Temperature-Dependent Diffusion Coefficients: From Arrhenius Theory to Molecular Dynamics Validation in Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on utilizing Arrhenius plots and Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations to study temperature-dependent diffusion coefficients.

Temperature-Dependent Diffusion Coefficients: From Arrhenius Theory to Molecular Dynamics Validation in Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on utilizing Arrhenius plots and Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations to study temperature-dependent diffusion coefficients. It covers the foundational theory of the Arrhenius equation, practical methodologies for extracting activation energies and pre-exponential factors from MD data, strategies for troubleshooting non-Arrhenius behavior and optimization of computational parameters, and techniques for validating simulation results against experimental data. By integrating theoretical concepts with practical computational applications, this resource aims to enhance the accuracy and reliability of diffusion studies in materials science and drug development.

Understanding the Arrhenius Equation and Diffusion Fundamentals

Theoretical Basis of the Arrhenius Equation for Diffusion

The Arrhenius equation is a fundamental principle in physical chemistry that describes the temperature dependence of reaction rates and various kinetic processes, including atomic and molecular diffusion. Within the context of temperature-dependent diffusion coefficient research, particularly in Molecular Dynamics (MD) studies, this equation provides the theoretical foundation for understanding and predicting how diffusion evolves with thermal energy. The core relationship is expressed as: ( k = A e^{-Ea / RT} ), where ( k ) represents the rate constant, ( A ) is the pre-exponential factor (or frequency factor), ( Ea ) is the activation energy, ( R ) is the universal gas constant, and ( T ) is the absolute temperature [1]. When applied to diffusion, the rate constant ( k ) is replaced by the diffusion coefficient ( D ), leading to the form: ( D(T) = D0 \exp{(-Ea / k{B}T)} ) [2]. Here, ( D0 ) is the pre-exponential factor, ( Ea ) is the activation energy for the diffusion process, and ( kB ) is the Boltzmann constant [2]. This equation predicts that the logarithm of the diffusion coefficient, ( \ln{(D)} ), scales linearly with the inverse of temperature, ( 1/T ), a relationship that is visually represented in an Arrhenius plot [1] [2]. The slope of this plot is ( -E_a/R ), allowing for direct experimental determination of the activation energy, a key parameter characterizing the energy barrier for atomic or ionic migration [1].

Theoretical Foundations

Physical Interpretation of the Arrhenius Parameters

The Arrhenius equation encapsulates two critical physical parameters. The pre-exponential factor (( D0 )) embodies the attempt frequency or the intrinsic rate of attempts to overcome the energy barrier. In the context of diffusion, it is related to the vibrational frequency of atoms and the geometry of the diffusion pathway [1]. The exponential term, ( \exp{(-Ea / k{B}T)} ), represents the fraction of atoms or molecules that possess sufficient thermal energy to overcome the activation energy barrier, ( Ea ) [1]. This activation energy is the minimum energy required for a successful diffusion event, such as an atom jumping from one lattice site to another or an ion moving through a solid matrix.

From a statistical mechanics perspective, the exponential term can be derived from the Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution, which describes the distribution of kinetic energies among particles at a given temperature. The fraction of particles with energy greater than or equal to ( Ea ) is proportional to this exponential factor [1]. More advanced theoretical frameworks, such as transition state theory, provide a deeper mechanistic interpretation. This theory describes the system passing through a high-energy "transition state" between the initial and final configurations. The Eyring equation, derived from transition state theory, expresses the rate constant in terms of the Gibbs free energy of activation (( \Delta G^\ddagger )), which encompasses both enthalpy (( \Delta H^\ddagger ), related to ( Ea )) and entropy (( \Delta S^\ddagger ), related to ( A ) or ( D_0 )) changes [1].

Conceptual Workflow for Diffusion Studies

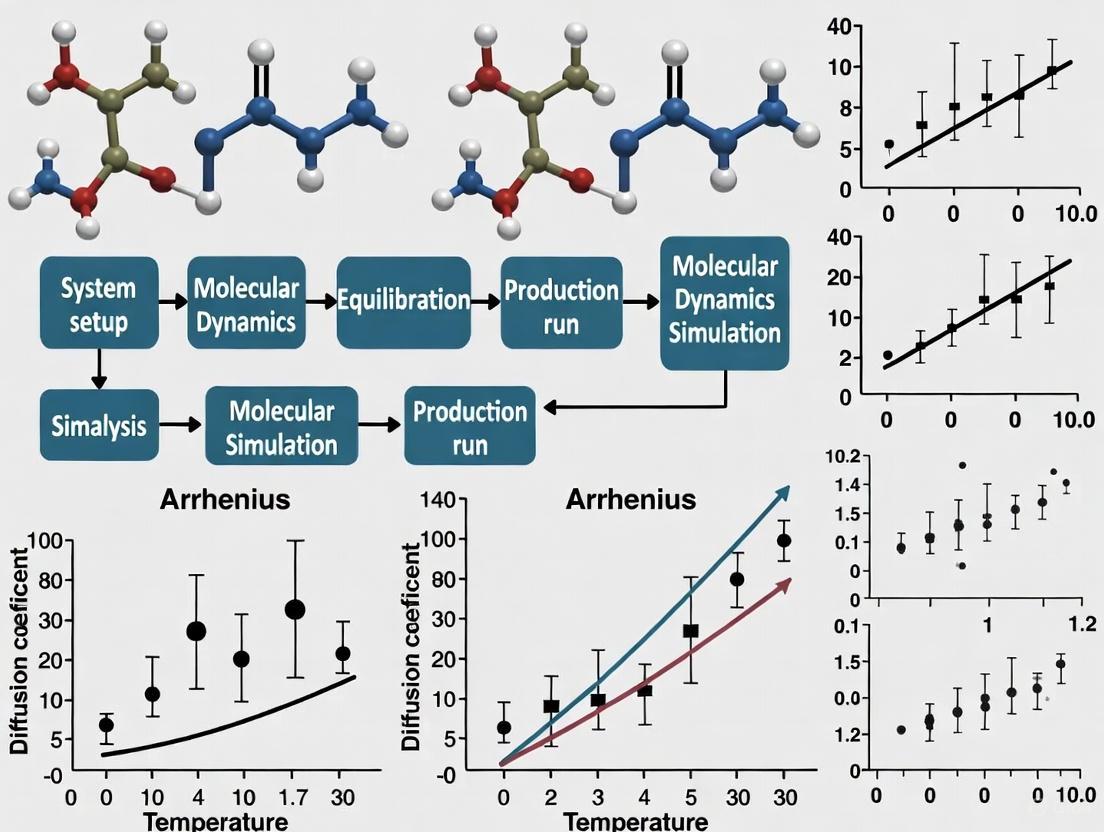

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for applying the Arrhenius equation in a molecular dynamics (MD) study of diffusion, from simulation to final analysis.

Applications in Molecular Dynamics Research

Calculating Diffusion Coefficients from MD Simulations

In Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations, the diffusion coefficient ( D ) is a primary output used for Arrhenius analysis. It can be calculated primarily through two methods [2].

The Mean Squared Displacement (MSD) method is the most commonly used and recommended approach. It is based on the relationship: ( MSD(t) = \langle [\textbf{r}(0) - \textbf{r}(t)]^2 \rangle ), where ( \textbf{r}(0) ) and ( \textbf{r}(t) ) are the positions of a particle at time zero and time ( t ), respectively, and the angle brackets denote an average over all particles and time origins. For three-dimensional diffusion, the diffusion coefficient is calculated from the slope of the MSD versus time plot in the long-time limit: ( D = \frac{\textrm{slope(MSD)}}{6} ) [2]. It is critical to ensure that the MSD plot is linear, indicating normal diffusive behavior, and to use a sufficiently long simulation time to gather adequate statistics [3] [2].

The Velocity Autocorrelation Function (VACF) method provides an alternative route. The VACF is defined as ( \langle \textbf{v}(0) \cdot \textbf{v}(t) \rangle ), and the diffusion coefficient is obtained from its integral: ( D = \frac{1}{3} \int{t=0}^{t=t{max}} \langle \textbf{v}(0) \cdot \textbf{v}(t) \rangle \rm{d}t ) [2]. This method requires a higher sampling frequency (smaller interval between saved trajectory frames) to accurately capture the velocity correlations.

A key consideration in these simulations is the presence of finite-size effects. The calculated diffusion coefficient can depend on the size of the simulation supercell. A robust approach involves performing simulations for progressively larger supercells and extrapolating the results to the "infinite supercell" limit [2].

MD Protocol for Ion Transport in Solids

The following workflow details the key steps for performing MD simulations to study ion diffusion in solid-state materials, a critical application in battery and fuel cell research.

