |

Polarizable force fields such as the classical Drude model, AMOEBA, and others attempt to address the limitations of fixed-charge models by explicitly accounting for electronic polarization effects [16]. These models demonstrate improved accuracy in simulating membrane systems, ion channels, and spectroscopic properties, but at significantly higher computational cost—typically 3-4 times slower than additive force fields [16]. For certain properties like amino acid conformational preferences and helix formation, polarizable models have shown remarkable agreement with quantum mechanical calculations, suggesting they better capture the underlying physics of molecular interactions [16].

Recent benchmarking studies highlight that no single force field consistently outperforms others across all properties and systems. The selection of an appropriate force field must therefore be guided by the specific application, property of interest, and available computational resources.

Polymer Force Fields: The PDMS Benchmarking Study

A comprehensive benchmark of force fields for polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) provides a revealing case study in force field performance for polymeric materials [17]. This systematic evaluation compared five force fields—OPLS-AA, COMPASS, Dreiding, Huang's model, and a united-atom model—against experimental measurements of thermodynamic and transport properties [17].

Table 3: PDMS Force Field Performance Across Thermodynamic Properties

| Force Field | Type | Density Prediction | Heat Capacity | Viscosity | Thermal Conductivity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OPLS-AA | All-Atom (Class I) | Good with modified charges | Moderate | Underestimates | Significant deviation |

| COMPASS | All-Atom (Class II) | Good | Good | Moderate accuracy | Moderate accuracy |

| Dreiding | All-Atom (Class I) | Poor (overestimates) | Poor | Poor | Significant deviation |

| Huang's Model | All-Atom (Class II) | Excellent | Good | Good | Best overall performance |

| United-Atom | United-Atom | Good | Moderate | Good | Moderate accuracy |

The study revealed significant variations in force field performance across different property types. While all-atom Class II force fields (COMPASS and Huang's model) generally provided the best overall performance, no single force field excelled across all thermodynamic and transport properties [17]. For example, the specifically parameterized Huang's model demonstrated superior performance for density and thermal conductivity predictions, while the united-atom model offered a favorable balance between accuracy and computational efficiency for certain applications [17].

Notably, force fields parameterized specifically for PDMS (Huang's model and the united-atom model) generally outperformed universal force fields, highlighting the trade-off between transferability and specificity in force field development [17]. This benchmarking study also revealed that force fields parameterized using thermodynamic data did not always accurately predict dynamic and transport properties, emphasizing the need for comprehensive validation across multiple property types [17].

Experimental Protocols for Force Field Validation

Molecular Simulation Workflow

The standard protocol for force field validation begins with system generation, where polymer chains or biomolecules are randomly placed in a simulation box using tools like Packmol [17]. The system then undergoes energy minimization to remove unfavorable contacts, followed by equilibration in the NPT ensemble (constant number of particles, pressure, and temperature) until properties such as density converge [17]. Production simulations are subsequently performed to collect data for property calculations, with careful monitoring of energy fluctuations to ensure proper equilibration [17].

For vapor-liquid equilibrium calculations, Gibbs Ensemble Monte Carlo (GEMC) simulations are often employed, allowing direct determination of phase equilibria without interface simulation [19]. These simulations create two simulation boxes representing coexisting vapor and liquid phases, with molecular transfer between phases to establish equilibrium [19].

Force Field Validation Workflow: This diagram illustrates the standard protocol for validating force field accuracy through molecular simulation and experimental comparison.

Enhanced Sampling Techniques

To overcome the timescale limitations of conventional MD simulations, enhanced sampling methods are frequently employed in force field validation. These include:

- Replica Exchange MD (REMD): Multiple copies of the system run at different temperatures, with occasional exchanges that enhance conformational sampling [11].

- Metadynamics: History-dependent bias potentials are added to encourage exploration of configuration space and facilitate crossing of energy barriers [11].

- Accelerated MD (aMD) : The potential energy landscape is modified to reduce energy barriers, increasing the rate of transitions between states [11].

These techniques enable more thorough sampling of conformational space, providing better assessment of force field performance across diverse molecular configurations and improving the statistical reliability of calculated thermodynamic properties [11].

Table 4: Essential Computational Tools for Force Field Development and Validation

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| LAMMPS | MD Simulation Package | Large-scale atomic/molecular massively parallel simulator | General purpose MD simulations [17] |

| Packmol | System Builder | Initial configuration generation for molecular systems | Creating simulation boxes with randomly placed molecules [17] |

| Moltemplate | Force Field Processor | Generate topology and parameters for universal force fields | Preparing simulation input files [17] |

| SAFT-γ Mie | Coarse-Grained Force Field | Top-down approach using molecular-based equation of state | Calculating properties not directly obtained from equations of state [19] |

| ANI-2x | Machine Learning FF | Neural network potential trained on DFT calculations | Quantum accuracy with reduced computational cost [11] |

| AlphaFold2 | Structure Prediction | ML-based protein structure prediction | Generating initial structures for simulation [11] |

Emerging Trends and Future Directions

Machine Learning Force Fields

Machine learning approaches are transforming force field development by using neural networks to represent potential energy surfaces, potentially achieving quantum mechanical accuracy at classical force field computational cost [11] [16]. Methods such as ANI-2x demonstrate that neural network potentials trained on millions of density functional theory calculations can capture complex quantum effects while remaining computationally feasible for molecular simulations [11].

