Achieving Reliable MD Simulations: A Comprehensive Guide to Thermodynamic Property Convergence

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals to achieve and verify the convergence of thermodynamic properties in Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations.

Achieving Reliable MD Simulations: A Comprehensive Guide to Thermodynamic Property Convergence

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals to achieve and verify the convergence of thermodynamic properties in Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations. We explore the fundamental challenge of ensuring simulations reach true thermodynamic equilibrium, a critical but often overlooked factor that can invalidate results. The content covers foundational concepts of convergence and equilibrium, presents methodological best practices for simulation setup, offers troubleshooting strategies for stubborn systems, and introduces validation techniques including machine learning and comparative analysis. By synthesizing the latest research, this guide aims to enhance the reliability and predictive power of MD simulations in biomedical research, particularly in critical applications like drug solubility prediction and protein-ligand interaction studies.

Understanding Convergence and Equilibrium: The Bedrock of Reliable MD Simulations

The Critical Importance of Convergence in MD Simulations

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation is a powerful computational tool that provides atomic-level insights into the behavior of biomolecules, materials, and drug candidates. However, the reliability of these simulations hinges on a critical, often overlooked assumption: that the system has reached a state of thermodynamic equilibrium, and the measured properties have converged to stable values. The failure to ensure proper convergence represents a fundamental challenge that can invalidate simulation results and lead to misleading scientific conclusions [1]. Within the context of improving the convergence of thermodynamic properties in MD research, this technical support center addresses the specific convergence issues that researchers encounter, providing troubleshooting guidance and methodological frameworks to enhance the reliability of computational studies in drug development and materials science.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What does "convergence" mean in the context of MD simulations? Convergence in MD simulations indicates that the system has reached thermodynamic equilibrium, and the calculated properties have stabilized. A practical working definition is: given a trajectory of length T and a property Aᵢ, if the running average 〈Aᵢ〉(t) shows only small fluctuations around 〈Aᵢ〉(T) for a significant portion of the trajectory after a convergence time t_c, the property can be considered equilibrated. When all relevant properties meet this criterion, the system is fully equilibrated [1].

Q2: Why do my density and energy values stabilize quickly, while other properties like pressure take much longer? Simple thermodynamic properties like density and potential energy often reach stable values rapidly during the initial simulation phase because they are global averages. In contrast, properties like pressure and Radial Distribution Function (RDF) peaks, especially between large molecules like asphaltenes, depend on the slow relaxation of molecular arrangements and require substantially longer simulation times to converge [2] [1].

Q3: How long should I run my simulation to ensure convergence? There is no universal timescale for convergence. It depends on the system size, temperature, and the specific property being measured. For example:

- DNA helix structure (excluding terminal base pairs): 1–5 μs [3]

- Terminal base pair dynamics in DNA: >44 μs and may not be fully converged [3]

- Water transport properties (diffusion, viscosity): Multi-microsecond scales are often necessary [4] Convergence should be determined by monitoring the stability of properties over time, not by predetermined simulation lengths.

Q4: My simulation exhibits large fluctuations in RDF curves. What does this indicate? Significant fluctuations or irregular, multi-peaked RDF curves, particularly for interactions between large molecules like asphaltenes, strongly suggest that the system has not reached equilibrium. These interactions converge much slower than those between smaller, more mobile molecules. Aging effects can further slow this convergence [2].

Q5: Can increasing the simulation temperature help with convergence? Yes, elevated temperatures provide molecules with greater kinetic energy, helping them overcome energy barriers and explore conformational space more rapidly. This accelerates the convergence of both thermodynamic properties and intermolecular interaction profiles [2].

Q6: What is the difference between "partial equilibrium" and "full equilibrium"? A system can be in partial equilibrium when specific, local properties have converged, while others, particularly those dependent on infrequent transitions to low-probability conformations, have not. For instance, average distances may stabilize quickly, but accurate calculation of free energy or transition rates requires full exploration of conformational space, including rare events, and thus longer simulation times [1].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Convergence Problems and Solutions

Table 1: Troubleshooting Convergence Issues in MD Simulations

| Problem | Possible Causes | Diagnostic Steps | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-converging RDF curves | Insufficient sampling of slow molecular rearrangements; strong intermolecular interactions (e.g., between asphaltenes) [2]. | Plot RDF for different molecule types; check if peaks are smooth or fluctuating. | Extend simulation time; increase temperature to accelerate dynamics [2]. |

| Pressure not equilibrating | The simulation box size and shape are still relaxing; long-range interactions not stabilized [2]. | Monitor pressure and volume over time. | Ensure energy minimization is adequate; use longer equilibration in the NPT ensemble. |

| Erratic energy oscillations | Electronic convergence problems in ab initio MD; bad geometry; incorrect simulation parameters [5]. | Check energies at each SCF step for oscillations [5]. | Use a better initial geometry; adjust SCF algorithm (e.g., ALGO in VASP) or smearing scheme; lower EDIFF tolerance [5]. |

| Overly collapsed IDP structures | Force field bias towards overly compact states; unbalanced protein-water interactions [6]. | Compare radius of gyration to experimental data (e.g., SAXS). | Use IDP-optimized force fields (e.g., CHARMM36m, ff14IDPSFF); apply improved water models (e.g., TIP4P-D) [6]. |

| Geometry optimization fails | The algorithm is stuck in a local minimum; initial geometry is unreasonable; forces are inaccurate [5] [7]. | Monitor forces and energies during optimization. Visualize the structure for broken bonds [5]. | Provide a better initial geometry; perturb the geometry to escape local minima; increase the number of optimization steps (NSW in VASP) [5] [7]. |

Workflow for Systematic Convergence Diagnosis

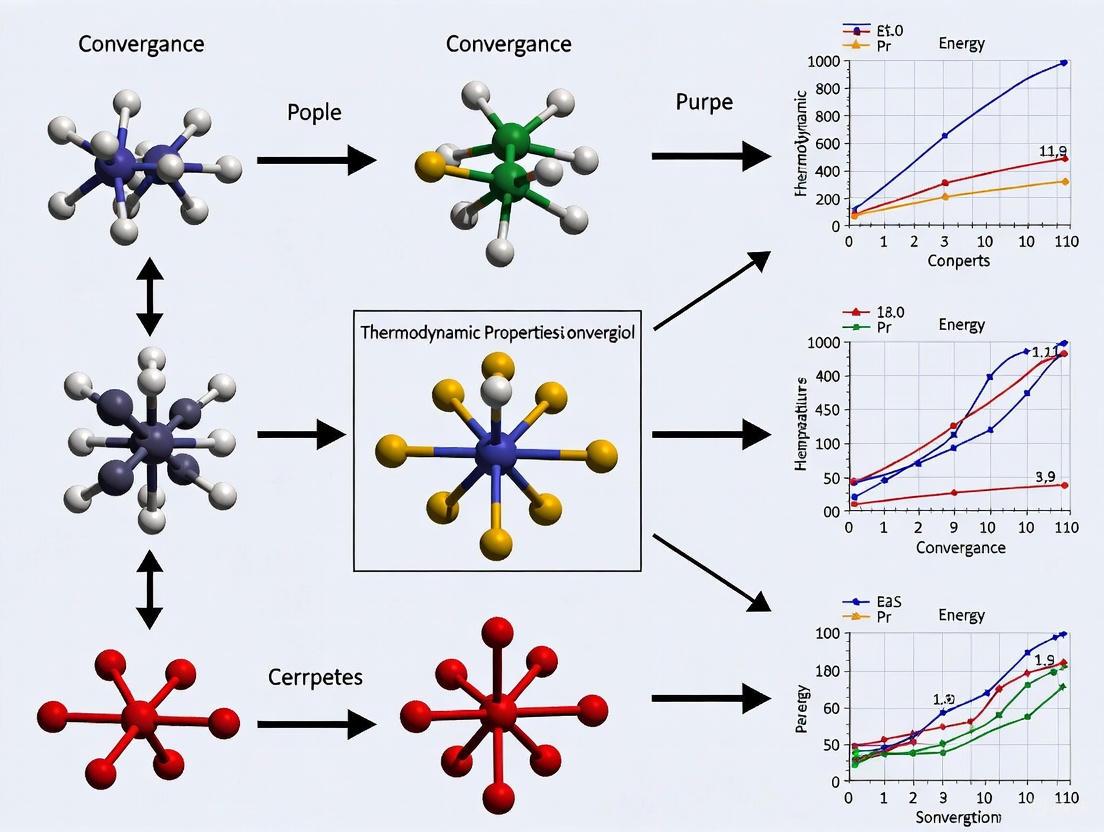

The following diagram outlines a logical pathway for diagnosing and addressing convergence problems.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for MD Convergence

