Nonlinear MSD Curves: Decoding Anomalous Diffusion for Drug Delivery and Biomaterial Research

This article addresses the common challenge of nonlinear mean squared displacement (MSD) curves in single-particle tracking and diffusion studies, a key issue for researchers characterizing nanoparticle motion in complex biological...

Nonlinear MSD Curves: Decoding Anomalous Diffusion for Drug Delivery and Biomaterial Research

Abstract

This article addresses the common challenge of nonlinear mean squared displacement (MSD) curves in single-particle tracking and diffusion studies, a key issue for researchers characterizing nanoparticle motion in complex biological environments. We explore the fundamental principles of anomalous diffusion, moving beyond the ideal linear MSD to explain subdiffusive and superdiffusive behaviors. The content provides a methodological toolkit for accurate analysis, covering advanced techniques from machine learning to the Debye-Waller factor. Troubleshooting guidance helps resolve common experimental pitfalls, while validation frameworks ensure robust, reproducible results. This comprehensive resource equips drug development professionals with strategies to optimize nanocarrier design and accurately predict therapeutic transport through biological barriers.

Beyond Brownian Motion: Understanding the Fundamentals of Anomalous Diffusion

Within the framework of thesis research on non-linear diffusive regimes, the Mean Squared Displacement (MSD) curve serves as a fundamental tool for analyzing particle motion. In an ideal Brownian system, the MSD exhibits a linear relationship with time lag. However, experimental conditions and complex physical systems often cause significant deviations from this ideal linearity. This technical support guide addresses the specific challenges researchers encounter when working with MSD curves, providing troubleshooting methodologies and experimental protocols to enhance data reliability.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: Why is my MSD curve not linear, and what does the shape indicate? A non-linear MSD curve indicates anomalous or non-Brownian motion. The specific shape of the curve provides insights into the type of motion and underlying system properties [1]:

- Confined Diffusion: The MSD curve plateaus at longer time lags, indicating that particle motion is restricted within a limited area [1].

- Subdiffusion (α < 1): Often caused by crowded environments, binding interactions, or obstructed paths, leading to a power-law dependence where MSD increases slower than time [1] [2].

- Superdiffusion (α > 1): Indicates active, directed transport, often with a component of constant drift velocity, where MSD increases faster than time [1].

- Non-linear Diffusion in Phase Transitions: The MSD curve may deviate from linearity due to continuously changing atomic structure, such as during amorphous-to-crystalline transitions [2].

FAQ 2: What is the optimal number of MSD points to use for fitting to get a reliable diffusion coefficient?

The optimal number of MSD points (p_min) for fitting is not fixed; it critically depends on your experimental parameters [3]. Using too few or too many points can lead to biased estimates.

- Key Parameter: The reduced localization error,

x = σ² / (D * Δt), whereσis localization uncertainty,Dis the diffusion coefficient, andΔtis the frame duration [3]. - Small x (x << 1): When localization error is negligible, the best estimate of

Dis often obtained using the first two MSD points [3]. - Large x (x >> 1): When localization uncertainty dominates, more MSD points are needed for a reliable estimate. The optimal number

p_mincan be calculated as a function ofxand the total trajectory lengthN[3].

FAQ 3: How does localization uncertainty and camera exposure affect my MSD analysis? Localization uncertainty and finite camera exposure time artificially inflate the MSD curve, particularly at short time lags, and can mask true diffusion behavior [3] [1].

- Dynamic Localization Error: The effective localization uncertainty (

σ) increases for faster-diffusing particles due to motion blur during the camera's exposure time (t_E). It is approximated byσ = σ₀ / √(1 + D̃t_E / s₀²), whereσ₀is the static localization error ands₀is the PSF dimension [3]. - Impact on MSD: This error adds a constant offset to the theoretical MSD curve, leading to a y-intercept greater than zero and potentially misinterpreted diffusion coefficients if not accounted for [3].

FAQ 4: My trajectories are short. How does this impact my MSD analysis? Short trajectories are a major challenge in SPT, leading to statistically unreliable MSD curves [1].

- Increased Variance: The calculation of the time-averaged MSD for a single trajectory becomes highly variable when the number of points

Nis small [3] [1]. - Limited Regime Observation: Short trajectories may only capture the initial part of the MSD curve, making it impossible to distinguish between different types of motion (e.g., Brownian vs. confined) that only diverge at longer time lags [1].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Inconsistent Diffusion Coefficient Estimates

Problem: The calculated diffusion coefficient D varies significantly based on the number of MSD points used for fitting.

Solution:

- Determine Optimal Fit Points: Calculate the reduced localization error

xto estimate the optimal number of MSD pointsp_minfor fitting [3]. - Use a Consistent Protocol: Once

p_minis determined, apply it consistently across all datasets for comparative analysis. - Fit Appropriately: For pure Brownian motion in an isotropic medium, a simple unweighted least squares fit of the MSD curve using

p_minpoints can provide a reliable estimate ofD[3].

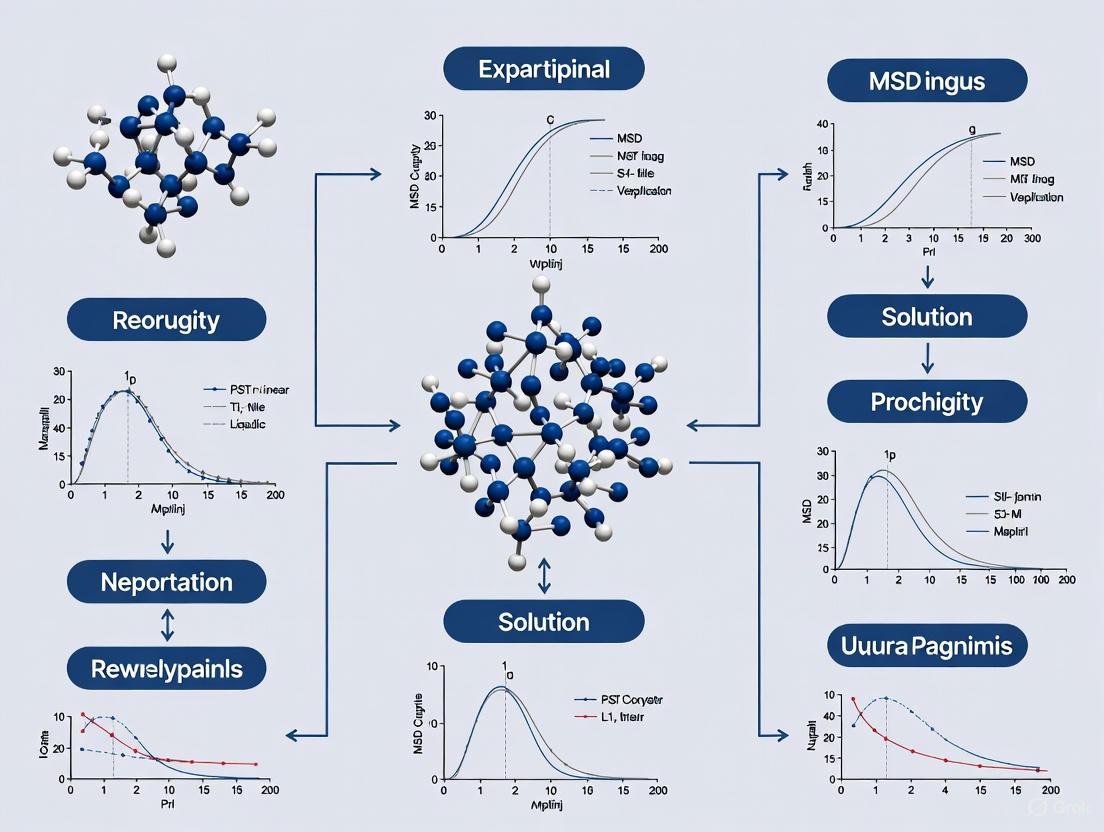

Experimental Workflow: The following diagram outlines the decision process for reliable MSD fitting.

Issue 2: Diagnosing the Source of Anomalous Diffusion

Problem: The MSD curve shows a non-linear, power-law scaling (MSD ~ t^α), and you need to identify potential causes.

Solution:

- Characterize the Anomaly: Fit the MSD curve with the general law

MSD(τ) = 2νD_ατ^αto determine the anomalous exponentαand the generalized diffusion coefficientD_α[1]. - Cross-Reference with System Knowledge:

- Subdiffusion (α < 1): Investigate factors like molecular crowding, transient binding, or viscoelasticity of the medium [1].

- Superdiffusion (α > 1): Look for evidence of active transport mechanisms, such as motor-protein-driven movement or fluid flow [1].

- Complex Trajectories: Consider that a single trajectory may contain multiple motion states. Use methods like Hidden Markov Models or machine learning classification to segment and analyze heterogeneous motions [1].

Diagnostic Diagram: The following flowchart aids in diagnosing the root cause of anomalous MSD curves.

