A Practical Guide to Stress-Strain Analysis Using Molecular Dynamics: From Fundamentals to Biomedical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and scientists on performing stress-strain analysis using Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations.

A Practical Guide to Stress-Strain Analysis Using Molecular Dynamics: From Fundamentals to Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and scientists on performing stress-strain analysis using Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations. It covers foundational principles of MD and its application in studying material deformation at the atomic scale, detailed methodological workflows for setting up and running deformation simulations using popular packages like AMS, LAMMPS, and GROMACS, strategies for troubleshooting common issues and optimizing simulation parameters, and rigorous approaches for validating results against experimental data. Special emphasis is placed on techniques relevant to biomedical and drug development research, including the analysis of proteins, polymers, and biomaterials, providing a complete framework for implementing reliable MD-based mechanical characterization.

Understanding the Fundamentals: Why MD for Stress-Strain Analysis?

The Virtual Molecular Microscope: Conceptual Foundation

Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulation serves as a virtual molecular microscope, allowing researchers to observe and quantify molecular processes that are inaccessible to experimental techniques. By numerically solving Newton's equations of motion for all atoms in a system, MD provides atomic-resolution trajectories that reveal the dynamic behavior of biomolecules, materials, and complex systems over time. This computational approach effectively bridges the gap between static structural information and dynamic functional behavior, creating a powerful platform for predicting material properties and molecular interactions [1].

The "microscope" analogy is particularly apt because MD enables the visualization of phenomena across multiple spatial and temporal scales. From the local vibrations of individual bonds to large-scale conformational changes in proteins and polymers, MD simulations provide a dynamic window into molecular world. This capability is especially valuable for stress-strain analysis, where MD can directly simulate the response of molecular systems to mechanical deformation and calculate emergent mechanical properties from first principles [2] [3].

MD for Stress-Strain Analysis: Core Principles and Methodologies

Stress-strain analysis using MD simulations involves applying controlled deformation to a molecular system and calculating the resulting stress tensor components. This approach allows researchers to derive key mechanical properties such as Young's modulus, Poisson's ratio, and yield strength directly from molecular-level interactions [2] [4].

The fundamental principle involves simulating a tensile test at the molecular scale. As the simulation box is deformed along specific directions, the stress response is calculated based on interatomic forces. The OPLS-AA force field has demonstrated particular effectiveness for predicting mechanical properties of polymers, showing excellent agreement with experimental data for materials like Kapton [2]. Two primary methodologies exist for extracting mechanical properties: continuous deformation mode simulations and the novel Regression Fringe Response method, which automates the interpretation of stress-strain curves to remove subjective human interpretation [2] [3].

Quantitative Mechanical Properties from MD Simulations

Table 1: Mechanical Properties of Polyimides Derived from MD Simulations [2]

| Polymer System | Simulation Method | Young's Modulus (GPa) | Poisson's Ratio | Force Field |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kapton (PMDA-ODA) | Continuous deformation | ~2.7-3.2 (aligned with experimental data) | ~0.34-0.38 | OPLS-AA |

| Kapton (PMDA-ODA) | Tensile test scripting | Similar to continuous deformation | Similar to continuous deformation | COMPASS |

| PMDA-BIA | Continuous deformation | Literature data sparse | Literature data sparse | OPLS-AA |

| BPDA-APB | Not specified | Accurate prediction vs. experimental | Not specified | OPLS-AA |

Table 2: Coarse-Grained MD Analysis of Polymer Network Elasticity [5]

| Network Type | Functionality | Shear Modulus (G) Relation | Key Structural Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Star Polymer Networks (SPNs) | 3- and 4-armed | G ≈ 2G_ph | Higher density of effective junctions, suppressed loop formation |

| Telechelic Polymer Networks (TPNs) | 3- and 4-armed | G ≈ 2G_ph | Tendency to trap loops, lower effective strand density |

| Classical Affine Model | N/A | Gaf = νkBT | Assumes all strands deform uniformly with macroscopic strain |

| Phantom Network Model | N/A | Gph = (ν-μ)kBT | Accounts for junction fluctuations |

Experimental Protocols for Stress-Strain Analysis via MD

Protocol 1: All-Atom Stress-Strain Simulation of Polymers

This protocol outlines the procedure for determining Young's modulus and Poisson's ratio of amorphous polymers using all-atom MD simulations, based on methodologies successfully applied to polyimides [2].

System Preparation:

- Step 1: Monomer Construction: Build initial monomer coordinates using bond lengths and angles from experimental or theoretical references. Export coordinates to xyz-file format.

- Step 2: Polymer Assembly: Use polymer construction tools like Moltemplate to create simulation boxes with specified chain lengths and number of chains. A chain length of 20 monomers often represents a practical compromise between computational cost and accuracy.

- Step 3: Force Field Selection: Employ the OPLS-AA force field for organic polymers, which has demonstrated accurate prediction of mechanical properties. Use harmonic potentials for bonds and angles, OPLS style for dihedrals, and Lennard-Jones potentials with Coulombic interactions for non-bonded interactions.

Equilibration Procedure:

- Step 4: Multi-step Equilibration: Implement a 21-step equilibration procedure alternating between NVT (constant temperature and volume) and NPT (constant temperature and pressure) ensembles. This removes structural artifacts from initial configuration and ensures proper system relaxation.

- Step 5: Ambient Conditions: Set final pressure to 1 atm and temperature to 300 K to represent standard conditions. Use a maximum pressure of 50,000 atm during equilibration to achieve proper density.

Mechanical Deformation:

- Step 6: Deformation Application: Apply controlled strain using a StrainConfigurationHook with defined strain direction (e.g., 'x'), strain rate (e.g., 0.005/ps), and strain interval.

- Step 7: Stress Measurement: Use MDMeasurement hook to record stress and strain tensors at specified intervals (e.g., every MD step). For isotropic materials, the diagonal components (xx, yy, zz) are typically most relevant.

Analysis:

- Step 8: Young's Modulus Calculation: Perform linear regression on the linear portion of the stress-strain curve. The slope provides Young's modulus. For polyimides, this approach has shown excellent agreement with experimental data.

- Step 9: Poisson's Ratio Determination: Calculate from the ratio of transverse to axial strain during uniaxial deformation.

Protocol 2: Automated Stress-Strain Curve Analysis Using RFR Method

This protocol describes the Regression Fringe Response method for automated interpretation of stress-strain curves from MD simulations [3].

Implementation:

- Step 1: Data Collection: Extract stress-strain data from MD trajectories, ensuring sufficient sampling in the elastic deformation regime.

- Step 2: RFR-Method Application: Apply the Regression Fringe Response algorithm to automatically identify the linear region and calculate mechanical properties without subjective human interpretation.

- Step 3: Validation: Compare results with experimental values to validate the methodology for the specific material class.

Software Requirements:

- The RFR method is implemented in Python and available through the "log_analysis" GUI for stress-strain curve analysis.

