The Verlet Algorithm in Molecular Dynamics: A Complete Guide for Biomedical Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of the Verlet algorithm, a cornerstone of Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations.

The Verlet Algorithm in Molecular Dynamics: A Complete Guide for Biomedical Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of the Verlet algorithm, a cornerstone of Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, we cover its foundational principles rooted in Newtonian mechanics, detailed implementation of its key variants (Velocity Verlet, Leap-Frog), and practical guidance for troubleshooting and optimizing simulations. The guide also includes a critical comparison with other numerical integrators and validates the algorithm's properties, highlighting its indispensable role in achieving accurate, stable, and energy-conserving simulations for biomolecular systems and drug discovery.

Understanding the Verlet Algorithm: From Newton's Laws to Numerical Integration

The Role of Numerical Integration in Molecular Dynamics Simulations

Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulation is a powerful computational technique that predicts how a system of atoms or molecules evolves over time by numerically solving Newton's equations of motion. The core of any MD simulation is the integration algorithm, a numerical procedure that calculates atomic trajectories by stepping forward in discrete time increments. The choice of integrator is critical, as it directly impacts the simulation's accuracy, stability, and ability to conserve energy—properties essential for producing physically meaningful results. Among the various algorithms available, the family of Verlet integrators has become the cornerstone of modern molecular dynamics due to its favorable numerical properties and computational efficiency. This article explores the fundamental role of numerical integration in MD, with a specific focus on the Verlet algorithm and its variants, providing a technical guide for researchers and scientists in computational drug development and related fields.

Fundamental Principles of Molecular Dynamics

In Molecular Dynamics, the motion of a system of N atoms is described by Newton's second law:

[ Fi = mi ai = mi \frac{\partial^2 r_i}{\partial t^2} ]

where ( Fi ) is the force acting on atom ( i ), ( mi ) is its mass, ( ai ) is its acceleration, and ( ri ) is its position. The force is also equal to the negative gradient of the potential energy ( V ) that governs the interatomic interactions:

[ Fi = -\frac{\partial V}{\partial ri} ]

The analytical solution to these equations is not feasible for systems with more than two atoms; therefore, MD relies on numerical integration to approximate the trajectories. The general MD procedure involves:

- Initialization: Defining initial atomic positions and velocities.

- Force Calculation: Computing forces on all atoms based on the current configuration (the most computationally expensive step).

- Integration: Using an integration algorithm to update atomic positions and velocities over a small time step ( \Delta t ) (typically on the order of femtoseconds, ( 10^{-15} ) s).

- Iteration: Repeating steps 2 and 3 for thousands to millions of time steps to generate a trajectory.

The integration algorithm must balance several requirements: accuracy in describing atomic motion, stability in conserving system energy, simplicity of implementation, and computational speed.

The Verlet Algorithm: A Family of Integrators

The original Verlet algorithm, first used in 1791 and rediscovered by Loup Verlet in the 1960s, is one of the most widely used integration methods in MD. Its popularity stems from its numerical stability, time-reversibility, preservation of the symplectic form on phase space, and relatively low computational cost compared to simpler methods like Euler integration.

Mathematical Foundation

Verlet integration is derived from Taylor expansions of the position ( r(t) ) around time ( t ):

[ r(t + \Delta t) = r(t) + \Delta t v(t) + \frac{1}{2} \Delta t^2 a(t) + \frac{1}{6} \Delta t^3 b(t) + \mathcal{O}(\Delta t^4) ]

[ r(t - \Delta t) = r(t) - \Delta t v(t) + \frac{1}{2} \Delta t^2 a(t) - \frac{1}{6} \Delta t^3 b(t) + \mathcal{O}(\Delta t^4) ]

where ( v(t) ) is velocity, ( a(t) ) is acceleration, and ( b(t) ) is the third derivative (jerk). Adding these two equations eliminates the velocity and odd-order terms, yielding the basic Verlet algorithm:

[ r(t + \Delta t) = 2r(t) - r(t - \Delta t) + a(t) \Delta t^2 + \mathcal{O}(\Delta t^4) ]

The remarkable property of this formulation is that the position update has a local error of ( \mathcal{O}(\Delta t^4) ), despite not explicitly involving velocity.

Limitations and Variants

The basic Verlet algorithm has two main drawbacks:

- Velocities are not explicitly calculated, yet are needed for computing kinetic energy.

- It is not self-starting, as it requires positions from the previous time step ( r(t - \Delta t) ).

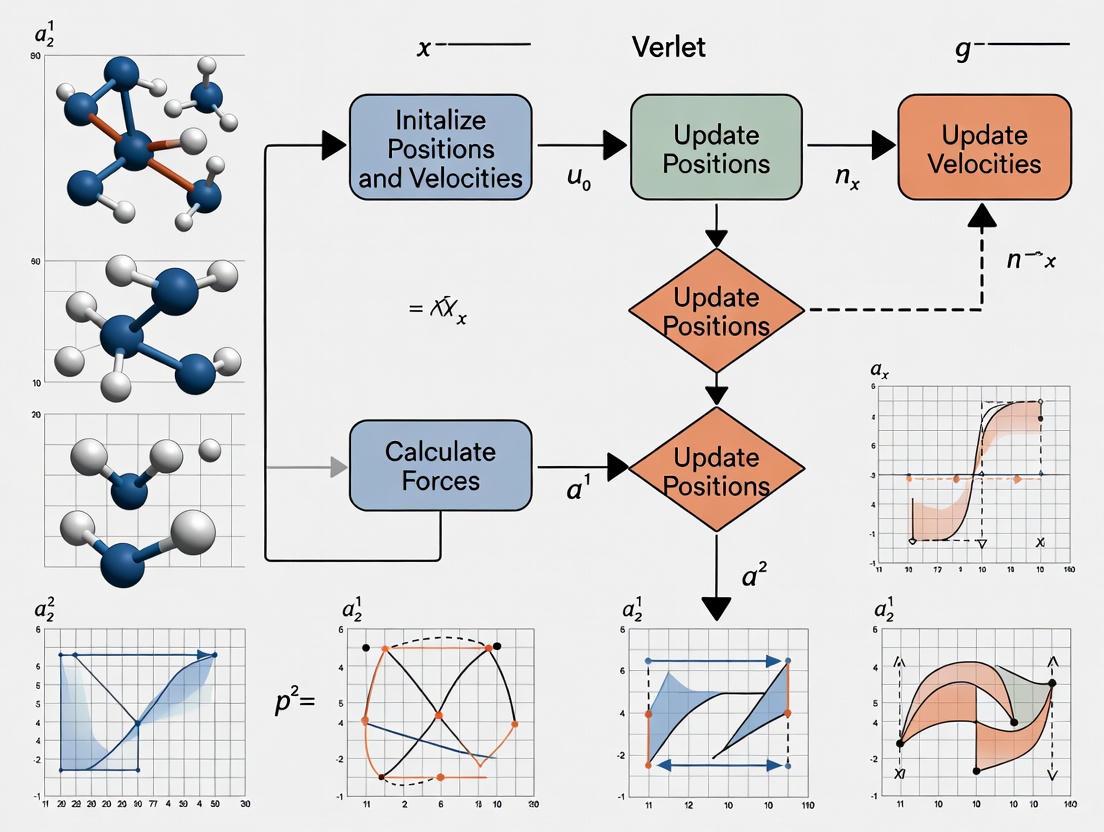

To address these limitations, several variants have been developed. The following workflow illustrates the relationships between the core Verlet algorithms and their key characteristics:

Key Verlet Integration Methods

Standard Verlet Algorithm

The standard Verlet method, also known as the Størmer-Verlet method, uses the position-update formula derived above. Although velocities are not needed for the trajectory propagation, they can be approximated to ( \mathcal{O}(\Delta t^2) ) accuracy using the central difference formula:

[ v(t) = \frac{r(t + \Delta t) - r(t - \Delta t)}{2\Delta t} ]

This approach is simple and memory-efficient but suffers from the velocities being out of sync with the positions.

Velocity Verlet Algorithm

The Velocity Verlet algorithm is the most commonly used variant in modern MD codes because it explicitly calculates positions and velocities at the same time instant. The algorithm proceeds in three steps:

- Update positions using current velocities and accelerations: [ r(t + \Delta t) = r(t) + v(t) \Delta t + \frac{1}{2} a(t) \Delta t^2 ]

- Calculate velocities at the half-step and compute new accelerations from forces at the new positions: [ v(t + \frac{\Delta t}{2}) = v(t) + \frac{1}{2} a(t) \Delta t ] [ a(t + \Delta t) = \frac{1}{m} F(r(t + \Delta t)) ]

- Complete the velocity update using the new acceleration: [ v(t + \Delta t) = v(t + \frac{\Delta t}{2}) + \frac{1}{2} a(t + \Delta t) \Delta t ]

In practice, this is often implemented as a two-step process for the velocity, combining steps 2 and 3 into: [ v(t + \Delta t) = v(t) + \frac{1}{2} [a(t) + a(t + \Delta t)] \Delta t ]

Velocity Verlet is time-reversible, symplectic (which leads to good long-term energy conservation), and requires only one force evaluation per time step.

