Optimal Simulation Box Size for Accurate Diffusion Coefficient Calculation: A Guide for Biomedical Researchers

Accurately calculating diffusion coefficients with molecular dynamics is crucial for predicting molecular transport in drug delivery and pharmaceutical development.

Optimal Simulation Box Size for Accurate Diffusion Coefficient Calculation: A Guide for Biomedical Researchers

Abstract

Accurately calculating diffusion coefficients with molecular dynamics is crucial for predicting molecular transport in drug delivery and pharmaceutical development. This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers on a critical, yet often overlooked, factor: selecting the optimal simulation box size. We cover the foundational theory of finite-size effects, present practical calculation methodologies, offer troubleshooting advice for common pitfalls, and establish validation frameworks to ensure computational results are both accurate and reliable for informing experimental work.

Why Size Matters: The Foundational Impact of Box Size on Diffusion Coefficients

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What are finite-size effects in molecular dynamics simulations? Finite-size effects are artifacts that arise from using a simulation box of limited size, which can lead to inaccurate calculation of properties like diffusion coefficients. These effects include spurious hydrodynamic interactions between periodic images of particles and the constraint of total momentum conservation [1].

How do hydrodynamic interactions influence diffusion calculations? Hydrodynamic interactions describe how the motion of one particle affects others through the surrounding fluid. In simulations, these interactions can be inaccurately captured when using periodic boundary conditions, leading to significant errors in calculated diffusion coefficients, especially in confined systems [2] [1].

Why does my calculated diffusion coefficient decrease when I increase my system size? This occurs because larger systems better capture long-range hydrodynamic interactions that retard diffusion. In smaller systems with periodic boundary conditions, these interactions are truncated, leading to artificially high diffusion coefficients. The diffusion coefficient approaches its true bulk value as system size increases [3] [1].

What is the difference between short-time and long-time diffusion coefficients? Short-time diffusion coefficients reflect immediate, local molecular motions, while long-time coefficients incorporate collective effects and obstacles that emerge over extended periods. In plasma membranes, for example, the presence of immobile proteins significantly reduces long-time diffusion compared to short-time values [4].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Inaccurate Diffusion Coefficients in Confined Systems

Symptoms:

- Diffusion coefficients vary significantly with changes in simulation box size

- Results differ from experimental measurements even with accurate force fields

- Unexpected system size dependence in calculated transport properties

Diagnosis and Solutions:

Table: Finite-Size Correction Methods for Diffusion Coefficients

| Method | Principle | Applicability | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Analytical hydrodynamic corrections [1] | Uses theoretical expressions to account for periodic image interactions | Molecular dynamics, Lattice-Boltzmann, DPD | Less accurate for very narrow pores |

| Hybrid MD-theoretical approach [3] | Separates local molecular and collective hydrodynamic contributions | Liquid systems, electrolyte solutions | Requires knowledge of liquid viscosity |

| Modified periodic boundary conditions | Adjusts boundary conditions to minimize artifacts | Specific simulation geometries | Implementation complexity |

Step-by-Step Resolution:

- Determine the Nature of the System: Identify if your system represents bulk conditions or true confinement. For slit pores, the physically relevant confining length must be distinguished from artificial finite-size effects [1].

Calculate Correction Terms: Apply analytical expressions for diffusion coefficient corrections. For elongated systems, the correction takes the form: ( D\infty = DL + \xi kT/6\pi\eta L ), where ( D\infty ) is the bulk diffusion coefficient, ( DL ) is the measured coefficient, ( \eta ) is viscosity, and ( L ) is system size [3].

Validate with Multiple System Sizes: Perform simulations at different box sizes to characterize the finite-size dependence and verify that corrected values converge [1].

Implement Hybrid Approach when Appropriate: For liquid systems, calculate the local molecular contribution using small-scale MD (less than 100 particles) and add the hydrodynamic contribution analytically [3].

Problem: Accounting for Hydrodynamic Interactions in Membrane Systems

Symptoms:

- Protein diffusion rates in plasma membranes are significantly lower than in model membranes

- Deletion of cytoplasmic domains has little effect on diffusion rates

- Discrepancies between tracer, gradient, and rotational diffusion measurements

Diagnosis and Solutions:

Theoretical Framework: In plasma membranes containing both mobile and immobile proteins, Brinkman's equation governs the hydrodynamics rather than the standard Stokes equation. This accounts for the damping effect of immobile particles on fluid flow [4].

Resolution Workflow:

- Characterize Protein Immobilization: Determine the fraction of immobile integral membrane proteins in your system.

Calculate Hydrodynamic Mobilities: Use solutions of Brinkman's equation to determine short-time diffusion coefficients, which show decreased mobility with increasing immobile fractions [4].

Incorporate Excluded Area Effects: Combine hydrodynamic mobilities with Monte Carlo simulations that account for direct obstructions to determine long-time diffusion coefficients [4].

Compare with Experimental Systems: Apply this combined hydrodynamic-excluded area theory to systems like band 3 diffusion in erythrocytes, where it can resolve discrepancies between earlier theories and experiments [4].

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol 1: Calculating Pair Diffusion Coefficients from Molecular Dynamics

Table: Key Parameters for Pair Diffusion Calculations

| Parameter | Specification | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Trajectory Length | Sufficient to observe diffusive regime (typically > tens of ps for AIMD) [5] | Ensures statistical reliability |

| Lag Time Range | Multiple times (Δt, 2Δt, ..., kΔt) [2] | Accounts for time origin uncertainty |

| Spatial Discretization | Bins along r coordinate [2] | Enables construction of propagators |

| Bayesian Optimization | Uniform priors in ln D(ri) and F(ri) [2] | Ensures scale invariance in time and space |

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Generate Trajectories: Perform molecular dynamics simulations to obtain particle pair trajectories [2].

Construct Propagators: Calculate the Green's function G(r, t|r′, 0)dr, which gives the probability for the pair distance to be in (r, r + dr) at time t, starting from r′ at time 0 [2].

Discretize Space and Time: Assign pair distances to corresponding bins along r, and count transitions Nji between bins i and j over lag time Δt [2].

Optimize Diffusion Model: Find pair diffusion coefficients D(r) and free energies F(r) that are consistent with the observed transitions between bins using a Bayesian approach [2].

Validate with Known Systems: Test the procedure using Brownian dynamics simulations of two spherical particles with known diffusion coefficient [2].

Protocol 2: Hybrid MD-Theoretical Approach for Liquid Diffusivity

Methodology Rationale: This approach separates hydrodynamic collective motions from local molecular motions, calculating the former analytically and the latter via MD. This significantly reduces statistical uncertainty compared to large-scale MD [3].

Implementation Steps:

- Perform Small-System MD: Run simulations with less than 100 particles to capture local molecular rearrangements without collective fluctuations [3].

Calculate Molecular Contribution: Extract the local diffusion coefficient (D_L) from the small-system simulation [3].

Compute Hydrodynamic Contribution: Calculate the hydrodynamic term using the relation: ( D\infty = DL + \xi kT/6\pi\eta L ), where ξ is a constant, η is viscosity, and L is system size [3].

Combine Contributions: The hydrodynamic term added to the molecular term provides the complete diffusion coefficient [3].

Validate Approach: Compare results with large-scale MD and experimental data where available [3].

