A Practical Guide to Selecting Solvent Models for Biomolecular Simulation and Drug Development

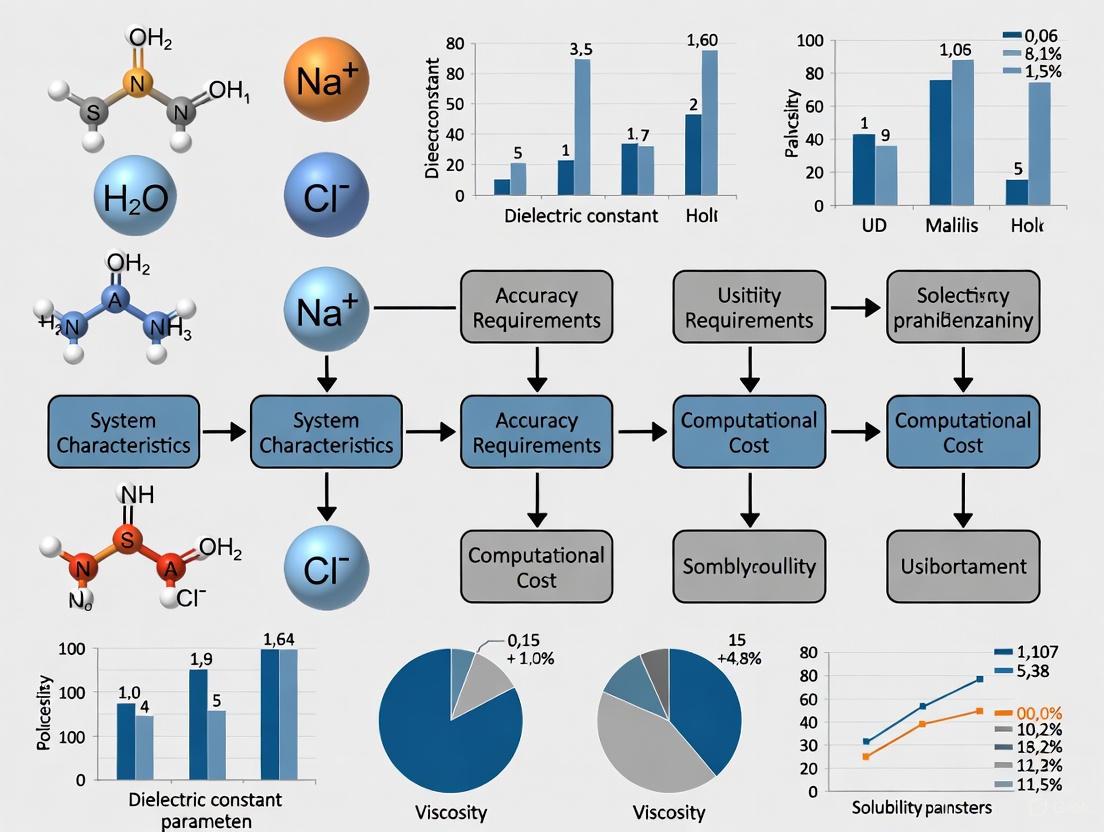

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on selecting appropriate solvent models for computational studies.

A Practical Guide to Selecting Solvent Models for Biomolecular Simulation and Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on selecting appropriate solvent models for computational studies. It covers foundational principles of implicit and explicit solvent models, practical methodologies for implementation across different simulation types, strategies for troubleshooting and optimization, and rigorous validation approaches. By synthesizing insights from quantum chemistry and molecular dynamics, this guide aims to equip scientists with the knowledge to make informed decisions that enhance the predictive accuracy and biological relevance of their simulations, ultimately accelerating drug discovery and development.

Understanding Solvent Models: From Basic Concepts to Advanced Formulations

What is an Implicit Solvent Model?

An implicit solvent model, also known as a continuum model, replaces explicit solvent molecules with a homogeneously polarizable medium. This approach uses a small number of parameters to represent the solvent, with the dielectric constant (ε) being the primary one, often supplemented with additional parameters like solvent surface tension. [1]

In practice, a solute is encapsulated in a tiled cavity embedded within this polarizable continuum. The solute's charge distribution polarizes the surrounding medium at the cavity surface, creating a reaction potential that is iterated to self-consistency. [1] The total solvation free energy (G) is calculated as a sum of contributing components [1]: G = Gcavity + Gelectrostatic + Gdispersion + Grepulsion + G_thermal motion

Common implicit models include the Polarizable Continuum Model (PCM), COSMO, and the Solvation Model based on Density (SMD). [1]

What is an Explicit Solvent Model?

Explicit solvent models treat solvent molecules directly, including their coordinates and molecular degrees of freedom. This provides a physically realistic picture with direct, specific solvent-solute interactions. [1]

These models are typically used in Molecular Mechanics (MM), Molecular Dynamics (MD), or Monte Carlo (MC) simulations. They utilize force fields containing terms for bond stretching, angle bending, torsions, repulsion, and dispersion (e.g., Lennard-Jones potential). [1] Idealized models like TIPXP (for water) simplify calculations by reducing degrees of freedom while retaining accuracy. A new generation of polarizable force fields, such as AMOEBA, is emerging to account for changes in molecular charge distribution. [1]

Key Differences at a Glance

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Implicit vs. Explicit Solvent Models

| Feature | Implicit Models | Explicit Models |

|---|---|---|

| Computational Cost | Generally economical [1] | Less economical, demanding [1] |

| Spatial Resolution | No spatial resolution of solvent [1] | Full spatial resolution [1] |

| Solvent Representation | Dielectric continuum [1] | Individual solvent molecules [1] |

| Description of Solvent Shell | Averaged, fails to capture local fluctuations [1] | Physically resolved, captures solvent ordering [1] |

| Primary Applications | Quantum chemistry (HF, DFT), force field methods [1] | MD simulations, MC simulations [1] |

| Key Parameters | Dielectric constant, surface tension [1] | Point charges, repulsion/dispersion parameters [1] |

Table 2: Performance Characteristics and Typical Use Cases

| Aspect | Implicit Models | Explicit Models |

|---|---|---|

| Sampling Efficiency | High due to instantaneous averaging and reduced viscosity [2] | Lower due to additional solvent degrees of freedom and increased viscosity [2] |

| Accuracy for Bulk Effects | Reasonable for thermally averaged, isotropic solvents [1] | Excellent, provides physical description [1] |

| Accuracy for Local Solvent-Solute Interactions | Poor for specific interactions (e.g., hydrogen bonding) [1] | Excellent for specific interactions and local environment [1] |

| Ideal For | Calculations where solvent is not an active constituent; limited computational resources [1] | Studying specific solvent-solute interactions; reactions where solvent plays a chemical role [1] |

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: My implicit solvent calculations show poor agreement with experimental NMR data for a flexible molecule. What might be wrong? This is a common issue where implicit models may fail to capture explicit solvent effects, particularly specific hydrogen-bonding interactions that influence conformation. A state-of-the-art machine learning approach called QM-GNNIS, which adds a correction to traditional implicit solvents, has been shown to better reproduce experimental NMR and IR trends by emulating explicit-solvent effects. [2] Consider using a hybrid model or a model specifically corrected for explicit effects.

Q2: When should I consider using a hybrid solvent model? Hybrid models are advantageous when you need to model specific solute-solvent interactions (e.g., at an active site) while maintaining computational efficiency for the bulk solvent. QM/MM methods are a prime example, where a QM core (solute + key solvent molecules) is embedded in an MM explicit solvent layer, which may itself be surrounded by an implicit continuum. [1]

Q3: How do I select the right solvent model for drug development applications? For initial screening where computational efficiency is key, robust implicit models like SMD or COSMO-RS are appropriate. [2] However, for detailed studies of binding affinities or conformational dynamics where specific water-mediated interactions are critical (e.g., in protein-ligand docking), explicit solvent MD simulations are necessary despite their higher cost. [1] Tools like the ACS Green Chemistry Institute's Solvent Selection Tool can also inform solvent choice based on physical properties and environmental impact. [3]

Experimental Protocol: Bayesian Optimization for Solvent Selection

Recent research demonstrates a machine learning framework using Bayesian experimental design to efficiently identify optimal solvent mixtures, bypassing traditional trial-and-error. [4]

Objective: Identify high-performance, green solvent blends for extracting valuable chemicals from plant biomass (e.g., lignin).

