Multiple Short vs. Single Long MD Trajectories: A Strategic Guide for Enhanced Sampling in Biomedical Research

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation is a powerful tool for studying biomolecular structure and dynamics, critical for applications in drug discovery.

Multiple Short vs. Single Long MD Trajectories: A Strategic Guide for Enhanced Sampling in Biomedical Research

Abstract

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation is a powerful tool for studying biomolecular structure and dynamics, critical for applications in drug discovery. However, a central challenge remains: how to best configure simulations to achieve sufficient sampling of conformational space. This article provides a comprehensive analysis for researchers and drug development professionals on the strategic choice between using multiple independent short trajectories versus a single long simulation run. We explore the foundational principles behind these sampling strategies, detailing methodological implementations and software tools. The article further guides troubleshooting common pitfalls like kinetic trapping, outlines rigorous validation techniques to assess sampling convergence, and presents a comparative analysis of the strengths and limitations of each approach. By synthesizing current research and best practices, this guide aims to empower scientists to design more efficient and reliable MD studies for uncovering biologically relevant molecular mechanisms.

The Sampling Problem in Biomolecular Simulation: Why Strategy Matters

The concept of the energy landscape is foundational to molecular dynamics (MD) simulations. Biomolecular systems navigate complex, high-dimensional landscapes characterized by numerous local minima (metastable conformational states) separated by high-energy barriers [1]. The topography of this landscape directly dictates the system's dynamics and thermodynamics. Inadequate sampling of this landscape is a primary limitation in MD, as simulations can become trapped in local minima, preventing the observation of biologically critical rare events or the accurate calculation of free energies [1]. This application note examines the challenges of energy landscape sampling, focusing on the strategic choice between multiple short trajectories and a single long simulation within drug development research.

The Sampling Problem in Molecular Dynamics

Biological molecules are known to have rough energy landscapes, with many local minima frequently separated by high-energy barriers [1]. This roughness makes it easy for a simulation to become trapped in a non-functional state from which it cannot easily escape within a practical simulation timeframe. Recent studies have demonstrated that in long simulations, proteins can get trapped in non-relevant conformations without returning to the original, biologically relevant state [1].

The core of the sampling problem lies in the timescales required to cross these energy barriers. Many functionally important processes—such as large-scale conformational changes in enzymes, protein folding, and ligand unbinding—occur on timescales from microseconds to milliseconds or longer [2]. Despite advances in high-performance computing, directly simulating these timescales with all-atom precision remains computationally prohibitive for most systems [1].

A critical and often-overlooked assumption in MD is that the simulation has reached thermodynamic equilibrium. A system is considered equilibrated when measured properties have converged, meaning their fluctuations remain small around a stable average value after some convergence time [3]. However, achieving true equilibrium is challenging, as properties with biological interest may converge at different rates. While some average structural properties might converge in multi-microsecond trajectories, transition rates to low-probability conformations may require substantially more time [3].

Sampling Strategies: Multiple Short Trajectories vs. Single Long Runs

The choice between using multiple short, independent trajectories (parallel sampling) versus a single long trajectory (serial sampling) involves significant trade-offs in completeness, risk, and computational practicality.

Theoretical Foundations and Trade-offs

- Multiple Short Trajectories: This approach initiates numerous simulations from different starting conditions (conformations, velocities). It aims to broadly and independently probe different regions of the energy landscape, reducing the risk of being confined to a single local minimum basin.

- Single Long Trajectory: This strategy employs one continuous simulation, which allows for the direct observation of the temporal sequence of events and the natural progression of state-to-state transitions without potential bias from initial conditions.

Table 1: Comparison of Sampling Strategy Characteristics

| Characteristic | Multiple Short Trajectories | Single Long Run |

|---|---|---|

| Exploration Breadth | High; can simultaneously sample multiple minima | Lower; may be confined to a subset of states |

| Barrier Crossing | Relies on chance from different starting points | Can directly observe rare, spontaneous transitions |

| Statistical Independence | High; excellent for ensemble averaging | Low; sequential frames are highly correlated |

| Risk of Incomplete Sampling | Distributed; may miss slow transitions | Concentrated; entire simulation may be non-ergodic |

| Computational Parallelization | Ideal (embarrassingly parallel) | Limited to parallelizing force calculations |

| Equilibration Assessment | Easier to monitor convergence across replicates | More challenging; requires internal checks [3] |

Practical Considerations in Drug Discovery

The optimal sampling strategy is highly context-dependent and should be aligned with the specific research question in the drug discovery pipeline [2].

- For conformational analysis and refinement of drug or protein structures, multiple short simulations (nanoseconds to tens of nanoseconds) are often sufficient to relax the structure and explore local conformational space [2].

- For docking and scoring of drug candidates, simulations in the tens to hundreds of nanoseconds may be needed to evaluate binding modes. Multiple short trajectories starting from different docked poses can efficiently assess pose stability.

- For free energy calculations, longer simulations (hundreds of nanoseconds to microseconds) are typically required to achieve converged estimates. A combination of strategies may be optimal, using multiple trajectories to sample different binding modes and longer runs to refine free energy estimates [2].

- For mechanistic studies of drug-target interactions, such as understanding allosteric pathways or induced-fit binding, a single long trajectory (microseconds to milliseconds) may be necessary to capture the slow, correlated motions that govern function [2].

Enhanced Sampling Techniques

To address the inherent limitations of both short and long conventional MD simulations, several enhanced sampling methods have been developed. These techniques aim to accelerate the exploration of the energy landscape and improve the estimation of free energies.

Table 2: Overview of Enhanced Sampling Methods

| Method | Primary Mechanism | Typical Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Replica-Exchange MD (REMD) [1] | Parallel simulations at different temperatures (or Hamiltonians) exchange states, promoting barrier crossing. | Protein folding, peptide conformational sampling. | Computational cost scales with system size; efficiency sensitive to maximum temperature choice. |

| Metadynamics [1] | History-dependent bias potential is added to discourage revisiting previously sampled states ("filling free energy wells with sand"). | Protein-ligand binding, conformational changes, protein folding. | Requires careful pre-selection of a small number of collective variables (CVs) that describe the process of interest. |

| Simulated Annealing [1] | System is heated and then gradually cooled to escape local minima and find low-energy states. | Structure refinement, characterizing highly flexible systems. | Variants like Generalized Simulated Annealing (GSA) can be applied to large complexes at a lower computational cost. |

Experimental Protocols

This section provides detailed methodologies for implementing the discussed sampling strategies.

Protocol: Initiating Multiple Short Trajectories

Objective: To generate a diverse ensemble of conformational states for a protein-ligand complex.

- System Preparation: Obtain the initial 3D structure from the PDB. Solvate the protein-ligand complex in an explicit water box, add ions to neutralize the system, and define the force field parameters.

- Energy Minimization: Perform steepest descent or conjugate gradient minimization to remove steric clashes.

- Equilibration:

- Conduct a short (100 ps) NVT simulation to heat the system to the target temperature (e.g., 310 K).

- Perform a longer (1 ns) NPT simulation to equilibrate the density of the system at the target pressure (e.g., 1 bar).

- Initialization of Replicates:

- From the end of the NPT equilibration, generate 10-20 independent simulation starting points by assigning different random seed values to generate new initial velocities (Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution at the target temperature).

- Production Runs: Launch each independent simulation simultaneously using a high-throughput computing environment. Run each trajectory for a predetermined time (e.g., 50-100 ns).

- Analysis: Monitor convergence by calculating the per-trajectory and cumulative average of key properties (e.g., RMSD, radius of gyration, protein-ligand contacts) and assess when fluctuations remain small around a stable average [3].

Protocol: Executing a Single Long Run

Objective: To observe a rare event, such as ligand unbinding or a large-scale protein conformational change.

- Steps 1-3: Identical to the protocol above (System Preparation, Energy Minimization, and Equilibration).

- Production Run:

- Use a single, continuous simulation on a high-performance computing (HPC) platform, leveraging GPUs for accelerated performance.

- The simulation length should be guided by the system and process of interest, ranging from microseconds to milliseconds [2].