Leapfrog Algorithm

The Leapfrog algorithm is another popular variant where velocities and positions are updated at slightly different times. The algorithm is defined by:

[ v(t + \frac{1}{2}\Delta t) = v(t - \frac{1}{2}\Delta t) + a(t) \Delta t ] [ r(t + \Delta t) = r(t) + v(t + \frac{1}{2}\Delta t) \Delta t ]

If full-step velocities are needed, they can be approximated as: [ v(t) = \frac{1}{2} \left[ v(t - \frac{1}{2}\Delta t) + v(t + \frac{1}{2}\Delta t) \right] ]

Leapfrog is computationally efficient and numerically stable, but the non-synchronous updates of positions and velocities can be inconvenient.

Comparative Analysis of Verlet Integrators

The following table provides a quantitative comparison of the key Verlet integrators and their properties:

Table 1: Comparison of Verlet Integration Algorithms

| Method | Position Error | Velocity Calculation | Velocity Error | Key Advantages | Key Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard Verlet | (\mathcal{O}(\Delta t^4)) | Not explicit | N/A | High position accuracy; Simple | Velocities not directly available |

| Störmer-Verlet | (\mathcal{O}(\Delta t^4)) | Derived from positions | (\mathcal{O}(\Delta t^2)) | Good for energy calculations | Lower velocity accuracy |

| Leapfrog Verlet | (\mathcal{O}(\Delta t^4)) | At half-steps | (\mathcal{O}(\Delta t^2)) | Economical memory use | Positions and velocities out of sync |

| Velocity Verlet | (\mathcal{O}(\Delta t^2)) | Explicit at full-step | (\mathcal{O}(\Delta t^2)) | Complete phase information; Self-starting | Slightly higher position error |

The performance of these integrators can also be compared against other common numerical methods:

Table 2: Performance and Stability Comparison of Integration Algorithms

| Method | Evaluations of Acceleration Function | Stability: Underdamped Systems | Stability: Overdamped Systems | Overall Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Euler | 1 | Poor | Excellent | Low |

| Velocity Verlet | 1 | Excellent | Good | High |

| Improved Euler | 2 | Good | Fair | Medium |

| Runge-Kutta 4 (RK4) | 4 | Good | Poor | Very High |

As shown in Table 2, Velocity Verlet provides an excellent balance between computational cost (only one force evaluation per step) and stability, particularly for the underdamped systems commonly encountered in molecular dynamics.

Advanced Applications and Optimizations

Molecular Dynamics with Constraints

In simulations of molecules with strong chemical bonds, the standard Verlet algorithm is often combined with constraint algorithms like SHAKE and RATTLE. These methods rigidly enforce bond lengths and angles, preventing numerically stiff forces from limiting the time step. The original Verlet algorithm works naturally with SHAKE, while Velocity Verlet requires RATTLE, which applies constraints to both positions and velocities. Recent research has focused on optimizing these constraint algorithms to reduce the computational overhead associated with the double calculation of Lagrange multipliers in standard implementations.

Optimized Verlet-like Algorithms

Research continues to develop improved versions of Verlet algorithms. For instance, one study introduced explicit velocity- and position-Verlet-like algorithms containing a free parameter that is optimized to minimize the influence of truncated terms. These optimized algorithms demonstrate improved accuracy in simulations of Lennard-Jones fluids while maintaining the same computational cost and preserving the symplectic and time-reversible properties of the original Verlet methods.

Experimental Protocol: Implementing Velocity Verlet

For researchers implementing MD simulations, the following detailed protocol outlines the Velocity Verlet integration process:

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Components for MD Simulations

| Component | Function |

|---|---|

| Initial Atomic Coordinates | Provides starting configuration of the molecular system (e.g., from protein data bank structures) |

| Force Field Parameters | Defines potential energy function (bonds, angles, dihedrals, non-bonded interactions) |

| Integration Time Step (( \Delta t )) | Discrete time increment (typically 0.5-2 fs) for numerical integration |

| Thermostat/Barrowstat | Maintains constant temperature/pressure (e.g., Nosé-Hoover, Berendsen) |

| Periodic Boundary Conditions | Simulates bulk environment while minimizing finite-size effects |

| Neighbor Lists | Optimizes non-bonded force calculations (e.g., Verlet lists) |

Step-by-Step Methodology

System Initialization:

- Read initial atomic positions ( r(0) ) and velocities ( v(0) ).

- Assign masses ( m_i ) to all atoms.

- Compute initial forces ( F(0) ) and accelerations ( a(0) = F(0)/m_i ).

Main Integration Loop (repeat for desired number of steps):

- Position Update: Calculate new positions using: [ r(t + \Delta t) = r(t) + v(t) \Delta t + \frac{1}{2} a(t) \Delta t^2 ]

- Apply Constraints: If using constraint algorithms like RATTLE, enforce distance constraints on new positions.

- Force Calculation: Compute forces ( F(t + \Delta t) ) and accelerations ( a(t + \Delta t) ) based on new positions (most computationally intensive step).

- Velocity Update: Complete the velocity step using: [ v(t + \Delta t) = v(t) + \frac{1}{2} [a(t) + a(t + \Delta t)] \Delta t ]

- Apply Thermostat/Barostat: If simulating canonical (NVT) or isothermal-isobaric (NPT) ensembles, adjust velocities and positions accordingly.

- Sample Data: Record positions, velocities, energies, and other properties at specified intervals.

The following diagram illustrates the complete workflow of a molecular dynamics simulation using the Velocity Verlet integrator:

Numerical integration, particularly through the Verlet family of algorithms, plays an indispensable role in molecular dynamics simulations. The Velocity Verlet algorithm has emerged as the preferred method in most modern MD applications due to its combination of numerical stability, time-reversibility, symplectic properties, and explicit calculation of velocities. While the basic Verlet method provides excellent position accuracy, the need for velocity-dependent calculations in many applications makes Velocity Verlet the more versatile choice. Ongoing research continues to optimize these algorithms, particularly for handling constraints and improving accuracy without increasing computational cost. For researchers in drug development and molecular science, understanding these integration techniques is crucial for designing reliable simulations that can accurately predict molecular behavior and interactions.

Molecular dynamics (MD) is a computational technique that derives statements about the structural, dynamical, and thermodynamical properties of molecular systems by simulating their motion over time [1]. At the heart of every MD simulation lies the numerical integration of Newton's equations of motion, which describe how atomic positions evolve under the influence of interatomic forces [2]. The model system typically consists of a biomolecule such as a protein or enzyme immersed in an aqueous solvent, represented as a collection of interacting particles described as atoms [1].

In atomistic "all-atom" MD, the simulation box contains tens of thousands of atoms, and successive states at regular time intervals are stored in a trajectory for analysis [1]. The choice of integration algorithm is crucial, as it determines the numerical stability, accuracy, and conservation properties of the simulation [2]. This technical guide explores the mathematical foundation, implementation details, and practical applications of the Verlet family of algorithms, which have become the standard for MD simulations in drug discovery and pharmaceutical development.

Newton's Equations of Motion in Molecular Dynamics

Mathematical Foundation

Newton's equation of motion for conservative physical systems is expressed as:

[ \boldsymbol{M}\ddot{\mathbf{x}}(t) = \mathbf{F}(\mathbf{x}(t)) = -\nabla V(\mathbf{x}(t)) ]

For a system of N particles, this becomes:

[ mk\ddot{\mathbf{x}}k(t) = Fk(\mathbf{x}(t)) = -\nabla{\mathbf{x}_k}V(\mathbf{x}(t)) ]

Where:

- (t) represents time

- (\mathbf{x}(t) = (\mathbf{x}1(t), \ldots, \mathbf{x}N(t))) represents the positions of N particles

- (V) is the potential energy function

- (F) represents the forces acting on the particles

- (\boldsymbol{M}) is the diagonal mass matrix with elements (m_k) [2]

After transformation to bring mass to the right side, the equation simplifies to:

[ \ddot{\mathbf{x}}(t) = \mathbf{A}(\mathbf{x}(t)) ]

Where (\mathbf{A}(\mathbf{x})) represents the acceleration, with initial conditions (\mathbf{x}(0) = \mathbf{x}0) and (\mathbf{v}(0) = \dot{\mathbf{x}}(0) = \mathbf{v}0) [2].

Discretization for Numerical Solution

To discretize and numerically solve this initial value problem, a time step (\Delta t > 0) is chosen, and the time grid (tn = n\Delta t) is defined. The numerical approximation (\mathbf{x}n \approx \mathbf{x}(t_n)) is computed sequentially [2]. While Euler's method uses the forward difference approximation to the first derivative, Verlet integration employs the central difference approximation to the second derivative:

[ \frac{\Delta^2\mathbf{x}n}{\Delta t^2} = \frac{\mathbf{x}{n+1} - 2\mathbf{x}n + \mathbf{x}{n-1}}{\Delta t^2} = \mathbf{a}n = \mathbf{A}(\mathbf{x}n) ]

This formulation provides the mathematical basis for the Verlet algorithm [2].

The Verlet Integration Algorithm Family

Basic Størmer-Verlet Algorithm

The original Verlet algorithm uses positions at two successive time steps without explicitly storing velocities [2]. The procedure is as follows:

- Set (\mathbf{x}1 = \mathbf{x}0 + \mathbf{v}0\Delta t + \frac{1}{2}\mathbf{A}(\mathbf{x}0)\Delta t^2)

- For n = 1, 2, ... iterate: (\mathbf{x}{n+1} = 2\mathbf{x}n - \mathbf{x}{n-1} + \mathbf{A}(\mathbf{x}n)\Delta t^2) [2]

While velocities are not needed to compute trajectories, they can be estimated for calculating observables like kinetic energy using:

[ \mathbf{v}(t+\Delta t) = \frac{\mathbf{r}(t+\Delta t) - \mathbf{r}(t-\Delta t)}{2\Delta t} ]

The Verlet algorithm is time-reversible and energy-conserving, making it suitable for MD simulations [3].

