Integrating Molecular Dynamics and Pharmacophore Modeling in Modern Drug Discovery: From Dynamic Insights to Clinical Candidates

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the integration of Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations and pharmacophore modeling to address critical challenges in structure-based drug discovery.

Integrating Molecular Dynamics and Pharmacophore Modeling in Modern Drug Discovery: From Dynamic Insights to Clinical Candidates

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the integration of Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations and pharmacophore modeling to address critical challenges in structure-based drug discovery. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles of capturing target flexibility and deriving dynamic pharmacophores from MD trajectories. The content details advanced methodologies like the Relaxed Complex Scheme and conformer coverage approaches for virtual screening, alongside practical strategies for troubleshooting sampling limitations and scoring inaccuracies. Further, it examines rigorous validation techniques and comparative analyses of these dynamic methods against static docking, synthesizing key takeaways and future directions for improving the efficiency and success rate of lead identification and optimization in biomedical research.

Beyond Static Structures: How Molecular Dynamics Reveals the Functional Flexibility of Drug Targets

In the field of structure-based drug discovery (SBDD), molecular docking serves as a cornerstone methodology for predicting how small molecule ligands interact with biological targets. Traditional docking simulations, however, operate on a fundamental limitation: they largely treat the protein receptor as a static entity, failing to adequately capture the dynamic nature of biomolecular recognition [1]. This "static snapshot" paradigm stands in stark contrast to the physiological reality that proteins exhibit considerable structural flexibility, undergoing conformational changes ranging from side-chain rotations to large-scale domain movements upon ligand binding [2] [3]. The assumption of rigidity represents a critical vulnerability in docking pipelines, particularly for large multimeric complexes and systems undergoing significant conformational transitions during their functional cycles [4].

The limitations of this static approach manifest in several practical challenges. Traditional docking tools typically allow high flexibility for the ligand but keep the protein fixed or provide only limited flexibility to residues near the active site, dramatically increasing the computational complexity of simulations [3]. This simplification neglects crucial phenomena such as induced fit binding, where the binding site reshapes itself to accommodate the ligand, and conformational selection, where ligands selectively bind to pre-existing protein conformations from a dynamic ensemble [1]. Consequently, the static approximation impedes accurate prediction of binding modes and affinities, especially for the growing number of targets characterized by cryptic allosteric pockets that only emerge during protein dynamics [3]. Overcoming these limitations requires a paradigm shift toward dynamics-aware approaches that explicitly incorporate protein flexibility into the drug discovery workflow.

Quantitative Assessment: How Structural Flexibility Impacts Docking Outcomes

The influence of protein flexibility on docking outcomes has been systematically evaluated through rigorous computational studies. Recent research examining large, dynamic complexes like the mitochondrial chaperonin Hsp60—a double-ring complex that cycles through apo, ATP-bound, and ATP–Hsp10 states—demonstrates that structural relaxation profoundly reshapes the docking landscape [4]. In this system, different levels of receptor preparation (energy minimization alone versus more extensive molecular dynamics equilibration) led to significantly different predicted binding sites, including the central cavity, equatorial ATP pocket, and apical domain [4].

The relationship between conformational change and docking success rates has been quantitatively analyzed in protein-protein docking benchmarks. The data reveal a clear trend: as the unbound-to-bound root mean square deviation (RMSDUB) increases, indicating greater structural flexibility, the success rates of conventional docking methods decline substantially [5]. This performance degradation is particularly pronounced for antibody-antigen systems, which often exhibit considerable flexibility and pose challenges for static docking approaches.

Table 1: Docking Success Rates as a Function of Conformational Flexibility

| Flexibility Category | RMSDUB Range (Ã…) | ReplicaDock 2.0 Success Rate | AlphaRED Success Rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rigid | ≤ 1.1 | 80% | Not Reported |

| Medium | 1.1 - 2.2 | 61% | Not Reported |

| Difficult/Flexible | ≥ 2.2 | 33% | 63% (overall) |

| Antibody-Antigen | Variable | Not Reported | 43% |

The performance gap highlighted in Table 1 underscores a critical limitation: physics-based docking methods like ReplicaDock 2.0 achieve only a 33% success rate for highly flexible targets (RMSDUB ≥ 2.2 Å), despite stronger performance with more rigid systems [5]. This precipitous drop in accuracy reflects the fundamental challenge that large-scale conformational changes—including loop motions, domain rearrangements, and hinge-like movements—pose to static or semi-flexible docking algorithms [5]. These limitations extend beyond protein-protein interactions to significantly impact small-molecule docking as well, where the failure to account for binding site plasticity can lead to inaccurate pose prediction and virtual screening failures.

Beyond Rigidity: Methodological Frameworks for Incorporating Dynamics

The Relaxed Complex Scheme (RCS)

The Relaxed Complex Scheme (RCS) represents a systematic approach to incorporate protein flexibility by leveraging molecular dynamics (MD) simulations to generate diverse receptor conformations for docking studies [3]. This method addresses the conformational selection aspect of molecular recognition by explicitly sampling the protein's structural ensemble prior to docking simulations. The workflow begins with extensive MD sampling of the target protein, capturing its dynamic behavior across relevant timescales. Representative snapshot structures are then extracted from the trajectory, selected to maximize conformational diversity while focusing on biologically relevant states. These structures serve as multiple receptor conformations in subsequent docking calculations, allowing ligands to be screened against an ensemble of potential binding sites rather than a single static structure [3].

The RCS has demonstrated particular value in identifying cryptic pockets—transient binding sites not evident in crystal structures that emerge during protein dynamics. These pockets often play crucial roles in allosteric regulation and offer novel targeting opportunities beyond primary endogenous binding sites [3]. An early successful application of this dynamics-aware approach contributed to the development of the first FDA-approved inhibitor of HIV integrase, where MD simulations revealed significant flexibility in the active site region that informed inhibitor design [3].

Integrated Deep Learning and Physics-Based Docking

Recent methodologies have integrated deep learning (DL) approaches with physics-based docking to address protein flexibility. The AlphaRED (AlphaFold-initiated Replica Exchange Docking) pipeline exemplifies this strategy by combining AlphaFold-multimer (AFm) as a structural template generator with replica exchange docking to sample conformational changes [5]. This hybrid approach leverages the complementary strengths of both methodologies: AFm provides evolutionarily informed structural models, while the physics-based replica exchange enables enhanced sampling of binding poses.

The protocol employs AlphaFold's built-in confidence metrics—particularly the predicted Local Distance Difference Test (pLDDT) and Predicted Aligned Error (PAE)—to identify potentially flexible regions and estimate docking accuracy [5]. These regions are then targeted for enhanced sampling in the ReplicaDock 2.0 stage, which applies temperature replica exchange molecular dynamics to overcome energy barriers and explore alternative conformations [5]. This integrated pipeline demonstrates significantly improved performance for challenging targets, achieving acceptable-quality predictions for 63% of benchmark targets and raising the success rate for difficult antibody-antigen complexes from 20% with AFm alone to 43% with AlphaRED [5].

Enhanced Sampling Molecular Dynamics

Accelerated molecular dynamics (aMD) and other enhanced sampling techniques provide complementary approaches to address the timescale limitations of conventional MD simulations [3]. By adding a non-negative boost potential to the system's energy landscape, aMD methods reduce energy barriers and accelerate transitions between different low-energy states, enabling more efficient exploration of the conformational space [3]. This capability is particularly valuable for studying slow biological processes and large-scale conformational changes relevant to drug binding.

These methods can capture rare events and transitions between conformational states that would be computationally prohibitive to observe with standard MD. The enhanced conformational sampling facilitates the identification of cryptic pockets and allosteric sites that emerge transiently during protein dynamics, expanding the targetable landscape for therapeutic intervention [3]. When combined with docking workflows, enhanced sampling provides a more comprehensive representation of the receptor's conformational ensemble, leading to improved virtual screening outcomes and more accurate binding mode predictions.

Practical Implementation: Protocols for Dynamic Docking

Structure Preparation and Refinement Protocol

The initial preparation of protein structures significantly influences docking outcomes, especially for large multimeric complexes [4]. The following protocol ensures properly refined starting structures:

- Structure Retrieval and Assessment: Obtain experimental structures from the PDB or generate models using predictive tools like AlphaFold2 [6] [4]. For homology modeling, tools like Modeller can be employed when experimental structures are unavailable [6].

