Resolving Levinthal's Paradox: How Molecular Dynamics and AI Are Decoding Protein Folding

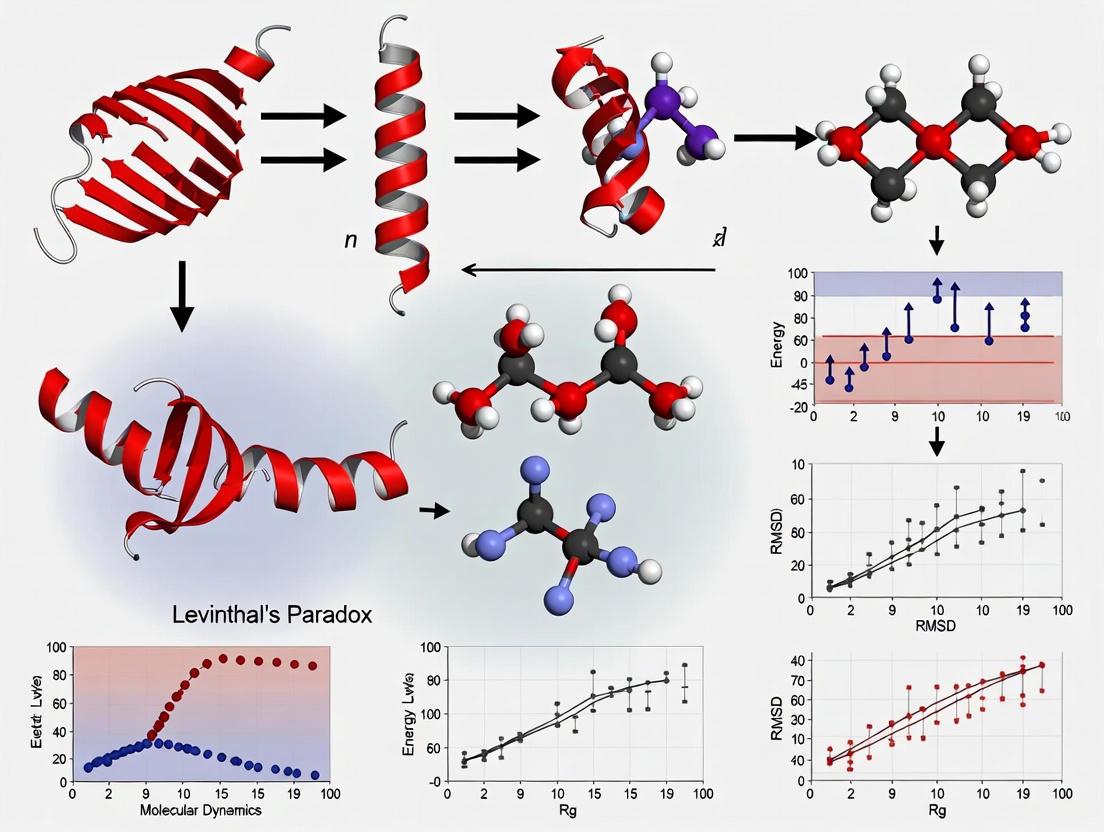

This article explores the resolution of Levinthal's paradox—the apparent contradiction between the astronomical number of possible protein conformations and their rapid, reliable folding.

Resolving Levinthal's Paradox: How Molecular Dynamics and AI Are Decoding Protein Folding

Abstract

This article explores the resolution of Levinthal's paradox—the apparent contradiction between the astronomical number of possible protein conformations and their rapid, reliable folding. It details how molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, energy landscape theory, and machine learning (ML) have transformed our understanding, moving from a random search model to a guided, funneled process. For researchers and drug development professionals, we examine the methodologies of modern protein structure prediction, address the limitations and optimization of computational tools like MD and AlphaFold, and discuss the critical validation of these models against experimental data. The synthesis of these approaches is paving the way for advanced applications in drug discovery and the design of novel therapeutics.

Deconstructing Levinthal's Paradox: From a Random Search to a Guided Folding Pathway

The protein folding problem, which encompasses the dual challenges of predicting a protein's native structure from its amino acid sequence and understanding the mechanism by which it folds, represents a grand challenge in molecular biology. The process, whereby a disordered polypeptide chain spontaneously collapses into a unique, functional three-dimensional structure, is remarkably efficient, often occurring on timescales of microseconds to milliseconds. This efficiency stands in stark contrast to Levinthal's paradox, which highlights the astronomical number of possible conformations available to an unfolded chain, making a random, exhaustive search implausible within any biologically relevant timeframe. This whitepaper examines the resolution of this paradox through the lens of energy landscape theory, which posits that folding is guided by a funnel-shaped energy landscape that efficiently directs the polypeptide toward its native state. We detail the experimental and computational methodologies that have been instrumental in probing early folding events and quantifying folding stability, and we discuss the critical implications of protein dynamics and allosteric regulation for therapeutic development.

Proteins are fundamental biological polymers that must fold into a specific three-dimensional conformation to perform their vast array of cellular functions. The "thermodynamic hypothesis", pioneered by Christian Anfinsen, established that the native structure of a protein resides in the global minimum of its Gibbs free energy under physiological conditions [1]. This implies that the amino acid sequence alone encodes the information necessary to dictate the final, functional structure.

However, this thermodynamic principle initially appeared to conflict with kinetic reality. In 1969, Cyrus Levinthal noted that an unfolded polypeptide chain possesses an astronomical number of possible conformations. For a typical protein of 100 residues, if each residue can adopt even a modest number of conformations, the total conformational space can exceed 10³â°â° possibilities [2]. If the protein were to randomly sample these conformations at picosecond rates, the time required to find the native state would exceed the age of the universe [3]. This is Levinthal's paradox: the stark contradiction between the vastness of conformational space and the observed rapidity of protein folding, which occurs in microseconds to seconds [2] [3].

The solution to this paradox lies in the understanding that protein folding is not a random search but a directed process. Proteins do not sample conformations indiscriminately; instead, the folding process is guided by an uneven, funnel-like energy landscape that biases the search toward the native state [2] [4]. This review will explore the theoretical frameworks, experimental methodologies, and computational advances that have collectively resolved this core paradox and deepened our understanding of protein dynamics.

Theoretical Frameworks: Resolving the Paradox

The Energy Landscape and Folding Funnel

The energy landscape theory provides a powerful conceptual framework for understanding how proteins fold rapidly. Instead of a flat landscape with a single deep minimum, the folding landscape is envisioned as a funnel [4]. At the top of the funnel, the unfolded chain has high energy and high conformational entropy. As the chain collapses into more compact, native-like structures, it loses entropy but gains stabilizing interactions, descending toward the low-energy native state at the bottom of the funnel [3].

The ruggedness of this funnel accounts for the presence of metastable intermediates and kinetic traps. A sufficiently smooth funnel allows the protein to find its native state quickly without becoming trapped in non-productive intermediates, explaining the observed fast folding times for many proteins [3].

Historical Folding Models

Several mechanistic models have been proposed to describe the protein folding pathway, each contributing to the resolution of Levinthal's paradox. The table below summarizes these key models.

Table 1: Key Theoretical Models in Protein Folding

| Model | Proposed Mechanism | Contribution to Paradox Resolution |

|---|---|---|

| Framework / Diffusion-Collision [1] [4] | Local secondary structures (α-helices, β-sheets) form independently before assembling into tertiary structure. | Suggests folding is modular, reducing the conformational search space. |

| Nucleation-Condensation [1] [4] | A weak, native-like nucleus forms through a combination of local and long-range interactions, leading to cooperative folding of the entire structure. | Explains how proteins can fold in a concerted manner without fully formed secondary structures. |

| Hydrophobic Collapse [1] | A rapid initial collapse around hydrophobic residues forms a compact "molten globule" state, narrowing the conformational search. | Highlights the role of solvent interactions in rapidly reducing the ensemble of chains to be searched. |

| Foldon Model [4] | Proteins fold in a modular, hierarchical manner via independently folding units ("foldons"). | Proposes a stepwise assembly process, further partitioning the folding task. |

These models are not mutually exclusive; the energy landscape theory incorporates elements of each, with the dominant pathway depending on the specific protein's sequence and topology [1].

Quantitative Dimensions of the Paradox

To fully appreciate Levinthal's paradox, it is essential to consider the quantitative scales involved in protein folding. The following table contrasts the theoretical challenge with the observed biological reality.