Materials and Reagents:

- Candidate Solvents: Eight green solvents (e.g., water, alcohols, ethers)

- Automation: Liquid-handling robot (capacity: 40 samples per batch)

- Physics Model: COSMO-RS for initial predictions

Methodology: The process follows an iterative "Design-Observe-Learn" cycle [4]:

Workflow Details:

- Design: Select a set of solvent mixtures. Initially, choose mixtures with high prediction uncertainty to maximize learning ("exploration"). [4]

- Observe: Use automated liquid-handling to experimentally test the selected mixtures and measure the target property (e.g., partition coefficient). [4]

- Learn: Update the statistical model with the new experimental data to improve its predictive accuracy. [4]

- Iterate: As the model improves, shift from "exploration" to "exploitation" by selecting mixtures predicted to have the best performance. To efficiently select batches of 40 mixtures, the researchers used an inner loop with COSMO-RS to generate "fantasy samples" that temporarily update the model, helping identify the 40 most informative mixtures to test next. [4]

Key Advantage: This framework dramatically reduces the number of experiments required, moving from thousands of potential combinations to focusing on dozens of the most promising candidates. [4]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Solutions

Table 3: Key Computational Models and Tools for Solvent Selection Research

| Tool / Model | Type | Primary Function | Key Features / Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| PCM (Polarizable Continuum Model) [1] | Implicit | Models solvent as polarizable continuum | Based on Poisson-Boltzmann equation; widely used in quantum chemistry |

| SMD [1] | Implicit | Solvation Model based on Density | Solves Poisson-Boltzmann equation with parametrized atomic radii |

| COSMO / COSMO-RS [2] [4] | Implicit / Statistical | Conductor-like Screening Model | Uses statistical thermodynamics of surface segments; good for solubility predictions |

| GB-Neck2 [2] | Implicit (Force Field) | Generalized Born model | Approximates electrostatic solvation; commonly paired with force fields |

| AMOEBA [1] | Explicit (Polarizable) | Atomic Multipole Optimized Energetics | Polarizable force field using multipole moments; studies ion solvation |

| TIPnP & SPC [1] | Explicit (Rigid) | Non-polarizable Water Models | Idealized, computationally efficient water models for MD simulations |

| ACS GCI Solvent Selection Tool [3] | Database | Solvent Selection Guide | PCA of 272 solvents based on 70 physical properties; environmental impact data |

| QM-GNNIS [2] | Machine Learning | Graph Neural Network Implicit Solvent | Transfers knowledge from MM to QM; adds explicit-solvent correction to continuum models |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is solvation free energy and why is it critical in pharmaceutical development? Solvation free energy (ΔGsolv) is the free energy change associated with transferring a molecule from an ideal gas phase into a solvent [5]. It is a fundamental thermodynamic property that helps predict key physicochemical parameters in drug design, such as a molecule's solubility, its distribution between different phases (e.g., in partition coefficients), and the desolvation penalty paid when a ligand binds to its target [5]. Accurately predicting it is an exacting test for computational models and force fields [5].

2. How are the polar and non-polar components of solvation free energy defined? The total solvation free energy is typically decomposed into polar and non-polar contributions via a thermodynamic cycle [6].

- Polar Contribution (ΔpG): This is the electrostatic work required to charge the solute's atoms in the solvent versus in a vacuum. It is highly dependent on the solvent's dielectric constant [6].

- Non-Polar Contribution (ΔnG): This is the energy associated with creating a cavity in the solvent to accommodate the solute (cavity formation) and the van der Waals dispersive interactions between the solute and solvent molecules [6].

3. My alchemical free energy calculations show high variance. What could be wrong? High variance often indicates inadequate sampling or issues with the chosen alchemical pathway. Ensure you are using a sufficient number of intermediate λ states, particularly when turning on/off charged groups, to avoid discrete "jumps" in energy. Also, verify that the simulation length at each λ state is long enough for the system to equilibrate and for properties to converge. Using soft-core potentials is essential to avoid singularities when atoms are partially decoupled [5] [7].

4. When should I use an implicit solvent model versus an explicit solvent model? The choice involves a trade-off between computational cost and accuracy.

- Implicit Solvents (e.g., PCM): Use for rapid screening, studying large systems, or when specific solvent structure is not critical. These models represent the solvent as a continuous dielectric medium and are computationally efficient [8] [6].

- Explicit Solvents: Use when specific solute-solvent interactions (e.g., hydrogen bonding) or solvent structure are critical to the phenomenon being studied. Molecular dynamics or Monte Carlo simulations with explicit solvent molecules provide the most detailed picture but are computationally intensive [5].

5. How does solvent polarity influence the properties of a drug molecule? Solvent polarity can significantly alter a drug's electronic properties. For example, Density Functional Theory (DFT) studies on anticancer drugs like 5-Fluorouracil show that a polar solvent environment can stabilize different molecular electrostatic potential (MEP) surfaces and affect frontier molecular orbital energy levels (HOMO-LUMO gap), which in turn can influence chemical reactivity and interaction with biological targets [8].

Troubleshooting Guides

T1: Poor Convergence in Alchemical Free Energy Calculations

Problem: The calculated free energy difference does not converge or shows high statistical error.

| Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|

| Insufficient sampling at one or more intermediate λ states. | Increase the simulation time for each λ window. Focus on states where the system undergoes rapid change, typically where charged groups are being coupled/decoupled. |

| Inadequate number of λ states, leading to large steps between intermediates. | Increase the number of λ states, especially in regions where the Hamiltonian changes non-linearly. A higher density of states provides a more accurate numerical integration of the free energy derivative [5]. |

| System configuration errors, such as incorrect soft-core parameters. | Verify the parameters in your molecular dynamics input file (e.g., sc-alpha, sc-sigma). These parameters help prevent atomic overlaps and singularities when the solute is nearly decoupled [7]. |

| Unphysical interactions or atomic clashes in the initial structure. | Perform a more thorough energy minimization and equilibration protocol for the solvated system before starting the production free energy calculation [7]. |

T2: Inaccurate Partition Coefficient (Log P) Predictions

Problem: Predicted partition coefficients between water and an organic solvent deviate significantly from experimental values.

| Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|

| Inaccurate solvation free energies in one or both pure solvents. | The partition coefficient is calculated from the difference in solvation free energies in the two solvents (log10PA→B = (ΔGsolv,A - ΔGsolv,B)/RTln(10)) [5]. Ensure the force field and methodology are validated for both water and the organic solvent. |

| Neglecting the conformational flexibility of the solute or protonation state changes. | Ensure the solute is in the correct protonation state for both solvent environments. For flexible molecules, ensure sufficient sampling of all relevant conformations in both phases. |

| Force field limitations in describing specific interactions (e.g., π-π stacking). | Consider using a more refined force field or explicitly accounting for polarization effects if standard force fields prove inadequate [5]. |

Experimental Protocols

P1: Calculating Solvation Free Energy using an Alchemical Approach with Explicit Solvent

This protocol outlines the steps for calculating the hydration free energy of a small molecule (e.g., aniline) using molecular dynamics and a non-equilibrium alchemical method [7].

Workflow Diagram: Alchemical Free Energy Calculation

Step-by-Step Methodology:

- System Preparation:

- Generate force field parameters for the solute (e.g., using AmberTools for GAFF2) [7].

- Place a single solute molecule in a simulation box (e.g., a dodecahedron) and solvate it with explicit water molecules (e.g., TIP3P).

- Generate topology files that define the two end states: the fully interacting solute (λ=0) and the non-interacting solute (λ=1).

End-State Equilibration:

- Energy Minimization: Run a steepest descent algorithm to remove any bad contacts using a λ-specific parameter file (

em_l0.mdpfor the solvated state) [7]. - NVT Equilibration: Equilibrate the system with a fixed number of particles, volume, and temperature (e.g., 10 ps) to stabilize the temperature.

- NPT Equilibration: Equilibrate the system with a fixed number of particles, pressure, and temperature (e.g., 6 ns, discarding the first 1 ns) to stabilize the density.

- Energy Minimization: Run a steepest descent algorithm to remove any bad contacts using a λ-specific parameter file (

Sampling and Alchemical Transformation:

- Extract multiple frames (e.g., 100 frames) from the equilibrated NPT trajectory.

- For each frame, run a short non-equilibrium simulation that transforms the solute from the fully interacting state (λ=0) to the non-interacting state (λ=1). This is controlled by a

delta-lambdaparameter that defines the transformation rate [7].

Free Energy Analysis:

- Use the Jarzynski equality (or related methods like Crooks' Theorem) to calculate the free energy difference from the work values of all the non-equilibrium transitions.

P2: Decomposing Solvation Energy using an Implicit Solvent Model (APBS)

This protocol uses the Poisson-Boltzmann equation to calculate the polar solvation energy, often part of a larger cycle that includes non-polar terms [6].