Visualization and Workflows

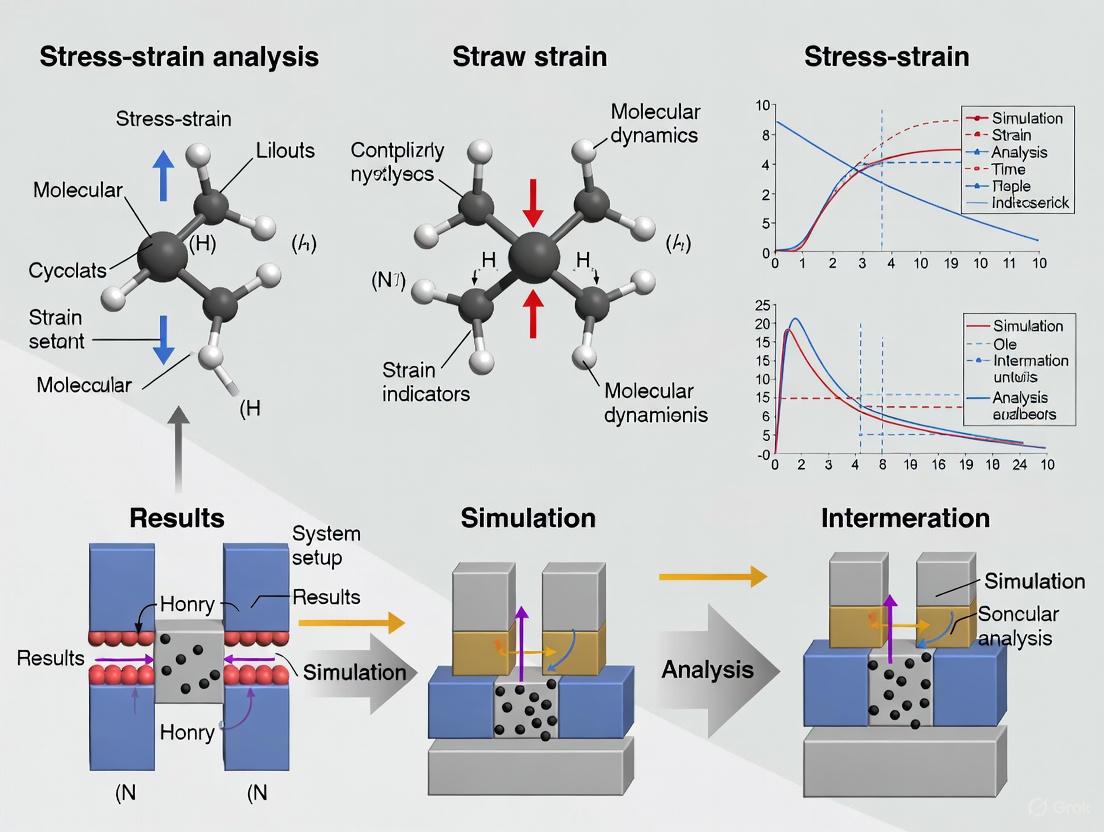

Diagram 1: MD Stress-Strain Analysis Workflow. This workflow outlines the key phases in molecular dynamics simulation for mechanical property determination, from system preparation through to final analysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for MD Stress-Strain Analysis

| Tool Category | Specific Tools/Software | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| MD Simulation Engines | LAMMPS [2], QuantumATK [4] | Core simulation execution | LAMMPS provides flexibility for polymer systems; QuantumATK offers built-in measurement hooks |

| Force Fields | OPLS-AA [2], AMBER, COMPASS | Defines interatomic potentials | OPLS-AA shows excellent accuracy for polymer mechanical properties |

| System Builders | Moltemplate [2] | Polymer system construction | Creates LAMMPS input files from monomer coordinates |

| Analysis Methods | RFR Method [3], Continuous Deformation [2] | Stress-strain curve interpretation | RFR method automates property extraction; Continuous deformation matches experimental data |

| Libraries | ZINC20 [6], REAL Database [1] | Compound libraries for drug discovery | Ultra-large libraries (billions of compounds) enable comprehensive virtual screening |

Advanced Applications and Future Directions

The integration of MD simulations with emerging computational approaches is creating powerful new paradigms for materials science and drug discovery. Machine learning methods are now being combined with MD to dramatically reduce computational costs while maintaining accuracy [6]. Similarly, coarse-grained models enable the simulation of larger systems and longer timescales, particularly valuable for studying complex polymer networks and their mechanical behavior [5].

The Relaxed Complex Method represents another significant advancement, where MD simulations capture target molecule flexibility and reveal cryptic binding pockets for drug discovery [1]. This approach addresses a fundamental limitation of traditional docking methods by incorporating protein dynamics, potentially identifying novel binding sites that emerge during simulation trajectories.

As computing resources continue to expand and algorithms become more sophisticated, MD's role as a virtual molecular microscope will only grow more indispensable. The ability to directly link molecular structure and dynamics with macroscopic mechanical properties provides researchers with an unparalleled tool for rational materials design and drug development.

Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations predict how every atom in a protein or other molecular system will move over time based on a general model of the physics governing interatomic interactions [7]. These simulations capture protein behavior in full atomic detail and at fine temporal resolution, making them invaluable for studying conformational change, ligand binding, and protein folding [7]. Fundamental to MD simulations is the force field (FF), which comprises the set of potential energy functions from which interatomic forces are derived [8]. After decades of careful refinement, current additive protein energy functions have reached sufficient quality for predictive studies of protein dynamics, protein-protein interactions, and pharmacological applications [8].

Theoretical Foundation: Components of a Force Field

A typical molecular mechanics force field incorporates terms that capture electrostatic (Coulombic) interactions between atoms, spring-like terms that model the preferred length of each covalent bond, and terms capturing several other types of interatomic interactions [7]. The energy surface described by the force field must be accurate since lower energy states are expected to be more populated in simulations [8]. The general functional form includes:

- Bonded interactions: Terms for bond stretching, angle bending, and proper and improper dihedral torsions

- Non-bonded interactions: van der Waals forces (typically described by Lennard-Jones potentials) and electrostatic interactions (described by Coulomb's law)

The next major advancement in force field accuracy requires inclusion of electronic polarization effects, as fields induced by ions, solvent, other macromolecules, and the protein itself significantly affect electrostatic interactions [8].

Major Force Fields for Biomolecular Simulation

Additive Force Fields

CHARMM Force Field: The CHARMM additive all-atom force field has been developed since the early 1980s and now covers proteins, nucleic acids, lipids, and carbohydrates [8]. The C36 version introduced significant improvements including a new backbone CMAP potential optimized against experimental data on small peptides and folded proteins, new side-chain dihedral parameters, and improved Lennard-Jones parameters for aliphatic hydrogens [8].

AMBER Force Field: Amber force fields have undergone continuous improvement, with notable revisions focusing on key dihedral angles [8]. The ff99SB update introduced changes to the backbone potential by fitting to additional quantum-level data, while subsequent modifications (ff99SB-ILDN, ff99SB-ILDN-NMR, ff99SB-ILDN-Phi) further refined side-chain torsions and backbone dihedral potentials to better balance secondary structure sampling [8].

Polarizable Force Fields

Drude Polarizable Force Field: Development of the Drude polarizable force field in CHARMM incorporates electronic polarization by attaching charged "Drude particles" to atoms [8]. These particles represent electronic degrees of freedom and respond to the local electrostatic environment. The standard polarizable water model (SWM4-NDP) reproduces important properties of neat liquid water including enthalpy of vaporization, density, static dielectric constant, and self-diffusion constant [8].

AMOEBA Polarizable Force Field: The AMOEBA force field incorporates polarization through an inductive dipole approach where molecular polarizability is represented through atomic point dipoles that respond to the instantaneous electric field [8].

Table 1: Comparison of Major Biomolecular Force Fields

| Force Field | Type | Key Features | Coverage |

|---|---|---|---|

| CHARMM [8] | Additive | Balanced parameters for proteins, lipids, nucleic acids, carbohydrates; C36 version with improved backbone CMAP | Comprehensive biological systems |

| AMBER [8] | Additive | ff99SB family with improved backbone and side-chain dihedrals; part of ff10 collection | Proteins, DNA, RNA, carbohydrates (Glycam) |

| CHARMM Drude [8] | Polarizable | Drude oscillator model; includes electronic polarization; accurate dielectric properties | Small molecules, proteins, nucleic acids, lipids |

| AMOEBA [8] | Polarizable | Inductive point dipole polarization; many-body effects | Proteins, small molecules |

Application to Stress-Strain Analysis in MD Research

Fundamentals of Mechanical Properties Simulation

MD simulations can probe mechanical properties by applying deformation to molecular systems and monitoring the stress response. During such simulations, strain is increased gradually until material failure occurs, as demonstrated in studies of polyacetylene chains where cis-trans bond conversion and eventual chain snapping were observed [9]. The stress tensor components computed during MD simulations provide quantitative data for constructing stress-strain curves that reveal different mechanical regimes and failure points [9].

