Statistical Ensembles in Molecular Dynamics: A Guide for Biomedical Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive guide to the statistical ensembles used in Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations, tailored for researchers and professionals in drug development.

Statistical Ensembles in Molecular Dynamics: A Guide for Biomedical Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to the statistical ensembles used in Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations, tailored for researchers and professionals in drug development. It covers the foundational theory of statistical mechanics behind major ensembles (NVE, NVT, NPT, μVT), details their methodological implementation for simulating biomolecular processes like conformational changes and ligand binding, and offers practical guidance for troubleshooting common sampling issues. Furthermore, it explores advanced path sampling techniques like the Weighted Ensemble method for simulating rare events and discusses how to validate simulation results against experimental data, providing a complete framework for applying MD ensembles to challenges in biomedical research.

The Statistical Mechanics Foundation of MD Ensembles

Connecting Microscopic States to Macroscopic Thermodynamics

In the realm of molecular dynamics (MD) and statistical mechanics, thermodynamic ensembles provide the fundamental connection between the microscopic states of atoms and molecules and the macroscopic thermodynamic properties we measure in the laboratory. An ensemble, in this context, is an idealization consisting of a large number of copies of a system, considered simultaneously, with each copy representing a possible state that the real system might be in at any given moment [1]. These ensembles are not merely theoretical constructs but are essential tools for bridging the atomic and bulk scales, allowing researchers to derive thermodynamic properties from the laws of classical and quantum mechanics through statistical averaging [2].

The concept of phase space is central to understanding how ensembles function. In molecular dynamics, phase space is a multidimensional space where each point represents a complete state of the system, defined by all the positions and momenta of its components [3]. For a system containing N atoms, each with 3 spatial degrees of freedom, the phase space has 6N dimensions—3N position coordinates and 3N momentum coordinates [3]. As an MD simulation progresses over time, the system evolves and moves through different points in this phase space, effectively sampling different microscopic states [3]. The ensemble, therefore, represents the collection of these accessible points, and the averages of microscopic properties over this collection yield the macroscopic thermodynamic observables.

The choice of ensemble in molecular dynamics simulations depends primarily on the experimental conditions one wishes to mimic and the specific properties of interest. Different ensembles represent systems with different degrees of separation from their surroundings, ranging from completely isolated systems to completely open ones [2]. For researchers in drug development and materials science, selecting the appropriate ensemble is crucial for obtaining physically meaningful results that can be compared with experimental data. This technical guide explores the primary ensembles used in modern MD research, their mathematical foundations, implementation protocols, and applications in scientific discovery.

Fundamental Ensembles in Molecular Dynamics Research

Microcanonical Ensemble (NVE)

The microcanonical ensemble (NVE) represents the simplest case of a completely isolated system that cannot exchange energy or matter with its surroundings [1]. In this ensemble, the number of particles (N), the volume (V), and the total energy (E) all remain constant [2]. The NVE ensemble corresponds to Newton's equations of motion, where the total energy is conserved, though fluctuations between potential and kinetic energy components are still permitted [2].

In practical MD simulations, the microcanonical ensemble is generated by solving Newton's equations without any temperature or pressure control mechanisms [4]. However, due to numerical rounding and truncation errors during the integration process, small energy drifts often occur in practice [4]. Additionally, in integration algorithms like the Verlet leapfrog method, potential and kinetic energies are calculated half a timestep out of synchrony, contributing to fluctuations in the total energy [4].

While the NVE ensemble is mathematically straightforward, it has limitations for practical simulations. A sudden increase in temperature due to energy conservation can cause unstable behavior, such as protein unfolding in biomolecular simulations [2]. For this reason, constant-energy simulations are not generally recommended for equilibration but can be useful during production phases when exploring constant-energy surfaces of conformational spaces without the perturbations introduced by temperature and pressure coupling [4].

Canonical Ensemble (NVT)

The canonical ensemble (NVT) maintains a constant number of particles (N), constant volume (V), and constant temperature (T) [1]. Unlike the isolated NVE system, the NVT ensemble represents a system immersed in a much larger heat bath at a specific temperature, allowing heat exchange across the boundary while keeping matter constant [1].

Temperature control in NVT simulations is typically achieved by scaling particle velocities to adjust the kinetic energy, effectively implementing a thermostat in the simulation [2]. The system exchanges heat with this "thermostat" until thermal equilibrium is reached, maintaining a constant temperature throughout the simulation [1]. This ensemble is particularly important for calculating the Helmholtz free energy of a system, which represents the maximum amount of work a system can perform at constant volume and temperature [1].

In practice, the NVT ensemble is often the default choice in many MD packages, especially for conformational searches of molecules in vacuum without periodic boundary conditions [4]. Without periodic boundaries, volume, pressure, and density are not well-defined, making constant-pressure dynamics impossible [4]. Even with periodic boundaries, the NVT ensemble offers the advantage of less trajectory perturbation compared to constant-pressure simulations, as it avoids coupling to a pressure bath [4].

Isothermal-Isobaric Ensemble (NPT)

The isothermal-isobaric ensemble (NPT) maintains a constant number of particles (N), constant pressure (P), and constant temperature (T) [1]. This ensemble allows for both heat exchange and volume adjustments, with the system volume changing to maintain constant pressure against an external pressure source [2].

Pressure control is implemented through a barostat, which constantly rescales one or multiple dimensions of the simulation box to maintain the target pressure [2]. The NPT ensemble is especially valuable for simulating chemical reactions and biological processes that typically occur under constant pressure conditions in laboratory settings [2] [1]. This ensemble is essential for calculating the Gibbs free energy of a system, representing the maximum work obtainable at constant pressure and temperature [1].

For researchers in drug development, the NPT ensemble is particularly important for simulating biological systems in physiological conditions, where maintaining correct pressure, volume, and density relationships is crucial for obtaining physically meaningful results [4]. This ensemble can be used during equilibration to achieve desired temperature and pressure before potentially switching to other ensembles for data collection [4].

Other Specialized Ensembles

Beyond the three primary ensembles, several specialized ensembles cater to specific research needs:

Grand Canonical Ensemble (μVT): This ensemble maintains constant chemical potential (μ), volume (V), and temperature (T), allowing the number of particles to fluctuate during simulation [2]. The system is open and can exchange both heat and particles with a large reservoir [2]. While theoretically important, this ensemble is not widely supported in most MD software [2].

Constant-Pressure, Constant-Enthalpy Ensemble (NPH): The NPH ensemble is the constant-pressure analogue of the constant-volume, constant-energy ensemble, where enthalpy (H = E + PV) remains constant when pressure is fixed without temperature control [4].

Constant-Temperature, Constant-Stress Ensemble (NST): An extension of the constant-pressure ensemble, the NST ensemble allows control over specific components of the stress tensor, making it particularly useful for studying stress-strain relationships in polymeric or metallic materials [4].

Table 1: Comparison of Primary Thermodynamic Ensembles in Molecular Dynamics

| Ensemble | Constants | Control Method | Primary Applications | Theoretical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microcanonical (NVE) | Number of particles (N), Volume (V), Energy (E) | None (natural dynamics) | Exploring constant-energy surfaces; fundamental mechanics | Models isolated systems; basis for molecular dynamics |

| Canonical (NVT) | Number of particles (N), Volume (V), Temperature (T) | Thermostat (velocity scaling) | Conformational sampling at constant volume; vacuum simulations | Helmholtz free energy calculations |

| Isothermal-Isobaric (NPT) | Number of particles (N), Pressure (P), Temperature (T) | Thermostat + Barostat (volume scaling) | Mimicking laboratory conditions; biomolecular simulations in solution | Gibbs free energy calculations |

| Grand Canonical (μVT) | Chemical potential (μ), Volume (V), Temperature (T) | Particle reservoir | Systems with fluctuating particle numbers; adsorption studies | Open system thermodynamics |

Practical Implementation in Molecular Dynamics Research

Standard Simulation Protocol

In practical MD simulations, researchers typically employ multiple ensembles in sequence rather than relying on a single ensemble throughout the entire simulation. A standard protocol involves a carefully orchestrated sequence of simulations using different ensembles to properly equilibrate the system before production data collection [2]:

The workflow begins with an energy minimization phase to relieve any steric clashes or unrealistic high-energy configurations in the initial structure. This is followed by an NVT equilibration to bring the system to the desired target temperature, allowing the kinetic energy distribution to equilibrate while maintaining a fixed volume [2]. Subsequently, an NPT equilibration phase adjusts the system density to achieve the target pressure, allowing the simulation box size to fluctuate until the proper balance between temperature and pressure is established [2]. Finally, the production simulation is conducted in the appropriate ensemble (typically NPT for biomolecular systems or NVT for specific applications) to collect trajectory data for analysis [2].