Workflow Diagram: Implicit Solvent Decomposition

Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Polar Solvation Energy (ΔpG):

- Step 1 - Solvent Calculation: Calculate the electrostatic charging energy of the solute in a heterogeneous dielectric environment (solute dielectric, e.g., 1-2; solvent dielectric, e.g., 78.54 for water). Use a molecular surface definition (e.g.,

srad 1.4) [6]. - Step 2 - Vacuum Calculation: Calculate the electrostatic charging energy of the solute in a homogeneous dielectric environment (e.g., dielectric of 1.0). It is critical that the grid spacing, center, and dimensions are identical to the solvent calculation to ensure cancellation of self-energy terms [6].

- Calculation: ΔpG = Energysolvent - Energyvacuum

- Step 1 - Solvent Calculation: Calculate the electrostatic charging energy of the solute in a heterogeneous dielectric environment (solute dielectric, e.g., 1-2; solvent dielectric, e.g., 78.54 for water). Use a molecular surface definition (e.g.,

- Non-Polar Solvation Energy (ΔnG):

- This component is often computed using a model that combines a cavity term and a solute-solvent dispersion term [6].

- Cavity Term (Δ₄G): Estimated as a linear function of the solvent-accessible surface area (SASA) and volume: Δ₄G = pV + γA, where p is solvent pressure, V is solute volume, γ is surface tension, and A is SASA.

- Dispersion Term (Δ₃G - Δ₅G): An attractive term calculated by integrating Weeks-Chandler-Andersen interactions over the solvent-accessible volume [6].

Quantitative Data and Solvent Selection

Table 1: Sample Polar and Non-Polar Contributions for Model Systems

| Solute | Solvent | Polar Contribution (ΔpG, kJ/mol) | Non-Polar Contribution (ΔnG, kJ/mol) | Total ΔGsolv (kJ/mol) | Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Born Ion (q=+1, R=3Å) | Water | -230.6 (Analytical) [6] | - | -230.6 | Implicit (APBS) |

| Aniline | Water | - | - | - | Alchemical [7] |

| Data from specific studies is illustrative. Actual values depend on force field and computational setup. |

Table 2: Solvent Selection Guide (Adapted from CHEM21) [9]

| Solvent | Boiling Pt. (°C) | Safety Score | Health Score | Environment Score | Overall Recommendation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Water | 100 | 1 (Green) | 1 (Green) | 1 (Green) | Recommended |

| Ethanol | 78 | 4 (Yellow) | 3 (Green) | 3 (Green) | Recommended |

| Acetone | 56 | 5 (Yellow) | 3 (Green) | 5 (Yellow) | Recommended |

| Ethyl Acetate | 77 | 5 (Yellow) | 3 (Green) | 3 (Green) | Recommended |

| Diethyl Ether | 35 | 10 (Red) | - | - | Hazardous |

| Methanol | 65 | 4 (Yellow) | 7 (Red) | 5 (Yellow) | Problematic |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Software and Models for Solvation Studies

| Tool Name / Model | Primary Function | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| GROMACS (with PMX) [7] | Molecular dynamics package for running alchemical free energy calculations with explicit solvent. | Requires system preparation and topology generation; efficient for complex molecules and proteins. |

| APBS [6] | Solves Poisson-Boltzmann equations for implicit solvation calculations. | Ideal for rapid calculation of polar solvation energies; sensitive to grid parameters and surface definitions. |

| GAFF2 (General Amber Force Field) [7] | Provides force field parameters for a wide range of organic drug-like molecules. | Parameters are derived to be generally applicable; may require validation for specific chemical classes. |

| Polarizable Continuum Model (PCM) [8] | An implicit solvent model implemented in quantum chemistry codes (e.g., Gaussian) to study solvent effects. | Used with DFT (e.g., B3LYP) to study electronic structure changes in different solvents; good balance of cost and accuracy for single molecules. |

| FreeSolv Database [5] | A public database of experimental and calculated hydration free energies for neutral compounds. | Serves as a critical benchmark for validating computational methods and force fields. |

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What is the fundamental difference between an implicit and an explicit solvent model? Implicit solvent models replace the explicit solvent molecules with a continuous, polarizable medium that exerts a mean force on the solute. This is computationally much less expensive than explicit solvent models, which treat each solvent molecule individually. Implicit models are ideal for studying bulk solvent effects where specific solute-solvent interactions (like defined hydrogen bonds) are not the primary focus [10] [11].

2. My geometry optimization with a solvent model fails to converge. What could be the problem? Some older implementations of polarizable continuum models (PCMs) could lead to discontinuities in the potential energy surface, causing severe convergence issues in geometry optimizations and frequency calculations. Modern implementations, like the Switching/Gaussian (SWIG) approach in Q-Chem, are designed to produce smooth, continuous potential energy surfaces to resolve this problem. Ensuring you are using an updated software version with a smooth PCM implementation is recommended [12].

3. For a drug-like molecule, which model should I use to predict solvation free energy accurately? The SMD model is a strong candidate as it is designed to achieve high accuracy for solvation free energies of neutrals and ions in a wide range of solvents. It combines the IEF-PCM method for electrostatics with a term for cavity-dispersion-solvent-structure (CDS). The SMx family of models (like SM8) are also parameterized to reproduce experimental solvation free energies and can achieve sub-kcal/mol accuracy for neutral molecules [12] [11].

4. I am simulating a peptide. Why might a Generalized Born (GB) model give poor results? While GB models are fast, their performance is highly dependent on the specific combination of the GB model and the molecular force field. A recent study testing 65 different force field-GB combinations on designed peptides found that they often failed to reproduce experimentally observed secondary structures (like α-helix content) and could predict unrealistic conformations. For biomolecular simulations, it is crucial to consult literature validating your specific force field-GB combination for similar systems, and consider that explicit solvent may be necessary for reliable results [13].

5. How do I choose between CPCM, IEF-PCM, and COSMO? These are all "apparent surface charge" models but with different theoretical underpinnings. CPCM uses conductor-like boundary conditions, which simplifies the calculations and can make it less sensitive to the "outlying charge" error. IEF-PCM (equivalent to SS(V)PE) is a more versatile and theoretically rigorous integral equation formalism. COSMO is very similar to CPCM but often includes a specific correction for the solute electron density that penetrates outside the cavity. The best choice can be system-dependent, and benchmarking against known experimental data is advised [12] [14] [11].

6. Can I use implicit solvent models for excited state calculations? Yes, many modern implementations support excited state calculations. However, you may need to specify additional parameters, such as the solvent's refractive index, in the input file, as this property becomes relevant for electronic excitations [15].

Troubleshooting Common Issues

| Issue | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Unphysical Solvation Energies | Poorly defined cavity due to inappropriate atomic radii. | Use the atomic radii set that is specifically parameterized for your chosen solvent model (e.g., the Bondi set for SMD). |

| SCF Convergence Failure | Strong coupling between the solute's electron density and the solvent reaction field. | Use the "Dielectric" keyword to loosen the convergence criteria for the PCM step initially. Start the optimization from a gas-phase converged density. |

| Discontinuous Potential Energy Surface | Use of a discretized boundary-element method that is not smooth. | Switch to a smooth PCM implementation, such as the SWIG (Switching/Gaussian) method available in Q-Chem [12]. |

| Poor Performance for Ions | Inaccurate description of the strong electrostatic interactions and specific solvation effects. | Use a model specifically parameterized for ions, such as SMD or SMx models, and be aware that errors are typically higher for ions than for neutral molecules [12]. |

| Geometry Optimization Fails | The cavity changes discontinuously with nuclear coordinates. | Ensure you are using a modern, smooth PCM implementation. As a workaround, perform a single-point energy calculation on a gas-phase optimized geometry, as geometries in solution and vacuum are often similar [12] [15]. |

Model Comparison and Selection Guide

The table below summarizes the key characteristics of the major implicit solvent models to guide your selection.

