Advanced MD Simulation Protocols for Small Protein Folding: A Comprehensive Guide for Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive guide to Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulation protocols specifically tailored for studying small protein folding, a critical process in structural biology and drug development.

Advanced MD Simulation Protocols for Small Protein Folding: A Comprehensive Guide for Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulation protocols specifically tailored for studying small protein folding, a critical process in structural biology and drug development. It covers foundational principles, from the basic setup of all-atom simulations in explicit solvent to advanced constrained MD and replica exchange methods that enhance conformational sampling. The content details practical protocols using tools like GROMACS, addresses common challenges such as limited timescales and force field accuracy, and explores integrative validation strategies that combine simulation data with experimental techniques like NMR and FRET. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, this guide synthesizes current methodologies to facilitate more accurate and efficient in silico protein folding studies, with direct implications for understanding disease mechanisms and advancing therapeutic design.

The Fundamentals of Protein Folding and MD Simulation Principles

The "protein folding problem" stands as a fundamental challenge in molecular biology, addressing the mystery of how a linear amino acid sequence dictates the acquisition of a unique, biologically active three-dimensional structure [1]. This process represents a remarkable physical transformation where an unstructured polypeptide chain spontaneously folds into a complex native conformation through a process guided by intrinsic physicochemical principles and cellular machinery. The significance of this problem extends beyond basic science to therapeutic applications, as protein misfolding and aggregation underlie numerous human diseases, including neurodegenerative disorders like Alzheimer's and Parkinson's disease [2] [3].

The folding problem encompasses three closely related puzzles: (1) the folding code—understanding what balance of interatomic forces dictates native structure formation; (2) the folding mechanism—elucidating the pathways and kinetics by which folding occurs; and (3) structure prediction—developing computational methods to predict native structure from amino acid sequence alone [1]. Christian Anfinsen's seminal experiments with ribonuclease in the 1960s established the thermodynamic hypothesis, demonstrating that the native structure represents the thermodynamically stable state under physiological conditions, determined solely by the amino acid sequence [1] [3]. This principle established that folding is a spontaneous process, though in living cells it often occurs with the assistance of molecular chaperones [2].

The process of protein folding follows a hierarchical organization. The primary structure—the linear amino acid sequence—contains all necessary information to specify the final native conformation [2]. This sequence first gives rise to secondary structures such as α-helices and β-sheets, stabilized by hydrogen bonds between backbone amide and carbonyl groups [2]. These elements then pack together to form the tertiary structure, stabilized by hydrophobic interactions, hydrogen bonds, van der Waals forces, and sometimes disulfide bridges [2]. Multiple folded polypeptide chains may further assemble into quaternary structures to form functional multimers [2].

Driving Forces and Mechanisms of Protein Folding

Fundamental Driving Forces

Protein folding is a spontaneous process governed by several key thermodynamic drivers and opposed by conformational entropy [2]. The dominant force is the hydrophobic effect, which drives the collapse of hydrophobic side chains into the protein's interior, away from the aqueous environment [1] [2]. This process is entropically favorable as it releases ordered water molecules that were forming "cages" around hydrophobic residues [2]. The multitude of hydrophobic groups interacting within the protein core contributes significantly to stability through accumulated van der Waals forces [2].

Additional stabilizing forces include the formation of intramolecular hydrogen bonds, particularly those enveloped in hydrophobic cores, which contribute more to stability than those exposed to aqueous solvent [2]. Electrostatic interactions (salt bridges) and van der Waals forces also provide important contributions to native state stability, though their individual effects are typically smaller than the hydrophobic effect [1]. While proteins are only marginally stable (typically 5-10 kcal/mol more stable than unfolded states), the collective contribution of these numerous weak interactions sufficiently stabilizes the native conformation [1].

Folding Mechanisms and Theoretical Models

Several theoretical models have been proposed to explain how proteins navigate the vast conformational space to find their native structures. The diffusion-collision model proposes that early local structures (microdomains) form and then diffuse until they collide and assemble into the native structure [3]. The nucleation-condensation model suggests that folding initiates with the formation of a weak nucleus that then templates the rapid, cooperative folding of the remainder of the structure [3]. More recently, the foldon model has proposed that proteins contain independently folding units ("foldons") that assemble in a hierarchical manner [3].

The energy landscape theory provides a comprehensive framework for understanding folding, visualizing the process as a funnel-like multidimensional surface where the native state occupies the global free energy minimum [1] [3]. According to this view, a protein solves its large global optimization problem as a series of smaller local optimization problems, growing and assembling native structure from peptide fragments rather than searching randomly through all possible conformations [1].

Table 1: Key Forces in Protein Folding

| Force/Interaction | Relative Contribution | Molecular Basis | Role in Folding |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrophobic Effect | Dominant | Entropic gain from releasing ordered water molecules | Drives chain collapse and core formation |

| Hydrogen Bonding | Significant (~1-4 kcal/mol per bond) | Dipole-dipole interactions between amide and carbonyl groups | Stabilizes secondary structures and tertiary contacts |

| Van der Waals Forces | Moderate | Transient dipole-induced dipole interactions | Optimizes packing in protein interior |

| Electrostatic Interactions | Context-dependent | Attraction between opposite charges (salt bridges) | Stabilizes specific tertiary interactions |

| Conformational Entropy | Opposing force | Loss of chain flexibility upon folding | Favors unfolded state; must be overcome |

Computational Methods and Molecular Dynamics Approaches

Traditional Molecular Dynamics Simulations

Classical molecular dynamics (MD) simulation has served as a "computational microscope" for studying protein folding, enabling researchers to observe the dynamic evolution of molecular structures at atomic resolution [4]. Traditional MD calculates forces using prescribed interatomic potential functions, allowing simulations of folding processes on timescales up to milliseconds for small proteins [4]. However, these methods face significant limitations in achieving chemical accuracy and accessing biologically relevant timescales for larger systems [4].

Standard MD protocols for protein folding typically employ explicit solvent models (such as TIP3P or SPC water), periodic boundary conditions, and particle-mesh Ewald methods for handling long-range electrostatic interactions [5]. Temperature control is often maintained using Langevin dynamics or Nosé-Hoover thermostats, while pressure control may be implemented with Parrinello-Rahman barostats [5]. Despite advances in computing hardware, simulating the complete folding process for all but the smallest proteins remains computationally challenging due to the multiple timescales involved in folding events.

Machine Learning-Enhanced Simulation Methods

Recent breakthroughs in artificial intelligence have revolutionized protein folding simulations by dramatically improving both accuracy and efficiency [4] [6] [7]. AI2BMD (Artificial Intelligence-based Ab Initio Biomolecular Dynamics System) represents a significant advance, enabling efficient simulation of full-atom large biomolecules with ab initio accuracy [4]. This system uses a protein fragmentation scheme and machine learning force field to achieve generalizable accuracy for proteins comprising more than 10,000 atoms, reducing computational time by several orders of magnitude compared to density functional theory while maintaining quantum chemical accuracy [4].

Another innovative approach, CGSchNet, employs a graph neural network to learn effective interactions between coarse-grained particles, accurately simulating protein dynamics without explicitly modeling solvent or atomic detail [6]. This method enables larger proteins and complex systems to be explored, including transitions between folded states and predictions of metastable states relevant to biological function [6].

For high-throughput sampling of protein conformational ensembles, BioEmu provides a denoising diffusion model that generates protein structures in just 30-50 denoising steps [7]. This approach can sample 10,000 independent protein structures within minutes to hours on a single GPU, dramatically accelerating the exploration of protein structural landscapes [7].

Table 2: Comparison of Computational Approaches for Protein Folding

| Method | Spatial Resolution | Timescale Access | Key Advantages | Representative Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classical MD | All-atom (0.1-1 Å) | Nanoseconds to milliseconds | Physically detailed dynamics | Small protein folding; local conformational changes |

| AI2BMD | All-atom with ab initio accuracy | Nanoseconds to microseconds | Quantum chemical accuracy; no force field parameterization needed | Folding mechanisms; precise energy calculations |

| CGSchNet | Coarse-grained (1-2 residues per bead) | Microseconds to seconds | Efficient large protein simulation; transferable across proteins | Large protein dynamics; folding thermodynamics |

| BioEmu | All-atom ensemble | Equilibrium distribution sampling | Rapid generation of structural ensembles; high throughput | Conformational landscapes; mutant effects |

Experimental Protocols and Standardization

Consensus Experimental Conditions for Folding Studies

To enable meaningful comparisons across laboratories and studies, the field has established standardized experimental conditions for protein folding research [5]. These consensus conditions include a standard temperature of 25°C, which represents a compromise between physiological relevance (37°C) and experimental practicality, while maximizing backward compatibility with existing literature [5]. For denaturation studies, urea is recommended as the denaturant of choice over guanidinium salts due to fewer complications from ionic strength effects, though alternative denaturants may be necessary for proteins that do not fully unfold in saturated urea solutions [5].

