AMBER vs CHARMM vs OPLS: A Comprehensive Guide to Force Field Performance for Biomolecular Simulations

This article provides a systematic comparison of AMBER, CHARMM, and OPLS force fields, essential tools for molecular dynamics simulations in drug discovery and structural biology.

AMBER vs CHARMM vs OPLS: A Comprehensive Guide to Force Field Performance for Biomolecular Simulations

Abstract

This article provides a systematic comparison of AMBER, CHARMM, and OPLS force fields, essential tools for molecular dynamics simulations in drug discovery and structural biology. We explore their foundational philosophies, parameterization methodologies, and practical application protocols. The content addresses common troubleshooting scenarios and optimization strategies, supported by validation data from recent benchmarking studies on protein dynamics, small molecule hydration free energies, and liquid properties. Designed for researchers and computational chemists, this guide empowers informed force field selection to enhance the reliability of simulation outcomes in biomedical research.

Force Field Foundations: Understanding the Philosophies Behind AMBER, CHARMM, and OPLS

Core Principles and Historical Development of Each Force Field

Molecular mechanics force fields serve as the fundamental mathematical models that describe the potential energy surfaces of molecular systems, enabling the study of biomolecular structure, dynamics, and interactions through molecular dynamics simulations. Among the most widely used families are AMBER, CHARMM, and OPLS - each with distinct philosophical approaches, development histories, and application strengths. Understanding their core principles, parametric differences, and performance characteristics is essential for researchers to select the appropriate force field for specific biological questions, particularly in drug discovery where accurate prediction of molecular interactions is critical. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of these three force fields, highlighting their historical development, theoretical foundations, and performance across various biomolecular systems.

Historical Development and Core Philosophies

AMBER (Assisted Model Building with Energy Refinement)

Origins and Timeline: The AMBER force field originated in the 1980s with Peter Kollman's group and has evolved through multiple versions. The widely used ff94 parameter set was published in the mid-1990s, followed by ff96, ff99, and the improved ff99SB variant which addressed limitations in secondary structure balance. More recent versions continue to refine backbone dihedral parameters and expand chemical coverage [1] [2].

Parametrization Philosophy: AMBER parameters were primarily optimized to reproduce gas-phase structures and conformational energetics from ab initio calculations of small molecules, with partial atomic charges derived by fitting to the electrostatic potential calculated at the Hartree-Fock 6-31G* level. This approach intentionally "overpolarizes" bond dipoles to approximate aqueous-phase charge distributions when combined with simple water models [1].

Key Development: The ff99SB refinement demonstrated the importance of properly balancing dihedral terms for different amino acids, particularly addressing the incorrect conformational preferences for glycine that plagued earlier versions. This was achieved by fitting φ/ψ dihedral terms to high-level QM calculations of glycine and alanine tetrapeptides [1].

CHARMM (Chemistry at HARvard Macromolecular Mechanics)

Origins and Timeline: The CHARMM force field was developed primarily to model proteins, with parametrization based on small molecule fragments used to model protein chemistry. Parameters were fitted to a wide range of experimental and ab initio data. The force field includes the Urey-Bradley contribution to angle terms and has seen continuous refinement through versions such as CHARMM22, CHARMM27, CHARMM36, and their modified variants [3] [4].

Parametrization Philosophy: Unlike OPLS-AA, charges in the CHARMM force field are derived from fitting solute-water energies to ab initio data, making it particularly optimized for modeling systems including solvent and/or bio-molecules. This philosophy makes CHARMM well-suited for biomolecular simulations where aqueous solvation is critical [3].

Key Development: Recent CHARMM variants have incorporated grid-based energy correction maps for treating conformation properties of the protein backbone, enhancing its ability to model complex biomolecular systems. The CHARMM General Force Field (CGENFF) extends its application to drug-like molecules [3] [5].

OPLS (Optimized Potentials for Liquid Simulations)

Origins and Timeline: The OPLS force field was developed by Jorgensen and colleagues, with the all-atom OPLS-AA representing an improvement over the original united-atom version. The force field was specifically optimized for simulating organic liquids and gas-phase interactions, with non-bonded parameters determined from a dataset of 34 pure organic liquids [3] [6].

Parametrization Philosophy: OPLS-AA featured more added sites for non-bonded interactions to increase flexibility for charge distribution and torsional energetics. Its development prioritized accurately reproducing thermodynamic properties of pure organic liquids, particularly densities and heats of vaporization, achieving average errors of about 2% for these properties [3] [6].

Key Development: Recent versions like OPLS3e have dramatically expanded chemical coverage by increasing the number of torsion types to over 146,000, while OPLS4 introduced tools for refining torsion terms for molecules beyond predetermined lists. This extensive parametrization has made OPLS particularly valuable for small molecule drug discovery applications [7].

Theoretical Foundations and Mathematical Formulations

The mathematical representation of potential energy varies among force fields, reflecting their different philosophies and optimization targets.

Table 1: Comparison of Force Field Functional Forms

| Force Field | Bond & Angle Terms | Dihedral Treatment | Special Features | Non-bonded Combining Rules |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMBER | Harmonic potentials | Fourier series for torsions | No explicit hydrogen bonding term | Standard Lorentz-Berthelot |

| CHARMM | Harmonic potentials + Urey-Bradley term | Multiple Fourier terms | Urey-Bradley contribution; grid-based correction maps | Modified rules for specific interactions |

| OPLS-AA | Harmonic potentials | Fourier series with V1, V2, V3 coefficients | Optimized for organic liquid properties | Geometric mean for both σ and ε |

Energy Function Formulations

OPLS-AA Potential Energy Function: The OPLS-AA potential energy is described as:

The combining rules are σᵢⱼ = √(σᵢᵢσⱼⱼ) and εᵢⱼ = √(εᵢᵢεⱼⱼ) [3].

CHARMM Potential Energy Function: The CHARMM potential energy has a more complex form:

This includes a Urey-Bradley term (KUB) for 1,3-interactions not present in other force fields [3].

Dihedral Parameterization Challenges

A critical difference in dihedral treatment emerges in AMBER force fields, where two sets of backbone φ/ψ dihedral terms exist:

- For glycine: φ = C-N-Cα-C and ψ = N-Cα-C-N

- For other amino acids: Additional dihedrals φ' = C-N-Cα-Cβ and ψ' = Cβ-Cα-C-N

This implementation means that modifications to φ/ψ parameters optimized for alanine (which has the additional terms) may perform poorly for glycine, which lacks these terms. This issue contributed to imbalances in early AMBER versions and highlights the complexity of transferable parameter development [1].

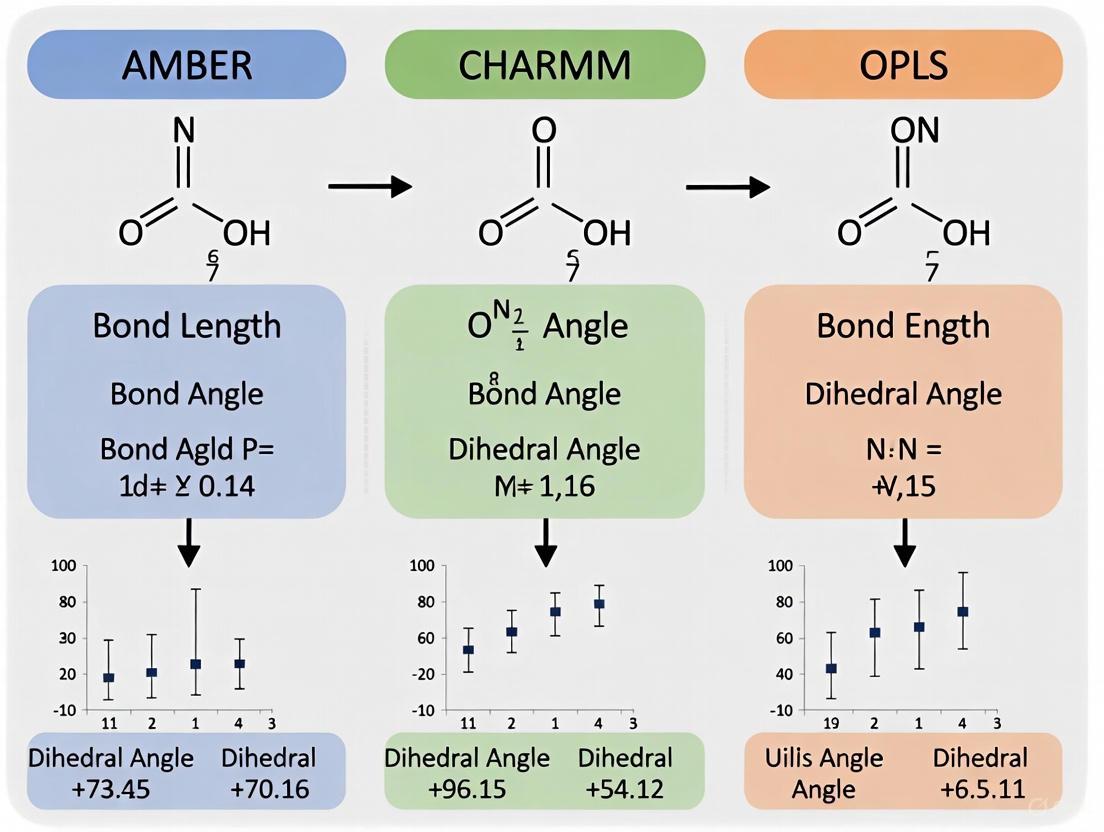

Figure 1: Relationship between parameterization sources and force field applications. Each force field weights different parameterization sources, leading to specialized application strengths.