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function | Relevance to Convergence |

|---|---|---|---|

| AMBER ff14SB [6] | Force Field | Parameters for protein simulations. | A standard force field; may over-stabilize helices. Use specialized versions for IDPs. |

| CHARMM36m [6] | Force Field | Optimized for proteins and IDPs. | Reduces bias towards over-collapsed states, improving conformational sampling convergence. |

| TIP4P-D [6] | Water Model | Explicit water model with adjusted dispersion. | Increases protein-water interactions, preventing artificial compaction and improving dynamics. |

| ms2 [8] | Simulation Software | Calculates thermodynamic properties. | Implements advanced methods (Lustig formalism) for reliable property calculation from converged ensembles. |

| Gaussian Process Regression (GPR) [9] | Analysis Method | Reconstructs free-energy surfaces from MD data. | Provides a robust, uncertainty-aware framework for deriving thermodynamic properties from MD trajectories. |

| Neuroevolution Potential (NEP) [4] | Machine-Learned Potential | Fast, accurate interatomic potential. | Enables large-scale, long-duration quantum-accurate MD, crucial for converging transport properties. |

| ASE Optimization Classes [7] | Optimization Algorithm | Structure optimization (e.g., BFGS, FIRE). | Efficiently finds energy minima, a prerequisite for stable MD equilibration. |

Experimental Protocols for Assessing Convergence

This protocol exemplifies how to rigorously assess convergence in a complex molecular system.

- System Preparation: Construct the initial model in a large cubic box with a density much lower than the target to ensure a random molecular distribution.

- Simulation Setup: Perform energy minimization to eliminate excessive repulsive forces. Conduct equilibration in the NPT ensemble to reach the target temperature and pressure.

- Convergence Monitoring:

- Thermodynamic Properties: Track the potential energy, kinetic energy, pressure, and density over the simulation time. Note that energy and density may converge rapidly, while pressure takes longer.

- Intermolecular Interactions: Calculate the Radial Distribution Function (RDF) for all molecular pairs, especially the slowest-converging ones (e.g., asphaltene-asphaltene). The system should only be considered truly equilibrated when these RDF curves have stabilized and show smooth, distinct peaks.

- Acceleration Techniques: To speed up convergence, consider increasing the simulation temperature or using Density Functional Theory (DFT) to understand and model key intermolecular interactions.

This protocol is tailored for simulations of proteins and nucleic acids.

- Initialization: Start from an experimental structure (e.g., from the PDB). Perform standard energy minimization and heating/pressurization equilibration steps.

- Multi-Property Monitoring: Do not rely solely on a single metric. Simultaneously track:

- Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD): Can indicate when the structure has stabilized relative to a reference.

- Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF): Assesses the stability of local flexibility.

- Principal Component Analysis (PCA): Checks if the dominant modes of motion have been adequately sampled.

- Kullback-Leibler Divergence: Quantifies the similarity between conformational distributions from different trajectory segments [3].

- Ensemble Simulations: Run multiple independent simulations starting from different initial velocities. If the aggregated properties from these independent runs match those from a single, very long simulation, it indicates robust convergence [3].

- Time-Averaging: Calculate critical properties as running averages. A property is considered converged when its running average plateaus with only minor fluctuations over a significant portion (e.g., the last third) of the simulation trajectory [1].

This advanced protocol uses Bayesian statistics to derive thermodynamic properties with uncertainty quantification.

- MD Sampling: Perform multiple NVT-MD simulations at different state points (Volume, Temperature). These points can be selected irregularly.

- Data Extraction: From each trajectory, extract ensemble-averaged potential energies and pressures.

- Surface Reconstruction: Use Gaussian Process Regression (GPR) to reconstruct the Helmholtz free-energy surface, F(V,T), from the MD data. The GPR framework naturally propagates statistical uncertainties from the MD sampling.

- Property Calculation: Compute thermodynamic properties as derivatives of the reconstructed F(V,T). For example:

- Pressure: ( P = -\left(\frac{\partial F}{\partial V}\right)T )

- Entropy: ( S = -\left(\frac{\partial F}{\partial T}\right)V )

- Constant-Volume Heat Capacity: ( CV = T \left(\frac{\partial S}{\partial T}\right)V )

- Active Learning (Optional): Implement an active learning loop where the GPR model's uncertainty prediction guides the selection of new (V,T) points for subsequent MD simulations, optimizing the sampling process.

The workflow for this protocol is summarized below.

Defining Thermodynamic Equilibrium for MD Systems

FAQs on Thermodynamic Equilibrium

What constitutes thermodynamic equilibrium in a Molecular Dynamics simulation? In MD, a system is in thermodynamic equilibrium when the statistical properties of the system no longer change systematically over time. A practical working definition is: given a system's trajectory of length T and a property Ai extracted from it, the property is considered "equilibrated" if the fluctuations of its running average, 〈Ai〉(t), remain small for a significant portion of the trajectory after a convergence time, t_c. If all individual properties are equilibrated, the system is considered fully equilibrated [1].

Why is achieving true equilibrium in MD simulations so challenging? Biomolecular systems often possess a complex, high-dimensional energy landscape with many local minima. Simulations can become trapped in these local states, preventing adequate sampling of the full conformational space within practical simulation timescales. Furthermore, the initial structure (e.g., from a Protein Data Bank crystal structure) is typically not in equilibrium for a physiological simulation, requiring the system to relax from this non-equilibrium starting point [1].

How can I distinguish between a system that is equilibrated versus one that is simply "drifting" very slowly? This is a central challenge. A system stuck in a deep local minimum might appear equilibrated for a long duration before a slow drift becomes apparent. There is no absolute guarantee that a system will not deviate later. Therefore, equilibrium is assessed pragmatically by verifying that multiple properties of interest have reached stable, fluctuating plateaus over a substantial segment of the simulation [1].

What is the difference between "partial" and "full" equilibrium? A system can be in partial equilibrium when some properties (often those dependent on high-probability regions of conformational space, like average distances or angles) have converged, while others (like transition rates between states or the free energy, which depend on low-probability regions) have not. Full equilibrium implies that all properties of interest have been converged, meaning the simulation has thoroughly explored all relevant regions of the conformational space [1].

Troubleshooting Guide: Convergence of Thermodynamic Properties

Problem 1: Energy and RMSD Have Plateaued, But Other Properties Keep Drifting

- Explanation: The Root-Mean-Square Deviation (RMSD) and potential energy are common but sometimes insufficient metrics. An RMSD plateau may indicate the system has relaxed from its initial structure and found a stable local energy minimum, but it does not guarantee that all conformational degrees of freedom have sampled their equilibrium distribution [1].

- Solution:

- Monitor Multiple Observables: Track a diverse set of system-specific properties, such as radius of gyration, solvent accessible surface area, specific inter-residue distances, or dihedral angles.

- Use Advanced Detection Tools: Employ robust, automated equilibration detection tools like the RED (Robust Equilibration Detection) Python package, which uses heuristics to determine an optimal truncation point, accounting for autocorrelation in the data [10].

Problem 2: The Simulation is Heavily Influenced by the Initial Configuration

- Explanation: The choice of initial atomic positions can significantly impact the time required to reach equilibrium, especially at high coupling strengths. Unrepresentative starting configurations can impose a long-lasting bias on the simulation [11] [10].

- Solution:

- Improve Initialization: At high coupling strengths, use physics-informed initialization methods (e.g., a perturbed lattice or Monte Carlo pair distribution method) over simple random placement, as they can reduce equilibration time [11].

- Adaptive Equilibration Framework: Implement a systematic framework that uses temperature forecasting and uncertainty quantification in transport properties (like diffusion coefficient) as a quantitative metric for thermalization. This helps define clear termination criteria for equilibration [11].

Problem 3: How to Handle Apparent Non-Equilibrium Behavior Over Long Timescales

- Explanation: Some studies suggest that certain biomolecules may exhibit non-equilibrium behavior over timescales (e.g., hundreds of seconds) far exceeding those achievable by MD simulations. This does not necessarily invalidate all MD results, as many biologically relevant average properties may still converge adequately in multi-microsecond trajectories [1].

- Solution:

- Focus on the Property of Interest: Clarify whether your research question depends on an average property (which may be converged in a partially equilibrated system) or on rare events and transition rates (which require full exploration of conformational space and are much harder to converge) [1].

