A Researcher's Guide: Calculating Diffusion Coefficients in LAMMPS, GROMACS, and AMBER

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and scientists on calculating diffusion coefficients using major molecular dynamics software: LAMMPS, GROMACS, and AMBER.

A Researcher's Guide: Calculating Diffusion Coefficients in LAMMPS, GROMACS, and AMBER

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and scientists on calculating diffusion coefficients using major molecular dynamics software: LAMMPS, GROMACS, and AMBER. It covers foundational theory, practical implementation of Mean-Squared Displacement (MSD) and Velocity Autocorrelation Function (VACF) methods, troubleshooting for convergence issues, and comparative analysis of software performance. Special emphasis is placed on protocols for biomolecular systems, force field selection, and uncertainty estimation to support reliable property prediction in drug development and materials research.

Understanding Diffusion Fundamentals and Molecular Dynamics Principles

In the study of molecular dynamics (MD), understanding the random motion of particles is fundamental to characterizing transport phenomena in systems ranging from simple liquids to complex biological environments. The mean-squared displacement (MSD) serves as a direct measure of this motion, quantifying the spatial extent of a particle's random walk over time [1]. The Einstein Relation provides the critical link between this observable and the self-diffusion coefficient (D), a key property in predicting molecular mobility [2] [3]. For researchers using simulation packages like LAMMPS, GROMACS, and AMBER, mastering the application of this relation is essential for obtaining accurate diffusion data from their trajectories. This guide details the theoretical foundation and provides actionable, software-specific protocols for reliable calculation of diffusion coefficients.

## 1. Theoretical Foundation of the Einstein Relation

### 1.1. Definition of Mean-Squared Displacement (MSD)

The MSD measures the average squared distance a particle travels over a specific time interval. For a set of ( N ) particles in three dimensions, it is defined statistically as: [ \text{MSD}(t) = \langle | \mathbf{r}(t) - \mathbf{r}(0) |^2 \rangle = \frac{1}{N} \sum_{i=1}^{N} | \mathbf{r}^{(i)}(t) - \mathbf{r}^{(i)}(0) |^2 ] where ( \mathbf{r}(t) ) is the position of a particle at time ( t ), and the angle brackets ( \langle \cdots \rangle ) denote an ensemble average over all particles and time origins [1]. In essence, the MSD captures how much a system "explores" space through random motion.

### 1.2. The Einstein Relation and the Diffusion Coefficient

For a particle undergoing normal, diffusive motion in a homogeneous medium, the MSD grows linearly with time. The Einstein Relation formalizes this observation: [ \lim{t \to \infty} \text{MSD}(t) = 2n D t ] where ( n ) is the dimensionality of the diffusion (e.g., 1, 2, or 3) and ( D ) is the self-diffusion coefficient [1] [3]. In the most common case of three-dimensional diffusion, this simplifies to: [ D = \frac{1}{6} \lim{t \to \infty} \frac{d}{dt} \text{MSD}(t) ] Therefore, the diffusion coefficient is calculated as one-sixth of the slope of the linear portion of the MSD-versus-time curve [4] [3]. The relation arises from solving the diffusion equation, where the Green's function for particle spreading leads directly to this linear dependence [2].

## 2. Practical Computation in MD Software Packages

The following table summarizes the core commands and methods used in major MD software packages to compute the diffusion coefficient via the Einstein Relation.

Table 1: Implementation of Diffusion Coefficient Calculation in MD Software

| Software | Core Command / Module | Primary Method | Key Output for Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| LAMMPS | compute msd |

MSD calculation via fix vector/ variable slope [5] |

MSD time series for linear fitting |

| GROMACS | gmx msd |

Direct MSD calculation using Einstein relation [6] | MSD plotted against time for slope calculation |

| AMBER | MD Properties → MSD in AMSmovie [4] |

MSD analysis of trajectory with automated slope fitting | MSD plot and calculated ( D ) value (( \text{slope}/6 )) [4] |

| MDAnalysis | EinsteinMSD class [7] |

FFT-based or windowed MSD algorithm | results.timeseries for linear regression [7] |

### 2.1. Critical Preprocessing Step: Trajectory Unwrapping

A common and critical pitfall in MSD analysis is the use of "wrapped" trajectories, where atomic coordinates are constrained within the primary simulation box by periodic boundary conditions (PBC). Using wrapped trajectories artificially lowers the MSD and leads to severely underestimated diffusion coefficients.

- Unwrapped Trajectories: For accurate MSD, you must use unwrapped trajectories that track a particle's true path across periodic images [7] [8].

- How to Achieve This:

- GROMACS: Use

gmx trjconv -pbc nojumpto create an unwrapped trajectory [7]. - LAMMPS: The

compute msdcommand automatically uses unwrapped coordinates if available [8]. - General Best Practice: For simulations in the NPT ensemble, special care is needed as box fluctuations complicate unwrapping. The Toroidal-View-Preserving (TOR) scheme is recommended for accurate unwrapping and diffusion calculation in NPT simulations [8].

- GROMACS: Use

## 3. Step-by-Step Analysis Protocol

### 3.1. Workflow for MSD Analysis and Diffusion Calculation

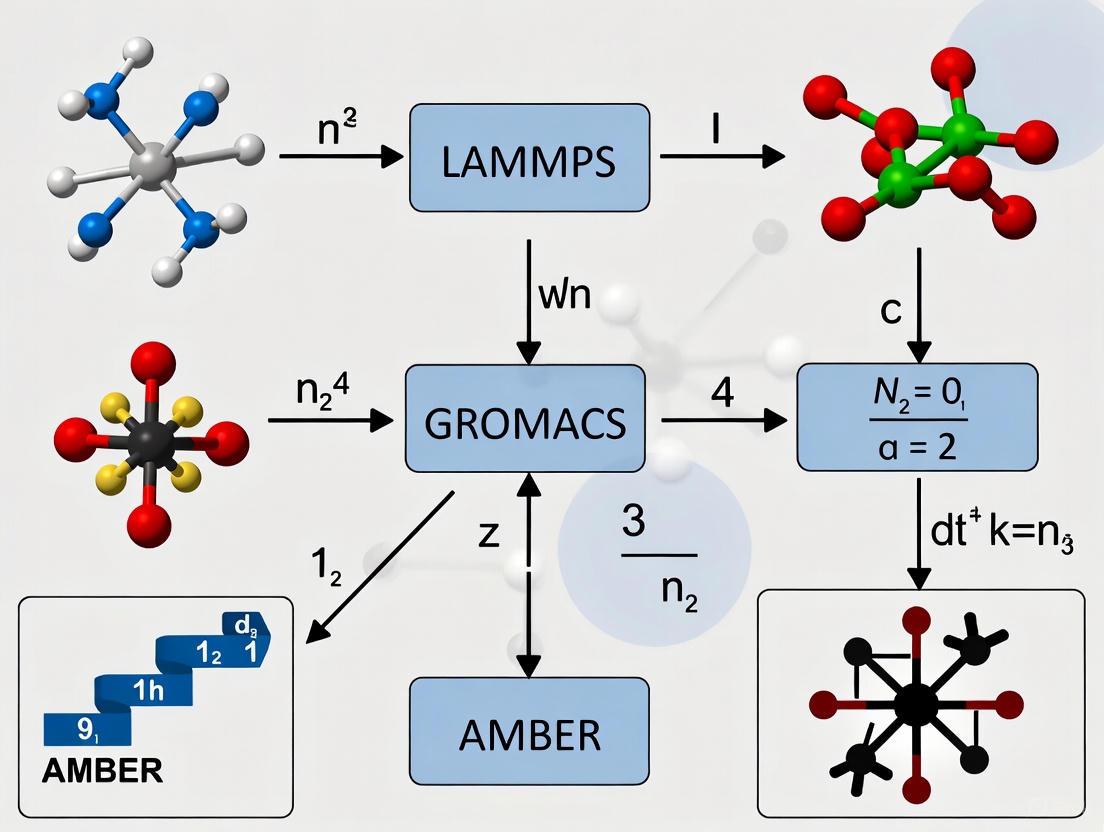

The following diagram illustrates the end-to-end workflow for calculating a diffusion coefficient from an MD simulation, highlighting key decision points.

### 3.2. Protocol for Linear Fitting and Obtaining D

Once a linear MSD regime is identified, follow this protocol to extract the diffusion coefficient.

- Select the Linear Regime: Choose a time range ( [t{start}, t{end}] ) where the MSD plot is linear on a linear-scale graph. Avoid the short-time ballistic regime (( \text{MSD} \propto t^2 )) and the long-time plateau where statistics are poor [3]. A log-log plot can help identify the linear regime, which should have a slope of 1 [7].

- Perform Linear Regression: Use a robust fitting method (e.g., least-squares) on the MSD data within the selected range to obtain the slope ( \frac{d}{dt}\text{MSD}(t) ).

- Calculate D: For 3D diffusion, compute ( D = \frac{\text{slope}}{6} ). The slope has units of Ų/ps or cm²/s, so ensure your units for ( D ) are consistent.

