Improving Statistical Accuracy in Diffusion Coefficient Calculation: A Guide for Biomedical Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on improving the statistical rigor and reliability of diffusion coefficient calculations.

Improving Statistical Accuracy in Diffusion Coefficient Calculation: A Guide for Biomedical Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on improving the statistical rigor and reliability of diffusion coefficient calculations. Covering foundational principles to advanced applications, it explores key computational methods like Mean Squared Displacement (MSD) and Velocity Autocorrelation Function (VACF), details common pitfalls and uncertainty quantification, and compares analysis protocols. The content also examines the critical role of validation against experimental data and presents emerging trends, including machine learning and automated workflows, to enhance reproducibility in biomedical and clinical research.

Understanding Diffusion Coefficients: Core Concepts and Statistical Foundations

Fundamental Definitions and Core Concepts

What is a Diffusion Coefficient? The diffusion coefficient (D) is a fundamental physical parameter that quantifies the rate of material transport through a medium. Formally, it is defined as the amount of a particular substance that diffuses across a unit area in 1 second under the influence of a concentration gradient of one unit [1]. Its standard units are length²/time, typically expressed as cm²/s or m²/s [1]. This coefficient characterizes how quickly particles—whether atoms, molecules, or ions—move from regions of high concentration to regions of low concentration through random molecular motion known as Brownian motion [2].

Fick's Laws of Diffusion The mathematical foundation for understanding diffusion was established by Adolf Fick in 1855 through his now-famous laws [3]:

Fick's First Law states that the diffusive flux (J)—the amount of substance flowing through a unit area per unit time—is proportional to the negative concentration gradient. In simple terms, particles move from regions of high concentration to low concentration at a rate directly related to how steep the concentration difference is [3]. The mathematical expression for one-dimensional diffusion is: ( J = -D \frac{d\varphi}{dx} ) where J is the diffusion flux, D is the diffusion coefficient, and dφ/dx is the concentration gradient [3].

Fick's Second Law predicts how the concentration gradient changes with time due to diffusion. It is derived from the first law combined with the principle of mass conservation [3]. In one dimension, it states: ( \frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial t} = D \frac{\partial^2 \varphi}{\partial x^2} ) where ∂φ/∂t represents the rate of concentration change over time [3].

Table 1: Key Variables in Fick's Laws of Diffusion

| Variable | Description | Typical Units |

|---|---|---|

| J | Diffusive flux | mol/m²·s or kg/m²·s |

| D | Diffusion coefficient | m²/s |

| φ | Concentration | mol/m³ or kg/m³ |

| x | Position coordinate | m |

| t | Time | s |

| ∇ | Gradient operator (multi-dimensional) | mâ»Â¹ |

Critical Factors Affecting Diffusion Coefficients

Temperature, Viscosity, and Molecular Size The diffusion coefficient depends significantly on environmental conditions and molecular characteristics, as described by the Einstein equation [1]: ( D = \frac{k_B T}{6 \pi \eta r} ) where k₠is Boltzmann's constant, T is absolute temperature, η is the medium viscosity, and r is the radius of the diffusing particle [1]. This relationship reveals that diffusion increases with temperature but decreases with higher viscosity and larger molecular size.

Biological Tissue Considerations In biological systems, water diffusion is "hindered" or "restricted" due to the presence of cellular membranes, macromolecules, and increased viscosity [2]. Intracellular water diffuses more slowly than extracellular water because it has more opportunities to collide with cell walls, organelles, and macromolecules [2]. Many tissues also exhibit diffusion anisotropy, where water molecules diffuse more readily along certain directions, such as along nerve or muscle fiber bundles, than others [2].

Diffusion in Clinical Imaging In diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI), the Apparent Diffusion Coefficient (ADC) is the functional parameter calculated from mean diffusivity along three orthogonal directions [4]. The ADC value reflects tissue cellularity, microstructure, fluid viscosity, membrane permeability, and blood flow [4]. These values serve as crucial biomarkers in clinical practice, particularly for distinguishing malignant from benign tumors and assessing treatment response [4] [5].

Table 2: Typical Diffusion Coefficient Values Across Different Media

| Medium/Context | Diffusion Coefficient Value | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Pure water (37°C) | 3.0 × 10â»Â³ mm²/s | Reference value [2] |

| Biological tissues | 1.0 × 10â»Â³ mm²/s (average) | 10-50% of pure water value [2] |

| Ions in dilute aqueous solutions | (0.6–2)×10â»â¹ m²/s | Room temperature [3] |

| Biological molecules | 10â»Â¹â° to 10â»Â¹Â¹ m²/s | Varies by molecular size [3] |

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

FAQ: Why are my measured diffusion coefficients inconsistent between different experimental methods?

Different measurement methods (e.g., steady-state flux, lag time, sorption/desorption) may yield varying results due to several factors [1]:

- Boundary layer effects: In membrane permeation studies, stagnant aqueous layers at membrane-solution interfaces can significantly influence results if not properly accounted for [1]. The thickness of these stagnant layers decreases as the agitation rate increases.

- System heterogeneity: If the membrane contains impermeable or adsorptive domains, the measured value represents an apparent diffusion coefficient that must be corrected for tortuosity and porosity [1].

- Adsorption effects: When materials contain domains that bind the diffusing substance, adsorption can significantly affect lag time measurements, requiring mathematical correction [1].

FAQ: How can I improve the accuracy and reproducibility of ADC measurements in clinical MRI?

Standardization and validation are critical for reliable ADC measurements [4]:

- Validate MRI equipment performance using commercial phantoms like the Quantitative Imaging Biomarker Alliance (QIBA) diffusion phantom to assess accuracy and repeatability [4].

- Maintain consistent sequence parameters across longitudinal studies, as DWI is susceptible to variations in MRI scanner-specific features [4].

- Implement clinical protocol validation by confirming that institution-specific clinical brain protocols fulfill QIBA claims regarding accuracy and repeatability before patient application [4].

- Consider acquisition parameters optimization, as recent research shows that fast DWI protocols with reduced number of excitations (NEX) can provide comparable visibility and ADC values while significantly shortening acquisition time [5].

FAQ: What are common sources of error when determining diffusion coefficients from membrane permeation studies?

- Insufficient steady-state duration: Flux data should be collected for longer than 2.7× the lag time to ensure proper steady-state conditions [1].

- Inadequate mixing conditions: Poor hydrodynamics at interfaces can create boundary layers that control the overall diffusion process rather than the membrane itself [1].

- Neglecting leakage: Ensure the experimental apparatus has proper airtightness, as leakage can significantly compromise results [6].

- Temperature instability: Diffusion coefficients are temperature-dependent, so maintaining constant temperature is essential for reproducible measurements [1] [6].

Experimental Protocols and Standardized Methodologies

Protocol 1: Membrane Diffusion Coefficient Using Steady-State Flux Method

This methodology determines the diffusion coefficient through homogeneous polymer membranes [1]:

- Apparatus Setup: Mount the membrane between donor and receiver chambers with known membrane thickness (h) and surface area.

- Solution Preparation: Fill donor and receiver chambers with solutions maintaining a constant concentration difference (ΔC).

- Temperature Control: Conduct the experiment at constant temperature with sufficient stirring to minimize boundary layer effects.

- Flux Measurement: After reaching steady state (typically >2.7× lag time), measure the steady-state flux (Jss) by tracking concentration changes in the receiver chamber over time.

- Partition Coefficient Determination: Independently measure the partition coefficient (k) of the solute between the membrane and solution phases.

- Calculation: Apply the formula to determine the membrane diffusion coefficient: ( Dm = \frac{J{ss} h}{k \Delta C} )

Protocol 2: Clinical DWI Protocol Validation for ADC Quantification

This protocol validates MRI equipment and clinical acquisition protocols for reliable ADC measurements [4]:

- Phantom Preparation: Use a commercially available QIBA diffusion phantom and ensure temperature stability according to manufacturer specifications.

- Scanner Validation: Acquire DWI using the QIBA phantom protocol across all MRI scanners with parameters including multiple b-values (0, 500, 1000, 1500, 2000 s/mm²) and three orthogonal diffusion encoding directions [4].

- Performance Metrics Assessment: Evaluate accuracy (ADC bias), linear correlation to reference values, and short-term repeatability using within-subject coefficient of variation (wCV) [4].

- Clinical Protocol Validation: Repeat measurements using institution-specific clinical brain protocols to verify they fulfill QIBA accuracy and repeatability claims [4].

- Patient Image Quality Assurance: Apply validated protocols to patient scanning and review DWI for image quality and ADC measurement repeatability [4].

