Ab Initio vs. Classical MD: A Comprehensive Guide for Computational Drug Discovery

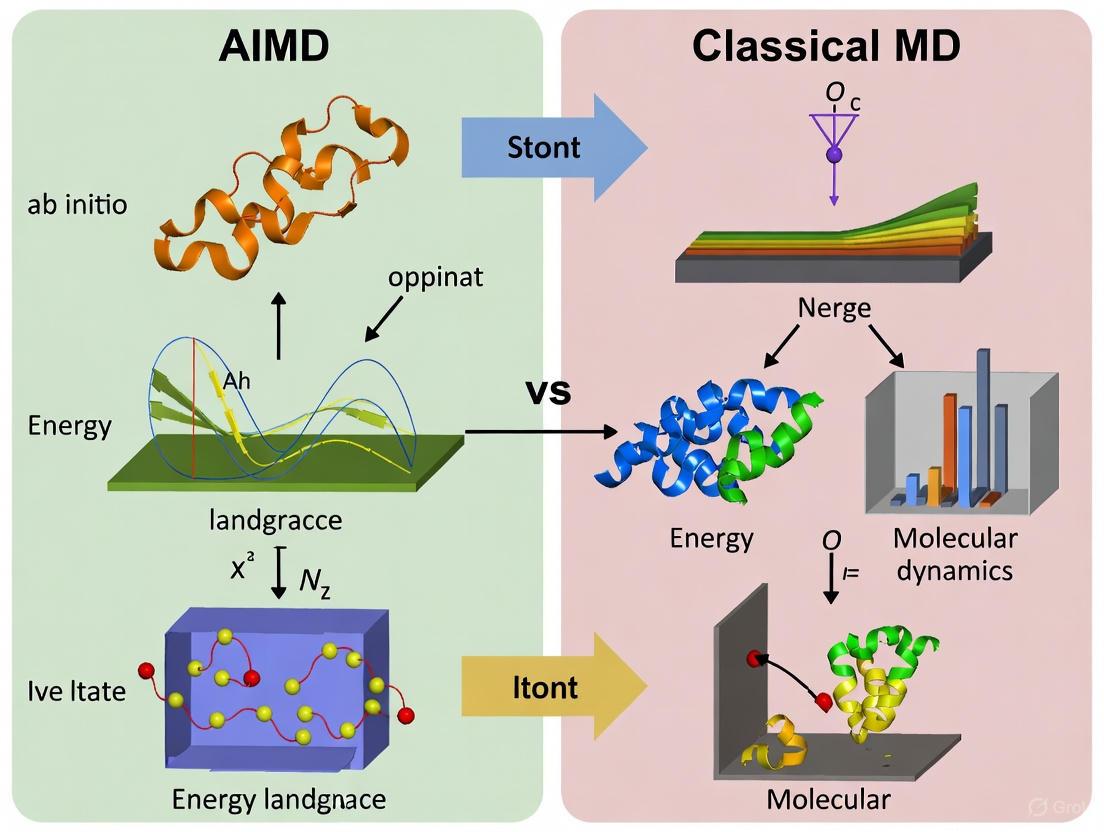

This article provides a comparative analysis of Ab Initio Molecular Dynamics (AIMD) and Classical Molecular Dynamics (CMD) for researchers and professionals in drug development.

Ab Initio vs. Classical MD: A Comprehensive Guide for Computational Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comparative analysis of Ab Initio Molecular Dynamics (AIMD) and Classical Molecular Dynamics (CMD) for researchers and professionals in drug development. It explores the fundamental principles distinguishing these methods, their specific applications in biomedical research—from enzymatic reactions to drug-receptor interactions—and the central trade-off between computational cost and quantum mechanical accuracy. The content further examines current limitations, including the high computational demands of AIMD and the accuracy challenges of CMD, while highlighting emerging solutions such as machine learning force fields and specialized hardware. Finally, it offers a practical framework for method selection, validating predictions with experimental data, and discusses the future trajectory of these integrated simulation approaches in accelerating therapeutic discovery.

First Principles: Unpacking the Core Theories of AIMD and CMD

In the realm of atomistic simulations, the choice between classical force fields and quantum mechanics (QM) represents a fundamental trade-off between computational efficiency and physical accuracy. This guide provides an objective comparison of these methodologies, contextualized within research on ab initio versus classical molecular dynamics (MD), to inform decisions in materials science and drug development.

The distinction between force fields and quantum mechanics is not merely technical but philosophical. Force fields use pre-parameterized analytical functions to describe atomic interactions, prioritizing computational speed for studying large systems over long timescales. In contrast, quantum mechanical methods solve the electronic Schrödinger equation, explicitly treating electrons to achieve high accuracy at a tremendous computational cost. The emerging paradigm of machine learning force fields (MLFFs) and quantum-mechanically derived force fields (QMDFF) is building a crucial bridge between these two worlds, offering near-QM accuracy for significantly reduced cost.

Technical Specification and Performance Comparison

The table below summarizes the fundamental characteristics of these approaches.

| Feature | Classical Force Fields (FF) | Quantum Mechanics (QM) | Machine Learning Force Fields (MLFF) | Quantum-Derived FF (QMDFF) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Theoretical Basis | Newtonian mechanics; pre-defined analytical potential functions [1] [2] | Quantum chemistry; solves electronic Schrödinger equation [3] | Trained neural networks on QM data [4] | Automated parameterization from single-molecule QM data [5] [6] |

| System Size | Very Large (Millions to billions of atoms) [1] [6] | Very Small (Tens to hundreds of atoms) [4] [6] | Medium to Large (Thousands to millions of atoms) [4] | Medium to Large [6] |

| Typical Timescale | Nanoseconds to milliseconds [1] | Picoseconds [4] | Nanoseconds [4] | Nanoseconds [6] |

| Computational Cost | Low [6] | Prohibitively High [4] [6] | Medium (High for training, lower for inference) [4] | Medium to Low [5] [6] |

| Treatment of Electrons | Implicit (fixed point charges); no electronic polarization (standard) or with polarizable FF [7] | Explicit [3] | Implicit, but can learn complex relationships [4] | Implicit (fixed point charges) [6] |

| Chemical Reactions | Only with reactive FF (e.g., ReaxFF) [1] | Native capability [3] | Possible if trained on reactive pathways | Via hybrid methods like Empirical Valence Bond (EVB) [6] |

| Parameterization Needs | Extensive, system-specific [2] [8] | Method and basis set choice | Large, diverse QM training dataset [4] [8] | Minimal; requires single-molecule QM input [5] [6] |

Quantitative Performance Benchmarks

The following table presents experimental data comparing the accuracy and performance of the different methods across key metrics.

| Method | Force Error (vs. QM) | Energy Error (vs. QM) | Energy Scale Accessible | Representative Application & Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Universal MLFF (CHGNET) | Not Specified | ~33 meV/atom [4] | Not Sufficient for Moiré Systems [4] | General materials discovery [4] |

| Specific-System MLFF (DPmoire) | 0.007 - 0.014 eV/Å [4] | Fraction of meV/atom [4] | MeV range (sufficient for moiré systems) [4] | Twisted bilayer materials; accurate relaxation [4] |

| QMDFF | Accurate geometry/conformation reproduction [5] [6] | Accurate for conformational landscapes [5] | Not Specified | Retinal photoswitches; excellent geometry/optical property prediction [5] |

| QM/MM with Fixed-Charge FF | Highly divergent/trends inverted vs. classical FF results [7] | Inferior to purely classical FF results [7] | Not Applicable | Hydration free energy calculation; requires balanced QM-MM parameters [7] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol: Developing a Machine Learning Force Field for Moiré Systems

The DPmoire software provides a robust methodology for constructing MLFFs for complex materials like twisted bilayers, where accurate relaxation is critical for electronic properties [4].

Dataset Generation:

- Structure Preparation: Construct a training set from non-twisted bilayer structures (e.g., 2x2 supercells) with various in-plane shifts to create different stacking configurations [4].

- Constrained Relaxation: Perform DFT structural relaxations for each configuration, fixing the in-plane coordinates of a reference atom in each layer to prevent drift [4].

- Molecular Dynamics Sampling: Run MD simulations using an on-the-fly MLFF algorithm (e.g., in VASP) under the same constraints to explore a wider configuration space. Data is selectively gathered from the underlying DFT calculations [4].

- Test Set Construction: Use large-angle moiré patterns relaxed via ab initio methods to create a separate test set, ensuring the MLFF is validated on relevant, complex structures [4].

MLFF Training: The collected data (energies, forces, stresses) is used to train a specialized MLFF model, such as one based on the Allegro framework, which can achieve the required meV-level accuracy [4].

Protocol: Parameterizing a Quantum-Derived Force Field (QMDFF)

QMDFF generates system-specific force fields directly from first-principles data of a single molecule, making it highly automated for functional materials [6] [5].