Performance Comparison in Biomolecular Simulations

Accuracy in Solvation Free Energies

A comprehensive benchmark study evaluated nine condensed-phase force fields against experimental cross-solvation free energies, providing quantitative performance comparisons:

Table 2: Force Field Performance in Solvation Free Energy Prediction [5]

| Force Field | Correlation Coefficient | RMSE (kJ mol⁻¹) | Average Error (kJ mol⁻¹) | Relative Ranking |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OPLS-AA | 0.88 | 2.9 | -1.5 | 1 (Best) |

| GROMOS-2016H66 | 0.87 | 2.9 | +1.0 | 1 (Best) |

| AMBER-GAFF2 | 0.85 | 3.3 | -0.6 | 3 (Middle) |

| AMBER-GAFF | 0.84 | 3.6 | -0.6 | 3 (Middle) |

| CHARMM-CGenFF | 0.80 | 4.0 | -0.6 | 4 (Lower) |

The study revealed that OPLS-AA and GROMOS-2016H66 showed the best accuracy in predicting solvation free energies, while CHARMM-CGenFF presented somewhat higher errors. Both AMBER-GAFF and GAFF2 showed intermediate performance [5].

Performance in Intrinsically Disordered Protein Simulations

A 2023 benchmark study assessing 13 force fields for simulating the intrinsically disordered R2-FUS-LC region found significant variations in performance:

CHARMM Family: CHARMM36m2021 with mTIP3P water model emerged as the most balanced force field, capable of generating various conformations compatible with known structures. CHARMM force fields generally tended to generate more extended conformations compared to AMBER force fields [8].

AMBER Family: AMBER force fields demonstrated a tendency to generate more compact conformations with more non-native contacts. The a99SB-disp and a99SB-ILDN force fields showed good performance but with slight over-compaction compared to experimental data [8].

Scoring Methodology: The study employed a comprehensive scoring system evaluating radius of gyration (global compactness), secondary structure propensity, and contact maps. Top-performing force fields achieved medium to high scores (>0.3) across all measures, while poorer performers showed inconsistent performance across different metrics [8].

Thermodynamic Property Prediction

Studies comparing force fields for predicting thermodynamic properties of specific compounds reveal context-dependent performance:

In vapor-liquid equilibrium predictions for m-cresol, both OPLS-AA and TraPPE-UA force fields showed strengths in different areas. OPLS-AA demonstrated excellent agreement with experimental latent heats of vaporization and liquid densities (∼3.4% and 1.2% deviations respectively), while TraPPE-UA showed advantages in predicting critical parameters and coexistence densities [6].

For benzene simulations, OPLS-AA with 12 LJ interaction sites and partial charges assigned to each site underestimated critical temperature and density by 25K and 0.043 g/cc respectively, while TraPPE-UA with a rigid aromatic ring and no partial charges showed better agreement with experimental vapor-liquid coexistence curves [6].

Application to Drug Discovery

Small Molecule Parameterization

The parameterization of small molecule ligands presents distinct challenges for force fields:

AMBER Family: The General Amber Force Field (GAFF) and its successor GAFF2 provide broad coverage for drug-like molecules. Recent developments like ByteFF employ data-driven approaches using graph neural networks trained on 2.4 million optimized molecular fragments to predict parameters across expansive chemical space, addressing the limitation of traditional look-up table approaches [7].

CHARMM Family: The CHARMM General Force Field (CGenFF) enables parameterization of drug-like molecules compatible with CHARMM biomolecular force fields. Its atom typing and parameter assignment philosophy maintains consistency with the broader CHARMM framework [5].

OPLS Family: OPLS3e and OPLS4 have extensive parametrization for small molecules, with OPLS3e incorporating over 146,000 torsion types to enhance accuracy and chemical space coverage. The force field's optimization for liquid properties makes it particularly valuable for predicting solvation and binding free energies in drug discovery [7].

Free Energy Calculations

In free energy perturbation (FEP) calculations now routinely used for evaluating ligand-target binding affinities, the accuracy of force fields becomes critically important:

Recent advances have made FEP calculations capable of achieving reasonable precision, but this precision is inherently limited by force field accuracy. Consistency between protein and ligand force field parameters is essential for reliable results [4].

The expansion of chemical space explored in modern drug discovery, including molecular glues and PROTACs, creates new demands on force fields to accurately describe complex three-body systems in target-ligand-target simulations [4].

Emerging Trends and Future Directions

Automation in Force Field Development

Traditional manual, labor-intensive parameterization processes are being supplemented by automated approaches:

Machine Learning Approaches: Methods like Espaloma introduce end-to-end workflows where force field parameters are predicted by graph neural networks. ByteFF demonstrates how large-scale QM datasets (2.4 million optimized fragments + 3.2 million torsion profiles) can train models to predict parameters with expansive chemical space coverage [7].

SMIRKS-Based Approaches: The OpenFF initiative utilizes SMIRKS patterns to describe chemical environments for both bonded and non-bonded terms, moving beyond traditional atom typing limitations [7].

Polarizable Force Fields

Fixed-charge additive force fields are increasingly supplemented by polarizable models:

While additive all-atom force fields with fixed partial charges remain the most routinely used, polarizable force fields that explicitly account for electronic polarization effects offer improved physical representation, particularly for heterogeneous environments like membrane interfaces or binding pockets [4].

Development of polarizable versions for major force fields includes the CHARMM-Drude model and AMBER-based polarizable force fields, though computational demands remain higher than additive models [4].

Integration with Machine Learning Potentials

The landscape of force field development is being transformed by machine learning:

Machine learning force fields (MLFFs) using neural networks can capture subtle interactions overlooked by classical models but face challenges in computational efficiency and data requirements [7].

Synergy between physical force fields and ML approaches is emerging, with attempts to use atomistic forces from conventional FFs to guide protein conformation generation via diffusion models, and using ML-predicted parameters to enhance traditional physical models [4] [7].

Table 3: Key Software Tools for Force Field Applications

| Tool Name | Force Field Compatibility | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| CGENFF | CHARMM | Parameter assignment for drug-like molecules | Small molecule parameterization for CHARMM simulations |

| GAFF/GAFF2 | AMBER | General parameterization of organic molecules | Small molecule parameterization for AMBER simulations |

| FFBuilder | OPLS | Refinement of torsion terms beyond predetermined lists | Extending OPLS coverage to novel chemical entities |

| ByteFF | AMBER-compatible | Data-driven parameter prediction using GNN | High-throughput parameterization across expansive chemical space |

| pmemd | AMBER | GPU-accelerated molecular dynamics engine | High-performance biomolecular simulations |

| OpenFF | Open Force Fields | SMIRKS-based parameter assignment | Flexible chemical description beyond atom typing |

The AMBER, CHARMM, and OPLS force fields represent distinct philosophical approaches to biomolecular simulation, with historical developments that have shaped their respective strengths and limitations. AMBER has excelled for proteins and nucleic acids, CHARMM for solvated biomolecular systems and membranes, and OPLS for organic molecules and solvation properties. Contemporary benchmarks reveal that each can demonstrate superior performance in specific applications, with OPLS-AA showing advantages in solvation free energy prediction, CHARMM36m2021 performing well for intrinsically disordered proteins, and AMBER-family force fields maintaining strong performance for folded protein systems. The ongoing evolution of these force fields through automation, machine learning integration, and expansion of chemical coverage promises to further enhance their accuracy and applicability across the diverse challenges of modern drug discovery and structural biology.

Comparing Energy Functions and Functional Forms

Molecular mechanics force fields are fundamental to computational chemistry and biology, providing the energy functions that drive molecular dynamics (MD) simulations and other computational studies. The accuracy of these simulations in predicting biological phenomena, material properties, and thermodynamic behavior is intrinsically linked to the functional forms and parameterization of the underlying force fields. Among the most widely used families are AMBER, CHARMM, and OPLS, each with distinct philosophical approaches to energy function formulation and parameter derivation. This guide provides an objective comparison of these force fields, synthesizing data from recent benchmarking studies across diverse biological and chemical systems to inform researchers and drug development professionals in selecting appropriate models for their specific applications. Performance varies significantly based on the system being studied and the properties of interest, necessitating careful force field selection grounded in empirical validation.