Table 1: Key Parameters for a Production MD Simulation for Diffusion Studies

| Parameter | Typical Setting/Value | Purpose and Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Task | Molecular Dynamics | Defines the type of simulation. |

| Force Field/Engine | ReaxFF [2] or other ab initio | Determines the interatomic potentials. |

| Thermostat | Berendsen, Nose-Hoover | Maintains constant temperature. |

| Total Steps | 100,000+ [2] | Ensures sufficient sampling for statistics. |

| Time Step | 0.5 - 2.0 fs | Balances computational efficiency and numerical stability. |

| Sample Frequency | 5-10 steps [2] | Determines output trajectory resolution. |

| Equilibration Steps | 10,000+ [2] | Allows system to reach equilibrium before data collection. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials and Software for MD-based Diffusion Studies

| Item | Function/Description | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Dynamics Software | Platform for running simulations and calculating trajectories. | AMS package with ReaxFF engine [2]. |

| Force Fields | Mathematical functions describing interatomic potentials. | LiS.ff for lithium-sulfur systems [2]. |

| Visualization/Analysis Tools | Software for monitoring simulations and analyzing results. | AMSmovie for viewing trajectories and plotting MSD/VACF [2]. |

| Polymer Matrix | Biodegradable drug carrier material whose properties affect diffusion. | Poly-D,L-lactide-co-glycolide (PLGA) nanoparticles [4]. |

| Model Drug Compound | Fluorescent tracer for monitoring release kinetics. | Rhodamine 6G (R6G) [4]. |

| Solvent | Medium for drug release studies or gas diffusion. | Phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) [4]. |

| Sibenadet | Sibenadet, CAS:154189-40-9, MF:C22H28N2O5S2, MW:464.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 2,6-Dibromopyridine | 2,6-Dibromopyridine, CAS:626-05-1, MF:C5H3Br2N, MW:236.89 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Experimental Protocols and Data Analysis

Generating an Arrhenius Plot from MD Data

The process of constructing an Arrhenius plot to extract the activation energy (( Ea )) and pre-exponential factor (( D0 )) involves a clear, step-by-step procedure [2]:

- Perform MD Simulations at Multiple Temperatures: Conduct production MD runs for the same system at a minimum of four different temperatures (e.g., 600 K, 800 K, 1200 K, 1600 K) to establish a reliable temperature trend [2].

- Calculate Diffusion Coefficients (( D )): For the trajectory generated at each temperature, compute the diffusion coefficient using the MSD method, ensuring the MSD plot has a linear region from which a stable slope can be derived [2].

- Transform the Data: For each temperature ( T ), calculate its inverse (( 1/T ), in Kelvinâ»Â¹). Then, take the natural logarithm of each corresponding diffusion coefficient to get ( \ln(D) ).

- Plot and Fit: Create a plot of ( \ln(D) ) on the y-axis versus ( 1/T ) on the x-axis. The data points should form a straight line if they follow Arrhenius behavior. Perform a linear regression (least squares fit) on the data points.

- Extract Parameters: From the linear fit equation, ( y = mx + c ):

- Activation Energy (( Ea )): Calculate as ( Ea = -m \times R ), where ( m ) is the slope of the line and ( R ) is the gas constant (8.314 J/mol·K).

- Pre-exponential Factor (( D0 )): Calculate as ( D0 = e^{c} ), where ( c ) is the y-intercept of the fitted line.

Protocol for Validating Diffusion Data

A critical aspect of reliable MD research is the validation of the simulation data to avoid unsound conclusions [3]. Key validation steps include:

- Confirming Diffusive Behavior: Before calculating ( D ), it is essential to verify that the system has transitioned from subdiffusive to normal diffusive behavior. This is evidenced by a linear regime in the MSD plot [3].

- Optimal Equilibration: The system must be fully equilibrated before starting the production run. The equilibration time should be determined by monitoring the stabilization of properties like energy, pressure, and volume [3].

- Assessing Statistical Accuracy: Running multiple independent simulations or very long trajectories is necessary to ensure that the calculated MSD slope and resulting ( D ) value have converged and are not subject to large statistical uncertainties [2].

Advanced Concepts and Non-Arrhenius Behavior

While the Arrhenius equation is widely applicable, its assumption of temperature-independent ( Ea ) and ( D0 ) is a simplification. State-of-the-art research often deals with non-Arrhenius behavior, where the plot of ( \ln(D) ) vs. ( 1/T ) shows curvature instead of a perfect straight line [5] [6].

Several advanced frameworks address this:

- Modified Arrhenius Equation: A common extension is ( k = A T^n e^{-E_a / RT} ), which includes an explicit power-law dependence on temperature in the pre-exponential factor [1] [5].

- New Functional Forms for Liquid Phases: Recent work has proposed equations with four kinetic parameters to accurately describe the temperature dependence of liquid phase reaction rates from room temperature up to the solvent's critical point, where the original Arrhenius law fails [5].

- Anharmonicity and Temperature-Dependent Activation Energies: In solids, anharmonic vibrations at high temperatures can lead to a temperature-dependent activation energy. For example, in body-centered cubic tungsten, strong anharmonicity explains the observed non-Arrhenius self-diffusion, a finding enabled by ab initio machine-learning approaches [6]. This signifies a paradigm shift from the traditional explanation based on di-vacancies.

The Arrhenius equation remains a cornerstone for interpreting the temperature dependence of diffusion coefficients in MD research. Its application, from setting up and running validated MD simulations to analyzing trajectories via MSD and constructing Arrhenius plots, provides a direct pathway to extract fundamental thermodynamic parameters like the activation energy. However, researchers must be aware of its limitations and the growing evidence of non-Arrhenius behavior in complex systems. The integration of advanced computational frameworks, including machine-learning potentials and anharmonic corrections, is pushing the boundaries of accurate diffusion prediction, offering profound insights for materials science and drug development.

In the study of temperature-dependent phenomena, from chemical reaction rates to molecular diffusion, the Arrhenius equation provides a fundamental framework for understanding the thermal activation processes. Within the specific context of molecular dynamics (MD) research on diffusion coefficients, the two parameters of the Arrhenius equation—the activation energy (Ea) and the pre-exponential factor (D0)—serve as critical indicators of the underlying mechanisms and rates of atomic and molecular transport. This application note details the theoretical significance, experimental determination, and practical application of these key parameters for researchers and scientists engaged in drug development and materials science.

The standard form of the Arrhenius equation for diffusion is expressed as: D = Dâ‚€ exp(-Ea/RT) where D is the diffusion coefficient, Dâ‚€ is the pre-exponential factor (or attempt frequency), Ea is the activation energy for the diffusion process, R is the universal gas constant, and T is the absolute temperature [7] [2]. A more useful linearized form of the equation is used for graphical determination of these parameters: ln(D) = ln(Dâ‚€) - (Ea/R)(1/T) [8] [1] [2]

This relationship reveals that a plot of ln(D) versus 1/T—known as an Arrhenius plot—yields a straight line with a slope of -Ea/R and a y-intercept of ln(D₀) [8] [1]. The careful determination of this plot through MD simulation or experiment is therefore central to extracting these essential kinetic parameters.

Parameter Definitions and Significance

Activation Energy (Ea)

The activation energy (Ea) represents the minimum energy barrier that must be overcome for a diffusion process to occur [8] [1]. In the context of diffusion, it corresponds to the energy required for an atom or molecule to jump between adjacent lattice sites, navigate through amorphous regions of a polymer, or escape from a potential energy well [7] [2].

- Physical Interpretation: Ea reflects the temperature sensitivity of the diffusion process. A higher Ea indicates that the diffusion rate is more strongly dependent on temperature changes [1] [7].

- Theoretical Foundation: The exponential term exp(-Ea/RT) in the Arrhenius equation represents the fraction of atoms or molecules in a system that possess sufficient kinetic energy to surpass the energy barrier Ea at a given temperature T, following the Maxwell-Boltzmann energy distribution [1].

Pre-exponential Factor (Dâ‚€)

The pre-exponential factor (Dâ‚€), also known as the frequency factor or attempt frequency, encompasses the intrinsic characteristics of the diffusing species and the matrix through which diffusion occurs [1] [2].

- Physical Interpretation: Dâ‚€ relates to the number of attempts per unit time that a particle makes to overcome the activation barrier. It is influenced by factors such as the vibrational frequency of the atom in its potential well and the geometry of the diffusion pathway [1] [7].

- Theoretical Foundation: In transition state theory, the pre-exponential factor is related to the entropy change associated with the diffusion process. A higher entropy gain in the transition state corresponds to a larger Dâ‚€ value [1].

Quantitative Parameter Data

The following tables compile representative values of activation energy (Ea) and pre-exponential factor (Dâ‚€) for diffusion processes in various material systems, as reported in recent research.