Velocity Verlet Algorithm

The Velocity Verlet algorithm explicitly incorporates velocity, solving the problem of the first time step in the basic Verlet algorithm [3]. This algorithm maintains synchronous position and velocity vectors through these steps:

- (\mathbf{v}i(t + \frac{1}{2}\Delta t) = \mathbf{v}i(t) + \frac{\mathbf{F}i(t)}{2mi}\Delta t)

- (\mathbf{r}i(t + \Delta t) = \mathbf{r}i(t) + \mathbf{v}_i(t + \frac{1}{2}\Delta t)\Delta t)

- Compute forces (\mathbf{F}_i(t+\Delta t)) from the new positions

- (\mathbf{v}i(t + \Delta t) = \mathbf{v}i(t+\frac{1}{2}\Delta t) + \frac{\mathbf{F}i(t+\Delta t)}{2mi}\Delta t) [4]

Table 1: Comparison of Verlet Integration Algorithms

| Algorithm | Velocity Handling | Storage Requirements | Implementation Complexity | Conservation Properties |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Original Verlet | Implicit, calculated retrospectively | Lower (positions only) | Moderate | Time-reversible, energy-conserving |

| Velocity Verlet | Explicit, synchronous with positions | Higher (positions + velocities) | Straightforward | Time-reversible, energy-conserving |

| Leap-Frog | Explicit, staggered half-step | Moderate (positions + half-step velocities) | Moderate | Time-reversible, energy-conserving |

Leap-Frog Variant

The leap-frog algorithm is a modified version where velocities are not calculated at the same time as positions [3]. Instead, positions and velocities are computed at interleaved time points:

- Derive (\mathbf{a}(t)) from the interaction potential using positions (\mathbf{r}(t))

- Compute (\mathbf{v}(t+\frac{\Delta t}{2}) = \mathbf{v}(t-\frac{\Delta t}{2}) + \mathbf{a}(t)\Delta t)

- Compute (\mathbf{r}(t+\Delta t) = \mathbf{r}(t) + \mathbf{v}(t+\frac{\Delta t}{2})\Delta t) [3]

Though the restart files differ between Leap-Frog and Velocity Verlet, they produce equivalent trajectories [3].

Discretization Error and Numerical Stability

Error Analysis

The time symmetry inherent in the Verlet method reduces local discretization errors by removing all odd-degree terms [2]. Using Taylor expansions:

[ \mathbf{x}(t+\Delta t) = \mathbf{x}(t) + \mathbf{v}(t)\Delta t + \frac{\mathbf{a}(t)\Delta t^2}{2} + \frac{\mathbf{b}(t)\Delta t^3}{6} + \mathcal{O}(\Delta t^4) ]

[ \mathbf{x}(t-\Delta t) = \mathbf{x}(t) - \mathbf{v}(t)\Delta t + \frac{\mathbf{a}(t)\Delta t^2}{2} - \frac{\mathbf{b}(t)\Delta t^3}{6} + \mathcal{O}(\Delta t^4) ]

Adding these expansions gives:

[ \mathbf{x}(t+\Delta t) = 2\mathbf{x}(t) - \mathbf{x}(t-\Delta t) + \mathbf{a}(t)\Delta t^2 + \mathcal{O}(\Delta t^4) ]

This formulation demonstrates that the Verlet algorithm has fourth-order accuracy in position despite using only second-order derivatives [2].

Stability Considerations

Verlet integrators are stable for time steps satisfying (\Delta t \leq \frac{1}{\pi f}), where (f) is the oscillation frequency of the fastest motions in the system [3]. In molecular systems, the fastest motions are typically:

- Bond vibrations involving hydrogens: period of ~10 fs

- Bond vibrations of heavy atoms and angles involving hydrogens: period of ~20 fs

Since the period of oscillation of a C-H bond is about 10 fs, Verlet integration is theoretically stable for time steps < 3.2 fs, though in practice, a time step of 1 fs is recommended to reliably describe this motion [3].

Practical Implementation in MD Simulations

Time Step Selection and Constraints

Selecting an appropriate time step involves balancing computational efficiency with numerical accuracy. Larger time steps allow faster simulation but decrease accuracy [3]. Several strategies can increase the usable time step:

- Constraining bonds with hydrogens: Allows doubling the time step to 2 fs

- Constraining all bonds and angles involving hydrogen atoms: Enables further increase

- Hydrogen mass repartitioning: Allows increasing time step to 4 fs by redistributing mass from heavy atoms to bonded hydrogens [3]

Table 2: Time Step Selection Guidelines for MD Simulations

| Constraint Method | Typical Time Step | Accuracy Considerations | Computational Overhead |

|---|---|---|---|

| No constraints | 1 fs | Accurately captures all bond vibrations | Lowest |

| H-bond constraints | 2 fs | Requires LINCS or SHAKE algorithms | Moderate |

| All-bond constraints | 2-3 fs | May affect certain conformational changes | Moderate to high |

| Hydrogen mass repartitioning | 4 fs | Alters dynamics but preserves thermodynamics | Low |

Constraint Algorithms

To constrain bond lengths without affecting system dynamics and energetics, specialized algorithms are employed:

- SHAKE: Iterative algorithm that resets all bonds to constrained values sequentially until desired tolerance is achieved. Simple and stable, applicable to large molecules, but slower than alternatives and difficult to parallelize [3].

- LINCS: Linear constraint solver, 3-4 times faster than SHAKE and easier to parallelize. P-LINCS allows constraining all bonds in large molecules but is not suitable for constraining both bonds and angles [3].

- SETTLE: Very fast analytical solution for small molecules, widely used to constrain bonds in water molecules [3].

Implementation in MD Software Packages

Different MD software packages implement Verlet integration with varying specifications:

GROMACS offers multiple integration algorithms specified in the run parameter mdp file [3]:

integrator = md(leap-frog algorithm)integrator = md-vv(velocity Verlet algorithm)integrator = md-vv-avek(velocity Verlet with averaged kinetic energy)integrator = sd(accurate leap-frog stochastic dynamics)integrator = bd(Euler integrator for Brownian dynamics)

NAMD uses Verlet integration as its only available method, with parameters specified in the configuration file [3]:

timestep = 2.0(time step in femtoseconds)nonbondedFreq = 2(frequency of nonbonded evaluations)fullElectFrequency = 4(frequency of full electrostatic evaluations)

Applications in Drug Discovery and Pharmaceutical Development

Role in Modern Drug Development

MD simulations have become increasingly useful in the modern drug development process [1]. Key applications include:

- Target validation: MD studies provide important insights into the dynamics and function of identified drug targets such as sirtuins, RAS proteins, and intrinsically disordered proteins [1].

- Antibody design: MD facilitates evaluation of binding energetics and kinetics of ligand-receptor interactions [1].

- Membrane protein studies: MD enables the study of G-protein coupled receptors and ion channels in their biological lipid bilayer environment [1].

- Formulation development: MD assists in studying crystalline and amorphous solids, stability of amorphous drug formulations, and drug solubility [1].

Experimental Protocols

A typical MD simulation protocol for drug discovery applications involves these key steps [5] [1]:

System Preparation

- Obtain protein structure from Protein Data Bank or through homology modeling

- Place the biomolecule in an appropriate simulation box

- Add solvent molecules and ions to mimic physiological conditions

- Energy minimization to remove steric clashes

Equilibration Phase

- Gradually heat the system to target temperature (e.g., 274K for Argon simulations [5])

- Apply position restraints on solute atoms during initial equilibration

- Achieve stable temperature and pressure through controlled dynamics

Production Simulation

- Run extended simulation with Verlet integration (typically Velocity Verlet or Leap-Frog)

- Use time steps of 1-4 fs depending on constraints

- Simulate for nanoseconds to microseconds depending on system size and research question

- Save trajectories at regular intervals for analysis

Analysis Phase

- Calculate structural properties (RMSD, RMSF)

- Analyze binding energies and interactions

- Study conformational changes and dynamics

- Compare with experimental data for validation

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for MD Simulations

| Item | Function/Purpose | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Force Fields | Define potential energy functions governing atomic interactions | CHARMM, AMBER, GROMOS; include bonded and non-bonded interaction terms [1] |

| MD Software Packages | Provide simulation engines with integration algorithms | GROMACS, AMBER, NAMD, CHARMM; implement Verlet algorithms [1] |

| Solvation Models | Represent aqueous environment surrounding biomolecules | TIP3P, SPC, TIP4P water models; periodic boundary conditions [1] |

| Long-Range Electrostatic Methods | Handle electrostatic interactions beyond cut-off distance | Particle Mesh Ewald (PME), Particle-Particle Particle-Mesh; essential for accuracy [1] |

| Temperature/Pressure Couplers | Maintain constant temperature and pressure | Nosé-Hoover, Berendsen, Parrinello-Rahman algorithms; mimic laboratory conditions [1] |

| Visualization Tools | Analyze and visualize simulation trajectories | VMD, PyMOL, Chimera; enable structural analysis and figure generation |

| (E)-2-Butenyl-4-methyl-threonine | (E)-2-Butenyl-4-methyl-threonine, CAS:81135-57-1, MF:C9H17NO3, MW:187.24 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 9-Hydroxyspiro[5.5]undecan-3-one | 9-Hydroxyspiro[5.5]undecan-3-one, CAS:154464-88-7, MF:C11H18O2, MW:182.26 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Future Perspectives

With continuing advances in computing power, the role of MD simulations in facilitating the drug development process is likely to grow substantially [1]. Key developments include:

- Enhanced sampling methods: Improved algorithms for exploring configuration space more efficiently

- Force field improvements: More accurate parameterization for diverse molecular systems

- Hybrid quantum/classical methods: Combining accuracy of quantum mechanics with efficiency of classical MD

- Machine learning integration: Using neural networks to accelerate simulations and improve accuracy

- Large-scale simulations: Modeling increasingly complex systems such as entire viral envelopes or cellular components [1]

As these technical advancements mature, Verlet integration and its variants will continue to provide the fundamental numerical framework for propagating Newton's equations of motion in molecular systems, maintaining their position as the cornerstone of molecular dynamics simulations in pharmaceutical research and development.