Force Field Performance Across Systems

Benchmarking studies consistently demonstrate that the performance of a force field is highly system-dependent. The tables below summarize key findings from recent investigations into force field accuracy for different types of molecules and materials.

Table 1: Performance Comparison for Biomolecular Systems

| Force Field | Test System | Key Performance Metrics | Rank/Outcome | Primary Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CHARMM36m2021s3p | R2-FUS-LC (IDP) | Radius of gyration, secondary structure, contact maps | Top-ranked (most balanced) | [8] |

| AMBER a19sbopc | R2-FUS-LC (IDP) | Radius of gyration, secondary structure, contact maps | Top-tier (consistent performance) | [8] |

| AMBER a99sb4pew | R2-FUS-LC (IDP) | Radius of gyration | Top-tier (bias toward compact conformations) | [8] |

| CHARMM c36ms3p | R2-FUS-LC (IDP) | Radius of gyration | Top-tier (bias toward flexible conformations) | [8] |

| AMBER ff99sb-ildn-nmr | Ubiquitin, Peptides | NMR chemical shifts and J-couplings | Highest accuracy | [9] |

| AMBER ff99sb-ildn-phi | Ubiquitin, Peptides | NMR chemical shifts and J-couplings | Highest accuracy | [9] |

| CHARMM27 | Ubiquitin, Peptides | NMR chemical shifts and J-couplings | Moderate accuracy | [9] |

| OPLS-AA | Ubiquitin, Peptides | NMR chemical shifts and J-couplings | Moderate accuracy | [9] |

Table 2: Performance Comparison for Small Organic Molecules and Materials

| Force Field | Test System | Key Performance Metrics | Rank/Outcome | Primary Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TraPPE-UA | m-Cresol (Organic) | Vapor-liquid coexistence, density, critical temperature | Excellent for liquid density and Tc | [6] |

| OPLS-AA | m-Cresol (Organic) | Vapor-liquid coexistence, density, critical temperature | Accurate at lower temperatures only | [6] |

| PCFF | Polyamide Membranes | Young's modulus, pure water permeation | Best for hydrated membrane properties | [10] |

| CVFF | Polyamide Membranes | Young's modulus, structural properties | Best for dry membrane properties | [10] |

| SwissParam | Polyamide Membranes | Structural characterization | Moderate accuracy | [10] |

| CGenFF | Polyamide Membranes | Structural characterization | Moderate accuracy | [10] |

| GAFF | Polyamide Membranes | Water permeation, salt rejection | Lower accuracy | [10] |

| DREIDING | Polyamide Membranes | Water permeation, salt rejection | Lower accuracy | [10] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Benchmarking Intrinsically Disordered Proteins

The evaluation of force fields for intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs) like the R2-FUS-LC region requires specific protocols to assess their ability to sample highly flexible conformational ensembles. The following diagram illustrates the workflow of a comprehensive benchmarking study:

Figure 1: Workflow for benchmarking force fields on intrinsically disordered proteins.

The methodology involves several critical stages [8]:

- System Preparation: The R2-FUS-LC region (residues 50-65) was modeled as a trimer of 16-residue peptides, representing the core amyloid-forming unit.

- Simulation Parameters: For each of the 13 force fields evaluated, six independent MD simulations of 500 ns each (totaling 3 μs per force field) were conducted to ensure adequate sampling of conformational space.

- Reference Data: Experimental reference data included U-shaped (NMR, PDB: 5W3N) and L-shaped (cryo-EM, PDB: 7VQQ) conformations with known radii of gyration (10.0 Å and 14.4 Å, respectively), along with unfolded state estimates from Flory's random coil model.

- Analysis Metrics:

- Radius of Gyration (Rg): Assessed global compactness by fitting distributions to two Gaussian functions and calculating Z-scores relative to reference structures.

- Secondary Structure Propensity (SSP): Evaluated local conformational preferences.

- Intra-peptide Contact Maps: Analyzed residue-specific interactions.

- Scoring System: A composite score derived from all three metrics was used to rank force fields into top, middle, and bottom tiers.

Validating Against NMR Observables

For folded proteins and peptides, validation against NMR data provides a rigorous test of force field accuracy. The protocol for systematic NMR validation includes [9]:

- Diverse Benchmark Set: 32 protein systems including capped dipeptides (Ace-X-NME, X ≠ P), tripeptides (XXX, GYG), alanine tetrapeptide, and ubiquitin.

- Comprehensive NMR Data: 524 measurements of chemical shifts and scalar couplings (³JHNHα, ³JHNCβ, ³JHαC′, ³JHNC′, and ³JHαN) aggregated from the BioMagRes Database and recent literature.

- Simulation Conditions: Each system was simulated using all combinations of 11 force fields and 5 water models (55 total combinations). Production simulations were 25 ns in length (20 ns for dipeptides) at constant temperature and pressure matching experimental conditions.

- NMR Prediction: J-couplings were estimated using empirical Karplus relations, while chemical shifts were predicted using the Sparta+ program.

- Statistical Analysis: Accuracy was quantified using an uncertainty-weighted objective function (χ² = Σᵢ[(xᵢᴱˣᵖᵗ - xᵢ)²/σᵢ²]), where σᵢ represents the uncertainty in the relationship between conformation and NMR observable.

Assessing Thermodynamic Properties

The evaluation of force fields for predicting thermodynamic properties of organic compounds like m-cresol employs different methodologies [6]:

- Simulation Technique: Gibbs ensemble Monte Carlo (GEMC) simulations are used to directly predict vapor-liquid coexistence without interface modeling.

- Target Properties: Simulations predict vapor pressure (Pₛₐₜ), latent heats of vaporization (ΔHᵥₐₚ), normal boiling point (Tᵦ), critical parameters (T꜀, P꜀, V꜀), and acentric factor (ω).

- Force Field Comparison: TraPPE-UA and OPLS-AA force fields are evaluated against limited experimental data, with particular attention to critical temperature and saturated liquid density predictions.

- Accuracy Metrics: Percentage deviations from experimental values are calculated, with TraPPE-UA typically accepting slightly higher error (<10%) for vapor pressure to prioritize accuracy in liquid density and critical temperature.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Tool/Reagent | Type | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| GROMACS | MD Software | High-performance molecular dynamics simulation | Biomolecular simulations, force field testing [11] [8] [9] |

| AMBER Tools | Software Suite | Force field parameterization and simulation | Biomolecular simulation, GAFF for small molecules [11] |

| CHARMM | Software Suite | Molecular dynamics simulation and analysis | Biomolecular systems with CHARMM force fields [11] |

| BOSS/MCPRO | Software Suite | Monte Carlo simulations for condensed phases | OPLS force field implementations [11] |

| TIP3P | Water Model | Explicit solvent representation | Standard 3-point water model [11] [8] [9] |

| TIP4P | Water Model | Explicit solvent representation | 4-point water model with improved properties [8] [10] [9] |

| mTIP3P | Water Model | Modified TIP3P for CHARMM | CHARMM simulations with improved efficiency [8] |

| SPARTA+ | Analysis Tool | Chemical shift prediction from structures | NMR validation of force fields [9] |

| Antechamber | Tool Suite | General Amber Force Field (GAFF) parameterization | Small molecule parameterization for AMBER [11] |

This comparison guide demonstrates that force field performance is intrinsically linked to the specific system and properties under investigation. For intrinsically disordered proteins like the R2-FUS-LC region, CHARMM36m2021 with mTIP3P water emerges as the most balanced option, while select AMBER variants also perform well [8]. For folded proteins and peptides where NMR validation is critical, AMBER ff99sb-ildn-nmr and ff99sb-ildn-phi achieve the highest accuracy [9]. For organic compounds like m-cresol, TraPPE-UA provides superior vapor-liquid coexistence properties, while OPLS-AA is limited to lower-temperature applications [6]. For polyamide membrane systems, PCFF outperforms other force fields for hydrated membrane properties, while CVFF is optimal for dry state characterization [10]. These findings underscore the importance of selecting force fields based on comprehensive benchmarking studies relevant to one's specific research domain rather than assuming universal transferability of performance across different chemical and biological contexts.

Distinct Parameterization Philosophies and Target Data

Molecular mechanics force fields are foundational to computational chemistry and drug discovery, providing the mathematical models that describe the potential energy surfaces of molecular systems. The accuracy of molecular dynamics (MD) simulations in predicting properties ranging from protein folding to solvation free energies is intrinsically linked to the underlying force field and its parameterization philosophy. The AMBER, CHARMM, and OPLS families represent three predominant force field paradigms in biomolecular simulation, each with distinct approaches to parameter derivation, optimization targets, and intended applications. Understanding their philosophical foundations, performance characteristics, and limitations is essential for researchers selecting appropriate models for specific scientific inquiries. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of these force fields, examining their parameterization methodologies, performance against experimental and quantum mechanical benchmarks, and relevance to contemporary drug development challenges.

