A Practical Guide to Setting Molecular Dynamics Parameters for Accurate Atomic Tracking

This guide provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and scientists to establish robust molecular dynamics (MD) simulation parameters specifically for precise atomic tracking.

A Practical Guide to Setting Molecular Dynamics Parameters for Accurate Atomic Tracking

Abstract

This guide provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and scientists to establish robust molecular dynamics (MD) simulation parameters specifically for precise atomic tracking. It covers foundational principles, practical setup methodologies across different software, advanced troubleshooting for common pitfalls, and rigorous validation techniques. By integrating insights from current literature and software documentation, this article empowers professionals in drug development and biomedical research to generate reliable, reproducible trajectory data for analyzing atomic-scale phenomena, from protein-ligand interactions to material diffusion processes.

Core Principles: How Key Parameters Govern Atomic Motion in MD

In molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, the integration algorithm is a cornerstone that determines the accuracy, stability, and physical fidelity of the generated atomic trajectories. These algorithms numerically solve Newton's equations of motion, enabling the prediction of how every atom in a molecular system will move over time based on a general model of the physics governing interatomic interactions [1]. The choice of integrator directly impacts the ability to capture biologically and materially relevant processes, from conformational changes in proteins to atomic diffusion in alloys. This Application Note details three prevalent integration methods—Leap-Frog, Velocity Verlet, and Stochastic Dynamics—within the context of setting up MD simulation parameters for atomic tracking research. We provide a quantitative comparison, detailed implementation protocols, and practical guidance to help researchers select and configure the appropriate integrator for their specific scientific objectives.

Integrator Fundamentals and Comparison

Mathematical Foundations and Numerical Properties

Velocity Verlet is a second-order integrator that advances the system by calculating positions and velocities at the same point in time. Its steps are [2]:

- Calculate positions at time ( t + \Delta t ): ( \mathbf{r}(t+\Delta t) = \mathbf{r}(t) + \mathbf{v}(t)\Delta t + \frac{1}{2}\mathbf{a}(t)\Delta t^2 )

- Derive accelerations ( \mathbf{a}(t+\Delta t) ) from the new positions.

- Update velocities: ( \mathbf{v}(t+\Delta t) = \mathbf{v}(t) + \frac{1}{2}[\mathbf{a}(t) + \mathbf{a}(t+\Delta t)]\Delta t )

It is time-reversible and energy-conserving, making it a robust, widely-used choice for microcanonical (NVE) ensemble simulations [2].

The Leap-Frog algorithm is a variant mathematically equivalent to Velocity Verlet but staggers the calculation of positions and velocities in time [3]. Its procedure is:

- Derive acceleration ( \mathbf{a}(t) ) from the current positions ( \mathbf{r}(t) ).

- Update velocities at half-time-steps: ( \mathbf{v}(t + \frac{\Delta t}{2}) = \mathbf{v}(t - \frac{\Delta t}{2}) + \mathbf{a}(t)\Delta t )

- Update positions to the next full-time-step: ( \mathbf{r}(t + \Delta t) = \mathbf{r}(t) + \mathbf{v}(t + \frac{\Delta t}{2})\Delta t )

While trajectories are equivalent to Velocity Verlet, the kinetic energy (and thus temperature) must be calculated from the half-step velocities, which can be less convenient [2]. A key advantage is computational efficiency, as it requires only one force evaluation per step [2].

Stochastic Dynamics (SD), also known as velocity Langevin dynamics, incorporates friction and noise to simulate coupling to a heat bath. It is essential for sampling the canonical (NVT) ensemble. In the GROMACS implementation, friction and noise are applied as an impulse [4]:

- Update velocity to an intermediate value without friction/noise: ( \mathbf{v}' = \mathbf{v}(t-\frac{\Delta t}{2}) + \frac{1}{m}\mathbf{F}(t)\Delta t )

- Apply friction and noise as an impulse: ( \Delta\mathbf{v} = -\alpha \mathbf{v}' + \sqrt{\frac{kB T}{m} \alpha (2 - \alpha)} \, {\mathbf{r}^G}i ), where ( \alpha = 1 - e^{-\gamma \Delta t} ), ( \gamma ) is the friction constant, and ( {\mathbf{r}^G}_i ) is Gaussian noise.

- Update coordinates: ( \mathbf{r}(t+\Delta t) = \mathbf{r}(t) + \left( \mathbf{v}' + \frac{1}{2}\Delta\mathbf{v} \right) \Delta t )

- Update the final velocity: ( \mathbf{v}(t+\frac{\Delta t}{2}) = \mathbf{v}' + \Delta\mathbf{v} )

This method efficiently thermostats the system and damps long-time-scale processes, making it suitable for simulating systems in vacuum and for efficient sampling [4].

Quantitative Integrator Comparison

Table 1: Comparative analysis of key integrator algorithms for molecular dynamics.

| Feature | Leap-Frog | Velocity Verlet | Stochastic Dynamics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Integration Type | Deterministic, Newtonian | Deterministic, Newtonian | Stochastic, Langevin |

| Mathematical Order | Second-order | Second-order | - |

| Time Reversibility | Yes [3] | Yes [2] | No |

| Ensemble | Microcanonical (NVE) | Microcanonical (NVE) | Canonical (NVT) |

| Thermostat Coupling | Requires external thermostat | Requires external thermostat | Built-in thermostat |

| Computational Cost | Low (1 force eval/step) | Low (1 force eval/step) | Moderate |

| Key Strength | Computational efficiency, stability | Simplicity, synchronized velocities | Efficient sampling, vacuum simulations |

| Typical Time Step | 1-4 fs (depending on constraints) [2] | 1-4 fs (depending on constraints) [2] | 1-2 fs |

GROMACS integrator keyword |

md [5] |

md-vv, md-vv-avek [5] |

sd [4] [5] |

Experimental Protocols for Atomic Tracking Research

Protocol 1: System Equilibration using Stochastic Dynamics

Purpose: To efficiently equilibrate a solvated biomolecular system or a system in vacuum to a target temperature before production simulation. Principle: Stochastic Dynamics acts as a molecular dynamics simulator with integrated stochastic temperature coupling, providing rapid equilibration of fast modes [4].

- Initial Setup: Begin with a energy-minimized structure.

- Parameter Configuration:

- Integrator:

sd[5] - Friction Constant (

tau-t): Set to 0.5-1.0 ps⁻¹ for efficient yet non-intrusive thermostatting. A value of 0.5 ps⁻¹ provides friction lower than water's internal friction [4]. - Time Step (

dt): 0.001-0.002 ps (1-2 fs) [2]. - Temperature (

ref-t): Set to the desired target temperature (e.g., 300 K).

- Integrator:

- Execution: Run the simulation for a sufficient number of steps (

nsteps) to allow the system energy and temperature to stabilize. Monitor the potential energy and root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) of the solute to confirm equilibration.

Protocol 2: Production Simulation using Velocity Verlet

Purpose: To run a production-level, energy-conserving simulation for analyzing equilibrium dynamics and conformational sampling. Principle: Velocity Verlet provides a symplectic and time-reversible integration, ideal for generating physically accurate trajectories in the NVE or NPT ensembles [2].

- Initialization: Start from the equilibrated system generated in Protocol 1.

- Parameter Configuration:

- Execution: Perform a long-timescale simulation. The trajectory can be used for subsequent analysis like calculating diffusion coefficients or radial distribution functions [6].

Protocol 3: Large-Scale Simulation using Leap-Frog

Purpose: To perform computationally efficient, large-scale simulations of material systems or large biomolecular complexes. Principle: The Leap-Frog algorithm's computational efficiency and stability make it suitable for systems requiring many integration steps [2] [7].

- System Preparation: Construct the initial atomic model, for example, a nanoparticle system as done in the study of Au-Ni coalescence [7].

- Parameter Configuration:

- Integrator:

md[5]. - Time Step (

dt): 0.001 ps (1 fs). Can be increased with constraints. - Temperature/Pressure Coupling: Use appropriate external barostats/thermostats.

- Integrator:

- Execution and Analysis: Run the simulation and analyze the trajectory for properties of interest. For example, in a nanoparticle coalescence study, one would track energy variation, atomic segregation modes, and structural evolution using techniques like common neighborhood analysis and pair distribution functions [7].

