Alchemical Transformation Methods: A Comprehensive Guide to Free Energy Calculations in Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive overview of alchemical free energy (AFE) calculations, a powerful set of computational techniques for predicting binding affinities and solvation free energies critical to drug discovery...

Alchemical Transformation Methods: A Comprehensive Guide to Free Energy Calculations in Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of alchemical free energy (AFE) calculations, a powerful set of computational techniques for predicting binding affinities and solvation free energies critical to drug discovery and enzyme design. We cover the statistical mechanics foundations, key methodological approaches including free energy perturbation (FEP) and thermodynamic integration (TI), and advanced applications from small molecule optimization to protein-protein interactions. The guide also details best practices for troubleshooting and protocol optimization, validates methods against experimental data, and explores emerging trends such as quantum corrections and machine learning integration, offering researchers a solid framework for applying these methods in real-world projects.

The Principles and Evolution of Alchemical Free Energy Calculations

Alchemical free energy calculations are a cornerstone of computational chemistry, enabling the prediction of crucial biomolecular properties like protein-ligand binding affinities and solvation free energies. These methods rely on non-physical pathways, defined by a coupling parameter λ, to connect thermodynamic states of interest. This note details the core concepts, quantitative guidelines, and practical protocols for defining and employing these alchemical pathways in contemporary research, providing a framework for robust free energy calculations in drug development. [1] [2]

Core Principles and the Alchemical Coupling Parameter

The λ parameter is a central concept in alchemical free energy methods, serving as a dimensionless coordinate that smoothly interpolates the system's Hamiltonian between an initial state (A, λ=0) and a final state (B, λ=1). [1] [2] This approach allows for the calculation of free energy differences between states that may be chemically distinct, a task often computationally intractable through direct simulation.

Hybrid Hamiltonian: The system's potential energy function during an alchemical transformation is typically defined by a hybrid Hamiltonian. A common form is a linear interpolation:

U(λ) = (1 - λ) * U_A + λ * U_Bwhere

U_AandU_Bare the potential energies of the end-states. This formulation ensures that atλ=0, the system is governed entirely byU_A, and atλ=1, entirely byU_B. [2]Free Energy Calculation: The free energy change along

λis computed using methods like Thermodynamic Integration (TI) or Free Energy Perturbation (FEP). For TI, the derivative of the free energy with respect toλis calculated at multiple points and integrated:ΔG = ∫ ⟨∂U(λ)/∂λ⟩_λ dλwhere

⟨∂U(λ)/∂λ⟩_λis the ensemble average of the derivative at a specificλ. [1] [2]- Soft-Core Potentials: A critical consideration in alchemical transformations is the "end-point catastrophe," where atoms being annihilated can cause singularities in the energy calculation. To mitigate this, soft-core potentials are used to modify the van der Waals and sometimes electrostatic terms, preventing these divergences and ensuring a smooth transition. [1]

Quantitative Data and Practical Guidelines

Recent empirical studies provide concrete data to guide the setup and interpretation of alchemical calculations. The following table summarizes key quantitative findings from recent research.

Table 1: Empirical Guidelines for Alchemical Free Energy Calculations

| Aspect | Key Finding | Practical Implication | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Simulation Length | Sub-nanosecond simulations sufficient for accurate ΔG in most systems. | Shorter simulation times can be reliable, reducing computational cost. | [3] |

| Equilibration Time | Some protein systems (e.g., TYK2) required longer equilibration (~2 ns). | System-specific factors should be assessed; monitor equilibration. | [3] |

| Perturbation Size | Perturbations with |ΔΔG| > 2.0 kcal/mol exhibited higher errors. | Limit the scope of transformations between ligands for reliable results. | [3] |

| Advanced Workflows | Hybrid quantum-classical "book-ending" can incorporate quantum mechanical accuracy. | A pathway exists to correct classical force field inaccuracies for complex systems. | [4] |

These findings underscore that while general protocols exist, system-specific validation is crucial. The integration of advanced electronic structure methods via book-ending corrections highlights a growing trend to push beyond the limitations of classical force fields. [4]

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standard Protocol for Relative Binding Free Energy Calculation

This protocol outlines the steps for a typical Relative Binding Free Energy (RBFE) calculation using a thermodynamic cycle, a common application in lead optimization. [2]

- System Setup:

- Parameterization: Obtain force field parameters and partial charges for both the reference ligand (A) and the target ligand (B). GAFF and RESP charges are commonly used for small molecules. [4]

- Solvation: Place the protein-ligand complex and the free ligand in a solvent box (e.g., TIP3P, OPC water models) with counterions to neutralize the system. [4]

- Minimization & Equilibration: Perform energy minimization followed by gradual heating and equilibration under NVT and NPT conditions to relax the system. [4]

- λ-Window Stratification:

- Free Energy Analysis:

- Use the collected data to compute

ΔG_bind(A)andΔG_bind(B)via the double decoupling method, or more commonly, calculate the relative binding free energyΔΔG_binddirectly using a thermodynamic cycle with simulations of the transformation in the protein binding site and in solution. [2] - Employ estimators like MBAR or BAR to compute the free energy difference from the simulation data. [4] [1]

- Use the collected data to compute

Protocol for Quantum-Corrected Free Energies via Book-Ending

For systems requiring high electronic accuracy, a book-ending correction can be applied. [4]

- Classical AFE Calculation: Perform a standard alchemical free energy calculation as described above to obtain

ΔG_MM. - QM/MM End-State Corrections:

- For both end-states (e.g., ligand in water and ligand in protein), run simulations using a QM/MM Hamiltonian. A coupling parameter

λ'is used to morph the system's description from MM (λ'=0) to QM/MM (λ'=1). - Calculate the free energy difference for this transition,

ΔG_correction, using the MBAR estimator.

- For both end-states (e.g., ligand in water and ligand in protein), run simulations using a QM/MM Hamiltonian. A coupling parameter

- Result Combination: Apply the book-ending correction to the classical result:

ΔG_total = ΔG_MM + ΔG_correction. This final value incorporates the more accurate QM treatment. [4]

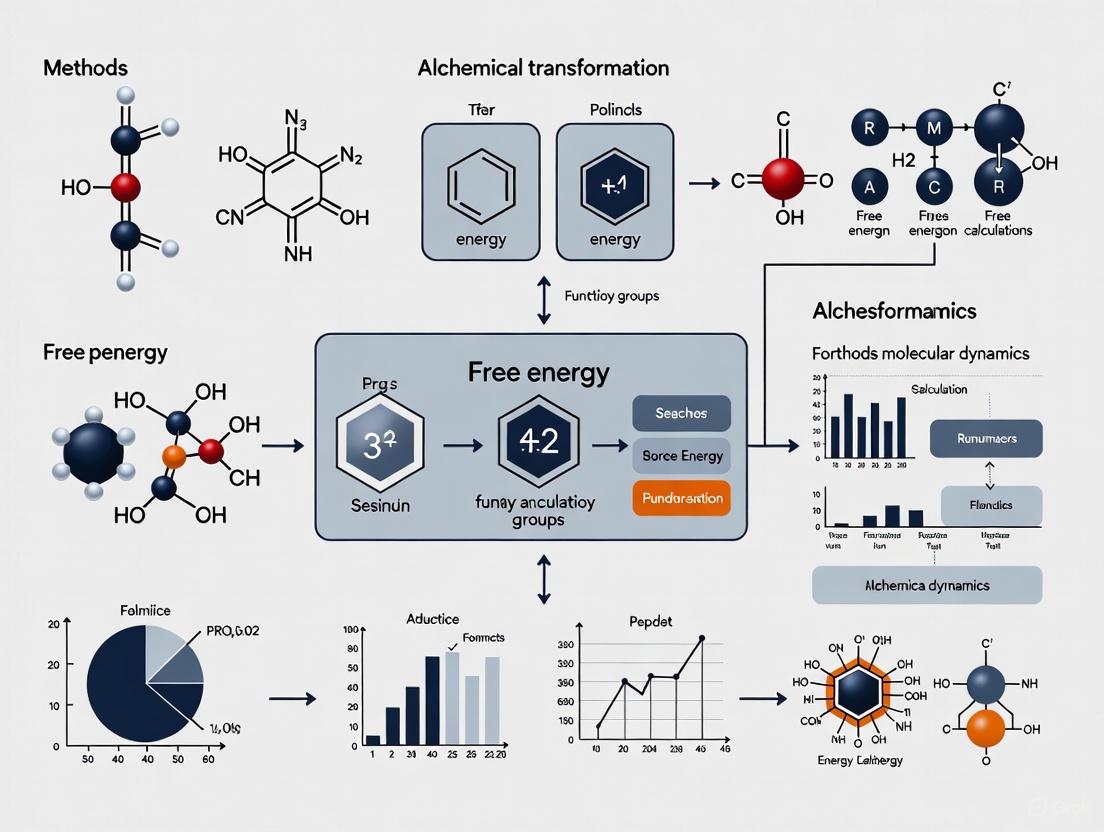

Visualizing Alchemical Pathways and Workflows

The following diagrams illustrate the logical flow of key alchemical free energy methods.