- Save trajectory frames at an interval sufficient to resolve the process of interest (e.g., every 10-100 ps).

- Convergence Monitoring: Continuously monitor the evolution of key properties. Plot the running average of these properties as a function of time. A system can be considered partially equilibrated for a specific property when this running average plateaus and its fluctuations remain small for a significant portion of the trajectory after a convergence time, tc [3].

Visualization of Energy Landscape Concepts

Effective visualization is crucial for analyzing MD simulations and understanding the energy landscape [4]. The following diagrams, generated with Graphviz using the specified color palette, illustrate the core concepts.

Diagram 1: Energy landscape with local minima and barriers.

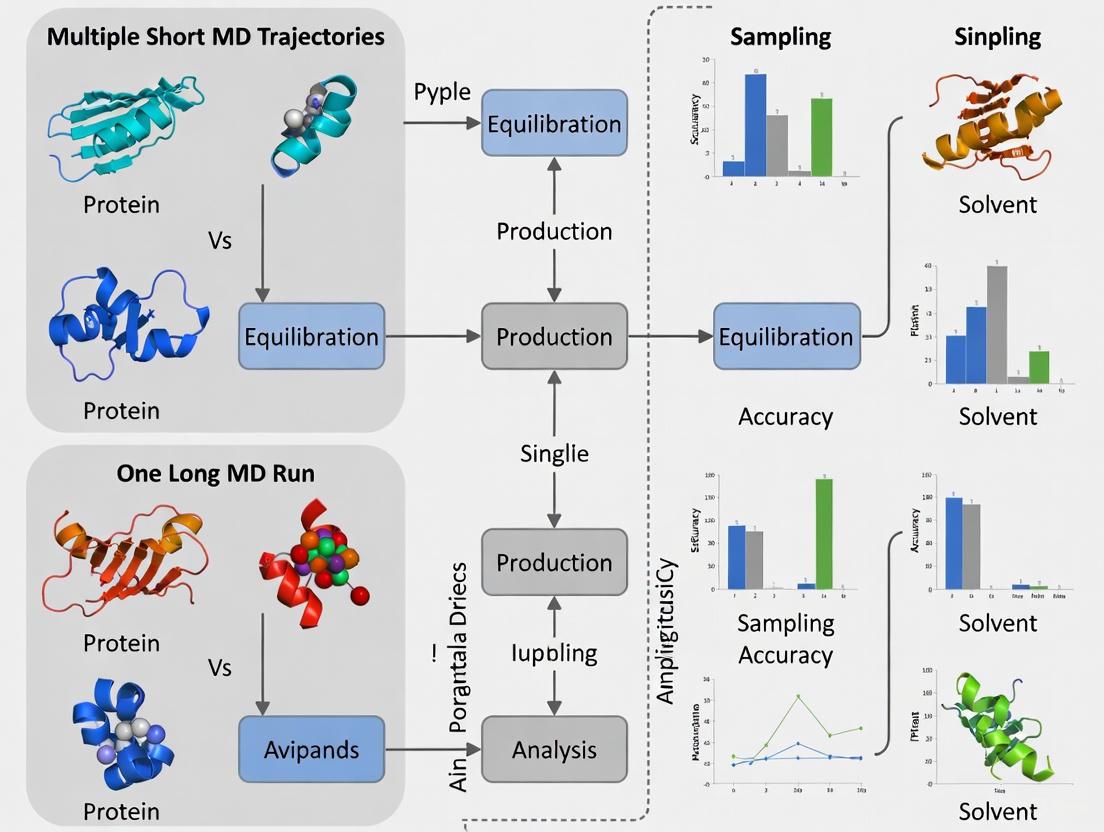

Diagram 2: Workflow for single long run vs. multiple short runs.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Software and Computational Tools for Sampling Studies

| Item Name | Function/Description | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| GROMACS | A high-performance MD software package. | Supports both multiple short runs and long simulations. Highly optimized for CPU and GPU computing [1]. |

| NAMD | A parallel MD code designed for high-performance simulation of large biomolecular systems. | Scalable for large complexes; integrates with VMD for visualization and analysis [1]. |

| AMBER | A suite of biomolecular simulation programs. | Includes extensive tools for running MD and analyzing trajectories, particularly popular in drug discovery [1]. |

| PLUMED | An open-source library for free energy calculations in molecular systems. | Essential for implementing enhanced sampling methods like metadynamics; works with GROMACS, NAMD, and AMBER [1]. |

| VMD | Molecular visualization and analysis program. | Used for visualizing trajectories, creating publication-quality images, and analyzing structural and dynamic properties [4]. |

| MDAnalysis | A Python toolkit for the analysis of MD trajectories. | Enables scripting of complex analyses and streamlines the comparison of multiple trajectories [4]. |

| Clenhexerol | Clenhexerol Hydrochloride | |

| NBD-Cl | NBD-Cl|4-Chloro-7-nitrobenzofurazan [99%] |

The Ergodicity Assumption and the Limitations of Simulation Timescales

The ergodicity hypothesis is a foundational principle in molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, positing that the time average of a molecular system's properties over a sufficiently long simulation will equal its ensemble average [5]. This assumption underpins the validity of using MD trajectories to predict experimentally observable quantities. However, the computational cost of achieving true ergodicity for complex biomolecular systems is often prohibitive [5] [1]. Biomolecules exhibit rugged energy landscapes with numerous local minima separated by high energy barriers, making it easy for simulations to become trapped in non-representative conformational states [1]. This limitation directly impacts the reliability of simulations in fields like drug development, where accurately characterizing molecular dynamics is crucial. The central question in sampling strategy thus becomes: does one long simulation provide a better approximation of the ergodic condition than multiple shorter, independent trajectories? This Application Note examines the theoretical and practical aspects of this question, providing protocols and analyses to guide effective sampling strategies.

Theoretical Background: The Ergodicity Problem in MD

The formal requirement of ergodicity is that a simulation must be long enough to visit all relevant regions of the conformational space with a probability proportional to their Boltzmann weights. In practice, biomolecular systems often violate this assumption due to their complex, multi-funnel energy landscapes and the limited timescales accessible to simulation [1]. A direct consequence is poor sampling of rare events or slow conformational transitions, which can be critical for biological function, such as in protein folding or ligand unbinding [1].

The problem is exacerbated by the fact that the roughness of the energy landscape means that conventional MD simulations can remain trapped in a local minimum for durations that exceed practical simulation times. This trapping leads to non-ergodic behavior and inaccurate estimates of equilibrium properties [1]. Enhanced sampling methods like replica-exchange molecular dynamics (REMD) and metadynamics were developed specifically to address this issue by facilitating barrier crossing [1]. However, the strategic choice between running a single, long trajectory versus multiple short ones remains a fundamental consideration for any MD project, influencing both the quality of the sampling and the practical allocation of computational resources.

Sampling Strategies: A Comparative Analysis

A critical decision in any MD study is whether to allocate computational resources to a single, long simulation or to distribute them across multiple independent, shorter runs. The optimal choice depends on the specific scientific question and the system's characteristics.

Single Long Trajectory

A single long simulation is the traditional approach. Its primary strength is the ability to model slow, correlated motions and observe the temporal sequence of events, which is vital for studying processes like folding or allosteric communication. However, its major weakness is the high risk of becoming kinetically trapped in a local energy minimum, failing to sample the full conformational landscape [1] [6]. For instance, a long simulation of an RNA aptamer was shown to remain trapped in a specific state depending on its initial configuration [6]. From a practical perspective, a single long run also represents a single point of failure; if the simulation crashes, all progress is lost.

Multiple Short Trajectories

The alternative strategy involves initiating multiple independent simulations from different starting conformations. A key study on an RNA aptamer demonstrated that this approach leads to broader conformational sampling and helps avoid deep local energy minima [6]. By starting from diverse points in conformational space, this method effectively performs a parallel exploration of the energy landscape. It is also more robust, as the failure of one simulation does not compromise the entire set. A potential limitation is that each short trajectory may be unable to cross high energy barriers on its own, potentially missing slow, correlated motions that are accessible to a single long run [6].