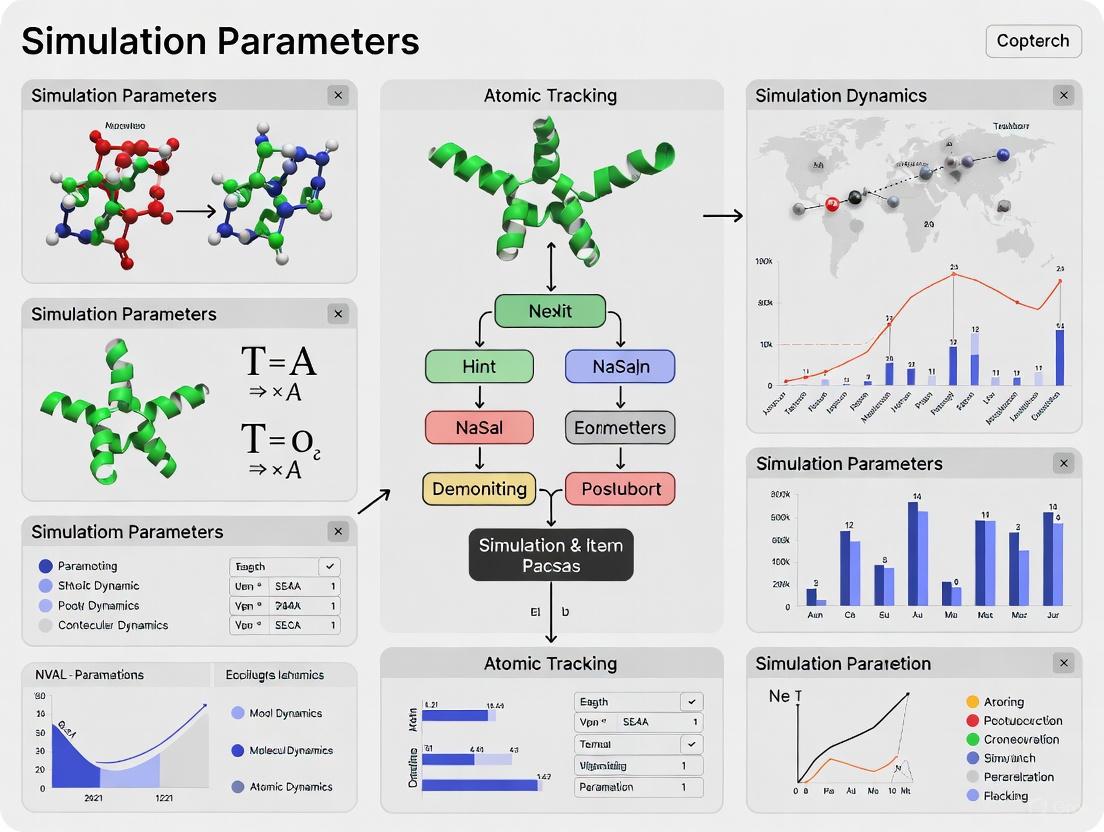

Workflow Visualization

Diagram 1: High-level workflow for MD simulations showing integrator roles.

Table 2: Key software, force fields, and analysis tools for molecular dynamics.

| Resource | Type | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| GROMACS [4] [5] | MD Software | High-performance package optimized for biomolecular simulations, offering all three integrators discussed. |

| LAMMPS [8] [7] | MD Software | Highly flexible simulator for materials modeling, suitable for large-scale metallic and alloy systems. |

| EAM Potential [8] [7] | Force Field | Describes metallic bonding in metals and alloys via electron density embedding; critical for nanoparticle studies. |

| Tersoff Potential [8] | Force Field | A bond-order potential for covalent materials like silicon and carbon; handles bond formation/breaking. |

| VMD [7] | Analysis/Visualization | Visualizes MD trajectories and analyzes structural and dynamic properties. |

| LINCS [2] | Constraint Algorithm | Constrains bond lengths, allowing for larger time steps; faster and more parallelizable than SHAKE. |

| SETTLE [2] | Constraint Algorithm | An analytical algorithm for constraining rigid water models (e.g., SPC, TIP3P) very efficiently. |

| Radial Distribution Function (RDF) [6] | Analysis Method | Quantifies short-range order in liquids/amorphous materials; validates simulation models. |

| Mean Squared Displacement (MSD) [6] | Analysis Method | Calculates diffusion coefficients from particle trajectories to evaluate molecular mobility. |

The selection of an integration algorithm is a critical parameter in the design of any molecular dynamics simulation. Leap-Frog offers raw speed and is the default in many production-level biomolecular codes like GROMACS. Velocity Verlet provides conceptual simplicity and synchronized velocities, which is advantageous for analysis and certain advanced coupling schemes. Stochastic Dynamics delivers built-in temperature control, making it ideal for equilibration and studying systems in a canonical ensemble or in vacuum. By understanding the strengths and applications of each method, as detailed in these protocols and comparisons, researchers can make informed decisions to optimize their simulations for specific atomic tracking objectives, whether in drug discovery, materials science, or fundamental biological research.

The selection of the integration time step (∆t) is a critical step in setting up a molecular dynamics (MD) simulation, as it directly governs the balance between numerical accuracy and computational cost. A time step that is too long can lead to instabilities, inaccurate dynamics, and a failure to conserve energy, while an excessively short time step results in an unnecessary and prohibitive computational burden for achieving biologically or physically relevant timescales [1]. This document outlines the fundamental principles, quantitative guidelines, and practical protocols for selecting and validating an appropriate time step within the context of atomic tracking research. The guidance is structured to assist researchers in making informed decisions that are "fit-for-purpose" for their specific scientific questions [9].

Theoretical Foundation

Molecular dynamics simulations numerically integrate Newton's equations of motion for a system of atoms. The time step defines the interval at which the forces are recalculated and the atomic positions and velocities are updated. The core constraint is that the time step must be small enough to resolve the fastest motions in the system, which are typically bond vibrations involving light atoms, such as carbon-hydrogen (C-H) bonds [10].

The Nyquist-Shannon sampling theorem provides the foundational rule: the time step must be less than half the period of the fastest vibration to avoid aliasing and accurately capture the dynamics [10]. In practice, a more conservative ratio is used, with the time step being about 0.01 to 0.0333 of the smallest vibrational period in the system [10]. For a typical C-H bond stretch with a frequency of approximately 3000 cm⁻¹ (period of ~11 femtoseconds), this translates to a maximum time step of about 2 femtoseconds (fs) for stable integration in the absence of constraints [10].

The choice of integrator is also crucial. Symplectic integrators, such as the velocity Verlet algorithm, are preferred because they preserve the geometric structure of the Hamiltonian flow, ensuring excellent long-term energy conservation and stability [8] [11]. The use of a non-symplectic integrator can lead to significant energy drift and necessitate a much shorter time step [10].

Quantitative Guidelines and Parameter Selection

The optimal time step depends on the specific characteristics of the simulated system and the methodology employed. The following table summarizes key recommendations and their contexts.

Table 1: Guidelines for Time Step Selection in Different Scenarios

| Scenario | Recommended Time Step (∆t) | Key Considerations & Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Standard All-Atom MD (Unconstrained) | 1 - 2 fs | Based on the period of C-H bond vibrations; a conservative choice for general stability [10] [1]. |

| Systems with Hydrogen Mass Repartitioning (HMR) | 3 - 4 fs | HMR increases the mass of hydrogen atoms, slowing the fastest vibrations and allowing a larger ∆t [10]. |

| Machine Learning Integrators (Theoretical) | Up to 100 fs | ML models can learn to predict long-time-step evolution, but may not conserve energy or preserve physical symmetries [11]. |

| Structure-Preserving ML Maps (Theoretical) | Significantly > 2 fs | Aims to combine the long time steps of ML with symplecticity and time-reversibility for physical fidelity [11]. |

| Ab Initio MD (AIMD) | 0.5 fs or less | Required for accuracy in systems with quantum mechanical calculations, especially with light atoms like hydrogen [12]. |

Beyond the time step itself, other parameters and choices impact the simulation's performance and validity.

Table 2: Related Simulation Parameters and Practices

| Parameter / Practice | Description & Impact on Time Step |

|---|---|

| Constraint Algorithms (e.g., SHAKE, LINCS) | These algorithms freeze the fastest bond vibrations (e.g., bonds to hydrogen), allowing a time step of 2 fs to be used safely, which is a common practice in biomolecular simulations [10]. |

| Potential Energy Surface (PES) | The accuracy of the PES, whether from force fields, ab initio calculations, or machine learning potentials, is fundamental. An inaccurate PES will yield incorrect dynamics regardless of the time step choice [13] [14] [12]. |

| Validation: Energy Conservation | In a constant energy (NVE) ensemble, the total energy should be conserved. A significant energy drift indicates the time step is too long or the integrator is unsuitable [10]. |

Experimental Protocols for Time Step Validation

Protocol: Assessing Energy Conservation in the NVE Ensemble

This protocol provides a direct method for testing the stability of a chosen time step.

- System Preparation: Create the system of interest (e.g., a solvated protein, a polymer membrane) and minimize its energy to remove bad contacts.

- Equilibration: Equilibrate the system in the desired ensemble (NPT or NVT) until the temperature and pressure have stabilized.

- Production Simulation: Run a production simulation in the microcanonical (NVE) ensemble for a significant duration (e.g., 100 ps to 1 ns) using the candidate time step (e.g., 1 fs, 2 fs, 2.5 fs).