Table 1: Activation Energies and Pre-exponential Factors for Ag Diffusion in SiC (Silicon Carbide) [9]

| Experimental Method | Activation Energy, Ea (kJ·molâ»Â¹) | Pre-exponential Factor, Dâ‚€ |

|---|---|---|

| Ag Paste (FBCVD SiC) | 247.4 | Not Specified |

| Integral Release (Irradiated TRISO fuel) | 125.3 | Not Specified |

| Fractional Ag Release during Irradiation | 121.8 | Not Specified |

| Ag Ion Implantation | 274.8 | Not Specified |

Table 2: Exemplary Activation Energies for Gas Permeation in Polymers [7]

| Polymer | Permeant | Pre-exponential Factor, P₀ (cm³ mm/m² day atm) | Activation Energy, ΔEp (kJ/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low Density Polyethylene | Oxygen | 5.82 × 10⹠| 42.7 |

| Low Density Polyethylene | Nitrogen | 2.88 × 10¹Ⱐ| 49.9 |

| Low Density Polyethylene | Carbon Dioxide | 5.43 × 10⹠| 38.9 |

| Poly(vinylidene chloride) | Nitrogen | 7.88 × 10¹Ⱐ| 70.3 |

| Poly(vinylidene chloride) | Oxygen | 7.22 × 10¹Ⱐ| 66.6 |

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials for Diffusion Studies

| Item | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| General Purpose Polystyrene (GPPS) / High Impact Polystyrene (HIPS) | Polymer matrix for studying diffusion of organic molecules, relevant to food packaging and drug delivery systems [10]. |

| n-Alkane Model Compounds (e.g., n-octane to n-tetracosane) | A series of surrogate contaminants with varying molecular volumes to systematically study diffusion behavior in polymers [10]. |

| Organic Solvent Mixtures (e.g., Acetone, Ethyl Acetate, Toluene, Chlorobenzene) | Model compounds representing different chemical functionalities for desorption and permeation kinetics studies [10]. |

| ReaxFF Force Field (e.g., LiS.ff) | A reactive force field used in molecular dynamics simulations to model chemical reactions and diffusion in complex systems like lithiated sulfur cathodes [2]. |

| Berendsen Thermostat | An algorithm used in MD simulations to control the temperature of the system, crucial for simulating temperature-dependent diffusion [2]. |

Experimental Protocols

Molecular Dynamics Protocol for Determining D and Ea

This protocol outlines the procedure for calculating diffusion coefficients (D) at multiple temperatures using molecular dynamics (MD) simulations and subsequently determining the activation energy (Ea) and pre-exponential factor (Dâ‚€) via an Arrhenius plot [2].

Step 1: System Preparation and Equilibration

- Import/Construct the Atomic Model: Build or import the initial atomic structure of the system (e.g., a crystal structure from a CIF file or an amorphous structure).

- Geometry Optimization and Lattice Relaxation: Perform an energy minimization using a conjugate gradient method or similar algorithm to relieve internal stresses and find a low-energy equilibrium configuration. This step often includes optimizing the unit cell dimensions [2].

- Simulated Annealing (For Amorphous Systems): To generate a realistic amorphous structure, perform an MD simulation with a specific temperature profile:

- Step 1 (5,000 steps): Hold at 300 K.

- Step 2 (20,000 steps): Heat linearly from 300 K to 1600 K.

- Step 3 (5,000 steps): Cool rapidly from 1600 K to 300 K [2].

- Re-optimization: Perform a final geometry optimization on the annealed structure.

Step 2: Production MD Simulations at Multiple Temperatures

- Setup: For the equilibrated structure, set up a series of MD simulations (e.g., at 600 K, 800 K, 1200 K, and 1600 K). Using at least four different temperatures is recommended for a reliable Arrhenius plot [2].

- Parameters:

- Task: Molecular Dynamics.

- Force Field: Select an appropriate force field (e.g., ReaxFF for reactive systems [2] or COMPASS [11]).

- Ensemble: NPT (constant Number of particles, Pressure, and Temperature) is commonly used.

- Thermostat: Use a thermostat like Berendsen with a damping constant of 100 fs to maintain the target temperature [2].

- Steps: Typically 100,000+ production steps after equilibration.

- Time Step: 0.25-1.0 fs.

- Sample Frequency: Save atomic coordinates and velocities every 5-10 steps for subsequent analysis [2].

Step 3: Diffusion Coefficient (D) Calculation from MD Trajectory The diffusion coefficient can be calculated using one of two primary methods:

- A. Mean Squared Displacement (MSD) Method (Recommended)

- Calculate the MSD for the diffusing species (e.g., Li ions) over time: MSD(t) = ⟨[r(0) - r(t)]²⟩.

- The diffusion coefficient D is obtained from the slope of the linear region of the MSD plot: D = slope(MSD) / (6) for 3-dimensional diffusion [2]. The divisor is 2d, where d is the dimensionality.

- Ensure the MSD plot is linear, indicating normal diffusion. A non-linear plot may require a longer simulation time for better statistics [2].

- B. Velocity Autocorrelation Function (VACF) Method

- Calculate the VACF for the diffusing species: ⟨v(0) · v(t)⟩.

- The diffusion coefficient D is obtained by integrating the VACF: D = (1/3) ∫₀ᵗáµáµƒË£ ⟨v(0) · v(t)⟩ dt [2].

- The plot of the integrated value should converge to a constant value for large enough times.

Step 4: Construct Arrhenius Plot and Determine Ea and Dâ‚€

- For each temperature T in your study, you now have a diffusion coefficient D(T).

- Prepare an Arrhenius plot by plotting ln(D) on the y-axis against 1/T (where T is in Kelvin) on the x-axis [8] [2].

- Perform a linear regression (least-squares fit) on the data points. The resulting plot should be a straight line [1].

- Calculate the Parameters:

Experimental Laboratory Protocol for Determining Ea of Diffusion in Polymers

This protocol describes an experimental approach based on desorption kinetics to determine diffusion coefficients and activation energies in polymer systems like polystyrene, relevant to drug packaging and functional barriers [10].

Step 1: Sample Preparation and Spiking

- Polymer Sheet Fabrication: Manufacture thin polymer sheets (e.g., ~350 µm thickness) of the material under study (e.g., GPPS, HIPS).

- Homogeneous Spiking: Incorporate a mixture of model compounds (e.g., n-alkanes like n-octane to n-tetracosane, and other organics like toluene, benzophenone) homogeneously into the polymer melt during the sheet formation process [10].

- Concentration Quantification: Determine the initial concentration of each model compound in the spiked sheets using solvent extraction (e.g., with acetone at 40°C for 3 days) followed by GC-FID analysis, or headspace-GC for volatile substances [10].

Step 2: Desorption Kinetics Measurement

- Isothermal Desorption: For each desired temperature (e.g., from 0°C to 115°C), place weighed samples of the spiked polymer (e.g., 1.0 g) into headspace vials [10].

- Headspace Sampling and Analysis: At specific time intervals, analyze the concentration of the model compounds in the headspace of the vials using Headspace Gas Chromatography with Flame Ionization Detection (HS-GC-FID) [10].

- Typical HS-GC Conditions [10]:

- Column: ZB-1, 30 m length.

- Oven Temp.: 50°C (4 min) to 320°C at 20°C/min.

- HS Oven Temp.: 150°C.

- Equilibration Time: 1 hour.

- Typical HS-GC Conditions [10]:

Step 3: Diffusion Coefficient (D) Calculation from Desorption Data

- Kinetic Analysis: From the time-dependent decay of the model compound concentration in the polymer (obtained from the headspace signal), determine the desorption kinetics.

- Fickian Diffusion Model: Assuming the desorption follows Fick's laws of diffusion, fit the kinetic data to an appropriate solution of the diffusion equation for the given sample geometry (e.g., a thin sheet) to extract the diffusion coefficient D at each temperature [10].

Step 4: Determine Activation Energy (Ea) and Pre-exponential Factor (Dâ‚€)

- This step is identical to Step 4 of the MD protocol. Plot ln(D) vs. 1/T for the experimentally determined diffusion coefficients and perform a linear fit to obtain Ea and Dâ‚€ from the slope and intercept, respectively [10].

Workflow and Data Analysis Diagrams

Diagram Title: Overall Workflow for Determining Ea and Dâ‚€

Diagram Title: Diffusion Coefficient Calculation Paths

Physical Interpretation of Activation Energy in Diffusion Processes

In the field of materials science and drug development, understanding ion and molecular transport within solid-state materials or biological systems is fundamental for designing better batteries, pharmaceuticals, and drug delivery mechanisms. Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations have become an indispensable tool for interpreting experimental data, revealing diffusion mechanisms, and predicting the properties of new systems [3]. A critical component of this analysis is the temperature-dependent diffusion coefficient, which often follows an Arrhenius relationship, providing direct access to the activation energy ((E_a)) of the diffusion process.

The physical interpretation of this activation energy is the energy barrier that atoms or ions must overcome to move from one stable site to another within a material or macromolecular structure. This application note, framed within broader thesis research on temperature-dependent diffusion, details the protocols for obtaining this key parameter from MD simulations, providing structured data, experimental methodologies, and visualization tools tailored for researchers and scientists in drug development and materials science.

Theoretical Foundation

Molecular diffusion describes the spread of particles through random motion from regions of high concentration to low concentration. In the context of MD simulations, the self-diffusion coefficient ((D)) can be directly calculated from the mean squared displacement (MSD) of particles over time using the Einstein relation [12]:

[ \langle |\mathbf{r}(t) - \mathbf{r}(0)|^2 \rangle = 2nDt ]

where (\mathbf{r}(t)) is the position at time (t), (\mathbf{r}(0)) is the initial position, (n) is the dimensionality (typically 3 for MD simulations), and the angle brackets denote an ensemble average. The diffusion coefficient is then one-sixth of the slope of the MSD versus time plot [2] [12].