The key advantage of machine learning force fields lies in their ability to learn arbitrary potential energy surfaces without imposing analytical constraints, potentially overcoming the accuracy limitations of traditional functional forms [11]. However, current ML force fields face challenges in transferability beyond their training sets and require extensive quantum mechanical data for parameterization, limiting their general applicability [16].

Automation in Force Field Parameterization

Traditional force field development relies heavily on manual atom typing—a labor-intensive process where experts assign specific types to each atom based on chemical identity and local environment [16]. Emerging approaches seek to automate or eliminate atom typing through algorithms that directly assign parameters based on quantum mechanical calculations or machine learning [16].

The Open Force Field Initiative and related efforts are developing open-source, automated parameterization tools that leverage quantum chemical data and experimental measurements to create more accurate and transferable force fields [16]. These initiatives aim to address the chemical diversity challenges in drug discovery, where existing force fields struggle to represent the exponentially expanding chemical space of small molecule therapeutics [16].

Addressing Chemical Complexity

Future force field development must better handle post-translational modifications (PTMs), covalent inhibitors, and the complex molecular environments found in cellular systems [16]. With 76 types of PTMs identified to date, representing an expanding landscape of chemical modifications, there is growing need for force fields that can accurately model these chemical variations without requiring exhaustive reparameterization [16].

Similarly, the emergence of molecular glues and proteolysis targeting chimeras (PROTACs) in drug discovery demands force fields capable of accurately describing complex three-body systems involving multiple proteins and small molecules [16]. Meeting these challenges will require more physically realistic representations of molecular interactions, potentially through the wider adoption of polarizable force fields or novel machine learning approaches [16].

Force fields represent foundational approximations that dictate the accuracy and applicability of molecular simulations across scientific disciplines. The inherent trade-offs between computational efficiency, physical realism, and transferability necessitate careful selection of force fields based on the specific research question and target properties. Benchmarking studies consistently demonstrate that force field performance varies significantly across different molecular systems and thermodynamic properties, with no single model universally outperforming others.

The continuing evolution of force fields—driven by advances in polarizable models, coarse-grained approaches, and machine learning—promises to extend the capabilities of molecular simulations to increasingly complex biological questions and materials design challenges. As these tools become more accurate and accessible, they will further cement the role of molecular modeling as an essential component of scientific discovery and technological innovation.

In computational structural biology, the absolute entropy (S) and the corresponding Helmholtz free energy (F) are fundamental thermodynamic quantities with profound importance for understanding protein folding, ligand binding, and molecular stability [20]. Entropy represents a measure of disorder and randomness in a system, and in the context of Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations, it quantifies the conformational freedom and disorder within protein molecules [21]. Despite its critical role, calculating entropy by computer simulation is notoriously difficult, as the value of the Boltzmann probability (ln P_t^B) is not directly accessible from standard MD simulations but is instead a function of the entire ensemble through the partition function Z [20]. This fundamental challenge has driven the development of various computational methods to estimate entropic contributions, particularly for binding free energy calculations in drug development.

Theoretical Foundations: Statistical Mechanics of Entropy

In statistical mechanics, the absolute entropy, S, is defined by the Gibbs entropy formula S = -kB Σi Pi^B ln Pi^B, where kB is Boltzmann's constant and Pi^B is the Boltzmann probability of configuration i [20]. The Helmholtz free energy, F, combines energy and entropy through the relationship F = 〈E〉 - TS, where 〈E〉 is the ensemble average of the potential energy [20]. An essential property of this representation is that its variance vanishes (σ^2(F) = 0), meaning the exact free energy could theoretically be obtained from any single structure i if P_i^B were known [20]. However, unlike energy, which can be directly averaged from sampled configurations, entropy estimation requires specialized approaches due to its dependence on the complete configurational ensemble.

Comparative Analysis of Entropy Calculation Methods

End-State Methods: MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA

End-state methods provide a practical framework for binding free energy calculations by eliminating the need to simulate intermediate states. The Molecular Mechanics/Poisson-Boltzmann Surface Area (MM/PBSA) and Molecular Mechanics/Generalized Born Surface Area (MM/GBSA) approaches estimate binding free energies using the formula:

ΔGbinding (solvated) = ΔGsolvated, complex - (ΔGsolvated, receptor + ΔGsolvated, ligand) [21]

The total free energy for each term is calculated as ΔGtotal (solvated) = Egas, phase + (ΔGsolvation - T × Ssolute), where Egas, phase represents gas-phase energies from molecular mechanics force fields, ΔGsolvation accounts for solvation effects using implicit solvent models, and -T × S_solute represents the entropic contribution [21]. MM/PBSA uses the Poisson-Boltzmann equation for accurate but computationally expensive solvation calculations, while MM/GBSA employs the Generalized Born model as a faster approximation with reduced accuracy [21].