- Data Analysis: Monitor the total energy of the system over time.

- A stable total energy with small fluctuations around a mean value indicates a good time step and a stable integrator.

- A consistent upward or downward drift in the total energy signifies numerical instability, often due to a time step that is too long [10].

- Acceptance Criterion: A widely used rule of thumb is that the long-term drift in the conserved quantity should be less than 1 meV/atom/ps for results considered suitable for publication [10].

Protocol: Dynamic Training of Machine Learning Potentials

For simulations using machine learning potentials (MLPs), a novel training paradigm can enhance stability and accuracy over long simulations, indirectly affecting usable time steps.

- Data Generation: Run short ab initio MD (AIMD) simulations with a small time step (e.g., 0.5 fs) to generate reference data [12].

- Preprocessing: Instead of treating configurations as independent points, extract subsequences of configurational data, including atomic positions, velocities, and the subsequent

S_max - 1atomic forces from the AIMD trajectory [12]. - Model Training:

- Initial Phase: Train the neural network potential (e.g., an Equivariant Graph Neural Network) to minimize the error in energy and force predictions for single, isolated configurations (subsequence length S=1).

- Dynamic Phase: Incrementally increase the subsequence length (S). For each training point, use the model's predicted forces and the velocity Verlet integrator to propagate the system through S steps. The loss function then penalizes errors between the ML-predicted and AIMD-reference energies and forces across the entire subsequence [12].

- Outcome: This method regularizes the model, penalizing predictions that lead to high errors as the simulation progresses. It produces MLPs that are more robust and accurate for long-lasting MD simulations, which is a prerequisite for potentially exploring larger time steps with ML integrators [12].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the key steps and decision points in the time step selection and validation process.

Diagram 1: Workflow for time step validation via energy conservation analysis.

Advanced Techniques and Future Directions

Researchers are developing advanced methods to break the traditional time step bottleneck.

- Machine-Learning-Driven Integrators: These approaches use ML models to learn a map that predicts the system state after a large time step. While promising for speed, they often fail to conserve energy or preserve physical symmetries like time-reversibility [11].

- Structure-Preserving ML Maps: A more robust approach involves learning a symplectic map defined by a generating function, which is equivalent to learning the mechanical action of the system. This ensures the integrator remains symplectic and time-reversible, leading to excellent energy conservation even with large time steps [11].

- Special-Purpose Hardware: Deploying MD simulations on non-von Neumann architectures, such as highly optimized FPGAs, can mitigate the "memory wall bottleneck," drastically improving computational efficiency regardless of the time step [13].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Tool / Reagent | Function in Time Step Context |

|---|---|

| LAMMPS | A highly flexible and widely used MD simulator with robust parallel computing capabilities, suitable for testing time steps in large-scale systems [8]. |

| GROMACS | A high-performance MD software package, often optimized for biomolecular systems, commonly used with a 2 fs time step and constraint algorithms [8]. |

| SHAKE / LINCS | Constraint algorithms that fix bond lengths involving hydrogen atoms, allowing for a practical and stable 2 fs time step in biomolecular simulations [10]. |

| Velocity Verlet Integrator | A symplectic and time-reversible integration algorithm that provides superior long-term stability and energy conservation, making it the default choice for most MD simulations [8] [10]. |

| Hydrogen Mass Repartitioning (HMR) | A technique that artificially increases the mass of hydrogen atoms and decreases the mass of attached heavy atoms, slowing high-frequency vibrations and permitting a 3-4 fs time step [10]. |

| Machine Learning Potentials (MLPs) | Potentials that offer near-quantum accuracy with classical MD cost. Their stability over long simulations can be enhanced with dynamic training protocols [13] [12]. |

In molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, a statistical ensemble defines the thermodynamic conditions under which a system evolves, specifying which state variables—such as energy (E), temperature (T), pressure (P), or volume (V)—are held constant [15] [16]. The choice of ensemble is a foundational step in setting up a simulation, as it directly controls the sampling of phase space and determines which thermodynamic properties and fluctuations can be accurately measured [17] [15]. Within the context of atomic tracking research, which aims to understand the trajectories and behaviors of individual atoms within a larger system, selecting the appropriate ensemble is crucial for mimicking the correct experimental conditions and for obtaining physically meaningful dynamic information [7] [18]. This article provides application notes and detailed protocols for implementing the most common ensembles (NVE, NVT, NPT) in MD studies, with a specific focus on scenarios relevant to tracking atomic evolution.

Ensemble Theory and Selection Criteria

The following table summarizes the key characteristics, physical interpretations, and primary applications of the three major ensembles discussed in this protocol.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Primary Molecular Dynamics Ensembles

| Ensemble | Conserved Quantities | Physical Interpretation | Common Applications in Tracking Scenarios |

|---|---|---|---|

| NVE (Microcanonical) | Number of particles (N), Volume (V), Energy (E) | Isolated system that cannot exchange energy or matter with its surroundings [15] [16]. | Studying intrinsic dynamics and energy flow [18]; simulating gas-phase reactions or isolated clusters [17]; calculating internal energy [17]. |

| NVT (Canonical) | Number of particles (N), Volume (V), Temperature (T) | Closed system in thermal contact with a heat bath (thermostat) at a constant temperature [15] [16]. | Simulating systems in explicit solvent where volume is fixed [15]; studying conformational dynamics of biomolecules [19]; calculating Helmholtz free energy [17]. |

| NPT (Isothermal-Isobaric) | Number of particles (N), Pressure (P), Temperature (T) | Closed system in contact with a thermostat and a barostat, allowing volume to fluctuate to maintain constant pressure [15] [16]. | Mimicking standard laboratory conditions for condensed phases [17] [16]; studying pressure-induced structural changes [6]; calculating Gibbs free energy [17]. |

Guidelines for Ensemble Selection

Choosing the correct ensemble depends on the scientific question and the experimental conditions one aims to replicate.

- Comparing with Experiment: The NPT ensemble is most often the appropriate choice for simulating condensed phases (liquids, solids) as it replicates standard laboratory conditions of constant temperature and pressure [17] [16]. For processes in a fixed container, such as a protein in a crystal lattice, the NVT ensemble may be more suitable [20] [15].

- Property of Interest: The ensemble determines the free energy that is naturally sampled: NVE for internal energy, NVT for Helmholtz free energy, and NPT for Gibbs free energy [17].

- Equivalence and Limitations: In the thermodynamic limit (infinite system size), ensembles are equivalent and yield the same average properties away from phase transitions [17]. However, for the finite systems typical of MD simulations, the choice of ensemble matters and can yield different results, especially for fluctuation properties [17] [15]. For example, an NVE simulation with total energy just below a reaction barrier will never cross it, whereas an NVT simulation at the same average energy can surmount the barrier due to thermal fluctuations [17].

Standard Protocols for Ensemble Implementation

A typical MD simulation protocol involves multiple stages, often employing different ensembles for equilibration and production. The following workflow diagram illustrates a standard multi-stage approach for simulating a biomolecular system in explicit solvent, though the principles apply to materials systems as well.

Diagram 1: A standard MD simulation workflow showing the sequence of ensembles often used for equilibration before a production run.

Protocol 1: NVE Production Run

Objective: To simulate system dynamics with conserved total energy, suitable for studying intrinsic energy flow or comparing with experimental data collected under isolated conditions [17] [18].

Workflow Integration: An NVE production run is typically performed after a system has been thoroughly equilibrated to the desired temperature and pressure using NVT and NPT ensembles [16].

Steps:

- Initialization: Use coordinates and velocities from a pre-equilibrated NPT or NVT simulation.

- Integrator: Use a velocity Verlet or leap-frog algorithm, which are symplectic integrators that exhibit excellent long-term energy conservation [6] [7].

- Parameters:

- Set the

integratortomd(or equivalent). - Disable the thermostat and barostat.

- A typical time step is 0.5–1.0 femtoseconds (fs), constrained by the need to accurately capture the fastest bond vibrations [6].

- Set the

- Analysis: The total energy should be stable with only small fluctuations. Monitor the root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) to ensure the system is not undergoing a large conformational drift, which can indicate inadequate equilibration [20].

Protocol 2: NVT Production Run

Objective: To simulate a system at constant temperature, useful for studying conformational dynamics in a fixed volume, such as a protein in a crystal lattice [20] [15].

Workflow Integration: This can serve as a standalone production ensemble or as the first equilibration step to adjust the system's temperature [16].

Steps:

- Initialization: Start from an energy-minimized structure.

- Thermostat: Choose a thermostat. The Nosé-Hoover thermostat provides a robust canonical ensemble, though velocity-rescaling methods are also common [7].

- Parameters:

- Set the

integratortomd(or equivalent). - Define the

tcoupl(or equivalent) parameter to specify the thermostat and the target temperature. - The

gen_velparameter can be set toyesto generate initial velocities from a Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution at the target temperature [6].

