Unwrapping Coordinates for Correct Diffusion Calculation: Methods and Applications in Biomedical Research

Accurate analysis of diffusion processes is pivotal in biomedical research, from understanding single-molecule dynamics in cells to optimizing drug delivery systems.

Unwrapping Coordinates for Correct Diffusion Calculation: Methods and Applications in Biomedical Research

Abstract

Accurate analysis of diffusion processes is pivotal in biomedical research, from understanding single-molecule dynamics in cells to optimizing drug delivery systems. This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the critical preprocessing step of coordinate unwrapping and its impact on diffusion calculation fidelity. We explore the foundational principles of anomalous diffusion and the limitations of traditional analysis methods like Mean Squared Displacement (MSD). The article details modern computational and machine learning methodologies, including hybrid mass-transfer models and optimization algorithms, for robust coordinate processing. Furthermore, we present a comparative analysis of troubleshooting techniques and validation frameworks to optimize accuracy, synthesizing key takeaways to guide future research and clinical applications in computational pathology and drug development.

Understanding Anomalous Diffusion and the Critical Role of Coordinate Unwrapping

Anomalous diffusion describes a class of transport processes where the spread of particles occurs at a rate that fundamentally differs from the classical Brownian motion model. In normal diffusion, the mean squared displacement (MSD)—the average squared distance a particle travels over time—increases linearly with time (MSD ∠t). Anomalous diffusion, in contrast, is characterized by a non-linear, power-law scaling of the MSD, expressed as MSD ∠t^α, where the anomalous diffusion exponent α determines the regime of motion [1] [2]. This phenomenon is ubiquitously observed in complex systems across disciplines, from the transport of molecules in living cells [1] [3] and diffusion in porous media [1] to exotic phases in quantum systems [4].

Accurately characterizing these processes is paramount in research, particularly when calculating diffusion coefficients from particle trajectories. A critical step in this analysis, especially for molecular dynamics simulations in the NPT ensemble (constant pressure), involves the correct "unwrapping" of particle coordinates from the periodic simulation box to reconstruct their true path in continuous space. Inconsistent unwrapping can artificially alter displacement measurements, leading to significant errors in the determined diffusion coefficient and potentially misclassifying the diffusion regime [5]. This protocol provides a framework for defining, identifying, and quantifying anomalous diffusion, with special consideration for ensuring accurate trajectory analysis.

Defining the Diffusion Regimes

The primary quantitative measure for classifying diffusion is the anomalous diffusion exponent, α, derived from the time-dependent mean squared displacement.

Mean Squared Displacement (MSD): ⟨r²(τ)⟩ = 2dDτ^α ...where d is the dimensionality, D is the generalized diffusion coefficient, and τ is the time lag [1].

Table 1: Classification of Diffusion Regimes Based on the Anomalous Diffusion Exponent (α)

| Regime | Exponent (α) | MSD Scaling | Physical Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Subdiffusion | 0 < α < 1 | ⟨r²⟩ ∠τ^α | Particle motion is hindered by obstacles, binding, or crowding. |

| Normal Diffusion | α = 1 | ⟨r²⟩ ∠τ | Standard Brownian motion in a homogeneous medium. |

| Superdiffusion | 1 < α < 2 | ⟨r²⟩ ∠τ^α | Motion is persistent and directed, often active. |

| Ballistic Motion | α = 2 | ⟨r²⟩ ∠τ² | Particle moves with constant velocity, as in free flight. |

The value of α is not merely a numerical descriptor; it is intimately linked to the underlying physical mechanism of the transport process. Subdiffusion often arises in crowded environments like the cell cytoplasm or porous materials, where obstacles and binding events trap particles [1] [2]. Superdiffusion, conversely, can result from active transport processes, such as those driven by molecular motors, or from Levy flights, where particles occasionally take very long steps [1] [6]. The potential for analysis artifacts, such as those introduced by erroneous trajectory unwrapping in simulations, underscores the need for rigorous methodology [5].

Theoretical Models and Mathematical Frameworks

Several stochastic models have been developed to describe the microscopic mechanisms that give rise to anomalous diffusion. Selecting the appropriate model is essential for correct physical interpretation.

Table 2: Key Theoretical Models of Anomalous Diffusion

| Model | Key Mechanism | Typical Exponent α | Example Systems |

|---|---|---|---|

| Continuous-Time Random Walk (CTRW) | Power-law distributed waiting times between jumps. | 0 < α < 1 (Subdiffusion) | Transport in disordered solids [2]. |

| Fractional Brownian Motion (FBM) | Long-range correlations in the noise driving the motion. | 0 < α < 2 (Sub- or Superdiffusion) | Telomere motion in the cell nucleus [1] [3]. |

| Lévy Walk | Power-law distributed step lengths with a finite velocity. | 1 < α < 2 (Superdiffusion) | Animal foraging patterns [7]. |

| Scaled Brownian Motion (SBM) | Time-dependent diffusion coefficient, D(t) ∠t^(α-1). | 0 < α < 2 (Sub- or Superdiffusion) | Diffusion in turbulent media [8]. |

The mathematics of anomalous diffusion is frequently formulated using fractional calculus. The standard diffusion equation, ∂u(x, t)/∂t = D ∂²u(x, t)/∂x², is replaced by fractional diffusion equations. The time-fractional diffusion equation incorporates memory effects and is used to model subdiffusion: ∂^α u(x, t)/∂t^α = D_α ∂²u(x, t)/∂x², where ∂^α/∂t^α is the Caputo fractional derivative [2]. This equation can be derived from the CTRW model with power-law waiting times [2]. For more complex scenarios where the MSD does not follow a pure power-law, generalized equations like the g-subdiffusion equation can be employed, which uses a fractional Caputo derivative with respect to a function g(t) to match an empirically determined MSD profile [9].

Experimental Protocols and Data Analysis

Protocol 1: Inferring the Anomalous Diffusion Exponent from Single Trajectories

Application Note: This protocol is designed for the analysis of single-particle tracking (SPT) data, commonly generated in biophysics to study the motion of molecules, vesicles, or pathogens in live cells [7] [3].

Trajectory Acquisition:

- Input: A video or image stack from single-molecule microscopy.

- Procedure: Use localization algorithms (e.g., Gaussian fitting) to determine the precise (x, y[, z]) coordinates of the particle in each frame. Link localizations across frames to reconstruct the trajectory.

- Output: A single-particle trajectory, T = {xâ‚, yâ‚, tâ‚; xâ‚‚, yâ‚‚, tâ‚‚; ... ; x_N_, *y_N_, *t*N}.

Trajectory Preprocessing (Critical for Simulations):

- Unwrapping Coordinates: For trajectories obtained from molecular dynamics (MD) simulations in the NPT ensemble, apply a consistent unwrapping algorithm to prevent artifacts in displacement calculations.

- Recommended Method: The Toroidal-View-Preserving (TOR) scheme is advised over heuristic lattice-view schemes, as it preserves the dynamics of the wrapped trajectory and yields more accurate diffusion coefficients [5]. The 1D TOR scheme is defined as: u{i+1} = *u_i + [ w{i+1} - *w_i ]PBC, where *u* is the unwrapped coordinate, *w* is the wrapped coordinate, and []PBC denotes the minimal displacement accounting for periodic boundary conditions [5].

MSD Calculation:

- Procedure: Calculate the time-averaged MSD (TAMSD) for the single trajectory.

- Formula: δτ = 1/(T - τ) ∫₀^(T-τ) [ r(t + τ) - r(t) ]² dt, where τ is the time lag and T is the total trajectory length [8].

- Output: A curve of δτ vs. τ.

Exponent Fitting:

- Procedure: Fit the TAMSD curve to the power-law model, ⟨r²(τ)⟩ = K_α τ^α.

- Method: Perform a linear regression on the log-transformed data: log(⟨r²(τ)⟩) ≈ log(K_α) + α log(τ). The slope provides the estimate for α.

- Caution: Be aware of the limitations of MSD-based analysis, such as sensitivity to noise and trajectory length [7]. For short or complex trajectories, machine learning methods have demonstrated superior performance [7] [3].

Protocol 2: Segmenting a Trajectory with Changepoints in Diffusion Behavior

Application Note: Biomolecules often undergo changes in diffusion behavior due to interactions, binding, or confinement. This protocol outlines how to identify the points in a trajectory where the anomalous exponent α or the diffusion model changes [3].

Input: A single-particle trajectory suspected of containing heterogeneous dynamics.

Method Selection:

- Options: Choose from a variety of changepoint detection algorithms. Recent community benchmarks (e.g., the AnDi Challenges) indicate that machine-learning-based methods generally outperform traditional statistical tests for this task [7] [3].

- Examples: Methods based on hidden Markov models, neural networks, or likelihood ratio tests can be used [3].

Analysis Execution:

- Procedure: Apply the selected algorithm to the trajectory. The algorithm will scan the time series of particle displacements or positions to identify points where the statistical properties of the motion change significantly.

- Output: A list of inferred changepoint times, t_CP, and the estimated diffusion parameters (e.g., α, D) for each segment between changepoints.