Quantum Mechanical Input Generation:

- Perform a geometry optimization of the target molecule in vacuum to find its equilibrium structure [6].

- Compute the Hessian matrix (second derivatives of energy) at the equilibrium geometry to obtain vibrational frequencies [6].

- Calculate atomic partial charges (e.g., using Hirshfeld partitioning) and covalent bond orders [6].

Force Field Construction:

- The QMDFF algorithm uses the QM input (structure, Hessian, charges, bond orders) to automatically parameterize all intramolecular terms (bonds, angles, torsions) and intermolecular non-covalent interactions [6]. The intramolecular potential is anharmonic, allowing for better description of bond breaking in hybrid reactive schemes [6].

Validation: The quality of the force field is assessed by comparing its predictions for equilibrium geometries, conformational landscapes, and optical properties against reference QM calculations and experimental data [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

This table lists key software and computational tools essential for research in this field.

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function | Key Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| DPmoire [4] | Software Package | Constructs MLFFs for twisted moiré systems | Automated dataset generation and training for accurate relaxation of 2D materials like TMDs. |

| QMSIM / Custom LAMMPS [6] | MD Simulation Engine | Performs MD simulations with QMDFF | Efficient large-scale simulations of functional materials using QMDFF parameters. |

| ReaxFF [1] | Reactive Force Field | Models chemical reactions within MD framework | Combustion, catalytic processes, and materials failure where bond formation/breaking is crucial. |

| ADAPT-VQE with DUCC [3] | Quantum Algorithm | Increases accuracy of quantum simulations on quantum processors | Quantum computing-based simulation of molecular electronic ground states, especially for strongly correlated electrons. |

| Wolf2 Pack [2] | Parametrization Workflow | Automates force-field optimization from QM data | Standardized and reproducible development of classical force field parameters. |

| ByteFF [8] | Data-Driven Force Field | Predicts MM parameters using Graph Neural Networks | High-accuracy, expansive coverage force field for drug-like molecules in computational drug discovery. |

Classical Molecular Dynamics (CMD) simulations serve as a foundational tool across materials science, chemistry, and drug development. The predictive power and physical realism of these simulations are almost entirely governed by a single core component: the interatomic potential, also known as the force field. Unlike its ab initio counterparts, which compute electronic structure on the fly, CMD relies on a library of pre-defined analytical functions and empirically tuned parameters to describe the interactions between atoms [1]. This guide provides a detailed comparison of this computational engine, its performance against alternative methods, and the experimental data that validates its use.

The Foundation: Force Fields as CMD's Engine

At the heart of every CMD simulation is the force field, a mathematical model that describes the potential energy of a system as a function of the nuclear coordinates [1]. The functional form is chosen a priori, and its parameters are derived from experimental data or high-level quantum mechanical calculations. A typical classical force field breaks down the total energy into contributions from bonded and non-bonded interactions:

Total Energy = Ebonded + Enon-bonded

Where:

- Ebonded accounts for energy costs associated with distorting bonds, angles, and dihedrals from their equilibrium values.

- Enon-bonded includes van der Waals interactions (often modeled with a Lennard-Jones potential) and electrostatic interactions (described by Coulomb's law) [1].

The fundamental compromise of CMD is that this pre-defined functional form offers tremendous computational efficiency, allowing researchers to simulate systems comprising millions of atoms over nanosecond to microsecond timescales. However, this comes at a cost: the force field cannot describe the making or breaking of chemical bonds, as the network of connectivity is fixed at the simulation's outset. For reactive systems, more sophisticated reactive force fields (ReaxFF), which can model bond formation and dissociation, have been developed, but they remain more computationally intensive than traditional CMD [1].

Table 1: Core Components of a Classical Force Field

| Energy Term | Typical Functional Form | Physical Description | Key Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bond Stretching | $E = \frac{1}{2}kb (r - r0)^2$ | Energy to stretch or compress a bond between two atoms. | Force constant ($kb$), equilibrium distance ($r0$). |

| Angle Bending | $E = \frac{1}{2}k{\theta} (\theta - \theta0)^2$ | Energy to bend the angle between three bonded atoms. | Force constant ($k{\theta}$), equilibrium angle ($\theta0$). |

| Dihedral Torsion | $E = k_{\phi} [1 + \cos(n\phi - \delta)]$ | Energy to rotate around a central bond between four atoms. | Barrier height ($k_{\phi}$), periodicity ($n$), phase ($\delta$). |

| van der Waals | $E = 4\epsilon \left[ \left(\frac{\sigma}{r}\right)^{12} - \left(\frac{\sigma}{r}\right)^{6} \right]$ | Attractive and repulsive forces from induced dipoles. | Well depth ($\epsilon$), van der Waals radius ($\sigma$). |

| Electrostatics | $E = \frac{qi qj}{4\pi \epsilon_0 r}$ | Coulombic interaction between charged atoms. | Atomic partial charges ($qi, qj$). |

Performance Comparison: CMD vs. Ab Initio MD

The choice between CMD and ab initio Molecular Dynamics (AIMD) is a trade-off between computational efficiency and predictive accuracy. AIMD uses quantum mechanics methods, typically Density Functional Theory (DFT), to compute the electronic structure and the resulting interatomic forces at every simulation step [9] [10]. This makes it a more general and parameter-free approach, but at a computational cost that is orders of magnitude higher than CMD.

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of CMD and AIMD

| Feature | Classical MD (CMD) | Ab Initio MD (AIMD) |

|---|---|---|

| Computational Engine | Pre-defined analytical potentials (force fields). | Quantum mechanical electronic structure calculations (e.g., DFT). |

| Parameterization | Relies on empirical parameters fitted to data. | No need for system-specific empirical parameters. |

| Computational Cost | Low; can simulate >1 million atoms for >1 microsecond. | Very high; typically limited to <1,000 atoms for <100 picoseconds. |

| Chemical Reactivity | Cannot model bond breaking/formation (standard CMD). | Naturally models chemical reactions and charge transfer. |

| Accuracy & Transferability | Limited by the quality and scope of the force field; may not transfer well to conditions outside its training set. | High accuracy for a wide range of systems; more transferable. |

| Primary Application | Studying structure, dynamics, and thermodynamics of large biomolecules, materials, and fluids. | Studying chemical reactions, electronic properties, and systems where bonding is complex. |

A compelling example of this comparison comes from the simulation of liquid metals. A study simulating the melting of Copper (Cu) and Nickel (Ni) found that while CMD using the Sutton-Chen many-body potential provided good statistics due to the large system size (1372 atoms), it showed a significant deviation from experimental melting points [9]. In contrast, AIMD, despite using a smaller simulation cell, provided a more accurate prediction of the melting point and other physical properties because it inherently captured the complex electronic interactions involved [9].

Experimental Validation and Protocol

The development and validation of any CMD force field require rigorous comparison with experimental data. The following protocol outlines a standard methodology for assessing the performance of an empirical potential, as demonstrated in a comprehensive study of potentials for chromia (Cr₂O₃) [11].

Experimental Protocol: Assessing an Empirical Potential

1. Objective: To evaluate and identify the most accurate empirical potential for simulating extended defects and diffusion properties in chromia (Cr₂O₃) [11].

2. Potential Selection: A set of available empirical potentials for the target material is compiled from the scientific literature [11].

3. Validation Dataset: An extensive dataset of experimental and high-fidelity ab initio data is assembled for validation. Key properties include [11]:

- Structural Properties: Crystal lattice parameters.

- Thermodynamic Properties: Cohesive energy, specific heat.

- Elastic Properties: Bulk modulus, Young's modulus, shear modulus.

- Defect Properties: Formation energies of point defects (e.g., vacancies, interstitials).

- Grain Boundary Properties: Grain boundary energies and structures.

4. Simulation and Comparison: Each selected empirical potential is used in CMD simulations to compute the properties listed in the validation dataset. The results are then quantitatively compared against the reference data to determine which potential most accurately reproduces the material's real-world behavior [11].

5. Outcome: The assessment identifies the most accurate potentials for simulating specific properties, such as diffusion and complex defect structures in chromia, providing researchers with clear guidance for selecting an appropriate model [11].

