Evaluating GAFF Force Field Diffusion Performance: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomolecular Simulation

This article provides a critical evaluation of the General AMBER Force Field (GAFF) for predicting diffusion coefficients and other transport properties in biomolecular simulations.

Evaluating GAFF Force Field Diffusion Performance: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomolecular Simulation

Abstract

This article provides a critical evaluation of the General AMBER Force Field (GAFF) for predicting diffusion coefficients and other transport properties in biomolecular simulations. Targeting researchers and professionals in drug development, we explore GAFF's foundational principles, methodological application for calculating shear viscosity and self-diffusion, common pitfalls in overestimating transition temperatures, and systematic optimization strategies. Through comparative analysis with force fields like OPLS-AA and CHARMM36, and validation against experimental data for systems including liquid crystals, lipids, and ether-based membranes, this guide synthesizes best practices for obtaining reliable diffusion metrics crucial for modeling membrane permeability and drug solubility.

Understanding GAFF: Design Philosophy and Core Limitations for Dynamics

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations are indispensable in computational drug discovery, providing atomic-level insights into the behavior of biomolecular systems. The accuracy of these simulations is fundamentally governed by the force field—the set of empirical functions and parameters that describe the potential energy of a system as a function of its atomic coordinates. The General AMBER Force Field (GAFF) is a widely adopted general force field designed for simulating small organic molecules, particularly drug-like molecules, and is compatible with the AMBER family of biomolecular force fields. This guide provides a detailed examination of the GAFF formalism, objectively comparing its performance against other prominent force fields in the context of molecular diffusion and conformational sampling, supported by experimental data and methodological protocols.

The GAFF Formalism: A Detailed Breakdown

The GAFF potential energy function follows a standard molecular mechanics formulation, decomposing the total energy into contributions from bonded and non-bonded interactions. The total energy is expressed as:

( E{Total} = E{Bonded} + E_{Non-Bonded} )

Bonded Interaction Potentials

Bonded interactions in GAFF describe the energy associated with the covalent structure of the molecule and are calculated as the sum of bond stretching, angle bending, and torsional dihedral terms.

Bond Stretching: This term describes the energy required to stretch or compress a chemical bond between two atoms from its equilibrium length. It is typically modeled using a harmonic potential: ( E{bond} = \sum{bonds} kr (r - r{eq})^2 ) where ( kr ) is the force constant and ( r{eq} ) is the equilibrium bond length.

Angle Bending: This term represents the energy associated with the deformation of the angle between three bonded atoms. It also uses a harmonic potential: ( E{angle} = \sum{angles} k{\theta} (\theta - \theta{eq})^2 ) where ( k{\theta} ) is the angle force constant and ( \theta{eq} ) is the equilibrium bond angle.

Torsional Dihedrals: This term describes the energy barrier for rotation around a central bond connecting four atoms. It is modeled using a periodic cosine function: ( E{torsion} = \sum{dihedrals} \frac{Vn}{2} [1 + \cos(n\phi - \gamma)] ) where ( Vn ) is the torsional barrier height, ( n ) is the periodicity, ( \phi ) is the dihedral angle, and ( \gamma ) is the phase shift. The GAFF potential energy function includes separate terms for proper and improper dihedrals, the latter used to maintain planarity in certain chemical groups.

The parameters for these bonded terms ( ( kr ), ( r{eq} ), ( k{\theta} ), ( \theta{eq} ), ( V_n ), ( n ), ( \gamma ) ) are derived from fits to quantum mechanical (QM) calculations. GAFF uses the restrained electrostatic potential (RESP) method to derive partial atomic charges, which involves fitting atomic charges to reproduce the QM-derived electrostatic potential around the molecule [1] [2].

Non-Bonded Interaction Potentials

Non-bonded interactions in GAFF describe the energy between atoms that are not directly bonded or are separated by more than three bonds. They are the sum of van der Waals and electrostatic interactions.

Van der Waals Interactions: These attractive and repulsive forces are modeled using the Lennard-Jones 12-6 potential: ( E{vdW} = \sum{i

{ij} \left[ \left(\frac{\sigma{ij}}{r{ij}}\right)^{12} - \left(\frac{\sigma{ij}}{r{ij}}\right)^{6} \right] ) where ( \epsilon{ij} ) is the well depth, ( \sigma{ij} ) is the collision diameter, and ( r{ij} ) is the distance between atoms ( i ) and ( j ). The parameters for unlike atoms are typically determined using combination rules like the Lorentz-Berthelot rules. }>Electrostatic Interactions: These are calculated using a Coulomb potential between fixed partial charges on each atom: ( E{elec} = \sum{i

i qj}{4\pi\epsilon0 r{ij}} ) where ( qi ) and ( qj ) are the partial charges on atoms ( i ) and ( j ), and ( \epsilon_0 ) is the permittivity of free space. }>

For long-range interactions, GAFF simulations typically employ particle mesh Ewald (PME) summation for electrostatics and may apply continuum model corrections for van der Waals interactions beyond the cutoff distance [3].

Performance Comparison with Other Force Fields

The performance of GAFF has been extensively benchmarked against other general force fields such as OPLS, CHARMM, and MMFF94 in various contexts, including conformational geometry, thermodynamic properties, and diffusion.

Conformational Geometry and Energetics

A large-scale study comparing optimized molecular geometries across multiple force fields highlighted significant differences in their predictions. The study analyzed over 2.7 million drug-like molecules from the eMolecules database, optimizing each structure with GAFF, GAFF2, MMFF94, MMFF94S, and SMIRNOFF99Frosst [4]. Geometric differences were quantified using Torsion Fingerprint Deviation (TFD) and TanimotoCombo.

Table 1: Force Field Pairwise Comparison Based on Geometric Differences

| Force Field Pair | Number of Difference Flags (High TFD) | Number of Similarity Flags (Low TFD) |

|---|---|---|

| GAFF vs. GAFF2 | 87,829 | 2,577,081 |

| GAFF vs. MMFF94 | 153,244 | 2,467,654 |

| GAFF2 vs. SMIRNOFF99Frosst | 305,582 | 2,277,081 |

| MMFF94 vs. MMFF94S | 10,048 | 2,678,568 |

The results indicate that GAFF and GAFF2 produce substantially different geometries for a significant number of molecules, reflecting the impact of GAFF2's reparameterization [4]. The largest number of differences was observed between GAFF2 and the SMIRNOFF99Frosst force field, while the most similar pair was MMFF94 and MMFF94S, which share a common lineage.

Thermodynamic and Transport Properties

The accuracy of GAFF and OPLS force fields was critically assessed in a study of urea crystallization, which tested their ability to reproduce both crystal structures and solution properties [5]. This is a stringent test, as a reliable force field for crystallization must perform well in both solid and liquid phases.

Table 2: Comparison of GAFF and OPLS Performance for Urea Systems

| Property | GAFF Performance | OPLS Performance | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Crystal Lattice Parameters | Reproduced well [5] | Not fully reported | GAFF showed good agreement with experimental crystal structures. |

| Solution Structural Correlations | Not fully reported | Accurately reproduced [5] | OPLS demonstrated strength in modeling the liquid phase. |

| Diffusion Coefficients | Not fully reported | Accurately reproduced [5] | OPLS successfully captured dynamic liquid properties. |

| Overall Recommendation | Suitable for crystal studies | Suitable for solution & combined phases | Two best-performing force fields identified in the study. |

The study concluded that a specific charge-optimized variant of GAFF and the original all-atom OPLS force field showed the best overall performance for urea crystallization studies [5]. This highlights that force field performance is highly system-dependent, and testing against relevant experimental data is crucial.

Diffusion Performance in Lipid Systems

The diffusion of molecules within lipid membranes is a critical property in drug discovery. A specialized force field for bacterial lipids, BLipidFF, was developed and compared to GAFF and other general force fields (CGenFF, OPLS) in simulating mycobacterial membranes [1].

A key finding was that BLipidFF uniquely captured the high tail rigidity and accurately predicted the lateral diffusion coefficient of α-mycolic acid bilayers, showing excellent agreement with Fluorescence Recovery After Photobleaching (FRAP) experiments [1]. While the study does not provide quantitative diffusion rates for GAFF, it implies that the general GAFF force field was insufficient to describe these important membrane properties, which were "poorly described by general force fields" [1]. This underscores a limitation of GAFF when applied to highly specialized and complex chemical systems like unique bacterial lipids, where dedicated parameterization is necessary for accuracy.

Experimental Protocols for Force Field Validation

To ensure the reliability of MD simulations, the force field must be validated against experimentally observable properties. Below are detailed methodologies for key validation experiments cited in this guide.

Protocol for Conformational Geometry Comparison

The large-scale geometry analysis followed this workflow [4]:

- Molecule Curation: A subset of molecules with 25 or fewer heavy atoms was selected from the eMolecules database.