Validation:

- Procedure: Independently analyze each segmented trajectory using the methods in Protocol 1 to verify the homogeneity of the diffusion parameters within the segment.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational and Analytical Tools

| Tool / Resource | Function / Description | Relevance to Anomalous Diffusion Research |

|---|---|---|

| AnDi Datasets Python Package | A library to generate simulated trajectories of anomalous diffusion with known ground truth [3]. | Benchmarking and training new analysis algorithms; testing the performance of inference methods under controlled conditions. |

| Machine Learning Classifiers | Algorithms (e.g., Random Forests, Neural Networks) trained to identify the diffusion model and exponent from trajectory data [7]. | Provides high-accuracy classification and inference, especially for short or noisy trajectories where traditional MSD analysis fails. |

| Toroidal-View-Preserving (TOR) Unwrapping | An algorithm for correctly reconstructing continuous particle paths from NPT MD simulations with fluctuating box sizes [5]. | Prevents artifacts in displacement calculations, ensuring accurate determination of MSD and diffusion coefficients from simulation data. |

| Fractional Diffusion Equation Solvers | Numerical codes to solve fractional partial differential equations like the time-fractional diffusion equation. | Enables theoretical modeling and prediction of particle spread in complex, anomalous environments for comparison with experiments. |

| Lasofoxifene | Lasofoxifene|Selective Estrogen Receptor Modulator | Lasofoxifene is a potent, 3rd-generation SERM for osteoporosis and breast cancer research. This product is for research use only (RUO) and not for human consumption. |

| 2-Ketoglutaric acid-13C | 2-Ketoglutaric acid-13C, CAS:108395-15-9, MF:C5H6O5, MW:147.09 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

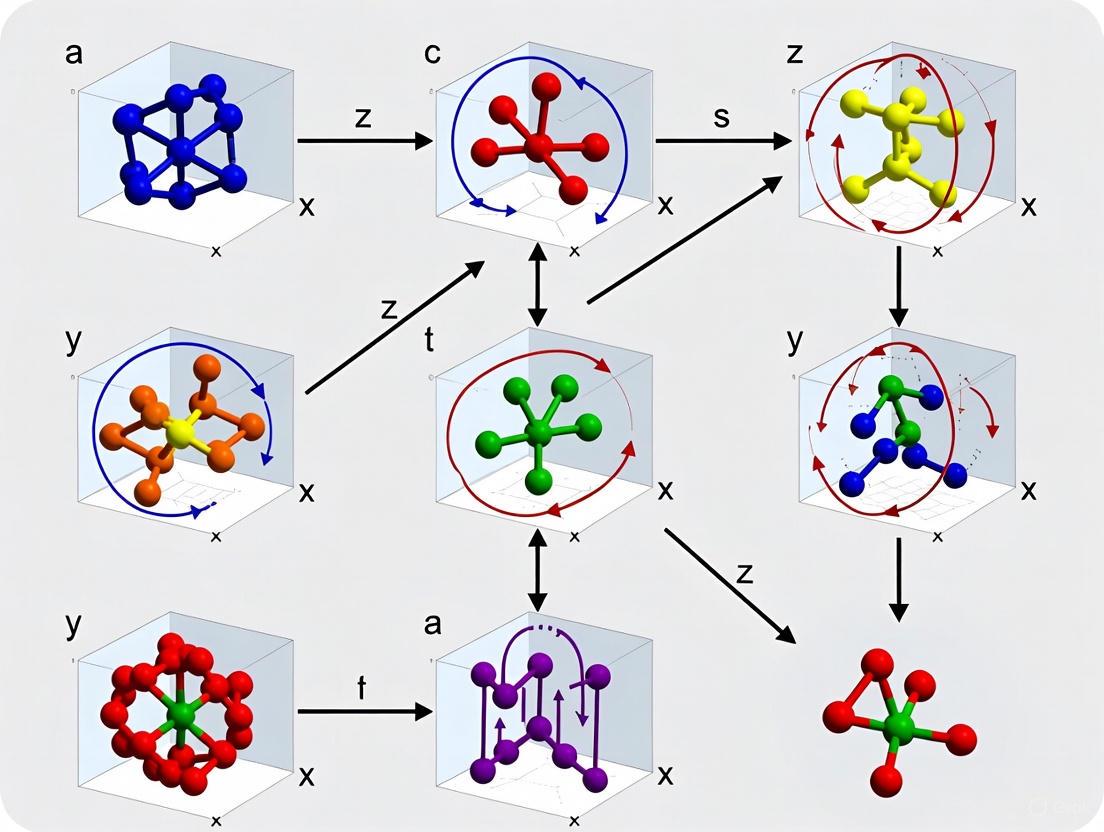

Decision Framework for Unwrapping and Model Selection

Choosing the correct analytical pathway is crucial for reliable results. The following diagram outlines a decision process based on the data source and research question.

The Pitfalls of Traditional Mean Squared Displacement (MSD) Analysis

Mean Squared Displacement (MSD) analysis stands as a cornerstone technique in single-particle tracking (SPT) studies across biological, chemical, and physical sciences. However, traditional MSD methodologies present significant limitations that can compromise the accuracy and interpretation of diffusion data, particularly in complex systems. This application note details the inherent pitfalls of conventional MSD analysis, with a specific focus on the critical importance of proper trajectory unwrapping for calculating accurate diffusion coefficients. We provide validated experimental protocols and analytical frameworks to overcome these challenges, enabling researchers to extract more reliable and meaningful parameters from their single-particle trajectory data.

Single-particle tracking enables the observation of individual molecules, organelles, or particles at high spatial and temporal resolution, typically at the nanometer and millisecond scale [10]. The technique involves reconstructing particle trajectories from time-lapse imaging data, with trajectory analysis serving as the crucial final step for extracting meaningful parameters about particle behavior and the underlying driving mechanisms [10].

Mean Squared Displacement (MSD) analysis represents the most common approach in SPT studies, quantifying the average squared distance a particle travels over specific time intervals [10]. The MSD function is calculated as: [MSD(\tau = n\Delta t) \equiv \frac{1}{N-n}\sum_{j=1}^{N-n}|X(j\Delta t + \tau) - X(j\Delta t)|^2] where (X(\tau)) represents the particle trajectory sampled at times (\Delta t, 2\Delta t, \ldots N\Delta t), and (\langle \cdot \rangle) denotes the Euclidean distance [10].

The MSD trend versus time lag ((\tau)) traditionally classifies motion types: linear for Brownian diffusion, quadratic for directed motion with drift, and asymptotic for confined motion [10]. For anomalous diffusion, MSD is often fitted to the general law (MSD(\tau) = 2\nu D_\alpha \tau^\alpha), where (\alpha) represents the anomalous exponent [10].

Despite its widespread use, MSD analysis faces fundamental challenges including measurement uncertainties, short trajectories, and population heterogeneities. These limitations become particularly problematic when studying anomalous motion in complex environments like intracellular spaces or crowded materials [10].

Critical Pitfalls in Traditional MSD Analysis

Technical and Methodological Limitations

Traditional MSD analysis suffers from several technical shortcomings that can significantly impact data interpretation:

Short Trajectory Limitations: For molecular labeling with organic dyes subject to photobleaching, trajectories are often relatively short, allowing reconstruction of only the initial MSD curve portion. This makes capturing the true motion nature from MSD fits difficult [10].

Localization Uncertainty Effects: Measurement precision limitations and localization uncertainties directly impact MSD calculation accuracy, particularly at short time scales where these effects can dominate true particle displacement [10].

Insufficient Temporal Resolution: The MSD analysis requires at least two orders of magnitude for time lags to precisely determine scaling exponents when motion type remains constant within a trajectory. Many practical applications fall short of this requirement [10].

State Transition Blindness: MSD analysis often fails to detect multiple states within single trajectories. More advanced approaches have revealed state transitions that remain undetectable in conventional MSD analysis, leading to oversimplified interpretation of particle behavior [10].

The Trajectory Unwrapping Problem for Diffusion Calculations

A particularly critical yet often overlooked pitfall in MSD analysis emerges when calculating diffusion coefficients from molecular dynamics simulations, especially in constant-pressure (NPT) ensembles. In simulations with periodic boundary conditions, particle trajectories can be represented as either "wrapped" (confined to the central simulation box) or "unwrapped" (traversing full three-dimensional space) [5].

In NPT simulations, the simulation box size and shape fluctuate over time as the barostat maintains constant pressure. When particle trajectories are unwrapped using inappropriate schemes, the barostat-induced rescaling of particle positions creates unbounded displacements that artificially inflate diffusion coefficient measurements [5] [11].