Table 2: The Quantitative Scale of Levinthal's Paradox

| Parameter | Theoretical Challenge (Random Search) | Biological Reality (Guided Search) |

|---|---|---|

| Conformational Space | ~10³â°â° possibilities for a 100-residue protein [2] [3] | Guided search of a vastly smaller subset of conformations |

| Time per Conformation | Picoseconds (the timescale of bond vibration) [3] | - |

| Theoretical Folding Time | >10¹Ⱐyears (longer than the age of the universe) [3] | Microseconds to minutes [3] [5] |

| Observed Folding Rate | - | Ranges from <1 μs to many seconds per residue [3] |

| Governance | - | Thermodynamic control with akinetic pathway [3] |

Experimental Methodologies for Probing Folding

Understanding fast folding events requires experimental techniques with high temporal and structural resolution. The following diagram illustrates a workflow integrating several key methods discussed in this section.

Rapid Perturbation Techniques

A critical requirement for studying folding is the ability to initiate the process synchronously on a timescale faster than the events of interest.

- Rapid Mixing: Techniques like stopped-flow and continuous-flow mixing achieve rapid changes in solvent conditions (e.g., denaturant concentration) to trigger folding. Continuous-flow methods, in particular, can access the submillisecond timescale, allowing observation of very early folding events [5].

- Temperature Jump (T-Jump): This method uses a fast laser pulse to rapidly increase the temperature of the solution, perturbing the folding equilibrium. Conventional T-jump systems can access the microsecond regime [5].

- Pressure Jump (P-Jump): Advanced apparatus using piezoelectric crystals can generate pressure jumps of up to 200 bar in as little as 50 microseconds, perturbing conformational equilibria and allowing the study of relaxation kinetics [5].

- Photochemical Triggers: These approaches use light to initiate folding, for example, by photolyzing a ligand (e.g., CO from cytochrome c) that stabilizes the unfolded state, triggering refolding on a nanosecond timescale [5].

High-Throughput Stability Measurements

Recent advances have enabled the large-scale measurement of protein folding stability, providing vast datasets for understanding sequence-stability relationships.

- cDNA Display Proteolysis: This is a powerful high-throughput method that can measure the thermodynamic folding stability (ΔG) for up to 900,000 protein variants in a single experiment [6]. The method involves:

- Creating a DNA library encoding the protein variants.

- Using cell-free translation to generate proteins covalently linked to their cDNA.

- Incubating the protein-cDNA complexes with a protease (e.g., trypsin or chymotrypsin).

- Quantifying protease-resistant (folded) proteins via deep sequencing of the surviving cDNA.

- Inferring folding stability (ΔG) using a kinetic model that accounts for cleavage rates in the folded and unfolded states [6].

This method is fast, accurate, and uniquely scalable, allowing for the comprehensive analysis of all single-point mutants in hundreds of protein domains [6].

Key Reagents and Research Tools

The following table details essential reagents and their functions in protein folding research.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Protein Folding Studies

| Reagent / Tool | Function in Folding Research |

|---|---|

| Synth. DNA Oligo Pools [6] | Encodes large libraries of protein variants for high-throughput stability assays. |

| Cell-free cDNA Display [6] | Links a protein to its encoding cDNA, enabling in vitro selection and sequencing-based quantification. |

| Proteases (Trypsin/Chymotrypsin) [6] | Probes folding stability; folded proteins are resistant to cleavage. |

| Fluorescent Dyes/Reporters [5] | Act as sensitive probes for conformational changes during folding (e.g., FRET pairs). |

| Isotopically Labeled Proteins [5] | Enables detailed structural and dynamic studies using NMR spectroscopy. |

Computational Approaches and Molecular Dynamics

Computational methods have been indispensable in resolving Levinthal's paradox and simulating the folding process.

- Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations: MD simulations model the physical movements of every atom in a protein and its solvent over time. While all-atom simulations of folding were once impossible, advances in hardware and software have made it feasible to simulate the folding of small proteins [1]. These simulations have shown that model chains can fold rapidly to their global free energy minimum, confirming thermodynamic control and demonstrating the existence of natural, rapid folding pathways [3].

- Machine Learning for Folding Rates: Machine learning algorithms are being applied to predict protein folding rates. For instance, support vector machines (SVM) and other regressors can predict logarithmic folding rates (ln(kf)) using structural parameters and network centrality measures, providing insights into the factors that determine folding speed [7].

- Elastic Network Models (ENM): These coarse-grained models represent proteins as networks of connected springs. They are highly efficient for studying large-scale collective motions and allosteric regulation, bridging the gap between static structure and dynamic function [8].

Implications for Allostery and Drug Design

The principles of protein dynamics and folding extend directly into the regulation of protein function and therapeutic intervention.

- Dynamic Allostery: Allostery is a fundamental mechanism of biological regulation where an event at one site (e.g., ligand binding) influences a distant functional site. Beyond classical models that involve major conformational changes, dynamic allostery allows for functional modulation through changes in protein dynamics and thermal fluctuations without large-scale structural shifts [9]. Evolution leverages this mechanism to fine-tune protein function through distal mutations [9].

- Therapeutic Targeting: Understanding allosteric networks and protein dynamics opens new avenues for drug discovery. Allosteric modulators can offer greater specificity than orthosteric drugs. Computational tools like MD simulations, elastic network models, and protein structure networks are critical for identifying allosteric sites and understanding how disease-associated mutations perturb allosteric communication, as seen in targets like beta-lactamases and kinases [10] [8].

Levinthal's paradox has been resolved not by discovering a single "folding pathway" but by a fundamental shift in perspective. The process is best understood as a navigation down a funneled energy landscape, where native-like interactions act as guides, making the search for the native state efficient and rapid. This understanding has been driven by the synergistic development of sophisticated experimental techniques, powerful computational simulations, and novel theoretical frameworks. The resulting insights into protein dynamics not only solve a fundamental biophysical puzzle but also provide a critical foundation for manipulating protein function in fields like biotechnology and drug design, where targeting allosteric networks and protein stability holds immense promise.

Anfinsen's Dogma and the Thermodynamic Hypothesis of the Native State

Anfinsen's Dogma, articulated by Christian B. Anfinsen in the 1960s, constitutes a foundational principle in molecular biology, positing that a protein's native three-dimensional structure is uniquely determined by its amino acid sequence under physiological conditions, representing the thermodynamically most stable state [11]. This postulate, often termed the thermodynamic hypothesis, earned Anfinsen the 1972 Nobel Prize in Chemistry and established the conceptual framework for understanding protein folding as a spontaneous self-assembly process. While this principle has guided decades of research, contemporary molecular dynamics investigations and the persistent challenge of Levinthal's paradox have revealed both the enduring validity and limitations of Anfinsen's original hypothesis. This whitepaper examines the core tenets of Anfinsen's Dogma within the context of modern protein folding research, exploring how computational approaches, particularly molecular dynamics simulations, have refined our understanding of the pathway from sequence to functional structure, and its critical implications for therapeutic development in protein misfolding diseases.

The process by which a linear polypeptide chain folds into a specific, functional three-dimensional structure represents one of the most fundamental phenomena in structural biology. Anfinsen's seminal experiments with ribonuclease A demonstrated that the protein could spontaneously refold into its native, catalytically active conformation after complete denaturation, leading to the revolutionary conclusion that all information necessary to specify the tertiary structure resides in the primary amino acid sequence [11]. This principle, termed Anfinsen's Dogma or the thermodynamic hypothesis, proposes that the native fold corresponds to the global minimum of the Gibbs free energy under physiological conditions [12].

The dogma rests upon three essential conditions that must be satisfied for a unique native structure to exist. First, the structure must be unique, meaning the amino acid sequence must not possess any alternative conformation with a comparable free energy; the global free energy minimum must be unchallenged. Second, the native state must demonstrate stability, requiring that minor perturbations to the environmental conditions do not produce substantial changes in the minimum energy configuration. This can be visualized as a free energy landscape resembling a steep funnel rather than a shallow soup plate. Third, the folded state must be kinetically accessible, implying that the pathway from the unfolded to the native state must be reasonably smooth and not involve excessively complex topological rearrangements such as knotting or other high-order conformational changes [11] [13].