- Quality Validation: Evaluate model quality using metrics such as MolProbity clashscore, Ramachandran plot analysis, and Verify3D to ensure proper geometry and side-chain conformations [4].

- Structure Relaxation: Apply energy minimization to relieve steric clashes and optimize hydrogen bonding networks. For more extensive relaxation, perform molecular dynamics equilibration in explicit solvent to sample native-state fluctuations [4].

- Ensemble Generation: For the Relaxed Complex Scheme, run multiple independent MD simulations (typically 100 ns to μs timescales, depending on system size and flexibility) to generate conformational diversity [3].

- Snapshot Selection: Extract representative structures from MD trajectories using clustering algorithms (e.g., based on backbone RMSD) to capture distinct conformational states while minimizing redundancy [3].

Dynamic Docking Workflow Using AlphaRED

The AlphaRED protocol integrates deep learning with physics-based docking for challenging flexible targets:

- Input Preparation: Provide amino acid sequences for all binding partners. For proteins with known conformational heterogeneity, consider including experimental constraints from mutagenesis or spectroscopic data.

- AlphaFold-multimer Execution: Run AFm with multiple recycles (typically 3-5) and without templates to generate initial complex models [5]. The ColabFold implementation provides accessible execution.

- Confidence Metric Analysis: Extract pLDDT and PAE values from AFm output. Residues with pLDDT < 70 or high PAE values indicate regions of potential flexibility or uncertainty [5].

- Flexibility-Focused Docking: Input AFm models and flexibility metrics to ReplicaDock 2.0. The algorithm applies temperature replica exchange with backbone moves concentrated on identified flexible regions [5].

- Pose Analysis and Selection: Cluster docking trajectories and select representative poses based on energy rankings and structural similarity to known binding modes when available.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Dynamic Docking

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold2/ColabFold [4] [5] | Deep Learning | Protein structure prediction | Generates initial structural templates; provides confidence metrics |

| ReplicaDock 2.0 [5] | Physics-Based Docking | Enhanced sampling docking | Targets flexible regions identified by AFm; uses replica exchange |

| GROMACS/AMBER [2] | Molecular Dynamics | Conformational sampling | Generates structural ensembles for Relaxed Complex Scheme |

| MolProbity [4] | Validation | Structure quality assessment | Evaluates model geometry pre- and post-docking |

| ZDOCK/HADDOCK [4] | Protein-Protein Docking | Complex structure prediction | Alternative docking engines for specific systems |

Pharmacophore Modeling from Dynamic Ensembles

Pharmacophore models derived from dynamic structural ensembles more accurately represent the essential features required for molecular recognition:

- Ensemble-Based Pharmacophore Generation: Develop pharmacophores from multiple protein conformations rather than a single structure. Align snapshots from MD trajectories and identify conserved interaction features across the ensemble [6] [7].

- Feature Extraction: For each conformation, identify key pharmacophoric features including hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, hydrophobic areas, positively/negatively ionizable groups, and aromatic rings using tools like LigandScout or Phase [6] [7].

- Consensus Pharmacophore: Derive a consensus model containing features present above a defined frequency threshold (e.g., >70% of conformations) to ensure robustness against transient structural fluctuations [7].

- Exclusion Volume Management: Represent binding site shape using exclusion volumes, but consider making these volumes soft or adjustable to account for minor side-chain movements [6].

- Dynamic Pharmacophore Screening: Implement partial feature matching or weighted scoring to accommodate ligands that may not satisfy all pharmacophore elements simultaneously in every conformational state [7].

The integration of protein dynamics into docking methodologies represents a necessary evolution beyond the static snapshot paradigm. As the field progresses, several emerging trends promise to further advance dynamic docking approaches. The growing availability of ultra-large chemical libraries containing billions of compounds creates both opportunities and challenges for dynamics-aware screening [3]. Combining dynamic docking with machine learning-based scoring functions may help address the computational demands of screening these expansive chemical spaces against conformational ensembles [3].

Methodologically, we anticipate increased integration of experimental data from cryo-EM, NMR, and hydrogen-deuterium exchange mass spectrometry to inform and validate dynamic docking models [4]. The development of multi-scale methods that combine coarse-grained and all-atom simulations will enable the study of larger complexes and longer timescales [1]. Furthermore, the explicit prediction of binding kinetics alongside affinity will likely become more prevalent, as residence times often correlate better with in vivo efficacy than equilibrium binding measures [1].

The convergence of more accurate force fields, enhanced sampling algorithms, specialized hardware, and integrative modeling approaches will continue to push the boundaries of what is possible in simulating biomolecular recognition. As these methodologies mature and become more accessible, dynamic docking will transition from a specialized technique to a standard component of the drug discovery pipeline, ultimately enabling more effective targeting of the flexible nature of biological systems for therapeutic intervention.

Molecular Dynamics as a Tool for Sampling the Protein Conformational Landscape

Within modern drug discovery, understanding the full spectrum of shapes a protein can adopt is crucial for identifying therapeutic compounds. Proteins are inherently dynamic, and their function is intimately tied to their ability to shift between different conformations [8]. Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulation provides a powerful computational microscope to observe and sample this conformational landscape, predicting the motions of every atom in a protein over time [9]. This capability is particularly valuable in the context of pharmacophore development, as the ensemble of protein conformations, rather than a single static structure, often reveals the true functional topology of binding sites necessary for effective drug design [6]. This document details the application of MD for conformational sampling, providing protocols and resources to guide researchers in this field.

Core MD Methodologies for Conformational Sampling

Several MD methodologies enable efficient exploration of a protein's conformational space. The table below summarizes the key characteristics of prominent approaches.

Table 1: Key Methodologies for Sampling the Protein Conformational Landscape

| Methodology | Spatial/Temporal Resolution | Primary Application in Conformational Sampling | Key Advantages | Inherent Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All-Atom MD (AAMD) [9] | Atomic (Ã…); Nanoseconds to Microseconds | Directly simulates atomistic motions and folding/unfolding transitions. | High fidelity; Models explicit solvent and chemical details. | Computationally expensive; limited by time-step and system size. |

| Coarse-Grained (CG) Models [10] | Reduced (2-4 beads per amino acid); Microseconds to Milliseconds | Exploring large-scale conformational changes and folding of larger proteins. | ~100-1000x faster than AAMD; efficient for large systems. | Loss of atomic detail; requires parameterization from AAMD or experiments. |

| Machine-Learned CG Models [10] | Reduced; comparable to CG. | Transferable prediction of folded, unfolded, and intermediate states across protein sequences. | Several orders of magnitude faster than AAMD; quantitatively predictive for folding free energies. | Dependent on quality and diversity of training data; a "black box" model. |

| Deep Generative Models (DGMs) [8] | Atomic or reduced; instantaneous sampling from a learned distribution. | Rapid generation of statistically independent conformations that reflect the equilibrium ensemble. | Bypasses slow simulation timescales; directly models equilibrium distribution. | May not capture precise dynamical pathways; training and validation are complex. |

| Enhanced Sampling Methods (e.g., Umbrella Sampling [8]) | Atomic; biased simulation time. | Calculating free energies and sampling rare events (e.g., ligand binding, large conformational shifts). | Systematically drives sampling along predefined reaction coordinates. | Requires a priori knowledge of key collective variables; can be computationally intensive. |

The workflow for applying these methods typically involves a multi-scale approach, beginning with structure preparation and moving through various sampling strategies to achieve a representative ensemble.

