Overcoming Poor Molecular Sampling: Strategies for Accurate Solute Characterization in Solution

This article addresses the critical challenge of poor sampling of solute molecules in solution, a major bottleneck in drug development and materials science.

Overcoming Poor Molecular Sampling: Strategies for Accurate Solute Characterization in Solution

Abstract

This article addresses the critical challenge of poor sampling of solute molecules in solution, a major bottleneck in drug development and materials science. We explore the foundational causes of sampling errors, from material incompatibility to inadequate experimental design. The piece provides a comprehensive overview of modern computational and experimental methodologies, including machine learning models for solubility prediction and Bayesian optimization for efficient parameter space exploration. A dedicated troubleshooting section offers practical solutions for common pitfalls like adsorption, corrosion, and non-response in high-throughput screens. Finally, we present rigorous validation frameworks and comparative analyses of current techniques, equipping researchers with a holistic strategy to enhance reliability and accelerate discovery in biomedical research.

The Sampling Problem: Why Molecular Representation Fails in Solution

Troubleshooting Guide: Identifying and Resolving Poor Sampling

Q1: My molecular dynamics simulation results seem inconsistent and not reproducible. What could be the root cause? This is a classic symptom of poor sampling, where your simulation has not adequately explored the configurational space of your solute-solvent system. The primary cause is often an insufficient simulation time relative to the system's slowest relaxation processes, leading to high statistical uncertainty in your computed observables [1].

- Diagnosis & Solution:

- Check for Correlated Data: Calculate the statistical inefficiency or correlation time of your key trajectory data (e.g., potential energy, radius of gyration). If your analysis interval is shorter than this correlation time, your data points are not independent, and your reported uncertainties will be deceptively small [1].

- Quantify Uncertainty: Use the "experimental standard deviation of the mean" (often called the standard error) to estimate the uncertainty in your results. A large error bar relative to the mean value is a strong indicator of poor sampling [1].

- Extend Simulation Time: The most direct solution is to run a longer simulation. Before doing so, perform a back-of-the-envelope calculation to estimate the time scales of the molecular motions you are trying to capture to ensure feasibility [1].

- Consider Enhanced Sampling: For systems with high energy barriers, use advanced sampling techniques (e.g., metadynamics, replica exchange) to improve phase-space exploration efficiently [1].

Q2: My machine learning model for molecular activity prediction performs well on the training data but fails on new, structurally diverse compounds. Why? This indicates a sampling bias in your training data, also known as a representation problem. If your training set does not adequately represent the broader chemical space you are trying to predict, the model cannot learn generalizable rules [2] [3].

- Diagnosis & Solution:

- Analyze Data Distribution: Characterize the chemical space of your training and test sets using molecular descriptors or fingerprints. If the test set occupies a region sparsely populated in the training data, you have an undercoverage bias [2] [3].

- Use Stratified Sampling: When creating your training and test sets, ensure they are stratified across key dimensions of chemical diversity (e.g., scaffold type, molecular weight, logP) rather than using a random or convenience sample [4] [3].

- Employ Advanced Representations: Move beyond simple fingerprints to AI-driven molecular representations. Graph-based models and language models can capture richer structural nuances and relationships, potentially improving generalization to novel scaffolds [2].

Q3: How can I be confident that my sampling is adequate for calculating a binding free energy? Confidence comes from robust convergence analysis and uncertainty quantification. A single simulation, no matter how long, is often insufficient to prove convergence [1].

- Diagnosis & Solution:

- Run Multiple Replicas: Initiate several independent simulations from different initial conditions. If all replicas converge to the same average value for your observable, it is a strong indicator of adequate sampling.

- Perform Block Averaging: Divide your simulation trajectory into consecutive blocks of increasing length. Plot the calculated average for each block. When the averages plateau and stop fluctuating significantly as block length increases, your result is likely converged [1].

- Report Full Uncertainty: Always report the standard uncertainty (e.g., standard error of the mean) alongside your final estimated value. This communicates the reliability and precision of your result to other researchers [1].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: What is the difference between sampling bias in statistics and poor sampling in molecular simulation?

- Sampling Bias is a problem in study design where some members of a population are systematically more likely to be selected than others, compromising the generalizability of the findings [4] [3]. In drug discovery, this could mean training a model only on flat, aromatic molecules and expecting it to perform well on complex 3D macrocycles.

- Poor Sampling in simulation is a problem of numerical adequacy where a computational experiment has not run long enough to provide a statistically reliable estimate of a property, even if the model itself is perfect [1].

Q: How does molecular representation relate to sampling? Molecular representation is the foundation of all subsequent analysis. A poor representation can introduce a form of implicit bias [2]. For example:

- Traditional SMILES strings can imply an incorrect prioritization of atoms, confusing a model.

- Simple fingerprints may miss critical 3D spatial information.

- Solution: Modern, AI-driven representations (e.g., from Graph Neural Networks) learn continuous embeddings that can more effectively capture essential features for activity, guiding the sampling of chemical space toward more relevant regions for tasks like scaffold hopping [2].

Q: What are some best practices to avoid sampling bias in my research dataset?

- Clearly Define Population: Start by clearly defining your target population (e.g., "all FDA-approved small molecule drugs") [3].

- Use a Proper Sampling Frame: Ensure the list you are drawing from (your sampling frame) matches this population as closely as possible [4].

- Avoid Convenience Sampling: Do not just use easily available compounds. Actively seek to include representatives from underrepresented groups or regions of chemical space (oversampling) to ensure diversity [4] [3].

- Follow Up on Non-Responders: In experimental settings, if certain data points are hard to acquire (e.g., compounds with poor solubility), investigate them rather than excluding them, as they may represent an important class (addressing non-response bias) [4].

Quantitative Data: Assessing Sampling Quality

Table 1: Key Statistical Metrics for Sampling Assessment [1]

| Metric | Formula | Interpretation | Threshold for "Good" Sampling |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arithmetic Mean | x̄ = (1/n) * Σx_i |

The best estimate of the true expectation value. | N/A |

| Experimental Standard Deviation | s(x) = sqrt( [Σ(x_i - x̄)²] / (n-1) ) |

Measures the spread of the data points. | N/A |

| Correlation Time (Ï„) | Statistical analysis of time-series (e.g., autocorrelation). | The time separation needed for two data points to be considered independent. | As small as possible relative to total simulation time. |

| Experimental Standard Deviation of the Mean (Standard Error) | s(x̄) = s(x) / sqrt(n) |

The standard uncertainty in the estimated mean. A key result to report. | Small relative to the mean (e.g., < 10% of x̄). |

| Statistical Inefficiency (g) | g = 1 + 2 * Σ_{k=1} Ï(k) |

The number of steps between uncorrelated samples. | Close to 1. |

Experimental Protocols for Sampling Validation

Protocol 1: Assessing Convergence via Block Averaging Analysis

Objective: To determine if a simulated observable has converged to its true equilibrium value. Materials: Molecular dynamics trajectory file, data for a key observable (e.g., potential energy). Method:

- Data Preparation: Extract the time-series data for the observable from the entire trajectory.

- Blocking: Divide the total trajectory of length N into n_b consecutive blocks of increasing length L (where L = N / n_b).

- Averaging: Calculate the average of the observable within each block.

- Calculation: Compute the standard deviation of these block averages.

- Plotting: Plot this standard deviation as a function of block length L. Interpretation: The observable is considered converged when the standard deviation of the block averages plateaus and no longer shows a systematic decrease with increasing block length. A continuing decrease indicates insufficient sampling [1].

Protocol 2: Conducting a Multiple Replica Simulation

Objective: To build confidence in a simulation result by demonstrating consistency across independent trials. Materials: Molecular system structure, simulation software. Method:

- Replica Generation: Prepare a minimum of 3-5 independent copies (replicas) of the system.

- Independent Initialization: Assign different random seeds for initial velocities to each replica. For complex systems, consider starting from different conformations.

- Parallel Execution: Run all simulations for the same duration using identical parameters.

- Analysis: Calculate the average and standard error for your key observable across the different replicas. Interpretation: If the averages from all replicas agree within their calculated standard errors, it provides strong evidence that the sampling is adequate. Significant divergence suggests that the simulation time is too short or that the system is trapped in different local minima [1].