The Experimental Foundation of Anfinsen's Dogma

Original Experimental Methodology

Anfinsen's foundational conclusions were derived from a series of rigorous experiments on bovine pancreatic ribonuclease A, an enzyme that catalyzes RNA hydrolysis. The key experimental protocol involved:

- Reductive Denaturation: Ribonuclease A was treated with β-mercaptoethanol to reduce its four disulfide bridges, along with 8M urea to disrupt non-covalent interactions. This treatment completely unfolded the protein and abolished its enzymatic activity [11].

- Oxidative Renaturation: The denaturing agents were subsequently removed through dialysis. Upon exposure to atmospheric oxygen, the reduced protein spontaneously reoxidized and refolded.

- Recovery Assessment: The renatured protein regained its full enzymatic activity and its original physicochemical properties, including antigenicity and protease susceptibility. Critically, the reformation of the four correct disulfide pairings occurred despite 105 possible combinations, indicating the process was not random but directed by the amino acid sequence [11] [12].

This experimental demonstration that no additional genetic information or cellular machinery was required for folding provided compelling evidence for the thermodynamic hypothesis.

Quantitative Evidence Supporting the Native State

Table 1: Key Experimental Evidence Supporting Anfinsen's Dogma

| Experimental Evidence | Description | Quantitative Outcome | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ribonuclease A Refolding | Spontaneous refolding after reductive denaturation and reoxidation [11] | ~100% recovery of enzymatic activity | Native structure is thermodynamically favored |

| Disulfide Bond Formation | Reformation of four specific disulfide bridges from 105 possibilities [11] | Correct pairings formed with >95% fidelity | Sequence dictates specific stabilizing interactions |

| In Silico Structure Prediction | Computational methods like ROSETTA achieving atomic-level accuracy for small proteins [12] | Structures predicted for 17 proteins up to 100 residues | Sequence alone sufficient to determine structure |

Levinthal's Paradox and the Kinetic Accessibility Challenge

While Anfinsen's Dogma established the thermodynamic determinism of protein folding, it was Cyrus Levinthal who in 1969 highlighted the profound kinetic paradox inherent in the process. Levinthal observed that an unfolded polypeptide chain possesses an astronomical number of possible conformations. For a typical protein of 100 residues, considering just three possible conformations per residue yields approximately 3¹â°â° (or ~10â´â¸) possible structures [14].

If the protein were to randomly sample these conformations at nanosecond rates, the time required to find the native structure would exceed the age of the universe. This stands in stark contrast to the observed reality that most proteins fold on timescales of milliseconds to seconds [14]. Levinthal himself proposed the resolution to this paradox: proteins do not fold by exhaustive random search but through "speedy and guided" formation of local interactions that serve as nucleation points for subsequent folding steps—essentially, folding follows directed pathways [14].

The conceptual framework that reconciles Anfinsen's thermodynamic perspective with Levinthal's kinetic insight is the energy landscape theory. Instead of a flat landscape with countless local minima, the folding landscape is envisioned as a funnel, where the breadth represents conformational entropy and the depth represents energy. The native state resides at the bottom of this funnel, and the folding process involves a progressive narrowing of conformational space as the protein approaches its minimum energy state [4]. This funneled landscape allows proteins to fold rapidly through biased stochastic processes rather than random search.

Diagram 1: Protein Folding Energy Landscape. The funnel visualization illustrates how a protein progresses from an unfolded state (high entropy, top) to the native state (global free energy minimum, bottom). Colored pathways show successful folding via nucleation (red) and kinetic trapping in misfolded states requiring backtracking (green).

Challenges and Exceptions to Anfinsen's Dogma

While Anfinsen's Dogma provides a powerful foundational framework, contemporary research has revealed several significant exceptions and complexities that challenge its absolute validity, particularly in the complex cellular environment.

Molecular Chaperones and Cellular Folding

The discovery of molecular chaperones—proteins that assist in the folding of other proteins—appeared initially to contradict Anfinsen's sequence-sufficient premise. However, current understanding suggests that chaperones primarily prevent off-pathway interactions such as aggregation rather than providing specific structural information [11] [4]. They act as "foldases" that mitigate the challenges of folding in crowded cellular environments but do not fundamentally alter the final folded state determined by the sequence [11].

Protein Misfolding and Aggregation Diseases

A more significant challenge arises from the phenomenon of protein misfolding associated with numerous human diseases. Conditions including Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease, and prion disorders like bovine spongiform encephalopathy involve proteins adopting stable, non-native conformations that evade cellular quality control mechanisms [11] [4]. Prion proteins, for instance, adopt stable conformations that differ from the native fold and can catalyze the conversion of other molecules to the same misfolded state, leading to pathogenic amyloid accumulation [11].

Non-Native Entanglement Misfolding

Recent molecular dynamics simulations have identified a specific class of misfolding involving "non-native entanglement" where proteins become kinetically trapped in off-pathway states. This occurs when:

- A gain of non-native entanglement forms: a loop structure traps another protein segment that shouldn't be threaded.

- A loss of native entanglement occurs: a necessary threading fails to form [15] [16].

These misfolded states are particularly problematic as they are often stable, soluble, and structurally similar to the native state, allowing them to evade cellular quality control systems [16]. All-atom simulations confirm that such entangled states can persist for biologically relevant timescales, especially in larger proteins where backtracking to correct the misfolding becomes energetically costly [15].

Fold-Switching Proteins

Approximately 0.5-4% of proteins in the Protein Data Bank are now recognized as "fold-switching" proteins capable of adopting multiple distinct native-like folds [11]. Examples include the KaiB protein in cyanobacteria, which switches its fold throughout the day as part of a circadian clock mechanism [11]. Such proteins exist in alternative stable states that may represent either different free energy minima or kinetically trapped conformations, with transitions driven by environmental conditions, ligand binding, or post-translational modifications.

Molecular Dynamics Simulations in Protein Folding Research

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations have emerged as a transformative tool for investigating protein folding, enabling researchers to observe folding pathways and test hypotheses at atomic resolution and timescales previously inaccessible to experimental observation.

Simulation Methodologies

Table 2: Molecular Dynamics Approaches in Protein Folding Research

| Simulation Type | Resolution Level | Key Features | Applications & Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| All-Atom MD | Atomic-level detail [15] | Models every atom; Newtonian equations of motion; high computational cost [12] | High-resolution folding pathways; limited to smaller proteins or shorter timescales |

| Coarse-Grained MD | Amino acid residue level [16] | Groups of atoms represented as single interaction sites; reduced complexity [12] | Study of larger proteins and longer timescales; loss of atomic detail |

| Structure-Based Models | Tertiary structural contacts [16] | Energy function biased toward native contacts; "funneled" landscape [16] | Investigation of folding mechanisms; limited for misfolding studies |

Key Insights from Simulation Studies

Advanced MD simulations have provided critical insights into protein folding mechanisms:

- Folding Pathways: All-atom MD simulations have successfully tracked complete folding processes for small proteins like ubiquitin, revealing folding timescales and intermediate states that align with experimental data [16].

- Misfolding Mechanisms: As discussed previously, MD simulations have identified and characterized non-native entanglement misfolding, demonstrating how these kinetic traps form and persist [15] [16].

- Thermodynamic Validation: Free energy calculations from simulations support the thermodynamic hypothesis by showing that the native state typically corresponds to the global free energy minimum under physiological conditions [12].