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Diffusion Experiments

| Item | Function/Purpose | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| QIBA Diffusion Phantom | Validates accuracy and repeatability of ADC measurements | MRI equipment performance assessment [4] |

| Homogeneous Polymer Membranes | Provides defined matrix for diffusion coefficient determination | Membrane permeation studies [1] |

| Stagnant Diffusion Layer Controls | Assesses and minimizes boundary layer effects | Steady-state flux method optimization [1] |

| Temperature Control System | Maintains constant temperature for reproducible measurements | All diffusion coefficient determination methods [1] [6] |

| Anti-Radon Membranes | Specialized barrier materials with known diffusion properties | Validation of novel measurement devices [6] |

| Calibrated Reference Materials | Provides known diffusion coefficients for method validation | Quality control across experimental setups |

Advanced Measurement Techniques and Numerical Recovery

Novel Experimental Approaches Recent methodological advances include:

- TESTMAT Device: A small PVC device that measures radon diffusion coefficients using weak radon sources, preventing radiation protection oversight [6]. This approach employs a specific software (ENDORSE) that models radon activity concentrations and diffusion through materials using the explicit finite difference method [6].

- Fast DWI Protocols: Research demonstrates that breast DWI protocols with reduced number of excitations (NEX=1) can provide comparable visibility and ADC values to conventional protocols (NEX=4) while reducing acquisition time from 1 minute 52 seconds to just 40 seconds [5].

Numerical Recovery of Diffusion Coefficients For inverse problems of recovering space-dependent diffusion coefficients from terminal measurements, advanced numerical procedures have been developed [7]:

Mathematical Formulation: The inverse problem involves recovering an unknown diffusion coefficient q from noisy terminal observation data of the form: ( z^\delta(x) = u(q^\dag)(x,T) + \xi(x) ) where u(q†)(T) represents the solution of the diffusion equation with exact potential q†, and ξ represents measurement noise [7].

Regularization Approach: Employ output least-squares formulation with H¹(Ω)-seminorm penalty to address ill-posedness, discretized using Galerkin finite element method with continuous piecewise linear finite elements in space and backward Euler convolution quadrature in time [7].

Error Analysis: Recent research provides rigorous error bounds for discrete approximations that explicitly depend on noise level, regularization parameter, and discretization parameters, offering practical guidelines for parameter selection [7].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the fundamental relationship between Mean Squared Displacement (MSD) and the diffusion coefficient?

The Mean Squared Displacement (MSD) quantifies the average square distance particles move from their starting positions over time and is directly related to the diffusion coefficient (D) through the Einstein-Smoluchowski relation [8] [9]. For normal diffusion in d dimensions, the relationship is given by:

[ \lim_{t \to \infty} \frac{d}{dt} \text{MSD}(t) = 2dD ]

This means that for a random walk (Brownian motion) in an isotropic medium, the MSD grows linearly with time, and the slope of the MSD plot is equal to (2dD) [10] [9]. Consequently, the diffusion coefficient can be calculated as ( D = \frac{\text{MSD}(t)}{2d \ t} ) for a sufficiently long time t [11].

FAQ 2: How do I extract a reliable diffusion coefficient from an MSD plot in practice?

To obtain a reliable diffusion coefficient, you must fit a straight line to the MSD curve within its linear regime [10] [11]. The slope of this line is then used in the Einstein relation. The critical steps are:

- Identify the Linear Segment: The MSD of a purely diffusive particle is linear across most time lags. However, at very short time lags, ballistic motion may cause a curved MSD, and at very long time lags, poor statistics due to fewer averaging points can lead to noise [10] [12]. A log-log plot of MSD vs. time lag can help identify the linear (diffusive) regime, which will have a slope of 1 [10].

- Use the Optimal Number of Points: The number of MSD points used for the linear fit significantly impacts the estimate's accuracy [13] [14]. Using too few points wastes data, while using too many includes noisy, poorly-averaged data. The optimal number of fitting points depends on the reduced localization error, ( x = \sigma^2 / D \Delta t ), where ( \sigma ) is the localization uncertainty and ( \Delta t ) is the time between frames [13]. When x is small, the first two MSD points may suffice; when x is large, more points are needed [13].

FAQ 3: My MSD curve is not linear. What does this mean for particle motion?

Deviations from a straight line in an MSD plot provide crucial insights into the nature of the particle's motion [15] [12]:

- Directed Motion: If the MSD curve increases with an upward curve (super-linear), it suggests that active, directed motion is superposed on diffusion [12].

- Constrained Motion: If the MSD curve plateaus, it indicates that the particle's motion is confined to a limited space, such as within a cellular organelle. The square root of the plateau value provides an estimate of the size of the confining region [12].

- Subdiffusion: If the MSD curve increases but with a downward curve (sub-linear), it is termed subdiffusion. This is common in crowded environments like the cell cytoplasm [15].

FAQ 4: What are the primary sources of error when calculating D from MSD analysis?

The main sources of error are:

- Localization Uncertainty (σ): The error in determining the precise position of a particle in each frame. This error dominates the MSD value at short time lags and causes the y-intercept of the MSD plot to be non-zero [13] [12].

- Finite Camera Exposure (tâ‚‘): During the camera's exposure time, a moving particle emits photons from different positions, effectively blurring its image. This dynamic blurring increases the apparent localization uncertainty, especially for fast-diffusing particles [13].

- Statistical Sampling Error: For a single particle trajectory, the MSD at the longest time lags is calculated from only a few displacement pairs, leading to high statistical uncertainty [13] [14].

FAQ 5: When should I use the Stokes-Einstein-Sutherland equation?

The Stokes-Einstein-Sutherland equation, ( D = \frac{k_B T}{6 \pi \eta r} ), is a specific form of the Einstein relation that applies to the diffusion of spherical particles in a continuous fluid with low Reynolds number [16]. It is widely used to estimate the diffusion coefficient of nanoparticles or large molecules in solution, given the temperature (T) and the viscosity of the solvent (η) [16].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: High variability in calculated D values between different trajectories.

| Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| Insufficient trajectory length. | Record longer trajectories. For an accuracy of ~10%, trajectories with about 1000 data points are often required [14]. |

| The system has multiple diffusion states. | The molecule may be switching between different environments (e.g., bound and unbound states). MSD analysis will only yield an average D. Use methods designed to detect heterogeneity, such as moment scaling spectrum or hidden Markov model analysis [13]. |

| Non-optimal number of MSD points used for fitting. | Determine the optimal number of points (p_min) to use in the linear fit based on your experimental parameters (localization error, diffusion coefficient, trajectory length) [13]. |

Problem: MSD plot has a large positive intercept.

| Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| Significant static localization error. | This is the most common cause. The intercept is approximately ( 2d\sigma^2 ), where σ is the localization uncertainty [13] [12]. Improve your imaging conditions (e.g., higher signal-to-noise ratio) to reduce σ. When fitting the MSD, do not force the fit through the origin. |

| Dynamic blur due to finite camera exposure. | Account for this in your MSD model. The theoretical MSD in the presence of diffusion and localization error is ( \text{MSD}(t) = 2d D t + 2d\sigma^2 ). If dynamic blur is significant, a more complex model may be needed [13]. |

Problem: MSD plot is noisy, especially at long time lags.

| Potential Cause | Solution | |

|---|---|---|

| Poor statistical averaging at long lag times. | This is inherent to MSD calculation. The MSD for a lag time corresponding to n frames is averaged over N-n points, where N is the total trajectory length. The noise therefore increases with lag time [8] [13]. | Use the optimal fitting range that excludes the very noisy long-lag-time MSD points [13]. |

| Trajectory is too short. | Increase the length of the tracked trajectories to get better averaging for all time lags [14]. |

Quantitative Data and Experimental Protocols

Key Quantitative Relationships for MSD Analysis

| Relationship | Formula | Parameters | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Einstein-Smoluchowski (General) | ( D = \frac{1}{2d} \lim_{t \to \infty} \frac{d}{dt} \text{MSD}(t) ) | d: dimensions; t: time | [10] [9] |

| MSD for Normal Diffusion | ( \text{MSD}(t) = 2d D t ) | D: diffusion coefficient | [8] [9] |

| MSD with Localization Error | ( \text{MSD}(t) = 2d D t + 2d\sigma^2 ) | σ: localization uncertainty | [13] [12] |

| Stokes-Einstein-Sutherland | ( D = \frac{k_B T}{6 \pi \eta r} ) | k_B: Boltzmann constant; T: temperature; η: viscosity; r: hydrodynamic radius | [16] |

| Reduced Localization Error | ( x = \frac{\sigma^2}{D \Delta t} ) | Δt: time between frames | [13] |

Error Analysis in Diffusion Coefficient Estimation

| Factor | Impact on Calculated D | How to Mitigate |

|---|---|---|

| Localization Error (σ) | Biases short-time MSD, leading to overestimation of D if ignored. | Use the MSD model that includes the offset. Improve imaging SNR [13] [12]. |

| Trajectory Length (N) | Shorter trajectories lead to larger statistical errors in D. | Use trajectories with ~1000 points for ~10% accuracy [14]. |

| Fitting Range (Number of MSD points, p) | Non-optimal p can lead to significant bias and variance. | Use the optimal number of MSD points, p_min, which depends on x and N [13]. |

Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Fluorescent Probes | Tag molecules of interest (e.g., proteins, lipids) to allow their visualization under a microscope [13]. |

| Sample Chamber | A stable and clean environment for holding the sample (e.g., live cells, polymer solution) during imaging. |

| High-Sensitivity Camera | Detects the faint light emitted by single fluorescent probes. Essential for achieving low localization uncertainty [13]. |

| Immersion Oil | Matches the refractive index between the microscope objective and the coverslip to maximize resolution and signal collection. |

| Analysis Software | Used for particle localization (finding the precise position in each frame) and subsequent trajectory and MSD analysis [10]. |

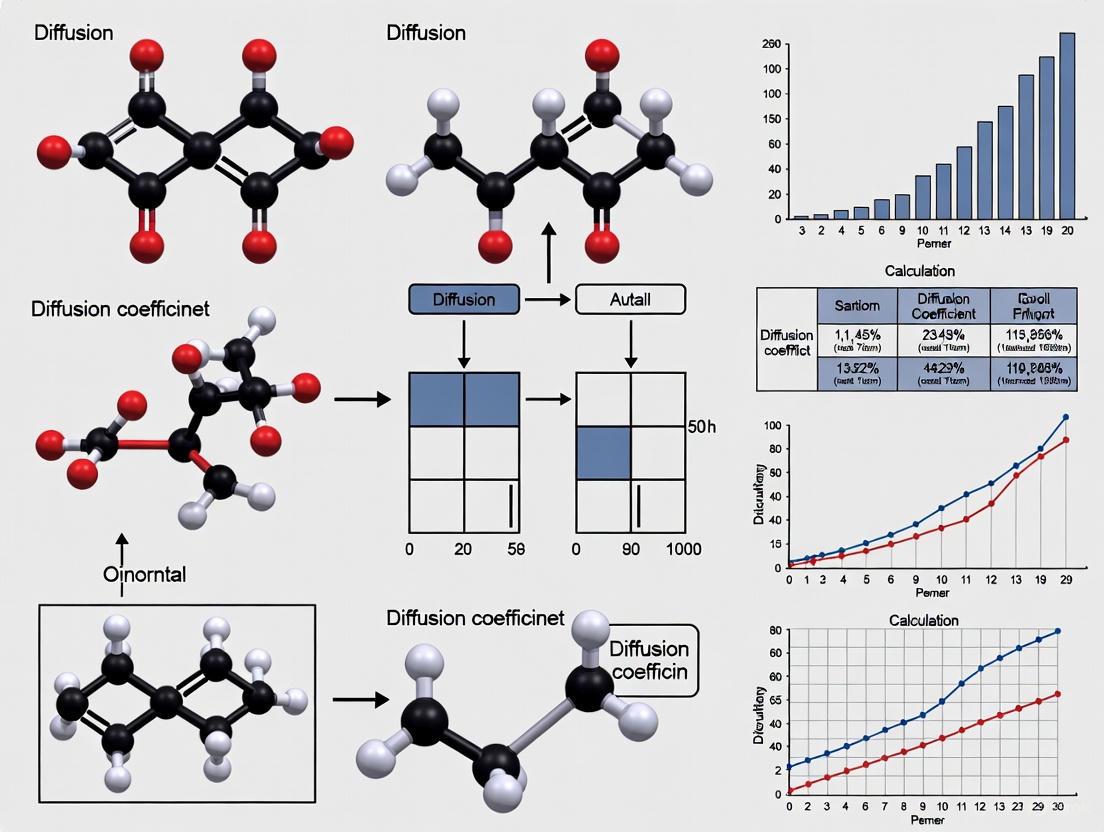

Experimental Workflow and Data Analysis

The following diagram illustrates the complete workflow for obtaining a diffusion coefficient from single-particle tracking, from data acquisition to final analysis.

Workflow for Diffusion Coefficient Calculation from MSD

Frequently Asked Questions

What are the primary sources of statistical variance in molecular dynamics simulations?

Statistical variance in MD simulations primarily arises from limited sampling of diffusion events due to short simulation timescales, force field approximations, and finite system sizes. In ab initio MD, simulations are typically limited to a few hundred atoms and sub-nanosecond timescales, capturing only a limited number of diffusion events. This results in significant statistical variance in calculated diffusional properties. The accuracy of forces calculated using molecular mechanics force fields also contributes to variance, as these are fit to quantum mechanical calculations and experimental data but remain inherently approximate [17] [18].

How does experimental measurement contribute to statistical variance in diffusion studies?

Experimental techniques like Total Internal Reflection Microscopy (TIRM) introduce variance through technically unavoidable noise effects and inappropriate parameter choices. Detector shot noise from statistical uncertainty in photo counting and background noise from uncorrelated light scattering can limit reliability, particularly in regions of interaction potentials with large gradients. Prolonged sampling times and improperly sized probe particles also contribute to erroneous results, especially where forces of pico-Newton magnitude or larger act on particles [19].

What methods can reduce statistical variance in diffusion coefficient calculations?

The T-MSD method combines time-averaged mean square displacement analysis with block jackknife resampling to address the impact of rare, anomalous diffusion events and provide robust statistical error estimates from a single simulation. This approach eliminates the need for multiple independent simulations while ensuring accurate diffusion coefficient calculations. Proper procedures for extracting diffusivity from atomic trajectory, including adequate averaging over time intervals and ensuring sufficient simulation duration to capture diffusion events, are also critical [20] [18].

How do integration approaches mitigate statistical variance?

Integrative modeling combining experimental data with physics-based simulations reveals both stable structures and transient intermediates. The maximum entropy principle helps build dynamic ensembles from diverse data while addressing uncertainty and bias. This is particularly valuable for interpreting low-resolution experimental data and resolving heterogeneity in biomolecular systems [21].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: High Variance in Calculated Diffusion Coefficients from MD Simulations

Problem Identification:

- Unusually large fluctuations in mean squared displacement (MSD) values

- Poor linear fit to the Einstein relation for diffusivity calculation

- Significant differences in results between independent simulation runs

Diagnosis Checklist:

- Determine if simulation duration captures sufficient diffusion events (≥20 ion hops recommended)

- Verify system size contains adequate atoms for statistics (>100 mobile ions ideal)

- Check time step settings for numerical stability (typically 1-2 femtoseconds)

- Confirm force field appropriateness for your specific molecular system

Resolution Steps:

- Extend Simulation Duration: Run simulations until MSD reaches at least 10Ų for reasonable statistics [18]

- Implement Advanced Analysis: Apply T-MSD method with block jackknife resampling for robust error estimates [20]

- Increase System Size: Use larger simulation boxes with more mobile ions when computationally feasible

- Validate with Experimental Data: Compare trends with experimental measurements where available [22]

Prevention Strategies:

- Perform preliminary calculations to estimate required simulation time

- Use multiple independent trajectories with different initial conditions

- Implement proper equilibration protocols before production runs

Issue: Experimental- Computational Discrepancies in Diffusion Measurements

Problem Identification:

- Systematic differences between experimental diffusion coefficients and simulation results

- Inconsistent temperature or concentration dependence between methods

- Poor reproducibility across different experimental techniques

Diagnosis Checklist:

- Identify potential force field limitations for specific molecular interactions

- Evaluate experimental conditions not replicated in simulations (e.g., impurities, boundaries)

- Assess timescale disparities between methods

- Examine signal-to-noise ratios in experimental measurements

Resolution Steps:

- Integrate Approaches: Combine experimental data with simulations using maximum entropy methods [21]

- Address Noise Sources: For TIRM, optimize particle size and sampling times to minimize shot noise effects [19]

- Standardize Conditions: Ensure simulated and experimental conditions (T, P, composition) match precisely [22]

- Validate with Multiple Techniques: Compare results across complementary methods

Issue: Poor Statistical Confidence in Ab Initio MD Diffusion Results

Problem Identification:

- Limited ion hops observed during simulation timeframe

- High sensitivity of results to simulation parameters

- Large error bars in Arrhenius plots for activation energy

Resolution Steps:

- Quantify Statistical Variance: Use methods that correlate variance with number of observed diffusion events [18]

- Focus on Accessible Range: Limit studies to materials with reasonably fast diffusion (D > 10â»â¸ cm²/s)

- Employ Enhanced Sampling: Implement techniques to accelerate rare events when appropriate

- Leverage Machine Learning: Integrate ML approaches to identify key MD properties influencing accuracy [23]

Table 1: Major Sources of Statistical Variance in Diffusion Studies

| Variance Source | Impact Level | Affected Methods | Mitigation Approaches |

|---|---|---|---|

| Limited sampling of diffusion events | High | AIMD, Classical MD | Extended simulation duration, Multiple trajectories [18] |

| Force field inaccuracies | Medium-High | Classical MD | Force field validation, QM/MM hybrid methods [17] |

| Experimental noise | Medium | TIRM, Scattering techniques | Optimized sampling parameters, Noise reduction algorithms [19] |

| Finite size effects | Medium | MD simulations | Larger system sizes, Finite size corrections [18] |

| Timescale disparities | High | All comparative studies | Integrated approaches, Enhanced sampling [21] |