Thermodynamic Cycle for RBFE

Book-Ending Correction Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Software

Successful implementation of alchemical protocols relies on a suite of specialized software tools and theoretical components.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Alchemical Simulations

| Category | Item | Function / Description | Example Tools / Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| Simulation Engines | Molecular Dynamics Software | Performs the numerical integration of equations of motion and manages the alchemical transformation. | AMBER, GROMACS, OpenMM, NAMD |

| Analysis Libraries | Free Energy Estimators | Processes simulation trajectory data to compute free energy differences using statistical methods. | alchemlyb (for MBAR, TI), pymbar |

| Advanced Methods | Quantum-Correction Interface | Integrates higher-level quantum mechanical calculations to correct classical force field results. | In-house interface via PySCF/Qiskit [4] |

| Theoretical Components | Soft-Core Potential | Prevents numerical singularities by softening non-bonded interactions near λ=0 and λ=1. | Linear, Nonlinear (ilog) [1] |

| Sampling Enhancers | λ-Replica Exchange | Accelerates conformational sampling by allowing exchanges between simulations at adjacent λ values. | Hamiltonian Replica Exchange (HREX) [1] |

Alchemical free energy calculations have emerged as a cornerstone of computational chemistry, providing a powerful framework for predicting key biophysical properties such as protein-ligand binding affinities, solvation free energies, and partition coefficients [5]. The hallmark of these methods is the use of non-physical, or "alchemical," intermediate states that bridge the configuration space between two physical states of interest, enabling the efficient computation of free energy differences that would be prohibitively expensive to simulate directly [5]. The theoretical foundation for these calculations is firmly rooted in statistical mechanics, which provides the relationships connecting microscopic simulations to macroscopic thermodynamic observables.

These methods have seen a dramatic increase in application within drug discovery, where they are employed for virtual screening and lead optimization to predict binding affinities with experimental accuracy [6] [7]. Their utility stems from the fact that free energy is a state function; the calculated difference is independent of the pathway taken, which allows for the use of computationally tractable alchemical pathways [5]. This guide details the core statistical mechanics principles, from the foundational Zwanzig equation to contemporary analysis estimators, and provides protocols for their practical application in drug discovery.

Theoretical Foundations

The Zwanzig Equation and the Birth of Free Energy Perturbation

The theoretical basis for alchemical free energy calculations was firmly established with the work of Robert Zwanzig in 1954, who introduced the Free Energy Perturbation (FEP) formula [8]. The Zwanzig equation provides a direct method for calculating the free energy difference, ΔF, between an initial state A and a final state B from simulations of state A alone:

Here, k_B is Boltzmann's constant, T is the temperature, E_A and E_B are the potential energies of a configuration in states A and B, respectively, and the angular brackets ⟨ ⟩_A denote an ensemble average over configurations sampled from state A [8]. In essence, the equation weights the energy differences between the two states using the Boltzmann factor, providing a statistically rigorous estimate of the free energy change.

A critical limitation of the Zwanzig equation is that it requires substantial phase space overlap between states A and B for the exponential average to converge reliably. If the states are too dissimilar, the exponential term exp( - (E_B - E_A) / k_B T ) will be dominated by rare, high-energy configurations, leading to poor convergence and large statistical errors [5] [9]. To overcome this, the total transformation is typically divided into a series of smaller, more tractable "windows" along an alchemical coupling parameter, λ [8].

The Thermodynamic Cycle and Alchemical Transformations

Alchemical free energy calculations rarely simulate a physical process directly. Instead, they leverage thermodynamic cycles to compute the free energy difference of interest. This is particularly essential for calculating relative binding free energies, a central task in lead optimization [10].

Table: Thermodynamic Cycle for Relative Binding Free Energy

| Process | Free Energy |

|---|---|

| Ligand A (bound) → Ligand B (bound) | ΔGbind(A→B) |

| Ligand A (free) → Ligand B (free) | ΔGsolv(A→B) |

| Cycle Closure | ΔΔGbind = ΔGbind(A→B) - ΔGsolv(A→B) |

The alchemical transformation is performed in two environments: the protein binding site and the bulk solvent. The relative binding free energy, ΔΔG_bind, is obtained from the difference in the two transformation free energies, as dictated by the cycle [7]. This approach benefits from the cancellation of errors and is often more computationally efficient than calculating absolute binding affinities directly.

Evolution of Modern Estimators

While the Zwanzig equation provides a foundational FEP estimator, its reliance on forward sampling from a single state makes it statistically suboptimal. Subsequent methodological developments have focused on creating more efficient and less biased estimators that maximize the information extracted from simulations.

The Bennett Acceptance Ratio (BAR)

The Bennett Acceptance Ratio (BAR) represents a significant advancement over the Zwanzig equation by incorporating sampling data from both the initial (A) and final (B) states [5]. BAR seeks to find the optimal estimate of the free energy difference by minimizing the variance of the estimator, making it more efficient and less biased than FEP, especially for transformations with limited phase space overlap. The method effectively balances the information from both ensembles to produce a more reliable result.

Multistate Bennett Acceptance Ratio (MBAR)

The Multistate Bennett Acceptance Ratio (MBAR) is a generalization of BAR that can simultaneously analyze data from any number of intermediate states [5] [4]. This is particularly powerful for alchemical calculations, which typically use multiple λ windows. MBAR provides the statistically optimal way to compute the free energy difference between all states by leveraging data from all simulated ensembles, not just adjacent pairs. This makes it one of the most widely used analysis methods in modern free energy calculations [5].

Non-Equilibrium Methods and the Jarzynski Equality

An alternative to equilibrium methods like FEP and BAR is the use of non-equilibrium simulations, governed by the Jarzynski equality:

This relation connects the equilibrium free energy difference, ΔF, to the ensemble average of the non-equilibrium work, W, performed during fast switching processes between states [9]. While these simulations can be very fast, the exponential average can suffer from similar convergence issues as the Zwanzig equation if the work distributions are broad. However, advancements such as the Crooks Fluctuation Theorem and the development of maximum-likelihood methods have improved their robustness [9]. This approach forms the basis for high-throughput methods like Free Energy Nonequilibrium Switching (FE-NES) [11].

Table: Comparison of Key Free Energy Estimators

| Estimator | Core Principle | Data Used | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zwanzig (FEP) | Exponential averaging of energy differences | Single state (A) | Simple, foundational formula |

| BAR | Variance minimization | Both end states (A & B) | More efficient and less biased than FEP |

| MBAR | Global variance minimization | All intermediate states | Statistically optimal for multistate data |

| Jarzynski | Exponential averaging of work | Non-equilibrium trajectories | Enables very fast switching simulations |

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationships and evolution from the foundational theory to modern computational workflows.

Practical Protocols for Free Energy Calculations

Workflow for Relative Binding Free Energy (RBFE) Calculation

This protocol outlines the steps for predicting the relative binding free energy of two ligands using an alchemical transformation, a common task in structure-based drug design [3] [7].

System Setup

- Structures: Obtain protein and ligand structures from crystallography, modeling, or docking. Ensure ligands are correctly parameterized with tools like

antechamberand GAFF [4]. - Solvation: Embed the protein-ligand complex and the free ligand in separate solvent boxes (e.g., TIP3P, OPC water models) with counterions to neutralize the system [4].

- Alchemical Topology: Create a hybrid topology file that describes the atoms that are shared, unique to ligand A, and unique to ligand B, defining the alchemical transformation path.

- Structures: Obtain protein and ligand structures from crystallography, modeling, or docking. Ensure ligands are correctly parameterized with tools like

Simulation at Intermediate States (λ Windows)

- Define λ Pathway: Choose a set of λ values (e.g., 0.0, 0.1, 0.2, ..., 1.0) that connect ligand A (λ=0) to ligand B (λ=1). A typical simulation may use 12-24 windows [5].

- Equilibration: For each λ window, perform energy minimization and equilibrate the system under NVT and NPT conditions (e.g., 300 K, 1 atm) [4].

- Production Simulation: Run molecular dynamics simulations at each λ window to collect uncorrelated conformational samples. Simulation length depends on system size and complexity, but modern protocols can achieve convergence in sub-nanosecond simulations for some systems [3].

Analysis with Modern Estimators

- Energy Extraction: For each saved configuration from the simulations, compute the potential energy using the Hamiltonians for all λ windows of interest. This creates the overlap matrix required by MBAR.