Protocol for Stress-Strain Analysis of a Polymer Chain

The following methodology outlines the procedure for simulating stress-strain behavior, adapted from a polyacetylene case study [9]:

Step 1: System Setup

- Import molecular structure into MD simulation software

- Select appropriate force field (e.g., CHO.ff for hydrocarbon systems)

- Set up periodic boundary conditions appropriate for the system dimensionality

Step 2: Molecular Dynamics Parameters

- Set simulation length to 850,000 steps for adequate sampling

- Configure sampling frequency at 1,000 steps and checkpoint frequency at 50,000 steps

- Apply thermostat (Nose-Hoover Chain thermostat recommended) with temperature set to 300.15 K and damping constant of 100.0 fs

Step 3: Deformation Configuration

- Apply deformation along desired axis with length velocity of 0.00002 Å/fs

- Ensure proper alignment of deformation tensor with simulation box vectors

- For 1D periodic systems, rotate the polymer chain accordingly

Step 4: Stress Tensor Calculation

- Enable stress tensor computation in the properties settings

- Monitor all six components of the stress tensor during deformation

Step 5: Simulation Execution

- Run the molecular dynamics simulation with deformation

- Monitor simulation progress and check for stability

Step 6: Trajectory Analysis

- Visualize structural changes using molecular visualization tools

- Plot stress-strain curves from the simulation data

- Identify key transitions in the stress-strain relationship

Step 7: Data Processing

- Extract strain and stress tensor components from results

- For the example polyacetylene system, plot stressyy against strainy

- Perform linear regression on initial linear segments to determine elastic modulus

Table 2: Key Parameters for Stress-Strain MD Simulation

| Parameter | Setting | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Force Field | CHO.ff | Describes interatomic interactions for hydrocarbon system |

| Temperature | 300.15 K | Maintain physiological or standard conditions |

| Thermostat | NHC | Regulates temperature with minimal interference |

| Deformation Rate | 0.00002 Å/fs | Applies gradual strain to observe mechanical response |

| Simulation Steps | 850,000 | Ensures adequate sampling of deformation process |

| Stress Tensor | Enabled | Calculates mechanical stress during deformation |

Workflow Visualization

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Stress-Strain MD Simulations

| Tool/Component | Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| CHARMM36 Force Field [8] | Describes energy surface for proteins | Accurate modeling of protein mechanical properties |

| Drude Polarizable FF [8] | Includes electronic polarization effects | Simulations where dielectric response is critical |

| AMOEBA Polarizable FF [8] | Incorporates many-body polarization | Systems with significant electronic response to deformation |

| Nose-Hoover Thermostat [9] | Maintains constant temperature during deformation | Prevents artifactual heating during strain application |

| Stress Tensor Calculator [9] | Computes internal stresses during deformation | Quantitative stress-strain analysis |

| Deformation Algorithm [10] | Applies controlled strain to simulation cell | Mechanical testing of molecular systems |

| AMS MD Software [9] | Performs molecular dynamics with deformation | Complete workflow for stress-strain analysis |

| LAMMPS [10] | MD package supporting complex deformations | Mechanical testing of diverse materials |

Advanced Considerations for Accurate Simulations

Polarizable Force Fields for Mechanical Properties

Incorporating polarizable force fields like Drude or AMOEBA can improve accuracy in stress-strain simulations, particularly for systems where electronic polarization significantly affects mechanical response [8]. The Drude force field properly treats dielectric constants, which is essential for accurate modeling of hydrophobic solvation in biomolecules under mechanical strain [8].

Validation of Mechanical Properties

Simulation results should be validated against experimental data where available. For example, in polyacetylene chain simulations, the stress-strain curve shows distinct segments corresponding to configurational changes (cis-trans conversion) that can be correlated with structural observations [9]. Linear regression analysis of the initial linear portion of the stress-strain curve provides the elastic modulus, which should be compared with experimental measurements when possible.

The Physics Behind Stress-Strain Relationships at the Atomic Scale

The investigation of stress-strain relationships at the atomic scale represents a fundamental shift from continuum mechanics to discrete atomistic interactions. At the nanoscale, mechanical behavior deviates significantly from macroscopic observations due to heightened surface effects, quantum phenomena, and the discrete nature of atomic forces [11]. Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulation has emerged as the predominant tool for probing these relationships by numerically solving equations of motion for each atom in a material, allowing researchers to precisely track atomic response to applied loads [11]. The concept of mechanical stress, while fundamental in macroscopic mechanics, has only more recently been applied systematically in biomolecular and nanomaterial contexts [12]. This application note establishes frameworks for performing rigorous stress-strain analysis within MD research, providing detailed protocols for extracting critical mechanical properties from atomistic simulations.

The mechanical response of nanomaterials is governed by complex factors including size-dependent effects, temperature influences, and varied loading conditions [11]. As materials shrink to the nanoscale, the relative importance of surface atoms escalates due to amplified surface-to-volume ratios, leading to enhanced surface energy effects, surface stress, and surface relaxation that substantially shape resulting stress-strain curves [11]. Additionally, quantum confinement of electrons within nanomaterials induces size-dependent variations in bandgap that profoundly impact mechanical response [11]. Understanding these phenomena requires specialized computational approaches that bridge atomic interactions with emergent mechanical properties.

Theoretical Foundations of Atomistic Stress

Fundamental Principles

In molecular dynamics simulations, mechanical stress is properly a macroscopic quantity that can be computed in terms of atomistic forces and configurations [12]. The virial stress theorem provides the fundamental linkage between discrete atomic interactions and continuum mechanical concepts. For a given atom i in a molecular configuration, the stress tensor is expressed as:

[Formula] σi = (1/Vi) × [ -mivi⊗vi + (1/2) × Σj≠irij⊗fij ] [Formula Description] Where Vi is the characteristic volume of atom i, mi is its mass, vi is its velocity vector, rij is the distance vector between atoms i and j, and fij is the force acting on atom i due to atom j [12].

The characteristic volume (Vi) represents the volume over which local stress is averaged and is not unambiguously specified by theory. A common approach sets characteristic volume equal per atom (Vi = Vtotal/Natoms), where Vtotal is the total simulation box volume and Natoms is the number of atoms [12]. For systems without defined box volume (e.g., implicit solvent trajectories), each atom may be assigned a reference volume such as that of a carbon atom. The time average of the sum of atomic virial stress over all atoms relates directly to the pressure of the simulation system.

Stress Tensor Computation and Decomposition

The full stress tensor (a 3×3 matrix) presents visualization and analysis challenges as components vary with orientation. To simplify representation, the average principal stress at each atom can be computed with a sign change to yield local hydrostatic pressure [12]. This quantity is simply one-third of the trace of the stress tensor, eliminating the need to compute off-diagonal stress tensor components while preserving the ability to distinguish between compression (positive hydrostatic pressure) and tension (negative hydrostatic pressure) [12].

Table 1: Stress Contributions from Common Force Field Potential Terms

| Potential Type | Energy Function | Principal Stress Contribution |

|---|---|---|

| Bond | E = (1/2)kb(r-r0)2 | σ = (1/3V)kb(r-r0)r |

| Angle | E = (1/2)kθ(θ-θ0)2 | σ = (1/3V)kθ(θ-θ0) × [ (rijcos(θ)-rjk) / (sin(θ)rijrjk) ] (rij + rjk) |

| Dihedral | E = kφ[1+cos(nφ-δ)] | σ = (1/3V)kφsin(nφ-δ) × n × (rjk / (sin(θ2)rijrkl)) × (rij + rjk + rkl) |

| Coulomb | E = (1/4πε0)qiqj/rij | σ = (1/3V)(1/4πε0)qiqj/rij |

| van der Waals | E = 4ε[(σ/rij)12 - (σ/rij)6] | σ = (1/3V)24ε[2(σ/rij)12 - (σ/rij)6] |

| Generalized Born | E = - (1/2)Σi,j(1/εin - 1/εout)qiqj/fGB(rij) | σ = (1/3V)(1/2)(1/εin - 1/εout)qiqj × [1/(fGB(rij)2) - (rij2/(2αiαjfGB(rij)3))] × (∂fGB/∂rij) |

Using the identity trace(A+B) = trace(A) + trace(B), the total stress at an atom can be obtained as the sum of contributions from potential terms in additive force fields, including bonds, angles, dihedrals, van der Waals, Coulomb, and implicit solvation terms [12]. This decomposition capability provides valuable mechanistic insights into which interactions dominate mechanical response in specific molecular regions.

Computational Protocols for Stress-Strain Analysis

MD Simulation with Controlled Deformation

This protocol outlines the procedure for simulating stress-strain response using controlled deformation in MD simulations, adapted from polyacetylene chain stretching methodology [9].

Step 1: System Preparation and Force Field Selection

- Import the molecular structure into your MD simulation package

- Select an appropriate force field for your material (e.g., CHO.ff for organic polymers) [9]

- Ensure proper system solvation or periodic boundary conditions

- Energy minimize the system to remove bad contacts

Step 2: Molecular Dynamics Parameters

- Set the number of MD steps to 850,000 for sufficient sampling [9]

- Configure sampling frequency at 1,000 steps and checkpoint frequency at 50,000 steps [9]

- Apply a thermostat (Nose-Hoover or NHC) with temperature set to 300.15 K and damping constant of 100.0 fs [9]

- For constant strain rate simulations, implement deformation with length velocity of 0.00002 Å/fs along the desired axis [9]

Step 3: Stress Tensor Calculation

- Enable stress tensor calculation in the properties settings [9]

- For accurate virial calculation, avoid bond-length constraints when possible as they can introduce errors [12]

- Set appropriate cutoffs for non-bonded interactions (typically 10 Å) [12]

- Configure trajectory output to include atomic coordinates and forces

Step 4: Simulation Execution and Monitoring

- Run the simulation and monitor progress

- Use visualization tools (e.g., AMSmovie) to observe structural changes under strain [9]

- Verify that stress tensor components are being recorded throughout the deformation

Atomistic Stress Calculation from MD Trajectories

This protocol describes the post-processing calculation of atomistic stresses from existing MD trajectories using specialized software such as CAMS (Calculator of Atomistic Mechanical Stress) [12].

