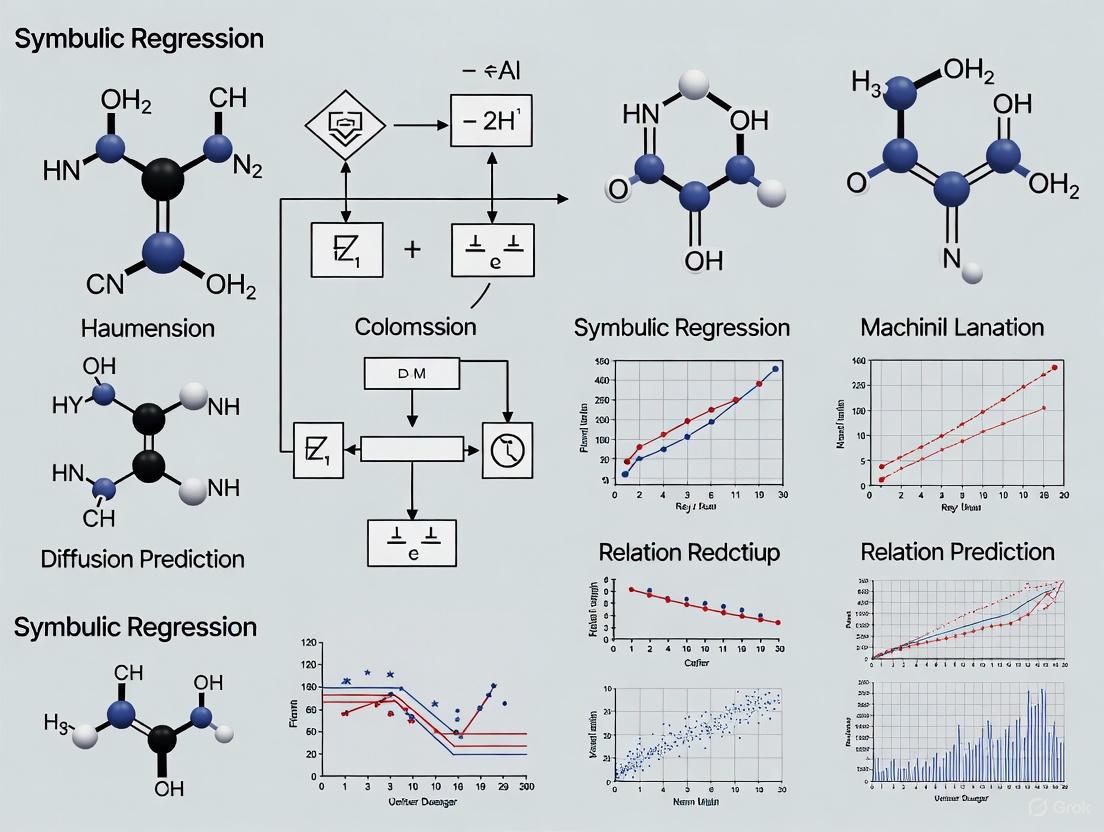

Harnessing Diffusion Models for Symbolic Regression in Drug Discovery and Clinical Prediction

This article explores the cutting-edge integration of diffusion models with symbolic regression (SR) for predictive modeling in biomedical research.

Harnessing Diffusion Models for Symbolic Regression in Drug Discovery and Clinical Prediction

Abstract

This article explores the cutting-edge integration of diffusion models with symbolic regression (SR) for predictive modeling in biomedical research. We provide a comprehensive overview tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, covering the foundational principles of this hybrid approach, its novel methodologies, and its practical applications in areas such as predicting drug binding and constructing interpretable clinical models. The content further addresses key computational challenges and optimization strategies for real-world deployment, presents a comparative analysis with established machine learning and genetic programming methods, and concludes with future directions for harnessing these interpretable, high-performance models to accelerate therapeutic development.

The New Frontier: Understanding Symbolic Regression and Diffusion Models

What is Symbolic Regression? Moving Beyond Black-Box Machine Learning

Symbolic Regression (SR) is a type of supervised machine learning that searches for mathematical expressions to fit a dataset. Unlike traditional methods that tune parameters within a fixed model, SR dynamically explores the space of possible mathematical expressions—adjusting the number, order, and type of operations and parameters—to discover the underlying governing equation [1]. This process results in inherently interpretable, white-box models in the form of compact, analytical equations, making it a powerful alternative to complex, opaque "black-box" models like deep neural networks [2] [3].

Core Principles: How Symbolic Regression Works

The fundamental goal of SR is to find a mathematical function, ( \hat{f}(\mathbf{x}, \mathbf{\hat{\theta}}) ), that closely approximates the relationship between input variables ( \mathbf{x} ) and output variable ( y ) in a dataset [4]. Its unique characteristic is the diminished need for prior knowledge about the investigated system, as it can uncover profound physical relations directly from data [2].

Several technical approaches exist for conducting symbolic regression:

- Genetic Programming (GP): The traditional and dominant approach, inspired by biological evolution. It starts with a population of random expressions and iteratively refines them over many generations using genetic operations like selection, crossover, and mutation [1] [2].

- Deep Symbolic Regression (DSR): This method uses a Recurrent Neural Network (RNN) to generate expressions and employs reinforcement learning, specifically a risk-seeking policy gradient, to train the network [1].

- Diffusion-Based Methods: A novel approach that adapts the powerful diffusion framework from image generation. It uses a forward process to gradually mask tokens and a reverse denoising process to construct equations, integrated with reinforcement learning for efficient training [1].

- Feature Engineering Automation Tool (FEAT): A specific symbolic regression method that uses Pareto optimization to jointly optimize model discrimination and complexity, producing compact and accurate models [5] [6].

The following diagram illustrates the high-level workflow and key algorithms in SR.

Performance Comparison: Symbolic Regression vs. Other Techniques

Benchmarking studies, such as the extensive SRBench, provide empirical data on how SR algorithms perform against each other and against standard machine learning models [4]. The key differentiator of SR is its ability to provide a superior trade-off between performance and interpretability.

The table below summarizes a qualitative comparison based on data from benchmark studies and application papers [7] [5] [2].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Modeling Techniques

| Model Type | Interpretability | Model Form | Feature Engineering | Typical Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symbolic Regression | High (Inherently interpretable) | Mathematical equation | Automatic selection | Scientific discovery, interpretable prediction |

| Linear / Penalized Regression | High | Predefined linear equation | Critical | Baseline modeling, well-understood linear relationships |

| Decision Trees / Random Forests | Medium to High | Tree structure | Helpful | General-purpose ML, feature importance analysis |

| Neural Networks (Deep Learning) | Low (Black-box) | Complex network of neurons | Critical | High-accuracy prediction where interpretability is secondary |

Quantitative results from recent research demonstrate SR's capability to compete with or even surpass other methods:

Table 2: Selected Experimental Performance Data

| Application Domain | Benchmark / Method | SR Method | Performance & Model Complexity | Comparison vs. Other Models |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical Phenotyping (aTRH) [5] | EHR Data (Chart Review) | FEAT | AUPRC: 0.70 (PPV), Model Size: 6 features [5] | Higher AUPRC and ≥3x smaller than other interpretable models (LR L1, LR L2, DT) [5] |

| Hybrid FRP Bolted Connections [7] | Damage Initiation Load Prediction | PySR | Compact interpretable equation [7] | Provided greater accuracy and deeper physical insight than best-performing black-box model (Huber Regression) [7] |

| SRBench (Black-Box Problems) [4] | ~100 Diverse Datasets | Multiple Top SR Methods | Favorable complexity-performance trade-off [4] | Lies on the Pareto frontier against ML models (Random Forest, XGBoost, etc.) [4] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

To ensure reproducible and meaningful results, SR experiments follow structured protocols. The following "research reagent solutions" table outlines key components of a typical SR experimental setup.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Symbolic Regression

| Item / Component | Function / Description | Example Instances |

|---|---|---|

| SR Software / Algorithm | The core engine that performs the symbolic search. | PySR (Python Symbolic Regression) [7], FEAT (Feature Engineering Automation Tool) [5], TuringBot [8], GP-based frameworks [3] |

| Benchmark Suite | Standardized datasets to train, test, and compare algorithm performance. | SRBench [4], PMLB (Penn Machine Learning Benchmark) [5] |

| Fitness Metric | A measure to evaluate the quality of a candidate expression against data. | Mean Squared Error (MSE), R², Normalized Akaike Information Criterion (for complexity) [2] |

| Operators & Functions | The basic mathematical building blocks for constructing expressions. | Arithmetic (+, -, ×, ÷), Exponents, Trigonometry (sin, cos), Logarithms [8] |

| Complexity Measure | A metric to constrain model size and avoid overfitting. | Expression tree depth, number of terms [9], task-specific SGPA complexity [9] |

| Validation Framework | Method to assess the generalizability and robustness of discovered models. | Train/Test split, k-fold cross-validation, performance on noisy or out-of-domain data [2] [3] |

A generalized experimental workflow, as applied in fields like materials science and clinical medicine, can be visualized as follows.