The Verlet algorithm represents a cornerstone of molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, enabling researchers to numerically integrate Newton's equations of motion with exceptional stability and precision. Originally developed by Jean Baptiste Delambre in 1791, subsequently rediscovered multiple times, and formally established by Loup Verlet in the 1960s, this algorithm has revolutionized computational studies of biomolecular systems. Its mathematical formalism provides time-reversible integration with minimal computational overhead, making it particularly valuable for drug development professionals studying protein-ligand interactions, conformational changes, and thermodynamic properties. This technical guide examines the historical trajectory, mathematical foundations, and practical implementations of Verlet algorithms, with specific attention to their applications in modern molecular research and pharmaceutical development.

Molecular Dynamics (MD) has emerged as an indispensable methodology for simulating complex molecular systems, providing insights into structural biology, drug design, and materials science that are often inaccessible through experimental techniques alone [6]. At its core, MD solves Newton's equations of motion for atoms by iterating through small time steps, using numerical integration to predict new atomic positions and velocities based on calculated forces [7]. The revolutionary advances in computer technology since the first MD simulations in the late 1950s have been paralleled by algorithmic improvements, with the Verlet algorithm family standing as the most significant development in ensuring numerical stability and physical fidelity [6].

The Verlet integration scheme satisfies fundamental requirements for MD integration algorithms: accuracy in describing atomic motion, stability in conserving system energy and temperature, simplicity for programming implementation, speed in calculation, and economy in computing resources [7]. These characteristics have made Verlet algorithms the predominant choice for molecular dynamics programmers, particularly in pharmaceutical research where simulations of protein folding, ligand binding, and allosteric regulation provide critical insights for drug development [6].

Historical Development and Rediscovery

The mathematical foundations of what would become known as Verlet integration have experienced multiple independent discoveries throughout scientific history, reflecting its fundamental nature for solving second-order differential equations. This recurrent rediscovery pattern underscores the algorithm's intrinsic mathematical elegance and practical utility across diverse scientific domains.

Chronological Development Pathway

Table: Historical Timeline of Verlet Algorithm Development

| Year | Scientist | Contribution | Application Domain |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1791 | Jean Baptiste Delambre | First known use of the algorithm | Astronomical calculations |

| 1907 | Carl Størmer | Independent development | Trajectories of electrical particles in magnetic fields |

| 1909 | P. H. Cowell and A. C. C. Crommelin | Independent rediscovery | Computation of Halley's Comet orbit |

| 1967 | Loup Verlet | Formal derivation and popularization | Molecular dynamics simulations of classical fluids |

The algorithm's earliest known manifestation occurred in 1791 when French astronomer Jean Baptiste Delambre employed it for celestial calculations [2]. In the early 20th century, the method reappeared independently in the work of Carl Størmer (1907), who studied the trajectories of electrical particles in magnetic fields—an application that led to the alternative nomenclature "Størmer's method" [2]. Shortly thereafter, P. H. Cowell and A. C. C. Crommelin utilized the same mathematical approach in 1909 to compute the orbit of Halley's Comet with remarkable accuracy given the computational limitations of the era [2].

The algorithm entered its modern era when Loup Verlet derived and formalized it for molecular simulations in 1967, publishing his seminal work "Computer experiments on classical fluids. I. Thermodynamical properties of Lennard-Jones molecules" in Physical Review [8]. Verlet's derivation focused specifically on molecular dynamics applications, establishing the mathematical framework that would become foundational to computational chemistry and biomolecular simulation. His formulation used third-order Taylor expansions for atomic positions, both forward and backward in time, to achieve a discretization error of order Δtⴠwhile avoiding explicit velocity dependence in the position update [8].

The Rediscovery Pattern

The repeated independent discovery of this integration method across centuries and scientific disciplines highlights its fundamental mathematical nature. Each rediscovery occurred when researchers confronted the challenge of numerically integrating second-order differential equations without introducing significant energy drift or numerical instability [2]. The algorithm's symmetry properties, which confer time-reversibility and symplectic structure preservation, make it naturally suited for physical systems obeying conservation laws [2].

The modern prevalence of Verlet algorithms in molecular dynamics began with Verlet's 1967 publication, which coincided with the increasing availability of computational resources for scientific simulation [8]. Unlike previous discoverers, Verlet explicitly derived the method for molecular systems and analyzed its numerical stability, establishing it as the standard approach for MD simulations just as the field began rapid expansion into biological applications [8].

Mathematical Foundations

The mathematical derivation of the Verlet algorithm begins with Newton's equations of motion for conservative physical systems. For a system of N particles, the equations take the form Máº(t) = F(x(t)) = -∇V(x(t)), where M represents the mass matrix, x(t) denotes atomic positions, F is the force vector, and V is the potential energy function [2]. The Verlet algorithm provides a numerical solution to these equations by employing a central difference approximation to the second derivative.

Core Mathematical Derivation

The fundamental Verlet algorithm derivation starts with two third-order Taylor expansions for the positions r(t) of particles, one forward and one backward in time [8]:

Forward expansion: r(t+Δt) = r(t) + v(t)Δt + (1/2)a(t)Δt² + (1/6)b(t)Δt³ + O(Δtâ´)

Backward expansion: r(t-Δt) = r(t) - v(t)Δt + (1/2)a(t)Δt² - (1/6)b(t)Δt³ + O(Δtâ´)

Adding these two expressions eliminates the velocity and third-derivative terms, yielding the basic Verlet position update equation [8]: r(t+Δt) = 2r(t) - r(t-Δt) + a(t)Δt² + O(Δtâ´)

where a(t) = F(t)/m represents the acceleration computed from the force at time t. The remarkable feature of this formulation is that although third derivatives explicitly appear in the Taylor expansions, they cancel out in the summation, resulting in a local truncation error of order Δtⴠ[8].

Discretization Error and Numerical Stability

The discretization error of the Verlet algorithm merits particular attention. The local truncation error for positions is O(Δtâ´), while the global error is proportional to Δt² [2]. This favorable error characteristic arises from the time symmetry inherent in the method, which eliminates all odd-degree terms in the discretization [2]. The algorithm is symplectic, meaning it preserves the phase-space volume, a property crucial for long-term stability in molecular dynamics simulations [2].

Velocities can be approximated from the positions using the central difference formula: v(t) = [r(t+Δt) - r(t-Δt)] / (2Δt) + O(Δt²)

However, this velocity approximation has a larger error (O(Δt²)) compared to the position update, and it introduces numerical precision issues because it computes velocities as the difference between two similar-valued position vectors [8]. These limitations motivated the development of improved Verlet variants that handle velocities more accurately and consistently.

Verlet Algorithm Variants

The basic Verlet algorithm, while mathematically elegant, presents practical implementation challenges including moderate accuracy, non-self-starting behavior, and imprecise velocity handling. These limitations spurred the development of several variants that retain the core mathematical structure while improving numerical properties and implementation convenience.

Comparative Analysis of Verlet Algorithm Family

Table: Comparison of Verlet Algorithm Variants

| Algorithm | Key Equations | Accuracy | Storage Requirements | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basic Verlet | r(t+Δt) = 2r(t) - r(t-Δt) + a(t)Δt² | O(Δtâ´) positions, O(Δt²) velocities | 6N (two position sets) | Simple, modest storage | Not self-starting, imprecise velocities |

| Velocity Verlet | r(t+Δt) = r(t) + v(t)Δt + (1/2)a(t)Δt²v(t+Δt) = v(t) + (1/2)[a(t) + a(t+Δt)]Δt | O(Δtâ´) positions, O(Δt²) velocities | 9N (positions, velocities, accelerations) | Synchronous positions and velocities, self-starting | Additional force calculation |

| Leap-Frog | v(t+Δt/2) = v(t-Δt/2) + a(t)Δtr(t+Δt) = r(t) + v(t+Δt/2)Δt | O(Δtâ´) positions, O(Δt²) velocities | 6N (positions, half-step velocities) | Economical storage | Asynchronous positions and velocities |

Velocity Verlet Algorithm

The velocity Verlet algorithm addresses the primary limitations of the basic Verlet formulation by explicitly incorporating velocities and making them synchronous with positions [8]. This variant is currently the most widely used in production molecular dynamics codes, including popular packages like NAMD [9]. The algorithm decomposes into discrete steps:

- Position update: r(t+Δt) = r(t) + v(t)Δt + (1/2)a(t)Δt²

- Half-step velocity: v(t+Δt/2) = v(t) + (1/2)a(t)Δt

- Force computation: a(t+Δt) = -(1/m)∇V(r(t+Δt))

- Velocity completion: v(t+Δt) = v(t+Δt/2) + (1/2)a(t+Δt)Δt

This formulation requires 9N storage locations for positions, velocities, and accelerations but never needs simultaneous storage of values at two different times for any quantity [8]. The velocity Verlet algorithm provides the same trajectory as the basic Verlet method but with improved numerical properties and more convenient handling of velocities [7].