- Estimate Error: Report the standard error or confidence interval from the linear regression. For better statistics, calculate the MSD by averaging over multiple, shorter trajectories rather than one long run [2] [3].

Table 2: Troubleshooting Common Issues in MSD Analysis

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| MSD curve is not linear | Simulation too short; system not in diffusive regime [3] | Extend simulation time; use log-log plot to verify slope=1 [7] |

| High noise in MSD at long times | Poor statistics from insufficient averaging [3] | Increase number of particles averaged; use multiple time origins |

| Diffusion coefficient is too low | Use of wrapped coordinates [7] | Recalculate MSD with unwrapped trajectories |

| D depends on system size | Finite-size effects from hydrodynamic interactions [3] | Apply Yeh-Hummer correction: ( D\text{corr} = D\text{PBC} + \frac{2.84 k_B T}{6 \pi \eta L} ) [3] |

Table 3: Key Computational Tools for Diffusion Studies

| Resource / Tool | Function in Analysis | Availability / Example |

|---|---|---|

| Unwrapping Scripts | Converts wrapped trajectories to unwrapped for correct MSD | GROMACS trjconv, LAMMPS dump modified |

| MSD Analysis Codes | Calculates MSD from trajectory files | gmx msd (GROMACS), compute msd (LAMMPS), EinsteinMSD (MDAnalysis) [7] |

| Linear Regression Tools | Fits linear slope to MSD data | scipy.stats.linregress in Python, linear fit in Origin/Excel |

| Visualization Software | Plots MSD to identify linear regime and assess quality | Matplotlib (Python), Grace (xmgr), GROMACS built-in tools |

| Finite-Size Correction | Corrects for system size artifact in diffusion constant | Yeh-Hummer equation [3] |

## 5. Advanced Considerations and Validation

### 5.1. The Velocity Autocorrelation Function (VACF) Method

An alternative to the MSD method is calculating the diffusion coefficient from the integral of the Velocity Autocorrelation Function (VACF) using the Green-Kubo relation:

[

D = \frac{1}{3} \int_0^{\infty} \langle \mathbf{v}(0) \cdot \mathbf{v}(t) \rangle dt

]

This method is also implemented in MD packages (e.g., compute vacf in LAMMPS [5], VACF analysis in AMSmovie [4]). The result should agree with the MSD-derived value, providing a valuable cross-validation [4]. The VACF method can be more sensitive to statistical noise and may require higher-frequency trajectory sampling.

### 5.2. Beyond Normal Diffusion

The linear MSD( (t) ) relation assumes normal diffusion. However, in complex systems like glass-forming liquids or crowded cellular environments, anomalous diffusion may occur, where ( \text{MSD}(t) \propto t^{\alpha} ) with ( \alpha \neq 1 ) [9]. A value ( \alpha < 1 ) indicates subdiffusion, often resulting from molecular crowding or trapping. Analyzing the exponent ( \alpha ) itself can provide insights into the system's dynamics and microstructure [9].

The Einstein Relation provides a powerful and direct link between the computationally accessible mean-squared displacement and the physically significant diffusion coefficient. By following the protocols outlined herein—particularly ensuring the use of unwrapped trajectories, carefully identifying the linear diffusive regime, and accounting for finite-size effects—researchers can obtain reliable and accurate diffusion data from their molecular dynamics simulations in LAMMPS, GROMACS, and AMBER. This methodology is a cornerstone for understanding mass transport in materials science, pharmaceutical development, and chemical engineering.

The Green-Kubo relations provide the exact mathematical framework for calculating transport coefficients from the microscopic dynamics of a system at equilibrium. This linear response theory, established by Melville S. Green in 1954 and Ryogo Kubo in 1957, connects macroscopic transport properties to the time-integral of equilibrium time correlation functions of their corresponding microscopic fluxes [10]. The general form of the Green-Kubo relation for a transport coefficient γ is given by:

γ = ∫₀^∞ ⟨Ȧ(t)Ȧ(0)⟩ dt

This formalism reveals a profound physical insight: the relaxations resulting from random fluctuations at equilibrium are fundamentally indistinguishable from those arising from external perturbations in the linear response regime [10]. For the specific case of diffusion, the Green-Kubo relation states that the *self-diffusion coefficient can be calculated from the velocity autocorrelation function (VACF) [11]:

D_A = 1/3 ∫₀^∞ ⟨v_i(t) · v_i(0)⟩ dt

The VACF itself, C_v(t) = ⟨v_i(t) · v_i(0)⟩, measures how a particle's velocity correlates with itself over time, providing crucial insights into the dynamics and interactions within the system. In molecular dynamics simulations, this formalism allows for the calculation of transport coefficients without perturbing the system out of equilibrium, making it particularly valuable for studying delicate systems where nonequilibrium methods might introduce artifacts [10].

Theoretical Foundation of VACF

Mathematical Definition and Normalization

The velocity autocorrelation function is formally defined for a system of particles as the normalized time correlation of atomic velocities. For a selected set of atoms, the VACF is computed as [12]:

VACF(t) = [∑ᵢ ⟨m_i v_i(t) · v_i(0)⟩] / [∑ᵢ ⟨m_i v_i²⟩]

This expression is normalized to unity at t=0, where the numerator represents the mass-weighted correlation function of velocities, and the denominator serves as the normalization constant. The angle brackets ⟨···⟩ denote an ensemble average over time origins and selected atoms. In practical molecular dynamics simulations, this average is implemented as a time average over the trajectory [12]:

⟨m_i v_i(t) · v_i(0)⟩ = 1/(t_max - t) ∑_{t'=0}^{t_max-t} v_i(t' + t) · v_i(t')

This formulation highlights that for each time difference t, all trajectory pairs separated by t contribute to the average, thus improving statistical sampling. The mass-weighting accounts for the different inertial contributions of atoms of varying masses, making the VACF a physically meaningful quantity for systems with multiple atomic species.

Physical Interpretation of VACF Decay

The temporal decay of the VACF reveals fundamental information about the dynamics and interactions within the system. In an ideal gas without collisions, the VACF would remain constant, as velocities would not change over time. In real systems, however, the VACF decays due to collisions and interactions with neighboring particles. The specific pattern of decay provides insights into the nature of these interactions [11]:

- In dense fluids, the VACF typically shows a rapid initial decay, often becoming negative before eventually converging to zero.

- The negative region indicates back-scattering, where particles collide with their neighbors and reverse direction.

- The long-time tail of the VACF follows a power-law decay (

t^{-3/2}) due to hydrodynamic effects, as predicted by mode-coupling theory.

The connection between VACF and diffusion emerges naturally from this interpretation: a slowly decaying VACF indicates persistent motion and high diffusivity, while rapid decay signifies strong scattering and limited diffusion.

Computational Implementation in MD Packages

VACF Calculation Protocols

Table 1: VACF Implementation in Major MD Software Packages

| Software | Command/Tool | Key Parameters | Output |

|---|---|---|---|

| GROMACS | gmx velacc |

-mol, -acflen, -normalize |

VACF data, correlation time |

| QuantumATK | VelocityAutocorrelation class |

atom_selection, start_time, end_time, time_resolution |

Normalized VACF values, times |

| MDSuite | Integrated VACF calculator | Species selection, correlation length, statistical settings | VACF, diffusion coefficient, errors |

GROMACS-Specific Protocol

The GROMACS implementation offers the gmx velacc module for calculating velocity autocorrelation functions. The typical workflow involves:

Trajectory Preparation: Ensure your trajectory file contains velocity information, which may require enabling velocity output in the production simulation.

Command Execution:

Key Parameters:

-acflen: Sets the time lag for correlation function calculation (should be ≤ N/2 where N is the number of frames) [11]-normalize: Normalizes the ACF to 1 at t=0-mol: Calculates correlation per molecule instead of per atom

Output Interpretation: The output file (

vacf.xvg) contains two columns: time and the corresponding VACF value. The integration of this function yields the diffusion coefficient according to the Green-Kubo relation [11].

QuantumATK-Specific Protocol

For QuantumATK users, the VelocityAutocorrelation class provides a Python-based approach to VACF calculation [12]:

The atom_selection parameter is particularly useful for studying species-specific dynamics in multicomponent systems, accepting element types, tag names, or atomic indices [12].

LAMMPS and AMBER Considerations

While not explicitly detailed in the search results, LAMMPS typically calculates VACF using the compute vacf command, followed by integration for diffusion coefficients. AMBER users often employ the cpptraj module for correlation function analysis. For both packages, the general theoretical principles and statistical considerations discussed herein remain directly applicable.

Integration with Diffusion Coefficient Calculation

From VACF to Diffusion Coefficient

The Green-Kubo relation provides the fundamental connection between VACF and the self-diffusion coefficient [11]:

D = (1/3) ∫₀^∞ ⟨v_i(t) · v_i(0)⟩ dt

In practice, this integration is performed numerically from the computed VACF data. The implementation involves:

- Numerical Integration: Using methods like the trapezoidal rule to integrate the VACF up to a maximum time.