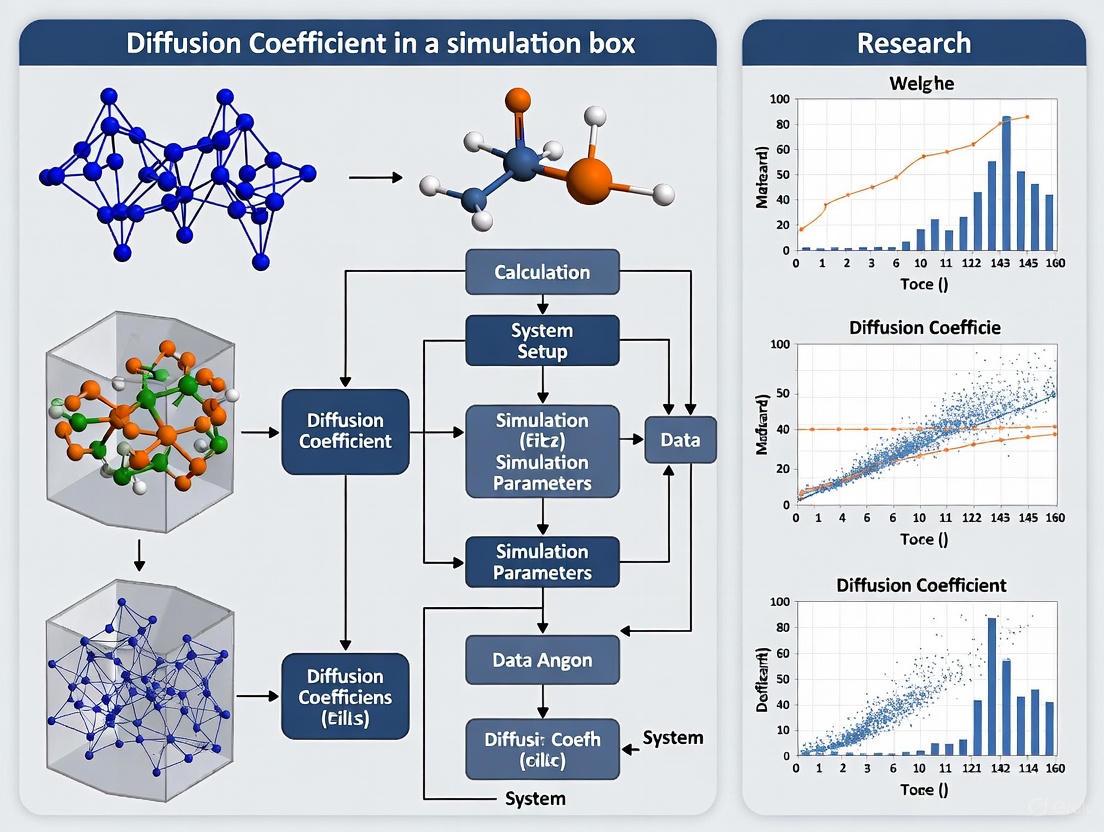

Research Workflow Visualization

Workflow for addressing finite-size effects

The Researcher's Toolkit

Table: Essential Resources for Diffusion Calculations

| Tool/Resource | Function/Purpose | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| SLUSCHI Package [5] | Automated diffusion calculations from first-principles MD | High-throughput screening of materials |

| Bayesian Optimization [2] | Infer D(r) and F(r) from transition counts | Position-dependent pair diffusion |

| Block Averaging [5] | Statistical error estimation for MSD analysis | Quantifying uncertainty in diffusivities |

| Brinkman's Equation [4] | Model hydrodynamics with immobile particles | Membrane protein diffusion |

| Stokes-Einstein Relation [3] | Link diffusivity and viscosity | Liquid systems validation |

| Oseen/Rotne-Prager Tensors [2] | Macroscopic hydrodynamic theory | Large, distant particle pairs |

| Antibiotic-5d | Antibiotic-5d, MF:C13H18N2O4S, MW:298.36 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Maniwamycin B | Maniwamycin B, MF:C10H20N2O2, MW:200.28 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the Yeh-Hummer correction and why is it necessary in molecular dynamics simulations? The Yeh-Hummer (YH) correction is an analytical method to compensate for the artificial system-size dependence of self-diffusion coefficients computed from molecular dynamics (MD) simulations under Periodic Boundary Conditions (PBC). It is necessary because in a typical MD simulation, the number of molecules is orders of magnitude lower than in a real, macroscopic system (the thermodynamic limit). This finite system size, combined with PBC, leads to hydrodynamic self-interactions with periodic images, causing computed diffusivities to be lower than their true, infinite-system values [6]. The YH correction accounts for these finite-size effects, allowing researchers to extrapolate their results to the thermodynamic limit.

Q2: For which types of diffusion coefficients is the Yeh-Hummer correction directly applicable? The Yeh-Hummer correction was derived specifically for self-diffusion coefficients [6] [7]. Self-diffusion describes the motion of a single, tagged particle in a uniform fluid. The correction has also been extended and adapted for other diffusion types. For instance, finite-size effects for rotational diffusion of membrane proteins scale linearly with the ratio of the protein's cross-sectional area to the simulation box area [8]. Furthermore, finite-size effects for Maxwell-Stefan (MS) diffusivities in binary mixtures also exist and depend not only on box size and viscosity but also strongly on the mixture's non-ideality, characterized by the thermodynamic factor [6].

Q3: What is the fundamental physical origin of the finite-size error corrected by the YH method? The error originates from hydrodynamics. In a finite simulation box with PBC, the flow field around a diffusing particle is perturbed by interactions with its own periodic images. This results in additional friction, slowing down the particle's apparent motion compared to its motion in an infinite medium. The YH correction is based on hydrodynamic theory for a spherical particle in a Stokes flow with imposed PBC [6].

Q4: Does the Yeh-Hummer correction depend on the chemical identity or size of the molecules in my system? A key insight from the YH derivation is that the finite-size effect on self-diffusion does not explicitly depend on the size of the molecules or the specific nature of their intermolecular interactions [6]. The correction is a function of the system's overall shear viscosity, temperature, and box size. This means that in a multicomponent mixture, all species experience an identical finite-size effect, though their individual infinite-system self-diffusivities ((D_{i,self}^\infty)) will, of course, differ [6].

Troubleshooting Guide: Applying the Yeh-Hummer Correction

Issue: My corrected diffusion coefficient seems unreasonably large or is positive even when my raw simulated diffusivity is near zero.

- Potential Cause: This can occur in highly viscous systems or mixtures near phase separation (e.g., close to demixing), where the finite-size correction can be larger in magnitude than the simulated diffusivity itself [6].

- Solution:

- Verify System State: Ensure your simulated system is stable and homogeneous. A diffusivity near zero might indicate a glassy state or an unintended phase separation.

- Check Viscosity Calculation: Accurately calculating the shear viscosity ((\eta)) is critical. Use the Green-Kubo method (Equation 3) integrating the stress tensor autocorrelation function from a well-equilibrated trajectory [6].

- Assess Thermodynamic Factor: If working with mutual diffusion, remember that the finite-size effect for MS diffusivities is amplified by the thermodynamic factor ((\Gamma)). A large correction is physically meaningful for highly non-ideal mixtures [6].

Issue: After applying the correction, the agreement with experimental data does not improve.

- Potential Cause 1: Inaccurate calculation of the viscosity ((\eta)) used in the correction term.

- Solution: The viscosity itself must be determined with high precision from an equilibrium MD simulation. Ensure your production run is long enough for the stress tensor autocorrelation to decay fully. Note that the viscosity is independent of system size, so it can be computed from a single simulation [6].

- Potential Cause 2: The system may not be suitable for the standard YH correction.

- Solution: The original YH correction may require rescaling for systems with strong electrostatic interactions, such as ionic solutions or charged molecules in a polar medium [6]. Investigate literature for specialized corrections for these cases.

Issue: My simulation box is not cubic. Can I still apply a finite-size correction?

- Solution: Yes, but the formula is different. The standard YH correction with the constant (\xi = 2.837297) is derived for cubic boxes [6]. Equations for finite-size corrections in non-cubic boxes (e.g., rectangular prisms) have been derived in other studies [6]. You must use the correction formula appropriate for your specific box geometry.

Quantitative Data and Formulas

Core Yeh-Hummer Equation for Self-Diffusion

The formula to extrapolate a self-diffusion coefficient to the thermodynamic limit is:

[ D{i,self}^{\infty} = D{i,self} + D{YH} = D{i,self} + \frac{k_B T \xi}{6 \pi \eta L} ]

Table 1: Variables in the Yeh-Hummer Correction Formula

| Variable | Description | Typical Units |

|---|---|---|

| (D_{i,self}^{\infty}) | Self-diffusion coefficient of species (i) in the thermodynamic limit | m²/s, cm²/s |

| (D_{i,self}) | Self-diffusion coefficient obtained directly from MD simulation | m²/s, cm²/s |

| (D_{YH}) | The Yeh-Hummer finite-size correction term | m²/s, cm²/s |

| (k_B) | Boltzmann constant | 1.380649 × 10â»Â²Â³ J/K |

| (T) | Absolute temperature | Kelvin (K) |

| (\eta) | Shear viscosity of the system | Pa·s (Pascal-second) |

| (L) | Side length of the cubic simulation box | meters (m) |

| (\xi) | Dimensionless constant for cubic PBC | 2.837297 [6] |

Finite-Size Effects for Other Diffusion Types

Table 2: Finite-Size Corrections for Different Diffusion Coefficients

| Diffusion Type | Finite-Size Dependence | Key Additional Parameter(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Self-Diffusion [6] | ( D{i,self}^{\infty} = D{i,self} + \frac{k_B T \xi}{6 \pi \eta L} ) | System viscosity ((\eta)) |

| Rotational Diffusion [8] | ( D{PBC} \approx D0 \left(1 - \frac{\pi R_H^2}{A} \right) ) | Protein hydrodynamic radius ((R_H)), Box area ((A)) |

| Maxwell-Stefan (Mutual) Diffusion [6] | ( \Ä{MS}^{\infty} = \Ä{MS} + \frac{k_B T \Gamma}{6 \pi \eta L} ) | System viscosity ((\eta)), Thermodynamic factor ((\Gamma)) |

Experimental Protocols

Workflow for Applying the Yeh-Hummer Correction

The following diagram illustrates the end-to-end workflow for calculating a size-corrected self-diffusion coefficient, from running the simulation to applying the correction.

Detailed Methodology for Self-Diffusion Coefficient Calculation

This protocol outlines the steps for calculating a self-diffusion coefficient from an MD trajectory, which is the prerequisite for applying the YH correction [7].

System Preparation and Equilibration:

- Force Field: Select an appropriate all-atom force field (e.g., OPLS4 [7]).