Normal Mode Analysis (NMA)

Normal Mode Analysis involves calculating vibrational frequencies at local minima on the potential energy surface to approximate vibrational entropy [21]. The methodology requires several precise steps: (1) energy minimization of the system to reach equilibrium geometry using algorithms like steepest descent, conjugate gradient, or Newton-Raphson methods; (2) construction of the Hessian matrix containing second derivatives of potential energy via analytical derivatives or finite differences; (3) mass-weighting to form a dynamical matrix; and (4) diagonalization to obtain eigenvalues and eigenvectors representing vibrational frequencies and atomic displacement patterns [21]. Despite its theoretical rigor, NMA suffers from significant limitations, including computational demands that scale approximately as (3N)^3 with the number of atoms N, and the critical assumption of harmonicity which fails for systems with substantial anharmonicity at higher temperatures or in flexible molecules [21].

Quasi-Harmonic Analysis (QHA)

Quasi-Harmonic Analysis offers a less computationally intensive alternative to NMA by approximating the eigenvalues of the mass-weighted covariance matrix derived from MD ensembles as frequencies of global, orthogonal motions [21]. This method calculates vibrational entropies using standard formulas but requires many ensemble frames to accurately estimate the total entropy, thereby increasing the computational load of the initial simulation [21]. Unlike NMA, which assumes harmonic behavior around a single energy minimum, QHA can capture some anharmonic effects by analyzing fluctuations across the simulation trajectory.

Free Energy Perturbation (FEP) and Thermodynamic Integration (TI)

Advanced computational methods like Free Energy Perturbation (FEP), replica exchange FEP, and thermodynamic integration provide more rigorous approaches to estimate thermodynamic properties, including entropy [21]. These methods are computationally demanding for large systems and often require intermediate states to achieve proper convergence, but they offer a more complete treatment of the free energy landscape compared to end-state methods [21].

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Entropy Calculation Methods

| Method | Computational Cost | Key Assumptions | Primary Applications | Accuracy Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal Mode Analysis (NMA) | Very High (scales as ~(3N)³) | Harmonic approximation, single minimum | Vibrational entropy of relatively rigid systems | Fails for flexible systems with significant anharmonicity [21] |

| Quasi-Harmonic Analysis (QHA) | Moderate-High (requires extensive sampling) | Gaussian distribution of fluctuations | Configurational entropy from MD ensembles | More forgiving than NMA but still limited by harmonic assumption [21] |

| MM/PBSA with NMA/QHA | High (combined cost of MD and entropy calculation) | Additivity of energy terms, implicit solvent | Binding free energies, protein-ligand interactions | Sensitive to force field quality, sampling adequacy [21] |

| Free Energy Perturbation (FEP) | Very High (requires many intermediate states) | Overlap between successive states | Absolute binding free energies, alchemical transformations | Considered gold standard but computationally prohibitive for large systems [21] |

Methodological Protocols and Implementation

Standard NMA Implementation Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the sequential workflow for implementing Normal Mode Analysis in molecular dynamics simulations:

End-State Method Implementation Protocol

For MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA calculations, the following protocol should be implemented:

- System Preparation: Build the receptor-ligand complex, ensuring proper protonation states and missing residue completion.

- Molecular Dynamics Simulation: Perform explicit solvent MD simulation to generate an ensemble of conformational snapshots. For proteins, this typically requires 50-100 ns of simulation time, with coordinates saved every 100 ps.

- Trajectory Processing: Remove solvent molecules and counterions from the trajectory to isolate the solute coordinates for subsequent calculations.

- Energy Calculations: For each snapshot, calculate the gas-phase energy (E_gas, phase) using molecular mechanics force fields, which include bonded terms (bond stretching, angle bending, dihedral angles) and non-bonded terms (van der Waals and electrostatic interactions) [21].

- Solvation Free Energy: Compute ΔG_solvation using either Poisson-Boltzmann (MM/PBSA) or Generalized Born (MM/GBSA) models, decomposing into electrostatic and nonpolar contributions [21].

- Entropic Calculation: Estimate solute entropy (-T × S_solute) using either NMA or QHA on the snapshots, considering translational, rotational, and vibrational components [21].