Standard solvent conditions include pH 7.0 buffers (typically 50 mM phosphate or HEPES) with no added salt beyond that provided by the buffer, unless specifically justified by experimental requirements [5]. These conditions provide a consistent baseline for comparing folding kinetics and stability across different protein systems while minimizing confounding variables in interlaboratory comparisons.

Kinetic and Thermodynamic Measurements

The folding kinetics of two-state proteins are typically characterized using chevron plot analysis, which describes the dependence of folding and unfolding rates on denaturant concentration [5]. For phases exhibiting linear chevron diagrams, the natural logarithm of the observed rate constant (lnk) is fit to a linear function of denaturant concentration, with the slope representing the m-value—the sensitivity of the transition state to denaturant [5]. This parameter is typically reported in units of kJ/mol/M for ease of comparison with equilibrium parameters [5].

For systems exhibiting nonlinear chevron plots (rollover), which may indicate intermediate states, transition state movement, or aggregation, researchers are encouraged to report both polynomial extrapolations of the full dataset and linear extrapolations of the linear regions near the midpoint [5]. Importantly, the raw kinetic data should be made available in tabular form to enable future reanalysis as new models emerge [5].

Data Reporting Standards

Comprehensive reporting should include complete structural characterization of the protein construct, including precise amino acid sequence, any modifications, and structural details relevant to interpretation of folding data [5]. For kinetic phases without kinetic rollover, reported parameters should include the folding and unfolding rate constants in water (kf and ku), the denaturant dependence of these rates (mf and mu), and the equilibrium m-value when available [5]. The availability of raw kinetic data in numerical format is strongly encouraged, either within publications or as supplementary material, to facilitate future meta-analyses and methodological developments [5].

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Protein Folding Studies

| Reagent/Material | Specifications | Application/Function | Example Sources/Products |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Denaturants | Ultra-pure urea; >99.5% purity | Protein destabilization; folding/unfolding studies | Sigma-Aldrich U1250; Thermo Fisher BP169-500 |

| Standard Buffers | 50 mM phosphate or HEPES, pH 7.0 | Maintain consistent pH and ionic strength | Various pharmaceutical grade |

| Fluorescent Dyes | ANS, Sypro Orange, Tryptophan | Detection of conformational changes; binding studies | Thermo Fisher S6650, S5692 |

| Chromatography Media | Size-exclusion; ion-exchange | Protein purification; separation of folding intermediates | GE Healthcare Sephadex; Bio-Rad Bio-Gel |

| Chaperone Proteins | GroEL/GroES, Hsp70, Hsp90 | Study assisted folding; mimic cellular environment | Recombinant expression systems |

| Reduction/Oxidation Systems | DTT, GSH/GSSG, PDI | Control disulfide bond formation | Sigma-Aldrich 43815, G6529 |

| Stopped-Flow Instrumentation | Sub-millisecond mixing | Rapid kinetic measurements of folding | Applied Photophysics SX20 |

| CD Spectrophotometers | Far-UV capability (190-250 nm) | Secondary structure quantification | Jasco J-1500; Applied Photophysics Chirascan |

| Temperature Control Systems | ±0.1°C accuracy | Maintain standardized folding conditions | Thermo Scientific circulating baths |

Applications to Therapeutic Development

Understanding protein folding mechanisms has profound implications for therapeutic development, particularly for diseases characterized by protein misfolding and aggregation [3]. Neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer's, Parkinson's, and prion diseases involve the accumulation of amyloid fibrils formed by misfolded proteins [2] [3]. Similarly, many metabolic diseases and certain cancers are associated with disruption of protein homeostasis (proteostasis) [3].

Molecular chaperones, including heat shock proteins (HSPs), have emerged as important therapeutic targets [2] [3]. These proteins assist in proper folding, prevent aggregation, refold misfolded proteins, and aid in protein degradation [2]. Therapeutic strategies include chaperone modulators that enhance cellular folding capacity, proteostasis pathway inhibitors that disrupt cancer cell adaptation mechanisms, and emerging approaches to increase proteome resilience [3].

Computational methods are playing an increasingly important role in therapeutic design, enabling researchers to simulate protein folding pathways, identify intermediate states prone to aggregation, and design stabilized protein variants for biocatalysis and biotherapeutics [4] [6]. The ability to accurately predict folding free energies of protein mutants opens new possibilities for rational drug design and understanding disease-associated mutations [6].

The continued integration of experimental and computational approaches provides a powerful framework for addressing the remaining challenges in the protein folding problem, with significant implications for understanding fundamental biological processes and developing novel therapeutic interventions for protein folding diseases.

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation is a powerful computational method for analyzing the physical movements of atoms and molecules over time. By simulating the system's evolution, MD provides an atomic-resolution view of dynamic processes that are often impossible to observe directly through experimentation. This approach is fundamentally rooted in Richard Feynman's powerful assumption that "all things are made of atoms, and that everything that living things do can be understood in terms of the jigglings and wigglings of atoms" [8]. In the context of drug discovery and protein folding research, MD simulations have revolutionized our understanding of molecular recognition, protein flexibility, and ligand binding mechanisms, moving beyond the initial 'lock-and-key' theory to models that account for conformational changes and stochastic atomic motions [8]. The method serves as a crucial bridge between theoretical molecular physics and practical applications in biophysics and drug development, particularly within the Model-informed Drug Development framework where it provides quantitative predictions and data-driven insights [9].

Theoretical Foundation: Integrating Force Fields and Newtonian Mechanics

Newton's Laws of Motion: The Engine of MD Simulations

Molecular dynamics simulations are fundamentally based on Newton's classical laws of motion, which provide the mathematical foundation for predicting how atomic positions evolve over time. In an MD simulation, the trajectories of atoms and molecules are determined by numerically solving Newton's equations of motion for a system of interacting particles [10]. The primary equation used is Newton's second law: F = ma, where F is the force exerted on a particle, m is its mass, and a is its acceleration. For each atom in the system, the force is calculated as the negative gradient of the potential energy function (F = -∇U), which describes how energy changes with atomic positions [8] [10]. These calculations are performed iteratively in extremely small time steps (typically 1-2 femtoseconds), with the simulation advancing through millions of iterations to model molecular behavior over nanosecond to microsecond timescales [8] [11].

Molecular Mechanics Force Fields: The Rulebook for Atomic Interactions

Force fields represent the mathematical framework that describes the potential energy of a molecular system as a function of its atomic coordinates. These force fields are parameterized sets of equations and constants that approximate the quantum-mechanical forces governing atomic behavior using classical mechanical approximations [8]. The total potential energy in a typical force field is calculated as the sum of several contributing terms:

Utotal = Ubonded + U_nonbonded

Where the bonded terms include bond stretching, angle bending, and dihedral torsions, while non-bonded terms account for van der Waals interactions and electrostatic forces [8]. The following table summarizes the key components of molecular mechanics force fields:

Table 1: Fundamental Components of Molecular Mechanics Force Fields

| Energy Component | Mathematical Formulation | Physical Description | Parameters Required |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bond Stretching | Ubond = ∑ kb(l - l_0)^2 | Energy required to stretch or compress a chemical bond from its equilibrium length | Bond force constant (kb), Equilibrium bond length (l0) |

| Angle Bending | Uangle = ∑ kθ(θ - θ_0)^2 | Energy required to bend the angle between three bonded atoms from its equilibrium value | Angle force constant (kθ), Equilibrium angle (θ0) |

| Dihedral Torsions | Udihedral = ∑ kφ[1 + cos(nφ - δ)] | Energy associated with rotation around a central chemical bond | Dihedral force constant (k_φ), Periodicity (n), Phase angle (δ) |

| van der Waals | UVDW = ∑[(Aij/rij^12) - (Bij/r_ij^6)] | Non-bonded interactions between atoms due to fluctuating electron clouds | Atom-specific well depth (ε), van der Waals radius (σ) |

| Electrostatics | Uelec = ∑(qiqj)/(4πε0εrrij) | Coulombic interactions between partial atomic charges | Partial atomic charges (qi, qj), Dielectric constant (ε_r) |

Commonly used force fields include AMBER (Assisted Model Building with Energy Refinement), CHARMM (Chemistry at HARvard Macromolecular Mechanics), and GROMOS (GROningen MOlecular Simulation) [8]. Each differs in parameterization strategies and specific functional forms but shares the common goal of accurately reproducing molecular behavior while maintaining computational efficiency.