The combination of simulation and experimental techniques such as hydrogen-deuterium exchange mass spectrometry (HDX-MS) and limited proteolysis has enabled the validation of predicted misfolded states and provided insights into their structural characteristics [16].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Methods

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Methods for Protein Folding Studies

| Reagent/Method | Function/Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Chaperones (e.g., GroEL/GroES) | Prevent aggregation and facilitate proper folding in cellular environments [4] | Essential for studying folding in vivo; not required for final structure determination |

| Denaturants (Urea, GdnHCl) | Unfold proteins for refolding studies; determine folding stability [11] | Used in Anfinsen's original experiments; concentration-dependent effects |

| Hydrogen-Deuterium Exchange Mass Spectrometry (HDX-MS) | Probes protein structure and dynamics by measuring hydrogen exchange rates [4] | Identifies structured regions and folding intermediates; used with simulation data |

| Molecular Dynamics Software (GROMACS, AMBER, CHARMM) | Simulates protein folding pathways and dynamics [15] [12] | All-atom and coarse-grained approaches available; requires substantial computing resources |

| Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectroscopy | Determines protein structure and dynamics in solution [4] | Can monitor folding processes in real-time; technical complexity |

| Rosetta@home & AlphaFold | Predict protein structures from amino acid sequences [12] | Leverages distributed computing or neural networks; revolutionary accuracy |

| 2-Nitropyridin-4-ol | 2-Nitropyridin-4-ol|CAS 101654-28-8|High Purity | Get high-purity 2-Nitropyridin-4-ol (CAS 101654-28-8) for your research. This nitropyridine derivative is a key building block in organic synthesis. For Research Use Only. |

| 1-benzyl-3,5-dibromo-1H-1,2,4-triazole | 1-benzyl-3,5-dibromo-1H-1,2,4-triazole, CAS:106724-85-0, MF:C9H7Br2N3, MW:316.98 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Anfinsen's Dogma remains a cornerstone principle in structural biology, correctly asserting that a protein's amino acid sequence encodes the necessary information to specify its three-dimensional structure under physiological conditions. However, seven decades of research, powered by advanced molecular dynamics simulations and experimental techniques, have revealed a more nuanced reality. The folding process occurs not through random conformational search but through guided pathways across funneled energy landscapes, with kinetic traps, chaperone assistance, and even alternative native states complicating the direct sequence-to-structure paradigm.

For researchers and drug development professionals, these insights are critically important. Understanding the mechanisms of protein misfolding, particularly long-lived kinetically trapped states, opens new therapeutic avenues for diseases ranging from neurodegeneration to aging-related disorders. Molecular dynamics simulations continue to enhance our predictive capabilities, bridging the gap between sequence and structure while illuminating the complex folding journey that Anfinsen's foundational work first revealed.

Diagram 2: Cellular Protein Folding Pathway. This workflow illustrates the journey from amino acid sequence to functional native state, highlighting the role of chaperones, cellular environment, and potential off-pathway misfolding that can lead to aggregation or degradation.

The Energy Landscape and Folding Funnel Theory as a Solution

The protein folding problem represents one of the most fundamental challenges in molecular biology. In 1969, Cyrus Levinthal posed his famous paradox, highlighting the stark contradiction between the vast conformational space available to an unfolded polypeptide chain and the rapid, reproducible folding observed in biological systems [17] [4]. Levinthal noted that a random, sequential search of all possible conformations would require timescales vastly exceeding the age of the universe, yet proteins typically fold on timescales of milliseconds to seconds [18]. This paradox created a conceptual impasse that persisted for decades.

The resolution to this paradox emerged not from a pathway-centric view, but from a radical shift in perspective: the energy landscape theory and its central metaphor, the folding funnel [18]. First introduced by Ken A. Dill in the 1980s, this theory reframes protein folding not as a random search, but as a guided, energetically biased process where a protein progressively navigates towards its native state through a funnel-shaped energy landscape [18]. This review explores how the folding funnel theory provides a comprehensive solution to Levinthal's paradox, its experimental and computational validation, and its critical implications for molecular dynamics research and drug development.

Theoretical Foundations of the Folding Funnel

Core Principles of the Energy Landscape

The folding funnel hypothesis is a specific version of the energy landscape theory that visualizes the protein folding process as a progressive narrowing of conformational possibilities toward the native state. The key to resolving Levinthal's paradox lies in understanding that folding is not a random search but a directed, multi-pathway process governed by the topology of this energy landscape [18].

The landscape is characterized by two fundamental dimensions: depth, representing the energetic stabilization of the native state, and width, representing the conformational entropy of the system [18]. As the protein folds, it loses conformational entropy (moving down the funnel) while gaining favorable native contacts (decreasing in energy). The theory posits that the native state corresponds to the global free energy minimum under physiological conditions, consistent with Christian Anfinsen's thermodynamic hypothesis [18] [4].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Protein Energy Landscapes

| Characteristic | Description | Implication for Folding |

|---|---|---|

| Funnel Shape | Wide at the top (unfolded states), narrow at the bottom (native state) | Directs the search toward the native state |

| Landscape Ruggedness | Presence of hills, valleys, and local minima | Can create kinetic traps for partially folded intermediates |

| Thermodynamic Stability | Native state occupies the global free energy minimum | Ensures the native state is thermodynamically favored |

| Multi-Dimensionality | Landscape defined by many conformational coordinates | Allows for multiple parallel folding pathways |

Resolving Levinthal's Paradox

The funnel landscape resolves Levinthal's paradox through several key mechanisms:

- Non-Random Search: The search is not random but is biased toward the native state by energetically favorable interactions, particularly the hydrophobic effect [18]. The sequestration of hydrophobic residues away from water provides a major driving force, in a process known as hydrophobic collapse.

- Parallel Pathways: The funnel accommodates numerous parallel folding routes, meaning different molecules of the same protein can follow microscopically different pathways to reach the same native structure [18]. This massively parallel search drastically reduces the effective folding time.

- Progressive Organization: Folding proceeds through the progressive organization of an ensemble of partially folded structures, rather than a single pathway with mandatory intermediates [18]. This is described as a "divide-and-conquer" strategy, where local structures form first, followed by global assembly [18].

Quantitative Models and Landscape Topographies

Theoretical models have proposed specific topographies for the folding funnel, each with distinct implications for folding kinetics and mechanisms.

Classical Funnel Models

Dill and Chan illustrated several landscape models that depict possible folding routes [18]:

- The "Golf-Course" Landscape: A hypothetically flat landscape where a random search would be impossible, highlighting the necessity of a biased, funneled landscape.

- The Ideal Smooth Funnel: A landscape with minimal energetic barriers, allowing rapid, direct descent to the native state.

- The Rugged Funnel: Contains many local minima and barriers, representing kinetic traps where partially folded structures can become transiently stuck.

- The "Moat" Landscape: Features an obligatory kinetic trap that a significant population of molecules must navigate through.

- The "Champagne Glass" Landscape: Characterized by a significant free energy barrier, often related to conformational entropy, that must be overcome before rapid folding can proceed.

The Foldon Volcano Model

A significant variation, the Foldon Funnel Model proposed by Rollins and Dill, suggests the energy landscape has a volcano shape rather than a simple funnel [18]. In this model, the initial formation of native-like secondary structures is energetically unfavorable (uphill in free energy) and is only stabilized by subsequent tertiary interactions. The highest free energy point is the step just before reaching the native state, consistent with experimental observations that isolated secondary structures are often unstable [18].

Experimental Validation and Probes

The predictions of the energy landscape theory have been tested and supported by a range of sophisticated experimental techniques.

Single-Molecule Force Spectroscopy

Single-molecule techniques, particularly magnetic tweezers, have emerged as powerful tools for directly probing protein folding dynamics under force. In magnetic tweezers, a single protein is tethered between a glass surface and a magnetic bead. Application of a magnetic field exerts a piconewton-scale force to stretch the protein, while its extension is tracked with nanometer precision [19]. This method provides intrinsic force-clamp conditions and exceptional stability, enabling long-term measurement of equilibrium folding and unfolding transitions for individual molecules, free from ensemble averaging [19]. Other key techniques include atomic force microscopy (AFM) and optical tweezers.

Hydrogen-Deuterium Exchange (HDX)

HDX coupled with mass spectrometry or NMR can probe the structure and dynamics of folding intermediates by measuring the rate at which backbone amide hydrogens exchange with deuterium from the solvent. This technique provided key evidence for the foldon model, revealing that proteins can fold in a modular, hierarchical manner with discrete units (foldons) attaining native-like structure at different stages [4].

Table 2: Key Experimental Methods for Probing Energy Landscapes

| Method | Key Measurable | Application to Landscape Theory |

|---|---|---|

| Single-Molecule Magnetic Tweezers | End-to-end extension changes under constant force; folding/unfolding rates | Directly measures dynamics and stability under mechanical perturbation; maps free energy landscapes [19] |

| Hydrogen-Deuterium Exchange (HDX) | Solvent accessibility of backbone amides; protection factors | Identifies structured regions in intermediates; validates hierarchical folding (e.g., Foldons) [4] |

| Single-Molecule FRET (smFRET) | Distance between two fluorophores on a protein | Probes conformational heterogeneity and dynamics of ensembles in real-time |

| NMR Spectroscopy | Chemical shifts, relaxation rates | Provides atomic-resolution data on protein dynamics and transiently populated states |

Diagram 1: The Folding Funnel Concept. The funnel visualizes the progressive decrease in conformational entropy and energy as a protein transitions from an unfolded state to its native structure.