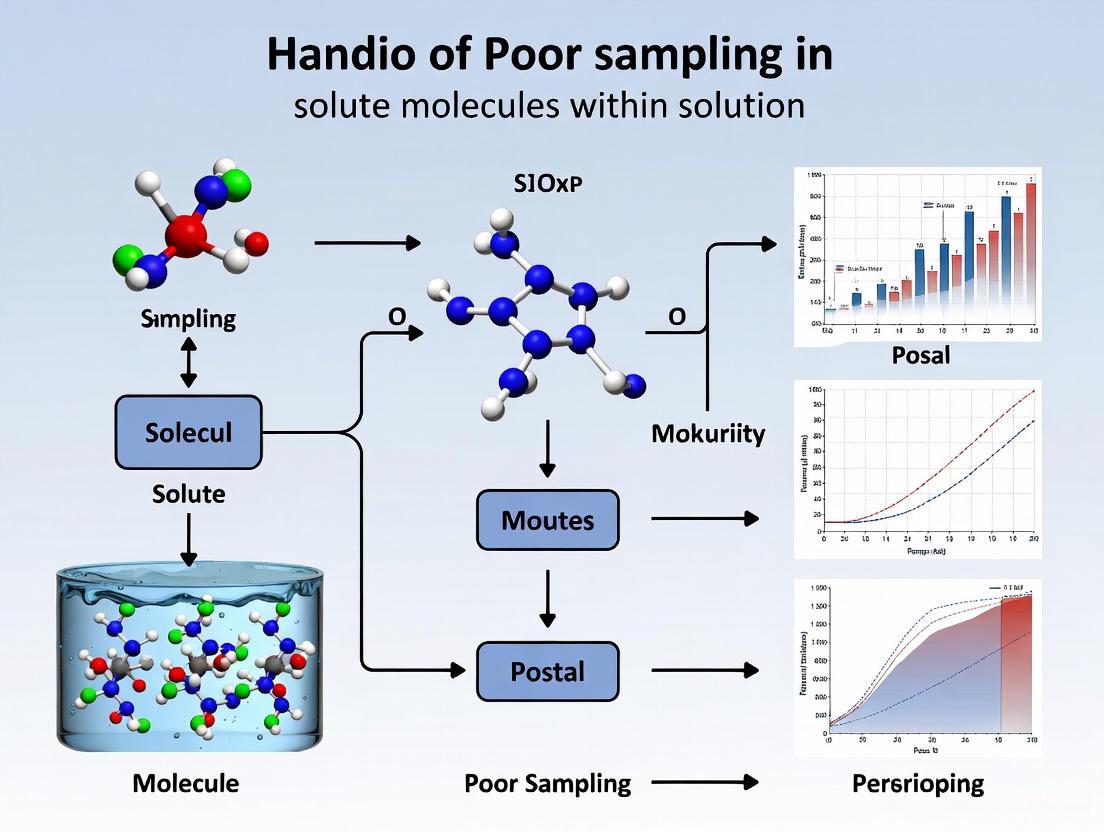

Workflow Visualization: From Problem to Solution

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools for Sampling Analysis

| Item | Function/Brief Explanation |

|---|---|

| Molecular Dynamics Engine (e.g., GROMACS, AMBER, NAMD) | Software to perform the primary simulation, generating the trajectory data by numerically solving equations of motion. |

| Monte Carlo Sampling Software | Software that uses random sampling based on energy criteria to explore configurational space, an alternative to MD. |

| Statistical Analysis Library (e.g., NumPy, SciPy, pymbar) | Python libraries essential for calculating correlation times, block averages, standard errors, and other statistical metrics. |

| Molecular Descriptor/Fingerprint Calculator (e.g., RDKit) | Computes numerical representations (e.g., ECFP fingerprints, topological indices) to quantify and compare molecular structures and diversity [2]. |

| Enhanced Sampling Suites (e.g., PLUMED) | Software plugins that implement advanced methods like metadynamics or replica exchange to accelerate the sampling of rare events. |

| Visualization Tool (e.g., VMD, PyMOL) | Allows for the visual inspection of trajectories to identify conformational changes and spot-check sampling qualitatively. |

| Ebov-IN-10 | Ebov-IN-10, MF:C22H22N2O2S, MW:378.5 g/mol |

| LQZ-7F | LQZ-7F, MF:C14H7N9O3, MW:349.26 g/mol |

The High Cost of Sampling Errors in Drug Development and Formulation

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Inconsistent Experimental Results Across Batches

Problem: Your experimental results show high variability between batches of the same formulation, making it difficult to reproduce findings reliably.

Diagnosis: This is frequently caused by population specification errors and sample frame errors in your sampling methodology [5] [6]. When the subpopulation of solute molecules being sampled doesn't accurately represent the entire solution, statistical validity is compromised.

Solution:

- Map the Complete Population: Before sampling, characterize your solution's full parameter space including pH gradients, temperature variations, concentration distributions, and mixing dynamics [6].

- Implement Stratified Random Sampling: Divide your solution into homogeneous strata based on critical parameters (e.g., viscosity zones, concentration layers) and sample randomly from each stratum [6].

- Standardize Sampling Protocol: Establish fixed sampling locations, timing relative to mixing, and container geometries to minimize introduction of variables.

- Validate with Replicates: Include triplicate sampling at each time point with statistical analysis of variance.

Validation Protocol:

- Calculate coefficient of variation across replicate samples (target <5%)

- Perform statistical process control charting of critical quality attributes

- Confirm sample means fall within 90% confidence intervals of population parameters [6]

Issue 2: Failed Bioequivalence Studies Due to Formulation Variance

Problem: Your generic drug formulation fails bioequivalence testing despite chemical similarity to the reference product, delaying regulatory approval and costing millions.

Diagnosis: This often stems from selection errors in sampling during formulation development, particularly when samples don't capture the full range of physicochemical variability [5] [7]. Even minor inconsistencies in solute distribution can significantly impact drug release profiles.

Solution:

- Enhanced Sampling During Critical Manufacturing Steps: Focus sampling on high-risk process points including phase transitions, mixing endpoints, and filling operations.

- Q1/Q2/Q3 Sameness Verification: Implement rigorous sampling to demonstrate qualitative (Q1) and quantitative (Q2) sameness of inactive ingredients, and sameness of microstructure (Q3) properties [7].

- Predictive Analytical Sampling: Develop sampling protocols that specifically target parameters most likely to affect bioavailability - particle size distribution, polymorphism, and dissolution characteristics.

- Accelerated Stability Sampling: Design stability testing sampling schedules that detect deviations early through increased sampling frequency during initial time points.

Experimental Protocol for Bioequivalence Risk Mitigation:

- Sample size: Minimum of 30 sampling points across batch and time

- Parameters: Particle size distribution, crystallinity, viscosity, pH

- Frequency: 0, 3, 6, 9, 12, 18, 24 months for stability studies

- Acceptance criteria: 90% confidence intervals for AUC and Cmax ratios must fall within 80-125% [7]

Issue 3: High Variability in High-Concentration Biologic Formulations

Problem: Developing high-concentration (≥100 mg/mL) subcutaneous biologic formulations leads to inconsistent results, with significant variability in viscosity, aggregation, and stability measurements.

Diagnosis: This represents a classic non-response error in characterization, where your sampling misses critical molecular interactions and aggregation hotspots [8] [9]. At high concentrations, sampling must capture rare but consequential events like protein-protein interactions and nucleation sites.

Solution:

- Multi-Scale Sampling Approach: Implement correlated sampling across molecular (nanoscale), microscopic (microscale), and bulk (macroscale) levels.

- Stress Condition Sampling: Intentionally sample under stressed conditions (temperature, shear, interfacial exposure) to identify failure modes early.

- Container Interaction Sampling: Sample from multiple locations within primary containers, particularly liquid-solid interfaces where adsorption and degradation often initiate.

- Real-Time Process Analytical Technology: Implement in-line sampling with UV, NIR, or Raman spectroscopy to capture dynamic changes during manufacturing.

Validation Metrics:

- Consistency in viscosity measurements (<10% CV across samples)

- Subvisible particle counts meeting pre-established criteria

- Demonstration of uniformity in drug concentration across container locations (<2% variance)

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the actual financial impact of sampling errors in drug development?