Table 1: Comparison of MD Sampling Strategies

| Feature | Single Long Trajectory | Multiple Short Trajectories |

|---|---|---|

| Sampling Breadth | Risk of being trapped in a single local minimum [6]. | Superior for exploring diverse conformational states [6]. |

| Rare Events | Can model slow, correlated motions over time. | Better at capturing some rare events through improved state coverage [6]. |

| Kinetic Information | Preserves temporal sequence and long-timescale kinetics. | Provides ensemble statistics but obscures temporal pathways. |

| Computational Robustness | Single point of failure. | Fault-tolerant; failure of one run does not lose significant data. |

| Parallelization | Limited to parallelization within a single simulation. | Ideal for high-throughput computing on distributed systems [7]. |

Quantitative Assessment of Sampling Performance

Rigorous quantitative evaluation is essential for assessing sampling performance. The study of the NEO2A RNA aptamer, which employed 60 independent 100-ns simulations, provides a framework for this assessment [6]. Key metrics include:

- Potential Energy Distribution: Comparing the potential energy distributions across different groups of simulations helps verify that they are sampling consistent regions of the energy landscape [6].

- Recurrence Quantification Analysis (RQA): This technique analyzes conformational transitions and can reveal whether simulations from different starting points exhibit similar dynamic behaviors and recurrence patterns [6].

- Principal Component Analysis (PCA): Projecting trajectories onto principal components allows for a visual comparison of the conformational space sampled by different sets of simulations, identifying both overlapping and uniquely sampled regions [6].

This multi-faceted analysis confirmed that while simulations from different initial structures sometimes explored distinct areas of conformational space, the collective set of multiple short trajectories achieved sufficient sampling without being hindered by kinetic traps [6].

Enhanced Sampling Techniques

When both long and short conventional MD simulations fail to achieve ergodic sampling, enhanced sampling techniques are necessary. These methods manipulate the system's dynamics or energy landscape to accelerate the exploration of phase space.

Table 2: Overview of Enhanced Sampling Techniques

| Method | Principle | Typical Application | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Replica-Exchange MD (REMD) | Parallel simulations at different temperatures (or Hamiltonians) exchange configurations, promoting barrier crossing [1]. | Protein folding, peptide dynamics, studying protein protonation states [1]. | Computational cost scales with system size. Efficiency sensitive to maximum temperature choice [1]. |

| Metadynamics | History-dependent bias potential is added to collective variables to discourage revisiting sampled states, effectively "filling" free energy wells [1]. | Protein folding, molecular docking, conformational changes, protein-ligand interactions [1]. | Requires careful pre-definition of collective variables. Accuracy depends on the dimensionality of these variables [1]. |

| Simulated Annealing | System temperature is gradually decreased from a high value, allowing it to escape local minima and settle into low-energy states [1]. | Structure refinement, characterizing highly flexible systems, studying large complexes [1]. | Variants like Generalized Simulated Annealing (GSA) can be applied to large systems at a lower computational cost [1]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Multiple Independent MD Simulations

This protocol is adapted from a study on RNA aptamer sampling and can be generalized for most biomolecular systems [6].

Generate Initial Conformational Diversity:

- For systems with no experimental structure, use de novo 3D structure prediction to generate multiple (e.g., 6) distinct starting configurations [6].

- For systems with a known structure, diversity can be introduced by:

- Sampling from an existing long trajectory.

- Using structures from enhanced sampling methods like REMD.

- Perturbing the starting coordinates with short, high-temperature simulations.

System Preparation:

- Prepare the protein structure: complete missing residues, resolve alternative locations, remove co-crystallized ligands/waters, and protonate at the desired pH, paying special attention to histidine protonation states (HIE, HID, HIP) [7].

- For protein-ligand complexes, ensure ligand coordinates are aligned with the protein and provide ligands in MOL or SDF format [7].

- Process the structure using a tool like

gmx pdb2gmxto assign hydrogens and write coordinates and a topology in the required format (e.g., GROMACS). Commonly used forcefields include AMBER99SB-ILDN and water models like TIP3P [7].

Equilibration:

- For each initial conformation, perform energy minimization.

- Run equilibration simulations in the NVT and NPT ensembles to stabilize temperature and pressure.

Production Runs:

- Launch multiple independent production simulations (e.g., 10 per starting configuration). The length of each run should be sufficient to overcome local barriers around the starting point [6].

- Utilize a high-throughput automation tool like StreaMD to seamlessly manage and distribute these simulations across multiple servers or a cluster with minimal user intervention [7].

Sampling Assessment:

- Employ the quantitative metrics listed in Section 3.3 (Potential Energy Distribution, RQA, PCA) to evaluate convergence and identify any under-sampled regions of the conformational landscape [6].

Workflow for Enhanced Sampling using Metadynamics

- Identify Collective Variables (CVs): Select a small number (1-3) of CVs that best describe the process of interest (e.g., a distance, angle, or root-mean-square deviation) [1].

- Define the Bias: Set parameters for the Gaussian hills (height and width) that will be added to the potential energy surface during the simulation.

- Run the Simulation: As the simulation progresses, the history-dependent bias potential builds up, discouraging the system from returning to previously visited states in the CV space.

- Calculate Free Energy Surface: The accumulated bias potential can be used to estimate the underlying free energy surface as a function of the chosen CVs [1].

Diagram 1: Decision workflow for MD sampling strategies.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Key Software Tools for MD Sampling and Analysis

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function | Relevance to Sampling |

|---|---|---|---|

| GROMACS [1] [7] | MD Simulation Software | High-performance MD engine for running simulations. | The core software for executing both long and short trajectories; supports enhanced sampling methods like REMD. |

| StreaMD [7] | Automation Toolkit | Python-based tool for high-throughput MD simulation setup, execution, and analysis. | Automates the workflow for multiple independent simulations across distributed computing environments, minimizing user expertise required. |

| CharmmGUI [7] | Web-Based Platform | Generates scripts and input files for MD simulations. | Helps prepare systems for simulation but requires users to manually manage execution and pipeline creation for multiple runs. |

| OpenMM [7] | MD Simulation Framework | A versatile, hardware-accelerated library for building MD simulation pipelines. | Provides the flexibility to create customized pipelines for both standard and enhanced sampling protocols. |

| Thidiazuron | Thidiazuron (TDZ) | Thidiazuron is a potent plant growth regulator for research into morphogenesis, defoliation, and tissue culture. This product is For Research Use Only (RUO). Not for personal use. | Bench Chemicals |

| Proxodolol | Proxodolol | Proxodolol is a dual beta- and alpha-adrenergic receptor antagonist for research. This product is for Research Use Only (RUO), not for human use. | Bench Chemicals |

The ergodicity assumption remains a central challenge in molecular dynamics simulations. While a single long trajectory can be valuable for resolving slow, sequential processes, the evidence strongly supports the strategy of multiple short, independent trajectories for achieving broader and more robust conformational sampling, especially for complex systems. This approach effectively parallelizes the exploration of the energy landscape, reducing the risk of kinetic trapping and providing better ensemble statistics. The integration of quantitative assessment metrics and, when necessary, enhanced sampling techniques is crucial for validating sampling adequacy and overcoming significant energy barriers. For researchers in drug development, adopting high-throughput automated tools like StreaMD for multiple independent simulations represents a practical and powerful strategy to generate more reliable and insightful molecular models, thereby strengthening the link between simulation data and biological function.

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation is a powerful computational method that provides atomic-level insight into the motion and function of biomolecules, playing an increasingly critical role in fundamental research and drug development [8]. A fundamental decision in planning MD studies is the choice of sampling strategy: whether to execute a single, long simulation or to conduct multiple, shorter, independent trajectories. This choice directly impacts the computational resources required, the type of information that can be extracted, and the statistical reliability of the results. Framed within a broader thesis on sampling strategies, this application note delineates the core conceptual and practical differences between these two approaches. It provides a structured comparison and detailed protocols to guide researchers in selecting and implementing the optimal strategy for their specific scientific objectives, such as characterizing equilibrium properties, capturing rare events, or modeling complex biomolecular dynamics.

