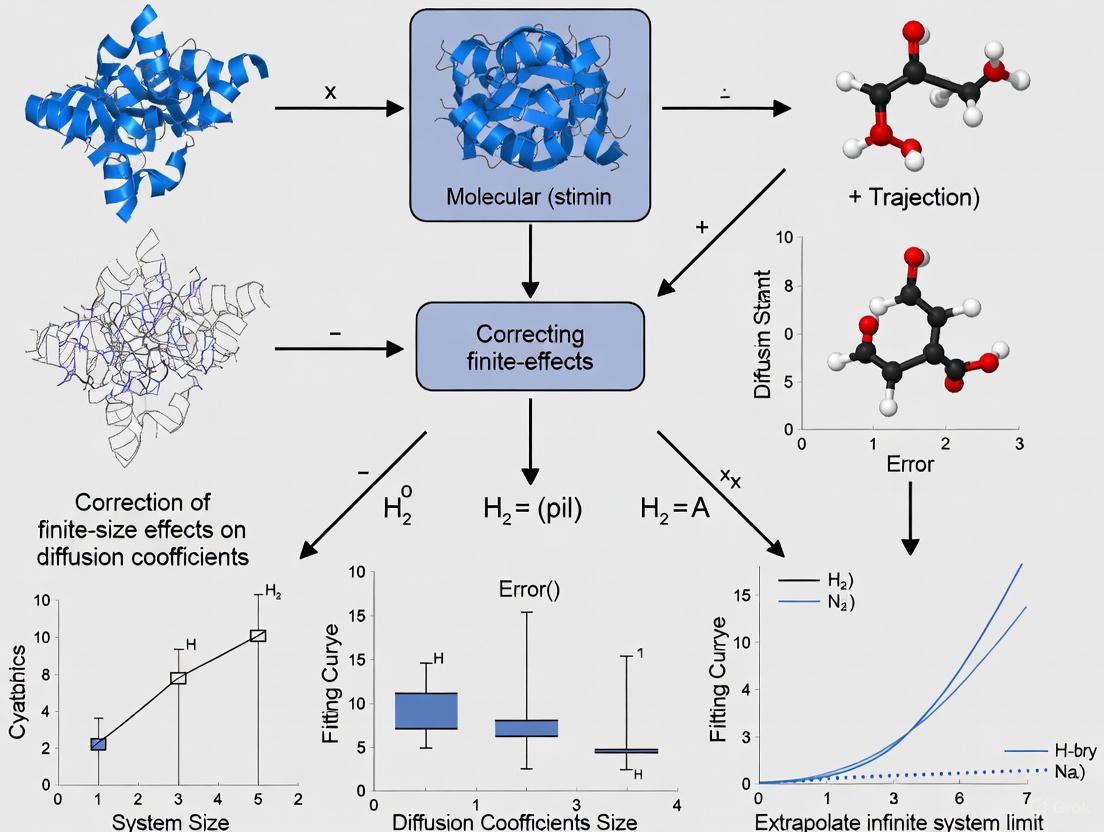

Correcting Finite-Size Effects in Molecular Dynamics Diffusion Coefficients: From Theory to Pharmaceutical Applications

Molecular dynamics simulations are powerful tools for predicting diffusion coefficients crucial for drug development, but results are skewed by finite-size effects where computed diffusivities artificially depend on simulated system size.

Correcting Finite-Size Effects in Molecular Dynamics Diffusion Coefficients: From Theory to Pharmaceutical Applications

Abstract

Molecular dynamics simulations are powerful tools for predicting diffusion coefficients crucial for drug development, but results are skewed by finite-size effects where computed diffusivities artificially depend on simulated system size. This comprehensive review explores the foundational theory behind these effects, presents practical correction methodologies including the established Yeh-Hummer approach and its extensions to mutual diffusion, addresses troubleshooting for challenging systems near demixing, and validates techniques through comparative analysis across Lennard-Jones and molecular systems. For researchers and drug development professionals, we provide essential guidance for obtaining reliable, experimentally comparable diffusion coefficients from molecular simulations, with direct implications for pharmaceutical formulation and biomolecular transport modeling.

Understanding Finite-Size Effects: Why Your Simulated Diffusion Coefficients Are Wrong

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the fundamental problem with system size and diffusion coefficients? In molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, the calculated diffusion coefficients show a strong dependency on the number of molecules (N) in the simulation box. Computed diffusivities artificially increase with the number of molecules and the size of the simulation box. This is a finite-size effect, meaning the simulated value is not the true value for the macroscopic system (the "thermodynamic limit") [1].

FAQ 2: Why does this inflation occur? The artificial inflation occurs primarily due to hydrodynamic self-interactions imposed by the use of periodic boundary conditions. In a finite, periodic system, a molecule's motion is correlated with its own images in neighboring cells. The difference in these interactions between a finite periodic system and an infinite non-periodic system leads to the observed discrepancy. The effect scales linearly with the inverse of the box size (1/L) [1].

FAQ 3: Which types of diffusion coefficients are affected? This problem affects all major types of diffusion coefficients obtained from simulations:

- Self-diffusion coefficient (D~self~): The diffusivity of a single tagged particle in a medium [1].

- Maxwell-Stefan (MS) diffusivity (Ä~MS~): Describes mass transport due to the gradient in chemical potential [1].

- Fick diffusivity (D~Fick~): The coefficient relating mass flux to concentration gradient, which can be derived from the MS diffusivity [1].

FAQ 4: When are finite-size effects most severe? Finite-size effects are particularly pronounced and critical to correct for in the following scenarios [1]:

- Systems close to demixing, where the thermodynamic factor indicates strong non-ideality.

- Mixtures near critical points or phase transitions.

- Simulations with a small number of molecules. In some severe cases near demixing, the required finite-size correction can be larger than the simulated diffusivity value itself.

FAQ 5: How can I correct for this artifact?

The most common method is to apply the Yeh-Hummer (YH) correction. For self-diffusion coefficients, the formula is:

D_{self}^∞ = D_{self} + D_{YH}, where D_{YH} = (k_B T ξ)/(6 π η L)

This correction term is a function of the system's shear viscosity (η), the simulation box size (L), and temperature (T) [1]. For MS diffusivities, a modified correction that also accounts for the thermodynamic factor (Γ) must be used [1].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: My simulated diffusion coefficient is higher than expected or reported in literature.

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Small system size | 1. Calculate diffusion coefficients for systems with different numbers of molecules (N).2. Plot D versus 1/N¹/³. A clear positive slope indicates a strong finite-size effect [1]. | Apply the appropriate Yeh-Hummer correction to extrapolate the value to the thermodynamic limit (N→∞) [1]. |

| Inadequate analysis protocol | The statistical uncertainty of the diffusion coefficient estimated from Mean-Squared Displacement (MSD) data depends heavily on the choice of statistical estimator and data processing decisions [2]. | Do not rely solely on ordinary least squares (OLS) regression. Explore and clearly report the analysis protocol used, as alternative methods can estimate D* more precisely [2]. |

| Uncorrected MS diffusivity | Check if you are simulating a mixture close to demixing (using the thermodynamic factor). Finite-size effects on MS diffusivities are most severe in these non-ideal systems [1]. | Apply the finite-size correction for MS diffusion, which incorporates the thermodynamic factor: Ä_{MS}^∞ = Ä_{MS} + (k_B T)/(6 Ï€ η L) * (Γ^{-1} - 1) [1]. |

Problem: High uncertainty in my calculated diffusion coefficient.