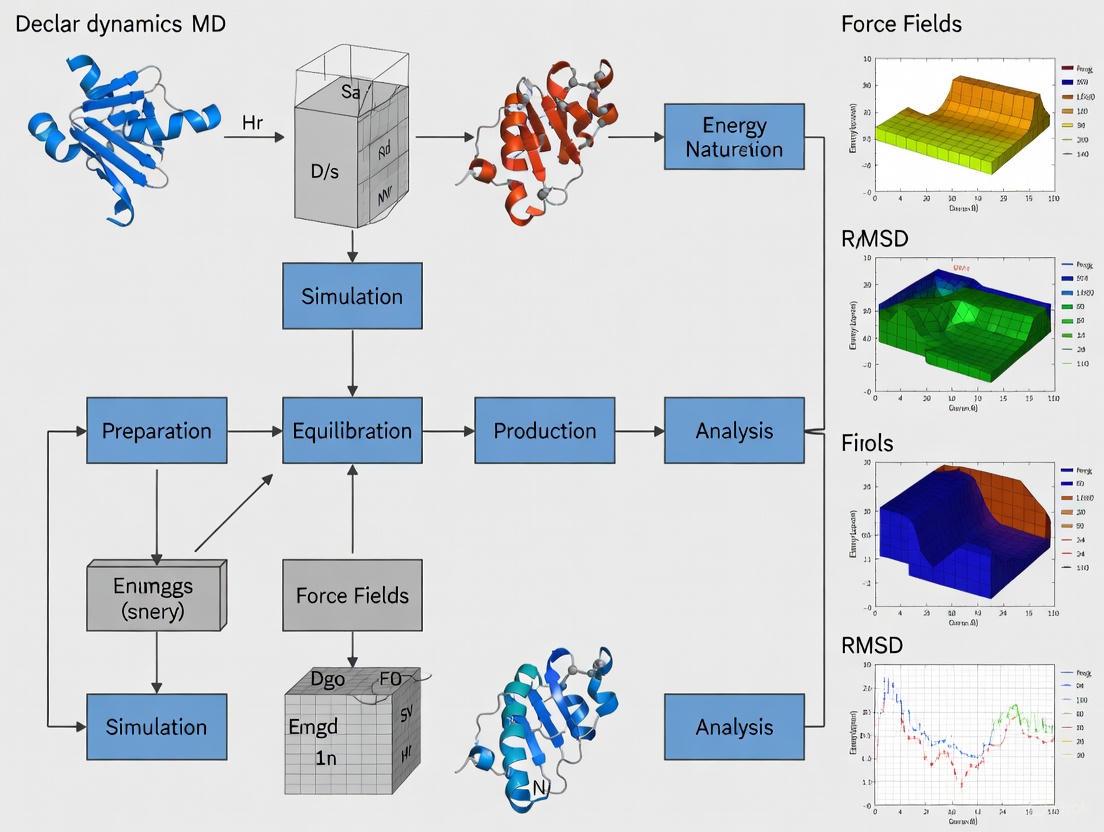

MD Simulation Workflow: From System Setup to Analysis

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive workflow for a molecular dynamics simulation, highlighting the iterative process of force calculation and integration:

System Preparation and Equilibration Protocol

Initial System Setup:

- Obtain Initial Coordinates: Source atomic coordinates from experimental structures (Protein Data Bank), homology modeling, or previous simulations [8].

- Select Appropriate Force Field: Choose from established force fields (AMBER, CHARMM, GROMOS) based on the system composition and research objectives [8].

- Solvate the System: Embed the molecular system in an explicit solvent box (e.g., TIP3P, SPC/E water models) or use an implicit solvent model to reduce computational cost [10].

- Add Counterions: Introduce ions to neutralize system charge and mimic physiological ionic strength when relevant.

Energy Minimization:

- Perform steepest descent or conjugate gradient minimization to remove steric clashes and unfavorable contacts.

- Continue minimization until the maximum force falls below a specified tolerance (typically 100-1000 kJ/mol/nm).

System Equilibration:

- NVT Ensemble Equilibration: Run simulation with constant Number of particles, Volume, and Temperature (100-500 ps) using thermostats (Berendsen, Nosé-Hoover) to stabilize temperature at target value (e.g., 300K).

- NPT Ensemble Equilibration: Continue with constant Number of particles, Pressure, and Temperature (100-500 ps) using barostats (Parrinello-Rahman, Berendsen) to achieve correct density.

Production Simulation and Analysis

Production MD Simulation:

- Run simulation with appropriate timestep (typically 1-2 fs) using integration algorithms (Verlet, Leap-frog) [10].

- Apply constraint algorithms (SHAKE, LINCS) to allow longer timesteps by fixing fastest vibrations [10].

- Simulate for system-dependent duration (nanoseconds to microseconds) based on the biological process being studied [11].

- Save trajectory frames at regular intervals (1-100 ps) for subsequent analysis.

Trajectory Analysis Methods:

- Structural Stability: Calculate root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) of protein backbone atoms relative to starting structure.

- Flexibility Analysis: Compute root-mean-square fluctuation (RMSF) of residue positions to identify flexible regions.

- Conformational Sampling: Perform principal component analysis to identify essential dynamics and major conformational changes.

- Energetic Analysis: Calculate interaction energies between protein and ligands or specific residues.

Application to Small Protein Folding Research

MD simulations provide exceptional insights into protein folding mechanisms by offering atomic-level resolution of the folding process. The methodology enables researchers to characterize folding pathways, intermediate states, and transition states that are difficult to capture experimentally [11]. Several key studies demonstrate the power of MD in this domain:

Table 2: MD Simulations of Small Protein Folding Systems

| Protein System | Simulation Details | Key Findings | Validation Approach |

|---|---|---|---|

| Villin Headpiece (HP-35) | 20 × 1.0 μs simulations at 300K [11] | Refolding from extended states to structures with <1.0 Å Cα RMSD from crystal structure | Comparison to X-ray structure; identification of vital stability region consistent with mutagenesis [11] |

| Trp-cage | Multiple 20 ns simulations at 325K [11] | Successful refolding prediction with correct intramolecular contacts | Force field energy assessment; structural comparison to experimental data [11] |

| Chymotrypsin Inhibitor 2 (CI2) | 200 ns simulation at 348K (Tm) [11] | Demonstration of microscopic reversibility - same contacts form during folding as break during unfolding | Comparison of physical properties, topology, and contact maps between starting and refolded states [11] |

| FBP28 WW Domain | Unfolding simulations under various denaturant conditions [11] | Transition state structure identification with first turn native-like while second turn forms during folding | Comparison to experimental Φ-values; validation of simulated TS structures [11] |

The following diagram illustrates how MD simulations reveal the protein folding landscape through sampling of various conformational states:

Specialized Protocol for Protein Folding Simulations

Enhanced Sampling for Folding Studies:

- Temperature Replica Exchange MD: Run parallel simulations at different temperatures (300-500K) with periodic exchange attempts to enhance conformational sampling.

- Metadynamics: Apply biasing potential along carefully selected collective variables (e.g., radius of gyration, native contacts) to accelerate transitions over energy barriers.

- Umbrella Sampling: Use harmonic restraints along a reaction coordinate to calculate free energy landscapes for folding processes.

Folding Analysis Metrics:

- Q-value: Calculate fraction of native contacts formed relative to reference structure.

- Radius of Gyration: Monitor protein compactness throughout simulation trajectory.

- Secondary Structure Content: Track formation of α-helices and β-sheets using DSSP or similar algorithms.

- Contact Map Analysis: Identify specific residue-residue interactions characteristic of native state.