- Free Energy Estimation: Use the MBAR method (e.g., via the

alchemlybpackage) to compute the free energy change for the transformation in both the protein and solvent environments [3]. - Cycle Closure: Calculate the relative binding free energy using the thermodynamic cycle:

ΔΔG_bind = ΔG_protein - ΔG_solvent. Report the uncertainty (standard error) from the estimator.

The workflow for this protocol is visualized below.

Key Considerations for Robust Calculations

- Sampling: Inadequate sampling of slow conformational degrees of freedom (e.g., sidechain rotamers, loop motions) is a major source of error. If a protein conformational change is required for one ligand but not the other, the assumption of error cancellation in relative calculations breaks down [10]. Extended simulation times or enhanced sampling techniques may be necessary.

- Perturbation Size: Large alchemical changes, particularly those with predicted

|ΔΔG| > 2.0 kcal/mol, have been shown to exhibit higher errors and should be treated with caution or broken into smaller steps [3]. - Force Field Accuracy: The accuracy of the final result is contingent on the quality of the force field used. Recent advances include incorporating quantum mechanical corrections via "book-ending" approaches to improve accuracy [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table: Essential Research Reagents and Software for Free Energy Calculations

| Tool / Reagent | Function | Example Packages / Types |

|---|---|---|

| Simulation Software | Engine for running molecular dynamics simulations. | AMBER [3] [4], GROMACS, OpenMM [12], CHARMM |

| Analysis Packages | Implements statistical estimators (MBAR, BAR) for free energy calculation. | alchemlyb [3], pymbar |

| Force Fields | Defines potential energy functions and parameters for molecules. | GAFF (small molecules) [4], AMBER/CHARMM force fields (proteins) |

| Free Energy Methods | Core algorithms for performing the alchemical transformation. | FEP, Thermodynamic Integration (TI) [3], Alchemical Transfer Method (ATM) [12] |

| System Preparation | Handles parameterization, solvation, and topology creation. | antechamber/LEaP (AMBER) [4], tleap, acpype |

Application in Drug Discovery: A Case Study

The practical impact of these methods is exemplified by a recent campaign to discover selective Wee1 kinase inhibitors [7]. In this study, researchers employed large-scale relative binding free energy (L-RB-FEP+) calculations to rapidly identify novel potent chemical scaffolds from billions of design ideas. The workflow involved:

- Ligand-Based RBFE: Alchemically transforming a reference compound to design ideas within the Wee1 binding pocket to predict on-target potency.

- Selectivity Modeling: Using protein residue mutation free energy calculations (PRM-FEP+) to alchemically mutate the Wee1 gatekeeper residue (Asn) to residues found in off-target kinases (e.g., Thr, Val). This estimated the cost of binding a given ligand to off-targets without simulating each one explicitly.

- Validation: The computational predictions successfully identified novel inhibitors with nanomolar affinity for Wee1 and significantly reduced off-target liabilities across the kinome, demonstrating the power of free energy calculations to optimize for both potency and selectivity in a real-world drug discovery project [7]. This case study underscores how the rigorous statistical mechanics foundations of alchemical methods translate into tangible industrial applications.

Alchemical free energy calculations (AFEC) represent a cornerstone of computational chemistry, enabling the prediction of crucial thermodynamic properties like binding affinities and solvation free energies. The journey of these methods from a theoretical concept in statistical mechanics to a practical tool in industrial drug discovery showcases a remarkable interplay of theoretical innovation and computational advancement. This article frames this evolution within the broader context of alchemical transformation methods research, highlighting key methodological breakthroughs and their impact on practical application. By tracing this path, we can appreciate how rigorous physical principles have been translated into reliable protocols for predicting molecular interactions.

Theoretical Foundations

The foundation of alchemical free energy calculations is deeply rooted in statistical mechanics. These methods compute the free energy difference associated with transferring a molecule from one environment to another, such as from solvent to a protein binding pocket, by utilizing non-physical, or "alchemical," intermediate states [5].

The standard Gibbs free energy of binding, ΔGbind, is related to the binding constant, Kb, by the fundamental equation:

ΔGbind = -kB T ln K_b

where k_B is the Boltzmann constant and T is the temperature [5]. Directly simulating binding events to compute this equilibrium constant is often computationally intractable for typical drug-target systems. Alchemical methods circumvent this problem by employing a thermodynamic cycle that connects the two physical end states of interest (e.g., ligand bound vs. unbound) through a series of alchemical states. These intermediate states are governed by hybrid potential energy functions that mix the properties of the end states, allowing for efficient sampling and free energy estimation without requiring direct simulation of the physical binding process [5].

Key milestones in the theoretical development of these estimators include:

- Free Energy Perturbation (FEP): Based on the Zwanzig relation, this is one of the earliest methods but can be statistically biased [5].

- Thermodynamic Integration (TI): A numerical quadrature approach with foundational theory dating back decades and computational applications emerging in the 1980s-90s [5].

- Bennett Acceptance Ratio (BAR): A more efficient and less biased estimator than early FEP implementations [5].

- Multistate BAR (MBAR): A generalization of BAR that enables optimal use of data from all simulated states [5].

Methodology and Protocols

General Workflow for Binding Free Energy Calculations

The application of alchemical free energy calculations follows a structured workflow, from system setup to data analysis. The diagram below outlines the key stages in a typical relative binding free energy study.

Detailed Experimental Protocol

The following protocol details the steps for a relative binding free energy calculation, as might be applied in a lead optimization project.

System Setup

- Initial Structure: Obtain a high-resolution structure of the protein (e.g., from X-ray crystallography or homology modeling). For the ACK1 case study, the kinase domain structure was retrieved from PDB code 4EWH [13] [14].

- Protein Preparation: Using a tool like MOE or Maestro, add missing hydrogen atoms, assign protonation states for ionizable residues (e.g., Asp, Glu, His) appropriate for the simulated pH, and repair any missing side chains or loops.

- Ligand Parametrization: Generate force field parameters for the ligand small molecules. This may involve:

- Assigning atomic partial charges (e.g., via RESP fitting).

- Defining bond, angle, and dihedral parameters, often derived from a general force field like GAFF.

- Solvation and Neutralization: Place the protein-ligand complex in a simulation box (e.g., TIP3P water). Add ions (e.g., Na⁺, Cl⁻) to neutralize the system's net charge and to achieve a physiologically relevant salt concentration.

Pose Selection and Preparation

- Docking: If a crystal structure is unavailable, perform molecular docking (e.g., with MOE) to generate plausible binding poses [13].

- Pose Validation: Critically assess the docked poses. The ACK1 study demonstrated that manual selection of poses informed by known X-ray structures of related complexes significantly improved accuracy. This can involve ensuring key ligand-protein interactions (e.g., hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic contacts) are preserved [13].

- Placement of Key Waters: Identify and manually place structurally important water molecules within the binding site. The ACK1 study found that manual placement of a bridging water molecule was critical, improving the correlation with experiment (R²) from 0.45 to 0.76 [13] [14].

Simulation Configuration

- Alchemical Pathway: Define the λ schedule that governs the transformation from one ligand to another. A typical schedule might use 10-20 intermediate λ windows, often with closer spacing near the end states (λ=0 and λ=1) where the energy changes can be more rapid.

- Simulation Parameters:

- Software: Use a package that supports alchemical calculations (e.g., GROMACS, AMBER, OpenMM, NAMD).

- Ensemble: Perform simulations in the NPT ensemble (constant Number of particles, Pressure, and Temperature).

- Temperature: Maintain a constant temperature (e.g., 300 K) using a thermostat (e.g., Nosé-Hoover).

- Pressure: Maintain a constant pressure (e.g., 1 bar) using a barostat (e.g., Parrinello-Rahman).

- Electrostatics: Treat long-range interactions with a method like Particle Mesh Ewald (PME).

- Sampling Time: The ACK1 study found that a tenfold increase in sampling time offered minimal improvement when the initial setup (pose, water placement) was suboptimal, highlighting the importance of setup over brute-force sampling [13].

Data Analysis

- Free Energy Estimation: Use a statistically robust estimator like BAR or MBAR to compute the free energy change from the simulation data collected across all λ windows.

- Error Analysis: Compute the uncertainty in the free energy estimate. This can be done using bootstrapping or analyzing the statistical inefficiency of the data. Hysteresis between forward and backward transformations can also serve as an internal check for insufficient sampling [13].

- Corrections: Apply any necessary corrections to compare with experiment, such as standard state corrections for binding free energies [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The table below catalogues the key computational "reagents" and tools essential for conducting alchemical free energy calculations.