- Simulation Cell: Construct a cubic cell with a sufficient number of molecules (e.g., >1000 for a pure liquid [7]) to minimize statistical noise while acknowledging that a finite-size correction will still be needed.

- Equilibration: Perform a multi-stage equilibration process to relax the system and reach the target temperature and pressure. A typical protocol may include:

- Energy minimization and Brownian dynamics at low temperature.

- MD in the NVT ensemble at the target temperature.

- MD in the NPT ensemble at the target temperature and pressure (e.g., 1 atm) for tens of nanoseconds to ensure proper density [7].

Production Simulation:

- Run a production simulation in the NPT or NVE ensemble, saving the trajectory at frequent intervals (e.g., every 1-10 ps). The total simulation time must be long enough to observe Fickian (diffusive) regime in the mean squared displacement (MSD). For liquids, this may require tens to hundreds of nanoseconds, depending on viscosity [7].

Analysis of Self-Diffusion Coefficient ((D_{self})):

- Use the Einstein relation (MSD method) for analysis: ( \displaystyle D{self} = \lim{t \to \infty} \frac{1}{6t} \langle | \mathbf{r}i(t) - \mathbf{r}i(0) |^2 \rangle )

- Calculate the MSD of molecules' centers of mass.

- Average the MSD over all molecules of the same species and over multiple time origins.

- Plot the averaged MSD versus time lag ((t)). The self-diffusion coefficient is one-sixth of the slope of the linear portion of this plot. Perform a linear regression to obtain the slope [7].

Detailed Methodology for Shear Viscosity Calculation

The shear viscosity ((\eta)) required for the YH correction is calculated from equilibrium MD using the Green-Kubo formula, which relates it to the time integral of the stress tensor autocorrelation function [6].

Trajectory Requirement: Use the same production trajectory as for the diffusion analysis.

Stress Tensor Calculation: During the simulation, the code must output the components of the stress tensor P, which includes both kinetic and virial (interaction) contributions.

Green-Kubo Formula: ( \displaystyle \eta = \frac{V}{kB T} \int0^{\infty} \langle P{\alpha\beta}(0) P{\alpha\beta}(t) \rangle dt ) where (V) is the volume, (T) is temperature, and (P_{\alpha\beta}) represents the off-diagonal components of the stress tensor (xy, xz, yz).

Averaging: Calculate the autocorrelation function for each of the three independent off-diagonal components and average them together to improve statistics [6]. The final viscosity is the value of the integral after the correlation function has decayed to zero.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Computational Tools and Parameters for Finite-Size Corrected Diffusion Studies

| Item | Function / Description | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Force Fields | Defines the potential energy function and parameters for molecules. | OPLS4 [7], AMBER, CHARMM. Choice affects accuracy of computed η and D. |

| Water Models | Explicit solvent models for aqueous simulations. | SPC, SPC/E, TIP3P, TIP4P, TIP4P/2005 [7]. Model choice significantly impacts computed diffusivity. |

| Software Packages | Molecular dynamics simulation suites. | Desmond [7], GROMACS, NAMD, LAMMPS. |

| Thermostats & Barostats | Algorithms to control temperature and pressure. | Nose-Hoover thermostat [7], Martyna-Tobias-Klein barostat [7]. Essential for correct NPT ensemble sampling. |

| Long-Range Electrostatics | Methods to handle non-bonded electrostatic interactions. | Particle Mesh Ewald (PME), u-series algorithm [7]. Critical for accuracy in condensed phases. |

| CPW-86-363 | CPW-86-363, CAS:84080-55-7, MF:C17H17N9O7S2, MW:523.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| HSL-IN-1 | HSL-IN-1, MF:C20H12BrF3O3, MW:437.2 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The Interplay of Box Dimension (L), Solvent Viscosity (η), and Temperature (T)

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: How do simulation box dimensions (L) directly impact the calculated self-diffusion coefficient (D) in Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations?

The finite size of the simulation box, particularly under Periodic Boundary Conditions (PBC), systematically reduces the calculated self-diffusion coefficient (DPBC) due to hydrodynamic interactions between a particle and its periodic images [9]. A established correction exists for a cubic box of side length L [9]: Dcorrected = DPBC + 2.84 kB T / (6 π η L) where k_B is Boltzmann's constant, T is temperature, and η is the shear viscosity of the solvent [9]. This finite-size effect becomes negligible for sufficiently large L [9].

Q2: My simulations show different diffusion rates for large box sizes versus small box sizes. Is this a real hydrodynamic effect or an artifact?

This could be a real hydrodynamic effect, but careful controls are needed. A claimed box-size effect on protein conformational stability was challenged by a later study with better statistics [10]. The apparent effect was attributed to a dilution effect: in larger boxes, the average properties (e.g., solvent radial distribution function, diffusion constant) are weighted more heavily by bulk-like water molecules farther from the protein surface [10]. After accounting for this dilution, the intrinsic box-size effect vanished [10]. Always perform multiple replicas to ensure statistical significance [10].

Q3: How does solvent viscosity (η) influence molecular diffusion, and how is it calculated in simulations?

The Stokes-Einstein relation describes the inverse relationship between the translational diffusion coefficient (Dt) and solvent viscosity [11]: Dt = k_B T / (6 π η r), where r is the hydrodynamic radius of the diffusing particle. In simulations, viscosity can be calculated from equilibrium methods using the Green-Kubo formula, which integrates the pressure autocorrelation function, or the Einstein method, which relies on the growth of the stress tensor's mean-squared displacement [12]. For coarse-grained simulations like Dissipative Particle Dynamics (DPD), a revised Einstein formula analogous to the Green-Kubo relation is recommended for reliable viscosity calculation [12].

Q4: Why does my simulated system violate the equipartition theorem, showing different temperatures for different atom subsets?

This can occur when calculating local "kinetic temperatures" for subsets of atoms connected by rigid constraints (e.g., fixed bond lengths) [13]. The degrees of freedom (DoF) are not evenly split between constrained atoms. Incorrectly assigning DoF for a subset that does not include all participants of a constraint leads to a wrong local temperature calculation [13]. A general method to self-consistently evaluate the DoF of atoms under constraints is required for correct local temperature measurement [13].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Erroneous Diffusion Coefficient in Small Simulation Boxes

- Problem: The calculated diffusion coefficient is artificially low and seems dependent on box size.

- Diagnosis: Significant finite-size effect due to hydrodynamic interactions with periodic images.

- Solution:

- Increase Box Size: If computationally feasible, use a larger box size (L) so that the correction term becomes negligible [9].

- Apply Analytical Correction: Use the Yeh-Hummer correction formula:

D_corrected = D_PBC + 2.84 k_B T / (6 π η L)[9]. This requires an independent measurement or estimate of the solvent viscosity (η). - Verify Convergence: Check that the Mean Squared Displacement (MSD) is linear with time (the diffusive regime) before calculating D [9].

Issue: Inconsistent Local Temperatures with Rigid Constraints

- Problem: When using algorithms like SHAKE or LINCS to constrain bonds, different atom groups show different kinetic temperatures.

- Diagnosis: The number of degrees of freedom (DoF) for the atom subset is incorrectly calculated [13].

- Solution:

- Identify All Constraints: List all geometric constraints acting on the atoms within your subset of interest and those connecting to atoms outside it [13].

- Apply Correct DoF Calculation: Do not simply subtract one DoF per constraint from the subset. Use a method that self-consistently evaluates the DoF for atoms subjected to partial constraints [13].

- Re-calculate Local Temperature: Use the correctly calculated

d_Sin the temperature formula:T_S = 1/(2 d_S k_B) * ⟨ Σ m_j v_j² ⟩[13].

Issue: High Uncertainty in Viscosity Calculation from DPD Simulations

- Problem: Equilibrium calculation of viscosity (η) in Dissipative Particle Dynamics (DPD) simulations has poor statistical accuracy.

- Diagnosis: The standard Green-Kubo (GK) method suffers from large fluctuations in the pressure tensor elements in DPD [12].

- Solution:

- Use the Einstein Method: Switch to the Einstein-Helfand approach for calculating viscosity. It often requires shorter trajectories to achieve the same statistical accuracy as the GK method in DPD [12].

- Employ a Revised Formula: Use a revised Einstein expression derived to be analogous to the updated GK formula for DPD, which provides more robust results [12].

- Run Multiple Independent Simulations: Aggregate results from several independent runs to improve statistics [12].