- Energy Minimization: Each molecule's initial 3D structure was optimized (energy-minimized) using each of the five force fields (GAFF, GAFF2, MMFF94, MMFF94S, SMIRNOFF99Frosst) independently.

- Pairwise Comparison: For every molecule, the ten possible pairs of minimized conformers (from different force fields) were compared.

- Metric Calculation: Two size-independent metrics were computed for each pair:

- Torsion Fingerprint Deviation (TFD): A dimensionless number between 0 and 1 that compares all torsional angles in the molecule, with 0 indicating identical conformers.

- TanimotoCombo: A measure of overall 3D shape similarity.

- Flag Assignment: A "difference flag" was assigned to molecule pairs with TFD > 0.20 and TanimotoCombo > 0.50, indicating a meaningful geometric difference likely caused by force field parameterization.

Protocol for Bulk Liquid Property Assessment

The methodology for evaluating force fields for tri-n-butyl phosphate (TBP) is representative for assessing thermodynamic and transport properties [6]:

- System Setup: A simulation box containing a specific number of TBP molecules is built to match the experimental mass density.

- Equilibration: The system is equilibrated in the NPT (isothermal-isobaric) ensemble at the target temperature and pressure until the density and energy stabilize.

- Production Run: A longer MD simulation is performed to collect data for analysis.

- Property Calculation:

- Mass Density: Calculated directly from the simulation box dimensions and total mass.

- Heat of Vaporization (ΔHvap): Calculated as the difference between the average potential energy per molecule in the gas phase and the average potential energy per molecule in the liquid phase, plus the term ( RT ).

- Shear Viscosity: Calculated using equilibrium (Green-Kubo formalism) or non-equilibrium (NEMD-SLLOD) methods by relating stress and strain.

- Self-Diffusion Coefficient: Calculated from the mean-squared displacement (MSD) of the molecules' center of mass over time using the Einstein relation.

Force Field Validation Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table details key software and computational tools used in force field development and validation, as referenced in the studies.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Tools for Force Field Studies

| Tool Name | Type/Function | Relevance to Force Field Research |

|---|---|---|

| Antechamber | Software Tool | Used to automatically assign GAFF atom types and parameters, and calculate AM1-BCC partial charges for small molecules [5]. |

| Gaussian & GaussView | Quantum Chemistry Software | Used for high-level QM calculations (e.g., geometry optimization, electrostatic potential derivation) that serve as the target data for force field parameterization [1]. |

| Multiwfn | Wavefunction Analysis | Employed for RESP charge fitting from QM-calculated electrostatic potentials, a common method for deriving partial charges in AMBER/GAFF [1]. |

| RDKit | Cheminformatics Library | Used for generating initial 3D molecular conformations from SMILES strings, which are often used as starting points for QM calculations or MD simulations [2]. |

| GROMACS | Molecular Dynamics Engine | A highly popular MD software package that supports the AMBER/GAFF force fields and is used for running production simulations and calculating properties [3] [7]. |

| Checkmol | Functional Group Identification | Used to programmatically identify functional groups in large molecular datasets, helping to correlate force field performance with specific chemical motifs [4]. |

| 4-Propoxycinnamic Acid | 3-(4-Propoxyphenyl)acrylic Acid|CAS 69033-81-4 | |

| 11-Aminoundecanoic acid | 11-Aminoundecanoic Acid|Nylon-11 Monomer | 11-Aminoundecanoic acid is a key monomer for bio-based Nylon-11 and organogelators. This product is For Research Use Only. Not for human or animal use. |

The General AMBER Force Field (GAFF) provides a robust and widely used framework for simulating drug-like molecules. Its formalism, which carefully partitions energy into bonded and non-bonded components parameterized from QM data, offers a good balance between computational efficiency and accuracy for a broad chemical space. Performance comparisons show that GAFF is highly competent for studying molecular crystals and is a solid choice for general organic molecules. However, its performance relative to OPLS, CHARMM, or specialized force fields can vary significantly depending on the system and property of interest. For critical applications like diffusion in complex membranes or accurate solution-phase behavior, researchers are advised to consult recent benchmarks and consider specialized or next-generation force fields where available. The ongoing development of data-driven parameterization methods promises to further expand the accuracy and chemical coverage of force fields like GAFF in the future.

The accurate prediction of phase transition temperatures is a critical challenge in the computational design and screening of liquid crystalline materials. Fully atomistic molecular dynamics (MD) simulations offer the potential to link molecular chemical structure to mesophase stability and transition behavior. However, the predictive power of these simulations is fundamentally tied to the force field employed. Among general-purpose force fields, the General AMBER Force Field (GAFF) has been widely adopted for simulating organic molecules. Nevertheless, a consistent and significant systematic error has been documented in its application to liquid crystals (LCs): a pronounced overestimation of nematic-isotropic transition temperatures (TNI) [8]. This guide provides a objective performance comparison of GAFF against other force fields and optimized variants, detailing the specific nature of this error, the methodologies used to diagnose it, and the solutions developed to address it.

Performance Comparison of Force Fields

Extensive benchmarking against experimental data reveals how different force fields handle key thermodynamic properties relevant to liquid crystals and other soft materials. The systematic error in transition temperature prediction is part of a broader pattern ofåå·® in GAFF's description of condensed-phase properties.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Force Fields for Organic Systems

| Force Field | System | Predicted Property | Performance Summary | Key Systematic Error |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GAFF (Standard) [8] [9] | Liquid Crystal Mesogens (e.g., Benzeneester) | Nematic-Istotropic Transition Temp. (TNI) | Overestimation by ~60 °C to >100 °C [8] | Significant overestimation of mesophase stability |

| GAFF (Standard) [9] | Diisopropyl Ether (DIPE) Liquid Membrane | Density & Shear Viscosity | Density overestimation by 3-5%; Viscosity overestimation by 60-130% [9] | Overestimation of liquid density and intermolecular friction |

| GAFF-LCFF (Optimized) [8] | Liquid Crystal Mesogens (e.g., Benzeneester) | Nematic-Istotropic Transition Temp. (TNI) | Prediction within 5 °C of experimental value [8] | Dramatic improvement via reparameterization |

| OPLS-AA/CM1A [9] | Diisopropyl Ether (DIPE) Liquid Membrane | Density & Shear Viscosity | Performance similar to standard GAFF [9] | Overestimation of density and viscosity |

| CHARMM36 [9] | Diisopropyl Ether (DIPE) Liquid Membrane | Density, Viscosity, Interfacial Tension | Accurate density and viscosity; good agreement for solubility & partitioning [9] | Good overall accuracy for thermodynamic and transport properties |

| COMPASS [9] | Diisopropyl Ether (DIPE) Liquid Membrane | Density, Viscosity, Interfacial Tension | Quite accurate density and viscosity; less accurate for mutual solubility [9] | Good for pure liquid properties, less accurate for mixture thermodynamics |

Beyond transition temperatures, analysis of Hydration Free Energy (HFE) calculations for drug-like molecules reveals other functional group-specific systematic errors in GAFF. For instance, molecules containing nitro-groups are under-solubilized, while those with carboxyl groups are over-solubilized in aqueous medium [10]. Another study identified systematic errors for molecules containing chlorine, bromine, iodine, and phosphorus [11], suggesting underlying issues with the Lennard-Jones parameters for these elements.

Experimental Protocols for Diagnosing Transition Temperature Error

The identification and correction of GAFF's overestimation of TNI rely on a rigorous comparison between simulation results and experimental data, following a clear workflow.

Diagram 1: Workflow for diagnosing GAFF transition temperature error.

Step 1: Obtain Experimental Reference Data

The protocol begins with selecting a well-characterized thermotropic liquid crystal molecule for which the experimental nematic-isotropic clearing point (TNI) is known from techniques such as differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) or polarizing optical microscopy [8]. An example is 1,3-benzenedicarboxylic acid,1,3-bis(4-butylphenyl)ester.

Step 2: Build Molecular Model and Assign Parameters

- Model Construction: A 3D model of the mesogen is built.

- Parameter Assignment: Atom types, partial charges, bonds, angles, dihedrals, and Lennard-Jones parameters are assigned according to the standard GAFF protocol [8]. Partial charges are typically derived using the AM1-BCC method [10].

- System Setup: Multiple copies of the molecule (often several hundred) are placed in an initial simulation box to model the bulk liquid crystalline phase.

Step 3: Perform Molecular Dynamics Simulation

- Software: Simulations are run using MD packages like AMBER, GROMACS, or DL_POLY, which support GAFF [8].

- Protocol: The system is simulated using a constant pressure and temperature (NPT) ensemble over a range of temperatures.