Detailed Methodological Description:

Data Acquisition and Preprocessing: The process begins with gathering high-quality data, which can originate from physical experiments (e.g., mechanical testing of composite materials) [7], Finite Element Modeling (FEM) [7], or Electronic Health Records (EHR) [5]. A hybrid Design of Experiments (DoE) approach, combining Central Composite Design (CCD) and Box-Behnken Design (BBD), is often used to structure the dataset for comprehensive exploration of parameter interactions [7]. Data is typically split into training and testing sets.

SR Experimental Setup:

- Algorithm Selection: Researchers choose an SR method (e.g., PySR, FEAT) suitable for the problem [7] [5].

- Configuration: Key hyperparameters are defined, including the set of mathematical operators and functions, population size (for GP-based methods), and complexity constraints to prevent overfitting.

- Optimization: The SR algorithm executes its search. For example, FEAT uses Pareto optimization to balance model accuracy and complexity [5], while Bayesian GPSR uses model evidence to guide evolution and quantify uncertainty in constants [3].

Model Evaluation and Validation: The final, best-performing equations are rigorously validated. This involves assessing predictive accuracy on the held-out test set and comparing performance against benchmark models (e.g., Huber regression, Random Forests) [7]. Crucially, the interpretability of the model is analyzed to extract physical or clinical insights [7] [5].

Key Applications in Research and Industry

The unique advantages of SR have led to its successful application across diverse, high-stakes fields:

- Engineering and Materials Science: Used to derive interpretable models for predicting damage initiation in complex structures like hybrid Fiber-Reinforced Polymer (FRP) bolted connections, providing greater physical insight than black-box alternatives [7].

- Clinical Medicine and Healthcare: Employed to build accurate and intuitively interpretable prediction models for conditions like hypertension from EHR data, facilitating clinical decision support (CDS) by providing transparent reasoning [5] [6].

- Scientific Discovery: SR acts as an "automated Kepler," discovering analytical expressions and physical laws directly from experimental data in fields like physics [4] [3].

- Drug Discovery: While other ML paradigms like deep learning are more common, SR's interpretability makes it a promising tool for uncovering clear, actionable relationships in pharmaceutical research [10].

The Future of Symbolic Regression

The field is rapidly evolving, with current research focusing on several key frontiers:

- Next-Generation Benchmarking: Efforts like SRBench 2.0 aim to provide more nuanced, large-scale, and standardized benchmarking to fairly compare the growing diversity of SR algorithms [4].

- Defining Complexity: Moving beyond simple metrics like equation length, researchers are developing task-specific complexity measures. One example is quantifying the difficulty of performing a Single-Feature Global Perturbation Analysis (SGPA), which aligns better with practical analytical tasks [9].

- Uncertainty Quantification: Bayesian frameworks are being integrated into GP-based SR to quantify uncertainty in the constants of discovered equations, enabling probabilistic predictions and improving robustness to noisy data [3].

- Advanced Algorithms: New methods, such as diffusion-based SR (DDSR), are emerging, leveraging state-of-the-art generative models to produce more diverse and high-quality equations [1].

Diffusion models have emerged as a dominant force in generative artificial intelligence (GenAI), revolutionizing the creation and manipulation of digital content. Initially gaining widespread recognition for their exceptional capability in photorealistic image generation and text-to-image synthesis, these models have rapidly transcended their origins in creative applications. Today, diffusion models are pioneering new frontiers in scientific discovery and industrial innovation, offering unprecedented tools for researchers tackling some of the most complex challenges in fields ranging from drug development to materials science. The fundamental principle underlying diffusion models—a process of iteratively adding and removing noise to transform data distributions—has proven remarkably adaptable across domains, enabling both data generation and sophisticated prediction tasks that align with the objectives of symbolic regression research.

This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of diffusion model architectures, performance, and applications, with particular emphasis on their emerging role in scientific contexts. We objectively evaluate their capabilities against alternative generative approaches, present quantitative performance data, detail experimental methodologies, and visualize key workflows to equip researchers and drug development professionals with the insights needed to leverage these transformative technologies in their own pioneering work.

Comparative Analysis: Diffusion Models Versus Alternative Generative Architectures

Technical Architecture Comparison

The landscape of generative AI is primarily dominated by three architectural paradigms: Diffusion Models, Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), and Variational Autoencoders (VAEs). Each employs distinct mathematical frameworks and learning mechanisms, resulting in different performance characteristics suited to particular applications.

Table 1: Architectural Comparison of Major Generative Model Families

| Architectural Feature | Diffusion Models | Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) | Variational Autoencoders (VAEs) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Mechanism | Iterative denoising process | Adversarial training between generator and discriminator | Probabilistic encoding/decoding with latent space regularization |

| Training Stability | High stability with predictable convergence | Notoriously unstable; requires careful balancing | Generally stable training |

| Sample Diversity | High diversity; excellent mode coverage | Prone to mode collapse (limited diversity) | Moderate diversity with blurrier outputs |

| Inference Speed | Slower due to iterative sampling | Very fast single-pass generation | Fast single-pass generation |

| Computational Demand | High during training and inference | Moderate to high during training | Generally lower requirements |

| Output Fidelity | Exceptional detail and coherence | High perceptual quality but potential artifacts | Often softer, less detailed outputs |

Diffusion models operate through a forward and reverse process. The forward process systematically adds Gaussian noise to training data over multiple steps until the original structure is destroyed, while the reverse process trains a neural network to learn to denoise, effectively learning the data distribution by reversing this noising process [11]. This approach differs fundamentally from GANs, which employ a game-theoretic framework where a generator network creates samples intended to fool a discriminator network that distinguishes real from generated data [12] [11]. VAEs take a probabilistic approach, learning to encode inputs into a compressed latent representation and then decode this representation back to something resembling the original input, with the latent space regularized to follow a known probability distribution [12].

Performance Benchmarking Across Domains

Quantitative evaluation reveals distinct performance trade-offs between generative architectures, with each demonstrating strengths in different metrics and application contexts.

Table 2: Performance Comparison on Scientific Image Generation Tasks

| Model Architecture | FID (↓) | SSIM (↑) | LPIPS (↓) | CLIPScore (↑) | Training Stability | Inference Speed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diffusion Models (DALL-E 2) | 12.5 | 0.71 | 0.22 | 0.81 | High | Slow |

| GANs (StyleGAN) | 10.8 | 0.69 | 0.19 | 0.76 | Low | Fast |

| VAEs | 25.3 | 0.65 | 0.31 | 0.68 | High | Fast |

Note: Evaluation conducted on domain-specific datasets including microCT scans of rocks and composite fibers, and high-resolution plant root images. Lower scores are better for FID and LPIPS, while higher scores are better for SSIM and CLIPScore [12].

In scientific imaging applications, GANs—particularly StyleGAN architectures—have demonstrated superior performance in generating images with high structural coherence and perceptual quality, achieving the lowest Fréchet Inception Distance (FID) scores, which measure the similarity between generated and real images [12]. However, diffusion-based models like DALL-E 2 excel in semantic alignment with text prompts, as reflected in superior CLIPScores, making them particularly valuable for conditioned generation tasks where following precise instructions is critical [12].

For edge deployment scenarios where computational resources are constrained, compact diffusion models have emerged as particularly efficient solutions. The FLUX family of models, with approximately 12 billion parameters, demonstrates the evolving balance between performance and efficiency, enabling high-quality generation on resource-constrained hardware [13].