Quantitative Data Tables

Table 1: Finite-Size Correction for Diffusion Coefficient in Water at 298 K

This table illustrates the magnitude of the correction term for a typical SPC water model (η ~ 0.00075 Pa·s) [9] [10].

| Box Length, L (nm) | Correction Term (10â»â¹ m²/s) | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 5.0 | ~10.0 | Significant correction required |

| 7.5 | ~6.7 | Correction still substantial |

| 10.0 | ~5.0 | Standard box size; correction needed |

| 15.0 | ~3.3 | Correction is smaller |

Table 2: Impact of DPD Simulation Parameters on Viscosity and Dynamics

Based on a study of polymer solutions using DPD, varying conservative (aij) and friction (γij) parameters affects solvent quality and viscosity [12].

| Parameter Set (aij, γij) | Effect on Solvent Quality | Effect on Bulk Solvent Viscosity | Schmidt Number |

|---|---|---|---|

| (15, 4.5) | Poor solvent | Lower | Compatible with fluid |

| (20, 4.5) | Intermediate | Medium | Compatible with fluid |

| (25, 4.5) | Good solvent (athermal) | Higher | Compatible with fluid |

| (25, 5.0) | Good solvent (athermal) | Increases | Compatible with fluid |

| (25, 10.0) | Good solvent (athermal) | Increases further | Compatible with fluid |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Calculating Translational Diffusion Coefficient via Mean Squared Displacement (MSD)

- Principle: In the diffusive regime, the MSD of particles grows linearly with time. The slope is related to the diffusion coefficient [9].

- Steps:

- Simulation: Run a well-equilibrated MD simulation in the NVT or NPT ensemble.

- Trajectory Processing: Use a tool like

gmx msdin GROMACS or a custom script to calculate the MSD [9]:MSD(t) = ⟨ | r(t + t₀) - r(t₀) |² ⟩where the average ⟨⟩ is over all molecules and time origins (t₀). - Ensure Linear Regime: Plot MSD(t) vs. t on a log-log scale to identify the ballistic regime (slope ~2) and the diffusive regime (slope ~1). Use only the linear part of the MSD curve in the diffusive regime for fitting [9].

- Fit and Calculate: For 3D systems, fit

MSD(t) = 6 D tto the linear region. The slope gives6D, soD = slope / 6[9]. - Correct for Finite Size: Apply the Yeh-Hummer correction using the box size (L) and solvent viscosity (η) [9].

Protocol 2: Analyzing Rotational Diffusion from MD Trajectories

- Principle: The reorientation of a vector fixed to a molecule can be characterized by a time correlation function, which decays exponentially with a time constant related to the rotational diffusion coefficient [11].

- Steps:

- Define Vectors: Define one or more unit vectors fixed in the molecule's frame of reference (e.g., inter-atomic vectors, dipole moment vector).

- Calculate Correlation Function: For each vector u(t), compute the second-order Legendre polynomial time correlation function:

C(t) = ⟨ P₂( u(t) · u(0) ) ⟩ = ⟨ (3cos²θ(t) - 1)/2 ⟩, where θ(t) is the angle through which the vector has rotated in time t [11]. - Fit Correlation Function: Fit

C(t)to a single or multi-exponential decay. For a simple decay,C(t) = exp(-t / τ_R), whereτ_Ris the rotational correlation time [11]. - Calculate Coefficient: The rotational diffusion coefficient (D_r) is obtained from

D_r = 1 / (6 Ï„_R)for a spherical particle [11]. More complex analysis using a full diffusion tensor can be performed for anisotropic molecules [11].

Workflow and Relationship Diagrams

Diagram 1: Workflow for accurate diffusion coefficient calculation, showing the interplay of key parameters L, T, and η.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Software Tools for Diffusion and Viscosity Analysis

| Tool Name | Function | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| GROMACS | MD Simulation Suite | Includes built-in tool gmx msd for straightforward MSD and diffusion coefficient calculation [9]. |

| DL_MESO | Mesoscale Simulation Package | Used for running Dissipative Particle Dynamics (DPD) simulations and calculating properties like viscosity [12]. |

| HYDROPRO | Hydrodynamic Modeling | Calculates rotational diffusion coefficients and other hydrodynamic properties from atomic structures [11]. |

| CHARMM | MD Simulation Program | Used for complex biomolecular simulations with advanced constraint algorithms and analysis [11] [10]. |

| NAMD | MD Simulation Program | Often used for system equilibration and production runs of large biomolecular systems [11]. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Diagnosing and Resolving Box Size-Related Errors in Diffusion Calculations

Problem: Inconsistent or physically implausible diffusion coefficients (D*) across simulation runs.

Primary Symptoms: High statistical uncertainty in Mean Squared Displacement (MSD) slopes and poor convergence of results.

| Error Type | Key Characteristics | Impact on Diffusion Coefficient (D*) |

|---|---|---|

| Systematic Error [14] | • Consistent bias in results.• Does not average out with more sampling.• Caused by fundamental flaws in setup. | • Inaccurate Accuracy: Predicts a value that is consistently higher or lower than the true value.• Example: Finite-size effects from a box that is too small cause underestimated D*. |

| Random Error [14] | • Unpredictable variations around true value.• Can be reduced with increased sampling.• Caused by stochastic nature of simulation. | • Imprecise Precision: Results in a high degree of uncertainty or a wide confidence interval around the estimated value.• Example: Insufficient trajectory length for a given box size leads to high statistical noise in D*. |

Step-by-Step Resolution:

- Run a Box Size Convergence Test: Perform identical simulations, varying only the box size (e.g., from 2 nm to 10 nm).

- Plot Results: Create a plot of the calculated

D*(with error bars) versus the inverse box size (1/L). - Diagnose: If

D*shows a clear trend versus1/L, systematic error from finite-size effects is significant. If error bars are large and overlap but show no trend, random error from insufficient sampling is the primary issue. - Mitigate Systematic Error: Select a box size from the plateau region of the convergence test where

D*becomes independent of box size. - Mitigate Random Error: For the chosen box size, increase the simulation time to improve the convergence of the MSD.

Guide 2: Optimizing Simulation Parameters for Reliable Diffusivity

Problem: How to choose a simulation box size that balances computational cost and result reliability. Key Trade-off: Larger boxes reduce systematic finite-size errors but increase computational cost per timestep, potentially leading to shorter trajectories and higher random errors for a given computational budget.

Recommended Protocol:

- Initial Scan: Conduct shorter simulations with different box sizes to identify the minimum size where properties (like

D*) converge. - Production Run: Use the identified minimum stable box size.

- Maximize Sampling: For this box size, run the longest affordable trajectory to minimize statistical uncertainty. Using advanced analysis methods like Bayesian regression or block averaging can provide more robust error estimates from a single long trajectory [5] [15].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the practical difference between a systematic and a random error in my diffusion simulation? A: A systematic error is a consistent bias. For example, if your simulation box is too small, it artificially constrains atomic motion, and you will always calculate a diffusion coefficient that is too low, no matter how long you run the simulation. A random error is statistical noise. If your simulation is too short, the calculated diffusion coefficient will scatter around the true value, and this scatter will decrease as you collect more data [14].

Q2: My calculated diffusion coefficient has very large error bars. Is this a box size problem? A: Not necessarily. Large error bars primarily indicate high random error. This is typically solved by extending the simulation time to improve sampling, not by changing the box size. However, if you are forced to use a very small box that causes anomalous diffusion, it can also manifest as unstable or wildly varying results [15] [16].

Q3: How does using a larger simulation box help reduce errors? A: A larger box primarily reduces systematic errors by minimizing finite-size effects. It provides a more realistic representation of a bulk system by reducing the artificial correlation between periodic images and allowing for a more complete spectrum of collective density fluctuations. This leads to a more accurate value for the diffusion coefficient.

Q4: Are there any downsides to using a very large box? A: Yes. For a fixed computational budget, a larger box size means you can afford fewer atoms or a shorter simulation time. This can lead to increased random error because the MSD has less time to evolve into the linear, diffusive regime, and you have fewer atomic trajectories to average over, resulting in noisier statistics [5].

Q5: What analysis methods are best for quantifying the uncertainty in my calculated diffusion coefficient? A: Avoid simple Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) for fitting the MSD, as it significantly underestimates the true uncertainty [15]. Preferred methods include:

- Block Averaging: A robust method implemented in packages like SLUSCHI to quantify statistical error [5].

- Bayesian Regression: A statistically efficient method that provides a accurate posterior distribution for

D*and its uncertainty, as implemented in thekinisipackage [15].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Detailed Methodology for Diffusion Coefficient Calculation

The following workflow, based on first-principles molecular dynamics, is used to calculate diffusion coefficients with quantified uncertainty [5].

Key Formula:

The self-diffusion coefficient for species α is obtained from the MSD using the Einstein-Smoluchowski relation:

D_α = 1/(2d) * d(MSD_α(t))/dt where d=3 is the dimensionality [5].