Table 1: MSD Characteristics for Different Diffusion Regimes

| Diffusion Type | MSD Equation | Anomalous Exponent (α) | Common Causes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Brownian | MSD(τ) = 2νDτ |

α ≈ 1 | Thermal agitation in a simple, isotropic fluid [1]. |

| Subdiffusion | MSD(τ) = 2νD_ατ^α |

α < 1 | Crowded environments (cytoplasm, membrane), transient binding, caging effects [1]. |

| Superdiffusion | MSD(τ) = 2νD_ατ^α |

α > 1 | Active transport by motor proteins, directed motion with drift velocity [1]. |

| Confined | MSD(Ï„) = R²(1 - Aâ‚exp(-4Aâ‚‚DÏ„/R²)) |

Plateaus at long Ï„ | Physical barriers, corrals, trapping in organelles [1]. |

Table 2: Key Experimental Parameters Affecting MSD Linearity

| Parameter | Impact on MSD Analysis | Mitigation Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Localization Uncertainty (σ) | Adds constant offset to MSD; inflates short-time-lag values, biasing D and α [3]. | Use high-signal probes; calculate dynamic σ; use optimal fit points [3]. |

| Camera Exposure Time (t_E) | Causes motion blur, increasing effective σ and distorting MSD at short lags [3]. | Use shorter exposure times; use models that account for motion blur [3]. |

| Trajectory Length (N) | Short trajectories lead to high statistical variance in MSD, making fits unreliable [1]. | Use brighter, more photostable labels; combine multiple short trajectories with care [1]. |

| System Heterogeneity | A single average MSD may mask multiple diffusive states, leading to non-linear curves [1]. | Use per-trajectory analysis; implement state-classification algorithms (HMM, ML) [1]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Reliable Diffusion Coefficient Estimation from SPT

Objective: To accurately determine the diffusion coefficient D from a single-particle trajectory while accounting for localization uncertainty.

Materials and Reagents:

- Sample with fluorescently labeled particles of interest.

- High-sensitivity microscope (e.g., TIRF, epifluorescence) with a high-quantum-efficiency camera.

- Software for particle localization (e.g., TrackPy, ThunderSTORM) and trajectory analysis.

Procedure:

- Data Acquisition: Acquire a time-lapse movie with a fixed frame interval

Δt. Ensure the signal-to-noise ratio is optimized to minimize static localization errorσ₀[3]. - Trajectory Reconstruction: Localize particle positions in each frame and link them into trajectories. Filter trajectories based on minimum length (e.g.,

N > 10). - Calculate MSD: For each trajectory, compute the time-averaged MSD for time lags

nΔtusing:MSD(nΔt) = 1/(N-n) * Σ [r((j+n)Δt) - r(jΔt)]²from j=1 to N-n [1]. - Initial Estimate: Obtain an initial estimate of

Dfrom the slope of the first few MSD points. Estimate localization errorσfrom the residuals of the fit or from static PSF fitting. - Determine Optimal Fit Points: Calculate the reduced localization error

x = σ² / (D * Δt). Use this value and the trajectory lengthNto determine the optimal number of MSD pointsp_minfor fitting [3]. - Final Fitting: Perform an unweighted linear fit of

MSD(nΔt)versusnΔtforn = 1top_min. The slope of this fit is equal to2νD, whereνis the dimensionality [3] [1].

Protocol 2: Characterizing Anomalous Diffusion in Complex Media

Objective: To quantify non-Brownian motion and extract the anomalous exponent α and generalized diffusion coefficient D_α.

Materials and Reagents:

- Same as Protocol 1, applied to a complex system (e.g., live cell cytoplasm, nucleus, or a porous material).

Procedure:

- Follow Steps 1-3 of Protocol 1 to obtain the MSD curve.

- Logarithmic Transformation: Plot

log(MSD)as a function oflog(Ï„). - Power-Law Fitting: On the log-log plot, perform a linear fit over a defined time lag range. The slope of this line provides the anomalous exponent

α[1]. - Parameter Extraction: The y-intercept of the linear fit is related to

log(2νD_α). Solve for the generalized diffusion coefficientD_α[1]. - Validation: Be aware that the exponent

αcan be apparent and time-dependent, especially in heterogeneous systems. Use complementary methods (e.g., velocity autocorrelation, angle distribution analysis) to confirm the nature of the motion [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Reagents for Single-Particle Tracking

| Item | Function / Relevance | Example / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Bright, Photostable Fluorophores | Maximizes photon yield, reducing static localization error (σ₀) and enabling longer trajectories [3]. | Quantum dots, organic dyes (e.g., ATTO, Cy), fluorescent proteins (e.g., mEos). |

| High-Sensitivity Camera | Detects low-light emissions with high signal-to-noise, crucial for precise localization [3]. | EMCCD, sCMOS cameras. |

| Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulation Software | Models anomalous diffusion in complex systems like amorphous materials or curved membranes for hypothesis testing [2] [4]. | LAMMPS, GROMACS. |

| Trajectory Analysis Software | Performs MSD calculation, fitting, and advanced analysis (HMM, machine learning classification) [1]. | TrackMate (Fiji/ImageJ), custom Python scripts (using libraries like trackpy), SLIMfast. |

| Variable-Order Fractional (VOF) Model | Analytical tool for quantifying complex, time-dependent anomalous diffusion, such as during phase transitions [2]. | Used to fit non-linear MSD and extract parameters like time-dependent exponent β(t). |

| Foramsulfuron-d6 | Foramsulfuron-d6, MF:C17H20N6O7S, MW:458.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Ulk1-IN-3 | Ulk1-IN-3, MF:C25H21ClO5, MW:436.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The analysis of single-particle trajectories is a fundamental tool in biophysics and materials science for characterizing complex microenvironments. When particles move within crowded cellular spaces or complex fluids, their motion often deviates from normal Brownian diffusion, exhibiting anomalous transport. This technical support center provides methodologies for identifying and characterizing these anomalous behaviors—specifically subdiffusion, superdiffusion, and confined motion—through mean-squared displacement (MSD) analysis. Proper classification is essential for drawing accurate biophysical conclusions, such as understanding binding interactions, cytoskeletal transport, and compartmentalization in living cells.

The core principle involves calculating the time-averaged MSD from particle trajectories, typically fitted to the power law form MSD(τ) = Dατ^α, where Dα is the generalized diffusion coefficient and α is the anomalous exponent. This exponent serves as the primary classifier: α=1 indicates normal diffusion, α<1 signifies subdiffusion, and α>1 suggests superdiffusion. Confined motion presents a distinct pattern where MSD plateaus after initial diffusion. However, accurate classification faces challenges from experimental limitations including trajectory length, localization uncertainty, and the inherent stochasticity of particle motion.

FAQs: Addressing Common Experimental Challenges

Q1: My MSD analysis gives conflicting anomalous exponents for similar biological conditions. What could be causing this inconsistency? Inconsistent α estimates most commonly stem from two sources: insufficient trajectory length and improper handling of localization errors. Short trajectories (N < 100 points) produce MSD curves with high statistical variance, making reliable fitting difficult [5]. Furthermore, localization errors (σ) introduce a positive offset at short time lags, which can artificially inflate the estimated anomalous exponent if not properly accounted for in the model [3] [5]. Ensure you are using the optimal number of MSD points for fitting based on your trajectory length and error magnitude.

Q2: How can I distinguish between genuine subdiffusion and confined diffusion? While both exhibit α < 1, their MSD curves have distinct profiles. Genuine subdiffusion (e.g., from fractional Brownian motion) typically shows a continuous power-law increase. In contrast, confined diffusion is characterized by an MSD that increases linearly at very short lag times and then plateaus to a constant value as the particle explores the entire confinement area [6] [7]. Tools like aTrack use hidden variable models to specifically identify the signatures of confinement, such as estimating a confinement radius, providing a statistical basis for this distinction [6].

Q3: What is the minimum trajectory length required for reliable classification? There is no universal minimum, as required length depends on the strength of the anomalous parameter. However, simulation studies indicate that for confident classification between Brownian, subdiffusive, and superdiffusive motion, trajectories of at least 50-100 steps are often necessary for moderate anomalous parameters [5]. For stronger confinement or directed motion (higher velocity), shorter trajectories may suffice, while weaker effects require longer trajectories for statistically significant classification [6]. As a general guideline, strive for trajectories of 200+ steps for robust parameter estimation.

Q4: Why does my MSD curve appear linear even when I expect anomalous transport? The expected anomalous behavior might be masked if the particle switches between different motion states within a single trajectory, resulting in an averaged MSD that appears linear [3]. Alternatively, you may be fitting too many MSD points at large lag times where the variance is high, obscuring the true underlying trend. Implement a state-of-the-art analysis tool like aTrack that can detect hidden motion states [6], and ensure you use the optimal number of MSD points for fitting as detailed in the protocols below.