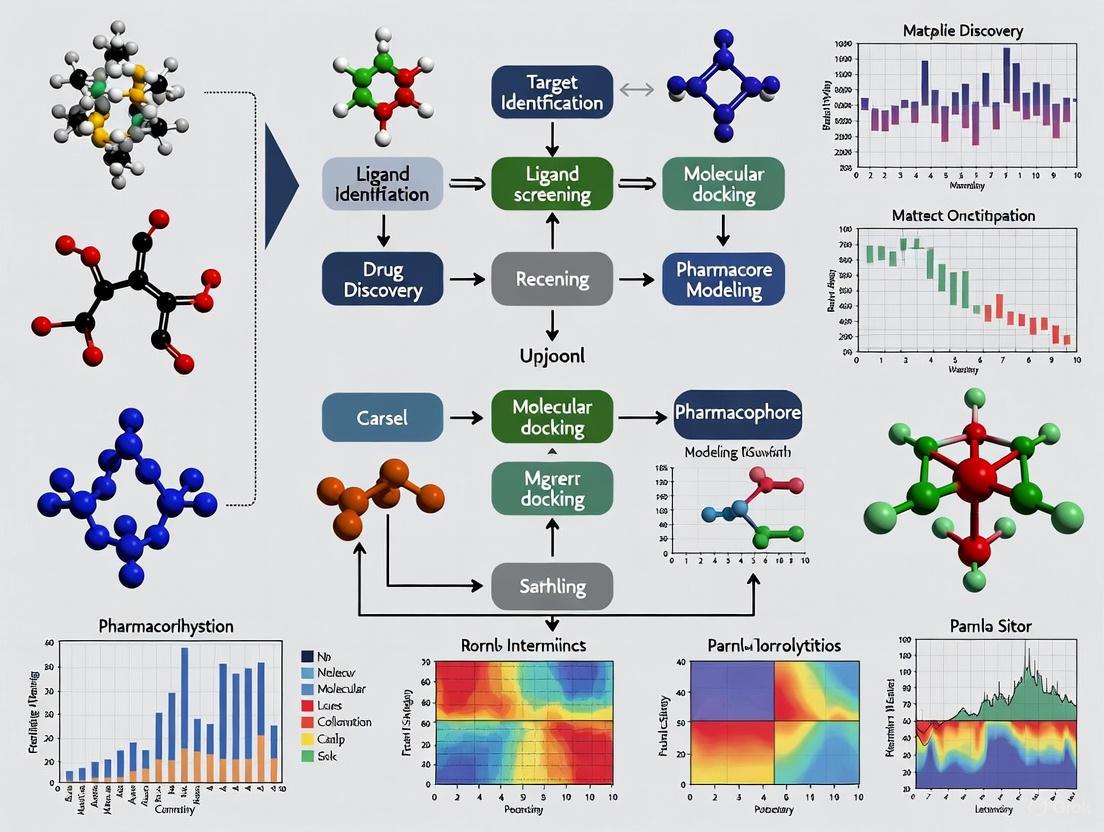

Figure 1: A multi-scale workflow for sampling the protein conformational landscape, from initial structure preparation to application in drug discovery. PDB: Protein Data Bank.

Application Notes & Protocols

Protocol: Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling from an MD Ensemble

This protocol leverages an ensemble of protein conformations generated by MD to create a robust, structure-based pharmacophore model for virtual screening [6].

Objective: To develop a dynamic pharmacophore model that accounts for protein flexibility, increasing the likelihood of identifying novel bioactive compounds in virtual screens.

Materials & Software:

- Hardware: High-Performance Computing (HPC) cluster.

- Software: MD simulation package (e.g., GROMACS [9], AMBER [9], NAMD [9]); molecular visualization software (e.g., PyMOL, Chimera); pharmacophore modeling software (e.g., LigandScout, MOE).

- Input: A high-quality 3D structure of the target protein (from PDB or homology modeling) [6].

Procedure:

- System Preparation:

- MD Simulation & Conformational Sampling:

- Run an all-atom MD simulation for a duration sufficient to observe relevant conformational changes (e.g., hundreds of nanoseconds to microseconds).

- Save trajectory frames at regular intervals (e.g., every 100-500 ps).

- Cluster the saved frames from the trajectory based on structural similarity (e.g., using Cα root-mean-square deviation) to identify representative conformations.

- Binding Site Analysis:

- For each representative cluster structure, analyze the key binding pocket.

- Identify and map critical interaction features: Hydrogen Bond Donors (HBD), Hydrogen Bond Acceptors (HBA), Hydrophobic areas (H), Positively/Negatively Ionizable groups (PI/NI), and Aromatic rings (AR) [6].

- Pharmacophore Hypothesis Generation:

- Generate an individual structure-based pharmacophore model for each representative conformation, defining the spatial arrangement of the identified chemical features.

- To create a consensus pharmacophore model, align all models and identify features that are conserved across the majority of the MD ensemble.

- Model Validation & Virtual Screening:

- Validate the model by screening a small database of known actives and decoys to ensure it can selectively retrieve active compounds.

- Use the validated pharmacophore model as a query to perform virtual screening of large compound libraries to identify novel candidate molecules [6].

Protocol: Employing a Machine-Learned Coarse-Grained Model for Folding Landscapes

This protocol utilizes a state-of-the-art machine-learned coarse-grained model to efficiently explore the folding free energy landscape of a protein, a task that is often prohibitively expensive for all-atom MD [10].

Objective: To predict the metastable states (folded, unfolded, intermediate) and relative folding free energies of a protein or its mutants with high computational efficiency.

Materials & Software:

- Hardware: HPC cluster or modern workstation with a powerful GPU.

- Software: A machine-learned CG model (e.g., CGSchNet [10]); simulation and analysis tools compatible with the model.

- Input: The amino acid sequence of the target protein.

Procedure:

- System Setup:

- Input the amino acid sequence of the protein of interest into the CG model. The model is "transferable," meaning it can be applied to sequences not included in its training set [10].

- Enhanced Sampling Simulation:

- Perform parallel-tempering or long constant-temperature simulations using the learned CG force field to ensure converged sampling of the equilibrium distribution.

- Free Energy Surface Calculation:

- Construct the free energy landscape as a function of collective variables, such as the fraction of native contacts (Q) and Cα root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) from a reference native structure.

- Identify the distinct free energy minima, which correspond to metastable conformational states.

- Analysis of States and Dynamics:

- Analyze the structures within each free energy minimum to characterize the folded native state, any intermediate states, and the unfolded ensemble.

- Compare the predicted Cα root-mean-square fluctuations (RMSF) of the folded state with available experimental data or all-atom MD simulations to validate the model's accuracy [10].

- For protein mutants, calculate the relative folding free energy (ΔΔG) between the wild-type and mutant proteins by comparing the stability of their folded states.

Table 2: Key Resources for MD-Based Conformational Sampling

| Resource Category | Example(s) | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| Force Fields | CHARMM, AMBER, GROMOS [9] | Empirical potential energy functions that define interatomic interactions, determining the accuracy and realism of an MD simulation. |

| MD Simulation Software | GROMACS, AMBER, NAMD [9] | Integrated software suites used to set up, run, analyze, and visualize MD simulations. |

| Machine-Learned CG Models | CGSchNet [10] | A transferable, bottom-up coarse-grained force field that predicts protein landscapes orders of magnitude faster than AAMD. |

| Deep Generative Models | Variational Autoencoders (VAEs), Diffusion Models [8] | Deep learning architectures that learn the equilibrium distribution of protein conformations from data, enabling rapid generation of diverse structural ensembles. |

| Structure Databases | RCSB Protein Data Bank (PDB) [6] | The primary repository for experimentally-determined 3D structures of proteins, used as starting points for simulations. |

| Analysis & Visualization | PyMOL, VMD, MDTraj | Specialized tools for visualizing 3D structures, analyzing simulation trajectories, and calculating key properties (e.g., RMSD, RMSF). |

Molecular Dynamics simulations provide an indispensable suite of tools for moving beyond static structural snapshots and capturing the essential dynamics of proteins. By applying the protocols outlined—from deriving dynamic pharmacophores from an all-atom MD ensemble to efficiently mapping folding landscapes with machine-learned coarse-grained models—researchers can deeply characterize the conformational landscape of drug targets. This dynamic understanding directly fuels rational pharmacophore development and the discovery of novel therapeutic agents, making MD a cornerstone of modern computational drug discovery.

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations have emerged as a transformative tool in structural biology, providing atomistic insight into the temporal evolution of biomolecular systems. In the context of drug discovery, this methodology bridges the critical gap between static structural snapshots and the dynamic reality of protein-ligand interactions. The extraction of pharmacophore models from MD trajectories represents a significant advancement over structure-based approaches that rely solely on static crystal structures, which may capture only a single, potentially non-representative conformation of the complex [11].

A pharmacophore is formally defined by the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) as "an ensemble of steric and electronic features that is necessary to ensure the optimal supramolecular interactions with a specific biological target structure and to trigger (or to block) its biological response" [6]. Traditional pharmacophore models derived from single crystal structures are inherently limited by the static nature of the source data, which fails to account for protein flexibility, ligand dynamics, and the ensemble of conformational states that exist in solution [11].

The integration of MD simulations addresses these limitations by sampling the conformational space of protein-ligand complexes, enabling the identification of persistent interaction patterns that might be absent in crystal structures due to crystal packing artifacts or the specific crystallization conditions [12] [11]. This approach allows researchers to move beyond a single structural snapshot toward a dynamic understanding of molecular recognition events, ultimately leading to more robust and biologically relevant pharmacophore models for virtual screening and drug design.