Diffusion Models in Scientific Discovery: Methodologies and Applications

Scientific Image Generation and Enhancement

In scientific domains, diffusion models are being deployed for both data augmentation and image enhancement tasks, helping researchers overcome data scarcity and quality limitations. Experimental protocols in this domain typically involve:

Data Acquisition and Preprocessing: Scientific images (e.g., microCT scans, microscopic images, satellite imagery) are collected and standardized. For medical applications, this often involves de-identification and normalization of intensity values [12] [14].

Conditioning Strategy: Models are conditioned on relevant parameters—such as text prompts, reference images, or scientific constraints—to guide the generation process toward scientifically valid outputs [12].

Iterative Refinement: The diffusion process iteratively refines outputs through a series of denoising steps, with the number of iterations typically ranging from 10-1000 depending on the desired output quality and computational constraints [12] [11].

Validation: Generated images undergo both quantitative assessment using metrics like SSIM, FID, and LPIPS, and qualitative evaluation by domain experts to ensure scientific accuracy [12].

A significant challenge in scientific applications is that standard quantitative metrics often fail to capture scientific relevance, underscoring the necessity of domain-expert validation alongside computational evaluation [12]. For instance, a visually compelling generated image of a cellular structure might violate fundamental biological principles, making it scientifically useless despite its perceptual quality.

Drug Discovery and Molecular Design

In pharmaceutical research, diffusion models are accelerating drug discovery by generating novel molecular structures with desired properties—a process conceptually analogous to symbolic regression but applied to molecular space rather than equation space. The typical experimental workflow involves:

Diagram 1: Molecular design workflow using diffusion models

Data Curation: Collection of 3D molecular structures with associated properties from databases like PubChem or proprietary corporate collections [15] [16].

Conditional Model Training: Diffusion models are trained to generate 3D molecular structures conditioned on desired properties such as binding affinity, solubility, or metabolic stability [15].

Sampling and Optimization: The trained model generates novel molecular candidates through iterative denoising, with the process often guided by optimization algorithms to explore the chemical space more efficiently [15].

In Silico Validation: Generated molecules undergo computational screening using molecular dynamics simulations and docking studies to predict binding behavior and other relevant characteristics [15].

Experimental Testing: Promising candidates are synthesized and tested in laboratory assays to validate predicted properties [15].

Researchers have successfully merged diffusion models with protein-folding AI like RoseTTAFold, starting with random 3D noise and iteratively "cleaning" it into novel proteins that fold stably, latch onto disease targets, or catalyze reactions [15]. This approach has already produced hundreds of AI-generated proteins that have passed laboratory tests, demonstrating the practical potential of these methods [15].

Scientific Simulation and Digital Twins

Diffusion models are increasingly deployed to create sophisticated simulations and digital twins of complex scientific systems, enabling researchers to explore scenarios that would be prohibitively expensive, dangerous, or time-consuming to study in reality.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Diffusion Model Experimentation

| Resource Category | Specific Tools | Function/Purpose | Accessibility |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model Architectures | DALL-E 2/3, Imagen, Stable Diffusion, FLUX | Core generative engines for different data types | Various licensing models; some open-source |

| Training Frameworks | PyTorch, TensorFlow, JAX | Model development and training environment | Open-source |

| Scientific Datasets | microCT scans, molecular databases, medical imaging repositories | Domain-specific training data and benchmarks | Public and proprietary |

| Evaluation Metrics | FID, SSIM, LPIPS, CLIPScore, custom domain metrics | Quantifying model performance and output quality | Open-source implementations |

| Specialized Libraries | Diffusers, OpenFold, RDKit | Domain-specific preprocessing and analysis | Predominantly open-source |

Digital twins represent one of the most promising applications, creating virtual replicas of physical systems that can simulate complex processes under different conditions while assimilating new data and human feedback [16]. These AI-powered simulators are being developed for diverse applications including social interaction modeling, traffic control policy testing, and environmental monitoring [16]. The foundational capability of diffusion models to capture complex data distributions makes them particularly well-suited for these applications where representing realistic variability is essential.

Diagram 2: Digital twin creation using diffusion models

Future Directions and Research Challenges

Despite their remarkable capabilities, diffusion models face significant challenges in scientific applications. Computational demands remain substantial, though quantization techniques and specialized hardware are gradually mitigating these constraints [17]. The critical challenge of model interpretability persists, particularly in high-stakes domains like drug discovery where understanding the rationale behind generated candidates is essential for validation and regulatory approval [12] [16].

The phenomenon of hallucination—where models generate scientifically implausible outputs—represents a particular concern in scientific contexts, potentially leading researchers down unproductive paths or reinforcing misconceptions [12] [16]. Addressing this requires incorporating scientific knowledge and constraints directly into the modeling process, an area of active research sometimes termed "scientific AI" or "AI for science" [16].

Looking forward, diffusion models are poised to expand further into inverse design problems across scientific domains, generating structures that meet target properties in fields as diverse as materials science, pharmacology, and renewable energy [15]. Their ability to work with multi-modal and multi-scale data positions them as ideal tools for integrating diverse scientific data sources, from molecular simulations to clinical observations [16]. As these models continue to evolve, they will likely become increasingly embedded in the scientific workflow, accelerating discovery across traditionally distinct disciplines and potentially revealing connections that have previously eluded human researchers.

For the research community, the ongoing development of more efficient architectures, improved training methodologies, and better integration with scientific knowledge bases will determine how rapidly diffusion models transition from impressive research tools to indispensable components of the scientific toolkit.

Why Combine Them? The Promise of Interpretable, High-Fidelity Generative SR

In the field of symbolic regression (SR), the pursuit of models that are both interpretable and capable of capturing complex, high-fidelity dynamics has been a long-standing challenge. Traditional methods often force a trade-off between these two objectives. However, the emergence of generative symbolic regression models represents a paradigm shift, combining the physical interpretability of classical SR with the powerful pattern recognition of deep learning. This guide objectively compares the performance of one such model, KinFormer, against other SR alternatives, focusing on its application in predicting reaction kinetics—a critical task in drug development and material science.

Experimental Comparisons

The following tables summarize quantitative data from a rigorous evaluation of KinFormer against established symbolic regression methods across 20 catalytic organic reactions [18]. Performance was measured on a challenging cross-category generalization task, where models were tested on reaction mechanisms not seen during training.

Table 1: Cross-Category Generalization Performance This table compares the accuracy of different models in predicting the correct form of differential equations for unseen reaction types.

| Model / Category | Traditional Symbolic Regression | Neural SR (ODEFormer) | Generative SR (KinFormer) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model Example | SINDy, PySR | ODEFormer | KinFormer |

| Equation Form Accuracy | ~50% | ~50% | 81.41% [18] |

| Key Advantage | Strong baseline | End-to-end training | Conditioned generation & MCTS |

Table 2: Performance on Noisy and Real-World Data Conditions This table compares model robustness when dealing with imperfect data, a common scenario in laboratory settings.

| Evaluation Metric | Traditional SR | Neural SR (ODEFormer) | Generative SR (KinFormer) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Robustness to Noise (e.g., Gaussian noise σ=1e-4) | Performance often degrades significantly | Moderate robustness | High robustness; accurately predicts concentration trajectories [18] |

| Physical Consistency | Built-in via constraints | Often violated | High; implicit learning of physical laws (e.g., mass conservation) [18] |

| Search Efficiency | Computationally expensive | N/A | MCTS converges within 20 iterations, ~3x faster than beam search [18] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

The experimental data cited in this guide is primarily derived from the study "KinFormer: Generalizable Dynamical Symbolic Regression for Catalytic Organic Reaction Kinetics" presented at ICLR 2025 [18]. Below is a detailed description of the key methodologies used to generate the comparative results.

Dataset Curation and Task Design

- Data Source: The experiments were conducted on a comprehensive dataset encompassing 20 distinct classes of catalytic organic reactions [18]. This included fundamental mechanisms, dual-catalytic systems, and reactions involving catalyst activation or deactivation.

- Task Formulation: The core task was dynamical symbolic regression. Given experimentally measured, time-dependent concentration profiles of reactant and product species, the models were required to discover the underlying system of ordinary differential equations (ODEs) that describe the reaction kinetics.

- Evaluation Paradigm: The most significant evaluation was the cross-category generalization test. In this setup, models were trained on a set of reaction mechanisms but tested on mechanisms of a different category that were entirely absent from the training set. This rigorously assesses a model's ability to discover genuinely new kinetics, rather than memorizing or slightly varying known equations.