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Misclassification of Motion Type

Problem: Your analysis incorrectly classifies the diffusion type (e.g., superdiffusion is classified as normal diffusion).

Solutions:

- Check Trajectory Length: Short trajectories (N < 50) have low statistical power for classification. Where possible, acquire longer trajectories or pool results from multiple similar particles [5].

- Use Advanced Classification Tools: Employ a likelihood ratio test framework, as implemented in aTrack, which compares the probability of a trajectory under different motion models (Brownian, confined, directed) [6]. This method is more robust than simple MSD fitting.

- Validate with Simulations: Simulate trajectories with known parameters mimicking your experimental conditions to verify your classification pipeline's accuracy.

- Inspect Individual Trajectories: Do not rely solely on population averages. Some systems exhibit heterogeneous behavior where different particles undergo different types of motion.

Issue: Inaccurate Parameter Estimation

Problem: Estimated parameters (Dα, α, confinement radius) have high uncertainty or are systematically biased.

Solutions:

- Optimize MSD Fitting Range: The number of MSD points (p) used for power-law fitting critically impacts parameter accuracy. Use the following table, adapted from [5], as a starting guideline:

Table: Guidelines for Optimal MSD Fitting Range Based on Trajectory Length

| Trajectory Length (N) | Recommended Max Lag Time (Ï„_M) | Typical Optimal p (points) |

|---|---|---|

| 50-100 | N/5 to N/4 | 10-25 |

| 100-500 | N/5 to N/3 | 20-100 |

| >500 | N/10 to N/4 | 50-125 |

- Account for Localization Error: Explicitly include localization error in your MSD model: MSD(τ) = Dατ^α + 2σ², where σ is the localization precision [5]. Fitting with this corrected model prevents overestimation of α.

- Use Maximum Likelihood Methods: For confined motion, tools like aTrack that use maximum likelihood estimation (MLE) provide more accurate estimates of confinement parameters than MSD fitting, especially for moving confinement zones [6].

Experimental Protocols & Data Analysis

Protocol 1: MSD-Based Classification of Anomalous Diffusion

Purpose: To classify particle motion as normal, subdiffusive, or superdiffusive from single-particle trajectories.

Materials:

- Single-particle trajectory data (x,y,t)

- Programming environment (Python, MATLAB, etc.) with MSD analysis capabilities

- Optional: specialized analysis packages (aTrack, etc.)

Procedure:

- Calculate Time-Averaged MSD: For a trajectory with N positions, compute the MSD for lag times τ = nΔt (n=1,2,...,N/4) using: MSD(τ) = (1/(N-n)) × Σ{i=1}^{N-n} [r(ti+τ) - r(ti)]² where r(ti) is the position at time t_i [5].

Fit to Power Law: Fit the first p points of the MSD curve (see Table above for optimal p) to the equation: log(MSD(τ)) = log(Dα) + α×log(τ) using weighted or unweighted least squares [5].

Classify by Anomalous Exponent:

- α ≈ 1: Normal diffusion

- α < 1: Subdiffusion (e.g., crowded environments)

- α > 1: Superdiffusion (e.g., active transport)

Estimate Confidence: Calculate the 95% confidence interval for α through error propagation or bootstrapping. Reliable classification requires the confidence interval to not cross 1.

Troubleshooting: If the MSD curve shows curvature in the log-log plot, the motion may not be a simple anomalous diffusion process. Consider more complex models or check for confinement.

Protocol 2: Identifying Confined Diffusion

Purpose: To distinguish confined diffusion from other subdiffusive behaviors and estimate confinement parameters.

Materials:

- Single-particle trajectory data

- Software with hidden variable analysis (e.g., aTrack [6])

Procedure:

- Visual MSD Inspection: Plot MSD versus lag time. Confined diffusion typically shows a plateau after initial linear increase, unlike continuous power-law subdiffusion.

Apply Statistical Test: Use a likelihood ratio test to compare Brownian and confined motion models [6]:

- Compute maximum likelihood for Brownian model (L_B)

- Compute maximum likelihood for confined model (L_C)

- Calculate ratio Ï = LB/LC

- If Ï < 0.05, reject Brownian model in favor of confinement

Estimate Confinement Parameters: Using a hidden variable model (e.g., in aTrack), estimate:

- Diffusion coefficient (D)

- Confinement factor (l) or confinement radius

- Localization error (σ)

- Center of potential well (may be moving)

Validate with Simulations: Generate confined trajectories with known parameters to verify estimation accuracy.

Troubleshooting: If the confinement test is inconclusive, check if the trajectory length is sufficient to observe the plateau phase. For weak confinement, longer trajectories are needed.

Data Presentation Standards

Quantitative Data Tables

Table: Characteristic Parameters of Anomalous Transport Regimes

| Motion Type | Anomalous Exponent (α) | MSD Functional Form | Typical Physical Origins |

|---|---|---|---|

| Normal Diffusion | 1.0 | MSD(Ï„) = DÏ„ | Simple liquids, dilute solutions |

| Subdiffusion | 0 < α < 1 | MSD(τ) = Dατ^α | Crowded environments, viscoelastic materials, binding interactions |

| Superdiffusion | α > 1 | MSD(τ) = Dατ^α | Active transport, molecular motor transport |

| Confined Diffusion | Varies with τ | MSD(τ) = R_c²[1 - A×exp(-Bτ)] | Trapping in domains, corralling by barriers, optical tweezers |

Table: Optimal Experimental Conditions for Reliable Classification

| Parameter | Recommended Range | Impact on Classification |

|---|---|---|

| Trajectory Length | >100 frames | Shorter trajectories increase α estimation variance [5] |

| Localization Precision (σ) | σ << √(DΔt) | High σ obscures true motion, biases α upward [3] |

| Frame Rate (1/Δt) | Appropriate for process | Too slow misses rapid motions; too fast increases correlation |

| Signal-to-Noise Ratio | >10 | Low SNR increases localization error |

Essential Visualizations

Anomalous Transport Classification Workflow

MSD Profiles for Different Transport Types

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Computational Tools for Anomalous Transport Analysis

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| aTrack Software [6] | Classifies tracks and extracts parameters for Brownian, confined, and directed motion using hidden variable models | Analysis of single-particle trajectories with potential confinement or directed components |

| Custom MSD Analysis Scripts [5] | Calculates time-averaged MSD and fits anomalous exponent with optimal point selection | General-purpose anomalous diffusion classification |

| Fractional Brownian Motion (FBM) Simulator [5] | Generates simulated trajectories with specified anomalous exponent for method validation | Testing analysis pipelines and establishing detection limits |

| Likelihood Ratio Test Framework [6] | Provides statistical confidence in motion type classification | Objective comparison between different motion models |

| Localization Error Estimator [3] | Quantifies measurement precision from stationary particle data | Accounting for instrumental limitations in diffusion analysis |

| (S)-Lomedeucitinib | (S)-Lomedeucitinib, MF:C18H20N6O4S, MW:419.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| (R)-BMS-816336 | (R)-BMS-816336, MF:C27H28BrNO3, MW:494.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

This technical support resource addresses common challenges researchers face when studying nonlinear diffusion in drug delivery systems, particularly within the broader context of Mean Square Displacement (MSD) curve analysis beyond the linear diffusive regime.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Why does my MSD curve show a large non-linear part or an abnormal drop at the end, and how can I obtain a reliable diffusion coefficient?

A: This is a common issue when the chosen time range for fitting is inappropriate. The problem often arises from using too large a percentage of the simulation duration for the linear fit.

- Solution: Use far less than the default 90% of the time range. For a 50 ns simulation, a range of 5-25 ns might be reasonable. The optimal fitting range should be restricted to the linear part of the MSD curve [8].

- Advanced Consideration: In the context of drug delivery, a non-linear MSD curve (MSD ∼ t^α with α≠1) can itself be a significant finding, indicative of anomalous diffusion. A value of α < 1 signifies subdiffusion, often caused by obstacles or binding events in biological tissues, while α > 1 signifies superdiffusion [9].

Q2: My MSD curve has an inflection point, and the slope changes. Is this a physical effect or an artifact?

A: While this could be a physical phenomenon, you must first rule out artifacts.

- Check for PBC Handling: If you are using the standard per-atom MSD calculation, periodic boundary conditions (PBC) should be correctly handled. An inflection could indicate that a large structure (like a micelle or a drug carrier) has moved across the box boundary, but a properly implemented MSD algorithm accounts for this [8].

- Evaluate Statistical Significance: The inflection might be "noise" due to extremely low statistics. When atoms or molecules move in a correlated fashion (as in a carrier structure), the effective number of independent data points is reduced, which can lead to such artifacts. Increasing simulation time or the number of replicate runs is recommended to confirm the observation [8].

Q3: How do I model drug diffusion in complex, heterogeneous biological tissues where standard diffusion models fail?