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Diffusion Studies

| Reagent/Software | Function/Purpose | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|

| GROMACS | MD simulation software | Biomolecular systems, Drug solubility [23] |

| LAMMPS | MD simulation package | Materials science, Interface studies [22] |

| T-MSD analysis | Diffusion coefficient calculation | Ionic conductors, Accurate conductivity estimation [20] |

| Maximum entropy methods | Integrative modeling | Combining experimental data with simulations [21] |

| CHARMM27 force field | Molecular mechanics parameters | Biomolecular simulations [22] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Diffusion Coefficient Calculation from AIMD Simulations

Materials:

- Atomic trajectories from AIMD simulations

- Processing software (Python, MATLAB, or specialized analysis tools)

Methodology:

- Trajectory Preparation: Ensure proper equilibration before analysis

- Mean Squared Calculation: Compute MSD using equation: MSD(Δt) = (1/N) × Σ⟨|ri(t + Δt) - ri(t)|²⟩ where N is number of mobile ions, r_i positions, Δt time interval [18]

- Diffusivity Extraction: Fit linear region of MSD vs time to Einstein relation: D = MSD(Δt) / (2d × Δt) where d is dimensionality [18]

- Statistical Analysis: Apply block averaging or jackknife methods for error estimation [20]

- Validation: Check for sufficient MSD values (>10Ų) and linear fit quality

Quality Control:

- Verify simulation duration captures adequate diffusion events

- Confirm system size appropriate for statistics

- Validate with known standards when available

Protocol 2: Integrated Experimental-Computational Diffusion Analysis

Materials:

- Experimental diffusion data (TIRM, NMR, scattering)

- MD simulation capabilities

- Integration software/platform

Methodology:

- Data Acquisition: Collect experimental data under controlled conditions [19]

- Parallel Simulation: Run MD simulations matching experimental conditions [22]

- Maximum Entropy Integration: Combine datasets using maximum entropy principle [21]

- Variance Analysis: Quantify uncertainties from both sources

- Iterative Refinement: Use discrepancies to improve force fields or experimental design

Integrated Variance Reduction Workflow

Advanced Variance Reduction Techniques

For researchers working within the thesis context of improving statistics in diffusion coefficient calculation, these advanced approaches are recommended:

Machine Learning Enhancement: Implement ML algorithms like Gradient Boosting to identify key MD properties influencing solubility and diffusion predictions. Studies show this can achieve predictive R² values of 0.87 with proper feature selection [23].

Hybrid Simulation Protocols: Combine AIMD for accuracy with classical MD for improved statistics through longer timescales. Use AIMD to validate key interactions, then extend sampling with force-field MD.

Dynamic Experimental Design: Optimize TIRM parameters based on real-time variance assessment:

- Adjust sampling times to balance spatial resolution and noise

- Select probe particles of appropriate size (typically 1-5μm)

- Implement noise threshold monitoring during data collection [19]

The integration of these approaches within a systematic framework provides the most promising path toward significantly reducing statistical variance in diffusion coefficient research.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the primary computational methods for calculating diffusion coefficients at the atomic level? The two most common methods are Mean Squared Displacement (MSD) and Velocity Autocorrelation Function (VACF), typically applied to data from Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations [24].

- Mean Squared Displacement (MSD): This method tracks the average particle displacement over time. In the diffusive regime, where MSD increases linearly with time, the diffusion coefficient (D) is calculated as the slope of the MSD plot divided by 6 (for a 3D system):

D = slope(MSD)/6[25] [24]. - Velocity Autocorrelation Function (VACF): This method uses the integral of the velocity autocorrelation. The formula is

D = (1/3) ∫⟨v(0)⋅v(t)⟩dt[24].

FAQ 2: Why does my calculated diffusion coefficient not converge, and what are the different diffusion regimes? A lack of convergence often occurs because the simulation has not run long enough to reach the true diffusive regime. The MSD plot typically shows multiple regimes [24]:

- Ballistic regime: At very short times, particles move with near-constant velocity, and MSD is proportional to

t². - Subdiffusive regime: At intermediate times, particles may experience trapping or crowding, and MSD is proportional to

t^αwhereα < 1. - Diffusive regime: At long times, particle motion becomes random, and MSD is proportional to

t. The diffusion coefficient should only be calculated from the linear slope in this final regime [24]. Running longer simulations is necessary to capture this.

FAQ 3: How do temperature and density influence the diffusion coefficient? The relationship is well-described by physical principles and can be captured in analytical expressions.

- Temperature: A higher temperature (

T) increases the thermal energy of particles, enhancing their mobility and leading to a higher diffusion coefficient. The relationship often follows an Arrhenius-type behavior:D(T) = Dâ‚€ exp(-Eâ‚ / k_B T), whereEâ‚is the activation energy for diffusion [26] [25]. - Density (

Ï): A higher density typically means less free space for particles to move, resulting in more collisions and a lower diffusion coefficient. Symbolic regression analysis of MD data has found that the diffusion coefficient is often inversely proportional to density, leading to forms likeD ∠T / Ïfor some molecular fluids [27].

FAQ 4: My simulation system is small. How does this affect my calculated diffusion coefficient?

Finite-size effects are a critical consideration in MD simulations. Using periodic boundary conditions in a small box can artificially suppress the measured diffusion coefficient (D_PBC) due to hydrodynamic interactions with periodic images. A widely used correction is the Yeh and Hummer formula [24]:

D_corrected = D_PBC + 2.84 k_B T / (6 π η L)

where k_B is Boltzmann's constant, T is temperature, η is the shear viscosity of the solvent, and L is the dimension of the cubic simulation box. For accurate results, it is best to use large system sizes or apply this correction [24].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Inconsistent Diffusion Coefficients from Repeated Experiments/Simulations

- Possible Cause 1: Insufficient sampling or trajectory length.

- Solution: Ensure your MD simulation runs long enough for the MSD to become linear. Use multiple independent trajectories (or time origins within a long trajectory) and average the results to improve statistics [24].

- Possible Cause 2: Incorrect identification of the diffusive regime.

- Solution: Plot the MSD on a log-log scale to clearly identify the ballistic, sub-diffusive, and linear diffusive regimes. Only perform the linear fit on the MSD in the linear (diffusive) regime [24].

Problem: Discrepancy Between Computed and Experimental Diffusion Coefficients

- Possible Cause 1: The force field or interatomic potential used in the simulation does not accurately represent the real physical interactions.

- Solution: Validate your computational model against known experimental data for a simple system before applying it to complex ones. Consider using more advanced or validated force fields [27].

- Possible Cause 2: Neglecting finite-size effects or other systematic errors in the calculation method.

- Solution: Apply the Yeh and Hummer correction for finite-size effects. Compare results from both MSD and VACF methods to check for consistency [24].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol 1: Calculating Diffusion Coefficient via Mean Squared Displacement (MSD) in MD

This is a standard protocol for analyzing Molecular Dynamics trajectories [25] [24].

- Run Production MD: Perform a sufficiently long molecular dynamics simulation (NVT or NPT ensemble) after proper equilibration.

- Export Trajectory: Ensure the trajectory is saved with a high enough frequency (e.g., every 1-10 ps) to capture particle motion.

- Calculate MSD: For a set of particles (e.g., all Lithium ions in a cathode material [25]), compute the MSD as a function of time. The general formula is

MSD(t) = ⟨ [r(t') - r(t' + t)]² ⟩, where the average⟨⟩is over all particles and multiple time originst'[24]. - Check for Linear Regime: Plot MSD versus time. Identify the time interval where the MSD plot is a straight line.

- Perform Linear Fit: In the identified linear regime, perform a linear regression

MSD(t) = A + 6Dt. - Extract D: The diffusion coefficient

Dis the slope of the fit line divided by 6 (for a 3D isotropic system):D = slope / 6[25] [24].

Protocol 2: Extrapolating Diffusion Coefficients using the Arrhenius Equation

This protocol allows for the estimation of diffusion coefficients at lower temperatures where direct MD simulation would be prohibitively long [25].

- Run MD at Multiple Temperatures: Perform MD simulations and calculate the diffusion coefficient

Dusing Protocol 1 for at least four different elevated temperatures (e.g., 600 K, 800 K, 1200 K, 1600 K) [25]. - Create an Arrhenius Plot: Plot the natural logarithm of the diffusion coefficient (

ln(D)) against the inverse temperature (1/T). - Linear Fit: Fit the data points to the Arrhenius equation:

ln D(T) = ln Dâ‚€ - (Eâ‚ / k_B) * (1/T). - Extract Parameters: The y-intercept of the linear fit gives the pre-exponential factor

Dâ‚€, and the slope gives the activation energyEâ‚viaslope = -Eâ‚ / k_B[25]. - Extrapolate: Use the obtained

Dâ‚€andEâ‚to calculateDat your desired lower temperatureTusing the Arrhenius equation.