Table 1: Overview of Major Implicit Solvent Models

| Model | Full Name | Key Features | Cavity Construction | Recommended Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCM [12] | Polarizable Continuum Model | A family of models; includes C-PCM and IEF-PCM. | Atom-centered spheres | General-purpose solvation for a wide range of chemical systems. |

| CPCM [14] | Conductor-like Polarizable Continuum Model | Uses conductor-like boundary conditions; simpler and less prone to outlying charge error. | Atom-centered spheres (vdW) or GEPOL algorithm | A robust default for electrostatic solvation in polar solvents. |

| COSMO [12] [16] | COnductor-like Screening Model | Similar to CPCM but often includes an outlying charge correction. | Predefined atomic spheres | COSMO-RS calculations for predicting fluid phase thermodynamics [16]. |

| SMD [12] | Solvation Model based on Density | Combines IEF-PCM electrostatics with a CDS term for non-electrostatic effects. | Predefined atomic spheres | High-accuracy solvation free energies for diverse solvents and solutes (neutrals and ions). |

| GB [10] [13] | Generalized Born | A fast approximation to the Poisson equation. | Predefined atomic spheres | Long, classical molecular dynamics simulations of biomolecules where speed is critical. |

Table 2: Typical Performance Characteristics (Based on Benchmarking Studies)

| Model | Reported MUE for Small Molecules (kcal/mol) | Key Strengths | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| SMD [12] [11] | ~0.2 - 4.0 (ions) | High accuracy across many solvents; parameterized for neutrals and ions. | More computationally expensive than simpler models. |

| SM8 [12] | <1.0 (neutrals) | Sub-kcal/mol accuracy for neutral molecules. | Parameterized for specific basis sets; higher errors for ions (~4 kcal/mol). |

| CPCM [17] | Varies with parameterization | Simple, robust, and widely available. | Accuracy depends heavily on cavity definition and radii. |

| GB [13] [17] | Varies significantly | Extremely fast, enabling large-scale MD. | Performance is highly force-field dependent; can be unreliable for peptides/proteins [13]. |

| ML-PCM [11] | ~0.4 - 0.5 | Improved accuracy over standard PCM with no major computational overhead. | Requires a specially trained model; not yet a standard method. |

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol 1: Calculating a Solvation Free Energy using an Implicit Model in ORCA

This protocol outlines the steps for a single-point solvation energy calculation using the CPCM model in ORCA.

Input File Preparation: Create an input file (.inp) with the following structure:

The

CPCM(Water)keyword directly invokes the model. Replace "Water" with another solvent from the built-in list (e.g., "Acetonitrile") as needed [14] [15].Job Execution: Run the calculation using the ORCA executable.

$ orca molecule.inp > molecule.outOutput Analysis: Upon successful completion, the output file will contain a section like this:

The

Corrected G(solv)is the key quantity, representing the total solvation free energy. To compute the free energy of solvation, you must perform a separate calculation in the gas phase (without theCPCMkeyword) and subtract the total energies: ΔGsolv = Esolution - Egas [15].

Protocol 2: Validating a Solvent Model for a Specific Application

Before applying a model to a new system, it is good practice to validate it.

- Define a Test Set: Assemble a small set of molecules with known experimental properties (e.g., solvation free energy, pKa, spectral shift) that are relevant to your study.

- Select Candidate Models: Choose 2-3 implicit models based on the criteria in Table 1 (e.g., SMD and CPCM).

- Run Calculations: Perform geometry optimization and single-point energy calculations (as in Protocol 1) for each molecule in the test set using each candidate model.

- Analyze Performance: Calculate the mean unsigned error (MUE) and correlation coefficient (R²) between the computed and experimental values.

- Select Model: Choose the model with the best combination of accuracy and computational efficiency for your specific system.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Software and Parameterization "Reagents"

| Item | Function in Implicit Solvation | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Quantum Chemistry Code | Provides the electronic structure theory engine and implements the solvation models. | Q-Chem [12], ORCA [14] [15], Gaussian [18]. |

| Atomic Partial Charges | Define the electrostatic potential of the solute, which polarizes the continuum. | Can be Mulliken, Natural Population Analysis (NPA), or from restrained electrostatic potential (RESP) fits. The choice impacts results [18] [17]. |

| Atomic Radii | Define the size and shape of the cavity that separates the solute from the continuum. | Bondi radii, Pauling radii, or model-specific parameterized radii (e.g., the optimized set in SMD). This is a critical parameter. |

| Dielectric Constant (ε) | A macroscopic property of the solvent that determines its polarizability. | ε=80 for water, ε=4 for a crude protein environment model [15]. |

| Surface Generation Algorithm | Defines how the cavity surface is discretized for calculating polarization charges. | GEPOL (for SES or SAS) [14] or Gaussian surfaces (e.g., SWIG) [12]. |

Method Selection and Application Workflow

The following diagram illustrates a logical decision process for selecting and applying an implicit solvent model.

FAQs: Core Concepts and Parameter Selection

Q1: How do dielectric constant and surface tension fundamentally influence solvent behavior? The dielectric constant (DC) and surface tension (ST) are intrinsic solvent properties that govern intermolecular interactions. The dielectric constant measures a solvent's ability to reduce electrostatic forces between charged particles; a high DC indicates a polar solvent that can stabilize ions and separate charges. Surface tension measures the cohesive energy at a liquid's interface, representing the energy required to increase its surface area; lower ST often correlates with better wetting and spreading on solid surfaces [19] [20]. For polar liquids on a polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) coating, contact angle hysteresis (CAH) is controlled by the liquid's DC, whereas for non-polar liquids, CAH is controlled by the liquid's ST [20].

Q2: When should I prioritize dielectric constant over surface tension when selecting a solvent? Prioritize the dielectric constant when your process involves ionic species, dipole-dipole interactions, or charged transition states. This is critical for reactions like SN1, Grignard synthesis, or electrochemical applications. Surface tension should be prioritized when the process is governed by wetting, adhesion, coating, or dispersion, such as in formulating inks, paints, polymer coatings, or controlling droplet dynamics [21] [20]. For liquid repellency, the difference between the solubility parameters of the surface and the liquid is the most decisive factor for CAH, followed by differences in DC and ST [20].

Q3: Can Hansen Solubility Parameters (HSP) integrate the effects of dielectric constant and surface tension? Hansen Solubility Parameters provide a more nuanced framework than single-parameter models by dividing cohesion energy into three components: dispersion forces (δd), polar interactions (δp), and hydrogen bonding (δh) [19] [21]. While not directly equivalent, the polar component (δp) relates to dielectric effects, and the dispersion component (δd) connects to surface tension. HSP successfully predicts miscibility, polymer swelling, and solubility by determining the "distance" in this 3D parameter space between a solute and solvent [21]. The total HSP is related to surface tension via empirical equations such as γ = 0.0133 * (Vm)^(1/3) * δ², where Vm is the molar volume and δ is the total Hansen parameter [19].

Q4: What are the limitations of using only dielectric constant and surface tension for solvent selection? While dielectric constant and surface tension are foundational, they have limitations. They may not fully capture specific interactions like hydrogen bonding strength, Lewis acidity/basicity, or steric effects. For instance, water and formamide have similar high dielectric constants but vastly different hydrogen-bonding capabilities and solvation behaviors. Similarly, solvents with identical surface tension can differ significantly in polarity. Advanced models like the Abraham solvation parameter model or machine learning approaches incorporate additional descriptors (e.g., hydrogen-bond acidity/basicity, excess molar refraction) for more accurate predictions, especially for complex pharmaceutical molecules or multicomponent solvent systems [22] [23] [24].

Q5: How are modern machine learning (ML) models overcoming the limitations of traditional parameters? Machine learning models bypass the need for explicit physical parameters by learning complex, non-linear relationships directly from large datasets. For example, the fastsolv model uses molecular descriptors to predict solubility across temperatures and solvent classes, capturing effects that simple parameters miss [21]. For multicomponent solvent systems, Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) with semi-supervised learning frameworks can unify experimental and computational data (e.g., from COSMO-RS) to significantly expand chemical space coverage and improve prediction accuracy [23]. These models can handle multivariate inputs, including temperature, solvent composition, and molecular structure, to deliver precise, quantitative solubility predictions rather than simple miscibility rankings [21] [24].

Troubleshooting Guides

Table 1: Common Experimental Issues and Solutions Related to Solvent Parameters

| Problem Phenomenon | Potential Root Cause | Diagnostic Checks | Corrective Actions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Poor Solubility or Precipitation | Mismatch of Solubility Parameters (SP) or Polarity. | 1. Calculate HSP or Hildebrand parameter for solute and solvent.2. Check dielectric constant; low DC may not dissolve polar/ionic solutes. | 1. Use a solvent with HSP closer to the solute.2. Use a binary solvent mixture to fine-tune the overall SP and DC [21]. |

| Inconsistent Coating or Wetting | High solvent surface tension leading to poor spreading. | Measure the contact angle on the substrate. A high angle indicates poor wetting. | 1. Switch to a solvent with lower surface tension.2. Add a surfactant to lower the overall ST. |

| Unexpected Reaction Kinetics/Yield | Incorrect solvent polarity affecting reaction pathway/transition state. | Verify the solvent's dielectric constant against reaction mechanism requirements. | Select a solvent with a dielectric constant appropriate for the reaction type (e.g., high DC for ionic mechanisms). |

| High Contact Angle Hysteresis (CAH) on PDMS-like surfaces | Strong interaction due to mismatched physicochemical properties. | Check the liquid's DC (for polar liquids) and ST (for non-polar liquids) against the surface properties [20]. | For minimal CAH, choose liquids with a small difference in SP from the surface, and for polar liquids, a low DC [20]. |

| Inaccurate Solubility Prediction | Over-reliance on simple parameters for complex molecules. | Compare predictions from HSP versus ML models (e.g., fastsolv). | Use machine learning models that integrate multiple molecular descriptors and temperature for more reliable predictions [23] [21] [24]. |