Parameterization Philosophies and Historical Development

Foundational Principles and Optimization Targets

The AMBER, CHARMM, and OPLS force fields share common functional forms but diverge significantly in their parameterization philosophies and target data, leading to distinct performance characteristics across different molecular classes and properties.

OPLS (Optimized Potentials for Liquid Simulations) employs a philosophy centered on reproducing thermodynamic properties of organic liquids. The non-bonded parameters in OPLS-AA were determined from a dataset of 34 pure organic liquids, including alkanes, alkenes, alcohols, ethers, and various organic compounds containing other functional groups [6]. The force field prioritizes accurate prediction of liquid densities and latent heats of vaporization, with average errors of approximately 2% for these properties [6]. OPLS development has emphasized the accurate representation of gas-phase structures and conformational energetics from ab initio calculations alongside thermodynamic properties of pure organic liquids [3]. Recent versions like OPLS3e have dramatically expanded torsion parameter coverage to over 146,669 types to enhance accuracy and chemical space coverage [7].

CHARMM (Chemistry at Harvard Macromolecular Mechanics) adopts a biomolecule-centric approach with parameterization based on small molecule fragments representing protein building blocks. The force field includes the Urey-Bradley contribution and has recently incorporated grid-based energy correction maps for treating conformation properties of protein backbone [3]. CHARMM charges are derived from fitting solute-water energies to ab initio data, optimizing them for aqueous environments [3]. The CHARMM General Force Field (CGenFF) extends this philosophy to drug-like molecules using a trained bond-angle-dihedral charge increment linear interpolation scheme for partial atomic charges along with bonded parameters assigned based on analogy using a rules-based penalty score scheme [12].

AMBER (associated with the Assisted Model Building with Energy Refinement suite) originally prioritized protein and nucleic acid simulations. The ff94 force field, one of the most widely used AMBER parameter sets, derived its partial atomic charges by fitting the electrostatic potential calculated at the Hartree-Fock 6-31G* level, intentionally "overpolarizing" bond dipoles to approximate aqueous condensed phase environments [1]. AMBER's dihedral parameters were initially fit to a limited set of low-energy conformations of glycine and alanine dipeptides, which later required corrections to address secondary structure imbalances [1]. The force field has evolved through multiple iterations (ff96, ff99, ff99SB, ff03) to improve conformational sampling of backbone dihedrals and balance secondary structure preferences.

Table 1: Historical Development of Major Force Field Families

| Force Field | Initial Release | Primary Initial Focus | Key Evolutionary Steps |

|---|---|---|---|

| OPLS | 1980s (OPLS-UA) | Organic liquid thermodynamics | OPLS-AA (all-atom), OPLS-2005, OPLS3e, OPLS4 |

| CHARMM | 1980s | Proteins and nucleic acids | CHARMM22, CHARMM27, CHARMM36, CGenFF |

| AMBER | 1980s (ff94) | Proteins and nucleic acids | ff96, ff99, ff99SB, ff02, ff03, ff14SB, ff19SB |

Functional Forms and Mathematical Differences

The mathematical implementation of these force fields reveals fundamental philosophical differences:

OPLS-AA utilizes a potential energy function comprising bond, angle, torsion, and non-bonded terms with combining rules such that σij = (σiiσjj)^1/2 and εij = (εiiεjj)^1/2 for Lennard-Jones interactions between unlike atoms [3].

CHARMM incorporates a similar harmonic potential for bonds and angles but includes additional terms such as the Urey-Bradley component for 1,3-interactions and employs a different approach to dihedral and non-bonded interactions [3]. The force field uses the standard 6-12 Lennard-Jones potentials for van der Waals interactions and Coulombic potential for electrostatic interactions, with Rmin representing the distance between atoms at the Lennard-Jones minimum and εij as the well depth [3].

AMBER follows a functional form similar to OPLS but has historically employed different combining rules and treatment of electrostatic interactions. The ff99SB correction specifically addressed imbalances in backbone dihedral parameters that led to over-stabilization of α-helical structures, demonstrating the critical importance of proper torsion parameterization for accurate secondary structure representation [1].

Performance Comparison and Experimental Validation

Thermodynamic Properties and Liquid-State Behavior

Validation against experimental thermodynamic properties provides critical insights into force field performance. A comprehensive assessment of nine condensed-phase force fields against experimental cross-solvation free energies revealed significant differences in accuracy [5].

Table 2: Performance Comparison in Predicting Solvation Free Energies (RMSE in kJ mol⁻¹)

| Force Field | Family | RMSE | Correlation Coefficient | Average Error |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GROMOS-2016H66 | GROMOS | 2.9 | 0.88 | +1.0 |

| OPLS-AA | OPLS | 2.9 | 0.88 | -1.5 |

| OPLS-LBCC | OPLS | 3.3 | 0.87 | -1.0 |

| AMBER-GAFF2 | AMBER | 3.4 | 0.86 | +0.5 |

| AMBER-GAFF | AMBER | 3.5 | 0.85 | +0.3 |

| OpenFF | OpenFF | 3.6 | 0.84 | +0.7 |

| GROMOS-54A7 | GROMOS | 4.0 | 0.81 | -0.8 |

| CHARMM-CGenFF | CHARMM | 4.2 | 0.79 | +0.2 |

| GROMOS-ATB | GROMOS | 4.8 | 0.76 | -0.5 |

The table shows that OPLS-AA achieves the best accuracy alongside GROMOS-2016H66 for solvation free energy prediction, reflecting its original optimization for liquid-phase thermodynamics [5]. CHARMM-CGenFF shows moderately higher errors, potentially reflecting its focus on biomolecular interactions rather than small organic molecule solvation.

In the context of vapor-liquid coexistence properties for organic compounds like m-cresol, OPLS-AA demonstrates accurate prediction of latent heats of vaporization and liquid densities, consistent with its design objectives [6]. However, comparative studies indicate that for vapor-liquid coexistence curves (VLCC), the TraPPE force field generally outperforms both OPLS-AA and CHARMM in reproducing liquid densities and critical temperatures [13].

Biomolecular Simulations and Secondary Structure Balance

For protein simulations, secondary structure preferences serve as critical validation metrics. The AMBER ff94 and ff99 force fields exhibited systematic biases, with significant over-stabilization of α-helical structures observed in multiple studies [1]. This limitation prompted the development of ff99SB, which reparameterized backbone dihedral parameters based on fitting energies of multiple conformations of glycine and alanine tetrapeptides from high-level ab initio quantum mechanical calculations [1].

The improper handling of glycine parameters in several AMBER force field variants highlights the complexity of balanced parameterization. Earlier modifications neglected the existence in AMBER of two sets of backbone φ/ψ dihedral terms, leading to unreasonable conformational preferences for glycine [1]. The ff99SB correction specifically addressed this issue while improving agreement with experimental NMR relaxation data of test protein systems [1].

CHARMM force fields have generally demonstrated good performance in biomolecular simulations, with C36 parameters widely adopted for membrane-protein systems. Recent specialized developments like BLipidFF for mycobacterial membranes extend the CHARMM philosophy to complex bacterial lipid systems, capturing unique properties like tail rigidity and diffusion rates consistent with biophysical experiments [14].

Solid-State and Pharmaceutical Applications

In pharmaceutical applications, particularly for crystalline active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs), force field performance directly impacts predictive accuracy for properties like solubility, polymorphism, and stability. A recent study developing force field parameters for organosulfur and organohalogen APIs used OPLS-AA as the starting point, supplemented with missing dihedral parameters from MP2/aug-cc-pVDZ potential energy surface scans [15]. The validation against experimental sublimation enthalpies and single crystal X-ray diffraction data demonstrated the critical importance of parameter completeness and appropriate partial charge assignment for solid-state accuracy [15].

The study found that a procedure based on the ChelpG methodology, with inclusion of X-sites mimicking the σ-hole for iodine, provided the best overall accuracy for unit cell dimensions and sublimation enthalpy predictions [15]. This highlights how force field parameterization must sometimes be tailored to specific chemical features not adequately covered by general parameter sets.

Methodologies for Force Field Validation

Benchmarking Against Experimental Data

Comprehensive force field validation requires multiple experimental benchmarks:

Liquid-state properties including densities, enthalpies of vaporization, and free energies of solvation provide fundamental validation of non-bonded parameter quality [5]. The matrix of cross-solvation free energies implemented by Kashefolgheta et al. offers a systematic approach for evaluating the balance of solute-solvent interactions [5].

Vapor-liquid coexistence curves (VLCC) provide stringent tests of transferable force fields, with critical temperature, pressure, and density serving as key metrics [6] [13]. Early force field comparisons revealed that TraPPE most accurately reproduced liquid densities across multiple organic compounds, while OPLS-AA performed well for alcohols and CHARMM showed strengths for biomolecular building blocks [13].