Successful implementation of MD simulations for protein folding research requires both specialized software and computational resources. The following table details essential components of the MD research toolkit:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Resources for MD Simulations

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function/Purpose | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| MD Software Packages | AMBER [8], CHARMM [8], NAMD [8], GROMACS | Primary simulation engines with optimized algorithms for different hardware architectures | AMBER/CHARMM offer specialized force fields; NAMD/GROMACS optimized for parallel computing |

| Force Fields | AMBER ff19SB, CHARMM36m, OPLS-AA/M | Parameter sets defining atomic interactions; some specifically optimized for proteins | CHARMM36m includes corrections for folded state stability; ff19SB improves backbone torsion accuracy |

| Solvent Models | TIP3P [10], SPC/E [10], TIP4P-EW, implicit solvent (GB/SA) | Water representation balancing accuracy and computational cost | Explicit models more accurate but computationally expensive; implicit models enable longer timescales |

| System Preparation Tools | CHARMM-GUI, PACKMOL, tleap | Generate initial simulation systems with proper solvation and ion placement | CHARMM-GUI provides web-based interface for complex system building |

| Analysis Software | MDAnalysis, VMD, CPPTRAJ, MDTraj | Trajectory analysis for structural, dynamic, and energetic properties | MDAnalysis offers Python API for customized analysis pipelines |

| Specialized Hardware | GPU Clusters [8], Anton Supercomputer [8] | Accelerate calculations through parallel processing | GPUs provide order-of-magnitude speedups [8]; Anton designed specifically for MD [8] |

| Validation Databases | Protein Data Bank, NMR chemical shifts, DEER distance distributions | Experimental data for force field validation and simulation assessment | Critical for ensuring simulated structures agree with experimental observations |

Current Challenges and Methodological Limitations

Despite significant advances, several challenges remain in MD simulations of protein folding. The high computational demands typically restrict simulations to microsecond timescales, while many folding events occur on longer timescales [8] [11]. Current force fields, while continually improving, still employ approximations that neglect certain quantum mechanical effects, particularly regarding electronic polarization and hydrogen bonding [8] [10]. Additionally, adequate sampling of conformational space remains difficult, potentially leading to biased or incomplete understanding of folding landscapes [11].

Emerging approaches to address these limitations include the development of polarizable force fields [8], enhanced sampling algorithms [8], specialized hardware like Anton supercomputers [8], and machine learning approaches such as Microsoft's BioEmu biomolecular emulator that can rapidly sample protein conformational ensembles [7]. As these methodologies mature, MD simulations will continue to close the gap between computational modeling and experimental observations, providing increasingly accurate insights into the fundamental principles of protein folding with significant implications for drug discovery and structural biology [9] [11].

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation serves as a "computational microscope," providing atomic-level insight into the process of protein folding, a fundamental event in biological activity [12] [13]. However, a significant challenge persists: the timescales of functionally important structural changes in proteins (microseconds to milliseconds) are often inaccessible to conventional MD simulations, which are typically limited to nanoseconds or microseconds due to computational constraints [12] [13]. This limitation arises from the phenomenon of "rare events," where the system becomes trapped in an energy basin, separated from other conformations by high energy barriers [12]. Consequently, conventional MD may fail to exhaustively sample the conformational space, leading to an inaccurate representation of the free-energy landscape (FEL), which is crucial for understanding folding mechanisms and stability [12]. This Application Note details enhanced sampling protocols and a novel AI-driven methodology designed to overcome these challenges, enabling accurate characterization of folding pathways and thermodynamics for small proteins.

Key Computational Challenges in Protein Folding

The Timescale and Sampling Problem

In MD simulations, the conformational space of a protein is characterized by numerous energy basins separated by energy barriers [12]. Crossing these high barriers is a rare event on the timescale of conventional MD, causing the simulation to become trapped in a non-representative subset of conformations [12]. This inefficient sampling makes it difficult to investigate thermodynamic properties like protein folding and binding affinity with conventional MD, as the simulation cannot adequately reflect equilibrium conditions [12].

The Energetic Accuracy Problem

The accuracy of an MD simulation is fundamentally tied to the force field—the model that calculates the forces governing atomic motions [13]. Classical force fields, while fast, are approximations and can lack chemical accuracy [4]. Although they have improved substantially, their imperfections introduce uncertainty into the simulation results [13]. In contrast, ab initio MD methods like density functional theory (DFT) provide high accuracy but are computationally prohibitive for large biomolecules, scaling with approximately O(N³) complexity for system size N [4].

Table 1: Comparison of MD Simulation Approaches for Protein Folding

| Simulation Approach | Computational Cost | Energetic Accuracy | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional (Classical) MD | Lower | Moderate (Approximate) | Inefficient sampling of rare events; force field inaccuracies [12] [13] |

| Ab Initio MD (e.g., DFT) | Exceedingly High (O(N³)) | High (Chemically Accurate) | Not scalable to large proteins; a simulation of a 746-atom protein can take 92 minutes/step [4] |

| Enhanced Sampling MD | Moderate (Higher than conventional MD) | Dependent on underlying force field | Efficiency depends on the correct choice of reaction coordinate or collective variable [12] |

| AI-Driven Ab Initio MD (AI2BMD) | High, but significantly lower than DFT | High (Near Ab Initio Accuracy) | A 746-atom protein simulation takes ~0.125 seconds/step, >4 orders of magnitude faster than DFT [4] |

Enhanced Sampling Protocols for Free-Energy Landscape Construction

Enhanced sampling methods are designed to facilitate barrier crossing, allowing the system to explore conformational space more efficiently and thus construct an accurate FEL [12]. The following protocols outline key methods.

Protocol: Umbrella Sampling for Free-Energy Reconstruction

Objective: To calculate the free-energy profile along a specific reaction coordinate (e.g., distance between protein domains, radius of gyration) [12].

- Define the Reaction Coordinate: Select a collective variable (ξ) that describes the progression from the unfolded to the folded state.

- Set Up Umbrella Windows: Perform multiple independent MD simulations, each with a harmonic bias potential applied to the reaction coordinate. The minima of these potentials should be spaced along the entire range of ξ, ensuring overlap between adjacent windows [12].

- Run Simulations: Conduct a conventional MD simulation for each window, recording the sampled values of ξ.

- Unbiased Analysis with WHAM: Use the Weighted Histogram Analysis Method (WHAM) to combine the data from all biased simulations, removing the effect of the umbrella potentials to reconstruct the unbiased probability distribution along ξ [12].

- Construct FEL: Calculate the free-energy landscape as F(ξ) = -k˅B T ln(P(ξ)), where P(ξ) is the unbiased probability distribution obtained from WHAM.

Protocol: Parallel Tempering (Temperature Replica Exchange)

Objective: To enhance conformational sampling by simulating replicas of the system at different temperatures, allowing exchanges between them [12].

- Define Temperature Ladder: Choose a set of temperatures ranging from the temperature of interest (e.g., 300 K) to a significantly higher temperature. The number of replicas and the temperature spacing should be chosen to ensure a non-negligible exchange rate [12].

- Run Concurrent Simulations: Simulate each replica independently at its assigned temperature.

- Attempt Replica Exchanges: Periodically attempt to swap the configurations of two adjacent replicas (i and j). The swap is accepted with a probability based on the Metropolis criterion, which ensures detailed balance is maintained [12].

- Analyze the Output: The trajectory at the temperature of interest (lowest temperature) will show enhanced sampling because it can access higher-temperature conformations during the exchange process. Analysis (e.g., FEL construction) is performed using snapshots from this replica.

Protocol: Essential Dynamics Sampling (EDS) for Protein Folding

Objective: To bias a simulation towards a target structure (e.g., the native fold) by utilizing collective motions derived from an equilibrated trajectory [14].

- Equilibrate and Perform ED Analysis: Run a conventional MD simulation of the native state. After equilibration, build and diagonalize the covariance matrix of the positional fluctuations of the Cα carbon atoms to obtain eigenvectors defining collective motions [14].

- Generate an Unfolded State (Expansion): Starting from the native structure, run an EDS simulation in "expansion mode," accepting only steps that increase the distance from the native structure in the subspace defined by the chosen eigenvectors [14].

- Perform Folding Simulation (Contraction): Using the unfolded structure from step 2, initiate an EDS simulation in "contraction mode." In this mode, a regular MD step is accepted only if it does not increase the distance from the native structure in the chosen subspace. If it does, the coordinates are projected onto a hypersphere maintaining the previous distance [14].

- Pathway Analysis: Analyze the resulting trajectory to identify folding intermediates and pathways, which can be compared with experimental data [14].

Diagram 1: Essential Dynamics Sampling Workflow for Protein Folding.