Table 1: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Alchemical Free Energy Calculations

| Item | Function / Purpose | Example Tools / Formats |

|---|---|---|

| Protein Structure | Provides the 3D atomic coordinates of the biomolecular target. | PDB file format; structures from RCSB PDB [13] [14]. |

| Ligand Topology | Defines the chemical structure, atom types, bonds, and force field parameters for the small molecule. | MOL2, SDF files; parameterized with GAFF, CGenFF [13]. |

| Force Field | A set of empirical functions and parameters that describe the potential energy of the system. | AMBER, CHARMM, OPLS-AA [5]. |

| Solvation Model | Represents the aqueous environment surrounding the solute molecules. | Explicit water (TIP3P, TIP4P); Implicit solvent (GB, PB) [5]. |

| Software Package | The simulation engine that performs the molecular dynamics and alchemical transformations. | GROMACS, AMBER, OpenMM, NAMD, CHARMM [5] [13]. |

| Analysis Tools | Software and scripts used to process simulation trajectories and compute free energies. | MDAnalysis, PyEMMA, alchemical analysis tools (e.g., for MBAR) [5]. |

Results and Data

The transition of AFEC from a theoretical concept to a practical tool is evidenced by its performance in real-world applications. The following table summarizes quantitative results from a study on ACK1 inhibitors, demonstrating the impact of different setup protocols on predictive accuracy.

Table 2: Impact of Setup Protocol on Accuracy for ACK1 Inhibitors [13] [14]

| Setup Protocol | Key Modifications | R² (vs. Expt.) | Mean Unsigned Error (kcal mol⁻¹) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Automated Docking | Use of best-docked pose from automated procedure. | 0.45 ± 0.06 | 2.11 ± 0.08 |

| Knowledge-Guided | Manual pose selection informed by X-ray structures; manual placement of a bridging water molecule. | 0.76 ± 0.02 | 1.24 ± 0.04 |

| Increased Sampling | Tenfold increase in simulation time with automated docking poses. | Minimal Improvement | Minimal Improvement |

The data clearly shows that protocol refinement, specifically leveraging prior structural knowledge, dramatically improves accuracy. In contrast, simply increasing computational sampling without addressing fundamental setup issues provided negligible gains. This underscores that AFEC's reliability as a practical tool depends heavily on careful system preparation rather than computational brute force.

Applications

Alchemical methods are highly flexible and can be applied to a wide range of problems in molecular simulation. The diagram below illustrates several common application domains.

Within these domains, relative binding free energy calculations (Fig 1F) [5] have become a particularly impactful practical tool in drug discovery. This application involves the alchemical mutation of one ligand into another within a binding site, allowing for the prediction of how structural changes affect affinity. Its primary use is in lead optimization, where it helps prioritize which synthetic analogues to make and test, thereby reducing experimental costs and cycle times. The successful application to the ACK1 inhibitor dataset is a prime example of this use case [13] [14].

The journey of alchemical free energy calculations from a theoretical concept to a practical tool is a testament to decades of research in statistical mechanics and computational science. The development of robust estimators like BAR and MBAR, coupled with advances in molecular force fields and the availability of greater computational power, has been essential. However, as the ACK1 case study demonstrates, the transition to a reliable tool for industrial applications also hinges on the establishment of rigorous best practices. These include careful system preparation, knowledge-guided pose selection, attention to binding site hydration, and robust data analysis. As the field continues to evolve, these methods are poised to become even more integral to rational drug design and the study of biomolecular interactions.

In computational drug discovery, the affinity of a small molecule ligand for its biological target is quantified by the binding free energy (ΔGb

Theoretical Foundations & Quantitative Comparison

The theoretical basis for free energy calculations was established decades ago, with foundational work by Kirkwood (1935) and Zwanzig (1954) laying the groundwork for methods like free energy perturbation (FEP) and thermodynamic integration (TI) [2]. In modern drug discovery, these calculations primarily rely on all-atom Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations and fall into two categories: (i) alchemical transformations and (ii) path-based or geometrical methods [2].

Alchemical transformations sample a non-physical pathway between two states using a coupling parameter (λ) that interpolates between the system's Hamiltonians [2]. In contrast, path-based methods define the pathway using collective variables (CVs) that are often geometrical in nature (e.g., distances, angles), resulting in a potential of mean force (PMF) along the selected CVs [2].

The following table summarizes the key characteristics of Relative and Absolute Binding Free Energy calculations, which are the primary applications of these principles in drug discovery.

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Relative vs. Absolute Binding Free Energy Calculations

| Feature | Relative Binding Free Energy (RBFE) | Absolute Binding Free Energy (ABFE) |

|---|---|---|

| Objective | Computes the difference in binding free energy (ΔΔGb) between two similar ligands, A and B, for the same receptor [10] [15]. | Computes the absolute binding free energy (ΔGb) for a single ligand binding to a receptor [10] [15]. |

| Typical Application | Lead optimization during drug discovery; ranking analogous compounds with similar chemical structures [2] [10]. | Determining the fundamental affinity of a single ligand, useful in early-stage discovery and scaffold evaluation [16] [10]. |

| Thermodynamic Cycle | Relies on a cycle that transforms ligand A to B both in the solvent and in the protein-bound state [2]. | Employs the "double decoupling" method, alchemically turning the ligand from an interacting to a non-interacting entity in both the bound and unbound states [2]. |

| Computational Efficiency | Generally more efficient, especially for similar ligands, as it can benefit from error cancellation between the two legs of the cycle [10] [15]. | Typically more computationally expensive and can require more simulation time to achieve convergence [16] [15]. |

| Accuracy & Challenges | Can be highly precise for congeneric series but may fail if ligands induce different protein conformations or binding modes [10]. Achieving errors < 1 kcal/mol is challenging [2]. | Avoids the assumption of error cancellation, making interpretation of failures more straightforward. However, accurate prediction (< 1 kcal/mol error) remains a major challenge [2] [10]. |

| Mechanistic Insight | Provides no direct information on the binding pathway or mechanism [2]. | Path-based ABFE methods can provide insights into binding pathways and the free energy profile [2]. |

Methodologies and Protocols

Protocol for Relative Binding Free Energy (RBFE) Calculation

Relative binding free energy calculations are the predominant method used by pharmaceutical companies for lead optimization [2]. The following protocol outlines the key steps for performing an RBFE calculation using alchemical transformation.

1. System Setup:

- Structure Preparation: Obtain high-quality structures of the protein receptor and the ligands (A and B). Protonation states and tautomers should be assigned correctly, considering the physiological pH [15].

- Solvation and Ionization: Solvate the system in a periodic box of water molecules and add ions to neutralize the system's total charge and achieve a physiological salt concentration [16].

2. Alchemical Transformation Setup:

- Define the λ Schedule: Create a series of non-physical intermediate states (windows) bridging the transformation from ligand A to ligand B. The coupling parameter λ typically ranges from 0 (ligand A) to 1 (ligand B). A sufficient number of windows (often 12-24) is crucial for smooth transformation and convergence [16] [10].

- Ligand Topology Mapping: A critical step is to map the atoms of ligand A to those of ligand B to define which atoms are transformed, which are annihilated, and which are created. This requires expert intervention or robust automated algorithms to handle non-obvious mappings [10].

3. Simulation and Sampling:

- Equilibration: For each λ window, energy-minimize and equilibrate the system under the appropriate ensemble (e.g., NPT).

- Production Runs: Perform molecular dynamics (MD) simulations at each λ window to sample configurations. The simulation length must be sufficient to sample relevant conformational changes, which can be slow for flexible ligands or proteins [16] [10]. GPU-accelerated computing is often essential.

4. Free Energy Analysis:

- Estimate ΔΔGb: Use methods like Free Energy Perturbation (FEP) or Thermodynamic Integration (TI) to compute the free energy change for transforming A→B in the bound state (ΔGbound) and in solution (ΔGsolvent). The relative binding free energy is then calculated via the thermodynamic cycle: ΔΔGb = ΔGbound - ΔGsolvent [2] [15].

Diagram 1: Thermodynamic cycle for RBFE

Protocol for Absolute Binding Free Energy (ABFE) Calculation

Absolute binding free energy calculations are computationally more demanding but provide the fundamental affinity without requiring a reference ligand. The double decoupling method is a standard alchemical approach [2].

1. System Setup:

- Bound State System: Prepare the protein-ligand complex, solvate it, and add ions as described in the RBFE protocol.

- Unbound State System: Prepare a separate system containing a single ligand molecule solvated in a box of water.

2. Alchemical Decoupling:

- Define the λ Schedule: Create a λ pathway from 1 (fully interacting ligand) to 0 (fully non-interacting or "decoupled" ligand). This process involves gradually turning off the electrostatic and van der Waals interactions between the ligand and its environment.