This multi-ensemble approach ensures that the system is properly equilibrated in terms of both temperature and pressure before collecting production data, leading to more reliable and physically meaningful results [2].

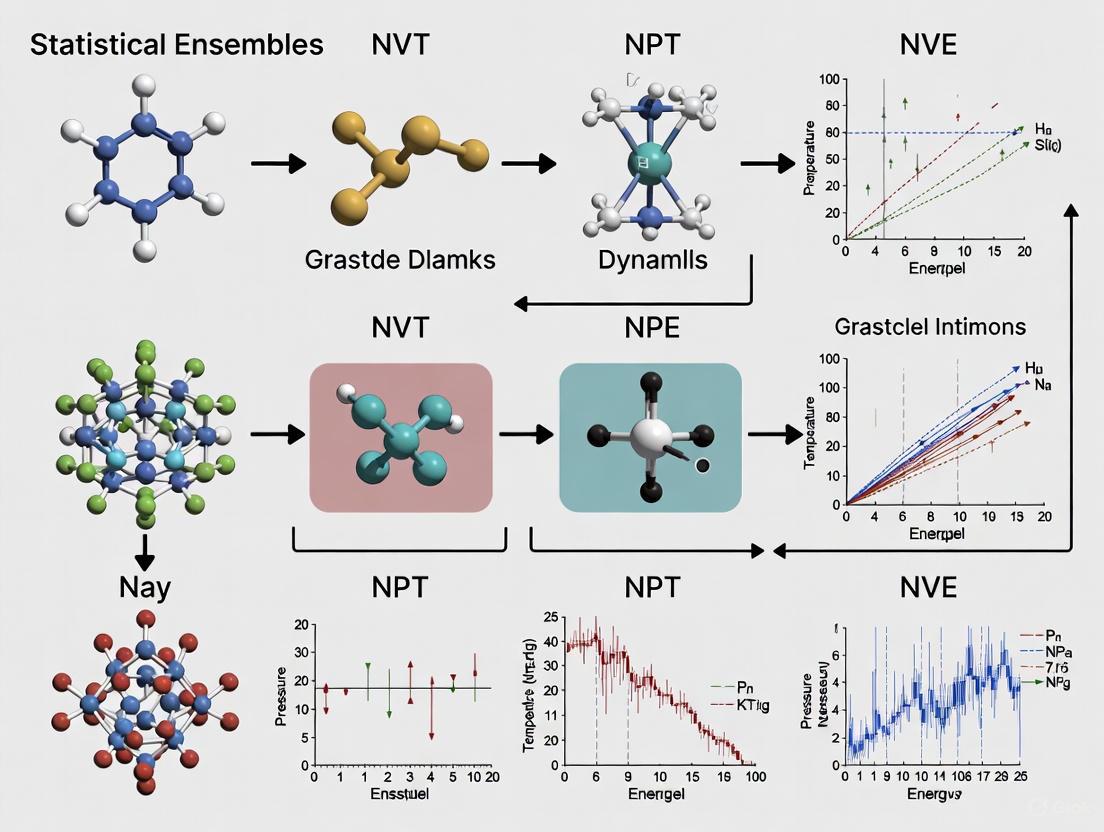

Diagram 1: Standard MD Simulation Workflow

Advanced Applications and Recent Developments

The field of molecular dynamics continues to evolve with new methodologies and computational approaches enhancing the utility of traditional ensembles:

Neural Network Potentials (NNPs) represent a significant advancement, combining the accuracy of quantum mechanics with the computational efficiency of classical force fields. Recent developments like Meta's Open Molecules 2025 (OMol25) dataset and Universal Models for Atoms (UMA) architecture demonstrate how machine learning can enhance traditional MD approaches [5]. These models, trained on massive datasets of high-accuracy quantum chemical calculations, can achieve performance matching high-accuracy density functional theory while remaining computationally tractable for large systems [5].

The eSEN architecture, developed by Meta researchers, improves the smoothness of potential-energy surfaces compared to previous models, making molecular dynamics and geometry optimizations better behaved [5]. A particularly interesting innovation is the two-phase training scheme for conservative-force NNPs, which significantly reduces training time while improving performance [5].

For drug development professionals, these advances enable more accurate simulations of biomolecular systems, including protein-ligand complexes, nucleic acid structures, and dynamic processes that were previously computationally prohibitive [5]. The extensive sampling of biomolecular structures in datasets like OMol25, including various protonation states, tautomers, and docked poses, provides unprecedented coverage of biologically relevant chemical space [5].

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Ensemble Simulations

| Tool/Component | Type | Function in Ensemble Simulation | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thermostat | Algorithm | Maintains constant temperature by scaling velocities | Velocity rescaling, Nosé-Hoover, Berendsen |

| Barostat | Algorithm | Maintains constant pressure by adjusting simulation box dimensions | Berendsen, Parrinello-Rahman |

| Neural Network Potentials (NNPs) | Force field | Provides accurate energy surfaces with quantum mechanical accuracy | eSEN models, UMA architecture |

| Periodic Boundary Conditions | Simulation setup | Eliminates surface effects, enables bulk phase simulation | PBC with Ewald summation for electrostatics |

| Quantum Chemistry Datasets | Training data | Provides reference data for developing accurate potentials | OMol25, SPICE, ANI-2x |

Methodological Considerations for Robust Simulations

Ensuring Proper Phase Space Sampling

A fundamental challenge in molecular dynamics simulations is ensuring adequate sampling of the phase space to obtain statistically meaningful averages. The ergodic hypothesis assumes that over sufficient time, a system will visit all possible states consistent with its energy, making time averages equivalent to ensemble averages [3]. However, in practice, achieving true ergodicity is challenging, especially for complex systems with high energy barriers or rough energy landscapes.

Inadequate phase space sampling manifests as failure to converge properties, inaccurate thermodynamic averages, and poor reproducibility. For a system of N particles, the 6N-dimensional phase space is astronomically large, and practical simulations can only sample a tiny fraction of possible states [3]. Researchers must be vigilant for signs of poor sampling, such as drifts in average properties, failure to observe expected fluctuations, or dependence on initial conditions.

Strategies to improve sampling include extending simulation times, employing enhanced sampling techniques (such as replica exchange or metadynamics), and carefully selecting initial configurations. For drug development applications involving protein-ligand binding or conformational changes, specialized methods are often necessary to adequately sample the relevant states within feasible computational resources.

Current Limitations and Best Practices

While ensembles provide powerful frameworks connecting microscopic and macroscopic worlds, several limitations warrant consideration:

Energy drift in NVE simulations, caused by numerical integration errors, can lead to unphysical behavior over long timescales [4]. Non-conservative force models in some neural network potentials can cause similar issues, though recent advances like conservative-force eSEN models address this limitation [5]. Ensemble equivalence breaks down for small systems or near phase transitions, where fluctuations become significant and different ensembles may yield different results [4].

Best practices for ensemble selection include:

- Using NVT ensemble for systems with fixed volumes or when pressure control is unnecessary

- Employing NPT ensemble for simulating solution conditions or when density is an important variable

- Reserving NVE ensemble for specialized applications where energy conservation is paramount

- Implementing multi-ensemble equilibration protocols before production simulations

- Validating results through multiple independent simulations and convergence tests

For researchers in drug development, proper ensemble selection and implementation is crucial for generating reliable data on binding affinities, conformational dynamics, and solvation effects that can inform the design and optimization of therapeutic compounds.

Thermodynamic ensembles form the essential bridge between the microscopic world of atoms and molecules and the macroscopic thermodynamic properties measured in experiments. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding the principles, applications, and implementation details of these ensembles is crucial for designing robust molecular dynamics simulations and interpreting their results meaningfully.

The continued development of advanced sampling methods, neural network potentials, and increasingly accurate force fields promises to enhance the utility of ensemble-based simulations in scientific discovery and drug development. As these computational approaches become more integrated with experimental research, their role in connecting microscopic behavior to macroscopic observables will only grow in importance.

In molecular dynamics (MD) research, statistical ensembles provide the foundational framework for simulating the thermodynamic behavior of molecular systems. Among these, the microcanonical ensemble, denoted as the NVE ensemble, represents the simplest and most fundamental statistical ensemble. It describes isolated systems characterized by a constant number of particles (N), a constant volume (V), and a constant total energy (E) [6] [2]. The NVE ensemble is a statistical ensemble that represents the possible states of a mechanical system whose total energy is exactly specified [6]. The system is assumed to be isolated in the sense that it cannot exchange energy or particles with its environment, so that the energy of the system does not change with time [6]. This ensemble is of particular importance in MD simulations as it corresponds directly to solving Newton's equations of motion without external thermodynamic controls, making it the natural starting point for understanding molecular dynamics [4] [7].