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Poor MSD statistics | Check the smoothness and linearity of the MSD plot over time. Noisy data or a poor fit will lead to high uncertainty [2]. | Increase simulation time to improve sampling. Ensure the MSD is calculated from a sufficiently long, steady-state trajectory segment. |

| Incorrect regression method | Compare results using different regression techniques (e.g., ordinary least squares vs. methods that account for correlated data points) on the same MSD data [2]. | Use a statistical analysis protocol that is robust and accounts for the correlations in the MSD data, as the uncertainty is not universal but depends on the estimator choice [2]. |

The following table summarizes key relationships and correction factors for finite-size effects, as identified in the literature.

Table 1: Summary of Finite-Size Effects and Corrections for Diffusion Coefficients

| Diffusion Coefficient Type | Observed Finite-Size Scaling | Proposed Correction Method | Key Variables |

|---|---|---|---|

| Self-Diffusion (D~self~) | Increases linearly with 1/N¹/³ (equivalent to 1/L) [1] | Yeh-Hummer (YH) correction: D_{self}^∞ = D_{self} + (k_B T ξ)/(6 π η L) [1] |

L: Box side lengthT: Temperatureη: Shear viscosityξ: Constant (2.837 for cubic boxes) |

| Maxwell-Stefan (Ä~MS~) | Increases with system size; effect magnified by non-ideality [1] | Modified YH correction: Ä_{MS}^∞ = Ä_{MS} + (k_B T)/(6 Ï€ η L) * (Γ^{-1} - 1) [1] |

Γ: Thermodynamic factor (measure of non-ideality). All other variables as above. |

| Fick (D~Fick~) | Derived from MS diffusivity, so inherits its finite-size effects. | Correct the parent MS diffusivity first: D_{Fick} = Ä_{MS} * Γ [1] |

D~Fick~ is calculated from the corrected Ä~MS~∞ and Γ. |

Table 2: Experimental vs. Predicted Diffusion Coefficients in a Sample System (Glucose-Water) [3]

| Temperature (°C) | Experimental D (cm²/s) | Wilke-Chang Prediction (cm²/s) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 25 | ~ 6.8 × 10â»â¶ | Similar to experimental value | Semi-empirical models can be inaccurate outside their calibration range [3]. |

| 65 | ~ 1.7 × 10â»âµ | Significant overestimation | At higher temperatures, common models like Wilke-Chang can fail, highlighting the need for accurate measurement or simulation [3]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Correcting Self-Diffusion Coefficients from MD Simulations

This protocol details the steps to obtain a size-corrected self-diffusion coefficient from an Equilibrium Molecular Dynamics (EMD) simulation [1].

1. Run Simulations: Perform EMD simulations for systems with different numbers of molecules (N) while maintaining constant density.

2. Calculate MSD: For each system, compute the Mean-Squared Displacement (MSD) of the molecules over time using the Einstein relation:

MSD(t) = (1/N) ⟨ |r~j~(t) - r~j~(0)|² ⟩

3. Extract D~self~: Perform a linear regression on the MSD plot to obtain the uncorrected self-diffusion coefficient for each system size: D_{self} = (1/(6t)) * MSD(t).

4. Compute Viscosity: Calculate the shear viscosity (η) for your system from the autocorrelation of the off-diagonal components of the stress tensor using the Green-Kubo relation. Note that viscosity is generally independent of system size [1].

5. Apply YH Correction: For each D_{self}, calculate the corrected value for the thermodynamic limit using:

D_{self}^∞ = D_{self} + (k_B T * 2.837297)/(6 π η L)

Protocol 2: Measuring Diffusion Coefficients via Taylor Dispersion

This is an experimental method used to validate computational results or obtain diffusion data directly. It is considered highly accurate and is used for both binary and ternary liquid systems [3].

1. Setup: Use a long (e.g., 20 m), thin, coiled Teflon tube immersed in a thermostat for temperature control. The tube should have a circular cross-section to ensure laminar flow.

2. Prepare Solutions: Create a solvent stream and a pulse of solution with a slightly different composition.

3. Inject Pulse: Introduce a small volume (e.g., 0.5 cm³) of the solution pulse into the laminar solvent stream using a pump.

4. Detect Concentration: At the outlet of the tube, use a differential refractive index analyzer to measure the concentration profile of the dispersed pulse, which will take a Gaussian shape.

5. Calculate D: The mutual diffusion coefficient is determined by fitting the variance of the detected concentration profile over time. The governing equation is derived from Taylor's work:

D = (u² R²) / (48 * σ²)

where u is the average flow velocity, R is the tube radius, and σ² is the temporal variance of the concentration profile [3].

Workflow and Signaling Diagrams

Finite-Size Correction Workflow

Cause of Artificial Inflation

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational and Experimental Tools

| Tool / Reagent | Function / Description | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Equilibrium Molecular Dynamics (EMD) | Simulation method where transport coefficients are computed from time-correlation functions in a system at equilibrium [1]. | Core method for computing diffusion coefficients from simulations. |

| Periodic Boundary Conditions (PBC) | A common boundary condition used in MD simulations to mimic a bulk system by replicating the simulation box in all directions [1]. | The source of the finite-size artifact for diffusion. |

| Yeh-Hummer (YH) Correction | An analytical correction term derived from hydrodynamic theory to compensate for finite-size effects on self-diffusivity [1]. | The primary method for extrapolating simulated D_self to the thermodynamic limit. |

| Thermodynamic Factor (Γ) | A measure of the non-ideality of a mixture, calculated from the derivative of chemical potential with respect to concentration [1]. | Critical for correcting Maxwell-Stefan diffusivities in mixtures. |

| Taylor Dispersion Apparatus | An experimental setup involving a long capillary tube to measure mutual diffusion coefficients in liquids based on laminar flow dispersion [3]. | Used for obtaining ground-truth experimental data to validate simulation results. |

FAQs: Understanding Finite-Size Effects

What are finite-size effects in the context of diffusion coefficients? Finite-size effects refer to the systematic errors or deviations in calculated self-diffusion coefficients that arise from simulating a fluid in a limited, finite-sized periodic box rather than in an infinite medium. In molecular dynamics (MD) simulations of bulk liquids, these effects cause the diffusion tensor to appear anisotropic and can lead to diffusivity in the direction of the box's short side exceeding the value for an infinite system [4].

What is the hydrodynamic origin of these finite-size dependencies? The origin is rooted in hydrodynamic interactions. A moving particle generates a long-ranged flow disturbance in the surrounding fluid, which decays inversely with interparticle distance. In a finite system with periodic boundaries, these disturbance flows interact with the periodic images of the simulation box, affecting the particle's motion. The resulting hydrodynamic coupling means particles do not move independently but exhibit collective, system-size-dependent behavior [5].

Why does the shape of the simulation box matter? The box geometry determines how the periodic images interact hydrodynamically. In a highly asymmetric (e.g., rectangular parallelepiped) box, the confinement effect is direction-dependent. This leads to an apparent anisotropy in the diffusion tensor, even for an isotropic bulk liquid, with the diffusion component along the short side of the box being most significantly enhanced [4].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Anisotropic Diffusion in a Bulk Liquid Simulation

Problem: Your simulation of a simple, isotropic bulk liquid yields an anisotropic diffusion tensor.