- Apply Restraints: To improve sampling and prevent the ligand from drifting in the binding site when its interactions are nearly turned off, apply artificial restraints. These restraints are later accounted for in the final free energy calculation [15].

3. Simulation and Sampling:

- Stratified Sampling: Run separate equilibrium MD simulations at each λ window for both the bound and unbound (solvent) legs of the transformation. The need for extensive sampling is particularly acute for charged and flexible ligands [16].

- Nonequilibrium Methods: Alternatively, use nonequilibrium MD simulations, where a single trajectory is rapidly driven from one state to another, and the work is recorded. This can be more efficient and easily parallelized [2].

4. Free Energy Analysis:

- Calculate Decoupling Work: Use TI or FEP to compute the work of decoupling the ligand from the protein (ΔGdecouple,bound) and from the solvent (ΔGdecouple,solvent).

- Compute Absolute ΔGb: The absolute binding free energy is given by: ΔGb = ΔGdecouple,bound - ΔGdecouple,solvent + ΔGrestraints - RTln(Vsite/V0

Diagram 2: Double decoupling method for ABFE

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Successful execution of free energy calculations relies on a suite of software and computational resources. The table below lists key components of the modern computational scientist's toolkit.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Free Energy Calculations

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Dynamics Engines (e.g., GROMACS, AMBER, NAMD, OpenMM) | Software | Performs the numerical integration of Newton's equations of motion to simulate the system's dynamics and generate conformational samples [2] [16]. |

| Force Fields (e.g., CHARMM, AMBER, OPLS-AA) | Parameter Set | Provides the functional forms and parameters (atomic charges, bond lengths, angles) that define the potential energy of the system [16]. Fixed-charge force fields are most common, but polarizable models are emerging. |

| Free Energy Analysis Tools (e.g., alchemical analysis packages) | Software / Library | Implements algorithms like FEP, TI, and Bennett Acceptance Ratio (BAR) to estimate free energy differences from the simulation data [2] [15]. |

| System Setup Tools (e.g., CHARMM-GUI, tleap, protein preparation wizards) | Software | Automates and standardizes the process of building simulation systems, including solvation, ionization, and assignment of force field parameters [16]. |

| Graphical Processing Units (GPUs) | Hardware | Specialized hardware that dramatically accelerates MD simulations, making the large number of required simulations computationally feasible [2] [15]. |

| Path Collective Variables (PCVs) | Methodological Concept | Sophisticated collective variables used in path-based methods to define a reaction coordinate for binding/unbinding, allowing for calculation of the Potential of Mean Force (PMF) [2]. |

Advanced Considerations and Future Directions

While alchemical methods are well-established, path-based methods are gaining prominence for their ability to provide both absolute binding free energies and mechanistic insights into the binding process, such as binding pathways and intermediates [2]. These methods often employ Path Collective Variables (PCVs) to describe the system's progression along a predefined pathway from the unbound to the bound state [2]. A recent innovation combines path-based variables with bidirectional nonequilibrium simulations, creating a protocol that is straightforward to parallelize and significantly reduces the time-to-solution for binding free energy calculations [2].

A critical consideration for all methods, especially when dealing with charged ligands like nucleotides (ATP, GTP), is the treatment of ions. Fixed-charge force fields may fail to accurately capture interactions with divalent ions like Mg2+, potentially leading to inaccuracies [16]. Furthermore, the highly charged and flexible nature of these ligands necessitates extensive conformational sampling to account for slow relaxation times [16]. As the field progresses, the integration of machine learning with enhanced sampling techniques and the development of more accurate polarizable force fields are poised to further improve the reliability and scope of free energy calculations in drug discovery [2].

Alchemical free energy calculations are a powerful class of computational methods for predicting free energy differences by using non-physical, or "alchemical," pathways. These methods are indispensable in computational chemistry and drug discovery for estimating properties like binding affinities and solvation free energies with a level of detail and potential accuracy that simpler scoring functions cannot provide [5] [17]. This application note details the suitable problem domains for these methods and outlines the essential protocols and system requirements for their successful implementation.

Suitable Problems for Alchemical Methods

Alchemical methods are particularly well-suited for problems where directly simulating a physical process is computationally prohibitive due to high energy barriers or long timescales. Their application is most effective in the following domains:

- Biomolecular Binding: This is the most prominent application, crucial for drug discovery.

- Relative Binding Free Energy (RBFE) Calculations: Used to estimate the difference in binding affinity between two or more related ligands to the same receptor [17] [2]. This is extensively applied in lead optimization to rank-order compounds and guide synthetic efforts [2].

- Absolute Binding Free Energy (ABFE) Calculations: Used to compute the binding affinity of a single ligand to a receptor, typically by alchemically decoupling the ligand from its environment in both the bound and unbound states [5] [2].

- Solvation and Partitioning:

- Hydration Free Energy (HFE) Calculations: Predicting the free energy change when a molecule is transferred from the gas phase into water [4]. This is a key benchmark for force field validation.

- Partition (log P) and Distribution (log D) Coefficients: Determining how a molecule distributes itself between two immiscible phases, such as octanol and water, which is critical for understanding pharmacokinetics [5].

- Protein Engineering:

The table below summarizes these key application areas and their primary contexts of use.

Table 1: Suitable Problem Domains for Alchemical Free Energy Calculations

| Application Domain | Type of Free Energy Calculation | Primary Use Context |

|---|---|---|

| Biomolecular Binding | Relative Binding Free Energy (RBFE) | Lead optimization, SAR analysis, selectivity profiling [17] [2] |

| Absolute Binding Free Energy (ABFE) | Hit identification, affinity prediction for novel scaffolds [5] [2] | |

| Solvation & Partitioning | Hydration Free Energy (HFE) | Force field validation, solubility prediction [5] [4] |

| Partition Coefficients (log P) | ADME-Tox prediction [5] [17] | |

| Protein Engineering | Protein Mutation (Stability/Binding) | Understanding protein function, designing stable enzymes [5] |

System Requirements and Prerequisites

Successful application of alchemical methods depends on several foundational requirements that must be addressed before initiating calculations.

System Setup and Force Field Considerations

- Molecular Topology and Parameters: Accurate parameters for all system components (protein, ligand, solvent, ions) are essential. Ligand parameters are often derived using tools like GAFF and RESP charge fitting [4].

- Force Field Selection: The choice of force field (e.g., AMBER, CHARMM) is critical, as inaccuracies will propagate into the free energy estimate [5] [17]. The force field must be appropriate for the system under study.

- Solvation and Environment: The system must be solvated in an appropriate water model (e.g., TIP3P, OPC) within a simulation box with periodic boundary conditions [4]. Proper ion concentration should be used to neutralize the system and mimic physiological conditions.

- Initial Structure Preparation: This includes obtaining a reliable 3D structure of the protein and generating a plausible binding pose for the ligand, which may require docking studies if not available from experimental structures [5].

- Theoretical Knowledge: Practitioners require a solid understanding of statistical mechanics, molecular dynamics, and the biophysics of binding [5].

- Software Proficiency: Experience with molecular dynamics packages (e.g., AMBER, GROMACS, OpenMM, CHARMM) that implement alchemical methods is necessary [5] [4].

- Hardware: Alchemical calculations are computationally intensive. Access to high-performance computing (HPC) resources, particularly GPUs, is essential for achieving convergence in a practical timeframe [5] [2].

Methodological Approaches and Protocols

The core of alchemical methods involves defining a hybrid Hamiltonian that interpolates between the initial (state A) and final (state B) states using a coupling parameter, λ.

Core Alchemical Pathways and Potentials

The hybrid potential energy function is defined as ( U(\vec{q}; \lambda) ), which smoothly transitions from state A (( \lambda = 0 )) to state B (( \lambda = 1 )) [1]. Key technical components include:

- Soft-Core Potentials: These are vital to avoid singularities when atoms are created or annihilated. A standard soft-core form for the Lennard-Jones potential is: ( U{LJ}(r{ij};\lambda) = 4\,\epsilon{ij}\,\lambda\,\left( \frac{1}{[\alpha(1-\lambda) + (r{ij}/\sigma{ij})^6]^2} - \frac{1}{\alpha(1-\lambda) + (r{ij}/\sigma_{ij})^6} \right) ) where ( \alpha ) is a soft-core parameter [1].

- Concerted Coupling: Modern approaches, such as the Linear Basis Function (LBF) protocol, allow for the simultaneous coupling of multiple energy terms (e.g., electrostatics and van der Waals) rather than sequential decoupling, improving efficiency and flexibility [1].