Step 1: Input File Preparation

- Obtain GROMACS format files: index file (.ndx), topology file (.tpr), and binary trajectory file (*.trr)

- For simulations from other packages (AMBER, CHARMM, NAMD), convert files to supported formats

- For explicit solvent with periodic boundaries, image/wrap trajectory coordinates with solute centered in the simulation box [12]

Step 2: Software Configuration

- Install CAMS software from the GitHub repository (https://github.com/afenley/CAMS) [12]

- Configure calculation parameters including cutoff distance (default 10 Å) [12]

- Select whether to include kinetic energy term (if velocity information is available) [12]

- Specify stress component decomposition if required (bonded, nonbonded, Generalized Born) [12]

Step 3: Stress Calculation Execution

- Run CAMS to compute atomic stresses for each trajectory frame

- Generate output files containing total stress per atom and per residue

- For fluctuating systems, compute mean square fluctuation of stress per atom or residue [12]

Step 4: Visualization and Analysis

- Visualize stress distributions using molecular visualization software (VMD) [12]

- Identify regions of tension (negative hydrostatic pressure) and compression (positive hydrostatic pressure) [12]

- Correlate stress patterns with structural features and deformation mechanisms

Figure 1: Workflow for Atomistic Stress-Strain Analysis via Molecular Dynamics

Advanced Analysis Techniques

Stress-Strain Curve Interpretation

The analysis of stress-strain curves from MD simulations requires specialized approaches distinct from macroscopic testing. The Regression Fringe Response (RFR) method has been developed specifically for automated interpretation of stress-strain curves from molecular dynamics loading simulations of amorphous polymers [3]. This data-driven approach helps remove subjectivity from the analysis process by synergistically combining physics principles with data processing algorithms.

In practice, stress-strain curves from MD simulations reveal distinct segments corresponding to various molecular configurations and deformation mechanisms. For example, in polyacetylene chains under tension, the initial cis-configuration undergoes transition as bonds convert to trans-configurations under strain, manifesting as different slopes on the stress-strain graph [9]. Ultimately, at a critical strain point, the chain may fracture, immediately reducing stress to zero as the periodic polymer chain transforms into disconnected molecular entities [9].

Table 2: Critical Points in Nanoscale Stress-Strain Curves

| Feature | Molecular Significance | Identification Method |

|---|---|---|

| Elastic Limit | Onset of reversible structural distortion | Deviation from linear stress-strain relationship |

| Yield Point | Initiation of permanent structural rearrangement | First maximum in stress values |

| Configuration Transition | Molecular rearrangement (e.g., cis-to-trans) | Change in curve slope with constant or slightly decreasing stress |

| Ultimate Strength | Maximum stress before failure | Global maximum in stress values |

| Fracture Point | Structural failure and bond breaking | Abrupt stress drop to near-zero values |

Integration with Machine Learning

The combination of MD with machine learning (ML) presents a promising approach to overcome computational limitations of pure simulation methods [11]. ML algorithms can be trained on MD-generated data to create surrogate models that efficiently approximate stress-strain behavior while capturing complex interactions that challenge traditional MD simulations [11]. Gaussian Processes (GPs) within a Bayesian framework offer particular advantage for nanoscale stress-strain prediction as they provide a posterior distribution over functions, enabling predictions with quantified uncertainty [11]. This probabilistic approach addresses a key limitation of deterministic ML algorithms that cannot account for prediction uncertainty.

Hierarchical Bayesian modeling seamlessly incorporates probabilistic elements to model intricate relationships in data while accounting for uncertainty, enabling information sharing and modeling of complex dependencies [11]. This approach simultaneously addresses both the deterministic nature of traditional models and limitations stemming from separate prediction of correlated stress-strain parameters.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Atomistic Stress-Strain Analysis

| Tool/Software | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| CAMS (Calculator of Atomistic Mechanical Stress) | Computes atomic resolution stresses from MD trajectories; enables stress decomposition [12] | Post-processing analysis of GROMACS, AMBER simulations; biomolecular and nanomaterials |

| LAMMPS | MD simulation with built-in atomistic stress calculation; fix deform command for controlled deformation [10] | Material science applications; complex deformation scenarios; diverse crystal structures |

| GROMACS | High-performance MD simulation engine; generates trajectory files compatible with CAMS [12] | Biomolecular systems; explicit solvent simulations |

| ReaxFF | Reactive force field for MD simulations with bond formation/breaking [9] | Polymer mechanical testing; chemical reactions under mechanical stress |

| AMS with Python | Scriptable MD environment with stress-strain analysis capabilities [9] | Automated high-throughput screening; parametric studies of mechanical properties |

| Gaussian Processes Bayesian Framework | ML approach for predicting stress-strain curves with uncertainty quantification [11] | Surrogate modeling; parameter space exploration beyond direct MD simulation limits |

Visualization Methods

Effective visualization of atomistic stress data is essential for interpretation and communication of results. The following diagram illustrates the computational workflow for stress tensor calculation from atomic interactions:

Figure 2: Atomistic Stress Calculation Methodology from Atomic Interactions

Atomistic stress-strain analysis through molecular dynamics provides unprecedented insight into mechanical behavior at the nanoscale. The protocols outlined herein enable researchers to rigorously compute stress distributions within molecular systems, connect local stresses to specific atomic interactions, and extract meaningful mechanical properties from computational experiments. Emerging methodologies that integrate machine learning with MD simulations offer promising avenues to overcome computational limitations and expand exploration of parameter space [11]. As these techniques continue to mature, they will increasingly enable predictive materials design and fundamental understanding of mechanochemical phenomena in biological and synthetic systems.

The specialized tools and methods described, including CAMS for stress calculation [12], deformation protocols for stress-strain curve generation [9], and advanced analysis approaches like the Regression Fringe Response method [3], collectively provide researchers with a comprehensive toolkit for investigating the physics behind stress-strain relationships at the atomic scale.

Advantages of MD over Experimental Methods for Nanoscale Mechanical Testing

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation has emerged as a powerful computational technique for probing the mechanical properties of materials at the nanoscale. While experimental methods like atomic force microscopy (AFM) provide valuable data, MD offers unique advantages for investigating phenomena inaccessible to direct measurement. This document outlines the core strengths of MD for nanomechanical characterization, provides protocols for implementing these methods, and presents visual workflows for stress-strain analysis within MD research frameworks.

MD enables researchers to obtain dynamic material data at atomic spatial resolution and picosecond or finer temporal resolution, revealing mechanisms that occur over very short time periods and involve only a few atoms [13]. The decreasing cost of computational resources has led to increased MD adoption for examining phenomena that cannot be resolved experimentally and for generating hypotheses that direct further experimental research [13].

Comparative Advantages of MD Simulations

Key Advantages Over Experimental Techniques

Table 1: Comparative analysis of MD simulations versus experimental methods for nanoscale mechanical testing.

| Feature | Molecular Dynamics (MD) | Experimental Methods (e.g., AFM) |

|---|---|---|

| Spatial Resolution | Atomic-level (Ångström scale) [13] | Limited by tip geometry and sample deformation (nanometer scale) [14] |

| Temporal Resolution | Picosecond or finer [13] | Millisecond to second range [14] |

| Environmental Control | Perfect control over temperature, pressure, and composition [2] | Sensitive to environmental conditions (temperature, humidity, vibration) [14] |

| Data Completeness | Full atomic trajectories and energies [13] [15] | Indirect measurements requiring interpretation models [14] |

| Parameter Variation | Easy modification of system parameters (e.g., mutation studies) [13] | Requires new sample preparation for each variation [14] |

| Sample Preparation | No physical artifacts from sample preparation [2] | Sensitive to substrate effects, surface roughness, and contamination [14] |

| Cost and Throughput | High initial computational cost but low marginal cost for repeated tests [13] [2] | High equipment costs and limited throughput [14] |

Quantitative Validation of MD Predictions

Table 2: Validation of MD predictions against experimental data for mechanical properties of polyimides [2].

| Material | Property | MD Prediction (OPLS-AA) | Experimental Value | Error |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kapton (PMDA-ODA) | Young's Modulus | 6.8-7.5 GPa | 7.2 GPa [2] | <5% |

| Kapton (PMDA-ODA) | Poisson's Ratio | 0.38-0.42 | 0.39 [2] | <8% |

| PMDA-BIA | Young's Modulus | 8.2-9.1 GPa | Limited experimental data [2] | - |

MD Analysis Methods for Mechanical Properties

Core Analysis Techniques

MD simulations generate massive amounts of trajectory data, requiring specialized analysis methods to extract mechanical properties [13] [15]. The most fundamental analysis techniques include:

Stress-Strain Calculations: MD simulations can directly compute stress from viral theorem and correlate with strain through controlled deformation [2]. The Regression Fringe Response (RFR) method provides automated interpretation of stress-strain curves for mechanical property prediction [3].

Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) and Fluctuation (RMSF): These traditional measures quantify structural stability and flexibility over time using Equation 1 [13]:

D(M,Q) = 1/n ∑||mₖ - qₖ||[13]where M is the reference structure and Q is the trajectory structure.

Solvent Accessible Surface Area (SASA): Measures surface area accessible to solvent, detecting structural changes and solvent exposure events [13].

Principal Component Analysis: Identifies major modes of collective motion in proteins and materials by filtering out less significant fast vibrations [13].

Contact-based Analyses: Examine inter-atomic contacts over time through fine detail structural analysis or contact maps for identifying major conformational changes [13].

Specialized Mechanical Property Extraction

For direct mechanical characterization, MD implements two primary approaches:

Continuous Deformation Mode: Applies constant strain rate to simulate tensile testing, successfully replicating experimental stress-strain curves for materials like polyimides [2].

Relaxation Mode Analysis: Calculates properties from fluctuations at equilibrium using stress autocorrelation functions, suitable for isotropic materials [2].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: MD Stress-Strain Analysis for Amorphous Polymers

This protocol describes the analysis of stress-strain curves from MD simulations of amorphous polymers using the Regression Fringe Response method [3].

Materials and Software Requirements

- LUNAR parameterization environment [3]

- Molecular dynamics simulation software (e.g., LAMMPS [2])

- Python implementation of RFR method [3]

- Analysis scripts for stress-strain curve interpretation [3]

Procedure

- System Preparation

Force Field Selection

Deformation Simulation

Stress-Strain Analysis with RFR Method

Troubleshooting Tips

- If simulation results deviate from experimental data, verify force field parameters and system equilibration [2]

- For unstable simulations, reduce deformation rate and check temperature/pressure controls [2]

Protocol 2: Nanomechanical AFM Characterization for Soft Materials

This protocol details experimental AFM characterization for comparison with MD predictions [14].

Materials and Equipment

- Atomic force microscope with capability for nanomechanical imaging [14]

- Appropriate cantilevers for soft materials [14]

- Flat substrates (mica, silicon, or atomically flat gold) [14]

- Sample preparation reagents (poly-lysine, APTES, or PEI for surface functionalization) [14]

Procedure

- Sample Preparation

- Clean substrates thoroughly to remove contaminants [14]

- For polymers, use spin coating or drop casting to create uniform films [14]

- Ensure sample thickness sufficient to prevent substrate effects (>10× indentation depth) [14]

- For biomolecules, functionalize mica surfaces with poly-lysine to promote binding [14]

Cantilever Selection and Calibration

Measurement Optimization

Data Analysis and Comparison with MD

Visualization of Workflows

MD Stress-Strain Analysis Workflow

MD Stress-Strain Analysis Pathway

Multi-scale Analysis Framework

Multi-scale Analysis Framework

The Scientist's Toolkit

Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Essential tools and reagents for MD-based nanomechanical characterization.

| Tool/Reagent | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| LAMMPS | Molecular dynamics simulator [2] | Open-source, highly flexible for polymer systems |

| OPLS-AA Force Field | Describes interatomic interactions [2] | Accurate for polyimides and various polymers |

| Moltemplate | LAMMPS input file generation [2] | Facilitates polymer system setup |

| Python RFR Implementation | Automated stress-strain analysis [3] | Reduces subjectivity in curve interpretation |

| oxDNA | Coarse-grained DNA simulations [16] | Specialized for DNA origami structures |

| Atomic Flat Substrates | Experimental validation [14] | Mica, silicon, or gold for AFM samples |

| Functionalization Reagents | Sample immobilization [14] | Poly-lysine, APTES, or PEI for specific binding |

MD simulations provide unparalleled advantages for nanoscale mechanical testing, offering atomic-resolution insights into deformation mechanisms and material responses. The integration of computational approaches with experimental validation creates a powerful framework for understanding material behavior across length scales. The protocols and methodologies presented here enable researchers to implement robust MD stress-strain analyses that complement and enhance traditional experimental techniques, accelerating the development of novel materials with tailored mechanical properties.

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations have become an indispensable tool in materials and drug discovery research, serving as a "microscope with exceptional resolution" for observing atomic-scale dynamics [17]. Within this context, stress-strain analysis via MD provides critical insights into the mechanical properties of materials, from polymers to novel nanomaterials [9] [17]. The reliability of such analysis is fundamentally dependent on rigorous pre-simulation planning, particularly in defining precise scientific questions and selecting appropriate molecular systems. This protocol outlines the essential considerations researchers must address before initiating MD simulations to ensure generated data is both scientifically valid and computationally efficient. The following sections provide a structured framework for establishing research objectives, selecting molecular systems, and designing simulation protocols specifically for stress-strain investigations.

Defining the Scientific Question

A well-defined scientific question establishes the foundation for any successful MD simulation and should align with the empirical principles of scientific inquiry [18]. The process involves characterizations and hypothesis formation based on existing knowledge [18].

Table 1: Elements of Scientific Inquiry in MD Simulation Planning

| Element | Description | Application to MD Stress-Strain Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Characterizations | Observations, definitions, and measurements of the subject of inquiry [18] | Collect existing experimental data on material mechanical properties; define specific material behaviors of interest (e.g., elasticity, fracture points) |

| Hypotheses | Theoretical, hypothetical explanations of observations and measurements [18] | Formulate testable predictions about atomic-level deformation mechanisms or structure-property relationships |

| Predictions | Inductive and deductive reasoning from the hypothesis or theory [18] | Deduce expected patterns in stress-strain curves or deformation pathways under specific conditions |

| Experiments | Tests of all of the above [18] | Design MD simulation parameters to explicitly test hypotheses about mechanical behavior |

The scientific method in this context is iterative rather than linear, cycling through hypothesis formation, testing, analysis, and refinement [18]. For stress-strain analysis, this process might begin with the observation that a polymer chain undergoes specific conformational changes before fracture. The researcher would then develop a hypothesis about the critical strain at which these changes occur, predict the stress value at the fracture point and the molecular mechanisms involved [9], and design simulations to test these predictions. Each iteration refines the understanding of the relationship between atomic structure and macroscopic mechanical properties.

System Selection Criteria

Selecting an appropriate molecular system requires balancing computational feasibility with scientific relevance. Several interrelated factors must be considered to ensure the system can adequately address the research question while remaining computationally tractable.

Table 2: Molecular System Selection Criteria for MD Stress-Strain Analysis

| Criterion | Considerations | Impact on Simulation |

|---|---|---|

| System Size | Number of atoms; Spatial dimensions | Smaller systems reduce computational cost but may introduce size artifacts; must be large enough to capture relevant material behavior [17] |

| Composition | Chemical complexity; Homogeneity/heterogeneity | Pure systems versus alloys or composites; presence of dopants or defects; accurate force field parameter availability [17] |

| Initial Structure | Crystalline/amorphous; Source of coordinates | Crystal structure databases (Materials Project, AFLOW); experimental data; predicted structures (AlphaFold2 for proteins) [17] |

| Boundary Conditions | Periodicity; System confinement | 1D, 2D, or 3D periodicity; vacuum boundaries; appropriate for target material and deformation mode [9] |

The initial structure preparation is particularly critical, as inaccuracies at this stage propagate through the entire simulation [17]. Structures obtained from databases frequently require reconstruction of missing atoms or regions. For novel materials not present in databases, initial structures must be built from scratch based on experimental data or theoretical predictions. The emergence of AI-generated structures like AlphaFold2 has simplified this process, but expert validation remains essential to ensure physical and chemical plausibility [17].