Alternatively, the diffusion coefficient can be obtained through the Green-Kubo relation, which integrates the velocity autocorrelation function (VACF) [2] [12]:

[ D = \frac{1}{3} \int_{0}^{\infty} \langle \mathbf{v}(0) \cdot \mathbf{v}(t) \rangle dt ]

The temperature dependence of the diffusion coefficient is empirically described by the Arrhenius equation [2]:

[ D(T) = D0 \exp\left(-Ea / k_B T\right) ]

where (D0) is the pre-exponential factor representing the theoretical maximum diffusion coefficient at infinite temperature, (Ea) is the activation energy, (kB) is the Boltzmann constant, and (T) is the absolute temperature. By plotting (\ln(D)) against (1/T), one obtains the Arrhenius plot, where the slope is (-Ea/kB), thus allowing for the direct calculation of the activation energy [2]. Physically, (Ea) represents the average energy barrier that a diffusing particle must surmount to hop between stable positions in its local environment.

Figure 1: Workflow for extracting activation energy from MD simulations. The key steps involve calculating diffusion coefficients at multiple temperatures and constructing an Arrhenius plot.

Quantitative Data Presentation

Table 1: Diffusion Coefficient Calculation Methods from MD Simulations

| Method | Fundamental Equation | Key Requirements | Advantages | Potential Pitfalls |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Squared Displacement (MSD) [2] [12] | ( D = \frac{\text{slope}(MSD)}{6} ) ( MSD(t) = \langle [\mathbf{r}(0) - \mathbf{r}(t)]^2 \rangle ) | Long simulation times to ensure linear MSD; confirmation of transition from subdiffusive to diffusive behavior [3]. | Intuitively clear; directly related to particle trajectories; recommended for its reliability [2]. | Finite-size effects require careful supercell size selection and potential extrapolation [2]. |

| Velocity Autocorrelation Function (VACF) [2] [12] | ( D = \frac{1}{3} \int{0}^{t{max}} \langle \mathbf{v}(0) \cdot \mathbf{v}(t) \rangle dt ) | High sampling frequency (small time between saved velocity frames) for accurate integration [2]. | Can provide mechanistic insights into diffusion; may converge faster than MSD in some cases. | Sensitive to the correlation time and the upper limit of integration ((t_{max})). |

Table 2: Example Diffusion Coefficients and Extracted Activation Energy for Li0.4S

The following data, extracted from a tutorial on Li0.4S cathode materials [2], illustrates the process of determining activation energy.

| Temperature (K) | Diffusion Coefficient, D (m²/s) | ln(D) | 1/T (Kâ»Â¹) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 600 | To be calculated | - | 0.001667 |

| 800 | To be calculated | - | 0.001250 |

| 1200 | To be calculated | - | 0.000833 |

| 1600 | 3.09 × 10â»â¸ [2] | -17.29 | 0.000625 |

Note: The activation energy (E_a) and pre-exponential factor (D_0) are obtained from the linear fit of ln(D) vs. 1/T.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Calculation of Diffusion Coefficient via MSD Analysis

This protocol details the steps for computing the diffusion coefficient from a Molecular Dynamics trajectory using the Mean Squared Displacement method, as implemented in the SCM software suite [2].

I. Prerequisites

- A fully equilibrated MD trajectory file (e.g., from a ReaxFF, GAFF, or other force field engine).

- Ensure the trajectory is from the production run (equilibration steps excluded).

- The trajectory should contain atomic positions at a consistent sampling frequency.

II. Step-by-Step Procedure

1. Open the trajectory: Load the completed MD calculation in a visualization/analysis tool like AMSmovie.

2. Select MSD analysis: Navigate to the appropriate analysis menu (e.g., MD Properties → MSD).

3. Set analysis parameters:

- Atoms: Specify the atom type for analysis (e.g., Li for lithium ions).

- Steps: Define the range of MD steps for analysis, excluding the initial equilibration period (e.g., 2000 - 22001).

- Max MSD Frame: Set to a value that ensures the MSD plot is linear, typically corresponding to a time shorter than the total simulation time (e.g., 5000 frames).

4. Generate the MSD plot: Execute the calculation. The software will generate an MSD versus time plot.

5. Calculate D: The diffusion coefficient (D) is one-sixth of the slope of the linear region of the MSD curve. The analysis software often calculates this automatically and displays the value.

III. Critical Validation - Linearity Check: The MSD plot must be linear for the diffusion coefficient to be valid. A non-linear MSD indicates that the system may not be in a diffusive regime or the simulation time is too short [3]. - Convergence Check: The derived D value should be stable and not drift over longer simulation segments.

Protocol: Extrapolation to Lower Temperatures via Arrhenius Plot

This protocol describes how to determine the activation energy and predict diffusion coefficients at temperatures that are computationally prohibitive to simulate directly [2].

I. Prerequisites - Diffusion coefficients ((D)) calculated at a minimum of four different temperatures (e.g., 600 K, 800 K, 1200 K, 1600 K) using the protocol in Section 4.1.

II. Step-by-Step Procedure

1. Prepare data table: Create a table with columns for Temperature (T), calculated D, ln(D), and 1/T.

2. Construct Arrhenius plot: Plot ln(D) on the y-axis against 1/T on the x-axis.

3. Perform linear regression: Fit a straight line to the data points. The equation of the line will be:

[

\ln(D) = \ln(D0) - \frac{Ea}{kB} \cdot \frac{1}{T}

]

4. Extract parameters:

- Activation Energy ((Ea)): Calculate from the slope ((m)) of the line: (Ea = -m \cdot kB).

- Pre-exponential factor ((D0)): Calculate from the y-intercept: (D0 = \exp(\text{intercept})).

5. Extrapolate: Use the fitted Arrhenius equation to predict (D) at any desired temperature (e.g., room temperature, 300 K).

Figure 2: Logical workflow for extrapolating diffusion coefficients to lower temperatures using an Arrhenius relation, which allows prediction of properties at experimentally relevant temperatures.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for MD Simulations of Diffusion

| Tool / Reagent | Function / Role | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Force Fields (e.g., GAFF, ReaxFF) | Defines the potential energy surface governing atomic interactions, including bonded and non-bonded terms. | GAFF has been used to predict diffusion coefficients of organic solutes in aqueous solution with good accuracy [12]. ReaxFF is suitable for simulating lithiated sulfur cathode materials [2]. |

| Simulation Software with MD Engines | Performs the numerical integration of Newton's equations of motion to generate particle trajectories. | Packages like AMS with ReaxFF enable setting up and running MD simulations with defined thermostats and sampling frequencies [2]. |

| Thermostat (e.g., Berendsen) | Controls the system temperature during the simulation by scaling velocities. | Used in simulated annealing protocols (e.g., heating from 300 K to 1600 K and cooling) and production runs at a constant temperature [2]. |

| Structure Builder & Optimizer | Imports, generates, and energetically relaxes initial atomic structures before production MD. | Used to create amorphous Li0.4S structures by inserting Li atoms into a sulfur crystal and performing geometry optimization with lattice relaxation [2]. |

| Trajectory Analysis Tool | Analyzes MD output to compute properties like MSD, VACF, and ultimately the diffusion coefficient. | Tools like AMSmovie are used to generate MSD plots and calculate D from the slope, automating the application of the Einstein relation [2]. |

| Insulin Lispro | Insulin Lispro | Insulin Lispro is a rapid-acting insulin analog for diabetes research. This product is for Research Use Only and is not intended for diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

| 7-Hydroxyquetiapine | 7-Hydroxyquetiapine, CAS:139079-39-3, MF:C21H25N3O3S, MW:399.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The Role of Temperature in Atomic and Molecular Jump Mechanisms

Atomic and molecular jump mechanisms are fundamental to understanding diffusion and structural evolution in materials science. Temperature is a critical parameter that governs the kinetics and dynamics of these jumps. This article details the protocols for investigating these mechanisms, with a specific focus on generating data for temperature-dependent diffusion coefficient Arrhenius plots using Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations. The content is structured to provide researchers with actionable methodologies, validated by recent research, including studies on grain boundary stagnation in polycrystalline materials and diffusion in energy-relevant compounds [13] [2].

Key Concepts and Theoretical Background

Atomic jumps refer to the discrete, thermally activated displacement of atoms or molecules from one stable lattice site to another. These jumps are the elementary steps underlying macroscopic phenomena such as diffusion, creep, and phase transformations.

The Role of Temperature: Temperature provides the thermal energy required for atoms to overcome the energy barriers (activation energy, Ea) separating stable configurations. This relationship is quantitatively described by the Arrhenius equation for the diffusion coefficient (D):

D(T) = Dâ‚€ exp(-Eâ‚ / kBT)

where Dâ‚€ is the pre-exponential factor, kB is the Boltzmann constant, and T is the absolute temperature [2]. A plot of ln(D) against 1/T (an Arrhenius plot) should yield a straight line, from which Eâ‚ and Dâ‚€ can be extracted.

However, this behavior can be complex. Disruptive atomic jumps, as identified in grain boundary migration, demonstrate non-Arrhenius behavior at high driving forces and temperatures. These are jumps by a few atoms that disrupt the collective, ordered motion of a grain boundary, leading to its stagnation. Crucially, the atoms involved in these disruptive jumps do not differ significantly from their neighbors in terms of local energy, volume, or structure, making them challenging to detect with standard analysis and requiring specialized methods like displacement vector analysis [13].

Experimental Protocols

The following protocols outline the core procedures for using Molecular Dynamics (MD) to study jump mechanisms and compute diffusion coefficients for Arrhenius analysis.