Uncertainty Quantification:

The uncertainty in D_α is determined using block averaging [5] or advanced methods like Bayesian regression, which models the MSD data as a multivariate normal distribution to accurately capture the statistical uncertainty from a single trajectory [15].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Computational Materials for Diffusion Studies

| Item Name | Function / Relevance |

|---|---|

| SLUSCHI-Diffusion [5] | An automated workflow package for performing AIMD calculations and post-processing trajectories to compute MSD and extract diffusivities with robust error estimates. |

| VASP [5] | A first-principles molecular dynamics code used to perform the underlying quantum-mechanical force calculations and generate the atomic trajectory data. |

| kinisi [15] | An open-source Python package that implements a Bayesian regression method for estimating diffusion coefficients with near-maximal statistical efficiency and accurate uncertainty. |

| Generalized Least-Squares (GLS) [15] | A statistically efficient regression method that accounts for the correlated and heteroscedastic nature of MSD data, providing optimal estimates when the covariance matrix is known. |

| Lavendomycin | Lavendomycin, MF:C29H50N10O8, MW:666.8 g/mol |

| Camaric acid | Camaric acid, MF:C35H52O6, MW:568.8 g/mol |

Table: Influence of Simulation Parameters on Error Types

| Parameter | Primary Error Type Influenced | Effect if Parameter is Too LOW | Effect if Parameter is Too HIGH |

|---|---|---|---|

| Box Size (L) | Systematic [14] | • Finite-size effects.• Artificially constrained dynamics.• Underestimation of D*. | • Increased computational cost per step.• Potential for increased random error if trajectory length is shortened. |

| Trajectory Length (t) | Random [14] [15] | • Poor sampling of diffusive regime.• Noisy, non-linear MSD.• Large uncertainty in D*. | • Increased computational time.• Diminishing returns on uncertainty reduction. |

| Number of Particles (N) | Both | • Larger random error (poorer averages).• Potentially larger systematic error. | • Increased computational cost.• May require longer trajectory to equilibrate. |

From Theory to Practice: Methodologies for Robust Diffusion Calculations

In the calculation of diffusion coefficients from molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, two principal methods emerge: the Mean Squared Displacement (MSD) and the Velocity Autocorrelation Function (VACF). Both techniques are rooted in statistical mechanics and provide a bridge between microscopic particle motion and macroscopic transport properties, yet they differ significantly in their practical application, robustness, and susceptibility to common simulation artifacts. Within the specific context of research aimed at optimizing simulation box size, understanding the nuances, advantages, and limitations of each method is paramount for obtaining accurate and reliable results. This guide provides a detailed comparison and troubleshooting resource for researchers employing these core techniques [17] [18].

Core Theoretical Foundations

The Mean Squared Displacement (MSD) and the Velocity Autocorrelation Function (VACF) are both derived from the statistical mechanics of random walks and provide equivalent measures of the diffusion coefficient in the long-time limit, though they probe the dynamics in different ways [18] [19].

Mean Squared Displacement (MSD): The MSD measures the deviation of a particle's position over time relative to a reference position. For a particle in three dimensions, the MSD is defined as:

MSD(t) = ⟨|r(t) - r(0)|²⟩wherer(t)is the position vector at timet, and the angle brackets denote an ensemble average. The diffusion coefficientDis then obtained from the long-time slope of the MSD:D = (1/(6)) * lim_(t→∞) d(MSD(t))/dt[17] [5] [20]Velocity Autocorrelation Function (VACF): The VACF measures how a particle's velocity correlates with itself over time. It is defined as:

VACF(t) = ⟨v(0) · v(t)⟩wherev(t)is the velocity vector at timet. The diffusion coefficient is calculated by integrating the VACF:D = (1/3) ∫_0^∞ ⟨v(0) · v(t)⟩ dt[18] [20] [19]

A key insight is that these two quantities are fundamentally linked mathematically. The MSD can be expressed as a double time integral of the VACF [18] [19]:

⟨|r(t) - r(0)|²⟩ = 2 ∫_0^t (t - s) ⟨v(0) · v(s)⟩ ds

Table 1: Summary of Core Theoretical Definitions.

| Feature | Mean Squared Displacement (MSD) | Velocity Autocorrelation Function (VACF) |

|---|---|---|

| Core Definition | ⟨ |r(t) - r(0)|² ⟩ | ⟨v(0) · v(t)⟩ |

| Formula for D | ( D = \frac{1}{6} \lim_{t\to\infty} \frac{d}{dt} \text{MSD}(t) ) | ( D = \frac{1}{3} \int_0^{\infty} \text{VACF}(t) dt ) |

| Primary Insight | Explores the spatial extent of random motion. | Reveals the time scale over which a particle "remembers" its initial velocity. |

Comparative Analysis: MSD vs. VACF

For researchers determining the optimal method for their specific system, a direct comparison of practical considerations between MSD and VACF is essential.

Table 2: Practical Comparison for Method Selection.

| Aspect | MSD Method | VACF Method |

|---|---|---|

| Ease of Use & Robustness | Generally more robust; linear regression on MSD is less sensitive to noise [21]. | Integration can be noisy; sensitive to the choice of the upper limit (cutoff time) [21] [20]. |

| Handling of Systematic Forces | Biased by systematic forces (e.g., in confined systems like ion channels), potentially yielding unreliable D [22]. | The integral can be influenced by slow decays or oscillations, making the plateau value difficult to identify [18]. |

| Statistical Convergence | Requires long simulation times to reduce uncertainty in the slope [18]. | Can require extensive sampling (e.g., tens of nanoseconds) for convergence in complex systems [22]. |

| Finite-Size Effects | Diffusion coefficient depends on supercell size unless the supercell is very large [20]. | Also subject to finite-size effects, as it samples the same underlying dynamics [18]. |

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Standard Protocol for MSD Analysis

- Trajectory Production: Run a sufficiently long MD simulation in the NVT or NPT ensemble after proper equilibration. Ensure the trajectory is saved with adequate frequency [5] [20].

- Trajectory Parsing: Extract unwrapped atomic coordinates. Wrapped coordinates from periodic boundary conditions must be "unwrapped" to ensure continuous particle paths [5].

- MSD Calculation: Compute the MSD for each species. For better statistics, use a time-averaging approach:

MSD(Δt) = (1/(N-Δt)) Σ_{t₀=1}^{N-Δt} (1/M) Σ_{i=1}^M |r_i(t₀+Δt) - r_i(t₀)|²where the average is over all time originst₀and allMparticles of the same species [17] [5]. - Linear Fitting: Plot MSD(Δt) versus Δt. Identify the linear (diffusive) regime and perform a linear fit. The diffusion coefficient is

D = slope / 6in 3D [20].

Standard Protocol for VACF Analysis

- Velocity Data Collection: During the MD production run, save atomic velocities at a high frequency (small time interval). This requires a smaller sampling interval than for MSD analysis [20].

- VACF Calculation: For each particle, compute

VACF(τ) = (1/(T-τ)) Σ_{t=0}^{T-τ} v(t) · v(t+τ). Average this result over all particles of the same species [23]. - Integration: Integrate the averaged VACF from time zero to a time

t_maxwhere the VACF has decayed to zero or shows only random fluctuations around zero:D = (1/3) ∫_0^{t_max} VACF(τ) dτ[18] [20]. - Cutoff Selection: The choice of

t_maxis critical. It should be long enough to capture the full decay but not so long that it includes excessive noise [21].

Troubleshooting Common Issues

Problem: Inconsistent or Drifting Diffusion Coefficient with Simulation Box Size

- Issue: The calculated diffusion coefficient

Dchanges significantly when the simulation box size is varied. - Solution: This is a known finite-size effect. To address this:

- Perform simulations for progressively larger supercells.

- Plot

Dagainst the inverse of the box size (1/L). - Extrapolate the calculated diffusion coefficients to the "infinite supercell" limit (

1/L → 0) [20].

Problem: MSD Curve is Not Linear

- Issue: The MSD vs. time plot does not show a clear linear regime, making it impossible to fit a slope.

- Solutions:

- Short-time non-linearity: At very short times, motion is ballistic (MSD ∠t²), not diffusive. Ensure you are analyzing the MSD at sufficiently long time lags where the plot becomes linear [19].

- Insufficient sampling: Run a longer simulation to improve statistics and reach the diffusive regime. For solids with very low diffusion, the MSD may never become truly linear, indicating a nearly zero diffusion coefficient [24].

- Sub-diffusion or Super-diffusion: If the MSD is non-linear over long times, your system may not exhibit normal diffusion. The MSD plot itself provides this diagnostic information, which is an advantage of the method [21].

Problem: VACF Integral Does Not Converge

- Issue: The integral of the VACF, and thus the calculated

D(t), does not reach a stable plateau value. - Solutions:

- Noisy VACF at long times: Truncate the integral at the point where the VACF first decays to zero or starts oscillating around zero. Integrating further only adds noise [21].

- Long-tailed correlations: In some complex systems, correlations can persist for a long time. This requires extensive sampling (e.g., tens of nanoseconds) to achieve convergence [22].

- Check the VACF shape: An exponentially decaying VACF is easier to integrate than one with oscillations. Visually inspect the VACF to determine a reasonable cutoff [21].

Problem: Large Statistical Errors in Calculated D

- Issue: The diffusion coefficient has large error bars, even from a single long trajectory.

- Solutions:

- Use Block Averaging: For MSD analysis, split the trajectory into several blocks, calculate

Dfor each block independently, and report the average and standard deviation [5]. - Increase Averaging: For the VACF method, averaging over all identical particles in the system improves statistics (

N^(-1/2)scaling) [18]. - Run Longer Simulations: The standard error decreases with the square root of the simulation length

Tor the number of independent samplesN[18].