Leap-Frog Algorithm

The leap-frog algorithm represents an economical version that stores only one set of positions and one set of velocities while maintaining time-reversibility [7]. Its implementation follows:

- Velocity advance: v(t+Δt/2) = v(t-Δt/2) + a(t)Δt

- Position update: r(t+Δt) = r(t) + v(t+Δt/2)Δt

In this scheme, velocities "leap-frog" over positions, being defined at half-integer time steps while positions are defined at integer time steps [7]. If full-step velocities are required, they can be approximated as v(t) = [v(t-Δt/2) + v(t+Δt/2)]/2, though this introduces additional approximation error [7].

Practical Implementation and Research Applications

The transition from mathematical formulation to practical implementation requires careful consideration of numerical precision, force calculation efficiency, and integration with broader molecular dynamics workflows. The Velocity Verlet algorithm has become the de facto standard for production molecular dynamics codes across pharmaceutical and materials science research.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Components for Molecular Dynamics Implementation

| Component | Function | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| Integration Algorithm | Advances system through time steps | Velocity Verlet algorithm |

| Force Field | Computes potential energy and forces | CHARMM, AMBER, OPLS parameters |

| Thermostat | Regulates system temperature | Nose-Hoover thermostat, Langevin dynamics |

| Barostat | Maintains constant pressure | Andersen barostat, Parrinello-Rahman |

| Boundary Conditions | Mimics bulk environment | Periodic boundary conditions |

| Constraint Algorithms | Handles rigid bonds | SHAKE, LINCS, RATTLE |

| Parallelization Framework | Enables large-scale simulation | NAMD, GROMACS, AMBER |

Experimental Protocol: Velocity Verlet Implementation

Implementing the Velocity Verlet algorithm for molecular dynamics simulations follows a structured protocol that ensures numerical stability and physical accuracy:

Initialization:

- Set initial positions r(0) from experimental structures or previous simulations

- Initialize velocities v(0) from Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution at target temperature

- Compute initial forces F(0) = -∇V(r(0)) and accelerations a(0) = F(0)/m

Main Integration Loop:

- Update positions: r(t+Δt) = r(t) + v(t)Δt + (1/2)a(t)Δt²

- Calculate half-step velocities: v(t+Δt/2) = v(t) + (1/2)a(t)Δt

- Compute new forces: F(t+Δt) = -∇V(r(t+Δt))

- Calculate new accelerations: a(t+Δt) = F(t+Δt)/m

- Complete velocity update: v(t+Δt) = v(t+Δt/2) + (1/2)a(t+Δt)Δt

Property Calculation:

A critical implementation consideration involves the conservation of total energy E = K + V, where K represents kinetic energy and V potential energy. Monitoring energy conservation provides the most important verification that the MD simulation is proceeding correctly [8]. For biological systems, typical time steps range from 1-2 femtoseconds, constrained by the highest frequency vibrations (typically C-H bond stretches) [7].

Advanced Implementation: External Field Integration

Recent extensions to the Velocity Verlet algorithm have incorporated capacity for external fields, significantly expanding its application scope. For instance, researchers have implemented magnetic field forces within the NAMD package, modifying the algorithm to include Lorentz force contributions [9]. The implementation follows the Velocity Verlet structure but adds the magnetic force component Fₘ = q(v × B) to the total force calculation, where q represents charge, v is velocity, and B is the magnetic field vector [9].

This extension required careful treatment of the velocity dependence in the magnetic force, which necessitates implicit or iterative solution methods at each time step. The successful implementation enabled investigation of magnetic field effects on biomolecular systems, particularly water structure and ion behavior near proteins [9]. Such algorithmic extensions demonstrate the flexibility of the Verlet framework for incorporating increasingly complex physical interactions relevant to pharmaceutical research, including electric fields, shear flows, and other non-equilibrium conditions.

The historical journey of the Verlet algorithm—from Delambre's astronomical calculations to Verlet's molecular dynamics formalism—exemplifies how fundamental mathematical methods transcend their original domains to enable scientific progress across disciplines. The algorithm's symplectic nature, time-reversibility, and numerical stability have established it as the integration method of choice for molecular simulations, particularly in pharmaceutical research where accurate sampling of conformational space is essential for drug discovery.

The continued evolution of Verlet algorithms, including the velocity Verlet and leap-frog variants, addresses the demanding requirements of modern biomolecular simulation: energy conservation over nanosecond-to-microsecond timescales, efficient utilization of parallel computing architectures, and consistent sampling of thermodynamic ensembles. As molecular dynamics continues expanding into new research domains—including machine learning force fields, enhanced sampling techniques, and multi-scale modeling—the mathematical foundation established by Delambre, Størmer, Cowell, Crommelin, and Verlet remains central to extracting physically meaningful insights from computational experiments.

The central difference approximation is a foundational numerical method for estimating derivatives of functions, serving as the mathematical cornerstone of the Verlet integration algorithm. In molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, this principle enables the stable and efficient computation of particle trajectories by solving Newton's equations of motion. The Verlet algorithm, derived from this approximation, is ubiquitously employed in MD simulations within pharmaceutical research and material science, facilitating the study of complex molecular systems and their time-evolving properties. Its numerical stability and time-reversibility make it particularly suited for long-timescale simulations, such as those analyzing protein folding or drug-receptor interactions [2]. By providing a deterministic framework for modeling molecular interactions, the Verlet algorithm allows researchers to bridge atomic-level interactions with macroscopic observables like free energy and diffusion rates, which are critical for rational drug design [10].

Mathematical Foundation

Derivation of the Central Difference Approximation

The central difference approximation for the second derivative is derived from the Taylor series expansions of a function ( x(t) ) around time ( t ). The forward and backward Taylor expansions are given by:

[ x(t + \Delta t) = x(t) + v(t)\Delta t + \frac{a(t)\Delta t^2}{2} + \frac{b(t)\Delta t^3}{6} + \mathcal{O}(\Delta t^4) ]

[ x(t - \Delta t) = x(t) - v(t)\Delta t + \frac{a(t)\Delta t^2}{2} - \frac{b(t)\Delta t^3}{6} + \mathcal{O}(\Delta t^4) ]

where:

- ( x(t) ) represents the position at time ( t )

- ( v(t) = \dot{x}(t) ) is the velocity

- ( a(t) = \ddot{x}(t) ) is the acceleration

- ( b(t) = \dot{a}(t) ) is the third derivative

- ( \Delta t ) is the finite time step [2]

Adding these two expansions cancels the odd-order terms, including the velocity term, yielding:

[ x(t + \Delta t) + x(t - \Delta t) = 2x(t) + a(t)\Delta t^2 + \mathcal{O}(\Delta t^4) ]

Rearranging this expression isolates the acceleration term:

[ \frac{x(t + \Delta t) - 2x(t) + x(t - \Delta t)}{\Delta t^2} = a(t) + \mathcal{O}(\Delta t^2) ]

This establishes the central difference approximation for the second derivative, with a truncation error of order ( \Delta t^2 ). The cancellation of odd-order terms confers valuable numerical stability and time-reversibility properties to algorithms based on this formulation [2].

Connection to Newton's Equations of Motion

In molecular dynamics, particle motion is governed by Newton's second law:

[ mi \frac{d^2\mathbf{r}i}{dt^2} = \mathbf{F}_i ]

where:

- ( m_i ) is the mass of particle ( i )

- ( \mathbf{r}_i ) is its position vector

- ( \mathbf{F}_i ) is the force acting on it [11]

The force is derived from the potential energy function ( V ) through the relationship:

[ \mathbf{F}i = -\frac{\partial V}{\partial \mathbf{r}i} ]

Replacing the continuous second derivative with its central difference approximation produces the discretized equation of motion:

[ mi \frac{\mathbf{r}i(t + \Delta t) - 2\mathbf{r}i(t) + \mathbf{r}i(t - \Delta t)}{\Delta t^2} = \mathbf{F}_i(t) ]

This formulation provides the mathematical basis for the Verlet algorithm, enabling the numerical integration of particle trajectories in discrete time steps [11] [2].