Table 2: Key Solvent Parameters and Their Typical Ranges

| Solvent | Dielectric Constant (at ~20°C) | Surface Tension (mN/m, at ~20°C) | Hansen Solubility Parameters (δd, δp, δh) [MPa1/2] | Key Applications and Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Water | 79.7 [20] | 72.8 [20] | (15.5, 16.0, 42.3) [21] | High polarity, strong hydrogen bonding. Challenging for HSP models due to extreme δh [21]. |

| Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO) | ~47 | - | - | Powerful polar aprotic solvent, high DC for dissolving polar compounds. |

| Methanol | ~33 | 22.3 [20] | (14.7, 12.3, 22.3) [21] | Polar protic, self-associates; modified HSP values are often used [21]. |

| Ethanol | ~24.5 | 22.1 [20] | (15.8, 8.8, 19.4) [21] | Polar protic, common in pharmaceutical formulations. |

| 1-Butanol | ~17.5 | 24.9 [20] | (16.0, 5.7, 15.8) [21] | Less polar alcohol, used in mixtures. |

| Toluene | 2.4 [20] | 28.5 [20] | (18.0, 1.4, 2.0) [21] | Non-polar solvent, low DC, good for dispersive interactions. |

| n-Hexadecane | ~2.1 | 27.5 [20] | (16.3, 0, 0) [21] | Non-polar, very low DC. Used as a reference in solubility models [22]. |

Experimental Protocol 1: Determining the Role of Parameters in Surface Wettability

Objective: To systematically investigate how a liquid's dielectric constant and surface tension influence its static and dynamic contact angles on a model PDMS coating.

Materials:

- Surfaces: Polished silicon wafers or glass slides.

- Coating Reagent: Dimethyldimethoxysilane (DMDMS) for preparing PDMS brush coating [20].

- Probe Liquids: A selection covering a range of DC and ST (see Table 2). Examples: Water, DMSO, DMF, Acetonitrile, Ethanol, 1-Propanol, 1-Butanol, 1-Octanol, Diiodomethane, 1,4-Dioxane, Toluene, n-Hexadecane [20].

- Equipment: Tensiometer (e.g., DataPhysics OCA20), plasma cleaner, atomic force microscope (AFM) for surface roughness verification.

Methodology:

- Substrate Preparation: Clean glass slides with isopropanol (IPA). Treat with air plasma for 2 minutes to activate the surface [20].

- PDMS Coating Synthesis: Prepare a solution of 10 g IPA, 1 g DMDMS, and 0.1 g sulfuric acid. Stir for 30 seconds and let sit for 30 minutes at room temperature. Submerge the plasma-treated slide in this solution for 10 seconds. Dry the slide at room temperature for 20 minutes, then rinse sequentially with water, IPA, and toluene to remove unreacted components [20].

- Surface Characterization: Use AFM to confirm the smoothness of the coating (root-mean-square roughness typically <1 nm).

- Contact Angle Measurement:

- Static CA: Dispense a 5 µL droplet of each probe liquid and measure the static contact angle.

- Advancing/Receding CA: For the same droplet, slowly add then withdraw liquid (e.g., 5 µL) while recording the maximum (advancing) and minimum (receding) angles.

- Calculate CAH: CAH = θadvancing - θreceding.

- Perform at least 5 measurements per liquid and average the results.

Data Analysis:

- Plot Static CA and CAH against the liquid's known DC, ST, and its solubility parameter difference from PDMS (∆SP).

- Perform regression analysis to determine which parameter (DC, ST, or ∆SP) is the dominant factor for CAH for polar and non-polar liquids separately [20].

Diagram 1: Workflow for analyzing solvent parameters' impact on wettability.

Experimental Protocol 2: Building a Machine Learning Model for Solubility Prediction

Objective: To develop a Bayesian Neural Network (BNN) model for predicting the solubility of a small-molecule pharmaceutical (e.g., Rivaroxaban) in binary solvent systems at different temperatures.

Materials:

- Data Source: Curated experimental solubility dataset (e.g., MixSolDB [23] or a dataset for a specific API like Rivaroxaban [24]).

- Software: Python with libraries: TensorFlow/Keras, RDKit, scikit-learn.

- Descriptors: Solvent composition (mass/volume fraction), temperature, and encoded solvent identities.

Methodology [24]:

- Data Preprocessing:

- Encoding: Apply one-hot encoding to categorical variables (e.g., solvent names).

- Normalization: Scale all numerical features (e.g., temperature, composition) to a [0, 1] range using Min-Max normalization:

X_scaled = (X - X_min) / (X_max - X_min). - Outlier Detection: Use the Elliptic Envelope algorithm to identify and remove outliers from the dataset.

- Data Splitting: Split the cleaned dataset into training (85%) and testing (15%) sets.

- Model Building (BNN):

- Treat the network's weights (W) and biases (b) as probability distributions (e.g., Gaussian priors) rather than fixed values.

- Use a probabilistic framework to compute the posterior distribution of the model parameters given the training data.

- Model Training & Hyperparameter Tuning:

- Use the Stochastic Fractal Search (SFS) algorithm to optimize hyperparameters (e.g., learning rate, number of hidden layers/units).

- Train the model to minimize a loss function (e.g., Mean Absolute Error).

- Model Validation:

- Evaluate the model on the held-out test set using metrics: R², Mean Squared Error (MSE), Mean Absolute Error (MAE), and Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE).

Data Analysis:

- A successfully trained BNN model for Rivaroxaban solubility can achieve a test R² > 0.99, indicating excellent predictive performance [24].

- The model provides not only a point prediction but also a measure of uncertainty, which is crucial for risk assessment in pharmaceutical development.

Diagram 2: Workflow for building a machine learning solubility model.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Computational Tools for Solvent Model Research

| Item | Function / Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| High-Purity n-Alkanes (e.g., n-Hexane, n-Heptane) [25] | Non-polar reference solvents; used in calibration of chromatographic systems and surface tension studies. | Chemically inert, low dielectric constant, stable in storage. Purity >99% is often critical. |

| Polar Aprotic Solvents (e.g., DMSO, DMF, Acetonitrile) | Solvents for reactions involving anions or charged transition states; high dielectric constant, low hydrogen bond donor ability. | High dipole moment, good solvating power for cations. |

| PDMS Coating Components (DMDMS) [20] | Creating a model low-energy, smooth surface for studying fundamental wetting and repellency phenomena. | Creates a covalently bound brush coating with liquid-like chain mobility. |

| Hansen Solubility Parameter Set | Experimental kit for determining the HSP of an unknown polymer or solute via solubility tests in a range of predefined solvents. | Contains ~20 solvents covering a wide range of δd, δp, δh values. |

| Abraham Solvation Parameter Descriptors [22] | A consistent set of six compound descriptors (E, S, A, B, V, L) for predicting partition coefficients and free-energy related properties in any system with known system constants. | Provides a comprehensive description of a molecule's capability for various intermolecular interactions. |

| Graph Neural Network (GNN) Framework [23] | Advanced machine learning architecture for predicting properties (e.g., solubility) in complex, multi-component solvent systems by learning from molecular graphs. | Can model complex solute-solvent and solvent-solvent interactions directly from molecular structure. |

| COSMO-RS Software [23] | A quantum chemistry-based method for predicting thermodynamic properties, used to generate data for training machine learning models where experimental data is scarce. | Based on the molecular surface polarization charge density. |

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What are the most common types of errors encountered when setting up molecular simulations, and how can I fix them? Common errors often occur during the system setup phase, particularly with topology generation and memory allocation.

- Residue not found in database: This error in tools like

pdb2gmxindicates a missing force field entry for a molecule. Solutions include checking for alternative residue names in the database, manually parameterizing the molecule, or finding a pre-existing topology file from literature [26]. - Out of memory errors: This happens when the system is too large for available RAM. Solutions involve reducing the number of atoms selected for analysis, shortening the simulation length, or using a computer with more memory. Be aware that unit confusion (e.g., Ångström vs. nm) can accidentally create a system 1000 times larger than intended [26].

- Invalid order for directives in topology files: Simulation packages like GROMACS require a specific order for directives in topology (

.top) and parameter (.itp) files. Ensure the[defaults]directive is first, followed by[atomtypes]and other[*types]directives, and then[moleculetype]directives. Misplaced#includestatements for additional molecules are a frequent cause [26].