- Analysis: The stability of the nematic phase is monitored by calculating the orientational order parameter. A high order parameter indicates a stable nematic phase; a drop to zero signifies a transition to the isotropic phase. The simulated TNI is identified as the temperature where this transition occurs [8].

Step 4: Quantify Systematic Error

The key diagnostic step is the direct comparison of simulated and experimental TNI values. As evidenced in multiple studies, the standard GAFF force field results in a simulated TNI that is consistently 60 °C to over 100 °C higher than the experimental value [8]. This large positive offset is the hallmark of its systematic error, suggesting an overestimation of the effective attractions between mesogenic molecules.

Optimization Methodology: The Path to Improved Predictions

The systematic error in GAFF can be addressed through a targeted optimization strategy, as demonstrated by the development of the GAFF-LCFF force field. This optimization is a multi-stage process focusing on the key parameters that govern molecular conformation and interaction.

Diagram 2: Optimization workflow for GAFF-LCFF force field.

Fragment-Based Optimization Strategy

Instead of parameterizing entire, complex mesogens at once, the molecule is broken down into smaller, representative fragment molecules (e.g., biphenyl cores, alkyl chains). Parameters are optimized for these fragments and then transferred to the larger mesogen, ensuring better transferability across a wide range of LC structures [8].

Key Parameter Refinement Actions

The optimization primarily targets two classes of parameters:

- Torsional Angle Potentials: Dihedral scans are performed on fragment molecules using high-level Quantum Chemical (QM) calculations (e.g., DFT with B3LYP functional or MP2 theory). The GAFF torsional potential parameters are then optimized to minimize the difference between the QM and molecular mechanics (MM) energy profiles [8].

- Lennard-Jones Parameters: The Lennard-Jones (LJ) parameters, which control van der Waals interactions, are refined to accurately reproduce experimental liquid densities and heats of vaporization (ΔvapH) for the fragment molecules. Achieving an accuracy of better than 1% for density is critical for reasonable transition temperature predictions [8].

This refined force field, referred to as GAFF-LCFF, was shown to predict the TNI of a benchmark mesogen to within 5 °C of the experimental value, an improvement of 60 °C over the standard GAFF [8].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Key Computational Tools and Resources for LC Force Field Research

| Tool / Resource | Function in Research | Specific Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| MD Simulation Software | Engine for running atomistic simulations and calculating properties. | GROMACS [8], AMBER [8], DL_POLY [8], CHARMM [10] (with OpenMM/BLaDE interfaces [10]). |

| General Force Fields | Provides baseline atomistic parameters for organic molecules. | GAFF [8], OPLS-AA [8] [9], CHARMM36 [9], CGenFF [10]. |

| Quantum Chemistry Software | Provides target data for parameter optimization (torsional profiles, electrostatic potentials). | Gaussian09 [8] (for DFT/MP2 calculations). |

| Validation Datasets | Experimental benchmark data for force field validation. | Experimental TNI data for mesogens [8]; FreeSolv database for Hydration Free Energies [10] [11]. |

| Parameter Optimization Tools | Software and scripts for fitting force field parameters to QM and experimental data. | Custom scripts for minimizing χ² between QM and MM energies [8]. |

| Specialized Force Fields | Re-parameterized force fields for specific material classes. | GAFF-LCFF for liquid crystals [8]; AMOEBA+ for polarizable simulations [12]. |

| Sorbitan monododecanoate | Sorbitan monododecanoate, CAS:8028-02-2, MF:C18H34O6, MW:346.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| DecarboxyBiotin-Alkyne | DecarboxyBiotin-Alkyne, MF:C12H18N2OS, MW:238.35 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Impact of Force Field Inaccuracies on Simulated Diffusion Coefficients

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations provide atomistic-level insights into complex processes across chemical, pharmaceutical, and materials sciences. The predictive accuracy of these simulations fundamentally depends on the force fields that model atomic and molecular interactions [5] [1]. This guide objectively compares the performance of various force fields in predicting a critical kinetic property: diffusion coefficients. We focus specifically on the Generalized AMBER Force Field (GAFF) within the broader context of force field research, providing researchers with experimental data and methodologies for informed force field selection.

Force Field Performance Comparison

Quantitative Comparison of Force Fields for Urea Systems

The reproduction of known urea crystal and aqueous solution properties provides a direct comparison between GAFF and Optimized Potential for Liquid Simulations (OPLS) force fields [5]. The table below summarizes key quantitative findings.

Table 1: Performance of different force fields in simulating urea properties.

| Force Field | Crystal Density (g/cm³) | Aqueous Solution Density (g/cm³) | Diffusion Coefficient (10â»âµ cm²/s) | Overall Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GAFF1 (AM1-BCC) | ~1.30 (Underestimate) | Variable accuracy | Variable accuracy | Moderate |

| GAFF2 (AM1-BCC) | ~1.30 (Underestimate) | Variable accuracy | Variable accuracy | Moderate |

| GAFF-D1 (Optimized) | ~1.34 (Improved) | Good agreement | Good agreement | Good |

| GAFF-D3 (Optimized) | ~1.34 (Improved) | Good agreement | Good agreement | Good |

| OPLS-AA (Original) | ~1.34 (Good agreement) | Good agreement | Good agreement | Good |

Two force fields demonstrated the best overall performance for urea crystallization studies: a urea charge-optimized GAFF force field (specifically the D1 and D3 versions) and the original all-atom OPLS force field [5]. These versions showed superior performance in reproducing experimental crystal densities (approximately 1.34 g/cm³) and solution properties.

Broader Force Field Validation for Diffusion Coefficients

Beyond specific molecule tests, large-scale validation studies assess force field performance across chemically diverse liquids. The following table summarizes the performance of the OPLS4 force field in predicting self-diffusion coefficients.

Table 2: OPLS4 force field performance for self-diffusion coefficients across diverse pure liquids [13].

| Metric | Value | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Determination Coefficient (R²) | 0.931 | Excellent correlation with experimental data |

| Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) | 0.213 | Good predictive accuracy |

| Mean Absolute Error (MAE) | Not specified | Good predictive accuracy |

| Concordance Correlation Coefficient (CCC) | Not specified | Good predictive accuracy |

| Number of Data Points | 547 | Comprehensive validation set |

| Temperature Range | Various | Broad applicability |

The OPLS4 force field demonstrated excellent correlation with experimental values across 547 measurements of diverse pure liquids, with a determination coefficient of 0.931 between calculated and experimental logarithmic self-diffusion coefficients [13]. This demonstrates that modern force fields can achieve remarkable accuracy for molecular transportation properties.

Experimental Protocols for Force Field Validation

Comprehensive Testing Protocol for Crystallization Studies

A rigorous validation protocol for force fields intended for crystallization simulations should evaluate both solid and solution properties [5]:

Crystal Property Assessment

- Lattice Parameters: Compare simulated crystal lattice parameters against experimental X-ray diffraction data

- Cohesive Energy: Calculate and compare energy of sublimation

- Thermal Stability: Assess melting point temperature through solid-liquid interface simulations

Solution Property Validation

- Diffusion Coefficients: Calculate molecular diffusion coefficients using mean square displacement (MSD) analysis

- Solution Structure: Evaluate radial distribution functions to assess structural correlations

- Solvation Free Energy: Determine free energy of hydration through thermodynamic calculations

This dual-phase approach is crucial because force fields that perform well for solution properties may inadequately reproduce crystal characteristics, and vice versa [5].

Diffusion Coefficient Calculation Methodology

The standard approach for calculating diffusion coefficients in MD simulations uses the Einstein relation, which relates diffusion coefficient to the slope of the mean square displacement (MSD) versus time [13]:

Production Simulation

- Run MD simulations in the isothermal-isobaric (NPT) ensemble

- Maintain appropriate temperature and pressure using thermostats and barostats

- Use a timestep of 1-2 fs for accurate integration of equations of motion

- Simulate for sufficient duration (40-150 ns depending on system diffusivity)

MSD Analysis

- Calculate MSD of molecules' center-of-mass from trajectories: ( \text{MSD}(Ï„) = \langle |r(t+Ï„) - r(t)|^2 \rangle )

- Average MSDs of all molecules in the simulation system

- Use appropriate lag time ranges (12-20 ns for highly diffusive samples, 45-75 ns for lowly diffusive samples)

Diffusion Coefficient Extraction

- Calculate diffusion coefficient as one-sixth of the slope of MSD versus lag time: ( D = \lim{t \to \infty} \frac{1}{6t} \langle |ri(t) - r_i(0)|^2 \rangle )

- Apply linear regression using least-squares technique [13]