KinFormer's Conditioning and Training Protocol

KinFormer introduces a novel training strategy to overcome the generalization limitations of standard end-to-end models [18].

- Conditional Training: Instead of generating an entire system of ODEs in one step, KinFormer was trained on a "condition-and-predict" task. During training, for a given set of ground-truth ODEs, a random subset of these equations was provided as input (the condition). The model was then tasked with predicting the next correct equation in the sequence.

- Objective: This method forces the model to implicitly learn the underlying physical dependencies and conservation laws (like the mass action law) that link different equations within a system, rather than memorizing fixed equation sets.

Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS) for Equation Generation

At inference time, KinFormer employs a guided search to generate physically consistent equations [18].

- Process: Each differential equation to be generated is treated as a node in a search tree. The MCTS module explores different sequences in which the full set of equations could be generated.

- Reward Signal: Candidate equation sequences are evaluated by simulating the ODE system they define and comparing the resulting concentration trajectories to the observed experimental data. A reward is calculated based on metrics like the R² score (denoted as r2m and r2M in the research).

- Optimization: This reward is backpropagated through the search tree, allowing the MCTS to intelligently explore and converge on the sequence of equations that yields the most physically accurate and self-consistent system.

Model Architecture and Workflow Visualization

The diagram below illustrates the core operational workflow of the KinFormer model, highlighting its key innovations in conditional generation and Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key computational and data resources essential for working with generative symbolic regression models in a kinetic modeling context.

| Item | Function / Description |

|---|---|

| Catalytic Reaction Dataset | A curated dataset of time-series concentration profiles for various organic reactions (e.g., dual-catalytic systems, catalyst activation). Serves as the ground truth for training and evaluation [18]. |

| Conditional Training Framework | A software framework that implements the "condition-and-predict" training protocol, crucial for teaching the model the physical relationships between equations in a system [18]. |

| Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS) Library | A computational module that performs the intelligent, global search for optimal equation sequences during model inference, using simulation rewards to guide the process [18]. |

| Numerical ODE Simulator | A high-fidelity differential equation solver used to simulate candidate kinetic models generated by the SR system, enabling the calculation of reward signals and validation against experimental data [18]. |

| Sparse Autoencoders | An interpretability tool used to extract human-understandable features from the model's internal representations, helping to decode how physical information is encoded [19]. |

| Glycoursodeoxycholic Acid-D4 | Glycoursodeoxycholic Acid-D4 | Deuterated BA Standard |

| (S,R,S)-AHPC-PEG5-Boc | (S,R,S)-AHPC-PEG5-Boc, MF:C40H62N4O11S, MW:807.0 g/mol |

Symbolic regression (SR) is a machine learning technique that aims to discover mathematical expressions to fit a set of data points, without pre-specifying the model's functional form [2]. Unlike traditional regression that fixes a model equation, SR dynamically explores an open-ended space of mathematical expressions, adjusting the number, order, and type of parameters and operations to find optimal solutions [1]. While genetic programming (GP) has historically dominated this field, recent advances have introduced deep learning approaches, including a novel class of methods utilizing diffusion models adapted from image and audio generation [1] [20].

Diffusion-based symbolic regression repurposes the powerful generative framework of denoising diffusion probabilistic models (DDPMs) for mathematical expression discovery. These models operate through two fundamental processes: a forward diffusion process that systematically adds noise to data, and a reverse generation process that learns to reconstruct data from noise [21]. In the context of symbolic regression, this approach generates diverse and high-quality equations by learning to reverse a corruption process applied to mathematical expressions [1] [22].

Core Conceptual Framework

Denoising Processes

The denoising process forms the foundation of diffusion-based symbolic regression. In continuous domains like images, the forward process gradually adds Gaussian noise to data through a Markov chain [21]. For symbolic expressions represented as discrete token sequences, researchers employ discrete diffusion processes where noise is represented through token masking or corruption [1] [23].

The Discrete Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Model (D3PM) framework defines this forward process for categorical data. Each token in a mathematical expression is represented as a one-hot vector, and the forward process progressively corrupts these tokens toward a uniform distribution using a transition matrix [23]. This corruption can follow either a uniform noising process that gradually makes all tokens equally probable, or an absorbing process that masks tokens to a specific "masked" state [23].

Reverse Generation

The reverse generation process learns to iteratively recover the original mathematical expression from its corrupted state. While the forward process is fixed, the reverse process is learned through neural network training [21]. Starting from fully masked or randomized tokens, the model progressively predicts less corrupted versions of the expression over multiple denoising steps [1] [20].

A key advantage of reverse generation in symbolic regression is its global context - unlike autoregressive models that generate tokens sequentially from left to right, diffusion models update all tokens simultaneously throughout the denoising process [20]. This allows the model to consider the entire expression structure during generation, potentially leading to more coherent and syntactically valid mathematical expressions.

Expression Sampling

Expression sampling refers to the methodology of generating candidate mathematical expressions from the trained diffusion model. After training, sampling begins from random noise or masked tokens, followed by iterative application of the learned reverse process [1]. Two primary approaches exist for this sampling:

- Stochastic sampling introduces randomness during denoising steps, producing diverse expression candidates.

- Deterministic sampling employs algorithms like DDIM or herding-based methods to derandomize the reverse process, potentially improving efficiency and sample quality [23].

The sampling process can be integrated with reinforcement learning strategies, such as the risk-seeking policy used in Diffusion-Based Deep Symbolic Regression (DDSR), which selects top-performing expressions to guide the training process [1].

Comparative Performance Analysis

Experimental Protocols and Benchmarking

Diffusion-based symbolic regression methods are typically evaluated against genetic programming and autoregressive neural approaches using standardized benchmarks. The primary evaluation framework involves:

- Dataset Composition: Models are trained and tested on synthetic datasets with known ground-truth equations (e.g., the bivariate dataset from SymbolicGPT with 500,000 samples) and real-world scientific data [20] [1].

- Performance Metrics: Key metrics include coefficient of determination (R²), symbolic recovery rate (accuracy in retrieving known ground-truth expressions), and model complexity (size of expressions) [1] [20].

- Training Protocols: Diffusion models are typically trained with comparable architectures to their autoregressive counterparts, using similar embedding dimensions, transformer layers, and attention heads for fair comparison [20].

Quantitative Performance Comparison

The table below summarizes experimental results comparing diffusion-based approaches with other symbolic regression methods:

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Symbolic Regression Methods

| Method | Type | R² Score | Symbolic Recovery Rate | Expression Complexity | Inference Speed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DDSR [1] | Diffusion-based | High | Significantly higher than DSR | Simpler expressions | Moderate |

| Symbolic Diffusion [20] | Diffusion-based | Comparable/Improved vs. AR | Similar to autoregressive | Similar complexity | Slower than AR |

| SymbolicGPT [20] | Autoregressive | Baseline for comparison | Baseline for comparison | Similar complexity | Fast |

| Genetic Programming [1] | Evolutionary | High | State-of-the-art | Often complex | Slow |

| DSR [1] | Reinforcement Learning | Lower than DDSR | Lower than DDSR | Moderate | Fast |

Ablation Study Insights

Ablation studies on DDSR demonstrate the individual contributions of its key components:

Table 2: Component Contribution in DDSR Framework

| Component | Effect on Performance | Effect on Training Stability |

|---|---|---|

| Random Mask-Based Diffusion | Enables diverse expression generation | Reduces denoising steps and computational cost |

| Token-wise GRPO | Improves solution accuracy | Enhances training stability via trust region updates |

| Long Short-Term Risk-Seeking | Increases pool of top candidates | Builds more robust model through expanded candidate pool |

Methodological Approaches

Architectural Framework

Diffusion-based symbolic regression models share common architectural components:

- Tokenization: Mathematical expressions are converted to token sequences, often in postfix (Reverse Polish) notation, with constants replaced by placeholder tokens [20].

- Encoder Architecture: PointNet-style encoders process input coordinate data using convolutional layers, batch normalization, and ReLU activations to extract features [20].

- Denoising Network: Transformer-based decoders with embedding dimensions of 512, 8 attention heads, and 8 layers typically form the core denoising architecture [20].

Training Methodologies

Training diffusion models for symbolic regression involves specialized approaches:

- Group Relative Policy Optimization (GRPO): Used in DDSR to conduct efficient reinforcement learning by maximizing per-token denoising likelihood scaled by corresponding rewards [1].