Experimental Protocol for Stress-Strain Analysis

This section provides a detailed methodology for setting up MD simulations specifically for stress-strain analysis of polymer systems, based on established protocols [9].

System Setup and Equilibration

Begin by importing the molecular structure of the system to be analyzed. For polymer chains like polyacetylene, ensure proper chain alignment relative to the deformation axis, particularly when using 1D periodic boundaries [9]. Select an appropriate force field that accurately captures the interatomic interactions relevant to mechanical deformation (e.g., CHO.ff for organic polymers) [9]. Initialize the system with velocities sampled from a Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution corresponding to the target simulation temperature (e.g., 300.15 K) [17].

Deformation Parameters

Configure the deformation settings to apply controlled strain along the desired axis:

- Set the length velocity parameter to control the strain rate (e.g., 0.00002 Å/fs for gradual deformation) [9]

- Define the number of steps sufficient to achieve the desired total strain (e.g., 850,000 steps) [9]

- Establish appropriate sampling and checkpoint frequencies (e.g., 1000 and 50,000 steps, respectively) to capture the deformation process without excessive storage requirements [9]

Simulation Execution

Run the molecular dynamics simulation with the following key parameters:

- Apply a thermostat to maintain constant temperature (e.g., NHC thermostat with a damping constant of 100.0 fs) [9]

- Enable stress tensor calculation to monitor mechanical response during deformation [9]

- Use a time step of 0.5-1.0 femtoseconds to accurately capture atomic motions while maintaining computational efficiency [17]

Data Collection and Analysis

Upon completion, extract stress and strain data from the simulation trajectory. For polyacetylene, this reveals distinct segments in the stress-strain curve corresponding to conformational changes (cis-to-trans bond conversion) followed by fracture at critical strain [9]. Calculate key mechanical properties:

- Young's modulus from the slope of the linear elastic region

- Yield stress at the point where plastic deformation begins

- Tensile strength as the maximum stress before fracture [17]

Use Python scripts with PLAMS library to extract quantitative stress-strain data for further analysis and visualization [9].

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow for pre-simulation planning and execution of MD stress-strain analysis:

Pre-Simulation Planning and MD Stress-Strain Analysis Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This section details essential computational tools and parameters required for MD stress-strain simulations.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for MD Stress-Strain Analysis

| Tool/Parameter | Type/Function | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Force Fields | Mathematical models describing interatomic potentials | CHO.ff for organic polymers; machine learning interatomic potentials (MLIPs) for complex systems [9] [17] |

| Structure Databases | Repositories of initial atomic coordinates | Materials Project, AFLOW for crystals; PDB for biomolecules; PubChem for small molecules [17] |

| Deformation Parameters | Settings controlling strain application | Length velocity (e.g., 0.00002 Å/fs); deformation axis; number of steps [9] |

| Thermostats | Algorithms maintaining constant temperature | NHC thermostat with damping constant (e.g., 100.0 fs) at 300.15 K [9] |

| Analysis Tools | Software for extracting mechanical properties | PLAMS library for stress-strain curve extraction; Python scripts for data processing [9] |

| Time Integration Algorithms | Numerical methods for solving equations of motion | Verlet algorithm or leap-frog method with 0.5-1.0 fs time steps [17] |

These computational "reagents" form the essential toolbox for designing and executing MD simulations for stress-strain analysis. Proper selection of each component directly influences the accuracy, efficiency, and reliability of the simulation results.

Hands-On Protocols: Setting Up and Running Deformation Simulations

Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations have become an indispensable tool in computational materials science, functioning as a "microscope with exceptional resolution" to reveal atomic-scale processes [17]. This protocol provides a detailed, tutorial-based approach for performing stress-strain analysis of materials using MD, a method that calculates the relationship between applied deformation (strain) and the resulting internal resistance (stress) within a material [17]. Such analysis enables researchers to extract key mechanical properties—including Young's modulus, yield stress, and tensile strength—directly from atomic-scale simulations, providing insights that complement and often guide experimental materials design [17]. The workflow is critical for understanding the mechanical behavior of polymers, metals, ceramics, and nanomaterials under various conditions.

Theoretical Background

In MD-based stress-strain analysis, mechanical deformation is simulated by applying a controlled strain to the simulation cell. The strain (( \epsilon )) is a dimensionless measure of deformation representing the displacement between particles in the material relative to its initial length. The resulting stress (( \sigma )), a measure of internal force distribution, is typically calculated via the virial theorem from atomic positions and forces [17].

The stress-strain curve generated from this process reveals fundamental mechanical properties:

- Young's Modulus (E): The slope of the initial linear elastic region (( E = \frac{\Delta \sigma}{\Delta \epsilon} )), representing material stiffness.

- Yield Stress: The stress point where the material transitions from elastic (reversible) to plastic (permanent) deformation.

- Tensile Strength: The maximum stress the material can withstand before failure [17].

For polymers like the cis-Polyacetylene chain featured in this protocol, the stress-strain curve exhibits distinct segments corresponding to molecular rearrangements, such as the transition from cis- to trans-configurations, before ultimate fracture [9].

Protocol: Stress-Strain Analysis of a Polymer Chain

System Preparation and Initial Structure

Objective: Prepare an initial atomic structure suitable for MD simulation.

- Step 1: Obtain or build the initial molecular structure. For this protocol, we use a cis-Polyacetylene chain [9].

- Step 2: Import the structure into your MD simulation environment. In this example, we use the AMS software interface [9]:

- Start AMSjobs

- Select

SCM → New input - Switch to the appropriate force field (ReaxFF in this case)

Simulation Setup and Deformation Parameters

Objective: Configure the molecular dynamics parameters to simulate stretching.

- Step 1: Set the main MD parameters [9]:

- Number of steps: 850,000

- Sampling frequency: 1000

- Checkpoint frequency: 50,000

- Step 2: Configure the thermostat for temperature control:

- Thermostat type: Nose-Hoover (NHC)

- Temperature: 300.15 K

- Damping constant: 100.0 fs

- Step 3: Set up the deformation to stretch the polymer chain [9]:

- Navigate to

Model → MD... → Deformations - Add a deformation

- Set Length velocity: 0.00002 Å/fs (This value controls the strain rate)

- Navigate to

- Step 4: Enable stress tensor calculation:

- Go to

Properties → Gradients, Stress Tensor - Check Stress Tensor

- Go to

Execution and Preliminary Visualization

Objective: Run the simulation and monitor the deformation process.

- Step 1: Save the input file as "PolyStressStrain" and execute the calculation [9].

- Step 2: Monitor the simulation progress and visualize structural changes in real-time:

- Open AMSmovie by clicking

SCM → Movie - Observe the polymer chain conformation changes under increasing strain

- Open AMSmovie by clicking

Results Extraction and Analysis

Objective: Extract stress-strain data and identify key mechanical properties.

- Step 1: Plot the stress-strain curve in AMSmovie [9]:

- Select

MD Properties → Stress/Strain → YY - Identify distinct segments in the curve corresponding to different molecular configurations

- Select

- Step 2: Perform linear regression analysis to determine Young's Modulus [9]:

- Select

Graph → Analysis - Choose

Curve: Stress YY - Navigate to the

Linear Regressiontab - Restrict the x-range to the first linear segment (e.g., 0 to 0.05 strain)

- Record the regression coefficient (slope = Young's Modulus)

- Select

- Step 3: Extract numerical data for further analysis using a Python script [9]:

- Execute:

$AMSBIN/amspython stress_strain_curve.py PolyStressStrain - This generates a CSV file (

stress-strain-curve.csv) with strain and stress values

- Execute:

The table below summarizes the key parameters used in the MD simulation for stress-strain analysis:

Table 1: Key Parameters for MD Stress-Strain Simulation

| Parameter Category | Specific Parameter | Value/Setting | Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Dynamics | Number of Steps | 850,000 | Total simulation time |

| Sampling Frequency | 1000 | Interval for recording data | |

| Checkpoint Frequency | 50,000 | Interval for saving simulation state | |

| Temperature Control | Thermostat Type | Nose-Hoover (NHC) | Maintain constant temperature |

| Temperature | 300.15 K | Simulation temperature (approx. 27°C) | |

| Damping Constant | 100.0 fs | Coupling strength to the heat bath | |

| Deformation | Length Velocity | 0.00002 Å/fs | Rate of applied strain |

| Analysis | Stress Tensor | Enabled | Calculate stress components |

Figure 1: The sequential workflow for conducting stress-strain analysis through Molecular Dynamics simulations, from initial structure preparation to final property identification.