Sampling errors have profound financial implications throughout the drug development pipeline:

Table 1: Financial Impact of Sampling and Formulation Errors

| Error Type | Stage Impacted | Typical Cost Impact | Timeline Delay |

|---|---|---|---|

| Population Specification Error | Early Discovery | $150K - $1.5M in repeated experiments [10] [11] | 1-3 months |

| Sample Frame Error | Preclinical Development | $1M - $5M in toxicology repeats [11] | 3-6 months |

| Formulation Variance Error | Clinical Phase | $5M - $20M in failed bioequivalence [7] | 6-12 months |

| High-Concentration Challenge | Biologics Development | $10M - $50M in reformulation [8] | 9-18 months |

The median cost of developing a new drug is approximately $708 million, with sampling and formulation errors contributing significantly to the upper range of $1.3 billion or more for problematic developments [10] [11]. Recent surveys of drug formulation experts reveal that 69% experience clinical trial or product launch delays due to formulation challenges, with weighted average delays of 11.3 months, while 4.3% report complete trial or launch cancellation due to these issues [8].

Q2: How do sampling errors differ from other experimental errors in pharmaceutical research?

Table 2: Classification of Research Errors in Drug Development

| Error Category | Definition | Examples in Drug Formulation | Mitigation Strategies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sampling Errors | Deviation between sample values and true population values [5] [6] | Unrepresentative solute concentration measurements; biased particle size distribution | Increase sample size; stratified random sampling; improved sample design [6] |

| Non-Sampling Errors | Deficiencies in research execution unrelated to sampling [5] [9] | Instrument calibration drift; data entry mistakes; respondent bias in clinical assessments | Quality control systems; training; automation; validation protocols [9] |

| Formulation-Specific Errors | Errors unique to pharmaceutical development | Incorrect excipient compatibility assessment; container closure interactions; stability misinterpretation | QbD principles; DOE approaches; predictive modeling |

Sampling errors are particularly problematic because they can't be completely eliminated, only reduced, and they affect the fundamental representativeness of your data [5]. Unlike measurement errors that can be corrected with better instrumentation, sampling errors are baked into your experimental design and can invalidate entire research programs if not properly addressed.

Q3: What are the most effective strategies to minimize sampling errors in solution-based research?

Systematic Sampling Framework:

- Define Population Parameters Completely: Characterize the entire universe of solute molecules you need to represent - including spatial distribution, temporal variations, and environmental influences [6].

- Implement Appropriate Sampling Techniques:

- For homogeneous solutions: Simple random sampling

- For heterogeneous systems: Stratified or systematic sampling

- For time-dependent processes: Longitudinal sampling at strategic intervals

- Validate Sampling Representatives: Use statistical tests to confirm your samples accurately reflect population parameters.

- Document Sampling Methodology Completely: Ensure complete traceability of sampling decisions for regulatory submissions.

Advanced Approach: Utilize Design of Experiments (DOE) principles to optimize sampling strategies rather than relying on arbitrary sampling schedules. This includes determining optimal sample size, location, and timing through statistical power analysis rather than convention.

Experimental Protocols for Robust Sampling

Protocol 1: Comprehensive Solute Sampling in Formulation Development

Purpose: To obtain representative samples of solute molecules throughout formulation development that accurately reflect the true population characteristics.

Materials:

- Automated sampling station with precision fluid handling

- Multiple container geometries representative of manufacturing scale

- In-line analytical probes (UV, NIR, Raman)

- Statistical sampling software for sample size determination

Procedure:

- Pre-Sampling Characterization:

- Map the complete parameter space of your solution (pH, temperature, concentration gradients)

- Identify potential heterogeneity sources (mixing dead zones, interfacial effects)

- Determine minimum sample size using power analysis (typically n≥30 for normal distributions)

Stratified Sampling Plan:

- Divide solution into homogeneous strata based on identified parameters

- Allocate samples proportional to stratum size and variability

- Include boundary layers and interfaces as separate strata

Sampling Execution:

- Utilize random sampling within each stratum

- Maintain consistent sampling technique across operators

- Document environmental conditions at each sampling point

Representativeness Validation:

- Statistical comparison of sample means to population parameters

- Analysis of variance between strata

- Confidence interval calculation for critical quality attributes

Acceptance Criteria: Sample measurements must fall within 95% confidence intervals of population parameters with less than 5% coefficient of variation between replicate samples.

Protocol 2: Sampling for Bioequivalence Risk Assessment

Purpose: To detect formulation differences that could impact bioequivalence during generic drug development.

Materials:

- USP dissolution apparatus with automated sampling

- HPLC/UPLC systems with validated methods

- Particle characterization instrumentation

- Stability chambers with controlled sampling ports

Critical Sampling Points:

- Drug Substance Characterization:

- Sample multiple batches (minimum 3)

- Sample throughout crystallization process

- Analyze polymorphic form, particle size, purity

Formulation Process Sampling:

- Blend uniformity sampling per FDA guidance

- In-process controls during critical manufacturing steps

- Final product sampling from beginning, middle, and end of run

Dissolution Performance Sampling:

- Time-point sampling per dissolution method requirements

- Multiple vessel sampling to assess variability

- Sampling under different physiological conditions

Stability Study Sampling:

- Accelerated conditions (40°C/75% RH)

- Intermediate conditions (30°C/65% RH)

- Long-term conditions (25°C/60% RH)

- Sample at predetermined time points with statistical sampling plan

Analytical Methodology: All samples must be analyzed using validated methods with demonstrated specificity, accuracy, precision, and robustness.

Visualization of Sampling Strategies

Sampling Strategy Decision Framework

Error Classification and Mitigation Pathway

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Robust Sampling in Formulation Research

| Material/Reagent | Function | Application Notes | Quality Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|

| Automated Sampling Stations | Precise, reproducible sample collection | Reduces operator-induced variability; enables time-series sampling | Calibration certification; precision <1% CV |

| Stratified Sampling Containers | Physical implementation of stratified sampling | Specialized containers with multiple ports for spatial sampling | Material compatibility; minimal adsorption |

| Process Analytical Technology (PAT) | Real-time, in-line monitoring | NIR, UV, Raman for continuous quality assessment | Validation per ICH Q2(R1) |

| Stability Chambers | Controlled stress testing | ICH-compliant environmental control | Temperature ±2°C; RH ±5% |

| Reference Standards | Method validation and calibration | USP, EP, or qualified internal standards | Certified purity; stability documentation |

| Container Closure Systems | Representative packaging | Sampling from actual product containers | Representative of manufacturing scale |

| Data Management Systems | Statistical sampling design and analysis | Sample size calculation; random allocation | 21 CFR Part 11 compliance |

These materials form the foundation of robust sampling programs that can detect and prevent the costly errors that routinely impact drug development timelines and budgets. Proper implementation requires both the physical tools and the statistical framework to ensure sampling representatives throughout the formulation development process.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What defines a "Small Sample & Imbalance" (S&I) problem in my experimental data? An S&I problem exists when your dataset simultaneously meets two conditions: the total number of samples (N) is too small for effective model generalization (N << M, where M is the application's standard dataset size), and the sample ratio of at least one class is significantly smaller than the others [12].

Q2: Why do standard machine learning models perform poorly on my imbalanced experimental data? Classifiers tend to be biased toward the majority class, compromising generality and performance on minority classes of interest [13]. This issue is exacerbated by small sample sizes, where models cannot learn robust patterns, leading to overfitting and poor generalization [12].

Q3: What is "class overlap," and how does it complicate my analysis? Class overlap occurs in the feature space where samples from different classes have similar feature values, making it challenging to determine class boundaries [13]. In imbalanced datasets, this leads to critical issues like misleading accuracy metrics, poor generalization, and difficulty in discrimination [13].

Q4: Are simple resampling techniques like SMOTE sufficient for addressing these challenges? While resampling remains widely adopted, studies reveal that classifier performance differences can significantly exceed improvements from resampling alone [12]. For complex cases involving overlap, advanced methods like GOS that specifically target overlapping regions may be necessary [13].

Q5: What should I consider before choosing a solution for my S&I problem? A detailed data perspective analysis is essential. Before developing solutions, quantify the degree of imbalance and characterize internal dataset features and complexities, which are primary determinants of classification performance [12].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Poor Model Generalization on Small, Imbalanced Datasets

Issue Identification

- Symptom: High accuracy on majority classes but significant misclassification of minority classes.

- Error Example: Consistently failing to identify rare solute molecules or reaction outcomes in your experimental data.

Troubleshooting Steps

- Quantify Imbalance: Calculate your dataset's Imbalance Ratio (IR) and use complexity measures to understand the data structure [12] [14].