Diagnosis Steps:

- Check Box Geometry: Verify the aspect ratio of your periodic simulation box. A high aspect ratio is a primary cause of this artifact [4].

- Quantify the Effect: Calculate the diffusion coefficients along each box vector (Dx, Dy, Dz). The highest value will typically align with the shortest box vector.

- Compare to Theory: Use the hydrodynamic theory for periodic rectangular box systems to predict the expected diffusivity for your box size and shape. Compare this to your MD results [4].

Solutions:

- Apply a Correction: Use the analytical expressions derived from hydrodynamic theory to correct your computed self-diffusion coefficient to its infinite-system value [4].

- Modify System Geometry: If possible, use a cubic simulation box to avoid artificial anisotropy. For non-cubic boxes, be aware that the aspect ratio at which the diffusivity coincides with the infinite-system value is a universal constant, independent of the cross-sectional area or thickness [4].

Issue: Inaccurate Hydrodynamic Interactions in Dense Suspensions

Problem: Your simulation of a particle suspension fails to capture the correct many-body hydrodynamic interactions (HIs), leading to inaccurate dynamics.

Diagnosis Steps:

- Review Method Approximations: Identify the level of approximation in your HI model. Common methods like the two-body Rotne-Prager-Yamakawa (RPY) approximation neglect crucial many-body effects and near-field lubrication forces [5].

- Check Boundary Conditions: Confirm that your method correctly handles the desired boundary conditions (e.g., periodic). Some far-field approximations are limited to open boundaries [5].

- Validate with a Test System: Run a simulation for a system with a known solution to isolate the error.

Solutions:

- Use a More Accurate Method: Implement Stokesian Dynamics (SD), which combines far-field approximations with near-field lubrication corrections for a balanced approach [5].

- Adopt Advanced Algorithms: For larger systems, use modern implementations like Fast Stokesian Dynamics (FSD) that use iterative solvers and matrix-free techniques for linear scaling [5].

- Consider a Hybrid Framework: For complex systems, explore emerging hybrid models that use a neural network to correct efficient two-body approximations, trained on SD data to capture many-body effects at a lower computational cost [5].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Detailed Methodology: System Size Effect Analysis via MD

This protocol outlines how to quantify the finite-size effect on the self-diffusion coefficient using Molecular Dynamics simulations, based on the work of Kikugawa et al. [4].

1. System Preparation:

- Software: Use an MD package capable of simulating periodic boundary conditions and calculating mean-squared displacement (e.g., GROMACS, LAMMPS).

- Model System: Select a simple liquid (e.g., Lennard-Jones particles).

- Box Creation: Generate multiple simulation boxes with identical particle density but different geometries:

- A series of cubic boxes of increasing size (e.g., side lengths from 5σ to 20σ).

- A series of rectangular boxes with varying aspect ratios (e.g., rod-shaped and film-type).

2. Simulation Execution:

- Equilibration: Equilibrate each system in the NVT ensemble until energy and pressure stabilize.

- Production Run: Switch to the NVE ensemble for production. Ensure the simulation is long enough to obtain a linear region in the mean-squared displacement (MSD) plot.

- Data Collection: Output trajectory data at a frequency sufficient for accurate MSD calculation.

3. Data Analysis:

- Calculate MSD: For each box geometry and direction, compute the mean-squared displacement,

MSD(t) = ⟨|r(t) - r(0)|²⟩. - Extract Diffusion Coefficient: Fit the linear part of the MSD curve for each direction to the equation

MSD(t) = 2dDt, wheredis the dimensionality, to obtain the diffusion tensor componentsD_xx,D_yy,D_zz. - Compare to Theory: Plot the computed diffusivity against the theoretical prediction from hydrodynamic theory for periodic systems [4].

Key Quantitative Relationships

Table 1: Finite-Size Effects on Self-Diffusion Coefficient in Periodic Systems

| System Geometry | Key Finding | Theoretical Basis |

|---|---|---|

| Cubic Box | Diffusivity converges to infinite-system value as box size increases; well-described by standard hydrodynamic theory. | Stokes equations with periodic boundary conditions [4] [5]. |

| Rectangular Parallelepiped Box | Diffusion tensor becomes anisotropic. Diffusivity along the short side is enhanced and can exceed the infinite-system value. | Extended hydrodynamic theory for periodic rectangular boxes [4]. |

| Rod-Shaped & Film-Type Boxes | Exists a universal aspect ratio where the measured diffusivity matches that of an infinite system, independent of cross-sectional area or thickness. | Simplified approximate model derived from hydrodynamic description [4]. |

Table 2: Comparison of Methods for Simulating Hydrodynamic Interactions (HIs)

| Method | Description | Strengths | Weaknesses |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stokesian Dynamics (SD) | Combines far-field Green's functions with near-field lubrication corrections [5]. | High accuracy for both far- and near-field HIs; models many-body effects [5]. | Historically complex and computationally expensive; requires matrix inversions [5]. |

| Rotne-Prager-Yamakawa (RPY) | A common far-field approximation for the mobility matrix [5]. | Computationally efficient; good for dilute suspensions [5]. | Neglects many-body effects and near-field lubrication; inaccurate for dense suspensions [5]. |

| Fast Stokesian Dynamics (FSD) | Modern SD using spectral Ewald methods and matrix-free algorithms [5]. | Linear O(N) scaling; competitive for large systems with simple boundaries [5]. |

Less versatile for complex geometries compared to LB or MPCD [5]. |

| Lattice Boltzmann (LB) | Solves discrete Boltzmann equation on a lattice [5]. | Handles complex geometries; captures thermal fluctuations and inertia [5]. | Struggles to match SD's precision in near- and far-field HIs [5]. |

Mandatory Visualization

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Hydrodynamic Studies

| Item / Reagent | Function / Role in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Molecular Dynamics (MD) Software | Performs the core simulation of particle dynamics, calculates trajectories, and outputs data for analysis (e.g., mean-squared displacement) [4]. |

| Stokesian Dynamics (SD) Code | A numerical framework specifically designed to accurately simulate many-body hydrodynamic interactions in suspensions at low Reynolds numbers [5]. |

| Monodisperse Hard Sphere Model | A simplified, standard model for suspended particles. Allows for analytical and numerical treatment to study fundamental HI behavior without complex particle shape effects [5]. |

| Linear Solver & Preconditioner | Numerical tools required to efficiently solve the large system of linear equations that arise in methods like SD, especially for dense suspensions [5]. |

| Dihydrohypothemycin | Dihydrohypothemycin, MF:C19H24O8, MW:380.4 g/mol |

| Antitumor agent-196 | Antitumor agent-196, MF:C51H81NO15, MW:948.2 g/mol |

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What are finite-size effects in diffusion coefficient calculations, and why must they be corrected?

In molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, the simulated system's size (or "box size") is finite, unlike in real-world experiments. This limitation introduces artifacts in the calculation of transport properties like diffusion coefficients. In concentrated protein solutions, for instance, the translational diffusion coefficients (DtPBC) obtained directly from simulation require correction for large finite-size effects using system viscosity. Without this correction, the reported diffusion coefficients will be inaccurate and not representative of the true bulk material behavior [6].