Data Analysis and Interpretation

Quantitative Stress-Strain Data

The following table presents exemplary data extracted from a Polyacetylene stress-strain simulation, showing the progression of strain and the corresponding stress response in the YY direction:

Table 2: Exemplary Stress-Strain Data from MD Simulation

| Strain_y | Stress_yy | Strain_y | Stress_yy |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.0000 | 0.00004145 | 0.0132 | 0.00005057 |

| 0.0026 | 0.00003945 | 0.0158 | 0.00006138 |

| 0.0053 | 0.00004038 | 0.0184 | 0.00005314 |

| 0.0079 | 0.00003917 | 0.0211 | 0.00004633 |

| 0.0105 | 0.00005021 |

Interpretation of Molecular Transitions

The stress-strain curve reveals distinct molecular-level events [9]:

- Initial Linear Region: The slope provides Young's modulus, reflecting the energy required for elastic bond stretching and angle bending.

- Configuration Transition: The curve deviation from linearity corresponds to cis- to trans-bond conversion in Polyacetylene, a structural rearrangement that dissipates energy.

- Plastic Region: Further strain induces irreversible molecular slippage and chain reorientation.

- Fracture Point: The stress drops abruptly to zero as the polymer chain snaps, terminating the load-bearing capacity.

Figure 2: The data analysis process transforms raw simulation data into meaningful mechanical properties and molecular insights.

Table 3: Essential Tools and Resources for MD Stress-Strain Analysis

| Tool/Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Simulation Software | AMS (Amsterdam Modeling Suite) [9] | Integrated platform for setting up, running, and visualizing MD simulations with deformation. |

| Force Fields | ReaxFF (CHO.ff) [9] | Empirical potential describing atomic interactions, bond formation, and breaking during deformation. |

| Visualization Tools | AMSmovie [9] | Visual monitoring of structural changes, plotting of MD properties, and curve analysis. |

| Data Analysis | Python with PLAMS library [9] | Scripting interface to extract numerical data (e.g., stress-strain curves) from binary results. |

| Data Visualization | Matplotlib [9], Plotly [19] | Libraries for creating publication-quality plots from extracted data. |

| Structure Databases | Materials Project [17], PubChem [17] | Sources for initial crystal or molecular structures when studying known materials. |

| Specialized Analysis | Principal Component Analysis [17] | Technique to extract essential collective motions from complex MD trajectory data. |

Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulation serves as a computational microscope, enabling researchers to observe the atomistic behavior of materials under mechanical deformation. Within the context of stress-strain analysis, MD provides unparalleled insights into the fundamental mechanisms of elasticity, plasticity, and failure by tracking the temporal evolution of atomic positions and forces. The accuracy and efficiency of these simulations critically depend on two foundational choices: the MD software package and the empirical force field. This application note provides a comprehensive overview of popular MD packages (LAMMPS, GROMACS, AMS, NAMD) and force fields, with detailed protocols for conducting reliable stress-strain analysis.

Molecular Dynamics Software Packages

The selection of an MD package dictates the scale, efficiency, and type of problems you can address. The following section compares four prominent software tools.

Comparative Analysis of MD Packages

Table 1: Feature Comparison of Major Molecular Dynamics Software Packages

| Feature | LAMMPS | GROMACS | NAMD | AMS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Application Domain | Materials science, solid-state physics, polymers [20] | Biomolecules (proteins, lipids, nucleic acids) [20] | Biomolecular systems, large complexes [8] | Materials science, heterogeneous catalysis |

| Strengths | Exceptional flexibility, modularity, broad particle support [20] | High performance and efficiency on biomolecules [20] | Efficient parallel scaling for large biomolecular systems [8] | Density Functional Theory (DFT), multi-scale modeling |

| User Interface | Input scripts, command-line [20] | Command-line tools [20] | Configuration files, scripting | Graphical User Interface (GUI) |

| Parallelization & Performance | Excellent scaling to thousands of processors; GPU/CPU support [20] | Highly optimized for biomolecules; strong GPU acceleration [20] | Designed for parallel execution on large supercomputers [8] | Efficient for quantum-chemical calculations |

| Licensing | Open Source (GPL) [20] | Open Source [20] | Open Source | Commercial |

| Best Suited for Stress-Strain Analysis of | Metals, polymers, nanomaterials [20] | Biological tissues, protein filaments [20] | Large biological complexes | Surface mechanics, chemical reactions under strain |

Detailed Package Profiles

LAMMPS (Large-scale Atomic/Molecular Massively Parallel Simulator): Developed at Sandia National Laboratories, LAMMPS is designed for flexibility and modularity. Its core strength lies in simulating a vast range of material types—from atomic and molecular to mesoscopic and continuum models—making it ideal for studying mechanical properties in polymers, metals, and granular materials [20]. It can be extended with user-developed code and plugins, allowing for custom stress-strain routines [20].

GROMACS (Groningen Machine for Chemical Simulations): Originally developed for biochemical molecules, GROMACS is renowned for its exceptional simulation speed and efficiency, particularly on GPU hardware. It is the package of choice for stress-strain analysis of biological systems such as cytoskeletal networks, protein filaments like actin and collagen, and lipid bilayers [20].

NAMD: NAMD is specifically designed for high-performance simulation of large biomolecular systems. It scales efficiently on parallel computing architectures and integrates seamlessly with the CHARMM and AMBER force fields. It is particularly well-suited for simulating large complexes like viral capsids or cellular machinery under mechanical stress [8].

AMS (Amsterdam Modeling Suite): While several packages focus on classical MD, the AMS suite provides a robust platform for quantum-mechanical (DFT) and semi-empirical methods. This is crucial for stress-strain analysis where chemical bond breaking and formation are involved, such as in fracture mechanics of crystalline materials or catalysis on strained surfaces.

Force Fields for Molecular Dynamics

The force field defines the potential energy surface of a system and is therefore paramount for obtaining physically meaningful results from stress-strain simulations.

Table 2: Common Additive Force Fields for Biomolecular Simulations [8]

| Force Field | Class | Key Characteristics | Recommended for Stress-Strain Analysis of |

|---|---|---|---|

| CHARMM36 | Additive | Balanced backbone (CMAP) and side-chain parameters; broad coverage of biomolecules [8]. | Proteinaceous materials, lipid bilayers. |

| AMBER (ff99SB-ILDN) | Additive | Optimized backbone and side-chain torsions; widely used in protein folding studies [8]. | Intrinsically disordered proteins and peptides under shear. |

| GROMOS | Additive | Unified atom parameterization; often used with specific water models. | Polymers and biomolecules in a condensed phase. |

| OPLS-AA | Additive | Optimized for liquid properties; good for organic molecules and peptides. | Organic crystals and polymer blends. |

Polarizable Force Fields

Additive force fields use fixed atomic partial charges, which is a significant approximation. Polarizable force fields, such as the Drude model and AMOEBA, allow for a more physical response of the electronic distribution to the changing environment [8]. This is particularly important in stress-strain analysis of heterogeneous or charged systems, where the electronic polarization can significantly affect mechanical properties. The Drude model, for instance, introduces auxiliary particles to represent electronic degrees of freedom, leading to a more accurate description of dielectric properties [8].

Experimental Protocols for Stress-Strain Analysis

This section provides a step-by-step methodology for performing a uniaxial tensile test using MD simulations.

Protocol: Uniaxial Tensile Deformation of a Nanocrystalline Metal (using LAMMPS)

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Atomic Structure: Pre-equilibrated nanocrystalline aluminum sample. Function: The model system representing the material under investigation.

- Force Field: EAM (Embedded Atom Method) potential for aluminum. Function: Describes the metallic bonding and interactions between atoms.

- Minimization Algorithm: Conjugate gradient method. Function: Relaxes the structure to the nearest local energy minimum, removing artificial high stresses.

- Ensemble Controls: Nose-Hoover thermostat and barostat. Function: Maintains constant temperature and pressure during equilibration phases.

- Integrator: Velocity Verlet. Function: Numerically solves Newton's equations of motion to update atomic positions and velocities.

Procedure:

- System Preparation: Generate or import an atomic structure of a nanocrystalline metal with a defined grain size and distribution.

- Energy Minimization: Use the conjugate gradient algorithm to minimize the system's potential energy until the force tolerance reaches 1.0e-6 eV/Å. This step is critical for obtaining a stable starting configuration.