2. My process simulation fails to converge. What are the best practices for troubleshooting? Convergence issues in process simulation software (e.g., Aspen HYSYS, UniSim) are often related to input specifications and solver settings [27].

- Check input data: Ensure all input data is realistic and consistent. This includes selecting an appropriate thermodynamic property package for your chemical system, defining accurate stream compositions and operating conditions, and verifying equipment specifications. Avoid default values without verification [27].

- Review simulation settings: Solver tolerances that are too strict can prevent convergence, while those that are too loose can yield inaccurate results. Start with default or recommended settings. For challenging flowsheets with recycles, use "tear" streams and increase the number of iterations allowed [27].

- Modify simulation strategy: Simplify the model by minimizing the use of recycle operations initially. Start with a basic simulation and gradually add complexity. Using dimensionless specifications like reflux or feed-to-solvent ratios can sometimes improve convergence stability [27].

3. How can I improve the accuracy of my machine learning model for solubility prediction when experimental data is limited? Data scarcity is a key challenge for ML model generalizability. Advanced techniques can leverage other data sources to enhance performance.

- Use Multi-Task Learning (MTL): Train a single model on multiple related tasks. For example, a model can be trained simultaneously on scarce experimental diffusivity data and more abundant, lower-accuracy computational data generated from molecular dynamics simulations. This helps the model learn more robust patterns [28].

- Employ Physics-Enforced Learning: Incorporate known physical laws into the model to guide its learning. For solvent diffusivity, this can involve encoding the empirical power-law relationship between a solvent's molar volume and its diffusivity, or using the Arrhenius equation to model temperature dependence. This improves predictions for molecules not seen during training [28].

- Adopt a Semi-Supervised Framework: In graph neural networks (GNNs) for multicomponent solvent systems, a "teacher-student" distillation framework can be used. A "teacher" model is first trained on a large amount of computationally generated data (e.g., from COSMO-RS calculations). This knowledge is then transferred to a "student" model trained on a smaller set of high-fidelity experimental data, significantly improving its accuracy [23].

4. What is the trade-off between model accuracy and computational cost for different solvent modeling approaches? The choice of model often involves a balance between the level of physical detail and the resources required. The table below summarizes this trade-off for common approaches.

| Modeling Approach | Typical Accuracy | Computational Cost | Key Characteristics & Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quantum Mechanics (QM) with Explicit Solvent [29] | Very High | Extremely High | Models every solvent molecule with electronic structure theory. Intractable for large systems or long timescales. |

| Molecular Dynamics (MD) with Explicit Solvent [28] [29] | High | High | Uses classical force fields; good for dynamics and specific interactions. Cost scales with number of solvent molecules. |

| Machine-Learned Potentials (MLPs) [29] | High (QM-level) | Medium-High | ML surrogates for QM; offer QM accuracy at lower cost. Require significant data and training, but enable fast simulations. |

| Continuum Solvation Models (e.g., COSMO-RS, SMD) [23] [30] | Medium | Low-Medium | Treats solvent as a continuum; fast for high-throughput screening but may miss specific molecular interactions [29]. |

| Machine Learning (e.g., Graph Neural Networks) [31] [23] | Medium-High (data-dependent) | Very Low (after training) | Fast predictions once trained. Accuracy depends on quality and size of training data; may not extrapolate well. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Resolving "Atom Not Found" and Topology Errors in Molecular Dynamics

Problem: Errors during the pdb2gmx step, such as Atom X in residue YYY not found in rtp entry or WARNING: atom X is missing [26].

Protocol:

- Diagnosis: Identify the specific residue and atom causing the error from the software output.

- Check Hydrogen Atoms:

- Use the

-ignhflag to ignore all hydrogens in the input file and allowpdb2gmxto add them correctly according to the force field database [26]. - If not using

-ignh, verify that hydrogen atom names in your coordinate file exactly match those defined in the force field's residue topology (.rtp) file.

- Use the

- Check Terminal Residues: For N- or C-terminal residues in proteins, ensure the residue name in the PDB file matches the force field's convention (e.g.,

NALAfor an N-terminal alanine in AMBER force fields) [26]. - Check for Missing Non-Hydrogen Atoms: Look for

REMARK 465orREMARK 470entries in your PDB file, which often indicate atoms missing from the experimental structure. These atoms must be modeled back in using specialized software before runningpdb2gmx[26]. - Final Verification: After corrections, re-run

pdb2gmxand check for any further warnings or errors before proceeding to the next simulation step.

Guide 2: Improving Generalizability of Data-Limited Solubility ML Models

Problem: A machine learning model for solubility or solvation free energy performs well on its training data but poorly on new, unseen molecules.

Protocol:

- Data Augmentation with Computational Data:

- Model Training with Semi-Supervised Distillation:

- Train the Teacher: Train a initial "teacher" model (e.g., a Graph Neural Network) on the large, computationally generated dataset [23].

- Train the Student: Train a second "student" model on a much smaller set of experimental data. During training, use the predictions of the "teacher" model as a soft target for the student model, in addition to the hard experimental targets. This is the core of the Semi-Supervised Distillation (SSD) framework [23].

- Incorporate Physical Laws:

- For properties like solvent diffusivity in polymers, enforce physical relationships directly in the model's architecture or loss function. For example, ensure the model's predictions respect the inverse relationship between solvent molar volume and its diffusivity through a polymer matrix [28].

- Validation: Always test the final model's performance on a held-out test set composed solely of experimental data to validate its real-world applicability.

The workflow for enhancing model generalizability through these methods can be visualized as follows:

Guide 3: Systematic Troubleshooting of Process Simulation Convergence

Problem: A steady-state process simulation fails to converge or produces unrealistic results.

Protocol:

- Verify Thermodynamic Model: Confirm that the selected property package (e.g., NRTL, Peng-Robinson) is appropriate for the chemical components and phases in your system. An incorrect choice is a primary source of errors [27].

- Simplify the Flowsheet:

- Deactivate Recycle Loops: Temporarily break recycle loops by replacing the recycle stream with a feed stream whose conditions you can estimate. This helps isolate the problem to a specific unit operation [27].

- Use Tear Streams: If available, use the software's "tear stream" functionality for recycles, which can be more robust than direct substitution methods [27].

- Adjust Solver Settings:

- Check for Over-specification: Ensure that you have not provided too many specifications for a unit operation, creating conflicting constraints. Use more flexible input specifications like ratios (e.g., reflux ratio) where possible [27].

- Reintroduce Complexity: After achieving convergence with the simplified model, systematically reactivate deactivated elements (recycles, logical operations) one by one, ensuring the simulation remains stable at each step [27].

This table lists key computational tools and data resources used in modern solvent model research.

| Tool / Resource | Function | Relevance to Solvent Model Selection |

|---|---|---|

| Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) [23] | ML architecture that operates on molecular graph structures. | Ideal for predicting properties like solvation free energy by directly learning from molecular structure, capturing interactions in multi-solvent systems. |

| COSMO-RS [23] [30] | A quantum-chemistry based method for predicting thermodynamic properties. | Used for high-throughput generation of solvation data (e.g., ΔGsolv) to augment limited experimental datasets for ML training [23]. |

| Machine-Learned Potentials (MLPs) [29] | ML-based surrogates for quantum mechanical potential energy surfaces. | Enables highly accurate (near-QM) molecular dynamics simulations of explicit solvent systems at a fraction of the computational cost. |

| BigSolDB / MixSolDB [31] [23] | Large, curated databases of experimental solubility and solvation data. | Provides essential ground-truth data for training and validating predictive models for single and multi-component solvent systems. |

| Physics-Enforced Neural Networks [28] | ML models that incorporate physical laws as constraints. | Improves model generalizability and physical realism, e.g., by enforcing known relationships between molar volume, temperature, and diffusivity. |

| Semi-Supervised Distillation (SSD) [23] | A framework to transfer knowledge from a large, weak dataset to a small, strong dataset. | Key technique for creating accurate models when experimental data is scarce but computational data is abundant. |

The logical relationship and selection pathway for different modeling approaches based on the project's goals and constraints is summarized below:

Implementation Strategies: Matching Solvent Models to Your Research Application

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is the recommended solvent model in Gaussian for calculating solvation free energies (ΔG)?

For calculating solvation free energies (ΔG), the SMD solvation model is the recommended choice. SMD is a variation of the IEFPCM method and is specifically designed for accurate solvation free energy calculations. You would perform separate calculations in the gas phase and using SCRF=SMD, with the difference in energies yielding the solvation free energy [32].

What is the difference between equilibrium and non-equilibrium solvation for excited states?