Key Estimation Techniques

- Thermodynamic Integration (TI): The free energy is computed by integrating the average derivative of the Hamiltonian with respect to λ across a series of discrete λ windows [1] [2]. ( \Delta G = \int0^1 \left\langle \frac{\partial U(\lambda)}{\partial \lambda} \right\rangle\lambda d\lambda )

- Free Energy Perturbation (FEP): The free energy difference is calculated using the Zwanzig equation, which exponentially averages the energy difference between two states [1] [2]. ( \Delta A = -kBT \cdot \ln \langle \exp[-(U1 - U0)/kB T] \rangle_0 )

- Multistate Bennett Acceptance Ratio (MBAR): A statistically optimal method that generalizes the Bennett Acceptance Ratio (BAR) to multiple states, making use of all the data collected at all λ states to produce a maximum-likelihood estimate of the free energies [5] [4].

The following workflow diagram outlines the standard protocol for a relative binding free energy calculation, which employs a thermodynamic cycle to improve precision.

Enhanced Sampling and Advanced Protocols

To overcome sampling challenges, several enhanced sampling techniques are routinely employed:

- Hamiltonian Replica Exchange (HREX): Also known as λ-REMD, this method exchanges configurations between simulations at different λ values. This helps overcome barriers in both conformational and alchemical space, significantly improving convergence [1].

- Nonequilibrium Methods: These protocols involve fast, out-of-equilibrium switching between states and use estimators like the Jarzynski equality to recover equilibrium free energies [2].

- Quantum-Centric Corrections: For higher accuracy, book-ending corrections can be applied. This involves computing the free energy difference between a molecular mechanics (MM) and a quantum mechanics (QM) description for the end-states, which is then used to correct the classically computed free energy [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit

This section lists essential software, tools, and reagents required to perform alchemical free energy calculations.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Category | Item / Software | Function / Description |

|---|---|---|

| Software Packages | AMBER, GROMACS, CHARMM, OpenMM | Molecular dynamics engines that implement alchemical methods (FEP, TI) and enhanced sampling [5] [4]. |

| Analysis Tools | alchemical-analysis, pymbar, MBAR | Python libraries for analyzing simulation data and computing free energies using MBAR and other estimators [5]. |

| Parameterization | ANTECHAMBER, GAFF, RESP | Tools for generating force field parameters and partial charges for small molecule ligands [4]. |

| System Preparation | LEaP, PACKMOL, pdbfixer | Utilities for building simulation systems, adding solvent, ions, and fixing structures [4]. |

| Enhanced Sampling | PLUMED | A library for implementing various enhanced sampling methods, including metadynamics and replica exchange [2]. |

| System Components | Protein & Ligand Structures | Initial 3D coordinates (e.g., from PDB or docking). |

| Water Model (e.g., TIP3P, OPC) | Explicit solvent for solvating the system [4]. | |

| Ions (e.g., Na+, Cl-) | To neutralize system charge and mimic ionic strength. |

Alchemical free energy methods provide a rigorous, physics-based framework for tackling critical problems in drug discovery and molecular design. Their application is most suitable for calculating relative binding affinities in lead optimization, absolute binding affinities for novel scaffolds, and solvation properties. Success hinges on careful system preparation, appropriate choice of alchemical pathway and enhanced sampling protocols, and rigorous analysis. As the field progresses with integrations of machine learning and quantum mechanical methods, the scope, accuracy, and robustness of these calculations are expected to expand further, solidifying their role as an essential tool for computational scientists.

Methodologies and Real-World Applications in Biomedical Research

Alchemical free energy calculations have become a cornerstone of modern computational drug discovery, providing a rigorous, physics-based approach for predicting binding affinities. These methods are particularly valuable during the lead optimization phase in structure-based drug design, where they are employed to prioritize compounds for synthesis by computationally estimating how chemical modifications affect binding to a biological target [18] [10]. Among these techniques, Free Energy Perturbation (FEP), Thermodynamic Integration (TI), and the Bennett Acceptance Ratio (BAR) and its multistate generalization (MBAR) represent fundamental equilibrium approaches for calculating free energy differences. These methods share a common theoretical foundation in statistical mechanics but differ in their practical implementation and estimators used to compute free energy changes [18]. As state functions, free energy differences are independent of the path taken between thermodynamic states, allowing these methods to utilize non-physical, "alchemical" pathways to connect chemically distinct end states through a series of intermediate λ-states [18] [2]. This review provides a detailed examination of these core equilibrium methods, their protocols, applications, and performance in drug discovery contexts.

Theoretical Foundations and Method Comparisons

Fundamental Principles

Alchemical free energy methods compute the free energy difference between two thermodynamic states by traversing an artificial pathway parameterized by a coupling parameter λ. This parameter smoothly interpolates the system Hamiltonian from an initial state (λ = 0) to a final state (λ = 1) [18] [2]. For binding free energy calculations, this typically involves transforming one ligand into another, both in the binding site and in solution, with the relative binding free energy determined through a thermodynamic cycle [19]. The effectiveness of these methods relies on sufficient phase space overlap between consecutive λ states, achieved by stratifying the transformation into multiple intermediate windows [18].

Comparative Analysis of Methods

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Equilibrium Free Energy Methods

| Method | Theoretical Foundation | Primary Estimator | Computational Requirements | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thermodynamic Integration (TI) | Numerical integration of ∂U/∂λ | ∫⟨∂U/∂λ⟩dλ | Moderate to high (10-20 λ windows) | Relative binding free energies, solvation free energies [18] [3] |

| Free Energy Perturbation (FEP) | Exponential averaging of energy differences | -β⁻¹ln⟨exp(-βΔU)⟩ | Moderate to high (10-20 λ windows) | Relative binding free energies, solvation free energies [18] [2] |

| Bennett Acceptance Ratio (BAR) | Optimized estimator using forward and reverse work | Specific ratio of Fermi functions | Moderate (requires sampling at two end states) | Improved accuracy for FEP calculations, relative free energies [18] [20] |

| Multistate BAR (MBAR) | Generalized BAR for multiple states | Maximum likelihood estimator | High (leverages all states simultaneously) | Network of transformations, complex molecular systems [18] [19] |

The choice between TI, FEP, and BAR/MBAR involves important trade-offs. TI numerically integrates the average derivative of the potential energy with respect to λ, providing a theoretically straightforward approach [18]. FEP instead relies on exponential averaging of energy differences between states [18] [2]. BAR represents an optimized estimator that utilizes data from both forward and reverse directions between states, while MBAR extends this concept to multiple states simultaneously, potentially improving statistical efficiency [18] [19]. In practice, all these approaches require stratification into multiple λ windows to ensure adequate phase space overlap, with typical simulations utilizing 10-20 discrete λ states [19].

Detailed Methodological Protocols

Thermodynamic Integration (TI) Protocol

System Preparation:

- Initial Structure Acquisition: Obtain protein-ligand complex structures from crystallography, NMR, or homology modeling. For relative free energy calculations, ensure ligands are properly aligned in the binding site [3].

- Parameter Assignment: Assign molecular mechanics force field parameters (e.g., AMBER, CHARMM) to all atoms. For small molecules, use tools like antechamber or CGenFF with careful attention to partial charge derivation [3].

- Solvation and Ionization: Solvate the system in explicit water (e.g., TIP3P model) with periodic boundary conditions. Add ions to neutralize system charge and achieve physiological salt concentration (e.g., 150 mM NaCl) [20].

Simulation Setup:

- λ-State Definition: Define a series of λ values between 0 and 1. For soft-core potentials, use 10-20 windows with closer spacing near end points where nonlinearities often occur [18] [3].

- Potential Energy Function: Implement a hybrid Hamiltonian using a linear coupling scheme: V(q;λ) = (1-λ)VA(q) + λVB(q), where VA and VB represent the potential energies of the initial and final states, respectively [2].

Simulation Execution:

- Equilibration: For each λ window, perform energy minimization followed by gradual heating to the target temperature (typically 300 K) over 100 ps. Conduct equilibration in the NPT ensemble (constant particle number, pressure, and temperature) for 1-2 ns to stabilize system density [3].

- Production Sampling: Run production simulations for each λ window using an appropriate timestep (typically 2 fs with bonds to hydrogen constrained). Recent studies suggest sub-nanosecond simulations per window may be sufficient for some systems, though 2-5 ns provides better convergence for challenging transformations [3].

- Data Collection: Calculate and record ⟨∂V/∂λ⟩_λ at regular intervals (e.g., every 100 steps) for each λ window [18].

Analysis:

- Numerical Integration: Compute the free energy difference using the TI formula:

ΔA = ∫⟨∂V/∂λ⟩_λ dλ

where the integral is evaluated numerically using quadrature methods such as the trapezoidal rule or Gaussian quadrature [18].