Protocol 1: Calculating Diffusion Coefficients via MD

This protocol is adapted from studies on lithium diffusion in cathode materials and organic molecules in solution [2] [12].

Objective: To compute the diffusion coefficient (D) of a species (e.g., Li+ ions, solvent molecules) at a specific temperature from an MD trajectory.

Procedure:

- System Preparation and Equilibration:

- Build the System: Import or construct the initial atomic structure. For diffusion in solids, this may involve creating a supercell from a CIF file [2].

- Equilibrate the System: Perform a geometry optimization followed by MD equilibration in the NVT ensemble (constant Number of particles, Volume, and Temperature) at the target temperature. Use a thermostat like Berendsen with a damping constant of 100 fs. The system must reach equilibrium, confirmed by stable potential energy and temperature [3] [2].

- Production MD Run:

- Switch to the NVE ensemble (constant Number of particles, Volume, and Energy) or continue in NVT for production data collection.

- Run a sufficiently long simulation (e.g., 100,000+ steps) to achieve good statistics. The required time depends on the system size and diffusion rate [12].

- Set the sampling frequency to save atomic coordinates and velocities every few steps (e.g., every 5 steps). The time between saved frames,

Δt = (sampling frequency) * (time step), defines the time resolution for analysis [2].

- Diffusion Coefficient Analysis:

- Mean Squared Displacement (MSD) Method (Recommended):

- Calculate the MSD for the atoms of interest (e.g., Li) over the production trajectory. The 3D MSD is defined as

MSD(t) = ⟨[r(0) - r(t)]²⟩[2] [12]. - Plot MSD(t) against time. For normal diffusion, this relationship becomes linear at long times.

- Perform a linear fit to the MSD curve in the diffusive regime.

- Calculate the diffusion coefficient using the Einstein relation:

D = slope(MSD) / 6(for 3-dimensional diffusion) [2] [12].

- Calculate the MSD for the atoms of interest (e.g., Li) over the production trajectory. The 3D MSD is defined as

- Velocity Autocorrelation Function (VACF) Method:

- Mean Squared Displacement (MSD) Method (Recommended):

Validation Note: For solutes in solution, reliable prediction of D can require very long simulation times (tens of nanoseconds). Averaging results from multiple independent short-MD simulations is an efficient sampling strategy [12].

Protocol 2: Generating an Arrhenius Plot

Objective: To determine the activation energy (Ea) and pre-exponential factor (Dâ‚€) for a diffusion process.

Procedure:

- Multi-Temperature Simulations: Using the exact same system setup and simulation parameters (except temperature), perform Protocol 1 for at least four different temperatures (e.g., 600 K, 800 K, 1200 K, 1600 K) [2].

- Calculate D(T): For each temperature, compute the diffusion coefficient D using the MSD method.

- Construct the Arrhenius Plot:

- Create a table of

ln(D)and1/Tfor all simulated temperatures. - Plot

ln(D)on the y-axis versus1/Ton the x-axis.

- Create a table of

- Linear Regression and Parameter Extraction:

- Perform a linear fit:

ln[D(T)] = ln(Dâ‚€) - (Eâ‚ / k_B) * (1/T). - The y-intercept of the fit gives

ln(Dâ‚€). - The slope of the fit is

-Eâ‚ / k_B, from which the activation energy Eâ‚ is calculated [2].

- Perform a linear fit:

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for these protocols, from system setup to the final Arrhenius analysis.

Data Presentation and Analysis

Quantitative Data on Temperature-Dependent Phenomena

The table below summarizes key quantitative findings from recent studies on various temperature-dependent atomic and molecular jump mechanisms.

Table 1: Summary of Temperature-Dependent Jump and Diffusion Phenomena

| System | Temperature Range | Key Observation / Value | Analysis Method | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grain Boundary Migration | Various High T | Disruptive atomic jumps cause GB stagnation; Non-Arrhenius behavior observed. | Displacement Vector Analysis | [13] |

| Li~0.4~S Cathode | 600 K - 1600 K | D at 1600 K: ~3.05×10â»â¸ m²/s (avg. of MSD/VACF). Used for Arrhenius extrapolation. | MSD & VACF | [2] |

| Carbyne-Graphene Nanoelement | < 1000 K > 1000 K | Strength decreases ~linearly with T; transition to defect-mediated failure. | Strength Calculation | [14] |

| Rejuvenators in Aged Bitumen | Experimental T range | Diffusion coefficients: 10â»Â¹Â¹ to 10â»Â¹â° m²/s; Order: Bio-oil > Engine-oil > Naphthenic-oil > Aromatic-oil. | MD Simulation & Experimental Validation | [15] |

| Organic Solutes in Aqueous Solution | 300 K | Average Unsigned Error (AUE) from expt.: 0.137 ×10â»âµ cm²/s. | MSD (GAFF Force Field) | [12] |

Visualizing the Atomic Jump Mechanism

The following diagram illustrates the mechanism of a disruptive atomic jump at a grain boundary, as revealed by atomistic simulations [13].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Software and Force Fields for MD Simulations of Jump Mechanisms

| Item Name | Function / Application | Specific Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| ReaxFF Force Field | Reactive force field for simulating chemical reactions and diffusion in complex materials (e.g., Li-S batteries). | Used with the AMS software package to simulate Li ion diffusion in a Li~0.4~S cathode [2]. |

| General AMBER Force Field (GAFF) | Force field for simulating small organic molecules and their diffusion in solution. | Validated for predicting diffusion coefficients of organic solutes in aqueous solution with high accuracy [12]. |

| TIP4P/2005 Water Model | Rigid, non-reactive water potential for simulating the structure and dynamics of water and ice. | Used to study the structural evolution of amorphous solid water (ASW) upon annealing [16]. |

| AMS Software Package | A unified software suite for performing MD and Monte Carlo simulations with various force fields. | Used in the tutorial for calculating Li ion diffusion coefficients [2]. |

| Displacement Vector Analysis | A specialized analytical method to detect subtle, disruptive atomic jumps that are not revealed by standard metrics. | Critical for identifying the atoms responsible for grain boundary stagnation [13]. |

| Isoluminol | Isoluminol, CAS:3682-14-2, MF:C8H7N3O2, MW:177.16 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Parogrelil | Parogrelil | Parogrelil is a potent PDE3 inhibitor for research into asthma and circulatory diseases. This product is for Research Use Only (RUO). Not for human use. |

Understanding atomic and molecular jump mechanisms through the lens of temperature is vital for advancing materials design and drug development. The protocols detailed here, centered on MD simulations and Arrhenius analysis, provide a robust framework for quantifying these dynamics. Researchers must be aware of complexities such as non-Arrhenius behavior and the subtle nature of disruptive jumps, which necessitate advanced detection methods. The integration of well-validated force fields and careful simulation practices, as outlined, ensures the reliable generation of data that can inform the development of new materials, from battery components to pharmaceutical formulations.

Differentiating Interstitial, Substitutional, and Surface Diffusion Mechanisms

Diffusion in solids is a fundamental transport phenomenon that governs mass transport, phase transformations, and microstructural evolution in a wide range of engineering materials, from structural alloys to functional drug delivery systems. The mechanism and rate of atomic diffusion significantly influence material properties including strength, durability, and corrosion resistance, making understanding these processes essential for materials design and optimization. In crystalline solids, atomic diffusion proceeds through several well-characterized pathways, primarily categorized as substitutional, interstitial, and surface diffusion, each with distinct kinetics influenced by atomic size, bonding, crystal structure, temperature, and defect density. These parameters control both the rate and directionality of atomic motion, dictating which mechanism dominates under a given set of conditions. This application note provides a comprehensive differentiation of these fundamental diffusion mechanisms, with particular emphasis on their characterization through temperature-dependent diffusion coefficients and Arrhenius analysis within molecular dynamics (MD) research frameworks, specifically contextualized for materials and pharmaceutical applications.

Fundamental Mechanisms and Theoretical Framework

Substitutional Diffusion

Substitutional diffusion occurs when atoms migrate by exchanging positions with vacancies within the crystal lattice. This mechanism is typical for larger atoms that occupy regular lattice sites and cannot easily pass through interstitial spaces. The process is governed by two key energy components: the vacancy formation energy, which determines how many vacancies are present, and the migration energy, which defines the barrier for an atom to jump into an adjacent vacant site. Substitutional diffusion is relatively slow due to strong atomic bonding and low vacancy concentrations at low to moderate temperatures. A direct atomic-scale observation of this mechanism was demonstrated in Hf-doped α-Al₂O₃, where Hf atoms were found to preferentially diffuse along grain boundaries by exchanging with co-segregated Al vacancies [17].

Interstitial Diffusion

Interstitial diffusion involves the migration of small atoms (e.g., hydrogen, carbon, nitrogen) through interstitial sites between larger host atoms in the lattice. Since this mechanism does not require vacancies, it occurs at significantly higher rates than substitutional diffusion, often by several orders of magnitude. The activation energy is primarily due to the distortion of surrounding atoms as the interstitial atom squeezes through the lattice. This mechanism is particularly important in processes such as carburization, nitriding, and hydrogen embrittlement phenomena. Body-centered cubic (BCC) structures facilitate faster interstitial diffusion due to their more open lattice, resulting in lower activation energies. Research on ω-TiZr alloys has demonstrated distinct interstitial site preferences for hydrogen atoms, with identified pathways exhibiting energy barriers as low as 0.145 eV for specific site-to-site migrations [18].