- Apply Advanced Oversampling: Use methods like

GOS(Generated Overlapping Samples) that generate synthetic samples from positive overlapping regions, improving feature expression for the minority class [13]. - Implement Data Augmentation: For small sample problems, employ generative models (VAE, GAN, Diffusion Models) to create new synthetic training samples [12] [14].

- Utilize Hybrid Approaches: Combine data-level and algorithm-level methods. For example, use

Cost-Sensitive LearningwithDeepSMOTEto make the model focus on the minority class [14].

Problem: Model Confusion Due to Significant Feature Overlap

Issue Identification

- Symptom: Low overall performance with consistent misclassification in specific feature space regions.

- Error Example: Inability to distinguish between structurally similar solute molecules with different properties.

Troubleshooting Steps

- Measure Overlap: Calculate the

overlapping degreemetric to quantify how much a positive sample contributes to the overlapping region [13]. - Apply Targeted Resampling: Use

GOSto identify positive overlapping samples and transform them using a matrix derived from all positive samples, preserving boundary information [13]. - Clean the Data: Apply combined cleaning and resampling algorithms like

CCR(Combined Cleaning and Resampling) to address noisy and borderline examples [14]. - Adjust Classification Strategy: Implement ensemble methods or cost-sensitive learning that impose higher penalties for minority class misclassification [13].

Key Imbalance Metrics and Performance

Table 1: Imbalance Measurement Metrics for Experimental Data Analysis

| Metric Name | Acronym | Primary Use Case | Key Principle |

|---|---|---|---|

| Imbalance Degree [14] | ID | Multi-class imbalance | Measures class imbalance extent |

| Likelihood-Ratio Imbalance Degree [14] | LRID | Multi-class imbalance | Based on likelihood-ratio test |

| Imbalance Factor [14] | IF | General classification | Simple scale for inter-class imbalance |

| Augmented R-value [14] | Augmented R-value | Problems with overlap | Addresses overlap and imbalance |

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Oversampling Methods

| Method Name | Type | Key Innovation | Reported Average Improvement (vs. Baselines) |

|---|---|---|---|

| GOS (Generated Overlapping Samples) [13] | Oversampling | Uses overlapping degree and transformation matrix | 3.2% Accuracy, 4.5% F1-score, 2.5% G-mean, 5.2% AUC |

| SMOTE [12] | Synthetic Oversampling | Generates synthetic minority samples | Widely adopted but limited for complex overlap [13] |

| ADASYN [13] | Adaptive Synthetic | Focuses on difficult minority samples | Baseline for comparison |

| Borderline-SMOTE [14] | Synthetic Oversampling | Focuses on borderline minority samples | Baseline for comparison |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: GOS (Generated Overlapping Samples) Method

Purpose: To handle imbalanced and overlapping data by generating samples from positive overlapping regions [13].

Step-by-Step Workflow:

- Calculate Overlapping Degree:

- For each positive sample, identify its

mnearest neighbors from the entire dataset. - Compute the ratio of negative samples among these

mneighbors. - This ratio represents the

overlapping degree, quantifying how much a positive sample contributes to the overlapping region [13].

- For each positive sample, identify its

Identify Positive Overlapping Samples:

- Select positive samples with an overlapping degree greater than a predefined threshold (e.g., >0.5).

- This step isolates samples most affected by class overlap [13].

Create Transformation Matrix:

- From the entire set of positive samples (

P), compute the covariance matrix. - Derive a transformation matrix that encapsulates the distribution information of all positive samples [13].

- From the entire set of positive samples (

Generate New Synthetic Samples:

- Apply the transformation matrix to the identified positive overlapping samples.

- This creates new positive samples that enhance feature expression in overlapping regions, aiding classifiers in learning clearer decision boundaries [13].

GOS Oversampling Workflow

Protocol 2: Systematic S&I Problem Analysis Framework

Purpose: A comprehensive approach to diagnose and address Small Sample & Imbalance problems [12].

Step-by-Step Workflow:

- Characterize Dataset Properties:

Select Appropriate Solutions:

- For conventional S&I: Consider resampling (SMOTE, ADASYN) or data augmentation (GAN, VAE) [12] [14].

- For complexity-based S&I: Apply methods specifically designed for overlap and noise (GOS, SMOTE-IPF, CCR) [13] [14].

- For extreme S&I: Utilize few-shot learning, transfer learning, or hybrid approaches [14].

Implement and Evaluate:

- Apply chosen methods, focusing on metrics beyond accuracy (F1-score, G-mean, AUC).

- Compare classifier performance with and without interventions to determine optimal strategy [12].

S&I Problem Analysis Framework

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents & Computational Tools

| Tool/Reagent Name | Type | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| GOS Algorithm [13] | Computational Method | Generates synthetic samples from overlapping regions to address imbalance and overlap |

| SMOTE & Variants [14] | Computational Method | Synthetic oversampling to balance class distribution quantitatively |

| Data Complexity Measures [14] | Analytical Framework | Quantifies dataset characteristics, including overlap, to guide solution selection |

| Cost-Sensitive Learning [13] | Algorithmic Approach | Assigns higher misclassification costs to minority classes, improving their detection |

| Generative Models (GAN/VAE) [14] | Data Augmentation | Creates new synthetic training samples to address small sample size problems |

| Transformation Matrix [13] | Mathematical Tool | Preserves essential boundary information when generating new samples in GOS |

| BRD-4592 | BRD-4592, CAS:2119598-24-0, MF:C17H15FN2O, MW:282.31 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Aspochalasin D | Aspochalasin D, MF:C24H35NO4, MW:401.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

FAQs: Flow Path Adsorption and False Readings

What are the common signs that my experiment is affected by flow path adsorption? You may be observing adsorption-related issues if you encounter a combination of the following: a sudden, unexplained decrease in signal intensity from one sample to the next; high background noise; a loss of expected resolution in your data (e.g., inability to distinguish distinct cell cycle phases); and inconsistent results when repeating the same experiment. A gradual decline in signal can indicate a build-up of material on the flow cell walls [15].

Which solute molecules are most susceptible to adsorption in flow systems? The risk is particularly high for hydrophobic molecules and certain functional groups. In microplastic analysis, the Nile Red dye itself can precipitate in aqueous media, forming aggregates that adhere to surfaces and cause false positives [16]. In electrochemical studies, nitrogen-containing contaminants (NOx) are ubiquitous and can adsorb onto catalyst surfaces, leading to false positive readings for nitrogen reduction [17]. Proteins and other biomolecules can also non-specifically bind to surfaces [15].

How does the choice of flow path material influence adsorption? The chemical composition of the flow path is critical. Materials with hydrophobic or highly charged surfaces can promote the non-specific binding of solute molecules, fluorochromes, and antibodies. This interaction reduces the concentration of the analyte in the sample stream and provides sites for the accumulation of contaminants that release spurious signals. Using materials that are inert to your specific solutes is essential [15].

What procedural steps can minimize false positives from contaminants? Rigorous quantification and control of contaminants are necessary. This involves:

- Quantifying Contaminants: Actively measure the concentration of key contaminants (like NOx) in your gas supplies and electrolytes, rather than just using scavengers [17].

- Using Proper Controls: Always include appropriate controls, such as unstained samples, isotype controls, and positive controls, to establish baselines and identify non-specific binding [18] [15].

- Purifying Stains: For methods like Nile Red staining for microplastics, ensure the dye is properly dissolved and consider techniques like pre-filtration or sonication to prevent dye aggregates from being counted as particles [16].