The choice between multiple short trajectories and a single long run is not merely a technicality but a foundational strategic decision. Each approach explores the conformational space of a biomolecule in a distinct manner, with inherent strengths and limitations. The following table provides a high-level comparison of these two core strategies.

Table 1: Strategic Comparison of Multiple Short vs. Single Long Trajectories

| Aspect | Multiple Short Trajectories | Single Long Trajectory |

|---|---|---|

| Core Philosophy | Statistical sampling from diverse starting points; an ensemble approach. | Continuous observation of a single pathway; a chronological approach. |

| Key Advantage | Better coverage of conformational diversity; avoids being trapped in local energy minima; highly parallelizable [9] [6]. | Can directly observe temporal sequences and long-timescale correlated motions without model building [10]. |

| Typical Application | Characterizing equilibrium ensembles, defining free energy landscapes, and studying processes with multiple pathways [11] [6]. | Studying ordered, sequential processes like folding from a defined state, and calculating time-correlation functions [10]. |

| Parallelization | Embarrassingly parallel: simulations are independent and can be run simultaneously on multiple processors [9]. | Sequential: the simulation is one long, continuous calculation, though modern hardware and algorithms can accelerate it [10]. |

| Risk of Sampling Bias | Lower risk of being perpetually trapped in a single non-representative state. | Higher risk; the entire simulation can be biased if the initial structure is atypical or becomes trapped [6]. |

| Convergence Assessment | Can statistically assess convergence by comparing property distributions across independent trajectories [6]. | Relies on observing property plateaus over time, which can be misleading if the system is trapped [3]. |

Quantitative Analysis of Sampling Performance

A critical question is how the sampling performance of multiple independent simulations compares to that of a single long run. Research indicates that for a given total simulation time, multiple shorter runs can provide broader and more efficient exploration of conformational space. A landmark study on an RNA aptamer conducted 60 independent 100-ns simulations (totaling 6 μs) starting from a diverse set of initial structures [6]. The study found that this approach allowed the system to avoid undesirable outcomes, such as being trapped in a local minimum, which was a risk in long simulations starting from a single structure. The multiple trajectories collectively sampled a wider region of the conformational space than a single long trajectory of equivalent length, demonstrating the power of this approach for characterizing structural ensembles [6].

Table 2: Key Findings from a Quantitative Sampling Performance Study [6]

| Metric | Finding in Multiple Short Trajectories |

|---|---|

| System | NEO2A RNA Aptamer (25 nucleotides) |

| Simulation Setup | 60 independent simulations, each 100 ns (total 6 μs) |

| Initial Conditions | 10 conformations derived from each of 6 distinct de novo predicted structures |

| Primary Outcome | Simulations initiated from different predicted models explored regions not visited by other groups. |

| Conclusion | Conducting multiple independent simulations using a diverse set of initial structures is a promising approach to achieve sufficient sampling and avoid kinetic traps. |

Detailed Protocols for Implementation

Protocol A: Executing and Analyzing Multiple Short Trajectories

This protocol is designed for studies aiming to characterize a thermodynamic ensemble or explore diverse conformational pathways, such as protein unfolding or ligand dissociation [11] [6].

Workflow Diagram: Multiple Short Trajectories

Step-by-Step Instructions:

- System Preparation and Energy Minimization: Begin with an experimentally determined structure or a set of predicted models. Solvate the protein in a water box, add ions to neutralize the system, and perform energy minimization to relieve any steric clashes [6].

- Generate Diverse Initial Conditions: To ensure broad sampling, create variation in the starting structures. This can be achieved by:

- Using different de novo predicted 3D structures if an experimental structure is unavailable [6].

- Sampling from an existing long trajectory.

- Assigning different random seeds for initial velocities.

- High-Temperature Equilibration: For each initial structure, run a short MD simulation at a higher temperature (e.g., 370-500 K). This helps to rapidly explore the local conformational basin and generate distinct starting conformations for the production runs [6] [12].

- Select Starting Snapshots: From each high-temperature equilibration run, select multiple non-consecutive snapshots. These will serve as the initial coordinates for the independent production simulations [6].

- Run Production Simulations: Launch multiple independent MD simulations in parallel. Each simulation should be run under identical conditions (temperature, pressure, force field) but from its unique starting snapshot. The length of each simulation should be sufficient to overcome local energy barriers [9] [6].

- Trajectory Analysis: Analyze each trajectory individually and collectively. Key analyses include:

- Root-mean-square deviation (RMSD): Monitor the structural drift of each trajectory from a reference structure [11] [3].

- Clustering: Group structurally similar conformations from all trajectories to identify highly populated states [13].

- Principal Component Analysis (PCA): Project the high-dimensional conformational data onto its essential degrees of freedom to visualize the sampled space [6].

- Model Building and Property Calculation: Use the combined data to build a Markov State Model (MSM) to understand the kinetics and thermodynamics of state-to-state transitions [12]. Alternatively, calculate ensemble-averaged properties (e.g., radius of gyration, SASA) directly from the pool of conformations generated by all trajectories [11].

Protocol B: Executing and Analyzing a Single Long Trajectory

This protocol is suitable for investigating sequential processes, such as the functional cycle of a protein or folding from a native-like state, where temporal continuity is essential [10].

Workflow Diagram: Single Long Trajectory

Step-by-Step Instructions:

- System Preparation and Energy Minimization: As with Protocol A, begin with a well-prepared and minimized system. A representative starting structure, often an experimental conformation, is critical [10].

- Solvent and Environment Equilibration: Carefully equilibrate the solvent and ions around the fixed protein backbone. This is typically done in two stages: first in the NVT ensemble to stabilize temperature, followed by the NPT ensemble to achieve the correct density and pressure [10].

- Release of Restraints: Gradually release the positional restraints on the protein atoms (backbone followed by side-chains) in a step-wise manner, allowing the protein to relax into its environment.

- Production Simulation: Launch a single, continuous MD simulation. Leverage specialized hardware (e.g., GPUs, ANTON) or highly optimized software to achieve the maximum possible performance and reach microsecond-to-millisecond timescales [10].

- Convergence Monitoring: Continuously monitor key properties to check for stability and convergence. This includes the total and potential energy, RMSD from the initial structure, and secondary structure content. A system is considered equilibrated when these properties fluctuate around a stable average [3].

- Temporal Evolution Analysis: Analyze the trajectory to extract information on the sequence of events.

- Identify key conformational states and the direct pathways connecting them.

- Calculate time-correlation functions to understand dynamic relationships between different parts of the protein.

- Identify the precise order of events, such as the formation of specific contacts during a folding process.

Successful execution of MD sampling strategies relies on a suite of software, force fields, and computational resources. The following table details key components of the modern computational scientist's toolkit.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Molecular Dynamics Sampling

| Category | Item | Function & Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| Software Packages | GROMACS, NAMD, AMBER | Core MD engines for performing simulations; offer high performance on GPU hardware and include tools for setup and analysis [1] [8] [10]. |

| Enhanced Sampling | PLUMED | A library for implementing enhanced sampling methods, such as metadynamics, which can be integrated with multiple MD engines to accelerate barrier crossing [1]. |

| Analysis & Modeling | MDTraj, PyEMMA, MSMBuilder | Python libraries for efficient trajectory analysis and the construction of Markov State Models (MSMs) from large sets of simulation data [13]. |

| Force Fields | CHARMM, AMBER, OPLS | Molecular mechanics force fields that define the potential energy function and parameters; choice can influence sampling and outcomes and should be selected based on the system [12]. |

| Specialized Hardware | GPU Clusters, ANTON Supercomputer | Dedicated processing units (GPUs) and specialized supercomputers (ANTON) enable dramatically longer and faster simulations, making microsecond-to-millisecond timescales accessible [10]. |

| Structure Prediction | AlphaFold2, ROSETTA | Tools for generating initial 3D structural models when experimental structures are unavailable, providing starting points for simulations [6]. |

Integrated and Advanced Strategies

The dichotomy between multiple short and single long trajectories is not absolute. Modern research often employs integrated or advanced strategies that leverage the strengths of both approaches.