Table: Key Characteristics of the Microcanonical Ensemble

| Aspect | Description |

|---|---|

| Defining Macroscopic Variables | Number of particles (N), Volume (V), Total Energy (E) [6] |

| System Type | Isolated (no exchange of energy or matter with surroundings) [6] [8] |

| Fundamental Thermodynamic Potential | Entropy (S) [6] |

| Probability Postulate | All accessible microstates with energy E are equally probable [6] [8] |

| Primary Conservation Law | Total energy (E = K + V) is conserved [2] [4] |

Theoretical Foundation

Statistical Mechanical Basis

The microcanonical ensemble is built upon the principle of equal a priori probability, which states that all accessible microstates of an isolated system with a given energy E are equally probable [6] [8]. A microstate is defined by the precise positions and momenta of all N particles in the system, representing a single point in the 6N-dimensional phase space (3 spatial coordinates and 3 momentum components for each particle) [8]. The collection of all microstates with energy between E and E+δE defines the accessible region of phase space for the microcanonical ensemble.

The fundamental thermodynamic quantity derived from the microcanonical ensemble is entropy, which provides the connection between microscopic configurations and macroscopic thermodynamics. According to Boltzmann's formula, the entropy S is related to the number of accessible microstates Ω by:

S = k₠log Ω

where kâ‚ is Boltzmann's constant [6] [8]. This famous equation establishes that entropy quantifies the number of ways a macroscopic state can be realized microscopically. The temperature in the microcanonical ensemble is not an external control parameter but rather a derived quantity defined as the derivative of entropy with respect to energy [6].

Comparison with Other Ensembles

In MD research, the microcanonical ensemble serves as the foundation for understanding other commonly used ensembles. While the NVE ensemble describes isolated systems, most experimental conditions and biological processes require different ensemble representations.

Table: Comparison of Major Statistical Ensembles in Molecular Dynamics

| Ensemble | Constant Parameters | System Type | Common Applications in MD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Microcanonical (NVE) | N, V, E [6] [2] | Isolated [6] | Basic MD simulations; studying energy conservation [4] |

| Canonical (NVT) | N, V, T [2] [4] | Closed, isothermal [9] | Simulating systems at constant temperature [2] |

| Isothermal-Isobaric (NPT) | N, P, T [2] [4] | Closed, isothermal-isobaric [2] | Mimicking laboratory conditions [2] |

| Grand Canonical (μVT) | μ, V, T [2] | Open [2] | Systems exchanging particles with reservoir [2] |

Practical Implementation in Molecular Dynamics

Molecular Dynamics Protocol

In practical MD simulations, the NVE ensemble is implemented by numerically integrating Newton's equations of motion for all atoms in the system. The time evolution of positions and velocities follows from the Hellmann-Feynman forces acting on each atom [10]. A typical MD simulation procedure incorporates multiple ensembles sequentially rather than using a single ensemble throughout the entire simulation process [2].

Figure 1: Standard MD simulation workflow showing the placement of NVE ensemble in the production phase. The workflow progresses from initial structure preparation through equilibration in NVT and NPT ensembles before the final NVE production run for data collection.

Implementing NVE Ensemble in VASP

The Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package (VASP) provides multiple approaches to implement the NVE ensemble for molecular dynamics simulations. The simplest and recommended method involves using the Andersen thermostat with zero collision probability, effectively disabling the thermostat's influence on the system dynamics [10].

Table: NVE Ensemble Implementation Methods in VASP

| Method | MDALGO Setting | Additional Tags | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Andersen Thermostat | 1 [10] | ANDERSEN_PROB = 0.0 [10] |

Simple and recommended approach [10] |

| Nosé-Hoover Thermostat | 2 [10] | SMASS = -3 [10] |

Effectively disables thermostat [10] |

To enforce constant volume throughout an NVE simulation in VASP, the ISIF tag must be set to a value less than 3 [10]. It is important to note that in NVE MD runs, there is no direct control over temperature and pressure, and their average values depend entirely on the initial structure and initial velocities [10]. Therefore, it is often desirable to equilibrate the system using NVT or NPT ensembles before switching to NVE ensemble for production sampling [10].

Example INCAR Configuration for NVE Ensemble

The following example INCAR file illustrates the key parameters for setting up an NVE ensemble molecular dynamics simulation in VASP using the Andersen thermostat approach [10]:

This configuration ensures that the system evolves according to Newton's equations of motion without artificial temperature control, maintaining constant energy throughout the simulation [10].

Research Applications and Protocols

Biomolecular Recognition Studies

The microcanonical ensemble plays a crucial role in studies of biomolecular recognition, which is fundamental to cellular functions such as molecular trafficking, signal transduction, and genetic expression [9]. MD simulations in the NVE ensemble allow researchers to investigate the thermodynamic properties driving these interactions without the artificial influence of thermostats. The statistical mechanics underlying the microcanonical ensemble provides the theoretical framework for connecting atomic-level interactions to macroscopic thermodynamic properties [9].

In practice, the NVE ensemble is particularly valuable for studying the dynamic behavior of biomolecules under conditions that approximate true isolation, allowing researchers to observe natural energy flow between different degrees of freedom. This has been instrumental in understanding the role of configurational entropy and solvent effects in intermolecular interactions [9].

Protein Structure Refinement

Recent advances in protein structure prediction have highlighted the importance of MD simulations for refining predicted protein structures. In a 2023 study comparing multiple neural network-based de novo modeling approaches, molecular dynamics simulations were employed to refine predicted structures of the hepatitis C virus core protein (HCVcp) [11]. The simulations enabled researchers to obtain compactly folded protein structures of good quality and theoretical accuracy, demonstrating that predicted structures often require refinement to become reliable structural models [11].

The key analysis metrics used in these MD refinement protocols include:

- Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD): Measures the average distance between backbone atoms of different structures, providing insight into structural convergence and stability [11] [12].

- Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF): Quantifies the flexibility of specific residues (typically Cα atoms) throughout the simulation [11].

- Radius of Gyration: Assesses the overall compactness of the protein structure [11].

- ERRAΤ and phi-psi plot analysis: Evaluates the quality of the refined protein structures [11].

Table: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for NVE Ensemble Simulations

| Item | Function/Description | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| VASP | First-principles molecular dynamics package [10] | Ab initio NVE simulations of materials [10] |

| ASE (Atomic Simulation Environment) | Python framework for working with atoms [7] | Setting up and running MD simulations [7] |

| ASAP3-EMT | Effective Medium Theory calculator [7] | Fast classical force field for demonstration [7] |

| GROMACS | Molecular dynamics package [2] | Biomolecular NVE simulations [2] |

| ANDERSEN_PROB parameter | Controls collision probability with fictitious heat bath [10] | Implementing NVE ensemble in VASP (set to 0.0) [10] |

| SMASS parameter | Controls mass of Nosé-Hoover virtual degree of freedom [10] | Implementing NVE ensemble in VASP (set to -3) [10] |

Technical Considerations and Limitations

Energy Conservation and Numerical Stability

In practical implementations, true energy conservation in NVE simulations is affected by numerical considerations. While the NVE ensemble theoretically conserves energy, numerical integration algorithms introduce slight drifts due to rounding and truncation errors [4]. For example, in the Verlet leapfrog algorithm, only r(t) and v(t - 1/2t) are known at each timestep, resulting in potential and kinetic energies being half a step out of synchrony [4]. This contributes to fluctuations in the total energy despite the theoretical foundation of energy conservation.

The choice of time step is critical for maintaining numerical stability in NVE simulations. Too large a time step can lead to significant energy drift and integration errors, while too small a time step unnecessarily increases computational cost [7]. For most biomolecular systems, time steps of 1-2 femtoseconds provide a reasonable balance between accuracy and efficiency when using the NVE ensemble [10] [7].

Applicability and System-Specific Considerations

The microcanonical ensemble is not always appropriate for all MD simulation scenarios. Constant-energy simulations are generally not recommended for the equilibration phase because, without energy flow facilitated by temperature control methods, the desired temperature cannot be reliably achieved [4]. The NVE ensemble is most valuable during production phases when researchers are interested in exploring the constant-energy surface of conformational space without perturbations introduced by temperature-bath coupling [4].