- Error Analysis: Estimate uncertainties using block averaging or bootstrapping methods to account for temporal correlations in the data [3].

Free Energy Perturbation (FEP) Protocol

System Preparation and Setup: Follow the same system preparation and λ-state definition steps as the TI protocol [18] [2].

Simulation Execution:

- Sampling: Conduct independent simulations at each λ window as described in the TI protocol.

- Energy Difference Calculation: For each pair of adjacent λ states (λ and λ+Δλ), compute the potential energy difference ΔU = U(λ+Δλ) - U(λ) at regular intervals during the simulation [18].

Analysis:

- Free Energy Calculation: Compute the free energy difference between adjacent states using the FEP formula:

ΔA{λ→λ+Δλ} = -β⁻¹ ln⟨exp(-βΔU{λ,λ+Δλ})⟩_λ

where β = (kBT)⁻¹, kB is Boltzmann's constant, and T is temperature [18].

- Bidirectional Estimation: For improved accuracy, use the BAR estimator instead of unidirectional exponential averaging:

ΔA = -β⁻¹ ln[⟨f(U + C)⟩/⟨f(-U - C)⟩] + C

where f(x) = 1/(1 + e^{βx}) is the Fermi function and C is a constant determined self-consistently [18] [20].

- Cumulative Free Energy: Sum all intermediate free energy differences to obtain the total free energy change:

ΔA{total} = Σ ΔA{λk→λ{k+1}} [18].

MBAR Protocol for Multistate Analysis

System Preparation and Setup: Follow the same system preparation and multi-λ-state definition as previous protocols [19].

Simulation Execution:

- Sampling: Conduct simulations at all λ states, including end states and intermediates.

- Energy Matrix Calculation: Compute the reduced potential energy uk(xi) for every configuration i sampled at every state k, forming a complete energy matrix [19].

Analysis:

- Free Energy Estimation: Solve the MBAR equations to obtain the free energies of all states:

ΔAk = -β⁻¹ ln Σ{i=1}^N exp[-βuk(xi)] / Σ{j=1}^K Nj exp[-βuj(xi) - ΔA_j]

where K is the total number of states and N_j is the number of samples from state j [19].

- Statistical Efficiency: Leverage the optimal weighting of MBAR to maximize statistical precision, particularly beneficial when combining data from multiple states with uneven sampling [19].

Diagram 1: Workflow for FEP, TI, and MBAR Simulations. The protocol shows common preparation stages with method-specific analysis paths.

Performance Benchmarks and Applications

Accuracy and Reliability Assessment

Table 2: Performance Benchmarks of Free Energy Methods Across Various Systems

| Method | Typical RMS Error vs Experiment | Optimal Perturbation Size | Simulation Time Requirements | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TI | ~1.0 kcal/mol or less [3] [19] | ~2-5 ns/λ window for convergence [3] | High computational cost for large perturbation networks [19] | |

| FEP | ~1.0 kcal/mol or less [19] [7] | <2.0 kcal/mol for optimal reliability [3] | ~2-5 ns/λ window for convergence [19] | Statistical inefficiency for large perturbations [18] |

| BAR | R²=0.79 for GPCR agonists [20] | Suitable for diverse chemotypes | Varies by system complexity | Requires careful implementation for membrane proteins [20] |

| MBAR | ~1.0 kcal/mol or less [19] | Efficient for network of compounds | Single simulation for multiple RBFEs | Complex implementation; requires all state energies [19] |

Recent studies have established practical guidelines for optimizing free energy calculations. For TI simulations, perturbations with |ΔΔG| > 2.0 kcal/mol exhibit increased errors, suggesting such large transformations should be broken into smaller steps [3]. Sub-nanosecond simulations per λ window have proven sufficient for accurate prediction in many systems, though more challenging transformations (e.g., those involving protein conformational changes) may require longer equilibration times (~2 ns) [3]. For GPCR targets, BAR-based binding free energy calculations have demonstrated significant correlation with experimental pK_D values (R² = 0.7893), validating the approach for pharmaceutically relevant membrane protein targets [20].

Advanced Implementations and Efficiency Gains

Recent methodological advances have substantially improved the efficiency of alchemical free energy calculations. λ-dynamics with bias-updated Gibbs sampling (LaDyBUGS) enables continuous sampling between multiple ligand analogs within a single simulation, achieving 18-66-fold efficiency gains for small perturbations and 100-200-fold improvements for challenging aromatic ring substitutions compared to traditional TI [19]. This approach eliminates the need for separate bias determination simulations and allows multiple relative binding free energies to be determined from a single simulation without compromising accuracy [19].

In lead optimization campaigns, these methods have demonstrated significant practical impact. Free energy calculations can improve the odds of identifying a tenfold potency boost by a factor of 5 compared to random selection when predictions have an average error of 1.0 kcal/mol relative to experiment [19]. For kinase targets like Wee1, free energy frameworks have successfully identified novel potent chemical scaffolds while optimizing kinome-wide selectivity profiles, demonstrating the methods' utility in addressing challenging selectivity problems [7].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Tools and Resources for Free Energy Simulations

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Packages | Primary Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Simulation Engines | AMBER [18] [3], GROMACS [20], CHARMM [20], OpenMM [19] | Molecular dynamics simulation | AMBER and GROMACS widely used with explicit solvent models [3] [20] |

| Free Energy Analysis | alchemlyb [3], FastMBAR [19] | Free energy estimation from simulation data | alchemlyb provides TI, FEP, and MBAR estimators [3] |

| Force Fields | AMBER force fields [3], CHARMM force fields [20] | Molecular mechanical parameterization | Choice affects accuracy; consistent parameterization critical [3] |

| System Preparation | antechamber (AMBER), CGenFF (CHARMM) | Small molecule parameterization | Careful partial charge assignment essential for accuracy [3] |

| Enhanced Sampling | λ-dynamics [19], Metadynamics [2] | Improved phase space sampling | LaDyBUGS enables multi-compound sampling in single simulation [19] |

Diagram 2: Computational Ecosystem for Free Energy Calculations. The tool landscape spans force fields, simulation engines, estimators, and analysis packages.

Free Energy Perturbation, Thermodynamic Integration, and BAR/MBAR analysis represent powerful equilibrium methods for predicting binding affinities in drug discovery. While these approaches share common theoretical foundations in statistical mechanics, they offer complementary strengths in practical applications. TI provides a straightforward numerical integration approach, FEP enables direct estimation of free energy differences through exponential averaging, and BAR/MBAR offer statistically optimized estimators for improved precision. Recent advances in sampling algorithms and analysis methods have significantly enhanced the efficiency and accuracy of these calculations, with modern implementations achieving errors near or below 1.0 kcal/mol compared to experimental measurements. As these methods continue to evolve alongside improvements in force fields, sampling algorithms, and computational hardware, their role in accelerating structure-based drug design is expected to expand further, particularly for challenging target classes like membrane proteins and in selectivity optimization across gene families.

Alchemical free energy calculations are pivotal for predicting molecular binding affinities in drug discovery. Traditional equilibrium methods, while accurate, often suffer from slow convergence due to inadequate sampling of rare events. This article details the application of non-equilibrium switching (NES) simulations, steered by the Crooks Fluctuation Theorem (CFT), to accelerate these calculations significantly. We provide explicit protocols for executing NES, complete with a toolkit of essential reagents and software, and demonstrate through benchmark cases that this approach can reduce simulation walltime while maintaining chemical accuracy, offering a robust solution for high-throughput computational screening.

Alchemical free energy (AFE) calculations are a cornerstone of computational chemistry and drug discovery, providing rigorous predictions of binding affinities and solvation thermodynamics [18]. These methods compute free energy differences by transitioning a system along an artificial, or "alchemical," pathway parameterized by a coupling parameter (λ), effectively connecting two thermodynamic states of interest [1]. Despite their foundational role, conventional equilibrium AFE methods, such as Thermodynamic Integration (TI) and Free Energy Perturbation (FEP), can be prohibitively slow for complex systems. This is because they require exhaustive sampling of conformational space, including rare events with high energy barriers that are seldom visited during simulation timescales [21] [22].

The convergence challenges and high computational cost of equilibrium methods have spurred the adoption of non-equilibrium approaches. These methods leverage fundamental results from stochastic thermodynamics, notably the Crooks Fluctuation Theorem (CFT) and the Jarzynski equality [22]. The CFT, discovered in the late 1990s, relates the work distributions of a forward and its time-reversed process to the equilibrium free energy difference [23]. This relationship allows researchers to extract equilibrium thermodynamic properties from fast, irreversible (non-equilibrium) simulations. By performing many rapid, non-equilibrium transitions, practitioners can achieve a dramatic reduction in simulation walltime compared to slow, equilibrium transformations [24] [21]. This article presents detailed Application Notes and Protocols for implementing these non-equilibrium methods, specifically focusing on Non-Equilibrium Switching (NES) and the CFT, within the broader context of accelerating alchemical free energy calculations for drug development.