Quantitative Data from Research

Table 1: Experimentally Determined Diffusion Parameters for Various Systems

| System | Diffusion Mechanism | Pre-exponential Factor (Dâ‚€) | Activation Energy (Eâ‚) | Temperature Range | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ag in PbTe | Interstitial | 1.08 × 10â»âµ cm²·sâ»Â¹ | 52.9 kJ·molâ»Â¹ | Mid (600-800 K) | [28] |

| H in W (BCC) | TIS-TIS pathway | 3.2 × 10â»â¶ m²/s | 1.48 eV | High (1400-2700 K) | [26] |

Table 2: Symbolic Regression Models for Self-Diffusion in Bulk Molecular Fluids

Analysis of MD data for nine molecular fluids via symbolic regression found a consistent physical relationship for the reduced self-diffusion coefficient D* [27].

| Model Form | Key Variables | Physical Interpretation | Application |

|---|---|---|---|

D* = α₠T*^α₂ / (Ï*^α₃ - α₄) |

T*: Reduced TemperatureÏ*: Reduced Density |

D* is proportional to T* and inversely proportional to Ï*. |

Universal form for bulk molecular fluids (e.g., ethane, n-hexane) [27]. |

Workflow and Relationship Visualizations

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Diffusion Coefficient Research

| Tool / Material | Function / Application | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Dynamics (MD) Software (e.g., LAMMPS, GROMACS, AMS) | Simulates the time evolution of the atomic-scale system to generate particle trajectories for analysis [26] [25] [24]. | The choice of software depends on the system, force field compatibility, and computational resources. |

| Interatomic Potentials (e.g., EAM, ReaxFF, Lennard-Jones) | Describes the forces between atoms in an MD simulation. Critical for accurate physical modeling [26] [25] [27]. | The potential must be carefully selected and validated for the specific material and conditions being studied. |

| Analysis Tools (e.g., in-house scripts, GROMACS 'msd') | Post-processes MD trajectories to compute properties like MSD and VACF, from which D is derived [25] [24]. | Ensure the tool correctly handles averaging over particles and time origins for statistical accuracy. |

| Symbolic Regression Framework | A machine learning technique used to derive simple, physically interpretable analytical expressions for D from simulation data [27]. | Useful for creating predictive models that bypass traditional numerical analysis, linking D directly to T and Ï [27]. |

| WWL113 | WWL113, MF:C29H26N2O4, MW:466.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| FXIIIa-IN-1 | FXIIIa-IN-1, CAS:55909-92-7, MF:C26H25N5O19S6, MW:903.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

This guide details the calculation of diffusion coefficients using Mean Squared Displacement (MSD) and Velocity Autocorrelation Function (VACF) for researchers in computational materials science and drug development. These methods are foundational for understanding atomic and molecular transport properties, which is critical for applications ranging from battery material design to pharmaceutical development.

Core Concepts: MSD and VACF

Mean Squared Displacement (MSD)

The Mean Squared Displacement (MSD) quantifies the average deviation of a particle's position from its reference position over time, serving as the most common measure of the spatial extent of random motion [8]. In the context of diffusion, it measures the portion of the system "explored" by a random walker. The MSD is defined for a time ( t ) as:

[ \text{MSD} \equiv \left\langle |\mathbf{x}(t) - \mathbf{x}0|^2 \right\rangle = \frac{1}{N} \sum{i=1}^N |\mathbf{x}^{(i)}(t) - \mathbf{x}^{(i)}(0)|^2 ]

where ( \mathbf{x}^{(i)}(0) = \mathbf{x}_0^{(i)} ) is the reference position of particle ( i ), and ( \mathbf{x}^{(i)}(t) ) is its position at time ( t ) [8].

Velocity Autocorrelation Function (VACF)

The Velocity Autocorrelation Function (VACF) measures how a particle's velocity correlates with itself over time, providing insights into the dynamics and interactions within the system [25] [29]. The VACF is defined as:

[ \text{VACF}(t) = \langle \mathbf{v}(t') \cdot \mathbf{v}(t'') \rangle ]

In practice, the VACF is calculated and integrated to obtain the diffusion coefficient [25].

Relationship Between MSD and VACF

The MSD and VACF are mathematically related through a double integral [30] [31]:

[ \langle x^2(t) \rangle = \int0^t \int0^t dt' dt'' \langle v(t') v(t'') \rangle = 2 \int0^t \int0^{t'} dt' dt'' \langle v(t') v(t'') \rangle ]

This relationship shows that the MSD is comprised of the integrated history of the VACF [30]. For normal diffusion, molecular motion only becomes a random walk (leading to linear MSD) after the VACF has decayed to zero, meaning the particles have "forgotten" their initial velocity [30].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. Why is my MSD curve not a straight line? A non-linear MSD indicates that the simulation may not have reached the diffusive regime. This occurs when the simulation time is too short for particles to forget their initial velocities [30]. Ensure your production run is sufficiently long and always validate that the MSD plot becomes linear before calculating the diffusion coefficient [25].

2. How do I choose between the MSD and VACF method? The MSD method is generally recommended for its straightforward implementation and interpretation [25]. The VACF method can be more sensitive to statistical noise and requires velocities to be written to the trajectory file at a high frequency [25]. For most practical applications, especially for researchers new to diffusion calculations, the MSD method is preferable.

3. My diffusion coefficient value seems too high/low. What could be wrong? Finite-size effects are a common cause of inaccurate diffusivity values. The diffusion coefficient depends on supercell size unless the cell is very large [25]. A best practice is to perform simulations for progressively larger supercells and extrapolate to the "infinite supercell" limit [25].

4. How can I estimate the diffusion coefficient at room temperature when my simulations are at high temperatures? Calculating diffusion coefficients at low temperatures like 300K requires impractically long simulation times. Instead, use the Arrhenius equation to extrapolate from higher temperatures [25]:

[ \ln D(T) = \ln D0 - \frac{Ea}{k_B} \cdot \frac{1}{T} ]

Calculate ( D(T) ) for at least four different elevated temperatures (e.g., 600K, 800K, 1200K, 1600K) to determine the activation energy ( Ea ) and pre-exponential factor ( D0 ), then extrapolate to lower temperatures [25].

5. What are the key parameters to ensure in my MD simulation for reliable diffusion coefficients? Critical parameters include: sufficient equilibration time, appropriate production run length to achieve linear MSD, proper system size to minimize finite-size effects, and correct sampling frequency [25]. For MSD, sample frequency can be set higher, while VACF requires more frequent sampling of velocities [25].

Troubleshooting Guides

MSD Analysis Issues

| Problem | Possible Causes | Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Non-linear MSD | Simulation too short; insufficient statistics [25] | Extend production run; ensure MSD slope is constant [25] |

| Noisy MSD data | Inadequate sampling or small system size [32] | Increase number of atoms; use block averaging [32] |

| Incorrect D value | Finite-size effects; poor linear fit region selection [25] | Use larger supercells; carefully choose fit region [25] |

VACF Analysis Issues

| Problem | Possible Causes | Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| VACF integral not converging | Trajectory too short; infrequent velocity sampling [25] | Run longer simulation; decrease sample frequency [25] |

| Oscillatory VACF | Strong binding or caging effects [33] | Verify system is in diffusive regime; check for artifacts |

General Workflow Problems

| Problem | Possible Causes | Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Poor statistics | Inadequate sampling of phase space [32] | Use block averaging for error estimates; longer simulations [32] |

| Unphysical D values | System not properly equilibrated [25] | Extend equilibration phase; verify energy stabilization |

Quantitative Data Reference

Diffusion Coefficient Calculation Formulas

| Method | Formula | Key Parameters |

|---|---|---|

| MSD (Einstein relation) | ( D = \frac{1}{2d} \frac{d}{dt} \langle | \mathbf{r}i(t+t0) - \mathbf{r}i(t0) |^2 \rangle{t0} ) where ( d=3 ) for 3D systems [25] [32] | Slope of MSD in linear regime; dimension ( d ) |

| VACF (Green-Kubo) | ( D = \frac{1}{3} \int0^{t{max}} \langle \mathbf{v}(0) \cdot \mathbf{v}(t) \rangle dt ) [25] | Integration limit ( t_{max} ); velocity correlation |

Typical MD Parameters for Diffusion Calculations

| Parameter | Recommended Value | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Production steps | 100,000+ [25] | Depends on system and temperature |

| Equilibration steps | 10,000+ [25] | Ensure energy stabilization |

| Sample frequency | 5-100 steps [25] | Lower for VACF, higher for MSD |

| Temperature control | Berendsen thermostat [25] | Damping constant ~100 fs [25] |

Experimental Protocols

Standard MSD Protocol for Diffusion Coefficient Calculation

System Preparation: Begin with an equilibrated structure. For amorphous systems, this may require simulated annealing (heating to 1600K followed by rapid cooling) and geometry optimization with lattice relaxation [25].