This workflow for force field validation and application can be summarized as follows:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful CMD simulations depend on more than just software. The "research reagents" in this context are the carefully parameterized force fields and validation datasets that make computational experiments possible.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents in Classical MD

| Reagent / Solution | Function in CMD Research | Example Use-Cases |

|---|---|---|

| Non-Reactive Force Fields | Describe bonded and non-bonded interactions in stable molecular systems. | Simulating protein folding (e.g., CHARMM, AMBER); studying polymer dynamics (e.g., OPLS); modeling material structure (e.g., EAM for metals) [1] [9]. |

| Reactive Force Fields (ReaxFF) | Enable simulation of chemical reactions by modeling bond formation/breaking. | Combustion processes; catalytic reactions; material fracture and oxidation [1]. |

| Validation Datasets | Benchmark and refine force field parameters against known experimental or quantum mechanical results. | Assessing a potential's accuracy for predicting density, viscosity, diffusion coefficients, or mechanical properties [12] [11]. |

| Parameter Fitting Tools | Software to optimize force field parameters to minimize error against validation data. | Developing new force fields for novel materials or molecules. |

The critical role of experimental validation is exemplified in a study on stearic acid with graphene nanoplatelets. In this work, CMD simulations were used to compute the density and viscosity of the system. The results were then directly compared against experimental measurements, confirming that the simulated data exhibited the same trend as the empirical findings. This agreement validated the force field's ability to capture the molecular interactions within the composite material [12].

Classical Molecular Dynamics, powered by its engine of pre-defined potentials and empirical parameters, remains an indispensable tool for investigating the microscopic world. Its unparalleled ability to simulate large systems over long timescales makes it the method of choice for studying biomolecular dynamics, material properties, and complex fluids. The emergence of machine-learning interatomic potentials (MLIPs) promises to bridge the gap between the speed of CMD and the accuracy of AIMD, offering a path to high-fidelity, large-scale simulations [13]. However, the fundamental principle endures: the reliability of any CMD study is intrinsically linked to the quality and careful validation of its underlying force field.

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation serves as a computational microscope, enabling researchers to observe atomistic processes that are inaccessible to experimental techniques. For decades, classical MD (CMD) has been the workhorse method, relying on pre-defined empirical force fields to calculate forces between atoms. These force fields use simplified mathematical formulas to describe atomic interactions, making simulations computationally efficient enough to study large systems over extended timescales. However, this efficiency comes at a cost: accuracy is limited by the force field's empirical parameterization, which often fails to capture complex quantum mechanical effects, particularly in scenarios involving bond breaking/formation, electronic polarization, or charge transfer [14] [15].

Ab initio molecular dynamics (AIMD) represents a paradigm shift by eliminating the dependence on empirical force fields. Instead, it calculates the interactions between atoms directly from the electronic structure using quantum mechanics at each step of the simulation. The "computational engine" referenced in the title is precisely this on-the-fly quantum mechanical force calculation, most commonly implemented using Density Functional Theory (DFT). This approach provides quantum mechanical accuracy, allowing AIMD to reliably model chemical reactions, electronic properties, and other phenomena where quantum effects are significant [16]. The trade-off is substantially higher computational cost, historically limiting AIMD to smaller systems (typically tens to hundreds of atoms) and shorter timescales (picoseconds to nanoseconds) compared to CMD [16] [15].

This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of these methodologies, focusing on the computational engine of AIMD, its performance relative to alternatives, and the experimental data validating its capabilities.

Fundamental Methodological Differences

The core distinction between CMD and AIMD lies in their treatment of interatomic forces. The table below summarizes the key differences in their computational approaches.

Table 1: Fundamental Comparison of Classical MD and Ab Initio MD

| Feature | Classical MD (CMD) | Ab Initio MD (AIMD) |

|---|---|---|

| Force Calculation | Pre-defined empirical potential functions | On-the-fly electronic structure calculation |

| Underlying Theory | Newtonian mechanics with parameterized potentials | Quantum mechanics (primarily Density Functional Theory) |

| Computational Cost | Relatively low | Very high |

| System Size | Thousands to millions of atoms | Tens to hundreds of atoms (up to ~10,000 with advanced algorithms) [16] [17] |

| Time Scale | Nanoseconds to milliseconds | Picoseconds to nanoseconds |

| Key Strength | Computational efficiency for large systems/broad sampling | Quantum accuracy for reactive systems and electronic properties |

| Primary Limitation | Transferability and accuracy of force fields | Computational expense limiting system size and timescale |

In CMD, the potential energy of a system is described by a force field—a collection of analytical functions with fitted parameters. A typical energy expression might include terms for bond stretching, angle bending, torsional angles, and non-bonded interactions (van der Waals and electrostatic). The parameters for these terms are derived from experimental data or quantum chemical calculations on small model systems. While this makes CMD highly efficient, its accuracy is inherently limited by the quality and transferability of these pre-defined parameters, often failing for systems far from their parameterization conditions [14] [15].

In contrast, AIMD merges the classical propagation of nuclear coordinates with a quantum mechanical description of the electrons. The most common approach, known as Born-Oppenheimer MD, involves solving the electronic structure problem for each new nuclear configuration at every MD time step. The forces on the nuclei are then derived directly from the quantum mechanical energy of the electronic ground state, effectively capturing the potential energy surface without prior approximation. This method is fundamentally more accurate but requires solving the electronic Schrödinger equation repeatedly, which dominates the computational cost [16].

Quantitative Performance Comparison

The theoretical advantages of AIMD translate into measurable differences in accuracy and resource requirements. The following table synthesizes quantitative performance data from benchmarking studies.

Table 2: Quantitative Benchmarking of Accuracy and Performance

| Property | Classical MD Performance | Ab Initio MD Performance | Experimental Reference/Benchmark |

|---|---|---|---|

| Energy Error (εe) | Can be as high as 10.0 kcal/mol (~434 meV/atom) [18] | ~1-10 meV/atom for MLMD; close to DFT accuracy [18] | "Quantum mechanical" accuracy target: < 43.4 meV/atom [18] |

| Force Error (εf) | Varies significantly with force field; often higher | Can achieve ~10-100 meV/Å, near DFT convergence thresholds [18] | Typical DFT convergence: ~25-40 meV/Å [18] |

| System Size | Routinely > 100,000 atoms | Typically 100-200 atoms; up to 100,000 with advanced codes [17] [15] | |

| Time Scale | >> Nanoseconds | < Nanoseconds for most applications | |

| Resource Consumption | Lower (CPU/GPU clusters) | Extremely high; can reach ~10 MW for large-scale AIMD [18] | |

| Structural Properties | Good for well-parameterized systems; limited transferability [15] | Excellent agreement with experiment and high-level theory [15] | X-ray/neutron scattering data [19] |

A systematic benchmarking study of CaO-Al₂O₃-SiO₂ melts highlighted these contrasts. While certain classical force fields could accurately reproduce densities and Si–O coordination environments, they showed significant variability and poorer performance in predicting dynamic properties like diffusion coefficients. In contrast, AIMD simulations served as a reliable reference for validating these structural properties and provided greater consistency for transport properties, albeit at a much higher computational cost that restricted the system size and simulation time [15].

The computational burden of AIMD is being addressed through hardware and algorithmic innovations. For instance, the development of a special-purpose MD processing unit (MDPU) claims to reduce time and power consumption by approximately 10³ to 10⁹ times compared to state-of-the-art machine-learning MD or AIMD run on general-purpose CPUs/GPUs, while maintaining ab initio accuracy [18]. Furthermore, linear-scaling algorithms and efficient parallelization are pushing the boundaries, enabling simulations of tens of thousands of atoms on high-performance computing platforms [17].

The AIMD Computational Workflow

The process of performing an AIMD simulation involves a tightly integrated cycle of nuclear motion and electronic structure calculation. The following diagram visualizes this workflow, highlighting the central role of the quantum mechanical force engine.

Diagram Title: The Ab Initio Molecular Dynamics Cycle

This workflow illustrates the core computational engine of AIMD. The critical and most expensive step is the calculation of the electronic ground state for each new nuclear configuration. This step typically involves:

- Constructing the Hamiltonian based on the current atomic positions.

- Solving the Kohn-Sham equations (in DFT-based AIMD) to obtain the electron density and total energy.

- Computing the forces on all nuclei as the derivative of the total energy with respect to nuclear positions: ( FI = -\nablaI E\rho ), where ( E ) is the total energy and ( \rho ) is the electron density that depends on all nuclear positions ( {\mathbf{R}_I} ) [16].

This process is repeated for thousands of time steps, making the efficiency and accuracy of the electronic structure solver paramount.

Best Practices and Experimental Protocols

Validating and running AIMD simulations requires careful methodology. The protocols below are synthesized from the analyzed benchmarking studies.

Protocol for Validating Force Fields Against AIMD

When using AIMD to benchmark classical force fields, as in the study of oxide melts [15], a standard protocol is:

- System Selection: Choose multiple compositions and temperatures relevant to the intended application.

- AIMD Reference Calculation: Perform relatively short (tens of picoseconds) AIMD simulations for each condition. Use a well-established DFT functional and pseudopotentials. Ensure energy convergence is tight.

- CMD Production Runs: Run CMD simulations using the candidate force fields for the same conditions, leveraging their efficiency for longer durations (nanoseconds) to improve statistics.

- Property Comparison: Quantitatively compare key structural properties (density, radial distribution functions, coordination numbers) and dynamic properties (mean-squared displacement for diffusion, conductivity) from CMD against the AIMD reference and any available experimental data.