Table 1: Comparison of Trajectory Unwrapping Schemes for NPT Simulations

| Unwrapping Scheme | Fundamental Approach | Key Advantages | Critical Limitations | Suitability for Diffusion Calculation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heuristic Lattice-View (HLAT) | Selects lattice image minimizing displacement between frames [5] | Intuitively appealing; implemented in common software packages (GROMACS, Ambertools) [5] | Frequently unwraps particles into wrong boxes in constant-pressure simulations, creating artificial particle acceleration [5] | Poor - produces significantly inaccurate diffusion coefficients |

| Modern Lattice-View (LAT) | Tracks integer image numbers to maintain lattice consistency [5] | Preserves underlying lattice structure; implemented in LAMMPS and qwrap software [5] | Generates unwrapped trajectories with exaggerated fluctuations that distort dynamics [5] | Compromised - overestimates diffusion coefficients |

| Toroidal-View-Preserving (TOR) | Sums minimal displacement vectors within simulation box [5] | Preserves statistical properties of wrapped trajectory; maintains correct dynamics [5] | Requires molecules to be made "whole" before unwrapping to prevent bond stretching [5] | Excellent - recommended for accurate diffusion coefficients |

The TOR scheme, which sums minimal displacement vectors within the simulation box, preserves the wrapped trajectory's statistical properties and provides the most reliable foundation for subsequent MSD analysis and diffusion coefficient calculation [5].

Advanced and Complementary Analytical Approaches

To overcome traditional MSD limitations, researchers have developed several complementary analytical methods that provide enhanced sensitivity for detecting heterogeneities and transient behaviors:

Distribution-Based Analyses: Methods examining parameter distributions beyond displacements—including angles, velocities, and times—demonstrate superior sensitivity in characterizing heterogeneities and rare transport mechanisms often masked in ensemble MSD analysis [10].

Hidden Markov Models (HMMs): These approaches identify different motion states within trajectories, quantifying their populations and switching kinetics. HMMs can reveal state transitions completely undetectable through conventional MSD analysis [10].

Machine Learning Classification: Algorithms ranging from random forests to deep neural networks now successfully classify trajectory motions. These model-free approaches can extract valuable information even from short, noisy trajectories that challenge traditional MSD methods [10].

Integration of classical statistical approaches with machine learning methods represents a particularly promising pathway for obtaining maximally informative and accurate results from single-particle trajectory data [10].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Correct Trajectory Unwrapping for NPT Simulations

Purpose: To generate accurate unwrapped trajectories from constant-pressure MD simulations for reliable MSD analysis and diffusion coefficient calculation.

Materials:

- Molecular dynamics simulation trajectory files (NPT ensemble)

- Visualization/analysis software (e.g., LAMMPS, GROMACS, Ambertools)

- Custom scripts implementing TOR unwrapping scheme

Procedure:

- Simulation Preparation: Conduct NPT ensemble MD simulations with appropriate barostat settings and periodic boundary conditions. Ensure trajectory saving frequency captures all relevant particle motions [5].

- Molecular Integrity Check: For multi-atom molecules, ensure all molecules are made "whole" before unwrapping to prevent unphysical bond stretching. Apply molecular reconstruction algorithms if necessary [5].

- TOR Unwrapping Implementation: Apply the toroidal-view-preserving unwrapping scheme using either:

- Custom implementation of the TOR algorithm: (u{i+1} = ui + \left[w{i+1} - wi - L{i+1}\text{round}\left(\frac{w{i+1} - wi}{L{i+1}}\right)\right]) [5]

- Specialized software packages implementing TOR-compliant unwrapping

- Trajectory Validation: Verify that unwrapped trajectories maintain consistent dynamics with original wrapped trajectories through velocity autocorrelation analysis [5].

- MSD Calculation: Compute MSD from properly unwrapped trajectories using standard algorithms.

- Diffusion Coefficient Extraction: Fit MSD curve to appropriate model for diffusion coefficient calculation: (D = \lim_{t \to \infty} \frac{\langle [u(t) - u(0)]^2 \rangle}{2t}) for Brownian motion [5].

Protocol 2: Machine Learning-Enhanced Trajectory Classification

Purpose: To implement machine learning approaches for detecting heterogeneous motion states in single-particle trajectories.

Materials:

- Single-particle trajectory data set

- Programming environment (Python, R, or MATLAB)

- Machine learning libraries (scikit-learn, TensorFlow, PyTorch)

- Feature extraction utilities

Procedure:

- Feature Extraction: Calculate multiple descriptive features from each trajectory, including:

- MSD-derived parameters (diffusion coefficient, anomalous exponent)

- Angular distributions within tracks

- Velocity autocorrelations

- Moment scaling spectrum [10]

- Training Data Preparation: Generate simulated trajectories with known motion types (Brownian, confined, directed) or use experimentally validated labeled data [10].

- Model Selection & Training:

- For limited training data: Implement Random Forest or Support Vector Machines

- For large datasets: Develop Deep Neural Networks with appropriate architecture

- Apply cross-validation to optimize hyperparameters [10]

- Model Validation: Test classifier performance on holdout datasets with known ground truth.

- Experimental Application: Apply trained model to classify experimental trajectories.

- State Transition Analysis: Implement Hidden Markov Models to identify states with different diffusivities and characterize switching kinetics [10].

Visualization of Analytical Workflows

Workflow for Robust Diffusion Analysis

MSD Analysis Pitfalls and Solutions

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Single-Particle Tracking Studies

| Reagent/Platform | Function/Application | Key Features/Benefits | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electrochemiluminescence (MSD) [12] | Protein quantitation and biomarker detection in drug development | Wider dynamic range, higher sensitivity, lower sample volume requirements, reduced matrix interference compared to ELISA [12] | Higher upfront costs but superior performance for multiplexed protein analysis [13] |

| High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry [13] | Biomarker discovery and large molecule drug quantitation | Unmatched sensitivity, specificity, and molecular insight; enables comprehensive biomarker identification [13] | Extended method development time; complex sample preparation; significant instrumentation investment [13] |

| Triple Quadrupole MS [13] | Targeted quantitation of identified biomarkers or drug analytes | Ideal for tracking large molecule drugs in complex biological matrices via multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) [13] | Requires prior biomarker identification; excellent for targeted analysis once discovery phase complete [13] |

| Hidden Markov Model Software [10] | Identification of different motion states within single trajectories | Characterizes state populations and switching kinetics; reveals transitions undetectable by MSD analysis [10] | Requires careful definition of states and selection of appropriate state numbers; computational complexity varies |

| Machine Learning Libraries [10] | Model-free trajectory classification and feature detection | Can extract valuable information from short, noisy trajectories; handles complex, heterogeneous motion patterns [10] | Training data requirements; computational resources; model interpretability challenges |

| Diiodoacetic acid | Diiodoacetic Acid (DIAA) | High-purity Diiodoacetic Acid for research. Study genotoxic disinfection byproducts (DBPs) and alkylating agent mechanisms. For Research Use Only. Not for human consumption. | Bench Chemicals |

| Rocepafant | Rocepafant, CAS:132418-36-1, MF:C26H23ClN6OS2, MW:535.1 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Why Coordinate Integrity is Fundamental for Accurate Diffusion Exponent (α) Inference

The accurate inference of the anomalous diffusion exponent (α) from single-particle trajectories is a cornerstone for understanding transport phenomena in complex systems, from biological cells to synthetic materials. This exponent, defined by the scaling relationship of the mean squared displacement (MSD ∠tα), is crucial for classifying diffusion as subdiffusive (α < 1), normal (α = 1), or superdiffusive (α > 1) [14] [7]. However, a frequently overlooked prerequisite for accurate α estimation is coordinate integrity—the correct reconstruction of a particle's true path in continuous space from data subject to periodic boundary conditions (PBCs) and experimental constraints. Flawed coordinate reconstruction systematically biases displacement calculations, leading to incorrect α estimation and potentially erroneous scientific conclusions. This Application Note details the sources of coordinate corruption, provides validated protocols for trajectory unwrapping, and establishes best practices for ensuring the integrity of diffusion analysis.

The Critical Link Between Unwrapping and Alpha Inference

In molecular dynamics (MD) and single-particle tracking (SPT) simulations, PBCs are used to simulate a bulk environment with a limited number of particles. This results in "wrapped" trajectories, where a particle that moves beyond the simulation box's edge reappears on the opposite side. To analyze the true, long-range diffusion of a particle, these trajectories must be "unwrapped" to restore the continuous path. The choice of unwrapping algorithm is not merely a technicality; it directly impacts the statistical properties of the resulting trajectory and all derived parameters, most critically the MSD and the inferred α exponent [5].

The Perils of Inconsistent Unwrapping in NPT Ensembles

The problem is particularly acute in the isothermal-isobaric (NPT) ensemble, commonly used to simulate biological systems at constant pressure. Here, the simulation box size and shape fluctuate. A naive unwrapping algorithm that simply accounts for box crossings without considering box rescaling can introduce unbounded, artificial displacements that do not correspond to real particle motion.

As highlighted in a 2023 review, the commonly used Heuristic Lattice-View (HLAT) scheme, implemented in some popular software, can "occasionally unwraps particles into the wrong box, which results in an artificial speed up of the particles" [5]. This artificial acceleration directly inflates the MSD and leads to a systematic overestimation of the α exponent, potentially misclassifying a subdiffusive process as normal or even superdiffusive. This makes coordinate integrity not just a preprocessing step, but a fundamental determinant of measurement validity.

Established Protocols for Robust Trajectory Unwrapping

To preserve coordinate integrity, the use of unwrapping schemes that are consistent with the statistical mechanics of the simulation ensemble is essential. The following protocols are recommended for accurate diffusion exponent inference.