2. How does system viscosity relate to diffusion coefficients?

The relationship between viscosity and diffusion is formally described by the Stokes-Einstein relation, which states that the translational diffusion coefficient (D_t) is inversely proportional to the viscosity (η) of the medium and the hydrodynamic radius (R_h) of the diffusing particle. In concentrated protein solutions, research confirms that the Stokes-Einstein relation remains valid. However, the effective hydrodynamic radius increases with protein volume fraction, which explains the dramatic slowdown of diffusion in crowded environments. The viscosity itself increases strongly with protein concentration, an effect that exceeds predictions from simple hard-sphere colloid models due to attractive protein-protein interactions and dynamic cluster formation [6].

3. What is the specific effect of temperature on diffusion coefficients?

Temperature has a direct and profound impact on molecular motion and therefore on diffusion coefficients. This influence is captured by the Arrhenius equation, which relates the diffusion coefficient (D) to the activation energy (Q) and temperature (T). Experimental studies consistently show that diffusion coefficients increase with temperature. For example, in the FCC Al-Cu-V alloy system, the activation energies for solute diffusion were calculated and analyzed, quantitatively showing how temperature accelerates diffusion [7]. Similarly, in polymer systems, diffusion coefficients for volatile components were measured at different temperatures (e.g., 60°C, 80°C, and 100°C), confirming this relationship [8].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Inaccurate Diffusion Coefficients in Simulations

Problem: Diffusion coefficients calculated from your molecular dynamics (MD) simulations seem excessively high or do not match experimental values.

Solution:

- Check System Size: Ensure your simulation box is large enough. For protein solutions, systems containing hundreds of proteins (e.g., 540 proteins with 3.6 million atoms) are used to better approximate bulk conditions [6].

- Apply Finite-Size Correction: The diffusion coefficient obtained directly from simulation (

DtPBC) must be corrected. Use the relation based on the system's viscosity [6]:D_t = D_tPBC + (k_B * T * ξ)/(6 * π * η * L)wherek_Bis Boltzmann's constant,Tis temperature,ηis the viscosity of your solution,Lis the box length, andξis a constant. - Validate with Long-Time Diffusion: Use the long-time diffusion coefficient derived from the linear portion of the mean-squared displacement (MSD) curve at sufficiently long time scales (e.g., 10 ns to 30 ns in protein solutions) [6].

Issue 2: Uncontrolled Variables in Experimental Diffusion Measurements

Problem: Results from experimental diffusion measurements (e.g., using diffusion couples or spectroscopy) are inconsistent between replicates.

Solution:

- Control Temperature Precisely: Temperature must be tightly controlled and reported, as it directly affects diffusion rates. For diffusion couple studies in alloys, annealing temperatures should be maintained precisely (e.g., 530°C, 555°C, 580°C) [7].

- Ensure Proper Sample Saturation: When measuring solvent diffusion in polymers, ensure samples are deliberately saturated to a known equilibrium concentration in a controlled sorption experiment before desorption measurements begin [8].

- Align Analytical Techniques: When using techniques like Electron Probe Microanalysis (EPMA) on diffusion couples, align multiple line scans (e.g., at least five) to the interface position to generate a reliable average concentration profile [7].

Quantitative Data Tables

Table 1: Experimentally Determined Drug Diffusion Coefficients through Artificial Mucus

This table summarizes data obtained via ATR-FTIR spectroscopy and analysis using Fick's second law [9].

| Drug | Diffusion Coefficient (D) at Reported Conditions | Molecular Characteristics | Experimental Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Theophylline | 6.56 × 10â»â¶ cm²/s | - | ATR-FTIR spectroscopy coupled with Fick's 2nd Law and Crank's trigonometric series solution for a planar semi-infinite sheet. |

| Albuterol (Salbutamol) | 4.66 × 10â»â¶ cm²/s | - | ATR-FTIR spectroscopy coupled with Fick's 2nd Law and Crank's trigonometric series solution for a planar semi-infinite sheet. |

Table 2: Key Dependencies of Diffusion from Simulation and Experiment

This table synthesizes the influence of key parameters as reported across multiple studies [9] [7] [8].

| Parameter | Effect on Diffusion Coefficient (D) |

Context & Supporting Evidence |

|---|---|---|

Temperature (T) |

Increases with temperature following an Arrhenius relationship (D ∠exp(-Q/RT)). |

Activation energies (Q) for solute diffusion were calculated in Al-Cu-V alloys [7]. Diffusion coefficients for toluene in polymers increased with temperature from 60°C to 100°C [8]. |

Viscosity (η) |

Inversely proportional to translational diffusion (D_t ∠1/η). Stokes-Einstein relation holds. |

In concentrated protein solutions, viscosity increase from ~1 mPa·s to over 4 mPa·s (at ϕ=0.15) correlates with a strong slowdown in diffusion [6]. |

| Box Size (Simulation) | Artificially high D in small boxes; requires finite-size correction. |

In MD simulations of proteins, finite-size corrections are applied to DtPBC using box length (L) and viscosity (η) [6]. |

Concentration / Volume Fraction (Ï•) |

Generally decreases as the volume fraction of the diffusing species increases. | In Al-Cu-V, adding V decreased the diffusivity of Cu [7]. In protein solutions, D_t decreases significantly as protein concentration rises from dilute to 200 mg/mL and higher [6]. |

| Molecular Size | Larger molecules/particles typically have smaller diffusion coefficients. | An inverse relationship between molecular weight and diffusion coefficient has been reported for drugs in mucus [9]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Determining Drug Diffusion Coefficients using ATR-FTIR Spectroscopy

This protocol is adapted from studies measuring the diffusion of asthma drugs through artificial mucus [9].

1. Principle: Couple time-resolved Attenuated Total Reflectance Fourier Transform Infrared (ATR-FTIR) spectroscopy with Fickian diffusion models to determine the diffusivity of drug molecules through a synthetic membrane.

2. Materials:

- ATR-FTIR Spectrometer: Equipped with a flow-through cell and a Zinc Selenide (ZnSe) crystal.

- Artificial Mucus: A synthetic construct that mimics the complex, hydrophobic, and crosslinked fiber network of pulmonary mucus.

- Drug Solutions: Prepared with the analytes of interest (e.g., Theophylline, Albuterol).

3. Procedure:

- Sample Setup: Place a layer of artificial mucus in direct contact with the ZnSe crystal of the ATR-FTIR. The lower surface of the mucus contacts the crystal, while the upper surface is exposed to the drug solution.

- Data Collection: Initiate the experiment by introducing the drug solution to the upper mucus surface. Collect FTIR spectra at constant, short time intervals (e.g., every few seconds).

- Quantitative Monitoring: Monitor quantitative changes in the height of IR absorption peaks that are specific to functional groups of the drug molecule.

- Data Analysis:

a. Correlate the changes in peak height to drug concentration using Beer's Law.

b. Analyze the concentration-over-time data using Fick's Second Law of Diffusion.

c. Fit the experimental data to Crank's trigonometric series solution for a planar semi-infinite sheet to determine the diffusion coefficient (

D).

The following workflow diagram illustrates this experimental process:

Protocol 2: Extracting Interdiffusion Coefficients using the Diffusion Couple Method

This protocol is standard in materials science for studying diffusion in alloys, as applied in the Al-Cu-V system [7].

1. Principle: Bring two materials with different compositions into intimate contact and anneal at high temperature to allow solutes to interdiffuse. Measurement of the resulting concentration profile allows for the calculation of interdiffusion coefficients.

2. Materials:

- High-purity elemental materials (e.g., 99.99% Al, 99.9% Cu, 99.8% V).

- Arc melting furnace for casting alloy samples.