Crystalline properties validation against experimental sublimation enthalpies and unit cell parameters, as demonstrated in API studies, is essential for pharmaceutical applications [15]. This ensures accurate modeling of solid-state interactions crucial for predicting polymorphism, solubility, and stability.

Quantum Mechanical Benchmarks

Quantum mechanical calculations provide high-resolution benchmarks for force field validation:

Conformational energies from high-level QM calculations serve as references for assessing torsional parameter accuracy. The development of ff99SB utilized QM energies of glycine and alanine tetrapeptides to correct backbone dihedral imbalances [1].

Interactions with water molecules, including energies and geometries, validate electrostatic models and hydrogen bonding parameters. CHARMM's approach of fitting charges to solute-water interaction energies directly optimizes for aqueous environments [3].

Hessian matrices and vibrational frequencies validate bonded parameters, ensuring accurate representation of molecular vibrations and flexibility [7].

Diagram 1: Force Field Development and Validation Workflow. This diagram illustrates the iterative process of force field parameterization, highlighting the critical role of both experimental and quantum mechanical target data in optimization and validation cycles.

Emerging Trends and Future Directions

Data-Driven Parameterization Approaches

Traditional look-up table approaches to force field development face significant challenges in covering the rapidly expanding synthetically accessible chemical space. This has motivated data-driven parameterization using modern machine learning techniques [7]. The ByteFF initiative represents this new paradigm, employing an edge-augmented, symmetry-preserving molecular graph neural network (GNN) trained on 2.4 million optimized molecular fragment geometries with analytical Hessian matrices and 3.2 million torsion profiles [7].

Similarly, the Espaloma approach introduces an end-to-end workflow where molecular mechanics force field parameters are predicted by graph neural networks, demonstrating improved accuracy over traditional methods for diverse chemical spaces [7]. These methods address key limitations of discrete chemical environment descriptions in traditional force fields, enhancing both transferability and scalability.

Expanded Training Sets and Specialized Force Fields

Recent efforts have focused on expanding training sets to improve coverage of underrepresented chemical motifs. The CGenFF v5.0 update added 1,390 molecules representing connectivities new to existing CGenFF training compounds, resulting in improved agreement with QM intramolecular geometries, vibrations, dihedral potential energy scans, dipole moments, and interactions with water [12].

There is also growing recognition of the need for specialized force fields targeting specific molecular classes. BLipidFF for mycobacterial membrane components exemplifies this trend, demonstrating that general force fields often poorly capture unique properties of specialized biological systems [14]. The modular parameterization strategy combined with quantum mechanical calculations enabled accurate prediction of membrane properties consistent with biophysical experiments [14].

Transferability and Balanced Interactions

A persistent challenge in force field development remains achieving balanced interactions across diverse chemical space. As highlighted by validation against cross-solvation free energies, different force fields exhibit heterogeneous performance across compound classes [5]. Future developments will likely focus on improving this balance while maintaining transferability through more sophisticated parameter assignment methods that better capture chemical context.

Table 3: Key Computational Tools for Force Field Development and Application

| Tool Name | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| MCCCS Towhee | Monte Carlo molecular simulation | Vapor-liquid coexistence calculations [13] |

| CGENFF Program | CHARMM parameter generation | Automatic parameter assignment for drug-like molecules [3] [12] |

| Gaussian | Quantum chemical calculations | Reference data generation for parameter optimization [3] [15] [14] |

| LAMMPS | Molecular dynamics simulation | Force field validation and production simulations [3] |

| geomeTRIC | Geometry optimization | Quantum chemical workflow automation [7] |

| Multiwfn | Wavefunction analysis | RESP charge fitting [14] |

| RDKit | Cheminformatics | Molecular fragment generation and manipulation [7] |

| GaussView | Computational chemistry interface | Structure building and visualization [14] |

Diagram 2: Force Field Selection Framework. This decision pathway illustrates how research application domains guide appropriate force field selection, emphasizing the importance of matching force field strengths with specific scientific questions.

The distinct parameterization philosophies underlying AMBER, CHARMM, and OPLS force fields have led to specialized strengths tailored to different scientific applications. OPLS excels in modeling organic liquids and predicting solvation thermodynamics, reflecting its original optimization target. CHARMM provides robust performance for biomolecular systems, particularly proteins and membranes, with parameters optimized for aqueous environments. AMBER offers carefully balanced secondary structure preferences through iterative refinement of backbone dihedral parameters. Contemporary force field development is increasingly embracing data-driven approaches leveraging graph neural networks and expanded training sets to cover broader chemical spaces while maintaining accuracy. Researchers must carefully match force field capabilities to their specific scientific questions, employing appropriate validation protocols to ensure reliable results. The ongoing refinement of these fundamental tools continues to expand the frontiers of molecular simulation across drug discovery, materials science, and fundamental chemical research.

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations have become an indispensable tool in computational biology and drug discovery, enabling researchers to study the structure, dynamics, and interactions of biomolecular systems at atomic resolution. The accuracy of these simulations critically depends on the force field—the mathematical model that describes the potential energy of a system as a function of its atomic coordinates. Among the most widely used force fields in biomolecular simulations are AMBER (Assisted Model Building with Energy Refinement), CHARMM (Chemistry at HARvard Macromolecular Mechanics), and OPLS (Optimized Potentials for Liquid Simulations). Each force field has evolved through different philosophical approaches and parameterization strategies, leading to distinct strengths and limitations [16].

This guide provides an objective comparison of these three major force fields, focusing on their performance for proteins, nucleic acids, and compatible small molecules. We summarize quantitative benchmarking data from recent studies, detail experimental methodologies used for validation, and provide practical guidance for researchers selecting appropriate force fields for specific biomolecular applications.

Historical Context and Evolution

The development of biomolecular force fields has progressed significantly since the first modern force field (CFF) was introduced in 1968 [16]. Early force fields like ECEPP (1975) specifically targeted polypeptides and proteins, while Allinger's MM series (MM1-MM4, 1976-1996) focused on small and medium-sized organic molecules. The current workhorses of biomolecular simulation—AMBER, CHARMM, GROMOS, and OPLS—emerged as all-atom, fixed-charge force fields designed to balance accuracy with computational efficiency, enabling simulations of biologically relevant systems over extended timescales [16].

AMBER and CHARMM force fields were primarily developed for simulations of proteins and nucleic acids with emphasis on accurate description of structures and non-bonded energies. OPLS and GROMOS, meanwhile, placed greater emphasis on accurately reproducing thermodynamic properties such as heats of vaporization, liquid densities, and molecular solvation properties [16].

Parameterization Strategies

The fundamental differences between force fields stem from their distinct parameterization philosophies:

AMBER: Van der Waals parameters are derived from crystal structures and lattice energies, while atomic partial charges are fitted to quantum mechanical (QM) electrostatic potential without empirical adjustments using the RESP (Restrained Electrostatic Potential) approach [16]. Early versions like ff94 and ff99 showed limitations including overstabilization of α-helices, leading to subsequent refinements such as ff99SB [1].

CHARMM: Parameterization is based on small molecule fragments used to model protein chemistry, fitted to a wide range of experimental and ab initio data [3]. Charges are derived from fitting solute-water energies to ab initio data, optimizing water interactions [3]. CHARMM includes the Urey-Bradley contribution and recently incorporated grid-based energy correction maps for treating conformation properties of protein backbone [3].

OPLS: Development of non-bonded and torsional parameters specially aimed at reproducing gas-phase structures, conformational energetics from ab initio calculations, and thermodynamic properties of pure organic liquids (particularly density and heat of vaporization) [3]. The OPLS-AA force field featured more added sites for non-bonded interactions to increase flexibility for charge distribution and torsional energetics [3].

Performance Comparison for Proteins

Intrinsically Disordered Proteins

Intrinsically Disordered Proteins (IDPs) represent a significant challenge for force fields due to their lack of stable structure and exposure of nonpolar residues to solvent. A 2023 benchmark study assessed 13 force fields by simulating the R2 region of the FUS-LC domain (R2-FUS-LC region), an IDP implicated in ALS [8]. The study evaluated force fields based on radius of gyration (Rg), secondary structure propensity (SSP), and intra-peptide contact maps, combining these measures into a final score.