- Equilibration (NPT): Equilibrate the system in the isothermal-isobaric (NPT) ensemble at 300 K and 1 atm pressure for 50-100 ps. This allows the density and internal structure of the material to relax to equilibrium under realistic conditions.

- Equilibration (NVT): Switch to the canonical (NVT) ensemble and equilibrate for an additional 50 ps. This stabilizes the temperature at the desired value for the deformation step.

- Uniaxial Deformation: Apply a constant engineering strain rate (e.g., 1e9 s⁻¹) along the desired crystallographic direction (e.g., Z-axis) by progressively scaling the atomic coordinates and simulation box length in that direction. The stress tensor is calculated at each timestep using the Virial theorem.

- Data Analysis: Calculate the Cauchy stress from the Virial stress. Plot the stress versus applied strain to generate the stress-strain curve. Key properties like Young's modulus (slope of the initial linear region), yield strength, and ultimate tensile strength can be extracted from this curve.

Protocol: Mechanical Response of a Protein Fibiril (using GROMACS)

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Protein Structure: PDB file of a collagen-like peptide triple helix. Function: The biological macromolecule whose mechanical function is being probed.

- Force Field: CHARMM36. Function: Accurately describes bonded and non-bonded interactions within the protein and with solvent.

- Water Model: TIP3P water molecules. Function: Represents the solvation environment, crucial for biomolecular stability.

- Neutralization Ions: Sodium or Chloride ions. Function: Neutralize the system's net charge for physical accuracy in electrostatic calculations.

- Minimization Algorithm: Steepest descent. Function: Efficiently minimizes the energy of large, solvated systems.

Procedure:

- System Setup: Solvate the protein structure in a periodic box of water molecules, ensuring a minimum clearance (e.g., 1.0 nm) from the protein to its periodic image.

- Neutralization: Add ions to neutralize the system's net charge.

- Energy Minimization: Perform energy minimization using the steepest descent algorithm until the maximum force is below a threshold (e.g., 100 kJ/mol/nm).

- Equilibration (NVT): Equilibrate the solvated system with positional restraints on the protein heavy atoms for 100 ps. This allows the solvent and ions to relax around the fixed protein.

- Equilibration (NPT): Equilibrate the system without restraints in the NPT ensemble for 1 ns to achieve the correct density.

- Production Run with Steered MD (SMD): Perform a steered MD simulation by applying a constant velocity or a constant force to one end of the protein fibril while restraining the other end. The force required to pull the fibril is recorded over time.

- Data Analysis: From the SMD simulation, plot the force versus extension curve. Analyze the rupture events and peaks in force to determine the mechanical stability and unfolding pathways of the protein.

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for a typical MD-based stress-strain analysis, integrating the components and protocols described in this document.

MD Stress-Strain Analysis Workflow

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations enable researchers to investigate the mechanical properties of materials by applying controlled deformations at the atomic scale. These simulations provide fundamental insights into material behavior under mechanical stress, allowing scientists to observe phenomena such as elastic deformation, plastic flow, and fracture mechanisms that are difficult to capture experimentally. Within the broader context of stress-strain analysis, deformation simulations serve as a computational framework for extracting critical mechanical properties including Young's modulus, yield strength, and ultimate tensile strength [21]. The implementation of these simulations requires careful consideration of deformation types, appropriate boundary conditions, and specialized algorithms for applying strain while accurately measuring the resulting stress response.

The fundamental principle underlying deformation MD simulations involves numerically integrating Newton's equations of motion for atoms while systematically modifying the simulation cell dimensions or applying forces to induce deformation [22]. Unlike Monte Carlo methods which lack explicit time evolution, MD simulations track system dynamics, making them particularly suitable for studying rate-dependent mechanical properties and time-evolving deformation mechanisms [22]. For researchers in materials science and drug development, these simulations offer atomic-level insights into structure-property relationships that can guide material design or understand biological macromolecule mechanics.

Fundamental Deformation Methods

Classification of Deformation Approaches

MD simulations support several technical approaches for implementing deformation, each with distinct advantages and applications. The primary methods include uniaxial deformation (tensile/compressive) and shear deformation, which can be implemented through various technical mechanisms.

Table 1: Comparison of Deformation Methods in Molecular Dynamics

| Method | Implementation | Measured Properties | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Uniaxial Deformation | Cell dimension scaling along specific axis [9] [21] | Young's modulus, tensile strength, fracture point [21] | Bulk materials, crystalline systems, polymers [23] |

| Simple Shear | Triclinic cell deformation with off-diagonal elements [24] | Shear viscosity, friction coefficients | Fluids, lubricants, complex fluids |

| Wall-driven Shear | Moving boundary atoms with constant velocity [24] | Wall slip, interface properties, confinement effects | Nanoconfined fluids, surface interactions |

| Cosine Acceleration | Spatially varying acceleration profile [24] | Viscosity without cell deformation | Simple liquids, rheological studies |

Uniaxial Tensile and Compression Testing

Uniaxial deformation involves systematically stretching or compressing the simulation cell along a specific Cartesian direction (x, y, or z). This is typically achieved by applying a strain rate to the cell dimensions while allowing other cell vectors to respond according to the chosen barostat conditions [9] [21]. The engineering strain is defined as the relative change from the initial unit cell length, providing a standardized measure of deformation [21]. During this process, the stress tensor is calculated from the virial expression and recorded at regular intervals, generating the fundamental stress-strain data used for property extraction.

The key advantage of uniaxial deformation lies in its direct correspondence to experimental tensile testing, enabling computational-experimental comparisons. As demonstrated in polyacetylene chain simulations, this method can capture complex phenomena such as bond breaking, phase transformations, and eventual fracture [9]. In polymer-calcite systems, uniaxial deformation has revealed interface strength properties and failure mechanisms [23]. The simulation continues until material failure occurs, as indicated by a sharp stress drop to zero, marking the fracture point [9].

Shear Deformation Methods

Shear simulations implement deformation through relative parallel motion of material layers, producing distinct flow profiles and material responses. GROMACS documentation outlines four primary approaches for achieving shear flow [24]:

- Constant acceleration groups: Applying mass-weighted forces to atom groups, causing relative motion

- Triclinic cell deformation: Deforming the unit cell directly using the

deformoption or applying off-diagonal stress through pressure coupling - Cosine acceleration profile: Using spatially varying acceleration that avoids cell deformation complications

- Wall-driven shear: Moving structured walls at constant velocity while studying confined fluid response

For systems with explicit walls, the constant velocity approach is particularly valuable, as it allows position restraining of wall atoms while maintaining controlled shear conditions [24]. This method can be implemented using the free-energy lambda-coupling code, where lambda increases proportionally with simulation time, effectively translating position restraints and moving the walls at a constant speed [24].

Experimental Protocols

General Workflow for Deformation Simulations

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive workflow for setting up and running deformation simulations in molecular dynamics:

Protocol 1: Uniaxial Tensile Testing

Objective: Determine Young's modulus and tensile strength through uniaxial deformation.

System Preparation:

- Initial Configuration: Build or obtain the atomic structure of the material system. For polymers, this may require polymer builder tools; for multi-domain proteins, use high-resolution structures of individual domains connected by flexible linkers [25].

- Energy Minimization: Relax the structure using steepest descent or conjugate gradient methods to remove high-energy contacts and inappropriate geometry.

- Equilibration:

- Perform NVT equilibration for 100-500 ps at target temperature (e.g., 300 K) using thermostats such as Nose-Hoover or velocity rescale [25]

- Conduct NPT equilibration for 100-500 ps to achieve proper density at target temperature and pressure (e.g., 1 bar) using barostats such as Parinello-Rahman or Berendsen

Deformation Configuration:

- Strain Parameters: Set the deformation direction (e.g., 'x'), strain rate, and total simulation time. Typical strain rates in MD simulations range from 10^7 to 10^9 s^-1 due to computational constraints [21].

- Implementation:

- Stress Measurement: Configure the

MDMeasurementobject or equivalent to record stress tensor components at regular intervals (e.g., every 10-100 steps) [21]

Production and Analysis:

- Run Simulation: Execute the MD simulation with applied deformation for sufficient duration to reach the desired strain or material failure

- Stress-Strain Curve: Extract stress and strain data throughout the trajectory. For uniaxial deformation, use the engineering strain and the corresponding stress component in the deformation direction

- Property Extraction:

- Young's Modulus: Calculate as the slope of the initial linear portion of the stress-strain curve through linear regression [21]

- Yield Strength: Identify as the stress value at the first deviation from linear elastic behavior

- Ultimate Tensile Strength: Determine as the maximum stress value before fracture