The solvent responds to solute changes on different timescales. For excited state calculations, this leads to two distinct approaches [32]:

- Equilibrium Solvation: The solvent has fully responded to the solute's new electronic state (both electronic polarization and solvent molecule reorientation). This is the default for geometry optimizations in solution (e.g., using CIS or TD-DFT) and for the external iteration approach.

- Non-Equilibrium Solvation: The solvent's electronic polarization responds instantly, but the slower reorientation of solvent molecules does not have time to adjust. This is appropriate for fast processes like vertical electronic excitation and is the default for single-point CIS and TD-DFT energy calculations using the default PCM procedure.

How do I fix the "FormBX had a problem" or "Error in internal coordinate system" error during geometry optimization?

This error often occurs when several atoms become linearly aligned during an optimization, causing a failure in the internal coordinate system. Solutions include [33]:

- Using Cartesian coordinates: Add

opt=cartesianto your route section. This method is robust but may require more optimization steps. - Restarting the optimization: Sometimes, re-optimizing the final structure from the failed calculation can resolve the issue, as Gaussian may automatically add linear bends.

What should I do if my calculation fails with "Illegal ITpye or MSType generated by parse"?

This is an input syntax error. The error message marks the problematic part of your route line with a ' character. Carefully check your keywords for typos or incompatible combinations. For example, you cannot use the sp (stockholder potential) keyword with freq simultaneously [33].

Why does my calculation terminate with "There are no atoms in this input structure"?

This error occurs when Gaussian cannot find the molecular structure specification. Common causes are [33]:

- Forgetting to include the molecular geometry (coordinates) in your input file.

- Intending to read the geometry from a checkpoint file but omitting the

geom=checkkeyword from your route section.

Troubleshooting Common SCRF Errors

| Error Message | Description & Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

End of file in ZSymb. |

Input file is missing the blank line after the geometry specification, or geom=check was forgotten [33]. |

Add a blank line after the geometry or add geom=check to the route line. |

Found a string as input. |

Gaussian cannot interpret the charge/multiplicity line. Often, the title line or charge/multiplicity line is missing [33]. | Ensure your input has a title line followed by the charge and spin multiplicity on the next line. |

Variable index is out of range |

In Z-matrix input, a variable is used that has not been defined, or an atom is defined using a non-existent atom [33]. | Correct the variable name or the atom label in the Z-matrix. |

Error imposing constraints |

The optimizer cannot find a minimum under the applied constraints (e.g., in opt=modredundant or QST2 calculations) [33]. |

For QST2, try TS(Berny) or QST3. For constrained opt, modify the initial geometry or use a smaller step size. |

Linear search skipped for unknown reason. |

The Hessian may be invalid during a rational function optimization (RFO) step [33]. | Restart the optimization using opt=calcFC to recalculate the initial Hessian. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Calculating Solvation Free Energy (ΔG_solv)

Objective: To compute the solvation free energy of a molecule using the SMD model in Gaussian [32].

Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Gas Phase Single-Point Energy Calculation:

- Route:

#p M06-2X/6-31G(d) opt - Procedure: Perform a geometry optimization in the gas phase. Upon completion, note the final single-point energy (e.g., from the "SCF Done" line in the log file). This is E_gas.

- Example Input:

- Route:

- Solution Phase Single-Point Energy Calculation:

- Route:

#p M06-2X/6-31G(d) SCRF=(SMD,solvent=water) - Procedure: Using the optimized geometry from step 1 (you can use

geom=checkand read from the gas-phase checkpoint file), perform a single-point calculation in solution. - Example Input:

- Route:

- Result Calculation:

- The solvation free energy is calculated as: ΔGsolv = Esolv - E_gas.

- A negative value indicates favorable solvation.

Protocol 2: Setting Up an Excited State Calculation in Solution

Objective: To perform a vertical excitation energy calculation in solution using non-equilibrium solvation [32].

Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Ground State Equilibrium Solvation:

- Route:

#p CAM-B3LYP/6-31G(d) SCRF=(IEFPCM,solvent=acetonitrile) opt - Procedure: Optimize the ground state geometry in solution to achieve an equilibrium solvation structure.

- Route:

- Non-Equilibrium Excited State Calculation:

- Route:

#p CAM-B3LYP/6-31G(d) SCRF=(IEFPCM,solvent=acetonitrile,read) TD(NStates=5) - Input Section: After the route and molecular specification, include an additional SCRF input section (terminated by a blank line) to specify non-equilibrium conditions.

- Example Input:

NonEq=Solventtells the PCM to use the non-equilibrium formalism, where the fast electronic polarization of the solvent responds to the vertical excitation, but the slow orientational polarization remains fixed from the ground state.

- Route:

Solvent Model Selection Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the logical decision process for selecting an appropriate solvent model in Gaussian for different research scenarios.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Solvation Models and Keywords

The table below summarizes the key solvent models and related keywords available in Gaussian for computational chemistry studies.

| Model/Keyword | Type | Primary Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| SCRF=SMD [32] | Implicit | Recommended for ΔG solvation. Uses IEF-PCM with parameters optimized for solvation free energy. | Requires separate gas and solution phase calculations. |

| SCRF=PCM (IEF-PCM) [32] [1] | Implicit | Default implicit model. Treats solvent as a polarizable continuum. Good general-purpose choice. | Efficient for ground and excited states (equilibrium/non-equilibrium). |

| SCRF=CPCM [32] | Implicit | A conductor-like variant of PCM. | An alternative to IEF-PCM; performance may vary by system. |

| SCRF=Dipole (Onsager) [32] | Implicit | Uses a spherical cavity within the reaction field. | Less accurate than PCM for non-spherical molecules; simpler model. |

| ExternalIteration [32] | Method | Makes solvent reaction field self-consistent with the solute's electrostatic potential (e.g., MP2 density). | More accurate for properties like fluorescence; available for energy calculations. |

| NonEquilibrium [32] | Option | Specifies non-equilibrium solvation for vertical excitation energies. | Solvent electronic polarization responds, but orientational polarization does not. |

| SAS (SolventAccessibleSurface) [32] | Option | Uses a solvent-accessible surface cavity. | Suitable for single-point calculations on structures from MD simulations with explicit solvent. |

Advanced Solvation Workflow

For complex systems requiring a hybrid quantum-mechanical/molecular-mechanical (QM/MM) approach, the workflow often involves generating configurations with explicit solvent before applying an implicit model.

Core Concepts and Theoretical Foundation

The Generalized Born Surface Area (GB/SA) methodology is an implicit solvent model that provides a computationally efficient framework for biomolecular Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations by replacing explicit solvent molecules with a continuum representation. This approach significantly reduces the number of degrees of freedom in the system, enabling faster calculations and enhanced conformational sampling compared to explicit solvent simulations [34] [35].

The solvation free energy ((\Delta G{solv})), which quantifies the energy change associated with transferring a solute from a vacuum to a solvent, is central to the model. In GB/SA, this energy is typically decomposed into two main components [34] [36]: [ \Delta G{solv} = \Delta G{ele} + \Delta G{np} ]

- (\Delta G_{ele}) (Polar Component): This represents the electrostatic contribution to solvation. It is calculated using the Generalized Born (GB) equation, which approximates the solution to the Poisson-Boltzmann equation. The GB method efficiently computes the electrostatic interaction between the solute and the dielectric continuum [34] [35].

- (\Delta G{np}) (Non-Polar Component): This term accounts for the free energy cost of forming a cavity in the solvent for the solute to occupy, as well as van der Waals interactions between the solute and solvent. It is most commonly estimated as being proportional to the Solvent-Accessible Surface Area (SASA) [34] [35]: [ \Delta G{np} = \gamma \cdot SASA + b ] where (\gamma) is a surface tension parameter and (b) is a constant.

Table 1: Key Components of Solvation Free Energy in Implicit Solvent Models

| Component | Description | Physical Origin | Typical Calculation Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polar ((\Delta G_{ele})) | Electrostatic interaction with solvent | Polarization of solvent by solute charges | Generalized Born (GB) equation |

| Non-Polar ((\Delta G_{np})) | Cavity formation & van der Waals | Work to create a cavity; dispersion forces | Solvent-Accessible Surface Area (SASA) |

GB/SA Setup and Simulation Workflow

A typical workflow for setting up and running a GB/SA simulation involves several key steps, from initial structure preparation to production simulation and analysis. The following diagram illustrates this end-to-end process.

Diagram Title: GB/SA Simulation Workflow

Critical Configuration Steps

A successful GB/SA simulation depends on correct parameter settings in the molecular dynamics parameter (MDP) file.