- Risk-Seeking Strategy: Extends the risk-seeking policy from Deep Symbolic Regression (DSR) by maintaining top-performing expressions from all model versions, addressing both long-term and short-term performance [1].

- Variational Bound Optimization: Models are typically trained by minimizing a variational upper bound (NELBO) on the negative log-likelihood [23].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Components for Diffusion-Based Symbolic Regression

| Component | Function | Implementation Examples |

|---|---|---|

| D3PM Framework [23] | Discrete diffusion backbone | Provides categorical corruption and denoising processes |

| Tokenization Scheme | Converts equations to token sequences | Postfix notation with constant placeholders |

| Transformer Architecture | Denoising network core | 8 layers, 8 attention heads, 512 embedding dimensions |

| Variance Scheduler | Controls noise progression | Linear schedules from 0.0001 to 0.02 over 1000 steps |

| Group Relative Policy Optimization | Reinforcement learning integration | Risk-seeking policy gradients for expression selection |

| Feature Encoder | Processes input data | PointNet-style with convolutional layers |

| Expression Simplification | Reduces model complexity | Boolean simplification, operator restrictions |

Diffusion-based approaches represent a promising frontier in symbolic regression, offering distinct advantages in generation diversity and global context utilization. Current experimental results demonstrate that methods like DDSR and Symbolic Diffusion achieve comparable or superior performance to autoregressive baselines in accuracy metrics while generating simpler, more interpretable expressions [1] [20].

The integration of reinforcement learning with diffusion processes, particularly through methods like token-wise GRPO and risk-seeking strategies, provides a robust framework for balancing exploration and exploitation in the mathematical expression space [1]. Future research directions include developing more efficient deterministic denoising algorithms for discrete spaces [23], scaling to more complex multivariate problems, and improving constant optimization in generated expressions [20].

As these methods mature, they hold significant potential for scientific discovery across domains, including drug development and materials science, where interpretable mathematical relationships derived from data can accelerate research and innovation [2] [5].

From Theory to Practice: Implementing Diffusion-Based SR in Biomedicine

Discrete denoising diffusion and mask-based generation represent a class of generative models that operate directly on discrete data, such as text, tokens, or categorical variables. Unlike continuous diffusion models that operate in pixel or latent space, these architectures are natively designed for discrete state spaces, making them particularly suitable for applications in symbolic regression, text generation, and biological sequence design where data is inherently categorical [23] [24]. The core innovation lies in formulating the forward noising process as a discrete Markov chain with structured transition matrices and learning a reverse process that iteratively denoises the data [24]. This guide provides a comprehensive technical comparison of these architectures, their performance against alternative approaches, and detailed experimental protocols for researchers in scientific fields, particularly drug development.

Architectural Frameworks and Mechanisms

Core Mathematical Foundations

Discrete Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Models (D3PMs) establish a formal framework for discrete diffusion by defining a Markov chain over categorical states via parameterized transition matrices [24]. The forward noising process is specified as:

q(x_t | x_{t-1}) = Cat(x_t; Q_t x_{t-1})

where x_{t-1} is a one-hot vector and Q_t is the Markov transition matrix at timestep t [24]. The design of Q_t enables different noising strategies:

- Uniform (Multinomial) Diffusion:

Q_t = (1-β_t)I + (β_t/K)11^T[24] - Absorbing State Diffusion:

Q_t = (1-β_t)I + β_t x_mask 1^T[24] - Discretized Gaussian: Off-diagonal entries

[Q_t]_{ij} ∠exp(-c|i-j|^2)for ordinal data [24]

The reverse denoising process is trained to approximate p_θ(x_{t-1} | x_t) by predicting clean data x_0 from noisy observations x_t using a parameterized model [24].

Mask-Based Diffusion Architectures

Mask-based diffusion models represent a specialized implementation where the "noise" is the progressive masking of tokens. In standard masked diffusion models (MDM), each token exists in a binary state—either masked or unmasked [25]. Recent innovations have addressed computational inefficiencies in this approach:

- Partial Masking Scheme (Prime): Augments MDM by allowing tokens to occupy intermediate states interpolated between masked and unmasked states. This is achieved by representing each token as a sequence of sub-tokens using base-

mencoding, enabling finer-grained denoising and reducing redundant computations where sequences remain unchanged between sampling steps [25]. - Discrete Diffusion with Planned Denoising (DDPD): Separates the generation process into two specialized models: a planner that identifies which corrupted positions should be denoised next, and a denoiser that corrects them. This plan-and-denoise approach enables more efficient reconstruction during generation [26].

- Deterministic Discrete Denoising: Derandomizes the reverse process using a variant of the herding algorithm with weakly chaotic dynamics, introducing deterministic discrete state transitions without requiring retraining or continuous state embeddings [23].

The following diagram illustrates the core workflow of a generalized discrete diffusion process, incorporating both stochastic and deterministic elements:

Training Objectives and Parameterizations

D3PMs are trained by maximizing a variational lower bound (ELBO) combined with auxiliary denoising losses [24]:

An auxiliary cross-entropy loss, analogous to the BERT objective, is often added [24]:

The "x_0-parameterization" aligns the ELBO and denoising losses by training the model to predict clean data given noised observations [24].

Performance Comparison and Experimental Data

Quantitative Benchmarks Across Modalities

Table 1: Performance comparison across data modalities

| Domain | Dataset | Model | Performance Metrics | Competitive Alternatives |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Language | OpenWebText | MDM-Prime [25] | Perplexity: 15.36 | ARM (17.54), Standard MDM (21.52) |

| Language | WikiText-103 | D3PM [24] | BPT: 5.72 | AR Models (mean BPT: 4.59) |

| Images | CIFAR-10 | MDM-Prime [25] | FID: 3.26 | Leading Continuous Models (Competitive) |

| Images | ImageNet-32 | MDM-Prime [25] | FID: 6.98 | Leading Continuous Models (Competitive) |

| Images | CIFAR-10 | D3PM (Gaussian) [24] | FID: ~7.3, NLL: ~3.4 | Continuous DDPMs (Approaching) |

| Scientific | CATH 4.3 (Proteins) | MapDiff [27] | High recovery rate, low perplexity | State-of-the-art baselines (Outperformed) |

Comparison with Alternative Generative Architectures

Table 2: Architectural comparison with continuous diffusion and other generative models

| Aspect | Discrete Denoising Diffusion | Continuous Diffusion | Autoregressive Models | GANs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data Type | Native discrete data | Continuous representations | Sequential discrete data | Continuous or discrete |

| Training Stability | Stable and predictable [25] | Stable [28] | Stable [28] | Unstable, prone to collapse [28] |

| Inference Speed | Moderate (multiple steps) [24] | Slow (multiple denoising steps) [28] | Fast (single pass) | Very fast (single forward pass) [28] |

| Output Diversity | High diversity [25] | High diversity [28] | Limited by sequence order | Risk of mode collapse [28] |

| Conditioning Flexibility | Highly flexible (text, structure) [27] | Highly flexible [28] | Limited to sequential conditioning | Less flexible [28] |

| Bidirectional Context | Full bidirectional attention [24] | Bidirectional [28] | Left-to-right only | Single pass |

| Key Applications | Text, symbolic music, proteins [24] [27] | Creative industries, advertising [28] | Language modeling | Real-time generation, super-resolution [28] |

Advantages Over Alternative Approaches

Discrete denoising diffusion models demonstrate several distinct advantages for scientific applications:

Non-Autoregressive Parallel Generation: Unlike autoregressive models that factorize distributions according to a prespecified order, discrete diffusion models enable parallel decoding and bidirectional context utilization [25] [24]. This is particularly valuable for tasks like protein sequence design where long-range dependencies exist throughout the sequence [27].

Explicit Uncertainty Modeling: The iterative denoising process naturally accommodates uncertainty estimation, which is crucial for scientific applications. Methods like MapDiff combine DDIM with Monte-Carlo dropout to reduce uncertainty in predictions [27].

Structural Conditioning: For inverse protein folding, MapDiff demonstrates effective conditioning on 3D protein backbone structures using graph-based denoising networks, accurately capturing structure-to-sequence mapping [27].