- State the Uncertainty: When reporting results, explicitly state the convergence time observed for key properties and acknowledge the possibility that longer simulations might alter values dependent on rare events.

Experimental Protocols for Equilibrium Detection

Protocol 1: A Step-by-Step Workflow for Equilibration Assessment

This workflow provides a systematic approach to determine if your system has reached equilibrium.

Protocol 2: Automated Equilibration Detection with the RED Package

For a robust, quantitative assessment of the equilibration point, follow this protocol using the RED package [10].

- Data Preparation: After completing your simulation, export the time-series data for the property you wish to check for equilibration (e.g., potential energy, a specific distance).

- Install RED: Install the open-source Python package RED from GitHub (

github.com/fjclark/red). - Run Analysis: Use the package to analyze your time series. The method employs heuristics that account for autocorrelation to determine the optimal point at which to truncate the initial non-equilibrium data.

- Interpretation: The tool provides a truncation point recommendation. Data before this point should be discarded as equilibration, and data after can be used for production analysis. The method balances the risk of early truncation (which increases bias) and late truncation (which increases variance) [10].

Quantitative Data on Equilibration

Table 1: Impact of Initialization Methods on Equilibration Efficiency

The choice of how to initialize particle positions can significantly affect how quickly a system equilibrates, particularly under certain conditions [11].

| Initialization Method | Key Principle | Recommended Use Case | Performance Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| Uniform Random | Random placement of particles | Low coupling strength systems | Less efficient at high coupling |

| Halton/Sobol Sequences | Low-discrepancy sequences for uniform coverage | Systems requiring even sampling | More efficient than pure random |

| Perfect Lattice | Particles placed on ideal lattice points | Ordered, solid-state systems | May require significant perturbation |

| Perturbed Lattice | Perfect lattice with introduced disorder | General purpose, high coupling strength | Superior performance at high coupling [11] |

| Monte Carlo Pair Distribution | Uses pair distribution function for placement | High-accuracy requirements | Physics-informed, reduces equilibration time |

Table 2: Thermostat Protocol Comparison for Efficient Equilibration

The protocol for applying a thermostat during equilibration impacts temperature stability and the number of cycles required [11].

| Thermostating Protocol | Description | Key Finding | Recommendation |

|---|---|---|---|

| ON-OFF Duty Cycle | Thermostat is alternately applied and removed | Generally less efficient | Not recommended for most methods [11] |

| OFF-ON Duty Cycle | Simulation runs without thermostat first, then with | Superior performance | Outperforms ON-OFF for most initialization methods [11] |

| Weak Coupling | Using a larger coupling constant / longer interval | Requires fewer equilibration cycles | Preferable for faster equilibration [11] |

| Strong Coupling | Using a smaller coupling constant / shorter interval | Requires more cycles | Useful for tight control but slower |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Tool / Material | Function in Equilibrium Analysis |

|---|---|

| RED Python Package | Provides robust, automated algorithms for detecting the equilibration truncation point in time-series data [10]. |

| Smooth Overlap of Atomic Positions (SOAP) Descriptors | Machine-learning feature that quantitatively represents the local atomic environment; can be used to analyze structural convergence [12]. |

| Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs) | Neural networks trained to respect physical laws (e.g., charge neutrality); can be used as surrogates to accelerate property estimation [12]. |

| Adaptive Equilibration Framework | A systematic approach using initialization methods and uncertainty quantification to transform equilibration from a heuristic to a quantifiable procedure [11]. |

Why Common Metrics Like Density and Energy Can Be Misleading

Troubleshooting Guide: Identifying and Resolving Convergence Issues in MD Simulations

FAQ 1: Why can a simulation appear equilibrated based on energy yet still not be converged?

Issue: A simulation shows stable total energy and density, suggesting equilibrium, but key structural or dynamic properties of the biomolecule continue to drift. Explanation: Common metrics like total energy and system density are global properties that often stabilize quickly because they are dominated by the solvent (e.g., water). In large simulation systems, the contribution from the solute (e.g., a protein) is minimal in comparison. Therefore, these global metrics can reach a plateau even while the biomolecule itself is still relaxing and has not sampled its equilibrium conformational space [1]. Solution:

- Monitor Protein-Specific Metrics: Always track properties specific to your protein's structure, such as the Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) of the protein backbone or the radius of gyration.

- Define a Convergence Time: For each property of interest, calculate its running average over time. Consider the property "equilibrated" only when the fluctuations of this running average remain small for a significant portion of the trajectory after a convergence time, ( t_c ) [1].

- Extend Simulation Time: If protein-specific metrics have not stabilized, the simulation likely requires more time to escape local energy minima.

FAQ 2: How can I systematically check if my Free Energy Surface (FES) is converged?

Issue: It is difficult to determine if a calculated Free Energy Surface from an enhanced sampling simulation (like metadynamics) is reliable. Explanation: The FES depends on thorough sampling of all relevant regions of the collective variable (CV) space, including low-probability states. A simulation might sample a metastable state well, making the local FES seem stable, while missing other important states, leading to an unconverged global FES [13]. Solution: Use the Mean Force Integration (MFI) framework to compute a convergence metric.

- Protocol: Run multiple independent, asynchronous biased simulations (e.g., using metadynamics or umbrella sampling) [13].

- Analysis: Use the

pyMFIPython library to combine the data from all independent replicas and estimate the local and global convergence of the mean force across the CV space. This directly identifies regions that require more sampling [13]. - Refinement: Initiate new simulations that specifically target the poorly converged regions of the CV space to systematically improve the FES estimate.

FAQ 3: What is a more reliable approach than relying on a single simulation?

Issue: Conclusions drawn from a single, possibly too-short, Molecular Dynamics trajectory may not be reproducible. Explanation: Biomolecular systems are characterized by multiple metastable states separated by high free-energy barriers. A single simulation might be trapped in one state, failing to represent the true equilibrium distribution [1] [13]. Solution: Adopt a multi-replica simulation strategy.

- Protocol: Launch several independent simulations starting from different initial conditions (e.g., different velocities, or different conformations) [13].

- Analysis: Compare the properties of interest across all replicas. If they yield consistent results, confidence in convergence is high. For FES calculations, combine the data from all replicas using the MFI method, which is designed for this purpose and provides a more robust estimate than any single replica [13].

Quantitative Data on Metric Convergence

Table 1: Comparison of Common Metrics and Their Limitations in Assessing Convergence [1].

| Metric | Typical Convergence Time | Limitations | Recommended Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Energy | Fast (ps-ns) | Dominated by solvent; insensitive to solute conformation. | Quick check for system stability. Not sufficient for biomolecular equilibrium. |

| Density | Fast (ps-ns) | A global property that stabilizes once the box is equilibrated. | Useful for validating simulation setup (e.g., NPT ensemble). |

| Protein RMSD | Slow (ns-µs and beyond) | Can plateau in local minima; does not guarantee global equilibrium. | Essential for monitoring solute relaxation. Track alongside other metrics. |

| Free Energy Surface (FES) | Very Slow (µs-ms and beyond) | Requires exhaustive sampling of all states, including rare events. | The gold standard for thermodynamics. Assess convergence with multi-replica methods [13]. |

Experimental Protocol: Multi-Replica FES Convergence Analysis

This protocol details the methodology for assessing Free Energy Surface convergence using the Mean Force Integration (MFI) approach, as derived from recent research [13].

1. Simulation Setup:

- System Preparation: Prepare your molecular system (e.g., solvated protein) using standard tools (e.g., GROMACS [14]).

- Collective Variables (CVs): Select a low-dimensional set of CVs (dimensionality ≤3) that describe the process of interest (e.g., dihedral angles, distances).

2. Running Independent Replicas:

- Initialization: Launch multiple (M) independent simulation replicas. These can use different biasing protocols (e.g., metadynamics, umbrella sampling) or the same protocol with different random seeds for initial velocities [13].

- Execution: Run each simulation asynchronously, recording the trajectories, the time-dependent bias potential (for metadynamics), and the sampled configurations.

3. Mean Force Integration and Analysis:

- Data Combination: Use the

pyMFIlibrary to process the data from all M replicas. The library calculates the unbiased average mean force, ( \langle -\nablas F(s) \rangle ), by combining the mean forces from each replica, ( \langle dF(s)/ds \ranglej ), weighted by their biased probability density, ( p_j^b(s) ) [13]:

- Convergence Estimation: The

pyMFIlibrary provides a metric to estimate local and global convergence of the mean force across the CV space. This metric can be computed on-the-fly. - FES Calculation: Numerically integrate the combined average mean force to obtain the final estimate of the Free Energy Surface, ( F(s) ).