Table 1: Performance of Force Fields for IDPs (R2-FUS-LC Region)

| Force Field | Water Model | Rg Score | SSP Score | Contact Map Score | Final Score | Ranking Group |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c36m2021s3p | mTIP3P | 0.85 | 0.65 | 0.70 | 0.90 | Top |

| a99sb4pew | TIP4P-EW | 0.86 | 0.52 | 0.65 | 0.82 | Top |

| a19sbopc | OPC | 0.72 | 0.58 | 0.69 | 0.79 | Top |

| c36ms3p | TIP3P | 0.77 | 0.49 | 0.57 | 0.70 | Top |

| a99sbdisp | TIP4P-D | 0.56 | 0.51 | 0.56 | 0.61 | Middle |

| a99sbnm | TIP3P | 0.38 | 0.55 | 0.59 | 0.58 | Middle |

| a99sbcufixs3p | TIP3P | 0.58 | 0.42 | 0.49 | 0.53 | Middle |

| a03ws | TIP4P/2005 | 0.13 | 0.29 | 0.26 | 0.21 | Bottom |

| c27s3p | TIP3P | 0.19 | 0.25 | 0.21 | 0.20 | Bottom |

The study revealed that CHARMM36m2021 with mTIP3P water model was the most balanced force field, capable of generating various conformations compatible with known ones [8]. Additionally, the mTIP3P water model was computationally more efficient than four-site water models used with top-ranked AMBER force fields. The evaluation also showed that AMBER force fields tend to generate more compact conformations compared to CHARMM force fields but also more non-native contacts [8].

Early AMBER force fields (ff94, ff99) were found to over-stabilize α-helical conformations, while modifications like ff96 overestimated β-strand propensity [1]. This imbalance prompted systematic revisions to backbone dihedral parameters. The ff99SB correction achieved better balance of secondary structure elements, improving the distribution of backbone dihedrals for glycine and alanine with respect to PDB survey data [1].

A critical issue identified in AMBER force field development was the handling of glycine versus other amino acids. In AMBER, additional dihedral terms (φ' and ψ') branched out to the Cβ carbon influence rotation about φ/ψ bonds for non-glycine residues. This led to inconsistencies when modified backbone dihedral parameters were applied to glycine, as they were originally fit in the presence of these additional terms [1].

Performance Comparison for Small Molecules

General Small Molecule Force Fields

A 2020 benchmark study compared nine force fields from four families (GAFF, GAFF2, MMFF94, MMFF94S, OPLS3e, and Open Force Field versions) on their ability to reproduce QM geometries and energetics for 22,675 molecular structures of 3,271 small molecules [17].

Table 2: Performance of Small Molecule Force Fields

| Force Field | Family | Geometry RMSD (Å) | Energy Correlation (R²) | Relative Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OPLS3e | OPLS | 0.52 | 0.91 | Best |

| OpenFF 1.2 | OpenFF | 0.55 | 0.89 | Very Good |

| OpenFF 1.1 | OpenFF | 0.58 | 0.87 | Good |

| OpenFF 1.0 | OpenFF | 0.61 | 0.85 | Good |

| GAFF2 | AMBER | 0.64 | 0.82 | Moderate |

| GAFF | AMBER | 0.67 | 0.79 | Moderate |

| MMFF94S | MMFF | 0.69 | 0.76 | Moderate |

| MMFF94 | MMFF | 0.72 | 0.73 | Lower |

| SMIRNOFF99Frosst | OpenFF | 0.75 | 0.70 | Lowest |

The study concluded that OPLS3e performed best, with the latest Open Force Field Parsley release (OpenFF 1.2) approaching a comparable level of accuracy [17]. Established force fields such as MMFF94S and GAFF2 showed generally worse performance. The study also identified specific chemical groups that represented systematic outliers across different force fields, providing guidance for future force field development.

Torsional Potential Energy Surfaces

Torsional potentials are crucial for accurately modeling molecular conformations, particularly for drug molecules containing biaryl fragments. A 2020 study benchmarked four force fields and two neural network potentials for predicting torsional potential energy surfaces of 88 biaryls extracted from drug fragments [18].

Table 3: Torsional Potential Accuracy for Biaryl Drug Fragments

| Method | RMSD (kcal/mol) | MADB (kcal/mol) | Relative Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| ANI-1ccx | 0.5 ± 0.0 | 0.8 ± 0.1 | Best |

| ANI-2x | 0.5 ± 0.0 | 1.0 ± 0.2 | Excellent |

| CGenFF | 0.8 ± 0.1 | 1.3 ± 0.1 | Very Good |

| OpenFF | 0.7 ± 0.1 | 1.3 ± 0.1 | Very Good |

| GAFF | 1.2 ± 0.2 | 2.6 ± 0.5 | Moderate |

| OPLS | 3.6 ± 0.3 | 3.6 ± 0.3 | Poor |

Notably, neural network potentials (ANI-1ccx and ANI-2x) demonstrated systematically better accuracy and reliability than any traditional force fields [18]. Among the conventional force fields, CHARMM General Force Field (CGenFF) and OpenFF performed best, while OPLS showed the poorest performance for these specific systems.

Performance Comparison for Nucleic Acids

AMBER Refinements for Nucleic Acids

Nucleic acids present unique challenges for force field development, particularly regarding backbone conformation stability. The AMBER parm99 force field was found to overpopulate the α/γ = (g+,t) backbone conformation in long simulations (exceeding 10 ns) [19]. This limitation prompted the development of parmbsc0, a refinement that corrects these inaccuracies by fitting to high-level quantum mechanical data [19].

The validation of parmbsc0 involved extensive comparison with experimental data, including two of the longest trajectories published for DNA duplex at that time (200 ns each) and the largest variety of NA structures studied to date (15 different NA families and 97 individual structures) [19]. The total simulation time used for validation approached 1 μs of state-of-the-art molecular dynamics simulations in aqueous solution, establishing a new standard for nucleic acid force field validation.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Benchmarking Workflow

The force field benchmarking studies followed rigorous methodologies to ensure comprehensive and objective comparisons. A typical workflow involves:

Diagram 1: Force Field Benchmarking Workflow

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Resource | Type | Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| LAMMPS | Software | Molecular dynamics simulator | Studying asphalt mixture properties [3] |

| Gaussian 09 | Software | Quantum chemical package | Geometry optimization and charge derivation [3] |

| AMBER | Software Suite | Biomolecular simulation | Protein and nucleic acid simulations [1] |

| CHARMM | Software Package | Molecular dynamics | Biomolecular simulations with CHARMM force fields [3] |

| QCArchive | Database | Quantum chemical data | Source of reference geometries and energies [17] |

| SMIRNOFF | Format | Force field specification | SMIRKS-based Open Force Field parameters [17] |

Application-Specific Guidance

Based on the comprehensive benchmarking data:

For intrinsically disordered proteins: CHARMM36m2021 with mTIP3P water model currently provides the most balanced performance, though specific AMBER variants (a99sb4pew, a19sbopc) also perform well [8].

For general small molecule simulations: OPLS3e shows superior performance for reproducing QM geometries and energetics, with OpenFF 1.2 approaching similar accuracy [17].

For biaryl torsional potentials: CGenFF and OpenFF provide the most accurate results among traditional force fields, though neural network potentials (ANI series) significantly outperform all conventional methods [18].

For nucleic acids: The AMBER parmbsc0 correction addresses critical limitations in earlier versions and has been extensively validated across diverse NA structures [19].

Future Directions

The consistent benchmarking efforts across research groups have revealed persistent challenges in force field development. Recent trends include:

Incorporating polarizability: Fixed-charge force fields cannot account for environment-dependent polarization effects, prompting development of polarizable models [16].

Addressing charge anisotropy: Anisotropic charge distribution (σ-holes, lone pairs, aromatic systems) requires more sophisticated electrostatic models beyond atom-centered point charges [16].

Geometry-dependent charge fluxes: Some recent force fields like AMOEBA+(CF) now consider charge flux contributions along bonds and angles [16].

Machine learning potentials: Neural network potentials like ANI series show promising results for specific applications like torsional potentials [18].

In conclusion, while AMBER, CHARMM, and OPLS continue to evolve, the choice of force field remains system-dependent. Researchers should consult recent benchmarking studies specific to their biomolecular system of interest and consider the trade-offs between physical rigor, computational efficiency, and parameterization transferability when selecting a force field for their simulations.

In molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, the choice of water model is a critical determinant of the accuracy and reliability of the results, particularly in biological contexts involving proteins, lipids, and drugs. The water model must not only reproduce the physical properties of water but also be compatible with the force field used to describe the other biomolecules in the system. Despite the development of numerous sophisticated and polarizable water models, the simple, non-polarizable TIP3P model, developed nearly thirty years ago, remains the most widely used in biomolecular simulations today [20]. This prevalence is largely due to its computational efficiency and deep integration with popular non-polarizable force fields like AMBER, CHARMM, and OPLS. However, this widespread use persists even as research consistently demonstrates that the performance of protein-ligand complexes, membrane permeation, and material transport properties can vary significantly depending on the water model employed [10] [21]. This guide provides an objective comparison of water models, with a specific focus on the role of TIP3P and its alternatives, framing the analysis within the context of benchmarking the major AMBER, CHARMM, and OPLS force fields. It summarizes key experimental data and provides detailed methodologies to inform researchers and drug development professionals in selecting the most appropriate model for their specific applications.