- Accuracy Assessment: Evaluate which force field most consistently reproduces the AIMD results across all tested conditions to determine its transferability and reliability.

Protocol for On-the-Fly Machine Learning Force Field Training

A modern approach to bridge the cost-accuracy gap involves using AIMD to train machine learning force fields (MLFFs) on the fly, as implemented in the FLARE algorithm [20]:

- Initialization: Start an MD simulation and use DFT to calculate forces for an initial, small set of atomic configurations.

- Model Training: Train a Gaussian Process (GP) regression model on these data to create a preliminary force field.

- Uncertainty-Guided MD: Use the GP model to run MD. The model provides an uncertainty estimate ( \sigma_{i\alpha} ) for each force prediction.

- Active Learning Decision: For each MD step, compare the epistemic uncertainty to a pre-set threshold. If the uncertainty is too high, a DFT calculation is performed for that configuration, and the result is added to the training set.

- Model Update: The GP model is updated with the new data, improving its predictive power for similar configurations in the future.

- Production Run: Once the model uncertainty is consistently low, a full-scale, computationally efficient MD simulation can be performed with the MLFF, which now carries near-AIMD accuracy.

Software and Hardware Solutions for AIMD

Several specialized software packages enable AIMD simulations, each with unique strengths and optimization focuses.

Table 3: Comparison of Selected Ab Initio MD Software Packages

| Software | Key Features | Basis Set | Notable Strengths | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CP2K | Strongly focused on AIMD, linear-scaling methods | Gaussian and Plane Waves (GPW) | High efficiency for large systems; extensive free energy methods [21] | Steeper learning curve; documentation can be terse [21] |

| QXMD | Community platform for QMD with extensions | Plane Waves | Includes non-adiabatic dynamics and multiscale shock technique [22] | |

| MGmol | Linear-scaling algorithm for large systems | Real-space grid | Excellent parallel scaling; demonstrated on 100,000+ atoms [17] | |

| VASP | Widely used in materials science | Plane Waves | High accuracy; broad community adoption | Commercial license |

The hardware landscape is also evolving. Traditional AIMD runs on general-purpose CPUs/GPUs, which suffer from the "memory wall" and "power wall" bottlenecks, where most time and energy is spent moving data rather than calculation [18]. Emerging solutions include:

- Specialized Hardware: The proposed MD Processing Unit (MDPU) uses a computing-in-memory (CIM) architecture to drastically reduce data movement, claiming orders of magnitude improvements in speed and power efficiency over CPU/GPU setups [18].

- High-Performance Computing (HPC): Massively parallel supercomputers remain essential. Efficient parallelization allows system size to scale nearly linearly with processor count, enabling simulations of over 100,000 atoms [17].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Beyond core software, conducting robust AIMD research requires a suite of "computational reagents."

Table 4: Essential Computational Tools for AIMD Research

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Pseudopotential Libraries | GBRV, PSLibrary, SG15 | Replace core electrons with effective potentials to reduce computational cost [16] |

| Exchange-Correlation Functionals | PBE, SCAN, r2SCAN, HSE06 | Define the approximation for electron exchange and correlation in DFT [16] |

| Trajectory Analysis Suites | VMD, MDAnalysis, CP2K's tools | Visualize and analyze simulation trajectories (structures, energies, dynamics) |

| Automated Workflow Managers | AiiDA, ASE | Automate complex simulation protocols, ensure reproducibility, and manage data |

| Active Learning Platforms | FLARE [20] | Automate the training of accurate machine-learning force fields using on-the-fly uncertainty quantification |

The computational engine of AIMD, powered by on-the-fly quantum mechanical force calculations, provides an indispensable tool for simulating materials and molecular processes where quantum accuracy is paramount. While classical MD remains the method of choice for simulating large systems and long timescales, its dependence on empirical force fields limits its predictive power for chemical reactivity and electronic phenomena.

The benchmarking data clearly shows that AIMD offers superior accuracy for structural and dynamic properties, serving as a gold standard for validating classical force fields. Its primary limitation—extreme computational cost—is being actively addressed through innovations in algorithmic design (linear-scaling methods, active learning MLFFs) and hardware architecture (specialized MDPUs). Tools like FLARE [20] and CP2K [21] are making it increasingly feasible to achieve AIMD-level accuracy for more complex systems and longer trajectories.

For researchers in drug development and materials science, the choice between CMD and AIMD hinges on the specific scientific question. CMD is suitable for sampling conformational space and studying large biomolecular machines, while AIMD is essential for understanding reaction mechanisms, catalytic processes, and properties dependent on electronic structure. The ongoing integration of machine learning with AIMD promises a future where the line between these methods blurs, enabling accurate simulations of biologically and industrially relevant systems at unprecedented scales.

Table of Contents

- Theoretical Foundations: Born-Oppenheimer and DFT

- A Landscape of Ab Initio Molecular Dynamics Methods

- Comparative Performance: Accuracy and Computational Cost

- Illustrative Workflow and Research Toolkit

- Conclusions and Future Directions

Theoretical Foundations: Born-Oppenheimer and DFT

The Born-Oppenheimer (BO) approximation is a cornerstone of computational chemistry, enabling the separation of electronic and nuclear motion. It posits that due to their significantly larger mass, nuclei move much slower than electrons. Consequently, one can solve for the electronic structure assuming fixed nuclear positions, generating a potential energy surface (PES) upon which the nuclei move [23] [24]. This approximation is the bedrock of most electronic structure methods. However, its limitation becomes apparent in processes involving nonadiabatic events, such as those occurring at conical intersections, where the coupling between different electronic states becomes significant and cannot be ignored [23] [25].

Density Functional Theory (DFT) provides a powerful framework for solving the electronic Schrödinger equation under the BO approximation. Instead of dealing with the complex many-electron wavefunction, DFT uses the electron density as the fundamental variable, dramatically reducing computational cost [24]. The Hohenberg-Kohn theorems establish that all ground-state properties are unique functionals of the electron density. The practical application of DFT is achieved through the Kohn-Sham scheme, which introduces a fictitious system of non-interacting electrons that has the same density as the real system. The main challenge in DFT is the accuracy of the exchange-correlation functional, which accounts for quantum mechanical effects not covered by the classical electrostatic terms [24]. While DFT with standard approximations has been highly successful, it can struggle with van der Waals forces, charge-transfer excitations, and strongly correlated systems [24] [26].

Born-Oppenheimer Molecular Dynamics (BOMD) directly combines these two concepts. In BOMD, the nuclear trajectories are propagated classically on a PES generated by solving the electronic structure problem using DFT (or other ab initio methods) at each time step [27]. This ensures that the forces on the nuclei are consistent with the instantaneous electronic ground state, making it a highly accurate approach. The primary computational expense lies in the repeated self-consistent solution of the Kohn-Sham equations at every step [27] [28].

A Landscape of Ab Initio Molecular Dynamics Methods

Various AIMD methods have been developed, offering different trade-offs between computational cost, accuracy, and applicability. The table below compares the foundational approaches.

Table 1: Key Ab Initio Molecular Dynamics Methodologies

| Method | Core Principle | Handles Nonadiabatic Effects? | Key Advantage | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Born-Oppenheimer MD (BOMD) [27] | Nuclei move on the ground-state BO PES; electronic structure is solved at each step. | No | High accuracy; "exact" classical dynamics on the BO surface [27]. | Computationally expensive due to full electronic convergence at every step. |

| Car-Parrinello MD (CPMD) [28] | Introduces a fictitious dynamics for electronic orbitals, keeping them close to the ground state. | No | Avoids costly electronic minimization at each step; improved computational efficiency. | Requires smaller time steps; introduces spurious "mass parameter" for electrons [28]. |

| Extended Lagrangian MD (ELMD) [27] | Propagates electronic degrees of freedom alongside nuclei using a fictitious mass. | No | Faster than BOMD as electrons are not fully optimized. | An approximation to exact dynamics; validity must be tested for the property of interest [27]. |

| Ehrenfest MD [28] | Nuclei move on a single, average PES computed from multiple electronic states. | Yes | Can describe nonadiabatic processes where multiple electronic states are involved. | "Mean-field" approach fails when nuclear motion requires distinct PESs (e.g., at conical intersections) [28]. |

| Beyond-BO TDDFT [23] | Formulates a time-dependent DFT for coupled electron-nuclear dynamics beyond the BO approximation. | Yes | Formally exact framework for nonadiabatic dynamics using time-dependent densities. | Relies on development of accurate and computationally tractable exchange-correlation functionals [23]. |

To elucidate the logical relationships and decision pathways for selecting a computational method, the following diagram outlines a typical workflow in modern simulation studies.

Diagram 1: A workflow for selecting a molecular dynamics simulation approach, highlighting the role of AIMD and its alternatives.