Protocol 1: Unwrapping for Constant-Pressure (NPT) Simulations

This protocol is designed for trajectories generated in the NPT ensemble, where box fluctuations necessitate a toroidal view of PBCs.

- Principle: The Toroidal-View-Preserving (TOR) scheme constructs an unwrapped trajectory by summing the minimal displacement vectors between consecutive frames within the simulation box [5]. This method preserves the dynamics of the wrapped trajectory and is robust against box fluctuations.

- Procedure:

- Input: A wrapped trajectory

w_i(particle position in the central box at each time stepi) and the corresponding box vectorsL_i. - Calculation: For each time step, compute the unwrapped position

u_{i+1}using the recurrence relation:u_{i+1} = u_i + [w_{i+1} - w_i]Here, the quantity in square brackets represents the minimal image displacement between timeiandi+1. - Output: A continuous, unwrapped trajectory

u_isuitable for MSD calculation.

- Input: A wrapped trajectory

- Critical Consideration: The TOR scheme should be applied only to the center of mass of a molecule or a single reference atom. Applying it independently to all atoms of a molecule can cause unphysical bond stretching if the molecule crosses a periodic boundary [5]. Always ensure molecules are made "whole" prior to unwrapping.

Protocol 2: Unwrapping for Constant-Volume (NVT/NVE) Simulations

For simulations where the box volume is fixed, a lattice-based approach is valid and often simpler to implement.

- Principle: The Modern Lattice-View (LAT) scheme keeps track of the number of times a particle has crossed each periodic boundary via integer image flags [5].

- Procedure:

- Input: A wrapped trajectory

w_iand the (constant) box lengthL. - Image Tracking: Use software utilities (e.g., LAMMPS's

remaporqwrap) to compute the image numbern_ifor each frame. - Calculation: The unwrapped coordinate is calculated as:

u_i = w_i + n_i * L - Output: A continuous, unwrapped trajectory

u_i.

- Input: A wrapped trajectory

Protocol 3: Fitting the MSD with Optimal Parameters

After obtaining a correctly unwrapped trajectory, the MSD must be fitted with parameters that balance precision and bias.

- Principle: The precision of the α exponent estimated from a single trajectory depends heavily on the trajectory length (

L) and the maximum time lag (τ_M) used in the MSD fit [15]. Using too short a trajectory or too large aτ_Mintroduces significant variance and systematic bias. - Procedure:

- Calculate the time-averaged MSD (TA-MSD) for the unwrapped trajectory.

- Perform a linear fit of

log(TA-MSD(τ))againstlog(τ)for a range of time lagsτ = 1, 2, ..., τ_M. - The slope of this line provides the estimate for the anomalous diffusion exponent

α.

- Optimization Guidance: Based on simulations of fractional Brownian motion, the table below provides the optimal

τ_Mfor a given trajectory lengthLto achieve a precision where >60% of estimates fall withinα ± 0.1[15].

Table 1: Guidelines for optimal maximum time lag (Ï„_M) selection in MSD fitting.

| Trajectory Length (L) | Recommended τ_M | Expected Precision (Φ) |

|---|---|---|

| 100 points | 10 | ~60% |

| 500 points | 30 | ~63% |

| 1000 points | 50 | ~63% |

Table 2: Key software tools and algorithms for maintaining coordinate integrity and analyzing diffusion.

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| TOR Unwrapping | Algorithm | Unwraps trajectories from NPT simulations. | Preserves dynamics; use on center of mass only. |

| LAT Unwrapping | Algorithm | Unwraps trajectories from NVT/NVE simulations. | Relies on accurate image tracking. |

| GROMACS (trjconv) | Software | MD simulation and analysis. | Default unwrapping may use heuristic (HLAT) scheme; verify method. |

| LAMMPS | Software | MD simulation. | Uses modern LAT scheme for unwrapped coordinates. |

| Andi-datasets | Software | Generates benchmark trajectories for testing. | Essential for validating analysis pipelines [3]. |

| Time-averaged MSD | Algorithm | Estimates diffusion exponent from a single trajectory. | Highly sensitive to trajectory length and fitting parameters [15]. |

Integrated Workflow for Accurate Diffusion Analysis

The following diagram illustrates the critical decision points and steps in a workflow designed to preserve coordinate integrity from data acquisition to exponent inference.

Diagram 1: Workflow for robust diffusion exponent inference.

Coordinate integrity is a non-negotiable foundation for the accurate inference of diffusion exponents. The use of inappropriate trajectory unwrapping schemes, particularly under constant-pressure conditions, is a significant source of systematic error that can invalidate experimental and simulation conclusions. By adopting the TOR and LAT unwrapping protocols detailed herein, and by following rigorous MSD fitting practices that account for trajectory length, researchers can ensure their reported α values truly reflect the underlying physics of the system under study. As diffusion analysis continues to be a vital tool across scientific disciplines, a disciplined focus on the integrity of the primary coordinate data will be essential for generating reliable and reproducible knowledge.

Within the broader scope of research on unwrapping coordinates for correct diffusion calculation, addressing the inherent technical challenges of noise, short trajectories, and non-ergodic processes is paramount. These phenomena collectively impede the accurate quantification of molecular and water diffusion, directly affecting the interpretation of underlying tissue microstructure and biomolecular dynamics. Noise introduces uncertainty and bias, short trajectories limit parameter estimation, and non-ergodic processes violate the fundamental assumption that time and ensemble averages are equivalent. This application note details standardized protocols and analytical frameworks to mitigate these challenges, enabling more reliable diffusion calculations for researchers and drug development professionals.

Theoretical Foundations and Quantitative Data

Characterizing the Core Challenges

The accurate measurement of diffusion is foundational to numerous fields, from studying membrane protein dynamics in drug discovery to mapping neural pathways in the brain. However, three interconnected challenges consistently complicate data acquisition and analysis.

- Noise fundamentally limits the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) in diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) and introduces localization error in single-particle tracking (SPT). In magnitude DWI, noise follows a Rician distribution, which not only increases variance but also introduces a positive bias in signal measurements known as the "noise floor," leading to systematic errors in derived diffusion metrics [16] [17].

- Short Trajectories are an unavoidable consequence of photobleaching and the shallow depth of field in SPT experiments, particularly when tracking fast-diffusing targets in mammalian cells. Mean trajectory lengths can be as short as 3–4 frames, severely limiting the ability to infer accurate diffusion coefficients from any single trajectory [18].

- Non-Ergodic Processes occur when the time-averaged mean square displacement (MSD) of a single particle differs from the ensemble-averaged MSD across many particles. This ergodicity breaking is a hallmark of certain anomalous diffusion processes, such as continuous-time random walks (CTRW) regulated by transient binding to cellular structures like the actin cytoskeleton. In such cases, standard ensemble-averaging analysis fails [19].

Quantitative Impact on Diffusion Metrics

Table 1: Quantitative Impact of Noise and Short Trajectories on Diffusion Metrics

| Challenge | Experimental Manifestation | Impact on Diffusion Metric | Reported Performance Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Noise Floor in dMRI [16] | Elevated baseline in low-SNR signals | Bias in estimated diffusion signals | Increased uncertainty and reduced dynamic range |

| Localization Error in sptPALM [18] | Error in position estimate due to low photons and motion blur | Overestimation of diffusion coefficient from MSD | Highly error-prone when variance of localization error is unknown |

| Short Trajectories in SPT [18] | Trajectories of 3-4 frames due to defocalization | High variability in MSD; inability to resolve multiple states | Mean trajectory length as low as 3-4 frames, severely limiting inference |

| Non-Ergodic Diffusion [19] | Time-averaged MSD ≠ensemble-averaged MSD | Invalidates standard ensemble-based analysis | Requires single-trajectory analysis (e.g., for CTRW with actin binding) |

Table 2: Common Anomalous Diffusion Models and Their Properties

| Model | Mechanism | Ergodicity | Propagator | Example Biological Cause |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Continuous-Time Random Walk (CTRW) | Trapping with heavy-tailed waiting times | Non-ergodic | Non-Gaussian | Transient binding to actin cytoskeleton [19] |

| Diffusion on a Fractal | Obstacles creating a labyrinthine path | Ergodic | Non-Gaussian | Macromolecular crowding [19] |

| Fractional Brownian Motion (FBM) | Long-time correlations in noise | Ergodic | Gaussian | Viscoelastic cytoplasmic environment |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Denoising Diffusion-Weighted MRI Data

Principle: Improve SNR by exploiting data redundancy in the spatial and angular domains while preserving the integrity of the diffusion signal [16] [17].

Materials:

- Diffusion-weighted MRI dataset (e.g., multi-shell HARDI).

- Computing software (e.g., ExploreDTI [20], MRtrix3's

dwidenoise[21]).

Procedure:

- Signal Drift Correction: Correct for adverse signal alterations caused by scanner imperfections using a quadratic fit. This step must be performed before sorting b-values. [20]

- Sort B-Values: Organize the diffusion volumes so all b=0 s/mm² images are at the beginning of the dataset. [20]

- Gibbs Ringing Correction: Apply a correction algorithm (e.g., total variation) to remove artifacts appearing as fine parallel lines due to the truncation of Fourier transforms. [20]

- Denoising: Apply a denoising algorithm such as:

- MP-PCA: A patch-based method that uses Marchenko-Pastur theory to distinguish signal from noise components. This is widely used and reduces noise-related variance [16] [21] [17].