- Time Step Consideration: Ensuring the integration time step matches the VACF calculation interval.

- Convergence Assessment: Monitoring the cumulative integral as a function of the upper limit to determine when sufficient sampling has been achieved.

Table 2: Comparison of Diffusion Calculation Methods

| Method | Theoretical Basis | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Green-Kubo (VACF) | Fluctuation-dissipation theorem | Works for equilibrium systems; No external perturbation | Long correlation times needed; Statistical noise |

| Einstein (MSD) | Random walk theory | More intuitive; Often better convergence | Requires linear MSD regime; Anisotropy issues |

It's important to note that while the VACF-based approach is theoretically rigorous, the mean square displacement (MSD) method often converges more rapidly, though both should yield identical diffusion coefficients in the limit of infinite sampling [11].

Workflow Visualization

Figure 1: Green-Kubo Workflow for Diffusion Calculation from VACF

Practical Considerations and Best Practices

Statistical Accuracy and Convergence

Accurate VACF calculation requires careful attention to statistical sampling. Several methods can improve convergence [11]:

Time Lag Selection: Restrict correlation function calculation to MΔt where M ≤ N/2 (N = number of frames) to maintain uniform statistical accuracy across all time points [11]:

C_f(jΔt) = (1/M) ∑_{i=0}^{N-1-M} f(iΔt)f((i+j)Δt)Block Averaging: Use time origins spaced by at least the time lag to reduce correlation between origins:

C_f(jΔt) = (1/k) ∑_{i=0}^{k-1} f(iMΔt)f((iM+j)Δt)Trajectory Length: Ensure simulation length is sufficient to capture the complete decay of VACF, typically 10-100 times the correlation time of interest.

Memory and Computational Efficiency

The direct calculation of ACFs has a computational cost proportional to N², which can become prohibitive for long trajectories [11]. Modern implementations address this through:

- Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) Methods: Utilizing convolution theorems to reduce computational complexity [11].

- Data Management Tools: Software like MDSuite uses optimized database structures (HDF5 format) to handle large trajectory data efficiently [13].

- Parallelization and GPU Acceleration: Frameworks like TensorFlow in MDSuite enable accelerated computation on modern hardware [13].

Advanced Applications and Extensions

Beyond Self-Diffusion: Other Transport Properties

The Green-Kubo formalism extends beyond self-diffusion to various transport coefficients [10]:

- Shear Viscosity:

η = (V/kT) ∫₀^∞ ⟨P_xy(t)P_xy(0)⟩ dtwhere P_xy is the off-diagonal element of the stress tensor. - Thermal Conductivity: Relates to the heat current autocorrelation function.

- Electrical Conductivity: Derived from the current autocorrelation function.

These applications follow the same fundamental pattern: a transport coefficient equals the time integral of the autocorrelation function of the corresponding flux.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for VACF Analysis

| Tool/Software | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| GROMACS | MD simulation & analysis | Biomolecular systems, materials science |

| LAMMPS | MD simulation | Materials science, nanosystems |

| AMBER | MD simulation | Biomolecular systems, drug design |

| QuantumATK | MD & analysis | Nanoscale materials, semiconductors |

| MDSuite | Post-processing | Multi-simulation analysis, database management |

| HDF5 Format | Data storage | Efficient trajectory handling [13] |

| SQL Database | Results management | Metadata and parameter storage [13] |

Validation and Error Analysis

Convergence Testing

Validating the convergence of Green-Kubo calculations is essential for reliable results. Recommended practices include [11]:

- Cumulative Integration Monitoring: Plot the diffusion coefficient as a function of the upper integration limit to identify plateaus.

- Block Analysis: Divide the trajectory into multiple blocks and compute the standard deviation of results across blocks.

- Comparison with MSD: Verify that the diffusion coefficient from VACF integration agrees with the MSD-based calculation.

It's crucial to note Allen & Tildesley's warning that the long-time contribution to the velocity ACF cannot be ignored, despite the common belief that VACF converges faster than MSD [11].

Common sources of error in VACF-based diffusion calculations include:

- Insufficient Sampling: The most significant challenge, particularly for slow diffusion processes.

- Time Step Effects: Improvised correlation interval may alias rapid dynamics.

- System Size Effects: Finite-size corrections may be necessary for small simulation boxes.

- Force Field Accuracy: The quality of interatomic potentials fundamentally limits result reliability.

The implementation of comprehensive data management systems, such as the SQL database in MDSuite that stores computation parameters alongside results, facilitates reproducibility and error tracking [13].

The velocity autocorrelation function serves as the critical link between microscopic atomic motions and macroscopic transport properties within the Green-Kubo framework. Its implementation across major molecular dynamics packages provides researchers with a powerful tool for extracting diffusion coefficients from equilibrium simulations. While the method demands careful attention to statistical sampling and convergence, it remains theoretically rigorous and widely applicable across chemistry, materials science, and biological domains. The continued development of computational tools and post-processing frameworks ensures that Green-Kubo analysis will maintain its relevance as molecular simulations address increasingly complex systems in drug development and advanced materials design.

In the realms of computational biology and pharmaceutical research, the concept of "diffusion" holds dual significance, both fundamentally important yet distinct in application. Traditionally, diffusion refers to the physical process of particle motion, a property quantified by the diffusion coefficient, which is crucial for understanding molecular behavior in solutions, cellular environments, and engineered materials. Concurrently, Diffusion Models (DMs), a class of generative artificial intelligence inspired by non-equilibrium statistical physics, have emerged as transformative tools for de novo molecular design. This article explores the significance of both concepts, framing them within the context of biomolecular research using common simulation packages like LAMMPS, GROMACS, and AMBER, and providing detailed protocols for their application in drug development.

Calculating Diffusion Coefficients in Molecular Dynamics

The diffusion coefficient (D) is a key property describing the tendency of particles to spread out over time. In Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations with packages like LAMMPS and GROMACS, it is primarily calculated using two methods: Mean-Squared Displacement (MSD) and the Velocity Autocorrelation Function (VACF).

Theoretical Foundations

The Einstein relation connects MSD to the diffusion coefficient. For 3-dimensional diffusion, the relationship is: $$D = \frac{1}{6t} \langle(r(t) - r(0))^{2}\rangle$$ Here, $\langle(r(t) - r(0))^{2}\rangle$ represents the MSD, the average squared distance particles have moved after time ( t ) [5] [14]. In this context, the slope of the MSD versus time is proportional to D.

Alternatively, the diffusion coefficient can be obtained from the time-integral of the VACF [5]. The choice between MSD and VACF can depend on the specific system and the desired computational efficiency.

Protocols for Calculating Diffusion Coefficients

Protocol: Calculating D via MSD in GROMACS

The gmx msd command is the standard tool for this calculation [15].

- Command Syntax:

Parameter Explanation:

-f: Input trajectory file.-s: Input topology file.-n: Index file specifying the group of atoms to analyze.-o: Output file for the MSD data.-beginfitand-endfit: Define the time range (in ps, unless-tuis specified) for the linear regression to calculate the slope of the MSD. The defaults are 10% and 90% of the total time, respectively [15] [14].-trestart: Time interval (ps) for setting new reference points in the trajectory for the MSD calculation. A shorter interval improves statistics but increases computational cost [14].-tu ns: Sets the time unit for output to nanoseconds.-type z: Use this to calculate the diffusion coefficient only in the z-direction (then ( D = \frac{1}{2} \times slope ) ).

Data Interpretation:

- GROMACS performs a least-squares fit of a line (D*t + c) to the MSD(t) curve within the specified

-beginfitto-endfitrange [15]. - The diffusion coefficient is derived from the slope of this line. For 3D diffusion, ( D = \frac{text{slope}}{6} ). For 1D (e.g.,

-type z), ( D = \frac{text{slope}}{2} ) [14]. - Critical Step - Selecting the Linear Region: The initial ballistic regime (very steep slope) and the long-time region with poor statistics (noisy, non-linear) should be excluded from the fit. The optimal region is the smooth, linear section in the middle of the plot [14]. Visually inspect the MSD plot to confirm the fitting region is appropriate. An example of a proper MSD plot is below.

- GROMACS performs a least-squares fit of a line (D*t + c) to the MSD(t) curve within the specified

Protocol: Calculating D in LAMMPS

LAMMPS offers two primary methods for calculating diffusion coefficients [5].

Using the

compute msdCommand:- This compute calculates the MSD for a group of atoms.

- The

fix ave/timecommand can be used to accumulate the MSD values over time. - The

variable slopefunction can then perform a linear fit to the MSD versus time data to extract the slope and, consequently, the diffusion coefficient.

Using the

compute vacfCommand:- This compute calculates the VACF.

- Similar to the MSD method,

fix ave/timecan accumulate the VACF values. - The

variable trapfunction can time-integrate the VACF, which is proportional to D.