Surface Diffusion

Surface diffusion occurs when atoms migrate along the exposed surface of a material, which typically has unsatisfied bonds and higher free energy. This mechanism facilitates rapid atomic transport along defect cores with significantly lower activation energies compared to bulk lattice diffusion. Surface diffusion is critical in processes such as catalysis, sintering, oxidation, and thin-film growth, and becomes particularly dominant in nanostructures, films, and powders where high surface area-to-volume ratios promote rapid atomic mobility. While these mechanisms do not contribute significantly to bulk mass transport in thick materials, they are critically important in nanoscale systems and surface-mediated processes [19].

Mathematical Foundation: Fick's Laws and Arrhenius Equation

Mathematically, diffusion is classically described by Fick's Laws. Fick's First Law models steady-state atomic flux, driven by concentration gradients, while Fick's Second Law captures transient diffusion behavior, showing how concentration profiles evolve over time. These formulations provide the foundation for modelling mass transport in metallurgical and materials systems [19].

The temperature dependence of diffusion is universally described by the Arrhenius equation: $$D = D_0 \exp\left(-\frac{Q}{RT}\right)$$ where D is the diffusion coefficient, Dâ‚€ is the pre-exponential factor, Q is the activation energy, R is the gas constant, and T is the absolute temperature. This relationship demonstrates that diffusion rates increase exponentially with temperature, with the activation energy Q representing the energy barrier for the atomic jump process [19]. Molecular dynamics simulations of hydrogen diffusion in tungsten have successfully utilized this relationship, calculating diffusion coefficients from mean squared displacement data and fitting them to the Arrhenius equation to obtain activation energies of 1.48 eV with a pre-exponential factor of 3.2×10â»â¶ m²/s [20].

Quantitative Comparison of Diffusion Mechanisms

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Diffusion Mechanisms in Solids

| Parameter | Substitutional Diffusion | Interstitial Diffusion | Surface Diffusion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Atomic Mechanism | Exchange with vacancies | Movement through interstitial sites | Migration along surface or defect cores |

| Typical Activating Species | Larger atoms (Hf in Al₂O₃) [17] | Small atoms (H, C, N in metals) [19] | Adatoms on surfaces (H, O on ω-TiZr) [18] |

| Activation Energy Range | High (includes vacancy formation + migration) | Low to moderate (primarily migration) | Very low (reduced coordination) |

| Relative Diffusion Rate | Slowest | Fast (orders of magnitude faster than substitutional) | Fastest (short-circuit path) |

| Temperature Dependence | Strong (Arrhenius behavior) | Strong (Arrhenius behavior) | Strong (Arrhenius behavior) |

| Crystal Structure Influence | FCC vs. BCC packing affects vacancy mobility | BCC favored over FCC for interstitial sites | Surface orientation and roughness dependent |

| Experimental Observation Methods | Time-resolved atomic-resolution STEM [17], Tracer profiling | MD simulations [20], First-principles calculations [18] | First-principles calculations [18], Field ion microscopy |

Table 2: Experimentally Determined Diffusion Parameters from Recent Studies

| Material System | Diffusing Species | Mechanism | Activation Energy (eV) | Pre-exponential Factor D₀ (m²/s) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| α-Al₂O₃ GB | Hf | Substitutional (vacancy exchange) | Not specified | Not specified | [17] |

| α-Al₂O₃ GB | Hf | Interstitial (GB) | 0.5 | Not specified | [17] |

| Tungsten (BCC) | H | Interstitial | 1.48 | 3.2×10â»â¶ | [20] |

| ω-TiZr (surface) | H | Surface | 0.145 (H3→H2) | Not specified | [18] |

| ω-TiZr (surface) | O | Surface | 0.433 (H3→H4) | Not specified | [18] |

| ω-TiZr (bulk) | H | Interstitial | 0.386 (OC4→OC5) | Not specified | [18] |

| ω-TiZr (bulk) | O | Interstitial | 0.489 (OC4→OC2) | Not specified | [18] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Molecular Dynamics Protocol for Diffusion Coefficient Calculation

The following protocol outlines the procedure for computing diffusion coefficients using molecular dynamics simulations, as demonstrated in studies of lithium ions in Liâ‚€.â‚„S cathode materials [2] and hydrogen in tungsten [20]:

System Preparation:

- Import Crystal Structure: Begin with the crystal structure of the host material, typically imported from a CIF file.

- Insert Dopant/Defect Atoms: Use builder functionality to randomly insert diffusing species atoms (e.g., Li, H) into the host system. For accurate representation, use Grand Canonical Monte Carlo (GCMC) methods for optimal placement.

- Geometry Optimization: Perform energy minimization through geometry optimization including lattice relaxation to achieve a stable initial configuration.

- Simulated Annealing (for amorphous systems): Create amorphous systems through MD-based simulated annealing:

- Heat system from 300K to high temperature (e.g., 1600K) over 20000 steps

- Rapid cool-down to room temperature over 5000 steps

- Use Berendsen thermostat with damping constant of 100 fs

Production MD Simulation:

- Equilibration Phase: Run 10,000-20,000 steps at target temperature to equilibrate system.

- Production Phase: Execute 100,000+ steps for trajectory analysis with appropriate sampling frequency (every 5-100 steps).

- Thermostat Settings: Use Berendsen or Nosé-Hoover thermostat with damping constant of 100 fs for temperature control.

Diffusion Coefficient Calculation:

- Mean Squared Displacement (MSD) Method (Recommended):

- Calculate MSD from trajectories: $MSD(t) = \langle [\textbf{r}(0) - \textbf{r}(t)]^2 \rangle$

- Determine diffusion coefficient: $D = \textrm{slope(MSD)}/6$ for 3D systems

- Ensure MSD plot is linear; if not, extend simulation time for better statistics

- Velocity Autocorrelation Function (VACF) Method:

- Compute VACF: $\langle \textbf{v}(0) \cdot \textbf{v}(t) \rangle$

- Integrate to obtain D: $D = \frac{1}{3} \int{t=0}^{t=t{max}} \langle \textbf{v}(0) \cdot \textbf{v}(t) \rangle \rm{d}t$

Arrhenius Analysis:

- Repeat MD simulations at multiple temperatures (minimum 4 points, e.g., 600K, 800K, 1200K, 1600K)

- Plot ln(D) versus 1/T and perform linear fit

- Extract activation energy Eâ‚ from slope and pre-exponential factor Dâ‚€ from intercept [2]

Direct Atomic-Scale Observation Protocol (STEM)

For direct observation of dopant diffusion at atomic scale, as demonstrated in Hf-doped α-Al₂O₃ [17]:

Sample Preparation:

- Prepare specially oriented samples containing grain boundaries of interest (e.g., Σ31 [0001]/(47̅11̅0) GB in α-Al₂O₃)

- Introduce dopant atoms (e.g., Hf) through appropriate doping techniques

Microscopy and Analysis:

- Time-Resolved Atomic-Resolution STEM:

- Use 300 kV electron probe which provides sufficient energy to overcome diffusion barriers without damaging sample

- Acquire sequential frames (e.g., 50 frames over 85 seconds) with annular dark-field (ADF) detection

- Utilize Z-contrast principle for heavy atom identification (Hf atoms appear brighter)

- Statistical Tracking:

- Construct maximum intensity maps to identify all Hf locations

- Track Hf atom positions frame-by-frame across multiple datasets (e.g., 3120 frames)

- Calculate difference images between consecutive frames to identify atomic jumps

- Data Analysis:

- Categorize diffusion events (substitutional vs. interstitial)

- Calculate Gibbsian excess to determine GB concentration (e.g., 0.25 ± 0.02 atom nmâ»Â² for Hf in α-Alâ‚‚O₃)

- Statistically analyze site preferences and jump frequencies

First-Principles Calculation Protocol

For determining diffusion pathways and energy barriers, as applied to H and O in ω-TiZr alloys [18]:

Calculation Setup:

- Model Construction: Build supercell models of surface and bulk phases with appropriate periodic boundary conditions

- Adsorption Site Analysis: Identify all possible interstitial sites (e.g., H1-H4 on surface, OC1-OC5 in bulk)

- Energy Calculations: Use density functional theory (DFT) with appropriate exchange-correlation functionals

Diffusion Pathway Analysis:

- Transition State Location: Employ nudged elastic band (NEB) method or dimer method to identify minimum energy paths

- Energy Barrier Calculation: Compute activation energies as difference between saddle point and initial state energies

- Site Preference Analysis: Calculate adsorption energies for all identified sites to establish stability hierarchy

- Diffusion Coefficient Estimation: Derive theoretical diffusion coefficients from energy barriers for comparison with experimental values

Visualization of Diffusion Mechanisms and Research Workflows

Diagram 1: Research Workflow for Diffusion Mechanism Identification. This flowchart illustrates the integrated experimental and computational approach for differentiating diffusion mechanisms, highlighting the three primary pathways and characterization methodologies.