- Hydraulic press for assembling diffusion couples.

- High-temperature annealing furnace with precise temperature control.

- Electron Probe Microanalyzer (EPMA) for high-resolution concentration measurements.

3. Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Cast binary (e.g., Al-Cu, Al-V) and ternary (Al-Cu-V) alloys via arc melting. Machine samples to create flat, smooth surfaces for interface contact.

- Assembly: Sandwich two different alloy samples together (e.g., Al-Cu-V vs. Al-V) and use a hydraulic press to assemble them into a diffusion couple under a protective atmosphere to prevent oxidation.

- Annealing: Seal the diffusion couple in an evacuated quartz tube and anneal it at the target temperatures (e.g., 530°C, 555°C, 580°C) for an extended period (e.g., 1500 hours) to facilitate solute interdiffusion.

- Concentration Profiling: After annealing, cross-section the couple and use EPMA to perform multiple line scans perpendicular to the diffusion interface, measuring the concentrations of each solute (Cu, V) as a function of distance.

- Data Analysis: Extract the interdiffusion coefficients from the concentration profiles. This can be done using:

- The Forward Simulation Analysis (FSA) method, which iteratively refines

Dvalues until the simulated concentration profile matches the experimental one [7]. - Traditional methods based on the Boltzmann-Matano analysis.

- The Forward Simulation Analysis (FSA) method, which iteratively refines

Conceptual Diagrams

Diagram: Finite-Size Effects Correction Workflow in MD Simulations

This diagram illustrates the logical process for correcting finite-size effects in diffusion coefficients obtained from MD simulations of concentrated solutions, based on the cited research [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Key Experimental Approaches

| Item / Reagent | Function / Application | Example Context |

|---|---|---|

| Artificial Mucus | A synthetic hydrogel that mimics the biochemical and physical (viscosity, mesh network) properties of native pulmonary mucus for in vitro drug diffusion studies. | Used as a diffusion barrier to measure the diffusivity of asthma drugs like Theophylline and Albuterol [9]. |

| High-Purity Alloy Elements (Al, Cu, V) | Serve as the base materials for fabricating binary and ternary alloy samples used in the diffusion couple method. Purity (e.g., 99.99%) is critical to avoid contamination that can skew diffusion results. | Used to cast FCC Al-Cu-V alloys for studying interdiffusion coefficients and atomic mobilities [7]. |

| Diffusion Couple Assembly Jig | A device, often used with a hydraulic press, to apply uniform pressure and create intimate, void-free contact between the two surfaces of a diffusion couple. | Essential for preparing high-quality samples in metallurgical diffusion studies [7]. |

| Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA) | An indirect method to determine the average diffusion coefficient of volatile components in polymer phases by measuring mass loss as a function of time under controlled temperature. | Used to study the desorption of toluene from saturated HDPE and PP, and for post-industrial plastic waste melt [8]. |

| Pressure Decay Apparatus (PDA) | An indirect method used to validate TGA results by monitoring the pressure drop in a closed cell as a volatile component desorbs from a polymer sample. | Provided comparable results to TGA for toluene diffusion in HDPE and PP, validating the TGA method [8]. |

| Anticancer agent 213 | Anticancer agent 213, MF:C38H35N7O5, MW:669.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| cis-4-Br-2,5-F2-PCPA | cis-4-Br-2,5-F2-PCPA, MF:C9H8BrF2N, MW:248.07 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

FAQ: Fundamental Concepts and Definitions

What is the core difference between self-diffusion and mutual diffusion? Self-diffusion refers to the motion of a single, tagged particle (or molecule) within a uniform chemical environment, tracing its Brownian motion. In contrast, mutual diffusion describes the collective, net transport of multiple chemical species down their concentration gradients in a mixture.

- Self-Diffusion: This is the movement of a tracer particle in a homogeneous medium, such as a single water molecule moving in pure water. It characterizes the intrinsic random motion of particles in the absence of a chemical potential gradient.

- Mutual Diffusion: Also known as collective diffusion, this process occurs in mixtures where there is a net flow of components to eliminate concentration differences. It is the macroscopic diffusion described by Fick's first law [1].

Can the coefficients for self-diffusion and mutual diffusion be equal? Under specific conditions, yes. For example, in a highly idealized binary system where components are similar and interactions are negligible, the coefficients can be comparable. A study on small molecules in curdlan hydrogels found that both self- and mutual-diffusion coefficients were similar and reduced by 30% compared to aqueous solutions, primarily due to molecular-level interactions rather than the gel's porous structure [10]. However, in most real systems, especially non-ideal mixtures or those with significant interparticle interactions, the values differ [11].

How do interparticle interactions affect these diffusion types differently? Interparticle interactions can drive self-diffusion and mutual diffusion in opposite directions. Theoretical work on membrane proteins has shown that:

- Self-diffusion is inhibited by all types of interactions: hard-core repulsions, soft repulsions, and soft repulsions with weak attractions [11].

- Mutual diffusion is inhibited by attractive interactions but can be enhanced by repulsive interactions [11]. This disparate response is a key reason why different experimental techniques (e.g., fluorescence recovery after photobleaching vs. postelectrophoresis relaxation) can yield different diffusion coefficients for the same system.

FAQ: Experimental Design and Measurement

What are the primary experimental techniques for measuring each diffusion type? Different techniques are optimized for measuring self-diffusion versus mutual diffusion, though some methods can characterize both.

- For Self-Diffusion: Pulsed Field Gradient (PFG) NMR spectroscopy is a highly suitable technique. It measures the mean-square displacement of molecules over time [10] [1] [12].

- For Mutual Diffusion:

- Taylor Dispersion Method: This is a widely used technique where a pulse of solution is injected into a solvent flowing laminarly through a capillary tube. The dispersion of the pulse is measured at the outlet, often via a differential refractive index detector, to determine the mutual diffusion coefficient [3].

- NMR Profiling: This method can determine mutual diffusion coefficients and can be used alongside PFG-NMR on the same system under identical conditions [10].

- Interferometric Methods: Techniques like Gouy and Rayleigh interferometry are also used, though Taylor dispersion is now more common [3].

My molecular dynamics (MD) simulations show system-size dependent diffusion coefficients. Why, and how can I correct for this? Finite-size effects are a well-known artifact in MD simulations because the periodic boundary conditions influence hydrodynamic interactions.

- Cause: Computed self-diffusivities scale linearly with the inverse of the simulation box length (1/L). The finite size of the simulation box affects the hydrodynamic self-interactions of particles [1].

- Correction for Self-Diffusion: The Yeh-Hummer (YH) correction is used to extrapolate to the thermodynamic limit [1]: ( D{i,self}^{\infty} = D{i,self} + \frac{kB T \xi}{6 \pi \eta L} ) where ( D{i,self}^{\infty} ) is the corrected self-diffusion coefficient, ( k_B ) is Boltzmann's constant, T is temperature, η is shear viscosity, L is the box length, and ξ is a constant (2.837297 for cubic boxes) [1].

- Correction for Mutual Diffusion: A finite-size correction for Maxwell-Stefan (MS) diffusivities has also been proposed. This correction depends not only on box size, temperature, and viscosity but also strongly on the thermodynamic factor, which measures the non-ideality of the mixture. For systems near demixing, this correction can be very significant [1].