Equilibration MD: Run an equilibration simulation (e.g., 10,000 steps) at the target temperature using an appropriate thermostat (damping constant = 100 fs) [25].

Production MD: Execute a sufficiently long production simulation (e.g., 100,000 steps) with trajectory sampling. For MSD, sampling every 10-100 steps is typically sufficient [25].

Trajectory Analysis: Parse the trajectory file and compute the MSD for the species of interest (e.g., Li atoms in battery materials) [25] [32].

Linear Fitting: Identify the linear regime of the MSD plot. The diffusion coefficient is calculated as ( D = \text{slope}(MSD)/6 ) for 3D systems [25].

Validation: Ensure the MSD curve is straight and the calculated diffusion coefficient curve becomes horizontal, indicating convergence [25].

VACF Protocol for Diffusion Coefficient Calculation

High-Frequency Sampling: Configure the MD simulation to write velocities to the trajectory file at a high frequency (small sample frequency number) as this is critical for VACF [25].

Production Run: Perform the production MD simulation with frequent velocity sampling.

VACF Computation: Calculate the velocity autocorrelation function ( \langle \mathbf{v}(0) \cdot \mathbf{v}(t) \rangle ) for the atoms of interest [29].

Integration: Integrate the VACF over time and divide by 3 to obtain the diffusion coefficient: ( D = \frac{1}{3} \int0^{t{max}} \langle \mathbf{v}(0) \cdot \mathbf{v}(t) \rangle dt ) [25].

Convergence Check: Verify that the plot of the integrated VACF becomes horizontal for large times, indicating convergence [25].

Research Reagent Solutions

Computational Tools for Diffusion Calculations

| Tool/Software | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| SLUSCHI-Diffusion [32] | Automated workflow for AIMD and diffusion analysis | First-principles diffusion in solids and liquids |

| Transport Analysis (MDAKit) [29] | Python package for VACF and self-diffusivity | Biomolecular simulations |

| AMS with ReaxFF [25] | Molecular dynamics engine with MSD/VACF analysis | Battery materials (e.g., Li-ion diffusion) |

| VASPKIT [32] | VASP output processing for MSD and transport | First-principles MD analysis |

Advanced Methodologies

Error Estimation and Validation

Implement block averaging for robust error estimates in calculated diffusion coefficients [32]. This involves dividing the trajectory into multiple blocks, computing D for each block, and calculating the standard deviation across blocks. Reproduce literature results for standard systems (e.g., SPC/E water model) to validate your implementation [29].

Multi-Temperature Analysis for Activation Energy

For comprehensive diffusion studies, calculate diffusion coefficients at multiple temperatures and create an Arrhenius plot (ln D vs. 1/T) to determine the activation energy Ea [25]. This approach provides more fundamental insights into the diffusion mechanism and allows for extrapolation to temperatures not directly accessible through simulation.

Calculation Methods in Practice: From MD Simulations to Clinical MRI

Calculating accurate diffusion coefficients from molecular dynamics (MD) simulations is a cornerstone of research in materials science, chemical engineering, and drug development. However, these calculations are inherently plagued by statistical uncertainty due to the finite nature of simulations. The core challenge lies in extracting a precise, reliable value for the diffusion coefficient (D) from noisy trajectory data. This guide provides specific, actionable protocols to overcome these statistical hurdles, improve the efficiency of your calculations, and accurately quantify the associated uncertainty, thereby enhancing the robustness of your research findings.

Core Concepts & The Scientist's Toolkit

What is a Diffusion Coefficient?

The self-diffusion coefficient, D*, quantifies the mean squared displacement (MSD) of a particle over time due to its inherent random motion in the absence of a chemical potential gradient. It is defined by the Einstein relation [34] [35]:

$$ \text{MSD}(t) = \langle |r(t) - r(0)|^2 \rangle = 2nDt $$

where MSD(t) is the mean squared displacement at time t, n is the dimensionality (typically 3 for MD simulations), and D is the diffusion coefficient [25].

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Computational Tools

The following table details key software and analytical tools used in the featured methodologies for calculating diffusion coefficients.

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Diffusion Coefficient Calculation

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function in Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| AMS/ReaxFF [25] | Software Suite | Performs molecular dynamics simulations with specific force fields (e.g., for battery materials) and includes built-in MSD & VACF analysis. |

| LAMMPS [36] | Software Suite | A widely used molecular dynamics simulator for performing production MD runs on various systems. |

| MDAnalysis [37] | Python Library | A tool for analyzing MD trajectories, including modules for dimension reduction and diffusion map analysis. |

| kinisi [34] | Python Package | Implements Bayesian regression for optimal estimation of D* from MSD data, providing accurate uncertainty quantification. |

| Spl-334 | Spl-334, CAS:688347-51-5, MF:C22H15N3O3S2, MW:433.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| w-Conotoxin M VIIA | w-Conotoxin M VIIA, MF:C102H172N36O32S7, MW:2639.2 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Methodologies: Protocols for Calculation

Two primary methods are used to calculate diffusion coefficients from MD trajectories, both derived from the statistics of particle displacements.

Method 1: Mean Squared Displacement (MSD) Analysis

This is the most common and recommended approach [25].

Step-by-Step Protocol:

- Run Production MD: Execute a sufficiently long MD simulation after proper equilibration. Ensure you save the trajectory at a consistent frequency (e.g., every 1-5 steps) [25].

- Calculate MSD: For the species of interest (e.g., Li ions), compute the MSD as a function of time. This is typically an average over all equivalent particles and multiple time origins within the trajectory [34]: $$ \text{MSD}(t) = \frac{1}{N(t)} \sum{i=1}^{N(t)} |ri(t) - r_i(0)|^2 $$

- Fit to Linear Model: Fit the MSD curve to the equation

MSD(t) = 6D*t + cover a suitable time interval where the MSD is linear. The diffusion coefficient is then given byD = slope / 6[25].

Visualization of the MSD Analysis Workflow:

Method 2: Velocity Autocorrelation Function (VACF)

This method provides an alternative route via the Green-Kubo relation [35].

Step-by-Step Protocol:

- Run Production MD with Velocities: As with MSD, run a simulation but ensure that atomic velocities are saved at a high frequency in the trajectory [25].

- Calculate VACF: Compute the velocity autocorrelation function for the atoms: $$ \text{VACF}(t) = \langle vi(t) \cdot vi(0) \rangle $$

- Integrate VACF: The diffusion coefficient is obtained by integrating the VACF over time: $$ D = \frac{1}{3} \int{0}^{t{max}} \text{VACF}(t) dt $$ [25]

Advanced Statistical Method:

For highest statistical efficiency and accurate uncertainty estimation from a single simulation, use Bayesian regression as implemented in the kinisi package [34]. This method accounts for the heteroscedastic and correlated nature of MSD data, overcoming the limitations of ordinary least-squares fitting.

Table 2: Comparison of Diffusion Coefficient Calculation Methods

| Method | Key Formula | Key Advantages | Key Disadvantages | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MSD (Einstein) | D = slope(MSD) / 6 [25] |

Intuitive, widely used, generally robust. | Requires a long, linear MSD region; standard OLS fit underestimates uncertainty [34]. | |

| VACF (Green-Kubo) | D = ⅓ ∫ VACF(t) dt [25] |

Can provide insights into dynamical processes. | Requires high-frequency velocity saving; integration to infinity is impractical [25]. | |

| Bayesian MSD Fitting | `p(D* | x)` [34] | Near-optimal statistical efficiency; accurate uncertainty from one trajectory. | More complex implementation than OLS. |

Troubleshooting & FAQs

Q1: My MSD curve is not a straight line. What should I do?

- Cause A: Insufficient sampling. The simulation may not be long enough to capture the true diffusive regime.

- Solution: Run a longer simulation. The MSD line should be straight; if not, you need more statistics [25].

- Cause B: System not equilibrated. The initial structure may still be relaxing.

- Solution: Ensure your system is fully equilibrated before the production run. Protocols like simulated annealing can help create stable amorphous structures [25].

Q2: How can I get a reliable diffusion coefficient for a solute in solution?

- Challenge: A single solute molecule in a large solvent box requires an impractically long simulation for good statistics [35].

- Solution: Use an efficient sampling strategy. Run multiple, independent short simulations and average the MSDs collected from them, rather than one extremely long simulation [35].

Q3: My calculated diffusion coefficient seems too high/low. What could be wrong?

- Cause A: Finite-size effects. The simulated box size is too small, affecting the hydrodynamics.

- Solution: Perform simulations for progressively larger supercells and extrapolate the diffusion coefficients to the "infinite supercell" limit [25].

- Cause B: Inaccurate force field.

- Solution: Validate your force field (e.g., GAFF) by comparing predicted D for a known system with experimental data before applying it to new systems [35].