- LKPCA-NLM: A more recent method combining local kernel PCA (to exploit nonlinear diffusion redundancy) with non-local means filtering (to exploit spatial similarity), showing superior performance in preserving structural information [17].

- Validation: Evaluate denoising efficacy by comparing the SNR, reduction in noise floor bias, and preservation of spatial resolution against a gold standard if available (e.g., a complex average of multiple repeats) [16].

Protocol 2: Recovering State Mixtures from Short SPT Trajectories

Principle: Infer distributions of dynamic parameters (e.g., diffusion coefficients) from short, fragmented SPT trajectories while accounting for localization error and defocalization biases [18].

Materials:

- SPT dataset with trajectory coordinates.

- Software for SPT analysis (e.g.,

sasptPython package [18]).

Procedure:

- Trajectory Preprocessing: Compile individual particle tracks from raw localization data. Do not pre-filter based on trajectory length, as this biases the population towards slow-moving particles [18].

- Model Selection: Choose a Bayesian non-parametric method robust to short trajectories and unknown state numbers:

- State Array (SA): This method, implemented in the

sasptpackage, uses a finite state approximation to infer the distribution of diffusion coefficients and state occupations. It is particularly robust to variable localization error [18]. - Dirichlet Process Mixture Model (DPMM): A fully non-parametric alternative. However, SA generally outperforms DPMM in the presence of realistic experimental noise [18].

- State Array (SA): This method, implemented in the

- Fitting and Analysis: Fit the chosen model to the entire ensemble of jumps from all trajectories. The model inherently accounts for defocalization (the biased sampling of fast-diffusing particles) and localization error.

- Validation: On novel datasets, compare the recovered state occupations and diffusion coefficients against known standards or use synthetic data with ground truth to validate accuracy.

Protocol 3: Identifying Non-Ergodic Processes in Single-Particle Trajectories

Principle: Determine whether a system is ergodic by comparing time-averaged and ensemble-averaged metrics, and identify the appropriate anomalous diffusion model [19].

Materials:

- Long-duration, high-time-resolution SPT trajectories.

- Computing environment (e.g., MATLAB, Python) for trajectory analysis.

Procedure:

- Ensemble-Averaged MSD (EA-MSD): Calculate the standard MSD by averaging squared displacements over all particles for each time lag.

- Time-Averaged MSD (TA-MSD): For each individual trajectory ( i ), calculate its time-averaged MSD: ( \overline{\delta^2(\Delta)}i = \frac{1}{T-\Delta} \int0^{T-\Delta} [\vec{r}(t+\Delta) - \vec{r}(t)]^2 dt ) where ( T ) is the total measurement time and ( \Delta ) is the time lag.

- Ergodicity Breaking Test: Plot the EA-MSD and the distribution of TA-MSDs. In a non-ergodic process like CTRW, the EA-MSD will follow a sublinear power law (( \propto \Delta^\alpha )), while the TA-MSDs will be linearly scattered and dependent on the measurement time ( T ) [19].

- Model Discrimination:

- Analyze the cumulative distribution function (CDF) of displacements. A biexponential fit with a weight parameter ( w ) approaching 0.5 indicates anomalous, non-Gaussian diffusion [19].

- If the system is non-ergodic and the propagator is non-Gaussian, a CTRW model regulated by transient binding is a likely candidate. Pharmacological disruption (e.g., inhibiting actin polymerization) can test this: if ergodicity is recovered, the actin cytoskeleton is implicated in the trapping mechanism [19].

Visualization of Workflows and Relationships

Diagnostic Workflow for Anomalous Diffusion

The following diagram outlines a logical decision tree for diagnosing the nature of anomalous diffusion based on single-particle tracking data.

Diagram Title: Diagnostic Workflow for Anomalous Diffusion in SPT

Integrated Processing Pipeline for dMRI

This workflow integrates denoising and motion correction steps for robust diffusion MRI data processing.

Diagram Title: Integrated dMRI Processing Pipeline

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Item Name | Type/Category | Primary Function | Key Application Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| saspt [18] | Software Package (Python) | Infers distributions of diffusion coefficients from short SPT trajectories. | Robust to variable localization error and defocalization bias; superior to DPMM for realistic SPT data. |

| MP-PCA Denoising [16] [21] [17] | Algorithm (e.g., in MRtrix3) | Reduces thermal noise in dMRI using Marchenko-Pastur theory for PCA thresholding. | Reduces noise variance but may not fully address noise floor bias; consider application in complex domain. |

| LKPCA-NLM [17] | Denoising Algorithm | Combines kernel PCA (nonlinear redundancy) and non-local means (spatial similarity) for DWI. | Outperforms MP-PCA and other methods in preserving structure and improving fiber tracking. |

| Eddy & SHORELine [21] | Motion Correction Tool | Corrects for head motion and eddy current distortions in dMRI. | Eddy: For shell-based acquisitions. SHORELine: For any sampling scheme (e.g., DSI). |

| ExploreDTI [20] | Software Suite (GUI) | A comprehensive graphical environment for processing and analyzing dMRI data. | Provides a step-by-step guide for multi-shell HARDI processing, including drift and Gibbs correction. |

| Actin Polymerization Inhibitors [19] | Pharmacological Reagent | Disrupts actin cytoskeleton to test its role in anomalous diffusion and non-ergodicity. | If treatment recovers ergodicity, it confirms actin's role in particle trapping via a CTRW mechanism. |

| N-Hydroxy Riluzole | N-Hydroxy Riluzole, CAS:179070-90-7, MF:C8H5F3N2O2S, MW:250.20 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Zuclopenthixol | Zuclopenthixol - CAS 53772-83-1|Dopamine Antagonist | Zuclopenthixol is a potent D1/D2 dopamine receptor antagonist for schizophrenia research. For Research Use Only. Not for human consumption. | Bench Chemicals |

The study of particle diffusion is a cornerstone of many scientific fields, from biology and physics to materials science. While Brownian motion, characterized by a linear growth of the Mean Squared Displacement (MSD) over time (MSD ∠t), has been the traditional model for random particle movements, many systems in nature exhibit deviations from this normal diffusion [7]. These deviations, termed anomalous diffusion, are identified by a MSD that follows a power-law (MSD ∠t^α) with an anomalous exponent α ≠1 [7]. Subdiffusion (0 < α < 1) occurs when particle motion is hindered, while superdiffusion (α > 1) indicates enhanced, often directed, motion [7].

Accurately characterizing these processes is crucial for understanding the underlying physical mechanisms in complex systems, such as the transport of molecules within living cells [7]. This article explores four fundamental physical models developed to describe anomalous diffusion: Continuous-Time Random Walk (CTRW), Fractional Brownian Motion (FBM), Lévy Walks (LW), and Scaled Brownian Motion (SBM). The correct interpretation of diffusion calculations, particularly in computational studies, relies on the use of unwrapped coordinates to ensure that periodic boundary conditions in simulations do not artificially suppress the true displacement of particles [22]. Framed within the context of a broader thesis on unwrapping coordinates for correct diffusion calculation research, this guide provides detailed application notes and protocols for researchers.

Theoretical Foundations of Key Models

Model Definitions and Mathematical Principles

Continuous-Time Random Walk (CTRW): Introduced by Montroll and Weiss, CTRW generalizes the classic random walk by incorporating a random waiting time between particle jumps [23]. A walker starts at zero and, after a waiting time Ï„â‚, makes a jump of size θâ‚, then waits for time Ï„â‚‚ before jumping θ₂, and so on [24]. The waiting times Ï„áµ¢ and jump lengths θᵢ are independent and identically distributed random variables, characterized by their probability density functions (PDFs), ψ(Ï„) for waiting times and f(ΔX) for jump lengths [23]. The position of the walker at time t is given by X(t) = Σᵢθᵢ, where the sum is over the number of jumps N(t) that have occurred by time t [24]. CTRW is particularly powerful for modeling non-ergodic processes and is widely used to describe subdiffusion in amorphous materials and disordered media [23] [24].

Fractional Brownian Motion (FBM): FBM is a continuous-time Gaussian process BH(t) that generalizes standard Brownian motion [25]. Its key characteristic is that its increments are correlated, unlike the independent increments of standard Brownian motion. This correlation structure is defined by its covariance function: E[BH(t)B_H(s)] = ½(|t|²ᴴ + |s|²ᴴ - |t-s|²ᴴ) [25]. The Hurst index, H, which is a real number in (0,1), dictates the nature of these correlations [25]. FBM is self-similar and exhibits long-range dependence (LRD) when H > 1/2 [26]. A process is considered long-range dependent if its autocorrelations decay to zero so slowly that their sum does not converge [26].

Lévy Walks (LW): LWs are a type of random walk where the walker moves with a constant velocity for a random time or distance before changing direction, with the step lengths drawn from a distribution that has a heavy tail [7]. This heavy-tailed characteristic allows for a high probability of very long steps, leading to superdiffusive behavior. LWs are effective for modeling processes like animal foraging patterns and the spread of diseases [7].