- Set the

- Analysis: Monitor temperature and potential energy for stability. For atomic tracking, properties like the radial distribution function (RDF) and mean square displacement (MSD) can be calculated to analyze structure and atomic mobility [6] [7].

Protocol 3: NPT Production Run

Objective: To simulate a system at constant temperature and pressure, mimicking most laboratory conditions for materials and biomolecules in solution [17] [16].

Workflow Integration: This is the most common ensemble for the production run of condensed-phase systems after initial NVT equilibration [16].

Steps:

- Initialization: Use coordinates and velocities from an NVT-equilibrated simulation.

- Thermostat and Barostat: Combine a thermostat (e.g., Nosé-Hoover) with a barostat (e.g., Parrinello-Rahman) [15].

- Parameters:

- Set the

integratortomd(or equivalent). - Define parameters for both the thermostat (

tcoupl) and the barostat (pcoupl). - Specify the target pressure (typically 1 bar for aqueous systems).

- Set the

- Analysis: Monitor temperature, pressure, and density for stability. The system volume will fluctuate. The MSD calculated from an NPT simulation provides a direct measure of the diffusion coefficient, which is critical for tracking atomic and molecular mobility [6].

Table 2: Essential Software and Force Fields for MD Simulations

| Resource | Type | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| LAMMPS [7] | MD Software | A highly versatile and widely used open-source code for simulating materials, atoms, and soft matter. |

| GROMACS [16] | MD Software | A high-performance package optimized for biomolecular systems like proteins and lipids. |

| VMD [7] | Analysis & Visualization | A tool for preparing, visualizing, and analyzing the 3D trajectories generated by MD simulations. |

| EAM Potential [7] | Force Field | An Embedded Atom Method potential used for simulating metallic systems, such as bimetallic nanoparticles. |

| ReaxFF [18] | Force Field | A reactive force field capable of simulating bond breaking and formation, essential for tracking chemical reactions. |

| CHARMM/AMBER [19] [21] | Force Field | Families of highly refined biomolecular force fields for accurate simulation of proteins and nucleic acids. |

Advanced Application: Ensembles in Atomic Tracking Research

The choice of ensemble directly impacts the interpretation of atomic motion in tracking studies. For example, in research on the coalescence of Au and Ni nanoparticles, the NVT ensemble was used to study structural evolution during a controlled heating process [7]. This allowed researchers to track how Au atoms segregated to the surface of Ni particles and observe the formation of various structures like Janus and core-shell nanoparticles, with the constant volume condition helping to isolate the effect of temperature on atomic rearrangement.

In another advanced application, ensemble-restrained MD (erMD) is used to address force field inaccuracies that can cause simulated structures to drift from their correct coordinates over time [20]. This technique is particularly valuable for atomic tracking as it ensures the average simulated structure remains consistent with experimental data (e.g., from X-ray crystallography) while still allowing individual atoms to exhibit realistic dynamic fluctuations. The protocol involves adding a harmonic restraint potential that acts on the ensemble-average structure, gently guiding it toward the experimental reference without stifling the motion of individual atoms. This approach has been validated against solid-state NMR data and produces highly realistic trajectories for atomic tracking [20].

Selecting the appropriate statistical ensemble is a critical decision that aligns an MD simulation with the physical reality one seeks to model. For atomic tracking research, the NVT ensemble is often the tool of choice for processes in a confined volume, while the NPT ensemble best replicates standard laboratory conditions for solutions and materials. A robust simulation protocol involves a multi-stage equilibration process, progressively relaxing the system through NVT and NPT steps before beginning a production run in the chosen target ensemble. By applying these guidelines and protocols, researchers can ensure their simulations provide a physically accurate foundation for investigating and interpreting the dynamic pathways of atoms.

Within the broader context of establishing robust molecular dynamics (MD) simulation parameters for atomic tracking research, the initial configuration of a system is a critical determinant of success. Proper initialization directly influences the simulation's stability, the rate of convergence to equilibrium, and the physical validity of the sampled trajectory. For researchers and drug development professionals, a flawed initial state can lead to erroneous conclusions regarding molecular behavior, binding events, or dynamic processes. This protocol focuses on one of the most fundamental aspects of initialization: assigning atomic velocities from a Maxwell-Boltzmann (MB) distribution. This method ensures that the system begins with a kinetic energy distribution corresponding to the desired temperature, providing a physically realistic starting point for subsequent dynamics in the canonical (NVT) or microcanonical (NVE) ensembles [21].

The Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution describes the probability distribution of speeds for particles in a classical, non-interacting gas at thermodynamic equilibrium [22]. In the context of MD, it is used to assign velocities to particles such that the instantaneous temperature of the system matches the target temperature. The functional form of the probability distribution for a single component of the velocity vector (e.g., (v_x)) is a Gaussian (normal) distribution, while the distribution of speeds (the magnitude of the velocity) is the chi distribution with three degrees of freedom [22]. The success of this approach relies on the ergodic hypothesis, which implies that the velocity distribution of a single particle, averaged over a sufficiently long time, is identical to the distribution across all particles in the system at a single instant in time [23].

Theoretical Foundation

The Maxwell-Boltzmann Distribution

The Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution for particle velocities in three dimensions is derived from statistical mechanics principles. For a system of non-interacting particles of mass (m) at thermodynamic equilibrium temperature (T), the probability density function for a velocity vector (\mathbf{v} = (vx, vy, v_z)) is given by [22]:

[ f(\mathbf{v}) d^{3}\mathbf{v} = \left[\frac{m}{2\pi k{\text{B}}T}\right]^{3/2} \exp\left(-\frac{mv^{2}}{2k{\text{B}}T}\right) d^{3}\mathbf{v} ]

Here, (k{\text{B}}) is the Boltzmann constant, and (v^{2} = vx^{2} + vy^{2} + vz^{2}). This implies that each Cartesian component of the velocity is independently and normally distributed with a mean of zero and a variance of (\sigma^{2} = k_{\text{B}}T / m):

[ f(vi) dvi = \sqrt{\frac{m}{2\pi k{\text{B}}T}} \exp\left(-\frac{m vi^{2}}{2k{\text{B}}T}\right) dvi, \quad \text{where } i = x, y, z ]

The distribution of the speed (v = |\mathbf{v}|) is consequently the Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution [22]:

[ f(v) dv = \left[\frac{m}{2\pi k{\text{B}}T}\right]^{3/2} 4\pi v^{2} \exp\left(-\frac{mv^{2}}{2k{\text{B}}T}\right) dv ]

Table 1: Key Parameters of the Maxwell-Boltzmann Distribution

| Parameter | Symbol | Formula | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Distribution Parameter | (a) | (a = \sqrt{k_{\text{B}}T / m}) | Scale parameter for the speed distribution. |

| Mean Speed | (\langle v \rangle) | (2a \sqrt{2 / \pi}) | The arithmetic mean of the particle speeds. |

| Root-Mean-Square Speed | (v_{\text{rms}}) | (\sqrt{\langle v^2 \rangle} = \sqrt{3}a) | Proportional to the square root of temperature. |

| Most Probable Speed | (v_{\text{p}}) | (\sqrt{2} a) | The speed at which the probability density is maximum. |

Relevance to Molecular Dynamics Simulation

In MD simulations, the system's temperature is a measure of the average kinetic energy of the particles. For a system with (N) atoms, the instantaneous temperature (T_{\text{inst}}) is calculated from the velocities as [21]:

[ T{\text{inst}} = \frac{1}{3N k{\text{B}}} \sum{i=1}^{N} mi \mathbf{v}_i^{2} ]

Initializing velocities from an MB distribution ensures that the expected value of the instantaneous temperature is the desired temperature (T). However, for any finite system, there will be fluctuations around this expected value. Therefore, the initial velocities (\mathbf{v}_i) for each atom (i) are typically drawn as random vectors from the 3D Gaussian distribution specified above. It is crucial to note that this distribution applies fundamentally to the velocities of particles in an ideal gas at equilibrium [22]. For condensed-phase systems with significant interatomic interactions, the velocity distribution will relax to the MB form as the system evolves toward equilibrium, provided the initial state is not too far from equilibrium [23].

Experimental Protocol

This section provides a detailed, step-by-step protocol for initializing atomic positions and velocities in a molecular dynamics simulation.

Pre-initialization Checks

- System Topology: Confirm that the system topology (number of atoms, bonds, angles, etc.) is fully defined and that all force field parameters are assigned.

- Target Temperature: Define the target temperature (T) for the simulation. Be aware of the units used by your MD software (Kelvin or electron volt,

temperature_Kortemperature) [24]. - Atomic Masses: Ensure atomic masses (m_i) are correctly assigned for all particles, as they are required for the velocity calculation.