Comparative Performance: Accuracy and Computational Cost

The theoretical advantages and limitations of different methods manifest clearly in practical applications. Benchmarking studies and direct comparisons provide crucial data for researchers to select the appropriate tool.

A systematic study of CaO-Al₂O₃-SiO₂ melts compared classical MD with empirical force fields against ab initio MD (AIMD, which typically uses BOMD/DFT). The study concluded that while classical MD is computationally efficient, its "accuracy relies entirely on the quality of the empirical force field used." In contrast, AIMD provides "a more rigorous description of atomic interactions," but is restricted to "relatively small systems (typically <200 atoms) and short timescales (tens of picoseconds)" [15]. This trade-off is fundamental.

The choice of the exchange-correlation functional in DFT-based dynamics is critical. A study on liquid H₂S used BOMD with the non-local VV10 functional to include van der Waals dispersion interactions accurately. This approach successfully predicted the structure and energetics of the (H₂S)₂ dimer and allowed for the analysis of polarization effects in the liquid phase [26]. This demonstrates how the accuracy of BOMD is directly tied to the underlying electronic structure theory.

For nonadiabatic processes, the performance gap between methods is even more pronounced. In modeling NO scattering from Au(111), Born-Oppenheimer MD (BOMD) alone predicted significant vibrational relaxation via the adiabatic channel. However, it was insufficient to fully reproduce experimental observations. Adding nonadiabatic effects through molecular dynamics with electronic friction (MDEF) improved agreement for single-quantum relaxation but failed for multi-quantum relaxation. The independent electron surface hopping (IESH) method, which explicitly treats electron transfer, achieved the best agreement with a wide range of experimental data, highlighting the necessity of going beyond the BO approximation for certain phenomena [25].

Table 2: Performance Comparison from NO/Au(111) Scattering Studies [25]

| Computational Method | Description | Performance in Reproducing Multi-Quantum Vibrational Relaxation |

|---|---|---|

| BOMD | Dynamics on a single adiabatic ground-state PES. | Underestimates experimental relaxation probabilities. |

| MDEF | BOMD with frictional forces from electron-hole pairs. | Improves single-quantum relaxation prediction but fails for multi-quantum relaxation. |

| IESH | Explicit treatment of electron transfer between molecule and metal. | Achieves the best agreement with experimental state distributions. |

Illustrative Workflow and Research Toolkit

A typical BOMD simulation, as implemented in codes like Q-Chem, follows a well-defined protocol [27]:

- Initialization: Specify initial Cartesian coordinates and velocities for all nuclei. Velocities can be set manually or sampled from a Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution at a target temperature.

- Force Calculation: At each time step, perform a DFT energy and analytic gradient calculation to determine the forces acting on each nucleus.

- Nuclear Propagation: Integrate Newton's equations of motion (e.g., using the Velocity Verlet algorithm) to update nuclear positions and velocities.

- Iteration: Repeat steps 2 and 3 for the desired number of steps. To accelerate the calculation, the initial guess for the DFT calculation can be extrapolated from Fock matrices or density matrices of previous steps [27].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Components for an AIMD Study

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for AIMD Simulations

| Tool / Component | Function / Purpose | Example or Note |

|---|---|---|

| Electronic Structure Code | Solves the quantum mechanical problem to obtain energy and forces. | Q-Chem [27], CP2K [28], CPMD [28]. |

| Exchange-Correlation Functional | Approximates quantum effects in DFT; critical for accuracy. | LDA, GGA (e.g., PBE), meta-GGA, and hybrid functionals. Non-local functionals (e.g., VV10) for dispersion [24] [26]. |

| Pseudopotentials / Basis Sets | Represent core electrons and the spatial range of valence orbitals. | Plane waves, Gaussian-type orbitals; choice balances accuracy and cost. |

| Thermostat / Barostat | Controls temperature and pressure to mimic experimental conditions. | Nose-Hoover, Langevin thermostat; Parrinello-Rahman barostat. |

| Trajectory Analysis Software | Analyzes output trajectories to compute properties of interest. | In-house scripts, VMD, MDTraj, for structure, dynamics, and spectra. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) | Provides the computational power required for feasible simulation times. | Essential for all but the smallest systems. |

Ab Initio Molecular Dynamics, founded on the Born-Oppenheimer approximation and Density Functional Theory, provides an powerful framework for simulating materials and molecular systems with high fidelity. BOMD remains the benchmark for accuracy on a single potential energy surface, while methods like CPMD and ELMD offer computational efficiencies. For processes involving electronic excitations or transitions, nonadiabatic methods like Ehrenfest dynamics and the formally exact beyond-BO TDDFT are essential, though they come with their own set of challenges and computational costs [23] [25] [28].

The future of AIMD lies in bridging the current gaps. This includes the development of more accurate and efficient exchange-correlation functionals, particularly for nonadiabatic processes [23], improved algorithms to extend the spatial and temporal scales of AIMD simulations, and robust multi-scale schemes that seamlessly combine the accuracy of AIMD with the efficiency of classical MD for large systems [15]. As these methods continue to mature, their role in predicting and understanding complex phenomena in chemistry, materials science, and drug development will only become more central.

Inherent Strengths and Limitations in System Size and Timescale

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation serves as a computational microscope, enabling researchers to observe atomic-scale processes that are often difficult to probe experimentally. The choice of MD methodology involves navigating a fundamental trade-off between computational accuracy and efficiency, particularly regarding the achievable system size and simulation timescale. Ab initio molecular dynamics (AIMD), which uses quantum mechanical calculations to determine interatomic forces, provides high chemical accuracy but at extreme computational cost. In contrast, classical molecular dynamics (CMD) employs predefined analytical potential functions, enabling simulations of larger systems for longer durations but with reduced accuracy and transferability. Recently, machine learning molecular dynamics (MLMD) has emerged as a bridge between these approaches, offering near-ab initio accuracy with significantly improved computational efficiency. This guide provides a systematic comparison of these methodologies, focusing on their inherent capabilities and limitations for research applications in materials science and drug development.

Quantitative Comparison of MD Methodologies

Table 1: Performance Metrics Across MD Methodologies

| Methodology | Accuracy (Force Error) | Max Practical System Size | Max Practical Timescale | Computational Speed | Power Consumption |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AIMD (DFT) | Reference (0 meV/Å) | Hundreds of atoms [29] | Picoseconds [29] | ~10-6 steps/sec [18] | ~10 MW [18] |

| MLMD | 10-100 meV/Å [18] | 10,000+ atoms [29] | Nanoseconds [30] [29] | ~103 steps/sec [18] | ~10 kW [18] |

| CMD | 100-1000 meV/Å [18] | Millions of atoms | Microseconds to milliseconds | ~106 steps/sec | ~100 W |

| Specialized Hardware (MDPU) | ~10-100 meV/Å [18] | Not specified | Not specified | ~109 steps/sec vs AIMD [18] | ~103 reduction vs MLMD [18] |

Table 2: Applicability to Research Scenarios

| Research Scenario | Recommended Method | Key Limitations | Typical Simulation Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Folding | MLMD [29] | Limited by conformational sampling | 10,000 atoms,数百ns [29] |

| Electrochemical Interfaces | AI2MD [30] | Equilibration challenges at picosecond scale [30] | 100s atoms, nanosecond scale [30] |

| Reaction Mechanism Studies | QM/MM [31] | Timescale limitation for rare events [31] | QM region: 10s-100s atoms; MM region: 1000s atoms |

| Material Property Prediction | Fine-tuned MLIPs [32] | Requires system-specific training data [32] | 1000s atoms, nanosecond scale |

Key Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

AI-Accelerated Ab Initio Molecular Dynamics (AI2MD)

The ElectroFace dataset development exemplifies the AI2MD approach for studying electrochemical interfaces [30]. This methodology combines the accuracy of ab initio calculations with the scalability of machine learning potentials.

Experimental Protocol:

- Interface Construction: Create slab-vacuum models by cleaving bulk materials along selected facets, ensuring stoichiometric and symmetric slabs to avoid spurious dipole interactions [30]

- Hydration: Use PACKMOL to fill an orthorhombic box (~25 Å height) with water molecules at 1 g/cm³ density [30]

- Equilibration: Perform classical MD with SPC/E force field in NVT ensemble to equilibrate water structure [30]

- AIMD Simulation: Execute 20-30 ps AIMD using CP2K/QUICKSTEP with PBE functional, D3 dispersion correction, and GTH pseudopotentials at 330K [30]

- ML Potential Development: Apply active learning workflow (DP-GEN or ai2-kit) with iterative training, exploration, screening, and labeling steps [30]

- Production MLMD: Run nanosecond-scale simulations using LAMMPS with DeePMD-kit potentials [30]

Hybrid QM/MM Molecular Dynamics

QM/MM simulations partition the system into a quantum mechanical region for chemically active sites and a molecular mechanical region for the environment, using electrostatic embedding to account for mutual interactions [31].