Troubleshooting Guide: Adsorption and Background Issues

| Problem | Possible Causes Related to Adsorption & Material | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| A Loss or Lack of Signal [19] [15] | - Analyte molecules (e.g., antibodies, solutes) adsorbing onto tubing or flow cell surfaces.- Clogged flow cell due to accumulated material.- Suboptimal scatter properties from poorly fixed/permeabilized cells adhering to surfaces. | - Use passivated surfaces or different tubing materials (e.g., PEEK, certain treated plastics).- Include carrier proteins (e.g., BSA) in buffers to block non-specific sites.- Follow optimized fixation/permeabilization protocols to prevent cell debris.- Unclog the system with 10% bleach followed by deionized water [15]. |

| High Background and/or Non-Specific Staining [19] [15] | - Non-specific binding of detection reagents to the flow path or cells.- Presence of dead cells or cellular debris that non-specifically bind dyes.- Undissolved fluorescent dye (e.g., Nile Red) forming aggregates detected as signal [16].- Fc receptors on cells binding antibodies non-specifically. | - Use viability dyes to gate out dead cells.- Ensure fluorescent dyes are fully dissolved and filtered.- Block cells with BSA or Fc receptor blocking reagents before staining.- Perform additional wash steps to remove unbound reagents. |

| False Positive Signals [16] [17] | - Contaminants in gases or electrolytes (e.g., NOx) adsorbing onto surfaces and being reduced/measured [17].- Fluorescent aggregates from precipitated dye being counted as target particles [16].- Incomplete removal of red blood cell debris creating background particles. | - Quantify contaminant levels in all gas and liquid supplies [17].- Use proper solvent systems and filtration to prevent dye precipitation [16].- Optimize sample preparation, including complete lysis and washing steps [15]. |

| Variability in Results From Day to Day [19] | - Inconsistent sample preparation leading to varying degrees of solute adhesion.- Gradual fouling or degradation of the flow path material over time.- Fluctuations in the purity of gases/solvents introducing varying contaminant levels [17]. | - Standardize and meticulously follow sample preparation protocols.- Implement a regular maintenance and cleaning schedule for the instrument flow path.- Use high-purity reagents and monitor for contaminant levels. |

Experimental Protocols for Identification and Mitigation

Protocol 1: Systematic Control for Contaminant-Driven False Positives

This protocol is adapted from rigorous electrochemical studies to ensure measured signals originate from the intended analyte [17].

- Quantification of Contaminants: Do not rely solely on scavengers. Actively measure the concentration of key contaminants (e.g., NOx, ammonia) in your gas supplies, electrolytes, and solvent systems using appropriate analytical methods before the experiment begins.

- Isotopic Validation: Where possible, use isotopically labeled starting materials (e.g., ¹âµNâ‚‚). The product (e.g., ¹âµNH₃) must be quantitatively analyzed and its production rate must match that from the natural isotope experiment.

- Comprehensive Controls: Run control experiments without the critical reactant (e.g., without Nâ‚‚) and with the experimental setup to establish the system's background signal. This helps identify signals originating from the setup itself or adsorbed contaminants.

Protocol 2: Mitigating Adsorption of Hydrophobic Solutes and Dyes

This protocol is crucial for fields like microplastic detection using Nile Red or handling any hydrophobic solute [16] [15].

- Solvent System Optimization: For hydrophobic dyes like Nile Red, use co-solvents (e.g., ethanol, DMSO) or surfactants to enhance dissolution and stability in aqueous media, preventing precipitation and adsorption.

- Sample Pre-treatment: Implement pre-filtration or sonication steps to break up and remove large aggregates that could otherwise adhere to surfaces or be counted as false particles.

- Surface Blocking: When working with proteins or biomolecules, prepare buffers containing inert proteins like Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) to block non-specific binding sites on the flow path and sample tubing.

- Direct Staining: Prefer direct antibody conjugates over biotin-streptavidin systems, as the latter can lead to high background from endogenous biotin, which can bind to surfaces [15].

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists key reagents used to prevent adsorption and ensure sample integrity in flow-based systems.

| Reagent / Material | Function in Preventing Adsorption & False Readings |

|---|---|

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) | Used as a blocking agent to passivate surfaces, reducing non-specific binding of proteins and antibodies to the flow path and sample vessels [15]. |

| Inert Flow Path Materials (e.g., PEEK) | Tubing and component materials chosen for their chemical inertness and low protein/solute binding properties to minimize analyte loss. |

| Fc Receptor Blocking Reagent | Blocks Fc receptors on cells to prevent non-specific antibody binding, a common source of high background in flow cytometry [15]. |

| Viability Dyes (e.g., PI, 7-AAD) | Allows for the identification and gating-out of dead cells, which are prone to non-specific staining and can contribute to background signal [15]. |

| Surfactants (e.g., Triton X-100) | Used in permeabilization buffers and to help solubilize hydrophobic compounds, preventing their aggregation and adhesion to surfaces [16] [15]. |

| High-Purity Gases & Solvents | Minimizes the introduction of chemical contaminants (e.g., NOx) that can adsorb to surfaces and react, generating false positive signals [17]. |

Workflow: Identifying and Resolving Surface-Induced False Readings

The following diagram illustrates a logical pathway for diagnosing and correcting issues related to material incompatibility and adsorption.

Pathway for Contaminant Identification in Electrochemical Analysis

This diagram details the specific verification pathway for identifying false positives from contaminants, as required in rigorous electrochemical studies such as nitrogen reduction research [17].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What are the most common data-related challenges in predictive modeling for drug discovery? The most common challenges stem from data quality, data integration, and technical sampling limitations. [20] Data often flows in from many disparate sources, each in a unique or unstructured format, making it difficult to merge into a coherent dataset. [20] Furthermore, sampling solute molecules in explicit aqueous environments using computational methods like Grand Canonical Monte Carlo (GCMC) often suffers from poor convergence due to low insertion probabilities of the solutes, which limits the quality and quantity of data obtained for modeling. [21]

2. How does poor data quality specifically impact predictive models? Poor data quality—marked by data entry errors, mismatched formats, outdated data, or a lack of standards—can lead to process inefficiency, dataset inaccuracies, and unreliable model output. [20] In computational chemistry, for example, a failure to adequately sample solute distributions can result in an inaccurate calculation of properties like hydration free energy, directly undermining the model's predictive value. [21]

3. What is a typical sign that my experimental data is insufficient for building a robust model? A key sign is model overfitting, where a model achieves high accuracy on training data but performs poorly on new, unseen data because it has memorized noise instead of learning general patterns. [22] In the context of solute sampling, a clear indicator is the poor convergence and low exchange probabilities of molecules in your simulations, meaning the system is not adequately exploring the possible configurations. [21]

4. Our organization struggles with integrating data from different instruments and teams. What are the best practices? Success requires a focus on data governance and robust data integration protocols. [20] This involves:

- Establishing a DataOps team to set up integration platforms and enforce data model standards. [20]

- Implementing data cleaning processes to standardize formats, eliminate duplicates, and fix errors. [20]

- Adopting a pilot-scale approach before full deployment to discover methodological flaws early. [20]

5. Are there computational methods to improve the sampling of solute molecules? Yes, advanced computational methods can significantly enhance sampling. One such method is the oscillating-excess chemical potential (oscillating-μex) Grand Canonical Monte Carlo-Molecular Dynamics (GCMC-MD) technique. [21] This iterative procedure involves GCMC of both solutes and water followed by MD, with the μex of both oscillated to achieve target concentrations. This method improves solute exchange probabilities and spatial distributions, leading to better convergence for calculating properties like hydration free energy. [21]

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Addressing Poor Data Convergence in Solute Sampling Simulations

Problem: During free energy calculations or solute distribution sampling, the simulation shows poor convergence, with low acceptance rates for solute insertion and deletion moves.

Explanation: In explicit solvent simulations within a grand canonical (GC) ensemble, the low probability of successfully inserting a solute molecule into a dense, aqueous environment is a fundamental challenge. This results in inadequate sampling of the solute's configuration space, making it difficult to obtain reliable thermodynamic averages. [21]

Solution: Implement an iterative Oscillating-μex GCMC-MD method. [21]

- Step 1: System Setup. Define a spherical simulation region (System A) where GCMC moves will be performed. This system should be immersed in a larger solvated environment (System B) to limit edge effects. [21]

- Step 2: Initialization. Set the initial excess chemical potential (μex) for solutes and water to zero for the first iteration. [21]

- Step 3: Iterative GCMC-MD Cycle. Run a cycle of GCMC sampling for both solutes and water, followed by a short MD simulation for conformational sampling.

- Step 4: Oscillate μex. After each iteration (or subset of iterations), adjust the μex of the solutes and water based on the deviation of their current concentrations in System A from the target concentration. If the concentration is too low, increase μex; if it is too high, decrease it. [21]

- Step 5: Achieve Convergence. As concentrations approach their targets, decrease the magnitude of the μex oscillations. The system is converged when the average μex stabilizes, providing an estimate for the hydration free energy at the target concentration. [21]

The following workflow diagram illustrates this iterative process:

Guide 2: Troubleshooting Predictive Model Failure After Deployment

Problem: A predictive model performs well during training and testing but fails to generate accurate predictions in a production environment.