- Ensemble Averaging: Average all energy components over the entire ensemble of snapshots and compute the final binding free energy using equation 2.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Entropy Calculations

| Tool/Software | Type | Primary Function | Entropy-Specific Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| AMBER | MD Software Suite | Biomolecular simulation and analysis | Integrated NMA implementation with support for entropy calculations in MM/PBSA [21] |

| GROMACS | MD Software Package | High-performance molecular dynamics | Quasi-harmonic entropy calculations, covariance matrix analysis |

| NAMD/VMD | MD Software with Visualization | Simulation and trajectory analysis | Normal mode analysis plugins, vibrational mode visualization [21] |

| MM/PBSA & MM/GBSA | Analytical Methods | Binding free energy estimation | Framework for incorporating entropic contributions from NMA or QHA [21] |

| Hessian Matrix | Mathematical Construct | Second derivatives of potential energy | Fundamental component for NMA frequency calculations [21] |

Challenges and Limitations in Entropy Calculation

Theoretical and Practical Limitations

Entropy calculation methods face several fundamental challenges. The harmonic approximation inherent in both NMA and QHA assumes small amplitude vibrations around a single energy minimum, but this breaks down in systems with significant anharmonicity, such as flexible proteins at physiological temperatures [21]. NMA specifically assumes atoms vibrate around equilibrium positions with small amplitudes, but at higher temperatures or in flexible molecules, anharmonic effects become significant and the harmonic approximation fails [21]. Additionally, defining microstates for entropy calculations presents conceptual difficulties, as their boundaries in conformational space are often unknown and depend on simulation length, with longer simulations potentially capturing transitions between what might be considered separate microstates [20].

Computational Constraints

The computational expense of entropy calculations presents substantial barriers to application. NMA requires energy minimization of each frame, construction of the Hessian matrix, and diagonalization of a 3N×3N matrix, with costs scaling approximately as (3N)^3 where N is the number of atoms [21]. While QHA avoids the minimization and Hessian calculation steps, it still requires extensive sampling and covariance matrix analysis that becomes demanding for large systems. Solvent treatment introduces additional complexity, as including explicit water molecules dramatically increases system size, while implicit solvent models may oversimplify solvent entropy contributions critical to processes like hydrophobic interactions [21].

Table 3: Accuracy Considerations for Different Molecular Systems

| System Type | Recommended Method | Key Considerations | Expected Reliability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rigid Proteins with Small Ligands | NMA with MM/PBSA | Minimization must reach true minimum; harmonic assumption more valid | High for relative comparisons [21] |

| Flexible Proteins or Loops | QHA with MM/GBSA | Requires extensive sampling of conformational space; anharmonic effects significant | Moderate, depends on sampling quality [21] |

| Protein-Protein Interactions | End-state methods with NMA | Entropy contribution large but calculation challenging; convergence issues | Low to moderate, interpret with caution [21] |

| Membrane Proteins | Specialized protocols | Environment complexity; additional entropy contributions from lipids | Variable, method-dependent |

Entropy calculation remains a challenging but essential component of extracting thermodynamic properties from molecular dynamics simulations. While methods like Normal Mode Analysis and Quasi-Harmonic Analysis provide practical approaches for estimating entropic contributions, they suffer from significant limitations including computational expense, harmonic approximations, and difficulties in treating solvent effects and flexible systems. For researchers in drug development, careful selection of entropy calculation methods based on system characteristics and research goals is crucial, with NMA suitable for more rigid systems and QHA preferable for flexible molecules when computational resources allow. Future methodological developments addressing anharmonicity, improving solvent treatments, and reducing computational costs will enhance our ability to accurately quantify entropy in molecular systems, ultimately improving the prediction of binding affinities and molecular stability in drug design applications.

Advanced Methods for Calculating Thermodynamic Properties from MD Simulations

Computational methods for calculating free energy changes are indispensable tools in molecular modeling, playing a critical role in predicting the strength of molecular interactions in processes such as protein-ligand binding, protein folding, and solvation. The accuracy of these predictions is paramount for applications in structure-based drug design and protein engineering. Among the most established techniques are Free Energy Perturbation (FEP), Thermodynamic Integration (TI), and Molecular Mechanics/Poisson-Boltzmann Surface Area (MM/PBSA). This guide provides an objective comparison of these three methods, evaluating their performance, accuracy, and computational efficiency based on published experimental data and benchmarks. The analysis is framed within the broader context of assessing the accuracy of molecular dynamics (MD)-derived thermodynamic properties, offering researchers a clear framework for selecting the appropriate method for their specific scientific inquiries.

Molecular Mechanics/Poisson-Boltzmann Surface Area (MM/PBSA) is an end-point method that calculates binding free energies by combining molecular mechanics calculations with continuum solvation models. It estimates the binding free energy (ΔGbind) between a receptor (R) and a ligand (L) to form a complex (RL) using the formula: ΔGbind = ΔEMM + ΔGsol - TΔS. Here, ΔEMM represents the change in gas-phase molecular mechanics energy (including internal, electrostatic, and van der Waals energies), ΔGsol is the change in solvation free energy (calculated using a Poisson-Boltzmann model for the polar part and a surface area approach for the non-polar part), and -TΔS is the change in conformational entropy upon binding [22] [23] [24]. A key advantage is its computational efficiency, as it typically requires sampling only from a single MD simulation of the bound complex.