Scaled Brownian Motion (SBM): SBM is a process where the diffusivity is explicitly time-dependent [7]. It can be viewed as standard Brownian motion with a diffusion coefficient that scales as a power law with time. This model is often used as a phenomenological approach to describe anomalous diffusion, though it is important to note that it can be non-ergodic [7].

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Anomalous Diffusion Models

| Model | Abbreviation | Anomalous Exponent (α) | Increment Correlation | Ergodicity | Primary Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Continuous-Time Random Walk | CTRW | 0 < α < 1 (Subdiffusion) | Uncoupled/Coupled | Typically Non-Ergodic | Random waiting times |

| Fractional Brownian Motion | FBM | 0 < α < 2 | Positively (H>1/2) or Negatively (H<1/2) correlated | Ergodic | Long-range correlations |

| Lévy Walk | LW | α > 1 (Superdiffusion) | --- | Non-Ergodic | Heavy-tailed step lengths |

| Scaled Brownian Motion | SBM | α ≠1 | --- | Often Non-Ergodic | Time-dependent diffusivity |

Quantitative Parameter Comparison

The models can be distinguished by their statistical properties and the parameters they yield from experimental data. In medical imaging, for instance, non-Gaussian models like CTRW and FBM have been adapted for Diffusion-Weighted Imaging (DWI) to provide quantitative parameters that reflect tissue heterogeneity.

Table 2: Quantitative Parameters from Diffusion Models in Medical Imaging (DWI)

| Model | Key Parameters | Physical/Microstructural Interpretation | Exemplary Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| CTRW (DWI) | DCTRW, αCTRW, βCTRW | D: Diffusion coefficient; α: Temporal heterogeneity; β: Spatial heterogeneity [27]. | Differentiating benign from malignant head and neck lesions, with αCTRW showing high diagnostic performance (AUC) [27]. |

| FBM (DWI) | DFROC, βFROC, μFROC | D: Diffusion coefficient; β: Structural complexity; μ: Diffusion environment [27]. | Assessing tissue properties in rectal carcinoma, reflecting diffusion dynamics and complexity [27]. |

| Stretched Exponential (DWI) | DDC, α | DDC: Distributed Diffusion Coefficient; α: Heterogeneity parameter [28]. | Characterizing rectal cancer, where the model provided superior fitting of DWI signal decay [28]. |

| Intra-Voxel Incoherent Motion (IVIM) | D (slow ADC), D* (fast ADC), f | D: Pure diffusion coefficient; D*: Perfusion-related coefficient; f: Perfusion fraction [28]. | Assessing tissue properties in rectal cancer; the slow ADC parameter (D) often shows higher diagnostic utility and reliability than fast ADC (D*) [28]. |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

General Protocol for Single Trajectory Analysis

The Anomalous Diffusion (AnDi) Challenge established a standardized framework for comparing methods to decode anomalous diffusion from individual particle trajectories [7]. The following protocol is adapted from this initiative.

I. Problem Definition and Task Identification

- T1 - Exponent Inference: Determine the anomalous exponent α from a single trajectory.

- T2 - Model Classification: Identify the underlying diffusion model (CTRW, FBM, LW, SBM, etc.) from a single trajectory.

- T3 - Trajectory Segmentation: For a trajectory with heterogeneous behavior, identify the changepoint(s) where the exponent α or the diffusion model switches, and characterize the homogeneous segments [7].

II. Data Acquisition and Preprocessing

- Acquire Trajectories: Obtain single-particle tracking data (1D, 2D, or 3D) from experiments or simulations. Ensure metadata such as time resolution and localization precision are recorded.

- Preprocess Data: Apply necessary corrections for drift and noise. A critical step is to unwrap particle coordinates to account for periodic boundary conditions in simulations or to correctly calculate long-distance displacements without artifacts [22].

- Format Data: Structure the trajectory data as a time series of particle positions, e.g., {xâ‚, yâ‚, zâ‚; xâ‚‚, yâ‚‚, zâ‚‚; ...; xN, yN, z_N}.

III. Method Selection and Application

- Select an analysis method appropriate for the task (T1, T2, T3) and trajectory dimension. The AnDi challenge showed that machine-learning-based methods generally achieved superior performance, but no single method performed best across all scenarios [7].

- For T1, traditional methods involve fitting the time-averaged MSD (TA-MSD) or ensemble-averaged MSD (EA-MSD) to a power law, but these can be biased for short, noisy, or non-ergodic trajectories [7].

- For T2, use classifiers trained on features derived from the trajectories (e.g., MSD scaling, velocity autocorrelation, p-variation) or employ deep learning models like Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) and Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) [7].

- For T3, apply changepoint detection algorithms capable of identifying shifts in the diffusion exponent or model [7].

IV. Validation and Interpretation

- Validate Results: Use benchmark datasets with known parameters, like those from the AnDi challenge, to validate the performance of the chosen method.

- Report Metrics: For T1, report the estimated α and its confidence interval. For T2, report the classification accuracy or confidence score. For T3, report the changepoint location and the parameters for each segment.

- Interpret Physically: Relocate the statistical results (α, model) back to the physical context of the experiment (e.g., cellular crowding suggesting subdiffusion).

Protocol for Diffusion Calculation from Molecular Dynamics

The SLUSCHI framework provides a robust, automated protocol for calculating diffusion coefficients from ab initio molecular dynamics (AIMD) simulations, which is critical for validating model predictions against first-principles calculations [22].

I. System Setup and Equilibration

- Prepare Input Files: Generate standard VASP inputs (INCAR, POSCAR, POTCAR). Configure the

job.infile with key parameters: target temperature, pressure, supercell size (radius), and k-point mesh (kmesh). - Equilibrate System: Use the SLUSCHI framework to run an NPT or NVT molecular dynamics simulation to equilibrate the system at the target thermodynamic state. This ensures proper volume and density before production runs [22].

II. Production MD Run and Trajectory Generation

- Launch Production MD: Execute a long MD trajectory in the

Dir_VolSearchdirectory to collect sufficient data for diffusion analysis. The simulation length should capture tens of picoseconds of diffusive motion. - Extract Unwrapped Trajectories: The SLUSCHI post-processing module automatically parses the VASP outputs (e.g., OUTCAR) to extract unwrapped atomic trajectories for each species [22]. This step is vital for obtaining correct mean-squared displacements.

III. Mean-Squared Displacement (MSD) Calculation

- Compute Species-Resolved MSD: For each atomic species α, the MSD is calculated as:

MSD_α(t) = (1/N_α) Σᵢ ⟨ |rᵢ(t₀ + t) - rᵢ(t₀)|² ⟩_{t₀}where the sum is over all N_α atoms of species α, and the angle brackets denote averaging over all possible time origins t₀ [22]. - Identify Diffusive Regime: Plot the MSD versus time and identify the linear regime where the dynamics are diffusive.

IV. Diffusion Coefficient Extraction and Error Analysis

- Apply Einstein Relation: The self-diffusion coefficient D_α for species α is obtained from the slope of the MSD in the linear regime:

D_α = (1/(2d)) * (d(MSD_α(t))/dt)where d=3 is the spatial dimension [22]. - Quantify Uncertainty: Perform block averaging to estimate the statistical error bars for the calculated diffusion coefficients [22].

- Generate Diagnostics: Automatically produce diagnostic plots, including MSD curves, running slopes, and velocity autocorrelation functions, to validate the quality of the diffusion calculation [22].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational and Experimental Tools for Diffusion Research

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function | Relevance to Diffusion Studies |

|---|---|---|---|

| AnDi Challenge Dataset | Benchmark Data | Provides standardized datasets of synthetic and experimental trajectories [7]. | Enables objective method development, validation, and comparison for Tasks T1-T3. |

| SLUSCHI-Diffusion Module | Computational Workflow | Automates AIMD simulations and post-processing for diffusion coefficients [22]. | Calculates tracer diffusivities from first principles, providing benchmark data for model validation. |

| Unwrapped Coordinates | Data Preprocessing | Corrects for periodic boundary effects in particle trajectories [22]. | Essential for calculating correct MSD values in molecular dynamics simulations. |

| Block Averaging | Statistical Method | A technique for quantifying statistical error in time-series data [22]. | Provides robust error estimates for computed diffusion coefficients. |

| Non-Gaussian DWI Models (CTRW, FROC) | Medical Imaging Analysis | Extracts microstructural parameters from diffusion-weighted MRI [27]. | Translates physical diffusion models into clinical biomarkers for tissue characterization (e.g., tumor diagnosis). |

| Edonentan Hydrate | Edonentan Hydrate, CAS:264609-13-4, MF:C28H34N4O6S, MW:554.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| N-Octylnortadalafil | N-Octylnortadalafil, CAS:1173706-35-8, MF:C29H33N3O4, MW:487.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Applications and Visualized Pathways

Application in Medical Diagnosis

Non-Gaussian diffusion models have demonstrated significant value as non-invasive biomarkers in medical imaging, particularly in oncology. For example, in differentiating benign and malignant head and neck lesions, parameters derived from the CTRW and FROC (a model related to FBM) models showed superior performance compared to the conventional Apparent Diffusion Coefficient (ADC) [27]. Specifically, the temporal heterogeneity parameter from CTRW (αCTRW) achieved the highest diagnostic performance (Area Under the Curve, AUC) among all tested parameters [27]. Furthermore, several of these diffusion parameters, such as DFROC, DCTRW, and αCTRW, showed significant negative correlations with the Ki-67 proliferation index, a marker of tumor aggressiveness [27]. This indicates that these parameters can reflect underlying tumor cellularity and heterogeneity.