Theoretical Foundation

The Dynamic Nature of Protein-Ligand Interactions

Proteins and small molecules are inherently dynamic, exhibiting a wide spectrum of motions ranging from bond vibrations to large-scale collective movements. A crystal structure of a protein-ligand complex represents merely one snapshot of this dynamic system, providing no direct information about conformational flexibility or residue motions within the binding pocket [11]. Consequently, pharmacophore models derived from such static structures risk including features that are artifacts of the crystallization environment or missing transient but biologically relevant interactions.

Molecular dynamics simulations capture this complexity by generating trajectories that sample multiple conformational states of the protein-ligand complex. When applied to pharmacophore development, this dynamic perspective enables the differentiation between:

- Persistent interactions: Those maintained throughout significant portions of the simulation, likely representing critical binding determinants.

- Transient interactions: Those that appear only briefly, which may still contribute to binding affinity or specificity.

- Conformational adaptations: Induced-fit changes in either partner that occur upon binding.

For example, studies on KV10.1 potassium channels utilized MD-derived pharmacophores to reveal the disruption of a crucial π-π network of aromatic residues (F359, Y464, and F468) during inhibitor binding—a dynamic process that could not be observed in static structures [12]. Similarly, research on SARS-CoV-2 Mpro demonstrated substantial conformational changes in the S2 and S4 subsites during simulations with both covalent and non-covalent inhibitors [13].

MD-Derived Pharmacophore Generation Strategies

Several computational strategies have been developed to convert MD trajectories into pharmacophore models, each with distinct advantages:

Table 1: Pharmacophore Generation Methods from MD Trajectories

| Method | Description | Applications | Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Consensus Feature Analysis | Pharmacophore models generated for each trajectory snapshot, with features ranked by frequency | CDK2 inhibitors, general protein-ligand complexes [11] [14] | Identifies persistent interactions; provides feature probability data |

| Clustering-Based Approach | MD snapshots clustered by structural similarity, with representative structures used for pharmacophore generation | SARS-CoV-2 Mpro inhibitors [13] | Captures major conformational states; reduces redundancy |

| Dynamic Pharmacophore Maps | Multiple crystal structures or MD snapshots superimposed to create comprehensive interaction maps | KV10.1 channel inhibitors [12] | Incorporates multiple binding modes; covers diverse ligand scaffolds |

The underlying principle common to all these approaches is the conversion of dynamic interaction information into a spatially defined set of chemical features that represent the essential elements for molecular recognition. This process typically involves identifying hydrogen bond acceptors (HBA), hydrogen bond donors (HBD), hydrophobic regions (H), positive and negative ionizable groups (PI/NI), and aromatic rings (AR) that demonstrate spatial conservation throughout the simulation [6].

Experimental Protocols

The general workflow for extracting pharmacophores from MD simulations involves sequential steps from system preparation through to model validation, with iterative refinement based on validation results.

System Preparation and MD Simulation

Protein and Ligand Preparation

- Source Structures: Begin with high-quality crystal structures from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) or validated homology models. For KV10.1 channel studies, researchers created homology models using MODELLER based on the hERG channel template (PDB: 5VA1) [12].

- Structure Evaluation: Assess model quality using VERIFY3D, ERRAT, PROVE, and PROCHECK to identify geometric errors, phi-psi outliers, and deviations from standard atomic volumes [12].

- Protonation States: Assign appropriate protonation states to histidine residues and other ionizable groups at physiological pH (7.2±0.2). For SARS-CoV-2 Mpro, specific histidine residues were assigned as HID-41, HIE-163, HIE-164, and HIP-172 based on literature evidence [13].

- Ligand Parameterization: Develop force field parameters for ligands using tools such as the Ligand Preparation module in Schrödinger Suite with OPLS3 force field, generating possible tautomers and ionization states [13].

MD Simulation Setup

- Solvation and Ionization: Place the protein-ligand complex in an appropriate water box (e.g., TIP3P water model) and add ions to neutralize the system and achieve physiological concentration (typically 0.15 M NaCl). Membrane proteins require embedding in lipid bilayers using tools like CHARMM-GUI Membrane Builder [12].

- Energy Minimization: Perform stepwise energy minimization to remove steric clashes, typically starting with restraints on heavy atoms followed by full system minimization.

- Equilibration: Gradually heat the system to the target temperature (typically 300-310 K) while applying restraints to protein backbone atoms, followed by equilibrium runs without restraints.

- Production Run: Conduct unrestrained MD simulations for time scales sufficient to capture relevant motions. For pharmacophore modeling, simulation lengths typically range from 20 ns to several microseconds, depending on system size and complexity [11] [13].

Trajectory Analysis and Pharmacophore Generation

Trajectory Processing and Clustering

- Stability Assessment: Calculate root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) of protein backbone and ligand heavy atoms to verify simulation stability. Discard initial equilibration periods before analysis (typically 1-10% of total trajectory).

- Conformational Clustering: Employ algorithms such as k-means or hierarchical clustering on snapshots based on protein backbone RMSD or ligand binding mode to identify representative conformations. For SARS-CoV-2 Mpro, researchers used principal component analysis (PCA) combined with k-means clustering to identify distinct conformational states [13].

- Interaction Analysis: Use tools like LigandScout or in-house scripts to identify and characterize protein-ligand interactions (hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic contacts, ionic interactions) throughout the trajectory [12] [11].

Pharmacophore Model Generation

- Snapshot-Based Modeling: Generate individual pharmacophore models for each clustered snapshot or at regular intervals throughout the trajectory using software such as LigandScout, Discovery Studio, or Schrödinger's Phase [11] [15].

- Feature Frequency Analysis: Calculate the occurrence frequency of each pharmacophore feature across all models. Features present in >70-90% of snapshots are considered highly conserved, while those appearing in <5-10% may represent artifacts [11].

- Consensus Model Creation: Develop a final pharmacophore model incorporating the most persistent features. For CDK2 inhibitors, this approach yielded models with improved virtual screening performance compared to single-structure models [14].

Table 2: Key Software Tools for MD-Derived Pharmacophore Modeling

| Software | Capabilities | MD Integration | Special Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| LigandScout | Structure & ligand-based modeling, virtual screening | Direct trajectory analysis | Advanced visualization, residue bonding points for covalent inhibitors [12] [15] |

| Discovery Studio | CATALYST pharmacophore modeling, complex analysis | Snapshot processing | Integrated workflow with docking and MD tools [16] [15] |

| Schrödinger Phase | Ligand-based modeling, 3D-QSAR | Representative structure input | Shape-based alignment, activity prediction [15] |

| SeeSAR | Interactive analysis, HYDE scoring | Direct visualization | Fast screening, intuitive interface [17] |

| MOE | Structure-based design, molecular modeling | Trajectory input support | Comprehensive cheminformatics toolkit [15] |

Model Validation and Refinement

Validation Techniques

- Retrospective Screening: Test the model's ability to retrieve known active compounds from decoy databases, calculating enrichment factors and ROC curves. For SARS-CoV-2 Mpro models, AUC values of 0.93 and 0.73 were achieved for covalent and non-covalent inhibitors, respectively [13].

- Feature Importance Analysis: Systematically remove individual features and assess the impact on model performance to identify critical versus auxiliary features.

- Cross-Validation: Apply the model to structurally diverse ligands with known activity to evaluate generalization capability.

Refinement Strategies

- Feature Selection: Prioritize features based on frequency of occurrence, energetic contributions (from MM/PBSA calculations), and conservation across related targets.

- Spatial Tolerance Adjustment: Optimize the spatial tolerances of pharmacophore features based on their observed fluctuations during simulations.