Free Energy Perturbation (FEP) and Thermodynamic Integration (TI) are alchemical methods considered more rigorous but computationally intensive. They compute free energy differences by gradually transforming one system into another through a series of non-physical, intermediate states. This transformation is controlled by a coupling parameter, λ. FEP uses the Zwanzig equation to calculate the free energy difference between adjacent λ states based on the exponential average of the potential energy difference [24]. TI, conversely, integrates the average derivative of the Hamiltonian with respect to λ over the transformation pathway [23]. These methods are often applied within a thermodynamic cycle to compute relative binding free energies (RBFE), which is the difference in binding affinity between two similar ligands binding to the same receptor [25] [24]. This avoids the more challenging calculation of the absolute binding free energy.

The diagram below illustrates the fundamental difference between the end-point and alchemical approaches:

Performance Comparison and Experimental Data

The choice between MM/PBSA, FEP, and TI involves a trade-off between computational cost and predictive accuracy. The following table summarizes their key characteristics and performance metrics based on published benchmarks.

Table 1: Comparative performance of free energy calculation methods

| Feature | MM/PBSA | FEP | TI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Computational Cost | Low to Moderate [23] | High [23] [26] | High [23] |

| Typical Accuracy | Moderate; good for ranking but can have large errors in absolute values [22] | High (~1 kcal/mol for RBFE) [25] | High (theoretically rigorous) [23] |

| Primary Application | Binding affinity ranking, virtual screening [22] [23] | Relative binding free energies for lead optimization [25] [23] | Relative binding free energies [23] |

| Sampling Requirement | Single MD trajectory of the complex [22] | Multiple simulations along λ for both bound and unbound states [25] | Multiple simulations along λ for both bound and unbound states [23] |

| Handling of Entropy | Approximate (e.g., normal mode analysis); often omitted due to cost and noise [22] [24] | Implicitly included via the transformation pathway | Implicitly included via the transformation pathway |

| Key Limitation | Sensitivity to parameters (e.g., dielectric constant); implicit solvation model [22] [26] | High computational cost; convergence issues [25] | High computational cost; requires integration of ∂U/∂λ [23] |

Quantitative benchmarks provide concrete evidence of these performance characteristics. A systematic study of 59 ligands across six proteins found that MM/PBSA was sensitive to simulation protocols and solute dielectric constants, but could successfully rank inhibitor affinities, making it a powerful tool for drug design where correct ranking is emphasized [22]. In contrast, a study on thrombin inhibitors demonstrated that FEP calculations could achieve an accuracy of about 1 kcal/mol for relative binding free energies, which is sufficient to discern affinities with less than a tenfold difference [25]. It was also noted that this level of accuracy might be limited by the quality of the force field rather than sampling efficiency when enhanced sampling techniques are employed [25].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure reproducibility and reliable results, adherence to standardized protocols for simulation setup and analysis is critical. The following workflows detail the general procedures for MM/PBSA and alchemical free energy calculations (FEP/TI).

MM/PBSA Protocol

The typical workflow for an MM/PBSA calculation involves system preparation, molecular dynamics simulation, and energy analysis.

Key steps include:

- System Preparation: The initial protein-ligand complex structure is obtained from a source like the Protein Data Bank. Force field parameters (e.g., AMBER, CHARMM) are assigned to the protein and ligand. The system is solvated in a water box (e.g., TIP3P) and neutralized by adding counterions [22].

- Molecular Dynamics Simulation: The system undergoes energy minimization to remove steric clashes. This is followed by a gradual heating to the target temperature (e.g., 300 K) and equilibration at constant pressure (1 atm). A production MD simulation is then run to sample conformational space. For MM/PBSA, a single trajectory of the complex is often used [22].

- Energy Analysis: A large number of uncorrelated snapshots are extracted from the MD trajectory. For each snapshot, the molecular mechanics energy (ΔEMM) is computed in vacuum. The solvation free energy (ΔGsol) is decomposed into polar (calculated using Poisson-Boltzmann or Generalized Born models) and non-polar (estimated from the solvent-accessible surface area) components. Conformational entropy (-TΔS) can be estimated via normal mode or quasi-harmonic analysis, but is frequently omitted due to high computational cost and large uncertainties [22] [24].

FEP/TI Protocol

Alchemical calculations follow a distinct protocol centered on defining and sampling a λ pathway.

Key steps include:

- Define the Thermodynamic Cycle: The calculation is set up to compute the relative binding free energy between two ligands (A and B) by creating a cycle that connects the physical binding processes through alchemical transformations in the bound and unbound (solvated) states [25] [9].