4. Iterative Refinement:

- Identify regions in the CV space where the convergence metric indicates poor sampling.

- Initiate new simulation replicas that specifically target these under-sampled regions to systematically improve the FES estimate.

Workflow Diagram: Multi-Replica Convergence Analysis

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Robust MD Research

Table 2: Key Software and Methodological "Reagents" for Convergence Analysis.

| Tool / Method | Function | Application in Convergence |

|---|---|---|

| GROMACS [14] | A high-performance molecular dynamics simulator. | The primary engine for running MD simulations, including energy minimization, equilibration, and production runs. |

| Mean Force Integration (MFI) [13] | A mathematical framework for combining data from multiple biased simulations. | Enables the calculation of a single, consistent FES from asynchronous, independent replicas, bypassing the need for alignment constants. |

| pyMFI Library [13] | An open-source Python library implementing the MFI formalism. | The primary tool for calculating the combined mean force, estimating FES convergence, and identifying under-sampled regions. |

| Multi-Replica Strategy [1] [13] | A simulation approach using multiple independent runs. | Provides a statistical basis for assessing the reliability and reproducibility of calculated properties, crucial for verifying convergence. |

| Collective Variables (CVs) [13] | Low-dimensional descriptors of a process (e.g., distances, angles). | Defines the reaction coordinate space on which the FES is calculated and convergence is assessed. Must be chosen carefully. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What does it mean for an MD simulation to be "at equilibrium"? A system is considered to be in a state of thermodynamic equilibrium when its properties no longer exhibit a net change over time and fluctuate around a stable average value. In practical terms for MD, a property ( Ai ) is considered "equilibrated" if the fluctuations of its running average ( \langle Ai \rangle(t) ) remain small after a certain convergence time ( t_c ) [1].

FAQ 2: Why is relying only on RMSD to determine equilibrium considered unreliable? Visual inspection of Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) plots is a subjective method. Studies have shown that when different scientists are presented with the same RMSD plots, there is no mutual consensus on when equilibrium is reached. Their decisions can be significantly biased by factors like the plot's color and y-axis scaling [15]. RMSD may plateau while other properties have not yet converged.

FAQ 3: My system's energy and density stabilized quickly. Can I trust that it is fully equilibrated? Not necessarily. While energy and density often converge rapidly in the initial stages of a simulation, this is insufficient to demonstrate the system's full equilibrium [2]. Other properties, particularly those related to specific molecular interactions or radial distribution functions (RDF), can take significantly longer to stabilize. True equilibrium requires that all properties of interest have converged.

FAQ 4: How do the choices of thermostat and barostat affect my simulation's convergence? The choice of algorithm for temperature and pressure control can influence both the path to equilibrium and the quality of the sampled ensemble.

- Thermostats: The Nosé-Hoover thermostat generally provides a reliable canonical ensemble. The Berendsen thermostat is robust for equilibration but does not reproduce the exact correct ensemble and should be avoided for production runs. The Langevin thermostat tightly controls temperature but can suppress natural dynamics, making it less suitable for calculating dynamical properties [16].

- Barostats: Similar to thermostats, the Berendsen barostat does not sample the correct isothermal-isobaric ensemble. For production NPT simulations, stochastic methods like the Bernetti-Bussi barostat are recommended, especially for small unit cells [16].

FAQ 5: What is the difference between a system being "equilibrated" and a property being "converged"? These terms are closely related but offer a useful distinction. A specific property (e.g., a distance between two protein domains) is converged when its average value becomes stable. The entire system can be considered equilibrated once all individual properties of interest have reached their converged state. A system can be in a state of partial equilibrium, where some properties are converged while others, especially those dependent on infrequent transitions, are not [1].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Key Properties Fail to Converge Within the Simulation Time

Problem Properties critical to your biological or chemical interpretation, such as Radial Distribution Function (RDF) peaks or radius of gyration, do not reach a stable average, even when basic thermodynamic properties like energy appear stable.

Solution

- Extend Simulation Time: This is the most direct solution. Some molecular processes, especially those involving large-scale conformational changes or slow relaxation of bulky molecules like asphaltenes, require multi-microsecond or longer simulations to observe convergence [1] [2].

- Increase Temperature: Raising the simulation temperature can accelerate molecular motion and help the system overcome energy barriers more quickly, thus speeding up convergence. However, ensure the temperature remains within a physiologically or physically relevant range for your study [2].

- Verify Initial Configuration: Ensure your initial model does not have extreme local energy concentrations. Proper energy minimization and low-density initial placement of molecules can prevent prolonged relaxation times [2].

Issue 2: Unreliable Determination of Equilibrium Onset

Problem It is unclear when the equilibration phase ends and the production phase begins, leading to the risk of analyzing non-equilibrated data.

Solution

- Monitor Multiple Properties: Do not rely on a single metric. Simultaneously monitor several properties, including potential energy, pressure, and system-specific metrics like RDFs or RMSD. Equilibrium is best indicated by the collective stabilization of all these properties [2].

- Discard Adequate Equilibration Data: Once you have identified the time ( tc ) at which all key properties have stabilized, discard all trajectory data from the period ( 0 ) to ( tc ). Only use the data from ( t_c ) to the end of your simulation (the production trajectory) for analysis [1] [16].

- Use Robust Property Definitions: Be aware that properties like free energy and entropy, which depend on a complete exploration of the conformational space including low-probability regions, are much more difficult to converge than simple averages and may never be fully converged in a finite simulation [1].

Issue 3: Energy Drift or Instability in Long Simulations

Problem The total energy of the system shows a consistent drift instead of fluctuating around a stable average, which is particularly critical for NVE simulations.

Solution

- Check Time Step Size: A time step that is too large can introduce errors in the numerical integration of the equations of motion, causing energy drift. For systems with light atoms (e.g., hydrogen), a time step of 1 fs is a safe starting point. The conservation of total energy in an NVE simulation should be used to assess the appropriateness of the time step [16].

- Review Pair List Buffering: Inefficient neighbor searching can cause energy drift. Use a Verlet buffer with a pair-list cut-off slightly larger than the interaction cut-off. Some software, like GROMACS, can automatically determine the buffer size based on a tolerated energy drift [14].

- Control Numerical Precision: Be aware that in single precision, constraints can cause a small but non-negligible energy drift. Adjust the tolerance of energy-drift checks accordingly [14].

Quantitative Data on Convergence

The table below summarizes the convergence behavior of different properties as observed in MD studies, highlighting that convergence is not uniform.

Table 1: Comparison of Convergence Behavior for Different MD Properties

| Property | Typical Convergence Time Scale | Key Characteristics & Pitfalls | System Studied |

|---|---|---|---|

| Energy & Density | Rapid (initial stage) | Fast convergence is necessary but not sufficient to prove full system equilibrium [2]. | Asphalt Models [2] |

| Pressure | Longer than energy/density | Requires more time to stabilize and may fluctuate significantly during the equilibration phase [2]. | Asphalt Models [2] |

| RMSD | Varies | A "plateau" is subjectively and unreliably identified; should not be used as the sole criterion [15]. | General Biomolecules [15] |

| RDF (Aromatics, Resins) | Relatively fast | Convergence indicates local structural equilibrium for these components [2]. | Asphalt Models [2] |

| RDF (Asphaltene-Asphaltene) | Slowest (Microseconds) | The slow convergence of these interactions is a fundamental factor controlling the overall system equilibrium [2]. | Asphalt Models [2] |

| Transition Rates | Very slow (>> microseconds) | Probing transitions to low-probability conformations requires thorough exploration of conformational space, which is time-consuming [1]. | General Biomolecules [1] |

Experimental Protocol for Testing System Equilibrium

This protocol provides a step-by-step methodology to systematically test whether an MD simulation has reached equilibrium, moving beyond the sole use of energy and RMSD.

1. Define and Calculate Multiple Metrics

- Action: Select a set of properties that are relevant to your research question. This set should always include:

- Global Thermodynamic Properties: Total energy, potential energy, density, pressure.

- System-Specific Structural Properties: Radial Distribution Functions (RDF) between key molecular components, radius of gyration (for polymers), solvent accessible surface area (for proteins), or specific interatomic distances.

- Rationale: Relying on a single metric is unreliable. Different properties report on different aspects of the system's state and converge on different timescales [2] [15].

2. Conduct a Long Validation Simulation

- Action: Perform a single, long simulation trajectory (e.g., multi-microsecond for biomolecular systems) starting from an energy-minimized and thermally pre-equilibrated structure.