The Verlet Integration Algorithm

Original Verlet Algorithm

The original Verlet algorithm follows directly from the central difference approximation. Solving the discretized equation of motion for the future position yields the update equation:

[ \mathbf{r}(t + \Delta t) = 2\mathbf{r}(t) - \mathbf{r}(t - \Delta t) + \frac{\mathbf{F}(t)}{m} \Delta t^2 ]

This formulation possesses several notable properties:

- It is time-reversible, mirroring the underlying physical laws

- It preserves the symplectic form on phase space, ensuring excellent energy conservation

- Its global error in position is of order ( \Delta t^3 ) [2] [12]

Despite these advantages, the original algorithm has practical limitations. It is not self-starting, requiring positions from two previous time steps. Velocity calculation is also problematic, as it must be estimated indirectly using:

[ \mathbf{v}(t) = \frac{\mathbf{r}(t + \Delta t) - \mathbf{r}(t - \Delta t)}{2\Delta t} ]

This approach suffers from numerical precision loss because it computes velocity as the difference between two similar-valued positions [12].

Velocity Verlet Variant

The velocity Verlet algorithm addresses these limitations while maintaining mathematical equivalence. It provides a self-starting formulation that explicitly tracks velocities:

[ \mathbf{r}(t + \Delta t) = \mathbf{r}(t) + \mathbf{v}(t)\Delta t + \frac{1}{2}\frac{\mathbf{F}(t)}{m} \Delta t^2 ]

[ \mathbf{v}(t + \Delta t) = \mathbf{v}(t) + \frac{\mathbf{F}(t) + \mathbf{F}(t + \Delta t)}{2m} \Delta t ]

This variant minimizes roundoff errors and is now widely implemented in production MD software like GROMACS [11] [12]. The algorithm proceeds in two phases per time step: position update followed by force computation and velocity update.

Diagram Title: Velocity Verlet Integration Workflow

Discretization Error Analysis

The Verlet algorithm's numerical accuracy stems from the cancellation of error terms in the central difference approximation. The following table summarizes its error characteristics:

| Component | Error Order | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Position (Local) | ( \mathcal{O}(\Delta t^4) ) | Error per time step in position |

| Position (Global) | ( \mathcal{O}(\Delta t^3) ) | Accumulated error over simulation |

| Velocity (Global) | ( \mathcal{O}(\Delta t^2) ) | Error in velocity estimation |

| Energy Conservation | Excellent | Due to symplectic property [2] |

The algorithm's stability is constrained by the time step ( \Delta t ), which must be sufficiently small to resolve the highest frequency motions in the system, particularly bond vibrations involving hydrogen atoms. In practice, this limits time steps to approximately 2 femtoseconds (fs) unless constraint algorithms are employed [11].

Implementation in Molecular Dynamics

Complete MD Integration Workflow

A complete molecular dynamics simulation integrates the Verlet algorithm with force computation and auxiliary procedures. The following workflow illustrates a single MD cycle:

Diagram Title: Complete MD Integration Cycle

Force Computation and Neighbor Searching

The force calculation phase dominates computational expense in MD simulations. Forces arise from various contributions:

- Non-bonded interactions: Lennard-Jones and Coulomb potentials between atom pairs

- Bonded interactions: Bond stretching, angle bending, and torsional potentials

- Restraints and external forces: Position restraints, pulling forces [11]

To optimize performance, MD codes like GROMACS employ neighbor searching algorithms with a buffered Verlet list. This approach creates a list of atom pairs within a cut-off radius ( r\ell = rc + rb ), where ( rc ) is the interaction cut-off and ( r_b ) is a safety buffer. The list is updated periodically rather than at every step, significantly reducing computational overhead [11].

The pair list generation employs a cluster-based approach where groups of 4-8 particles are processed together, improving computational efficiency on modern hardware with SIMD (Single Instruction Multiple Data) capabilities. Dynamic pair list pruning further optimizes performance by removing pairs that move beyond the interaction range between full list updates [11].

Energy Drift and Buffer Optimization

A critical consideration in Verlet-based MD is energy drift caused by particles diffusing into the interaction zone between list updates. The probability of this occurrence depends on the buffer size ( r_b ), time step ( \Delta t ), and particle displacement statistics.

For a canonical (NVT) ensemble, the atomic displacement distribution along one dimension follows a Gaussian with variance:

[ \sigma^2 = t^2 kB T \left( \frac{1}{m1} + \frac{1}{m_2} \right) ]

where ( k_B ) is Boltzmann's constant and ( T ) is temperature [11]. Modern MD packages can automatically determine the optimal buffer size given a tolerance for energy drift, typically targeting ~0.005 kJ/mol/ps per particle [11].

Applications in Drug Development

Solubility Prediction Framework

Molecular dynamics simulations employing Verlet integration have enabled significant advances in predicting key pharmaceutical properties. A recent study demonstrated the application of MD-derived properties for predicting aqueous solubility—a critical factor in drug bioavailability [10].

The research compiled a dataset of 211 drugs from diverse classes, conducted MD simulations using GROMACS, and extracted ten MD-derived properties as features for machine learning models. The following table summarizes the key molecular dynamics properties influencing drug solubility:

| Property | Symbol | Role in Solubility Prediction |

|---|---|---|

| Octanol-Water Partition Coefficient | logP | Measures lipophilicity/hydrophobicity |

| Solvent Accessible Surface Area | SASA | Quantifies surface exposed to solvent |

| Coulombic Interaction Energy | Coulombic_t | Electrostatic solute-solvent interactions |

| Lennard-Jones Interaction Energy | LJ | Van der Waals solute-solvent interactions |

| Estimated Solvation Free Energy | DGSolv | Thermodynamic driving force for dissolution |

| Root Mean Square Deviation | RMSD | Measures conformational flexibility |

| Average Solvation Shell Occupancy | AvgShell | Quantifies local solvent organization [10] |

Experimental Protocol for Solubility Prediction

Methodology:

- System Preparation: Obtain initial coordinates and generate topology files using the GROMOS 54a7 force field

- Simulation Setup: Conduct MD simulations in the isothermal-isobaric (NPT) ensemble using GROMACS

- Property Extraction: Calculate ten MD-derived properties from production trajectories

- Feature Selection: Apply statistical analysis to identify most influential properties

- Model Training: Employ ensemble machine learning algorithms (Random Forest, Extra Trees, XGBoost, Gradient Boosting) to predict logarithmic solubility (logS) [10]

Results: The Gradient Boosting algorithm achieved superior performance with a predictive R² of 0.87 and RMSE of 0.537 on the test set, demonstrating that MD-derived properties have comparable predictive power to traditional structural descriptors [10].

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential computational tools and their functions in molecular dynamics studies for drug development:

| Research Reagent | Function in MD Simulation |

|---|---|

| GROMACS Software Package | Molecular dynamics simulation engine with Verlet integration [10] |

| GROMOS 54a7 Force Field | Mathematical representation of interatomic potentials [10] |

| Solvent Water Model | Explicit representation of aqueous environment |

| Thermodynamic Ensemble (NPT) | Maintains constant Number of particles, Pressure, and Temperature [10] |

| Verlet Neighbor Search | Efficient algorithm for non-bonded pair list generation [11] |

| Machine Learning Algorithms (GBR, XGBoost) | Predictive modeling of solubility from MD features [10] |

Advancements and Future Directions

The integration of Verlet-based molecular dynamics with data science approaches represents the cutting edge of computational drug discovery. Current research focuses on addressing several key challenges:

- Trajectory Databases: Initiatives are underway to create standardized repositories of MD simulations for various biomolecular systems, enabling meta-analyses and machine learning applications [13]

- FAIR Data Principles: Ensuring simulations are Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable represents a paradigm shift from traditional isolated simulation approaches [13]

- Hybrid Methodologies: Combining Verlet integration with machine learning potential energy surfaces promises to enhance both accuracy and efficiency [10] [13]

These developments highlight the evolving role of the central difference approximation and Verlet algorithm in next-generation molecular simulation frameworks. As MD simulations generate increasingly large volumes of trajectory data, robust numerical integrators remain essential for producing reliable dynamics that can inform pharmaceutical development through advanced data science techniques [13].

The Verlet algorithm is a foundational numerical integration method central to Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations, which are critical computational tools in fields ranging from drug development to materials science. It is used to solve Newton's equations of motion for a system of interacting particles, enabling the study of thermodynamic properties, structural changes, and dynamic processes at the atomic level [14] [2]. The algorithm's significance stems from its numerical stability and its ability to preserve important physical properties of continuous dynamic systems over long simulation times, even when discretized with a finite time step [2]. For molecular dynamics research, these characteristics—time-reversibility, symplectic nature, and energy conservation—are not merely mathematical curiosities; they are essential for producing physically meaningful and reliable simulation data that can guide scientific discovery and product development, including the design of novel pharmaceutical compounds.

Mathematical Formulation of the Verlet Algorithm

Core Integration Scheme

The standard Verlet integrator is derived from a central difference approximation to the second derivative. For a second-order differential equation of the type (\ddot{\mathbf{x}}(t) = \mathbf{A}(\mathbf{x}(t))), where (\mathbf{A}) is the acceleration (typically force divided by mass), the position at the next time step (\mathbf{x}_{n+1}) is calculated from the current and previous positions [2]:

[ \mathbf{x}{n+1} = 2\mathbf{x}n - \mathbf{x}{n-1} + \mathbf{a}n \Delta t^2 ] where (\mathbf{a}n = \mathbf{A}(\mathbf{x}n)), and (\Delta t) is the time step [2].

A more commonly used variant, the Velocity Verlet algorithm, explicitly calculates velocities and is self-starting. Its integration steps are as follows [15]:

- Update positions: (\mathbf{x}(t + \Delta t) = \mathbf{x}(t) + \mathbf{v}(t) \Delta t + \frac{1}{2} \mathbf{a}(t) \Delta t^2)

- Calculate forces and accelerations (\mathbf{a}(t + \Delta t)) at the new positions.