AI-AcceleratedAb InitioProtocol: AI2BMD

Objective: To simulate full-atom proteins with ab initio accuracy at a computational cost several orders of magnitude lower than DFT, enabling the observation of folding and unfolding [4].

System Preparation:

- Obtain the initial protein structure (folded, unfolded, or intermediate) from experimental data or prior simulations.

- Solvate the protein in an explicit solvent model. AI2BMD uses the polarizable AMOEBA force field for water [4].

AI-Driven Energy and Force Calculation:

- The AI2BMD system fragments the protein into overlapping dipeptide units. This universal fragmentation approach covers only 21 types of protein units, making it generalizable [4].

- At each simulation step, a machine learning force field (MLFF) potential, specifically ViSNet, calculates the energy and atomic forces. This MLFF is trained on a comprehensively sampled dataset of protein unit conformations calculated at the DFT level [4].

- The MLFF encodes physics-informed molecular representations and computes four-body interactions with linear time complexity, providing highly accurate energy and force estimations [4].

Simulation and Analysis:

- Run the MD simulation using the AI2BMD potential. The system can explore the conformational space efficiently, reaching hundreds of nanoseconds and capturing folding/unfolding events [4].

- Analyze the trajectory to derive accurate 3J couplings for comparison with NMR experiments, calculate free energies of folding, and estimate thermodynamic properties like melting temperature [4].

Table 2: Performance Metrics of AI2BMD vs. Density Functional Theory (DFT)

| Protein (Number of Atoms) | AI2BMD Computation Time per Step (s) | DFT Computation Time per Step | Accuracy (Force MAE, kcal mol⁻¹ Å⁻¹) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chignolin (175 atoms) | ~0.072 | 21 minutes | 1.974 (vs. 8.094 for MM) [4] |

| Albumin-Binding Domain (746 atoms) | ~0.125 | 92 minutes | Not Specified [4] |

| Aminopeptidase N (13,728 atoms) | ~2.610 | >254 days (infeasible) | 1.056 (vs. 8.392 for MM) [4] |

Diagram 2: AI2BMD System Architecture for Ab Initio Accuracy.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools and Resources for Protein Folding MD

| Research Reagent | Function in Protein Folding Simulation |

|---|---|

| GROMACS | A highly efficient software package for performing MD simulations, including energy minimization, equilibration, and production runs, with built-in analysis tools [15] [14]. |

| MDAnalysis | A Python library for analyzing MD simulation trajectories, enabling the calculation of properties like RMSD, RMSF, and hydrogen bonds, and for performing dimensionality reduction [16]. |

| AMOEBA Force Field | A polarizable force field used in the AI2BMD system to provide a more accurate treatment of electrostatic interactions in the explicit solvent environment [4]. |

| ViSNet | A machine learning force field model that serves as the potential for AI2BMD. It uses physics-informed molecular representations to calculate energy and forces with ab initio accuracy [4]. |

| Weighted Histogram Analysis Method (WHAM) | A statistical method critical for unbinding the data from umbrella sampling simulations to reconstruct the unbiased free-energy landscape [12]. |

| VMD / PyMOL | Molecular visualization software used to visualize simulation trajectories, analyze conformational changes, interactively examine structures, and render high-quality images and animations [15]. |

In the realm of molecular dynamics (MD) simulations for small protein folding research, the accurate quantification of conformational sampling and convergence to native states is paramount. Key metrics including Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD), Radius of Gyration (Rg), and Native Contact Formation provide indispensable, complementary insights into the structural, dynamic, and thermodynamic properties of folding proteins. These metrics serve as the primary validation tools for assessing both traditional MD and emerging machine learning (ML)-based simulation methods, enabling researchers to compare generated ensembles against reference experimental structures or long MD trajectories [17] [11]. Their collective application is crucial for advancing protocol development, force field refinement, and the understanding of folding mechanisms, with recent studies demonstrating their critical role in benchmarking novel coarse-grained models [18], latent diffusion generators [17], and accelerated sampling techniques [19].

Metric Definitions and Theoretical Foundations

Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD)

RMSD quantifies the average displacement of atoms between a simulated protein structure and a reference structure (often the native state), providing a global measure of structural similarity. It is calculated using the formula:

\[RMSD = \sqrt{\frac{1}{N} \sum{i=1}^{N} \delta{i}^{2}}\]

where \(N\) is the number of atoms (typically Cα atoms for backbone comparison), and \(δ_i\) is the distance between atom \(i\) in the simulated and reference structures after optimal superposition. Lower RMSD values indicate closer convergence to the native fold. For example, successful refolding simulations of villin headpiece variants have reported Cα RMSD values below 1.0 Å relative to crystal structures [11]. RMSD is often tracked throughout a simulation trajectory to monitor folding progression and stability [19].

Radius of Gyration (Rg)

Radius of Gyration (Rg) describes the overall compactness of a protein structure, calculated as the root mean square distance of all atoms from their common center of mass:

\[Rg = \sqrt{\frac{\sum{i=1}^{N} mi |\mathbf{r}i - \mathbf{r}{\text{cm}}|^2}{\sum{i=1}^{N} m_i}}\]

where \(m_i\) is the mass of atom \(i\), \(r_i\) its position, and \(r_{\text{cm}}\) the center of mass. A decreasing Rg profile often signals hydrophobic collapse, an early stage in the folding pathway, while a stable, native-like Rg indicates proper tertiary packing. In folding studies of Protein L and CspTm, Rg measurements via single-molecule FRET revealed sequence-specific collapse at low denaturant concentrations, a finding corroborated by MD simulations [11].

Native Contact Formation

Native Contact Formation measures the fraction of non-local atomic contacts present in the native state that are formed during a simulation. A contact is typically defined when two heavy atoms (or Cβ atoms) are within a cutoff distance (e.g., 4.5 Å). The fraction of native contacts (Q) is calculated as:

\[Q = \frac{1}{N{\text{native}}} \sum{(i,j) \in \text{native}} \Theta( r{\text{cut}} - |r{i,j}| )\]

where \(N_{\text{native}}\) is the total number of contacts in the native structure, the sum runs over all native contact pairs (i,j), \(Θ\) is the Heaviside step function, \(r_{\text{cut}}\) is the cutoff distance, and \(r_{i,j}\) is the distance between atoms i and j in the simulated structure. This metric, often plotted as a time series or as part of a free energy landscape, is a sensitive indicator of folding cooperativity and the formation of specific stabilizing interactions. For instance, in AMD simulations of eight helical proteins, native contact analysis confirmed successful folding into stable native structures [19].

Table 1: Summary of Key Protein Folding Metrics and Their Interpretation

| Metric | Structural Property Assessed | Typical Values (Folded) | Interpretation of Trends |

|---|---|---|---|

| RMSD (Cα atoms) | Global backbone conformation | < 2.0 – 3.0 Å [11] | Decreasing trend → Folding progression; Stable low value → Native state stability |

| Radius of Gyration (Rg) | Global compactness | Protein-specific, comparable to native structure Rg | Decreasing trend → Hydrophobic collapse; Stable value → Proper tertiary packing |

| Native Contact Fraction (Q) | Formation of specific tertiary interactions | ~1.0 (fully folded) | Increasing trend → Cooperative folding; Stable high value → Native-like interaction network |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Standard Protocol for Metric Calculation from MD Trajectories

The following workflow outlines the standard procedure for calculating key folding metrics from an MD simulation trajectory. Adherence to this protocol ensures consistency and reproducibility in analysis, which is critical for comparing results across different studies and simulation systems [17] [11].

Trajectory Preparation: The raw MD trajectory must be pre-processed. This includes ensuring consistency in periodic boundary conditions, removing water and ions if the analysis is focused on the protein solute, and making sure the trajectory is correctly aligned to a reference frame to avoid artifacts from global rotation/translation.

Structure Superimposition: For RMSD calculation, each frame of the trajectory is optimally superimposed onto the reference native structure. This step minimizes the RMSD by rotating and translating the simulated structure, thus isolating internal conformational changes from global motions. This is typically done using the Cα atoms of well-structured regions or the entire protein backbone.

Metric Calculation:

- RMSD: Compute the RMSD for the desired set of atoms (e.g., backbone, Cα, all heavy atoms) for every trajectory frame after superposition.

- Rg: Calculate the radius of gyration for the protein (or a defined subdomain) for each frame.