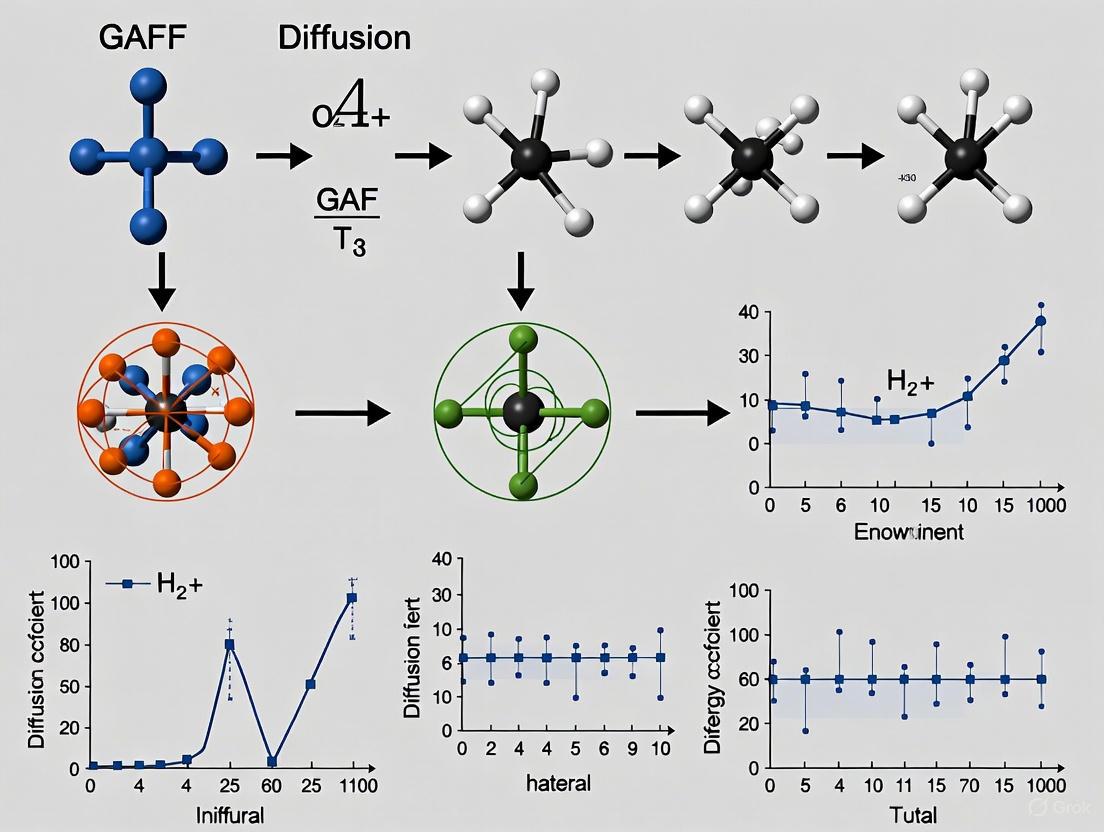

Figure 1: Workflow for comprehensive force field validation covering both crystal and solution properties.

Table 3: Essential tools and resources for force field development and validation.

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application in Research |

|---|---|---|

| AMBER Tools | Parameter generation for organic molecules | Provides GAFF parameters and Antechamber for charge calculation [5] |

| RESP Charge Fitting | Deriving partial atomic charges | Quantum mechanics-based charge parameterization [1] |

| LAMMPS | Molecular dynamics simulation | Large-scale atomic/molecular massively parallel simulator [14] |

| Desmond | Molecular dynamics simulation | Commercial MD software with system building capabilities [13] |

| Quantum Mechanics (QM) | High-level electronic structure calculation | Reference data for force field parameterization [1] |

| PFG-NMR | Experimental diffusion coefficient measurement | Validation standard for simulated diffusion coefficients [13] |

Force field selection critically impacts the accuracy of simulated diffusion coefficients. For molecular systems like urea, charge-optimized versions of GAFF and the original all-atom OPLS demonstrate the best overall performance in reproducing both crystal and solution properties [5]. Comprehensive validation across diverse chemical systems shows that modern force fields like OPLS4 can achieve excellent correlation (R² = 0.931) with experimental diffusion coefficients [13]. Researchers should adopt rigorous testing protocols that evaluate both solid and solution properties when selecting force fields for crystallization studies, and consider specialized parameterization for complex systems where general force fields show limitations.

Comparative Performance with OPLS-AA and CHARMM on Density and Enthalpy

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations are indispensable tools in computational chemistry and drug development, providing atomistic insights into complex systems. The accuracy of these simulations is critically dependent on the force field—a mathematical model describing interatomic interactions [15]. Among the many available force fields, the Generalized Amber Force Field (GAFF), Optimized Potentials for Liquid Simulations All-Atom (OPLS-AA), and Chemistry at Harvard Macromolecular Mechanics (CHARMM) are widely used for simulating organic molecules and biomolecular systems [5] [1].

This guide provides an objective comparison of the performance of these force fields in predicting two fundamental thermodynamic properties: density and enthalpy of vaporization (ΔHvap). These properties are essential for validating force fields as they are experimentally accessible and reflect the balance of intermolecular interactions in condensed phases [16]. Accurate prediction of density indicates proper volume packing, while enthalpy of vaporization reflects the overall energy of intermolecular interactions [16].

Performance Data Comparison

Comprehensive Benchmark of Organic Liquids

A landmark study evaluating 146 organic liquids provides critical insights into force field performance for liquid-state properties [16]. The table below summarizes the overall findings for density and enthalpy of vaporization predictions.

Table 1: Overall Performance for Organic Liquid Properties [16]

| Force Field | Density Accuracy | Enthalpy of Vaporization Accuracy | Notable Strengths and Weaknesses |

|---|---|---|---|

| OPLS-AA | Good performance | Good performance | Optimized for organic liquids; performs somewhat better than GAFF overall. |

| GAFF | Moderate performance | Moderate performance | Shows significant issues with surface tension and dielectric constants. |

| CHARMM (CGenFF) | Comparable to OPLS/AA and GAFF | Comparable to OPLS/AA and GAFF | Parameters from CGenFF study included for reference; shows similar performance. |

Specific System Performance

Different force fields can exhibit varying performance depending on the specific molecular system being simulated. The following table compiles quantitative data from studies on specific materials.

Table 2: Performance on Specific Molecular Systems

| System | Force Field | Density Performance | Enthalpy of Vaporization Performance | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organic Liquids (Benchmark) | OPLS-AA | Good agreement with experiment | Good agreement with experiment | [16] |

| Organic Liquids (Benchmark) | GAFF | Moderate agreement with experiment | Moderate agreement with experiment | [16] |

| Asphalt Materials | CHARMM | Good prediction of density | Not specifically reported | [17] |

| Asphalt Materials | OPLS | Good prediction of density | Not specifically reported | [17] |

| Asphalt Materials | GAFF | Worst performer among tested force fields | Not specifically reported | [17] |

| One Model Asphalt Mixture | CHARMM vs OPLS-aa | Very close density results | Not specifically reported | [18] |

Experimental Protocols for Force Field Benchmarking

The reliable assessment of force field performance for density and enthalpy of vaporization follows standardized computational protocols.

System Preparation and Simulation

The typical workflow for benchmarking force fields involves multiple stages to ensure reliability and statistical significance [16].

Figure 1: Standard workflow for benchmarking force field performance on liquid properties.

Key Methodological Steps [16]:

Molecule Selection and Preparation: A set of organic molecules for which experimental density and ΔHvap are known at room temperature is selected. Molecular models are built and optimized using quantum chemical methods at the Hartree-Fock level with the 6-311G basis set.

Force Field Parameterization: Topologies for each force field (GAFF, OPLS-AA, CHARMM) are generated using their respective standard protocols and tools (e.g., Antechamber for GAFF, GROMACS tools for OPLS-AA). Partial charges are derived using methods specific to each force field.

System Construction: Simulation boxes are constructed with a large number of molecules (typically 1000) to minimize size effects and placed in a cubic box with periodic boundary conditions.

Energy Minimization and Equilibration: Initial configurations are energy-minimized to relax unphysical contacts. Systems are then equilibrated in the NVT (constant Number, Volume, Temperature) and NPT (constant Number, Pressure, Temperature) ensembles to reach the target temperature and pressure.

Production Simulation and Analysis: Long molecular dynamics production runs are performed in the NPT ensemble. Density is calculated directly from the simulation volume. The enthalpy of vaporization is computed using the formula: ΔHvap =

- + RT, where and are the average potential energies of a single molecule in the gas phase and in the liquid phase, respectively, R is the gas constant, and T is the temperature [16].

Key Considerations for Accurate Benchmarking

- System Size: The number of atoms in the model significantly impacts the stability and accuracy of predicted properties. Larger systems (e.g., thousands of molecules) generally yield more stable and reliable results [17].

- Statistical Uncertainty: It is crucial to run simulations for sufficient time to ensure proper sampling of phase space. Properties should be averaged over multiple independent trajectories or long simulation times to obtain reliable statistics.

- Electrostatic Treatment: Particle Mesh Ewald (PME) summation is typically used for handling long-range electrostatic interactions, which is critical for obtaining accurate energies and densities.

- Temperature and Pressure Control: Thermostats (e.g., Nosé-Hoover) and barostats (e.g., Parrinello-Rahman) that produce correct ensembles should be employed.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Tool/Reagent | Function in Force Field Benchmarking |

|---|---|

| GROMACS | A high-performance molecular dynamics package with GPU acceleration used for running simulations and analyzing results. [17] |

| Gaussian | A quantum chemistry program used for initial geometry optimization and charge derivation at various levels of theory (e.g., HF/6-311G). [16] |

| Antechamber | A toolkit used to automatically generate GAFF force field parameters and AM1-BCC charges for organic molecules. [16] [5] |

| CHARMM General Force Field (CGenFF) | A program used to obtain CHARMM force field parameters for molecules not originally in the force field. [18] |

| OpenBabel | A chemical toolbox used to handle chemical data and file format conversion in preparation for simulations. [16] |

| AUL-cc-pVXZ Basis Sets | High-quality basis sets used in composite quantum chemistry methods to generate accurate reference data for force field validation. [19] |

| Croscarmellose sodium | Croscarmellose sodium, CAS:74811-65-7, MF:C8H16NaO8, MW:263.20 g/mol |

| 2-Chlorocinnamic acid | 2-Chlorocinnamic acid, CAS:4513-41-1, MF:C9H7ClO2, MW:182.60 g/mol |

The comparative analysis of GAFF, OPLS-AA, and CHARMM force fields reveals that OPLS-AA generally shows good performance for predicting density and enthalpy of vaporization for organic liquids, often outperforming GAFF in comprehensive benchmarks [16]. The CHARMM force field demonstrates comparable accuracy to OPLS-AA in many contexts, particularly for biomolecular and complex systems like asphalt [18] [17].

However, performance can be system-dependent. For instance, in asphalt systems, GAFF was identified as the worst performer for condensed-phase properties, while both CHARMM and OPLS showed good and similar performance for density prediction [18] [17]. This underscores the importance of validating a force field for the specific class of compounds under investigation. When selecting a force field for drug development or materials science applications, researchers should consult benchmarks relevant to their specific molecular systems and target properties.

Practical Protocols for Diffusion Coefficient Calculation with GAFF

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations are an indispensable tool for investigating dynamic properties of liquids, with the self-diffusion coefficient (D) representing a fundamental transport property crucial for understanding molecular behavior in various environments. Within equilibrium MD frameworks, the Green-Kubo formalism establishes a direct connection between macroscopic transport coefficients and microscopic dynamics through time-correlation functions. This approach calculates the self-diffusion coefficient by integrating the velocity autocorrelation function (VACF) over time, providing a powerful alternative to methods based on mean-squared displacement (MSD). For researchers in drug development and materials science, accurate prediction of diffusion coefficients informs critical processes including membrane permeation, protein aggregation, and solvent effects on molecular mobility.

The choice of force field significantly impacts the accuracy of predicted properties. The General AMBER Force Field (GAFF) has emerged as a widely used parameter set for biomolecular systems and organic molecules. This guide objectively compares GAFF's performance against alternative force fields in predicting self-dusion coefficients, providing supporting experimental data and detailed methodological protocols to inform research applications.

Theoretical Foundation of the Green-Kubo Formalism

The Green-Kubo relation represents a cornerstone of linear response theory, connecting equilibrium fluctuations to transport coefficients. For self-diffusion, this formalism derives from the analysis of molecular velocity correlations over time.

Mathematical Formulation

The Green-Kubo formula for the self-diffusion coefficient is expressed as:

[ D = \frac{1}{3} \int_{0}^{\infty} \langle \vec{v}(t) \cdot \vec{v}(0) \rangle dt ]

where (\vec{v}(t)) represents the molecular velocity vector at time (t), and the angle brackets denote the ensemble average over molecules and time origins. This integral of the velocity autocorrelation function (VACF) embodies the molecular memory of initial velocity conditions, with more persistent correlations indicating lower diffusivity.

In practical MD implementations, the integral is computed up to a finite time cutoff ((t_c)) where the VACF decays to zero or exhibits minimal further contribution. Challenges arise from statistical noise at long times, requiring careful selection of integration limits to balance accuracy and precision. The Einstein relation, which calculates D from the slope of mean-squared displacement versus time, provides an equivalent approach that often demonstrates superior convergence properties in practical applications.

Performance Comparison of Force Fields

The accuracy of diffusion coefficient predictions depends critically on the force field selection. Recent systematic evaluations provide quantitative comparisons of prevalent parameter sets.

GAFF Performance Metrics for PEG Oligomers

Comprehensive assessment of GAFF for polyethylene glycol (PEG) oligomers demonstrates exceptional agreement with experimental measurements across multiple thermophysical properties [20]. For a PEG tetramer, GAFF reproduces experimental data within 5% for density, 5% for diffusion coefficient, and 10% for viscosity at 328 K [20]. This accuracy extends across oligomer lengths from n=2 to n=7, confirming GAFF's robust parameterization for this important class of compounds.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of GAFF for PEG Oligomers (n=2-7) at 328 K

| Property | Agreement with Experiment | Remarks |

|---|---|---|

| Density | Within 5% for tetramer | Consistent across oligomer lengths |

| Self-diffusion Coefficient | Within 5% for tetramer | Superior to alternative force fields |

| Shear Viscosity | Within 10% for tetramer | Outperforms OPLS significantly |

| Thermal Conductivity | Excellent agreement | Reproduces experimental trends |

Comparative Force Field Accuracy

Direct comparison against the OPLS force field reveals GAFF's superior performance for dynamic properties [20]. For the same PEG tetramer systems, OPLS demonstrates deviations exceeding 80% for diffusion coefficients and 400% for viscosity, highlighting substantial limitations in its parameterization for transport properties. This performance differential underscores the critical importance of force field selection for diffusion studies.

Beyond neat systems, GAFF achieves strong predictive accuracy for organic solutes in aqueous solution, with an average unsigned error of 0.137 ×10â»âµ cm²/s and root-mean-square error of 0.171 ×10â»âµ cm²/s across diverse molecular systems [21]. Furthermore, GAFF maintains excellent correlation with experimental trends (R² = 0.834) for organic compounds in non-aqueous solutions [21].

Computational Methodologies

Reproducible calculation of diffusion coefficients via Green-Kubo requires careful attention to simulation protocols and analysis procedures.

Simulation Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the complete computational workflow for Green-Kubo diffusion coefficient calculation:

Detailed Simulation Protocols

System Setup: Initial configurations typically employ the PACKMOL software to construct simulation boxes containing 100-1000 molecules, depending on molecular size and computational resources. Periodic boundary conditions are applied in all three dimensions to minimize finite-size effects [20] [21].

Force Field Parameters: GAFF utilizes the following non-bonded interaction parameters for PEG oligomers [20]:

Table 2: GAFF Non-bonded Interaction Parameters for PEG

| Chemical Group | Atom | ε (K) | σ (Å) | q (e) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hydroxyl (–O–H) | O | 105.85 | 3.07 | -0.65 |

| Hydroxyl (–O–H) | H | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.42 |

| Ether (–CH₂–O–) | C | 55.05 | 3.40 | 0.05 |

| Ether (–CH₂–O–) | H | 7.90 | 2.47 | 0.09 |

| Ether (–CH₂–O–) | O | 85.55 | 3.00 | -0.34 |

Electrostatic Treatments: Partial atomic charges derived from density functional theory (DFT) calculations using the B3LYP functional and 6-311+G(d,p) basis set provide optimal accuracy. Multiple charge models (CM5, Hirshfeld, Mulliken, ESP) can be evaluated for system-specific optimization [20].

Simulation Parameters: Production simulations typically employ:

- Integration time step: 1-2 fs

- Temperature: 328 K (or system-specific)

- Pressure: 1 atm (for preliminary equilibration)

- Non-bonded cutoffs: 8-12 Ã… with particle-particle particle-mesh (PPPM) for long-range electrostatics

- Trajectory saving frequency: 10-100 fs for velocity data

Equilibration Criteria: Systems must achieve convergence in potential energy, density, and temperature before production phases. Typical equilibration durations range from 0.5-5 ns, depending on system size and viscosity.

Green-Kubo Implementation

The velocity autocorrelation function is computed as:

[ C(t) = \frac{1}{N} \sum{i=1}^{N} \langle \vec{v}i(t0 + t) \cdot \vec{v}i(t0) \rangle{t_0} ]

where N is the number of molecules, and the average is over time origins (tâ‚€). The self-diffusion coefficient is then obtained from the integral:

[ D = \frac{1}{3} \int{0}^{tc} C(t) dt ]

The integration upper limit (t_c) must be selected to ensure complete VACF decay while avoiding excessive noise. Multiple independent simulations (5-10 replicates) significantly enhance statistical accuracy through ensemble averaging [21].