- Rationale: A long trajectory is required to observe if and when properties stabilize. Short simulations may only capture local relaxations, not global equilibrium [1].

3. Analyze Running Averages

- Action: For each property defined in Step 1, calculate its running average from the beginning of the trajectory to time ( t ). Plot these running averages as a function of simulation time ( t ).

- Rationale: The running average smooths out instantaneous fluctuations. A property is considered converged when its running average plateaus and shows only small fluctuations around a stable value [1].

4. Identify the Convergence Point

- Action: Visually inspect the running average plots to identify the time ( tc ) after which all properties of interest remain stable. The data before ( tc ) is the equilibration phase; the data after ( t_c ) is the production trajectory used for analysis.

- Rationale: This provides an objective (though still approximate) criterion for deciding how much of the initial trajectory to discard [1].

Diagram: Workflow for Testing Equilibrium in an MD Simulation

Research Reagent Solutions

This table lists key computational "reagents" and methodological choices that are essential for conducting reliable MD simulations and assessing their convergence.

Table 2: Essential Tools and Methods for Convergence Analysis

| Item / Method | Function / Purpose | Considerations for Convergence |

|---|---|---|

| Multiple Property Monitoring | To avoid false positives of equilibrium by tracking several system descriptors. | Using only energy/RMSD is insufficient. Must include system-specific metrics like RDFs [2]. |

| Long-Timescale Simulations (µs-ms) | To provide sufficient time for slow conformational relaxations and infrequent transitions to occur. | Many biologically relevant properties require multi-microsecond trajectories to converge [1]. |

| Robust Thermostat (e.g., Nosé-Hoover) | To correctly maintain the canonical (NVT) ensemble during the simulation. | Avoids ensemble artifacts that can be introduced by simpler algorithms like Berendsen in production runs [16]. |

| Robust Barostat (e.g., Bernetti-Bussi) | To correctly maintain the isothermal-isobaric (NPT) ensemble. | Essential for accurate sampling of density; stochastic barostats are recommended over Berendsen for production [16]. |

| Running Average Analysis | To objectively identify the point in time when a property's average becomes stable. | Helps define the equilibration phase (data to discard) and the production phase (data to analyze) [1]. |

| Radial Distribution Function (RDF) | To quantify the average microscopic structure and molecular packing in the system. | Convergence of key RDF peaks (e.g., asphaltene-asphaltene) can be a critical marker for true system equilibrium [2]. |

Physical and Biological Implications of Non-Equilibrium Systems

Welcome to the NEMD Technical Support Center

This resource is designed for researchers investigating thermodynamic properties in biological and materials systems using Non-Equilibrium Molecular Dynamics (NEMD). Here you will find practical guides to improve the convergence and reliability of your simulations, framed within the context of a broader thesis on advancing thermodynamic convergence in MD research.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: Why do my calculated transport properties, like ionic conductivity, fail to converge in NEMD simulations? Convergence issues often stem from neglecting ion-ion distinct correlations, which are significant in systems with high carrier density like solid electrolytes. The Nernst-Einstein approximation ignores these cross-correlation terms (∑σ_distinct), leading to poor convergence and an inaccurate baseline. The Chemical Color-Diffusion NEMD (CCD-NEMD) method, which assigns color charges based on chemical valency, includes these correlations and can achieve convergence with smaller statistical errors than conventional equilibrium MD [17].

FAQ 2: How can I reliably restart a long NEMD simulation that was interrupted?

To ensure a continuous restart, always use the checkpoint file (.cpt) written by your MD engine (e.g., gmx mdrun). This file contains full-precision coordinates and velocities, along with the state of coupling algorithms. Use a command like gmx mdrun -cpi state.cpt. Avoid restarting from less precise formats like .gro files with velocities, as this leads to a less continuous restart and potential trajectory divergence [18].

FAQ 3: What are the primary sources of non-reproducibility in NEMD trajectories, and how can I control them? MD is a chaotic system, and trajectories will diverge even with minimal changes. Factors causing non-reproducibility include [18]:

- Hardware/Software: Different processor types, number of cores, or optimization levels during compilation.

- Algorithms: Dynamic load balancing or the use of GPUs, which have non-deterministic force summation.

While individual trajectories are not reproducible, thermodynamic observables should converge. For strict trajectory reproducibility (e.g., for debugging), use the

-reprodflag ingmx mdrunand ensure identical hardware, software, and input files [18].

FAQ 4: My simulation failed with an "Out of memory" error. What steps should I take? This error occurs when the system cannot allocate required memory [19].

- Immediate fixes: Reduce the number of atoms selected for analysis or the length of the trajectory file being processed.

- Check for errors: Ensure your initial system setup (e.g., box size) is correct. Confusion between Ångström and nm can create a system 10^3 times larger than intended [19].

- Long-term solution: Use a computer with more RAM or scale your simulation to a high-performance computing (HPC) resource.

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Addressing Poor Convergence in Thermal Conductivity Calculations

Symptoms: The calculated thermal conductivity value fluctuates significantly with simulation time and does not settle to a stable value. This is a known issue in 2D systems where autocorrelation functions decay very slowly [20].

Diagnosis and Solutions:

| Troubleshooting Step | Action | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Method Selection | Use the NEMD method over the Green-Kubo (EMD) approach. NEMD creates a direct heat flux, overcoming slow convergence of autocorrelation functions. | [20] |

| Convergence Testing | Perform a detailed convergence study with respect to key simulation parameters, such as system size and simulation time, especially when external fields (e.g., magnetic) are present. | [20] |

| Advanced Potentials | Employ machine-learning potentials. They offer high accuracy and adaptability, improving the fidelity of calculated properties like thermal conductivity. | [21] |

Guide 2: Resolving "Atom not found in residue topology database" Error

Symptom: The pre-processing tool pdb2gmx fails with an error that a residue is not found in the topology database [19].

Diagnosis: The force field you selected does not contain a topology entry for the residue/molecule in your coordinate file.

Solution Pathway:

Explanation:

- Name Mismatch: The residue name in your PDB file (e.g., "HIS") must exactly match the entry in the force field's database. Rename if necessary [19].

- New Residue: If the molecule is not standard, you cannot use

pdb2gmxdirectly. You must [19]:- Find Parameters: Search the literature for existing parameters compatible with your force field.

- Create Topology: Manually create an

.itptopology file for the molecule. - Include File: Add the

.itpfile to your main topology (.top) using an#includestatement.

- Change Force Field: A different force field might have the residue parameters you need.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Calculating Ion-Ion Correlated Conductivity with CCD-NEMD

This protocol details the use of Chemical Color-Diffusion NEMD to compute ionic conductivity beyond the Nernst-Einstein approximation, crucial for accurate simulation of solid electrolytes [17].

1. Principle CCD-NEMD applies a fictitious "color field" ( F_e ) to particles based on their chemical charge valency (e.g., Li⁺ = +1, PS₄³⁻ = -3). This induces a steady flux, from which the full conductivity (including distinct ion-ion correlations) can be derived via linear response theory [17].

2. Workflow

3. Step-by-Step Methodology

- Step 1: System Preparation

- Construct an atomistic model of the solid electrolyte (e.g., Li₁₀GeP₂S₁₂ or Li₇La₃Zr₂O₁₂).

- Use ab initio calculations to derive a reference potential or employ a machine-learning potential for force calculations [17].

- Step 2: Color Charge Assignment

- Assign color charge ( ci ) to each atom equal to its formal charge valency ( zi ) (e.g., ( c{i \in \text{Li}} = +1 ), ( \sum{i \in \text{PS}4} ci = -3 )).

- Critically, ensure the total system is color-charge neutral: ( \sum c_i = 0 ) for momentum conservation [17].

- Step 3: NEMD Simulation

- Apply a constant color field ( F_e ) along the desired axis (z-axis).

- Integrate the modified equations of motion [17]: ( \dot{\mathbf{q}}i = \frac{\mathbf{p}i}{mi} ) ( \dot{\mathbf{p}}i = \mathbf{F}i + ci Fe \mathbf{\hat{z}} - \alpha \mathbf{p}{i, (x,y)} ) (Note: Thermostat (α) is often applied only to directions perpendicular to the field to avoid biasing the driven flux).

- Allow the system to reach a non-equilibrium steady state.

- Step 4: Analysis and Convergence

- Measure the steady-state color charge flux ( J_z ).

- Calculate the ionic conductivity using the linear response relation: ( \sigma = \frac{Jz}{Fe} ).