- Native Contacts: For each frame, compute the fraction of native contacts (Q) by comparing the current atomic distances to those in the native structure using a defined cutoff (e.g., 4.5 Å for Cβ atoms).

Time-Series Analysis: Plot each metric as a function of simulation time. This visualizes the folding pathway, stability of the native state, and potential unfolding events.

Statistical Analysis and Validation:

- Convergence Analysis: Check if the metrics have reached a stable plateau, indicating convergence of the simulation in a particular state (folded, unfolded, or intermediate).

- Ensemble Averaging: For multiple simulations (e.g., replica exchange or independent runs), average the metrics across the ensemble to get a more statistically robust estimate.

- Cross-Validation with Experiment: Compare simulation-derived metrics with experimental data where available. For example, Rg from simulation can be compared to SAXS or FRET data [11], and native contact patterns can be indirectly validated against NMR data.

Application in Advanced ML-Based Generators

The validation of modern machine-learned ensemble generators relies heavily on these established metrics. For instance, the aSAM (atomistic structural autoencoder model) and AlphaFlow models are benchmarked by comparing the RMSD, RMSF (root mean square fluctuation), and native contact distributions of their generated ensembles against long, reference MD simulations [17]. Similarly, coarse-grained models like CGSchNet are evaluated on their ability to predict the correct folded state (low RMSD, high Q) and reproduce the fluctuations (related to Rg) and free energy landscapes of all-atom simulations [18].

Table 2: Representative Protocol Parameters from Recent Folding Studies

| Study / Method | System | Simulation Time | Key Metric Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accelerated MD (AMD) [19] | 8 Helical Proteins (e.g., TC5B, 1WN8) | 40-180 ns (folding event) | RMSD < 1.0 Å, native contact analysis, Rg convergence to native value |

| Machine-Learned CG (CGSchNet) [18] | Chignolin, TRP-cage, BBA, Villin | PT and long Langevin simulations | Free energy landscapes projected via RMSD and Q; comparison of folded state Rg |

| aSAM (Latent Diffusion) [17] | Test set from ATLAS/mdCATH | N/A (Ensemble generation) | Cα RMSD distribution (initRMSD), WASCO score for contacts, RMSF correlation |

| Brute-Force MD [11] | HP-36, CI2, FBP28 WW domain | 200 ns - 1 μs | Cα RMSD, Rg, SASA, native secondary structure content |

This table catalogs key computational tools, datasets, and software utilized in modern protein folding simulation research, as evidenced by recent literature.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Solutions for Protein Folding Studies

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function in Folding Research | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| GROMACS [20] | Software Package | High-performance MD simulation engine. | Performing all-atom, explicit solvent MD simulations for protein folding and unfolding [20] [21]. |

| AMBER14SB [19] | Force Field | Defines potential energy terms for atoms in classical MD. | Providing parameters for protein and solvent interactions in folding studies of helical proteins [19]. |

| ATLAS Database [17] [22] | MD Dataset | A large, curated set of all-atom MD simulations for diverse protein folds. | Training and benchmarking ML-based generative models like aSAM and AlphaFlow [17]; training predictors like PEGASUS [22]. |

| mdCATH Dataset [17] | MD Dataset | MD simulations for thousands of globular domains at multiple temperatures. | Training temperature-conditioned generative models like aSAMt to study thermal behavior [17]. |

| PEGASUS [22] | Deep Learning Tool | Predicts MD-derived flexibility metrics (RMSF, dihedral fluctuations) from sequence. | Rapidly estimating protein dynamics properties without running expensive simulations [22]. |

| HADDOCK [20] | Docking Software | High Ambiguity Driven docking for biomolecular complexes. | Docking WRKY DNA-binding domains to W-box DNA prior to MD analysis [20]. |

| CGSchNet [18] | Machine-Learned Force Field | A transferable coarse-grained force field for proteins. | Running efficient, predictive simulations of folding/unfolding for new protein sequences [18]. |

The integrated analysis of RMSD, Radius of Gyration, and Native Contact Formation remains the cornerstone of rigorous validation in protein folding simulations. As the field progresses with more complex systems, multi-scale models, and AI-driven generators [17] [18] [23], these metrics provide the essential, quantitative language for assessing the physical accuracy and predictive power of novel computational protocols. Their continued application, following standardized calculation workflows, is fundamental to bridging the gap between simulation and experiment, ultimately enhancing our understanding of protein folding mechanics and facilitating advances in molecular biology and drug development.

Practical MD Protocols: From System Setup to Production Runs

Within the broader context of investigating small protein folding mechanisms, the preparation of a biologically realistic system is a critical prerequisite for obtaining reliable molecular dynamics (MD) simulation data. The accuracy of folding pathways, free energy landscapes, and intermediate state identifications depends fundamentally on a properly constructed initial system. This protocol details the comprehensive procedure for converting a raw protein structure file (PDB) into a fully solvated, simulation-ready system using the GROMACS 2025 simulation package. The methodology is specifically optimized for small proteins, typically under 100 residues, where folding phenomena occur on tractable timescales. By following this structured approach, researchers can ensure their simulations of protein folding and unfolding events are conducted with atomic-level precision and thermodynamic rigor, providing a solid foundation for subsequent drug discovery and biomedical research applications.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Software

Table 1: Essential computational tools and files for GROMACS system preparation.

| Component Name | Type | Primary Function in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| GROMACS 2025 | Software Suite | MD simulation engine used for all system preparation and simulation steps [24]. |

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) File | Input File | Initial atomic coordinates of the protein structure (e.g., a small fast-folding protein like villin or WW domain). |

| Force Field (e.g., AMBER, CHARMM, OPLS) | Parameter Set | Defines the potential energy function, governing all interatomic interactions within the system [25] [26]. |

| Solvent Model (e.g., SPC, TIP3P, TIP4P) | Parameter Set | Defines the water model used to solvate the protein, critical for simulating aqueous biological environments [25]. |

vdwradii.dat |

Database File | Contains Van der Waals radii for atoms; used by gmx solvate to determine steric clashes during solvation [27]. |

Molecular Topology (.top) |

Output/Input File | Describes all the molecules in the system and their interaction parameters, generated by gmx pdb2gmx [28]. |

GROMACS Structure (.gro) |

Output/Input File | Standard coordinate file format in GROMACS containing atom positions, velocities, and box dimensions [28]. |

Run Input File (.tpr) |

Output/Input File | A portable binary file containing all simulation parameters, generated by gmx grompp to serve as input for gmx mdrun [28]. |

The entire process of converting a PDB file into a solvated system suitable for MD simulation follows a sequential workflow. The following diagram maps the key stages, decision points, and primary outputs.

Detailed Step-by-Step Protocol

Step 1: Generate Protein Structure and Topology

The initial and crucial step involves processing the raw PDB file to generate a GROMACS-compatible structure file and a corresponding molecular topology. This is accomplished using the gmx pdb2gmx tool.

- Objective: To translate a PDB file of a protein into a GROMACS structure file (

.gro) and a molecular topology file (.top). The topology contains a complete description of all interactions in the protein [28]. - Command:

- Key Interactive Selections:

- Force Field (

-ff): You will be prompted to select a force field (e.g.,charmm27,amber99sb-ildn). The choice must be consistent with the intended scientific question and the force field's validation for protein folding studies [25] [26]. - Water Model (

-water): Select a water model (e.g.,tip3p,spc/e). This model must be compatible with the chosen force field [25]. - Terminal and Protonation States: The program will automatically assign charged termini (NH₃⁺ and COO⁻) for polypeptide chains. For histidine residues, it will select a protonation state (HIS, HIE, HID) based on optimal hydrogen-bonding geometry, which can be manually overridden with the

-hisflag [25].

- Force Field (

- Critical Outputs:

conf.gro: The processed protein coordinates in GROMACS format.topol.top: The system topology, which now includes the protein.posre.itp: A file containing position restraints for the protein heavy atoms, useful for the initial equilibration stages.

Step 2: Define the Simulation Box

The protein must be placed in a finite simulation box for which periodic boundary conditions (PBC) are applied. The gmx editconf tool is used for this purpose.

- Objective: To center the protein in a simulation box of defined size and shape.

- Command:

- Parameter Rationale:

-c: Centers the protein in the box.-d 1.2: Sets the distance between the protein and the box edge to 1.2 nm. This ensures a sufficient buffer of solvent around the protein, which is critical for accurate simulation of folding events by minimizing artificial periodicity effects.-bt dodecahedron: Defines a dodecahedral box, which approximates a sphere and is more efficient for simulating globular proteins than a cubic box, as it requires fewer solvent molecules [28] [26].