Computational Approaches and Molecular Dynamics

Computer simulations, particularly molecular dynamics (MD), have been instrumental in visualizing and quantifying the folding process in atomic detail, providing a critical link between theory and experiment.

All-Atom Molecular Dynamics Simulations

All-atom MD simulations explicitly model every atom in a protein and its solvent environment, integrating Newton's equations of motion to trace atomic trajectories [20]. The careful preparation of the initial system—including solvation, energy minimization, and thermalization—is vital to avoid fictitious behavior and ensure biological relevance [20]. While tremendously powerful, a significant limitation is the timescale barrier; folding events often occur on timescales (milliseconds to seconds) that are computationally prohibitive to simulate with standard MD.

Enhanced Sampling and Free Energy Methods

To overcome timescale limitations, advanced computational techniques have been developed:

- Essential Dynamics Sampling (EDS): This technique biases a simulation to explore configurations along collective motions derived from an analysis of the protein's natural dynamics, allowing efficient sampling of the folding pathway [21].

- Free Energy Perturbation (FEP): FEP is a physics-based method used to calculate the free energy differences between two states, such as a wild-type protein and a mutant. Modern protocols like QresFEP-2 use a hybrid-topology approach to efficiently and accurately predict the effects of point mutations on protein stability, which is crucial for drug design and understanding disease [22].

Diagram 2: MD Simulation Workflow. A generic protocol for all-atom molecular dynamics simulations of protein folding/unfolding in solution.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Protein Folding Studies

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Dynamics Software | All-atom simulation of folding pathways and dynamics | GROMACS [22], ENCAD [20], AMBER, CHARMM |

| Free Energy Perturbation (FEP) Protocols | Predict mutational effects on stability & binding | QresFEP-2 (hybrid-topology) [22], FEP+ (dual-topology) |

| Superparamagnetic Beads | Force probe for magnetic tweezers experiments | ~1-5 µm beads, tethered via engineered cysteines [19] |

| Fluorescent Dyes | Labeling for smFRET and fluorescence spectroscopy | Cy3/Cy5, Alexa Fluor dyes for distance measurements |

| Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kits | Engineer protein variants to test stability | Alanine scanning, Foldon disruption, disease mutation models |

| AI-Based Structure Prediction | Generate structural hypotheses and models | AlphaFold2, SimpleFold (general-purpose transformer) [23] |

Implications for Drug Discovery and Human Health

The energy landscape perspective has profound implications beyond basic science, particularly in understanding disease and guiding therapeutic development.

Many human diseases, including neurodegenerative disorders like Alzheimer's and Parkinson's, are linked to protein misfolding and aggregation [4]. A rugged energy landscape with deep kinetic traps can favor the population of misfolded states that self-assemble into toxic aggregates. The cellular proteostasis network—a system of chaperones, folding enzymes, and degradation machinery—functions to maintain a smooth, functional landscape [4]. Age-related decline in proteostasis capacity can lead to a failure to manage this landscape, resulting in disease.

In drug discovery, the concept of conformational selection derived from landscape theory is fundamental. Rather than inducing a single conformational change, drugs often bind to and stabilize pre-existing, low-population conformations within the native-state ensemble, shifting the equilibrium [24]. This shifts the energy landscape itself, stabilizing active or inactive states, which is a key mechanism for allosteric drugs and for designing inhibitors that target specific conformational states.

The energy landscape and folding funnel theory has successfully provided a unified framework to resolve Levinthal's paradox. It demonstrates that proteins fold rapidly not by examining all possible conformations, but by navigating a funneled energy landscape that biases the search toward the native state through a combination of energetically favorable interactions and ensemble-based parallel pathways.

Future research will focus on exploring the most rugged parts of the landscape, understanding the folding of large multi-domain proteins and complexes, and further integrating computational predictions with experimental validation. The continued development of advanced MD protocols like QresFEP-2 [22] and novel AI-based structure prediction tools like SimpleFold [23] will further bridge the gap between predicting structure and understanding the dynamical folding process. The application of these principles will continue to illuminate the mechanisms of biological function and disease, and accelerate the rational design of therapeutics.

The protein folding problem has been predominantly studied in simplified, optimized in vitro conditions, yielding fundamental physicochemical principles of folding landscapes. However, a significant gap persists between this foundational knowledge and the complex reality of folding within the living cell. This whitepaper delineates the critical distinctions between in vitro and in vivo protein folding environments, emphasizing the role of macromolecular crowding, vectorial synthesis, chaperone assistance, and evolutionary pressures. By framing these differences within the context of Levinthal's paradox and advances in molecular dynamics research, we provide a technical guide for researchers and drug development professionals to bridge the conceptual and experimental divides, fostering a more predictive understanding of protein behavior in biological and therapeutic contexts.

The classic in vitro experiments of Christian Anfinsen demonstrated that a protein's amino acid sequence contains all the information necessary to specify its three-dimensional native structure [25]. This principle has guided decades of research, yielding profound insights into protein folding kinetics and thermodynamics under controlled, dilute buffer conditions. However, the cellular environment presents a fundamentally different set of challenges and influences that distinguish the in vivo folding process from its in vitro counterpart.

Levinthal's paradox highlights the core theoretical problem: a random, brute-force search of all possible conformations would take an astronomical amount of time, far longer than the age of the universe, for a protein to find its native state [14]. Yet, proteins fold spontaneously on millisecond to second timescales. The resolution to this paradox lies in the concept of funneled energy landscapes, where proteins do not sample conformations randomly but are guided toward the native state by biased interactions [14]. While this theory explains rapid folding in vitro, the in vivo environment introduces additional layers of complexity that further reshape this energy landscape. The cell is not a dilute aqueous solution; it is an extremely crowded, organized, and active environment where folding occurs concurrently with synthesis, alongside myriad interactions that can either facilitate or hinder the journey to the functional native structure.

Fundamental Environmental Differences: A Comparative Analysis

The environment in which a protein folds profoundly influences its pathway, kinetics, and success rate. The following table summarizes the key differentiating factors between the test tube and the cellular milieu.

Table 1: Key Differences Between In Vitro and In Vivo Folding Environments

| Factor | In Vitro Folding | In Vivo Folding |

|---|---|---|

| Initiation | Refolding of full-length, denatured polypeptide chains [26] | Co-translational folding during ribosomal synthesis; vectorial folding during secretion [26] [25] |

| Macromolecular Crowding | Absent or minimal (highly dilute solutions) [26] | Extremely high (200–400 mg/mL total macromolecule concentration) [26] |

| Chaperone Assistance | Typically absent unless specifically added | Essential for a significant fraction of proteins; prevents aggregation and aids folding [26] |

| Spatial Organization | Homogeneous solution | Highly organized; compartmentalized (e.g., cytosol, endoplasmic reticulum, organelles) [26] |

| Unfolded State Population | Sampled freely in dynamic equilibrium governed by thermodynamic stability [26] | Disfavored due to chaperone binding, ongoing degradation, and kinetic barriers [26] |

| Competition with Aggregation | Governed by simple second-order kinetics; high concentration leads to aggregation [27] | Kinetic competition between folding, aggregation, and chaperone intervention; aggregation is a dangerous side reaction [26] [27] |

| Energy Landscape | Governed primarily by intrinsic protein sequence and solvent conditions | Reshaped by crowding, weak "quinary" interactions, and helper proteins [26] |

The Impact of the Cellular Milieu

The crowded cellular environment, with macromolecule concentrations ranging from 200 to 400 mg/ml, was initially thought to influence folding primarily through excluded volume effects, which favor more compact folded states. However, recent work suggests that the influence may be dominated by a high density of weak, transient, non-specific interactions, sometimes termed "quinary" interactions [26]. These interactions can either stabilize or destabilize native proteins and their intermediates, effectively reshaping the folding energy landscape in a manner difficult to replicate in the test tube.

Vectorial Folding: The Role of Synthesis and Secretion

A fundamental distinction is the vectorial nature of folding in vivo. In vitro refolding typically begins from an ensemble of full-length, denatured chains. In the cell, proteins are synthesized by the ribosome from the N to the C terminus, allowing the nascent chain to begin folding before synthesis is complete [26] [25]. This co-translational folding can prevent non-productive interactions that might occur if the entire chain were present simultaneously and can populate productive folding intermediates [25].