- Create a Hybrid Topology: The system is prepared to represent both the initial (Ligand A) and final (Ligand B) states simultaneously. Modern protocols like QresFEP-2 use a hybrid-topology approach, which combines a single-topology representation for the common backbone atoms with a dual-topology for the changing side-chain atoms to maximize computational efficiency and phase-space overlap [27].

- Sample the λ Pathway: The transformation from A to B is broken down into many discrete windows (e.g., 12-24 λ values). Separate MD simulations are performed for each λ window in both the protein-bound environment and in solution. To improve sampling across high-energy barriers, enhanced sampling techniques like Hamiltonian Replica Exchange (H-REMD) can be employed, where configurations are swapped between adjacent λ windows [25].

- Free Energy Analysis and Validation: The free energy change for the transformation is computed from the simulation data. For FEP, estimators like the Bennett Acceptance Ratio (BAR) or Multistate BAR (MBAR) are used [9]. For TI, the free energy is obtained by numerically integrating the ensemble-average of ∂U/∂λ over λ. Crucially, the analysis must include checks for convergence, such as ensuring sufficient phase-space overlap between adjacent λ states and estimating statistical errors [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful free energy calculations rely on a suite of specialized software tools and parameters. The following table catalogues key resources mentioned in the literature.

Table 2: Key research reagents and computational tools for free energy calculations

| Reagent/Solution | Function/Description | Example Use in Context |

|---|---|---|

| AMBER | A suite of biomolecular simulation programs, includes modules for MD, FEP, TI, and MM/PBSA. | Used in benchmarks for MM/PBSA calculations on 59 protein-ligand complexes [22]. |

| GROMACS | A molecular dynamics package with high performance and tools for free energy calculations (FEP, TI). | Often used with tools like g_mmpbsa for MM/PBSA analysis [24]. |

| FEP+ | A commercial, automated FEP workflow within the Schrödinger software suite. | Validated on a broad dataset encompassing 10 protein targets [27]. |

| QresFEP-2 | An open-source, hybrid-topology FEP protocol integrated with the MD software Q. | Benchmarked on a comprehensive protein stability dataset of nearly 600 mutations [27]. |

| Soft-Core Potentials | Modified potential energy functions that prevent singularities when atoms are created/annihilated at λ endpoints. | Used in FEP/MD for rigorous calculations to avoid convergence problems as λ approaches 0 or 1 [25] [9]. |

| alchemical-analysis.py | A Python tool for analyzing alchemical free energy calculations, implementing best practices. | Helps automate analysis and assess the quality of FEP/TI data [9]. |

| Generalized Born (GB) Models | Implicit solvent models used to approximate the polar solvation energy in MM/GBSA. | The Onufriev and Case GB model was identified as the most successful in ranking binding affinities in a benchmark study [22]. |

Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulation is a cornerstone of computational materials science and drug discovery, providing unparalleled atomic-level insight into dynamic processes. However, a fundamental limitation plagues conventional MD: its restriction to microsecond timescales, while many functional biological processes and materials transformations occur on timescales ranging from milliseconds to hours or even years [28]. This several-orders-of-magnitude gap makes direct simulation of many critical phenomena—such as protein conformational changes, rare-event transformations, and slow transport properties—infeasible with standard methods.

Enhanced sampling techniques have emerged as powerful computational strategies designed to overcome this timescale barrier. By intelligently accelerating the exploration of configurational space, these methods enable researchers to study rare events that would otherwise be inaccessible to simulation. This guide provides a systematic comparison of contemporary enhanced sampling approaches, evaluating their theoretical foundations, methodological implementations, and performance across diverse applications in biomolecular and materials systems.

Methodological Frameworks and Theoretical Foundations

Collective Variable-Based Enhanced Sampling

Collective variable (CV)-based methods represent one of the most established enhanced sampling paradigms. These techniques operate by applying bias potentials along preselected slow degrees of freedom to drive transitions between metastable states.

Key Methodological Principles: CV-based approaches, including umbrella sampling, adaptive biasing force, and metadynamics, accelerate conformational changes by reducing the effective energy barriers along user-defined reaction coordinates [28]. The efficacy of these methods hinges entirely on selecting appropriate CVs that capture the essential physics of the transition process. Without well-chosen CVs, these methods provide little more acceleration than standard MD simulations [28].

Recent Theoretical Advances: A significant breakthrough in this domain is the identification of true reaction coordinates (tRCs), which are defined as the few essential protein coordinates that fully determine the committor (probability of reaching the product state) of any system conformation [28]. The committor (pB) precisely tracks progression of conformational changes, with pB = 0 for reactants, pB = 1 for products, and pB = 0.5 for the transition state. True reaction coordinates are now recognized as the optimal CVs for accelerating conformational changes, as they generate accelerated trajectories that follow natural transition pathways [28].