How does the thermodynamic factor relate mutual and self-diffusion? For binary mixtures, the Darken equation provides a fundamental link: ( D = (xB DA^* + xA DB^) (1 + \frac{\partial \ln \gamma}{\partial \ln x}) ) Here, ( D ) is the mutual diffusion coefficient, ( x_A ) and ( x_B ) are mole fractions, ( D_A^ ) and ( D_B^* ) are the self-diffusion coefficients, and the term ( (1 + \frac{\partial \ln \gamma}{\partial \ln x}) ) is the thermodynamic factor (Γ) [13]. This equation shows that mutual diffusion is influenced by both the weighted average of self-diffusion coefficients and the thermodynamics of the mixture.

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Issues

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Discrepancy between diffusion coefficients from different measurement techniques. | 1. Techniques are measuring different types of diffusion (self vs. mutual) [11].2. Strong interparticle interactions are affecting self and mutual diffusion differently [11]. | Identify which diffusion type your technique measures. Use a method like NMR that can measure both in the same system to ensure comparability [10]. |

| Diffusion coefficients from MD simulations are overestimated compared to experimental values. | Finite-size effects in the simulation. The limited number of molecules in the periodic box artificially enhances diffusivity [1]. | Apply the appropriate finite-size correction (e.g., Yeh-Hummer for self-diffusion or the proposed correction for MS diffusion) to extrapolate to the thermodynamic limit [1]. |

| Non-parabolic growth behavior in diffusion-controlled layer growth experiments (e.g., nitriding). | Assuming a diffusion zone of infinite size, while the real sample has finite dimensions [14]. | Implement a model that incorporates a finite-size diffusion zone and uses total mass balance to correct the estimated effective diffusion coefficients [14]. |

| Large variations in measured solid-phase diffusion coefficients for battery materials (e.g., using GITT). | 1. Underlying assumption of linear diffusion instead of realistic 3D radial diffusion.2. Nonlinearity of the open-circuit potential [15]. | Employ the Surface Concentration Potential Response (SCPR) method with a realistic 3D radial diffusion model to more accurately determine the diffusion coefficient [15]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Diffusion Studies |

|---|---|

| Curdlan Hydrogels | A bacterial polysaccharide used to create a porous matrix for studying how confinement and molecular interactions affect the diffusion of small molecules like phosphates and glucose-6-phosphate [10]. |

| AOT Surfactant | Used to form water-in-oil microemulsions, creating nano-droplets that act as pseudo-binary systems for studying mutual diffusion in structured fluids [13]. |

| D(+)-Glucose & D-Sorbitol | Model saccharides used in binary and ternary aqueous systems to study concentration and temperature dependence of mutual diffusion coefficients, relevant for industrial process design like sorbitol production [3]. |

| Lennard-Jones Systems | Simple model particles used in molecular dynamics simulations to establish foundational knowledge and verify theoretical corrections for finite-size effects in diffusion coefficients [1]. |

| NCM523 (Lithium Nickel Cobalt Manganese Oxide) | A common cathode material in lithium-ion batteries, used as a model system for developing and validating accurate methods to determine solid-phase diffusion coefficients [15]. |

| Ac-VDQQD-PNA | Ac-VDQQD-PNA, MF:C31H43N9O14, MW:765.7 g/mol |

| Gpx4-IN-16 | Gpx4-IN-16, MF:C29H24N4O3S2, MW:540.7 g/mol |

Workflow and Conceptual Diagrams

Experimental Workflow for Diffusion Coefficient Determination

This diagram outlines a general workflow for determining diffusion coefficients, integrating insights from multiple experimental contexts.

Relationship Between Diffusion Types and Key Concepts

This conceptual diagram illustrates the factors connecting and differentiating self-diffusion and mutual diffusion.

FAQs: Understanding Finite-Size Effects

What are finite-size effects (FSEs) in molecular dynamics simulations? Finite-size effects are artificial disturbances or inaccuracies that occur in molecular dynamics (MD) simulations when the size of the simulated system (the simulation box) is too small to properly represent bulk material behavior [16]. In such cases, particles interact unnaturally with their own periodic images, leading to corrupted data, particularly for transport properties like diffusion coefficients [16].

Why are accurate diffusion coefficients critical in drug development? In drug discovery, accurately determining the diffusion coefficient of a system is fundamental for understanding small-scale, short- and long-range interactions [16]. These coefficients describe how quickly molecules move and interact within a specific chemical environment, which influences drug dissolution, binding, and distribution processes. Errors in these values can cost theorists, wet-lab chemists, and drug-discovery researchers significant time, resources, and money [16].

How do I know if my simulation is suffering from significant finite-size effects? A key indicator is an unrealistic lowering of the computed diffusion coefficient [16]. This occurs because particles in a small box artificially interact with their own periodic images, effectively disrupting normal transport mechanisms [16]. The diffusion coefficient demonstrates a predictable 1/L finite-size effect correction factor based on the box length, L [16].

What is the relationship between simulation box size and the accuracy of the diffusion coefficient? As the simulation box length (L) increases, finite-size effects are reduced, bulk behavior is more accurately modeled, and the accuracy of the diffusion coefficient (D) increases [16]. The correction for this effect follows a 1/L relationship [17].

Can FSEs be corrected, or is a larger system size the only solution? While increasing system size is one solution, a common and effective mitigation strategy is the linear extrapolation of the diffusion coefficient from simulations run with multiple different box sizes to the infinite-size limit [16]. A generalized finite-size correction term, building on the Yeh and Hummer (YH) correction, can be applied to mutual diffusion coefficients in multicomponent mixtures [17].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Unphysically Low Diffusion Coefficients

Problem The self-diffusion or mutual diffusion coefficients obtained from your MD simulation are significantly lower than expected or reported in experimental literature.

Diagnosis This is a classic symptom of a simulation box that is too small [16]. The particles in your system are interacting with their own periodic images, which restricts their motion and leads to an underestimation of diffusion [16].

Solution

- Run Size-Series Simulations: Perform the same simulation with progressively larger box sizes (e.g., 250, 500, 1000, and 2000 molecules) [18] [17].

- Extrapolate to the Thermodynamic Limit: Plot the computed diffusion coefficients against the inverse of the box length (1/L). Perform a linear extrapolation to the y-intercept (where 1/L = 0, representing an infinite system) to obtain the corrected diffusion coefficient [16].

- Apply a Analytic Correction: For self-diffusivity, apply the Yeh and Hummer (YH) correction [17]:

Di,self∞ = Di,selfMD - (kBT ξ) / (6 π η L)whereDi,self∞is the corrected self-diffusivity in the thermodynamic limit,Di,selfMDis the value computed from MD, kB is the Boltzmann constant, T is temperature, η is the shear viscosity, L is the box length, and ξ is a constant dependent on the box shape (ξ=2.837297 for a cubic box) [17].

Issue 2: FSEs in Complex Multicomponent Mixtures (e.g., Deep Eutectic Solvents)

Problem Predicting bulk properties like diffusivity in complex, eco-friendly solvents like caprylic acid-based Deep Eutectic Solvents (DESs) is unreliable, especially under nanoscale confinement, which is relevant for drug delivery applications [18].

Diagnosis The local structuring and dynamic behavior of DES components are highly sensitive to finite particle size effects and confinement, leading to significant deviations from bulk properties [18].

Solution

- Validate with a Sufficient System Size: Research indicates that systems with 1000 particles can provide satisfactory predictions of thermophysical properties, as the self-diffusion coefficient from MD begins to approach values observed in the thermodynamic limit [18].