For small systems with limited degrees of freedom, the microcanonical ensemble can exhibit unusual thermodynamic behavior, including negative temperatures when the density of states decreases with energy [6]. These limitations make other ensembles more appropriate for many realistic systems that interact with their environment [6] [2].

The microcanonical (NVE) ensemble represents a fundamental approach in molecular dynamics research, providing insights into the behavior of isolated systems with conserved energy. While it has limitations for simulating experimental conditions where temperature and pressure control are essential, its theoretical importance and application in production MD simulations make it an indispensable tool in computational chemistry and biology. As MD methodologies continue to advance, the NVE ensemble maintains its role as the foundational framework for understanding energy conservation and natural system dynamics at the atomic level, particularly in biomolecular recognition studies and protein structure refinement protocols.

Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulation is a powerful computational technique that models the time evolution of a system of atoms and molecules by numerically solving Newton's equations of motion. The foundation of MD relies on statistical mechanics, which connects the microscopic behavior of individual atoms to macroscopic observable properties. This connection is formalized through the concept of statistical ensembles, which define the set of possible microstates a system can occupy under specific external constraints.

The canonical ensemble, or NVT ensemble, is one of the most fundamental and widely used ensembles in MD research. It describes a system that exchanges energy with its surroundings, maintaining a constant number of atoms (N), a constant volume (V), and a constant temperature (T). The temperature fluctuates around an equilibrium value, ⟨T⟩ [13]. This ensemble is particularly valuable for simulating real-world experimental conditions where temperature is a controlled variable, such as in studies of biochemical processes in a thermostatted environment or materials properties at specific temperatures. Its importance is highlighted by its central role in applications ranging from drug discovery, where it helps model solvation and binding [14] [15], to the design of new chemical mixtures for materials science [16].

Theoretical Foundation of the NVT Ensemble

From the Microcanonical (NVE) to the Canonical (NVT) Ensemble

In its purest form, an MD simulation based solely on Newton's equations of motion reproduces the microcanonical ensemble (NVE), where the number of atoms (N), the volume of the simulation box (V), and the total energy (E) are conserved. This corresponds to a completely isolated system that does not exchange energy or matter with its environment [17]. While physically rigorous, the NVE ensemble is often less practical for simulating experimental conditions, where temperature, not total energy, is the controlled variable.

The NVT ensemble relaxes the condition of constant total energy. Instead, the system is coupled to an external heat bath at a desired temperature. This allows the system to exchange energy with the bath, causing its instantaneous temperature to fluctuate around the target value. The temperature of a system is related to the average kinetic energy of the atoms. For a system in equilibrium, the following relation holds: [ \langle T \rangle = \frac{2 \langle Ek \rangle}{(3N - Nc) kB} ] where ⟨T⟩ is the average temperature, ⟨Eₖ⟩ is the average kinetic energy, ( N ) is the number of atoms, ( Nc ) is the number of constraints, and ( k_B ) is Boltzmann's constant. The role of a thermostat in NVT simulations is to manipulate the atomic velocities (and thus the kinetic energy) to maintain this relationship, effectively mimicking the presence of the heat bath.

Thermostating Algorithms: A Comparative Analysis

A key challenge in NVT simulations is controlling the temperature without unduly perturbing the system's natural dynamics. Several thermostating algorithms have been developed, each with a different theoretical approach and practical implications.

Table 1: Comparison of Common Thermostats for NVT Ensemble Simulations

| Thermostat | Underlying Principle | Ensemble Quality | Impact on Dynamics | Typical Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nosé-Hoover (NH) [13] [17] [18] | Deterministic; extends Lagrangian with a fictitious variable and mass representing the heat bath. | Canonical [18]. | Generally low with proper parameters; can exhibit energy drift in solids if potential energy is not accounted for [18]. | Production simulations; general-purpose use. |

| Nosé-Hoover Chains (NHC) [13] [17] | A chain of NH thermostats to control the first thermostat's temperature. | Canonical [18]. | More stable than single NH; suppresses energy drift. | Systems where standard NH shows poor stability. |

| Andersen [13] [18] | Stochastic; randomly assigns new velocities from a Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution. | Canonical. | High; stochastic collisions disrupt the natural dynamics. | Equilibration; sampling for static properties. |

| Berendsen [17] | Weak-coupling; scales velocities to exponentially relax the system to the target temperature. | Not strictly canonical [17] [18]. | Low; suppresses temperature fluctuations too aggressively. | Initial equilibration only. |

| Langevin [13] [17] | Stochastic; adds friction and random noise forces to the equations of motion. | Canonical. | High; friction term damps dynamics. | Equilibration; sampling for static properties. |

| CSVR / Bussi-Donadio-Parrinello [13] [17] | Stochastic; rescales velocities using a stochastic algorithm. | Canonical [17]. | Moderate to low; correct ensemble with less perturbation than Langevin. | Production simulations requiring correct sampling. |

The following diagram illustrates the logical decision process for selecting an appropriate thermostat based on the simulation goals:

Diagram 1: A logic flow for selecting a thermostat in NVT simulations, balancing the need for accurate dynamics, correct ensemble sampling, and computational efficiency.

Practical Implementation of NVT Simulations

Initialization and Equilibration Protocol

A successful NVT simulation requires careful preparation to ensure the system is properly equilibrated before data collection begins.

- System Setup: Begin with a stable initial structure, ideally from a previous geometry optimization or an NpT simulation to relax the lattice degrees of freedom [13]. The simulation box should be large enough to minimize finite-size effects, with cell lengths preferably larger than twice the interaction range of the potential [17].

- Initial Velocities: Atomic velocities are initialized, typically by drawing from a Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution at the target temperature [17] [19]. It is good practice to remove the overall center-of-mass motion to prevent spurious drift of the entire system [17] [19].

- Equilibration Run: The system is evolved under NVT dynamics for a sufficient number of steps until key observables (e.g., potential energy, temperature, pressure) stabilize around a stationary value. The Berendsen thermostat is often recommended for this initial equilibration phase due to its robust and fast relaxation to the target temperature, even though it does not generate a correct canonical ensemble [17].

- Production Run: Once equilibrated, the thermostat is switched to a more rigorous one (e.g., Nosé-Hoover or CSVR) for the production phase, during which the trajectory data is collected for analysis.

Thermostat Configuration and Parameters

The performance of a thermostat depends heavily on its coupling parameters.

- Nosé-Hoover Mass (SMASS in VASP): This parameter (often denoted as Q) determines the coupling strength between the system and the thermal reservoir. A large mass leads to slow, weak coupling and potentially poor temperature control, while a very small mass can cause high-frequency temperature oscillations [13] [18]. It is often set in relation to the system's natural vibrational periods.

- Thermostat Timescale (Ï„): In packages like QuantumATK, this parameter defines how quickly the system temperature approaches the reservoir temperature. A small timescale (tight coupling) forces the temperature to follow the reservoir closely but interferes more with the natural dynamics. A larger timescale (loose coupling) is preferable for measuring dynamical properties [17].

- Friction Coefficient (γ): For the Langevin thermostat, this parameter defines the strength of the frictional force. A higher value results in tighter coupling but more significantly modifies and damps the system's dynamics [17].

- Chain Length: In the Nosé-Hoover Chain thermostat, multiple thermostats are coupled to each other. A typical chain length of 3-5 is often sufficient, but it may need to be increased if persistent temperature oscillations are observed [17].