- Implicit Solvent Selection: The key directive

implicit-solvent = GBmust be set to activate the Generalized Born model. - GB Model Variant: Specify the desired Generalized Born implementation, such as

gb-algorithm = Stillfor the Still model or other variants likeHCTorOBC. The choice of model affects the accuracy of the calculated Born radii. - Non-Polar Model: Activate the SASA-based non-polar contribution with

sa-algorithm = SASAand set the surface tension coefficient (sa-surface-tension) appropriately, often around 2.1 kJ/mol/nm². - Dielectric Constants: Define the solute (

coulomb-global-dielectric) and solvent (coulomb-slv-dielectric) dielectric constants. Typical values are ~1-4 for the solute (internal) and 78.5 for the solvent (water). - Electrostatics: Set

coulomb-type = Cut-offandrcoulombto a suitable value (e.g., 1.0-1.4 nm). Reaction-field electrostatics are not typically used with GB.

Troubleshooting Common Errors

Users often encounter specific errors when setting up GB/SA simulations. The table below outlines common issues and their solutions.

Table 2: Common GB/SA Setup Errors and Solutions

| Error / Issue | Likely Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| "Out of memory when allocating" [37] | System is too large for available RAM; incorrect box size. | Reduce system size; check that the simulation box is not mistakenly 1000x too large (e.g., using nm instead of Å). |

| "Residue 'XXX' not found in residue topology database" [37] | The force field does not contain parameters for the residue/molecule 'XXX'. | Ensure residue name matches the force field database. For novel molecules, a manual topology must be created. |

| "Long bonds and/or missing atoms" [37] | Atoms are missing from the initial structure file. | Check the pdb2gmx output for warnings about missing atoms. Use modeling software to add missing atoms before simulation. |

| Unstable simulation, system blows up | Incorrect parameters in the MDP file; insufficient energy minimization. | Double-check GB/SA MDP parameters (e.g., dielectric constants, algorithm names). Ensure the system is properly minimized before equilibration. |

| Poor binding affinity predictions | Inadequate conformational sampling; limitations of the SASA non-polar model. | Extend simulation time; use enhanced sampling techniques; consider hybrid explicit/implicit schemes or ML-enhanced models [38] [39]. |

Advanced Troubleshooting: Topology and Restraints

Problem: "Found a second defaults directive" or "Invalid order for directive" [37]

- Cause: The topology file (

*.top) includes multiple[ defaults ]sections or other directives in an incorrect order. This often happens when manually mixing force fields or including ligand topologies. - Solution: Ensure the

[ defaults ]directive appears only once, typically from the main force field. Reorder#includestatements so that all[ atomtypes ]and other[ *types ]directives are declared before any[ moleculetype ]sections.

- Cause: The topology file (

Problem: "Atom index n in position_restraints out of bounds" [37]

- Cause: Position restraint files are included in the topology for the wrong molecule or in the wrong order. The atom indices in a restraint file are relative to its own

[ moleculetype ]. - Solution: In the system topology, include the position restraints file (

posre.itp) immediately after the corresponding molecule's topology (topol_XXX.itp), not after all molecules have been defined.

- Cause: Position restraint files are included in the topology for the wrong molecule or in the wrong order. The atom indices in a restraint file are relative to its own

Machine Learning-Enhanced GB/SA Methods

Traditional GB/SA calculations, while efficient, can still be a bottleneck in high-throughput virtual screening. Recent advances leverage Machine Learning (ML) to create surrogate models that dramatically accelerate these calculations [39] [40].

- Surrogate MMGBSA (SurGBSA): This approach uses graph neural networks (GNNs) trained on thousands of MD trajectories to learn a function that predicts MMGBSA energies directly from 3D structures. This method has demonstrated a speedup of over 6,000x compared to traditional single-point MMGBSA calculations while maintaining comparable accuracy in pose ranking, making it ideal for rapid virtual screening [39].

- (\lambda)-Solvation Neural Network (LSNN): A limitation of many ML models trained only on forces ("force-matching") is that the energy is determined only up to an arbitrary constant, making them unsuitable for absolute free energy calculations. The LSNN model overcomes this by being trained to match not only forces but also derivatives with respect to alchemical coupling parameters ((\lambda)). This allows it to produce accurate solvation free energies comparable to explicit-solvent calculations [40].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Tools for GB/SA Simulations

| Tool / Reagent | Function / Purpose | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| GROMACS | A versatile MD simulation package. | Includes robust implementations of several GB models and SASA calculations for running production simulations [37]. |

| AMBER | Another widely used MD package. | Known for its sophisticated implicit solvent models, frequently used for MMGBSA binding free energy calculations. |

| Schrödinger Glide | Molecular docking and scoring software. | Often used for initial pose generation prior to more refined GB/SA-based scoring or MD simulation [38]. |

| Desmond | A high-performance MD simulator. | Used for running MD simulations with implicit solvent, as cited in recent methodological studies [38]. |

| GB Models (Still, HCT, OBC) | Different algorithmic variants for calculating the Born radii. | The choice of model affects the accuracy of the polar solvation term. Testing multiple models can be part of method validation. |

| Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) | Machine learning architecture for molecular representation. | Used in next-generation surrogate models like SurGBSA and LSNN to accelerate free energy calculations [39] [40]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: When should I choose a GB/SA model over an explicit solvent model for my simulation?

- A: GB/SA is ideal when computational efficiency and enhanced conformational sampling are priorities, such as in rapid screening of ligand binding poses, protein folding studies, or simulations of large systems. Explicit solvent should be used when specific solvent-solute interactions (e.g., water bridges, precise ion coordination) are critical to the research question [34] [35].

Q2: What are the main limitations of the standard GB/SA approach?

- A: Its main limitations include: a) The approximation of the non-polar term by a simple SASA model, which may not capture all physics; b) The difficulty in parameterizing the solute's internal dielectric constant; c) The inability to capture specific, directional solvent interactions like hydrogen bonds [34] [40].

Q3: How can I improve the accuracy of binding free energies calculated with MMGBSA?

- A: Best practices include: a) Using multiple, diverse protein conformations (ensemble docking) to account for flexibility [38]; b) Ensuring adequate sampling from MD simulations (e.g., ~100 ns may be sufficient for some systems [38]); c) Considering hybrid or multi-scale approaches that model the binding site at atomic resolution and the rest of the system at a coarse-grained level to save resources [38].

Q4: My simulation in implicit solvent is unstable. What should I check first?

- A: First, verify all parameters in your MDP file, especially that

implicit-solventandgb-algorithmare correctly set. Second, ensure your system was properly energy-minimized. Third, check for any missing atoms or steric clashes in your initial structure that could cause large, unstable forces [37].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: Why can't I use a standard, general-purpose force field for my simulations of deep eutectic solvents or ionic liquids?

Standard force fields are parameterized for a wide range of common chemicals but may fail to capture the specific intermolecular interactions crucial in specialized solvent environments like Deep Eutectic Solvents (DES) or ionic liquids. The balance between hydrophilic and hydrophobic interactions is particularly important for self-assembling systems, and a general force field may not include parameters for specific aromatic moieties or ions found in these solvents. A component-specific parametrization is often required to reproduce experimental properties such as partition free energies and self-assembly behavior accurately [41] [42] [43].

FAQ 2: How does my choice of atomic charge assignment method impact the outcome of my solvent simulations?

The choice of charge assignment method has a profound impact on the accuracy of molecular dynamics simulations, especially for polar solvents and ionic compounds. Different charge schemes (e.g., ChelpG, Mulliken, AIM) can produce significantly different atomic and total charges, even for the same optimized molecular geometry [43]. These differences directly affect the calculated electrostatic interactions, which are often dominant in solvent environments. This, in turn, influences the prediction of key macroscopic properties such as density, diffusion coefficients, and intermolecular structure. Using charges derived from quantum mechanical calculations on interacting ion-pair clusters, rather than on isolated ions, generally leads to more reliable results [43].

FAQ 3: What is the fundamental difference between a transferable and a component-specific force field?

- Transferable Force Field: Parameters are designed as building blocks that can be applied to a wide variety of substances. For example, a methyl group parameter set can be transferred across different organic molecules. This approach maximizes generality [41].

- Component-Specific Force Field: The force field is developed solely to describe a single, specific substance (e.g., a particular water model or a specific Deep Eutectic Solvent). This approach can achieve higher accuracy for that specific system but is not transferable to others [41].

FAQ 4: When should I consider using a polarizable force field instead of an additive one?

You should consider a polarizable force field when your system involves environments where electronic polarization is expected to play a significant role, but is not well-captured by fixed atomic charges. Additive force fields with fixed charges can fall short in simulating interfaces, membranes, or heterogeneous environments where the electronic distribution of a molecule changes substantially. Polarizable force fields explicitly model this response, improving accuracy for properties like multipole moments and dielectric constants [44].

Troubleshooting Guides