Q4: How do I know the uncertainty in my estimated diffusion coefficient?

- Problem: Ordinary least-squares (OLS) regression significantly underestimates the true uncertainty because MSD data points are serially correlated and heteroscedastic [34].

- Solution: Use advanced fitting methods like Generalized Least-Squares (GLS) or Bayesian regression, which account for the full correlation structure of the MSD data to provide an accurate uncertainty estimate [34].

Q5: How can I estimate diffusion coefficients at low temperatures (e.g., 300 K)?

- Challenge: At low temperatures, diffusion is slow, requiring prohibitively long simulation times to observe significant displacement [25].

- Solution: Use the Arrhenius equation. Calculate D at several elevated temperatures (e.g., 600 K, 800 K, 1200 K), then plot

ln(D)against1/T. The slope gives-E_a/k_B, allowing you to extrapolate D to lower temperatures [25].

Visualization of the Temperature Extrapolation Workflow:

FAQs: Core Concepts and Calculations

Q1: What is the fundamental equation for calculating MSD?

The Mean Squared Displacement is fundamentally calculated using the Einstein relation, which states that for a particle with position ( \mathbf{r} ) at time ( t ), the MSD for a time lag ( \tau ) is given by [38] [39]: [ MSD(\tau) = \langle [ \mathbf{r}(t + \tau) - \mathbf{r}(t) ]^2 \rangle ] where the angle brackets ( \langle \rangle ) denote an average over all time origins ( t ) and over all particles ( N ) in the ensemble [39]. For a single particle trajectory, the average is taken over all possible time origins within the trajectory.

Q2: How is the self-diffusion coefficient (D) derived from the MSD plot?

The self-diffusivity ( D ) is directly related to the slope of the MSD curve in the linear regime. For a ( d )-dimensional MSD, it is calculated as [39]: [ D = \frac{1}{2d} \lim{t \to \infty} \frac{d}{dt} MSD(r{d}) ] In practice, this involves identifying a linear segment of the MSD versus lag-time plot and performing a linear fit. The slope of this fit is then used to compute ( D ). For a 3D system (d=3), the pre-factor becomes ( \frac{1}{6} ) [39].

Q3: My MSD curve is not linear. What does this indicate about the particle motion?

A non-linear MSD on a log-log plot indicates anomalous or non-Brownian motion [40] [41]. A linear segment with a slope of 1 on a log-log plot confirms normal diffusion. A slope less than 1 suggests sub-diffusive motion (e.g., particles in a crowded environment or a gel), while a slope greater than 1 indicates super-diffusive or directed motion (e.g., active transport in cells) [40]. Visual inspection of the MSD plot, ideally on a log-log scale, is crucial for identifying the appropriate linear segment for diffusion coefficient calculation [39].

Q4: What are the best practices for ensuring my trajectory data is suitable for MSD analysis?

The most critical requirement is to use unwrapped coordinates [39]. When atoms cross periodic boundaries, they must not be wrapped back into the primary simulation cell, as this would artificially truncate displacements and underestimate the MSD. Various simulation packages provide utilities for this conversion (e.g., in GROMACS, use gmx trjconv -pbc nojump) [39]. Furthermore, maintain a relatively small elapsed time between saved trajectory frames to capture the dynamics accurately [39].

Q5: I encountered an "FFT error" or high memory usage when calculating MSD for a long trajectory. How can I resolve this?

The standard "windowed" MSD algorithm scales with ( N^2 ) with respect to the number of frames, making it computationally intensive for long trajectories [39]. You can:

- Use a Fast Fourier Transform (FFT)-based algorithm, which scales as ( N \log(N) ) and is much faster [39]. In

MDAnalysis, this is enabled by settingfft=True(requires thetidynamicspackage) [39]. - If memory remains an issue, strategically use the

start,stop, andstepkeywords to analyze a subset of frames [39].

Troubleshooting Guide

The table below outlines common issues, their potential causes, and recommended solutions.

Table 1: Troubleshooting Common MSD Implementation Issues

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Non-linear MSD at long lag times | Poor statistics due to fewer averages for large ( \tau ) [39]. | Use the FFT-based algorithm for better averaging. Do not use the noisy long-time data for diffusion coefficient fitting [39]. |

| MSD value is too low | 1. Using wrapped instead of unwrapped coordinates [39].2. Incorrect dimensionality (msd_type) in calculation [39]. |

1. Always pre-process your trajectory to "unwrap" coordinates or correct for periodic boundary conditions [39].2. Double-check that the msd_type (e.g., 'xyz' for 3D) matches your system and intent [39]. |

| No spark/ignition during MSD testing | Loose connection, faulty ground, or voltage drop during cranking [42]. | Check all connections, especially heavy-gauge power and ground wires. Verify 12V on the small red wire both with key-on and during cranking [42]. |

| High variability in D between replicates | 1. Simulation is too short.2. Insufficient particles for ensemble average. | 1. Run longer simulations to improve statistics.2. For a single-particle MSD, average over multiple independent trajectories. For molecular systems, average over all molecules of the same type [38] [39]. |

| Error when importing FFT-based MSD module | Missing required software package. | For MDAnalysis with fft=True, ensure the tidynamics Python package is installed [39]. |

Experimental Protocols for Robust MSD Analysis

Protocol 1: Basic MSD Calculation and Diffusion Coefficient Fitting

This protocol outlines the steps for a standard MSD analysis from a single particle trajectory [41].

- Data Preparation: Load your trajectory data. Ensure it is in the unwrapped convention. The data should be a matrix with columns for time, x, y, and z coordinates.

- Calculate Displacements: For each time lag ( \tau ), compute the squared displacement for all possible time intervals of length ( \tau ) within the trajectory: ( \text{squared displacement} = (x(t+\tau) - x(t))^2 + (y(t+\tau) - y(t))^2 + (z(t+\tau) - z(t))^2 ).

- Average: Compute the MSD for each ( \tau ) by averaging all the squared displacements calculated for that ( \tau ) [41].

- Identify Linear Regime: Plot the MSD against lag time on a log-log scale. The linear (diffusive) regime is identified by a segment with a slope of 1 [39].

- Linear Fit: On a linear plot, perform a linear regression (e.g., using

scipy.stats.linregress) on the MSD values within the identified linear regime [39]. - Calculate D: Extract the slope from the linear fit. The self-diffusion coefficient for a 3D system is ( D = \frac{\text{slope}}{6} ) [39].

Protocol 2: Combining Multiple Trajectory Replicates

To improve statistics, it is best practice to combine results from multiple independent replicates [39].

- Calculate Individual MSDs: Compute the MSD for each particle (or each trajectory replicate) separately. Software like

MDAnalysisprovidesresults.msds_by_particlefor this purpose [39]. - Combine Data: Concatenate the MSD arrays from all replicates. Do not simply concatenate the trajectory files, as the jump between the end of one trajectory and the start of the next will artifactually inflate the MSD [39].

- Ensemble Average: Calculate the final MSD by taking the mean across all particles and replicates for each time lag:

average_msd = np.mean(combined_msds, axis=1)[39].

The following workflow diagram summarizes the key steps for a robust MSD analysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Software

Table 2: Key Software Tools for MSD Analysis

| Tool Name | Primary Function | Key Feature | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

GROMACS (gmx msd) |

Molecular Dynamics Analysis | Calculates MSD and diffusion coefficients from MD trajectories directly. Can use center-of-mass positions for molecules [38]. | GROMACS Manual |

MDAnalysis (EinsteinMSD) |

Trajectory Analysis in Python | Flexible Python library; supports FFT-accelerated MSD calculation and analysis of trajectories from various simulation packages [39]. | MDAnalysis Docs |

| @msdanalyzer | Particle Tracking in MATLAB | A dedicated MATLAB class for analyzing particle trajectories from microscopy, capable of handling tracks with gaps and variable lengths [40]. | MATLAB File Exchange |

| Custom MATLAB/Python Scripts | Algorithm Development | Allows for full customization of the MSD calculation protocol, ideal for testing new methods or handling unique data formats [41]. | Devzery |

| PQM-164 | PQM-164, MF:C18H18N2O5, MW:342.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| MJ34 | MJ34, MF:C19H17N5, MW:315.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Utilizing Velocity Autocorrelation Function (VACF) as a Complementary Approach

The Velocity Autocorrelation Function (VACF) provides a powerful foundation for calculating transport properties in molecular systems, serving as a robust complementary approach to traditional Mean Squared Displacement (MSD) methods. Within statistical diffusion coefficient research, VACF analysis offers distinct advantages for understanding short-time dynamics and validating results obtained through other methodologies. This technical guide establishes comprehensive protocols for implementing VACF analysis, addressing common computational challenges researchers encounter when studying molecular diffusion in complex systems, including those relevant to drug development.