Decision Pathway for Model Selection

Selecting the appropriate model for analyzing an anomalous diffusion process requires a structured approach based on the characteristics of the observed data. The following decision pathway visualizes this selection logic.

Computational Methods and Hybrid Modeling for Robust Coordinate Processing

Phase unwrapping is a critical image processing operation required in numerous scientific and clinical domains, including magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), synthetic aperture radar (SAR), and fringe projection profilometry [29] [30] [31]. The problem arises because measured phase data is inherently wrapped into the principle value range of [-π, π] due to the use of the arctangent function during acquisition. The core mathematical objective is to recover the true, continuous unwrapped phase φ from the wrapped measurement ψ by finding the correct integer wrap count k for each pixel, such that φ(x,y) = ψ(x,y) + 2πk(x,y) [32] [33].

This process is fundamental for correct diffusion calculation research, as errors in phase unwrapping propagate directly into subsequent calculations of physical parameters, such as magnetic field inhomogeneities in MRI-based diffusion studies or 3D surface reconstructions in profilometry [34] [33]. The task is inherently ill-posed and complicated by noise, occlusions, and genuine phase discontinuities, leading to the development of diverse algorithmic families. This application note details the protocols, performance, and implementation of three pivotal approaches: Laplacian-based, Quality-Guided, and Graph-Cuts methods.

Algorithmic Methodologies & Comparative Performance

Core Algorithm Classifications and Characteristics

Table 1: Fundamental Classification of Phase Unwrapping Algorithms

| Algorithm Class | Core Principle | Key Strength | Inherent Limitation | Representative Methods |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Path-Following | Unwraps pixels sequentially along a path determined by a quality map. | High computational efficiency [29]. | Path-dependent; prone to error propagation across the image [29] [32]. | Quality-Guided (QGPU) [32] [35], Branch-Cut [29]. |

| Path-Independent / Global Optimization | Solves for the unwrapped phase by minimizing a global error function. | Avoids error propagation; robust in noisy regions [29]. | Can smooth out genuine discontinuities; computationally intensive [29] [32]. | Least-Squares Methods (LSM) [29], Poisson-based [29] [31]. |

| Energy-Based / Minimum Discontinuity | Frames unwrapping as a pixel-labeling problem and minimizes a global energy function. | High accuracy; handles discontinuities well [36]. | Very high computational cost [36]. | GraphCut [36]. |

| Deep Learning-Based | Uses neural networks to learn the mapping from wrapped to unwrapped phase. | Fast inference; highly robust to noise [32] [33]. | Performance depends on training data quality and scope [29] [33]. | PHU-NET [33], DIP-UP [33], Spatial Relation Awareness Module [32]. |

Quantitative Performance Comparison

Table 2: Empirical Performance of Phase Unwrapping Algorithms

| Algorithm | Reported Accuracy (Simulation) | Reported Speed | Robustness to Noise | Key Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Poisson-Coupled Fourier (Laplacian) | High (Significantly improves unwrapping accuracy) [29] | High (Computationally efficient, uses FFT) [29] | High (Robust under noise and phase discontinuities) [29] | Fringe Projection Profilometry (FPP) [29] |

| Quality-Guided Flood-Fill | Moderate (MSE: 0.0008 with proposed BgCQuality map) [35] | Moderate (64s for high-res images) [35] | Low to Moderate (Sensitive to noise without robust quality map) [32] [35] | Structured Light 3D Reconstruction [35] |

| ΦUN (Region Growing) | High (Very good agreement with gold standard) [30] | High (Significantly faster at low SNR) [30] | High (Optimized for low SNR and high-resolution data) [30] | Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) [30] |

| Hierarchical GraphCut with ID Framework | High (Lowest L² error in comparisons) [36] | Very High (45.5x speedup over baseline) [36] | High (Robust near abrupt surface changes) [36] | Structured-Light 3D Scanning [36] |

| DIP-UP (Deep Learning) | Very High (~99% accuracy) [33] | High (>3x faster than PRELUDE) [33] | High (Robust to noise, generalizes to different conditions) [33] | MRI, Quantitative Susceptibility Mapping (QSM) [33] |

Application Protocols

Protocol 1: Poisson-Coupled Fourier Unwrapping for Fringe Projection Profilometry

This protocol details the implementation of a path-independent, Laplacian-based method renowned for its balance of speed and accuracy [29].

1. Principle

A modified Laplacian operator is applied to the wrapped phase to formulate a path-independent Poisson equation, which is then solved efficiently in the frequency domain using the Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) [29] [31]. The relationship is given by:

k(r→) = (1/(2Ï€)) ∇â»Â² [ ∇²φ(r→) - ∇²ψ(r→) ]

where ∇² and ∇â»Â² are the forward and inverse Laplacians, computed via Discrete Cosine Transforms (DCT) to meet Neumann boundary conditions [31].

2. Experimental Workflow

3. Materials and Reagents

- Fringe Projection System: Comprising a digital projector (e.g., Texas Instruments DLPLCR4500EVM) and a high-resolution camera (e.g., Basler acA2040-120um) [29].

- Computing Hardware: Standard CPU with support for optimized FFT libraries (e.g., FFTW). For real-time applications, a GPU (e.g., NVIDIA CUDA-capable card) is recommended [31].

- Software: Implementation of the Poisson-coupled Fourier algorithm, often in C/C++ or Python with SciPy.

4. Procedure

1. Data Acquisition: Project and capture a set of phase-shifted fringe patterns onto the target object. Extract the wrapped phase map ψ using a standard phase-shifting algorithm (e.g., four-step phase-shifting) [29].

2. Boundary Processing: Apply boundary extension and a Tukey window to the wrapped phase map ψ to balance the periodicity assumption inherent in FFT with non-periodic boundary conditions, thereby minimizing edge artifacts [29].

3. Laplacian Calculation:

- Compute the terms sin(ψ) and cos(ψ).

- Calculate their 2D Laplacians, ∇²(sin(ψ)) and ∇²(cos(ψ)), using the DCT-based method in Equation 3 of the search results [31].

- Compute the Laplacian of the true phase using the identity: ∇²φ = cos(ψ)∇²(sin(ψ)) - sin(ψ)∇²(cos(ψ)) [31].

4. Inverse Laplacian Solution: Apply the inverse Laplacian operator ∇â»Â² to ∇²φ using the Inverse Discrete Cosine Transform (IDCT) to obtain an initial estimate of the unwrapped phase [31].

5. Wrap Count Determination: Calculate the integer wrap count field k by integrating the result from the previous step into the Poisson formulation [29] [31]. The final unwrapped phase is φ = ψ + 2πk.

5. Validation and Analysis

- Quantitative Analysis: Compare against a known ground truth (e.g., a simulated phase map with a "peaks" function, PV of 14Ï€ radians) using metrics like Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) [29].

- Qualitative Analysis: Visually inspect the unwrapped phase for smoothness and the absence of unwrapping "grips" or discontinuities, especially in regions with high phase gradients [29].

Protocol 2: Quality-Guided Phase Unwrapping for Structured Light 3D Reconstruction

This protocol outlines the use of path-following methods guided by a quality map, which is crucial for applications requiring a balance of speed and reliability in moderately noisy environments [32] [35].

1. Principle The algorithm computes a "quality" or "reliability" value for each pixel, which quantifies the likelihood of a correct unwrapping path. Unwrapping begins at the highest-quality pixel and progresses to neighboring pixels based on a priority queue, thereby reducing the propagation of errors from low-quality regions [32] [35].

2. Experimental Workflow

3. Materials and Reagents

- Quality Map: The core reagent in this protocol. The BgCQuality map, which integrates central curl and modulation information, is a recent innovation that provides heightened sensitivity to phase discontinuities and noise [35].

- Computing Hardware: Standard desktop computer. The algorithm can be implemented without specialized hardware.

- Software: Custom code in C++, Java, or Python for implementing the priority queue and unwrapping logic.

4. Procedure

1. Quality Map Calculation: Compute a quality map R(x,y) for the entire wrapped phase ψ. For example, the second-difference quality map D(x,y) can be calculated within a 3x3 window using horizontal (H), vertical (V), and diagonal (D1, D2) second differences [32]:

D(x,y) = [H²(x,y) + V²(x,y) + D1²(x,y) + D2²(x,y)]^(1/2)

The reliability is then R = 1/D [32]. Alternatively, use the novel BgCQuality map for improved performance [35].

2. Seed Point Selection: Locate the pixel with the highest reliability value in the quality map and mark it as the initial seed. This pixel is considered correctly unwrapped (its k value is known or assumed to be zero) [32].