Step 3: Solvate the System

The box containing the protein is now filled with solvent molecules using the gmx solvate tool. This step creates a realistic aqueous environment for the protein folding simulation.

- Objective: To add explicit solvent molecules to the simulation box, resulting in a solvated system.

- Command:

- Parameter Explanation:

-cp boxed.gro: Specifies the solute (the centered protein in its box) as the input coordinate file.-cs spc216.gro: Specifies the solvent coordinate file. The defaultspc216.grois a pre-equilibrated box of SPC water molecules, which can also be used for other 3-site models like TIP3P after a short equilibration [27].-o solvated.groand-p topol.top: Write the solvated coordinates and update the topology to include the added solvent molecules.

- Underlying Algorithm: The program removes any solvent molecule that overlaps with the solute, where overlap is defined as a distance between any solute and solvent atom less than the sum of their scaled Van der Waals radii. The radii are read from the

vdwradii.datdatabase file and scaled by a default factor of-scale 0.57to achieve a realistic density for proteins in water [27].

Table 2: Key options for the gmx solvate command.

| Option | Default Value | Function | Consideration for Protein Folding |

|---|---|---|---|

-cp |

protein.gro |

Input coordinate file of the solute (protein in a box). | Ensure the box is large enough to accommodate unfolding. |

-cs |

spc216.gro |

Input coordinate file of the solvent. | Use a water model consistent with your force field selection in Step 1. |

-scale |

0.57 |

Scale factor for VdW radii from vdwradii.dat. |

The default is optimized for a density of ~1000 g/L; altering this is generally not recommended [27]. |

-shell |

0 |

Adds a water layer of specified thickness (nm) around the solute. | Useful for maintaining a spherical solvent shell during simulations. |

-radius |

0.105 |

Default VdW distance (nm) for atoms not found in vdwradii.dat. |

This protocol provides a standardized, robust framework for preparing solvated systems of small proteins for molecular dynamics simulations focused on folding research. By meticulously executing these steps—generating a correct topology, defining an appropriate periodic box, and adding explicit solvent—researchers establish a physically accurate foundation for their simulations. The resulting system is primed for the subsequent stages of energy minimization and equilibration, which are necessary to relax any residual steric clashes and achieve stable temperature and density. A reliably prepared system is paramount for obtaining meaningful insights into protein folding dynamics, stability, and the atomic-level interactions that govern these fundamental biological processes.

In the realm of molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, the term "force field" refers to the combination of mathematical formulas and associated parameters that describe the potential energy of a biomolecular system as a function of its atomic coordinates [29]. The accuracy and reliability of any MD simulation, particularly for studying complex processes like protein folding, are fundamentally dependent on the choice of an appropriate force field. Force fields encode the physical chemistry of molecular interactions, balancing computational efficiency with physical accuracy to enable simulations of biological processes across relevant timescales. For researchers investigating small protein folding mechanisms, selecting a force field that accurately captures the delicate balance of interactions governing folding pathways, stable states, and transition barriers is paramount to generating biologically meaningful results.

The development of deep learning methods has revolutionized static protein structure prediction, but understanding dynamic folding processes still requires MD simulations that depend critically on force field accuracy [30] [18]. Modern protein folding studies demand force fields that can realistically simulate the transitions between multiple conformational states, including folded, unfolded, and intermediate structures, while maintaining computational feasibility [30]. This technical note provides a comprehensive comparison of three widely used biomolecular force fields—AMBER, CHARMM, and GROMOS—focusing on their application in small protein folding research, with practical implementation protocols for the GROMACS simulation package.

Force Field Comparison: AMBER, CHARMM, and GROMOS

Core Characteristics and Parameterization Philosophies

The AMBER, CHARMM, and GROMOS force fields represent distinct philosophical approaches to parameterization with different strengths and limitations for protein folding studies.

AMBER (Assisted Model Building with Energy Refinement) employs a functional form that includes bond stretching, angle bending, proper and improper dihedrals, and non-bonded interactions (electrostatics and Lennard-Jones) [29]. The parameterization of AMBER force fields combines quantum mechanical calculations with experimental data, making it particularly accurate for proteins and nucleic acids. Recent versions have significantly improved the treatment of backbone and side-chain torsions to better capture protein folding landscapes.

CHARMM (Chemistry at HARvard Macromolecular Mechanics) utilizes a similar functional form to AMBER but differs in its parameterization strategy, which places greater emphasis on reproducing experimental data for crystal structures, NMR data, and thermodynamic properties [29] [31]. This empirical approach aims to achieve balanced interactions between different molecular components, which is crucial for simulating complex processes like protein folding where multiple interaction types compete.

GROMOS (GROningen MOlecular Simulation) employs a different philosophy with a united-atom approach, representing aliphatic hydrogen atoms implicitly within their parent carbon atoms [29]. This reduces the number of particles in the system, offering computational advantages that enable longer timescale simulations. The parameterization of GROMOS force fields heavily relies on fitting to thermodynamic properties, particularly liquid thermodynamic data, which can enhance the accuracy of solvation effects in folding simulations.

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Major Biomolecular Force Fields

| Characteristic | AMBER | CHARMM | GROMOS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Atom Representation | All-atom | All-atom | United-atom (aliphatic hydrogens implicit) |

| Parameterization Basis | QM calculations + experimental data | Experimental data emphasis (crystal structures, NMR) | Liquid thermodynamic data |

| Functional Form | Comprehensive bonded and non-bonded terms | Comprehensive bonded and non-bonded terms | Simplified with united atoms |

| Computational Efficiency | Moderate | Moderate | Higher (fewer explicit particles) |

| Training & Validation | Combination of QM and experimental data | Heavy emphasis on experimental validation | Thermodynamic property fitting |

Performance in Protein Folding Applications

The ability to accurately simulate protein folding remains a significant benchmark for force field validation. Recent studies have evaluated these force fields on their capacity to predict folded states, folding mechanisms, and the relative stability of different conformational states.

Small Protein Folding studies have revealed that all major force fields can generally fold small fast-folding proteins to their native states, but differences emerge in the precise characterization of folding pathways and the relative populations of intermediate states [18]. AMBER and CHARMM typically provide more detailed atomic resolution but at greater computational cost, while GROMOS offers advantages for sampling broader conformational spaces.

Disordered Proteins and Intrinsically Disordered Regions (IDRs) present particular challenges. The balance between protein-water and protein-protein interactions must be carefully parameterized to avoid artificial over-structuring or excessive disorder. Recent versions of AMBER (e.g., Amber99sb-ildn) and CHARMM (e.g., CHARMM36m) have incorporated adjustments to improve their performance for disordered systems [31].

Metastable State Prediction varies between force fields, with some demonstrating a tendency to stabilize specific types of non-native interactions. For example, certain AMBER parameters have shown improved capability in predicting metastable states of folded, unfolded, and intermediate structures, as well as fluctuations of intrinsically disordered proteins [18].

Table 2: Performance Characteristics for Protein Folding Studies

| Performance Metric | AMBER | CHARMM | GROMOS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Native State Stability | Generally accurate with modern versions | Good with CHARMM36m | Variable depending on version |

| Folding Mechanism | Detailed but pathway-sensitive | Physically realistic | More approximate |

| Disordered Protein Handling | Good with -ildn variants | Excellent with CHARMM36m | Less accurate for IDPs |

| Secondary Structure Balance | Slight α-helix bias in older versions | Well-balanced in recent versions | Context-dependent |

| Computational Cost | Higher | Higher | Lower (united atom) |

| Timescale Access | Nanoseconds to microseconds | Nanoseconds to microseconds | Microseconds to milliseconds |

Practical Implementation Protocols

System Setup and Simulation Workflow

Implementing successful protein folding simulations requires careful attention to system setup parameters and simulation protocols. The following workflow outlines a standardized approach applicable to small protein systems, with force field-specific considerations noted where appropriate.

Protein Structure Preparation begins with obtaining an initial protein structure, which can be derived from experimental data (e.g., PDB files) or predicted structures. For folding studies, starting from extended or unfolded states may be necessary to observe folding pathways. The PDB file provides atomic coordinates, residue names, and chain identifiers that form the foundation of your molecular system [31].