Core Theoretical Framework

VACF Fundamentals and Definition

The Velocity Autocorrelation Function quantifies how a particle's velocity correlates with itself over time, providing fundamental insights into molecular motion and memory effects within a system. The VACF is mathematically defined as:

[ C_{vv}(t) = \langle \vec{v}(t) \cdot \vec{v}(0) \rangle ]

where (\vec{v}(t)) represents the velocity vector of a particle at time (t), and the angle brackets denote an ensemble average over all particles and time origins. For researchers studying diffusion in biomolecular systems or drug delivery platforms, this function encapsulates essential information about how molecular motion evolves and decorrelates over time.

Green-Kubo Relation for Diffusion

The connection between microscopic dynamics and macroscopic transport properties is established through the Green-Kubo relation, which defines the diffusion coefficient (D) as the time integral of the VACF:

[ D = \frac{1}{3} \int_{0}^{\infty} \langle \vec{v}(t) \cdot \vec{v}(0) \rangle dt ]

This integral relationship transforms the detailed velocity correlation information into a quantitative diffusion coefficient, making VACF an indispensable tool for researchers requiring precise diffusion measurements in pharmaceutical development and materials science applications.

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Molecular Dynamics Setup for VACF Analysis

Proper molecular dynamics (MD) simulation setup is crucial for obtaining reliable VACF data. The following protocol outlines the essential steps for configuring simulations optimized for VACF analysis:

System Preparation:

- Construct simulation box with appropriate periodic boundary conditions

- Solvate molecules of interest using explicit solvent models relevant to your biological system

- Implement energy minimization to remove steric clashes and unfavorable contacts

- Apply gradual heating phase to reach target physiological temperature (typically 300-310K for biological systems)

- Conduct equilibration phase in NPT ensemble to achieve correct density

Production MD Parameters:

- Use sufficiently small time step (0.5-2.0 fs) to accurately capture molecular vibrations

- Enable velocity tracking in trajectory output settings

- Set trajectory sampling frequency to capture relevant dynamics (typically 1-10 ps intervals)

- Implement Langevin dynamics or Nosé-Hoover thermostat for temperature control

- Ensure sufficient simulation length to achieve proper VACF convergence (typically nanoseconds for small molecules)

VACF Calculation Methodology

Implementing robust VACF calculations requires careful attention to numerical methods and statistical averaging:

Velocity Extraction:

- Extract atomic velocities from MD trajectory files at regular intervals

- Ensure consistent units throughout analysis (typically Ã…/ps or m/s)

- Apply molecular center-of-mass motion removal if studying internal dynamics

Correlation Computation:

- Implement discrete correlation algorithm with proper normalization

- Utilize Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) methods for computational efficiency with large datasets

- Apply multiple time origin averaging to improve statistical precision

- Segment long trajectories into independent blocks for error estimation

Complete VACF Analysis Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive workflow for VACF-based diffusion analysis:

Troubleshooting Guide: Common VACF Issues and Solutions

Numerical Integration and Convergence Problems

Problem: Non-converging VACF integral leading to unreliable diffusion coefficients

- Symptoms: Diffusion coefficient values that continuously increase or oscillate with integration limit

- Root Causes: Insufficient simulation length, poor statistics, or strong persistent correlations

- Solutions:

- Extend simulation time to at least 5-10× the VACF decay time

- Implement block averaging to quantify statistical uncertainties

- Apply appropriate fitting functions to extrapolate tail behavior

- Increase system size to improve ensemble averaging

Problem: Noisy VACF at long time scales

- Symptoms: High variance in correlation function after initial decay

- Root Causes: Inadequate sampling of rare events or insufficient trajectory frames

- Solutions:

- Increase sampling frequency during MD production phase

- Implement multiple time origin averaging with overlapping segments

- Apply Savitzky-Golay filtering or moving average smoothing

- Use longer production runs with distributed computing resources

Technical Implementation Challenges

Problem: Memory limitations with large trajectory datasets

- Symptoms: System crashes or performance degradation during VACF calculation

- Root Causes: Storing complete velocity history for large systems

- Solutions:

- Implement on-the-fly VACF calculation during MD simulation

- Use stride-based sampling to reduce data storage requirements

- Employ chunked processing of trajectory data

- Utilize distributed memory parallelization across compute nodes

Problem: Inconsistent units leading to incorrect diffusion values

- Symptoms: Physically implausible diffusion coefficients (orders of magnitude off)

- Root Causes: Unit conversion errors between different MD packages

- Solutions:

- Establish consistent unit protocol (prefer SI units: m, s, kg)

- Create validation tests with known analytical solutions

- Implement unit consistency checks within analysis pipeline

- Document unit conversion factors explicitly in code

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Methodology and Implementation

Q1: How does VACF compare to MSD for diffusion coefficient calculation? VACF and MSD provide complementary approaches to diffusion measurement. While MSD directly measures spatial spreading, VACF probes the underlying dynamics through velocity correlations. VACF typically converges faster for diffusion coefficients in homogeneous systems and provides better resolution of short-time dynamics. However, MSD often performs better in heterogeneous environments or when studying anomalous diffusion.

Q2: What is the minimum simulation time required for reliable VACF analysis? The required simulation duration depends on the system size and correlation times. As a general guideline, simulations should extend to at least 5-10 times the characteristic decay time of the VACF. For typical liquid systems at room temperature, this translates to 1-10 nanoseconds, though complex biomolecular systems may require significantly longer sampling (100+ nanoseconds) to achieve convergence.

Q3: How do I handle VACF analysis for multi-component systems? For systems with multiple component types (e.g., solvent and solute), calculate separate VACFs for each species. Cross-correlations between different species can provide additional insights into collective dynamics and interaction mechanisms. Ensure proper labeling and tracking of atom types throughout the analysis pipeline.

Technical and Computational Questions

Q4: What sampling frequency should I use for velocity output? The optimal sampling frequency balances temporal resolution with storage constraints. As a rule of thumb, sample at least 10-100 points during the VACF decay period. For most molecular systems, sampling every 1-10 femtoseconds captures the essential dynamics, though faster vibrations may require higher resolution.

Q5: How can I validate my VACF implementation? Establish validation protocols using known analytical solutions:

- Ideal gas systems should yield VACF(t) = constant

- Harmonic oscillators produce oscillatory VACFs

- Simple liquids should show exponential-like decay

- Compare with MSD-derived diffusion coefficients for consistency

- Test against published benchmark systems in literature

Q6: What are the implications of negative regions in the VACF? Negative regions in the VACF indicate "back-scattering" or caging effects, where particles reverse direction due to interactions with neighbors. This is physically meaningful in dense liquids and provides insights into local structure and collective dynamics. The specific timing and magnitude of negative dips reveal information about local rearrangement timescales.

Quantitative Data Reference Tables

Characteristic VACF Parameters for Common Systems

Table 1: Typical VACF decay times and diffusion coefficients for representative molecular systems at 300K

| System | VACF Decay Time (fs) | Oscillation Features | Diffusion Coefficient (m²/s) | Recommended Simulation Length |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Water (SPC/E) | 50-100 | None | 2.3-2.5 × 10â»â¹ | 1-5 ns |

| Ionic Liquids | 200-500 | Weak damping | 10â»Â¹Â¹-10â»Â¹â° | 10-50 ns |

| Simple Alcohols | 100-200 | None | 0.5-1.5 × 10â»â¹ | 2-10 ns |

| Lipid Bilayers | 500-2000 | Pronounced negative region | 10â»Â¹Â²-10â»Â¹â° | 50-200 ns |

| Protein Hydration Shell | 100-300 | Damped oscillation | 0.5-1.5 × 10â»â¹ | 10-50 ns |

Error Analysis and Convergence Metrics

Table 2: Statistical metrics for assessing VACF reliability and convergence

| Metric | Calculation Method | Acceptable Threshold | Improvement Strategies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Block Averaging Error | Standard deviation across trajectory blocks | <10% of mean value | Increase simulation length, larger blocks |

| Integration Convergence | Relative change with increased upper limit | <5% variation | Longer simulations, tail extrapolation |

| Signal-to-Noise Ratio | Initial amplitude to noise floor ratio | >20:1 | Better sampling, system size increase |

| Cross-Validation with MSD | DVACF/DMSD = 0.8-1.2 | Extended sampling, multiple replicates |

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential software tools for VACF analysis and molecular dynamics simulations

| Tool/Software | Primary Function | Key Features | System Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|

| AMS/PLAMS [43] | Molecular dynamics and analysis | Built-in VACF functions, diffusion coefficient calculation | Python environment, 8+ GB RAM |

| MD Packages (GROMACS, NAMD, LAMMPS) | Production MD simulations | High performance, velocity output options | High-performance computing resources |

| NumPy/SciPy | Numerical analysis | FFT implementation, numerical integration | Python scientific stack |

| Visualization Tools (VMD, PyMol) | Trajectory inspection | Structure validation, animation | GPU acceleration recommended |

| Custom Python Scripts | Analysis pipeline | Flexibility, method customization | Development environment |