- Run the simulation for a sufficient duration and perform statistical averaging to ensure the value has converged. Compare the result with the Nernst-Einstein estimate to quantify the correlation effect.

Protocol 2: Computing Thermal Conductivity via NEMD for a 2D Yukawa System

This protocol outlines the NEMD method for determining thermal transport properties in complex systems like magnetized 2D Yukawa fluids, where EMD methods struggle with convergence [20].

1. Principle A heat flux ( Jq ) is imposed by coupling a "hot" and "cold" region of the simulation box to thermostats at different temperatures. The resulting temperature gradient ( \nabla T ) is measured, and thermal conductivity ( \lambda ) is calculated from Fourier's law: ( Jq = - \lambda \nabla T ) [20].

2. Workflow

3. Step-by-Step Methodology

- Step 1: System Setup

- Initialize N particles (e.g., 1600) in a 2D simulation box with periodic boundary conditions.

- Set the interparticle potential to the Yukawa form: ( \beta V(r) = \frac{\Gamma}{r} \exp(-\kappa r) ), where ( \Gamma ) is the coupling parameter and ( \kappa ) is the screening parameter [20].

- Step 2: Non-Equilibrium Drive

- Define two regions in the simulation box as "hot" and "cold" slabs.

- Couple these regions to thermostats at temperatures ( T + \Delta T ) and ( T - \Delta T ), respectively, to establish a heat flux.

- Step 3: Simulation with External Field

- To include a perpendicular magnetic field, integrate the equations of motion using a specialized algorithm like the Velocity Verlet for magnetic fields [20]: ( x(t+\Delta t) = x(t) + \frac{1}{\Omega}[vx(t)\sin(\Omega \Delta t) - vy(t)C(\Omega \Delta t)] + ... ) (where ( \Omega = \omegac / \omegap ) is the normalized cyclotron frequency).

- Step 4: Data Collection and Analysis

- Measure the heat flux ( Jq ) flowing from the hot to the cold region.

- Measure the steady-state temperature profile and compute the temperature gradient ( \nabla T ) in the central, non-thermostated region.

- Calculate the thermal conductivity as ( \lambda = - \frac{Jq}{\nabla T} ).

- Convergence Check: Systematically test for convergence with respect to simulation time, system size, and the magnitude of the applied temperature difference.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Category | Item / Solution | Function | Application Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| Software & Algorithms | CCD-NEMD Algorithm | Calculates correlated ionic conductivity by applying a color field based on chemical valency, going beyond the Nernst-Einstein limit. | Essential for simulating solid electrolytes (e.g., LGPS, LLZO) where ion-ion correlations significantly impact conductivity [17]. |

| Machine Learning Potentials (MLPs) | A deep learning potential fitted to DFT data provides high accuracy and adaptability for molecular dynamics simulations at a lower computational cost. | Used for studying complex materials like spinel oxides (AB₂O₄), enabling reliable calculation of thermal conductivity and expansion [21]. | |

| Transient-Time Correlation Function (TTCF) | A toolkit (e.g., TTCF4LAMMPS) enables NEMD studies of fluid behavior at experimentally accessible, low shear rates by leveraging correlation functions. | Crucial for measuring properties like viscosity in bulk or confined fluids under weak external fields [22]. | |

| Computational Techniques | Velocity Verlet with Magnetic Field | A numerical integrator that solves the equations of motion for charged particles in a homogeneous magnetic field, accounting for the Lorentz force. | Necessary for studying the effect of magnetic fields on transport properties in 2D Yukawa systems and plasmas [20]. |

Checkpointing (-cpt flag in GROMACS) |

Periodically writes a full-precision simulation state to a file, allowing for exact restarts after interruption. | Critical for managing long simulations on cluster systems. Ensures no computational resources are wasted [18]. |

Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulation is a powerful computational tool that provides atomic-level insights into biomolecular processes, complementing experimental findings [1]. However, a fundamental and often overlooked assumption in most MD studies is that the simulated trajectory is long enough for the system to have reached thermodynamic equilibrium, resulting in converged properties [1]. This assumption, if left unverified, can invalidate the results of a simulation. The core issue is that a system can be in a state of partial equilibrium, where some properties have converged while others, particularly those dependent on infrequent transitions to low-probability conformations, have not [1]. This guide addresses the theoretical underpinnings of this challenge and provides practical solutions for researchers to diagnose and improve convergence in their simulations.

Core Concepts: Statistical Mechanics of Equilibrium

The Link Between Microscopic States and Macroscopic Properties

Statistical mechanics connects the microscopic states of a system to its macroscopic thermodynamic properties. For an isolated system with constant number of particles (N), volume (V), and energy (E)—the microcanonical (NVE) ensemble—the entropy S is related to the number of accessible microstates (Ω) by Boltzmann's famous equation: S = k log Ω [23]. When a system of interest is in thermal equilibrium with a much larger heat bath, we consider the canonical (NVT) ensemble (constant N, V, and Temperature). Here, the physical properties are derived from the conformational partition function, Z [1] [24].

$$ Z = \int{\Omega} \exp\left(-\frac{E(\mathbf{r})}{kB T}\right) d\mathbf{r} $$

The partition function Z represents the volume of the available conformational space (Ω) weighted by the Boltzmann factor. The equilibrium value of a property A is then calculated as an ensemble average:

$$ \langle A \rangle = \frac{1}{Z} \int{\Omega} A(\mathbf{r}) \exp\left(-\frac{E(\mathbf{r})}{kB T}\right) d\mathbf{r} $$

Fundamental thermodynamic quantities like Helmholtz free energy (F) and entropy (S) depend directly on the partition function [1] [24]: $$ F = -kB T \ln(Z) \qquad S = -\left(\frac{\partial F}{\partial T}\right)V $$

Defining Convergence and Equilibrium in MD Simulations

In the context of finite-length MD simulations, a practical definition of equilibrium is necessary [1]:

"Given a system’s trajectory, with total time-length T, and a property A~i~ extracted from it, and calling ⟨A~i~⟩(t) the average of A~i~ calculated between times 0 and t, we will consider that property 'equilibrated' if the fluctuations of the function ⟨A~i~⟩(t), with respect to ⟨A~i~⟩(T), remain small for a significant portion of the trajectory after some 'convergence time', t~c~, such that 0 < t~c~ < T. If each individual property, A~1~, A~2~, ..., of the system is equilibrated, then we will consider the system to be fully equilibrated" [1].

This definition highlights that full convergence requires the exploration of all relevant regions of conformational space, including low-probability states. In practice, properties that are averages over high-probability regions (e.g., distances between protein domains) may converge relatively quickly, while properties that depend explicitly on low-probability regions (e.g., transition rates, free energies, and entropy) require much longer simulation times [1].

Fig. 1: Workflow for assessing property convergence in MD simulations.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting

Q1: My simulation's RMSD has reached a plateau. Does this mean the system is equilibrated and properties have converged? Not necessarily. A flat RMSD curve does not guarantee proper thermodynamic behaviour or confirm full convergence [25]. RMSD stability may indicate only that the system is trapped in a local energy minimum or that the overall fold is stable, while functionally important local dynamics or rare transitions remain unsampled. Always monitor multiple properties, including energy fluctuations, radius of gyration, hydrogen bond networks, and specific distances or angles relevant to your biological question [25].

Q2: How long should I simulate to reach convergence? There is no universal answer. Convergence time depends on the system size, complexity, and the specific property being measured [1]. Studies have shown that for some proteins, properties of biological interest can converge in multi-microsecond trajectories, while transition rates to low-probability conformations may require much longer [1]. The only robust approach is to perform convergence tests for each property of interest, as outlined in Section 4.

Q3: Can my system be partially equilibrated? Yes. This is a crucial concept. A system can be in partial equilibrium where some properties have reached their converged values while others have not [1]. This occurs because different properties depend on different regions of the conformational space. Average structural properties often converge faster than thermodynamic properties like free energy, which require adequate sampling of all regions, including low-probability ones [1].

Q4: What is the impact of insufficient sampling on free energy and entropy calculations? Free energy and entropy calculations are particularly sensitive to insufficient sampling [1] [23]. These properties depend explicitly on the partition function, which requires contributions from all accessible conformational states, including low-probability ones [1]. If your simulation misses these rare states, the calculated free energy and entropy will be incorrect. Enhanced sampling techniques are often necessary for reliable calculation of these properties.

Experimental Protocols for Assessing Convergence

Protocol: Testing for Property Convergence

Objective: To determine if a specific property A has converged during an MD trajectory. Theory: The running average of a property, ⟨A⟩(t), should fluctuate around a stable value after a convergence time t~c~ [1].