A striking example of vectorial folding is found in autotransporter proteins from Gram-negative bacteria. These virulence factors are secreted across the outer membrane from the C to the N terminus. This directional secretion, coupled with an anisotropic distribution of folding stability along the polypeptide chain, promotes rapid folding on the cell surface and may even provide a driving force for efficient secretion [25]. This stands in stark contrast to the refolding of a full-length autotransporter protein in vitro, which proceeds orders of magnitude more slowly [25].

Table 2: Experimental Techniques for Studying Folding Across Environments

| Technique | Application | Key Insights Provided |

|---|---|---|

| Single-Molecule FRET | In vitro & in vivo (via microscopy) | Measures intra-molecular distances, folding pathways, and metastable states in real-time [26] |

| Optical Tweezers | Primarily in vitro | Applies mechanical force to unfold/refold proteins, revealing transition paths and intermediate states [26] |

| Fluorescence Relaxation Imaging (FReI) | In vivo | Monitors protein folding and stability inside living cells using FRET and temperature or denaturant jumps [28] |

| NMR Spectroscopy | In vitro & in vivo | Provides atomic-resolution data on protein structure, dynamics, and populations of conformational states |

| Machine-Learned Coarse-Grained (CG) MD | In silico | Predicts folding pathways, metastable states, and effects of mutations at a fraction of the computational cost of all-atom MD [29] |

Resolving Levinthal's Paradox: From Theory to Cellular Reality

Levinthal's paradox posits that a random conformational search for the native state would take an impossibly long time, implying the existence of guided folding pathways [30] [14]. In vitro studies resolved this by introducing the concept of a funneled energy landscape, where native-like interactions are preferentially stabilized, leading the protein efficiently to its native state [14].

The in vivo environment introduces additional factors that further resolve this paradox. Co-translational folding reduces the conformational search space dramatically. By starting from a much smaller ensemble of conformations and building the protein incrementally, the cell avoids the Levinthal search problem for the entire chain at once [25]. Furthermore, molecular chaperones do not typically provide steric information for folding but instead suppress off-pathway reactions like aggregation, effectively smoothing the energy landscape and allowing the protein's intrinsic sequence-based preferences to guide it to the native state more reliably [26]. The crowded milieu, through a combination of excluded volume and quinary interactions, can also bias the landscape toward more compact, native-like states.

The following diagram illustrates how the cellular environment shapes the protein folding energy landscape compared to the in vitro scenario.

Advanced Computational and Experimental Methodologies

The Rise of Machine-Learned Molecular Dynamics

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation is a powerful tool for elucidating folding pathways. All-atom MD provides high resolution but at an extreme computational cost, limiting its application to small proteins and short timescales [29]. Recent breakthroughs involve the development of machine-learned coarse-grained (CG) models. These models are trained on diverse all-atom simulation datasets and can then be used for extrapolative MD on new protein sequences.

One such model, CGSchNet, demonstrates transferability across sequence space, successfully predicting metastable states of folded, unfolded, and intermediate structures for proteins not included in its training set [29]. This approach is several orders of magnitude faster than all-atom MD, making it feasible to simulate the folding of larger proteins like the 73-residue alpha3D and to compute relative folding free energies of mutants [29]. This represents a significant step toward a universal, predictive simulation tool that can bridge the gap between in vitro and in vivo folding by potentially incorporating cellular factors.

Quantitative Kinetic Models for In Vivo Folding

Understanding folding in the cell requires quantitative models that account for kinetic competition. A foundational model describes the competition between first-order folding and second-order aggregation during de novo protein synthesis [27]. The yield of native protein in vivo depends not only on the rates of folding and aggregation but also on the rate of protein synthesis itself. This framework explains why the cell has evolved mechanisms, such as molecular chaperones, to influence these rates and prevent unproductive aggregation [27].

The following diagram outlines a generalized experimental workflow for integrating in vitro and in vivo data to build predictive models of cellular folding, a approach relevant to both protein and RNA folding [31].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagent Solutions for Protein Folding Research

| Research Reagent / Tool | Function in Folding Studies |

|---|---|

| Chemical Denaturants (e.g., Urea, GdnHCl) | Unfold proteins in vitro to initiate refolding studies; used to measure protein stability [25]. |

| Fluorescent Dyes (for FRET) | Label proteins to act as donor/acceptor pairs in Förster Resonance Energy Transfer, reporting on intra-molecular distances and conformational changes [26] [28]. |

| Molecular Chaperones (e.g., Hsp70) | Purified chaperones are used in vitro to study their mechanism of action in preventing aggregation and facilitating folding [26] [28]. |

| Crowding Agents (e.g., Ficoll, Dextran) | Polymers used in vitro to mimic the excluded volume effects of the crowded cellular environment [26]. |

| Machine-Learned Coarse-Grained (CG) Force Fields | Computational models that dramatically increase simulation speed while maintaining accuracy for predicting folding pathways and free energies [29]. |

| Optical Tweezers | Instrument that uses laser light to manipulate beads attached to a protein, allowing the application of precise forces to study unfolding/refolding mechanics [26]. |

| 1-[4-(Trifluoromethyl)benzyl]piperazine | 1-[4-(Trifluoromethyl)benzyl]piperazine, CAS:107890-32-4, MF:C12H15F3N2, MW:244.26 g/mol |

| Methyl 2-amino-1H-benzo[d]imidazole-5-carboxylate | Methyl 2-amino-1H-benzo[d]imidazole-5-carboxylate, CAS:106429-38-3, MF:C9H9N3O2, MW:191.19 g/mol |

The distinction between in vitro and in vivo protein folding is not merely a technicality but a fundamental consideration for understanding biology and developing therapeutics. The cellular environment—with its crowding, spatial organization, helper proteins, and vectorial synthesis—actively participates in the folding process, reshaping energy landscapes and ensuring efficiency and fidelity. Levinthal's paradox, resolved in vitro by the concept of funneled landscapes, is further resolved in vivo by these additional biological factors that guide the search for the native state.

Future research must continue to bridge the gap between these two worlds. This will involve developing more sophisticated in vitro systems that better mimic cellular conditions, advancing in vivo measurement techniques with greater spatial and temporal resolution, and creating next-generation computational models that can integrate the multitude of factors present in the cell. As these fields converge, we move closer to a truly predictive understanding of protein folding, misfolding, and aggregation in human health and disease, ultimately enabling more rational drug design and therapeutic interventions.

Computational Arsenal: MD Simulations, AI, and Advanced Sampling for Protein Dynamics

The fundamental challenge in structural biology is understanding how a protein's one-dimensional amino acid sequence dictates its unique, functional three-dimensional structure. This process, known as protein folding, is central to all biological function and is famously encapsulated by Levinthal's paradox, which highlights the astronomical improbability of a protein randomly searching all possible conformations to find its native state [17] [4]. Despite this, proteins in nature fold reliably and rapidly, suggesting the existence of specific folding pathways guided by a funnel-shaped energy landscape [4]. Molecular Dynamics (MD) has emerged as a powerful computational technique that directly addresses this paradox by simulating the physical motions of atoms and molecules over time, effectively providing a "computational microscope" to observe biological processes at an atomic level of detail [32] [33]. The core of any MD simulation is the force field—a set of mathematical functions and parameters that describe the potential energy of a molecular system as a function of the coordinates of its atoms [34] [35]. This whitepaper explores the principles of MD simulations, the construction and function of force fields, and their indispensable role in bridging the gap between sequence, structure, and function, thereby offering a resolution to the conceptual challenges posed by Levinthal.

Molecular Dynamics: A Theoretical Framework

Basic Principles and Historical Context

Molecular Dynamics is a computer simulation method for analyzing the physical movements of atoms and molecules. The core principle involves numerically solving Newton's equations of motion for a system of interacting particles, where forces between particles and their potential energies are calculated using interatomic potentials or molecular mechanical force fields [32]. Given the positions of all atoms, the force on each atom is calculated, and Newton's laws are used to predict its new position and velocity after a very short time step, typically on the order of femtoseconds (10â»Â¹âµ s) [33]. This process is repeated millions or billions of times to generate a trajectory—a dynamic view of the system's evolution over time [33].

The method has its roots in the late 1950s with simulations of simple gasses [32]. The first MD simulation of a protein was performed in the late 1970s, and the foundational work enabling these simulations was recognized by the 2013 Nobel Prize in Chemistry [33]. Initially a tool for theoretical physicists and materials scientists, MD has since become a cornerstone technique in biochemistry and biophysics, propelled by exponential growth in computational power and algorithmic improvements [32].