- Update velocities: (\mathbf{v}(t + \Delta t) = \mathbf{v}(t) + \frac{\mathbf{a}(t) + \mathbf{a}(t + \Delta t)}{2} \Delta t)

Discretization Error and Accuracy

The local truncation error of the Verlet integrator is of the order (O(\Delta t^4)) for positions and (O(\Delta t^2)) for velocities [2]. This favorable error profile arises because the central difference approximation cancels out the odd-order terms in the Taylor expansion [2]. The following table summarizes the error characteristics and computational cost.

Table 1: Discretization error and computational profile of the Verlet algorithm.

| Aspect | Description | Mathematical Expression |

|---|---|---|

| Position Update Error | Local truncation error is fourth-order [2]. | (O(\Delta t^4)) |

| Velocity Update Error | Local truncation error is second-order [2]. | (O(\Delta t^2)) |

| Global Error | Error over a fixed time span is one order lower [2]. | Positions: (O(\Delta t^2)) |

| Computational Cost | Requires one force calculation per time step, comparable to simple Euler method [2]. | (O(N)) per step (for N particles) |

Key Properties: Theoretical Foundations and Practical Implications

Time-Reversibility

Time-reversibility is a fundamental property of Newton's equations of motion. The Verlet algorithm, by virtue of its symmetric formulation, preserves this property in its discrete integration process [2]. If the signs of all velocities and the time direction are reversed, the system will retrace its trajectory back through the sequence of positions it came from.

This property is intrinsically linked to the algorithm's stability. Small errors do not tend to accumulate in a one-directional, destabilizing manner, which is crucial for long-term integration. The Velocity Verlet algorithm's sequence of operations—updating positions, then forces, then velocities—is specifically designed to maintain this symmetry in time [15].

Symplectic Nature

The Verlet integrator is symplectic, meaning it preserves the symplectic form on phase space [2]. In practical terms, this guarantees that the computed trajectory conserves the total energy and other invariants of the Hamiltonian system with remarkable accuracy over long simulation periods, even if there is a small phase error in the oscillations [16] [2].

This is a significant advantage over non-symplectic integrators (e.g., Runge-Kutta), which may exhibit a steady drift in the total system energy over time, leading to unphysical behavior [14]. The symplectic property ensures that the energy fluctuates around a stable mean value rather than diverging [2].

Energy Conservation

In the NVE (microcanonical) ensemble, where particle number, volume, and total energy are conserved, the Velocity Verlet algorithm demonstrates excellent long-term stability for the total energy [14]. The energy is not perfectly constant but oscillates within a small, bounded margin around the true value. The amplitude of these oscillations is highly dependent on the chosen time step [15].

Table 2: Summary of the three key properties of the Verlet algorithm.

| Property | Theoretical Foundation | Practical Implication in MD |

|---|---|---|

| Time-Reversibility | Symmetric form from central difference approximation [2]. | Enhanced numerical stability for long simulations [2]. |

| Symplectic Nature | Preserves the symplectic form on phase space [16] [2]. | Prevents long-term energy drift; essential for correct thermodynamic sampling [16] [14]. |

| Energy Conservation | Bounded energy oscillations due to symplectic property [14] [15]. | Enables reliable NVE ensemble simulations; accuracy depends on time step choice [14]. |

Experimental Protocols and Validation

Methodology for Validating Energy Conservation

A standard protocol for validating the energy-conserving properties of the Verlet algorithm involves simulating a simple, well-understood system and monitoring its total energy over time.

System Setup:

- Model System: A 1D harmonic oscillator or a simple pair of particles interacting via a spring potential, as this has a known analytical solution [15].

- Initial Conditions: Define initial particle positions and velocities. For a spring system, one can start with particles displaced from their equilibrium distance [15].

- Potential and Force: Use a Hookean spring potential, ( V(r) = \frac{1}{2}k(r - r0)^2 ), where ( k ) is the spring constant and ( r0 ) is the equilibrium distance. The force is ( F = -\nabla V ) [15].

Simulation Procedure:

- Integration: Apply the Velocity Verlet algorithm to update particle positions and velocities over a large number of steps (e.g., 1000) [15].

- Energy Calculation: At each time step, compute the total energy ( E{total} = E{kinetic} + E_{potential} ) [15].

- Analysis: Plot the total energy as a function of simulation time. A high-quality, symplectic integrator will show stable oscillations without a secular drift [15].

Workflow for a Molecular Dynamics Simulation

The following diagram illustrates the standard sequence of operations in a complete MD simulation step using the Velocity Verlet integrator.

Figure 1: A single iteration of an MD simulation using the Velocity Verlet algorithm.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Components for MD Simulations

Table 3: Key software and computational reagents used in modern Molecular Dynamics simulations.

| Tool/Component | Function | Example Implementations |

|---|---|---|

| MD Engine | Core software that performs the simulation, handling integration, force calculations, and neighbor lists. | LAMMPS [17], ASE (Atomic Simulation Environment) [14], GROMACS, AMBER. |

| Force Field | A set of empirical potentials and parameters that describe the interatomic forces. | Lennard-Jones potential [16], Spring potential [15], AMBER, CHARMM. |

| Integrator | The numerical algorithm that solves the equations of motion. | Velocity Verlet [14] [15], Langevin (for NVT ensemble) [14]. |

| Neighbor List | An algorithmic optimization to efficiently identify particles within interaction range, reducing computation from (O(N^2)) [15]. | Hierarchical grid algorithm [17], Linked cell method [17]. |

| Analysis & Visualization | Tools for processing trajectory data to compute properties and generate visual representations. | MDAnalysis, MDTraj [15], VMD. |

| 1,1-Difluoro-1,3-diphenylpropane | 1,1-Difluoro-1,3-diphenylpropane | |

| Methyl 2-(2-methoxyethoxy)acetate | Methyl 2-(2-methoxyethoxy)acetate|148.16 g/mol | Methyl 2-(2-methoxyethoxy)acetate (CAS 17640-28-7) is a versatile ester and glycol ether solvent for organic synthesis and energy storage research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

Advanced Optimizations and Recent Developments

Optimized Verlet-like Algorithms

Research continues to refine the core Verlet algorithm. One approach involves an extended decomposition scheme that introduces a free parameter, which is optimized to minimize the influence of truncated terms [16]. These optimized algorithms are more efficient than the original Verlet versions while remaining symplectic and time-reversible, leading to improved accuracy at the same computational cost, as demonstrated in simulations of Lennard-Jones fluids [16].

Addressing Limitations in Polydisperse Systems

Recent work has identified a subtle flaw in the standard velocity-Verlet implementation within Discrete Element Method (DEM) codes when simulating systems with large particle-size ratios (e.g., in granular flows). The half-step difference between position and velocity updates can cause unphysical pendular motion of small particles trapped between larger ones [17].

An improved velocity-Verlet integration has been proposed to correct this. The key modification is to use the average velocity over the interval ([t, t+\Delta t]) for the position update, which more accurately represents the mean velocity during that step and eliminates the spurious oscillations [17]. This improvement has been integrated into the developer version of LAMMPS, enhancing simulation accuracy for systems with large size ratios [17].

Selecting the Time Step and Other Parameters

The choice of time step ((\Delta t)) is a critical trade-off between computational efficiency and physical accuracy [14] [15].

Table 4: Guidelines for selecting the MD simulation time step.

| System Type | Recommended Time Step | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Metallic Systems | ~5.0 fs [14] | A good balance for systems with moderate atomic masses and bond strengths. |

| Systems with Light Atoms (H) or Strong Bonds (C) | 1-2 fs [14] | Higher frequency vibrations require a smaller time step to maintain stability. |

| General Guideline | Must be small relative to the highest frequency vibration [15]. | A too-large time step causes a dramatic energy increase and system instability [14]. |

Furthermore, for simulations involving large size ratios, careful selection of contact stiffness and damping models is also crucial to avoid unphysical behavior and ensure accurate results [17].

The Verlet algorithm, particularly its Velocity Verlet variant, remains a cornerstone of molecular dynamics simulations due to its robust numerical properties: time-reversibility, symplectic nature, and excellent energy conservation. These characteristics are indispensable for generating reliable, physically meaningful data in scientific research and industrial applications, such as drug discovery. While the core algorithm is well-established, ongoing research continues to develop optimized and problem-specific variants, ensuring its relevance and accuracy for increasingly complex simulation challenges. As computational power grows and scientists tackle new domains, a thorough understanding of these foundational integration schemes is paramount to avoid subtle inaccuracies and push the boundaries of what molecular dynamics can reveal.

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation represents a cornerstone technique in computational chemistry, physics, and drug development, enabling researchers to probe the temporal evolution of molecular systems at atomic resolution. The Verlet algorithm, first introduced by Loup Verlet in 1967 for computer experiments on classical fluids, has emerged as one of the most fundamental and widely-used numerical integration methods in this field [18] [12]. Its significance stems from an exceptional combination of numerical stability, computational efficiency, and desirable physical properties including time-reversibility and symplecticity (preservation of the geometric structure of Hamiltonian systems) [2]. Within the broader thesis of understanding molecular dynamics algorithms, analyzing the global error properties of integration schemes—specifically the third-order accuracy for position and second-order accuracy for velocity in the Verlet method—provides critical insights for researchers seeking to balance computational expense with numerical precision in simulating biomolecular systems, materials science, and drug-target interactions.