Diagram 2: Atomic-Scale Mechanisms of Diffusion. This diagram illustrates the fundamental differences between the three primary diffusion mechanisms at the atomic level, highlighting structural relationships and key characteristics.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Diffusion Studies

| Category | Item/Software | Specification/Purpose | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Computational Tools | LAMMPS | Molecular Dynamics simulator with various force fields | Hydrogen diffusion in tungsten [20] |

| ReaxFF | Reactive force field for complex chemical systems | Li-ion diffusion in Liâ‚€.â‚„S cathode [2] | |

| DFT Codes (VASP, Quantum ESPRESSO) | First-principles electronic structure calculations | H/O adsorption and diffusion in ω-TiZr [18] | |

| ANN Potentials | Machine-learning interatomic potentials with DFT accuracy | Hf diffusion in α-Al₂O₃ GB structures [17] | |

| Simulation Support | Bacterial Foraging Optimization (BFO) | Hyperparameter optimization algorithm | Fine-tuning regression models for drug diffusion [21] |

| ν-Support Vector Regression (ν-SVR) | Machine learning regression model | Predicting chemical concentrations in 3D space [21] | |

| Experimental Materials | Hf-doped α-Al₂O₃ | Model system for GB diffusion studies | Direct observation of substitutional vs interstitial diffusion [17] |

| ω-TiZr Alloys | Getter material for surface diffusion studies | H and O adsorption/diffusion measurements [18] | |

| Tungsten BCC samples | Model for interstitial diffusion | Hydrogen diffusion mechanism analysis [20] | |

| Characterization Equipment | Atomic-Resolution STEM | 300kV with ADF detector for time-resolved imaging | Direct observation of atomic jumps at GBs [17] |

| Molecular Dynamics Setup | High-performance computing cluster | Temperature-dependent diffusion simulations [20] [2] | |

| 4-Chloro-1-naphthol | 4-Chloro-1-naphthol, CAS:604-44-4, MF:C10H7ClO, MW:178.61 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Tolterodine Dimer | Tolterodine Dimer, CAS:854306-72-2, MF:C35H41NO2, MW:507.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Application Notes for Drug Development Professionals

The principles of diffusion mechanisms find direct application in pharmaceutical development, particularly in drug delivery system design. Understanding and controlling molecular diffusion is crucial for developing effective controlled-release formulations where the rate of drug release is governed by diffusion through carrier matrices. Computational hybrid analyses combining mass transfer modeling with machine learning have demonstrated excellent predictive accuracy for drug diffusion in three-dimensional spaces, with ν-Support Vector Regression achieving R² scores of 0.99777 for concentration prediction [21].

Recent advances in diffusion models for small molecule generation, such as the DrugDiff framework, leverage principles of molecular diffusion in latent spaces to generate novel drug-like compounds with targeted properties. These models employ a multi-step denoising process conceptually analogous to atomic diffusion pathways, gradually transforming random noise into structured molecules through iterative refinement steps [22]. The flexibility of this approach allows guidance toward specific molecular properties without retraining the core model, making it particularly valuable for optimizing drug candidates for desired characteristics such as bioavailability, binding affinity, and synthetic accessibility.

For drug delivery system optimization, molecular dynamics simulations can predict diffusion coefficients of active pharmaceutical ingredients through various carrier matrices, enabling rational design of release profiles. The integration of machine learning approaches further enhances predictive capabilities, allowing rapid screening of formulation candidates based on their predicted diffusion characteristics [21]. These computational tools provide valuable insights before experimental validation, potentially accelerating development timelines and reducing costs associated with empirical formulation approaches.

Practical Guide: Calculating Diffusion Coefficients from MD Simulations

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation is a cornerstone computational technique for studying the dynamic behavior of molecules at an atomic level, operating on timescales from nanoseconds to microseconds [23]. A critical application of MD is the investigation of diffusion processes, which are fundamental to understanding phenomena in chemistry, biology, and materials science, such as drug delivery, membrane transport, and solute mobility. The accuracy of such studies hinges on two foundational choices: the force field, which determines the interatomic potential energy and forces and the ensemble, which defines the thermodynamic conditions of the simulation [24]. This document provides a detailed protocol for configuring MD simulations specifically for calculating diffusion coefficients, framed within a broader thesis on temperature-dependent diffusion and Arrhenius analysis. The Arrhenius equation, ( k = A e^{-Ea / RT} ), formalizes the exponential dependence of a rate process (like diffusion) on temperature, allowing for the extraction of the activation energy ((Ea)) from an Arrhenius plot ((\ln D) vs. (1/T)) [1] [25]. This guide is designed for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals seeking to perform rigorous and reproducible in silico diffusion studies.

Theoretical Foundation

Molecular Dynamics and Diffusion

Molecular Dynamics simulates the natural motion of atoms and molecules by numerically solving Newton's equations of motion. In this particle-based description, forces calculated from a potential energy function determine how atomic positions and velocities evolve over time [23]. The self-diffusion coefficient ((D)) is a key transport property that quantifies the mean-squared displacement (MSD) of a particle over time. In an MD simulation, (D) can be calculated from the asymptotic slope of the MSD versus time plot using the Einstein relation: [ D = \frac{1}{2d} \lim_{t \to \infty} \frac{d}{dt} \langle | \mathbf{r}(t) - \mathbf{r}(0) |^2 \rangle ] where (d) is the dimensionality (e.g., 3 for a bulk system), (\mathbf{r}(t)) is the position of a particle at time (t), and the angle brackets denote an ensemble average [24].

The Arrhenius Equation in Diffusion Studies

The temperature dependence of the diffusion coefficient typically follows an Arrhenius-like relationship, [ D = D0 e^{-Ea / RT} ] where (D0) is the pre-exponential factor, (Ea) is the activation energy for diffusion, (R) is the gas constant, and (T) is the absolute temperature [1] [26]. By performing simulations at multiple temperatures and calculating (D) for each, one can construct an Arrhenius plot of (\ln D) versus (1/T). The slope of the resulting linear fit is (-E_a / R), from which the activation energy is directly obtained [25]. This provides crucial molecular-level insight into the energy barrier associated with the diffusive process.

Critical Setup Parameters for Diffusion Studies

Force Field Selection

The force field is an empirical potential energy function used to calculate the potential energy (U) of a system as a function of its atomic coordinates. It is paramount for achieving accurate diffusion coefficients [24].

Energy Terms: A typical biomolecular force field consists of bonded and non-bonded terms [24]: [ U(\vec{r}) = \sum{U{bonded}}(\vec{r}) + \sum{U{non-bonded}}(\vec{r}) ] The bonded terms include potentials for bond stretching, angle bending, and torsion angles. The non-bonded terms are most critical for diffusion, as they govern intermolecular interactions and comprise:

- Electrostatics: Modeled by Coulomb's law, (V{Elec} = \frac{qi qj}{4\pi \epsilon0 \epsilonr r{ij}}), a long-range interaction [24].

- van der Waals (vdW) interactions: Most commonly described by the short-ranged Lennard-Jones (LJ) potential, (V_{LJ}(r) = 4\epsilon \left[ \left( \frac{\sigma}{r} \right)^{12} - \left( \frac{\sigma}{r} \right)^6 \right]), where (\sigma) defines the atomic radius and (\epsilon) the well depth [24].

Force Field Classification:

- Class 1 (e.g., AMBER, CHARMM, OPLS): Use harmonic potentials for bonds and angles. They are computationally efficient and widely used for biomolecular simulations, but may lack accuracy for certain properties without careful parameterization [24].

- Class 2 (e.g., MMFF94): Include anharmonic and cross-terms for a more accurate description of vibrational spectra, but are less common in MD [24].

- Class 3 (Polarizable force fields, e.g., AMOEBA, Drude): Explicitly model electronic polarization, which is critical for accurately simulating systems with varying dielectric environments or response to external fields. While more physically accurate, they are computationally more demanding by at least an order of magnitude [24].

Table 1: Comparison of Common Biomolecular Force Fields

| Force Field | Class | Common Uses | Combining Rules for LJ | Considerations for Diffusion Studies |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMBER | 1 | Proteins, DNA | Lorentz-Berthelot | Well-established; good for standard biomolecules. |

| CHARMM | 1 | Proteins, Lipids | Lorentz-Berthelot | Good for heterogeneous systems like membrane proteins. |

| OPLS | 1 | Proteins, Ligands | Geometric (OPLS) | Often optimized for liquid properties. |

| GROMOS | 1 | Proteins | Geometric | Parameterized for consistency with thermodynamic properties. |

| AMOEBA | 3 | Ions, Biomolecules | - | Higher accuracy for electrostatic environments; computationally expensive. |

| CHARMM/Drude | 3 | Lipids, DNA | - | Improved description of polarizability; slower dynamics may require longer simulations. |

Ensemble Selection

The thermodynamic ensemble defines the conserved quantities during the simulation and profoundly influences the system's behavior and the calculated properties [23].

- NVE (Microcanonical Ensemble): Constant Number of particles, Volume, and Energy. This is the natural result of integrating Newton's equations without modification. While physically rigorous, it does not correspond to standard laboratory conditions and the temperature can fluctuate significantly. It is less commonly used for quantitative studies of temperature-dependent diffusion [23].

- NVT (Canonical Ensemble): Constant Number of particles, Volume, and Temperature. This is the most critical ensemble for Arrhenius studies, as it allows for the direct simulation of a system at a specific, controlled temperature. Thermostats (e.g., Nosé-Hoover, velocity rescale) are applied to maintain a constant temperature, which is essential for obtaining the diffusion coefficient (D) at a series of precise temperatures for the Arrhenius plot [27].