Computational Efficiency: While standard MDMs suffer from redundant computations where sequences remain unchanged between steps (37% of steps in one analysis), improved methods like Prime reduce idle steps through partial masking [25].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Model Training and Evaluation Framework

Training Protocol for D3PMs [24]:

- Forward Process Setup: Define Markov transition matrices

{Q_t}based on data modality (absorbing for mask-based, discretized Gaussian for ordinal data) - Loss Computation: Combine variational lower bound (ELBO) with auxiliary cross-entropy loss

- Parameter Optimization: Train model to predict clean data

x_0from noised observationsx_t("x_0-parameterization") - Schedule Sampling: Utilize noise schedules that balance training stability and final performance

- Initialization: Sample

x_Tfrom stationary distribution of forward process - Iterative Denoising: For

t = Tto1, computep_θ(x_{t-1} | x_t)using trained model - Sampling: Draw

x_{t-1} ~ p_θ(x_{t-1} | x_t)(stochastic) or use deterministic decoding (e.g., herding, planned denoising) - Termination: Output

x_0as generated sample

Specialized Methodologies for Scientific Applications

For protein inverse folding with MapDiff [27]:

- Data Representation: Represent protein structures as graphs with nodes (residues) and edges (spatial relationships)

- Mask-Prior Pretraining: Pretrain mask prior using invariant point attention (IPA) network with masked language modeling

- Denoising Network: Implement two-step denoising with structure-based sequence predictor (EGNN) and masked sequence designer

- Uncertainty Reduction: Incorporate Monte-Carlo dropout during inference with multiple stochastic forward passes

- Evaluation: Assess sequence recovery (perplexity, recovery rate, NSSR) and foldability (pLDDT, PAE, TM-score) using AlphaFold2 refolding

The experimental workflow for protein design applications illustrates the integration of discrete diffusion with domain-specific scientific knowledge:

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential research tools for discrete diffusion research

| Resource Category | Specific Tool/Model | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Framework Implementations | D3PM Codebase [24] | Reference implementation of discrete diffusion | General discrete data generation |

| Architectural Variants | MDM-Prime [25] | Partial masking for efficient generation | Text and image generation |

| Architectural Variants | DDPD [26] | Planned denoising with planner-denoiser separation | Language modeling, ImageNet |

| Architectural Variants | Deterministic Denoising [23] | Herding-based derandomization | Text and image generation |

| Specialized Applications | MapDiff [27] | Mask-prior-guided diffusion for proteins | Inverse protein folding |

| Evaluation Metrics | Perplexity, FID, Recovery Rate [25] [27] | Quantitative performance assessment | Model comparison and validation |

| Acceleration Tools | DDIM [27] | Accelerated sampling by skipping steps | Faster inference during generation |

| Uncertainty Quantification | Monte-Carlo Dropout [27] | Multiple stochastic forward passes | Confidence estimation in predictions |

Discrete denoising diffusion and mask-based generation architectures represent a powerful framework for generating structured discrete data, with demonstrated success across text, images, and scientific domains like protein design. The key advantages of these approaches include native handling of discrete data, bidirectional context utilization, explicit uncertainty modeling, and flexible conditioning on structural information. Performance benchmarks show these models are competitive with or superior to autoregressive models and continuous diffusion approaches on specific tasks, particularly when leveraging recent innovations like partial masking, planned denoising, and deterministic sampling. For researchers in drug development and scientific fields, these architectures offer promising avenues for inverse design problems where both data structure and uncertainty quantification are critical.

Reinforcement Learning (RL) has emerged as a powerful machine learning paradigm for solving complex sequential decision-making problems across diverse scientific domains. Framed mathematically as a Markov Decision Process (MDP), RL involves an agent learning to maximize cumulative rewards through interactions with an environment [29]. Within this framework, a critical distinction exists between risk-neutral approaches that maximize expected reward and risk-seeking or risk-averse strategies that optimize for different statistical properties of the reward distribution. Risk-seeking policies specifically target metrics like Pass@k (probability of at least one success in k trials) and Max@k (maximum reward across k responses), which are crucial for real-world applications where single-best or any-success outcomes matter more than average performance [30].

The integration of these approaches with symbolic regression and diffusion prediction models creates powerful synergies for scientific applications. Diffusion models generate data by progressively adding noise to training data and then learning to reverse the process, enabling trajectory-level generation in RL that mitigates compounding errors [31]. Meanwhile, symbolic regression provides interpretable mathematical expressions that can enhance policy transparency—a valuable property for scientific domains like drug discovery where understanding mechanism matters alongside performance.

Comparative Analysis of RL Optimization Approaches

Key Algorithmic Frameworks

| Algorithm | Risk Profile | Core Mechanism | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| RSPO [30] | Risk-seeking | Directly optimizes Pass@k/Max@k via closed-form probability estimation | LLM post-training, mathematical reasoning |

| POLO/PGPO [32] | Preference-guided | Dual-level learning from trajectory optimization and turn-level preferences | Molecular optimization, drug discovery |

| Epistemic-Risk-Seeking [33] | Risk-seeking | Epistemic-risk-seeking utility converts uncertainty into value | Efficient exploration, DeepSea environment |

| UDAC [34] | Risk-averse | Diffusion policies with uncertainty-aware distributional critic | Offline RL, safety-critical applications |

| AD-RRL [31] | Risk-averse | Adversarial diffusion with CVaR optimization for robust policies | Robotics, transfer learning with dynamics mismatch |

| CVaR-PPO [31] | Risk-averse | Constrained optimization using Conditional Value at Risk | Safety-critical domains with worst-case concerns |

Performance Comparison Across Domains

Table 1: Performance metrics of risk-seeking vs. risk-averse RL algorithms

| Algorithm | Domain | Key Metric | Performance | Baseline Comparison |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RSPO [30] | Math Reasoning | Pass@k | Consistent outperformance | Superior to risk-neutral baselines with "hitchhiking" issues |

| POLO [32] | Single-property Molecular Optimization | Success Rate | 84% average success rate | 2.3× better than best baseline |

| POLO [32] | Multi-property Molecular Optimization | Success Rate | 50% with only 500 oracle evaluations | State-of-the-art sample efficiency |

| Epistemic-Risk-Seeking [33] | Atari Benchmark | Game Performance | Significant improvements | Better than other efficient exploration techniques |

| Epistemic-Risk-Seeking [33] | DeepSea Environment | Exploration Efficiency | Strong performance | Robust to environment complexity |

| Risk-averse RL [35] | Portfolio Optimization | Risk Reduction | 18% lower risk | Effective for risk-averse investors |

| PPO [36] | Autonomous Vessel Navigation | Robustness | Superior generalization | Maintains performance with domain gaps |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Risk-Seeking Policy Optimization (RSPO) Framework

RSPO addresses the fundamental mismatch between risk-neutral training objectives and risk-seeking evaluation metrics prevalent in Large Language Model (LLM) evaluation. The algorithm employs a novel gradient estimator for Pass@k that eliminates the "hitchhiking" problem, where low-reward responses are inadvertently reinforced when they co-occur with high-reward responses within a sample of k generations [30].

The experimental protocol for RSPO validation involves:

- Environment Setup: Mathematical reasoning tasks with binary reward signals

- Policy Parameterization: Transformer-based language models as policy networks

- Training Regimen: Comparison against risk-neutral policy gradient baselines

- Evaluation Metrics: Pass@k (for k=1, 2, 5, 10) and Max@k across held-out problem sets

- Ablation Studies: Isolating the contribution of the risk-seeking gradient weights

The key innovation lies in the derived gradient for Pass@k with binary rewards: [ \nabla\theta J{\text{Pass}@k}(\theta) = \mathbb{E}{x\sim\mathcal{D}, y\sim\pi\theta(y|x)}[k(1-w\theta)^{k-1}R(x,y)\nabla\theta\log\pi\theta(y|x)] ] where (w\theta) represents the probability of generating a correct response [30].