Adaptive Sampling: This is a powerful iterative technique that bridges the two core strategies. In adaptive sampling, an initial set of short simulations is run and analyzed to identify under-sampled or strategically important regions of the conformational space. New simulations are then seeded from these regions, and the process repeats. This data-driven approach efficiently directs computational resources to improve sampling of rare events and complex energy landscapes [13].

Combining Simulation with Experiment: To overcome force field inaccuracies and validate sampling, simulations can be integrated with experimental data. For instance, Machine Learning methods can be used to "refine" a Markov State Model (MSM) built from MD simulations by incorporating time-series data from single-molecule FRET experiments. This data assimilation creates a consistent model that agrees with both atomic-level simulation and macroscopic experimental observations [12].

Enhanced Sampling Algorithms: Methods like Replica-Exchange MD (REMD) and Metadynamics are designed to improve sampling efficiency. REMD runs multiple simulations at different temperatures, allowing exchanges that help the system escape local energy minima. Metadynamics applies a history-dependent bias potential along chosen collective variables to "fill up" free energy minima and push the system to explore new regions [1]. These methods can be applied in both single-long and multiple-short frameworks to achieve more comprehensive sampling.

In the field of molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, a fundamental strategic decision researchers face is whether to employ a single long trajectory or multiple short trajectories for conformational sampling. While long simulations aim to observe rare events through continuous sampling, approaches using many short trajectories strategically seeded across conformational space can provide a more efficient means to characterize complex energy landscapes and metastable states [14]. The choice between these strategies necessitates robust, quantitative metrics to evaluate sampling performance, with a focus on conformational diversity and state discovery. Proper evaluation ensures that simulations are not only computationally efficient but also biologically insightful, capturing the dynamic essence of protein function that arises from transitions between conformational states [15]. This application note details the key metrics and protocols for assessing sampling performance within the context of comparing multiple short trajectories against a single long run.

Core Metrics for Evaluating Sampling Performance

Quantifying Conformational Diversity

Conformational diversity measures the breadth of structural states explored during simulation. The metrics in the table below form the foundation for a quantitative assessment of diversity.

Table 1: Key Metrics for Quantifying Conformational Diversity

| Metric | Description | Interpretation | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) | Measures the average distance between atoms of superimposed structures. | Low values indicate structural similarity; high values suggest diversity. Best used after alignment to a reference. | General use for global structural comparison. |

| Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF) | Calculates the fluctuation of a residue around its average position. | Identifies flexible regions (e.g., loops, termini) and rigid domains (e.g., secondary structures). | Pinpointing local flexibility and mobile regions. |

| Radius of Gyration (Rg) | Measures the compactness of a protein structure. | A decreasing trend suggests folding or compaction; an increasing trend suggests unfolding. | Tracking large-scale conformational changes like folding. |

| Template Modeling (TM) Score | A scale-invariant metric for assessing global structural similarity. | Scores range from 0-1; >0.5 suggests generally the same fold, <0.3 indicates random similarity. | Comparing predicted models to experimental structures [16]. |

Quantifying State Discovery and Transition Dynamics

Beyond diversity, effective sampling must identify discrete metastable states and the transitions between them.

Table 2: Key Metrics for State Discovery and Transition Analysis

| Metric | Description | Interpretation | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Committor (({p}_{B})) | The probability a trajectory from a given configuration will reach state B before A [17]. | The definitive metric for reaction progress. ({p}_{B}=0.5) defines a transition state. | Fundamental for mechanism studies; requires significant sampling. |

| Markov State Models (MSMs) | A network model built from short trajectories that describes probabilities of transitioning between states. | Enables prediction of long-timescale kinetics from short simulations. Validated by its implied timescales. | Ideal for integrating many short trajectories to model dynamics [14]. |

| Free Energy Landscape | Projects the simulation onto collective variables to visualize stable states (basins) and transition barriers (saddles). | Deep basins are stable states; low-probability regions are transition states or unstable intermediates. | Visualizing and quantifying the entire conformational landscape. |

Comparative Workflow: Multiple Short vs. Single Long Trajectories

The following diagram illustrates the conceptual and analytical workflow for comparing the two main sampling strategies.

Protocols for Strategic Sampling and Analysis

Protocol A: Generating an Ensemble with Multiple Short Trajectories

This protocol leverages the Dynamical Galerkin Approximation (DGA) to extract long-timescale information from short trajectory data [14].

System Preparation:

- Prepare your protein structure using standard solvation and minimization procedures.

- Define the states of interest (e.g., reactant 'A' and product 'B') based on structural criteria.

Strategic Seeding of Trajectories:

- Use enhanced sampling methods or preliminary short simulations to identify a set of initial configurations (seeds) that span the collective variable (CV) space between states A and B.

- The goal is not random seeding, but strategic placement to ensure coverage of potential transition pathways.

Running Short Simulations:

- Launch a large number (e.g., 50-500) of independent, short MD simulations from the seeded configurations.

- The trajectory length should be sufficient to capture local dynamics but does not need to observe a full state transition. For the Trp-cage miniprotein, trajectories of only 30 ns were effective [14].

DGA Analysis for Committor and Rates:

- Objective: Solve for the committor function and transition statistics without a full MSM.

- Procedure: a. Choose a set of smooth basis functions that capture variations in your CVs across the sampled data. b. Use the DGA framework to compute the matrix elements of the transition operator from the short-trajectory data. c. Solve the resulting linear equations to approximate the committor function for any configuration in the sampled space. d. Use the committor data to compute reaction rates and the reactive current, which reveals the most probable transition pathways.

Protocol B: Leveraging AlphaFold2 for Conformational Seeding

This protocol uses AlphaFold2 (AF2) to generate diverse starting structures for MD simulations, bypassing the need for extensive experimental structures [16].

Input and MSA Generation:

- Input the target protein sequence into the standard AF2 pipeline.

- Generate a deep Multiple Sequence Alignment (MSA).

Driving Conformational Diversity:

- To prevent AF2 from collapsing to a single, dominant conformation, stochastically subsample the deep MSA to a much shallower depth (e.g., 16-128 sequences).

- Run the AF2 prediction multiple times (e.g., 50 models) with different random subsamples of the MSA.

Model Selection and Validation:

- Cluster the resulting models and select representatives based on structural diversity (e.g., using RMSD).

- Validate the models against any known experimental structures for different states using TM-score. A TM-score >0.9 indicates a highly accurate model [16].

- These diverse AF2 models can serve as excellent starting points for either a single long simulation or an ensemble of short simulations, as they provide structurally plausible seeds across the conformational landscape.

Protocol C: Assessing Convergence in a Single Long Trajectory

This protocol provides methods to evaluate whether a long simulation has sampled sufficiently to yield reliable equilibrium properties [3].

Property Selection: Choose a set of properties relevant to your biological question. These can include:

- Global Properties: RMSD, Rg, total energy.

- Local Properties: RMSF, specific inter-residue distances, dihedral angles.

- Kinetic Properties: Implied timescales from an MSM.

Running Average Analysis:

- For a property ( A ), calculate the running average ( 〈A〉(t) ) from simulation time 0 to ( t ).

- Criteria for Convergence: The function ( 〈A〉(t) ) should fluctuate around a stable value with small deviations for a significant portion (e.g., the latter half) of the trajectory. The time at which this plateau begins is the convergence time, ( t_c ).

Interpretation:

- Be aware that a system can be in partial equilibrium, where some properties (e.g., local distances) have converged, while others (e.g., transition rates between low-probability states) have not [3].