Theoretical Foundation: Why Water Model and Force Field Compatibility Matters

The Polarizability Problem and MDEC Model

A fundamental challenge in biomolecular simulation is that simple, non-polarizable water models like TIP3P or SPC do not electronically respond to their environment. In reality, a water molecule is polarized differently in the gas phase, in the bulk liquid, and inside a protein, leading to different properties in each environment [20]. While polarizable water models exist to address this issue, they are inherently incompatible with the standard non-polarizable biomolecular force fields (AMBER, CHARMM, GROMOS, OPLS) because the latter incorporate the effects of electronic polarizability implicitly into their effective charges and parameters [20].

The MDEC (Molecular Dynamics in Electronic Continuum) framework explains how non-polarizable force fields can still be effective. In this theory, the explicit electronic polarizability is replaced by an implicit electronic continuum with a dielectric constant (εel, typically ~1.78 for water), which screens all electrostatic interactions [20]. The effective charges in force fields like AMBER and CHARMM are thus parameterized to include this screening, making them "effective" or "mean-field" polarizable models. This is why the dipole moment of TIP3P in simulations (~2.3 D) is different from the vacuum value (1.85 D) and also from estimates of the true liquid-state value (~3.0 D) [20]. A model's compatibility with a given force field hinges on whether its parameterization philosophy aligns with this MDEC concept.

Force Field-Specific Conventions

A key practical consideration is that major force fields are developed and tested with specific water models. Deviating from these standard pairings can lead to inconsistent results.

- CHARMM force fields are typically used with a modified version of the TIP3P water model [22] [23].

- AMBER force fields also traditionally pair with the TIP3P model [21].

- OPLS-AA force fields are often designed to work with the TIP4P water model [22]. Using TIP3P with OPLS can, in some cases, lead to different simulation outcomes, though the root cause may also be the inherent variability of MD simulations [22].

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship between the physical challenge, the theoretical solution, and the resulting practical conventions for force field and water model pairing.

Benchmarking Water Models: Performance Across Systems

Protein-Glycosaminoglycan (GAG) Complexes

A systematic 10 µs MD study investigated the effect of different explicit and implicit water models on the dynamics of protein-GAG complexes, which are crucial in extracellular matrix signaling [21]. The simulations used the AMBER FF14SB force field for proteins and GLYCAM06 for GAGs.

Table 1: Comparison of Water Model Performance in Protein-GAG Complexes (AMBER/GLYCAM06)

| Water Model | Type | Key Findings and Recommendations |

|---|---|---|

| TIP3P | Explicit (3-site) | Widely used benchmark; reliable for many systems but outperformed by more complex models. |

| SPC/E | Explicit (3-site) | Improved performance over TIP3P in some GAG studies [21]. |

| TIP4P | Explicit (4-site) | More appropriate for modeling chondroitin sulfate [21]. |

| TIP4PEw | Explicit (4-site) | More appropriate for modeling chondroitin sulfate [21]. |

| OPC | Explicit (4-site) | Among the best agreement with experiment for heparin structure and dynamics [21]. |

| TIP5P | Explicit (5-site) | Among the best agreement with experiment for heparin structure and dynamics [21]. |

| GB (IGB=1,2,5,7,8) | Implicit | Does not reproduce secondary structures well; use limited to resource-constrained scenarios [21]. |

Polyamide Membranes

The performance of different force fields and their associated water models is critical for simulating the transport properties of reverse-osmosis membranes. A benchmarking study evaluated several force fields for simulating polyamide membranes [10].

Table 2: Force Field and Water Model Performance for Polyamide Membranes

| Force Field | Typical Water Model | Key Findings (Dry/Hydrated State) |

|---|---|---|

| PCFF | PCFF-specific | Poor performance; overestimates Young's modulus and free volume. |

| CVFF | TIP3P/TIP4P | Accurate prediction of Young's modulus and fractional free volume. |

| SwissParam | TIP3P/TIP4P | Accurate prediction of Young's modulus and fractional free volume. |

| CGenFF (CHARMM) | TIP3P | Accurate prediction of Young's modulus and fractional free volume. |

| GAFF (AMBER) | TIP3P | Moderate performance; overestimates Young's modulus and free volume. |

| DREIDING | TIP3P/TIP4P | Poor performance; significant overestimation of mechanical properties and free volume. |

The study concluded that CVFF, SwissParam, and CGenFF (CHARMM) force fields, typically used with TIP3P or TIP4P water, delivered the most accurate predictions for membrane properties in both dry and hydrated states [10].

Hydration Free Energy (HFE) of Drug-like Molecules

The hydration free energy is a fundamental property for drug design. A large-scale study evaluated the performance of the CHARMM General Force Field (CGenFF) and the General AMBER Force Field (GAFF) in predicting the absolute HFE of over 600 molecules from the FreeSolv database [23]. The protocol used TIP3P water and is described in detail below.

Table 3: Force Field Performance for Hydration Free Energy (HFE) Calculation

| Force Field | Overall Performance | Functional Group-Specific Errors |

|---|---|---|

| CGenFF (CHARMM) | Generally accurate for HFE prediction. | Molecules with nitro-groups are over-solubilized. Molecules with amine-groups are under-solubilized. |

| GAFF (AMBER) | Generally accurate for HFE prediction. | Molecules with nitro-groups are under-solubilized. Molecules with carboxyl groups are over-solubilized. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Benchmarks

Protocol for Hydration Free Energy (HFE) Calculations

The methodology for calculating absolute hydration free energies, as implemented in the CHARMM program using TIP3P water, provides a robust benchmark [23].

Workflow Overview:

- System Setup: The solute molecule is placed in a cubic box of explicit TIP3P water molecules, with a minimum distance of 14 Å between the solute and the box edge. Periodic boundary conditions are applied.

- Alchemical Transformation: The solute is "annihilated" both in the aqueous phase and in vacuum using an alchemical pathway. This involves progressively turning off the solute's non-bonded interactions (electrostatics and Lennard-Jones) with its environment and within itself.

- Hamiltonian and Sampling: A hybrid Hamiltonian

H(λ) = λH₀ + (1-λ)H₁is used, where λ is a coupling parameter that varies from 0 (fully interacting solute) to 1 (fully annihilated solute). Molecular dynamics simulations are run at multiple intermediate λ values to ensure proper sampling. - Free Energy Analysis: The free energy change for the annihilation process is calculated separately for the solution (

ΔGsolvent) and vacuum (ΔGvac) simulations. The absolute hydration free energy is then obtained from the equation:ΔGhydr = ΔGvac - ΔGsolvent. The Multistate Bennett Acceptance Ratio (MBAR) method, implemented via tools like pyMBAR, is used for the final calculation.

Protocol for Benchmarking Water Models in Protein-GAG Complexes

The following general protocol is adapted from the 10 µs MD study comparing water models for protein-GAG complexes [21].

Workflow Overview:

- System Preparation: Obtain the 3D structure of the protein-GAG complex from the Protein Data Bank (PDB).

- Parameter Assignment: Use the FF14SB force field for the protein and the GLYCAM06 force field for the GAG molecule.

- Solvation: Solvate the complex in the center of a pre-equilibrated water box, ensuring a sufficient buffer distance (e.g., 10-12 Å). The tested water models include TIP3P, SPC/E, TIP4P, TIP4PEw, OPC, and TIP5P.

- Neutralization and Ion Addition: Add counterions to neutralize the system's net charge. Subsequently, add ions to match a physiologically relevant salt concentration (e.g., 150 mM NaCl).

- Equilibration: Perform energy minimization to remove steric clashes. This is followed by a series of short MD simulations where positional restraints on the solute are gradually released while the solvent and ions relax.

- Production MD: Run long-scale, unrestrained MD simulations (microsecond timescales are often necessary for convergence). Multiple independent replicates are recommended to assess variability.

- Analysis: Analyze the trajectories using descriptors such as binding pose stability, root-mean-square deviation (RMSD), hydrogen bonding patterns, and interaction energies. Compare the results with available experimental data, such as binding affinities or structural constraints.

Table 4: Key Software, Force Fields, and Water Models for MD Simulations

| Item | Function / Description |

|---|---|

| AMBER | A suite of biomolecular simulation programs. Includes the GAFF force field for small molecules. |

| CHARMM | A versatile program for classical MD simulations. Includes the CGenFF force field for drug-like molecules. |

| GROMACS | A high-performance MD simulation package. |

| OpenMM | A toolkit for high-performance MD simulation, often used as a GPU-accelerated backend. |

| FF14SB | The standard AMBER force field for proteins. |

| GAFF/GAFF2 | The General AMBER Force Field for organic molecules. |

| CGenFF | The CHARMM General Force Field for drug-like molecules. |

| OPLS-AA | The Optimized Potentials for Liquid Simulations - All Atom force field. |

| TIP3P | A standard 3-site water model; the default for AMBER and CHARMM. |

| TIP4P | A 4-site water model; often used with OPLS-AA. |

| TIP4PEw | A reparameterized 4-site model for better performance under Ewald summation. |

| OPC | A modern, highly accurate 4-site water model. |

| TIP5P | A 5-site water model that better represents the liquid water structure. |

| FreeSolv Database | A experimental and calculated database of hydration free energies, used for force field validation [23]. |

The benchmarking data presented in this guide leads to several key conclusions and practical recommendations for researchers:

- TIP3P's Enduring Role: TIP3P remains a robust and computationally efficient choice for standard biomolecular simulations, particularly when used with its native AMBER and CHARMM force fields. Its performance is reliable for many applications, justifying its widespread use.