POLO: Preference-Guided Multi-Turn Reinforcement Learning

The POLO framework addresses sample efficiency challenges in molecular optimization through a multi-turn MDP formulation that treats lead optimization as an iterative conversation. The experimental methodology encompasses [32]:

- Environment: Molecular property oracles (e.g., binding affinity, solubility) with Tanimoto similarity constraints

- State Representation: Complete conversational context including task instructions, molecular history, and oracle evaluations

- Action Space: Structured LLM outputs with reasoning blocks and SMILES string generation

- Reward Design: Combination of property improvements and similarity constraints

- Training Algorithm: Preference-Guided Policy Optimization (PGPO) with dual-level learning

The PGPO algorithm extracts learning signals at two complementary levels:

- Trajectory-level optimization: Reinforces successful optimization strategies

- Turn-level preference learning: Ranks intermediate molecules to provide dense comparative feedback

Experiments conducted across diverse molecular optimization tasks demonstrate POLO's sample efficiency, achieving high success rates with only 500 oracle evaluations—significantly advancing the state-of-the-art in sample-efficient molecular optimization [32].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential research reagents and computational tools for RL in scientific domains

| Tool/Reagent | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Property Oracles [32] | Black-box functions evaluating molecular properties | Lead optimization in drug discovery |

| Tanimoto Similarity [32] | Structural similarity metric between molecules | Constraining molecular exploration |

| Bayesian Neural Networks [35] | Capturing epistemic uncertainty in value estimation | Risk-averse portfolio optimization |

| Diffusion Models [34] [31] | Modeling complex behavior policies and dynamics | Offline RL, trajectory generation |

| Advantage Actor-Critic (A2C) [31] | Policy optimization with value function baseline | Robust reinforcement learning |

| Conditional Value at Risk (CVaR) [31] | Risk measure focusing on tail outcomes | Robust policy optimization |

| Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) [36] | Policy gradient with clipped updates | Autonomous vessel navigation |

| Transformer Architectures [30] | Sequence modeling and policy parameterization | LLM fine-tuning and optimization |

| TCO-NHS Ester (axial) | TCO-NHS Ester (axial), MF:C13H17NO5, MW:267.28 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| FmocNH-PEG4-t-butyl ester | FmocNH-PEG4-t-butyl ester, MF:C30H41NO8, MW:543.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Integration with Symbolic Regression and Diffusion Prediction

The intersection of reinforcement learning with symbolic regression and diffusion models creates powerful frameworks for scientific prediction tasks. Diffusion models address key limitations in model-based RL by generating full trajectories "all at once," thereby mitigating compounding errors typical of autoregressive transition models [31]. When conditioned appropriately, diffusion models can sample from specific distributions, making them particularly suitable for risk-sensitive applications.

Symbolic regression complements these approaches by providing interpretable mathematical representations of learned policies or value functions. In the context of risk-seeking optimization, symbolic expressions can help elucidate the conditions under which risky policies yield benefits, creating opportunities for human-in-the-loop refinement and scientific insight generation.

The AD-RRL algorithm exemplifies this integration, combining diffusion-based trajectory generation with CVaR optimization to produce robust policies [31]. Empirical results across standard benchmarks demonstrate that this hybrid approach achieves superior robustness and performance compared to existing robust RL methods, particularly in transfer scenarios involving variations in physics parameters.

Risk-seeking policy optimization represents a paradigm shift in reinforcement learning for scientific applications where maximum performance or any-success metrics matter more than average performance. The comparative analysis presented in this guide demonstrates that approaches like RSPO and POLO consistently outperform risk-neutral baselines in their respective domains, while risk-averse methods provide necessary safety guarantees for critical applications.

Future research directions include:

- Unified Risk-Aware Frameworks: Developing algorithms that can seamlessly transition between risk-seeking and risk-averse behaviors based on context

- Symbolic Policy Extraction: Integrating symbolic regression with deep RL to produce interpretable policies without sacrificing performance

- Diffusion-Based World Models: Expanding the use of diffusion models for uncertainty-aware environment dynamics prediction

- Cross-Domain Transfer: Applying risk-seeking optimization principles across scientific domains from drug discovery to robotics

As these methodologies continue to mature, their integration with symbolic regression and diffusion prediction will likely yield increasingly powerful tools for scientific discovery and optimization, particularly in high-stakes domains like pharmaceutical development where both performance and interpretability are paramount.

This guide objectively compares the performance of various computational models used to predict the binding of small molecule drugs to human liver microsomes (HLM), a critical parameter in predicting metabolic stability. The analysis is framed within the broader thesis that symbolic regression offers a powerful middle ground in predictive modeling, balancing the interpretability of traditional methods with the high accuracy of complex machine learning.

Model Performance Comparison

The table below summarizes the key performance metrics and characteristics of different modeling approaches for HLM binding prediction.

| Model Type | Model Name | Key Features | Performance Metrics | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symbolic Regression [37] | Not Specified | Derives simple, interpretable equations from data. | Validated on in-house and external test sets; improved performance over lipophilicity-based models. [37] | Easily implementable equations; superior to simple models without complex ML's data needs. [37] | Performance is a "middle ground"; may not match top-tier deep learning models. |

| Graph Neural Network (GNN) [38] | MetaboGNN | Uses graph contrastive learning (GCL); incorporates interspecies differences. | RMSE: 27.91 (HLM) and 27.86 (MLM) for metabolic stability. [38] | State-of-the-art predictive performance; provides structural insights via attention mechanisms. [38] | High complexity; requires substantial, high-quality data for training. |

| Traditional Machine Learning [39] | Various (e.g., Random Forest) | Includes QSAR and other classic ML algorithms. | Specific metrics for HLM not provided; widely assessed for DMPK properties. [39] | Well-established; can be effective for specific endpoints with curated datasets. [39] | Performance can be limited by feature engineering and data heterogeneity. |

| Simple Lipophilicity-Based [37] | Not Specified | Relies primarily on logP or other lipophilicity measures. | Moderate performance. [37] | High interpretability; simple to implement and compute. | Limited predictive accuracy due to oversimplification. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Symbolic Regression Methodology

Symbolic regression was applied to a medium-sized, proprietary dataset of experimental fraction unbound in HLM (fu,mic) measurements. [37] The protocol involves:

- Data Preparation: An in-house dataset is split into training and held-out test sets. An external validation set is used for final model verification. [37]

- Model Training: The symbolic regression algorithm explores a space of mathematical expressions to identify equations that best fit the training data. The goal is to minimize prediction error while balancing model complexity. [37]

- Output: The process yields one or more novel, easily implementable equations that describe the relationship between molecular descriptors and fu,mic. [37]

MetaboGNN (GNN) Methodology

MetaboGNN was developed using a high-quality dataset from the 2023 South Korea Data Challenge for Drug Discovery. [38]

- Data: The dataset comprises 3,498 training and 483 test molecules, with metabolic stability values (percentage of parent compound remaining after 30-minute incubation) for both HLM and Mouse Liver Microsomes (MLM). [38]

- Model Architecture:

- Input: Molecular structures are represented as graphs, where atoms are nodes and bonds are edges. [38]

- Pretraining: Graph Contrastive Learning (GCL) is employed to learn robust, transferable graph-level representations in a self-supervised manner, enhancing generalizability. [38]

- Multi-Task Learning: The model is trained to predict HLM and MLM stability simultaneously, explicitly incorporating interspecies differences as a learning target to boost accuracy. [38]

- Interpretation: An attention mechanism identifies molecular fragments (substructures) that strongly influence metabolic stability. [38]

- Evaluation: Predictive performance is evaluated using Root Mean Square Error (RMSE). [38]

Workflow and Pathway Diagrams

Symbolic Regression for HLM Binding Prediction

MetaboGNN Experimental Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists key resources and their applications in developing and validating HLM binding prediction models.

| Tool / Resource | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Human Liver Microsomes (HLM) | In vitro system containing drug-metabolizing enzymes (e.g., CYPs); used to generate experimental fu,mic data for model training and validation. [37] |

| Liquid Chromatography with Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) | Analytical technique used to quantitatively measure the concentration of a parent compound remaining after incubation with HLM, providing the metabolic stability endpoint. [38] |

| Graph Neural Network (GNN) Frameworks | Software libraries (e.g., PyTorch Geometric, DGL) used to build models like MetaboGNN that learn directly from molecular graph structures. [38] |

| Symbolic Regression Platforms | Specialized software or code that automatically searches for mathematical expressions that best fit a given dataset, enabling the discovery of interpretable models. [37] |

| AssayInspector | A computational tool for data consistency assessment, which helps identify outliers, batch effects, and distributional misalignments across different ADME datasets before model training. [40] |

| 3,9-Dimethyl-3,9-diazaspiro[5.5]undecane | 3,9-Dimethyl-3,9-diazaspiro[5.5]undecane |

| 10,11-Dihydro-24-hydroxyaflavinine | 10,11-Dihydro-24-hydroxyaflavinine, MF:C28H41NO2, MW:423.6 g/mol |

Interpretable clinical prediction models are revolutionizing the use of Electronic Health Records (EHRs) in healthcare research and drug development. By transforming complex patient data into transparent, actionable insights, these models are pivotal for supporting high-stakes clinical decisions. This guide explores and compares the leading interpretable machine learning approaches, with a special focus on the emerging role of symbolic regression within the broader context of symbolic regression machine learning diffusion prediction research.