Table 2: Key Parameters for Different Thermostats in Popular MD Packages

| Thermostat | VASP Tag | QuantumATK Parameter | AMS/GROMACS Parameter | Recommended Value / Guidance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nosé-Hoover | SMASS [13] |

Thermostat timescale [17] |

Tau (in Thermostat block) [20] |

VASP: -1 (Nose-Hoover chains), 0 (Nose-Hoover), >0 (mass); QuantumATK: System-dependent, e.g., 100 fs. |

| Andersen | ANDERSEN_PROB [13] |

- | - | Probability of collision per atom per timestep. |

| Langevin | LANGEVIN_GAMMA [13] |

Friction [17] |

- | Friction coefficient in psâ»Â¹. Lower for better dynamics. |

| CSVR | CSVR_PERIOD [13] |

- | - | Period of the stochastic velocity rescaling. |

| Berendsen | - | Thermostat timescale [17] |

Tau (in Thermostat block) [20] |

Good for equilibration; use a relatively short timescale. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Components for an NVT Simulation

Table 3: Key "Research Reagent Solutions" for NVT Molecular Dynamics

| Item / Component | Function in NVT Simulation | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Thermostat Algorithm | Controls the system temperature by mimicking energy exchange with a heat bath. | Choice depends on the need for a correct ensemble (e.g., Nosé-Hoover) vs. fast equilibration (e.g., Berendsen) [13] [17]. |

| Initial Coordinates (POSCAR) | Defines the starting atomic positions and simulation box. | The volume is fixed in NVT; initial box should be well-equilibrated from a previous NpT run or optimization [13]. |

| Maxwell-Boltzmann Velocity Distribution | Provides physically realistic initial atomic velocities. | Generated at the desired temperature; centers-of-mass motion should be removed [17] [19]. |

| Force Field / Potential | Computes the potential energy and forces between atoms. | Can be empirical (classical) or quantum mechanical (e.g., DFT); determines the physics of the interaction [17] [15]. |

| Time Step (Δt) | The discrete interval for numerical integration of equations of motion. | Must be small enough to resolve the highest atomic vibrations (e.g., 0.5-2 fs); critical for energy conservation [17]. |

| Simulation Software | The computational engine that performs the integration, force calculation, and temperature control. | Examples: VASP [13], QuantumATK [17], AMS [20], GROMACS [15] [19]. |

| Enpp-1-IN-6 | Enpp-1-IN-6, MF:C22H28N4O5S, MW:460.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Bimatoprost-d4 | Bimatoprost-d4, MF:C25H37NO4, MW:419.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

NVT Ensemble in Action: Applications in Drug Discovery and Materials Science

The NVT ensemble's ability to model systems at constant temperature makes it indispensable across scientific fields. A prominent application is in drug discovery, where MD simulations are used to study target structures, predict binding poses, and optimize lead compounds [14]. A specific example is the prediction of a critical physicochemical property: aqueous solubility.

A recent study integrated NVT (and NPT) MD simulations with machine learning to identify key molecular properties influencing drug solubility [15] [21]. The researchers ran MD simulations for 211 diverse drugs and extracted ten MD-derived properties. These properties, along with the experimental octanol-water partition coefficient (logP), were used as features to train machine learning models. The study found that seven properties were highly effective in predicting solubility: logP, Solvent Accessible Surface Area (SASA), Coulombic interaction energy (Coulombic_t), Lennard-Jones interaction energy (LJ), Estimated Solvation Free Energy (DGSolv), Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD), and the Average number of solvents in the Solvation Shell (AvgShell) [15] [21]. This demonstrates how the NVT ensemble can generate trajectory data for calculating interaction energies and structural dynamics, which are valuable descriptors for predicting macroscopic properties.

The workflow for this application is summarized in the following diagram:

Diagram 2: Workflow for using NVT-based MD simulations to generate features for machine learning prediction of drug solubility.

In materials science, the NVT ensemble is used in high-throughput screening of chemical mixtures. For instance, a large-scale study generated a dataset of over 30,000 solvent mixtures using MD simulations to predict properties like packing density and enthalpy of mixing [16]. These simulation-derived properties showed strong correlation with experimental data (R² ≥ 0.84), validating the use of NVT simulations as a reliable and consistent method for generating data to train machine learning models for materials design [16].

The canonical (NVT) ensemble is a cornerstone of modern molecular dynamics research, enabling the simulation of systems under constant temperature conditions that mirror a vast array of laboratory experiments. Its implementation, through a variety of thermostating algorithms like Nosé-Hoover and CSVR, provides a robust link between microscopic atomic motions and macroscopic thermodynamic properties. As demonstrated by its growing application in data-driven drug discovery and materials design—where it helps generate essential physical properties for machine learning models—the NVT ensemble remains a vital tool. Its proper use, with careful attention to thermostat selection and equilibration protocols, allows researchers and developers to gain profound insights into the behavior of molecules and materials, accelerating innovation across scientific and industrial domains.

Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations utilize statistical ensembles to define the thermodynamic conditions of a system. The Isothermal-Isobaric ensemble, universally known as the NPT ensemble, maintains a constant number of particles (N), constant pressure (P), and constant temperature (T). This ensemble holds fundamental importance in molecular simulation research because it directly mirrors the constant temperature and pressure conditions maintained in most laboratory experiments [22] [2]. While all ensembles are equivalent in the thermodynamic limit, switching between ensembles for finite-size systems can be challenging. The NPT ensemble is indispensable for studying systems where density is not known a priori, such as solvated proteins, membranes, micelles, or liquid mixtures [23].

In the broader taxonomy of statistical ensembles, NPT occupies a crucial position between the canonical NVT ensemble (constant volume) and the grand canonical μVT ensemble (constant chemical potential). It describes closed, isothermal systems that exchange energy and volume with their surroundings, making it the ensemble of choice for simulating most physical and chemical processes under realistic experimental conditions [22] [24]. The characteristic thermodynamic potential for this ensemble is the Gibbs free energy, connecting microscopic simulations to macroscopic thermodynamic properties [22] [24].

Theoretical Foundation

Statistical Mechanical Definition

The NPT ensemble describes equilibrium systems that exchange energy and volume with their surroundings, characterized by fixed temperature (T), pressure (P), and number of particles (N) [22]. The partition function for a classical NPT system provides the fundamental connection between microscopic behavior and macroscopic thermodynamics.

For a classical system, the isobaric-isothermal partition function, Δ(N,P,T), is derived from the canonical partition function Z(N,V,T) by incorporating volume fluctuations [22]:

$$ \Delta(N,P,T) = \int Z(N,V,T) e^{-\beta PV} C dV $$

Here, β = 1/kBT, where kB is Boltzmann's constant, and C is a constant that ensures proper normalization [22]. The probability of observing a specific microstate i with energy Ei and volume Vi is given by:

$$ pi = \frac{1}{\Delta(N,P,T)} e^{-\beta (Ei + PV_i)} $$

For quantum systems, the formulation requires a semiclassical density operator that accounts for the parametric dependence of the Hamiltonian on volume [24].

Thermodynamic Connections

The partition function Δ(N,P,T) directly connects to the Gibbs free energy, the thermodynamic characteristic function for variables N, P, and T [22] [24]:

$$ G(N,P,T) = -k_B T \ln \Delta(N,P,T) $$

This relationship enables the derivation of all relevant thermodynamic properties through appropriate differentiation [24]:

- Volume: $V = \left(\frac{\partial G}{\partial P}\right)_{T,N}$

- Entropy: $S = -\left(\frac{\partial G}{\partial T}\right)_{P,N}$

- Chemical Potential: $\mul = \left(\frac{\partial G}{\partial Nl}\right)_{T,P,N'}$

The enthalpy H = E + PV emerges as the central energy quantity, with fluctuations in H + PV related to the constant-pressure heat capacity [24]:

$$ CP = kB \beta^2 \langle [ (H+PV) - \langle H+PV \rangle ]^2 \rangle $$

Table 1: Thermodynamic Relations in the NPT Ensemble

| Thermodynamic Quantity | Statistical Mechanical Expression | Relationship to Partition Function |

|---|---|---|

| Gibbs Free Energy (G) | -kBT lnΔ(N,P,T) | Fundamental potential |

| Average Volume (⟨V⟩) | -kBT(∂lnΔ/∂P)T,N | First pressure derivative |

| Entropy (S) | kBT(∂lnΔ/∂T)P,N + kBlnΔ | Temperature derivative |

| Constant-Pressure Heat Capacity (CP) | kBβ²⟨δ(H+PV)²⟩ | Second β derivative |

Practical Implementation in Molecular Dynamics

Barostat and Thermostat Coupling

Implementing NPT conditions in MD simulations requires algorithms to control both temperature (thermostat) and pressure (barostat). Modern approaches combine novel features to create highly efficient and accurate numerical integrators [23]. The COMPEL algorithm exemplifies this trend, exploiting molecular pressure concepts, rapid stochastic relaxation to equilibrium, exact calculation of long-range force contributions, and Trotter expansion to generate a robust, stable, and accurate algorithm [23].

Thermostat methods include:

- Velocity rescaling: Direct adjustment of particle velocities

- Langevin dynamics: Stochastic terms that mimic thermal bath interactions

- Nosé-Hoover dynamics: Extended system with auxiliary variables that generate canonical distributions [23]

Barostat methods control pressure by allowing the simulation cell volume to fluctuate. The extended system approach of Andersen maintains pressure through an additional "piston" degree of freedom [23]. A significant advancement is the "Langevin piston" method, which couples an under-damped Langevin dynamics process to the piston equation to control oscillations and reduce relaxation time [23].