Methodology:

- Trajectory Preparation: Use a production trajectory of total length T. Ensure molecules are made whole and periodic boundary artifacts have been corrected [25].

- Calculate Property Time Series: Compute the property A(t) for every frame (or at regular intervals) throughout the trajectory.

- Compute Running Average: Calculate the running average ⟨A⟩(t) from time 0 to time t for all t ≤ T.

- Analyze Fluctuations: Visually inspect and quantitatively analyze the fluctuations of ⟨A⟩(t) for the latter portion of the trajectory (e.g., the second half). Convergence is suggested when these fluctuations are small and remain within an acceptable margin of the final average ⟨A⟩(T).

Objective: To determine if a system has been adequately equilibrated before production data collection. Theory: A system is considered equilibrated when key thermodynamic and structural properties have stabilized [25].

Methodology:

- Energy Minimization: Begin with energy minimization to remove steric clashes and high-energy distortions [25].

- Heating and Pressurization: Gradually heat the system to the target temperature and adjust the pressure to the target value.

- Unrestrained Equilibration: Run an unrestrained simulation while monitoring:

- Total energy and potential energy

- System temperature and pressure (density)

- Root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) of the biomolecule

- Plateau Identification: Continue equilibration until all monitored properties have reached a stable plateau, not just a single metric like RMSD [25].

Quantitative Data on Convergence Timescales

Table 1: Convergence Characteristics of Different Molecular Properties in MD Simulations

| Property Type | Examples | Convergence Timescale | Key Considerations | Statistical Mechanics Basis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Structural Averages | Inter-atomic distances, Radius of gyration, Secondary structure content | Relatively fast (nanoseconds to microseconds) | Depends mainly on high-probability regions of conformational space [1]. | Fast convergence as ⟨A⟩ is dominated by Boltzmann-weighted contributions from high-probability states [1]. |

| Dynamic Properties | RMS fluctuations (RMSF), Hydrogen bond lifetimes, Local flexibility | Variable (microseconds often required) | Requires sampling of relevant motional modes [1]. | Relies on accurate sampling of the variance and time-dependent correlations of motions. |

| Thermodynamic Properties | Free energy (ΔG), Entropy (S), Potential of Mean Force (PMF) | Very slow (microseconds to milliseconds) | Requires thorough exploration of all relevant states, including low-probability regions [1]. | Directly depends on the partition function Z, requiring integration over all conformational space [1] [23]. |

| Kinetic Properties | Transition rates, Conformational transition times, Binding/unbinding rates | Extremely slow (milliseconds and beyond) | Depends on sampling rare events across high energy barriers. | Requires observing the rare event multiple times to establish a statistically meaningful rate. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Computational Tools for Convergence Analysis

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function in Convergence Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| MD Simulation Engines | GROMACS [14], AMBER [25], NAMD [26] | Core software to perform the molecular dynamics simulations and generate trajectories. |

| Trajectory Analysis Suites | GROMACS analysis tools [25], cpptraj (AMBER) [25], MDAnalysis | Calculate properties like RMSD, RMSF, distances, hydrogen bonds, and running averages from trajectory data. |

| Force Fields | AMBER [26], CHARMM [26], GROMOS [26], OPLS [26] | Empirical potential energy functions that define the interactions between atoms. Choice of force field affects the accuracy of the simulated energy landscape [26]. |

| Enhanced Sampling Methods | Metadynamics, Replica Exchange MD (REMD) [27], Accelerated MD | Techniques designed to improve sampling of conformational space, especially for rare events, thus aiding the convergence of thermodynamic properties. |

| Visualization Software | VMD, PyMol, Chimera | Critical for visual validation of structural stability, identifying artifacts, and understanding the molecular basis of observed convergence behavior. |

Theoretical Framework Diagram

Fig. 2: Theoretical framework linking statistical mechanics, MD simulation, and convergence.

Practical Strategies and Protocols for Accelerating Convergence

FAQs: Addressing Common Equilibration Challenges

FAQ 1: How can I determine if my system has truly reached equilibrium before starting production simulation?

A system can be considered to have reached a state of "partial equilibrium" when the fluctuations of the time-averaged values for key properties remain small for a significant portion of the trajectory after a convergence time, tc. It is critical to monitor multiple properties, as some may converge faster than others. Properties with the most biological interest often converge in multi-microsecond trajectories, while others, like transition rates to low-probability conformations, may require more time [1].

FAQ 2: What are the consequences of starting production runs from a non-equilibrated system?

Simulating from a non-equilibrated state can invalidate the results, as the measured properties will not be reliable predictors of equilibrium properties. The resulting trajectory may not represent the correct thermodynamic ensemble, rendering quantitative predictions meaningless. This is a profound yet often overlooked assumption in many MD studies [1].

FAQ 3: Are standard metrics like stable RMSD and energy sufficient to confirm equilibration?

Not always. While energy and Root-Mean-Square Deviation (RMSD) plateaus are standard and useful checks, they can be misleading. Studies have shown clear evidence of phase separation in systems like hydrated xylan oligomers even while standard metrics like density and energy remained constant. It is essential to use a set of parameters that probe the structural and dynamical heterogeneity of the system [28].

FAQ 4: What are the typical timescales required for equilibration?

Equilibration times are system-dependent. For simple, small systems like dialanine, equilibrium might be reached quickly. For more complex biomolecular systems, convergence of key properties often requires simulation times on the order of microseconds [1] [28]. Very large conformational changes can require even longer, up to milliseconds or more [29].

FAQ 5: Why is the initial energy minimization step critical?

Energy minimization relieves severe steric clashes and high-energy distortions in the initial structure (e.g., from an experimental crystal structure). Starting a dynamics simulation from a high-energy state can lead to numerical instability and unphysical forces, which can crash the simulation or drive the system along an unrealistic path [29].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Continuous Drift in Properties

- Problem: Key properties, such as potential energy or radius of gyration, show a steady drift instead of fluctuating around a stable average.

- Diagnosis: The system has not reached equilibrium. The initial structure may be far from the minimum energy configuration for the simulation conditions (e.g., solvated state vs. crystal environment).

- Solution:

- Extend the equilibration phase.

- Re-examine the initial structure preparation protocol, ensuring solvent and ions are properly equilibrated around the solute.

- Verify that the system's temperature and pressure coupling algorithms are correctly configured and have stabilized.

Issue 2: Misleading Stability from Simple Metrics

- Problem: Energy and density appear stable, but other structural or dynamic properties are still evolving.

- Diagnosis: The system may be trapped in a local energy minimum or undergoing slow reorganization not captured by basic metrics [28].

- Solution:

- Monitor a wider set of properties, such as:

- Structural: Solvent Accessible Surface Area (SASA), intramolecular distances, dihedral angle distributions.

- Dynamic: Mean-Square Displacement (MSD) of water and polymer, autocorrelation functions of key motions [1].

- Perform multiple independent simulations starting from different initial configurations to better sample the phase space.

- Monitor a wider set of properties, such as:

Issue 3: Inadequate Sampling of Low-Probability States

- Problem: Average structural properties are stable, but calculations of free energy or transition rates are unreliable.

- Diagnosis: The simulation has not sufficiently sampled low-probability regions of the conformational space, which are critical for these properties [1].

- Solution:

- Dramatically extend the simulation time.

- Employ enhanced sampling techniques (e.g., metadynamics, umbrella sampling).

- Use multiple replicates with different initial velocities.

Quantitative Data on Convergence

Table 1: Documented Equilibration Timescales from MD Studies

| System | System Size & Description | Key Properties Monitored | Observed Equilibration Time | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrated Amorphous Xylan | Oligomers at different hydration levels | Structural & dynamical heterogeneity, phase separation | ~1 microsecond | [28] |

| General Biomolecules | Several proteins of varying size | Structural, dynamical, and cumulative properties | Multi-microseconds to milliseconds | [1] [29] |

Table 2: Checklist for Equilibration Protocol and Property Monitoring

| Stage | Key Actions | Properties to Monitor |

|---|---|---|

| Energy Minimization | Relieve steric clashes; prepare for dynamics. | Potential energy, maximum force. |

| Heating/Pressurization | Gradually heat to target temperature; apply pressure coupling. | Temperature, pressure, density, potential energy. |

| Equilibration (NVT/NPT) | Run unrestrained simulation to relax the system. | Primary: Density, total energy, RMSD.Secondary: Rg, SASA, specific distances/angles.Advanced: MSD, ACFs. |

| Convergence Check | Confirm properties fluctuate around a stable average. | Fluctuations of time-averaged 〈A〉(t) for all key properties [1]. |

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Detailed Equilibration Protocol

Energy Minimization:

- Methodology: Use a steepest descent algorithm for the first 1,000-5,000 steps to efficiently handle large forces, followed by a conjugate gradient method for finer convergence.