Initializing Atomic Positions

Before assigning velocities, atoms must be placed in initial positions. For atomic tracking research, the choice of initial configuration depends on the system being modeled.

- Crystalline Solids: Place atoms on a perfect crystal lattice (e.g., FCC, BCC) corresponding to the material being studied.

- Solvated Systems (Proteins, Ligands):

- Place the solute molecule (e.g., a protein) in the center of a simulation box.

- Solvate the system by filling the remaining box volume with solvent molecules (e.g., water, ions) using pre-equilibrated solvent boxes or packing algorithms.

- Liquids and Amorphous Systems: Begin with atoms placed on a lattice (which will be melted during equilibration) or use pre-equilibrated configurations from a similar system.

Initial structures are commonly defined in file formats such as XYZ or PDB [25]. Most MD software can read these files to import the initial atomic positions and, in some cases, the simulation cell parameters.

Protocol: Assigning Velocities from a Maxwell-Boltzmann Distribution

The following steps are executed by the MD engine during the setup phase, often triggered by a command in the input script (e.g., velocity all create ${T} 4928459 in LAMMPS, where the number is a random seed).

Calculate Velocity Standard Deviation: For each atom of mass (mi), compute the standard deviation (\sigmai) for each Cartesian velocity component: [ \sigmai = \sqrt{\frac{k{\text{B}}T}{mi}} ] The units of (\sigmai) are length/time (e.g., Å/ps).

Generate Random Velocities: For each atom (i) and for each of its three velocity components ((vx, vy, vz)), draw a random number from a Gaussian (normal) distribution with a mean of zero and a standard deviation of (\sigmai).

- Implementation Note: This requires a reliable pseudo-random number generator. The seed for this generator should be set to a different value for each simulation to ensure statistical independence of trajectories.

Adjust System Momentum (Optional but Recommended): After generating velocities for all atoms, calculate the total momentum of the system (\mathbf{P} = \sumi mi \mathbf{v}_i).

- If the system is intended to be stationary (no net flow), subtract the center-of-mass velocity from every atom's velocity: [ \mathbf{v}i^{\text{(new)}} = \mathbf{v}i - \frac{\mathbf{P}}{\sumi mi} ]

- This correction ensures the system has no overall translation, which is typically desired for a system in a stationary container.

Scale to Exact Temperature (Optional): The previous steps only ensure the expected temperature is (T). The actual instantaneous temperature (T{\text{inst}}) will likely be slightly different due to random fluctuations, especially in small systems. If an exact initial temperature is required, the velocities can be scaled: [ \mathbf{v}i^{\text{(scaled)}} = \mathbf{v}i \times \sqrt{\frac{T}{T{\text{inst}}}} ]

- Caution: This scaling procedure alters the statistical properties of the MB distribution and should be used with caution, primarily for the initial step. The system will quickly re-establish the correct fluctuations during equilibration.

The diagram below illustrates the logical workflow for the entire initialization process, culminating in the velocity assignment protocol.

Post-Initialization Equilibration

Velocities assigned from an MB distribution alone do not guarantee an equilibrated system. The initial configuration, especially if positions are artificially constructed (e.g., a crystal lattice for a liquid), may have high potential energy. A brief equilibration procedure is therefore critical [21]:

- Energy Minimization: Perform an energy minimization on the initial structure (with assigned velocities) to relieve any high-energy clashes or distortions.

- Short NVT Simulation: Run a short MD simulation in the NVT ensemble (constant Number of particles, Volume, and Temperature) using a thermostat (e.g., Nosé-Hoover, Langevin [24]). This allows the system to relax structurally while maintaining the target temperature.

- Validation: Monitor the potential and kinetic energy, temperature, and pressure (if applicable) to confirm that these properties fluctuate around stable average values, indicating that equilibrium has been reached.

The Scientist's Toolkit

This section details essential software and computational reagents required to implement the protocols described above.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for MD Initialization

| Tool / Reagent | Type | Primary Function | Relevance to Initialization |

|---|---|---|---|

| LAMMPS [26] | MD Software Package | A highly flexible, open-source molecular dynamics simulator. | Provides commands (velocity create) to initialize velocities from an MB distribution and tools for subsequent equilibration. |

| ASE (Atomic Simulation Environment) [24] | Python Package & MD Library | A set of tools and Python modules for setting up, manipulating, running, visualizing, and analyzing atomistic simulations. | Contains MD classes (e.g., VelocityVerlet) that can be used to run simulations after initializing velocities. |

| i-PI [25] | MD Server / Interface | A Python interface for advanced path integral MD simulations that can interact with multiple MD client codes. | Manages simulation setup and initialization, including reading initial configurations from XYZ or PDB files. |

| Scymol [27] | Python-based GUI for LAMMPS | A user-friendly interface designed to facilitate the setup and execution of LAMMPS simulations. | Simplifies the process of defining simulation parameters, including initial temperature and velocity generation. |

| Maxwell-Boltzmann Distribution | Physical Model / Algorithm | The probability distribution for particle speeds in an ideal gas at equilibrium. | The core mathematical model used by MD engines to generate physically realistic initial velocities corresponding to a target temperature. |

| Pseudo-Random Number Generator (PRNG) | Computational Algorithm | Generates a sequence of numbers that approximates the properties of random numbers. | Critical for drawing the Gaussian-distributed random numbers used to assign velocity components. The seed value ensures reproducibility. |

Data Presentation and Validation

A critical step after initialization is to verify that the assigned velocities correctly follow the Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution and produce the correct initial temperature.

Quantitative Validation Metrics

The following table lists key properties to check after the velocity initialization step.

Table 3: Key Metrics for Validating Initialized Velocities

| Metric | Calculation Method | Expected Outcome for Validation |

|---|---|---|

| Instantaneous Temperature | ( T{\text{inst}} = \frac{1}{3N k{\text{B}}} \sum{i=1}^{N} mi \mathbf{v}_i^{2} ) | Should be close to the target temperature (T) (allowing for small statistical fluctuations). |

| Total System Momentum | ( \mathbf{P} = \sumi mi \mathbf{v}_i ) | Should be zero (or very close to zero if momentum correction was applied). |

| Distribution of Velocity Components | Histogram of, e.g., all (v_x) values. | Should fit a Gaussian curve with mean zero and variance (k_B T / \langle m \rangle). |

| Distribution of Particle Speeds | Histogram of speeds (v = |\mathbf{v}|) for all particles. | Should fit the Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution (f(v) = 4\pi v^2 (m/2\pi kB T)^{3/2} \exp(-mv^2/(2kB T))). |

Example Validation Workflow

- Run a Zero-Step Simulation: Use your MD software to initialize the system and write the velocities to a file without propagating the simulation.

- Analyze the Output: Parse the output file to extract the initial velocities for all atoms.

- Plot and Fit: Create histograms for one component of the velocity (e.g., (v_x)) and for the atomic speeds. Fit the appropriate distributions to the data, as shown in the research question from Stack Exchange [23]. A successful initialization will show an excellent fit between the simulated data and the theoretical curves.

- Calculate Metrics: Compute the instantaneous temperature and total momentum from the velocities to confirm they meet the expected values.

Understanding the Impact of Force Fields and Potentials on Atomic Trajectories

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations have become an indispensable tool in modern scientific research, particularly in fields like drug discovery and structural biology. These simulations allow researchers to observe the time-dependent evolution of molecular systems, providing insights into dynamic processes that are often inaccessible through experimental methods alone [28] [29]. At the heart of every MD simulation lies the force field—a computational model that defines the potential energy of a system based on the positions of its atoms [30]. The choice of force field profoundly influences the simulated atomic trajectories, which in turn determines the reliability and interpretability of the simulation results. Force fields are essentially sets of empirical energy functions and parameters carefully parameterized to calculate potential energy as a function of molecular coordinates [31]. They enable the calculation of forces acting on each atom, which are then used to propagate the system through time according to Newton's laws of motion [28]. As MD simulations continue to address increasingly complex biological questions, from protein-ligand interactions to entire viral envelopes, understanding how force field selection impacts atomic trajectories becomes paramount for generating physiologically relevant results [28] [29].

Mathematical Foundations of Force Fields

Functional Form and Energy Terms

The total potential energy in a typical biomolecular force field is composed of both bonded and non-bonded interaction terms, with the general expression:

[ E{\text{total}} = E{\text{bonded}} + E_{\text{non-bonded}} ]

where ( E{\text{bonded}} = E{\text{bond}} + E{\text{angle}} + E{\text{dihedral}} + E{\text{improper}} ) and ( E{\text{non-bonded}} = E{\text{electrostatic}} + E{\text{van der Waals}} ) [30]. This additive approach allows for computational efficiency while capturing the essential physics of molecular interactions.