A typical LAMMPS script snippet would include:

This computes the MSD, writes the data, and calculates D by fitting the entire MSD curve. The index [4] in c_myMSD[4] typically corresponds to the total MSD.

Cross-Platform Validation and Considerations

A critical lesson from studies like the SAMPL5 blind prediction challenge is that seemingly identical simulations run with different MD engines (GROMACS, AMBER, LAMMPS, DESMOND) can yield different results [16]. Discrepancies can arise from subtle differences in default parameters, such as the treatment of long-range electrostatics or even the value of Coulomb's constant [16]. Therefore, for meaningful comparisons, it is vital to ensure parameter consistency across platforms rather than relying on program-specific defaults. Tools like ParmEd and InterMol were developed to automate conversion and validate the equivalence of input files and energies between these different simulation programs [16].

Table 1: Key Software for Diffusion Coefficient Calculation and Cross-Platform Validation.

| Software / Tool | Primary Function | Relevance to Diffusion |

|---|---|---|

| GROMACS | Molecular Dynamics Simulator | gmx msd command for calculating diffusion from MSD [15]. |

| LAMMPS | Molecular Dynamics Simulator | compute msd and compute vacf commands for calculating diffusion [5]. |

| AMBER | Molecular Dynamics Simulator | Suite of tools for MD simulation and analysis, including diffusion calculation. |

| ParmEd | Parameter File Converter | Bridges AMBER, GROMACS, CHARMM, and OpenMM formats to ensure consistency [16]. |

| InterMol | Parameter File Converter | Converts between GROMACS, LAMMPS, and DESMOND file formats [16]. |

The Rise of Generative Diffusion Models in Drug Discovery

Generative AI, particularly Diffusion Models (DMs), is revolutionizing drug discovery by enabling the exploration of the vast chemical space, estimated to contain up to (10^{60}) drug-like molecules [17]. DMs have surpassed earlier generative models like VAEs and GANs in generating high-quality, diverse molecular structures [18] [17].

How Diffusion Models Work

Inspired by non-equilibrium statistical physics, DMs perform a two-step process [18]:

- Forward Diffusion: Noise is gradually added to an initial data sample (e.g., a molecular structure) over a series of steps until it becomes pure noise.

- Reverse Diffusion: A neural network is trained to learn the reverse of this process, iteratively denoising pure noise to generate new, valid data samples that match the original data distribution.

This process can be applied to various molecular representations, including 1D (SMILES strings), 2D (molecular graphs), and 3D (atomic coordinates/point clouds) [18]. For biomolecular applications, 3D methods that are roto-translationally equivariant (respecting the physical laws of geometry) are particularly powerful [18].

Application Note: Target-Aware Small Molecule Generation

A primary application of DMs in pharmaceuticals is structure-based drug design, generating novel small molecules (ligands) that fit into a specific protein's binding pocket [18] [17].

- Objective: Generate a novel, synthetically accessible small molecule ligand with high predicted binding affinity for a target protein.

- Method: Use a target-aware 3D diffusion model. The model is conditioned on the 3D structure of the target protein pocket, guiding the generation of ligands that are geometrically and chemically complementary [18].

- Workflow:

- Input: 3D coordinates of the target protein binding pocket.

- Generation: The DM generates 3D atomic coordinates and atom types for a new ligand within the pocket.

- Output: A set of generated candidate molecules.

- Validation: Candidates are checked for validity, stability, and novelty. Their binding affinity is predicted via molecular docking or scoring functions, and the most promising leads are selected for in vitro testing [18] [17].

Application Note: Therapeutic Peptide Generation

DMs are also applied to the de novo design of therapeutic peptides, which are valuable for targeting protein-protein interactions often considered "undruggable" by small molecules [17].

- Objective: Generate a novel peptide sequence that folds into a stable structure and exhibits a desired biological function (e.g., antagonism) with low immunogenicity.

- Method: Use a DM trained on databases of functional peptides. The generation can operate on sequence space (amino acid sequences) or structural space (3D peptide conformations) [17].

- Workflow:

- The DM generates candidate peptide sequences or structures.

- Candidates are filtered and prioritized using predictive models for stability (against proteolysis), folding, and affinity.

- Top candidates are synthesized and tested experimentally in biochemical or cell-based assays [17].

Table 2: Comparison of DM Applications for Different Therapeutic Modalities.

| Aspect | Small Molecule Generation | Therapeutic Peptide Generation |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Structure-based design; generating pocket-fitting ligands [17]. | Generating functional sequences and stable structures [17]. |

| Key Challenges | Ensuring chemical synthesizability and favorable pharmacokinetics [17]. | Achieving biological stability against proteolysis, proper folding, and low immunogenicity [17]. |

| Common Hurdles | Scarcity of high-quality experimental data; reliance on imperfect scoring functions; need for experimental validation [18] [17]. |

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Software Solutions for Diffusion Research.

| Item / Resource | Type | Function / Application |

|---|---|---|

| GROMACS | MD Software | Calculate diffusion coefficients from MD trajectories via the gmx msd protocol [15]. |

| LAMMPS | MD Software | Calculate diffusion coefficients using compute msd or compute vacf [5]. |

| AMBER | MD Software | Suite for biomolecular simulation, including dynamics and analysis. |

| QM9, GEOM-Drugs | Benchmark Datasets | Curated datasets of 3D molecular structures for training and evaluating generative DMs [18]. |

| CrossDocked2020 | Benchmark Dataset | Dataset of protein-ligand poses for training and benchmarking target-aware molecular DMs [18]. |

| ParmEd / InterMol | Conversion Toolkits | Validate and convert force fields and coordinates between different MD simulation packages to ensure result consistency [16]. |

The concept of diffusion is pivotal to biomolecular and pharmaceutical research on multiple fronts. The accurate calculation of physical diffusion coefficients using standardized protocols in MD software like GROMACS and LAMMPS remains essential for understanding molecular dynamics and interactions. Simultaneously, the advent of generative diffusion models represents a paradigm shift, offering an unprecedented ability to design novel therapeutics computationally. As both MD simulation and generative AI continue to advance, their synergy promises to accelerate the drug discovery process, moving from slow exploration to the on-demand engineering of novel, effective therapies. Bridging the gaps in data quality, model interpretability, and physical realism will be key to fully unlocking this potential.

Molecular Dynamics as a Tool for Studying Molecular Transport

Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulation has become an indispensable tool for studying molecular transport processes at the atomic scale, providing insights that are often challenging to obtain through experimental methods alone. MD simulations enable researchers to investigate fundamental phenomena such as diffusion, viscosity, and conduction by tracking the temporal evolution of a system of atoms and molecules under the influence of interatomic potentials. The ability to compute transport properties like diffusion coefficients from MD trajectories has made this computational approach particularly valuable across diverse fields including materials science, drug development, and membrane technology [19] [20]. For researchers working with popular MD packages like LAMMPS, GROMACS, and AMBER, understanding the protocols for extracting accurate transport properties is essential for advancing research in molecular-level processes.

The foundation of transport property calculation lies in statistical mechanics, where macroscopic observables are derived from microscopic behavior. As Maginn et al. (2018) noted, transport properties are among the most requested features in molecular analysis tools, highlighting their importance in computational research [21]. This application note provides detailed methodologies for calculating diffusion coefficients across different MD platforms, structured tables for comparing quantitative data, and visual workflows to guide researchers in implementing these techniques effectively within their thesis research frameworks.

Fundamental Methods for Calculating Diffusion Coefficients

Theoretical Framework

The diffusion coefficient (D) quantifies the rate at which particles spread through a medium due to random thermal motion. In MD simulations, two primary approaches are used to compute diffusion coefficients: the Mean-Squared Displacement (MSD) method based on the Einstein relation, and the Velocity Autocorrelation Function (VACF) method based on the Green-Kubo formalism [5] [4].

The MSD approach derives the diffusion coefficient from the slope of the mean-squared displacement versus time plot, where the MSD is defined as:

[MSD(t) = \langle [\textbf{r}(0) - \textbf{r}(t)]^2 \rangle]

The diffusion coefficient is then calculated as:

[D = \frac{\textrm{slope(MSD)}}{6} \quad \text{(for 3D systems)}]

Alternatively, the VACF method calculates the diffusion coefficient through the time integral of the velocity autocorrelation function:

[D = \frac{1}{3} \int{t=0}^{t=t{max}} \langle \textbf{v}(0) \cdot \textbf{v}(t) \rangle \rm{d}t]

Table 1: Comparison of Methods for Calculating Diffusion Coefficients

| Method | Fundamental Relation | Advantages | Limitations | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean-Squared Displacement (MSD) | (D = \frac{\textrm{slope(MSD)}}{6}) | Intuitive physical interpretation; Simple implementation [4] | Requires linear regime; Sensitive to trajectory length [4] [22] | Bulk fluids; Ion transport in solids [19] |

| Velocity Autocorrelation Function (VACF) | (D = \frac{1}{3} \int{0}^{t{max}} \langle \textbf{v}(0) \cdot \textbf{v}(t) \rangle \rm{d}t) | Better for shorter trajectories; Provides vibrational insights [5] [21] | Requires high-frequency velocity sampling; More complex implementation [4] | Complex fluids; Systems with confined diffusion [21] |

Practical Considerations for Accurate Calculations

Regardless of the method chosen, several critical factors must be considered to obtain reliable diffusion coefficients. The simulation must be sufficiently long to observe the transition from subdiffusive to diffusive behavior, as shorter trajectories may not capture the true linear regime of the MSD [19]. Finite-size effects can significantly influence results, particularly in smaller simulation cells; thus, performing simulations with progressively larger supercells and extrapolating to the "infinite supercell" limit is recommended [4].