- Success Criteria: The potential energy and the maximum force on any atom should converge to a stable minimum value.

Solvent and Ion Equilibration:

- Methodology: With the solute (e.g., protein) heavy atoms harmonically restrained, run a short simulation (e.g., 100-500 ps). This allows solvent and ions to relax and diffuse around the fixed solute.

- Success Criteria: System density and solvent energy stabilize.

Full System Equilibration:

- Methodology: Remove all restraints and run an unrestrained simulation in the NPT ensemble. The required time is system-dependent and must be determined by monitoring convergence.

- Success Criteria: As defined in Table 2. The simulation should be extended until all properties deemed critical for the study have reached a state of partial equilibrium [1].

Workflow Diagram

MD Equilibration Workflow

Property Monitoring Logic

Convergence Check Logic

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key "Research Reagent Solutions" for MD Setup

| Item / Component | Function / Role in Setup and Equilibration |

|---|---|

| Classical Force Fields | An empirical potential energy function with fitted parameters; calculates non-bonded and bonded interactions, determining the system's dynamics and properties [29]. |

| Water Model | A molecular model (e.g., TIP3P, SPC/E) representing water molecules, often treated as rigid bodies to allow for larger integration timesteps [29]. |

| Ions | Added to the solvent to neutralize the system's net charge and mimic experimental salt concentrations (e.g., 150 mM NaCl). |

| Thermostat | An algorithm (e.g., Nosé-Hoover, Berendsen) that regulates the system's temperature by scaling velocities, mimicking a thermal bath [29]. |

| Barostat | An algorithm (e.g., Parrinello-Rahman, Berendsen) that controls the system's pressure by adjusting the simulation box dimensions [29]. |

| Holonomic Constraints | Applied to freeze the fastest vibrational degrees of freedom (e.g., bond vibrations involving hydrogen atoms) using algorithms like LINCS or SHAKE, enabling a larger integration timestep [29]. |

| Numerical Integrator | An algorithm (e.g., Leap-frog Verlet) that solves Newton's equations of motion to propagate the system forward in time [29]. |

Advanced Sampling Techniques for Enhanced Phase Space Exploration

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why are my molecular dynamics (MD) simulations failing to converge for thermodynamic properties, even when energy and density appear stable?

Convergence issues often arise from incomplete sampling of phase space, particularly when high energy barriers separate metastable states. While global indicators like system density and total energy may stabilize quickly, they do not guarantee that the system has reached true thermodynamic equilibrium. Key collective variables (CVs) or intermolecular interactions may converge over much longer timescales [2]. For instance, in complex systems like asphalt, the radial distribution function (RDF) for specific components (e.g., asphaltene-asphaltene) can take significantly longer to converge than the system density [2]. Furthermore, the chosen enhanced sampling method may be inefficient if the collective variables do not adequately describe the reaction coordinate of the process being studied [30] [31].

Q2: What are collective variables (CVs), and how do I select good ones for my enhanced sampling simulation?

Collective Variables (CVs) are low-dimensional, differentiable functions of the system's atomic coordinates (e.g., distances, angles, dihedral angles, or coordination numbers) that are designed to describe the slowest degrees of freedom and the progress of a rare event [30] [31]. The free energy surface (FES) is typically expressed as a function of these CVs. Selecting good CVs is critical. They should:

- Discriminate between states: Clearly distinguish all relevant metastable states.

- Describe the mechanism: Include all slow degrees of freedom relevant to the transition.

- Be computationally efficient: Not be overly expensive to calculate at every simulation step. Poor CVs that omit a key reaction coordinate will lead to inadequate sampling and non-convergent free energy estimates [30].

Q3: My simulation is trapped in a local free energy minimum. What advanced sampling techniques can help it escape?

Several advanced sampling methods are designed to address this exact problem by applying a bias potential to encourage exploration.

- Metadynamics: This method adds a repulsive Gaussian bias to the CVs at the current location, which "fills up" the visited free energy minima and allows the system to escape to new regions [31].

- Temperature Accelerated MD (TAMD): TAMD introduces an extended system where the CVs are coupled to the physical system and evolved at a higher artificial temperature. This allows the CVs to explore their space more rapidly, effectively pulling the physical system over energy barriers [30].

- Adaptive Biasing Force (ABF): ABF directly applies a bias to counteract the mean force along the CVs, leading to a uniform sampling along the CV and efficient barrier crossing [31].

- Umbrella Sampling: This technique uses a series of harmonic biases to restrain the simulation to specific windows along a CV. The data from all windows are then combined to reconstruct the full free energy profile [31].

Q4: How can I leverage machine learning and modern software to improve my sampling workflows?

Modern software libraries seamlessly integrate machine learning (ML) with enhanced sampling, offering powerful new approaches.

- ML-Augmented Sampling: Methods like Artificial Neural Network Sampling or Adaptive Biasing Force using neural networks use ML models to approximate the free energy surface and its gradients on-the-fly, which can accelerate convergence [31].

- Automated Free-Energy Reconstruction: Frameworks exist that use Gaussian Process Regression (GPR) to reconstruct the free-energy surface from MD data, propagating statistical uncertainties and often incorporating active learning to optimize where to sample next [9].

- High-Performance Software: Libraries like PySAGES provide a unified platform that offers a wide array of enhanced sampling methods, supports GPU acceleration for performance, and integrates with popular MD engines like HOOMD-blue, OpenMM, and LAMMPS [31].

Troubleshooting Guides

Diagnosis Flowchart for Sampling Problems

The following diagram outlines a logical workflow for diagnosing common sampling issues.

Common Error Messages and Resolutions

The table below summarizes specific problems, their potential diagnostic messages, and recommended solutions.

Table 1: Troubleshooting Common Sampling and Convergence Issues

| Problem Category | Example Symptoms / Messages | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Inadequate Sampling Time | RDF curves show multiple irregular peaks and are not smooth; Pressure has not equilibrated [2]. | Extend simulation time far beyond energy/density stabilization; Use enhanced sampling to overcome barriers [2]. |

| Poor Collective Variable (CV) Choice | Simulation transitions but not along the desired pathway; Free energy surface appears flat or featureless [30]. | Identify CVs that better describe the reaction coordinate; Use dimensionality reduction or ML techniques to find relevant slow modes [31]. |

| Inefficient Enhanced Sampling | Method (e.g., Metadynamics) is slow to converge; Bias potential grows without facilitating new transitions. | Increase the bias deposition frequency or rate; Combine with a higher temperature for CVs (TAMD) [30]; Try a different method like ABF [31]. |

| Parameter Sensitivity | Results are highly sensitive to the force constant in umbrella sampling or the Gaussian width in metadynamics. | Perform a sensitivity analysis; Use multiple walkers or replicas to improve statistics and robustness [31] [9]. |

Step-by-Step Protocol: Temperature Accelerated Molecular Dynamics (TAMD)

TAMD is an extended phase-space method designed to efficiently explore free energy surfaces [30].

1. Principle: A set of auxiliary variables ( \mathbf{z} ), corresponding to the CVs ( \boldsymbol{\theta}(\mathbf{x}) ), is evolved concurrently with the physical atomic coordinates ( \mathbf{x} ). The key is that the ( \mathbf{z} ) variables are thermostatted at a higher artificial temperature ( \bar{T} ) than the physical system ( T ) (( \bar{T} > T )). This causes the CVs to explore their landscape more rapidly, effectively pulling the physical system over high energy barriers [30].

2. Equations of Motion: The system evolves under the following coupled equations [30]: [ \begin{align} m_i \ddot{\mathbf{x}}_i &= -\frac{\partial V(\mathbf{x})}{\partial \mathbf{x}_i} - \kappa \sum_{\alpha} (\theta_\alpha(\mathbf{x}) - z_\alpha) \frac{\partial \theta_\alpha(\mathbf{x})}{\partial \mathbf{x}_i} + \text{thermostat at } T \ \mu_\alpha \ddot{z}_\alpha &= \kappa (\theta_\alpha(\mathbf{x}) - z_\alpha) + \text{thermostat at } \bar{T} \end{align} ] Here, ( \kappa ) is a coupling constant, and ( \mu_\alpha ) are the artificial masses of the auxiliary variables.

3. Workflow:

4. Key Parameters: