Finite-Size Effects Correction in Molecular Dynamics: A Comprehensive Guide to Accurate Diffusion Coefficients

This article provides a systematic examination of finite-size effects on diffusion coefficients computed from molecular dynamics simulations, addressing self-diffusion, Maxwell-Stefan, and Fick diffusion coefficients across pure fluids to multicomponent mixtures.

Finite-Size Effects Correction in Molecular Dynamics: A Comprehensive Guide to Accurate Diffusion Coefficients

Abstract

This article provides a systematic examination of finite-size effects on diffusion coefficients computed from molecular dynamics simulations, addressing self-diffusion, Maxwell-Stefan, and Fick diffusion coefficients across pure fluids to multicomponent mixtures. We explore the foundational hydrodynamic theory behind finite-size corrections, detail methodological implementations including the Yeh-Hummer correction and its extensions, address troubleshooting for challenging systems near demixing or with electrostatic interactions, and present validation case studies from Lennard-Jones systems to molecular mixtures. Special emphasis is placed on implications for biomedical and pharmaceutical research where accurate diffusion predictions are critical for drug delivery systems and biomolecular transport.

Understanding Finite-Size Effects: Why Simulated Diffusion Coefficients Depend on System Size

In molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, the assessment of transport properties, such as diffusion coefficients, is fundamentally constrained by the finite size of the simulation box. This limitation creates a significant discrepancy between computed values from MD and the true properties of a system at the thermodynamic limit (TL), where the number of particles (N) and the system volume (V) approach infinity (N→∞, V→∞, N/V=constant) [1]. For properties dependent on long-wavelength fluctuations and collective molecular motion, such as mutual diffusion, this finite-size effect is particularly pronounced. The core problem is that conventional MD simulations model a finite, closed system (NVT or NVE ensembles) with periodic boundary conditions, which perturbs the long-range hydrodynamic interactions responsible for diffusion phenomena [2]. Consequently, a direct comparison between simulation results and experimental data, or their use in predictive modeling for applications like drug development, requires robust methods to extrapolate finite-size MD results to the thermodynamic limit.

Theoretical Background

Key Diffusion Coefficients and Their Physical Meaning

In MD simulations, several types of diffusion coefficients are analyzed, each with a distinct physical interpretation and method of calculation. Table 1 summarizes these coefficients and their relationships.

Table 1: Types of Diffusion Coefficients in Molecular Dynamics Simulations

| Coefficient Type | Symbol | Definition | Calculation Method (EMD) | Relevance to Finite-Size Effects | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-Diffusion | ( D_{i,self} ) | Measures the translational motion of a single tagged particle i due to its own Brownian motion. | Einstein relation: ( D{i,self} = \lim{t \to \infty} \frac{1}{6t} \langle | \mathbf{r}j(t) - \mathbf{r}j(0) | ^2 \rangle ) [2] | Strong dependency on system size; scales with ( N^{-1/3} ) [2]. |

| Maxwell-Stefan (MS) | ( \Ä_{MS} ) | Describes collective mass transport driven by the gradient in chemical potential. | Based on Onsager coefficients from cross-correlation of molecular displacements [2]. | Stronger finite-size dependency than self-diffusion; also influenced by mixture non-ideality [2]. | ||

| Fick | ( D_{Fick} ) | The coefficient relating mass flux to a concentration gradient (Fick's first law). | Calculated from the MS diffusivity and the thermodynamic factor: ( D{Fick} = \Ä{MS} \times \Gamma ) [2]. | Inherits finite-size effects from ( \Ä_{MS} ). |

The thermodynamic factor (( \Gamma )), which measures the non-ideality of a mixture, is a critical component linking MS and Fick diffusivities. For systems close to demixing, the thermodynamic factor can be large, amplifying the finite-size effects on the computed mutual diffusivities [2].

The Origin of Finite-Size Effects in Diffusion

The finite-size dependency arises from the use of periodic boundary conditions, which alter the hydrodynamic self-interactions of particles. In an infinite system, a particle moving through a fluid creates a flow field that decays with distance. In a finite, periodic system, this flow field interacts with its periodic images, effectively reducing the perceived friction and leading to an overestimation of diffusion coefficients [2]. This effect is universal but is particularly critical for collective diffusion coefficients like the MS diffusivity, where the motion of all molecules is correlated.

Correction Methodologies for the Thermodynamic Limit

The Yeh-Hummer Correction for Self-Diffusion

Yeh and Hummer derived an analytical correction for self-diffusion coefficients based on hydrodynamic theory for a spherical particle in a Stokes flow with periodic boundary conditions [2]. The correction term allows for the extrapolation of the finite-size self-diffusivity (( D{i,self} )) to its value at the thermodynamic limit (( D{i,self}^\infty )).

Equation 1: Yeh-Hummer (YH) Correction for Self-Diffusion [ D{i,self}^\infty = D{i,self} + D{YH} = D{i,self} + \frac{kB T \xi}{6 \pi \eta L} ] Here, ( kB ) is the Boltzmann constant, ( T ) is the temperature, ( \eta ) is the shear viscosity of the system, ( L ) is the box length, and ( \xi ) is a dimensionless constant equal to 2.837297 for cubic boxes [2]. The shear viscosity (( \eta )) itself can be computed from equilibrium MD simulations and is independent of system size, making it a reliable parameter in this correction [2].

Proposed Correction for Maxwell-Stefan Diffusivity

The finite-size effects on MS diffusivities are more complex because they depend not only on box size, temperature, and viscosity but also on the non-ideality of the mixture, captured by the thermodynamic factor. A correction for the MS diffusion coefficient in binary mixtures has been proposed, extending the concepts of the YH correction [2].

Equation 2: Finite-Size Correction for Maxwell-Stefan Diffusivity [ \Ä{MS}^\infty = \Ä{MS} + \frac{kB T \xi}{6 \pi \eta L} \Gamma ] In this equation, ( \Gamma ) is the thermodynamic factor. This relationship indicates that for highly non-ideal mixtures (where ( \Gamma ) is large), the finite-size correction can be substantial—sometimes even larger than the simulated ( \Ä{MS} ) value itself, especially for systems near demixing [2].

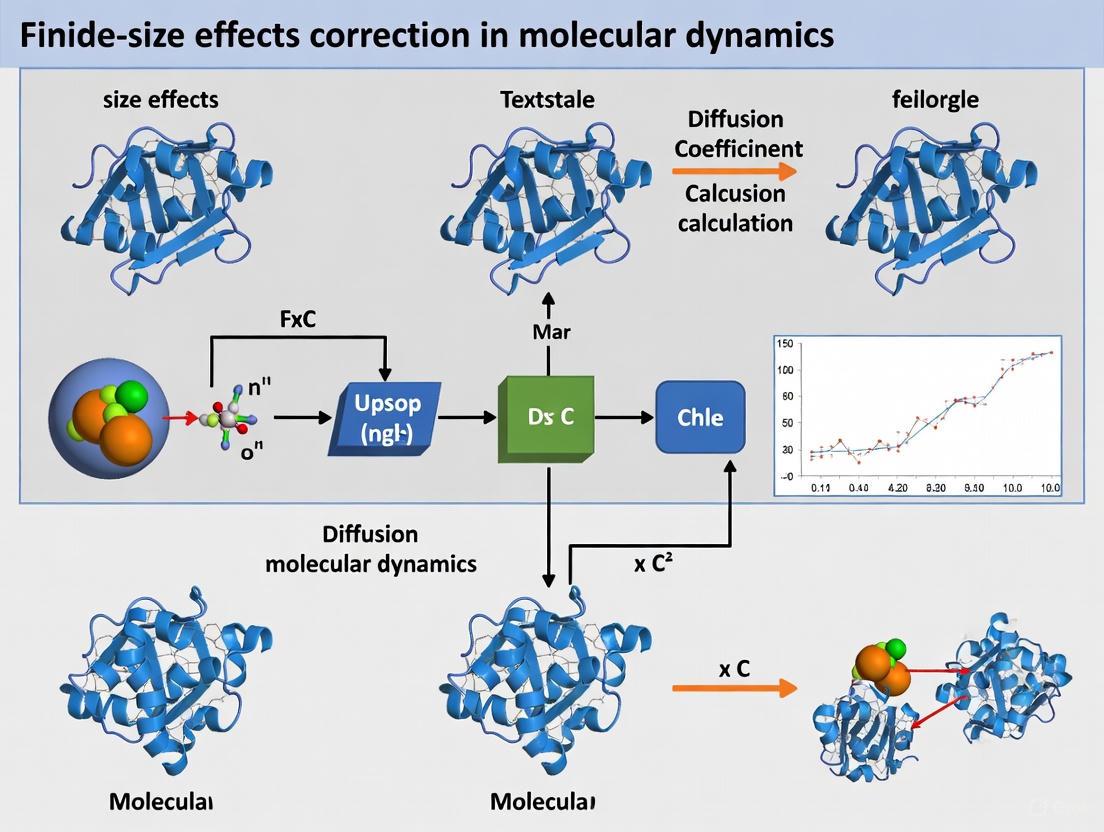

The following workflow diagram illustrates the protocol for applying these corrections, from running the simulation to obtaining the TL-corrected diffusivity.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol A: Calculating and Correcting Self-Diffusion Coefficients

This protocol details the steps for obtaining a self-diffusion coefficient in the thermodynamic limit from an equilibrium MD simulation.

- System Preparation: Construct a simulation box containing N particles of the species of interest, using a validated force field. Apply periodic boundary conditions in all three dimensions. Equilibrate the system thoroughly in the desired ensemble (e.g., NVT) at the target temperature and density.

- Production Simulation: Run a sufficiently long equilibrium MD simulation to ensure good statistics for trajectory analysis. The simulation time should be several times longer than the diffusion relaxation time of the molecules.

- Compute Finite-Size Self-Diffusivity (( D{i,self} )): Use the Einstein relation from the mean-squared displacement (MSD) of the molecules [2]: ( D{i,self} = \lim{t \to \infty} \frac{1}{6t} \langle | \mathbf{r}j(t) - \mathbf{r}j(0) |^2 \rangle ) Ensure the MSD plot is linear in the diffusive regime, and fit the slope to obtain ( D{i,self} ).

- Compute Shear Viscosity (( \eta )): Calculate the shear viscosity from the autocorrelation of the off-diagonal components of the stress tensor (Pαβ) using the Green-Kubo relation [2]: ( \eta = \frac{V}{kB T} \int0^\infty \langle P{\alpha\beta}(t) \cdot P{\alpha\beta}(0) \rangle dt )

- Apply the YH Correction: Using the box length ( L ), temperature ( T ), computed viscosity ( \eta ), and the constant ( \xi = 2.837297 ), calculate the correction term and add it to the simulated ( D{i,self} ) to obtain ( D{i,self}^\infty ) as shown in Equation 1.

Protocol B: Calculating and Correcting Maxwell-Stefan Diffusivities

This protocol extends the methodology to mutual diffusion in binary mixtures.

- System Preparation & Production: Follow Steps 1 and 2 from Protocol A for a binary mixture.

- Compute Finite-Size MS Diffusivity (( \Ä{MS} )): Calculate the Onsager coefficients (Λâ‚â‚, Λ₂₂, Λâ‚â‚‚) from the cross-correlation of the molecular displacements [2]. For a binary mixture, the MS diffusivity is related to the Onsager coefficients by: ( \Ä{MS} = \frac{x2}{x1} \Lambda{11} + \frac{x1}{x2} \Lambda{22} - 2 \Lambda{12} ) where ( x1 ) and ( x_2 ) are the mole fractions of the two components.

- Compute the Thermodynamic Factor (( \Gamma )): Determine the thermodynamic factor, which requires knowledge of the concentration dependence of the chemical potentials. This can be obtained from free energy calculations (e.g., thermodynamic integration) or from a model equation of state fitted to simulation data.

- Apply the MS Correction: Using the same parameters as the YH correction and the computed thermodynamic factor, apply Equation 2 to extrapolate ( \Ä{MS} ) to ( \Ä{MS}^\infty ).

Data Presentation and Analysis

Quantitative Finite-Size Effects and Corrections

The magnitude of finite-size effects and the efficacy of the corrections can be demonstrated by simulating systems of varying sizes. Table 2 presents hypothetical data for a Lennard-Jones system, illustrating how diffusivities converge to the TL value after correction.

Table 2: Exemplary Finite-Size Data and Correction for a Binary Lennard-Jones Mixture (Component A) (T, Ï, and composition held constant across simulations)

| Number of Molecules (N) | Box Length L (σ) | D_self (σ²/Ï„) | D_self∞ (Corrected) (σ²/Ï„) | Ä_MS (σ²/Ï„) | Γ | Ä_MS∞ (Corrected) (σ²/Ï„) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 512 | 8.0 | 0.115 | 0.131 | 0.085 | 2.5 | 0.131 |

| 1000 | 10.0 | 0.121 | 0.130 | 0.095 | 2.5 | 0.128 |

| 4000 | 15.9 | 0.127 | 0.131 | 0.112 | 2.5 | 0.129 |

| 8000 | 20.0 | 0.129 | 0.131 | 0.120 | 2.5 | 0.130 |

| Thermodynamic Limit | ∞ | ~0.131 | ~0.130 |

Note: σ and τ are Lennard-Jones units of length and time. Data is illustrative based on trends described in [2].

The data in Table 2 shows two key trends: 1) both self and MS diffusivities increase with system size, and 2) after applying the respective corrections, the values for different system sizes converge towards a consistent TL value, validating the methodology.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Computational Tools for Finite-Size Correction Studies

| Item / Reagent | Function / Description | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Dynamics Software | Software package to perform the simulations and often basic trajectory analysis. | ESPResSo++ [1], GROMACS, LAMMPS, HOOMD-blue. |

| Validated Force Field | A set of parameters describing the interatomic potentials for the molecules being studied. | Truncated and shifted Lennard-Jones (TSLJ) for prototypical liquids [1]; OPLS-AA, CHARMM, AMBER for molecular systems. |

| Trajectory Analysis Tools | Custom or built-in scripts to compute MSD, stress tensor autocorrelation, and Onsager coefficients. | Python (MDAnalysis, MDTraj), custom C++/Fortran codes. |

| Thermodynamic Property Calculator | Tools to compute chemical potentials and the thermodynamic factor (Γ). | Free energy perturbation (FEP), thermodynamic integration (TI) methods, or equations of state implemented in analysis suites. |

| Post-Processing Scripts | Custom scripts to implement the finite-size correction formulas (Equations 1 & 2). | In-house Python or MATLAB scripts to aggregate data from multiple system sizes and perform the TL extrapolation. |

| Olivetol-d9 | Olivetol-d9, CAS:137125-92-9, MF:C11H16O2, MW:189.30 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| MCPD dioleate | [3-chloro-2-[(Z)-octadec-9-enoyl]oxypropyl] (E)-octadec-9-enoate |

Hydrodynamic Origins of System-Size Dependence in Diffusion

In molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, accurately calculating diffusion coefficients is essential for understanding transport phenomena in materials science and drug development. However, a significant challenge arises from finite-size effects, where the simulated system's inherently small size—often just hundreds or thousands of molecules—distorts the calculated diffusivities compared to the thermodynamic limit (real-world conditions). These effects originate from hydrodynamic self-interactions due to the periodic boundary conditions (PBCs) typically employed in MD simulations [2]. This application note details the hydrodynamic theory underlying these artifacts and provides validated protocols for correcting them, enabling more reliable prediction of diffusion coefficients for applications such as drug candidate screening and material design.

Hydrodynamic Theory of Finite-Size Effects

The primary source of system-size dependence in diffusion coefficients stems from the use of PBCs. In an infinite, unbound system, a particle displacing the solvent experiences a hydrodynamic flow that dissipates infinitely. In a finite simulation box with PBCs, this flow field interacts with its own periodic images, affecting the particle's motion [2].

For self-diffusion coefficients (Dself), which describe the Brownian motion of a single tagged particle, the finite-size effect is quantitatively described by the Yeh-Hummer (YH) correction [2]. The theory, based on the hydrodynamic Stokes flow for a spherical particle, establishes a linear relationship between the computed self-diffusivity and the inverse of the simulation box length: D{self}^{∞} = D{self}(L) + \frac{kB T ξ}{6 π η L} Here, D{self}^{∞} is the corrected self-diffusion coefficient in the thermodynamic limit, D{self}(L) is the value obtained from an MD simulation with a cubic box of side length L, η is the shear viscosity of the system, T is the temperature, and k_B is the Boltzmann constant. The dimensionless constant ξ is 2.837297 for cubic boxes with PBCs [2].

For mutual diffusion coefficients, such as the Maxwell-Stefan (ÄMS) diffusivity, the finite-size effect has an additional dependency on the thermodynamic factor (Γ), which characterizes the non-ideality of the mixture. The proposed correction is [2]: Ä{MS}^{∞} = Ä{MS}(L) + \frac{kB T Γ ξ}{6 Ï€ η L} This formulation indicates that the finite-size effect is amplified in non-ideal mixtures, particularly those near demixing, where the thermodynamic factor can be large [2].

Table 1: Key Parameters in Hydrodynamic Finite-Size Corrections

| Parameter | Symbol | Description | How to Obtain |

|---|---|---|---|

| Box Length | ( L ) | Side length of the cubic simulation box. | Directly from the MD simulation setup. |

| Shear Viscosity | ( η ) | Viscosity of the system. | Calculate from MD using the Green-Kubo relation (eq. 3) [2]. |

| Thermodynamic Factor | ( Γ ) | Measure of mixture non-ideality. | Compute from a CALPHAD thermodynamic assessment or MD simulations [2]. |

| YH Constant | ( ξ ) | Dimensionless constant for PBCs. | 2.837297 for standard cubic boxes [2]. |

Quantitative Assessment of System-Size Dependence

The system-size dependence of diffusion coefficients has been quantified across various systems. For the hard-sphere fluid, molecular dynamics simulations reveal that the self-diffusion coefficient D follows a scaling law with the number of particles N: D = D(∞) - AN^{-α}, where the exponent α is approximately 1/3 at intermediate packing fractions (~0.35). This corresponds to a 1/L scaling, consistent with the YH correction. At high and very low densities, the exponent α deviates from 1/3 [3].

For binary mutual diffusion, the finite-size effect can be substantial. A comprehensive study of over 200 binary Lennard-Jones systems and several molecular mixtures showed that the deviation between finite-size and thermodynamic-limit diffusivities can be very significant for mixtures close to demixing. In these cases, the required correction can even be larger than the simulated (finite-size) Maxwell-Stefan diffusivity itself [2].

Table 2: Empirical Scaling of Self-Diffusion with System Size in Hard-Sphere Fluids [3]

| Packing Fraction Range | Scaling Exponent (α) | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Low Density (< 0.1) | Approaches 1.0 | Due to divergence of mean free path relative to box size. |

| Intermediate (~0.35) | ~0.33 (1/3) | Consistent with hydrodynamic (YH) theory. |

| High Density | ~1.0 | Scaling more closely follows thermodynamic properties. |

Experimental Protocols for Correction

Protocol 1: Correcting Self-Diffusion Coefficients

This protocol outlines the steps to correct self-diffusion coefficients obtained from equilibrium MD simulations for finite-size effects.

Research Reagent Solutions: Table 3: Essential Materials and Tools for Finite-Size Correction

| Item | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| MD Simulation Software | Software package (e.g., GROMACS, LAMMPS, MOE) to perform the dynamics simulations and calculate mean-square displacement [4] [2]. |

| Force Field Parameters | Set of potentials (e.g., Lennard-Jones, MMFF94x) defining interatomic interactions for the system of interest [4] [2]. |

| Thermodynamic Database | CALPHAD-type database for calculating the thermodynamic factor, if required for mutual diffusion [2]. |

| Analysis Scripts | In-house or published scripts (e.g., using IDL, Python) for implementing the YH correction and calculating viscosity [5] [2]. |

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- System Preparation: Construct the simulation box containing N molecules for your system of interest (e.g., a pure solvent or a mixture) using appropriate force fields. Ensure PBCs are applied in all directions [2].

- MD Simulation: Perform an equilibrium MD simulation under the desired thermodynamic conditions (constant NVT or NPT ensemble). Ensure the simulation is long enough for the mean-square displacement (MSD) to reach the diffusive regime [2].

- Calculate D(L): Compute the self-diffusion coefficient D(L) for the finite system using the Einstein relation from the MSD of the molecules (eq. 1) [2].

- Calculate Viscosity: In the same simulation, calculate the shear viscosity η of the system. This is typically done using the Green-Kubo method, which integrates the stress tensor autocorrelation function (eq. 3) [2]. Note that viscosity itself is generally independent of system size [2].

- Apply YH Correction: Using the box length L, viscosity η, and temperature T from your simulation, calculate the correction term and add it to the computed D(L) to obtain D_{self}^{∞} (eq. 2) [2].

- Validation: Repeat steps 1-5 for at least two different system sizes (e.g., N=500 and N=2000). Plot the computed D(L) against 1/L. The data should fall on a straight line, and the y-intercept (1/L -> 0) corresponds to D_{self}^{∞}, providing a model-free validation of the correction [2].

Protocol 2: Correcting Mutual Diffusion Coefficients

This protocol extends the correction to Maxwell-Stefan diffusion coefficients in binary mixtures.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- MD Simulation: Perform an equilibrium MD simulation of the binary mixture at the desired composition and temperature [2].

- Calculate Onsager Coefficients: From the particle trajectories, compute the Onsager coefficients Λ_ij using the Einstein relation based on the cross-correlations of molecular displacements (eq. 4) [2].

- Compute Finite-Size ÄMS: Obtain the finite-size Maxwell-Stefan diffusivity ÄMS(L) from the Onsager coefficients and the mixture composition [2].

- Determine Thermodynamic Factor: Calculate the thermodynamic factor Γ for the mixture. This can be derived from a CALPHAD thermodynamic database or computed directly from the MD simulation via fluctuation theory [2].

- Apply Mutual Diffusion Correction: Calculate the corrected mutual diffusion coefficient in the thermodynamic limit using the formula that incorporates the thermodynamic factor: Ä{MS}^{∞} = Ä{MS}(L) + (k_B T Γ ξ) / (6 Ï€ η L) [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 4: Key Reagents and Computational Tools for Diffusion Studies

| Category | Specific Tool/Method | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Simulation Methods | Equilibrium MD (EMD) | Compute diffusion coefficients from particle trajectories at equilibrium [2]. |

| Einstein Formulation | Calculate diffusivities from the slope of the mean-square displacement (MSD) vs. time [2]. | |

| Analysis Tools | HYDROPRO | Calculate hydrodynamic properties (e.g., Rh) from atomistic structures; accurate but computationally intensive [6]. |

| Kirkwood-Riseman Equation | An efficient and accurate method for calculating the hydrodynamic radius from atomic coordinates [7]. | |

| Physical Models | Stokes-Einstein Equation | Relates diffusion coefficient (D) to hydrodynamic radius (Rh): D = kBT / (6πηRh) [4] [6]. |

| Radius of Gyration (Rg) | A measure of molecular size that can be efficiently calculated from ensembles of conformations [6]. | |

| Experimental Validation | Pulsed-Field Gradient (PFG) NMR | Measures translational diffusion coefficients in solution, providing experimental Rh for validation [6] [7]. |

| Small-Angle X-Ray Scattering (SAXS) | Probes the radius of gyration (Rg) of proteins in solution, offering complementary structural data [6]. | |

| Phenazopyridine | Phenazopyridine, CAS:94-78-0, MF:C11H11N5, MW:213.24 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Raloxifene N-oxide | Raloxifene N-oxide, CAS:195454-31-0, MF:C28H27NO5S, MW:489.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Theoretical Foundations and Definitions

Understanding the distinct mechanisms of molecular transport is fundamental to accurately modeling and predicting the behavior of fluids in various scientific and industrial contexts. Self-diffusion and mutual diffusion describe different physical phenomena governed by separate driving forces and mathematical formalisms. Self-diffusion refers to the random Brownian motion of a single molecule within a fluid of identical molecules, tracing the trajectory of an individual particle over time [8]. In contrast, mutual diffusion (also called inter-diffusion or collective diffusion) describes the mass transport process where different chemical species intermingle and move down their concentration gradients [9] [10]. This fundamental distinction in physical mechanism leads to significant differences in how these coefficients are defined, measured, and applied across scientific disciplines.

The mathematical description of these processes further highlights their differences. Self-diffusion is characterized by the self-diffusion coefficient (D*), which quantifies the mean-squared displacement of tagged molecules over time. Mutual diffusion in a binary system is described by Fick's first law, where the flux of a component is proportional to its concentration gradient, with the proportionality constant being the mutual diffusion coefficient (D) [9]. For multicomponent systems, this relationship extends to a matrix of Fick diffusion coefficients [11]. A critical theoretical relationship exists at infinite dilution, where the mutual diffusion coefficient equals the self-diffusion coefficient of the infinitely diluted solute [8]. However, at finite concentrations, these values diverge significantly due to intermolecular interactions.

Comparative Analysis: Key Physical Differences

The differential response of self-diffusion and mutual diffusion to intermolecular forces represents one of their most distinguishing characteristics. As demonstrated in membrane systems, interprotein interactions produce markedly different density-dependent changes in these coefficients [12]. Self-diffusion is consistently inhibited by all types of interactions—hard-core repulsions, soft repulsions, and soft repulsions with weak attractions [12]. In contrast, mutual diffusion exhibits a more complex response: it is inhibited by attractive interactions but enhanced by repulsive forces [12]. This fundamental difference arises because self-diffusion depends solely on molecular mobility, while mutual diffusion incorporates both mobility and thermodynamic driving forces.

The conceptual frameworks for these diffusion processes also differ substantially. Self-diffusion can be visualized as the "tracer" motion of a tagged molecule within a homogeneous medium, whereas mutual diffusion describes the macroscopic flux resulting from concentration inhomogeneities. This distinction becomes particularly important in applications such as drug development, where both the passive mobility of a drug molecule (self-diffusion) and its transport across concentration gradients (mutual diffusion) play critical roles in delivery efficacy. The different responses to interactions help explain why disparate values for protein diffusion coefficients are obtained from different experimental techniques such as fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (measuring self-diffusion) and postelectrophoresis relaxation (measuring mutual diffusion) [12].

Table 1: Fundamental Differences Between Self-Diffusion and Mutual Diffusion

| Characteristic | Self-Diffusion | Mutual Diffusion |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Motion of tagged particles in a uniform chemical potential | Net transport of different species down concentration gradients |

| Driving Force | Thermal energy (Brownian motion) | Chemical potential gradient |

| System Composition | Single-component or uniform mixture | Multi-component system with composition variations |

| Response to Repulsive Interactions | Always decreased | Enhanced |

| Response to Attractive Interactions | Decreased | Inhibited |

| Experimental Techniques | NMR, FRAP, tracer diffusion | Optical interference, Taylor dispersion, diaphragm cell |

Quantitative Relationships and Mathematical Formalism

The mathematical description of diffusion processes reveals the intricate relationships between different diffusion coefficients. For binary mixtures, the Darken equation provides a fundamental relationship connecting mutual and self-diffusion coefficients:

D = (xâ‚‚Dâ‚* + xâ‚Dâ‚‚*)Γ

where D is the mutual diffusion coefficient, Dâ‚* and Dâ‚‚* are the self-diffusion coefficients of components 1 and 2, xâ‚ and xâ‚‚ are their mole fractions, and Γ is the thermodynamic factor [10]. The thermodynamic factor, defined as Γ = 1 + (∂lnγ/∂lnx), where γ is the activity coefficient, accounts for non-ideal mixing behavior [10]. In ideal solutions where components mix randomly, Γ = 1, simplifying the relationship between diffusion coefficients.

The Maxwell-Stefan formulation provides an alternative framework that relates Fick diffusivities (DFick) to Maxwell-Stefan diffusivities (ÄMS) through the matrix of thermodynamic factors [Γ]: [DFick] = [Γ][ÄMS] [11]. This relationship becomes particularly important when describing diffusion in multicomponent systems, where cross-interactions between multiple species must be considered. The matrix of Fick diffusivities contains (n-1)² elements for an n-component mixture, while n·(n-1)/2 Maxwell-Stefan diffusion coefficients are defined [11].

Table 2: Classification of Diffusion Coefficient Types and Their Characteristics

| Diffusion Coefficient Type | Symbol | Definition | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Self-Diffusion | D* | Mobility of a species in itself (no net transport) | Studying molecular mobility in pure substances |

| Mutual Diffusion | D_AB | Diffusion of one constituent in a binary system | Mass transfer calculations in chemical processes |

| Tracer Diffusion | D_A'B | Diffusion of a tagged isotope in a mixture | Tracking specific molecules without chemical potential gradient |

| Intrinsic Diffusion | D_A | Diffusion flux relative to container-fixed coordinates | Systems with significant molecular size disparities |

Finite-Size Effects in Molecular Dynamics Simulations

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations provide powerful tools for computing diffusion coefficients, but the finite size of simulation boxes introduces systematic errors that must be corrected. Self-diffusion coefficients computed from equilibrium MD (Di,self^MD) exhibit a well-characterized system-size dependency, scaling linearly with the inverse of the simulation box length (L) [11]. The Yeh-Hummer (YH) correction provides an analytical finite-size correction for self-diffusivity: Di,self^∞ = Di,self^MD + (kBTξ)/(6πηL), where Di,self^∞ is the self-diffusivity in the thermodynamic limit, kB is Boltzmann's constant, T is temperature, η is shear viscosity, and ξ is a constant dependent on simulation box shape (ξ = 2.837297 for cubic boxes) [11].

For mutual diffusion coefficients, finite-size effects manifest differently. Recent research has established that only the diagonal elements of the Fick matrix show system-size dependency, correctable by adding the YH term [11]. An eigenvalue analysis of finite-size effects reveals that the eigenvector matrix of Fick diffusivities does not depend on system size, while eigenvalues (describing diffusion speed) do [11]. For Maxwell-Stefan diffusivities, all elements depend on system size, with corrections depending on the matrix of thermodynamic factors [11]. For binary mixtures, the finite-size correction for the Fick diffusion coefficient follows the same form as for self-diffusivities: DFick^∞ = DFick^MD + (k_BTξ)/(6πηL) [11].

Experimental Protocols and Measurement Techniques

Fluorescence Recovery After Photobleaching (FRAP) for Self-Diffusion

Principle: FRAP measures the lateral mobility of fluorescently tagged molecules in membranes or solutions by monitoring the recovery of fluorescence in a photobleached area [12].

Protocol:

- Tag molecules of interest with a fluorescent marker (e.g., GFP, fluorescein)

- Photobleach a defined region using high-intensity laser light

- Monitor fluorescence recovery in the bleached area with low-intensity laser

- Quantify the recovery kinetics using appropriate diffusion models

- Calculate the self-diffusion coefficient from the recovery half-time and bleach spot geometry

Applications: Protein mobility in cell membranes, lipid diffusion, polymer films [12].

Postelectrophoresis Relaxation for Mutual Diffusion

Principle: This technique measures mutual diffusion by analyzing the relaxation of concentration gradients after applying an electric field pulse [12].

Protocol:

- Establish an initial concentration gradient in the sample

- Apply a controlled electric field pulse to induce electrophoretic migration

- Turn off the electric field and monitor the relaxation process via interferometry or spectroscopy

- Analyze the spatial and temporal decay of concentration gradients

- Extract mutual diffusion coefficients from relaxation kinetics

Applications: Protein solutions, colloidal suspensions, polyelectrolyte mixtures.

Molecular Dynamics Simulation Protocol for Diffusion Coefficients

System Setup:

- Build initial configuration with appropriate number of molecules (≥1000 recommended)

- Apply periodic boundary conditions to minimize finite-size effects

- Select appropriate force field parameters for all molecular interactions

Equilibration Phase:

- Energy minimization using steepest descent or conjugate gradient algorithm

- NVT equilibration (constant number of particles, volume, and temperature) for 1-5 ns

- NPT equilibration (constant number of particles, pressure, and temperature) for 5-10 ns

Production Phase:

- Conduct equilibrium molecular dynamics simulation for sufficient duration (≥50 ns)

- Record particle trajectories at appropriate intervals (0.1-1 ps)

- For self-diffusion: Calculate mean-squared displacement (MSD) of individual molecules

- For mutual diffusion: Compute Onsager coefficients from velocity cross-correlations

- Apply finite-size corrections using YH formalism for accurate thermodynamic limit values

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Table 3: Essential Materials for Diffusion Coefficient Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Deuterated Solvents | NMR-based diffusion measurements without interference | D₂O, CDCl₃, DMSO-d₆ |

| Fluorescent Tags | Molecular labeling for FRAP measurements | GFP, fluorescein, rhodamine |

| Force Fields | Molecular dynamics simulations | CHARMM, AMBER, OPLS for organic molecules |

| Deep Eutectic Solvents | Environmentally friendly solvent media for pharmaceutical applications | Caprylic acid-based DES [13] |

| Porous Media Models | Studying confinement effects on diffusion | Nanotubes, controlled pore glasses [13] |

| Ternary Model Systems | Validation of multicomponent diffusion theories | Chloroform/acetone/methanol [11] |

Visualization of Diffusion Relationships and Workflows

Diagram 1: Workflow for computing and correcting diffusion coefficients in MD simulations, showing the different pathways for self-diffusion and mutual diffusion.

Diagram 2: Differential response of self-diffusion and mutual diffusion coefficients to intermolecular interactions, based on theoretical and experimental observations.

In molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, accurately predicting transport properties like diffusion coefficients is essential for applications ranging from industrial process design to drug development. A significant challenge in this field is the presence of finite-size effects, where the computed values of these properties depend on the size of the simulation box used. This application note details the core scaling relationship, N^(-1/3), its theoretical foundation, and provides practical protocols for applying finite-size corrections, with a specific focus on Maxwell-Stefan diffusion coefficients in molecular mixtures [2].

The observed finite-size effects arise from the use of periodic boundary conditions in MD simulations. Computed diffusivities have been shown to increase with the number of molecules (N) in the simulation box, meaning that results from finite systems deviate from the true values at the thermodynamic limit (where N approaches infinity). Correcting for this bias is not merely a procedural step but is critical for obtaining reliable data comparable to experimental results, particularly for mixtures near phase separation where the errors can be exceptionally large [2].

Theoretical Foundation: The N^(-1/3) Dependency

The finite-size effect on self-diffusion coefficients manifests as a linear dependency on the inverse of the simulation box's side length. Since the box length (L) is proportional to N^(1/3) for a cubic box, this relationship is equivalently expressed as a linear function of N^(-1/3) [2].

Table 1: Core Scaling Relationships for Diffusion Coefficients in MD Simulations

| Diffusion Coefficient Type | Finite-Size Scaling Relationship | Key Determinants of the Finite-Size Effect |

|---|---|---|

Self-Diffusion (D_self) |

Scales linearly with N^(-1/3) (or 1/L) [2]. |

System size (L), Temperature (T), Shear viscosity (η) [2]. |

Maxwell-Stefan (Ä_MS) |

Scaling is influenced by N^(-1/3) but is more complex [2]. |

System size (L), Temperature (T), Shear viscosity (η), Thermodynamic factor (Γ) [2]. |

The foundational correction for self-diffusion coefficients was derived by Yeh and Hummer (YH) based on hydrodynamic theory [2]. The Yeh-Hummer correction estimates the self-diffusion coefficient in the thermodynamic limit (D_self∞) from the finite-size value (D_self) obtained via MD simulation using the following equation:

D_self∞ = D_self + D_YH

Where the YH correction term is: D_YH = (k_B * T * ξ) / (3 * π * η * L)

Variables: k_B is the Boltzmann constant, T is temperature, η is shear viscosity, L is the box length, and ξ is a dimensionless constant (2.837297 for cubic boxes with periodic boundary conditions) [2].

For Maxwell-Stefan (MS) diffusivities, the finite-size effect is more complex. While it also depends on system size, temperature, and viscosity, it exhibits a strong additional dependence on the non-ideality of the mixture, quantified by the thermodynamic factor (Γ). Research has shown that for mixtures close to demixing, where the thermodynamic factor is large, the required finite-size correction can be even greater than the simulated MS diffusivity itself [2].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Correcting Self-Diffusion Coefficients

This protocol outlines the steps to compute and correct self-diffusion coefficients for a species in a binary mixture using Equilibrium Molecular Dynamics (EMD).

1. Simulation Setup:

- Software: Use an EMD-capable package (e.g., GROMACS, LAMMPS).

- System: Construct a cubic simulation box containing N molecules of a binary mixture.

- Ensemble: Run simulations in the NVT or NPT ensemble to ensure proper equilibrium state sampling.

- Boundary Conditions: Apply periodic boundary conditions in all three dimensions.

2. Data Collection via Einstein Formulation:

- Calculate the self-diffusion coefficient for species

i(D_self,i) from the mean-square displacement (MSD) of its molecules [2]:D_self,i = (1 / 6) * lim (t→∞) d/(dt) 〈 (1/N_i) * Σ |r_j,i(t) - r_j,i(0)|^2 〉 - Parameters:

N_iis the number of molecules of speciesi,r_j,iis the position vector of thej-th molecule of speciesi, and angle brackets denote the ensemble average.

3. Shear Viscosity Calculation:

- Compute the shear viscosity (

η) using the Green-Kubo relation, which integrates the autocorrelation of the off-diagonal elements of the stress tensor (P_αβ) [2]:η = (V / k_B T) * ∫_0^∞ 〈 P_αβ(0) P_αβ(t) 〉 dt - The shear viscosity is typically independent of system size and can be treated as a constant for the correction [2].

4. Application of Yeh-Hummer Correction:

- Apply the YH correction for each species using the formula in Section 2 to obtain the size-corrected self-diffusion coefficient,

D_self∞,i.

Protocol 2: Correcting Maxwell-Stefan Diffusion Coefficients

This protocol describes the methodology for obtaining finite-size corrected Maxwell-Stefan diffusivities, which describe collective motion in mixtures.

1. Simulation Setup: Follow the same setup as in Protocol 1.

2. Onsager Coefficients Calculation:

- Compute the Onsager coefficients (

Λ_ij) from the cross-correlation of molecular displacements [2]:Λ_ij = (1 / (6 * t * N)) * lim (t→∞) d/(dt) Σ Σ 〈 (r_k,i(t) - r_k,i(0)) * (r_l,j(t) - r_l,j(0)) 〉where the summations are over all molecules of speciesiandj.

3. Finite-Size MS Diffusivity Calculation:

- Calculate the finite-size Maxwell-Stefan diffusivity (

Ä_MS) from the Onsager coefficients and the mixture composition.

4. Correction to Thermodynamic Limit:

- Current research indicates that a correction for MS diffusivities is necessary and is a function of the viscosity, box size, and the thermodynamic factor (Γ) [2].

- The thermodynamic factor, which measures mixture non-ideality, can be obtained from equations of state or free energy calculations.

- The specific formulation of this correction is an active area of research, and practitioners should consult the latest literature (e.g., [2]) for the most current correction procedures.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Category | Item / Software | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Software Tools | GROMACS, LAMMPS | Molecular dynamics simulation packages for performing EMD simulations and calculating trajectories. |

| Custom Scripts (Python/MATLAB) | For data analysis, including calculating MSD, applying the YH correction, and computing viscosities. | |

| Theoretical Models | Lennard-Jones Potential | A model intermolecular potential used to simulate a wide variety of binary systems for method verification [2]. |

| Yeh-Hummer (YH) Correction | The analytic correction term for extrapolating self-diffusion coefficients to the thermodynamic limit [2]. | |

| Physical Properties | Shear Viscosity (η) | A key transport property required for calculating the finite-size correction [2]. |

| Thermodynamic Factor (Γ) | A measure of mixture non-ideality, crucial for correcting Maxwell-Stefan diffusivities [2]. |

Workflow and Relationship Visualizations

Diagram 1: Finite-Size Correction Workflow for MD Simulations.

Diagram 2: The N^(-1/3) Relationship and Correction Logic.

Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations have emerged as a powerful computational tool for predicting transport properties, including diffusion coefficients, which are crucial for understanding mass transport in chemical and biological systems. However, a fundamental limitation persists: the number of molecules in a typical MD simulation is orders of magnitude lower than in real physical systems at the thermodynamic limit. This discrepancy introduces significant finite-size effects in computed diffusivities [2] [14]. The recognition and systematic correction of these artifacts have been a central challenge in computational physics and chemistry. This review traces the historical development of finite-size corrections for diffusion coefficients, beginning with the foundational work of Dünweg and Kremer and culminating in the widely adopted Yeh-Hummer (YH) correction, while also exploring its extensions to more complex systems.

The core issue stems from the use of Periodic Boundary Conditions (PBC). While PBC minimize surface effects and are computationally efficient, they introduce artificial hydrodynamic interactions between a molecule and its periodic images. Dünweg and Kremer first quantitatively demonstrated that self-diffusivities computed from MD scale linearly with the inverse of the simulation box length (1/L) [11]. This finding established a systematic framework for understanding finite-size dependencies, setting the stage for the development of robust correction schemes.

Foundational Work: Dünweg and Kremer's Pioneering Insight

In the early 1990s, the work of Dünweg and Kremer provided the first major insight into the system-size dependence of self-diffusion coefficients [11] [14]. Through MD simulations, they established an empirical relationship showing that the computed self-diffusivity ((D_{\text{self}}^{\text{MD}})) decreases linearly with the inverse of the side length ((L)) of a cubic simulation box. Their work highlighted that the finite-size effect was not a mere numerical artifact but a consequence of the hydrodynamic self-interactions imposed by PBC. This linear relationship with 1/L became the cornerstone for all subsequent theoretical developments, including the Yeh-Hummer correction.

The Yeh-Hummer Correction: A Landmark Theoretical Advancement

Building upon the empirical foundation laid by Dünweg and Kremer, Yeh and Hummer performed a detailed investigation in 2004, leading to a seminal analytical correction [2] [11]. They derived the now-famous YH correction term based on hydrodynamic theory for a spherical particle in a Stokes flow with PBC. The correction allows researchers to extrapolate the self-diffusion coefficient from a finite simulation box to the thermodynamic limit ((D_{\text{self}}^{\infty})).

The central equation is:

[ D{\text{self}}^{\infty} = D{\text{self}}^{\text{MD}} + \frac{k_{B} T \xi}{6 \pi \eta L} ]

Here:

- (D_{\text{self}}^{\text{MD}}) is the self-diffusivity obtained directly from the MD simulation.

- (k_{B}) is the Boltzmann constant.

- (T) is the system temperature.

- (\eta) is the shear viscosity of the fluid.

- (L) is the side length of the cubic simulation box.

- (\xi) is a dimensionless constant equal to 2.837297 for cubic boxes [2] [11].

A key insight from Yeh and Hummer was that the shear viscosity ((\eta)) itself, computed from the same MD simulation, does not exhibit significant finite-size effects [2]. This makes the correction self-consistent, as the viscosity required for the formula can be reliably obtained from the finite simulation.

Table 1: Key Parameters in the Yeh-Hummer Correction for Self-Diffusion

| Parameter | Symbol | Description | Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| Boltzmann Constant | (k_B) | Fundamental physical constant | (1.380649 \times 10^{-23} \text{J/K}) |

| System Temperature | (T) | Absolute temperature of simulation | Input from MD setup |

| Shear Viscosity | (\eta) | Viscosity of the fluid | Computed from the same MD simulation |

| Box Size | (L) | Side length of cubic simulation box | Known simulation parameter |

| Dimensionless Constant | (\xi) | Geometric factor for PBC | (\xi = 2.837297) for cubic boxes |

Extension to Mutual Diffusion Coefficients

While the original YH correction was derived for self-diffusion, its application to mutual diffusion coefficients—which describe collective mass transport due to concentration gradients—required further research. Two key mutual diffusion formalisms are the Fick and Maxwell-Stefan (MS) diffusivities [2].

Binary Mixtures

For binary mixtures, the finite-size effect on the Fick diffusion coefficient ((D_{\text{Fick}})) was found to be identical to that for self-diffusion [11]:

[ D{\text{Fick}}^{\infty} = D{\text{Fick}}^{\text{MD}} + \frac{k_{B} T \xi}{6 \pi \eta L} ]

The correction for the MS diffusivity ((\Ä_{\text{MS}})) must account for the non-ideality of the mixture, captured by the thermodynamic factor ((\Gamma)) [2]:

[ \Ä{\text{MS}}^{\infty} = \Ä{\text{MS}}^{\text{MD}} + \frac{1}{\Gamma} \frac{k_{B} T \xi}{6 \pi \eta L} ]

This relationship is critical because it shows that for mixtures close to demixing, where (\Gamma) is large, the finite-size correction can be even greater than the simulated diffusivity itself [2].

Multicomponent Mixtures

The generalization to multicomponent systems revealed that only the eigenvalues of the Fick diffusion matrix, which represent the intrinsic rates of diffusion, are subject to finite-size effects. The eigenvector matrix, which defines the diffusion modes, is independent of system size [11]. Consequently, the finite-size correction for the matrix of Fick diffusivities (([\mathbf{D}_{\text{Fick}}])) is applied by adding the standard YH term to the diagonal elements [11].

Advanced Protocols and Application Notes

Protocol 1: Correcting Self-Diffusion Coefficients

This protocol details the steps for obtaining a finite-size corrected self-diffusion coefficient for a pure substance or a component in a mixture.

- System Preparation: Construct a cubic simulation box containing (N) molecules. Ensure the system is equilibrated at the desired temperature and pressure.

- MD Simulation: Perform a sufficiently long Equilibrium MD (EMD) simulation in the NVT or NPT ensemble using a reliable force field.

- Compute Self-Diffusivity ((D{\text{self}}^{\text{MD}})): Use the Einstein relation from the mean-squared displacement (MSD) of the molecules [2]: [ D{\text{self, } i}^{\text{MD}} = \frac{1}{6Ni t} \left\langle \sum{j=1}^{Ni} \left[ \mathbf{r}{j,i}(t0 + t) - \mathbf{r}{j,i}(t0) \right]^2 \right\rangle{t0} ] where (Ni) is the number of molecules of species (i), and (\mathbf{r}_{j,i}) is the position of the (j)-th molecule of species (i).

- Compute Shear Viscosity ((\eta)): Calculate the viscosity from the Green-Kubo relation, which integrates the autocorrelation function of the off-diagonal elements of the stress tensor ((\mathbf{P}{\alpha\beta})) [2]: [ \eta = \frac{V}{kB T} \int0^\infty \left\langle P{\alpha\beta}(t0) P{\alpha\beta}(t0 + t) \right\rangle{t_0} dt ] where (V) is the volume of the system. The average is typically taken over the three independent off-diagonal components (xy, xz, yz).

- Apply YH Correction: Calculate the corrected self-diffusivity at the thermodynamic limit using the box length (L = V^{1/3}): [ D{\text{self}}^{\infty} = D{\text{self}}^{\text{MD}} + \frac{k_{B} T \xi}{6 \pi \eta L} ]

The following workflow diagram illustrates this protocol:

Protocol 2: Correcting Mutual Diffusion in a Binary Mixture

This protocol extends the correction to Maxwell-Stefan diffusivities, which are crucial for describing mass transport in mixtures.

- Steps 1-4: Follow Protocol 1 to perform the simulation and obtain the viscosity ((\eta)) and box size ((L)).

- Compute MS Diffusivity ((\Ä{\text{MS}}^{\text{MD}})): Calculate the Onsager coefficients ((\Lambda{ij})) from the cross-correlations of molecular displacements [2], then derive the MS diffusivity.

- Determine Thermodynamic Factor ((\Gamma)): Compute (\Gamma) from the derivative of the activity coefficient with respect to concentration, often obtained via free energy methods or Kirkwood-Buff analysis [2] [11].

- Apply Binary MS Correction: Calculate the corrected MS diffusivity using the thermodynamic factor: [ \Ä{\text{MS}}^{\infty} = \Ä{\text{MS}}^{\text{MD}} + \frac{1}{\Gamma} \frac{k_{B} T \xi}{6 \pi \eta L} ]

Table 2: Summary of Finite-Size Correction Formulas for Different Diffusion Coefficients

| Diffusion Coefficient | Symbol | Finite-Size Correction Formula | Key Dependencies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Self-Diffusivity | (D_{\text{self}}^{\infty}) | ( D{\text{self}}^{\text{MD}} + \frac{k{B} T \xi}{6 \pi \eta L} ) | Box size (L), Viscosity (η), Temp (T) |

| Fick Diffusivity (Binary) | (D_{\text{Fick}}^{\infty}) | ( D{\text{Fick}}^{\text{MD}} + \frac{k{B} T \xi}{6 \pi \eta L} ) | Box size (L), Viscosity (η), Temp (T) |

| Maxwell-Stefan Diffusivity (Binary) | (\Ä_{\text{MS}}^{\infty}) | ( \Ä{\text{MS}}^{\text{MD}} + \frac{1}{\Gamma} \frac{k{B} T \xi}{6 \pi \eta L} ) | Box size (L), Viscosity (η), Temp (T), Thermodynamic Factor (Γ) |

| Fick Diffusivity (Multicomponent) | ([\mathbf{D}_{\text{Fick}}^{\infty}]) | ( [\mathbf{D}{\text{Fick}}^{\text{MD}}] + \frac{k{B} T \xi}{6 \pi \eta L} \mathbf{I} ) | Box size (L), Viscosity (η), Temp (T) (applied to diagonal) |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Computational Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Finite-Size Diffusion Studies

| Tool / "Reagent" | Function / Purpose | Example Application / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Dynamics Engine | Software to perform the simulations. | LAMMPS [11], GROMACS |

| Force Field Parameters | Define interatomic potentials and charges. | OPLS-AA, CHARMM; Critical for accuracy of both dynamics and thermodynamics [11]. |

| Kirkwood-Buff Analysis Code | Computes the thermodynamic factor (Γ). | OCTP plugin for LAMMPS; Essential for MS diffusivity correction [11]. |

| System Builder | Creates initial molecular configurations. | PACKMOL [11] |

| YH Correction Script | Custom script to apply the correction. | In-house Python/MATLAB code implementing the formulas in Table 2. |

| Epirubicinol | Epirubicinol Research Compound|Supplier | Epirubicinol, a primary metabolite of Epirubicin. Vital for cancer therapy metabolism and mechanism of action studies. For Research Use Only. |

| Flumethrin | Flumethrin CAS 69770-45-2 - Research Grade | High-purity Flumethrin for veterinary parasitology research. Explore its application as a pyrethroid acaricide and insecticide. This product is for Research Use Only (RUO). Not for human or veterinary use. |

Special Cases and Recent Developments

Rotational Diffusion

The finite-size formalism has been extended beyond translational diffusion. For rotational diffusion of membrane proteins, the apparent coefficient ((D{\text{rot}}^{\text{PBC}})) slows down relative to the infinite-system value ((D{\text{rot}}^{0})) approximately as [15]: [ D{\text{rot}}^{\text{PBC}} \approx D{\text{rot}}^{0} \left( 1 - \frac{\pi RH^2}{A} \right) ] where (RH) is the protein's hydrodynamic radius and (A) is the area of the periodic membrane patch. This correction is significant in membrane simulations where the protein covers a substantial fraction of the simulation box [15].

Macromolecules and Higher-Order Corrections

For large solutes like proteins, the standard YH correction (a first-order term in 1/L) may be insufficient. Yeh and Hummer originally noted an additional, higher-order term proportional to (1/L^3) [16]: [ D{\text{pbc}} = D0 - \frac{kB T \xi}{6 \pi \eta{\text{sol}} L} + \frac{2 kB T R^2}{9 \eta{\text{sol}} L^3} ] where (R) is the solute's hydrodynamic radius. This term becomes non-negligible when the solute size ((R)) is large compared to the box size ((L)). For accurate results with macromolecules, ensuring (L > 7.4R) is recommended to keep the higher-order contribution below 1% [16]. When this is computationally prohibitive, a scheme fitting simulation data at multiple box sizes to the unsimplified equation becomes necessary.

The following diagram illustrates the decision process for applying the appropriate level of correction:

The journey from the initial observation of finite-size effects by Dünweg and Kremer to the comprehensive analytical correction by Yeh and Hummer has profoundly impacted the reliability of MD simulations. The YH correction provides a robust, physics-based method to obtain diffusion coefficients at the thermodynamic limit from finite-sized simulations. Its successful extension to mutual diffusion coefficients in binary and multicomponent mixtures, as well as to rotational diffusion and macromolecular systems, has made it an indispensable tool in the computational scientist's arsenal. For researchers in drug development, applying these protocols ensures that predicted diffusivities—key parameters in understanding drug transport and binding kinetics—are quantitatively accurate and directly comparable to experimental results.

Practical Implementation: Correction Methods for Different Diffusion Coefficients

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation has become an indispensable tool for calculating transport properties, such as self-diffusion coefficients, which are crucial for understanding mass transfer in chemical, pharmaceutical, and materials science applications [17] [18]. However, a significant challenge persists: MD simulations typically model systems containing thousands to millions of molecules, whereas real-world systems approach the thermodynamic limit (~10²³ molecules) [2]. This disparity causes finite-size effects that substantially influence computed diffusivities.

The Yeh-Hummer (YH) correction addresses this fundamental limitation by providing a robust method to extrapolate self-diffusion coefficients from finite simulation boxes to their thermodynamic limit values [2]. This protocol explores the theoretical foundation, practical application, and implementation nuances of the YH correction, framed within broader research on finite-size effects in diffusion coefficient calculation.

Theoretical Foundation

The Finite-Size Problem in Diffusion Calculations

In MD simulations under periodic boundary conditions (PBC), calculated self-diffusion coefficients exhibit a predictable dependence on system size. The primary origin of this artifact is hydrodynamic self-interaction—a particle's interaction with its periodic images—which alters diffusion dynamics [2]. Computed self-diffusivities consistently increase with the number of molecules (N) in the simulation box, scaling linearly with N^(-1/3) or equivalently with 1/L, where L is the box length [2].

The Yeh-Hummer Equation

Yeh and Hummer derived an analytical correction based on hydrodynamic theory for a spherical particle in Stokes flow with PBC. The correction relates the self-diffusion coefficient in the thermodynamic limit (D∞) to the finite-size value obtained from MD simulation (DMD) [2]:

D∞ = DMD + D_YH

where the Yeh-Hummer correction term D_YH is defined as:

DYH = (kB T ξ) / (6 π η L)

The equation variables and constants are summarized in the table below:

Table 1: Parameters in the Yeh-Hummer Correction Equation

| Parameter | Description | Units | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| D_∞ | Self-diffusion coefficient at thermodynamic limit | m²/s | Extrapolated value for real systems |

| D_MD | Self-diffusion coefficient from MD simulation | m²/s | Computed from MSD or VACF |

| k_B | Boltzmann constant | J/K | 1.38065 × 10â»Â²Â³ J/K |

| T | Temperature | K | System temperature |

| η | Shear viscosity | Pa·s | Calculated from MD simulation |

| L | Box length | m | Side length of cubic simulation box |

| ξ | Dimensionless constant | - | 2.837297 for cubic boxes with PBC |

The following diagram illustrates the theoretical relationship between finite-size effects and the application of the YH correction:

Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for YH Correction Implementation

| Category | Item | Function/Description | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Force Fields | OPLS4 | Defines molecular interactions and potentials | Provides accurate diffusion predictions [18] |

| Lennard-Jones | Model potential for simple fluids | Verification of finite-size effects [2] | |

| Water Models | TIP3P, TIP4P, SPC/E | Specific water molecular models | Performance varies in diffusion calculations [18] |

| Software Tools | Molecular Dynamics Packages | GROMACS, Desmond, LAMMPS, etc. | Generates particle trajectories [18] |

| Analysis Scripts | Python, MATLAB, R scripts | Implements YH correction calculations | |

| System Components | Periodic Boundary Conditions | Standard MD simulation setup | Required for YH correction application [2] |

| Thermostats & Barostats | Nose-Hoover, Langevin, etc. | Maintain ensemble conditions (NVT, NPT) [18] |

Implementation Protocols

Core Methodology for Self-Diffusion Coefficient Calculation

The following workflow outlines the complete process for calculating size-corrected self-diffusion coefficients:

Protocol 1: MD Simulation for Diffusion Coefficients

System Setup

- Force Field Selection: Employ appropriate force fields (e.g., OPLS4 for organic liquids) [18]

- System Builder: Construct cubic simulation cells with periodic boundary conditions

- Minimum System Size: Include ≥1000 molecules to minimize statistical uncertainty [13] [18]

- Initialization: Use Brownian dynamics at low temperature (10 K) for 100 ps with 1 fs timestep for stable initialization [18]

Equilibration Procedure

- NVT Ensemble: 100 ps at 10 K using Langevin thermostat

- Temperature Ramp: 100 ps at target temperature

- NPT Ensemble: 20 ns at target temperature and pressure (1.01325 bar) using Nose-Hoover thermostat and Martyna-Tobias-Klein barostat [18]

- Timestep: 2 fs for numerical stability

- Electrostatics: Utilize u-series algorithm with 9.0 Ã… cutoff for short-range interactions [18]

Production Run

- Duration: 40 ns for high-diffusivity systems (log D > -9.5), 150 ns for low-diffusivity systems [18]

- Ensemble: NPT maintained at target conditions

- Trajectory Saving: Save frames at 4 ps intervals for MSD calculation [18]

Protocol 2: Mean Square Displacement Calculation

The Einstein formulation provides the most straightforward approach for self-diffusion coefficient calculation:

DMD = (1/(6t)) × lim(t→∞) ⟨|ri(t) - r_i(0)|²⟩

where r_i(t) is the position of molecule i at time t, and ⟨·⟩ denotes ensemble averaging [17] [18].

Implementation Steps

- Center of Mass Tracking: Calculate MSD using molecular center of mass

- Averaging: Average MSD over all molecules in the system

- Linear Regression: Fit MSD versus time lag in the normal diffusion regime (typically 12-20 ns for high diffusivity, 45-75 ns for low diffusivity) [18]

- Slope Extraction: D_MD equals one-sixth of the linear regression slope

Exclusion of Abnormal Diffusion

- Identify and exclude initial and final trajectory segments showing nonlinear MSD-t behavior [17]

- Use only the normal diffusion regime where MSD shows linear time dependence

Protocol 3: Viscosity Calculation

The shear viscosity (η) required for the YH correction can be computed from the stress tensor autocorrelation:

η = (V/kB T) × ∫₀^∞ ⟨Pαβ(0) P_αβ(t)⟩ dt

where P_αβ represents off-diagonal components of the stress tensor (α≠β), and V is system volume [2].

Practical Implementation

- Stress Tensor Components: Use Pxy, Pxz, and P_yz components for averaging

- Ensemble Average: Average over all three components for isotropic fluids

- Integration: Employ Green-Kubo formalism with appropriate correlation time

Note: System size dependence of viscosity is negligible, making single-calculation sufficient [2].

Protocol 4: Applying the Yeh-Hummer Correction

Calculation Steps

- Extract Box Length: Calculate L = V^(1/3) from equilibrated simulation volume

- Compute Correction: Apply DYH = (kB T ξ)/(6 π η L) with ξ = 2.837297

- Extrapolate: Calculate D∞ = DMD + D_YH

Validation Procedures

- System Size Series: Perform simulations with varying N (256, 512, 1024, 2048 molecules)

- Convergence Check: Verify linear dependence of D_MD on 1/L

- Extrapolation Validation: Confirm corrected values are system-size independent

Data Analysis and Validation

Quantitative Correction Factors

Table 3: Typical Magnitude of Yeh-Hummer Correction in Various Systems

| System Type | Box Size (nm) | Typical D_MD (10â»â¹ m²/s) | Typical D_YH (10â»â¹ m²/s) | Correction % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pure Water | 3.0-5.0 | 2.3-2.9 | 0.15-0.25 | 5-11% |

| Organic Liquids | 3.5-4.5 | 0.8-2.0 | 0.10-0.20 | 5-25% |

| Ionic Solutions | 4.0-6.0 | 0.5-1.5 | 0.08-0.15 | 5-30% |

| Lennard-Jones Fluids | 3.0-5.0 | 1.5-3.0 | 0.12-0.22 | 4-15% |

Performance and Accuracy Assessment

The YH correction significantly improves agreement with experimental data:

- Pre-Correction Error: Uncorrected MD values may underestimate experimental diffusivities by 5-30% [2]

- Post-Correction Accuracy: Corrected values typically achieve 8-15% average relative deviation from experimental data [17]

- Validation: Comprehensive testing on Lennard-Jones systems and molecular mixtures confirms correction reliability [2]

Advanced Applications and Considerations

Binary and Multicomponent Systems

For mutual diffusion coefficients, finite-size effects become more complex:

- Maxwell-Stefan Diffusivities: Exhibit stronger size dependence than self-diffusion coefficients [2]

- Nonideality Dependence: Finite-size correction depends on thermodynamic factor (Γ) [2]

- Demixing Systems: Near phase separation boundaries, corrections can exceed simulated diffusivity values [2]

Membrane Systems

Rotational diffusion in membrane simulations requires specialized finite-size corrections:

- Box Geometry: Anisotropic systems need modified approaches [15]

- Saffman-Delbrück Model: Basis for membrane-specific corrections [15]

- Area Dependence: Apparent rotational diffusion coefficient decreases with protein-to-box area ratio [15]

The Yeh-Hummer correction provides an essential, theoretically grounded method for addressing finite-size effects in MD-calculated self-diffusion coefficients. Implementation requires careful attention to simulation protocols, viscosity calculation, and linear response regime identification. When properly applied, this correction significantly improves the quantitative accuracy of diffusion coefficients, enabling more reliable prediction of transport properties for pharmaceutical, chemical, and materials applications.

A primary challenge in calculating mixture permeances or diffusion coefficients from Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations is the significant finite-size effect, where the computed values depend on the number of molecules (N) in the simulation box [19] [2]. For self-diffusion coefficients, this manifests as a linear scaling with N–1/3 [2]. For Maxwell-Stefan (MS) diffusion, which describes mass transport due to chemical potential gradients, the problem is more complex. The finite-size effects for MS diffusivities not only depend on the box size, temperature, and viscosity but also exhibit a strong dependence on the thermodynamic factor (Γ), which measures the non-ideality of the mixture [2]. In systems close to demixing, the required finite-size correction can be even larger than the simulated diffusivity value itself, making its application crucial for obtaining reliable, predictive data from MD simulations [2].

The MS diffusion formulation provides the most rigorous framework for describing diffusion in multicomponent systems. The fundamental MS equations relate the chemical potential gradients to the fluxes and friction [19] [20]. For an n-component system, the equation is: [-\frac{ci}{RT} \nabla \mui = \sum{j=1, j \neq i}^{n} \frac{xj Ni - xi Nj}{\Ä{ij}} + \frac{Ni}{\Äi} \quad ; \quad i=1,2,\dots,n] where (ci) is the concentration of species i, (\nabla \mui) is its chemical potential gradient, (xi) is its mole fraction, (Ni) is its molar flux, (\Äi) is its diffusivity representing species-wall interactions, and (\Ä{ij}) is the MS exchange coefficient between components i and j [19]. The Fick diffusivity ((D{\text{Fick}})), more commonly used in industrial applications, is related to the MS diffusivity ((\Ä{MS})) through the thermodynamic factor: (D{\text{Fick}} = \Gamma \cdot \Ä{MS}) [2].

Table 1: Key Diffusion Coefficients and Their Relationships

| Coefficient Type | Symbol | Defining Characteristic | Primary Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Self-Diffusion | (D_{self}) | Motion of a tagged particle in a uniform medium. | Probing molecular-level Brownian motion. |

| Maxwell-Stefan (MS) | (\Ä_{MS}) | Describes transport against chemical potential gradients; accounts for molecule-molecule friction. | Fundamental, rigorous modeling of multicomponent mixture diffusion. |

| Fickian | (D_{Fick}) | Relates mass flux directly to concentration gradient. | Common in industrial design and process simulation. |

Finite-Size Correction Methodology

The finite-size effects for self-diffusion coefficients are successfully corrected by the Yeh and Hummer (YH) term [2]. This correction is derived from hydrodynamic theory for a spherical particle in a Stokes flow with periodic boundary conditions and accounts for the difference in hydrodynamic self-interactions between a finite (periodic) and an infinite (non-periodic) system. The self-diffusion coefficient in the thermodynamic limit ((D{i,self}^\infty)) is obtained from the finite-size value from MD ((D{i,self})) using: [D{i,self}^\infty = D{i,self} + D{YH}] [D{YH} = \frac{kB T \xi}{6 \pi \eta L}] where (kB) is the Boltzmann constant, T is the temperature, (\eta) is the shear viscosity of the system, L is the side length of the (cubic) simulation box, and (\xi) is a dimensionless constant equal to 2.837297 [2].

This YH correction forms the basis for the extension to MS diffusivities. The proposed correction for the Maxwell-Stefan diffusion coefficient in a binary mixture to the thermodynamic limit ((\Ä{MS}^\infty)) is given by: [\Ä{MS}^\infty = \Ä{MS} + \Gamma \cdot D{YH}] Here, (\Gamma) is the thermodynamic factor for the binary mixture. This equation indicates that the finite-size effect on mutual diffusion is amplified by the non-ideality of the mixture [2]. In highly non-ideal systems, particularly those near demixing where (\Gamma) can be very large, the correction term (\Gamma \cdot D{YH}) can dominate the raw simulated value of (\Ä{MS}).

Table 2: Finite-Size Correction Terms for Diffusion Coefficients

| Correction For | Finite-Size Value | Thermodynamic Limit Value | Key Correction Formula |

|---|---|---|---|

| Self-Diffusion | (D_{i,self}) | (D{i,self}^\infty = D{i,self} + D_{YH}) | (D{YH} = \frac{kB T \xi}{6 \pi \eta L}) |

| Maxwell-Stefan Diffusion | (\Ä_{MS}) | (\Ä{MS}^\infty = \Ä{MS} + \Gamma \cdot D_{YH}) | (\Gamma) = Thermodynamic Factor |

The following workflow diagram outlines the sequential protocol for applying these corrections, from MD simulation to the final corrected diffusivity.

Detailed Experimental and Computational Protocols

Protocol 1: Equilibrium MD Simulation for Diffusion Data

This protocol details the setup for obtaining finite-size self-diffusion and MS diffusion coefficients from Equilibrium Molecular Dynamics (EMD).

1. System Preparation:

- Force Field Selection: Choose an appropriate all-atom or coarse-grained force field. For Lennard-Jones (LJ) systems, use standard LJ parameters [2].

- Initial Configuration: Construct a cubic simulation box containing N molecules of the binary mixture (e.g., N = 500, 1000, 2000) at the desired composition and density. Use packing software like PACKMOL for molecular systems.

- Equilibration: Energy-minimize the system. Then, run an isothermal-isobaric (NPT) ensemble simulation for at least 1-5 ns to relax the density to the target pressure (e.g., 1 bar) and temperature. Follow with a canonical (NVT) ensemble simulation for further equilibration. Use a thermostat like Nosé-Hoover and, for NPT, a barostat like Parrinello-Rahman.

2. Production Run (NVT Ensemble):

- Simulation Length: Run a sufficiently long simulation (tens to hundreds of nanoseconds) in the NVT ensemble to ensure proper convergence of the mean-square displacement (MSD). The required time depends on the system viscosity and diffusivity.

- Trajectory Saving: Save the atomic coordinates (trajectory) at intervals short enough to capture molecular motion (e.g., 1-10 ps).

3. Data Analysis:

- Self-Diffusion Coefficient ((D{self})): Use the Einstein relation from the linear regime of the mean-square displacement (MSD) vs. time plot [2]: ( D{i,self} = \frac{1}{6} \lim{t \to \infty} \frac{d}{dt} \left\langle | \mathbf{r}j(t) - \mathbf{r}j(0) |^2 \right\rangle ) where (\mathbf{r}j) is the position of a molecule j of species i, and the angle brackets denote the ensemble average over all molecules of species i and time origins.

- MS Diffusion Coefficient ((\Ä{MS})): Calculate the Onsager coefficients ((\Lambda{ij})) from the cross-correlations of molecular displacements [2]: ( \Lambda{ij} = \frac{1}{6Nt} \lim{t \to \infty} \frac{d}{dt} \left\langle \sum{l=1}^{Ni} [\mathbf{r}{l,i}(t) - \mathbf{r}{l,i}(0)] \cdot \sum{m=1}^{Nj} [\mathbf{r}{m,j}(t) - \mathbf{r}{m,j}(0)] \right\rangle ) For a binary mixture, the MS diffusivity is then obtained from the Onsager coefficients and mole fractions ((xi)) as: (\Ä{MS} = \frac{\Lambda{11}}{x2^2} - \frac{2\Lambda{12}}{x1 x2} + \frac{\Lambda{22}}{x_1^2}).

Protocol 2: Calculation of Auxiliary Properties

1. Shear Viscosity ((\eta)):

- Method: Use the Green-Kubo formula, which relates viscosity to the integral of the stress tensor autocorrelation function [2]: ( \eta = \frac{V}{kB T} \int0^\infty \left\langle P{\alpha\beta}(t) \cdot P{\alpha\beta}(0) \right\rangle dt ) where V is the volume, and (P_{\alpha\beta}) represents the off-diagonal components (xy, xz, yz) of the stress tensor. The average is taken over these three components.

- Implementation: Compute the stress tensor during the NVT production run and calculate its autocorrelation function. The viscosity is the integral of this decay. Ensure the correlation function has decayed to zero.

2. Thermodynamic Factor ((\Gamma)):

- Method via MD: The thermodynamic factor can be computed from the derivative of the activity with respect to concentration. In a Grand Equilibrium MD (GEMC) simulation, it can be derived from the concentration fluctuations in the system [2].

- Method via Equation of State: If a reliable equation of state (EOS) is available for the mixture, (\Gamma) can be calculated from the excess Gibbs energy model. For a binary mixture, (\Gamma = 1 + \frac{\partial \ln \gamma1}{\partial \ln x1}), where (\gamma_1) is the activity coefficient of component 1.

Protocol 3: Application of the Finite-Size Correction

1. Calculate the YH Correction ((D_{YH})):

- Gather the required parameters: Temperature (T) from the simulation, shear viscosity ((\eta)) from Protocol 2, and the box length (L) from the average simulation box volume during the NVT production run ((L = V^{1/3})).

- Use the formula: ( D{YH} = \frac{kB T \cdot 2.837297}{6 \pi \eta L} ).

2. Apply the Corrections:

- For Self-Diffusivity: For each species i, compute (D{i,self}^\infty = D{i,self} + D_{YH}).

- For MS Diffusivity: Compute (\Ä{MS}^\infty = \Ä{MS} + \Gamma \cdot D_{YH}), where (\Gamma) is the binary thermodynamic factor from Protocol 2.

3. Validation:

- Repeat Protocols 1-3 for different system sizes (e.g., N=500, 1000, 2000). The corrected values (\Ä{MS}^\infty) and (D{i,self}^\infty) for the different system sizes should converge, validating the correction. Significant remaining discrepancies indicate insufficient simulation length or problems in the force field.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools and Parameters for Finite-Size Correction Studies

| Item / Parameter | Function / Description | Example / Typical Value |

|---|---|---|

| MD Software | Software package to perform simulations and trajectory analysis. | GROMACS, LAMMPS, HOOMD-blue |

| Force Field | Set of parameters defining interatomic potentials. | OPLS-AA, CHARMM, TraPPE (for LJ fluids) |

| Thermodynamic Factor (Γ) | Quantifies non-ideality of the mixture; critical for MS correction. | Γ = 1 for ideal mixtures; can be >>1 near demixing |

| Shear Viscosity (η) | Measure of fluid's resistance to flow; required for YH correction. | Computed from stress tensor autocorrelation (Green-Kubo) |

| YH Constant (ξ) | Dimensionless constant for periodic cubic boxes. | ξ = 2.837297 |

| Binary LJ System | A standardized model system for method validation. | Methanol, Water, Ethanol, Acetone mixtures [2] |

| Elisartan | Elisartan|Angiotensin II Receptor Blocker (ARB) | Elisartan is a non-peptide angiotensin II receptor antagonist for research use. This product is for Research Use Only (RUO), not for human consumption. |

| 6-Methylchrysene | 6-Methylchrysene, CAS:1705-85-7, MF:C19H14, MW:242.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Application Notes and Validation

The finite-size correction for MS diffusion has been validated for a wide range of systems. The methodology was verified for over 200 distinct binary Lennard-Jones systems and 9 real molecular binary systems, including mixtures of methanol, water, ethanol, acetone, methylamine, and carbon tetrachloride [2]. The success across this diverse set confirms the correction's general applicability.

A critical application is in the estimation of mixture permeances across porous membranes from unary permeation data, which relies on accurate MS diffusion coefficients [19]. Two limiting scenarios are often considered:

- Correlations Negligible: The permeance of each component in the mixture equals that of its pure component. This occurs when (\Äi / \Ä{ij}) is small.

- Correlations Dominant: The permeances in the mixture differ significantly from pure component values, dictated by both mobilities and adsorption equilibrium [19].

Applying the finite-size correction ensures that the MS diffusivities fed into these models, such as the Maxwell-Stefan equations for membrane permeation, represent true thermodynamic-limit properties, leading to more reliable predictions of mixture separation performance. Furthermore, using the corrected MS diffusivities is vital for accurately predicting reaction rates and selectivities in catalytic particles, where simplified models like Fick-Wilke often fail to simultaneously capture effectiveness factors and selectivity [21].

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation has emerged as a powerful tool for computing diffusion coefficients in liquid mixtures, essential for designing processes in chemical engineering and drug development [11]. A significant challenge is that MD simulations are performed with a finite number of molecules, which introduces spurious finite-size effects that prevent direct comparison with experimental data [11] [2]. For self-diffusion coefficients, the finite-size correction derived by Yeh and Hummer (YH) is well-established [11] [2]. This document outlines the generalized finite-size correction formulations for mutual diffusion coefficients in multicomponent mixtures, enabling researchers to obtain reliable, quantitatively accurate diffusion data comparable to experimental results [11].

Theoretical Background

Diffusion Coefficients in Mixtures

In MD simulations, two main types of mutual diffusion coefficients are used to describe mass transport:

- Fick Diffusion coefficients (( D_{Fick} )): These describe the flux of a species in response to a concentration gradient according to Fick's law. They are experimentally measurable [22].

- Maxwell-Stefan (MS) diffusion coefficients (( \Ä_{ij} )): These describe diffusion driven by chemical potential gradients, balanced by friction forces between components. They are directly computed from equilibrium MD simulations [11] [22].

For an (n)-component mixture, the matrix of Fick diffusivities, ([D{Fick}]), and the MS diffusivities are related via the matrix of thermodynamic factors, ([\Gamma]) [11]: [ [D{Fick}] = [B]^{-1} [\Gamma] ] Here, ([B]) is a matrix dependent on the Onsager coefficients and mole fractions [22]. The thermodynamic factor is a measure of the non-ideality of the mixture and can be computed from MD simulations using methods like Kirkwood-Buff integration [22].