The Researcher's Toolkit

Successful implementation of Green-Kubo calculations requires specific computational tools and analytical approaches.

Essential Research Reagents and Software

Table 3: Essential Tools for Green-Kubo Diffusion Studies

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function |

|---|---|---|

| MD Engines | LAMMPS [20], GROMACS, NAMD | Core simulation execution |

| Force Fields | GAFF [20], OPLS [20], CHARMM | Molecular interaction potentials |

| System Building | PACKMOL, Moltemplate | Initial configuration generation |

| Quantum Chemistry | Gaussian 09 [20], ORCA | Partial charge derivation |

| Trajectory Analysis | MDTraj, VMD [22], MDAnalysis | VACF calculation and property extraction |

| Visualization | VMD [22], PyMol | Structural analysis and validation |

| Limocitrin-3-rutinoside | Limocitrin-3-rutinoside, CAS:79384-27-3, MF:C29H34O17, MW:654.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| trans-2-Pentenoic acid | (2E)-Pent-2-enoic acid|trans-2-Pentenoic Acid | Get (2E)-Pent-2-enoic acid (FEMA 4193), a flavor agent found in banana and beer. For Research Use Only. Not for human consumption. |

Specialized Methodologies for Challenging Systems

For systems with slow diffusion or complex confinement effects, specialized approaches enhance sampling efficiency:

Hybrid Methodologies: Combining MD with kinetic Monte Carlo (kMC) algorithms accelerates diffusion coefficient prediction for systems with low diffusivity (D < 10â»â¸ cm²/s) [23]. The TuTraSt algorithm analyzes potential energy landscapes to identify transition states and hopping rates, achieving >5000-fold speedup compared to brute-force MD for methane diffusion in zeolites [23].

Machine Learning Enhancement: Recent approaches employ clustering algorithms to process anomalous MSD-t data, particularly beneficial for nano-confined systems where normal diffusion assumptions break down [22]. These methods effectively extract diffusion coefficients from noisy trajectories while providing algorithmic enhancements for property calculation.

The Green-Kubo formalism within equilibrium MD simulations provides a rigorous framework for predicting self-diffusion coefficients from molecular velocities. Comprehensive validation studies demonstrate that the GAFF force field achieves exceptional accuracy across diverse molecular systems, particularly for PEG oligomers where it significantly outperforms alternatives like OPLS. Successful implementation requires careful attention to simulation protocols, including proper system equilibration, sufficient sampling duration, and appropriate integration limits for the velocity autocorrelation function.

For research applications in drug development and materials science, GAFF offers a compelling combination of broad applicability and quantitative accuracy, making it an excellent choice for predicting diffusion coefficients in organic compounds and biomolecular systems. Future methodology developments will likely focus on enhanced sampling techniques, machine learning-assisted analysis, and continued refinement of force field parameters to further improve predictive accuracy for challenging systems.

The accurate prediction of shear viscosity is a critical challenge in molecular dynamics (MD), with direct implications for fields ranging from drug development to lubricant design. Within Non-Equilibrium Molecular Dynamics (NEMD), the SLLOD algorithm stands as a primary methodology for simulating planar Couette flow and directly calculating shear viscosity. This approach explicitly imposes a shear field on the system, allowing viscosity to be computed from the resulting stress-strain relationship according to the formula: η = ⟨τ_αβ⟩ / γ̇, where ⟨τ_αβ⟩ is the ensemble-averaged shear stress and γ̇ is the applied shear rate [24]. The SLLOD algorithm, when combined with the appropriate thermostating strategy, generates a reliable shearing deformation essential for studying viscous behavior under a wide range of conditions.

This guide provides a comparative analysis of the SLLOD method against alternative computational approaches, with a specific focus on its performance in conjunction with various force fields, including the Generalized Amber Force Field (GAFF). The evaluation of transport properties like viscosity and self-diffusion coefficients remains a significant test for any force field's predictive power [6]. Understanding the capabilities and limitations of different methodologies is essential for researchers and scientists selecting the most appropriate computational tools for their specific applications.

Methodological Comparison: SLLOD vs. Alternative MD Approaches

Several distinct methodologies exist within MD for calculating shear viscosity, each with its own theoretical basis, practical implementation, and scope of applicability. The following table provides a structured comparison of the primary techniques.

Table 1: Comparison of Primary Molecular Dynamics Methods for Shear Viscosity Calculation

| Method | Theoretical Basis | Key Implementation | Representative Applications | Inherent Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SLLOD (NEMD) | Newton's equations with a non-Hamiltonian field; direct stress-strain relationship [6] [25] | Imposes a homogeneous shear rate; uses a Doll's tensor Hamiltonian and compatible thermostat (e.g., Nosé-Hoover) [25] | Studying shear thinning in glycerol [25]; simulating lubricants under extreme pressure [24] | High strain rates needed can perturb system beyond Newtonian plateau; pressure-viscosity coefficient discrepancies [25] |

| Green-Kubo (EMD) | Fluctuation-dissipation theorem; integrates stress autocorrelation function (SACF) at equilibrium [6] [25] | Time-integral of the SACF: η = (V/k_B T) ∫ ⟨P_αβ(t) P_αβ(0)⟩ dt [25] | Validating force fields for organic liquids (OPLS, GAFF) [26]; calculating bulk viscosity [26] | Requires long simulation times for SACF convergence; sensitive to statistical noise [25] |

| Confined NEMD | Direct shear stress measurement in a confined geometry [24] | Fluid confined between explicit solid walls; shear stress measured on wall or fluid atoms [24] | Investigating nanoconfined lubricants [24]; studying surface-lubricant interface effects [24] | Film thickness effects can deviate from bulk viscosity; complex setup with explicit walls [24] |

| Fast Evaluation Techniques | Empirical relationships linking viscosity to short-time correlation functions [27] | Uses short MD runs to compute shear modulus, then empirical model (e.g., van Velzen) for viscosity [27] | High-throughput screening of electrolyte solutions [27]; exhaustive search for materials with desired properties [27] | Relies on parameter fitting; accuracy may be system-dependent [27] |

The choice between these methods involves a critical trade-off. SLLOD offers the advantage of direct non-equilibrium response but often at shear rates many orders of magnitude higher than experimental conditions. This can lead to artifacts, such as the under-prediction of the pressure-viscosity coefficient observed in glycerol simulations [25]. In contrast, while the Green-Kubo method operates at equilibrium, it can suffer from poor convergence, requiring extensive sampling to obtain a reliable result. For high-throughput screening, fast evaluation techniques that leverage short MD simulations and empirical models provide a computationally cheap alternative, though they may sacrifice some accuracy [27] [28].

Performance Benchmarking of Force Fields

The accuracy of any MD method is contingent upon the force field used to describe atomic interactions. The predictive performance for transport properties like shear viscosity and self-diffusion coefficients is a key differentiator among force fields.

Table 2: Force Field Performance for Transport Properties

| Force Field | Reported Performance for Shear Viscosity | Reported Performance for Self-Diffusion | Best Use-Case Scenarios |

|---|---|---|---|

| GAFF (Generalized Amber) | Thermodynamic properties well-predicted; transport properties systematically under-predicted [6] [26] | Systematically over-predicted (under-predicted viscosity implies faster dynamics) [6] | Studies where accurate thermodynamic properties (density, heat of vaporization) are priority [6] |

| OPLS/OPLS2005 | Viscosity under-predicted; best combined deviation (62.6%) with polarization [6] | Under-predicted, but best overall transport property performer among tested force fields for TBP [6] | Organic liquid environments; systems where a balance of thermodynamic and transport accuracy is needed [6] |

| L-OPLS-AA | Used in confined NEMD; shows layering near surfaces; deviations from bulk at small film thicknesses [24] | Information not specified in search results. | Confined systems and interfaces; non-reactive hydrocarbon lubricants [24] |

| ReaxFF (Reactive) | Used in confined NEMD; shows stronger lubricant layering near surfaces than L-OPLS-AA [24] | Information not specified in search results. | Systems where chemical reactivity, bond breaking/formation, or complex surface interactions are important [24] |

A comprehensive study on liquid tri-n-butyl phosphate (TBP) revealed a critical trend: while thermodynamic properties like mass density and heat of vaporization are accurately predicted by many non-polarized and polarized force fields, the prediction of transport properties remains a significant challenge [6]. Both GAFF and OPLS-type force fields were found to systematically under-predict shear viscosity, with the best-performing model (polarized OPLS2005) still deviating from experimental values by a combined 62.6% for viscosity and self-diffusion [6]. This indicates a general limitation of classical force fields in capturing the dynamics governing viscous flow, a crucial consideration for researchers in drug development relying on accurate diffusion models.