Molecular Pressure Formulation

The concept of "molecular pressure" provides significant advantages for molecular systems. Rather than using atomic positions and momenta, molecular pressure calculates the pressure using centers of mass of molecules [23]. This approach avoids complications from covalent bonding forces, as only non-bonding interactions contribute to the pressure calculation.

The equivalence between molecular and atomic formulations of pressure was first proved by Ciccotti and Ryckaert [23]. Molecular pressure provides two key advantages:

- Only inter-molecular forces contribute to the virial calculation

- Reduced pressure fluctuations by excluding rapidly changing covalent potential forces [23]

This formulation is particularly beneficial when holonomic constraints are applied to bond lengths, as it eliminates the need for special treatment of constraint forces in pressure calculation [23].

Barostat Methodologies: A Comparative Analysis

Parrinello-Rahman Barostat

The Parrinello-Rahman method is an extended system approach that allows all degrees of freedom of the simulation cell to vary [25]. The equations of motion incorporate additional variables that control cell deformation:

Here, h = (a, b, c) represents the cell vectors, η controls pressure fluctuations, ζ controls temperature fluctuations, and τT and τP are time constants for thermostat and barostat coupling, respectively [25].

A critical parameter in Parrinello-Rahman implementations is pfactor, which equals Ï„P²B, where B is the bulk modulus [25]. For crystalline metal systems, values between 10â¶-10â· GPa·fs² provide good convergence and stability [25].

Berendsen Barostat

The Berendsen barostat provides an alternative approach that efficiently controls pressure for convergence, though it doesn't generate exact NPT distributions [26]. It couples the system to a pressure bath using first-order kinetics:

Key parameters include barostat_timescale (time constant for pressure coupling) and compressibility (relating volume changes to pressure changes) [26]. The Berendsen method can operate in two modes: isotropic coupling (all cell vectors scaled equally) or anisotropic coupling (cell vectors rescaled independently) [26].

Table 2: Comparison of Barostat Methods in MD Simulations

| Feature | Parrinello-Rahman | Berendsen | Langevin Piston |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ensemble | Correct NPT sampling | Approximately correct | Correct NPT with stochastic elements |

| Cell Flexibility | Full variable cell shape and size | Isotropic or anisotropic scaling | Variable with stochastic control |

| Key Parameters | pfactor (τP²B) | barostat_timescale, compressibility | Piston mass, friction coefficient |

| Implementation | Extended system with equations for η | First-order coupling to bath | Langevin dynamics on piston |

| Advantages | High flexibility, correct sampling | Efficient convergence | Controlled oscillations, rapid equilibrium |

| Limitations | Sensitive to parameter choice | Does not generate exact NPT | Additional noise from stochastic elements |

Integration Schemes

Modern NPT implementations use symmetric Trotter expansions of the Liouville operator to create efficient integrators [23]. This approach dates to Ruth's work on symplectic integration and has been extended to stochastic differential equations. The under-damped Langevin equation for the piston can be decomposed into Hamiltonian components and Ornstein-Uhlenbeck equations, with the integrator constructed by composing Hamiltonian flows with exact distributional solutions of the linear stochastic system [23].

Applications in Research and Drug Development

Materials Science Applications

NPT simulations enable the investigation of fundamental material properties under realistic experimental conditions:

- Thermal expansion coefficients: By measuring volume changes across temperatures at constant pressure [25]

- Phase transitions: Observing structural changes in solids under varying pressure-temperature conditions

- Equation of state determination: Relating pressure, volume, and temperature for pure systems [22]

- Melting point prediction: Identifying solid-liquid phase transitions through gradual heating [25]

For example, calculating the thermal expansion coefficient of fcc-Cu involves running NPT simulations at temperature increments from 200K to 1000K with external pressure fixed at 1 bar, then determining the lattice constant at each temperature [25].

Pharmaceutical and Biomolecular Applications

In drug development, the NPT ensemble plays crucial roles in understanding molecular behavior under physiological conditions:

- Membrane-protein interactions: Studying lipid bilayers and embedded proteins at biological pressure and temperature [23]

- Solvated protein dynamics: Modeling proteins in aqueous environments at constant pressure

- Density prediction: Determining fluid-phase densities for drug delivery systems [25]

The Model-Informed Drug Development (MIDD) framework leverages computational approaches, including MD simulations, to optimize drug development pipelines [27]. Accurate modeling of biomolecular systems requires proper treatment of long-range interactions, as cutoff schemes for Lennard-Jones interactions can introduce deviations up to 5% in lipid bilayer order parameters [23].

Diagram 1: NPT Ensemble in Drug Development Workflow. The NPT ensemble bridges laboratory conditions and computational prediction of key drug properties.

Computational Protocols and Parameters

Typical Simulation Workflow

A standard MD procedure employs multiple ensembles sequentially for proper system equilibration [2]:

- NVT equilibration: Bringing the system to desired temperature with fixed volume

- NPT equilibration: Adjusting density to achieve target pressure at constant temperature

- Production run: Extended NPT simulation for data collection under equilibrium conditions [2]

This protocol ensures the system reaches proper equilibrium before production data collection begins.

Parameter Selection Guidelines

Successful NPT simulations require careful parameter selection:

- Time step: Typically 1-2 fs for atomistic simulations with bonds involving hydrogen [25]

- Thermostat time constant (Ï„T): 20-100 fs for gradual coupling [25]

- Barostat time constant (Ï„P): Should exceed Ï„T by approximately 5-fold for stability [26]

- Pressure coupling: Compressibility values of ~1×10â»â´ barâ»Â¹ for aqueous systems [26]

For the Parrinello-Rahman method in ASE, typical pfactor values range from 10â¶-10â· GPa·fs² for metal systems [25]. In VASP implementations, fictitious masses (PMASS) for lattice degrees of freedom around 1000 amu provide reasonable dynamics [28].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for NPT Ensemble Research

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function in NPT Research |

|---|---|---|

| MD Software Packages | MOIL, ASE, GROMACS, VASP, QuantumATK | Implement NPT algorithms and integration schemes |

| Force Fields | AMBER, CHARMM, Martini, EMT | Define interatomic potentials for pressure calculation |

| Barostat Algorithms | Parrinello-Rahman, Berendsen, Langevin Piston | Control pressure during simulation |

| Analysis Tools | VMD, MDAnalysis, in-house scripts | Extract volume fluctuations, stress tensor components |

| Long-Range Solvers | Particle Mesh Ewald, PPPM | Accurate electrostatic and dispersive pressure contributions |

Advanced Considerations

Long-Range Interaction Treatment

Accurate pressure calculation requires proper treatment of long-range non-bonded forces. The Ewald summation method provides exact calculation of electrostatic contributions to the pressure [23]. Recently, similar approaches have been applied to Lennard-Jones interactions, as truncation at typical cutoffs (10Ã…) introduces pressure errors of hundreds of atmospheres due to neglected attractive interactions [23].

For anisotropic systems like membranes and proteins, the long-range correction can be calculated by measuring pressure with a very long distance cutoff periodically during simulation [23]. Implementation in the COMPEL algorithm combines molecular pressure with Ewald summation for long-range forces (thus the acronym: COnstant Molecular Pressure with Ewald sum for Long range forces) [23].

Specialized Ensembles and Extensions

The NPT ensemble forms part of a hierarchy of statistical ensembles. The μPT ensemble represents the natural extension, describing systems that exchange energy, particles, and volume with their surroundings [29]. This ensemble is particularly relevant for systems confined within porous and elastic membranes, small systems, and nanothermodynamics where the Gibbs-Duhem equation may not hold [29].

The generalized Boltzmann distribution provides a unifying framework:

$$ p(\mu, \mathbf{x}) = \frac{1}{\mathcal{Z}} \exp[-\beta \mathcal{H}(\mu) + \beta \mathbf{J} \cdot \mathbf{x}] $$

where for the NPT ensemble, J = -P and x = V [22].

Diagram 2: Relationship Between Statistical Ensembles. The NPT ensemble occupies a central position in the hierarchy of statistical mechanical ensembles.

The Isothermal-Isobaric ensemble represents an essential tool in molecular simulation research, providing the crucial link between computational modeling and experimental laboratory conditions. Through continuous algorithmic improvements—including molecular pressure formulations, advanced barostat methods, and exact long-range force calculations—NPT simulations have achieved high efficiency and accuracy in sampling condensed-phase systems.

As molecular dynamics continues to expand its applications in materials science and drug development, the NPT ensemble remains foundational for predicting material properties, biomolecular behavior, and phase equilibria under realistic conditions. Future developments will likely focus on improved scalability for complex systems, enhanced accuracy through machine-learning potentials, and tighter integration with experimental data through the Model-Informed Drug Development framework.

{#topic}

The Grand Canonical (μVT) Ensemble: Open Systems with Fluctuating Particle Number

The grand canonical ensemble stands as a cornerstone of statistical mechanics, providing the fundamental framework for describing open systems that can exchange both energy and particles with a reservoir. This in-depth technical guide explores the core principles, thermodynamic relations, and growing applications of the µVT ensemble, with a specific focus on its role in molecular dynamics (MD) research. For scientists and drug development professionals, understanding this ensemble is key to modeling critical processes such as biomolecular binding, phase transitions, and adsorption, where particle number fluctuations are not merely incidental but central to the phenomenon of interest. This review synthesizes theoretical foundations with practical simulation methodologies, detailing how the grand canonical ensemble enables the calculation of essential thermodynamic properties like binding free energies and provides unique insights into fluctuating systems that are difficult to capture with closed-ensemble approaches.

In statistical mechanics, the choice of ensemble dictates how a system's microscopic states are connected to its macroscopic thermodynamic properties. The grand canonical ensemble, also known as the µVT ensemble, describes the probabilistic state of an open system in thermodynamic equilibrium with a reservoir, with which it can exchange both energy and particles [30]. This makes it distinct from the more commonly encountered microcanonical (NVE), canonical (NVT), and isothermal-isobaric (NPT) ensembles, which assume a fixed number of particles. The independent thermodynamic variables for the grand canonical ensemble are the chemical potential (µ), volume (V), and temperature (T) [30].

The applicability of the grand canonical ensemble extends to systems of any size, but it is particularly crucial for modeling small systems where particle number fluctuations are significant, or for processes inherently involving mass exchange, such as adsorption, permeation, and binding [30] [31]. In the context of a broader thesis on statistical ensembles in MD research, the grand canonical ensemble represents the most general case for open systems, providing a foundation for understanding when particle number fluctuations must be explicitly accounted for to obtain accurate thermodynamic descriptions.

The probability ( P ) of the system being in a particular microstate with energy ( E ) and particle numbers ( N1, N2, \dots, Ns ) is given by the generalized Boltzmann distribution [30]: [ P = e^{(\Omega + \mu1 N1 + \mu2 N2 + \dots + \mus N_s - E)/(kT)} ] Here, ( k ) is the Boltzmann constant, ( T ) is the absolute temperature, and ( \Omega ) is the grand potential, a key thermodynamic potential for the µVT ensemble which serves to normalize the probability distribution.

An alternative formulation uses the grand canonical partition function, ( \mathcal{Z} = e^{-\Omega/(kT)} ), to express the probability as: [ P = \frac{1}{\mathcal{Z}} e^{(\mu N - E)/(kT)} ] The grand potential ( \Omega ) can be directly calculated from the partition function summing over all microstates: [ \Omega = -kT \ln \left( \sum_{\text{microstates}} e^{(\mu N - E)/(kT)} \right) ]

Core Principles and Thermodynamic Relations

The grand potential ( \Omega ) provides a direct link to the macroscopic thermodynamics of the open system. Its exact differential is given by [30]: [ d\Omega = -S dT - \langle N1 \rangle d\mu1 \ldots - \langle Ns \rangle d\mus - \langle p \rangle dV ] This relation reveals that the partial derivatives of ( \Omega ) yield the ensemble averages of key thermodynamic quantities:

- The average number of particles of each component: ( \langle Ni \rangle = -\frac{\partial \Omega}{\partial \mui} )

- The average pressure: ( \langle p \rangle = -\frac{\partial \Omega}{\partial V} )

- The entropy: ( S = -\frac{\partial \Omega}{\partial T} )

Furthermore, the average energy ( \langle E \rangle ) of the system can be obtained from the grand potential through the following fundamental relation [30]: [ \langle E \rangle = \Omega + \sum{i} \langle Ni \rangle \mui + ST ] The differential of this average energy resembles the first law of thermodynamics, but with average signs on the extensive quantities [30]: [ d\langle E \rangle = T dS + \sum{i} \mui d\langle Ni \rangle - \langle p \rangle dV ]

Fluctuations and Ensemble Equivalence

A defining characteristic of the grand canonical ensemble is that it allows for fluctuations in both energy and particle number. The variances of these fluctuations are directly related to thermodynamic response functions [30] [31].

The particle number fluctuation is directly connected to the isothermal compressibility, ( \kappaT ) [31]: [ \frac{\overline{(\Delta n)^2}}{\bar{n}^2} = \frac{kT \kappaT}{V} ] where ( n = N/V ) is the particle density. Similarly, the energy fluctuation in the grand canonical ensemble is given by [30] [31]: [ \overline{(\Delta E)^2} = \langle E^2 \rangle - \langle E \rangle^2 = kT^2 CV + \left[ \left(\frac{\partial U}{\partial N}\right){T,V} \right]^2 \overline{(\Delta N)^2} ] This shows that the energy fluctuation has two contributions: one from the canonical ensemble (( kT^2 C_V )) and an additional term arising from particle number fluctuations.

Ordinarily, for large systems far from critical points, the relative root-mean-square fluctuations are negligible, on the order of ( N^{-1/2} ). This underpins the equivalence of ensembles in the thermodynamic limit, where results from the microcanonical, canonical, and grand canonical ensembles converge [31] [32]. However, this equivalence breaks down near phase transitions. For instance, at the liquid-vapor critical point, the compressibility ( \kappa_T ) diverges, leading to anomalously large particle number fluctuations [31] [33]. In such regimes, the grand canonical ensemble becomes essential for a correct physical description, as it naturally incorporates these large fluctuations.

Table 1: Key Thermodynamic Relations in the Grand Canonical Ensemble

| Thermodynamic Quantity | Mathematical Expression | Relation to Grand Potential |

|---|---|---|

| Average Particle Number | ( \langle N_i \rangle ) | ( \langle Ni \rangle = -\left( \frac{\partial \Omega}{\partial \mui} \right){T,V,\mu{j \neq i}} ) |

| Entropy | ( S ) | ( S = -\left( \frac{\partial \Omega}{\partial T} \right)_{V,\mu} ) |

| Average Pressure | ( \langle p \rangle ) | ( \langle p \rangle = -\left( \frac{\partial \Omega}{\partial V} \right)_{T,\mu} ) |

| Average Energy | ( \langle E \rangle ) | ( \langle E \rangle = \Omega + \sumi \langle Ni \rangle \mu_i + ST ) |

| Particle Number Fluctuation | ( \overline{(\Delta N)^2} ) | ( \overline{(\Delta N)^2} = kT \left( \frac{\partial \langle N \rangle}{\partial \mu} \right)_{T,V} ) |

The Grand Canonical Ensemble in Molecular Dynamics Research

In the landscape of MD research, the choice of statistical ensemble is a fundamental decision that aligns the simulation with the experimental conditions or the physical processes of interest [32]. While the microcanonical (NVE) ensemble is the most natural for simulating isolated systems governed by Newton's equations, most biological and chemical processes occur in environments where temperature and, critically, particle exchange are controlled.

Ensemble Selection for Biomolecular Recognition

For processes like biomolecular recognition—the non-covalent interaction of biomolecules central to cellular functions like signal transduction and drug targeting—the grand canonical ensemble provides a powerful lens [9]. When calculating binding free energies, the relevant thermodynamic potential is often the Gibbs free energy, which is naturally connected to the isothermal-isobaric (NPT) ensemble. However, the grand canonical perspective is particularly insightful when the binding process involves the displacement of water molecules or ions from the binding site. In such cases, the system is effectively open to the exchange of these small particles with the bulk solvent, making the grand canonical ensemble a physically apt description for the binding site region [9].

The practical application of the µVT ensemble in MD has historically been less common than NVT or NPT due to the technical challenge of simulating particle exchange. However, its development was highly desirable because MD simulations, with their finite system sizes, do not automatically reach the thermodynamic limit where ensembles are equivalent [32]. Consequently, results can differ depending on the ensemble, making it crucial to employ the ensemble that most accurately reflects the experimental conditions or the nature of the process.

A Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key methodological "reagents" or computational tools used in grand canonical MD simulations and related free energy calculations.