Table 1: Core Components of Biomolecular Force Fields

| Energy Term | Mathematical Formulation | Physical Description | Key Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bond Stretching | $V{\text{Bond}} = kb(r{ij}-r0)^2$ [31] | Oscillation about equilibrium bond length | Force constant (kb), equilibrium distance (r0) |

| Angle Bending | $V{\text{Angle}} = kθ(θ{ijk}-θ0)^2$ [31] | Oscillation about equilibrium angle | Force constant (kθ), equilibrium angle (θ0) |

| Torsional Dihedral | $V{\text{Dihed}} = kφ(1+cos(nϕ-δ))$ [31] | Rotation around central bond | Force constant (k_φ), periodicity (n), phase (δ) |

| Improper Dihedral | $V{\text{Improper}} = kφ(ϕ-ϕ_0)^2$ [31] | Enforcement of planarity | Force constant (kφ), equilibrium angle (ϕ0) |

| van der Waals | $V_{LJ}(r)=4ε\left[\left(\frac{σ}{r}\right)^{12}-\left(\frac{σ}{r}\right)^{6}\right]$ [31] | Pauli repulsion & dispersion forces | Well depth (ε), van der Waals radius (σ) |

| Electrostatic | $V{\text{Elec}}=\frac{q{i}q{j}}{4πϵ{0}ϵ{r}r{ij}}$ [31] | Coulombic interactions between charges | Atomic partial charges (qi, qj), dielectric constant (ϵ_r) |

Force Field Classifications

Biomolecular force fields are commonly categorized into three classes based on their complexity and treatment of molecular interactions:

Class 1 force fields (e.g., AMBER, CHARMM, GROMOS, OPLS) describe bond stretching and angle bending with simple harmonic motion and omit correlations between these degrees of freedom [31]. These remain the most widely used force fields for biomolecular simulations due to their computational efficiency and extensive parameterization.

Class 2 force fields (e.g., MMFF94, UFF) introduce anharmonicity through cubic and/or quartic terms to the potential energy for bonds and angles, and include cross-terms describing coupling between adjacent internal coordinates [31]. This provides more accurate description of molecular vibrations at the cost of increased complexity.

Class 3 force fields (e.g., AMOEBA, DRUDE) explicitly incorporate electronic polarization effects through various methods, including inducible point dipoles (AMOEBA) or Drude oscillators (CHARMM-Drude) [31]. These force fields offer improved accuracy for simulating heterogeneous environments where polarization effects are significant, such as membrane proteins or protein-ligand complexes.

The accuracy of a force field depends critically on the parameterization of its energy terms. Force field parameters are derived through a combination of theoretical calculations and experimental data, creating a semi-empirical approach that balances physical rigor with computational practicality [30].

Parameterization Methodologies

Parameterization strategies can be broadly categorized into two approaches: component-specific parametrization, developed for describing a single substance, and transferable parametrization, where parameters are designed as building blocks applicable to different substances [30]. For biomolecular force fields, the transferable approach is essential given the vast chemical space of biological molecules. The parametrization process typically utilizes multiple data sources:

- Quantum mechanical calculations provide information on conformational energies, electrostatic potentials, and vibrational frequencies for small molecule fragments [30].

- Experimental data including enthalpy of vaporization, enthalpy of sublimation, liquid densities, and various spectroscopic properties serve to validate and refine parameters [30].

- Crystallographic data from sources like the Protein Data Bank inform equilibrium values for bonds, angles, and dihedrals [28].

A critical aspect of parameterization involves defining atom types—classifications not only for different elements but also for the same elements in different chemical environments [30]. For example, oxygen atoms in water and oxygen atoms in carbonyl groups are treated as distinct atom types with different parameters. This differentiation allows the force field to capture the varying chemical behavior of atoms in different molecular contexts.

Impact on Atomic Trajectories and System Properties

Direct Influence on Sampling and Dynamics

The choice of force field directly governs the atomic trajectories generated in MD simulations through its definition of the system's potential energy surface. Several key aspects of the simulated dynamics are particularly sensitive to force field selection:

- Conformational sampling: The energy barriers between different molecular conformations are determined by the torsional dihedral parameters, which directly control the transitions between rotational states [29]. Inaccurate dihedral parameters can lead to either insufficient sampling or populations of unrealistic conformations.

- Solvent structure: The radial distribution function (RDF), which describes how particle density varies as a function of distance from a reference particle, is highly sensitive to the non-bonded parameters [32]. The RDF between water oxygen atoms, for instance, serves as a key validation metric for water models.

- Binding pocket dynamics: In drug discovery applications, the conformational diversity of ligand binding pockets—including the opening and closing of transient druggable subpockets—is strongly influenced by the force field's balance of intramolecular and intermolecular interactions [29].

Table 2: Force Field Selection Guide for Specific Applications

| Research Objective | Recommended Force Field Type | Key Considerations | Validation Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Folding | Class 2 with improved dihedrals | Accurate secondary structure balance | RMSD to native, Q-value |

| Membrane Proteins | Lipid-specific parameters (e.g., SLIPIDS) | Balanced protein-lipid interactions | Membrane thickness, area per lipid |

| Protein-Ligand Binding | Class 3 polarizable force fields | Handling of heterogeneous environments | Binding free energies, hydration |

| Carbohydrates | Specialized glycoprotein force fields | Proper ring puckering and linkage | J-couplings, crystal packing |

| Nucleic Acids | DNA/RNA optimized (e.g., parmBSC1) | Accurate backbone and sugar pucker | Helicoidal parameters, persistence length |

| Long Timescales | Class 1 (efficiency prioritized) | Balance between accuracy and speed | MSD, conformational diversity |

Advanced Effects on Thermodynamic and Kinetic Properties

Beyond immediate structural properties, force fields significantly impact calculated thermodynamic and kinetic properties:

- Binding free energies: The calculation of standard Gibbs free energy of binding (∆bG⊖) using methods like free energy perturbation is highly dependent on the non-bonded parameters, particularly partial charges and Lennard-Jones parameters [28]. Small inaccuracies can lead to significant errors in predicted binding affinities.

- Diffusion coefficients: The dynamics of solvents and solutes, quantified through mean square displacement calculations, are influenced by the friction and energy landscape defined by the force field [32].

- Ionic conductivity: In simulations of electrolyte solutions, the calculated ionic conductivity depends on the accurate representation of ion-ion and ion-solvent interactions [32].

Protocol for Force Field Selection and Validation

Systematic Selection Methodology

Choosing an appropriate force field requires careful consideration of the specific research context. The following protocol provides a systematic approach to force field selection and validation:

Step 1: Define System Requirements

- Identify the key molecular components (proteins, nucleic acids, lipids, small molecules, etc.)

- Determine the relevant timescales for processes of interest

- Assess available computational resources

Step 2: Initial Force Field Screening

- Select force fields with parameters for all system components

- Prioritize force fields validated for similar systems in literature

- Consider compatibility between different parameter sets when mixing

Step 3: Parameterization of Missing Components

- For novel molecules, derive parameters using consistent methodology

- Transfer parameters from similar chemical moieties when possible

- Validate partial charge assignments using quantum mechanical calculations

Step 4: Equilibration and Validation

- Perform sufficient equilibration to relax the system

- Compare simulated properties with available experimental data

- Validate structural, dynamic, and thermodynamic properties

Advanced Parameterization for Novel Molecules

When force field parameters are unavailable for specific molecules, the following parameterization protocol is recommended:

Geometry optimization: Perform quantum mechanical geometry optimization at an appropriate level of theory (e.g., B3LYP/6-31G*) to obtain equilibrium bond lengths and angles.

Partial charge derivation: Calculate electrostatic potential charges using methods such as RESP or CHelpG, ensuring consistency with the chosen force field's charge derivation methodology.

Dihedral parameterization: Conduct rotational scans around flexible dihedrals using quantum mechanics and fit the torsional barriers to match the quantum mechanical energy profile.

Validation in known systems: Test the new parameters in model compounds with known experimental properties (e.g., density, enthalpy of vaporization) before application to the target system.

Trajectory Analysis Methods for Force Field Validation

Essential Analysis Techniques

Validating force field performance requires comprehensive analysis of the resulting trajectories. Several essential techniques provide insights into different aspects of force field accuracy:

- Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD): Measures structural stability and convergence by quantifying deviations from a reference structure [33].

- Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF): Identifies regions of flexibility and stability within a protein, useful for detecting over- or under-stabilized regions [33].

- Radius of Gyration (Rgyr): Assesss the overall compactness of protein structures, sensitive to force field balance between bonded and non-bonded interactions [33].

- Radial Distribution Function (RDF): Characterizes the structure of solvents and solvation shells around solutes, providing sensitive validation of non-bonded interactions [32].

Advanced Analysis Methods

Recent advancements in trajectory analysis have introduced more sophisticated methods for evaluating force field performance:

- Trajectory maps: A novel visualization method that represents protein backbone movements as a heatmap, showing the location, time, and magnitude of conformational changes [33]. This method allows direct comparison of multiple simulations and identification of specific regions and timeframes of instability.