A: Classical integer-order differential equations are often insufficient to capture the memory effects and non-local interactions in biological tissues. Fractional calculus provides a powerful alternative framework.

- Recommended Model: Use fractional time-dependent parabolic equations with a Caputo fractional derivative. This model incorporates non-local effects and memory, which are inherent in processes like drug absorption and transport in heterogeneous tissues [10].

- Key Component: The Caputo derivative is defined as:

∂tτU(x,t) = 1/Γ(1−τ) ∫[0 to t] [ Uγ(x,γ) / (t−γ)^τ ] dγwhereΓ(.)is the Gamma function andτ ∈ (0,1)is the fractional order. This integral accounts for the entire history of the system's behavior [10].

Q4: What is the impact of binding reactions on drug delivery profiles from a multilayer capsule?

A: Binding reactions (immobilization) significantly retard the drug release process.

- Quantitative Effect: The total mass of drug delivered is reduced with an increasing Damköhler number (Da), which is the dimensionless number that represents the ratio of the binding reaction rate to the diffusion rate [11].

- Practical Implication: In a diffusion-reaction model, a higher Damköhler number means a greater portion of the drug is immobilized within the capsule layers, leading to a lower cumulative release and potentially a longer delivery time [11].

Experimental Protocol: Analyzing Anomalous Diffusion in Drug Delivery

Objective: To characterize the diffusion regime of a drug molecule released from a polymeric carrier into a biological tissue model and determine the anomalous exponent (α) and effective diffusion coefficient (D).

Methodology:

- System Setup: Construct a simulation or experimental system with a drug-loaded carrier (e.g., a multilayer spherical capsule) immersed in a release medium that mimics tissue properties (e.g., a hydrogel) [11].

- Data Collection: Track the position of drug molecules over time. In simulations, use Molecular Dynamics (MD) to output trajectories. In experiments, use Single-Particle Tracking (SPT) microscopy [3].

- MSD Calculation: For each trajectory, compute the MSD as a function of the time lag (t). For a 2D trajectory, MSD(t) = 〈[x(t+τ) - x(τ)]² + [y(t+τ) - y(τ)]²〉 [3].

- Model Fitting: Fit the MSD curve to the power-law equation:

MSD(t) = 4D t^α(for 2D). The exponent α classifies the diffusion type, and D is the effective transport coefficient [9] [2].

Workflow Diagram:

Data Presentation: Diffusion Regimes and Characteristics

Table 1: Classification of Diffusion Regimes Based on MSD Analysis

| Diffusion Regime | Anomalous Exponent (α) | MSD Power Law | Physical Interpretation in Drug Delivery |

|---|---|---|---|

| Subdiffusion | < 1 | MSD ∼ t^α | Caused by obstacles, binding, or trapping in heterogeneous tissues [9] [10]. |

| Normal Diffusion | = 1 | MSD ∼ t | Simple, unhindered Brownian motion. |

| Superdiffusion | > 1 | MSD ∼ t^α | Directed transport or active processes; can result from scale-free permeability distributions in fractures [9]. |

Table 2: Impact of Key Parameters on Drug Delivery from a Multilayer Spherical Capsule

| Parameter | Symbol | Effect on Drug Delivery | Theoretical Insight |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sherwood Number | Sh | A low Sh increases delivery time and reduces total mass delivered [11]. | Represents convective boundary condition at the outer surface. |

| Damköhler Number | Da | An increasing Da reduces the total mass of drug delivered [11]. | Represents the ratio of binding reaction rate to diffusion rate. |

| Fractional Order | τ / α | Determines the nature of decay and memory effects; crucial for modeling anomalous transport [10]. | Found in Caputo derivative models; α < 1 leads to slower, subdiffusive transport. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagent Solutions for Studying Nonlinear Diffusion in Drug Delivery

| Item | Function/Description | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Multilayer Spherical Capsules | Core-shell structure with drug-loaded core and controlled-release encapsulant layers [11]. | Model system for studying diffusion-reaction across multiple barriers. |

| Fractional Calculus Software | Numerical solvers for Caputo fractional partial differential equations [10]. | Modeling drug diffusion with memory effects in biological tissues. |

| Bessel-type Factor Model | A diffusion model with a weight factor (xy)â»Â¹ in the operator, derived for heterogeneous media [10]. | Simulating diffusion in geometrically heterogeneous or vascularized tissues. |

| Variable-Order Fractional (VOF) Model | A model where the exponent β(t) changes with time, capturing multi-stage diffusion [2]. | Analyzing non-linear diffusion during processes like carrier degradation or crystallization. |

| ARS-1620 | ARS-1620, MF:C21H17ClF2N4O2, MW:430.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Ani9 | Ani9, MF:C17H17ClN2O3, MW:332.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Model Selection and Application Workflow

Choosing the correct mathematical framework is critical for accurately modeling and interpreting experimental data.

Decision Guide:

Demystifying the Anomalous Exponent (α) and Generalized Diffusion Coefficient (Dα)

In the analysis of particle trajectories, the anomalous exponent (α) and the generalized diffusion coefficient (Dα) are fundamental parameters that describe deviations from normal Brownian motion. When the Mean Squared Displacement (MSD) curve, plotted as MSD(τ) = ⟨r²(τ)⟩, is not linear, the system is exhibiting anomalous diffusion. This is characterized by the power-law relationship ⟨r²(τ)⟩ ∠τ^α, where the anomalous exponent α identifies the type of diffusion, and Dα quantifies its efficiency [12] [13].

Understanding these parameters is crucial in fields like drug development, where intracellular transport of therapeutic agents or virus particles often follows anomalous dynamics [14] [13]. This guide provides troubleshooting and FAQs for researchers encountering challenges in estimating α and Dα from experimental data.

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Inaccurate Estimation of α and Dα from Short/Noisy Trajectories

Traditional Mean Squared Displacement (MSD) analysis often fails with short, noisy, or heterogeneous trajectories, leading to inaccurate estimates for α and D [15].

- Problem: MSD analysis is highly susceptible to noise and poor for short trajectories, making it difficult to distinguish true anomalous diffusion from measurement artifacts [14] [13].

- Solution: Employ advanced computational methods.

- Tandem Neural Network: A deep learning approach uses one network to estimate the Hurst exponent (H = α/2) and a second network to predict D, showing a 10-fold improvement in accuracy over MSD analysis for short, noisy trajectories [15].

- Single-Trajectory Power Spectral Density: This method analyzes the power spectrum of individual trajectories and has been shown to be particularly robust for identifying subdiffusion, even in the presence of localization errors [14].

Issue 2: Handling Heterogeneous Dynamics within Single Trajectories

Particle motion in complex environments like live cells is often not homogeneous. A single trajectory may contain segments with different dynamic states [15] [13].

- Problem: Standard MSD analysis provides an average characterization over the entire trajectory, masking transient changes in diffusion behavior [13].

- Solution: Use a rolling-window analysis combined with state-of-the-art classifiers.

- Methodology: Analyze data within small rolling windows moved along the trajectory. Couple this with a neural network or Hidden Markov Model (HMM) to classify the motion state (e.g., confined, subdiffusive, superdiffusive) and estimate α and D for each segment, thereby resolving heterogeneity along individual trajectories [15] [13].

Issue 3: Distinguishing True Anomalous Diffusion from Brownian Motion

Sometimes, system dynamics are erroneously claimed to be anomalous when the true motion is Brownian, or vice versa [14].

- Problem: For α values close to 1 (Brownian motion), it is statistically challenging to confidently classify the diffusion type, a problem exacerbated by experimental noise [14].

- Solution: Apply a robust criterion based on power-spectral analysis of single trajectories.

- Protocol: Calculate the single-trajectory power spectral density (PSD) for your data. The robustness of this method, especially for fractional Brownian motion, has been tested in the presence of static and dynamic localization errors and provides a more reliable classification of the diffusion type [14].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What do the specific values of the anomalous exponent (α) tell me about my system?

The value of α helps classify the type of particle motion, which can point to underlying physical mechanisms in your experiment.

Table: Classes of Anomalous Diffusion and Their Interpretation

| Anomalous Exponent (α) | Classification | Common Physical Interpretations |

|---|---|---|

| α < 1 | Subdiffusion | Motion in crowded or confined environments (e.g., cytoplasm, porous media, gels); particle trapping or binding interactions [12] [16] [13]. |

| α = 1 | Normal (Brownian) Diffusion | Unobstructed, random motion in a homogeneous environment [12]. |

| 1 < α < 2 | Superdiffusion | Active, directed transport often driven by molecular motors or fluid flow; Lévy flights [12] [17]. |

| α = 2 | Ballistic Motion | Particle moving with constant velocity, a limiting case of directed motion [12]. |

Q2: How do I calculate the generalized diffusion coefficient Dα, and what are its units?