- Exclusion Volumes: Add excluded volumes to represent steric constraints of the binding pocket, derived from the protein conformation observed during MD simulations.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Successful implementation of MD-derived pharmacophore modeling requires a suite of specialized software tools and computational resources.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| MD Simulation Engines | NAMD, GROMACS, AMBER, Desmond | Generate conformational ensembles | NAMD with CHARMM36 force field used for KV10.1 studies [12] |

| Trajectory Analysis | VMD, MDTraj, CPPTRAJ | Process and analyze MD trajectories | VMD used for trajectory conversion and visualization [14] |

| Pharmacophore Generation | LigandScout, Discovery Studio, Phase | Create and optimize pharmacophore models | LigandScout Expert used for KV10.1 pharmacophore modeling [12] |

| Virtual Screening | ZINCPharmer, Pharmit, SeeSAR | Identify potential ligands using pharmacophore models | Pharmit enables interactive screening of large compound databases [15] |

| Homology Modeling | MODELLER, SWISS-MODEL, AlphaFold2 | Generate protein structures when experimental data is limited | MODELLER used for KV10.1 homology models based on hERG template [12] [6] |

| Molecular Docking | Glide, AutoDock, FlexX | Predict ligand binding poses for initial structures | Glide used for initial docking before MD simulations [12] |

| 2-(2-Chloroethoxy)-2-methyl-propane | 2-(2-Chloroethoxy)-2-methyl-propane, CAS:17229-11-7, MF:C6H13ClO, MW:136.62 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| 2-Fluoro-5-methylpyridin-3-amine | 2-Fluoro-5-methylpyridin-3-amine, CAS:173435-33-1, MF:C6H7FN2, MW:126.13 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Case Studies and Applications

KV10.1 Potassium Channel Inhibitors

Researchers investigating KV10.1 potassium channels, a potential anticancer target, employed MD-derived pharmacophore modeling to understand inhibitor binding modes and address selectivity issues against the closely related hERG channel [12]. The protocol included:

- Construction of KV10.1 homology models based on the open-state hERG structure

- Molecular docking of known inhibitors

- MD simulations of protein-ligand complexes

- Generation of structure-based pharmacophore models from MD trajectories

The resulting pharmacophore model revealed essential features for KV10.1 inhibition, including hydrophobic groups and positively charged moieties that interact with aromatic residues (F359, Y464, F468) in the channel pore. Interestingly, the model showed high similarity to previously reported hERG pharmacophore models, explaining the challenge in developing selective KV10.1 inhibitors and suggesting alternative binding sites should be explored for selective drug design [12].

SARS-CoV-2 Main Protease (Mpro) Inhibitors

In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, researchers developed a comprehensive protocol to generate pharmacophore models for SARS-CoV-2 Mpro inhibitors, comparing covalent and non-covalent binding mechanisms [13]. The methodology incorporated:

- Flexible molecular docking to account for binding site flexibility

- Microsecond-scale MD simulations of inhibitor complexes

- MM/PBSA calculations to rank binding affinities

- PCA and k-means clustering to identify representative conformations

- Complex-based pharmacophore model generation for both inhibitor classes

The study revealed significant conformational changes in the S2 and S4 subsites during simulations and produced validated pharmacophore models with ROC-AUC values of 0.93 for covalent inhibitors and 0.73 for non-covalent inhibitors. These models incorporated a rare "residue bonding point" feature to represent the covalent interaction with Cys145, providing valuable tools for virtual screening campaigns against this important antiviral target [13].

Analysis and Interpretation

Evaluating Feature Stability and Relevance

A critical advantage of MD-derived pharmacophores is the ability to quantify feature stability throughout the simulation. Research on twelve diverse protein-ligand complexes demonstrated that features observed in crystal structures aren't always maintained during simulations—some persistent features in MD were absent from crystal structures, and vice versa [11].

The analytical workflow for feature assessment involves tracking feature persistence and correlating it with binding energetics:

Features can be categorized based on their persistence and energetic contributions:

- Essential Features: Present in >90% of snapshots with significant energetic contributions; must be included in the final model.

- Important Features: Present in 50-90% of snapshots with moderate energetic contributions; should be included in most cases.

- Contextual Features: Present in 10-50% of snapshots; include selectively based on specific design goals.

- Rare Features: Present in <10% of snapshots; typically excluded unless targeting specific conformational states.

Comparison of Methodological Approaches

Different research groups have developed varied approaches for extracting pharmacophores from MD data, each with strengths and limitations:

CHA (Count How many times a feature Appears) Method

- Generates individual pharmacophore models for each MD snapshot

- Creates feature vectors (bit strings) for each model

- Aggregates vectors to identify the most frequent feature combinations

- Particularly effective when only one protein-ligand complex is available [14]

MYSHAPE Method

- Aligns all MD snapshots to a reference structure

- Generates a single consensus model incorporating all observed features

- Assigns feature weights based on occurrence frequency

- Performs well when multiple complex structures are available [14]

Merged Pharmacophore Approach

- Creates individual pharmacophore models for each MD snapshot plus the experimental structure

- Merges all features into a comprehensive model

- Uses frequency information to prioritize features

- Provides the most complete representation of the dynamic interaction landscape [11]

The extraction of pharmacophore models from MD simulations represents a paradigm shift in structure-based drug design, moving from static structural snapshots to dynamic interaction landscapes. This approach acknowledges the inherent flexibility of biological systems and provides a more comprehensive representation of the molecular features essential for productive binding.

The methodologies described herein—from system preparation through trajectory analysis to model validation—provide researchers with a robust framework for implementing this powerful technique. As MD simulations become increasingly accessible through hardware advances and optimized algorithms, and as pharmacophore software continues to evolve, the integration of dynamics into feature-based molecular design promises to enhance the efficiency and success rates of drug discovery campaigns.

The case studies on KV10.1 channels and SARS-CoV-2 Mpro demonstrate the practical application of these methods to pharmaceutically relevant targets, illustrating how dynamic information can reveal binding mechanisms and inform the design of selective, potent inhibitors. As these methodologies continue to mature, they will undoubtedly play an increasingly central role in bridging the gap between structural biology and therapeutic development.

Identifying Cryptic Pockets and Allosteric Sites Through Dynamic Simulations

The efficacy of structure-based drug discovery has traditionally been anchored to the availability of high-resolution, static protein structures. However, these static snapshots often fail to capture the full spectrum of a protein's conformational landscape, potentially overlooking transient yet physiologically relevant states. Cryptic pockets—druggable sites that are absent in ground-state crystal structures but form transiently due to protein dynamics—and allosteric sites—regulatory binding pockets topographically distinct from the active site—represent promising frontiers for therapeutic intervention. These sites offer opportunities for developing highly selective drugs, particularly for targets with conserved active sites where conventional orthosteric drug design struggles to achieve specificity.

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations have emerged as a powerful computational technique to probe protein dynamics beyond the constraints of static structures. By simulating the physical movements of atoms and molecules over time, MD can model conformational changes, identify transient pockets, and elucidate allosteric communication pathways [18]. This dynamic perspective is particularly valuable for targeting G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) and protein kinases, where conformational flexibility plays a crucial functional role and where allosteric modulators can achieve exceptional subtype selectivity [19] [20] [21]. The integration of MD simulations into drug discovery pipelines represents a paradigm shift, enabling researchers to move beyond static structures and leverage protein dynamics for rational drug design.

Fundamental Concepts and Significance

Cryptic Pockets and Allosteric Sites: Definitions and Mechanisms

Cryptic pockets are binding sites that are not detectable in a protein's ground-state crystal structure but become accessible during conformational fluctuations [21]. These pockets can open and collapse spontaneously during molecular dynamics simulations, revealing druggable surfaces that are completely absent in experimental structures. The formation of cryptic pockets often involves the rotation of side chains and the movement of secondary structural elements, creating voids adjacent to known binding sites.

Allosteric sites are regulatory binding locations distinct from the orthosteric (active) site. Allosteric modulators binding to these sites can either enhance (positive allosteric modulators, PAMs) or inhibit (negative allosteric modulators, NAMs) protein function by inducing conformational changes that propagate through the protein structure [19]. Allosteric regulation provides several advantages for drug discovery, including greater selectivity for closely related protein subtypes and the potential for fine-tuned modulation of protein activity rather than complete inhibition.

The Role of Molecular Dynamics in Capturing Protein Dynamics

Molecular dynamics simulations provide atomic-level insights into the time-dependent behavior of biological systems. By numerically solving Newton's equations of motion for all atoms in the system, MD can capture protein flexibility, solvation effects, and the formation of transient states that are difficult to observe experimentally [18]. Advanced sampling techniques and microsecond-timescale simulations have made it possible to observe rare events such as cryptic pocket opening and allosteric transitions, providing mechanistic explanations for experimental observations and enabling structure-based drug design against dynamic targets [21].