- Use Block Averaging: For MSD analysis, split the trajectory into several blocks, calculate

Table 3: Key Software and Analysis Tools.

| Tool / "Reagent" | Function / Purpose | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| MD Simulation Engine (e.g., LAMMPS, VASP, AMS) | Generates the fundamental data: atomic trajectories and velocities. | Performing the NPT production run to simulate system dynamics [5] [20]. |

| Unwrapped Trajectory | A processed trajectory where atomic positions are corrected for periodic boundary crossings. | Essential for a correct MSD calculation in simulations with Periodic Boundary Conditions (PBCs) [5]. |

| Time-Averaging Algorithm | A script or function to compute MSD/VACF by averaging over all possible time origins within a trajectory. | Drastically improves the statistical quality of the MSD/VACF from a single long simulation [17] [24]. |

| Block Averaging Script | A post-processing routine to quantify statistical uncertainty by splitting data into independent blocks. | Providing reliable error estimates for the calculated diffusion coefficient [5]. |

| SLUSCHI-Diffusion / VASPKIT | Automated workflow packages for parsing trajectories and computing MSD/VACF. | High-throughput or automated diffusion analysis from VASP MD outputs [5]. |

Key Concepts and the Importance of Box Size

The self-diffusion coefficient ((D)) quantifies the random, thermally-driven motion of particles in a fluid. In Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations, it is most commonly calculated from the mean-squared displacement (MSD) using the Einstein relation: [ D = \frac{1}{2d} \lim_{t\to\infty} \frac{d}{dt} \langle | \mathbf{r}(t) - \mathbf{r}(0) |^2 \rangle ] where (d) is the dimensionality (3 for 3D systems), (\mathbf{r}(t)) is the position of a particle at time (t), and the angle brackets denote an average over all particles of the same species and over multiple time origins [9] [5].

The choice of simulation box size is critical because the diffusion coefficient calculated in a simulation with Periodic Boundary Conditions ((D{PBC})) is systematically lower than the true, infinite-system value ((D{\infty})) due to hydrodynamic interactions with periodic images [8] [3]. For a cubic box of side length (L), this finite-size effect can be corrected using the Yeh-Hummer relation [9]: [ D{\infty} = D{PBC} + \frac{2.84 kB T}{6 \pi \eta L} ] where (kB) is Boltzmann's constant, (T) is temperature, and (\eta) is the shear viscosity of the solvent. This correction can be significant, and its application allows for accurate results from smaller, more computationally efficient simulations [3].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why does the diffusion coefficient I calculate depend on the size of my simulation box? The finite-size effect arises from artificial viscous drag caused by hydrodynamic interactions between a diffusing particle and its periodic images [8] [9]. A smaller box means images are closer, leading to stronger interactions and a slower apparent diffusion. The Yeh-Hummer correction accounts for this effect [9].

Q2: What is the difference between calculating diffusivity via MSD versus the velocity autocorrelation function (VACF)?

- MSD Method: (D) is obtained from the slope of the MSD versus time in the diffusive regime. This is generally more straightforward and is the recommended method [20] [9].

- VACF Method: (D) is calculated from the integral of the velocity autocorrelation function: (D = \frac{1}{3} \int_{0}^{\infty} \langle \mathbf{v}(0) \cdot \mathbf{v}(t) \rangle dt) [20] [9]. This method can be more sensitive to statistical noise and requires a high sampling frequency [20].

Q3: How long does my production simulation need to be to get a reliable diffusivity? Your simulation must be long enough to clearly reach the diffusive regime, where the MSD plot becomes a straight line. At short times, motion is often ballistic (MSD ~ (t^2)). The time required to reach the diffusive regime depends on the system; for lipids in a bilayer, it can take nanoseconds [9]. Always plot the MSD and its slope to ensure convergence.

Q4: I see a warning about "lost atoms" in LAMMPS. What should I do?

This often indicates atoms are moving too fast, potentially due to high energy from a bad initial structure, a timestep that is too large, or atoms being too close. Do not simply ignore the error with thermo_modify lost ignore [25]. Solutions include running an energy minimization, using fix nve/limit to cap maximum displacement, or temporarily reducing the timestep with fix dt/reset [25].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Non-Linear or Non-Converging MSD

- Symptoms: The MSD versus time curve is not a straight line, or the calculated (D) value keeps changing as the simulation length increases.

- Solutions:

- Extend Simulation Time: The most common cause is an insufficiently long simulation. Run a longer production trajectory to properly sample the diffusive regime.

- Check Equilibration: Ensure your system is fully equilibrated (energy, density, pressure stable) before starting production. Collecting MSD during equilibration will give spurious results.

- Improve Sampling: For a single solute molecule, the statistics can be poor. If possible, simulate multiple solute molecules or run several independent simulations and average the results [9] [26].

Problem 2: Simulation Crashes or Instabilities

- Symptoms: Simulation crashes with errors like "Bond/angle too long," "Atoms lost," or forces/energy becoming "NaN" or "Inf."

- Solutions:

- Energy Minimization: Always perform thorough energy minimization before equilibration to remove high-energy contacts.

- Check Timestep: Use a timestep small enough for your force field and the fastest motions in your system (e.g., 1-2 fs for atomistic models with explicit bonds to hydrogen).

- Visualize the Trajectory: Use visualization tools (e.g., VMD, PyMOL) to inspect the system just before the crash to identify the source of the problem, such as a single "hot" atom [25].

Problem 3: Incorrect Finite-Size Correction

- Symptoms: The corrected diffusion coefficient (D_{\infty}) seems physically unreasonable after applying the Yeh-Hummer formula.

- Solutions:

- Verify Viscosity: The accuracy of the correction depends on an accurate value for the solvent shear viscosity ((\eta)). Consider calculating (\eta) from the same simulation or using a reliable experimental value.

- Check Box Size (L): Ensure you are using the correct box length for a cubic box. For non-cubic boxes, an effective length (L = V^{1/3}) is typically used, but more advanced corrections may be needed [8].

- Multiple Box Sizes: The most robust approach is to run simulations at several different box sizes, plot (D{PBC}) versus (1/L), and extrapolate the linear fit to (1/L = 0) to obtain (D{\infty}) [9].

Problem 4: GROMACSpdb2gmxErrors

- Symptom:

pdb2gmxfails with "Residue 'XXX' not found in residue topology database." - Solution: The force field you selected does not contain parameters for your molecule. You can try renaming the residue if the nomenclature is wrong, using the

-terflag to properly specify terminal residues, or generating a topology for the ligand/molecule using another tool and manually incorporating it into your system topology [27].

Workflow Diagram

The following diagram summarizes the complete workflow for calculating diffusion coefficients, integrating system setup, finite-size considerations, and analysis.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Essential Software and Tools for MD Diffusion Studies

| Tool Category | Example Software | Primary Function in Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| MD Simulation Engine | GROMACS, LAMMPS, NAMD, AMBER | Performs the numerical integration of Newton's equations of motion to generate the molecular trajectory. |

| Force Field | CHARMM, AMBER, OPLS-AA, GAFF | Provides the analytical potential energy functions and parameters that define interatomic interactions. |

| Analysis Suite | VMD, MDAnalysis, VASPKIT, GROMACS tools | Processes MD trajectories to compute properties like MSD, VACF, and diffusion coefficients. |

| Visualization Software | VMD, PyMOL | Crucial for inspecting system structure, diagnosing crashes, and visualizing molecular motion [25]. |

| Ab-initio MD Suite | VASP, Quantum ESPRESSO | For first-principles MD (AIMD) where interatomic forces are computed from electronic structure theory [5]. |

Experimental Protocols

Methodology: Calculating Diffusion Coefficients via MSD Analysis

This protocol outlines the standard procedure for obtaining self-diffusion coefficients from an MD trajectory [20] [9].

System Preparation and Equilibration:

- Construct the initial configuration of your molecule(s) in a solvent box with periodic boundary conditions.

- Run a series of simulations to equilibrate the system:

- Energy Minimization: Use steepest descent or conjugate gradient to remove bad contacts.

- NVT Equilibration: Fix the particle number (N), volume (V), and temperature (T) using a thermostat (e.g., Berendsen, Nosé-Hoover) to stabilize the temperature.

- NPT Equilibration: Fix the particle number (N), pressure (P), and temperature (T) using a thermostat and barostat to achieve the correct density.

Production MD:

- Run a long MD simulation in the NVT or NPT ensemble, saving the atomic positions (trajectory) and velocities at regular intervals. Ensure the sampling frequency is high enough for VACF analysis if needed [20].

Trajectory Analysis - MSD Calculation:

- Use the production trajectory. For accurate results, use "unwrapped" coordinates to track true atomic displacements across periodic boundaries [5].

- For each species (\alpha), compute the MSD as a function of time: [ MSD{\alpha}(t) = \frac{1}{N{\alpha}} \sum{i \in \alpha} \langle | \mathbf{r}i(t0 + t) - \mathbf{r}i(t0) |^2 \rangle{t0} ] where the average is over all atoms (i) of species (\alpha) and over all possible time origins (t0) [9].