- Claims of convergence should always be qualified by stating which properties were assessed.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Software and Resources for Conformational Sampling Studies

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Relevance to Sampling Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

| GROMACS [15] | MD Software | High-performance MD simulation engine. | Core tool for generating both long and short trajectories. |

| OpenMM [15] | MD Software | GPU-accelerated MD simulation toolkit. | Core tool for generating both long and short trajectories. |

| DGA Estimators [14] | Analysis Algorithm | Extracts long-timescale kinetics from short trajectories. | Essential for analyzing multiple short-trajectory datasets. |

| AlphaFold2 [16] | Structure Prediction | Predicts protein structures from sequence. | Generates diverse conformational seeds for simulations. |

| GPCRmd [15] | Specialized Database | Curated MD trajectories for GPCRs. | Source of validation data and system setups for membrane proteins. |

| ATLAS [15] | General MD Database | Large-scale database of protein MD simulations. | Provides reference data and benchmarks for simulation studies. |

| True Reaction Coordinates (tRCs) [17] | Theoretical Concept | Optimal collective variables that determine the committor. | Ideal CVs for guiding enhanced sampling in any strategy. |

| Manganese chloride | Manganese Chloride|High-Purity Reagent|RUO | High-purity Manganese Chloride (MnCl2) for industrial and biochemical research. For Research Use Only (RUO). Not for human consumption. | Bench Chemicals |

| Triclopyr | Triclopyr|Herbicide|CAS 55335-06-3 | Triclopyr is a systemic, auxin-mimicking herbicide for professional research use only. It is For Research Use Only (RUO), not for personal or agricultural application. | Bench Chemicals |

Implementing Multiple Short and Single Long Trajectory Strategies

The fundamental challenge of achieving sufficient sampling of conformational space lies at the heart of molecular dynamics (MD) simulation. Within this context, a critical strategic decision emerges: whether to employ a single, long simulation trajectory or multiple, shorter, independent simulations. This application note frames this debate within a broader thesis on sampling strategies, detailing the protocols and demonstrating the advantages of the multiple-independent-simulation approach for studying biomolecular systems, with a particular focus on aptamers and proteins. Evidence suggests that conducting multiple independent MD runs starting from different initial conditions is a promising approach to enhance equilibrium sampling, as it not only samples more broadly in the conformational space compared to a single long trajectory but also can provide more accurate estimates [6]. This strategy is particularly valuable for characterizing the conformation and dynamics of flexible molecules like RNA aptamers, where small conformational changes can significantly impact function [6].

Core Concept: Multiple Short Trajectories vs. One Long Run

The choice between multiple short trajectories and one long run hinges on the goal of obtaining a statistically representative ensemble of molecular conformations. A single long simulation risks being trapped in a local energy minimum, potentially missing important conformational states. In contrast, multiple independent simulations, initiated from a diverse set of starting structures, actively explore the energy landscape from different regions, mitigating the risk of such kinetic trapping [6].

A key study on an RNA aptamer provides compelling evidence for this approach. Researchers conducted 60 independent MD simulations, each 100 ns in duration, starting from ten different conformations derived from six distinct de novo predicted structures [6]. The analysis revealed that simulations initiated from different predicted models explored regions of conformational space that were not visited by other groups, and long simulations from different initial structures were found to be trapped in different states [6]. This underscores the necessity of using different initial configurations to achieve broad sampling. The approach of multiple short simulations helps avoid the problem of the molecule being trapped in a local minimum, an undesirable outcome that can skew the resulting conformational ensemble [6].

Quantitative Comparison of Sampling Strategies

The table below summarizes the performance outcomes observed in a case study comparing the two sampling strategies for an RNA aptamer [6].

Table 1: Quantitative Outcomes of Sampling Strategies from an RNA Aptamer Study

| Sampling Strategy | Number of Simulations | Simulation Length | Key Observation | Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multiple Independent Simulations | 60 | 100 ns each | Discovered more conformational states; identified under-sampled regions on the energy landscape [6] | Avoids kinetic trapping in local minima; provides broader coverage of conformational space [6] |

| Single Long Simulation | 1 | Equivalent aggregate length (e.g., 6 μs) | High risk of being trapped in a single state or a subset of states, leading to a non-representative ensemble [6] | Simpler setup; can better study slow, correlated motions if sampling is sufficient |

Detailed Protocol for Multiple Independent Simulations

This section provides a step-by-step methodology for implementing a multiple-independent-simulation strategy, based on established practices [6].

Generation of Diverse Initial Conformations

The first and most critical step is the preparation of a diverse set of initial structures to ensure simulations sample different regions of the energy landscape.

- Structure Source: For a molecule with no experimentally-determined structure, begin with de novo 3D structure prediction. The study on the NEO2A aptamer selected six configurations from prediction with various potential energy values [6].

- Initial Solvent Equilibration: Each of the predicted structures should be energy minimized in solution and then equilibrated with MD simulations at high temperature [6].

- Conformation Selection: From each of the high-temperature equilibration runs, select multiple conformations (e.g., 10) to serve as the initial structures for production runs at ambient temperature [6]. This results in a pool of starting conformations (e.g., 60) that are diverse in both structure and energy.

System Setup and Equilibration

A robust and consistent equilibration protocol is essential for all systems before initiating production simulations.

- Solvation and Ionization: Place the solute in an appropriate periodic box (e.g., dodecahedron) with a solvent model such as TIP3P water. Add ions to neutralize the system's charge and to achieve a physiologically relevant salt concentration.

- Energy Minimization: Perform energy minimization to remove any bad contacts, using a method like steepest descent or conjugate gradient, typically for several thousand steps or until the maximum force falls below a specified threshold (e.g., 1000 kJ/mol/nm). This step is often cycled with

gmx gromppandgmx mdrunin GROMACS [18]. - Equilibration MD:

- NVT Ensemble: Equilibrate the system with position restraints on the heavy atoms of the solute. This allows the solvent and ions to relax around the solute. Run for a sufficient time (e.g., 100-500 ps) until the temperature stabilizes at the target value (e.g., 300 K).

- NPT Ensemble: Equilibrate the system with position restraints on solute heavy atoms to adjust the density of the solvent. Run until the pressure and density stabilize (e.g., 100-500 ps).

The following workflow diagram outlines the key stages from initial structure preparation to the final production simulations.

Production Simulations and Analysis

- Launch Production Runs: Initiate multiple independent MD simulations (e.g., 60 runs of 100 ns each) from the pool of equilibrated starting conformations, using the same parameters (temperature, pressure, integrator, etc.) for all.

- Assess Sampling Performance: Employ a combination of analysis techniques to evaluate the quality and breadth of sampling:

- Potential Energy Distribution: Evaluate the distribution for the complete set of simulations to identify under-sampled regions on the energy landscape [6].

- Recurrence Quantification Analysis (RQA): Use RQA to examine the sampling of conformational transitions and the recurrence rate, which can indicate trapping [6].

- Principal Component Analysis (PCA): Project structures onto the first few principal components to visualize and compare the conformational regions sampled by different groups of simulations [6]. The expectation is a wide region of conformational space is sampled (global) and a partial overlap between different trajectories is achieved (local) [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials and Tools for Multiple Independent MD Simulations

| Item / Reagent | Function / Explanation | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| De Novo Structure Prediction | Generates initial 3D models when experimental structures are unavailable. | Provides the diverse set of starting configurations crucial for the protocol [6]. |

| All-Atom Force Field | Defines the potential energy function and parameters for the molecular system. | AMBER, CHARMM, OPLS-AA. Selection is critical for accurate dynamics [19]. |

| MD Simulation Software | Engine for running energy minimization, equilibration, and production dynamics. | GROMACS [18], AMBER, NAMD, OpenMM. |

| Solvent Model | Represents the aqueous environment in which the solute is embedded. | TIP3P, SPC/E, TIP4P water models. |

| Analysis Tools Suite | For processing trajectories and quantifying sampling performance. | Tools for PCA, RQA, RMSD, and potential energy calculation [6]. |

| Ceftaroline fosamil | Ceftaroline Fosamil|Anti-MRSA Cephalosporin for Research | Ceftaroline fosamil is a fifth-generation cephalosporin for research on MRSA and bacterial pneumonia. This product is for Research Use Only. |

| Arzoxifene | Arzoxifene Hydrochloride | Arzoxifene is a potent benzothiophene SERM for cancer and osteoporosis research. This product is for Research Use Only (RUO). Not for human use. |

The strategic decision to employ multiple independent, short simulations over a single long run is justified when the objective is broad exploration of a biomolecule's conformational landscape. This approach directly addresses the problem of kinetic trapping in local energy minima, a common pitfall in MD simulations. The recommended practice is to initiate simulations from a diverse set of initial conformations, often derived from de novo structure prediction, and to rigorously assess convergence using a suite of analytical methods including potential energy distributions, PCA, and RQA. For researchers studying flexible systems like aptamers or intrinsically disordered proteins, this protocol provides a robust framework for achieving sufficient sampling and generating a representative conformational ensemble.