Table 1: Key Concepts in Dynamic Simulation-Based Drug Discovery

| Concept | Definition | Significance in Drug Discovery | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cryptic Pockets | Transient binding sites absent in ground-state structures but formed during conformational fluctuations | Expands druggable space; enables targeting of previously "undruggable" proteins | Cryptic pocket in M1 muscarinic receptor [21] |

| Allosteric Sites | Binding sites topographically distinct from the orthosteric (active) site | Offers greater selectivity; allows fine-tuning of protein function | Allosteric site in GPCR extracellular vestibule [19] |

| Bond-to-Bond Propensity | Graph theory-based analysis predicting allosteric pathways and sites | Identifies key residues for allosteric signaling; enables computational prediction of allosteric sites [22] | Allosteric site prediction benchmarking datasets [22] |

Computational Methodologies and Workflows

Molecular Dynamics Simulation Protocols

A typical MD workflow for identifying cryptic pockets and allosteric sites involves several stages of system preparation and simulation. The protocol begins with system preparation, where the protein structure is protonated at physiological pH (7.4) using tools like the H++ server or similar methods [23]. Missing residues are modeled, and the system is solvated in an explicit water box (e.g., TIP3P water model) with a minimum extension of 10 Ã… from the protein surface. Counterions are added to maintain charge neutrality.

Energy minimization follows, typically using algorithms like L-BFGS with harmonic restraints on protein backbone atoms (force constant of ~10 kcal/mol/Ų), gradually reducing and removing restraints over thousands of steps [23]. The system is then gradually heated to the target temperature (e.g., 300 K) using a Langevin thermostat, followed by equilibration in both NVT (constant volume) and NPT (constant pressure) ensembles for nanoseconds to stabilize temperature and density.

Production simulations are conducted for timescales ranging from nanoseconds to microseconds, depending on the system and computational resources. For cryptic pocket detection, longer timescales (microseconds) are often necessary to observe rare conformational transitions [21]. Trajectories are saved at regular intervals (e.g., every 100 ps) for subsequent analysis. Multiple independent simulations are recommended to ensure adequate sampling and reproducibility [23].

Diagram 1: MD Simulation Workflow. This flowchart outlines the key stages in molecular dynamics simulations for cryptic pocket identification.

Binding Affinity Calculations and Analysis Methods

The Molecular Mechanics Poisson-Boltzmann Surface Area (MMPBSA) method is commonly used to calculate binding affinities from MD trajectories. The binding free energy (ΔGMMPBSA) is computed as the sum of molecular mechanics energy (ΔEMM) and solvation free energy (ΔGSol) [23]:

ΔGMMPBSA = ΔEMM + ΔGSol

Where ΔEMM includes electrostatic (ΔEele) and van der Waals (ΔEvdw) interactions, and ΔGSol includes polar (ΔGpol) and non-polar (ΔGnp) solvation contributions. A single-trajectory approach is often employed where receptor and ligand contributions are computed from the same trajectory [23].

For cryptic pocket detection, trajectory analysis focuses on identifying structural changes that create new druggable cavities. This includes monitoring side chain rotations, backbone movements, and changes in solvent-accessible surface area. In the case of the M1 muscarinic receptor, cryptic pocket formation involved rotation of Y2.64 away from ECL2 to form a hydrogen bond with E7.36, which in turn rotated inward and formed an additional hydrogen bond with Y2.61 [21]. These coupled motions opened a secondary binding pocket between TM2 and ECL2 that was absent in the crystal structure.

Bond-to-bond propensity analysis, a graph theory-based approach, can predict allosteric sites and communication pathways by analyzing the residue interaction network [22]. This method quantifies how perturbations propagate through the protein structure, identifying key residues involved in allosteric signaling.

Table 2: Comparison of Computational Methods for Site Identification

| Method | Principles | Applications | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Dynamics (MD) | Newtonian mechanics with empirical force fields | Cryptic pocket detection, allosteric mechanism elucidation | Atomistic detail, captures explicit solvent effects | Computationally expensive, limited by timescales |

| Bond-to-Bond Propensity | Graph theory analysis of residue interaction networks | Allosteric site prediction, signaling pathway identification | Fast, provides mechanistic insights | Based on static structure, may miss dynamics |

| MMPBSA | Molecular mechanics combined with continuum solvation | Binding affinity calculation from MD trajectories | More accurate than docking scores, uses ensemble data | Approximates solvation, neglects entropy |

| Docking | Rigid or flexible ligand docking to static structures | Initial virtual screening, pose prediction | Very fast, high throughput | Poor correlation with experimental affinities |

Practical Application: Case Study in GPCRs

Cryptic Pockets in Muscarinic Acetylcholine Receptors

A compelling example of cryptic pocket identification comes from studies of muscarinic acetylcholine receptors (mAChRs), particularly the M1 subtype. The highly selective positive allosteric modulator BQZ12 presented a conundrum: mutagenesis data suggested a binding mode that was sterically impossible in the available M1 mAChR crystal structures [21]. Mutation of residues W7.35 and Y45.51 ablated BQZ12 binding, suggesting these residues form stacking interactions with the ligand's aromatic core, while mutation of Y2.61 or Y2.64 significantly reduced binding affinity, indicating interaction with BQZ12's nonplanar arm.

Microsecond-timescale MD simulations of the M1 mAChR revealed that the allosteric site undergoes spontaneous conformational changes that dramatically alter its shape [21]. Specifically, Y2.64 rotated away from ECL2 to form a hydrogen bond with E7.36, which itself rotated inward toward the allosteric site and formed an additional hydrogen bond with Y2.61. These coordinated motions opened a cryptic pocket adjacent to the primary allosteric site between TM2 and ECL2. This cryptic pocket was observed to open and collapse spontaneously in simulations of both active and inactive receptor states, with and without orthosteric ligands bound.

Comparative simulations across mAChR subtypes (M1-M4) revealed that this cryptic pocket formed far more frequently in M1 than in other subtypes, explaining BQZ12's exceptional selectivity [21]. This dynamic mechanism reconciled previously contradictory mutagenesis data and provided a structural basis for rational design of M1-selective allosteric modulators.

Experimental Validation and Mutagenesis

The computational predictions were validated through mutagenesis experiments targeting residues involved in cryptic pocket formation [21]. Mutations designed to prevent the conformational changes necessary for pocket opening (e.g., by introducing steric hindrance or disrupting key hydrogen bonds) significantly reduced the binding affinity of M1-selective allosteric modulators like BQZ12, while having minimal effect on the binding of non-selective modulators. This experimental confirmation demonstrated the functional importance of the dynamically formed cryptic pocket and established MD simulations as a predictive tool for identifying allosteric mechanisms.

Diagram 2: Cryptic Pocket Discovery Cycle. This diagram illustrates the iterative process of identifying and validating cryptic pockets through simulation and experiment.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Reagent/Tool | Type | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| AMBER | Molecular dynamics software package | Force fields, simulation engine | MD simulations of protein-ligand complexes [23] |

| OpenMM | MD simulation toolkit | High-performance MD simulations | Large-scale binding affinity calculations [23] |

| PLAS-20k Dataset | Benchmark dataset | Training and validation for ML models | Developing binding affinity predictors [23] |

| General AMBER Force Field (GAFF2) | Force field | Parameters for small molecules | Ligand parameterization in MD simulations [23] |

| MMPBSA | Binding affinity method | Free energy calculation from trajectories | Computing protein-ligand affinities [23] |

| ProteinLens | Webserver | Bond-to-bond propensity analysis | Predicting allosteric sites and pathways [22] |

Integration with Machine Learning and Future Directions

The integration of molecular dynamics with machine learning represents a powerful synergy for advancing cryptic pocket and allosteric site discovery. Large-scale MD datasets like PLAS-20k—containing 97,500 independent simulations across 19,500 protein-ligand complexes—provide dynamic training data that goes beyond static structures [23]. These datasets enable the development of ML models that can predict binding affinities with better accuracy than docking scores and classify strong versus weak binders more effectively.

Machine learning approaches can leverage MD trajectories to identify patterns associated with cryptic pocket formation and allosteric signaling [22] [23]. Retrained models like OnionNet on PLAS-20k demonstrate the potential for ML to rapidly predict binding affinities while incorporating dynamic features of protein-ligand interactions. Future directions include the development of ML models that can directly predict cryptic pocket locations from sequence or static structure, potentially reducing the need for extensive MD simulations for initial screening.