Force Field Selection requires consistent application throughout the simulation. As emphasized in the GROMACS documentation, "You should not mix and match force fields. Force fields are designed to be self-consistent, and will not typically work well with other force fields" [32]. This principle is critical for maintaining physical accuracy in your simulations.

Solvation and Ion Addition involves embedding the protein in an appropriate solvent environment, typically using water models specifically parameterized for each force field (e.g., TIP3P for AMBER and CHARMM, SPC for GROMOS). Ion concentration should be adjusted to physiological levels (typically 150mM NaCl) and the system neutralized to balance protein charges.

Simulation Parameters for Folding Studies

The molecular dynamics parameters (.mdp options) in GROMACS control the numerical integration and environmental conditions of your simulation [33]. The following table provides recommended settings for protein folding simulations.

Table 3: Key MDP Parameters for Protein Folding Simulations

| Parameter Category | Setting | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Integrator | md-vv (velocity Verlet) or md (leap-frog) |

Accurate integration with support for extended time steps |

| Time Step | 2 fs (all-atom), 4 fs (united-atom with constraints) | Balance between numerical stability and computational efficiency |

| Temperature Coupling | Velocity rescaling (or Nose-Hoover) | Maintains constant temperature during folding |

| Pressure Coupling | Parrinello-Rahman (for production) | Maintains correct density without introducing artifacts |

| Constraint Algorithm | LINCS (all-atom), SETTLE (water) | Enables longer time steps by constraining bond vibrations |

| Non-bonded Interactions | PME for electrostatics, VdW cut-off 1.0-1.2 nm | Accurate treatment of long-range interactions |

| Neighbor Searching | Verlet list with 20-40 step update frequency | Computational efficiency with maintained accuracy |

Enhanced Sampling for Folding Landscape Characterization

Standard MD simulations may struggle to sufficiently sample the complete folding landscape due to the high free energy barriers between states. Enhanced sampling techniques can improve conformational sampling:

Parallel Tempering/Replica Exchange MD involves running multiple replicas of the system at different temperatures, with periodic exchange attempts between neighboring temperatures. This approach allows conformations to overcome barriers at higher temperatures and populate low-energy states at lower temperatures, providing a more complete mapping of the folding landscape [18].

Metadynamics uses a history-dependent bias potential to discourage the system from revisiting previously sampled configurations, effectively "filling" free energy minima and driving transitions between states. This method is particularly useful for characterizing folding pathways and intermediate states.

Umbrella Sampling employs harmonic restraints along a predefined reaction coordinate (e.g., radius of gyration, native contacts) to enhance sampling in specific regions of conformational space. The potential of mean force (PMF) can then be reconstructed using the weighted histogram analysis method (WHAM) [32].

Successful implementation of protein folding simulations requires both computational tools and methodological knowledge. The following table outlines key resources for researchers.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Resource Category | Specific Tools | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Simulation Software | GROMACS, AMBER, CHARMM/OpenMM, NAMD | MD simulation engines with varying performance characteristics |

| Force Field Databases | AMBER Parameter Database, CHARMM Parameter File, GROMOS Force Field Portal | Source of validated force field parameters |

| System Preparation | pdb2gmx (GROMACS), CHARMM-GUI, tleap (AMBER) | Tools for generating simulation topologies and initial coordinates |

| Analysis Tools | MDAnalysis, GROMACS analysis suite, VMD | Trajectory analysis, visualization, and property calculation |

| Enhanced Sampling | PLUMED, COLVARS | Libraries for implementing advanced sampling techniques |

| Specialized Databases | ATLAS, GPCRmd, MemProtMD [30] | MD trajectories and specialized parameters for specific protein classes |

| Validation Resources | PDBFlex, CoDNaS 2.0 [30] | Experimental data on protein flexibility and conformational diversity |

Force Field Selection Guidelines

Choosing the appropriate force field requires balancing multiple considerations, including the specific research question, protein characteristics, and computational resources. The following decision framework provides guidance for selection:

For all-atom simulations with explicit solvent, AMBER and CHARMM offer the most detailed physical models, with CHARMM36m particularly effective for systems containing disordered regions and AMBER providing excellent performance for well-structured domains.

For enhanced sampling and longer timescales, the united-atom approach of GROMOS provides computational advantages that enable more extensive conformational sampling, though at the cost of atomic detail for aliphatic groups.

For membrane protein systems, specialized force fields and simulation protocols are required. As noted in membrane simulation guidelines, "Choose a force field for which you have parameters for the protein and lipids" and maintain consistency throughout the simulation [32].

Emerging Trends and Future Directions

The field of force field development continues to evolve, with several promising directions emerging:

Machine-Learned Force Fields represent a transformative approach, combining recent deep-learning methods with large and diverse training sets of all-atom protein simulations. These bottom-up coarse-grained force fields demonstrate chemical transferability and can be used for extrapolative molecular dynamics on new sequences not used during model parameterization [18]. These approaches show particular promise for predicting metastable states of folded, unfolded, and intermediate structures while being several orders of magnitude faster than all-atom models.

Integration with AI-Based Structure Prediction tools like AlphaFold creates opportunities for combining static structure prediction with dynamic ensemble characterization. While "AlphaFold only represents a single state of protein structure" and "cannot fully embody a native protein structure with conformational heterogeneity" [34], MD simulations with accurate force fields can expand these static pictures into dynamic ensembles.

Community-Wide Validation Efforts continue to refine force field performance through systematic assessment against experimental data. Researchers should remain informed about these validation studies and consider conducting their own validation against relevant experimental data for their specific protein systems.

In conclusion, the selection of AMBER, CHARMM, or GROMOS for small protein folding research depends on the specific research goals, protein characteristics, and computational resources. AMBER and CHARMM offer sophisticated all-atom representations with excellent accuracy for detailed mechanistic studies, while GROMOS provides computational advantages for enhanced conformational sampling. By following the protocols and decision framework outlined in this technical note, researchers can make informed choices that optimize the physical accuracy and computational efficiency of their protein folding simulations.

{# The document structure and formatting, including tables and dot code block, have been optimized for readability and adherence to user specifications. #}

{# Create a title page and introduction to frame the application note within the requested thesis context. #}

System Setup Essentials: Solvation, Ion Neutralization, and Energy Minimization

Application Notes and Protocols

Within the broader thesis on advancing molecular dynamics (MD) protocols for small protein folding research, the initial setup of the simulation system is a critical determinant of success. Accurate simulation of folding pathways, intermediate states, and free-energy landscapes fundamentally depends on a physically realistic and stable initial condition [35] [30]. This document provides detailed application notes and standardized protocols for the three foundational steps of system setup—solvation, ion neutralization, and energy minimization—with a specific focus on their pivotal role in studies of protein conformational dynamics and folding.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details key software, force fields, and solvent models essential for setting up MD systems for protein folding research, as utilized in cited studies.

Table 1: Key Research Reagent Solutions for MD System Setup

| Item Name | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| GROMACS [35] [36] [37] | A high-performance molecular dynamics software package for simulating biomolecules. | Used for simulation box setup, solvation, ion addition, energy minimization, and production runs. |

| AMBER99SB Force Field [35] [37] | An all-atom force field for proteins, providing parameters for potential energy calculations. | Employed for topology generation of proteins to ensure accurate representation of intramolecular forces during folding simulations [37]. |

| CHARMM36 Force Field [36] [38] | An all-atom force field for proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids. | Used for simulating membrane-associated proteins or complex biomolecular systems [38]. |

| TIP3P Water Model [37] | A 3-site model for explicit solvent water molecules. | Used to solvate the protein system in a water box, creating a physiological environment for folding studies [37]. |

| GAFF (General AMBER Force Field) [37] [38] | A force field for small organic molecules. | Applied to generate topologies for ligands or co-factors that may interact with the folding protein [37]. |

| GB/SA Implicit Solvent [39] | A Generalized Born/Surface Area model for implicit solvation. | Used in constrained MD simulations to accelerate conformational sampling by approximating solvent effects without explicit water molecules [39]. |

| martinize2 [40] | A script for automatically generating coarse-grained Martini model topologies from atomistic structures. | Used to set up systems for longer timescale simulations of large complexes when atomistic detail is not required [40]. |

Core System Setup Protocol

This section outlines a standardized workflow for preparing a solvated, neutralized, and minimized system, suitable for subsequent equilibration and production runs in protein folding simulations. The protocol is largely based on the high-throughput methodology detailed in the Galaxy HTMD tutorial [37] and incorporates parameters from recent literature [35].