Proper equilibration is essential before production runs, as non-equilibrated systems can yield inaccurate transport properties. Various equilibration protocols exist, including conventional annealing cycles and more efficient ultrafast methods that can be up to 600% more efficient than lean approaches [23]. Additionally, the choice of time origin and fitting range for MSD analysis significantly impacts results, with recommendations to start fitting at 10% and end at 90% of the trajectory duration unless manually specified [15].

Experimental Protocols and Implementation

Generalized Workflow for Diffusion Coefficient Calculation

LAMMPS-Specific Protocol

System Preparation and Equilibration:

- Structure Building: Import coordinates from CIF files or use the built-in lattice command for crystalline materials [4].

- Force Field Selection: Apply appropriate potentials (e.g., ReaxFF for lithium-sulfur systems [4] or EAM for metals [22]).

- Energy Minimization: Use the

minimizecommand with stylecgorhftnto relieve bad contacts. - Equilibration Protocol:

- NVT ensemble: Run for 50-100 ps at target temperature using Nosé-Hoover thermostat

- NPT ensemble: Run for 50-100 ps at target temperature and pressure using Nosé-Hoover barostat

Production Simulation:

- Run Parameters: Execute extended simulation (nanoseconds to microseconds) in NVE or NPT ensemble with trajectory saving every 100-1000 steps [4].

- MSD Calculation: Use

compute msdcommand to calculate mean-squared displacement, specifying the atom group of interest [5]. - VACF Calculation: Use

compute vacfcommand for velocity autocorrelation function analysis [5].

Analysis:

- Extract MSD values using

fix vectorand perform linear fit usingvariable slopefunction [5]. - For VACF, integrate using

variable trapfunction [5]. - Calculate D = slope(MSD)/6 or D = integral(VACF)/3.

GROMACS-Specific Protocol

System Preparation:

- Structure Files: Prepare protein topology (.top) and structure (.gro) files using

pdb2gmx. - Solvation: Add solvent using

gmx solvateand ions usinggmx genion. - Energy Minimization: Run

gmx mdrunon minimization input (.mdp) file with steepest descent algorithm.

Equilibration and Production:

- NVT Equilibration: Run with position restraints on heavy atoms for 50-100 ps.

- NPT Equilibration: Run with position restraints for 50-100 ps.

- Production MD: Execute extended simulation without restraints.

MSD Analysis:

- Use

gmx msdwith appropriate options: - Key parameters:

-beginfitand-endfitspecify the fitting range (as percentage of total time) [15]. - For molecular diffusion, use

-molflag to calculate MSD for individual molecules [15].

AMBER/MDAnalysis Protocol

System Preparation and Simulation:

- Structure Preparation: Use

tleapto add solvent and ions for AMBER simulations. - Equilibration: Follow standard protocol with gradual release of restraints.

- Production Run: Execute extended simulation with periodic boundary conditions.

Analysis with MDAnalysis:

- MSD Calculation: Use

MSDclass fromMDAnalysis.analysis.msdmodule. - VACF Calculation: Utilize the

VelocityAutocorrclass from thetransport_analysispackage [21]: - Diffusion Coefficient: Calculate Green-Kubo self-diffusivity using

self_diffusivity_gkmethod [21].

Applied Case Studies in Molecular Transport

Lithium Ion Transport in Battery Materials

In a study of Lithium diffusion in Li~0.4~S cathode materials, researchers employed ReaxFF molecular dynamics to calculate diffusion coefficients at 1600 K [4]. The simulation protocol involved:

- Structure Generation: Creating amorphous structures through simulated annealing (heating to 1600 K followed by rapid cooling).

- Production Simulation: Running 110,000 steps with a 0.25 fs timestep, sampling every 5 steps.

- Analysis: Both MSD and VACF methods were implemented, yielding consistent results:

- MSD method: D = 3.09 × 10^-8^ m²/s

- VACF method: D = 3.02 × 10^-8^ m²/s

The close agreement between methods validated the approach. To extrapolate to lower temperatures, researchers used the Arrhenius equation with data from multiple temperatures (600 K, 800 K, 1200 K, 1600 K) [4]:

[D(T) = D0 \exp{(-Ea / k_{B}T)}]

Water and Ion Transport in Polymer Membranes

MD simulations have revealed crucial insights into transport mechanisms within ion exchange polymers like Nafion, used in fuel cells [23]. Key findings include:

- Morphological Dependence: Diffusion coefficients of water and hydronium ions vary with the number of polymer chains, with errors significantly reduced in 14 and 16-chain models [23].

- Computational Efficiency: A proposed equilibration method demonstrated ~200% greater efficiency than conventional annealing and ~600% improvement over lean methods [23].

- Transport Mechanism: The study highlighted the importance of achieving morphological threshold in models to obtain accurate transport properties independent of system size.

Molecular Transport in Pervaporation Desalination

In PV desalination membranes, MD simulations revealed transformation of water dispersion forms from nano-sized clusters to single molecules as concentration gradient decreases [24]. This fundamental insight explained the deviation from traditional solution-diffusion model assumptions in highly swollen membranes.

Table 2: Diffusion Coefficients from Case Studies in the Literature

| System Studied | Temperature (K) | Method | Diffusion Coefficient (m²/s) | Simulation Details |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lithium in Li~0.4~S [4] | 1600 | MSD | 3.09 × 10^-8^ | ReaxFF; 100000 production steps |

| Lithium in Li~0.4~S [4] | 1600 | VACF | 3.02 × 10^-8^ | ReaxFF; 100000 production steps |

| SPC/E Water Model [21] | 298 | Green-Kubo | 2.47 × 10^-9^ | 20 ps simulation |

| Copper in Liquid Copper [22] | 2000 | MSD | Calculated from (\left\langle X^{2}(t) \right\rangle) | EAM potential; 864 atoms |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Essential Tools for MD Studies of Molecular Transport

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Implementation in MD Packages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Force Fields | ReaxFF [4], EAM [22], AMBER [21] | Defines interatomic potentials for different materials | Parameter sets in LAMMPS, GROMACS, AMBER |

| Thermostats | Berendsen [4], Nosé-Hoover [22] | Controls temperature during simulation | fix nvt in LAMMPS; tcoupl in GROMACS |

| Barostats | Martyna-Tobias-Klein [22], Berendsen [4] | Maintains pressure during NPT simulations | fix npt in LAMMPS; pcoupl in GROMACS |

| Analysis Tools | MDAnalysis [21], VMD, gmx msd [15] |

Trajectory analysis and diffusion calculation | Python packages; Built-in tools |

| Validation Methods | Arrhenius plot [4], Convergence testing [19] | Ensures accuracy and reliability of results | Multi-temperature simulations |

Advanced Analysis and Validation Techniques

Error Analysis and Convergence Testing

Robust diffusion coefficient calculations require careful error analysis. The gmx msd tool in GROMACS provides an error estimate based on the difference between diffusion coefficients obtained from fits over the two halves of the fit interval [15]. In MDAnalysis, the Transport Analysis package implements comprehensive statistical validation for calculated transport properties [21].

For reliable results, the MSD should demonstrate a clear linear regime before fitting. As observed in the liquid copper study, the mean-square displacement may become noisy at time intervals approaching the total simulation length, necessitating careful selection of the fitting range [22]. A common practice is to use the first 10% to 90% of the MSD curve for linear regression unless the linear regime is clearly established in a different range [15].

Extrapolation to Experimental Conditions

Due to computational limitations, MD simulations often operate at higher temperatures than experimental conditions, particularly for solid-state diffusion [4]. The Arrhenius relationship enables extrapolation to lower temperatures:

[\ln{D(T)} = \ln{D0} - \frac{Ea}{k_{B}}\cdot\frac{1}{T}]

This requires simulations at multiple temperatures (typically at least four) to determine the activation energy (E~a~) and pre-exponential factor (D~0~) [4]. This approach provides an upper bound for diffusion coefficients at lower temperatures where direct simulation would require prohibitively long computation times.

Molecular Dynamics simulations provide powerful approaches for investigating molecular transport phenomena across diverse scientific domains. The protocols outlined in this application note for LAMMPS, GROMACS, and AMBER/MDAnalysis platforms enable researchers to implement robust methods for diffusion coefficient calculation using both MSD and VACF approaches. The case studies presented demonstrate the application of these methods to real-world research scenarios, from battery materials to polymer membranes.