The generalized diffusion coefficient Dα is the proportionality constant in the anomalous diffusion power law: ⟨r²(τ)⟩ = 2d Dα τ^α, where d is the dimensionality. Unlike the normal diffusion coefficient D, the units of Dα depend on the value of α, being [length]² / [time]^α [13]. It is typically extracted by fitting the MSD curve or other models to trajectory data. Advanced methods, like neural networks, estimate Dα assisted by the Hurst exponent, improving accuracy [15].

Q3: My MSD curve is not a perfect power law. What could be the cause?

This is a common scenario with several possible causes:

- Heterogeneous Dynamics: The particle may be switching between different motion states (e.g., free diffusion and confined diffusion) within the observed trajectory [13].

- Measurement Errors: Static localization error (from finite photon counts) adds a positive offset to the MSD at short times, while dynamic localization error (from motion during camera exposure) adds a negative offset, distorting the power-law [14].

- Complex Underlying Process: The diffusion may be governed by a more complex model, such as Continuous-Time Random Walks (CTRW) or diffusion in disordered media, which do not produce simple MSD power laws [12].

Q4: Are there standardized methods to validate my estimates of α and Dα?

Yes, the community has initiated efforts to benchmark methods. The Anomalous Diffusion (AnDi) Challenge was established to objectively evaluate and compare different algorithms for quantifying anomalous diffusion, including the estimation of α and Dα [12]. Using methods that perform well in such challenges is a good practice for validation.

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Detailed Methodology: Resolving Heterogeneous Anomalous Dynamics with Neural Networks

This protocol is adapted from a study demonstrating a tandem neural network for analyzing intracellular vesicle motility and particle-tracking microrheology [15].

- Trajectory Acquisition: Perform Single-Particle Tracking (SPT) experiment to obtain particle trajectories (X-Y-Z-t data).

- Preprocessing: Split long trajectories into smaller segments of a defined length (e.g., using a rolling window) to probe local dynamics.

- Neural Network Analysis:

- Step 1 - Estimate α: Input the trajectory segment into the first neural network, which is trained to output the Hurst exponent

H. Calculate the anomalous exponent asα = 2H. - Step 2 - Estimate Dα: Input the trajectory segment and the calculated

Hvalue into a second neural network, which is trained to output the generalized diffusion coefficientDα.

- Step 1 - Estimate α: Input the trajectory segment into the first neural network, which is trained to output the Hurst exponent

- Post-processing: Map the outputs (α and Dα) back to the original trajectory's spatial and temporal coordinates to visualize and analyze the heterogeneity of the dynamics.

Workflow Diagram: From Experiment to Parameters

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for extracting α and Dα from an SPT experiment, incorporating both standard and advanced troubleshooting methods.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table: Key Reagent and Computational Solutions for Anomalous Diffusion Research

| Item | Function / Description |

|---|---|

| Fluorescent Probes / Tracers | Particles (e.g., quantum dots, fluorescent beads, labeled viruses) used for Single-Particle Tracking to visualize motion in the system of interest [14] [13]. |

| Single-Particle Tracking (SPT) Software | Software for reconstructing particle trajectories from time-lapse microscopy images (e.g., TrackMate, u-track) [13]. |

| Anomalous Diffusion (AnDi) Challenge Datasets | Benchmark datasets of simulated trajectories with known parameters, used for validating and testing analysis algorithms [12]. |

| Neural Network Models for SPT | Pre-trained or trainable deep learning models (e.g., Tandem NN) for accurately estimating α and Dα from trajectories, especially effective for short and noisy data [15]. |

| Hidden Markov Model (HMM) Tools | Computational tools to identify different dynamic states (e.g., bound vs. diffusive) and their switching kinetics within a single trajectory [13]. |

| MLS-573151 | MLS-573151, MF:C21H19N3O2S, MW:377.5 g/mol |

| Psma-IN-1 | Psma-IN-1, MF:C66H80N10O20, MW:1333.4 g/mol |

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: My Mean Squared Displacement (MSD) curve is not linear, and the diffusion exponent (α) is less than 1. What does this mean? This indicates subdiffusive behavior, meaning the branched polymer nanoparticle is experiencing significant confinement within the crosslinked network. The motion is hindered, and the particle does not diffuse freely. This is common when the nanoparticle size is comparable to or larger than the mesh size of the network [18].

Q2: How can I reliably measure diffusion when the MSD is strongly subdiffusive? Direct measurement of a classical diffusion coefficient (D) is challenging under pronounced subdiffusion. It is recommended to use the Debye-Waller (DW) factor as an alternative metric. The DW factor, which quantifies cage-scale vibrations, has been proven to predict long-time diffusion reliably and can be estimated even when direct D measurement is difficult [18].

Q3: What is the optimal number of MSD points to use for fitting the diffusion coefficient? The optimal number of points depends on the reduced localization error (x = σ²/DΔt). Using too many points can introduce significant error [3].

- When the localization error is small (x << 1), the best estimate of D is obtained using the first two MSD points.

- When the localization error is large (x >> 1), a larger number of MSD points is needed for a reliable estimate. The exact optimal number is a function of x and the total trajectory length N [3].

Q4: Why do elongated bottlebrush polymers sometimes diffuse better than spherical star polymers in my experiments? Simulations show that in relevant confinement regimes, anisotropic and deformable bottlebrushes have higher mobility than more spherical stars of the same molecular weight. Their elongated shape and deformability allow them to navigate pores more effectively, sometimes even shrinking to pass through constrictions, while stars are more likely to become trapped [18].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

| Issue | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High variability in calculated diffusion coefficients | Using a non-optimal number of MSD points for fitting [3] | Determine the optimal number of fitting points (p_min) based on your reduced localization error (x) and trajectory length. |

| Particles appear trapped with no long-range diffusion | Strong geometric confinement; particle size is larger than the network mesh size [18] | Characterize the network mesh size. Consider using more deformable or anisotropic nanoparticles (e.g., bottlebrushes) to improve mobility. |

| MSD curve is too noisy for reliable analysis | Insufficient trajectory length or high localization uncertainty [3] | Acquire longer trajectories or improve the signal-to-noise ratio in your imaging to reduce localization error. |

| Inability to directly compute a diffusion coefficient due to subdiffusion | Pronounced non-linear MSD regime [18] | Calculate the Debye-Waller factor as a proxy for confined mobility. Use machine learning (Gaussian process regression) to predict it from particle and network descriptors [18]. |

Experimental Protocols & Data

Key Quantitative Data from Simulations

The following table summarizes key findings from coarse-grained molecular dynamics simulations on the diffusion of branched polymers in crosslinked networks [18].

| Parameter / Result | Bottlebrush Polymers (Anisotropic) | Star Polymers (Spherical) |

|---|---|---|

| Performance under Confinement | Higher mobility in relevant confinement regimes [18] | Lower mobility compared to bottlebrushes [18] |

| Long-time Dynamics | Remains diffusive even at high molecular weights [18] | Becomes subdiffusive except under weakest confinement and low molecular weight [18] |

| Primary Control Parameter | Diffusion coefficient decreases with confinement ratio (particle size / mesh size) for both architectures [18] | |

| Recommended Metric | Debye-Waller factor is a reliable predictor of long-time diffusion [18] |

Detailed Methodology: Coarse-Grained Molecular Dynamics (CGMD)

This protocol is adapted from the simulations used to study branched polymer diffusion [18].

1. Model Setup

- Nanoparticle and Network: Both are modeled using a bead-spring model in an implicit solvent. Each bead represents a single Kuhn segment.

- Non-bonded Interactions: Use a truncated, purely repulsive Lennard-Jones (LJ) potential with interaction strength ε, monomer diameter σ, and cutoff rc ≈ 1.12σ.

- Bonded Interactions: Model with a harmonic potential with a high spring constant (k = 1000 ε/σ²) and an equilibrium bond length r0 = 0.97σ.

- Network Construction: Generate the polymer network as a cubic lattice with periodic boundary conditions to create an infinite 3D mesh.

2. Simulation Execution

- System Preparation: Generate the nanoparticle and polymer network independently. Insert the nanoparticle into a vacant lattice cell.

- Initialization: Assign initial velocities from a Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution at the desired temperature (e.g., T=1.0 in reduced units).

- Energy Minimization: Run an energy minimization step to remove bad contacts.

- Equilibration:

- Perform a soft relaxation in the NVT ensemble for 5×10² τ (where τ is the simulation time unit).

- Follow with equilibration in the NVE ensemble using a Langevin thermostat for 5×10³ τ.

- Production Run: Conduct a long production run (e.g., 2.5×10ⶠτ) for data collection. Run multiple independent replicas (e.g., 10) with different initial velocities to improve statistics.

3. Data Analysis

- Mean Squared Displacement (MSD): Calculate the MSD of the nanoparticle's center of mass. Use a hybrid linear-log scheme for saving trajectories to balance short- and long-time accuracy.