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Protocol for SLLOD Viscosity Calculation

A typical protocol for calculating shear viscosity using the SLLOD algorithm involves several key stages. First, the system is energy-minimized and equilibrated in the NPT (isothermal-isobaric) ensemble at the target temperature and pressure to establish the correct density. This is followed by a further equilibration in the NVT (canonical) ensemble. The production stage then employs the SLLOD algorithm itself, implemented in an NVT ensemble with a Nosé-Hoover thermostat to maintain the target temperature. The shear rate is applied, for example, in the x-direction with a gradient in the z-direction. The shear stress ⟨P_xz⟩ is collected from the simulation, and the viscosity is calculated as η = - ⟨P_xz⟩ / γ̇. To obtain the zero-shear-rate viscosity, this process is repeated for multiple shear rates, and the resulting viscosities are extrapolated to γ̇ → 0 [25].

Protocol for High-Throughput Viscosity Screening

Emerging high-throughput workflows integrate MD with machine learning to efficiently explore material performance. As demonstrated for viscosity index improver polymers, the pipeline begins with an automated curation of polymer structures. All-atom MD simulations, often using force fields like GAFF or OPLS, are then run in a high-throughput manner to compute shear viscosity and other properties. The resulting data forms a dedicated dataset, which is subjected to automated feature engineering and machine learning model training. Models such as XGBoost or symbolic regression are used for multi-objective constrained virtual screening of potential high-performance molecules. The most promising candidates identified in silico are finally validated through direct MD simulations [28].

Diagram 1: SLLOD Viscosity Calculation Workflow. This chart outlines the key steps in a typical SLLOD simulation for determining shear viscosity.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

The following table details key computational "reagents" and resources essential for conducting research in this field.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for NEMD Viscosity Studies

| Tool/Solution | Function/Brief Explanation | Example Context |

|---|---|---|

| SLLOD Algorithm | Core algorithm for imposing homogeneous shear flow and calculating viscous response. | Fundamental to NEMD shear viscosity simulations [6] [25]. |

| GAFF Force Field | A general-purpose force field for organic molecules; provides parameters for atoms. | Used for predicting thermodynamic and transport properties of diverse molecules [6] [26]. |

| OPLS Force Field | A force field optimized for liquid simulations; multiple variants exist (e.g., OPLS2005, L-OPLS-AA). | Often used for organic liquids and lubricants; compared against GAFF for performance [24] [6]. |

| Green-Kubo Formalism | An equilibrium method (alternative to SLLOD) for calculating transport properties from flux autocorrelations. | Used as a benchmark against NEMD methods; part of force field validation [26] [25]. |

| High-Throughput MD Pipeline | Automated workflow for batch computation of properties like viscosity from molecular structures. | Enables large-scale screening of polymers for properties like Viscosity Index [28]. |

| cis-(Z)-Flupentixol Dihydrochloride | cis-(Z)-Flupentixol Dihydrochloride, MF:C23H27Cl2F3N2OS, MW:507.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Sennoside C (Standard) | Sennoside C (Standard), MF:C42H40O19, MW:848.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The SLLOD algorithm within NEMD provides a powerful and direct route to simulating shear viscosity, particularly under conditions of high shear where non-Newtonian behavior like shear thinning is prevalent [25]. However, its performance is intrinsically linked to the choice of force field. Current benchmarks indicate that while force fields like GAFF and OPLS excel at predicting thermodynamic properties, they systematically under-predict shear viscosity [6]. This limitation is consistent across both equilibrium (Green-Kubo) and non-equilibrium (SLLOD) methods, pointing to a fundamental challenge in classical MD force fields for capturing the dynamics of viscous flow. For researchers in drug development and materials science, this underscores the necessity of rigorous method and force field validation against experimental data. The emerging paradigm of high-throughput MD coupled with explainable machine learning offers a promising pathway to not only screen materials but also to uncover the quantitative structure-property relationships that will guide the development of more accurate molecular models in the future [28].

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation serves as a critical bridge between theoretical chemistry and practical engineering, enabling researchers to predict molecular behavior under various conditions. For membrane transport applications, accurately simulating the movement of molecules like diisopropyl ether (DIPE) through selective barriers is fundamental to advancing separation technologies, fuel additive design, and pharmaceutical development. The accuracy of these simulations hinges on the force field (FF) selected to describe atomic interactions. This case study provides a rigorous evaluation of the GAFF (General AMBER Force Field) diffusion performance against alternative parameter sets within the specific context of DIPE membrane transport, delivering quantitative comparisons and methodological frameworks for research scientists and drug development professionals.

Force Field Performance Comparison

The predictive capability of a force field is judged by how well it reproduces experimentally observed physical properties. Key properties for membrane transport studies include density and viscosity, as these directly influence diffusion rates and permeability.

A comparative MD study evaluated three all-atom force fields—GAFF, OPLS-AA/CM1A, and CHARMM36—for simulating DIPE. The table below summarizes their performance against experimental data, with the percentage errors providing a clear, quantitative basis for comparison [29].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Force Fields for Diisopropyl Ether Simulation

| Force Field | Predicted Density (g/cm³) | Error vs. Experimental (%) | Predicted Viscosity (cP) | Error vs. Experimental (%) | Key Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GAFF (AMBER) | 0.716 | ~+1.7% | 0.320 | ~-18.0% | Accurate density prediction, computationally stable |

| OPLS-AA/CM1A | 0.702 | ~-0.3% | 0.385 | ~-1.3% | Excellent overall accuracy for both properties |

| CHARMM36 | 0.727 | ~+3.4% | 0.302 | ~-22.6% | Good description of covalent interactions |

The data reveals that OPLS-AA/CM1A demonstrates superior overall accuracy, with minimal deviation in both density and viscosity. While GAFF provides a reasonable estimate for density, it shows a significant underestimation of viscosity, which could lead to an over-prediction of diffusion coefficients in membrane transport simulations. CHARMM36, while informative, displayed the largest error in viscosity prediction.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Molecular Dynamics Simulation of DIPE

The following protocol was used to generate the comparative data in Table 1, providing a reproducible template for benchmarking force fields [29].

- System Setup: A simulation cell containing 3,375 DIPE molecules was constructed, initially configured as a 15x15x15 cubic lattice to ensure proper periodicity.

- Energy Minimization and Equilibration:

- The system was first compressed to achieve a density matching experimental values for DIPE at the target temperature and pressure.

- NVT Ensemble (Constant Particles, Volume, Temperature): The system was equilibrated for 200 ps using a modified Berendsen thermostat to stabilize the temperature.

- NPT Ensemble (Constant Particles, Pressure, Temperature): The system was further equilibrated for 200 ps to stabilize the pressure, ensuring a realistic state for data production.

- Production Run: A subsequent simulation phase was conducted to collect trajectory data for analysis.

- Property Calculation:

- Density: Calculated directly from the equilibrated simulation box dimensions and particle mass.

- Viscosity: Determined using both equilibrium (Green-Kubo relation) and non-equilibrium (reverse perturbation) methods to ensure robustness.

Validating Membrane Transport Predictions

Beyond pure component properties, the ultimate test of a simulation is predicting membrane permeation. The Solution-Diffusion (SD) model is the cornerstone theory for this validation, stating that permeation is the product of sorption and diffusion [30].

- Independent Parameter Measurement:

- Sorption: The membrane's equilibrium uptake of a penetrant molecule (like DIPE) is measured under varying fugacities to construct a sorption isotherm.

- Diffusion: The intra-membrane diffusivity of the penetrant is measured experimentally, for instance, using Pulsed Field Gradient Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (PFG-NMR).

- Model Prediction: The SD model is parameterized with these independently measured sorption and diffusion coefficients to predict the membrane permeation flux.

- Experimental Validation: The model's prediction is compared against a direct permeation experiment. Studies have confirmed that predictions made this way "align closely with those obtained through direct permeation experiments," validating the physical consistency of the SD model and the simulation parameters that feed into it [30].

Visualization of Workflows and Relationships

Force Field Evaluation and Validation Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the integrated computational and experimental pathway for evaluating a force field and applying it to predict membrane performance.