Emerging methodologies also include hybrid docking-MD pipelines that combine the throughput of docking with the accuracy of MD refinement [20]. These workflows use docking for initial pose generation followed by short MD simulations and MMPSA calculations to refine poses and predict binding affinities. For challenging targets with high conformational flexibility, such as protein kinases and GPCRs, such integrated approaches show promise in improving virtual screening hit rates while maintaining computational feasibility.

The growing adoption of automated MD workflows and machine learning-driven interaction fingerprinting frameworks is transforming MD from a purely descriptive technique into a scalable, quantitative component of modern drug discovery [20]. As computational resources continue to expand and algorithms become more efficient, dynamic simulations will play an increasingly central role in identifying and validating cryptic allosteric sites for therapeutic targeting.

From Simulation to Screen: Practical Workflows for MD-Enhanced Pharmacophore Development and Virtual Screening

Molecular recognition is a dynamic process, and the interactions between a receptor and its ligand are inherently flexible. Traditional docking methods in structure-based drug design often treat the receptor as a rigid body, which overlooks the conformational changes crucial for binding. The Relaxed Complex Scheme (RCS) addresses this limitation by explicitly incorporating receptor flexibility through the use of structural ensembles derived from Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations [24]. This approach combines the thorough conformational sampling of MD with the computational efficiency of docking algorithms, enabling a more realistic representation of the binding process and improving the discovery of novel inhibitors [3].

The RCS is founded on the principle of conformational selection, where a ligand selects its optimal binding partner from a pre-existing ensemble of receptor conformations [25]. This method has proven valuable for identifying novel binding sites and ligands that would be missed by rigid docking into a single static structure [24] [25].

Theoretical Framework

The Need for Incorporating Receptor Flexibility

The early "lock-and-key" theory of ligand binding, which presumed a static receptor, has been superseded by models that account for protein motion [26]. Proteins exist in an equilibrium of interconverting conformational states, and ligands can selectively stabilize specific, sometimes rare, conformations [25] [26]. This understanding has profound implications for drug discovery, as any of these conformational states may present a unique, druggable binding site.

Static crystal structures offer a single snapshot of this dynamic landscape and may fail to reveal cryptic or allosteric pockets that are not occupied in the crystallized state [3]. Docking into a single structure therefore risks missing important binding opportunities. The RCS explicitly accounts for this dynamics by utilizing a diverse set of receptor snapshots from MD simulations, thereby capturing a broader range of potentially druggable conformations [24] [3].

The Relaxed Complex Scheme: A Hybrid Methodology

The RCS is a hybrid method that synergistically combines the strengths of MD simulations and molecular docking. Its primary advantage lies in its ability to account for the flexibility of both the receptor and the ligand in a computationally tractable manner [24]. While more rigorous methods like Free Energy Perturbation (FEP) provide highly accurate binding estimates, they are too computationally expensive for screening large compound libraries. The RCS serves as an efficient filter to reduce a large set of potential binders (∼10³ or more) to a manageable number of promising candidates (∼10¹), which can then be studied with more rigorous techniques [24]. The general workflow is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1. The Relaxed Complex Scheme (RCS) Workflow. The process begins with an experimental structure, undergoes MD simulation to generate a conformational ensemble, which is then clustered. A library of ligands is docked into each representative structure, and the results are analyzed to identify top candidates for further refinement [24] [25].

Computational Protocols

Molecular Dynamics Simulation for Ensemble Generation

The first and most critical step in the RCS is generating a representative ensemble of receptor conformations.

Detailed Protocol:

System Preparation:

- Initial Structure: Obtain a high-resolution experimental structure (X-ray or NMR) from the Protein Data Bank (PDB). Starting from a holo structure (with a bound ligand) can be beneficial, but apo structures (without ligand) are also used under the conformational selection model [24] [25].

- Parameterization: Use a molecular mechanics force field such as CHARMM [24], AMBER [9], or GROMOS [24]. For the ligand, generate parameters using tools like the General AMBER Force Field (GAFF) [27].

- Solvation and Ions: Solvate the protein-ligand system in a water box (e.g., TIP3P model) and add ions to neutralize the system's charge and mimic physiological ionic strength. Tools like CHARM-GUI can automate this process [27].

Simulation Run:

- Equilibration: Perform a multi-step equilibration protocol, starting with energy minimization followed by gradual heating to the target temperature (e.g., 303.15 K) and pressurization (e.g., 1 atm) over hundreds of picoseconds [27].

- Production MD: Run the production simulation for a duration sufficient to capture relevant motions. While modern simulations can reach micro- to milliseconds, useful ensembles have been generated from simulations as short as tens of nanoseconds [24] [25]. Using multiple replicates with different initial velocities is recommended for improved sampling [27].

- Software: Common MD software packages include NAMD [24], AMBER [9] [27], GROMACS [9], and CHARMM [9].

Trajectory Analysis and Clustering:

- Snapshot Extraction: Save snapshots of the trajectory at regular intervals (e.g., every 10-100 ps) [24].

- Clustering: To avoid docking into thousands of nearly identical structures, reduce the ensemble to a non-redundant set of conformations. Cluster snapshots based on the root mean-square deviation (RMSD) of the protein backbone or binding site residues. Common algorithms include hierarchical agglomerative clustering or k-means.

- Representative Selection: Select the central structure from each major cluster for the docking ensemble [24] [25].

Table 1: Example MD Simulation Parameters from a Case Study (Human Glucokinase)

| Parameter | Specification |

|---|---|

| Software | AMBER 16 [27] |

| Force Field | AMBER force field for protein; GAFF for ligand [27] |

| Simulation Box | Solvated with TIP3P water, ions added [27] |

| Temperature | 303.15 K [27] |

| Pressure | 1 atm (Monte Carlo barostat) [27] |

| Time Step | 2 fs (bonds involving H constrained with SHAKE) [27] |

| Replicates | 3 x 100 ns [27] |

| Total Sampling | 300 ns [27] |

Ensemble Docking and Analysis

The second phase involves docking a library of ligands into the curated ensemble of receptor structures.

Detailed Protocol:

Ligand and Receptor Preparation:

- Prepare the 3D structures of the small molecule ligands, generating reasonable protonation states at physiological pH.

- For each representative receptor snapshot, assign correct protonation states and partial charges compatible with the docking software.

Molecular Docking:

- Software: AutoDock is historically the most common docking program used in RCS studies, though others can be employed [24].

- Search Algorithm: Use a global search algorithm like the Genetic Algorithm (GA) implemented in AutoDock to thoroughly explore the ligand's translational, rotational, and conformational degrees of freedom [24].

- Scoring Function: The docking software scores and ranks poses based on an empirical scoring function that estimates the binding affinity [24].

Post-Docking Analysis:

- Binding Spectrum: For each ligand, a range of binding affinities is obtained across the receptor ensemble. This "binding spectrum" is used to identify ligands that bind favorably to multiple receptor conformations or exhibit particularly strong binding to specific states [24].

- Pose Analysis: Visually inspect the top-ranked poses to ensure meaningful interactions (e.g., hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic contacts) with the binding site.

- Consensus Ranking: Rank-order ligands based on their best predicted affinity or an average across the ensemble.

Table 2: Key Improvements in AutoDock for RCS Applications

| Improvement | Description | Benefit |

|---|---|---|

| Improved Desolvation | Accounts for a larger number of atom types [24] | More accurate estimation of desolvation penalties upon binding. |

| Charge Model | Uses fast calculation of charge distribution [24] | Ensures compatibility of partial charges between ligand and receptor. |

| Complete Thermodynamic Cycle | Computes unbound (gas phase) ligand enthalpy [24] | Provides a more physically realistic assessment of binding. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Software

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for the Relaxed Complex Scheme

| Category / Item | Function | Example Software / Force Fields |

|---|---|---|

| MD Simulation | Generates dynamic ensemble of receptor conformations. | NAMD [24], AMBER [9] [27], GROMACS [9], CHARMM [9] |

| Molecular Docking | Predicts binding pose and affinity of ligands to receptor snapshots. | AutoDock [24] |

| Force Fields | Defines energy functions for MD simulations. | CHARMM27 [24], AMBER [9], GROMOS [24] |

| System Preparation | Prepares and solvates the protein-ligand system for simulation. | CHARM-GUI [27], tLEaP (in AMBER) [27] |

| Analysis & Clustering | Analyzes trajectories and selects representative structures. | VMD, MDTraj, CPTRAJ (in AMBER) |

| Free Energy Calculations | (Optional) Refines binding affinity predictions for top hits. | MM-PBSA, LIE, FEP, TI [24] |

| Methyl 5-iodo-2,4-dimethoxybenzoate | Methyl 5-iodo-2,4-dimethoxybenzoate, CAS:3153-79-5, MF:C10H11IO4, MW:322.10 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 3-Iodo-4-methyl-7-nitro-1H-indazole | 3-Iodo-4-methyl-7-nitro-1H-indazole|CAS 1190315-75-3 | 3-Iodo-4-methyl-7-nitro-1H-indazole (CAS 1190315-75-3) is a versatile indazole building block for anticancer research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

Advanced Applications and Recent Developments

The core RCS methodology has been successfully applied to various drug targets, leading to the discovery of novel inhibitors. A seminal application was in the development of the first FDA-approved drug targeting HIV-1 integrase. RCS simulations revealed a novel binding trench and predicted that "butterfly compounds" could bind two subsites simultaneously, guiding the design of high-affinity inhibitors [25] [3].