- Diffusion Exponent (α): Fit the MSD to a power law 〈r²(t)〉 = Dαtα for times t/τ > 100. Classify as diffusive if α = 1 ± 0.05, and subdiffusive if α < 0.95.

- Debye-Waller (DW) Factor: Compute the DW factor as a metric of confined mobility, which correlates with long-time diffusion.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function / Role in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Coarse-Grained Bead-Spring Model | Represents a single Kuhn segment of the polymer; the fundamental building block for both the nanoparticle and the network [18]. |

| Repulsive Lennard-Jones Potential | Models the excluded volume interactions between all beads, preventing overlap and providing steric repulsion [18]. |

| Harmonic Bond Potential | Maintains the connectivity between beads within the polymer chains, providing structural integrity to the nanoparticles and network [18]. |

| Langevin Thermostat | Maintains a constant temperature during simulations and implicitly models the friction and random kicks from a solvent [18]. |

| Gaussian Process Regression (GPR) | A machine learning method used to build a surrogate model that predicts the DW factor from particle and network descriptors, enabling rapid design [18]. |

| TrxR-IN-7 | TrxR-IN-7, MF:C22H21NO3, MW:347.4 g/mol |

| Fitusiran | Fitusiran, MF:C78H139N11O30, MW:1711.0 g/mol |

Workflow and Pathway Diagrams

Experimental and Analysis Workflow

MSD Analysis Decision Pathway

Advanced Analytical Techniques for Characterizing Complex Diffusion

FAQ: Core Concepts and Troubleshooting

F1: What is the fundamental difference between MSD and the Debye-Waller factor? The Mean Squared Displacement (MSD) quantifies the absolute deviation of a particle's position from a reference point over time, measuring the total spatial extent explored. In contrast, the Debye-Waller (DW) factor describes the attenuation of scattering intensity in techniques like X-ray or neutron scattering, caused by the thermal motion or static disorder of atoms. While both relate to atomic displacements, the MSD is a direct measure of particle trajectory, whereas the DW factor is an experimentally determined parameter that reflects the mean-square displacement of scattering centers [19] [20].

F2: My MSD curve is not linear, indicating anomalous diffusion. How can the Debye-Waller factor help? In strongly confined or sub-diffusive systems where the MSD does not reach a linear regime, measuring a classical diffusion coefficient becomes challenging. In such cases, the Debye-Waller factor, which quantifies cage-scale vibrations on short timescales, can serve as a practical predictor for long-time diffusion. A higher DW factor indicates greater localized mobility, which can correlate with the particle's eventual ability to escape confinement and diffuse, even when the MSD appears trapped [18].

F3: Why is my Debye-Waller factor so large, and what does it imply about disorder? A large Debye-Waller factor often signifies substantial atomic mean-square displacement. This can arise from two sources: dynamic (thermal) disorder or static (structural) disorder. For instance, in a disordered cubic polymorph of Cuâ‚‚ZnSnSâ‚„, the DW factor was found to be significantly larger than in the ordered tetragonal phase due to a temperature-independent static contribution from cation disorder [21]. If your system is well-ordered and at low temperature, a large DW factor could suggest high dynamic flexibility or the presence of unforeseen structural defects.

F4: How do I interpret a bimodal distribution of MSDs in my analysis? A bimodal distribution indicates dynamical heterogeneity, meaning your sample contains populations with distinct mobilities. For example, in protein dynamics, a bimodal distribution of hydrogen atom MSDs reveals that some atoms are tightly bound and move with the molecular chain, while others are more independent and exhibit larger displacements. Ignoring this heterogeneity and using a single average MSD can lead to misinterpretation of scattering data. Analyzing the distribution provides a more realistic picture of the dynamics [22].

Experimental Protocols & Data Presentation

Protocol: Calculating DW Factor from Simulation Trajectories

This protocol is adapted from studies on polymer and nanoparticle dynamics [18] [23].

- System Setup & Equilibration:

- Model your system (e.g., polymer melt, protein in solution, nanoparticle in a network) using a suitable coarse-grained or all-atom force field.

- Carry out equilibration runs in the NPT ensemble (constant Number of particles, Pressure, and Temperature) to relax the system density. Ensure equilibration lasts for at least several times the relaxation time of the slowest relevant correlation function (e.g., the end-to-end vector autocorrelation function for polymers).

- Production Run:

- Switch to the NVT ensemble (constant Number of particles, Volume, and Temperature) for production.

- Run a sufficiently long simulation, saving trajectory frames at intervals short enough to capture the fast vibrational dynamics (on the order of picoseconds in reduced MD units).

- Analyze Vibrational Dynamics:

- The Debye-Waller factor is intimately related to the decay of the intermediate scattering function or the rattling motion of particles within their local "cages."

- A common practical approach is to analyze the plateau of the Mean Squared Displacement at short times, before the onset of large-scale translational diffusion. The DW factor is then proportional to the value of this plateau.

- Validation:

- Confirm that the measured DW factor correlates with long-time diffusion coefficients if they are measurable in your system.

Protocol: Isolating Static and Dynamic Disorder from DW Factors

This methodology is derived from the analysis of crystalline materials like CZTS [21].

- Data Collection:

- Perform X-ray or neutron diffraction experiments on your sample across a temperature range (e.g., 100 K to 700 K).

- Refine the crystal structure from the diffraction patterns to extract the Debye-Waller factor (reported as the B-factor, where ( B = 8\pi^2\langle u^2 \rangle )) for each atom or an average for the structure.

- Temperature-Dependent Analysis:

- Plot the extracted mean-square displacement, ( \langle u^2 \rangle ), against temperature.

- In a perfectly ordered crystal, ( \langle u^2 \rangle ) should increase linearly with temperature due to thermal vibrations.

- Component Separation:

- A significant, temperature-independent upward shift in ( \langle u^2 \rangle ) across the entire temperature range indicates a static disorder component.

- The slope of the ( \langle u^2 \rangle ) vs. T plot still reflects the dynamic disorder from thermal vibrations.

- Computational Verification:

- Support your findings with ab initio molecular dynamics calculations, which can help pinpoint which atomic species contribute most significantly to the static disorder.

Table 1: Key Metrics for Characterizing Motion and Disorder.

| Metric | Mathematical Definition | Typical Units | Primary Application | Interpretation of High Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Squared Displacement (MSD) | ( \langle | \mathbf{x}(t) - \mathbf{x_0} |^2 \rangle ) [19] | nm², Ų | Particle tracking, diffusion analysis | Large explored volume, efficient diffusion or directed transport |

| Debye-Waller Factor (DWF) | ( \exp(-q^2\langle u^2 \rangle / 2) ) [20] | Dimensionless | X-ray/neutron scattering, crystallography | Large attenuation; significant thermal motion or static disorder |

| B-factor (Crystallography) | ( B = 8\pi^2\langle u^2 \rangle ) [20] | Ų | Protein crystallography, material science | High atomic flexibility or local disorder in the structure |

| Generalized Diffusion Coefficient | ( \langle r^2(t) \rangle = D_\alpha t^\alpha ) [18] | cm²/sâ½Â¹â»Î±â¾ | Anomalous diffusion analysis | Scaling factor for displacement in sub-/super-diffusive regimes |

Table 2: Troubleshooting Guide for Non-Linear MSD and DW Factor Analysis.

| Observed Issue | Potential Causes | Solution Steps | Alternative Metric to Consult |

|---|---|---|---|

| MSD curve is sub-linear (sub-diffusive) | Confinement, crowding, binding interactions [18] | 1. Calculate the instantaneous logarithmic derivative of MSD.2. Compute the Debye-Waller factor to probe short-time cage mobility.3. Check for dynamical heterogeneity. | Debye-Waller Factor, Non-Gaussian Parameter |

| MSD curve is super-linear (super-diffusive) | Active transport, flow effects, drift | 1. Subtract any deterministic drift from the trajectory.2. Ensure the measurement is in an inertial reference frame. | Velocity Autocorrelation Function |

| Exceptionally large DW Factor / B-factor | High temperature, static atomic disorder, soft vibrational modes [21] | 1. Perform experiments as a function of temperature.2. Analyze if the excess displacement is temperature-independent (static).3. Use computational modeling to identify disordered atoms. | Static Disorder Analysis, Computational Modeling |

| Incoherent neutron scattering data is not fit by a single MSD | Dynamical heterogeneity: a wide distribution of atomic mobilities [22] | 1. Model the elastic scattering with a distribution of MSDs (e.g., bimodal or Gamma).2. Do not force a fit with a single average MSD. | Distribution of MSDs, Bimodal Model Fitting |

Visual Guide: Decision Workflow

Decision Workflow for Analyzing Complex Diffusion

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational and Analytical Tools.

| Tool / Reagent | Function / Description | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Coarse-Grained Bead-Spring Model | Represents molecules with interacting beads connected by harmonic springs; reduces computational cost [18] [23] | Simulating polymer melts and nanoparticle dynamics. |

| LAMMPS (MD Simulator) | Open-source software for classical molecular dynamics simulations [23] | Performing production runs in NVT/NPT ensembles for trajectory generation. |

| Langevin Thermostat | A thermostat that adds friction and random noise to maintain constant temperature in implicit solvent [18] | Equilibrating and running simulations of solvated systems without explicit solvent atoms. |

| Stretched Exponential Function | ( f(t) = \exp(-(t/\tau)^\beta) ); models complex, non-exponential relaxation processes [23] | Fitting primary (α) and secondary (β) relaxation in correlation functions. |

| Gaussian Process Regression (GPR) | A machine learning method to predict an observable based on input parameters [18] | Building a surrogate model to predict the Debye-Waller factor from system descriptors. |

| mcK6A1 | mcK6A1, MF:C71H99N17O16, MW:1446.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Gaussian Process Regression for Diffusion Prediction

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What makes Gaussian Process Regression particularly suitable for predicting diffusion in complex biological systems?