Successful implementation requires attention to critical factors including proper system equilibration, sufficient trajectory length for statistical sampling, appropriate fitting ranges for MSD analysis, and validation through error analysis and multi-temperature simulations. As MD simulations continue to evolve with improved force fields, enhanced sampling techniques, and more efficient algorithms, their role in quantifying and understanding molecular transport will undoubtedly expand, providing ever more valuable insights for materials design and drug development.

Practical Implementation in LAMMPS, GROMACS, and AMBER

This application note provides detailed protocols for calculating diffusion coefficients in LAMMPS using Mean-Squared Displacement (MSD) and Velocity Autocorrelation Function (VACF) methods. These methods are essential for understanding molecular transport properties in materials science, drug development, and biological research, enabling cross-validation with other major molecular dynamics packages like GROMACS and AMBER.

Theoretical Background and Key Equations

The diffusion coefficient (D) quantifies the rate of particle movement through a material. In molecular dynamics, D can be derived through two fundamental approaches, both implemented in LAMMPS via specific compute commands.

The Einstein relation connects diffusion to the slope of the mean-squared displacement over time: MSD(t) = ⟨|r(t) - r(0)|²⟩ = 2nDt [5] [25], where n is the dimensionality of the system (2 for 2D, 6 for 3D). This relationship is implemented in LAMMPS via the compute msd command.

The Green-Kubo relation links diffusion to the time integral of the velocity autocorrelation function: D = (1/(2n)) ∫⟨v(t) · v(0)⟩ dt [5] [26], where the integral is taken from zero to infinity. This is calculated in LAMMPS using the compute vacf command.

The table below summarizes the core characteristics of the two primary methods for calculating diffusion coefficients in LAMMPS.

| Feature | MSD Method (compute msd) |

VACF Method (compute vacf) |

|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Relation | Einstein relation [5] [25] | Green-Kubo relation [5] [26] |

| LAMMPS Compute Command | compute ID group-ID msd [keywords] [27] |

compute ID group-ID vacf [5] [26] |

| Primary Output | Global vector of 4 values: ⟨dx²⟩, ⟨dy²⟩, ⟨dz²⟩, ⟨dr²⟩ [27] | Global vector of 4 values [26] |

| Dimensionality Factor (n) | 4 for 2D, 6 for 3D [28] | 2 for 2D, 3 for 3D |

| Key Advantage | Intuitive, direct from particle trajectories | Sensitive to short-time dynamics and vibrational modes |

| Considerations | Requires unwrapped coordinates [27] [29] | Results can be noisy, may require extensive sampling [30] [26] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Diffusion Coefficient from Mean-Squared Displacement (MSD)

This protocol uses the compute msd command to calculate the diffusion coefficient from the slope of the MSD versus time plot [27] [5].

The following workflow outlines the logical sequence of steps in Protocol 1:

Protocol 2: Diffusion Coefficient from Velocity Autocorrelation Function (VACF)

This protocol uses the compute vacf command and integrates the VACF to obtain the diffusion coefficient [5] [26].

The following workflow outlines the logical sequence of steps in Protocol 2:

Critical Implementation Notes

Unwrapped Coordinates for MSD: The

compute msdcommand requires "unwrapped" coordinates to correctly account for atoms crossing periodic boundaries [27]. Using wrapped coordinates will result in grossly inaccurate MSD values, a common pitfall noted when comparing LAMMPS output with other analysis tools [29]. Ensure your dump files contain unwrapped coordinates (xu,yu,zuin LAMMPS dump formats).Center-of-Mass Correction: For molecular systems, use the

com yeskeyword withcompute msdto subtract the center-of-mass drift of the entire group. This provides the self-diffusion coefficient relative to the system's center of mass [27].Thermostat Influence: The choice of thermostat and its application can influence diffusion behavior. For production runs aimed at measuring transport properties, best practice often involves turning off stochastic thermostats like

fix langevinto avoid interfering with the natural dynamics of the system [28].Molecule-Based Calculation: To compute the diffusion coefficient or VACF for the center of mass of molecules, use the

compute msd/chunkcommand [30]. A specializedcompute vacf/chunkis also available for calculating VACF of chunks, such as molecular centers of mass [30].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential LAMMPS Commands

The table below catalogues the key LAMMPS commands and "research reagents" essential for successfully implementing these protocols.

| Command/Solution | Function | Critical Keywords/Usage Notes |

|---|---|---|

compute msd |

Calculates mean-squared displacement [27]. | com yes: Corrects for COM drift. average yes: Uses average position (for solids). |

compute vacf |

Calculates velocity autocorrelation function [5] [26]. | Outputs a vector for integration. |

compute msd/chunk |

Calculates MSD of chunk centers of mass (e.g., molecules) [30]. | Preceded by compute chunk/atom and compute vcm/chunk. |

fix vector |

Stores global vector from a compute over multiple timesteps. | Essential for obtaining the slope (variable slope) or integral (variable trap). |

fix ave/time |

Averages and outputs computes over time. | Used to write MSD or VACF data to file for external analysis. |

variable slope |

Performs linear fit on a vector to find slope. | Used for MSD method: slope(f_vector)/(2*n*dt) [5]. |

variable trap |

Performs trapezoidal numerical integration on a vector. | Used for VACF method: trap(f_vector)/n [5]. |

This application note provides a comprehensive protocol for calculating diffusion coefficients using the gmx msd tool within the GROMACS molecular dynamics package. We detail the theoretical foundation, practical execution, and critical analysis steps required to obtain accurate self-diffusion constants from mean square displacement (MSD) data. The methodology is framed within a broader research context involving comparative molecular dynamics studies across GROMACS, AMBER, and LAMMPS platforms, highlighting considerations for ensuring consistency and reproducibility in diffusion studies. This guide is tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals requiring robust characterization of molecular mobility in complex systems.

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation serves as a computational microscope, enabling the observation of atomic-scale motions and the calculation of fundamental thermodynamic and kinetic properties. Among these, the self-diffusion coefficient is a critical parameter quantifying the rate of random translational motion of molecules within a fluid phase. Accurate calculation of diffusion coefficients is essential in diverse applications, from predicting drug permeability across biological membranes to understanding transport phenomena in materials science.

The gmx msd module within GROMACS implements the Einstein relation for calculating diffusion coefficients from mean square displacement [31]. This tool provides a straightforward method for analyzing molecular mobility, but obtaining accurate results requires careful attention to protocol details, including trajectory preparation, parameter selection, and data fitting procedures. This guide outlines a standardized approach for diffusion analysis, contextualized within the broader framework of cross-platform MD validation studies that have revealed subtle but significant differences between simulation packages including GROMACS, AMBER, and LAMMPS [16] [32].

Theoretical Foundation

The mean square displacement (MSD) represents the average squared distance particles travel over a specific time interval. For three-dimensional Brownian motion, the MSD exhibits a linear relationship with time, with a slope proportional to the diffusion coefficient through the Einstein relation:

\[ \langle | \mathbf{r}(t) - \mathbf{r}(0) |^2 \rangle = 2nDt \ \text{for large } t \]

where \(\mathbf{r}(t)\) is the position at time \(t\), \(n\) is the dimensionality of the diffusion, \(D\) is the self-diffusion coefficient, and the angle brackets denote an ensemble average [31]. The GROMACS gmx msd tool automates the calculation of this relationship by performing linear regression on the MSD(t) curve to extract \(D\).

For anisotropic systems or specific diffusion components, the analysis can be constrained to one or two dimensions using the -type or -lateral options. For example, lateral diffusion in lipid bilayers can be analyzed using the -lateral z flag to compute MSD only in the x-y plane [33].

Computational Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the complete workflow for diffusion coefficient calculation using gmx msd, from trajectory preparation to final validation:

Figure 1: Complete workflow for diffusion coefficient calculation with gmx msd, highlighting critical optimization parameters.

Trajectory Preparation

Before MSD analysis, ensure your trajectory contains continuous, unwrapped molecular coordinates:

The -pbc whole option corrects for molecules that cross periodic boundary conditions, which is essential for accurate displacement calculations. The gmx msd tool performs this operation by default with its -rmpbc option [15], but preprocessing ensures visualization compatibility.

Index Group Selection

Create appropriate index groups containing the atoms or molecules for MSD analysis:

For molecular diffusion calculations, select the entire molecule rather than individual atoms. The -mol flag in gmx msd computes MSD for individual molecular centers of mass and is particularly useful for analyzing solvent or lipid diffusion [15] [33].