Experimental Protocol:

- System Partitioning: Define QM region (typically 10s-100s atoms) containing reactive centers and MM region for surrounding environment [31]

- Force Field Parameterization: Use AMBER ff14SB for proteins, ff99bsc0 for DNA, and TIP3P for water [31]

- Enhanced Sampling: Implement multiple time step algorithms or replica-exchange methods to accelerate rare events [31]

- Convergence Testing: Ensure proper sampling of properties of interest at relevant temperatures [31]

Machine Learning Force Fields for Biomolecules

The AI2BMD system enables ab initio accuracy for large biomolecules through a fragmentation approach and machine learning force fields [29].

Experimental Protocol:

- Protein Fragmentation: Decompose proteins into 21 standardized dipeptide units (12-36 atoms each) [29]

- Dataset Construction: Scan main-chain dihedrals and run AIMD with 6-31g* basis set and M06-2X functional to generate training data [29]

- Model Training: Train ViSNet models on comprehensive dataset (20.88 million samples) to predict energies and forces [29]

- MD Simulation: Perform simulations with polarizable solvent (AMOEBA force field) using learned potentials [29]

- Validation: Compare against DFT calculations and experimental data (e.g., NMR J-couplings) [29]

Advanced ML Training Techniques

Dynamic Training: This approach incorporates temporal sequence information by training on subsequences of AIMD simulations and integrating equations of motion directly into the training process [33].

Physics-Informed Forecasting: The PhysTimeMD framework formulates MD as a displacement forecasting problem with Morse potential constraints to ensure physical plausibility [34].

Foundation Model Fine-Tuning: System-specific adaptation of pre-trained MLIPs (MACE, GRACE, SevenNet, MatterSim, ORB) reduces force errors by 5-15x and energy errors by 2-4 orders of magnitude [32].

Workflow Visualization

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Tool/Solution | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| CP2K/QUICKSTEP | Mixed Gaussian/plane-wave DFT code for AIMD | Electrochemical interfaces, material properties [30] |

| DeePMD-kit | Deep neural network potential training | MLMD for extended timescales [30] |

| LAMMPS | High-performance MD simulator | Production MLMD simulations [30] |

| AMOEBA Force Field | Polarizable force field for solvents | Accurate solvation in biomolecular simulations [29] |

| ViSNet | Physics-informed neural network potential | Biomolecular dynamics with ab initio accuracy [29] |

| MiMiC Framework | QM/MM simulation framework | Reactive events in complex environments [31] |

| MACE/GRACE/SevenNet | Foundation MLIP architectures | Transferable potentials with fine-tuning capability [32] |

| aMACEing Toolkit | Unified fine-tuning interface | System-specific adaptation of MLIPs [32] |

| ECToolkits | Analysis of electrochemical properties | Interface structure characterization [30] |

The landscape of molecular dynamics methodologies presents researchers with complementary tools, each with distinct strengths for specific scientific questions. AIMD remains the gold standard for accuracy but is fundamentally limited to small systems and short timescales. CMD provides access to large spatiotemporal scales but sacrifices chemical accuracy and transferability. MLMD approaches, particularly those utilizing foundation models with system-specific fine-tuning, increasingly bridge this gap, offering a compelling balance of accuracy and efficiency. Emerging hardware accelerators like MDPU promise further dramatic improvements in computational efficiency. The optimal methodology choice depends critically on the specific research question, with system size, required timescale, and accuracy needs determining the most appropriate approach. As machine learning potentials continue to mature and specialized hardware becomes more accessible, the accessible simulation domain will continue to expand, enabling previously intractable investigations in materials science and drug development.

Strategic Applications: Where AIMD and CMD Excel in Biomedical Research

The atomistic simulation of chemical reactions, particularly the complex bond-breaking and bond-forming events in enzymatic processes, presents a formidable challenge in computational chemistry. Within the broader thesis of comparing ab initio molecular dynamics (AIMD) with classical approaches, this guide objectively evaluates their performance for modeling chemical reactivity. Classical Molecular Dynamics (MD), a workhorse for biomolecular simulation, relies on pre-defined, static potential functions (force fields) to describe interatomic interactions. These potentials, such as the harmonic potential for bonds ((U{ij} = \frac{1}{2}k(ri - r_j)^2)), are excellent for simulating physical movements around equilibrium but lack the fundamental capacity to simulate the making and breaking of chemical bonds [35]. Their mathematical form, often a simple quadratic, means the bond energy increases unrealistically to infinity as it stretches, preventing dissociation [35].

In contrast, Ab Initio Molecular Dynamics (AIMD) eliminates this limitation by calculating the potential energy and forces "on the fly" using quantum mechanical (QM) methods, typically Density Functional Theory (DFT) [36]. The electronic structure is recalculated at each step, allowing the potential energy surface to respond naturally to atomic configurations, thereby enabling a faithful representation of chemical reactions. A third hybrid approach, Quantum Mechanics/Molecular Mechanics (QM/MM), offers a pragmatic compromise by treating the chemically active site (e.g., an enzyme's active site) with QM while describing the larger protein environment with the computational efficiency of classical MD [36]. This review provides a detailed comparison of these methods, supported by experimental data and protocols, to guide researchers in selecting the appropriate tool for probing enzymatic reactions and reactivity.

Methodological Comparison: Principles, Capabilities, and Limitations

The core difference between simulation methods lies in how they compute the potential energy that drives atomic motion.

Theoretical Foundations and Force Fields

- Classical MD: This method uses parametric potential functions. Bonds, angles, and dihedrals are described with simple analytical forms, while non-bonded interactions use Lennard-Jones and Coulomb potentials. As one expert notes, "You cannot break bonds in classical MD" with these standard potentials [35]. The fixed connectivity is a fundamental limitation for studying reactions.

- Reactive Force Fields (ReaxFF): An advanced class of classical MD, ReaxFF addresses this by making the bond order a function of interatomic distance [1] [35]. This dynamic bond order, derived from QM data, allows bonds to form and break during simulation. The potential energy, such as a modified Morse potential, incorporates this bond order, enabling the simulation of complex reactive processes like combustion and catalysis without the full cost of QM [1] [35].

- Ab Initio MD (AIMD): AIMD is a "first-principles" method. It requires no pre-parameterized force field for intra-molecular interactions. Instead, it directly solves the electronic Schrödinger equation for the nuclear configuration at each time step, making it uniquely capable of discovering unexpected reaction pathways and transition states [36] [37].

- QM/MM: This method couples a QM region (handled by AIMD or other QM methods) with an MM region (handled by classical MD). It is particularly powerful for enzymatic reactions, where the active site is treated quantum-mechanically, and the solvating protein environment is treated classically [36].

Quantitative Comparison of Methodologies

Table 1: Comparison of Molecular Dynamics Methods for Chemical Reactivity

| Feature | Classical MD | Reactive MD (ReaxFF) | Ab Initio MD (AIMD) | QM/MM |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bond Breaking/Formation | Not possible without ad hoc methods | Yes, via dynamic bond orders | Yes, inherent to the method | Yes, within the QM region |

| Underlying Theory | Newtonian mechanics with pre-defined potentials | Empirical potentials trained on QM data | Quantum mechanics (e.g., DFT) | Hybrid QM (DFT) & Classical MM |

| Parameter Dependence | High; system-specific force fields required | High; requires ReaxFF parameterization for system | Low; no system-specific force field needed | Moderate; requires MM force field & QM/MM coupling parameters |

| Computational Cost | Low | Medium to High | Very High | High (scales with QM region size) |

| System Size Limit | Millions to billions of atoms | Thousands to hundreds of thousands of atoms | Hundreds of atoms | Thousands of atoms (MM) + tens of atoms (QM) |

| Time Scale Limit | Nanoseconds to milliseconds | Picoseconds to nanoseconds | Picoseconds | Picoseconds to nanoseconds |

| Key Applicability | Structural dynamics, folding, transport | Combustion, catalysis, pyrolysis | Reaction mechanisms, catalysis, spectroscopy | Enzymatic reactions, solvent effects on reactivity |

Performance Analysis: Applications and Experimental Validation

Case Study: AIMD for Cellulose Pyrolysis

A definitive 2023 study on the thermal cracking of cellobiose (the repeating unit of cellulose) provides a clear example of AIMD's power to elucidate reaction mechanisms at transient high temperatures [37]. The study employed AIMD based on Density Functional Theory (DFT) with a generalized gradient approximation (PBE functional) and Grimme dispersion correction. Simulations were performed in the NVT ensemble using a Nose-Hoover thermostat.

Experimental Protocol [37]:

- System Preparation: A cellobiose molecule was placed in a periodic boundary box (18 × 18 × 18 Å).