Gaussian Process Regression is uniquely valuable for diffusion prediction because it provides not just point predictions but also quantifies uncertainty around those predictions. This is crucial in drug development applications where understanding confidence intervals is as important as the predictions themselves. GPR is a non-parametric, Bayesian approach that places a distribution over possible functions that could fit your data, unlike traditional regression models that assume a fixed functional form. This makes it especially effective for modeling complex diffusion processes where the underlying mechanisms may not follow simple analytical models [24].

Q2: My GPR model is predicting constant values regardless of input. What might be causing this issue?

This problem typically arises from an inappropriate kernel choice. Specifically, if you're using a White kernel, it defines similarity in a binary way - data points are either completely identical or completely different. If all your input points are unique, they're all treated as equally similar, forcing the model to predict the mean value of the training set. The solution is to switch to a more appropriate kernel such as the Radial Basis Function (RBF) kernel, which properly captures similarity based on distance between data points [25]. Additionally, ensure your input features are properly normalized, as large numerical values in features like timestamps can also cause convergence issues.

Q3: How can I handle the computational challenges of GPR when working with large diffusion datasets?

The computational complexity of GPR scales as O(n³) due to matrix inversions required in covariance computation, making it challenging for large datasets. For extensive diffusion data, consider implementing sparse Gaussian process methods or approximate inference techniques. These approaches use inducing points or other approximations to reduce computational burden while maintaining predictive accuracy. GPR is best suited for small to medium-sized datasets where data efficiency is key, and its uncertainty quantification provides high value for critical applications like drug delivery system design [24] [18].

Q4: What are the practical considerations for applying GPR to predict diffusion coefficients from Mean Squared Displacement (MSD) data?

When working with MSD data, ensure you're using the appropriate distance metrics for curved membranes or complex environments. For diffusion along curved membranes, geodetic distances calculated along the membrane surface provide more accurate results than projected Euclidean distances. Tools like CurD implement specialized algorithms such as the Vertex-oriented Triangle Propagation (VTP) to compute these geodetic distances efficiently, which is essential for accurate diffusion coefficient estimation in biologically relevant systems like endocytic vesicles or mitochondrial membranes [26].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem 1: Poor Prediction Accuracy Despite Sufficient Training Data

Symptoms: The GPR model fails to capture patterns in diffusion data, showing high error rates even with adequate training samples.

Solutions:

- Kernel Selection: Experiment with different kernel functions based on your data characteristics. For smooth diffusion processes, the RBF kernel is typically appropriate. For more erratic dynamics, consider Matérn kernels which allow for controlling smoothness [24].

- Hyperparameter Optimization: Optimize kernel hyperparameters (length scale, variance) by maximizing the marginal likelihood rather than using default values. Implement gradient-based optimization or Bayesian optimization for this purpose.

- Feature Engineering: Ensure input features are relevant to diffusion prediction. For polymer diffusion, include descriptors like molecular weight, branching architecture, and confinement ratio [18].

Problem 2: Inadequate Uncertainty Quantification

Symptoms: Confidence intervals don't reasonably expand in regions with sparse data, or are excessively wide throughout.

Solutions:

- Noise Modeling: Properly model observational noise using the alpha parameter in GPR implementation. Estimate noise level from experimental replicates if available.

- Kernel Specification: Review kernel choice as different kernels impose different prior assumptions about function behavior. Consider composite kernels for complex diffusion patterns.

- Data Representation: For multi-output diffusion prediction (e.g., across multiple doses or conditions), implement Multi-Output Gaussian Processes (MOGP) that capture correlations between outputs [27].

Problem 3: Numerical Instabilities and Failed Convergence

Symptoms: Algorithms fail with matrix-related errors or fail to converge during training.

Solutions:

- Matrix Conditioning: Add a small positive value (jitter) to the diagonal of the covariance matrix to improve conditioning.

- Data Normalization: Scale input features to similar ranges to avoid numerical precision issues, particularly important when features like molecular weight and mesh size have different units and scales [25] [18].

- Implementation Choice: For large datasets, use specialized GPR implementations designed for numerical stability, such as those employing Cholesky decomposition methods.

Experimental Protocols for Diffusion Prediction

Protocol 1: Predicting Polymer Nanoparticle Diffusion in Crosslinked Networks

Objective: Predict diffusion coefficients of branched polymers in polymeric mesh networks using Gaussian Process Regression [18].

Materials and Methods:

Table 1: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Item Name | Specification/Type | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| Coarse-grained Molecular Dynamics | LAMMPS Software | Generate diffusion training data through simulation |

| Bead-Spring Model | CGMD Implementation | Represent polymer nanoparticles and network |

| Polymer Network | Cubic lattice structure | Create controlled confinement environment |

| Langevin Thermostat | NVE Ensemble | Maintain constant temperature during simulations |

| Trajectory Analysis | Custom MSD scripts | Calculate mean squared displacement from simulations |

| Gaussian Process Regression | scikit-learn or GPyTorch | Build predictive model for diffusion coefficients |

Step-by-Step Procedure:

System Preparation:

- Generate polymer networks as cubic lattices with varying mesh sizes (e.g., 4 different sizes)

- Create branched polymer nanoparticles (bottlebrushes and stars) with varying molecular weights (4 different weights)

- Insert nanoparticles into network mesh cells following energy minimization protocols

Simulation Execution:

- Conduct production runs for sufficient duration (e.g., 2.5×10â¶Ï„) to capture diffusion dynamics

- Perform multiple replicas (e.g., 10 independent runs) with different initial velocities for statistical robustness

- Save trajectory data using hybrid linear-log scheme for optimal time resolution

Diffusion Metric Calculation:

- Compute Mean Squared Displacement (MSD) using all overlapping time origins: MSD(t) = ⟨|r(t₀+t) - r(t₀)|²⟩

- Calculate instantaneous logarithmic derivative to identify diffusion regimes: β(t) = d(logMSD)/d(logt)

- Extract Debye-Waller factor as predictor for long-time diffusion

GPR Model Development:

- Train GPR using simulation parameters (molecular weight, architecture, mesh size) as inputs

- Use Debye-Waller factor or diffusion coefficients as target variables

- Optimize kernel hyperparameters through marginal likelihood maximization

- Validate model predictions against held-out simulation data

Protocol 2: Multi-Output Prediction of Dose-Response Curves in Drug Screening

Objective: Predict multi-dose drug response curves using genomic features and drug properties through Multi-Output Gaussian Processes [27].

Materials and Methods:

Table 2: Drug Screening and Analysis Resources

| Item Name | Specification/Type | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| GDSC Database | Genomics of Drug Sensitivity | Source drug response and genomic data |

| Cancer Cell Lines | Various cancer types | Provide biological context for testing |

| Drug Compounds | BRAF inhibitors and others | Therapeutic agents for response testing |

| Molecular Features | Mutations, CNA, methylation | Predictors for drug response modeling |

| Multi-Output GPR | Custom MOGP implementation | Simultaneous prediction of all dose-responses |

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Data Collection:

- Retrieve dose-response data from GDSC database for targeted drugs (e.g., BRAF inhibitors)

- Extract genomic features including mutations, copy number alterations, and methylation status

- Obtain drug chemical properties from PubChem database

Feature Processing:

- Normalize all features to comparable scales

- Handle missing data through appropriate imputation methods

- Encode categorical variables (e.g., mutation status) appropriately

MOGP Model Implementation:

- Implement multi-output Gaussian process with correlated output structure

- Model cell viabilities across multiple dose concentrations as correlated outputs

- Train model using genomic features and drug properties as inputs

- Optimize hyperparameters through evidence maximization

Biomarker Identification:

- Calculate feature importance using Kullback-Leibler divergence method

- Compare probability distributions with and without specific features

- Validate identified biomarkers through experimental follow-up

Workflow Visualization

GPR Diffusion Prediction Workflow

MSD to GPR Prediction Pathway

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is my MSD curve non-linear even for particles undergoing Brownian diffusion?