- NPT (Isothermal-Isobaric Ensemble): Constant Number of particles, Pressure, and Temperature. This ensemble mimics common experimental conditions most closely. A barostat is used to maintain constant pressure, allowing the simulation box size to adjust. This is particularly important for systems like liquids, where density changes with temperature. For diffusion studies, running NPT simulations at each target temperature before switching to NVT for production can ensure the correct density is achieved.

For a robust Arrhenius analysis, a recommended protocol is to first equilibrate the system's density and pressure in the NPT ensemble, then switch to the NVT ensemble for the production run from which the diffusion coefficient is calculated. This ensures the temperature is strictly controlled for the dynamics being analyzed.

Experimental Protocol for Diffusion Coefficient Calculation

This protocol outlines the steps for setting up and running an MD simulation to calculate the diffusion coefficient of a molecule, such as water, in a bulk system using GROMACS, a widely used MD suite [27].

System Setup and Equilibration

- Obtain Initial Coordinates: Download or generate the molecular structure file in PDB format [27].

- Generate Topology and Coordinates: Use the

pdb2gmxcommand to create the molecular topology (.top) and coordinate (.gro) files, selecting an appropriate force field (see Table 1) when prompted [27]. - Define the Simulation Box: Place the molecule in the center of a periodic box using

editconf. A cubic or dodecahedral box is typical. - Solvate the System: Fill the box with solvent molecules (e.g., SPC, TIP3P, TIP4P water models) using

solvate[27]. - Add Ions (Optional): To neutralize the system's charge or achieve a specific ion concentration, use the

genioncommand after preparing a run input file withgrompp[27]. - Energy Minimization: Remove any bad contacts and relax the structure using a steepest descent or conjugate gradient algorithm.

- Equilibration:

- NVT Equilibration: Equilibrate the system at the target temperature (e.g., 300 K) for 100-500 ps.

- NPT Equilibration: Further equilibrate the system at the target temperature and pressure (e.g., 1 bar) for 100-500 ps to achieve the correct density.

Production Run and Analysis

- Production MD Simulation: Run a sufficiently long simulation in the NVT ensemble to ensure good statistics for the Mean-Squared Displacement (MSD) calculation. The required length depends on the system size and diffusivity.

- Calculate the Diffusion Coefficient:

- Extract the trajectory for analysis, ensuring molecules are made whole across periodic boundaries.

- Calculate the MSD using the

msdmodule. - Fit the linear portion of the MSD vs. time plot. The 3D self-diffusion coefficient is given by ( D = \frac{1}{6} \times \text{slope} ).

The following workflow diagram summarizes the key steps in this protocol:

Validation and Reference Data

A critical step in any simulation study is validation against experimental data. For water diffusion, extensive experimental measurements exist across a wide temperature range [26]. The calculated self-diffusion coefficients from your MD simulation can be compared to these reference values to assess the accuracy of your chosen force field and simulation protocol.

Table 2: Experimental Self-Diffusion Coefficients of Water (H₂¹â¶O) at Various Temperatures for Validation [26]

| Temperature (°C) | Absolute Temperature (K) | Diffusion Coefficient, D (10â»â¹ m²/s) |

|---|---|---|

| 0.0 | 273.15 | 1.130 |

| 5.0 | 278.15 | 1.313 |

| 10.0 | 283.15 | 1.536 |

| 15.0 | 288.15 | 1.777 |

| 20.0 | 293.15 | 2.022 |

| 25.0 | 298.15 | 2.299 |

| 30.0 | 303.15 | 2.590 |

| 35.0 | 308.15 | 2.919 |

| 40.0 | 313.15 | 3.240 |

To generate an Arrhenius plot, calculate (\ln D) and (1/T) (in Kelvin) for each temperature from your simulations and the reference data. A linear fit will yield the activation energy, (E_a).

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for MD Simulations

| Item / Resource | Function / Purpose |

|---|---|

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Source for initial experimental (e.g., X-ray, NMR) biomolecular structures to serve as simulation starting points [27]. |

| GROMACS MD Suite | A robust, open-source software package for performing MD simulations and subsequent trajectory analysis [27]. |

| CHARMM-GUI | A web-based platform that simplifies the process of building complex molecular systems and generating input files for various MD packages, including GROMACS, CHARMM, NAMD, and AMBER [28]. |

| Force Field Parameter Files | Files (e.g., forcefield.itp in GROMACS) containing all necessary parameters (masses, charges, bond constants, LJ parameters) for the chosen force field [24]. |

| Water Models | Pre-parameterized water molecules (e.g., SPC, TIP3P, TIP4P) used to solvate the system and mimic an aqueous environment [24]. |

| Parameter File (.mdp) | A critical input file that specifies all simulation parameters and algorithms (integrator, thermostats, barostats, output frequency, etc.) [27]. |

| Molecular Visualization Tool (e.g., RasMol, VMD) | Software for visually inspecting molecular structures, simulation boxes, and trajectories [27]. |

| Imidaclothiz | Imidaclothiz, CAS:105843-36-5, MF:C7H8ClN5O2S, MW:261.69 g/mol |

| 2,3-Dichloropyridine | 2,3-Dichloropyridine |

This application note provides a comprehensive framework for setting up molecular dynamics simulations to study diffusion processes and extract Arrhenius parameters. The careful selection of a force field and thermodynamic ensemble, coupled with a rigorous protocol for system preparation, equilibration, and production analysis, is fundamental to obtaining physically meaningful results. Validation against established experimental data for systems like water is a crucial step in building confidence in the simulation methodology. By adhering to these detailed protocols and leveraging the provided toolkit, researchers can conduct robust in silico investigations into the temperature-dependent diffusion of molecules, yielding valuable activation energies that deepen our understanding of dynamic processes in complex systems.

Extracting Mean Squared Displacement (MSD) from Trajectories

Mean Squared Displacement (MSD) analysis is a cornerstone technique for quantifying particle dynamics from trajectory data, serving as a direct gateway to calculating diffusion coefficients. In the context of molecular dynamics (MD) research, establishing a temperature-dependent diffusion coefficient via the Arrhenius equation provides crucial insights into activation energies and fundamental transport mechanisms [20]. This Application Note details a standardized protocol for accurate MSD extraction from molecular trajectories, emphasizing its critical role in temperature-dependent Arrhenius analysis for research in drug development and materials science.

The MSD function quantitatively describes the average squared distance a particle travels over time and is fundamentally connected to the self-diffusion coefficient, D, through the Einstein relation. For normal diffusion in three dimensions, this relationship is given by:

[MSD(\tau) = \langle | \vec{r}(t + \tau) - \vec{r}(t) |^2 \rangle = 6D\tau]

where (\vec{r}(t)) is the particle's position at time t, and (\tau) is the lag time [29] [30]. The slope of the linear region of the MSD plot against lag time is directly proportional to the diffusion coefficient. When studying temperature dependence, this calculated D is used in the Arrhenius equation:

[D = D0 \exp\left(-\frac{Ea}{k_B T}\right)]

where (D0) is the pre-exponential factor, (Ea) is the activation energy for diffusion, (kB) is Boltzmann's constant, and *T* is the absolute temperature [20]. Plotting (\ln(D)) against (1/T) (an Arrhenius plot) allows for the determination of (Ea) and (D_0), which are essential for understanding diffusion mechanisms and predicting molecular behavior under various thermal conditions.

Key Concepts and Data Presentation

Interpreting MSD Profiles for Motion Classification

The functional form of the MSD plot reveals the underlying nature of the particle's motion [29] [31]. The table below classifies the primary modes of diffusion and their characteristic MSD profiles.

Table 1: Classification of diffusion modes based on MSD profile characteristics.

| Type of Motion | MSD Functional Form | Anomalous Exponent (α) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Brownian (Normal) | ( MSD(\tau) \propto \tau ) | α ≈ 1 | Linear increase in MSD with lag time; indicative of free, random diffusion. |

| Subdiffusive | ( MSD(\tau) \propto \tau^\alpha ) | α < 1 | Power-law growth slower than linear; suggests confined motion or diffusion in crowded environments. |

| Superdiffusive | ( MSD(\tau) \propto \tau^\alpha ) | α > 1 | Power-law growth faster than linear; indicates directed or active transport with a constant drift velocity. |

| Confined | ( MSD(\tau) \propto R^2 ) | — | MSD plateaus to a constant value at long lag times, reflecting motion restricted within a radius R. |

Essential Reagents and Computational Tools

Accurate MSD analysis requires robust computational tools and properly prepared trajectory data. The following table summarizes key resources.

Table 2: Essential research reagents and software solutions for trajectory analysis and MSD calculation.

| Item/Software | Function/Application | Key Feature |

|---|---|---|

GROMACS (gmx msd) |

A comprehensive suite for MD simulations and analysis. | Integrated gmx msd command for efficient calculation of diffusion coefficients from unwrapped trajectories [32]. |

MDAnalysis (EinsteinMSD) |

A Python toolkit for analyzing MD simulations and trajectory data. | Provides the EinsteinMSD class with both windowed and FFT-based algorithms for efficient MSD computation [30]. |