- Geometry Optimization: The structure was first optimized to a minimum energy configuration.

- Equilibration: A 5 ps AIMD simulation was run at 298.15 K to equilibrate the system.

- Production Run: 15 ps AIMD simulations were conducted at various temperatures (343 K, 1,800 K, 2,400 K, and 3,000 K) to probe thermal stability and cracking.

- Analysis: The Radial Distribution Function (RDF) was used to analyze bond stability, and the simulation trajectory was visually inspected for bond dissociation and product formation.

Key Findings from AIMD [37]:

- At 343 K, the cellobiose structure remained stable.

- At 2,400 K, the AIMD trajectory directly showed the breaking of the glycosidic bond (C23–O31) and the opening of the pyran ring.

- At 3,000 K, new characteristic products like CO, H₂O, CH₃OH, H₂, and CH₄ were observed to form, providing atomic-level insight into the cracking mechanism.

- RDF analysis quantitatively confirmed that C–C and C–O bonds (bond energy ~330 kJ/mol) were much more susceptible to breaking at high temperatures than O–H bonds (bond energy 464 kJ/mol).

This case highlights how AIMD can track reaction coordinates in real-time, identifying initial bond-breaking events and subsequent formation of reaction products without any prior expectation of the mechanism.

Comparative Performance Data

Table 2: Summary of Key Experimental Results from Cellobiose Cracking AIMD Study [37]

| Simulation Temperature | Observed Phenomena | Key Chemical Events | Characteristic Products Formed |

|---|---|---|---|

| 343 K | System stable | No bond breaking | None |

| 1,800 K | Enhanced molecular motility | Bond stretching, no breaking | None |

| 2,400 K | Start of decomposition | Glycosidic bond break, pyran ring opening | None |

| 3,000 K | Extensive cracking | Multiple C–C and C–O bond breaks | CO, H₂O, CH₃OH, H₂, CH₄ |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Software

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Reactive Molecular Dynamics

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| CP2K | Software | A powerful package for performing AIMD and QM/MM simulations, particularly efficient with DFT. | Well-suited for large periodic systems; open-source. |

| AMBER | Software | A suite of biomolecular simulation programs that includes support for QM/MM simulations. | Widely used in drug development for simulating proteins, DNA, and ligands. |

| GROMACS | Software | A high-performance MD engine for classical MD, also capable of running ReaxFF simulations. | Extremely fast for classical MD; free and open-source. |

| ReaxFF | Force Field | A reactive force field for simulating chemical reactions in large, complex systems. | Force field parameters must be available and accurate for the specific chemical elements in the system. |

| VMD | Software | A visualization and analysis program for displaying simulation trajectories and analyzing results. | Essential for visualizing bond breaking/forming events and calculating properties like RDF. |

Visualizing Workflows and Method Selection

The following diagram illustrates the typical workflow for an AIMD simulation of a chemical reaction, from system setup to analysis.

AIMD Reaction Simulation Workflow

The decision of which computational method to use for a reactivity problem is critical. The flowchart below provides a logical guide for researchers.

Method Selection for Reactivity

The choice between AIMD and classical approaches for modeling enzymatic reactions and bond formation is a trade-off between computational fidelity and cost. Classical MD is incapable of modeling reactivity without reactive extensions. ReaxFF MD offers a powerful, scalable alternative for complex materials and processes where accurate parameter sets exist, providing insight into reactions on larger scales than possible with pure QM methods [1]. However, for the ultimate accuracy and exploratory power to uncover unknown reaction pathways, particularly in catalytic and enzymatic environments, AIMD remains the gold standard. The emerging trend of using machine learning to create potentials with near-DFT accuracy promises to further blur these lines, potentially offering the accuracy of AIMD at a fraction of the cost [36]. For now, the selection of a method must be guided by the specific research question, the system size, and the availability of reliable parameters.

Ab initio molecular dynamics (AIMD) has become an indispensable tool for simulating complex molecular interactions where classical force fields fall short. This guide compares the performance of AIMD against classical molecular dynamics for modeling two particularly challenging systems: proton transfer reactions and complex charged fluids.

Classical molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, while computationally efficient, are limited by their pre-defined, fixed-charge force fields which cannot model bond breaking/formation or electronic polarization [38]. This presents a critical limitation for studying essential processes like proton transfer reactions in biological systems and catalysis, or for accurately capturing the structure and dynamics of complex charged fluids like ionic liquids [39].

AIMD overcomes these limitations by calculating forces "on the fly" from electronic structure theory, typically using Density Functional Theory (DFT). This provides a quantum-mechanically accurate potential energy surface, enabling the simulation of chemical reactions and polarizability [29]. The primary challenge has been AIMD's formidable computational cost, which restricts system sizes and simulation timescales. Recent advancements, particularly the integration of machine learning (ML), are now bridging this gap, making ab initio accuracy more accessible for larger biomolecular systems [29].

Performance Comparison: AIMD vs. Classical MD

The table below summarizes quantitative performance data for AIMD and classical MD across key system types, highlighting the trade-off between accuracy and computational expense.

Table 1: Performance Comparison for Proton Transfer and Charged Fluids

| System & Property | AIMD Approach | Classical MD Approach | Key Performance Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Proton Diffusion in Water (Structural Diffusion) | AIMD (DFT); CPMD [38] | Classical MD with fixed bonds [38] | AIMD captures Grotthuss mechanism (transfer ~200 fs); Classical MD restricted to slower vehicular diffusion |

| Gramicidin A Channel (Proton Conductance) | N/A (Limited by scale/time) | CHARMM with stochastic proton hops [38] | Classical MD with specialized hop algorithm estimated conductance reasonably vs. experiment [38] |

| Ionic Liquids (ILs) (Transport Properties) | AIMD (DFT) [39] [40] | Non-polarizable Fixed-Charge FF (e.g., OPLS-AA) [39] | AIMD: Accurate structure & dynamics; Classical MD: Overestimated viscosity, low ionic diffusion [39] |

| Ionic Liquids (ILs) (Polarization Effects) | AIMD (DFT) [40] | Polarizable Force Fields [40] | AIMD and polarizable MD show good agreement in molecular dipole moments; Fixed-charge FFs fail [40] |

| General Protein Dynamics (Energy/Force Accuracy) | AI2BMD (ML-AIMD) [29] | Classical MM Force Fields [29] | AI2BMD MAE: 0.045 kcal mol⁻¹ (energy), 0.078 kcal mol⁻¹ Å⁻¹ (force); MM MAE: 3.198 kcal mol⁻¹ (energy), 8.125 kcal mol⁻¹ Å⁻¹ (force) [29] |

For simulating chemical reactions like proton transfer, AIMD is fundamentally superior as it captures the bond-breaking process. Classical MD requires specialized, often heuristic algorithms to mimic this behavior. For charged fluids, AIMD automatically captures polarization, while classical MD requires more complex polarizable force fields to achieve comparable accuracy, albeit at increased computational cost [39] [40].

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Protocol for AIMD of Proton Transfer in Water

Studying the Grotthuss mechanism of proton transport in water is a canonical application of AIMD [38].

- Software: CP2K is a widely used package for AIMD simulations, offering efficiency for large system sizes [41].

- System Setup: A typical system contains 64-128 water molecules in a cubic simulation box with periodic boundary conditions. The box size is chosen to match the experimental density of water (e.g., ~12.66 Å for 64 molecules) [41].

- DFT Parameters: The BLYP-D3 or SCAN meta-GGA functional is often used. Goedecker-Teter-Hutter (GTH) pseudopotentials model core electrons, and a TZV2P basis set expands the Kohn-Sham orbitals. A high plane-wave cutoff (400-600 Ry) is used for the electron density [41].

- Simulation Run: Dynamics are run in the NVT ensemble using a Nosé-Hoover chain thermostat to maintain temperature (e.g., 300 K or 330 K). A very small timestep (0.5 fs) is required due to the fast proton motions. The orbital transformation (OT) method optimizes the wavefunction at each step with tight SCF convergence (1×10⁻⁷ a.u.) [41].

- Analysis: The trajectory is analyzed to compute proton transfer rates, molecular diffusion coefficients, and hydrogen bond dynamics. The mechanism can be visualized by tracking the formation and dissociation of Zundel (H₅O₂⁺) and Eigen (H₉O₄⁺) ions [38].

Protocol for Classical MD with Stochastic Proton Hopping

When AIMD is infeasible, classical MD can be augmented with algorithms to allow proton hopping.

- Software: This algorithm is implemented in packages like CHARMM [38].

- Theoretical Basis: The method uses a time-scale separation. Standard MD handles solvent rearrangement, while periodic Monte Carlo steps attempt instantaneous proton hops [38].