- Account for Confinement Explicitly: When modeling applications involving nanotubes or other nanoscale structures, the confinement itself must be part of the simulation model, as it significantly influences structural properties and hydrogen bonding networks [18].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Detailed Methodology: Correcting Finite-Size Effects in Diffusion Coefficients

This protocol outlines the steps for obtaining diffusion coefficients at the thermodynamic limit using a system-size extrapolation approach [16] [17].

Step-by-Step Guide:

- System Preparation: Create an initial configuration of your system (e.g., a liquid mixture) using tools like PACKMOL [17]. Define the force field parameters for all molecules [17].

- Define Simulation Box Sizes: Choose a range of system sizes. A recommended set includes boxes containing 250, 500, 1000, and 2000 molecules to adequately sample the size dependence [18] [17].

- Configure MD Simulation Parameters:

- Software: Use a package like LAMMPS [17].

- Boundary Conditions: Apply Periodic Boundary Conditions (PBCs) in all three dimensions [16].

- Ensemble: Use an NPT ensemble to maintain constant Number of particles, Pressure, and Temperature.

- Thermostat/Barostat: Select appropriate algorithms (e.g., Nosé-Hoover) to maintain temperature and pressure.

- Interaction Cut-offs: Ensure your non-bonded interaction cut-off radius is less than half the length of your smallest simulation box to avoid violating the minimum image convention [16].

- Simulation Time: Run long enough to achieve proper equilibration and gather good statistics for mean-squared displacement (MSD) or velocity autocorrelation function (VACF). A total simulation length of 100 ns or more is common [17].

- Run Simulations and Calculate Diffusion: For each system size, run multiple independent simulations. Calculate the self-diffusion coefficient from the slope of the mean-squared displacement (MSD) vs. time or via the Green-Kubo relation from the velocity autocorrelation function [16] [17].

- Extrapolation:

- For each system size

i, compute1/L_i, whereL_iis the box length. - Plot the calculated diffusion coefficient

D_iagainst1/L_i. - Perform a linear regression. The y-intercept of the best-fit line corresponds to the diffusion coefficient at the thermodynamic limit (

D∞).

- For each system size

Quantitative Data on System Size Effects

Table 1: Impact of Simulation System Size on Self-Diffusion Coefficient [18] [17]

| Number of Molecules | Approximate Box Length (L) * | Relative 1/L | Computed Self-Diffusivity (D^MD) | Corrected Self-Diffusivity (D^∞) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 250 | Smallest | Largest | Most Underestimated | Requires largest YH correction |

| 500 | Intermediate | Intermediate | Underestimated | Requires intermediate correction |

| 1000 | Intermediate | Intermediate | Approaches D^∞ | Requires small correction |

| 2000 | Largest | Smallest | Closest to D^∞ | Requires minimal correction |

Note: Actual box length depends on system density. The key relationship is that correction is a function of 1/L [16].

Table 2: Finite-Size Correction Formulas for Different Diffusion Types

| Diffusion Type | System Composition | Finite-Size Effect Correction Formula | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Self-Diffusion | Pure and Mixed Fluids | D_self∞ = D_self^MD - (k_B T ξ) / (6 π η L) |

[17] |

| Mutual (Fick) Diffusion | Binary Mixtures | D_Fick∞ ≈ D_Fick^MD - (k_B T ξ) / (6 π η L) (Same as self-diffusion correction) [17] |

|

| Maxwell-Stefan (MS) Diffusion | Multicomponent Mixtures | A generalized correction exists, derived from the finite-size effects of the Fick matrix and the matrix of thermodynamic factors[Γ] [17] |

Workflow Visualization

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Tools for Simulating and Correcting Finite-Size Effects

| Item / Resource | Function / Description | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| MD Simulation Software | Open-source software package used to perform molecular dynamics simulations. It is highly flexible and can model a wide range of materials. | LAMMPS (used in cited research) [17] |

| System Builder | A software tool for building initial molecular configurations and packing molecules into simulation boxes with defined composition and density. | PACKMOL (used in cited research) [17] |

| Analysis Plugin | A plugin for MD software that assists in computing transport properties and thermodynamic factors from simulation trajectories. | OCTP plugin (used with LAMMPS) [17] |

| Visualization Tool | A molecular visualization program used for simulating, visualizing, and analyzing molecular systems. It can also help generate input files for MD software. | VMD (VMD) [17] |

| Yeh and Hummer (YH) Correction | An analytical hydrodynamic correction term that must be added to self-diffusivities computed from EMD to obtain diffusivities at the thermodynamic limit. Valid for pure components and mixtures [17]. | D_self∞ = D_self^MD - (k_B T ξ) / (6 π η L) [17] |

| Generalized Multicomponent Correction | A derived correction term for mutual diffusion coefficients in multicomponent mixtures, extending the principles of the YH correction to more complex systems [17]. | Based on finite-size effects of the Fick matrix and the matrix of thermodynamic factors[Γ] [17] |

| Thermodynamic Factor ([Γ]) Calculation | A matrix whose elements describe the deviation from ideal mixing behavior in a solution. It is crucial for converting between Fick and Maxwell-Stefan diffusion coefficients [17]. | Computed from Kirkwood-Buff integrals or activity coefficient models [17] |

| Neoeuonymine | Neoeuonymine, MF:C36H45NO17, MW:763.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Lsd1-IN-23 | Lsd1-IN-23, MF:C19H13BrClN5O2S, MW:490.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Practical Correction Methods: Implementing Yeh-Hummer and Beyond

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the Yeh-Hummer correction, and why is it critical for my self-diffusion calculations?

The Yeh-Hummer (YH) correction is an analytical term that compensates for the finite-size effects inherent in calculating self-diffusion coefficients ((D{i,self})) from Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations with periodic boundary conditions. These simulations systematically underestimate the true self-diffusivity (the value at the thermodynamic limit, (D{i,self}^\infty)) because long-range hydrodynamic interactions are truncated. The YH correction accounts for these omitted interactions, providing a more accurate value [1] [19]. The correction is expressed as: [ D{i,self}^\infty = D{i,self} + D{YH} ] where the correction term (D{YH}) is given by: [ D{YH} = \frac{\zeta kB T}{6 \pi \eta L} ] In this equation, (\zeta) is a dimensionless constant (~2.837297 for cubic boxes), (k_B) is Boltzmann's constant, (T) is temperature, (\eta) is the shear viscosity of the system, and (L) is the box length [1] [19]. Without this correction, your reported diffusion coefficients can contain a systematic error, which for systems of around 2000 molecules can be approximately 10% [19].

FAQ 2: For which types of diffusion coefficients and systems should I apply the Yeh-Hummer correction?

The Yeh-Hummer correction was originally derived and is most straightforwardly applied to self-diffusion coefficients [1] [19]. Self-diffusion refers to the movement of a tagged particle in a uniform medium due to Brownian motion [20] [1].

- Applicability: It has been successfully verified for a wide range of systems, including simple Lennard-Jones fluids, water, COâ‚‚, and various pure liquids and mixtures like n-alkanes [21] [19].

- Mutual Diffusion: Finite-size effects also impact mutual diffusion coefficients (Maxwell-Stefan and Fick diffusivities). Recent studies have proposed extensions of the YH approach to correct these collective diffusion coefficients, noting that the dependency on system size is also strong, especially for non-ideal mixtures [1].