Extracting the Diffusion Coefficient:

- Plot (MSD(t)) versus (t). Identify the linear (diffusive) regime where the slope is constant.

- Perform a linear fit to the MSD in this regime. The self-diffusion coefficient is given by: [ D_{PBC} = \frac{1}{6} \times \text{slope} \quad \text{(for 3D systems)} ]

Applying Finite-Size Correction:

Methodology: Advanced Workflow for High-Throughput Calculations

For high-throughput studies, such as with the SLUSCHI package, the workflow is streamlined and automated [5]:

- Input Preparation: Provide standard first-principles input files (e.g., INCAR, POSCAR, POTCAR for VASP) and a control file (

job.in) specifying temperature, pressure, and supercell size. - Automated Execution: The workflow automatically launches the MD simulation in a designated volume search directory (

Dir_VolSearch). - Automated Post-Processing: After the MD run, a script (

diffusion.csh) is invoked to:- Parse the output (e.g., OUTCAR) to extract unwrapped atomic trajectories.

- Compute species-resolved MSD.

- Extract (D_{PBC}) using the Einstein relation and perform block averaging for robust error estimation [5].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

GROMACS Workflow Issues

Q1: I encounter the error "Residue ‘XXX’ not found in residue topology database" when running pdb2gmx. What are my options?

A: This error means the force field you selected does not contain topology parameters for the residue 'XXX'. Your options are, in order of practicality [28]:

- Check for naming conventions: Rename the residue in your PDB file to match the exact name used in the force field's database.

- Find a topology: Search the literature or online repositories for a pre-existing topology file (.itp) for the molecule and include it manually in your system's topol.top file.

- Switch force fields: Use a different force field that already includes parameters for your residue.

- Parameterize the residue yourself: This is a complex and advanced task requiring significant expertise to derive the necessary bonded and non-bonded parameters.

Q2: During energy minimization or equilibration, my simulation "blows up" (crashes with extreme forces). What are the common causes and fixes?

A: A simulation explosion often indicates a poor starting structure or incorrect parameters. Follow this systematic troubleshooting guide [29]:

- Thoroughly minimize: Perform energy minimization until the maximum force (

Fmax) is below a reasonable threshold (e.g., 1000 kJ/mol/nm). - Use position restraints: Restrain the heavy atoms of your solute (protein, ligand) during initial equilibration to allow the solvent and ions to relax around it. This is typically done using an

#include "posre.itp"statement in your topology. - Check your box size and solvent: Ensure your simulation box is large enough and that you have properly neutralized the system with ions.

- Review topology: Double-check for missing atoms, incorrect charges, or other errors in your molecular topology.

- Reduce the timestep: Temporarily use a smaller integration timestep (e.g., 0.5 fs or 1 fs) during initial equilibration, especially if your system contains stiff bonds.

Q3: grompp fails with "Invalid order for directive defaults". What does this mean?

A: This error occurs when the directives in your topology (.top) or include (.itp) files are in the wrong order. GROMACS requires a specific sequence [28]. The [ defaults ] directive must be the first in the topology. Crucially, all [ *types ] directives (like [ atomtypes ]) must appear before any [ moleculetype ] directive. This error is common when manually adding new molecule topologies; ensure you place the #include statement for new molecules' .itp files after the force field has been fully defined.

Q4: I get an error about "non-integral time" when running gmx msd. How can I resolve this?

A: This is a known issue in older versions of GROMACS where the gmx msd tool required trajectory time points to be integers [30]. The solution is to subsample your trajectory to a 1 ps interval (or other integer intervals) using the gmx convert-trj command:

Then, use the new prod_sub.xtc file for your MSD analysis. This issue is resolved in the GROMACS 2025-beta version.

VASP and SLUSCHI Workflow Issues

Q5: My VASP calculation stops with an HDF5 error related to a missing KPOINTS file. What is the problem?

A: This is a known issue in certain VASP versions. The code attempts to write a KPOINTS file to the HDF5 output, but fails if the file is not present [31]. You can resolve this by:

- Providing a KPOINTS file: Ensure a valid KPOINTS file is in your run directory.

- Modifying the source code (Advanced): As a last resort, you can comment out the problematic

vh5_dump_original_to_h5call related to KPOINTS in the VASP source filevhdf5.F.

Q6: What is the core principle behind calculating diffusion coefficients in automated workflows like SLUSCHI-Diffusion?

A: The core principle is the Einstein-Smoluchowski relation for Brownian motion. Automated workflows parse the atomic trajectories from molecular dynamics (MD) simulations to compute the Mean Squared Displacement (MSD) for each atomic species. The self-diffusion coefficient (D_α) is then calculated from the slope of the MSD versus time plot in the linear, diffusive regime [5] [32]:

D_α = (1/(2d)) * (d(MSD)/dt), where d=3 for 3-dimensional diffusion.

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Resolving Commonpdb2gmxErrors

This guide addresses frequent failures when generating molecular topologies.

Problem: Long bonds and/or missing atoms error.

- Solution: Check the

pdb2gmxscreen output for the identity of the missing atom. Add missing atoms to your PDB file using modeling software before runningpdb2gmxagain [28].

- Solution: Check the

Problem: WARNING: atom X is missing in residue XXX.

- Solution:

- If missing hydrogens, use the

-ignhflag to ignore all hydrogens in the input and letpdb2gmxadd them correctly. - For terminal residues in AMBER force fields, ensure they are prefixed with 'N' or 'C' (e.g., 'NALA' for an N-terminal alanine) [28].

- Check your PDB file for

REMARK 465andREMARK 470entries, which indicate missing atoms that must be modeled externally.

- If missing hydrogens, use the

- Solution:

Problem: Atom X in residue YYY not found in rtp entry.

- Solution: This is typically a naming mismatch. Rename the atom in your coordinate file to match the name defined in the force field's residue topology database (.rtp file) [28].

Guide 2: Optimizing Diffusion Coefficient Calculations

Accurate diffusion coefficients require careful setup and analysis to ensure the MSD is in the correct regime.

Step 1: Ensure Adequate Sampling.

- Your production MD trajectory must be long enough to capture diffusive motion. The rule of thumb is that the simulation length should be at least 10 times the characteristic diffusion time.

Step 2: Identify the Linear MSD Regime.

- The MSD plot has three typical regions: a ballistic regime at short times, a transitional regime, and a linear diffusive regime at long times. Fitting must be performed only in the linear regime. Automated tools like SLUSCHI-Diffusion and VASPKIT include diagnostics to help identify this region [5].

Step 3: Use Proper fitting Parameters.

- In

gmx msd, use the-beginfitand-endfitoptions to define the time range for linear regression. If both are set to-1, the tool will automatically fit from 10% to 90% of the total time [33]. - For robust error estimation, use the

-molflag, which calculates a diffusion coefficient for each molecule, providing statistics for an accurate error estimate [33].

- In

Step 4: Manage Memory and Performance.

- For long/large trajectories,

gmx msdcan be slow and run out of memory. Use the-maxtauoption to cap the maximum time delta for MSD calculation, which improves performance and avoids memory errors [33].

- For long/large trajectories,

The table below summarizes key parameters for diffusion calculations in GROMACS and SLUSCHI.

Table 1: Key Parameters for Diffusion Coefficient Calculations

| Tool | Critical Parameter | Function | Recommended Setting |

|---|---|---|---|

gmx msd |

-beginfit / -endfit |

Defines time range for linear fit of MSD. | Set to visually confirmed linear regime; -1 for auto (10%-90%) [33]. |

gmx msd |

-trestart |

Time between reference points for MSD calculation. | Balance between statistical sampling and memory usage (e.g., 10 ps) [33]. |

gmx msd |

-maxtau |

Maximum time delta for MSD calculation. | Prevents out-of-memory errors in long trajectories [33]. |

gmx msd |

-mol |

Computes MSD and D for individual molecules. | Provides accurate error estimates via molecular statistics [33]. |

| SLUSCHI-Diffusion | N/A | Automated pipeline from AIMD to diffusivity. | Uses block averaging for robust error estimates [5]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

This section lists key software and computational "reagents" essential for molecular dynamics and ab initio simulation workflows.