Table 1: Key Enhanced Sampling Method Classes and Characteristics

| Method Class | Theoretical Basis | Key Accelerator | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| CV-Based Methods | Bias potential along reaction coordinates | Collective variable biasing | Protein conformational changes, ligand binding |

| Free Energy Reconstruction | Gaussian Process Regression from MD data | Active learning in parameter space | Thermodynamic properties, phase stability |

| Coarse-Grained ML | Machine-learned potential of mean force | System simplification & force matching | Large systems, long-timescale dynamics |

| Path Sampling | Transition path ensemble generation | Focused sampling of reactive trajectories | Rare event mechanisms, transition states |

Bayesian Free-Energy Reconstruction

An alternative approach circumvents the need for predefined CVs through Bayesian reconstruction of free-energy surfaces from molecular dynamics data. This method employs Gaussian Process Regression to reconstruct the Helmholtz free-energy surface F(V,T) from irregularly sampled MD trajectories [29].

Workflow Integration: The methodology extracts ensemble-averaged potential energies and pressures from NVT-MD simulations, which provide direct access to derivatives of the Helmholtz free energy [29]. The Gaussian Process Regression framework then propagates statistical uncertainties from MD sampling into predicted thermodynamic properties, reducing systematic errors and mitigating finite-size effects. This approach incorporates quantum effects through zero-point energy corrections derived from harmonic/quasi-harmonic theory, bridging the quantum-classical divide [29].

Automation Through Active Learning: A distinctive advantage of this framework is its implementation of an active learning strategy that adaptively selects new (V,T) points for simulation, rendering the workflow fully automated and highly efficient [29]. This automation enables direct application to both crystalline and liquid phases, extending beyond the limitations of phonon-based methods.

Machine Learning-Augmented Sampling

Machine learning potentials (MLPs) have revolutionized enhanced sampling by combining quantum-mechanical accuracy with empirical-potential computational efficiency. The neuroevolution potential framework exemplifies this approach, generating highly efficient MLPs trained on highly accurate reference data [30].

Accuracy-Speed Synergy: MLPs like NEP-MB-pol achieve force prediction errors as low as 69.77 meV/Å compared to coupled-cluster reference calculations, while maintaining computational speeds sufficient for large-scale molecular dynamics simulations [30]. This combination enables accurate modeling of complex systems like water across broad temperature ranges, capturing structural, thermodynamic, and transport properties simultaneously.

Coarse-Graining with Machine Learning: Further acceleration is possible through machine-learned coarse-grained potentials, which simplify systems by grouping atoms into effective interaction sites. Recent innovations employ enhanced sampling to bias along CG degrees of freedom for data generation, then recompute forces with respect to the unbiased potential [31]. This strategy simultaneously shortens simulation time required for equilibrated data and enriches sampling in transition regions while preserving the correct potential of mean force [31].

Experimental Protocols and Implementation

True Reaction Coordinate Identification Protocol

The identification of true reaction coordinates represents a cutting-edge methodology for optimal enhanced sampling. The protocol involves:

Potential Energy Flow Analysis: The motion of each coordinate is governed by its equation of motion, generated by the mechanical work done on the coordinate [28]. For coordinate qi, the energy cost of its motion (potential energy flow) is calculated as dWi = -∂U(q)/∂qi·dqi. During protein conformational changes, true reaction coordinates incur the highest energy cost for overcoming activation barriers [28].

Generalized Work Functional Method: This method generates an orthonormal coordinate system called singular coordinates that disentangle true reaction coordinates from non-essential coordinates by maximizing potential energy flows through individual coordinates [28]. Consequently, true reaction coordinates are identified as the singular coordinates with the highest potential energy flows.

Energy Relaxation Simulations: A breakthrough methodology enables computation of true reaction coordinates from energy relaxation simulations alone, rather than requiring natural reactive trajectories [28]. This approach leverages the dual control of true reaction coordinates over both conformational changes and energy relaxation.

Bayesian Free-Energy Reconstruction Protocol

The Bayesian free-energy reconstruction methodology provides an automated approach for thermodynamic property prediction:

MD Simulation Ensemble: Perform NVT-MD simulations at multiple (V,T) state points, which can be irregularly spaced throughout the volume-temperature phase space of interest [29].

Data Extraction: From each simulation, extract ensemble-averaged potential energies and pressures, which correspond to derivatives of the Helmholtz free energy [29].

Gaussian Process Regression: Reconstruct the complete Helmholtz free-energy surface F(V,T) using Gaussian Process Regression, which naturally handles irregularly spaced data points and propagates statistical uncertainties [29].

Active Learning Iteration: Implement an active learning loop that identifies regions of high uncertainty in the free-energy surface and automatically selects new (V,T) points for additional simulation to optimize sampling efficiency [29].

Quantum Correction: Apply zero-point energy corrections derived from harmonic or quasi-harmonic theory to account for nuclear quantum effects, essential for low-temperature accuracy [29].