- Context is Key: For specific systems, alternative water models can yield superior results. When simulating polyamide membranes, the CHARMM/CGenFF (with TIP3P) and CVFF force fields are recommended [10]. For protein-glycosaminoglycan complexes, more advanced models like OPC or TIP5P show the best agreement with experimental data [21].

- Force Field Compatibility is Critical: Adhering to standard force field/water model pairings (e.g., OPLS-AA with TIP4P) is crucial to avoid introducing artifacts. Mixing incompatible combinations can lead to inconsistent results [22].

- Functional Group Considerations: When calculating hydration free energies for drug-like molecules, researchers should be aware of systematic errors associated with specific functional groups, such as the under-solubilization of amines in CGenFF and over-solubilization of carboxyl groups in GAFF [23].

In summary, while TIP3P is a versatile and reliable workhorse, moving "beyond" TIP3P to more sophisticated water models can be essential for achieving high accuracy in targeted applications. The choice of model should be a deliberate decision based on the specific system under investigation, the required properties, and the associated force field.

Practical Implementation: Parameterization Tools and Simulation Protocols

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations serve as a foundational tool in computational chemistry and drug discovery, enabling the study of biological processes at an atomic level. The accuracy of these simulations is fundamentally dependent on the molecular mechanics force fields (FFs) that describe the potential energy of the system. For simulations involving drug-like small molecules, researchers commonly rely on generalized force fields such as the General AMBER Force Field (GAFF/GAFF2) and the CHARMM General Force Field (CGenFF). A critical step in employing these FFs is automated parameter assignment—the process by which atom types, partial charges, and bonded parameters are assigned to an arbitrary organic molecule. This guide provides a objective comparison of the primary tools and methodologies for this purpose, focusing on the AMBER-based AnteChamber suite and the CHARMM-based MATCH tool, contextualizing their performance within the broader landscape of AMBER, CHARMM, and OPLS force fields.

This section introduces the core force fields and their associated parameter assignment tools, outlining their underlying philosophies and typical workflows.

AMBER/GAFF and AnteChamber

General AMBER Force Field (GAFF/GAFF2): GAFF and its second generation, GAFF2, are designed to be compatible with the AMBER family of biomolecular force fields. They provide broad coverage for organic molecules typically encountered in drug discovery. The parameters were originally developed and optimized using the restrained electrostatic potential (RESP) charge model, derived from ab initio HF/6-31G* calculations [24] [25].

AnteChamber Tool Suite: AnteChamber is a cornerstone of the AmberTools package, designed to automate the parameterization of molecules for GAFF/GAFF2. It processes a molecule's structure and connectivity to assign atom types, bonds, angles, dihedrals, and atomic charges. A key feature is its support for multiple charge assignment methods, including the semi-empirical AM1-BCC model, which offers a faster alternative to RESP by approximating the charge distribution without costly ab initio calculations [24] [26] [25].

CHARMM/CGenFF and MATCH

CHARMM General Force Field (CGenFF): CGenFF is developed to be consistent with the CHARMM biomolecular force field. Its parametrization philosophy prioritizes quality and internal consistency, often relying on quantum mechanical (QM) calculations for model compounds to ensure accurate reproduction of geometries, vibrational spectra, and conformational energies [27].

MATCH Tool: MATCH is an atom-typing toolset that automates the assignment of parameters for various CHARMM force fields, including CGenFF. Its algorithm represents molecular structures as mathematical graphs and uses chemical pattern matching to assign atom types and parameters based on a library of known fragments. It employs bond charge increment (BCI) rules to build up molecular charge distributions from these fragments [28].

The OPLS Family

- While this guide focuses on GAFF and CGenFF, the OPLS family is a key comparator in force field performance studies. Tools like LigParGen are available for generating OPLS parameters. OPLS-AA and its successors, such as OPLS3e, are optimized for condensed-phase simulations of organic liquids and have been extensively validated for properties like solvation free energy [29] [25] [30]. Recent versions incorporate advanced charge assignment techniques, including off-atom charge sites for lone pairs and σ-holes [25].

The following diagram illustrates the typical automated parameter assignment workflow for a novel small molecule, highlighting the key decision points and outputs for the AMBER/GAFF and CHARMM/CGenFF ecosystems.

Performance Comparison and Experimental Data

The integrity and performance of automated parameter assignment have been rigorously tested in independent studies. Key benchmarks include the accuracy of assigned parameters relative to the official force field, and the performance in predicting physicochemical properties.

Integrity of Assigned Parameters

A critical study evaluating the automated assignment of CGenFF parameters revealed significant discrepancies when using the MATCH program compared to the official CGenFF program [24].

Table 1: Discrepancies in CGenFF Parameter Assignment via MATCH vs. Official CGenFF Program

| Parameter Aspect | Findings: MATCH vs. CGenFF Program | Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Atom Type Assignment | Over 80% of tested ligands contained atoms that were typed differently [24]. | Incorrect atom types lead to improper bonded and nonbonded parameters. |

| Bonded Parameters | All tested ligands had at least one differently assigned bonded parameter; MATCH does not assign Urey-Bradley terms for angles [24]. | Alters molecular geometry and vibrational characteristics. |

| Partial Atomic Charges | Over half of the atoms had different charges, with some differences exceeding 0.5 e and involving sign changes [24]. | Directly affects electrostatic interactions, crucial for binding and solvation. |

This demonstrates that MATCH does not perfectly replicate the official CGenFF parameter assignment, meaning that a simulation using "MATCH/CGenFF" may not be equivalent to one using "CGenFF program/CGenFF" [24].

For GAFF/GAFF2, the choice of charge model is a major variable. While the AM1-BCC model is popular for its speed, it does not exactly reproduce the performance of the RESP model, upon which GAFF was originally parameterized. The use of AM1-BCC has been associated with systemic errors greater than 1.0 kcal/mol in solvation free energies for certain functional groups [24]. A new charge model, ABCG2, was developed specifically for GAFF2 and has been shown to significantly improve accuracy, achieving a root-mean-square error (RMSE) of 0.99 kcal/mol for hydration free energies on the FreeSolv database, meeting the threshold for chemical accuracy [26].

Benchmarking in Solvation Free Energy Calculations

Solvation free energy is a fundamental property for evaluating force field performance. A comprehensive 2021 study compared nine condensed-phase force fields against a matrix of experimental cross-solvation free energies [29].

Table 2: Performance of Various Force Fields in Predicting Solvation Free Energies

| Force Field | Root-Mean-Square Error (RMSE) (kJ mol⁻¹) | Average Error (AVEE) (kJ mol⁻¹) | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| GROMOS-2016H66 | 2.9 | -0.8 | United-atom model; top performer in this study. |

| OPLS-AA | 2.9 | +0.2 | All-atom; optimized for organic liquids. |

| OPLS-LBCC | 3.3 | +0.5 | OPLS-AA with 1.14*CM1A-LBCC charges. |

| AMBER-GAFF2 | 3.4 | -1.5 | General AMBER force field, 2nd generation. |

| AMBER-GAFF | 3.6 | +0.2 | General AMBER force field, 1st generation. |

| OpenFF | 3.6 | -1.0 | SMIRKS-based open force field. |

| CHARMM-CGenFF | 4.0 | +0.2 | CHARMM general force field. |

| GROMOS-54A7 | 4.0 | -1.0 | United-atom model. |

| GROMOS-ATB | 4.8 | +1.0 | Automated parameterization. |

Note: 1 kJ/mol ≈ 0.239 kcal/mol. Data adapted from [29].

The chart below visualizes the RMSE of these force fields, showing that while performance varies, the differences, while statistically significant, are not overwhelmingly large, and all force fields have strengths and weaknesses across chemical space [29].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure reproducibility and provide a practical guide for researchers, this section outlines standard protocols for parameterization and validation.

Protocol for GAFF2 Parameterization with AnteChamber

The following workflow is standard for generating parameters for a novel small molecule using GAFF2 and the AnteChamber tools, leading to a topology file ready for simulation in AMBER or OpenMM [31] [32].

- Geometry Optimization: The 3D molecular structure is first optimized using quantum mechanics (QM) software (e.g., Gaussian09). A common protocol involves an initial optimization at the HF/3-21G level, followed by a more refined optimization at the HF/6-31G* level. For higher accuracy, a Möller-Plesset second-order perturbation theory (MP2) correction can be applied [32].