- Hop Criterion: During the simulation, proton transfer from a donor (e.g., hydronium) to an acceptor (e.g., water) is attempted based on geometric criteria. The hop is accepted or rejected with a probability based on a non-Boltzmann criterion heuristically adjusted to reproduce correct thermodynamics and kinetics [38].

- Parameters: The method requires pre-defined parameters for key residues like Asp, Glu, and His, tuned to match proton diffusion rates in bulk water or pKa values [38].

- Validation: The model is tested on systems like proton diffusion in carbon nanotubes and conductance in the gramicidin A channel to ensure it produces physically reasonable results [38].

Protocol for ML-Driven Ab Initio Accuracy (AI2BMD)

A modern approach uses machine learning to achieve AIMD accuracy at a fraction of the cost.

- Software: AI2BMD is a specialized system for this purpose [29].

- Fragmentation & Training: A generalizable protein is fragmented into small, overlapping units (dipeptides). A comprehensive dataset of these units is generated via AIMD, sampling a wide range of conformations. A graph neural network (ViSNet) is trained on this dataset to predict energy and atomic forces with ab initio accuracy [29].

- Simulation Run: For a new protein, the system is fragmented, and the ML potential (AI2BMD potential) calculates energies and forces at each simulation step. The solvent is typically handled with a polarizable force field like AMOEBA [29].

- Performance: This method reduces computational time by several orders of magnitude compared to DFT, enabling nanosecond-scale simulations of proteins with over 10,000 atoms with ab initio accuracy [29].

The workflow diagram below illustrates the key steps and logical relationships in this ML-enhanced approach.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

This section details key software and computational "reagents" essential for conducting research in this field.

Table 2: Key Software Tools for AIMD and Advanced MD Simulations

| Tool Name | Primary Function | Key Features | License |

|---|---|---|---|

| CP2K [42] [41] | Ab Initio MD | Highly efficient for AIMD of liquids and solids; Supports multiple DFT functionals | Free Open Source (GPL) |

| CHARMM [38] [42] | Classical & Enhanced MD | Implements advanced algorithms like stochastic proton hopping; Scriptable | Proprietary (Academic) |

| AI2BMD [29] | ML-Driven AIMD | Generalizable ab initio accuracy for large proteins (>10k atoms); Uses fragmentation | Research Platform |

| GROMACS [42] [43] | High-Performance MD | Extremely fast classical MD; GPU-accelerated; Supports multiple force fields | Free Open Source (LGPL/GPL) |

| AMBER [42] [43] | Biomolecular MD | Optimized for proteins/NA; Excellent GPU acceleration (PMEMD); Strong free-energy tools | Proprietary (AmberTools is free) |

| NWChem [38] [42] | Computational Chemistry | High-performance QM, MD, QM/MM; Includes Q-HOP proton transfer algorithm | Free Open Source |

| NeuralIL [39] | Neural Network Force Field | ML force field for ionic liquids; AIMD accuracy for structural/dynamic properties | Research Software |

The choice between AIMD and classical MD for simulating proton transfer and charged fluids involves a direct trade-off between chemical accuracy and computational scale. AIMD remains the gold standard for its ability to natively model reactive processes and electronic effects but is often restricted to small systems and short timescales. Classical MD is practical for large-scale biomolecular simulations but requires specialized, system-dependent enhancements to handle bond formation and polarization.

The most promising future direction lies in machine-learning force fields like AI2BMD and NeuralIL [39] [29]. By learning the quantum mechanical potential energy surface from AIMD data, these methods are poised to obliterate the traditional accuracy-scale trade-off, enabling the ab initio-level simulation of large, complex biological and materials systems that were previously out of reach.

Proteins are dynamic entities, and their flexibility is fundamental to function, particularly in the processes of ligand binding and recognition. The longstanding "lock and key" model has been largely supplanted by the concept of induced fit, where both the ligand and the protein receptor undergo mutual conformational changes to form a stable complex [44]. This dynamic nature presents a significant challenge for drug discovery. Many therapeutically promising proteins have been historically classified as "undruggable" because their experimentally determined, ground-state structures lack well-defined pockets suitable for drug binding [45].

Computational methods have emerged as powerful tools to bridge this gap, with molecular dynamics (MD) simulations serving as a "computational microscope" that reveals the continuous motion of biomolecules [29]. These simulations provide a critical avenue for exploring protein dynamics, allowing researchers to observe transient conformational states that are inaccessible through static experimental structures. Among these states are cryptic pockets—druggable sites that do not exist in the ground-state structure but open up transiently due to protein fluctuations [46]. The ability to predict and characterize these cryptic pockets vastly expands the potentially druggable proteome, offering new avenues for targeting proteins currently considered undruggable [46]. This guide focuses on comparing Classical Molecular Dynamics (CMD) with more computationally intensive ab initio methods, providing a framework for selecting the appropriate tool for investigating protein dynamics and cryptic pocket discovery.

MD simulations simulate the physical motions of atoms and molecules over time. The different flavors of MD are primarily distinguished by how they calculate the forces acting on the atoms.

Classical Molecular Dynamics (CMD)

Principles: CMD relies on Newtonian mechanics. The forces acting on each atom are derived from empirical potential energy functions, known as force fields [44]. These force fields are mathematical models that describe the energy of the system as a sum of bonded terms (e.g., bond stretching, angle bending) and non-bonded terms (e.g., van der Waals forces, electrostatic interactions) [44]. The motion of atoms is determined by numerically integrating Newton's equations of motion.

Strengths and Limitations: The primary strength of CMD is its computational efficiency, enabling the simulation of large biomolecular systems (e.g., proteins in explicit solvent) at timescales relevant to biological processes (nanoseconds to microseconds) [16]. However, this speed comes at a cost: the accuracy is limited by the force field. CMD cannot model chemical reactions where bonds are formed or broken, and its accuracy is dependent on the parameterization of the force field [1].

Software Tools: Popular CMD software includes GROMACS (highly efficient for biomolecules), AMBER (specialized for proteins and nucleic acids), and LAMMPS (versatile for materials and soft matter) [44].

2Ab InitioMolecular Dynamics (AIMD)

Principles: AIMD bridges molecular dynamics with quantum mechanics. In AIMD, the forces on the nuclei are calculated "on the fly" from electronic structure calculations, typically using Density Functional Theory (DFT) [16]. This method does not rely on pre-defined force fields.

Strengths and Limitations: The key advantage of AIMD is its chemical accuracy. It can model chemical reactions, electron transfer, and systems where quantum mechanical effects are important [16] [29]. The formidable limitation is its computational expense, which scales poorly with system size (approximately O(N³) for DFT), restricting it to smaller systems (tens of atoms) and shorter timescales (picoseconds) [16].

Machine Learning-Enhanced Dynamics

Emerging Hybrids: To overcome the limitations of both CMD and AIMD, machine learning (ML) force fields are being rapidly developed. These ML force fields are trained on data generated from high-level ab initio calculations but can execute simulations at speeds approaching those of CMD [47] [29]. For instance, the AI2BMD system uses a graph neural network to achieve ab initio accuracy for proteins with over 10,000 atoms, reducing computational time by several orders of magnitude compared to DFT [29]. Another approach, ReaxFF, is a reactive force field parameterized from quantum data, enabling the simulation of bond formation and breaking within a CMD framework [1].

Quantitative Comparison of CMD and AIMD Performance

The choice between CMD and AIMD involves a direct trade-off between computational cost and accuracy. The following tables summarize key performance metrics and application scopes based on recent research.

Table 1: Performance and Accuracy Benchmarks

| Feature | Classical MD (CMD) | Ab Initio MD (AIMD) | Machine Learning MD (AI2BMD) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Force/Energy Calculation | Empirical force fields [44] | Density Functional Theory (DFT) [16] | Machine-learned potential [29] |

| Force MAE (kcal mol⁻¹ Å⁻¹) | ~8.125 [29] | Reference Value | ~1.056 [29] |

| Energy MAE (kcal mol⁻¹ per atom) | ~0.214 [29] | Reference Value | ~7.18 × 10⁻³ [29] |

| Typical System Size | >100,000 atoms [44] | Tens of atoms [16] | >10,000 atoms [29] |

| Typical Simulation Timescale | Nanoseconds to Microseconds [44] | Picoseconds [16] | Nanoseconds [29] |

| Ability to Model Reactions | No (except with reactive FF like ReaxFF) [1] | Yes [16] | Yes [29] |

Table 2: Application Scope for Protein Dynamics and Cryptic Pockets

| Application Area | CMD with Standard FF | AIMD | ML-Enhanced MD (e.g., AI2BMD, ReaxFF) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Large-System Conformational Sampling | Excellent [44] | Not feasible [16] | Good [29] |

| Cryptic Pocket Identification | Good (e.g., with mixed-solvent MD) [45] | Limited by system size/time | Emerging, high potential [46] |

| Ligand Binding with Electronic Effects | Poor | Excellent [16] | Excellent [29] |