The fundamental challenge of achieving sufficient sampling in molecular dynamics (MD) simulations is a central concern in computational biology and drug development. The conventional approach of employing a single, long simulation trajectory is often hindered by the problem of kinetic trapping, where the simulation becomes stuck in a local minimum of the potential energy landscape, failing to explore other functionally relevant conformational states [6]. This case study examines the alternative sampling strategy of conducting multiple short, independent MD trajectories, demonstrating its efficacy in preventing trapping and enhancing the exploration of conformational space. Framed within a broader thesis on sampling strategies, this analysis provides application notes and detailed protocols for researchers aiming to implement this method, particularly in the context of drug design where understanding a protein's complete conformational ensemble is crucial for identifying allosteric sites and mechanisms.

Theoretical Foundation: Local Minima and Sampling

The Problem of Local Minima in MD Simulations

In MD simulations, a local minimum represents a metastable conformational state that is stable to small perturbations but is not the global minimum on the potential energy landscape. The complex, high-dimensional energy landscape of biomolecules, such as proteins and RNA, is characterized by numerous such local minima, separated by energy barriers of varying heights [6]. When a simulation is kinetically trapped, it samples only a limited region of conformational space, leading to a non-ergodic sample that does not represent the true thermodynamic equilibrium of the system. This can result in biased estimations of key properties, such as binding free energies, conformational populations, and dynamic correlations, ultimately reducing the predictive power of the simulation [6].

Multiple Short Runs vs. One Long Run

The strategy of using multiple short runs, each initiated from a different starting conformation, provides a direct solution to the problem of local minima. While a single long simulation might remain trapped within one large energy basin for its entire duration, a set of independent shorter simulations, starting from diverse points in conformational space, can simultaneously explore multiple basins [6]. This approach offers several key advantages:

- Enhanced Exploration: A single long trajectory might spend a great deal of time exhaustively sampling a local minimum before overcoming a large barrier to a new region. Multiple short runs, by starting from different points, can immediately begin sampling distinct regions of the energy landscape.

- Parallelizability: Independent simulations can be run concurrently on high-performance computing clusters, drastically reducing the wall-clock time required to achieve broad sampling.

- Robustness: The aggregate ensemble from multiple runs is less likely to be biased by a single, unfortunate initial condition that leads to immediate trapping.

Table: Comparative Analysis of Sampling Strategies

| Feature | Single Long Trajectory | Multiple Short Trajectories |

|---|---|---|

| Risk of Kinetic Trapping | High | Lower |

| Exploration Speed | Slow for broad exploration | Fast for broad exploration |

| Computational Efficiency | Less efficient for conformational space coverage | More efficient for conformational space coverage |

| Error Estimation | Difficult | Possible from between-trajectory variances |

| Parallelization | Limited | Excellent |

Quantitative Data and Analysis

A study on an RNA aptamer provides compelling quantitative evidence for the superiority of the multiple short-run strategy. Researchers conducted 60 independent MD simulations, each 100 ns in duration, starting from ten different conformations derived from six distinct de novo predicted structures [6]. The analysis revealed that simulations initiated from the same predicted model helped avoid local energy minima traps. Furthermore, groups of simulations starting from different predicted models were able to sample unique regions of the principal component space that were not visited by other groups, demonstrating a more comprehensive exploration of the conformational landscape [6].

This approach was also shown to be critical for quantifying differences in conformational ensembles, a common task in structure-function studies. Research on beta-lactamase proteins demonstrated that statistically significant differences between native and mutant pairs could be discerned from relatively short MD trajectories (50-100 ns) using advanced statistical measures, underscoring the utility of multiple replicates for robust comparative analysis [20].

Table: Summary of Key Findings from the RNA Aptamer Case Study [6]

| Metric | Finding |

|---|---|

| System | NEO2A RNA Aptamer (25 nucleotides) |

| Simulation Setup | 60 independent simulations, each 100 ns |

| Initial Structures | 10 conformations from 6 de novo predicted models |

| Primary Result | Different initial configurations explored non-overlapping regions of conformational space |

| Recurrence Quantification Analysis | Consistent conformational transitions across groups |

| Conclusion | Multiple independent simulations avoid kinetic traps and achieve sufficient sampling |

Application Notes: Protocols and Workflows

Protocol for Multiple Independent MD Simulations

The following workflow is recommended for setting up and executing a study using multiple short MD trajectories.

Step 1: Generation of Diverse Initial Structures

The success of this strategy hinges on the diversity of the starting conformations.

- For proteins/RNAs with known experimental structures: Use available structures from the PDB. If multiple structures are available, use them all.

- For systems with no known structure: Employ de novo 3D structure prediction tools to generate a set of plausible initial models. For the RNA aptamer study, six configurations were selected from de novo prediction with various potential energy values [6].

- Enhancing Diversity: For each distinct configuration (e.g., each predicted model), generate several conformations by:

- Performing energy minimization in solution.

- Running short MD equilibration runs at high temperature.

- Sampling multiple snapshots from these equilibration runs. The RNA aptamer study used 10 conformations per predicted model [6].

Step 2: System Setup and Equilibrium

For each initial conformation:

- Solvation and Ionization: Place the structure in an appropriate solvent box (e.g., TIP3P water) and add ions to neutralize the system and achieve physiological concentration.

- Energy Minimization: Use steepest descent or conjugate gradient methods to remove bad steric clashes.

- Equilibration:

- Perform a short NVT simulation to stabilize the temperature.

- Follow with an NPT simulation to adjust the density and pressure of the system to the target values (e.g., 1 bar).

Step 3: Production Runs

- Launch independent production simulations from each equilibrated starting structure. The simulations should be conducted in parallel.

- The length of each simulation should be sufficient to overcome local barriers surrounding the starting point. A duration of 100 ns is a common starting point for moderate-sized systems [6].

- Ensure consistent simulation parameters (force field, temperature, pressure) across all runs.

Step 4: Analysis and Ensemble Validation

- Convergence Assessment: Use Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to project trajectories from different starting points onto a common set of collective variables. Plot the density of these projections to check for overlap and identify regions sampled uniquely by different groups of simulations [6].

- Recurrence Quantification Analysis (RQA): Use RQA to examine the sampling of conformational transitions and compare the recurrence rates and dependence on initial conformation among different groups of simulations [6].

- Potential Energy Landscape: Plot the potential energy distribution for the entire set of simulations to identify any remaining undersampled regions [6].

Workflow Visualization

Diagram 1: High-level workflow for multiple short run MD strategy.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Software

Table: Essential Tools for MD Sampling Studies

| Tool/Reagent | Type | Function | Availability |

|---|---|---|---|

| GROMACS | MD Software Suite | High-performance simulation engine with integrated analysis tools [21]. | Freely available |

| AMBER | MD Software Suite | Includes AmberTools and PMEMD for simulation and analysis. | Commercial & Free components |

| MDAnalysis | Python Library | Flexible framework for analyzing MD trajectories; supports multiple file formats [21]. | Freely available on GitHub |

| MDTraj | Python Library | Fast and efficient trajectory analysis; integrates with NumPy/SciPy [21]. | Freely available |

| VMD | Visualization Software | Visualization, animation, and analysis of structures and trajectories [21]. | Freely available |

| CPPTRAJ | Analysis Program | Versatile trajectory analysis tool within AmberTools [21]. | Freely available |

| PLUMED | Enhanced Sampling Plugin | Used for enhanced sampling, free energy calculations, and analysis [21]. | Freely available |

| Methyl tricosanoate | Methyl Tricosanoate|2433-97-8|High-Purity Reference Standard | Bench Chemicals | |

| CP-346086 | CP-346086, MF:C26H22F3N5O, MW:477.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

This case study establishes that a sampling strategy based on multiple short, independent MD trajectories is a powerful and efficient method for mitigating the risk of kinetic trapping in local energy minima. By leveraging diverse initial structures and the inherent parallelizability of independent runs, researchers can achieve a more comprehensive exploration of a biomolecule's conformational landscape within a practical timeframe. The provided protocols and toolkit offer a clear roadmap for scientists in drug development to implement this strategy, thereby enhancing the reliability of their simulations for tasks ranging from understanding protein function and mutation effects to the structure-based design of novel therapeutics.