The methodology continues to evolve with several key advancements:

- Integration with Machine Learning: Machine learning models are being trained to identify "selectable" receptor conformations from MD trajectories that are most likely to bind ligands well, optimizing the ensemble selection process [25].

- Analysis of Complex Binding Kinetics: Deep learning models are now used to analyze high-dimensional MD data. For instance, convolutional neural networks (CNNs) can process distance maps from MD trajectories to discriminate between functional states and predict the impact of mutations on binding, as demonstrated in studies of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein [28].

- Dynamic Pharmacophore Models: Instead of docking, pharmacophore models can be extracted from each MD snapshot. These models capture the dynamic interaction patterns between the receptor and a ligand. The Hierarchical Graph Representation of Pharmacophore Models (HGPM) provides an intuitive tool to visualize and prioritize these models for efficient virtual screening [27]. This workflow is depicted in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Workflow for Dynamic Pharmacophore Generation and HGPM. An alternative to direct docking involves generating structure-based pharmacophore models from each MD snapshot. These models are then integrated into a hierarchical graph for visualization and selection before being used in virtual screening [27].

Limitations and Future Directions

Despite its successes, the RCS has limitations. A significant challenge is the conformational sampling problem; even microsecond-long simulations may not fully capture slow, large-scale conformational changes relevant to binding [25] [26]. Furthermore, the accuracy of the method depends on the quality of the force field, and standard force fields have known approximations, such as the neglect of electronic polarization [26].

Future developments are poised to address these challenges:

- Enhanced Sampling: Methods like accelerated MD (aMD) artificially reduce energy barriers to accelerate conformational transitions, helping to reveal cryptic pockets and rare states [3] [26].

- Specialized Hardware: Specialized supercomputers like Anton and the use of Graphical Processing Units (GPUs) are pushing simulation timescales into the millisecond regime and beyond, allowing for more comprehensive sampling [25] [26].

- Ultra-Large Libraries: The growth of make-on-demand chemical spaces containing billions of compounds necessitates continued improvements in docking speed and scoring accuracy for RCS to remain effective in screening these vast libraries [3].

The Relaxed Complex Scheme represents a powerful and well-established methodology for incorporating full receptor flexibility into the structure-based drug discovery pipeline. By leveraging ensembles from molecular dynamics simulations, it provides a more physiologically realistic model of binding than static docking. While challenges in sampling and force field accuracy remain, ongoing advances in sampling algorithms, hardware, and integrative machine-learning approaches continue to expand the utility and predictive power of the RCS, solidifying its role as a key tool for modern computational drug discovery.

In the context of a broader thesis on molecular dynamics in drug discovery, this document details the application of dynamic pharmacophore models, which are ensembles of steric and electronic features necessary for optimal supramolecular interactions with a specific biological target, built from molecular dynamics (MD) simulation snapshots [29]. Unlike static models derived from single crystal structures, dynamic pharmacophores account for protein flexibility, a critical factor in molecular recognition processes such as induced fit and conformational selection [30]. This protocol provides a detailed methodology for generating, analyzing, and applying these models to enhance the efficiency and success rate of structure-based drug discovery campaigns, particularly for challenging targets where flexibility plays a decisive role in ligand binding.

Molecular dynamics simulations capture the time-dependent evolution of a protein's structure, providing an atomic-resolution view of its conformational landscape. By extracting snapshots from an MD trajectory, one can observe the transient formation and disappearance of binding pockets, as well as fluctuations in the chemical features presented to potential ligands [30]. Building a pharmacophore from this ensemble involves identifying conserved interaction patterns that persist throughout the simulation, which represent essential anchoring points for ligand binding.

The general workflow for building dynamic pharmacophore models consists of four major phases: (1) System Preparation and MD Simulation, where the protein system is equilibrated and simulated to generate a representative conformational ensemble; (2) Trajectory Analysis and Feature Identification, which involves analyzing the MD snapshots to map potential interaction points; (3) Model Generation and Validation, where the pharmacophore hypothesis is constructed and tested for its ability to distinguish known active compounds from decoys; and (4) Application in Virtual Screening, utilizing the validated model to identify novel potential binders from chemical databases.

The following workflow diagram illustrates this process and the logical relationships between each stage:

Experimental Protocols

System Preparation and MD Simulation

Objective: To generate a structurally diverse and biologically relevant ensemble of protein conformations for subsequent pharmacophore analysis.

Methodology:

Initial Structure Preparation:

- Obtain the protein structure from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) or from homology modeling. Critical residues, particularly those in the binding site, should be modeled if missing using tools like MODELLER [31].

- Process the structure by adding hydrogen atoms, assigning protonation states at physiological pH (e.g., using MOE or Maestro's Protein Preparation Wizard), and optimizing hydrogen bonding networks.

Solvation and Ionization:

- Place the protein in an orthorhombic water box (e.g., TIP3P model) with a minimum distance of 10-12 Ã… between the protein and box edge.

- Add ions (e.g., Naâº, Clâ») to neutralize the system's net charge and to achieve a physiologically relevant salt concentration (e.g., 0.15 M).

Energy Minimization and Equilibration:

- Perform energy minimization using steepest descent and conjugate gradient algorithms (~5000 steps each) to relieve steric clashes.

- Equilibrate the system in two phases: (1) NVT ensemble for 100 ps to stabilize temperature at 300 K using a thermostat (e.g., Berendsen or Nosé-Hoover), and (2) NPT ensemble for 100 ps to stabilize pressure at 1 bar using a barostat (e.g., Parrinello-Rahman).

Production MD Simulation:

- Run an unrestrained production MD simulation for a duration sufficient to capture relevant motions of the binding site. For most drug targets, a simulation of 100 ns to 1 µs is appropriate [30]. Use a timestep of 2 fs.

- Save atomic coordinates to a trajectory file every 10-100 ps. This frequency balances spatial resolution with storage requirements.

Validation: Monitor simulation stability by analyzing root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) of protein backbone atoms. The simulation can be considered equilibrated when the RMSD plateaus.

Feature Identification from MD Snapshots

Objective: To analyze the MD trajectory and identify conserved pharmacophoric features within the binding site.

Methodology:

Trajectory Clustering and Snapshot Selection:

- To avoid over-representing similar conformations, cluster the MD trajectory based on the root-mean-square fluctuation (RMSF) of binding site residues. Use algorithms such as linkage, k-means, or Daura et al.

- Select representative snapshots from the largest clusters for detailed analysis. For instance, from a 100 µs simulation of TMPRSS2, 20 snapshots were selected to form the receptor ensemble [30].

Binding Site Analysis and Feature Mapping:

- For each selected snapshot, use software like LigandScout [32] or MOE to analyze the binding site geometry and chemical environment.

- Manually or automatically map key chemical features presented by the protein residues that could interact with a ligand. The core features to identify include:

- Hydrogen Bond Acceptors (HBA): Located near residues with hydrogen bond donor groups (e.g., backbone NH, side chain OH/NH).

- Hydrogen Bond Donors (HBD): Located near residues with hydrogen bond acceptor groups (e.g., backbone C=O, side chain COOâ»).

- Hydrophobic Features (H): Associated with aliphatic or aromatic side chains (e.g., Val, Leu, Ile, Phe, Trp, Tyr).

- Positive/Ionizable (PI): Near acidic residues (e.g., Asp, Glu).

- Negative/Ionizable (NI): Near basic residues (e.g., Lys, Arg, His).

- Aromatic Rings (AR): Defined by the centroids of phenyl, tyrosine, or tryptophan rings.

Feature Consolidation: