Overcoming Nonlinearities in MSD Plots: A Practical Guide for Molecular Dynamics Researchers

Nonlinearities in Mean Squared Displacement (MSD) plots present a significant challenge in molecular dynamics simulations, potentially leading to inaccurate diffusion coefficients and misinterpretation of molecular behavior.

Overcoming Nonlinearities in MSD Plots: A Practical Guide for Molecular Dynamics Researchers

Abstract

Nonlinearities in Mean Squared Displacement (MSD) plots present a significant challenge in molecular dynamics simulations, potentially leading to inaccurate diffusion coefficients and misinterpretation of molecular behavior. This comprehensive guide addresses this critical issue by first exploring the fundamental origins of nonlinear MSD, including heterogeneous diffusion, experimental artifacts, and non-Brownian motion. It then details advanced methodological approaches for analysis, such as changepoint detection algorithms and machine learning techniques, as evidenced by recent benchmarking studies. The article provides practical troubleshooting protocols for optimizing simulation parameters and trajectory analysis, drawing from cutting-edge research in polymer electrolytes and drug development. Finally, it establishes rigorous validation frameworks using community challenges and automated workflows to ensure result reliability. Designed for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this resource synthesizes the latest advances to transform nonlinear MSD challenges into opportunities for deeper molecular insights.

Understanding the Roots: What Causes Nonlinearities in Your MSD Plots

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. Why is my Mean Squared Displacement (MSD) plot nonlinear, and what does it indicate? A nonlinear MSD plot typically indicates that the dynamics of your biomolecular system are not purely diffusive. This is common and can be caused by several factors, including anisotropic diffusion (motion that is direction-dependent), confined diffusion (where particles are trapped in a sub-region), directed motion (such as active transport), or the presence of crossed-over particle trajectories due to periodic boundary conditions. These conditions violate the assumption of simple, unconfined Brownian motion, leading to a nonlinear relationship between MSD and time [1].

2. How can I resolve artifacts in my MSD plot caused by periodic boundary conditions?

Artifacts from periodic boundary conditions can be mitigated by using the cluster and nojump options in the trjconv tool. The following protocol ensures your entire molecule, like a micelle, remains intact and uncrossed during analysis [1]:

- Step 1: Use

gmx trjconvwith the-pbc clusterflag on the first frame of your trajectory to center your complex. - Step 2: Use

gmx gromppto generate a new.tprfile based on the clustered output. - Step 3: Use

gmx trjconvagain with the-pbc nojumpflag and the new.tprfile to process the entire trajectory.

3. My system is fully formed, but the MSD shows huge, unexplained fluctuations. What is wrong? This is a classic sign that your aggregate (e.g., a micelle or protein complex) is being split across the periodic boundary. Without corrective clustering, parts of your molecule may be placed on opposite sides of the simulation box, leading to incorrect distance calculations and erratic MSD values. The clustering protocol mentioned in FAQ #2 is essential to correct this [1].

| Symptom | Potential Source | Diagnostic Method | Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| MSD curve plateaus or has a negative slope | Confined Diffusion | Visualize the trajectory to check if particles are trapped within a sub-volume. Plot the radius of gyration to see if it remains constant. | Ensure the system is properly solvated and that no artificial barriers are present in the force field. |

| MSD curve is convex or shows super-diffusion | Directed Motion / Active Transport | Plot the velocity autocorrelation function. Analyze individual particle trajectories for persistent directional movement. | Investigate potential driven processes in your system, such as applied forces or active motor proteins. |

| Large, irregular fluctuations in MSD values | Trajectory Cross-over from PBCs | Use visualization software (e.g., VMD, Chimera) to visually inspect the trajectory and confirm molecules are split across box boundaries [1]. | Apply the trajectory clustering protocol using gmx trjconv -pbc cluster and gmx trjconv -pbc nojump [1]. |

| MSD is anisotropic (varies by direction) | Anisotropic Environment | Calculate the MSD separately for the x, y, and z dimensions. A significant difference indicates anisotropic dynamics. | Common in membrane systems; ensure analysis accounts for the layered structure. Check if the simulation box is appropriately sized. |

Experimental Protocol: Correcting Trajectories for MSD Analysis

Objective: To preprocess a molecular dynamics trajectory to eliminate artificial nonlinearities introduced by periodic boundary conditions before calculating the Mean Squared Displacement (MSD).

Materials:

- Input trajectory file (e.g.,

a.xtc) - Input topology file (e.g.,

a.tpr) - Input parameters file (e.g.,

a.mdp) - GROMACS installation (versions 2016-2024 confirmed compatible) [1]

Method:

- Cluster the First Frame: Center the molecular aggregate in the simulation box using the first frame as a reference.

- Generate a New Topology File: Create a new run input file based on the recently clustered structure.

- Process the Full Trajectory: Apply the "no-jump" correction to the entire trajectory using the new topology to prevent molecules from crossing periodic boundaries.

The resulting

a_cluster.xtcfile is now suitable for accurate MSD analysis [1].

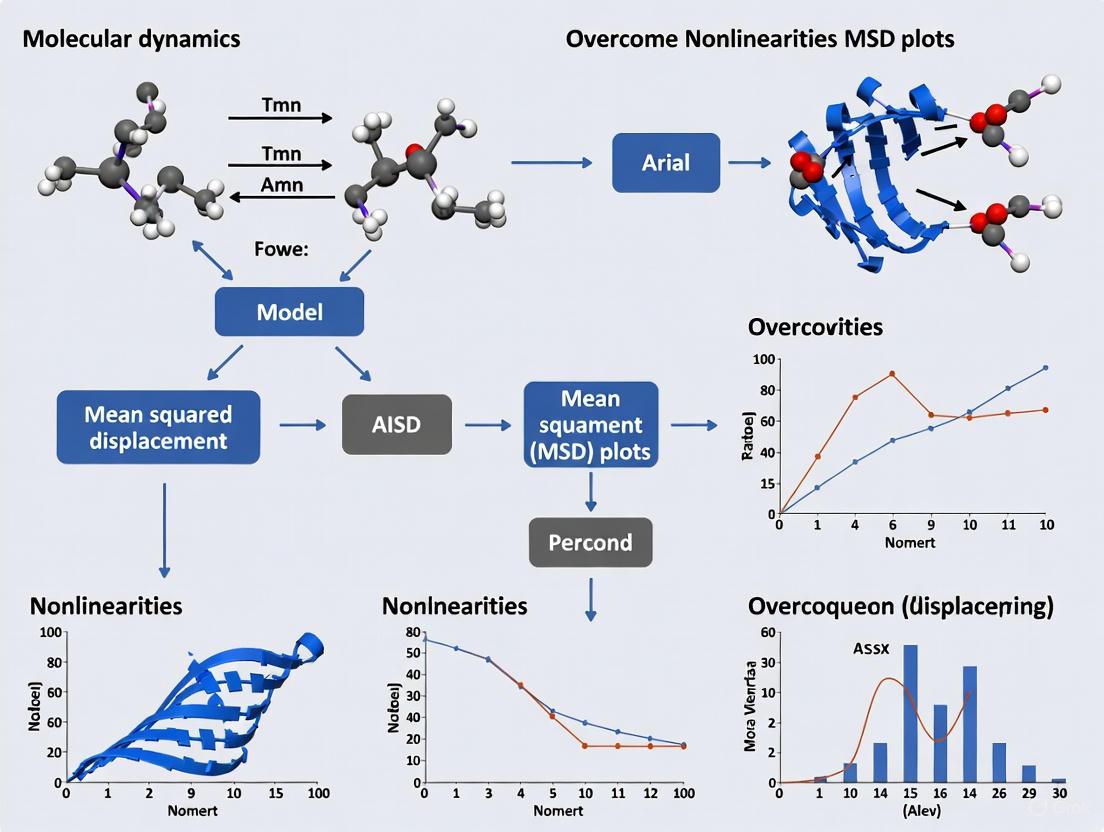

Visualization: Workflow for MSD Analysis

Diagram Title: MSD Analysis and Troubleshooting Workflow

Diagram Title: Common Nonlinear MSD Signatures

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Software | Function in Analysis |

|---|---|

| GROMACS (gmx trjconv) | A core MD simulation suite; its trjconv module is used for trajectory correction (cluster, nojump) and format conversion [1]. |

| VMD | A molecular visualization program for displaying, animating, and analyzing large biomolecular systems. Essential for visually diagnosing trajectory issues [1]. |

| Chimera | A full-featured, Python-based visualization program that can read GROMACS trajectories and is useful for structural analysis [1]. |

| Grace | A WYSIWYG 2D plotting tool, often used to graph data from GROMACS-generated .xvg files, such as MSD plots [1]. |

| Matplotlib | A popular Python library for creating static, animated, and interactive visualizations, commonly used for custom plotting of MSD data [1]. |

| Mal-PEG4-Lys(t-Boc)-NH-m-PEG24 | Mal-PEG4-Lys(t-Boc)-NH-m-PEG24, MF:C78H147N5O35, MW:1715.0 g/mol |

| Montelukast dicyclohexylamine | Montelukast dicyclohexylamine, MF:C47H59ClN2O3S, MW:767.5 g/mol |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

My MSD plots show clear curvature or plateaus, suggesting heterogeneous motion. What is the first thing I should check? First, verify that your trajectories are sufficiently long. Short trajectories can produce nonlinear MSD plots that are artifacts of limited sampling rather than true heterogeneous diffusion. For reliable characterization of anomalous diffusion, trajectories should span at least two orders of magnitude in time lags [2].

How can I distinguish between true anomalous diffusion and transient confinement within a single trajectory? Traditional MSD analysis can create ambiguity between a particle's inherent anomalous diffusion and nonlinearity caused by motion constraints [3]. To distinguish them, employ analysis methods that are more sensitive to transient states. The distribution of displacements, angles, or velocities within a trajectory can reveal heterogeneities that are masked in the ensemble-averaged MSD [2]. Hidden Markov Models (HMMs) are also particularly effective for identifying different diffusional states and their switching kinetics [2].

My single-particle tracking data in a 3D hydrogel is very short and noisy. What analysis methods are robust under these conditions? For short, noisy trajectories, machine learning (ML) classification methods often outperform traditional analyses. ML approaches, from random forest to deep neural networks, can identify motion patterns from predefined or automatically learned features of the trajectory, demonstrating good accuracy even with limited data [2]. Alternatively, active-feedback tracking methods like 3D-SMART can be used to generate the long, highly-sampled trajectories needed for conventional analysis [4].

Why do my molecular dynamics simulations of a simple diffusive process yield inconsistent results for diffusion coefficients? Classical Molecular Dynamics is a deterministic yet chaotic system. Extreme sensitivity to initial conditions means that even with perfect force fields, one-off simulations are not reproducible in a detailed sense. To obtain reliable and statistically meaningful results, you must use ensemble methods—running a sufficiently large number of replicas with different initial conditions—from which robust average properties and their uncertainties can be extracted [5].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Nonlinear or Curved MSD Plots

Symptoms: The Mean Squared Displacement (MSD) plot as a function of time lag (Ï„) is not linear on a log-log scale, showing curvature, plateaus, or other deviations from a straight line.

Potential Causes and Solutions:

| Cause | Diagnostic Check | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Short Trajectories | Check trajectory length. MSD curves become unreliable at long time lags (n > N/4) [2]. | Use the initial slope of the MSD (first 4-5 points) to estimate a short-term diffusion coefficient. Prioritize obtaining longer trajectories. |

| True Anomalous Diffusion | Fit MSD with a power law, MSD(τ) ~ τ^α. An exponent α ≠1 indicates anomalous diffusion [2]. | Use change-point detection algorithms or Hidden Markov Models (HMMs) to segment the trajectory into states with different α or D values [3] [2]. |

| Transient Confinement | Analyze the distribution of step sizes or angles. Confinement often leads to a high frequency of back-and-forth motion [2]. | Apply methods like the moment scaling spectrum (MSS) or machine learning classifiers that are sensitive to local motion patterns rather than global averages. |

| Experimental Noise | Plot the MSD at the shortest time lag. A high y-intercept often indicates significant localization error. | Use analysis frameworks that explicitly account for and correct localization uncertainty in the model [2]. |

Problem 2: Inconsistent Results from Molecular Dynamics Simulations

Symptoms: Simulations of the same system, but with slightly different initial conditions (e.g., random seed), produce different values for calculated properties like diffusion coefficients or binding free energies.

Potential Causes and Solutions:

| Cause | Diagnostic Check | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Chaotic Dynamics | Run 10-20 replicas with different random seeds and calculate the standard deviation of your property of interest. A large variance confirms sensitivity. | Implement a proper ensemble simulation approach. Run a large number of replicas (dozens to hundreds) to build reliable statistics and quantify uncertainty [5]. |

| Insufficient Sampling | Check if the property of interest has converged over the simulation time. | Extend simulation time or use enhanced sampling techniques to overcome energy barriers and sample phase space more effectively [6]. |

| Systematic Force Field Errors | Compare simulated properties with known experimental data. | Re-parameterize or select a more accurate force field. Be aware that different force fields can bias secondary structure formation [5]. |

Quantitative Data Tables

Table 1: Common Motion Types and Their MSD Characteristics

| Motion Type | MSD(τ) Equation | Anomalous Exponent (α) | Typical Physical Scenario |

|---|---|---|---|

| Immobile | Constant | ~ 0 | Particle tethered or tightly bound. |

| Brownian (Free Diffusion) | MSD(τ) = 2νDτ | α ≈ 1 | Unobstructed random walk in ν dimensions. |

| Subdiffusion | MSD(τ) = 2νDᵅτᵅ | α < 1 | Motion in a crowded or viscoelastic environment [2]. |

| Superdiffusion | MSD(τ) = 2νDᵅτᵅ | α > 1 | Active transport with a directional component [2]. |

| Confined | MSD(Ï„) = L²/3 (1 - Aâ‚exp(-Aâ‚‚Ï„/L²)) | α → 0 at long Ï„ | Particle trapped in a cage or microdomain [2]. |

| Method Class | Key Principle | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| MSD Analysis | Fits mean-squared displacement vs. time lag [2]. | Intuitive; well-established fitting models. | Low accuracy for short trajectories; masks heterogeneity. |

| Change-Point Detection | Identifies points where motion parameters change [3]. | Directly segments trajectories; reveals kinetics. | Performance depends on model choice and trajectory length. |

| Hidden Markov Models (HMM) | Models trajectory as a sequence of hidden states [2]. | Infers state populations and transition probabilities. | Requires pre-defining the number of states; can struggle with non-Brownian motion. |

| Machine Learning (ML) | Classifies motion based on trajectory features [2]. | High accuracy for short/noisy tracks; model-free options. | Can be a "black box"; requires training data; computationally intensive. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Detecting Motion Changes in Single-Particle Trajectories using Change-Point Analysis

This methodology is derived from benchmarks established by the 2nd Anomalous Diffusion (AnDi) Challenge [3].

- Trajectory Acquisition: Obtain single-particle trajectories via live-cell single-molecule imaging and tracking. Ensure a high signal-to-noise ratio and localization precision to minimize artifacts.

- Data Preprocessing: Filter trajectories based on length. For reliable change-point detection, trajectories should ideally contain a minimum of 50-100 steps.

- Algorithm Selection: Choose a change-point detection algorithm designed for single-particle trajectories. The AnDi Challenge provides a performance ranking for various methods [3].

- Parameter Setting: Configure the algorithm's sensitivity (e.g., minimum segment length, significance threshold) based on the expected number of state changes and the signal-to-noise ratio of your data.

- Trajectory Segmentation: Run the algorithm to identify the precise time points (changepoints) where the diffusion coefficient (D) or anomalous exponent (α) changes.

- State Characterization: Analyze each segmented trajectory piece to determine its motion parameters (e.g., D, α, or motion class: confined, Brownian, directed).

- Validation: Validate the identified states and changepoints by comparing the results with other methods, such as HMM or visual inspection of the trajectory and its MSD.

Protocol 2: 3D Single-Molecule Active-feedback Real-time Tracking (3D-SMART) in Porous Materials

This protocol enables the generation of long, high-resolution trajectories necessary to resolve heterogeneous diffusion in complex 3D environments like hydrogels [4].

- Sample Preparation: Fluorescently label nanoparticles of interest. For hydrogel studies, premix nanoparticles into the agarose or other polymer solution before gelation [4].

- Microscope Setup: Use a microscope equipped with 3D active-feedback tracking. The system typically uses electro-optical deflectors (EODs) for lateral scanning and a tunable acoustic gradient (TAG) lens for axial scanning to create a 3D scanning volume of ~1×1×2 μm [4].

- Particle Lock-on: Identify a diffusing nanoparticle and initiate the active-feedback loop. The system uses previous particle position and real-time photon information to estimate the new location.

- Real-Time Tracking: The feedback loop continuously adjusts the position of the scanning volume to "lock" the particle in the center. The voltage signals sent to the EODs and TAG lens are recorded as the particle's 3D trajectory over time.

- Data Collection: Track particles for extended durations (seconds to minutes) to capture rare events like "hopping" between confinement cages [4].

- Trajectory Analysis: Extract quantitative parameters such as confinement sizes, hopping kinetic parameters (on/off rates, lifetimes), and local diffusion coefficients from the highly-sampled trajectories.

Workflow and Relationship Visualizations

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Single-Particle Tracking Experiments

| Item | Function | Example/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Photoactivatable Fluorophores | Enable single-molecule localization by controlling the ON/OFF state of labels in dense environments [7]. | Dendra2, mEos3.2, PA-JF dyes. Choice affects photon budget and localization precision. |

| Self-Labeling Protein Tags | Allow specific labeling of target proteins with bright, photostable organic dyes in live cells [7]. | HaloTag, SNAP-tag. Crucial to wash out free dye to reduce background. |

| Genome Editing Tools | Enable endogenous tagging of proteins, maintaining native expression levels and avoiding artifacts [7]. | CRISPR-Cas9. Preferred over overexpression to study true molecular behavior. |

| 3D Active-Feedback Microscope | Generates long, high-spatiotemporal resolution 3D trajectories of rapidly diffusing particles [4]. | 3D-SMART microscopy. Uses EODs and TAG lens for real-time tracking, overcoming volumetric imaging bottlenecks. |

| Label-Free Tracking via Caustics | Tracks nanoparticles without fluorescent labels, avoiding phototoxicity and altered physicochemical properties [8]. | Uses a standard inverted microscope with enhanced coherence. Ideal for screening in synthetic hydrogels. |

| (Z)-hexadec-9-en-15-ynoicacid | (Z)-hexadec-9-en-15-ynoicacid, MF:C16H26O2, MW:250.38 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Fmoc-Phe-Lys(Boc)-PAB-PNP | Fmoc-Phe-Lys(Boc)-PAB-PNP, MF:C49H51N5O11, MW:886.0 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The Impact of External Fields and Environmental Interactions on Diffusion

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: Why does my Mean Squared Displacement (MSD) plot show a crossover phenomenon (e.g., from subdiffusive to normal scaling) instead of a straight line?

This is a common observation in compartmentalized or heterogeneous environments, such as within living cells or porous materials. The crossover indicates a transition between two dynamical regimes [9] [10].

- Short-Time Regime: At short timescales, the particle's motion is confined within a local domain or compartment (e.g., a membrane patch or a pore). This confinement often leads to anomalous (non-linear) MSD behavior [10].

- Long-Time Regime: At longer timescales, the particle manages to escape the confinement and hop between domains. This leads to normal, linear MSD scaling (

〈x²(t)〉 ~ t), but with a significantly reduced effective diffusion coefficient compared to the local, in-compartment diffusion [10]. - Troubleshooting Tip: This behavior is a hallmark of hop diffusion. Analyze the trajectory for transient confinement zones. The ratio of the short-time to long-time diffusion coefficient provides insight into the molecular properties and barrier permeability of the system [10].

FAQ 2: My MSD increases linearly with time, indicating normal diffusion, but the distribution of particle displacements is non-Gaussian (e.g., shows exponential tails). Why is this happening?

You are observing "Brownian yet non-Gaussian" (BnG) diffusion, a widespread phenomenon in complex environments [9] [10].

- Cause: The BnG diffusion typically arises from population heterogeneity. Your sample may contain a mixture of particles with different diffusion coefficients, or individual particles may be transitioning between different diffusive states over time [11]. The linear MSD suggests normal diffusion on average, but the non-Gaussian displacement distribution reveals the underlying heterogeneity.

- Molecular Origin: In cell membranes, this can be caused by a "quenched disordered environment" where domains or patches with different viscosities or obstacle densities exist stably [9].

- Troubleshooting Tip: Employ analysis methods that are sensitive to multimodal diffusion, such as the logarithmic measure of diffusion [11]. This method transforms displacement data to reveal distinct peaks in the probability density, each corresponding to a different sub-population or diffusive state, without requiring prior labeling.

FAQ 3: How can I distinguish between true anomalous diffusion and transient confinement effects in my molecular dynamics (MD) trajectories?

Disentangling these effects requires analyzing both the MSD and the probability distribution of displacements.

- Genuine Anomalous Diffusion: Manifests as a power-law MSD (

〈x²(t)〉 ~ t^β) over a substantial range of time scales, with a constant anomalous exponentβ. The displacement distribution may also be non-Gaussian [9]. - Transient Confinement in Compartmentalized Media: Appears as a crossover in the MSD from anomalous to normal diffusion, as described in FAQ 1. The non-Gaussianity in this case is a transient effect. For an ensemble of particles, the displacement distribution at intermediate times is a mixture of the uniform distributions within their respective compartments, which can result in an exponential (Laplace) distribution [10].

- Troubleshooting Tip: Perform a time-dependent analysis of the non-Gaussian parameter

α(t)or the displacement distribution. In transient confinement, the non-Gaussianity will peak and then decay as particles begin to explore multiple compartments, whereas in some forms of genuine anomalous diffusion, it may persist.

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Diagnosing Non-Linear MSD Plots

Symptoms: MSD plot is not a straight line on a log-log scale; it may show a clear crossover or a continuous curvature.

| MSD Profile | Potential Cause | Underlying Mechanism | Verification Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Crossover to Linear MSD | Hop Diffusion / Compartmentalization | Particles are temporarily trapped in domains before hopping to adjacent ones [10]. | Check for transient confinement in trajectories; analyze the distribution of waiting times in localized zones. |

| Persistent Subdiffusion (β < 1) | Crowded Environments / Obstacles | Motion is hindered by a dense network of immobile or slow-moving obstacles, leading to a continuous-time random walk (CTRW) with a heavy-tailed waiting time distribution [9]. | Test if the waiting time distribution follows a power law: ω(τ) ~ τ^-(1+σ) [9]. |

| Superdiffusion (β > 1) | Active Transport | Particles are driven by active processes, such as motor proteins, which impart directed motion [11]. | Look for directional persistence in trajectories that is not consistent with passive Brownian motion. |

Guide 2: Resolving Non-Gaussian Displacement Distributions

Symptoms: A histogram of particle displacements (e.g., over a fixed time lag) does not fit a Gaussian curve; it may have sharp peaks or heavy exponential tails [9] [10].

| Observation | Likely Interpretation | Recommended Quantitative Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Exponential (Laplace) Tails | Brownian yet Non-Gaussian (BnG) Diffusion in a static, heterogeneous environment [10]. | Apply the logarithmic measure [11]. Calculate the distribution of single-trajectory diffusion coefficients to see if multiple distinct modes exist. |

| Sharp Peaks with Heavy Tails | May be explained by a CTRW model where the waiting time density has a weak asymptotic property (e.g., power-law) [9]. | Analyze the waiting time distribution between significant jumps in the particle's path. Model the data with a coupled CTRW framework [9]. |

Experimental Protocols & Data Analysis

Protocol 1: Using the Logarithmic Measure to Reveal Multimodal Diffusion

This protocol is ideal for identifying multiple diffusive states from single-particle tracking data without distinct labeling [11].

- Input: A set of 2D particle trajectories

{x(t), y(t)}. - Calculate Increments: For a chosen time lag

Δt, compute the displacements for each trajectory:Δr_i = r(t+Δt) - r(t). - Compute Apparent Diffusion Coefficients: For each displacement vector, calculate an apparent diffusion coefficient

D_appusing the relation for 2D diffusion:D_app = (Δx² + Δy²) / (4Δt). This generates a large set ofD_appvalues from all trajectories and time points. - Logarithmic Transform: Create a new dataset of the logarithms of these values:

Z = log10(D_app). - Analyze Distribution: Plot the probability density function (PDF) of

Z. Distinct peaks in this PDF correspond to different, coexisting diffusive modes in the sample [11]. - Fit and Interpret: Fit the PDF with a multi-modal model (e.g., a sum of Gaussian distributions) to quantify the number of states, their mean diffusion coefficients, and their relative populations.

Protocol 2: Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulation of Diffusion in a Compartmentalized System

This protocol outlines how to set up and analyze MD simulations to study the impact of environmental interactions.

- System Setup:

- Construct a simulation box containing your molecule of interest (e.g., a lipid, drug molecule).

- Model the compartmentalized environment by introducing barriers or a meshwork of obstacles. These can be represented by fixed, repulsive potential energy grids or explicit immobile atoms [10].

- Simulation Run:

- Run multiple, long-timescale MD simulations using a suitable force field.

- Ensure the simulation time is long enough to observe several hopping events between compartments.

- Trajectory Analysis:

- Calculate MSD: Plot the ensemble-averaged MSD and look for the characteristic crossover from confined to normal diffusion [10].

- Calculate Non-Gaussian Parameter (NGP): Compute

α(t) = 〈Δrâ´(t)〉 / (2 * 〈Δr²(t)〉²) - 1. A significant peak inα(t)confirms transient non-Gaussian dynamics. - Displacement Distribution: At a time lag corresponding to the peak of the NGP, plot the histogram of displacements. It should show a strong deviation from a Gaussian, potentially fitting a Laplace distribution [10].

Data Presentation

Table 1: Characteristics of Common Anomalous Diffusion Types

| Diffusion Type | MSD Scaling 〈x²(t)〉 | Displacement Distribution | Common Physical Cause |

|---|---|---|---|

| Normal (Brownian) | Linear: 2Dt |

Gaussian | Unobstructed, homogeneous environment. |

| Confined / Crossover | Crossover: Anomalous → Linear | Non-Gaussian, often exponential at intermediate times [10] | Transient trapping in compartments (hop diffusion) [10]. |

| Subdiffusive (CTRW) | Power-law: t^β (β<1) |

Non-Gaussian | Trapping events with power-law distributed waiting times [9]. |

| Brownian non-Gaussian (BnG) | Linear: 2Dt |

Non-Gaussian, exponential tails [9] [10] | Population heterogeneity in a quenched disordered environment [9] [11]. |

Visualizing Signaling Pathways and Workflows

Troubleshooting Non-Linear MSD

Molecular Interactions in Heterogeneous Environments

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item / Reagent | Function in Research | Example Application / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Dynamics (MD) Software | Simulates the physical movements of atoms and molecules over time, allowing for the study of diffusion in bespoke, controlled environments [12] [13]. | Used to model hop diffusion in compartmentalized media or to simulate the effect of specific molecular interactions with surfactants or polymers [12]. |

| Continuous-Time Random Walk (CTRW) Model | A mathematical framework used to model anomalous diffusion where waiting times between particle jumps are drawn from a potentially heavy-tailed distribution [9]. | Essential for quantifying and interpreting subdiffusion caused by trapping events in crowded environments [9]. |

| Logarithmic Measure Analysis | A data analysis method that transforms displacement data to reveal a spectrum of diffusion coefficients, identifying multiple diffusive modes without distinct labeling [11]. | Ideal for analyzing single-particle tracking data from heterogeneous systems like the cell cytoplasm or membrane, where multiple species or states coexist [11]. |

| Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) | A delivery system used in drug development, particularly for mRNA vaccines. Their behavior is a practical example of diffusion studies in complex, heterogeneous biomembrane systems [14]. | The diffusion of LNPs and their cargo in biological environments is influenced by complex interactions, making them a key area of study [14]. |

| Girard's Reagent P-d5 | Girard's Reagent P-d5|Deuterated Stable Isotope | Girard's Reagent P-d5 is a deuterated stable isotope label for precise MS-based quantification of carbonyl compounds like steroids. For Research Use Only. Not for human use. |

| Omeprazole sulfone-d3 | Omeprazole sulfone-d3, MF:C17H19N3O4S, MW:364.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Distinguishing Between Anomalous Diffusion and Experimental Artifacts

## Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My Mean Squared Displacement (MSD) plot is not linear. Does this always indicate anomalous diffusion? Not necessarily. While a non-linear MSD plot (showing a power-law dependence MSD ∠t^α with α≠1) can be a signature of anomalous diffusion, it can also be caused by experimental artifacts [15]. Key artifacts to rule out include localization errors (noise), drift in the imaging system, or the presence of physical constraints like confinement that truncate the trajectory [3].

Q2: How can I determine if my short, noisy trajectories show genuine subdiffusion or just measurement error? Traditional MSD analysis breaks down for short or noisy trajectories [15]. It is recommended to use machine-learning-based methods, which were shown in community challenges (the AnDi Challenge) to achieve superior performance in these conditions [15] [3]. These methods are better at characterizing anomalous diffusion from individual trajectories where MSD fitting is unreliable.

Q3: What are the common pitfalls when calculating MSD that could lead to misinterpretation? A major pitfall is using "wrapped" coordinates from simulations with periodic boundary conditions instead of "unwrapped" coordinates, which artificially inflates the MSD [16]. Furthermore, MSD analysis can be ambiguous for heterogeneous or non-ergodic processes, where ensemble and time-averaged MSD are not equivalent [15].

Q4: How can I tell if a change in motion is due to a biological interaction or an artifact? Implementing a rigorous changepoint analysis is key. Methods that segment trajectories to identify points where diffusion properties (like coefficient D or exponent α) change can distinguish true biological transitions (e.g., binding, immobilization) from external drift or other artifacts [3]. The performance of these methods has been benchmarked in the 2nd AnDi Challenge [3].

Q5: My MSD curve has a high error margin. How can I improve the reliability of my diffusion coefficient estimate? For experimental trajectories, use established algorithms that provide error estimates for MSD [17]. Ensure you select a linear segment of the MSD plot for fitting, excluding short time-lags (ballistic motion) and long time-lags (poor averaging) [16]. Combining multiple replicates also improves the accuracy of the averaged MSD [16].

Q6: When should I suspect my instrument is causing apparent anomalous diffusion? Persistent directional motion across multiple, unrelated particles in the field of view often indicates system-wide drift. If the apparent anomalous exponent (α) is not reproducible across different experimental replicates or calibration measurements with particles of known diffusivity show deviations from Brownian motion, an instrumental artifact is likely [3].

## Troubleshooting Guide: Common Symptoms and Solutions

| Symptom | Potential Artifact | Underlying Cause | Diagnostic Experiments & Solutions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Apparent subdiffusion (α < 1) at short timescales | Localization noise / measurement error | The inherent uncertainty in pinpointing a particle's position distorts displacement measurements at short time lags [15]. | Fit the MSD while accounting for a noise offset [15]. Compare results from machine learning classifiers, which are more robust to noise [15] [3]. |

| MSD curve plateaus or bends at long times | Confinement / finite system size | The particle's motion is physically restricted by boundaries (e.g., cellular organelles, vesicle walls) [3]. | Check if the plateau value corresponds to a physical dimension of the system. Use models designed for confined diffusion instead of free diffusion. |

| Superdiffusion (α > 1) in a static sample | Stage or fluid drift | The entire sample is moving slowly in one direction, adding a directed component to random particle motion [3]. | Track immobilized particles or fiducial markers to quantify and subtract drift. Ensure the microscope stage and sample are thermally stabilized. |

| High variability in α between trajectories | Mixture of particle populations or states | Genuine biological heterogeneity, where particles exist in different functional states (e.g., bound vs. unbound) [3]. | Perform changepoint analysis to segment trajectories before calculating α [3]. Use statistical tests to confirm the presence of multiple populations. |

| MSD is linear but the diffusion coefficient seems too low | Viscosity mismatch or crowding | The solution viscosity is higher than assumed, or the environment is densely crowded, slowing diffusion. | Measure the diffusivity of standard particles in the same buffer. Account for the effects of macromolecular crowding in your model. |

## Quantitative Data for Anomalous Diffusion Analysis

Table 1: Key Properties of Common Anomalous Diffusion Models. This table helps identify the underlying model based on trajectory properties [15] [3].

| Model Name | Key Mechanism | MSD Scaling (α) | Ergodicity | Increment Distribution |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fractional Brownian Motion (FBM) | Long-range correlated noise [3] | α = 2H (H is Hurst exponent) | Ergodic | Gaussian |

| Continuous-Time Random Walk (CTRW) | Power-law distributed waiting times between steps [15] | α < 1 | Non-ergodic | Can be non-Gaussian |

| Lévy Walk | Power-law distributed step lengths [15] | 1 < α < 2 (superdiffusion) | Non-ergodic | Heavy-tailed |

| Scaled Brownian Motion (SBM) | Time-dependent diffusion coefficient D(t) [15] | α ≠1 | Ergodic | Gaussian |

| Annealed Transient Time Motion (ATTM) | Diffusivity that changes over time in a stochastic manner [15] | α < 1 | Non-ergodic | Can be non-Gaussian |

Table 2: MSD-Based Diagnostics for Common Artifacts. This table summarizes how artifacts manifest in MSD analysis.

| Artifact Type | Effect on MSD Plot | Effect on Anomalous Exponent α | How to Mitigate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Localization Noise | Upward curvature at the shortest time lags; MSD does not approach zero at Δt→0 [15]. | Biases estimates of α downwards, creating false subdiffusion. | Incorporate a noise term in the MSD fitting model: MSD(Δt) = 4D(Δt)^α + 2σ², where σ is localization precision [15]. |

| Constant Drift | MSD grows quadratically (∠Δt²) at long times, mimicking ballistic motion [3]. | Biases α towards 2. | Track fiducial markers or immobilized particles to measure and subtract the drift vector from each frame [3]. |

| Confinement | MSD plateaus to a constant value at long time lags [3]. | The effective α approaches 0 at long times, regardless of the initial motion. | Use a confined diffusion model for fitting. Focus analysis on the initial, linear part of the MSD before the plateau. |

## Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Proper Calculation of MSD from Trajectories

Objective: To accurately compute the MSD from a particle trajectory while avoiding common computational errors [16].

- Input: Use particle trajectories with unwrapped coordinates. If your data comes from simulations with periodic boundary conditions, ensure particles are not artificially wrapped back into the primary cell [16].

- Calculation: Apply the Einstein formula using an efficient algorithm. For a trajectory with positions ( r(t) ), the MSD for a lag time ( \tau ) is: ( \text{MSD}(\tau) = \langle | r(t + \tau) - r(t) |^2 \rangle ), where ( \langle \cdot \rangle ) denotes averaging over all time origins t [16].

- Efficiency: For long trajectories, use a Fast Fourier Transform (FFT)-based algorithm to reduce computational complexity from O(N²) to O(N log N) [16].

- Combining Replicates: When multiple trajectories are available, average the MSDs from each particle. Do not simply concatenate trajectories, as the jump at the concatenation point will artificially inflate the MSD [16].

Protocol 2: Differentiating Anomalous Diffusion from Heterogeneity via Changepoint Analysis

Objective: To determine if a trajectory stems from a single anomalous diffusion model or from a particle switching between different dynamic states [3].

- Data Simulation for Benchmarking: Generate ground-truth trajectories using fractional Brownian motion (FBM) with piecewise-constant parameters (D or α). This simulates a particle changing its motion, e.g., upon binding [3].

- Method Selection: Choose a segmentation method benchmarked in the 2nd AnDi Challenge. These are designed to identify the precise points (changepoints) where diffusion properties change [3].

- Trajectory Segmentation: Apply the chosen algorithm to your experimental trajectory. The output will be a series of segments, each with its own estimated parameters.

- Validation: Calculate the MSD and/or other properties for each segmented state independently. A successful analysis will show a linear MSD on a log-log plot for each segment, confirming a well-defined state, and will resolve the heterogeneity that caused the original, non-linear MSD.

## Workflow and Pathway Visualizations

Diagram 1: Decision Tree for Anomalous Diffusion Analysis

This workflow provides a step-by-step guide to diagnose the source of non-Brownian motion in your data.

Diagram 2: MSD Calculation and Fitting Workflow

This diagram outlines the correct procedure for calculating MSD and extracting a diffusion coefficient, highlighting key troubleshooting points.

## The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Software

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Anomalous Diffusion Studies.

| Item Name | Function / Role | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Fiducial Markers (e.g., fluorescent beads) | Provides a fixed reference point to detect and correct for system-wide drift during imaging [3]. | Immobilized on the coverslip near the sample to track and subtract stage drift from particle trajectories. |

| Standard Calibration Particles | Particles with known, stable diffusion coefficient (D) in a given buffer. | Used to validate microscope setup and MSD analysis pipeline, ensuring measured D matches expected values. |

| andii-datasets Python Package | A software library to generate simulated trajectories with known ground truth for benchmarking analysis methods [3]. | Simulating fractional Brownian motion (FBM) trajectories to test the performance of a new changepoint detection algorithm. |

| KMCLib Software | A program for kinetic Monte Carlo (KMC) simulations, which can model diffusion processes with non-equidistant time-steps [17]. | Studying atomic-scale diffusion events that are too slow for molecular dynamics, including MSD calculation with error estimates. |

| MDAnalysis Python Package | A toolkit to analyze molecular dynamics trajectories, including standardized MSD calculation [16]. | Analyzing simulated MD trajectories of a protein in solution to compute its self-diffusivity from the MSD. |

| 1,3-Dipalmitoyl-2-linoleoylglycerol | 1,3-Dipalmitoyl-2-linoleoylglycerol, MF:C53H98O6, MW:831.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 11-O-Methylpseurotin A | 11-O-Methylpseurotin A, MF:C22H25NO8, MW:431.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

How Polymer Chain Dynamics and Confinement Create Non-Linear MSD Profiles

Troubleshooting Guide: Resolving Non-Linear MSD Profiles

| Problem Area | Specific Issue | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|---|

| System & Confinement | Sub-diffusive or flattened MSD at intermediate times | Chain motion restricted by topological constraints or geometrical confinement [18] | - Characterize confinement geometry (e.g., pore size, NP spacing) [19].- Analyze chain conformation (e.g., Rg) vs. confinement size [19]. |

| Dynamical heterogeneity, multiple relaxation regimes | Presence of both "dry"/slow and "wet"/fast chain regions [18] | - Use site-specific labeling (e.g., inner vs. outer chain segments) [18].- Employ models with site-dependent friction [18]. | |

| Entanglements & Topology | Crossover to sub-diffusive behavior, reptation dynamics | Onset of entanglement effects; chain motion confined to a tube [20] [21] | - Verify simulation/model against active reptation theory predictions [21].- Calculate entanglement length (Me) for your system [22]. |

| Simulation & Analysis | Numerical instability at high fields or long times | Extreme electric fields lowering effective barriers unrealistically [23] | - Check field strength stability (e.g., < 0.1 V/nm for PEO/LiTFSI) [23].- Use appropriate thermostats (e.g., Nose-Hoover) [22]. |

| MSD artifacts from poor equilibration | Insufficient relaxation of initial configuration, especially for dense/glassy systems [22] | - Perform long NPT runs to equilibrate density [22].- Check energy and pressure stability before production run. | |

| Polymer-Specific Interactions | Segmental dynamics slower than expected | Increased monomeric friction near surfaces/grafting points [18] | - Incorporate friction profiles in analysis models [18].- Check for specific polymer-surface interactions (e.g., γSL) [19]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My MSD plot for a confined polymer system shows a clear plateau or severely suppressed dynamics. What does this mean?

This is a classic sign of confinement-induced dynamical heterogeneity. Your system likely contains chain segments with drastically different mobilities. For instance, in polymer-grafted nanoparticles, segments near the grafting point ("dry layer") experience much higher friction and slower dynamics than segments in the outer regions ("wet layer") [18]. This creates an average MSD that appears flattened.

- How to verify: Use a technique like Neutron Spin Echo (NSE) with selective deuterium labeling on different parts of the chain (inner vs. outer segments). This allows you to probe the dynamics of specific chain sections rather than the global average [18].

- How to model: Avoid models that assume a single, homogeneously relaxing ensemble. Instead, use an analysis that allows for at least two differently relaxing chain ensembles or a position-dependent friction coefficient [18].

Q2: In my simulations of entangled polymers, the MSD shows a distinct sub-diffusive regime (∼t^0.5). What is the physical origin of this, and how can I validate my model?

The sub-diffusive regime where MSD ∠t^0.5 is the signature of reptation dynamics. The chain is confined to a tube created by the topological constraints of its neighboring chains, and its motion is primarily one-dimensional diffusion along the tube contour [20] [21].

- How to validate: A powerful method is to simulate active entangled polymers. Apply a constant force that imparts a drift velocity along the primitive path of the chain. A valid model will show that while conformational properties (e.g., Rg) remain largely unchanged, the dynamics are strongly accelerated, and the diffusion coefficient becomes independent of molecular weight at moderate activity levels, as predicted by active reptation theory [21].

Q3: When applying an electric field in my ion-conducting polymer simulations, the MSD/conductivity becomes highly non-linear and the simulation becomes unstable. What should I check?

This indicates you are in the high-field non-linear regime. The electric field is tilting the energy landscape, reducing the effective barriers for ion hopping, and can eventually cause numerical instabilities [23].

- How to diagnose:

- Check field strength: Compare your field (E) to known thresholds. For a PEO/LiTFSI electrolyte, strong non-linear effects appear above ~0.1 V/nm, and simulations can become unstable at higher fields [23].

- Analyze hopping distances: In the high-field regime, you can extract an effective hopping distance. This value should be comparable to typical ion-ion or ion-polymer coordination distances (on the order of Ångströms) from your system's structural analysis [23].

- How to proceed: Ensure you are using a robust thermostat and consider using a smaller timestep or a different integration algorithm for high-field simulations.

Experimental & Simulation Protocols

Protocol 1: Probing Confined Dynamics with Neutron Spin Echo (NSE) Spectroscopy

This protocol is based on studies of one-component nanocomposites (OCNCs) where polymers are grafted to nanoparticle cores [18].

- Sample Synthesis:

- System: Create block-copolymers with a cross-linked core (e.g., deuterated 1,2-polybutadiene) and a grafted shell (e.g., poly(ethylene oxide), PEO) [18].

- Labeling: Prepare at least three differently labeled versions:

- Inner-labeled: Tags attached near the grafting point to the nanoparticle.

- Outer-labeled: Tags attached to the free ends of the grafts.

- Fully-labeled: The entire graft is labeled [18].

- Structural Characterization:

- Use Small-Angle X-Ray/Neutron Scattering (SAXS/SANS) to determine the nanoparticle structure, size distribution, and overall melt structure. A Percus-Yevick structure factor can model a concentrated colloidal dispersion [18].

- Dynamic Measurement:

- Perform Neutron Spin Echo (NSE) Spectroscopy on all labeled samples.

- NSE measures the intermediate scattering function, providing direct insight into the segmental and chain dynamics on nanosecond to hundred-nanosecond timescales [18].

- Data Analysis:

- Do not fit the data with a single phenomenological function (e.g., KWW) for the entire chain.

- Solve a Langevin equation that includes a spatial friction profile.

- Compare the calculated dynamic structure factor (using its eigenvalues and eigenvectors) to the experimental data. This will reveal the increased friction towards the grafting points and the effect of topological restrictions [18].

Protocol 2: Simulating Active Entangled Polymer Dynamics

This protocol outlines how to use molecular dynamics (MD) to verify entanglement dynamics and understand the MSD, based on the work of [21].

- System Setup:

- Model: Use a coarse-grained model like the Kremer-Grest bead-spring model.

- System Composition: Simulate a few active, shorter chains diluted in a mesh of very long, passive linear chains. This setup minimizes "constraint release" effects from the motion of the surrounding matrix [21].

- Simulation Execution:

- Apply a constant active force of the form Factive = Fa * u. Here, u is the unit vector along the end-to-end direction of the chain, imparting a polar drift velocity along the chain's primitive path [21].

- Run simulations for a wide range of activity values (F_a).

- Data Analysis and Validation:

- Conformational Properties: Confirm that the radius of gyration (Rg^2) and tube structure are not significantly altered by the activity.

- Dynamics: Calculate the MSD and chain diffusion coefficient.

- Validation Check: Verify that your results match key predictions of active reptation theory:

- The chain diffusion coefficient becomes independent of molecular weight at moderate activity levels.

- A significant reduction in viscosity is observed due to accelerated relaxation [21].

Diagram Title: Diagnostic Workflow for Non-Linear MSD Profiles

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Materials

| Item | Function & Role in Analysis |

|---|---|

| Selective Deuterium Labeling | Enables probing site-specific dynamics in NSE experiments. Labels on inner/outer chain segments reveal heterogeneous friction and mobility [18]. |

| One-Component Nanocomposites (OCNCs) | Model system for studying chain confinement. Self-assembled particles with grafted polymers provide a well-defined, dispersed nanostructure without aggregation issues [18]. |

| Coarse-Grained MD Models (e.g., Kremer-Grest) | Computational tool for simulating long-time chain dynamics. Allows control over parameters like entanglement length and application of active forces to test theories [21]. |

| Anodic Aluminum Oxide (AAO) Membranes | A versatile mesoporous template with tunable pore size for experimental studies of polymers under strict geometrical confinement [19]. |

| Poly(ethylene oxide) (PEO) | A widely used model polymer in both simulations and experiments for studying dynamics, ion conduction, and mechanical properties [22] [23]. |

| (S,R,S)-AHPC-Me-C10-NH2 | (S,R,S)-AHPC-Me-C10-NH2, MF:C34H53N5O4S, MW:627.9 g/mol |

| Boc-Aminooxy-PEG5-amine | Boc-Aminooxy-PEG5-amine, MF:C17H36N2O8, MW:396.5 g/mol |

Advanced Analytical Frameworks: From Theory to Practical Implementation

Implementing Robust Changepoint Detection for Trajectory Segmentation

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is change-point detection (CPD) and why is it important for analyzing molecular dynamics trajectories? Change-point detection (CPD) is the problem of identifying abrupt variations or changes in the distribution of a temporal signal [24]. In molecular dynamics (MD), this helps pinpoint precise moments of structural transitions—such as nucleation events, protein folding, or phase changes—within a particle trajectory [25]. Automating this detection is crucial for large-scale studies where manual inspection of hundreds of simulations is infeasible. It enables accurate segmentation of trajectories into stable meta-stable states and transition regions, which is foundational for calculating meaningful physical properties like diffusivity from segments of the Mean Squared Displacement (MSD) plot that exhibit linear behavior [26].

FAQ 2: My MSD plot is nonlinear. How can changepoint detection help? A nonlinear MSD plot often indicates that a single diffusion mode does not describe the entire trajectory. The system may undergo a transition between different states (e.g., from ballistic to diffusive motion, or between confined and free diffusion). Robust changepoint detection can automatically segment the full trajectory into homogeneous intervals, each potentially corresponding to a distinct dynamical state [25] [24]. You can then compute an MSD for each segment, which should yield a linear relationship for the middle section of the MSD plot, allowing for an accurate calculation of the self-diffusivity, D, using the Einstein relation: (D_d = \frac{1}{2d} \times \text{slope of the MSD}) [26].

FAQ 3: What is the difference between offline and online changepoint detection? The choice between offline and online algorithms depends on your experimental needs [24].

| Feature | Offline Detection | Online Detection |

|---|---|---|

| Data Access | Processes the complete dataset simultaneously [24] | Processes data points sequentially as they arrive [24] |

| Primary Use | Post-analysis, for accurate identification of all changes [25] | Real-time monitoring, for immediate response to changes [25] |

| Example in MD | Analyzing a completed simulation to find all folding events [25] | Triggering high-frequency data storage upon a nucleation event [25] |

FAQ 4: What are some common cost functions for CPD, and how do I choose? Cost functions measure the homogeneity of data within a segment. Two common types are:

- Piecewise Linear Fit: Implemented in tools like

dupin, these cost functions are sensitive to shifts in the mean or trend of a signal [25]. They are generally effective for detecting changes in the baseline of order parameters or MSD-derived signals. - Robust/Wilcoxon-Type: Based on ranks or spatial signs rather than raw values, these functions are less sensitive to outliers in the data [27]. They are advantageous when your trajectory or derived signal contains substantial noise or extreme values.

For molecular trajectories, start with a piecewise linear model. If you suspect your data contains outliers that are causing false positives, switch to a robust method [27].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: The detector fails to find the correct changepoints.

Potential Cause and Solution Tree:

Detailed Solutions:

Poor Descriptor Selection: The chosen descriptor must be sensitive to the structural or dynamic transition you want to detect [25].

- Actionable Protocol: Compute a diverse set of order parameters for your system. For local structural changes (e.g., crystallization), use Steinhardt order parameters or Smooth Overlap of Atomic Positions (SOAP). For dynamical transitions visible in the MSD, ensure you are using unwrapped coordinates to compute the MSD [26]. Using a combination of descriptors often yields the best results.

Incorrectly Tuned Detection Sensitivity: All CPD algorithms have parameters that control how sensitive they are to changes.

- Actionable Protocol: Most cost-based methods require a penalty parameter that prevents over-segmentation. Use the "elbow" method on the cost function to determine the correct number of changepoints [25]. Manually annotate a small portion of your trajectory to validate the algorithm's performance and tune the parameters accordingly.

Underlying Signal is Too Noisy:

- Actionable Protocol: Apply a smoothing filter (e.g., a Savitzky-Golay filter) to your generated signal before running the CPD algorithm. Alternatively, use a robust changepoint detection method that is less sensitive to outliers, such as one based on U-statistics or spatial signs [27].

Issue 2: Implementing online detection for real-time analysis.

Potential Cause and Solution Tree:

Detailed Solutions:

Handling Data Streams:

- Actionable Protocol: Implement an ε-real-time algorithm [24]. This means the algorithm processes data in small, sequential batches of size ε (e.g., every 10-100 simulation frames). Tools like

dupinare designed with interfaces suitable for such online detection, allowing you to update the detection model as new data arrives [25].

- Actionable Protocol: Implement an ε-real-time algorithm [24]. This means the algorithm processes data in small, sequential batches of size ε (e.g., every 10-100 simulation frames). Tools like

Minimizing Detection Lag:

- Actionable Protocol: The choice of ε is a trade-off. A smaller ε (e.g., 1) provides the fastest response but might be less statistically reliable. A larger ε provides more data points for a confident decision but introduces a longer lag. Optimize this for your specific application by testing different batch sizes on a pre-recorded trajectory.

Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol 1: Generating a Signal for Trajectory Segmentation from MSD

- Unwrap Coordinates: Ensure your particle trajectory is in unwrapped coordinates to prevent artificial jumps from periodic boundary conditions from skewing the MSD calculation [26].

- Calculate MSD: For a given particle or group of particles, compute the MSD over the entire trajectory using the Einstein formula. Efficient FFT-based algorithms (e.g., in

MDAnalysis.analysis.msdwithfft=True) are recommended for long trajectories [26]. - Preprocess the MSD Signal: The raw MSD plot is often noisy. Apply smoothing and then compute the instantaneous slope (e.g., by numerical differentiation) or use the MSD values directly as the input signal for CPD. The choice depends on whether you are interested in changes in the mean value or the trend of the MSD.

- Apply Changepoint Detection: Feed the preprocessed signal into your chosen CPD algorithm (e.g.,

dupinwith a piecewise linear cost function) to identify points where the diffusion characteristics change [25].

Protocol 2: Validating Detected Changepoints

- Manual Annotation: Create a "ground truth" by manually identifying obvious transition points in a small subset of your trajectories.

- Compute Metrics: Compare the algorithm's output to your ground truth. Standard metrics include:

- Precision: The percentage of detected changepoints that are correct.

- Recall: The percentage of actual changepoints that were successfully detected.

- Time Lag: For online detection, the average delay between a true change and its detection.

- Cross-Validation: Use the parameters that work best on your validation set for the full analysis.

Comparison of CPD Algorithms

The table below summarizes different CPD approaches relevant to MD analysis.

| Algorithm / Tool | Core Methodology | Key Strength | Potential Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|

| dupin [25] | Cost-based optimization with piecewise linear models; interfaces with ruptures library. |

Highly automated pipeline; applicable to both offline and online detection. | Performance heavily relies on selection of informative input descriptors. |

| BEAST [28] | Bayesian ensemble modeling to average multiple decomposition models. | Provides credible uncertainty measures (e.g., probability of changepoints). | Computationally intensive, may be slow for very long trajectories. |

| Robust CUSUM [27] | Based on U-statistics and spatial signs (generalized Wilcoxon test). | Less sensitive to outliers in the data compared to classical CUSUM. | More complex implementation; may require custom bootstrap for critical values. |

| Classical CUSUM | Cumulated sums of deviations from the mean. | Simple and computationally efficient. | Sensitive to outliers and assumes a specific change type (e.g., mean shift). |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Tool / Resource | Function in Experiment | Relevant Context |

|---|---|---|

| dupin [25] | A Python package for automatic event detection in particle trajectories. It performs data preprocessing, augmentation, and CPD. | The primary tool for segmenting trajectories based on changes in order parameters or other signals. |

| MDAnalysis [26] | A Python toolkit to analyze MD trajectories. Its EinsteinMSD module is used to compute MSDs. |

Used in the preprocessing stage to convert particle positions into an MSD signal for CPD. |

| freud [25] | A Python library for efficient analysis of particle trajectories and calculation of order parameters. | Used to compute descriptors like Steinhardt order parameters, which serve as the input signal for dupin. |

| Ruptures [25] | A Python library for offline changepoint detection with multiple cost functions and search methods. | Can be used as the core detection algorithm within a larger pipeline, either directly or via dupin. |

| HOOMD-blue [25] | A general-purpose particle simulation toolkit used to generate the MD trajectories. | The source of the raw trajectory data that needs to be segmented and analyzed. |

| signac [25] | A Python framework for managing and organizing large-scale simulation data and workflows. | Helps manage the data from hundreds of simulations, making CPD workflows reproducible and scalable. |

| Boc-PEG4-sulfone-PEG4-Boc | Boc-PEG4-sulfone-PEG4-Boc, MF:C30H58O14S, MW:674.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Propargyl-PEG3-methyl ester | Propargyl-PEG3-methyl ester, CAS:2086689-09-8, MF:C11H18O5, MW:230.26 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Leveraging Machine Learning for Automated MSD Analysis and Pattern Recognition

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why does my MSD plot show a plateau or decreased slope at longer lag times instead of a linear relationship?

This indicates insufficient sampling or trajectory length. The MSD requires adequate sampling for accurate diffusion calculation. If your trajectory is too short, the MSD at longer lag times becomes noisy and poorly averaged [29]. Solution: Increase simulation time or use the -maxtau flag in GROMACS to cap maximum time delta and avoid miscalculations from undersampled regions [30].

Q2: My MSD analysis shows anomalously high values. What could be causing this?

This often results from using wrapped instead of unwrapped coordinates. When atoms cross periodic boundaries and are wrapped back into the primary cell, it artificially inflates displacement measurements [29]. Solution: Always use unwrapped trajectories. In GROMACS, use gmx trjconv -pbc nojump; in MDAnalysis, ensure coordinates follow the unwrapped convention before MSD calculation [29].

Q3: How can I determine the optimal linear segment for diffusion coefficient calculation?

The linear segment represents the "middle" of the MSD plot, excluding ballistic trajectories at short time-lags and poorly averaged data at long time-lags [29]. Solution: Create a log-log plot where the linear segment shows a slope of 1. Use -beginfit and -endfit parameters in GROMACS or manually select the range as demonstrated in MDAnalysis documentation [30] [29].

Q4: What does poor contrast ratio in my MSD visualization indicate, and why does it matter? While not affecting computational results, poor contrast (below 4.5:1 for standard text) hinders interpretation and publication quality [31] [32]. Solution: Ensure foreground-background color pairs meet WCAG guidelines. For molecular visualization, use high-contrast color palettes with minimum 3:1 ratio [31].

Q5: My MSD calculation is extremely slow with long trajectories. How can I optimize performance?

The standard MSD algorithm has O(N²) scaling with trajectory length [29]. Solution: Use FFT-based algorithms (set fft=True in MDAnalysis or similar implementations) which reduce scaling to O(N log N). In GROMACS, use -maxtau to limit maximum time delta [30] [29].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Nonlinear MSD Plots in Molecular Dynamics

Problem Identification Nonlinear MSD plots deviate from the theoretical linear relationship expected for normal diffusion, showing curved segments that complicate diffusion coefficient calculation.

Root Causes

- Insufficient sampling at long lag times [29]

- Finite size effects from simulation box constraints [29]

- Anomalous diffusion processes in complex molecular systems [33]

- Coordinate wrapping artifacts from periodic boundary conditions [29]

- Non-equilibrium dynamics during simulation timeframe [33]

Step-by-Step Resolution

- Validate trajectory preprocessing: Ensure proper unwrapping of coordinates using

gmx trjconv -pbc nojump(GROMACS) or equivalent in other packages [29]. - Assess sampling adequacy: Plot MSD with error estimates using

NBlocksToCompareoption in trajectory analysis tools [34]. - Identify linear regime: Generate log-log plot to identify segment with slope ≈1 indicating normal diffusion [29].

- Apply appropriate fitting: Use only the linear segment for diffusion calculation with

-beginfitand-endfitparameters [30]. - Implement machine learning detection: Train pattern recognition models to automatically identify linear regions using feature vectors derived from MSD curvature [33].

Prevention Strategies

- Ensure trajectory lengths exceed diffusion timescales by 10-100x [29]

- Use multiple replicates combined with ensemble averaging [29]

- Implement automated quality checks with ML-based pattern recognition [33] [35]

Issue: Memory Errors During Large-Scale MSD Analysis

Problem Identification MSD calculations fail due to insufficient memory, particularly with long trajectories or large molecular systems.

Technical Background Standard MSD algorithm memory requirements scale with O(τmax²) where τmax is maximum lag time [30] [29].

Resolution Protocol

- Implement FFT-based algorithms: Use

fft=Truein MDAnalysis or equivalent FFT implementations [29]. - Limit maximum lag time: Apply

-maxtauparameter in GROMACS to cap time delta [30]. - Strategic frame sampling: Use

-dtoption to analyze subsets of frames [30]. - Distributed computing: Split analysis across multiple replicates or system partitions [29].

- Progressive analysis: Use

-trestartto control restarting point frequency [30].

Table 1: MSD Algorithm Performance Characteristics

| Algorithm | Time Complexity | Memory Usage | Implementation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard Windowed | O(N²) | High | GROMACS gmx msd |

| FFT-Based | O(N log N) | Moderate | MDAnalysis fft=True |

| Block Averaging | O(N) | Low | AMS NBlocksToCompare |

Issue: Inconsistent Diffusion Coefficients Across Replicates

Problem Identification Significant variation in calculated diffusion coefficients between simulation replicates under identical conditions.

Diagnostic Procedure

- Calculate inter-replicate variance: Use

NBlocksToComparefunctionality to obtain error estimates [34]. - Check equilibration: Ensure all replicates reached proper equilibrium before MSD analysis.

- Verify consistent preprocessing: Confirm identical unwrapping and alignment protocols [29].

- Assess statistical convergence: Determine if sampling adequately captures diffusion timescale.

Resolution Framework

- Combine replicates properly: Use appropriate concatenation methods that avoid artificial inflation between trajectories [29].

- Implement ensemble averaging: Calculate average MSD across multiple replicates rather than averaging diffusion coefficients.

- Apply block analysis: Divide individual trajectories into blocks for error estimation [34].

- Utilize ML pattern recognition: Train models to identify systematic errors across replicates [33] [36].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Standardized MSD Analysis with Linear Regression

Objective: Calculate diffusion coefficient from molecular dynamics trajectory with proper error estimation.

Materials and Software

- Molecular dynamics trajectory (unwrapped coordinates)

- GROMACS, MDAnalysis, or AMS analysis suite

- Python/NumPy/SciPy for additional analysis

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Trajectory Preparation: Convert to unwrapped coordinates using

gmx trjconv -pbc nojumpor equivalent [29]. - MSD Calculation: Execute MSD analysis with appropriate parameters: [30]

- Linear Segment Identification: Plot MSD with log-log scale and identify region with slope ≈1 [29].

- Diffusion Coefficient Calculation: Apply linear regression to selected segment: [29]

- Error Estimation: Calculate standard error from regression or block analysis [34].

Quality Control Metrics

- Regression R² value > 0.98 for linear segment

- Adequate sampling indicated by smooth MSD curve in fitting region

- Multiple replicate consistency within statistical error

Protocol 2: Machine Learning-Enhanced MSD Analysis

Objective: Implement pattern recognition to automatically identify linear MSD regions and classify diffusion behavior.

Feature Engineering

- Curvature Features: Calculate second derivative of MSD across multiple window sizes [33].

- Statistical Moments: Compute skewness and kurtosis of MSD slope distribution [33].

- Time-Scale Features: Extract characteristic timescales from MSD curvature transitions [33] [36].

- Noise Metrics: Quantify signal-to-noise ratio at different lag times [33].

Model Training Protocol

- Dataset Preparation: Curate labeled MSD trajectories with expert-identified linear regions [36].

- Feature Extraction: Compute comprehensive feature vectors for each MSD profile [33].

- Model Selection: Train multiple architectures (logistic regression, neural networks) for linear region classification [35] [36].

- Validation: Test model performance against held-out expert annotations [36].

Implementation

Experimental Workflows

MSD Analysis and Troubleshooting Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Software Solutions

| Tool/Reagent | Function/Purpose | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| Trajectory Unwrapping Tools | Corrects periodic boundary artifacts in coordinates | GROMACS gmx trjconv -pbc nojump [29] |

| FFT-MSD Algorithms | Enables efficient MSD calculation for long trajectories | MDAnalysis EinsteinMSD with fft=True [29] |

| Block Analysis Framework | Provides error estimation through trajectory segmentation | AMS NBlocksToCompare parameter [34] |

| Linear Regression Modules | Calculates diffusion coefficients from MSD slopes | SciPy linregress with optimized fitting range [29] |

| Pattern Recognition Models | Automates identification of linear MSD regions | ML classifiers trained on MSD curvature features [33] [36] |

| Contrast Verification Tools | Ensures visualization accessibility for publications | WCAG contrast checkers (minimum 4.5:1 ratio) [31] [32] |

| N-(Mal-PEG6)-N-bis(PEG7-TCO) | N-(Mal-PEG6)-N-bis(PEG7-TCO), MF:C78H137N7O30, MW:1652.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 4-(6-Methyl-1,2,4,5-tetrazin-3-yl)phenol | 4-(6-Methyl-1,2,4,5-tetrazin-3-yl)phenol|Tetrazine Linker | 4-(6-Methyl-1,2,4,5-tetrazin-3-yl)phenol is a methyltetrazine linker with a phenol group for bioconjugation research. This product is For Research Use Only. Not for human use. |

ML Pattern Recognition for MSD Analysis

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the fundamental theory behind calculating self-diffusivity from MSD? The self-diffusion coefficient (D) is calculated from the mean square displacement (MSD) using the Einstein relation. In three dimensions, the formula is: [ D = \frac{1}{6} \lim_{t \to \infty} \frac{d}{dt} \text{MSD}(t) ] In practice,

Dis determined by calculating one-sixth of the slope of the MSD versus time plot in the linear regime [37] [38]. The GROMACSgmx msdtool performs a least-squares fitting of a straight line (D*t + c) to the MSD curve to provide the diffusion constant [39].Which GROMACS tool is used for MSD calculation and what is its basic syntax? The

gmx msdtool is used to compute mean square displacements. A basic command syntax is:This command will calculate the MSD for all atoms in the trajectory against the structure file and output the results to an .xvg file [39].

Why is my MSD plot non-linear or wobbly, and how can I fix it? Non-linear or noisy MSD plots, especially at long time scales, are often a sign of poor sampling. This can manifest as a wobbly line after an initial straighter region [39]. To mitigate this:

- Ensure your production simulation is long enough; the linear regime of the MSD must be sufficiently sampled.

- Use the

-maxtauoption to cap the maximum time delta for frame comparison, which can avoid poorly averaged data at long time lags [39]. - For individual molecules, use the

-moloption, which can provide a more accurate error estimate based on statistics between molecules [39].

I get an error about 'non-integral time'. What does this mean and how do I resolve it? This error occurs when the

gmx msdtool encounters non-integer time values in your trajectory, which disrupts its internal time discretization. The solution is to subsample your trajectory to ensure time steps are integers. You can use thegmx convert-trjtool for this purpose [40]:Then, use the new

prod_subsampled.xtcfile for your MSD analysis.Why is it critical to use 'unwrapped' coordinates for a correct MSD calculation? Using wrapped coordinates (where molecules are put back into the primary simulation cell when they cross the periodic boundary) will cause the MSD to be artificially low and eventually plateau. The MSD calculation requires unwrapped coordinates that accurately reflect the true distance a particle has traveled. In GROMACS, you can ensure this by using the

-pbc nojumpflag withgmx trjconvto remove periodic boundary effects before analysis [16].What are the key parameters in

gmx msdthat control the linear fit for the diffusion coefficient? The most critical parameters for defining the linear region of the MSD plot for diffusion coefficient calculation are-beginfitand-endfit. These specify the time range for the linear regression.- By default, if

-beginfitis set to-1, the fitting starts at 10% of the total time. - If

-endfitis set to-1, the fitting goes to 90% of the total time [39]. You should visually inspect your MSD plot to identify the linear regime and set these parameters accordingly.

- By default, if

My

gmx msdanalysis is slow or runs out of memory. How can I improve performance? The MSD calculation can be computationally intensive and scale poorly with trajectory length. To improve performance and avoid out-of-memory errors:- Use the

-maxtauoption to limit the maximum time delta for frame comparisons, reducing both computation time and memory usage [39]. - Analyze a smaller, representative group of atoms or molecules.

- Consider using a trajectory with a lower time resolution (e.g., by using

gmx convert-trj -dtto save frames less frequently).

- Use the

How do I calculate the MSD for the center of mass of molecules, rather than individual atoms? Use the

-molflag. This option will make molecules whole across periodic boundaries and plot the MSD for the center of mass of individual molecules. When using-mol, the chosen index group will be automatically split into molecules [39].

Troubleshooting Guide

This section addresses specific error messages and common problems, providing step-by-step solutions.

Problem 1: 'Out of memory' error during MSD calculation.

- Description: The program fails because it cannot allocate enough memory for the analysis, often occurring with long or large trajectories [39] [41].

- Solution Steps:

- Reduce system scope: Select a smaller group of atoms or molecules for analysis in your index file [41].

- Use the

-maxtauflag: This caps the maximum time delta, significantly reducing memory requirements [39]. - Subsample the trajectory: Use

gmx convert-trj -dtto reduce the number of frames analyzed. - Check computer resources: As a last resort, run the analysis on a machine with more RAM [41].

Problem 2: MSD plot is non-linear or does not show the expected linear regime.

- Description: The MSD plot is curved or oscillates, making it impossible to fit a straight line for diffusion coefficient calculation. This is often a sampling issue or an artifact of trajectory processing.

- Solution Steps:

- Verify coordinate unwrapping: This is the most common cause. Process your trajectory with

gmx trjconv -pbc nojumpto create an unwrapped trajectory and use the output for MSD analysis [16]. - Ensure sufficient sampling: Confirm that your production run is long enough to observe Fickian (random) diffusion. The simulation time should be several times longer than the time at which the MSD becomes linear.

- Adjust the fitting range: Visually identify the linear segment of the MSD plot and manually set the

-beginfitand-endfitparameters to this range, avoiding the short-time ballistic regime and the long-time noisy region [39]. - Check for sufficient averaging: For molecular diffusion, use the

-molflag to get better statistics by averaging over individual molecules [39].

- Verify coordinate unwrapping: This is the most common cause. Process your trajectory with

Problem 3: 'Frame X has non-integral time' error.

- Description: The analysis fails because the time in the trajectory is not an integer, which

gmx msdcannot handle [40]. - Solution Steps:

- Subsample the trajectory to enforce integer time steps using:

- Use the newly created

output.xtcfile as input for thegmx msdcommand.

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Detailed Protocol: Calculating Self-Diffusivity from an MD Trajectory

This protocol outlines the steps to compute the self-diffusion coefficient for a solute or solvent in a molecular dynamics simulation using GROMACS.

Trajectory Unwrapping (Critical Pre-processing Step):

- Objective: Generate a trajectory with unwrapped coordinates to correctly monitor molecular displacements across periodic boundaries.

- Command:

- Note: Select the desired group (e.g., "System") when prompted. This step is essential for obtaining accurate MSD values [16].

MSD Calculation:

- Objective: Compute the mean square displacement for the group of interest.

- Command for molecular center-of-mass MSD:

- Parameters:

-f,-s: Input unwrapped trajectory and structure file.-n: Index file containing the group to analyze.-mol: Calculate MSD for the center of mass of each molecule (highly recommended for molecular diffusivity).-type xyz: Calculate the 3-dimensional MSD.

Determining the Linear Fit Range:

- Objective: Identify the appropriate time range over which to fit the MSD to obtain the diffusion coefficient.

- Action: Visually inspect the

msd.xvgfile. The linear regime is typically the "middle" portion of the plot, after the initial ballistic motion and before the noisy long-time tail. Note the start and end times (in ps) for this linear segment [16].

Diffusion Coefficient Extraction:

- Objective: Perform a linear regression on the MSD plot in the identified linear regime.

- Command with custom fit range:

- Output: The command line output of

gmx msdwill report the diffusion constant and an error estimate. The slope of the linear fit is equal to ( 6D ) for a 3D MSD.

Parameter Tables