The adoption of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in healthcare, particularly for clinical decision support systems (CDSSs), has significantly enhanced diagnostic precision, risk stratification, and treatment planning [41]. However, the "black-box" nature of many sophisticated AI models remains a significant barrier to clinical adoption [41]. In high-stakes domains like medicine, clinicians must understand and trust a model's recommendations to ensure patient safety. This has spurred the critical need for Explainable AI (XAI), a subfield dedicated to creating models with behavior and predictions that are understandable and trustworthy to human users [41].

EHR data, with its mix of structured information and unstructured clinical notes, provides a rich but challenging source for prediction models. A recent systematic review highlighted that while many AI-based diagnostic prediction models have been developed using EHRs, most suffer from a high risk of bias and are not yet ready for clinical implementation, partly due to a lack of transparency and insufficient model testing in real-world primary care settings [42]. Therefore, the development of accurate and interpretable models is not merely an academic exercise but a fundamental requirement for safe and effective integration of AI into clinical workflows and pharmaceutical research.

Comparative Analysis of Interpretable Modeling Approaches

We objectively compare four prominent methodological approaches for building interpretable clinical prediction models from EHR data. The table below summarizes their core principles, strengths, and limitations, providing a foundation for researchers to select the most appropriate technique for their specific use case.

Table 1: Comparison of Interpretable Modeling Approaches for EHR Data

| Modeling Approach | Core Interpretability Principle | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Symbolic Regression (e.g., FEAT) | Discovers concise, closed-form mathematical equations from data [43]. | • High intuitiveness: Models are inherently transparent and human-readable [43].• Balanced performance: Can achieve accuracy comparable to black-box models while being significantly smaller [43]. | • Computational demand: Search space for optimal expressions can be vast and complex. |

| Interpretable ML with Post-hoc XAI (e.g., SHAP/LIME) | Uses model-agnostic techniques to explain predictions of any underlying model [44] [45]. | • Flexibility: Can be applied to any black-box model (e.g., XGBoost, Neural Networks) [41].• Rich insights: Provides both global and local feature importance rankings [45]. | • Explanation approximation: Explanations are approximations, not true representations of the model's internal logic [41]. |

| Deep Learning with Integrated Interpretability | Incorporates interpretable structures, like feature selection, directly into the model architecture [46]. | • Representation learning: Automatically learns features from complex data.• Built-in transparency: Frameworks like DeepSelective enhance interpretability without sacrificing the power of deep learning [46]. | • Residual complexity: Despite simplification, models may still be less intuitive than simple equations. |

| Traditional Statistical Models (Baseline) | Relies on pre-specified, linear or logistic functional forms with inferential statistics [41]. | • Well-understood: Coefficients are easily interpreted and statistically validated.• Theoretical foundation: Strong foundations in causality and confidence intervals. | • Limited expressiveness: Poor performance in capturing complex, non-linear relationships in EHR data [41]. |

Quantitative Performance Benchmarking

To move beyond theoretical comparisons, we present empirical data on the performance of these approaches across various clinical prediction tasks. The following table synthesizes quantitative results reported in recent publications, offering a benchmark for expected performance in terms of discriminative ability and predictive accuracy.

Table 2: Performance Benchmarking Across Clinical Prediction Tasks

| Study & Model | Clinical Prediction Task | Key Performance Metrics | Interpretability Method & Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| FEAT (Symbolic Regression) [43] | Classification of hypertension and apparent treatment-resistant hypertension (aTRH). | • Positive Predictive Value (PPV): 0.70• Sensitivity: 0.62• Model Size: 6 features | Inherent model structure. Generated a concise, clinically intuitive 6-feature model that was 3x smaller than other interpretable models while achieving equivalent or higher discriminative performance (p<0.001). |

| Random Forest + SHAP [44] | Cardiovascular risk stratification. | • Accuracy: 81.3% | SHAP & Partial Dependence Plots (PDP). Provided transparent global and local explanations for feature contributions, ensuring trust in decision-making. |

| XGBoost + SHAP/LIME [45] | Prediction of medical environment comfort. | • Accuracy: 85.2%• Precision: 86.5%• Recall: 92.3%• F1-score: 0.893• ROC-AUC: 0.889 | SHAP & LIME. Identified Air Quality Index (importance: 1.117) and Temperature (importance: 1.065) as the most critical factors, revealing specific impact patterns. |

| DeepSelective [46] | Prognosis prediction using EHR data. | (Reported enhanced predictive accuracy and interpretability, specific metrics not detailed in source). | Feature Selection & Compression. An end-to-end deep learning framework that improved both predictive accuracy and interpretability through integrated feature selection. |

| Clinical-BigBird (DL) [47] | Identifying cancer progression in EHR text (Breast Cancer). | • Sensitivity: 94.3%• PPV: 92.3%• Scaled Brier Score: 0.79 | Influential Token Analysis. Identified influential tokens (e.g., the word "progression") and could remove >84% of charts from manual review, though model itself is less interpretable. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To facilitate replication and validation, this section outlines the standard methodologies employed in developing and evaluating the featured models.

Protocol for Symbolic Regression via FEAT

The application of the Feature Engineering Automation Tool (FEAT) to train interpretable models for classifying hypertension phenotypes exemplifies a robust protocol [43]:

- Data Sourcing: Utilize EHR data from a large healthcare system. For the cited study, data from 1200 subjects receiving longitudinal care was used [43].

- Phenotype Adjudication: Establish ground truth labels through a rigorous chart review process conducted by clinical experts [43].

- Model Training and Benchmarking:

- Train FEAT to discover mathematical expressions that map patient data to the adjudicated phenotypes.

- Benchmark FEAT's performance against other interpretable models (e.g., penalized linear models, decision trees) on metrics of discriminative performance and model complexity (size) [43].

- Validation: Perform empirical testing to demonstrate that FEAT models achieve equivalent or superior performance with significantly smaller and more intuitive structures [43].

Protocol for Interpretable ML with SHAP/XGBoost

A common protocol for cardiovascular risk stratification, as detailed in one of the benchmarked studies, involves [44]:

- Data Preprocessing: Address missing data in EHRs using imputation strategies like K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) to ensure robust model training [44].

- Model Selection and Training: Benchmark multiple machine learning classifiers (e.g., Random Forest, XGBoost, SVM) to identify the best-performing algorithm for the specific prediction task [44].

- Interpretability Analysis:

- Apply SHAP to the trained model to calculate feature importance values, providing a global view of which variables most significantly impact the prediction.

- Use Partial Dependence Plots (PDP) to visualize the relationship between key features and the predicted outcome [44].

- Clinical Integration: Develop a user-friendly graphical interface (e.g., using Streamlit) to facilitate real-time risk assessment and deliver feature-level explanations to clinicians [44].

Protocol for Deep Learning on Unstructured EHR Text

For tasks like identifying cancer progression from clinical notes, the protocol leverages advanced NLP models [47]:

- Cohort Definition and Labeling: Identify a patient cohort from a cancer registry (e.g., stage 4 breast or colorectal cancer). Trained research assistants then perform chart reviews to assign labels (e.g., "cancer progression," "mention of progression," "no mention") to each EHR note [47].

- Text Preprocessing: Clean the clinical text by converting it to lowercase, removing very long words, and excising section headers that could be confused with the outcome (e.g., "PROGRESS NOTE") [47].

- Model Fine-Tuning: Utilize pre-trained deep learning language models (e.g., Clinical-BigBird, Clinical-Longformer) capable of handling long text sequences. Fine-tune these models on the training dataset using cross-validation, optimizing parameters like batch size and learning rate [47].

- Performance Evaluation and Explanation:

- Evaluate models on a held-out test set using sensitivity, PPV, and scaled Brier scores.

- Perform influential token analysis by perturbing the input text (removing/adding tokens) to observe changes in predicted probabilities, thereby identifying words that most influence the model's decision [47].