Addressing Levinthal's Paradox with MD

Levinthal's paradox points out the impossibility of a protein finding its native state via a random conformational search, as the number of possible conformations is astronomically large [17] [36]. MD simulations offer a solution to this paradox not by performing this random search, but by simulating the actual physical forces that guide the protein along a biased, energetically favorable pathway.

The energy landscape theory of protein folding, which frames folding as a funnel-guided process where native states occupy energy minima, is perfectly suited for investigation via MD [4]. Simulations can directly probe this landscape, revealing the kinetic pathways and intermediate states that proteins traverse as they fold. Furthermore, MD can capture the crucial role of the cellular environment, including solvent effects and molecular chaperones, which help proteins avoid misfolding and aggregation, thus explaining how reliable folding occurs in vivo despite the paradox [4]. While pure ab initio folding of proteins from an unfolded state remains computationally demanding, MD simulations are increasingly used to refine predicted structures and study conformational dynamics critical to biological function [32] [37].

The Engine of Simulation: Molecular Mechanics Force Fields

The Concept of a Force Field

A force field is a computational model used to calculate the potential energy of a system of atoms based on their positions [34]. It consists of two key components:

- The functional form, which is the mathematical expression for the different energy terms.

- The parameter sets, which are the specific numerical values (e.g., equilibrium bond lengths, force constants, atomic charges) used in the functions for different types of atoms and bonds [34] [38].

The basic functional form decomposes the total potential energy ((E{total})) into contributions from bonded interactions (atoms linked by covalent bonds) and non-bonded interactions (atoms in different molecules or separated by three or more bonds) [34] [35]: (E{total} = E{bonded} + E{non-bonded})

Components of a Biomolecular Force Field

The energy terms in a typical Class I biomolecular force field (e.g., AMBER, CHARMM, OPLS) are detailed below.

Bonded Interactions

Bonded interactions describe the energy associated with the covalent geometry of the molecule.

Bond Stretching: The energy required to stretch or compress a covalent bond from its equilibrium length. It is typically modeled by a harmonic potential: (E{bond} = \sum{bonds} \frac{kb}{2}(l{ij} - l0)^2) where (kb) is the bond force constant, (l{ij}) is the actual bond length, and (l0) is the equilibrium bond length [34] [35].

Angle Bending: The energy required to bend the angle between three bonded atoms from its equilibrium value. Also modeled by a harmonic potential: (E{angle} = \sum{angles} \frac{k\theta}{2}(\theta{ijk} - \theta0)^2) where (k\theta) is the angle force constant, (\theta{ijk}) is the actual angle, and (\theta0) is the equilibrium angle [34] [35].

Torsion (Dihedral) Angle Rotation: The energy associated with rotation around a central bond connecting four sequentially bonded atoms. This term describes the periodicity of energy barriers and is modeled by a periodic function: (E{dihedral} = \sum{dihedrals} k\phi[1 + cos(n\phi - \delta)]) where (k\phi) is the dihedral force constant, (n) is the periodicity (number of minima in 360°), (\phi) is the dihedral angle, and (\delta) is the phase shift [34] [35].

Improper Torsions: Used primarily to enforce planarity in aromatic rings and other conjugated systems, often using a harmonic potential [35].

Non-Bonded Interactions

Non-bonded interactions describe the forces between atoms that are not directly covalently bonded.

Van der Waals Forces: These include short-range attractive (dispersion) and repulsive (Pauli exclusion) forces. They are most commonly described by the Lennard-Jones 12-6 potential: (E{vdW} = \sum{i

{ij} \left[ \left(\frac{\sigma{ij}}{r{ij}}\right)^{12} - \left(\frac{\sigma{ij}}{r{ij}}\right)^{6} \right]) where (\epsilon{ij}) is the depth of the potential well, (\sigma{ij}) is the distance at which the interparticle potential is zero, and (r{ij}) is the distance between atoms [34] [35]. The (r^{-12}) term describes repulsion, while the (r^{-6}) term describes attraction. }>Electrostatic Interactions: The classical interaction between partial atomic charges, calculated using Coulomb's law: (E{elec} = \sum{i

i qj}{4\pi\epsilon0 \epsilonr r{ij}}) where (qi) and (qj) are the partial charges on atoms, (r{ij}) is their distance, (\epsilon0) is the permittivity of free space, and (\epsilonr) is the relative dielectric constant [34] [35]. }>

Table 1: Core Energy Terms in a Classical Biomolecular Force Field

| Interaction Type | Mathematical Form | Key Parameters | Physical Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bond Stretching | (E = \frac{kb}{2}(l - l0)^2) | (kb) (force constant), (l0) (eq. length) | Energetic cost of stretching/compressing a covalent bond. |

| Angle Bending | (E = \frac{k\theta}{2}(\theta - \theta0)^2) | (k\theta) (force constant), (\theta0) (eq. angle) | Energetic cost of bending the angle between three bonded atoms. |

| Torsion (Dihedral) | (E = k_\phi[1 + cos(n\phi - \delta)]) | (k_\phi) (barrier height), (n) (periodicity), (\delta) (phase) | Energy barrier for rotation around a central bond; defines conformational preferences. |

| Van der Waals | (E = 4\epsilon \left[ (\frac{\sigma}{r})^{12} - (\frac{\sigma}{r})^{6} \right]) | (\epsilon) (well depth), (\sigma) (vdW radius) | Short-range attraction and repulsion between electron clouds. |

| Electrostatic | (E = \frac{qi qj}{4\pi\epsilon_0 r}) | (qi, qj) (atomic partial charges) | Long-range attraction/repulsion between charged or polar atoms. |

The following diagram illustrates the relationships between these different energy components and the overall potential energy calculation in a force field.

Parameterization and Classification of Force Fields

The accuracy of a force field is entirely dependent on the quality of its parameters. These are derived from a combination of quantum mechanical calculations on small molecules and experimental data, such as enthalpies of vaporization, liquid densities, and spectroscopic properties [34]. A critical concept in force field development is the definition of atom types, which classify atoms not only by their element but also by their chemical environment (e.g., an oxygen in a carbonyl group vs. an oxygen in a hydroxyl group) [34] [38].

Force fields can be broadly categorized into several classes:

- Class I (e.g., AMBER, CHARMM, OPLS): Use simple harmonic potentials for bonds and angles and do not include explicit cross-terms. They offer a good balance of accuracy and computational efficiency for biomolecular simulations [35] [38].

- Class II (e.g., MMFF94): Include anharmonic terms and cross-terms coupling bonds, angles, and dihedrals for higher accuracy in small molecules [35].

- Class III (Polarizable Force Fields, e.g., AMOEBA, Drude): Explicitly model the redistribution of electron density (polarization) in response to the environment, using methods like inducible point dipoles or Drude oscillators. These are more accurate but computationally expensive [35].

Table 2: Popular Biomolecular Force Fields and Their Characteristics

| Force Field | Class | Common Applications | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| AMBER | I | Proteins, Nucleic Acids | Well-parameterized for standard biomolecules; widely used in drug discovery. |

| CHARMM | I | Proteins, Lipids, Carbohydrates | Broad coverage of biomolecules and membrane systems. |

| OPLS | I | Proteins, Organic Molecules | Optimized for liquid-state properties and protein-ligand interactions. |

| GROMOS | I | Biomolecules in solution | Unified atom approach (hydrogens combined with heavy atoms); parameterized for consistency with experimental data. |

| AMOEBA | III | Polarizable Systems | Includes induced atomic dipoles; improved description of electrostatic interactions. |

Practical Implementation and Protocol

Setting up and running an MD simulation involves a standardized workflow. The diagram below outlines the key steps, from initial structure preparation to final trajectory analysis.

Step 1: Initial Structure Preparation The simulation begins with an initial atomic coordinate set, typically obtained from the Protein Data Bank (PDB), from AI-based prediction tools like AlphaFold, or from de novo modeling [36]. This structure must be checked for missing atoms, protonation states, and disulfide bonds.

Step 2: System Setup The biomolecule is placed in a simulation box, which is then filled with solvent molecules (e.g., TIP3P, SPC/E water models). Ions are added to neutralize the system's charge and to achieve a physiologically relevant salt concentration [32] [33]. The choice between an explicit solvent model (more accurate but costly) and an implicit solvent model (mean-field approximation, faster) is a key consideration [32].