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations provide insights into the dynamic behavior of biomolecules, which is critical for understanding their function. A central question in the field involves sampling strategy: whether to use one long MD trajectory or multiple short trajectories. This choice directly impacts the efficiency and accuracy of calculating experimental observables, such as Nuclear Overhauser Effect (NOE) data, which are crucial for determining 3D molecular structures. This application note explores the MD2NOE software, which calculates NOEs directly from MD trajectories, providing a framework for evaluating different sampling strategies within drug discovery and structural biology.

Theoretical Background: Beyond the Inverse Sixth Power Assumption

Traditional methods for interpreting NOEs in structural biology often rely on the inverse sixth power average of inter-proton distances (( \langle r^{-6} \rangle )). This approach assumes that internal molecular motions and overall molecular reorientation are uncorrelated, which simplifies the relationship between NOE build-up rates and inter-nuclear distances [22] [23]. While valid for rigid molecules, this assumption breaks down for flexible molecules that sample multiple conformational states.

The MD2NOE software addresses this limitation by calculating dipole-dipole correlation functions directly from the MD trajectory, without using the averaged ( r^{-6} ) term as an intermediate [22] [23]. This direct method is particularly crucial for molecules like intrinsically disordered proteins, oligomeric carbohydrates, and single-stranded polynucleotides, where internal motions occur on timescales similar to molecular reorientation, making angular and distance variations inseparable [22]. The core correlation function calculated by MD2NOE is given by:

[ C(\tau)=(dd)^2 \left\langle \frac{1}{r^3(t)} \times Y2^0(\Omega(t)) \times \frac{1}{r^3(t+\tau)} \times Y2^0(\Omega(t+\tau)) \right\rangle_t ]

Where ( dd ) is the dipolar interaction constant, ( r(t) ) is the inter-nuclear distance, and ( Y_2^0 ) are spherical harmonics dependent on the orientation ( \Omega ) of the inter-nuclear vector [22]. This direct approach properly accounts for the complex interplay between internal and overall motion, leading to more accurate NOE predictions for flexible molecular systems.

MD2NOE Software Package and Workflow

Implementation and Architecture

MD2NOE is part of a broader suite of C++ command-line programs designed to evaluate MD trajectories and simulate various NMR observables, including spin-lattice relaxation rates, spin-spin relaxation rates, and 3JHH scalar couplings [22] [23]. The software runs under LINUX operating systems and is publicly available at glycam.org/nmr.

Integrated Workflow Modules

The MD2NOE workflow consists of three integrated modules that transform raw MD data into comparable NOE predictions:

Module 1: Input Processing ingests MD trajectories generated by AMBER simulation software along with associated topology files [22].

Module 2: Trajectory Validation assesses whether the simulation has adequately sampled conformational states and achieved steady-state behavior. This module includes auxiliary tools like "TRAJECTORY," which generates plots and text files showing inter-nuclear distances for selected proton pairs as a function of time, allowing researchers to verify that the simulation has reached a stable equilibrium [22].

Module 3: NOE Calculation computes correlation functions for pairwise dipolar interactions directly from the validated trajectory and incorporates the resulting relaxation parameters into a complete relaxation matrix analysis to generate simulated NOE build-up curves for comparison with experimental data [22] [23].

Sampling Strategy: Multiple Short vs. Single Long Trajectories

The core thesis context of sampling strategy presents a significant methodological consideration when using MD2NOE. Each approach offers distinct advantages for conformational sampling and property calculation.

Table: Comparison of MD Sampling Strategies for NOE Calculation

| Feature | Single Long Trajectory | Multiple Short Trajectories |

|---|---|---|

| Timescale Sampling | Ideal for processes slower than overall tumbling [22] | Better for rapid local fluctuations [10] |

| Correlation Function | Directly captures slow motions & complex dynamics [22] | May miss slow conformational transitions |

| Statistical Independence | Sequential time points are correlated | Independent starting points enhance sampling diversity |

| Computational Efficiency | Requires continuous long-time access to resources | Can be distributed across multiple processors [10] |

| Error Assessment | Limited to block averaging approaches | Enables statistical comparison across replicates |

| System Size Limitation | More challenging for large systems | More accessible for large biomolecular complexes |

Enhanced Sampling Techniques

For systems with rough energy landscapes and high energy barriers, enhanced sampling methods can improve the efficiency of both single long and multiple short trajectory approaches:

- Replica-Exchange MD (REMD): Simultaneously runs multiple simulations at different temperatures, allowing exchanges between replicas to overcome energy barriers [1].

- Metadynamics: Adds a history-dependent bias potential to discourage revisiting previously sampled states, effectively "filling free energy wells with computational sand" to encourage exploration of new regions [1].

- Simulated Annealing: Gradually reduces an artificial temperature during simulation, helping the system escape local minima and approach a global minimum configuration [1].

Experimental Protocol: Application to Sucrose

System Setup and Trajectory Generation

The developers of MD2NOE validated their approach using sucrose as a model system, following this detailed protocol:

Force Field and Solvent Selection:

Simulation Parameters:

Trajectory Analysis with MD2NOE

Input Preparation: Provide the AMBER topology and trajectory files to MD2NOE Module 1 [22].

Trajectory Validation:

NOE Calculation:

- Module 3 calculates correlation functions for all relevant proton pairs directly from the trajectory [22].

- The software computes spectral density functions and cross-relaxation rates using the formula: [ \sigma{i,j} = \frac{(dd)^2}{4} \left{ -J{ij}(0) + 6J{ij}(2\omega) \right} ] where ( J{ij} ) is the spectral density function for proton pair (i,j) [22].

- A complete relaxation matrix analysis generates NOE build-up curves for comparison with experiment [22] [23].

Results and Comparison to Traditional Methods

Application to sucrose revealed "small but significant" differences between NOEs calculated by MD2NOE and those derived using traditional inverse sixth-power averaging [22] [23]. The direct calculation approach of MD2NOE demonstrated that the timescales of internal motion and overall reorientation are not fully separable for sucrose, validating the importance of the direct trajectory analysis method for flexible molecules [23].

Table: Research Reagent Solutions for MD2NOE Experiments

| Reagent/Resource | Function in Protocol |

|---|---|

| AMBER MD Software | Generates input trajectories using validated force fields [22] [23] |

| GLYCAM06 Force Field | Provides parameters for carbohydrates like sucrose [22] [23] |

| TIP3P Water Model | Explicit solvent for realistic solvation environment [22] [23] |

| GPU Computing Resources | Enables microsecond-timescale trajectories [22] [10] |

| LINUX Operating System | Required platform for running MD2NOE software [22] |

MD2NOE represents a significant advancement for calculating NMR observables directly from MD trajectories, avoiding simplifying assumptions that limit traditional approaches. For researchers investigating the debate between single long versus multiple short trajectory sampling strategies, MD2NOE provides a quantitative framework for evaluation. The software enables direct comparison of NOE predictions from different sampling approaches against experimental data, offering insights into which strategy better captures the complex dynamics of flexible biomolecules. As MD simulations continue to reach longer timescales through hardware and software advances, tools like MD2NOE will play an increasingly important role in bridging the gap between simulation and experiment in structural biology and drug discovery.

The identification of novel binding sites is a fundamental challenge in structure-based drug discovery. A significant number of therapeutically relevant proteins have been classified as "undruggable" due to the absence of well-defined, stable binding pockets in their ground-state structures [24] [25]. Cryptic pockets—transient binding sites that are not apparent in static crystal structures but become favorable for ligand binding in the presence of a ligand or through protein dynamics—provide a promising avenue to target these challenging proteins [25]. The discovery of the Switch-II pocket in the KRAS protein, which led to FDA-approved drugs after decades of the target being considered undruggable, stands as a seminal example of the therapeutic potential of cryptic pockets [26].