Force Field Functional Relationships

This diagram deconstructs the core energy calculation components that define a force field's behavior and accuracy in molecular simulations.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This section catalogs essential computational and experimental reagents critical for conducting research in this field.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Membrane Transport Simulation

| Reagent/Tool | Category | Specific Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| GAFF (AMBER) | Force Field | Provides parameters for covalent/non-covalent energies; a standard for organic molecules [29]. |

| OPLS-AA/CM1A | Force Field | An alternative with high accuracy for liquid transport properties like viscosity [29]. |

| GROMACS | Software | High-performance MD simulation package used for running and analyzing simulations [29]. |

| Diisopropyl Ether (DIPE) | Chemical | Model penetrant molecule for studying transport in organic solvent membranes and liquid membranes [29] [31]. |

| Pulsed Field Gradient (PFG) NMR | Experimental Technique | Measures molecular self-diffusion coefficients within membranes without applied concentration gradient [30]. |

| Sorption Balance | Experimental Apparatus | Measures equilibrium uptake (sorption isotherm) of a penetrant by a polymer membrane under varying fugacities [30]. |

| CHARMM-GUI | Web Server | Facilitates the generation of simulation input files and parameters for the CHARMM force field [29]. |

| LigParGen Server | Web Server | Generates OPLS-AA force field parameters with CM1A/L charges for organic molecules [29]. |

| DMT-dC(ac) Phosphoramidite | DMT-dC(ac) Phosphoramidite, MF:C41H50N5O8P, MW:771.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

This case study delivers a objective performance comparison of force fields for simulating diisopropyl ether, a molecule relevant to membrane transport and fuel additive applications. The quantitative analysis demonstrates that while the GAFF force field offers a robust and accessible framework, its tendency to underpredict viscosity suggests researchers should exercise caution when deriving diffusion coefficients directly from it. For applications requiring high quantitative accuracy in transport properties, the OPLS-AA/CM1A force field emerges as a more reliable alternative. The integration of independently validated simulation parameters into the Solution-Diffusion model presents a powerful methodology for predicting membrane performance, bridging the gap between atomic-level simulation and macroscopic experimental observation. This workflow provides researchers with a validated path for employing molecular simulation in the design and optimization of next-generation membrane systems.

Tri-n-butyl phosphate (TBP) is a solvent of significant industrial importance, particularly in nuclear fuel recycling processes such as the PUREX process, where it facilitates the liquid-liquid extraction of metal ions like uranium and plutonium [6] [32]. The efficiency of these separation processes is governed by molecular-level interactions and transport phenomena, making accurate molecular dynamics (MD) simulations an invaluable tool for process optimization [6] [32]. The accuracy of these simulations, however, critically depends on the force field parameters used to describe molecular interactions. This case study provides a comparative evaluation of the Generalized AMBER Force Field (GAFF) against other common force fields, with a specific focus on their performance in predicting key transport properties of liquid TBP, namely self-diffusion coefficients and shear viscosity [6].

Molecular dynamics simulations model the physical movements of atoms and molecules over time, with the interactions between these particles described by mathematical functions known as force fields. The choice of force field significantly influences the predictive accuracy of thermodynamic and transport properties [6].

Table 1: Common Force Fields Used in TBP Simulations

| Force Field | Full Name | Key Characteristics | Common Charge Models |

|---|---|---|---|

| GAFF | General AMBER Force Field | Developed for small organic molecules; compatible with AMBER biomolecular force fields [5]. | AM1-BCC [5] [10] |

| OPLS-AA/OPLS2005 | Optimized Potentials for Liquid Simulations | Parameterized for organic liquids and biomolecules; emphasizes accurate liquid-state properties [6] [5]. | Various, from DFT calculations [6] [32] |

| Polarizable Force Fields | - | Include explicit treatment of polarization (e.g., induced point dipoles); more computationally expensive [6]. | Varies; often based on DFT [6] |

For TBP systems, both non-polarized and polarized versions of these force fields are employed. Polarized force fields account for the response of a molecule's charge distribution to its changing environment, which can be crucial for modeling interfaces and mixed environments [6]. However, their computational cost is substantially higher [6].

Comparative Performance in Predicting TBP Transport Properties

Transport properties like self-diffusion coefficient and shear viscosity are critical for understanding mass transfer in solvent extraction processes but are notoriously difficult to predict accurately with MD simulations [6].

Quantitative Comparison of Force Field Performance

Table 2: Performance Summary of Force Fields for Pure Liquid TBP Properties

| Force Field | Self-Diffusion Coefficient | Shear Viscosity | Mass Density | Heat of Vaporization |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GAFF (Non-polarized) | Systematically underpredicted [6] | Systematically underpredicted [6] | Accurate (e.g., ~4.5% deviation with AMBER-DFT model) [6] | Accurate (e.g., ~4.5% deviation with AMBER-DFT model) [6] |

| OPLS2005 (Non-polarized) | Underpredicted (Best non-polarized model deviates -17.4%) [6] | Underpredicted [6] | Accurate [6] [32] | Accurate [6] [32] |

| OPLS2005 (Polarized) | Best overall performer, though still deviates -17.4% from experiment [6] | Best overall performer, but combined deviation for transport properties is 62.6% [6] | Can be improved with specific force fields [6] | Can be improved with specific force fields [6] |

Key Findings from the Comparison

- Systematic Underprediction of Transport Properties: A comprehensive 2025 study highlights a significant challenge: all 20 tested force field models, including polarized and non-polarized versions of GAFF and OPLS, systematically underpredict self-diffusion coefficients and shear viscosity for neat TBP [6]. This indicates a fundamental issue in how current force fields capture the friction and energy dissipation in liquid TBP.

- Clear Performance Gap: There is a marked performance gap between the prediction of thermodynamic and transport properties. While mass density and heat of vaporization can be predicted with deviations at or below 4.5% using non-polarized force fields like AMBER-DFT (a variant of GAFF), the best combined deviation for transport properties using a polarized force field is much higher, at 62.6% [6].

- Limited Benefit of Polarization for Transport Properties: The addition of polarization, while computationally expensive, does not consistently solve the problem of predicting transport properties across all force fields. It can improve predictions for individual properties with specific force fields, but the improvements are not universal, and transport properties remain a challenge [6].

- Performance in Mixed Environments: Beyond pure TBP, the performance of force fields can vary in different chemical environments. A refined OPLS2005 model was found to be the only one from a set of five that could simultaneously predict properties of TBP in bulk, organic diluents, and aqueous solution with reasonable accuracy, whereas other models, including some GAFF variants, were only accurate in two of the three environments [32]. This is crucial for simulating liquid-liquid extraction.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

The quantitative results cited in this study are primarily derived from detailed molecular dynamics simulations. The general workflow and key methodologies are summarized below.

Workflow for Molecular Dynamics Simulations of TBP

The following diagram illustrates the general workflow for computing TBP properties using molecular dynamics simulations, integrating protocols from multiple studies [6] [32] [10].

Key Methodological Details

- System Setup: Simulation cells of pure liquid TBP are constructed using packing algorithms, typically with several hundred molecules to ensure a representative bulk environment [6] [10]. The system is energy-minimized and gently heated to the target temperature (e.g., 298 K or 300 K) before formal equilibration.

- Equilibration and Production: The system is equilibrated in the isothermal-isobaric (NPT) ensemble to achieve the correct experimental mass density. This is followed by a longer production run, often in the microsecond timescale, in the canonical (NVT) or NPT ensemble to collect trajectory data for analysis [6].

- Transport Property Calculation: Two primary methods are used:

- Equilibrium MD (EMD): Transport properties are derived from fluctuations at equilibrium using the Green-Kubo formalism, which relates time integrals of autocorrelation functions of the pressure tensor (for shear viscosity) and velocity (for self-diffusion) to transport coefficients [6].

- Non-Equilibrium MD (NEMD): The SLLOD algorithm is used to impose a shear flow on the system. The shear viscosity is then calculated from the ratio of the applied shear stress to the resulting strain rate [6]. Studies have shown that both methods tend to underpredict viscosity and overpredict diffusion (faster dynamics) for TBP with current force fields [6].

- Electrostatic Handling: Electrostatic interactions are almost universally treated using the Particle Mesh Ewald (PME) method, which provides an accurate and efficient way to handle long-range interactions in periodic systems [32] [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Key Computational Tools and Parameters for TBP MD Simulations

| Tool/Parameter | Function/Description | Example/Standard |

|---|---|---|

| Force Field Parameters | Defines bonded and non-bonded interactions between atoms. | GAFF, OPLS-AA, OPLS2005 [6] [5] |

| Partial Atomic Charges | Models electrostatic interactions; critical for polarity. | AM1-BCC (GAFF), RESP, charges from DFT calculations [6] [5] [32] |

| Water Model | Solvent model for aqueous mixtures and interfaces. | TIP3P, SPC/E, TIP4P [5] [33] |

| Simulation Software | Software package to perform MD simulations. | GROMACS, AMBER, CHARMM, LAMMPS [6] [10] |

| Analysis Tools | Programs for analyzing simulation trajectories. | MDAnalysis, VMD, GROMACS analysis tools [6] |

| Charge Scaling Factor | Empirical scaling of charges to improve hydrophilicity/hydrophobicity. | 0.8 (common for ionic liquids/GAFF) [34], 0.6-0.7 (used for TBP) [6] [33] |