Explanation: This is a common pitfall often caused by model overfitting or data drift—a mismatch between the data used for training and the data encountered in production. This can occur if the training data was not representative, was poorly prepared, or if real-world data patterns have changed over time. [22]

Solution: A systematic approach to data and model management.

- Step 1: Verify Data Preparation. Ensure that the data preprocessing (handling missing values, outliers, normalization) in the production pipeline exactly mirrors the training pipeline. Inconsistent processing is a frequent source of failure. [22]

- Step 2: Check for Overfitting. If you used an overly complex model, it may have memorized the training set. Re-evaluate the model using cross-validation and simpler algorithms. Techniques like regularization and feature selection are critical to prevent this. [22]

- Step 3: Monitor for Data and Model Drift. Implement continuous monitoring of input data distributions and model performance metrics. Establish a plan for periodic model retraining with new data to keep the model relevant as underlying patterns evolve. [22]

The tables below summarize key quantitative data and common pitfalls to aid in experimental planning and troubleshooting.

| Challenge | Impact | Recommended Mitigation |

|---|---|---|

| Data Quality [20] | Leads to process inefficiency and unreliable model output. | Implement data cleaning and validation processes to standardize formats and remove errors. [20] |

| Data Integration [20] | Hinders a unified view of data from different sources (e.g., CRM, ERP). | Establish robust data governance and use integration platforms to enforce standards. [20] |

| Inexperience / Skill Gaps [20] | Compounds data handling challenges and leads to errors. | Invest in constant training, outreach, and consider third-party consultants. [20] |

| User Adoption & Trust [20] | Limits the utilization and impact of predictive insights. | Demonstrate effectiveness, ensure model transparency, and manage expectations. [20] |

| Project Maintenance [20] | Models become outdated as data patterns change. | Establish feedback mechanisms and KPIs for model performance and maintenance. [20] |

Table 2: Researcher's Toolkit for Advanced Solute Sampling

| Item | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Grand Canonical Monte Carlo (GCMC) | A simulation technique that allows the number of particles in a system to fluctuate, enabling the sampling of solute and solvent concentrations by performing insertion and deletion moves. [21] |

| Molecular Dynamics (MD) | A computer simulation method for analyzing the physical movements of atoms and molecules over time, used for conformational sampling after GCMC moves. [21] |

| Excess Chemical Potential (μex) | The key thermodynamic quantity representing the free energy cost to insert a particle into the system. It is oscillated during the GCMC-MD procedure to drive sampling and achieve target concentrations. [21] |

| Hydration Free Energy (HFE) | The free energy change associated with the transfer of a solute molecule from an ideal gas state into solution. It is a critical property that can be approximated by the converged average μex in these simulations. [21] |

| Isoeugenol-d3 | Isoeugenol-d3, MF:C10H12O2, MW:167.22 g/mol |

| SARS-CoV-2-IN-95 | SARS-CoV-2-IN-95, MF:C29H36N4OS, MW:488.7 g/mol |

Experimental Protocol: Oscillating-μex GCMC-MD for Solute Sampling

Objective: To efficiently sample the distribution and calculate the hydration free energy of organic solute molecules in an explicit aqueous environment, overcoming the challenge of low insertion probabilities.

Methodology Details (Adapted from [21]):

System Definition:

- Create a primary simulation region, System A, which is a sphere of radius

rA. All GCMC moves (insertion, deletion, translation, rotation) are performed within this sphere. - Immerse System A within a larger system, System B, which has a radius

rB = rA + 5 Ã…and contains additional water molecules. This outer shell acts as a buffer to limit edge effects, such as solutes accumulating at the boundary of System A.

- Create a primary simulation region, System A, which is a sphere of radius

Initialization:

- Set the target concentration for water in System A to 55 M (bulk concentration).

- Set the target concentration for the solute(s). For standard state simulation (Scheme I), this is typically 1 M for a single solute. For a mixture (Scheme II), use lower concentrations (e.g., 0.25 M for each solute).

- Initialize the excess chemical potential (μex) for all species (water and solutes) to 0.

Iterative Oscillating-μex GCMC-MD Procedure: The following diagram outlines the logical flow of the complete experimental protocol, integrating both computational methods and analysis steps.

- Analysis:

- Upon convergence, the average value of the oscillated μex for a solute over the final iterations provides an approximation of its hydration free energy at the specified target concentration and standard state. [21]

- The spatial distribution of the solutes within the system can be analyzed to understand solvation behavior and, in the case of protein systems, binding site preferences.

Modern Workflows: Computational and Experimental Sampling Techniques

Computational Workflows for Solvent Selection and Solubility Prediction

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the main computational approaches for predicting solubility? Two primary models are used. Implicit solvation models treat the solvent as a continuous, polarizable medium characterized by its dielectric constant, with the solute in a cavity. Methods like the Polarizable Continuum Model (PCM) are used to calculate solvation free energy (∆Gsolv). In contrast, explicit solvation models simulate a specific number of solvent molecules around the solute, providing a more detailed, atomistic picture of solute-solvent interactions, which is crucial for understanding specific effects like hydrogen bonding [23].

FAQ 2: My simulations show poor solute sampling convergence. What is wrong? Poor convergence in grand canonical (GC) ensemble simulations is a known challenge caused by low acceptance probabilities for solute insertion moves in an explicit bulk solvent environment [21]. This is often because the supplied excess chemical potential (μex) does not provide sufficient driving force to overcome the energy barrier for inserting a solute molecule into the system. Advanced iterative methods, such as oscillating-μex GCMC-MD, have been developed to address this specific issue [21].

FAQ 3: How can Machine Learning (ML) streamline solvent selection?

ML models offer a data-driven alternative to traditional methods. They can predict solubility directly from molecular structures, bypassing the need for empirical parameters. For instance, the fastsolv model predicts temperature-dependent solubility across various organic solvents, while Covestro's "Solvent Recommender" uses an ensemble of neural networks to rank solvents based on predicted activity coefficients, helping chemists explore over 70 solvents instead of the usual 5-10 [24] [25].

FAQ 4: What is the key difference between Hansen Solubility Parameters (HSP) and Hildebrand parameters? The Hildebrand parameter (δ) is a single value representing the cohesive energy density, best suited for non-polar molecules. HSP improves upon this by dividing solubility into three components: dispersion forces (δd), dipole-dipole interactions (δp), and hydrogen bonding (δh). This three-parameter model provides a more accurate prediction for polar and hydrogen-bonding molecules by defining a "Hansen sphere" in 3D space where compatible solvents reside [24].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Poor Solute Sampling in Grand Canonical Monte Carlo (GCMC) Simulations

Problem: In GCMC simulations with explicit solvent, the concentration of solute molecules fails to reach the target value, indicated by poor spatial distribution and low exchange probabilities [21].

Solution: Implement an Oscillating-μex GCMC-MD Workflow This iterative procedure combines GCMC and Molecular Dynamics (MD) to improve convergence [21].

Initialization:

- Define your system (System A) within a spherical boundary of radius rA, immersed in a larger solvated environment (System B) to minimize edge effects.

- Set the initial excess chemical potential (μex) for both solute and water to zero.

Iteration Cycle:

- Step A - GCMC Sampling: Perform Grand Canonical Monte Carlo moves for both solute and water molecules. The move probabilities are governed by the Metropolis criteria based on the current μex and the interaction energy (ΔE).

- Step B - MD Simulation: Run a short molecular dynamics simulation to allow for conformational sampling of the solutes and configurational sampling of the entire system.

- Step C - Adjust μex: Compare the current concentration of solutes and water in the system to their target concentrations (n̅). Systematically oscillate the μex values for the next iteration based on this deviation. As concentrations approach the target, decrease the oscillation width.

Convergence: The process is converged when the average μex of the solutes approximates their hydration free energy (HFE) at the specified target concentration [21].

Issue 2: Inaccurate Predictions for Small, Polar Molecules with HSP

Problem: Traditional solubility parameters like HSP struggle to accurately predict solubility for very small, strongly hydrogen-bonding molecules like water and methanol [24].

Solution: Employ Machine Learning or Corrected Parameters

- Use Corrected Empirical Parameters: For specific solvents like methanol, modified HSP values can be used (e.g., (δd, δp, δh) = (14.7, 5, 10) instead of the standard (14.5, 12.3, 22.3)) to account for self-association behavior [24].