- Principal Component Analysis (PCA): Identifies the essential collective motions in a trajectory, useful for comparing the dominant dynamics between different force fields.

- Clustering analysis: Groups similar conformations from the trajectory to assess the diversity of sampled states and identify potentially missing conformations.

The analysis of trajectories from MD simulations typically involves specialized software tools. For example, the analysis program in the AMS package can compute radial distribution functions, mean square displacement, and autocorrelation functions from trajectory data [32]. Similarly, tools like GROMACS' trjconv and AMBER's align commands are used for trajectory processing before analysis [33].

Table 3: Essential Resources for Force Field Implementation and Validation

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Software | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Simulation Engines | GROMACS [28], AMBER [28], NAMD [28], CHARMM [28] | Core MD simulation execution | All-atom MD simulations with various force fields |

| Force Field Databases | MolMod [30], TraPPE [30], openKim [30] | Parameter repositories | Access to validated parameters for diverse molecules |

| Parameterization Tools | ANTECHAMBER, CGenFF, MATCH | Automated parameter generation | Deriving parameters for novel molecules |

| Trajectory Analysis | MDTraj [33], TrajMap.py [33], VMD [33] | Trajectory processing and visualization | Calculating properties, creating trajectory maps |

| Quantum Chemical Software | Gaussian, ORCA, PSI4 | Reference calculations | Parameter derivation and validation |

| Validation Databases | Protein Data Bank [28], Nucleic Acid Database | Experimental reference structures | Validation of simulated structures and dynamics |

Emerging Trends and Future Directions

The development of force fields remains an active area of research, with several promising directions emerging:

- Machine learning force fields: Approaches such as ANI-2x are trained on millions of quantum mechanical calculations and can learn arbitrary potential energy surfaces without analytical constraints [29]. While currently slower than classical force fields, they offer the potential for quantum-level accuracy at significantly reduced computational cost.

- Enhanced polarizable force fields: Continued refinement of polarizable models like AMOEBA and CHARMM-Drude aims to improve the description of heterogeneous electrostatic environments without excessive computational overhead [31].

- Automated parameterization: Efforts to develop more automated parameterization workflows seek to reduce subjectivity and improve reproducibility in force field development [30].

- Specialized force fields for drug discovery: Increasing focus on improving parameters for pharmaceutically relevant compounds, including better treatment of halogen bonding, tautomerization, and protonation states [28] [29].

As these advancements mature, they will enable more accurate simulations of complex biological processes, further strengthening the role of molecular dynamics in drug discovery and structural biology. The ongoing improvements in computer hardware, including specialized processors like Anton and GPU acceleration, will make these more sophisticated force fields increasingly accessible for routine research applications [29].

Step-by-Step Setup: Configuring Parameters for Specific Tracking Goals

The initial construction of a molecular dynamics (MD) system, encompassing solvation, ion placement, and energy minimization, establishes the foundational stability for all subsequent simulation data. This protocol details a standardized, ten-step procedure for preparing explicitly solvated biomolecular systems, integrating criteria for assessing stabilization. Designed for atomic tracking research, this guide provides researchers with explicit methodologies to generate reliable, production-ready simulation systems, thereby enhancing reproducibility in computational drug development.

In molecular dynamics simulations, the production phase—which yields data for analysis—is critically dependent on the careful preparatory steps of system building and equilibration. An improperly constructed system, with issues such as unrealistic atomic clashes or incorrect system density, can lead to simulation instability and non-physical results [34]. This Application Note provides a detailed, actionable protocol for the solvation, ion placement, and energy minimization of biomolecules, with a focus on generating stable initial configurations for atomic-level tracking. The procedures outlined are designed to be generalizable across a wide range of system types, including proteins, nucleic acids, and protein-membrane complexes [34].

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Computational Materials

The following table catalogues the key software and data components required for building a molecular dynamics system.

Table 1: Essential Materials and Software for System Setup

| Item | Function/Description | Example/Format |

|---|---|---|

| Protein Structure Coordinates | The initial atomic coordinates of the biomolecule, serving as the starting point for simulation. | PDB file format from RCSB [35]. |

| Molecular Dynamics Software Suite | Software for performing energy minimization, molecular dynamics, and trajectory analysis. | GROMACS, AMBER, NAMD, CHARMM [34] [35]. |

| Force Field | A set of empirical parameters that describe the potential energy of the system and govern interatomic interactions. | ffG53A7 in GROMACS; parameters vary by software [35]. |

| Molecular Topology File | Describes the molecular system, including atoms, bonds, angles, dihedrals, and non-bonded parameters. | .top file in GROMACS [35]. |

| Molecular Geometry File | Contains the coordinates and velocities of all atoms in the system. | .gro file in GROMACS [35]. |

| Simulation Parameter File | Defines all settings and algorithms for the simulation steps (minimization, equilibration, production). | .mdp file in GROMACS [35]. |

| Pre-equilibrated Solvent Box | A pre-built, stable box of solvent molecules (e.g., water) used to solvate the biomolecule. | -- |

Core Methodologies and Quantitative Data

Establishing the Solvated Simulation Environment

The initial steps involve placing the biomolecule into a defined periodic box and surrounding it with solvent to mimic a physiological environment.

- Periodic Boundary Conditions (PBC): A box (e.g., cubic, dodecahedron) is defined around the protein to eliminate edge effects and simulate a continuous environment [35]. The protein is centered with a recommended minimum distance of 1.0–1.4 nm from the box edge to prevent interactions with its own periodic images [35].

- Solvation: The

solvatecommand fills the box with water molecules. The topology file is automatically updated to include the added solvent molecules [35].

Table 2: Common Box Types and Their Characteristics

| Box Type | Description | Relative Efficiency |

|---|---|---|

| Cubic | A cube with all sides equal. | Lower; requires more solvent atoms for a given protein size. |

| Rhombic Dodecahedron | A space-filling polyhedron with 12 identical faces. | Higher; can reduce the number of solvent atoms by ~30% compared to a cubic box, lowering computational cost [35]. |

Ion Placement and System Neutralization

The addition of ions serves two primary purposes: neutralizing the net charge of the system and mimicking a specific physiological ion concentration (e.g., 150 mM NaCl).

- Neutralization: The net charge on the biomolecule must first be neutralized by adding counter-ions (e.g., Na⁺ for a negatively charged protein, Cl⁻ for a positively charged one) [35].

- Physiological Concentration: After neutralization, additional salt pairs can be added to achieve the desired ionic strength. This step is crucial for modeling electrostatic screening and ion-specific effects.

The ion placement is typically performed using the genion command, which replaces water molecules in the box with ions. This requires a pre-processed input file (.tpr) generated by the grompp command [35]. For example, to add three chloride ions to neutralize a system, the command would be: genion -s protein_b4em.tpr -o protein_genion.gro -nn 3 -nq -1 [35].

Energy Minimization and System Relaxation Protocol

Energy minimization relieves steric clashes and unfavorable geometric distortions introduced during the modeling and solvation process. The following ten-step protocol provides a graduated relaxation of the system [34].

Table 3: Ten-Step System Minimization and Relaxation Protocol

| Step | Description | Key Parameters | Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Initial minimization of mobile molecules (solvent/ions). | 1,000 steps Steepest Descent (SD); Positional restraints on large molecule heavy atoms (5.0 kcal/mol/Ų); No SHAKE. | Relaxes solvent and ions around the fixed solute. |

| 2 | Initial relaxation of mobile molecules. | 15 ps NVT MD (1 fs timestep); Positional restraints on large molecule heavy atoms (5.0 kcal/mol/Ų); SHAKE applied. | Allows solvent to further adapt and distributes kinetic energy. |

| 3 | Initial minimization of large molecules. | 1,000 steps SD; Medium positional restraints on large molecule heavy atoms (2.0 kcal/mol/Ų); No SHAKE. | Begins relaxing the solute while preventing large movements. |

| 4 | Continued minimization of large molecules. | 1,000 steps SD; Weak positional restraints on large molecule heavy atoms (0.1 kcal/mol/Ų); No SHAKE. | Further relaxes the solute with minimal restraints. |

| 5-9 | Gradual relaxation of substituents. | Series of minimizations and short MD runs; Restraints switched from side-chains/nucleobases to backbone. | Allows side-chains to relax before the more structured backbone. |

| 10 | Final unrestrained MD. | MD run until system density plateaus (see 4.1). | Final stabilization before production simulation. |

Software Note: It is recommended that minimization steps be performed in double precision to avoid numerical overflows from large initial forces, even if subsequent MD uses single-precision GPU codes [34].

Visualization of Workflows and Data Interpretation

Assessing System Stabilization

A key test for determining whether a system is stabilized for production simulation is the density plateau test [34]. The system density should be monitored during the final unrestrained MD step (Step 10 of the protocol). Stabilization is achieved when the density fluctuates around a stable average value, indicating that the system has reached a balanced state.