Step-by-Step Protocol

Basic MSD Calculation

Execute gmx msd with appropriate parameters for a standard diffusion calculation:

Table 1: Essential gmx msd parameters for diffusion analysis

| Parameter | Default Value | Recommended Value | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

-f |

traj.xtc |

Input trajectory | Input trajectory file (XT, TRR, etc.) |

-s |

topol.tpr |

Input structure | System topology/structure file |

-n |

index.ndx |

Custom index file | Atoms/molecules for MSD analysis |

-o |

msdout.xvg |

Output file | MSD versus time data |

-tu |

ps |

ns |

Time unit for output (fs, ps, ns) |

-trestart |

10 ps | 50-100 ps | Time between reference points |

-beginfit |

-1 (10%) | Specific time value | Start time for linear fitting |

-endfit |

-1 (90%) | Specific time value | End time for linear fitting |

-mol |

Not set | Use for molecules | Calculate per-molecule diffusion |

-type |

unused |

x, y, z, or unused |

Dimensionality of diffusion |

Specialized Diffusion Analysis

Lateral Diffusion in Membranes

For lateral diffusion of lipids in bilayers, select a reference atom (e.g., phosphorus for phospholipids) and use the -lateral option:

This approach confines the MSD calculation to the membrane plane, providing the lateral diffusion coefficient essential for membrane biophysics studies [33].

Anisotropic Diffusion

For systems with anisotropic diffusion (e.g., channel proteins, liquid crystals), calculate directional diffusion coefficients:

Data Analysis and Interpretation

Identifying the Linear MSD Region

The most critical step in diffusion analysis is identifying the appropriate time range for linear fitting. The MSD curve typically exhibits three regions: (1) a ballistic regime at short times with steep slope, (2) a linear regime where diffusion follows Brownian motion, and (3) a noisy plateau at long times due to insufficient sampling [14].

The following diagram illustrates the proper selection of the linear fitting region:

Figure 2: Identification of appropriate linear fitting region in MSD analysis, showing the ballistic, linear, and noisy plateau regimes.

Table 2: Troubleshooting MSD Analysis

| Issue | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Non-linear MSD at all times | Insufficient simulation length | Extend simulation time |

| MSD curve appears "wobbly" after initial linear region | Insufficient sampling at long time deltas | Use -maxtau to limit maximum delta or increase -trestart |

| Abrupt changes in MSD slope | System phase changes or artifacts | Verify system stability and equilibration |

| Different D values between GROMACS/AMBER/LAMMPS | Different cutoff parameters or Coulomb constants | Standardize nonbonded parameters across platforms [16] |

Calculating the Diffusion Coefficient

The diffusion coefficient is calculated from the slope of the MSD curve:

\[ D = \frac{\text{slope}}{2n} \]

where \(n\) is the dimensionality of the diffusion (1 for -type z, 2 for -lateral, 3 for 3D diffusion). GROMACS automatically performs this calculation and reports both the diffusion coefficient and an error estimate based on the difference between fits over the first and second halves of the fitting interval [15].

For the example MSD plot shown in the search results [14], the linear region between approximately 1-5 ns should be used for fitting, avoiding both the ballistic regime (<1 ns) and the noisy region (>5 ns) where statistical sampling becomes poor.

Cross-Platform Considerations

Comparative studies between MD packages have revealed that consistent force field implementation is essential for reproducible diffusion coefficients. Key factors causing discrepancies between GROMACS, AMBER, and LAMMPS include:

- Different Coulomb constants between programs represent one of the largest sources of energy discrepancies [16]

- Varying default cutoff parameters for nonbonded interactions

- Different thermostat and barostat implementations affecting ensemble generation

- Divergent 1-2, 1-3, and 1-4 neighbor exclusion settings (e.g.,

special_bondsin LAMMPS vs.fudgeLJin GROMACS) [32]

To ensure consistent results across platforms:

- Use conversion tools like ParmEd and InterMol for faithful parameter translation [16]

- Explicitly set nonbonded cutoffs and long-range electrostatics methods rather than relying on defaults

- Compare forces from a single configuration between platforms as a validation step [32]

Table 3: MD Software Comparison for Diffusion Studies

| Feature | GROMACS | AMBER | LAMMPS |

|---|---|---|---|

| MSD Tool | gmx msd with comprehensive options |

cpptraj diffusion analysis |

compute msd command |

| Performance | Highly optimized for CPU/GPU [34] | Good GPU acceleration [35] | Excellent scalability |

| Force Field Support | AMBER, CHARMM, OPLS [34] | Native AMBER force fields | Extensive force field library |

| Strengths for Diffusion | Lateral diffusion options, per-molecule analysis [33] | Biomolecular specialization | Customizable analysis options |

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Diffusion Studies

| Reagent/Software | Function/Role | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| GROMACS Suite | MD simulation and analysis | Primary environment for gmx msd execution |

| AMBER Tools | Force field parameterization | Alternative platform for comparative studies |

| ParmEd | Parameter/file conversion | Ensures consistency between MD packages [16] |

| VMD | Trajectory visualization | Verification of system stability and diffusion behavior |

| Grace/Xmgrace | Data plotting | MSD curve visualization and manual fitting |

| Index Groups | Selection of atoms/molecules | Defines the diffusing species for analysis |

| Stable Membrane Systems | Model membrane environment | Essential for lateral diffusion studies |

Advanced Applications

Umbrella Sampling and Diffusion

In enhanced sampling methods like umbrella sampling, tight harmonic restraints typically destroy kinetic information needed for diffusion calculations [36]. Instead, the AWH (Adaptive Weighting Method) approach can simultaneously determine both the potential of mean force and position-dependent diffusion coefficients [36]. This is particularly valuable for calculating permeability coefficients in membrane systems.

Error Analysis and Validation

The statistical uncertainty in diffusion coefficients arises from both finite sampling and the choice of fitting region. For more robust error estimation:

- Calculate diffusion coefficients for independent trajectory segments

- Use generalized least-squares approaches that account for correlation between MSD values [14]

- Compare results using different

-beginfitand-endfitvalues to assess sensitivity

The gmx msd tool provides a robust method for calculating diffusion coefficients from molecular dynamics trajectories when used with careful attention to protocol details. Proper identification of the linear MSD region, appropriate parameter selection, and awareness of cross-platform implementation differences are essential for obtaining accurate, reproducible results. As molecular dynamics continues to advance toward increasingly predictive simulation, standardized protocols for calculating fundamental transport properties like diffusion coefficients will play a crucial role in validating force fields and simulation methodologies across diverse research applications.

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations employing the AMBER simulation package and the General AMBER Force Field (GAFF) provide powerful tools for investigating the translational diffusion of solutes and proteins, a fundamental property governing biological processes from cellular signaling to drug action [37]. Accurate calculation of diffusion coefficients (D₀) in infinitely dilute solutions establishes the upper limit for molecular transport kinetics in physiological environments [37]. However, obtaining reliable diffusion data from simulations requires careful consideration of multiple factors, including force field selection, finite-size effects, and sufficient sampling [38] [37]. This application note outlines integrated strategies combining theoretical frameworks, practical protocols, and validation techniques for precise diffusion coefficient calculations using AMBER and GAFF, contextualized within broader molecular dynamics research employing tools like LAMMPS and GROMACS.

Theoretical Foundations of Diffusion in MD Simulations

The Einstein Relation and Mean Squared Displacement

In molecular dynamics simulations, the translational diffusion coefficient is primarily calculated using the Einstein relation, which connects macroscopic diffusion with atomic-scale displacements through the mean squared displacement (MSD) [38]. The fundamental equation is:

2 × N × D = lim{t→∞} (⟨MSD⟩ / t) [38]

Where N represents the dimensionality (typically 1, 2, or 3 for 1D, 2D, or 3D diffusion), D is the diffusion coefficient, t is time, and ⟨MSD⟩ denotes the ensemble-averaged mean squared displacement. The MSD is calculated as ⟨|r(t) - r(0)|²⟩, where r(t) is the position at time t and r(0) is the initial position [38]. For accurate results, the MSD must be calculated in the diffusive regime where it increases linearly with time, requiring sufficient simulation length to achieve this limiting behavior [38].

Finite-Size Effects and Corrections

A critical consideration in MD simulations of diffusion is the finite-size effect, where the apparent diffusion coefficient (Dapp) measured in periodic boundary condition simulations differs from the true infinite-system value (D₀) [37]. The functional relationship for cubic simulation cells is:

Dapp = D₀ - (kBTξEW)/(6πηL) [37]

Where kB is Boltzmann's constant, T is temperature, η is solvent viscosity, L is simulation box edge length, and ξEW ≈ 2.837298 is a unitless cubic lattice self term [37]. This systematic finite-size effect necessitates either extrapolation to infinite system size through multiple simulations with varying box dimensions or application of single-simulation corrections such as the Yeh-Hummer method [37].