3. Region Growing:

- Add the seed point to a "unwrapped" region and place all its non-unwrapped neighbors into a priority queue, with their priority determined by their quality value.

- While the priority queue is not empty, pop the pixel with the highest quality from the queue.

- Unwrap this pixel by adding an integer multiple of 2Ï€ to make its phase value consistent with its already-unwrapped neighbors.

- Add this pixel to the "unwrapped" region and push its non-unwrapped neighbors into the priority queue.

4. Iteration: Repeat step 3 until all pixels in the phase map have been processed.

5. Validation and Analysis

- Performance Metric: Evaluate using Mean Square Error (MSE) against a ground truth. The hybrid algorithm using BgCQuality has been shown to achieve an MSE as low as 0.0008 [35].

- Execution Time: Measure the time to unwrap high-resolution images (e.g., ~64 seconds for a given high-resolution image) and compare against standard flood-fill methods [35].

Protocol 3: GraphCut Phase Unwrapping for High-Accuracy 3D Scanning

This protocol describes an energy-based, minimum-discontinuity method reformulated as a pixel-labeling problem, ideal for applications demanding high precision, even near abrupt surface changes [36].

1. Principle

The algorithm assigns an integer wrap count k to each pixel by minimizing a global energy function that typically includes a data fidelity term and a discontinuity-preserving smoothness term. This is framed as a maximum a posteriori (MAP) estimation problem and solved efficiently using graph theory algorithms like max-flow/min-cut [36].

2. Experimental Workflow

3. Materials and Reagents

- Energy Function Formulation: The core component. A typical function is

E(f) = Σ (data penalty) + λ Σ (smoothness penalty)wherefis the labeling of wrap countsk[36]. - Invariance of Diffeomorphisms (ID) Framework: A novel theoretical foundation that applies conformal mappings and Optimal Transport (OT) maps to create multiple, equivalently deformed versions of the input phase data. This framework enhances robustness and accuracy [36].

- Computing Hardware: High-performance workstation. The GraphCut algorithm and the ID framework are computationally intensive and may benefit from parallel processing.

4. Procedure

1. Problem Formulation: Define the phase unwrapping task as a pixel-labeling problem where the label set â„’ consists of possible integer wrap counts k [36].

2. Energy Function Definition: Construct an energy function E(f) to be minimized. The function should penalize differences between the gradients of the unwrapped and wrapped phase while allowing for genuine discontinuities [36].

3. Invariance of Diffeomorphisms (ID) Application:

- Precompute an odd number of diffeomorphisms (e.g., conformal maps, OT maps) from the input phase data, creating several deformed versions of the image [36].

- Apply a hierarchical GraphCut algorithm independently to each of these deformed domains to solve for the wrap count k in each domain [36].

4. Result Fusion: Fuse the resulting label maps from each deformed domain using majority voting. Using an odd number of maps helps break ties [36].

5. Phase Calculation: Reconstruct the final unwrapped phase using the fused wrap count map: φ = ψ + 2πk.

5. Validation and Analysis

- Accuracy: Evaluate using the

L²error norm against ground truth data. The ID-Hierarchical GraphCut method has demonstrated the lowestL²error in comparative studies [36]. - Speed: Benchmark the total processing time. The proposed framework has achieved a 45.5x speedup over the baseline GraphCut algorithm, making it suitable for near-real-time applications [36].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Phase Unwrapping

| Research Reagent | Function / Purpose | Example Implementation / Note |

|---|---|---|

| BgCQuality Map | A novel quality map that integrates central curl and modulation information to guide unwrapping paths with high sensitivity to discontinuities and noise [35]. | Used in hybrid quality-guided algorithms to achieve lower Mean Square Error (e.g., 0.0008) compared to traditional quality maps [35]. |

| Invariance of Diffeomorphisms (ID) Framework | A theoretical framework that leverages the invariance of signals under smooth, invertible mappings to improve the robustness of pixel-labeling algorithms [36]. | Applied by generating multiple deformed phase maps via conformal and Optimal Transport maps, enabling robust label fusion via majority voting [36]. |

| Deep Image Prior for Unwrapping Phase (DIP-UP) | A framework that refines pre-trained deep learning models for phase unwrapping without needing extensive labeled data, leveraging the innate structure of a neural network [33]. | Used to enhance models like PHUnet3D and PhaseNet3D, improving unwrapping accuracy to ~99% and robustness to noise [33]. |

| Poisson Equation Solver via DCT/FFT | The computational core of path-independent methods, solving the Poisson equation efficiently in the frequency domain [29] [31]. | Implemented using Fast Fourier Transforms (FFT) or Discrete Cosine Transforms (DCT) on CPUs or GPUs for high-speed processing (e.g., <5 ms for 640x480 images on a GPU) [31]. |

| Phase Image Texture Analysis (PITA-MDD) | An image-based method for detecting motion corruption in Diffusion MRI by analyzing the homogeneity of phase images [34]. | Calculates Haralick's Homogeneity Index (HHI) on a slice-by-slice basis to trigger re-acquisition of motion-corrupted data, improving final tractography results [34]. |

| 6-Aminoquinoline | 6-Aminoquinoline, CAS:580-15-4, MF:C9H8N2, MW:144.17 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Arbutamine | Arbutamine, CAS:128470-16-6, MF:C18H23NO4, MW:317.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The accurate calculation of molecular diffusion is a cornerstone in the development of advanced drug delivery systems, such as controlled-release formulations, membranes, and nanoparticles [37]. The core phenomenon controlling the release rate in these systems is molecular diffusion, which is governed by concentration gradients within a three-dimensional space [37]. Traditional methods for simulating this diffusion, primarily based on Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD), are computationally intensive and time-consuming, presenting a significant bottleneck in research and development [37]. This application note details robust protocols for applying three machine learning (ML) regression models—Support Vector Regression (SVR), Kernel Ridge Regression (KRR), and Multi Linear Regression (MLR)—to predict drug concentration in 3D space efficiently. Framed within broader thesis research on "unwrapping coordinates for correct diffusion calculation," these methods leverage spatial coordinates (x, y, z) as inputs to directly predict chemical species concentration (C), offering a powerful and computationally efficient alternative to traditional simulation techniques [37].

Key Machine Learning Models for Diffusion Analysis

This section outlines the core algorithms and their performance in the context of diffusion modeling.

ν-Support Vector Regression (ν-SVR): This model extends Support Vector Machines to regression tasks. It aims to find a function that deviates from the observed training data by a value no greater than a specified margin (ε), while simultaneously maximizing the margin. Theνparameter controls the number of support vectors and training errors, providing flexibility in handling non-linear relationships through kernel functions [37].- Kernel Ridge Regression (KRR): KRR combines Ridge Regression (which introduces L2 regularization to prevent overfitting) with the kernel trick. This allows it to model non-linear relationships by projecting input features into a higher-dimensional space, making it suitable for complex, non-linear diffusion processes [37].

- Multi Linear Regression (MLR): MLR is a fundamental statistical technique that assumes a linear relationship between the independent input variables (spatial coordinates) and the dependent target variable (concentration). It serves as a strong baseline for model performance comparison [37].

Quantitative Performance Comparison

A recent hybrid study utilizing mass transfer and machine learning for 3D drug diffusion analysis demonstrated the following performance metrics, highlighting the superior predictive capability of ν-SVR [37].

Table 1: Comparative performance of SVR, KRR, and MLR in predicting 3D drug concentration.

| Model | R² Score | Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) | Mean Absolute Error (MAE) |

|---|---|---|---|

ν-Support Vector Regression (ν-SVR) |

0.99777 | Lowest | Lowest |

| Kernel Ridge Regression (KRR) | 0.94296 | Medium | Medium |

| Multi Linear Regression (MLR) | 0.71692 | Highest | Highest |

Experimental Protocols

This section provides a detailed, step-by-step methodology for implementing the described ML workflow for diffusion analysis.

Data Acquisition and Preprocessing Protocol

Objective: To generate and prepare a high-quality dataset for model training. Materials: Computational resources for CFD simulation (e.g., ANSYS, OpenFOAM), Python programming environment with scikit-learn library.

CFD Data Generation:

- Define a simple 3D geometry representing the drug diffusion medium [37].

- Set up and solve the mass transfer equation (Fick's law of diffusion) within the domain using a finite volume scheme. The governing equation is:

∂C/∂t = D * (∂²C/∂x² + ∂²C/∂y² + ∂²C/∂z²)whereCis concentration,tis time, andDis the diffusion coefficient [37]. - Apply insulation (zero-flux) boundary conditions on the walls of the medium [37].

- Extract the concentration data at a specific median time point from the solved CFD domain. The resulting dataset should consist of over 22,000 data points, each containing the coordinates (x, y, z) and the corresponding concentration (C) in mol/m³ [37].

Data Preprocessing:

- Outlier Removal: Employ the Isolation Forest algorithm from scikit-learn to identify and remove anomalous data points that could negatively impact model training [37].

- Data Normalization: Apply the Min-Max Scaler to normalize all input features (x, y, z) and the target variable (C) to a specified range, typically [0, 1]. This ensures that no single variable dominates the model due to its scale [37]. The formula is:

X_norm = (X - X_min) / (X_max - X_min)