Non-linear MSD curves in Brownian diffusion often result from localization errors and improper fitting ranges. The reduced localization error parameter (x = \sigma^2/D\Delta t) (where σ is localization uncertainty, D is diffusion coefficient, and Δt is frame duration) determines the optimal number of MSD points for fitting. When (x \gg 1), more MSD points are needed for reliable D estimation [3]. Additional factors include:

- Insufficient trajectory length for proper averaging [1]

- Finite camera exposure time causing increased dynamic localization uncertainty [3]

- PBC handling errors during trajectory reconstruction [8]

Q2: What is the optimal number of MSD points to use for diffusion coefficient calculation?

The optimal fitting range depends on your specific system parameters. As a general guideline:

Table: MSD Fitting Recommendations Based on System Parameters

| System Condition | Recommended MSD Points | Justification |

|---|---|---|

| Reduced localization error (x \ll 1) | First 2 points (excluding origin) | Minimizes error from localization uncertainty [3] |

| Reduced localization error (x \gg 1) | More points needed | Reduces stochastic error [3] |

| Standard micelle system (50ns simulation) | 5-25 ns range | Provides linear regime while avoiding poor averaging [8] |

| General practice | Never exceed 50% of trajectory length | Avoids poorly averaged data at long time-lags [8] [28] |

Q3: How can I identify and analyze heterogeneous diffusion within single trajectories?

Traditional MSD analysis often fails to detect heterogeneity. These advanced methods are recommended:

- Hidden Markov Models (HMMs): Identify states with different diffusivities and extract switching probabilities between states [1]

- Deep learning approaches (e.g., DeepSPT): Automatically segment trajectories into different diffusional behaviors with uncertainty estimates [29]

- Distribution analysis: Examine parameters beyond displacements (angles, velocities, times) to detect heterogeneities masked in MSD analysis [1]

Q4: What software tools are available for advanced trajectory segmentation?

Table: Research Reagent Solutions for SPT Analysis

| Tool Name | Language/Platform | Primary Function | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| DeepSPT | Python (standalone executable available) | Deep learning-based trajectory analysis | Temporal behavior segmentation, diffusional fingerprinting, task-specific classification [29] |

| TrackPy | Python | Particle tracking and analysis | Python implementation of Crocker/Grier algorithms [30] |

| laptrack | Python | Tracking step with LAP algorithm | Combines with scikit-image for detection [31] |

| quot | Python | Single particle tracking | Subpixel localization, Gaussian fitting [31] |

| Particle Tracking | MATLAB | Particle tracking from time-lapse series | Comprehensive tracking functionality [32] |

| MDAnalysis | Python | MD trajectory analysis | MSD calculation with FFT acceleration [28] |

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Non-Linear MSD in Brownian Diffusion

Problem: MSD curve shows abnormal drops or inflection points instead of linear behavior [8].

Solutions:

- Adjust fitting range: Use 10-30% of trajectory length rather than default 10-90% [8]

- Verify PBC handling: Ensure periodic boundary conditions are correctly handled during tracking

- Check trajectory length: Extend simulation time if statistics are insufficient

- Correct for localization error: Account for dynamic localization uncertainty using (σ = σ0\sqrt{1+D̃tE/s_0^2}) [3]

Workflow: MSD Analysis Validation

Issue 2: Detecting State Transitions in Heterogeneous Diffusion

Problem: Single trajectory contains multiple diffusion states not apparent in ensemble MSD.

Solutions:

- Implement HMM analysis:

- Define possible states (confined, Brownian, directed)

- Calculate transition probabilities

- Use tools like vbSPT or ExTrack [29]

Apply deep learning segmentation:

- Use pretrained DeepSPT models

- Process trajectories through U-Net ensemble

- Obtain probability estimates for each time point [29]

Analyze parameter distributions:

- Step size distributions

- Angular distributions

- Velocity autocorrelations [1]

Workflow: Heterogeneous Diffusion Analysis

Issue 3: Low Classification Accuracy in State Assignment

Problem: Poor performance in distinguishing diffusion states (e.g., Brownian vs. subdiffusive).

Solutions:

- Expand feature set: Use diffusional fingerprinting with 40+ features rather than just MSD slope [29]

- Increase training data: Ensure broad distribution of diffusional parameters in training set

- Adjust for experimental conditions: Account for localization error and frame rate in model

- Combine methods: Integrate classical statistics with machine learning for validation [1]

Protocol: Diffusion State Classification with DeepSPT

- Input preparation: Format trajectories as (x, y, z, t) coordinates

- Temporal segmentation: Process through U-Net ensemble (3 pretrained models)

- Feature extraction: Generate 40 diffusional features per segment

- Classification: Apply task-specific classifier to map features to biological states

- Validation: Compare with manual annotation or alternative methods

Table: Key Diffusional Features Beyond MSD

| Feature Category | Specific Features | Sensitivity Advantages |

|---|---|---|

| Temporal | Velocity autocorrelation, Direction persistence | Detects transient directed motion [29] |

| Spatial | Radius of gyration, Confinement index | Identifies constrained environments [1] |

| Statistical | Step size distribution, Angular distribution | Reveals heterogeneities masked in MSD [1] |

| Model-based | HMM state probabilities, Anomalous exponent | Quantifies state transitions and non-Brownian behavior [29] |

Advanced Methodologies

Deep Learning Protocol for Trajectory Segmentation

Implementation Steps:

Data Preparation:

- Format trajectories: Ensure consistent (x, y, z, t) coordinate format

- Handle missing data: Interpolate short gaps or split trajectories

- Normalize coordinates: Account for varying spatial scales

Model Application:

- Load pretrained DeepSPT ensemble (3 U-Nets with 1D convolutions)

- Process each trajectory through the ensemble

- Obtain probability estimates for each behavior type at each time point

Segmentation Refinement:

- Apply probability thresholds (typically >0.5 for state assignment)

- Merge short segments likely from noise

- Validate with physical constraints

Biological Interpretation:

- Map diffusional states to biological processes

- Calculate state lifetimes and transition frequencies

- Correlate with external biological markers

Validation Metrics:

- Temporal accuracy: Change point detection precision

- State classification: F1 scores for each behavior type

- Biological relevance: Correlation with known biological events

This comprehensive technical support resource addresses the most common challenges in single-particle tracking analysis, from fundamental MSD interpretation to advanced machine learning segmentation, providing researchers with practical solutions for accurate diffusion analysis within the context of MSD curve linearity research.

Troubleshooting Guide: Common CGMD Setup Errors and Solutions

Encountering errors during the setup of a Coarse-Grained Molecular Dynamics (CGMD) simulation is common. The table below outlines frequent issues, their potential causes, and recommended solutions to help you navigate the setup process.

| Error Message / Symptom | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Residue 'XXX' not found in residue topology database [33] | The force field selected in pdb2gmx does not contain a topology entry for the residue/molecule named 'XXX'. |

1. Check residue naming in your coordinate file matches force field expectations. [33] 2. Manually provide a topology file (.itp) for the missing residue. [33] |

| Long bonds and/or missing atoms [33] | Atoms are missing from the initial structure file, causing pdb2gmx to place atoms incorrectly. |

Check the pdb2gmx output log to identify the missing atom. Model the missing atoms using external software before simulation setup. [33] |

| Atom clashes during energy minimization | Incorrect van der Waals (vdW) distances for coarse-grained beads during solvation. | When solvating a CG model, increase the default vdW distance (e.g., from 0.105 nm to 0.21 nm) to prevent bead overlaps and ensure proper density. [34] |

'Found a second defaults directive' in grompp [33] |

The [defaults] directive appears more than once in your topology or force field files. |

Ensure the [defaults] directive is present only once, typically in the main force field file (forcefield.itp). Comment out or remove duplicate entries in other included files. [33] |

'Invalid order for directive' in grompp [33] |

Directives in the .top or .itp files are in an incorrect sequence. |

Follow the required order for topology directives. [defaults] and [atomtypes] must appear before any [moleculetype] directive. [33] |

| Simulation fails to extend to specified time | Using an old .tpr file or file appending issues when restarting. |

1. Always regenerate the .tpr file with gmx convert-tpr when changing run parameters. [35] 2. Use the -noappend flag with mdrun if output files are missing or named differently from the previous run. [35] |

| IDP conformations are overly compact (Martini FF) | Known issue where protein-water interactions can lead to excessive compactness. | Apply protein-water interaction scaling corrections, which have been shown to improve agreement with experimental data for Intrinsically Disordered Proteins (IDPs). [36] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the key considerations when choosing an all-atom vs. a coarse-grained approach for my system?

The choice depends on your research question and the necessary balance between detail and scale.

- All-Atom (AA) Simulations: Use these when you require high atomic-level detail, such as studying specific ligand-protein interactions, enzyme mechanisms, or the impact of precise chemical modifications. They are more computationally expensive, limiting the accessible time and length scales. [37]