Table 1: Key Parameters in Diffusion Coefficient Calculations

| Parameter | Symbol | Description | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Apparent Diffusion Coefficient | Dapp | Diffusion coefficient measured directly from simulation with periodic boundary conditions | Depends on system size L [37] |

| Infinite Dilution Diffusion Coefficient | D₀ | True diffusion coefficient extrapolated to infinite system size | Can be compared with experimental values [37] |

| Mean Squared Displacement | MSD | ⟨|r(t) - r(0)|²⟩ | Must show linear regime with time for valid calculation [38] |

| Hydrodynamic Radius | RH | Effective radius for Stokes-Einstein relationship | Affected by solvation and molecular shape [37] |

| System Size Parameter | L | Simulation box edge length | Larger L reduces finite-size effects [37] |

AMBER-Specific Implementation Protocols

System Preparation and Force Field Selection

Proper system preparation is foundational for accurate diffusion calculations. For AMBER simulations, this process begins with structure generation and force field parameterization:

Topology and Coordinate File Generation: Create initial structures using tools like Discovery Studio Visualizer or xleap, then generate AMBER topology (.prmtop) and coordinate (.inpcrd) files using tleap [39]. For non-standard molecules, the antechamber tool with AM1-BCC charge calculation provides GAFF parameters [40] [39].

Force Field Considerations: GAFF has undergone iterations with improvements in bonded and nonbonded parameters [40]. Select appropriate versions (GAFF1, GAFF2, or optimized variants) based on the specific molecule. For urea, for instance, charge-optimized GAFF versions (GAFF-D1, GAFF-D3) show improved performance for both solution and crystal properties [40]. For proteins, Amber ff19SB coupled with the OPC water model performs well for both folded and disordered systems [41].

Solvation and Neutralization: Solvate systems using explicit water models (TIP3P, OPC) in cubic boxes with sufficient padding (typically 1.0-1.5 nm beyond the solute) [37] [41]. Add counterions to neutralize system charge using the tleap module [39].

Production MD and MSD Calculation Protocol

Simulation Parameters: After energy minimization and equilibration, run production simulations with parameters optimized for diffusion calculations. Use a time step of 2-3 fs with LINCS constraints for hydrogen bonds [37]. Employ the Langevin dynamics thermostat (ntt=3 in AMBER) with a collision frequency of 1.0 ps⁻¹ or the Nosé-Hoover thermostat for constant temperature control [41]. For pressure control, the Parrinello-Rahman barostat with a time constant of 10 ps maintains constant pressure [37].

Trajectory Processing: Process trajectories using cpptraj with the 'unwrap' command to remove periodic boundary effects before MSD calculation [38]. The 'diffusion' command in cpptraj calculates MSD and fits diffusion coefficients using the Einstein relation. For membrane systems or other anisotropic environments, use the 'xydiffusion' option to calculate direction-dependent diffusion [38].

Sampling Considerations: Ensure sufficient sampling by running multiple independent trajectories (10+ replicas recommended) [37]. For solutes with limited mobility (e.g., proteins), longer simulation times are essential—lipids or solutes with fewer molecules require significantly longer sampling than water molecules to achieve linear MSD behavior [38].

Table 2: AMBER MD Parameters for Diffusion Studies

| Parameter Category | Specific Settings | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Integration | dt = 0.002 ps (2 fs), nstlim = 5,000,000+ | Balance between numerical stability and computational efficiency [38] |

| Temperature Control | ntt=3, gamma_ln=1.0, temp0=310.0 | Langevin dynamics provides efficient thermostatting [38] [41] |

| Pressure Control | ntp=1, pres0=1.0, taup=10.0 | Isotropic pressure scaling maintains system density [38] |

| Nonbonded Interactions | cut=8.0, ntb=2, ig=-1 | Particle Mesh Ewald for long-range electrostatics [37] |

| Trajectory Output | ntwx=5000, ntpr=5000, ntwr=50000 | Sufficient frequency for MSD analysis while managing storage [38] |

Validation and Troubleshooting

Finite-Size Effect Correction Protocol

To address finite-size artifacts in diffusion calculations, implement the following protocol:

Multi-Size Simulation Approach: Run simulations with at least 5 different box sizes (e.g., L = 3.0, 3.5, 4.0, 4.5, 5.0 nm for small solutes; 5.0-8.0 nm for proteins) [37]. For each size, run multiple independent replicas (10 recommended) to improve statistics [37].

Extrapolation to Infinite System Size: Plot Dapp versus 1/L and perform linear regression. The y-intercept (1/L → 0) provides D₀ [37]. For cubic simulation cells, the relationship is linear, enabling straightforward extrapolation.

Single-Simulation Correction: When multi-size simulations are computationally prohibitive, apply the Yeh-Hummer correction: D₀ = Dapp + (kBTξEW)/(6πηL), where η is the shear viscosity of the water model at the simulation temperature [37].

Solvent Viscosity Adjustment: Account for differences between simulated and experimental water viscosity using: D₀,expt = D₀,sim × (ηsim/ηexpt) [37]. For example, TIP3P water has significantly lower viscosity than real water, necessitating this correction for experimental comparison.

Common Issues and Solutions

Non-Linear MSD Profiles: If MSD versus time plots show curvature or plateaus at longer times, this indicates insufficient sampling [38]. Solution: Extend simulation time significantly, particularly for larger, slower-moving solutes. For proteins or lipids with 300+ atoms, simulations may need to exceed hundreds of nanoseconds to achieve proper diffusive behavior [38].

Erratic MSD Fluctuations: Downward spikes or non-monotonic MSD behavior, particularly around 50+ ns, often result from trajectory processing errors or insufficient sampling [38]. Verify proper unwrapping of coordinates in cpptraj using the 'unwrap' command before MSD calculation [38].

Force Field Dependencies: Different GAFF versions yield varying diffusion properties [40]. Validate against known experimental values for similar compounds. For specialized systems like bacterial membranes, consider specialized force fields (e.g., BLipidFF) which may better capture diffusion characteristics than general force fields [42].

Case Study: Urea Diffusion with GAFF

Protocol Implementation and Results

The diffusion behavior of urea in aqueous solution provides an instructive case study for GAFF validation. Recent assessments of GAFF and OPLS force fields for urea enable direct comparison of simulation protocols with experimental data [40].

System Setup: A single urea molecule was solvated in TIP3P water using tleap with a cubic box of 3.0 nm edge length. After energy minimization (1000 steps steepest descent), the system was equilibrated for 150 ps in NPT ensemble at 310.15 K and 1 atm using the Parrinello-Rahman barostat and v-rescale thermostat [37].

Production Simulation: Following equilibration, 100 ns production MD was performed with a 3 fs time step, employing LINCS constraints and Particle Mesh Ewald electrostatics with 1.0 nm cutoff [37]. Multiple independent trajectories (10 replicas) were run for statistical reliability.

Finite-Size Correction: Apparent diffusion coefficients were calculated from MSD analysis between 20-80 ns where linear behavior was confirmed. The Yeh-Hummer correction was applied using the computed viscosity of TIP3P water at 310.15 K [37].

Results: The charge-optimized GAFF force field (RESP-D3 charges) demonstrated improved agreement with experimental urea diffusion coefficients compared to standard GAFF2 with AM1-BCC charges, highlighting the importance of charge parametrization for accurate diffusion properties [40].

Cross-Software Comparison and Integration

AMBER, GROMACS, and LAMMPS Interoperability

While this protocol focuses on AMBER/GAFF implementation, understanding cross-software compatibility is essential for methodological integration:

Parameter Transfer: GAFF parameters generated via antechamber can be converted to GROMACS format using tools like ACPYPE, enabling consistent force field application across simulation platforms [37]. This facilitates validation of diffusion coefficients across different MD engines.

Consistency Checks: When comparing AMBER and GROMACS results for identical systems, verify force calculations in NVE ensembles to ensure consistent interaction potentials [32]. Differences in 1-2, 1-3, and 1-4 neighbor exclusion settings ('special_bonds' in LAMMPS, 'fudgeLJ' in GROMACS) can cause divergent dynamics despite identical force field parameters [32].

Performance Considerations: LAMMPS typically offers computational advantages for large-scale parallel simulations, while AMBER provides specialized biomolecular integrators [20]. GROMACS balances performance with biophysical accuracy. For diffusion studies requiring extensive sampling, consider hybrid approaches using multiple packages for validation.

Table 3: Key Computational Tools for Diffusion Studies

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| AMBER Molecular Dynamics Package | MD simulation engine with specialized biomolecular force fields | Primary simulation platform for solute and protein diffusion studies [39] |

| General AMBER Force Field (GAFF) | Force field for small organic molecules | Parameterization of drug-like molecules and solutes [40] |

| Antechamber | Automated parameterization tool for GAFF | Generation of force field parameters for non-standard molecules [40] [39] |

| CPPTRAJ | Trajectory analysis tool | MSD calculation and diffusion coefficient fitting [38] |

| Packmol | Initial configuration builder | Packing of molecules in simulation boxes with defined density [43] |

| VMD | Molecular visualization and analysis | Trajectory visualization and geometric analysis [39] |

| Gaussian | Electronic structure package | RESP charge calculations for force field parametrization [42] [39] |

| ACPYPE | Python interface for Antechamber | Conversion of AMBER topologies to GROMACS format [37] |