Mathematical Foundation of Verlet Integration

Fundamental Algorithm Derivation

The Verlet algorithm integrates Newton's equations of motion for a system of N particles governed by conservative forces derived from a potential function V(x). For a second-order differential equation of the type:

[ \ddot{\mathbf{x}}(t) = \mathbf{A}(\mathbf{x}(t)) ]

where (\mathbf{A}(\mathbf{x}(t)) = \mathbf{M}^{-1}\mathbf{F}(\mathbf{x}(t))) and (\mathbf{F}(\mathbf{x}) = -\nabla V(\mathbf{x})), the Verlet method employs a central difference approximation to the second derivative [2]:

[ \frac{\Delta^2\mathbf{x}n}{\Delta t^2} = \frac{\mathbf{x}{n+1} - 2\mathbf{x}n + \mathbf{x}{n-1}}{\Delta t^2} = \mathbf{a}n = \mathbf{A}(\mathbf{x}n) ]

This leads to the position update equation in the Størmer-Verlet form:

[ \mathbf{x}{n+1} = 2\mathbf{x}n - \mathbf{x}{n-1} + \mathbf{a}n \Delta t^2 ]

where (\mathbf{x}n \approx \mathbf{x}(tn)) represents the position at time (tn = t0 + n\Delta t), and (\Delta t) is the integration time step [2].

Velocity Formulation

Although the basic Verlet algorithm does not explicitly include velocities, they can be derived from the position trajectory:

[ \mathbf{v}n = \frac{\mathbf{x}{n+1} - \mathbf{x}_{n-1}}{2\Delta t} ]

However, this velocity calculation suffers from numerical precision issues due to the difference between two quantities of similar magnitude [12]. The velocity Verlet algorithm, a mathematically equivalent formulation, addresses this limitation by explicitly incorporating velocity updates:

[ \mathbf{x}(t + \Delta t) = \mathbf{x}(t) + \mathbf{v}(t)\Delta t + \frac{1}{2}\mathbf{a}(t)\Delta t^2 ]

[ \mathbf{v}(t + \Delta t) = \mathbf{v}(t) + \frac{1}{2}[\mathbf{a}(t) + \mathbf{a}(t + \Delta t)]\Delta t ]

This self-starting algorithm minimizes roundoff errors while maintaining the same error properties as the original Verlet method [12] [19].

Global Error Analysis Methodology

Taylor Series Expansion Framework

The global error analysis of the Verlet algorithm derives from Taylor series expansions of position around time t. The forward and reverse expansions are given by:

[ \mathbf{x}(t + \Delta t) = \mathbf{x}(t) + \mathbf{v}(t)\Delta t + \frac{\mathbf{a}(t)\Delta t^2}{2} + \frac{\mathbf{b}(t)\Delta t^3}{6} + \mathcal{O}(\Delta t^4) ]

[ \mathbf{x}(t - \Delta t) = \mathbf{x}(t) - \mathbf{v}(t)\Delta t + \frac{\mathbf{a}(t)\Delta t^2}{2} - \frac{\mathbf{b}(t)\Delta t^3}{6} + \mathcal{O}(\Delta t^4) ]

where (\mathbf{v} = \dot{\mathbf{x}}), (\mathbf{a} = \ddot{\mathbf{x}}), and (\mathbf{b} = \dddot{\mathbf{x}}) represent velocity, acceleration, and jerk, respectively [2].

Error Order Determination

Adding the forward and reverse Taylor expansions produces the Verlet position update:

[ \mathbf{x}(t + \Delta t) = 2\mathbf{x}(t) - \mathbf{x}(t - \Delta t) + \mathbf{a}(t)\Delta t^2 + \mathcal{O}(\Delta t^4) ]

The cancellation of the third-order terms ((\Delta t^3)) results in a local truncation error of (\mathcal{O}(\Delta t^4)) for the position. However, as this equation represents a difference scheme with cumulative error over multiple steps, the global error for position becomes third-order ((\mathcal{O}(\Delta t^3))) [12] [2].

For velocity, subtracting the reverse expansion from the forward expansion yields:

[ \mathbf{v}(t) = \frac{\mathbf{x}(t + \Delta t) - \mathbf{x}(t - \Delta t)}{2\Delta t} - \frac{\mathbf{b}(t)\Delta t^2}{6} + \mathcal{O}(\Delta t^3) ]

The leading error term of order (\Delta t^2) translates to a global error for velocity of second-order ((\mathcal{O}(\Delta t^2))) [12].

Table 1: Global Error Properties of Verlet Integration

| Variable | Local Truncation Error | Global Error | Key Mathematical Property |

|---|---|---|---|

| Position | (\mathcal{O}(\Delta t^4)) | (\mathcal{O}(\Delta t^3)) | Third-order accuracy |

| Velocity | (\mathcal{O}(\Delta t^2)) | (\mathcal{O}(\Delta t^2)) | Second-order accuracy |

| Algorithm | Time-symmetric | Time-reversible | Symplectic |

Comparative Analysis of Verlet Integration Variants

Algorithmic Implementations and Their Error Profiles

Various implementations of the Verlet algorithm have been developed to address specific numerical challenges while maintaining the core error properties:

The original Verlet algorithm (1967) provides excellent numerical stability and time-reversibility but suffers from numerical precision issues in velocity calculation and is not self-starting [18] [12]. The velocity Verlet algorithm (Swope, 1982) eliminates roundoff errors in velocity computation by explicitly including velocities in the update steps, making it self-starting while maintaining the same global error order [12] [19]. RATTLE (1983) extends Verlet integration to handle holonomic constraints through Lagrange multipliers, preserving the error order while enabling bond length and angle constraints [18]. Optimized Verlet-like algorithms (Omelyan, 2002) introduce free parameters to minimize the influence of truncated terms, achieving improved accuracy at the same computational cost while maintaining the fundamental error bounds [20].

Table 2: Comparison of Verlet Integration Variants

| Algorithm | Position Error | Velocity Error | Key Features | Computational Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Original Verlet | (\mathcal{O}(\Delta t^3)) | (\mathcal{O}(\Delta t^2)) | Excellent stability, not self-starting | Low |

| Velocity Verlet | (\mathcal{O}(\Delta t^3)) | (\mathcal{O}(\Delta t^2)) | Self-starting, minimal roundoff error | Low (2 force evaluations/step) |

| RATTLE | (\mathcal{O}(\Delta t^3)) | (\mathcal{O}(\Delta t^2)) | Handles constraints, time-reversible | Moderate |

| Beeman | (\mathcal{O}(\Delta t^3)) | (\mathcal{O}(\Delta t^2)) | Better energy conservation | Moderate |

| Optimized Verlet-like | (\mathcal{O}(\Delta t^3)) | (\mathcal{O}(\Delta t^2)) | Enhanced accuracy, parameter-controlled | Low |

Multiple Time Stepping and Resonance Instabilities

Advanced implementations of Verlet integration, particularly Verlet-I/r-RESPA (Reversible Reference System Propagator Algorithms), employ multiple time stepping to enhance computational efficiency for systems with forces acting at different time scales. However, these methods can suffer from linear and nonlinear resonance instabilities when the longest time step approaches half the period of the fastest motion in the system [21].

Mollified Verlet-I/r-RESPA (MOLLY) methods overcome these instabilities by applying mollification (smoothing) functions to the slow forces, allowing for time steps up to 50% longer than standard Verlet-I/r-RESPA for a given energy drift [21]. This extension maintains the fundamental error properties while improving numerical stability for complex biomolecular systems with steep potential gradients.

Experimental Protocols for Error Validation

Harmonic Oscillator Validation Methodology

The implementation and error properties of Verlet integration can be rigorously validated using the harmonic oscillator model, which provides an exact analytical solution for comparison [19]. The protocol involves:

System Setup: A one-dimensional harmonic oscillator with mass μ and force constant k, governed by the potential energy function (V(x) = \frac{1}{2}k(x - x_{eq})^2). Newton's equation of motion for this system is (\ddot{x}(t) = -\omega^2 x(t)), where (\omega = \sqrt{k/\mu}) is the oscillator frequency [19].

Initial Conditions: Initial displacement (x(0) = A\sin(\phi) + x{eq}) and initial velocity (v(0) = A\omega\cos(\phi)), where A is the oscillation amplitude, φ is the initial phase, and (x{eq}) is the equilibrium position.

Analytical Solution: The exact position as a function of time is given by (x(t) = A\sin(\omega t + \phi) + x_{eq}).

Numerical Integration: Application of the Velocity Verlet algorithm with position update: [ x(t + \Delta t) = x(t) + v(t)\Delta t + \frac{1}{2}a(t)\Delta t^2 ] and velocity update: [ v(t + \Delta t) = v(t) + \frac{1}{2}[a(t) + a(t + \Delta t)]\Delta t ] where (a(t) = -\omega^2(x(t) - x_{eq})) [19].

Error Quantification: Calculation of the root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) between numerical and analytical trajectories: [ \text{RMSD} = \sqrt{\frac{1}{N}\sum{i=1}^N (x{\text{numeric}}(ti) - x{\text{analytic}}(t_i))^2} ] across N time steps to verify the theoretical third-order error scaling for position.