Diagram 1: System preparation workflow.

Application Case: Ion Channel Simulation

MD simulations of the open-conformation bacterial sodium channel (NavMs) illustrate the critical importance of proper system setup. In this study, the channel was embedded in a lipid bilayer, solvated, and ions were placed in the bath. During simulations, ions and water migrated into and through the pore, allowing researchers to characterize ion conductance and selectivity [36]. To maintain the open conformation of the channel's activation gate in the absence of its voltage-sensing domain, harmonic restraints (1 kcal/mol/Ų) were applied to the alpha-carbon atoms of the transmembrane helices [36]. This application underscores how judicious use of restraints during system preparation is essential for studying specific biological questions.

Diagram 2: Full MD setup and simulation pipeline.

Discussion

The rigorous application of a standardized protocol for solvation, ion placement, and minimization is not merely a preliminary exercise but a determinant of simulation success. The ten-step protocol presented here, with its graduated relaxation of positional restraints, systematically addresses the different relaxation timescales of solvent, ion, side-chain, and backbone atoms [34]. Furthermore, the objective criterion of a density plateau provides a clear, quantitative metric for assessing system stabilization, moving beyond subjective judgments.

A critical consideration in atomic tracking research is the assumption that the system has reached thermodynamic equilibrium before production analysis begins. While properties like system density and RMSD may plateau, some studies suggest that full convergence of all biomolecular degrees of freedom may require timescales far beyond typical simulation lengths [37]. Therefore, researchers should interpret simulation results with the understanding that while the system may be in a "stable" state suitable for production simulation, some properties, particularly those dependent on infrequent conformational transitions, may not be fully equilibrated [37]. The protocol herein is designed to establish a stable and well-relaxed starting point, which is the necessary foundation for any meaningful production simulation.

In molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, the choice of thermostat is a critical determinant of the quality and physical validity of the results, particularly for research involving atomic tracking. Thermostats algorithmically control the system temperature by modifying atomic velocities, but differ significantly in their theoretical foundations, sampling correctness, and impact on dynamical properties. This application note provides detailed protocols for implementing three prevalent thermostats—Nose-Hoover, Berendsen, and Langevin—within the context of atomic-scale research, such as tracking diffusion, reaction pathways, or structural changes. Proper configuration of these methods ensures accurate sampling of the canonical (NVT) ensemble, where particle number (N), volume (V), and temperature (T) are constant, which is essential for meaningful comparison with experimental data and robust scientific conclusions [24] [38].

Thermostat Comparative Analysis

Characteristics and Typical Parameters

Table 1: Comparative overview of key thermostat algorithms.

| Feature | Nose-Hoover | Berendsen | Langevin |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ensemble | Canonical (NVT) [24] [38] | Not well-defined; approximate NVT [39] | Canonical (NVT) [24] |

| Algorithm Type | Deterministic (Extended Lagrangian) [24] | Deterministic (Weak-coupling) [39] | Stochastic (Random force & friction) [40] [24] |

| Sampling Quality | Correct [24] | Suppresses fluctuations [24] [39] | Correct [24] |

| Dynamics | Alters dynamics but deterministic [24] | Over-damped, non-physical [24] | Alters dynamics; not for studying dynamics [40] [24] |

| Key Parameter | SMASS (virtual mass) / NHC_NCHAINS (chain length) [38] |

tau_t / thermostat_timescale (relaxation time, ~0.1 ps) [41] [39] |

gamma / friction / LANGEVIN_GAMMA (friction constant, ~1-100 ps⁻¹) [40] [24] [42] |

| Primary Use Case | Production runs requiring correct ensemble sampling [24] | Rapid equilibration and heating/cooling [41] [24] | Sampling and coarse relaxation; disordered systems [40] [24] |

Mathematical Foundations and Operational Principles

The underlying equations of motion reveal the fundamental operational differences between these thermostats.

Langevin Dynamics: This stochastic thermostat adds a friction term and a random force to Newton's second law [40] [24]: [ mi \frac{d^2 \mathbf{r}i}{dt^2} = -\nabla U(\mathbf{r}i) - mi \gamma \mathbf{v}i + \mathbf{\Gamma}i ] Here, ( mi ), ( \mathbf{r}i ), and ( \mathbf{v}i ) are the mass, position, and velocity of atom ( i ), ( U ) is the potential energy, ( \gamma ) is the friction constant, and ( \mathbf{\Gamma}i ) is a Gaussian random force with zero mean and variance ( \langle \mathbf{\Gamma}i(t) \cdot \mathbf{\Gamma}i(t') \rangle = 2 mi \gamma kB T \delta(t - t') ) [40] [43]. The friction and random noise are coupled via the fluctuation-dissipation theorem to ensure correct canonical sampling [24].

Berendsen Thermostat: This weak-coupling algorithm scales velocities by a factor ( \lambda ) at each step to drive the system temperature ( T(t) ) exponentially toward a target ( T ) with a time constant ( \tauT ) [39]: [ \lambda^2 = 1 + \frac{\Delta t}{\tauT} \left( \frac{T}{T(t)} - 1 \right) ] While efficient for relaxation, this global scaling suppresses intrinsic temperature fluctuations, leading to an incorrect ensemble [24] [39].

Nose-Hoover Thermostat: This deterministic method introduces an extended Lagrangian with a fictitious thermal reservoir coordinate ( s ) and its momentum. The equations of motion are [24]: [ \begin{aligned} \frac{d\mathbf{r}i}{dt} &= \mathbf{v}i \ mi \frac{d\mathbf{v}i}{dt} &= -\nabla U(\mathbf{r}i) - \xi \mathbf{v}i \ \frac{d\xi}{dt} &= \frac{1}{Q} \left( \sumi mi vi^2 - g kB T \right) \end{aligned} ] where ( \xi ) is the friction coefficient of the reservoir, ( Q ) is its effective mass (

SMASS), and ( g ) is the number of degrees of freedom. The Nose-Hoover chain variant, which connects multiple thermostats in series, is recommended for robust sampling [24].

Experimental Protocols

General MD Workflow with Thermostat Integration

The following diagram illustrates a standard workflow for configuring and running an NVT simulation, highlighting key decision points for thermostat selection.

Protocol 1: NVT Simulation with Nose-Hoover Chain Thermostat

This protocol uses the Nose-Hoover Chain thermostat for production runs requiring rigorous canonical sampling [24].

- Step 1: System Preparation. Energy-minimize the initial structure using a conjugate gradient or steepest descent algorithm to remove bad contacts. A tolerance of 1-10 kJ/mol/nm is typically sufficient [44].

- Step 2: Initial Velocity Assignment. Assign initial atomic velocities from a Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution at the target temperature

TEBEG(e.g., 300 K) [40] [41]. - Step 3: Thermostat Configuration. In your MD parameter file (e.g.,

INCARfor VASP), set the key parameters [38]:MDALGO = 2(or equivalent in other software) to select the Nose-Hoover thermostat.SMASS(orQ) to control the thermostat mass. A value of1.0is a standard starting point [38]. Larger values lead to slower, more physical temperature oscillations.NHC_NCHAINS = 3(or equivalent) to specify the number of thermostats in the chain, which improves ergodicity [24] [38].

- Step 4: Equilibration Run. Run a short NVT simulation (e.g., 20-100 ps) with a time step appropriate for your system (1-2 fs for light atoms). Monitor the temperature and total energy to confirm stability.

- Step 5: Production Simulation. Once equilibrated, launch a long production run, writing the atomic trajectory at regular intervals (

nstxout,trajectory_filename) for subsequent atomic tracking analysis [40] [41].

Protocol 2: Rapid Thermalization using the Berendsen Thermostat

This protocol is optimal for quickly bringing a system to a target temperature, for example, before switching to a different thermostat for production [24] [39].

- Step 1: Initial Setup. Prepare and minimize the system as in Protocol 1.

- Step 2: Thermostat Configuration. Configure the weak-coupling parameters [41] [39]:

integrator = sd(in GROMACS) ormethod = NVTBerendsen(in QuantumATK).tau_torthermostat_timescale: Set the relaxation time constant. A value of100 fsis a common default, but values around0.1 psare typical for condensed-phase systems [41] [39]. A smallertau_tgives tighter, less physical temperature control.

- Step 3: Run Thermalization. Execute the simulation. The instantaneous temperature will relax exponentially towards the target, with a time profile given by ( T(t) = T - C \exp(-t / \tau_T) ) [39].

- Step 4: Check for Stability. Confirm the temperature has stabilized around the target value. The Berendsen thermostat is not recommended for production analysis due to suppressed energy fluctuations [24] [39].

Protocol 3: Canonical Sampling with Langevin Dynamics

Use this protocol for robust canonical sampling, especially in systems where deterministic thermostats struggle with ergodicity, or for simulating damped dynamics [40] [24].