Property Calculation: Compute thermodynamic properties including heat capacity, thermal expansion, and bulk moduli from derivatives of the reconstructed free-energy surface, with all predictions accompanied by quantified confidence intervals [29].

Performance Comparison and Benchmarking

Acceleration Factors and Sampling Efficiency

Enhanced sampling methods demonstrate remarkable acceleration capabilities for challenging biomolecular processes:

True Reaction Coordinate Performance: Application of true reaction coordinate biasing to HIV-1 protease flap opening and ligand unbinding—a process with an experimental lifetime of 8.9×10^5 seconds—achieved acceleration to 200 picoseconds in simulation [28]. This represents an effective speedup of approximately 10^15-fold, enabling access to previously impossible timescales.

Cryptic Pocket Discovery: Molecular dynamics-based approaches for cryptic pocket identification, including mixed solvent MD and Markov state models, successfully reveal transient binding sites in proteins like TEM-1 β-lactamase [32]. These cryptic pockets offer novel strategies for combating antibiotic resistance through allosteric regulation and avoiding mutations at traditional active sites.

Free Energy Reconstruction Accuracy: The Bayesian free-energy reconstruction method has demonstrated robust performance across nine elemental FCC and BCC metals using 20 classical and machine-learned interatomic potentials [29]. The approach consistently delivers accurate predictions for heat capacities, thermal expansion, isothermal and adiabatic bulk moduli, and melting properties with quantified uncertainties.

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Comparison of Enhanced Sampling Methods

| Method/Application | System | Acceleration Factor | Key Quantitative Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| True Reaction Coordinates | HIV-1 protease | 10^15 | Reduced 8.9×10^5 s process to 200 ps |

| Bayesian Free-Energy | Elemental metals | N/A | Uncertainty-quantified thermodynamic properties |

| Cryptic Pocket Identification | TEM-1 β-lactamase | N/A | Revealed 2 cryptic pockets for allosteric regulation |

| NEP-MB-pol Water Model | Liquid water | N/A | Force RMSE: 69.77 meV/Å vs CCSD(T) |

Method-Specific Limitations and Considerations

Each enhanced sampling approach carries distinct limitations that researchers must consider when selecting methodologies:

CV-Based Methods: The performance of these methods is entirely dependent on CV selection. Poorly chosen CVs lead to inefficient sampling and the "hidden barrier" problem, where bias potentials miss actual activation barriers [28]. Additionally, identifying true reaction coordinates traditionally required natural reactive trajectories, creating a circular dependency [28].

Free Energy Reconstruction: This approach remains computationally demanding due to the need for multiple MD simulations across (V,T) space [29]. While active learning optimizes point selection, the fundamental requirement for extensive sampling persists.

Machine Learning Potentials: MLPs depend critically on the quality and comprehensiveness of reference data [30]. Models trained on different reference datasets (SCAN vs. MB-pol) show significant variations in accuracy for transport properties [30].

Coarse-Grained Methods: Bottom-up coarse-grained models trained via force matching rely on configurations sampled from unbiased equilibrium distributions, requiring long atomistic trajectories for convergence [31].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Key Computational Tools for Enhanced Sampling Research

| Tool/Resource | Type | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gaussian Process Regression | Algorithm | Bayesian reconstruction of free-energy surfaces | Uncertainty-aware thermodynamic property prediction |

| True Reaction Coordinates | Theoretical Framework | Optimal collective variables for barrier crossing | Maximum acceleration of conformational changes |

| Neuroevolution Potential | Machine Learning Potential | High-accuracy force field with quantum fidelity | Simultaneous prediction of thermodynamic/transport properties |

| Markov State Models | Analysis Framework | Kinetic model from simulation data | Identifying cryptic pockets and metastable states |

| Mixed Solvent MD | Simulation Method | Organic cosolvent-enhanced pocket discovery | Cryptic pocket identification for drug design |

| OpenKIM Repository | Database | Interatomic potentials with standardized testing | Systematic benchmarking of force fields |

| AiiDA/FireWorks | Workflow Manager | Automated simulation pipelines | High-throughput materials property screening |

Enhanced sampling methods have dramatically expanded the scope of molecular dynamics simulations, enabling researchers to address questions previously considered intractable due to timescale limitations. The comparative analysis presented in this guide demonstrates that method selection must be guided by specific research objectives: true reaction coordinates provide optimal acceleration for protein conformational changes; Bayesian free-energy reconstruction offers automated, uncertainty-quantified thermodynamic properties; and machine learning potentials deliver quantum-mechanical accuracy for complex fluids.

Future developments will likely focus on increasing method automation, improving uncertainty quantification, and enhancing integration with experimental data. As these computational techniques continue to mature, they will play an increasingly vital role in accelerating drug discovery, materials design, and fundamental scientific understanding across chemical and biological disciplines.

Automated Workflows and Bayesian Methods for Uncertainty-Aware Predictions