Table 2: Key Software Tools for Simulation Workflows

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function | Relevance to Thesis Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| GROMACS | Molecular Dynamics Engine | High-performance MD simulation of biomolecules, polymers, etc. | Primary tool for running classical MD simulations to calculate diffusion coefficients. |

| VASP | Ab Initio / DFT Code | Performs electronic structure calculations and AIMD. | Generates highly accurate forces for AIMD, especially in complex or reactive systems. |

| SLUSCHI-Diffusion | Automated Workflow Module | Automates AIMD setup, execution, and MSD analysis for diffusion. | Enables high-throughput, first-principles calculation of diffusivities across compositions [5]. |

| VASPKIT | Post-Processing Toolkit | Parses VASP outputs and computes various properties, including MSD. | Streamlines the analysis pipeline from VASP MD trajectories to diffusion metrics [5]. |

| pdb2gmx (GROMACS) | Topology Builder | Generates molecular topologies from coordinate files. | Critical first step in building a GROMACS simulation system. |

| forcefield.itp | Topology Parameter Set | Defines atom types, bonded terms, and non-bonded interactions. | The physical "law" of the simulation; choice of force field (e.g., CHARMM, AMBER) is critical for accuracy. |

| UM-C162 | UM-C162, MF:C30H25N3O4, MW:491.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| BTZ-N3 | BTZ-N3, MF:C17H16F3N5O3S, MW:427.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Workflow and Protocol Visualizations

Diffusion Calculation Workflow

The diagram below outlines the generalized protocol for calculating diffusion coefficients from molecular dynamics simulations, integrating steps from both GROMACS and SLUSCHI workflows.

Generalized workflow for diffusion coefficient calculation

Simulation Box Size Impact on Workflow

The size of the simulation box is a critical parameter that influences multiple stages of the simulation workflow and the final result. The following diagram illustrates these logical relationships, which are central to the thesis context.

Simulation box size impact on workflow and results

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Our hybrid model's predictions for drug diffusivity are physically inconsistent, showing an increase in diffusion coefficient with density. What could be the cause? A1: Physical inconsistency often stems from the machine learning component learning spurious correlations from insufficient or noisy data. To resolve this:

- Ensure your training data from Molecular Dynamics (MD) covers a wide and representative range of thermodynamic states (density, temperature) [34].

- Implement a symbolic regression (SR) framework, which is designed to derive simple, interpretable equations that often naturally align with physical laws (e.g., diffusivity being inversely proportional to density) [34].

- Validate the model not just on statistical accuracy (R², AAD) but also on its ability to reproduce known physical trends [34].

Q2: What is the most efficient way to generate a high-quality dataset for training the machine learning model in a hybrid workflow? A2: For studying drug diffusion, a coupled experimental-computational approach is highly effective [35].

- Experimental Data: Use a non-invasive method like Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) to measure time-resolved concentration profiles of drugs (e.g., Theophylline, Albuterol) in artificial mucus or other relevant media. Fit this data to Fick's 2nd Law to determine experimental diffusion coefficients [35].

- Simulation Data: Use Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations to generate microscopic data on particle trajectories. This data can be analyzed using traditional methods (Mean Squared Displacement) or used to train a machine learning model that connects macroscopic variables (density, temperature) to the diffusion coefficient [34].

- The combination of both datasets provides a robust foundation for training and validating your hybrid model.

Q3: How can we balance computational speed with physical accuracy in a hybrid model? A3: The core of the hybrid approach is to use a physics-based solver for well-understood phenomena and a data-driven model for complex components [36].

- For Hydrodynamic Models: Use a differentiable particle-mesh (PM) solver to handle gravitational dynamics and other long-range forces efficiently [36].

- For Complex Local Interactions: Replace the analytically derived pressure term in hydrodynamics with a neural network that maps local features (density, velocity divergence) to an effective pressure field. This network is trained on a limited set of high-fidelity reference simulations [36].

- This strategy maintains the overall physical structure of the simulation while using ML to approximate the most computationally expensive or poorly understood parts.

Q4: Our model performs well on the training data but generalizes poorly to new molecular fluids or system conditions. How can we improve generalizability? A4: Poor generalization indicates overfitting. To address this:

- Increase Data Diversity: Incorporate data from multiple molecular fluids into your training set [34].

- Use Reduced Units: Train your model using reduced macroscopic properties (e.g., reduced temperature T, reduced density Ï). This embeds the molecular parameters (like σ and ε from the Lennard-Jones potential) implicitly, helping the model learn universal behaviors [34].

- Seek Universal Expressions: Employ symbolic regression to derive a single, simple equation that applies to a wide range of fluids, rather than a specific model for each one [34].

Experimental and Computational Protocols

Protocol 1: Experimentally Determining Drug Diffusion Coefficients using FTIR

This protocol outlines a method to measure the diffusion coefficients of drugs through artificial mucus, providing ground-truth data for model validation [35].

- Preparation:

- Prepare a solution of the drug of interest (e.g., Theophylline or Albuterol).

- Create an artificial mucus layer that mimics the physiological and biochemical characteristics of native mucus.

- Setup:

- Place the artificial mucus layer into a testing apparatus, ensuring its lower surface is in direct contact with a zinc selenide (ZnSe) crystal.

- Carefully place the drug solution in contact with the upper surface of the mucus layer.

- Data Acquisition:

- Use a Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectrometer to collect spectra at the lower mucus-crystal interface at constant time intervals.

- Monitor quantitative changes in spectral peaks that correspond to functional groups specific to the drug being studied.

- Data Analysis:

- Correlate the changes in peak heights to drug concentration using Beer-Lambert Law.

- Analyze the concentration-time data using Fick's 2nd Law of Diffusion. Crank's trigonometric series solution for a planar semi-infinite sheet is applied to fit the experimental data and determine the diffusion coefficient (D) [35].

Protocol 2: Computational Hybrid Analysis of Drug Diffusion in 3D

This protocol describes a hybrid methodology that combines mass transfer modeling with machine learning to predict drug concentration in a three-dimensional space, useful for analyzing drug release from controlled-release carriers [37].

- Physics-Based Simulation (Data Generation):

- Define Geometry: Create a simple 3D geometry representing the drug diffusion domain (e.g., a liquid medium).

- Set Boundary Conditions: Apply insulation (no-flux) conditions on the walls of the domain.

- Solve Mass Transfer: Solve the mass transfer equation, considering molecular diffusion as the primary driven by concentration gradients, using a Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) method like the Finite Volume Scheme (FVS).

- Extract Data: Export the computed concentration (C) distribution data across the 3D coordinates (x, y, z) at a specific median time. This generates a dataset of over 22,000 points [37].

- Machine Learning Modeling:

- Preprocessing: Clean the dataset by removing outliers using the Isolation Forest algorithm and normalize the features using a min-max scaler [37].

- Model Selection & Training: Train three tree-based ensemble models: ν-Support Vector Regression (ν-SVR), Kernel Ridge Regression (KRR), and Multi Linear Regression (MLR) on the preprocessed data.

- Hyperparameter Optimization: Fine-tune the models using the Bacterial Foraging Optimization (BFO) algorithm to maximize predictive performance [37].

- Validation: Use common regression metrics (R² score, Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE), and Mean Absolute Error (MAE)) to evaluate and select the best-performing model. The study found ν-SVR to have the highest performance with an R² score of 0.99777 [37].

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow of the hybrid computational approach for analyzing drug diffusion.

Hybrid Computational Workflow for Drug Diffusion Analysis

Table 1: Experimentally Determined Drug Diffusivity in Artificial Mucus This table summarizes diffusion coefficients measured for two common asthma drugs using FTIR and Fickian diffusion modeling [35].

| Drug | Diffusion Coefficient (D) in cm²/s | Experimental Method |

|---|---|---|

| Theophylline | 6.56 × 10â»â¶ | FTIR with artificial mucus layer & Fick's 2nd Law |

| Albuterol | 4.66 × 10â»â¶ | FTIR with artificial mucus layer & Fick's 2nd Law |

Table 2: Performance of Machine Learning Models for 3D Concentration Prediction This table compares the performance of different ML models optimized with the Bacterial Foraging Algorithm for predicting drug concentration in a three-dimensional space [37].

| Model | R² Score | RMSE | MAE |

|---|---|---|---|

| ν-Support Vector Regression (ν-SVR) | 0.99777 | Lowest | Lowest |

| Kernel Ridge Regression (KRR) | 0.94296 | Medium | Medium |

| Multi Linear Regression (MLR) | 0.71692 | Highest | Highest |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Hybrid Diffusion Coefficient Analysis This table lists key reagents, materials, and computational tools used in the featured experiments and simulations.

| Item | Function / Explanation | Source / Context |

|---|---|---|

| Artificial Mucus | A synthetic construct that models the strong physiological and biochemical barrier posed by real mucus, allowing for standardized drug diffusion tests. | [35] |

| Zinc Selenide (ZnSe) Crystal | Used as an optical window in FTIR spectroscopy due to its transparency to infrared light, allowing for time-resolved measurement of drug concentration. | [35] |

| FTIR Spectrometer | An analytical instrument used to obtain an infrared spectrum of absorption or emission of a solid, liquid, or gas, enabling non-invasive concentration monitoring. | [35] |

| Symbolic Regression (SR) | A machine learning technique that discovers simple, interpretable mathematical expressions to describe data, ensuring physical consistency in derived equations for diffusivity. | [34] |

| Bacterial Foraging Optimization (BFO) | A swarm intelligence algorithm used for hyperparameter optimization of machine learning models, improving their predictive accuracy for complex tasks like concentration prediction. | [37] |

| ν-Support Vector Regression (ν-SVR) | A powerful regression model that was identified as the most accurate for predicting chemical species concentration in a 3D domain based on spatial coordinates. | [37] |