- Switch to a Data-Driven ML Model: Machine learning models like

fastsolvdo not rely on fixed empirical parameters. They are trained on large experimental datasets (e.g., BigSolDB) and can capture complex interactions that challenge traditional models, providing more accurate solubility predictions for problematic solutes [24]. - Consider an Extended Model: For higher accuracy, more complex models like the 6-parameter MOSCED can be evaluated, though they require significantly more input data [24].

Experimental & Computational Protocols

Protocol 1: Machine Learning Workflow for Identifying Organic Co-Solvents

This workflow is designed to find co-solvents that increase the solubility of hydrophobic molecules in aqueous mixtures [26].

- Predict Water Miscibility: Screen potential co-solvents, retaining only those predicted to be miscible in water.

- Feature Engineering: For the target solute and the miscible co-solvents, generate molecular descriptors (e.g., using fingerprinting or libraries like mordred).

- Model Prediction:

- Use a pre-trained ML model (e.g., Light Gradient Boosting Machine - LGBM) on the organic solubility dataset (e.g., BigSolDB) to predict the solubility of your target molecule in each co-solvent.

- The model output is typically log(x) or log(S).

- Rank and Validate: Rank the co-solvents based on the predicted solubility. The highest-ranking solvents are the best candidates for experimental validation [26].

Protocol 2: Determining Hansen Solubility Parameters (HSP) for a Novel Polymer

This classic experimental method triangulates the solubility space of a material [24].

- Select Test Solvents: Choose a diverse set of 20-30 solvents with known HSP values.

- Solubility Testing: Prepare mixtures of the polymer in each solvent. Qualitatively score each test as "soluble," "partially soluble," or "insoluble."

- Data Fitting: Plot the "soluble" and "insoluble" solvents in the 3D Hansen space (δd, δp, δh). Use software to fit the smallest possible sphere (the "Hansen sphere") that encompasses most of the "soluble" solvents. The center of this sphere (δd, δp, δh) are the HSP for your polymer, and its radius is R0.

- Predictive Use: Any solvent (or solvent mixture, calculated via volume-weighted averages) whose HSP coordinates lie within this sphere is predicted to dissolve the polymer.

Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 1: Key Reagents and Datasets for Solubility Modeling

| Item Name | Type | Function / Description | Key Application / Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| BigSolDB [24] [26] | Dataset | Large experimental dataset containing 54,273 solubility measurements for 830 molecules and 138 solvents. | Training and benchmarking data for ML models like fastsolv. |

| AqSolDB [26] | Dataset | A curated dataset for aqueous solubility. | Used for training ML models specifically for water solubility prediction. |

| Hansen Parameters(δd, δp, δh) [24] | Empirical Parameter | Three-parameter model for predicting solubility based on "like dissolves like". | Popular in polymer science for predicting solvent compatibility for coatings, inks, and plastics. |

| Hildebrand Parameter (δ) [24] | Empirical Parameter | Single-parameter model of cohesive energy density. | Best suited for non-polar and slightly polar molecules where hydrogen bonding is not significant. |

| fastsolv Model [24] | Machine Learning Model | A deep-learning model that predicts log10(Solubility) across temperatures and organic solvents. | Provides quantitative solubility predictions and uncertainty estimation; accessible via platforms like Rowan. |

| Solvent Recommender [25] | Machine Learning Tool | An ensemble of message-passing neural networks that ranks solvents by predicted activity coefficient. | Used in industry (e.g., Covestro) for comparative solvent screening to accelerate R&D. |

Table 2: Comparison of Solubility Prediction Methods

| Method | Core Principle | Key Output | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hildebrand Parameter [24] | Cohesive Energy Density | Single parameter (δ) | Simple, easy to calculate for many molecules. | Not suitable for polar or hydrogen-bonding molecules. |

| Hansen Solubility Parameters (HSP) [24] | Dispersion, Polarity, H-bonding | Three parameters (δd, δp, δh) and radius R0. | More accurate for polar molecules; can predict solvent mixtures. | Struggles with very small, polar molecules (e.g., water); requires experimental data fitting. |

| Machine Learning (e.g., fastsolv) [24] [26] | Data-driven pattern recognition | Quantitative solubility (e.g., log10(S)) | High accuracy, predicts temperature dependence, works for unseen molecules. | "Black box" nature; requires large, high-quality training datasets. |

| Oscillating-μex GCMC-MD [21] | Statistical Mechanics / Sampling | Hydration Free Energy (HFE) and spatial distributions. | Addresses poor sampling in explicit solvent simulations; good for occluded binding sites. | Computationally expensive; complex setup and convergence monitoring. |

Leveraging Machine Learning Models like FastSolv for Accurate Solubility Forecasting

Your FastSolv Troubleshooting Guide

This guide helps you diagnose and resolve common issues when using machine learning models like FastSolv for solubility forecasting, with a special focus on challenges related to poor molecular sampling.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What should I do if my solubility predictions seem inaccurate or unstable? This is often a symptom of poor sampling of the solute molecule's conformational space. The model's accuracy depends on the representation of the molecule's diverse 3D shapes in solution.

- Diagnosis: The issue may be with the input molecule itself. Complex, flexible molecules with many rotatable bonds can exist in numerous conformations. If the model's internal sampling doesn't adequately capture this diversity, predictions can be unreliable.

- Solution: While you cannot change the model's internal sampling directly, you can pre-process your solute. Consider generating a set of diverse low-energy conformers for your solute and running predictions for each. Analyzing the range of predicted solubilities can provide insight into the uncertainty stemming from conformational flexibility [27].

Q2: Why do predictions for charge-changing molecules present greater challenges? Sampling challenges are more likely to occur for charge-changing molecules because the alchemical transformations involved in the prediction can involve slow degrees of freedom [27].

- Diagnosis: The energy landscape of charged systems is complex. The process of turning atomic charges on/off can lead to significant reorganization of the surrounding solvent molecules and the solute itself. If the simulation doesn't fully sample these slow rearrangements, the free energy estimate (and thus the solubility prediction) will be inaccurate [27].

- Solution: Be aware that predictions for molecules with ionizable groups or strong permanent dipoles may have higher inherent uncertainty. Cross-validate critical results with alternative methods or experimental data if possible.

Q3: My solute is large and flexible. Are there known sampling limitations? Yes, broad, flexible interfaces and complex solute-solvent interaction networks are known to cause sampling problems in free energy calculations [27].

- Diagnosis: Large, flexible molecules have many slow degrees of freedom. The time required for the molecule to transition between different conformational states may exceed what is feasible in a standard simulation, leading to inadequate sampling [27].

- Solution: For such molecules, the predictions should be treated with caution. The use of enhanced sampling protocols, similar to the Alchemical Replica Exchange (AREX) methods mentioned in advanced sampling literature, can help, but these are typically implemented at the level of the simulation engine itself [27].

Q4: How can I trust a prediction if I don't know the model's uncertainty? The fastsolv model provides a standard deviation for its predictions, which is crucial for assessing reliability [28].

- Diagnosis: A large predicted standard deviation is a direct indicator of high uncertainty in the forecast. This could be due to factors like the solute being outside the model's training data domain or inherent unpredictability (aleatoric uncertainty) [29] [28].

- Solution: Always check the standard deviation or uncertainty metrics accompanying your prediction. A large uncertainty value is a warning that the prediction may be unreliable for critical decision-making [28].

The Researcher's Toolkit

The following reagents and computational resources are essential for effective solubility forecasting.

| Item | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| FastSolv Model | A machine learning model trained on 54,273 experimental measurements to predict organic solubility across a temperature range [29] [28]. |

| Solute & Solvent SMILES | Simplified Molecular-Input Line-Entry System strings; the required input format for FastSolv to define molecular structures [29]. |

| Common Solvents (e.g., Acetone, Water) | Pre-defined solvents in platforms like Rowan allow for quick, standardized solubility screening [30] [28]. |

| Enhanced Sampling Software (e.g., Perses) | An open-source package for relative free energy calculations; useful for researching and overcoming sampling challenges in complex systems [27]. |

| Plecanatide acetate | Plecanatide acetate, MF:C67H108N18O28S4, MW:1741.9 g/mol |

| SCH-202676 | SCH-202676, MF:C15H13N3S, MW:267.4 g/mol |

FastSolv Workflow and Sampling Challenges

The diagram below illustrates the solubility prediction workflow and highlights where sampling challenges for solute molecules typically arise.