Table 2: Essential Materials and Methods for Free Energy Calculations in MD

| Method / Tool | Function in Analysis |

|---|---|

| Lennard-Jones Fluid Model | A classical model system for simulating simple liquids and studying fundamental phenomena like critical point fluctuations [33]. |

| Alchemical Transformation | A computational method for calculating free energy differences by gradually transforming one molecule or system into another via a non-physical pathway [9]. |

| Potential of Mean Force (PMF) | The free energy as a function of a reaction coordinate, used to profile energy barriers and stable states in processes like binding or permeation [9]. |

| Thermostats (e.g., Nosé-Hoover) | Algorithms that maintain a constant temperature in NVT or µVT simulations by coupling the system to a heat bath [32]. |

| Isothermal Compressibility (( \kappa_T )) | A thermodynamic property that can be measured in simulations; its divergence is a signature of a critical point and is linked to large particle number fluctuations in the µVT ensemble [31]. |

| Terbutaline-d3 | Terbutaline-d3, MF:C12H19NO3, MW:228.30 g/mol |

| Lsd1-IN-6 | Lsd1-IN-6, MF:C15H13BrN2O3, MW:349.18 g/mol |

Experimental and Simulation Protocols

Implementing the grand canonical ensemble in molecular dynamics simulations requires specialized techniques to manage particle exchange. The following workflow and diagram outline a general protocol for conducting a grand canonical MD simulation, particularly for studying phenomena like critical points.

Diagram 1: Grand Canonical MD Simulation Workflow

A common and powerful approach is to hybridize MD with Grand Canonical Monte Carlo (GCMC) steps, as illustrated in Diagram 1. The protocol can be broken down as follows:

System Setup: Define the simulation box (fixed volume, V) and specify the chemical potential (µ) of the species of interest and the temperature (T). The chemical potential is typically pre-calculated for a bulk reservoir under known conditions (e.g., using a separate simulation of a bulk system at the desired pressure) [33].

Initial Equilibration: The system is first equilibrated under a different ensemble, often NVT or NPT, to establish a reasonable initial configuration and density.

GCMC/MD Hybrid Cycle: The core of the simulation involves a cyclic process:

- GCMC Step: A series of Monte Carlo moves are attempted, including particle insertions and deletions. The acceptance of these moves is based on the Metropolis criterion, which depends on the specified chemical potential µ. This step is responsible for regulating the particle number [33].

- MD Step: Following the GCMC step, a short segment of standard molecular dynamics is run. This evolves the system's coordinates and velocities under Newton's laws, sampling the phase space for the current number of particles. The MD step handles energy redistribution and relaxation.

Sampling and Analysis: Throughout the hybrid simulation, the instantaneous particle number N and total energy E are recorded. Their averages (〈N〉, 〈E〉) and fluctuations (〈(ΔN)²〉, 〈(ΔE)²〉) are calculated from this trajectory data. As derived from the core principles, these fluctuations can be used to compute properties like the isothermal compressibility, which exhibits characteristic behavior near critical points [31] [33].

Visualization of Particle Number Fluctuations at Criticality

The grand canonical ensemble's power to capture large fluctuations is most evident near critical points. Molecular dynamics simulations of classical fluids, such as the Lennard-Jones fluid, can directly visualize this phenomenon.

Diagram 2: Particle Number Fluctuations at Criticality

Diagram 2 provides a conceptual illustration of particle number fluctuations within a fixed sub-volume of a system. Under normal conditions (far from a critical point), density fluctuations are small and local, leading to a relatively uniform particle distribution. In contrast, near a critical point (e.g., the liquid-vapor critical point of a fluid), the compressibility diverges, and the system exhibits large-scale, long-wavelength density fluctuations [31]. This results in significant spatial heterogeneity, with some regions having a density much higher than the average and others much lower. These fluctuations are a direct manifestation of the system sampling a wide range of particle numbers in the grand canonical ensemble, and they are responsible for macroscopic phenomena like critical opalescence [31]. Modern MD studies explicitly track these fluctuations to locate critical points and study critical exponents [33].

Table 3: Particle Number Fluctuations in Different Regimes

| System Condition | Relative Fluctuation ( \frac{\sqrt{\overline{(\Delta N)^2}}}{\langle N \rangle} ) | Physical Origin | Implication for Simulation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Far from Critical Point | ( O(N^{-1/2}) ) (Negligible) | Random, uncorrelated particle motions. | Ensembles (NVT, NPT, µVT) are effectively equivalent. |

| At Critical Point | ( \gg O(N^{-1/2}) ) (Large, scaling with system size) | Divergence of compressibility and long-range correlations [31]. | Grand canonical ensemble is essential; other ensembles may yield incorrect results. |

Current research continues to leverage the grand canonical ensemble to tackle complex problems in molecular simulation. For instance, studies using classical Lennard-Jones fluids investigate how the large particle number fluctuations at a critical point are manifested differently when measurements are taken in coordinate space versus when momentum-space cuts are applied, with implications for interpreting event-by-event fluctuations in heavy-ion collision experiments [33].

In summary, the grand canonical (µVT) ensemble is an indispensable part of the statistical mechanics toolkit for MD research, especially when dealing with open systems. Its ability to naturally incorporate particle number fluctuations makes it uniquely suited for studying adsorption, binding, phase transitions, and critical phenomena. While technical challenges in its implementation remain, the development of robust hybrid GCMC/MD methods and a deeper understanding of fluctuation signatures ensure that the grand canonical ensemble will continue to provide critical insights at the intersection of physics, chemistry, and biology, ultimately aiding in the rational design of therapeutics and materials.

Implementing Ensembles for Biomolecular Simulation: Methods and Real-World Applications

In the field of molecular dynamics (MD) research, a statistical ensemble is an idealization consisting of a large number of virtual copies of a system, considered simultaneously, each representing a possible state that the real system might be in [34]. This fundamental concept, introduced by J. Willard Gibbs in 1902, provides the theoretical foundation for connecting microscopic molecular behavior to macroscopic thermodynamic observables [34]. In molecular dynamics simulations, the choice of statistical ensemble is paramount as it determines which thermodynamic quantities are conserved during the simulation and directly controls the sampling of phase space. The ensemble effectively represents the collection of possible microscopic states compatible with specific predetermined macroscopic variables, such as temperature or molecular concentration [35]. Understanding how to map simulation goals to appropriate thermodynamic conditions is therefore essential for obtaining physically meaningful results from MD simulations, particularly in biological applications such as drug development where accurate representation of molecular behavior under physiological conditions is critical.

Fundamental Ensemble Types and Their Physical Significance

Core Thermodynamic Ensembles

Statistical ensembles in molecular dynamics simulations are defined by their associated thermodynamic constraints and conserved quantities. The three primary ensembles form the foundation of most MD simulations, each tailored to specific experimental conditions and research questions.

Table 1: Fundamental Ensembles in Molecular Dynamics

| Ensemble Type | Conserved Quantities | Thermodynamic State | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Microcanonical (NVE) | Number of particles (N), Volume (V), Energy (E) | Totally isolated system | Study of inherent dynamics without external influence; fundamental properties |

| Canonical (NVT) | Number of particles (N), Volume (V), Temperature (T) | System in thermal equilibrium with heat bath | Simulations at physiological temperature; standard biomolecular studies |

| Grand Canonical (μVT) | Chemical potential (μ), Volume (V), Temperature (T) | Open system exchanging particles and energy | Processes with changing particle number; binding studies, adsorption |

The microcanonical ensemble (NVE) describes completely isolated systems that cannot exchange energy or particles with their environment [34]. In this ensemble, all members have identical total energy and particle number, making it useful for studying the inherent dynamics of a system without external perturbations. The canonical ensemble (NVT) is appropriate for closed systems in thermal contact with a heat bath at fixed temperature [34]. This ensemble is particularly relevant for biological simulations where temperature is a controlled experimental parameter. The grand canonical ensemble (μVT) describes open systems that can exchange both energy and particles with their environment [34], making it valuable for studying processes like ligand binding or molecular adsorption where particle number fluctuates.

Extended and Specialized Ensembles

Beyond the three fundamental ensembles, specialized ensembles have been developed to address specific challenges in molecular simulations. The isothermal-isobaric ensemble (NPT) maintains constant number of particles, pressure, and temperature, making it ideal for simulating biomolecules under physiological conditions where both temperature and pressure are controlled. While not explicitly detailed in the search results, this ensemble is widely used in MD simulations for studying proteins in their native environments. Additionally, reaction ensembles allow particle number fluctuations according to specific chemical reaction stoichiometries [34], providing a framework for simulating chemical transformations.

In principle, these ensembles should produce identical observables in the thermodynamic limit due to Legendre transforms, though deviations can occur under conditions where state variables are non-convex, such as in small molecular systems [34]. This theoretical equivalence provides a foundation for selecting the most computationally efficient ensemble for a given research question while maintaining physical accuracy.

Ensemble Selection Framework for Biomolecular Simulations

Mapping Research Objectives to Ensemble Choice