Theoretical Foundation

The Crooks Fluctuation Theorem

The Crooks Fluctuation Theorem provides a direct connection between the thermodynamics of an equilibrium process and the statistics of work performed during non-equilibrium realizations of that process. For a system in contact with a heat reservoir at constant temperature, the CFT states [23] [22]:

$$\frac{P{A \rightarrow B}(W)}{P{B \rightarrow A}(-W)} = \exp[\beta (W - \Delta F)]$$

Here:

- (P_{A \rightarrow B}(W)) is the probability distribution of work (W) measured during the forward process (from state A to state B).

- (P_{B \rightarrow A}(-W)) is the probability distribution of work for the reverse process (from state B to A), where the work is taken with the opposite sign.

- (\beta = (kB T)^{-1}) is the inverse temperature, where (kB) is Boltzmann's constant and (T) is the temperature.

- (\Delta F = F(B) - F(A)) is the equilibrium free energy difference between the two states.

A key implication of the CFT is that the point where the forward and reverse work distributions cross, (P{A \rightarrow B}(W) = P{B \rightarrow A}(-W)), identifies the work value that is exactly equal to the free energy difference, (W = \Delta F) [23] [21]. The theorem also implies the Jarzynski equality, (\Delta F = -\beta^{-1} \ln \langle \exp(-\beta W) \rangle), which allows estimating (\Delta F) from the work values of the forward process alone [23] [22].

From Theory to Practice: Non-Equilibrium Switching (NES)

In computational practice, the CFT is applied through Non-Equilibrium Switching (NES) simulations. A control parameter λ in the system's Hamiltonian is switched from 0 (state A) to 1 (state B) in a finite, often short, amount of time. The work for each trajectory is calculated as the integral of the derivative of the Hamiltonian with respect to λ along the switching path [22]:

$$W{A \rightarrow B} = \int0^{t_{\text{switch}}} \frac{\partial H(\mathbf{r}, \mathbf{p}; \lambda)}{\partial \lambda} \dot{\lambda} dt'$$

The primary advantage of NES is speed. By driving the system rapidly, one can generate many independent trajectories quickly, bypassing the slow conformational relaxation that can plague equilibrium methods. The dissipated work (W_d = W - \Delta F), which is always positive on average due to the second law, is explicitly accounted for by the CFT through the statistical analysis of the work distributions [25]. Recent advances, such as "nonequilibrium force matching," further optimize this process by learning forces that guide time-reversed evolution, enhancing the accuracy of free energy estimates [24].

Application Notes

Non-equilibrium methods are particularly advantageous in scenarios where equilibrium simulations struggle with slow conformational relaxation or where computational throughput is a priority.

Key Application Domains

- Systems with Trapped Waters: Relative binding free energy (RBFE) calculations can fail when water molecules in a binding site become "trapped" and cannot rearrange on the simulation timescale. A NES protocol using three consecutive switches (to apply restraints, transform the ligand, and remove restraints) has been shown to yield accurate RBFEs where other methods may fail or show hysteresis [26].

- Ligand Unbinding and Permeation: Steered Molecular Dynamics (SMD), a form of NES, applies an external force to accelerate processes like ligand unbinding from a protein or ion permeation through a channel, making these rare events tractable for simulation and analysis [22].

- Solvation Free Energies: The solvation free energy of ions or small molecules can be efficiently calculated by performing multiple fast, non-equilibrium alchemical transitions between the solvated and unsolvated states [21].

Performance and Validation

Benchmarking studies demonstrate the effectiveness of NES approaches. The following table summarizes quantitative performance data from selected applications.

Table 1: Performance Benchmarks of Non-Equilibrium Methods

| System | Method | Result | Statistical Error | Key Advantage | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RBFEs with trapped waters | Three-switch NES | Within 1.1 kcal/mol of experiment | < 0.4 kcal/mol | Manages water rearrangement | [26] |

| Molecular solids & solvation | Non-equilibrium force matching | Accurate vs. TI ground truth | N/A | Marked walltime reduction | [24] |

| NaCl dissociation | Targeted MD with CFT | Accurate ΔG | N/A | Direct free energy from work distributions | [22] |

These examples show that NES methods are not just faster but can also achieve chemical accuracy (typically defined as an error < 1.0 kcal/mol), which is essential for reliable predictions in drug design [26]. The convergence of NES can be more efficient than traditional methods because it avoids the need to sample high-energy barriers that are orthogonal to the alchemical pathway.

Experimental Protocols

This section provides a detailed, step-by-step protocol for calculating a solvation free energy using the Crooks Fluctuation Theorem, a common benchmark task.

Protocol: Solvation Free Energy via CFT

Objective: Calculate the solvation free energy of a sodium ion in water. Principle: Perform multiple independent, fast alchemical transformations (Forward: "decoupling" the ion from water; Reverse: "coupling" the ion to water). The free energy is determined from the intersection of the resulting work distributions [21].

Workflow Diagram:

Step-by-Step Instructions

System Equilibration

- Prepare the two end-states of the alchemical transformation. For sodium ion solvation:

- State A (λ=0): A simulation box containing water and a fully interacting sodium ion.

- State B (λ=1): A simulation box containing water and a sodium ion with its interactions to the water completely turned off.

- Run equilibrium simulations at both state A and state B to ensure the systems are well-equilibrated. Save multiple, statistically independent snapshots from these equilibrium runs to use as starting structures for the non-equilibrium simulations [21].

- Prepare the two end-states of the alchemical transformation. For sodium ion solvation:

Forward (FWD) Non-Equilibrium Trajectories

- For each starting snapshot from State A (λ=0), initiate a simulation where the λ parameter is linearly switched from 0 to 1 over a short, predefined time (e.g., 10-50 ps). This morphs the ion from a fully interacting state to a non-interacting state.

- The simulation input file (

forward.mdpin GROMACS) must be configured for this fast switching, specifying the λ-schedule and saving the energy derivativedhdl.xvg[21].

Reverse (REV) Non-Equilibrium Trajectories

- For each starting snapshot from State B (λ=1), initiate a simulation where λ is switched from 1 to 0 over the same duration. This is the time-reversed process.

Work Calculation

- For every forward and reverse trajectory, calculate the total work done. In practice, this is often done by integrating the

dhdl.xvgfile with respect to time and λ. For a linear switching schedule, this simplifies to a sum: ( W = \sum \frac{\partial H}{\partial \lambda} \Delta \lambda ). Use a script to automate this calculation for all trajectories [21].

- For every forward and reverse trajectory, calculate the total work done. In practice, this is often done by integrating the

Free Energy Estimation via CFT

- Compile the work values from all forward runs into a list ( W{\text{FWD}} ) and from all reverse runs into a list ( -W{\text{REV}} ).

- Plot the probability distributions ( P{\text{FWD}}(W) ) and ( P{\text{REV}}(-W) ).

- The free energy difference ( \Delta F ) is the work value at which these two distributions intersect [21]. Alternatively, one can perform a maximum-likelihood fit to the logarithm of the CFT equation [22].

Protocol: NES for Relative Binding Free Energies with Trapped Waters

Objective: Calculate the relative binding free energy between two ligands where a key water molecule is trapped in the binding site for one ligand but not the other. Principle: A three-step NES protocol with restraints ensures the trapped water is properly managed during the alchemical transformation of one ligand into the other [26].

Workflow Diagram:

Step-by-Step Instructions

Apply Restraints (NES Switch 1): Initiate the first non-equilibrium switch. Apply or modify positional restraints on the protein, ligand, and the specific water molecule(s) of interest to maintain the binding site geometry during the subsequent ligand transformation. The work ( W_1 ) for this step is recorded.

Alchemical Transformation (NES Switch 2): With the restraints in place, perform the core alchemical transformation. The λ parameter is switched to morph the Hamiltonian describing Ligand A into that describing Ligand B. This step changes the ligand's identity while the restraints prevent the trapped water from undergoing a large, slow rearrangement. Record the work ( W_2 ).

Remove Restraints (NES Switch 3): Perform the final non-equilibrium switch by gradually removing the restraints applied in Step 1. Record the work ( W_3 ).

Free Energy Calculation: The total work for the entire cycle is ( W{\text{total}} = W1 + W2 + W3 ). This protocol is typically run in both directions (Ligand A to B and B to A). The Jarzynski equality is then applied to the exponential average of the total work from multiple trajectories to obtain the relative binding free energy difference (( \Delta \Delta G )) [26].

The Scientist's Toolkit