Experimental Data and Protocols

| Model | Training Data Size | Key Solvent | Prediction Output | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FastSolv | 54,273 measurements [28] | Organic solvents [29] | Log solubility & std deviation [28] | Sampling limits for flexible/charged molecules [27] |

| Kingfisher | 10,043 measurements [28] | Water (neutral pH) | Log solubility at 25°C [28] | Restricted to aqueous solubility |

Protocol: Investigating Sampling Adequacy for a Solute

1. Objective To assess the reliability of a FastSolv solubility prediction by probing the conformational sampling of a flexible solute molecule.

2. Materials

- SMILES string of the target solute.

- Access to the FastSolv model (via web interface or local installation) [29].

- Computational chemistry software capable of molecular mechanics calculations and conformer generation (e.g., RDKit, Open Babel).

3. Procedure

- Step 1: Generate Multiple Conformers Using your computational chemistry software, generate an ensemble of low-energy conformers for the solute molecule. Ensure the generation method (e.g., systematic search, stochastic) produces a diverse set of structures that represent the molecule's flexibility.

Step 2: Run Parallel Predictions Submit each unique conformer from your ensemble to the FastSolv model as a separate solute SMILES string. Use the same solvent and temperature conditions for all predictions to isolate the variable of conformation.

Step 3: Analyze Results Compile all predicted solubility values and their associated standard deviations. Calculate the mean, range, and standard deviation of the predictions across the conformer ensemble.

- A wide range of predicted solubilities indicates that the result is highly sensitive to conformation, signaling a potential sampling problem.

- A narrow range increases confidence that the prediction is robust despite the solute's flexibility.

4. Interpretation This protocol provides a practical estimate of the uncertainty in the solubility prediction arising specifically from the conformational degrees of freedom of the solute. If the range of predictions is larger than your required accuracy threshold, the result from a single conformation should not be trusted for critical applications.

Bayesian Optimization with Structured Sampling for Efficient Parameter Space Exploration

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the primary advantage of using structured sampling in Bayesian Optimization for solute studies? Structured initial sampling methods, such as Latin Hypercube Sampling (LHS), determine the quality and coverage of the parameter space. This directly influences the predictions of the surrogate model. Poor sampling can lead to uneven coverage that overlooks crucial regions and weakens the initial model, significantly hindering the overall performance of the subsequent optimization. Using structured sampling is crucial when dealing with the complex energy landscapes of solute molecules to ensure the initial surrogate model is representative [31].

My BO is converging slowly in high-dimensional solute parameter space. What structured sampling strategy should I consider? For high-dimensional problems, consider strategies that efficiently cover the space. Latin Hypercube Sampling (LHS) is a popular choice as it ensures that projections of the sample points onto each parameter are uniformly distributed. This is more space-filling than simple random sampling and provides better initial coverage for building the Gaussian Process model, which is particularly beneficial when the computational or experimental budget is limited [31].

How can I handle operational constraints during Bayesian exploration of solute systems? You can use an adaptation of Bayesian optimization that incorporates operational constraints directly into the acquisition function. For example, the Constrained Proximal Bayesian Exploration (CPBE) method multiplies the standard acquisition function by a probability factor that the candidate point will satisfy all specified constraints. This biases the search away from regions of the parameter space that are not likely to satisfy operational limits, such as solvent concentration thresholds or equipment tolerances [32].

Can Bayesian Optimization guide the search in large, discrete molecular spaces? Yes, advanced methods are being developed for this purpose. One approach for navigating vast chemical spaces uses multi-level Bayesian optimization with hierarchical coarse-graining. This method compresses the chemical space into varying levels of resolution, balancing combinatorial complexity and chemical detail. Bayesian optimization is then performed within these smoothed latent representations to efficiently identify promising candidate molecules [33].

Troubleshooting Guides

Poor Initial Surrogate Model Performance

Symptoms

- The optimization process fails to find promising regions after many iterations.

- The model's predictions have high uncertainty across most of the parameter space.

- Performance is highly sensitive to the initial set of randomly chosen points.

Possible Causes and Solutions

- Cause: Inadequate coverage of parameter space.

- Solution: Replace random sampling with a structured Design of Experiments (DoE) approach. Use Latin Hypercube Sampling (LHS) to generate initial points that are space-filling and ensure all regions of the parameter space are probed [31].

- Cause: Model does not capture relevant length scales.

- Solution: Use a Gaussian Process model with Automatic Relevance Determination (ARD). ARD assigns an independent length-scale hyperparameter to each input parameter, allowing the model to adapt to the different sensitivities of the objective function to each parameter, which is common in solute-solvent interactions [32].

Handling Expensive and Noisy Evaluations

Symptoms

- The optimization process is prohibitively slow due to the cost of individual experiments or simulations.

- The algorithm appears to "jump" erratically due to noisy measurements of solute properties.

Possible Causes and Solutions

- Cause: High cost of evaluating objective function.

- Solution: Leverage multi-fidelity or coarse-grained models where possible. For instance, use faster, less accurate computational models (e.g., coarse-grained molecular dynamics or implicit solvent models) to guide the optimization before committing resources to high-fidelity experiments or all-atom simulations [33] [34].

- Cause: Noisy measurements of the objective function.

- Solution: Ensure your Gaussian Process surrogate model is configured to account for noise in the observations. This typically involves including a noise term (often referred to as a "nugget") in the GP kernel, which prevents the model from overfitting to noisy data points [31].

Experimental Protocols for Structured Sampling

Protocol 1: Initial Design with Latin Hypercube Sampling (LHS)

Objective: To generate an initial set of sample points that provide maximum coverage of the multi-dimensional parameter space before beginning the Bayesian Optimization loop.

Materials:

- Computer with a scientific computing environment (e.g., Python, R).

- Bayesian optimization software package (see Table 3).

Method:

- Define Parameter Bounds: For each of the

dparameters to be optimized (e.g., solute concentration, temperature, pH), define the minimum and maximum values of the feasible region. - Specify Sample Size: Determine the number of initial samples

n. A common rule of thumb is to usen = 10 * d, but this can be adjusted based on the complexity of the problem and the evaluation budget [31]. - Generate LHS Design:

- Divide the range of each parameter into

nintervals of equal probability. - Randomly select one value from each interval for each parameter.

- Randomly permute the order of these values for each parameter so that the combinations are random. This creates an

n x dmatrix where each row is a sample point.

- Divide the range of each parameter into

- Evaluate Objective Function: Run your experiment or simulation at each of the

nsample points to collect the corresponding response data (e.g., reaction yield, binding affinity). - Initialize BO: Use the collected

(input, output)data pairs to build the initial Gaussian Process surrogate model and begin the iterative Bayesian Optimization cycle.

Protocol 2: Oscillating-Chemical Potential GCMC-MD for Solute Sampling

Objective: To improve the convergence and sampling of solute molecules in an explicit aqueous environment, a common challenge in molecular simulations.

Materials:

- Molecular dynamics simulation software (e.g., GROMACS, AMBER).

- Grand Canonical Monte Carlo (GCMC) simulation package or module.

- Force field parameters for the solute and solvent (water) molecules.

Method:

- System Setup: Define the simulation system, including a spherical region (System A) where GCMC moves will be performed, immersed in a larger solvated environment (System B) to limit edge effects [21].

- Set Target Concentrations: Define the target concentration for the solute (e.g., 1 M for standard state) and for the water (55 M) in System A.

- Iterative GCMC-MD Cycle:

- GCMC Step: Perform Grand Canonical Monte Carlo moves on both the solute and water molecules within System A. The goal is to insert or delete molecules to achieve the target concentrations.

- MD Step: Run a short molecular dynamics simulation to allow for conformational sampling of the solutes and configurational relaxation of the entire system.

- Oscillate Chemical Potential: Based on the deviation of the current solute/water concentrations from their targets, systematically oscillate the excess chemical potential (

μex) values for the subsequent GCMC step. This oscillation helps drive the solute exchange and improve spatial distribution sampling [21].

- Convergence Check: Periodically, the oscillation width of the

μexvalues is decreased. Convergence is achieved when the concentrations stabilize at their targets and the averageμexfor the solute approximates its hydration free energy under the specified conditions [21].

Table 1: Comparison of Initial Sampling Strategies

| Sampling Strategy | Key Principle | Advantages | Best Used For |

|---|---|---|---|

| Random Sampling | Points are selected entirely at random from a uniform distribution. | Simple to implement; no assumptions about the function. | Very limited budgets; establishing a baseline performance. |