Step 3: Energy Minimization The system is energy-minimized to remove any steric clashes or unphysical geometry introduced during setup. This step finds the nearest local energy minimum by algorithms like steepest descent or conjugate gradient [32].

Step 4: Equilibration Before production data collection, the system must be equilibrated under the desired thermodynamic conditions.

- NVT Equilibration: The Number of particles, Volume, and Temperature are held constant. This allows the system to reach the target temperature (e.g., 310 K).

- NPT Equilibration: The Number of particles, Pressure, and Temperature are held constant. This allows the density of the system (e.g., solvent box) to adjust to the target pressure (e.g., 1 bar) [32].

Step 5: Production MD This is the main simulation phase where the trajectory used for analysis is generated. The system is propagated for nanoseconds to microseconds, with coordinates and velocities saved at regular intervals [32] [33]. The long timescales required to observe many biologically relevant processes (e.g., protein folding) remain a key computational challenge.

Step 6: Trajectory Analysis The saved trajectory is analyzed to extract biologically meaningful information. Common analyses include:

- Calculating Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) to measure structural stability.

- Determining Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF) to identify flexible regions.

- Studying hydrogen bonding networks and salt bridge formation.

- Performing principal component analysis (PCA) to identify large-scale collective motions [33].

Table 3: Essential "Research Reagent Solutions" for an MD Simulation

| Item / Resource | Category | Function / Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Input Structure | Repository of experimentally determined 3D structures of proteins and nucleic acids to use as starting points. |

| AlphaFold Protein Structure Database | Input Structure | Source of highly accurate predicted protein structures for proteins with unknown experimental structures [36]. |

| AMBER/CHARMM/OPLS Force Field | Energy Model | Defines the mathematical functions and parameters for calculating potential energy and forces between atoms [38]. |

| TIP3P / SPC/E Water Model | Solvent | Explicit solvent model representing water molecules in the system, crucial for simulating a physiological environment. |

| GRGMACS / NAMD / AMBER | MD Engine | Software package that performs the numerical integration of Newton's equations of motion and calculates forces. |

| Graphics Processing Unit (GPU) | Hardware | Specialized hardware that dramatically accelerates the computation of non-bonded interactions, making longer simulations feasible [33]. |

Limitations, Challenges, and Future Directions

Despite its power, the MD method has important limitations. The accuracy of any simulation is fundamentally limited by the force field [32]. Classical force fields use fixed atomic charges and cannot model chemical reactions where bonds form or break; such processes require hybrid QM/MM (Quantum Mechanics/Molecular Mechanics) methods [33]. The timescale barrier is another major challenge, as many biologically important events (e.g., full protein folding, large conformational changes in enzymes) occur on millisecond to second timescales, while even state-of-the-art simulations are typically limited to microseconds [32] [33].

A significant conceptual challenge, highlighted in recent critical assessments, is that MD simulations and AI-based structure prediction tools like AlphaFold often rely on static structures determined in non-physiological conditions (e.g., X-ray crystallography) [17] [37]. This creates a potential disconnect from the true, dynamic, and environmentally-sensitive functional structure of proteins in solution, a concept analogous to the Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle in quantum mechanics, where the act of measurement (structure determination) can perturb the system [17].

Future developments are focused on creating more accurate and polarizable force fields, harnessing exascale computing to access longer timescales, and developing enhanced sampling methods to more efficiently explore complex energy landscapes [33] [35]. The integration of MD with experimental data from techniques like cryo-EM, NMR, and single-molecule force spectroscopy (e.g., magnetic tweezers) will be crucial for validating simulations and building models that truly capture the dynamic reality of biological molecules [19].

Molecular Dynamics, powered by empirical force fields, has firmly established itself as an indispensable computational microscope. It provides a unique, atomic-resolution view of biological processes in motion, offering a powerful framework to confront fundamental problems like Levinthal's paradox. By simulating the physical forces that guide a protein along its folding funnel and through its functional conformational ensemble, MD moves beyond static snapshots to a dynamic understanding of biomolecular function. While challenges in accuracy, timescale, and the representation of the native biological environment remain, ongoing advances in force field design, computational hardware, and integrative modeling ensure that MD will continue to be a cornerstone technique for researchers and drug developers seeking to understand and manipulate the machinery of life at the atomic level.

The process of protein folding, whereby an amino acid chain adopts its unique, functional three-dimensional structure, occurs on timescales of microseconds to minutes. This presents a fundamental paradox, as a random search of all possible conformations would take an astronomically longer time. This is the essence of Levinthal's paradox, which has historically framed the protein folding problem [17]. The resolution lies not in a random search but in the presence of a biased energy landscape, where the protein is funneled towards its native state. The actual transition from the unfolded to the folded state is not a gradual shift but a stochastic process where the protein must surmount a free energy barrier. The fleeting event of crossing this barrier is the transition path [39].

Understanding the transition path is critical for a complete molecular understanding of folding and function. Direct experimental observation of these paths provides a window into the dynamics of barrier crossing, a process central to chemical reactions, molecular recognition, and, by extension, rational drug design [39] [40]. Modern molecular dynamics (MD) simulations have become indispensable tools for investigating these phenomena, allowing researchers to capture the continuous conformational changes and transient states that are challenging to observe experimentally [41] [40]. This guide delves into the quantitative characterization, methodologies, and research tools for capturing and analyzing these critical transition paths.

Quantitative Characterization of the Transition Path

The transition path (TP) is formally defined as the piece of a molecular trajectory that begins when the system enters a predefined transition region from the reactant state (e.g., unfolded) and ends when it exits to the product state (e.g., folded), without recrossing the boundaries [39]. Several key metrics are used to quantify its properties.

Key Transition Path Metrics and Formulations

Table 1: Core Quantitative Definitions for Transition Path Analysis.

| Metric | Mathematical Definition | Physical Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Transition Path Time (TPT) | ( t_{TP} ) | The mean temporal length of a transition path; the direct transit time between state boundaries [39]. |

| Transition Path Velocity ((v_{TP}(x))) | ( \frac{1}{v{TP}(x)} = \lim{\Delta x \to 0} \frac{\Delta t(x-\Delta x/2, x+\Delta x/2)}{\Delta x} ) | An effective local velocity defined by the cumulative residence time in an interval, not the instantaneous speed. It preserves statistical information about recrossings [39]. |

| Reactive Flux | ( F{A \to B} = v{TP}(x) p_{eq}(x) P(TP \mid x) ) | The exact, local expression for the equilibrium unidirectional flux from state A to state B, which is independent of the coordinate ( x ) [39]. |

| Exact Transition Rate | ( k{A \to B} = PA^{-1} v{TP}(x) p{eq}(x) P(TP \mid x) ) | A generalization of Transition State Theory that uses the transition-path velocity to provide the exact transition rate, accounting for dynamics [39]. |

Insights from Simulation Data

Molecular dynamics simulations provide numerical insights into these quantities. For instance, a 12.6 μsec simulation of a 20-residue triple-stranded β-sheet peptide (Beta3s) revealed key statistics of the folding process, demonstrating the efficiency of the search on a biased energy landscape [41].

Table 2: Representative Transition Path Data from MD Simulations of Beta3s Folding [41].

| Parameter | Value from Beta3s Simulation | Context and Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Total Simulation Time | 12.6 μsec | Much longer than the system's relaxation time, ensuring adequate sampling of folding/unfolding events. |

| Average Folding Time | ~85 nsec | Similar to the unfolding time at the melting temperature, indicating equal population of states. |

| Clusters Sampled During a Folding Event | < 400 | A minute fraction of the total conformers in the denatured state, illustrating a directed, non-random search. |

| Total Conformers (Cluster Centers) in Denatured State | > 15,000 | Highlights the vastness of the unfolded state ensemble, consistent with the underlying premise of Levinthal's paradox. |

Methodologies for Capturing and Analyzing Transition Paths

Experimental and Computational Workflows

Studying transition paths requires a combination of high-resolution experimental techniques and sophisticated computational simulations. The following diagram outlines a generalized, integrated workflow for these studies.

Diagram 1: Workflow for Transition Path Analysis.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Single-Molecule Force Spectroscopy for Transition Path Observation

This protocol details the process for using force spectroscopy to directly observe transition paths in protein folding, as referenced in studies of protein and DNA dynamics [39].