- Important Caution: The correction may not be accurate for systems with strong electrostatic interactions, such as charged molecules in a polar or ionic medium, and might require rescaling [1]. Furthermore, some force fields parameterized to target transport properties may inadvertently mask the finite-size effect. Applying the YH correction in such cases could paradoxically worsen the agreement with experimental data [19].

FAQ 3: What specific input data do I need to calculate the Yeh-Hummer correction for my simulation?

Applying the YH correction requires several key pieces of data, typically obtainable from your MD simulation.

Table: Input Parameters for the Yeh-Hummer Correction

| Parameter | Symbol | Description | Common Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Simulation Box Length | (L) | Side length of the primary cubic simulation cell. | Directly from simulation input/output (e.g., LAMMPS log files). |

| System Temperature | (T) | Absolute temperature of the simulation. | Directly from simulation parameters. |

| System Shear Viscosity | (\eta) | Shear viscosity of the fluid mixture at the simulated state. | Calculated from the simulation using the Green-Kubo relation (eq. 3) or the Einstein relation, from off-diagonal components of the stress tensor [1]. |

| Boltzmann Constant | (k_B) | Fundamental physical constant. | (1.380649 \times 10^{-23} \ J \cdot K^{-1}) |

| YH Constant | (\zeta) | Dimensionless constant for 3D periodic cubic boxes. | 2.837297 [1] [19] |

FAQ 4: The YH correction made my results less accurate compared to experiment. What could be the cause?

This is a known issue and often points to one of two underlying problems [19]:

- Force Field Inaccuracies: The molecular force field used in your simulation may itself be a source of error. Some force fields are parameterized to reproduce thermodynamic equilibrium properties but may not accurately capture transport dynamics. If a force field inherently overestimates self-diffusion, the finite-size effect might accidentally make the uncorrected result ((D_{i,self})) look closer to experiment. Applying the positive YH correction then reveals the underlying inaccuracy of the force field [19].

- Incorrect Viscosity: The YH correction is linearly dependent on the simulated shear viscosity ((\eta)). An inaccurate viscosity estimate will directly propagate an error into the corrected diffusivity. You should verify that your simulation reliably reproduces the system's viscosity [1].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Correcting Finite-Size Effects in Self-Diffusion Calculations

Problem: Self-diffusion coefficients calculated from MD simulations show a strong, unrealistic dependency on the size of the simulation box (N or L). The values are underestimated compared to the experimental thermodynamic limit [1] [19].

Solution: Apply the Yeh-Hummer correction and validate the force field.

- Calculate Required Inputs: From your production simulation trajectory, calculate the system's shear viscosity ((\eta)) using an equilibrium method (Green-Kubo or Einstein) [1].

- Compute the Correction: Use the equation (D{YH} = \frac{\zeta kB T}{6 \pi \eta L}) with (\zeta = 2.837297).

- Apply the Correction: Obtain the corrected self-diffusion coefficient: (D{i,self}^\infty = D{i,self} + D_{YH}).

- Validate with a Robust Force Field: Ensure your results are physically sound by testing with a force field known to accurately predict transport properties for your system. For organic liquids and hydrocarbons, all-atom OPLS4 has shown excellent agreement with experimental self-diffusion data [21]. Be aware that united-atom models may exhibit biases, such as caging effects or inaccurate dihedral distributions, that affect diffusion [19].

The following workflow outlines the systematic procedure for addressing this issue:

Issue 2: High Uncertainty in Corrected Diffusivity Due to Viscosity Calculation

Problem: The calculated YH correction term has high variability, leading to an unreliable final self-diffusion coefficient. This is often traced to noise in the viscosity calculation [1].

Solution: Improve the statistical accuracy of the viscosity measurement.

- Prolong Simulation Time: Viscosity is a collective property that typically requires longer simulation times for convergence than self-diffusion. Extend your production run to improve sampling.

- Average Multiple Components: Use all three independent off-diagonal components of the stress tensor (Pxy, Pxz, Pyz) to calculate three viscosity values and report the average [1].

- Use Block Averaging: Calculate the viscosity over multiple, independent blocks of your trajectory and compute the mean and standard error.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table: Key Computational Tools for Self-Diffusion Studies with YH Correction

| Tool / Reagent | Function / Description | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| Stable Isotope Enrichment | Enables direct measurement of self-diffusion in host materials (e.g., Ge, Si) by creating isotope superlattices [20]. | Provides the most fundamental data for validating simulation methodologies and understanding vacancy-mediated diffusion mechanisms in solids [20]. |

| Pulsed-Field Gradient NMR | Primary experimental technique for measuring self-diffusion coefficients in liquids [21] [19]. | Serves as the gold standard for validating MD simulation results and the accuracy of the YH-corrected diffusivities [21]. |

| OPLS4 Force Field | An all-atom force field for molecular dynamics simulations [21]. | Demonstrated excellent predictive performance for self-diffusion coefficients of chemically diverse pure liquids, making it a strong choice for reliable results [21]. |

| Equilibrium MD (EMD) | A class of MD simulations where transport coefficients are computed from time-correlation functions at equilibrium [1]. | The standard method for computing both self-diffusion (via MSD) and viscosity (via stress tensor autocorrelation) needed for the YH correction [1]. |

| Einstein Formulation | A method within EMD that calculates diffusivity from the slope of the Mean Squared Displacement (MSD) over time [1] [19]. | Preferred for its robustness and lower noise compared to the Green-Kubo method; less sensitive to integration limits [19]. |

| D-(+)-Cellotriose | D-(+)-Cellotriose, MF:C18H32O16, MW:504.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Borapetoside F | Borapetoside F, MF:C27H34O11, MW:534.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What are finite-size effects in Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations? In MD simulations, the number of molecules is orders of magnitude lower than in real, macroscopic systems (the thermodynamic limit). This finite system size, combined with the use of periodic boundary conditions, affects computed transport properties, including diffusion coefficients. For self-diffusion coefficients, a strong dependency on the number of molecules, scaling linearly with ( N^{-1/3} ) (where ( N ) is the number of molecules), has been observed [1] [22].

2. Why do finite-size effects matter for Maxwell-Stefan (MS) diffusion coefficients? Finite-size effects lead to significant deviations between MS diffusivities computed from MD simulations and the true values at the thermodynamic limit. The simulated (finite-size) MS diffusivity can be much lower than the corrected value, especially for mixtures close to demixing. In these cases, the required finite-size correction can be even larger than the simulated diffusivity itself. Ignoring these effects can result in unreliable data [1].

3. What is the relationship between Fick and Maxwell-Stefan diffusivities? The Fick and Maxwell-Stefan diffusion coefficients are related by the thermodynamic factor (( \Gamma )), which measures the non-ideality of the mixture. For a binary mixture, the relationship is given by ( D{\text{Fick}} = \Gamma \times Ä{\text{MS}} ). The MS formulation describes diffusion as a balance between the thermodynamic driving force (chemical potential gradient) and molecular friction, while the Fick formulation relates mass flux directly to concentration gradients [1] [23].

4. What correction is used for self-diffusion coefficients? The Yeh and Hummer (YH) correction is used for self-diffusion coefficients. The self-diffusivity in the thermodynamic limit (( D{i,self}^{\infty} )) is obtained from the finite-size value (( D{i,self} )) computed by MD via [1] [17]: [ D{i,self}^{\infty} = D{i,self} + D{YH} ] [ D{YH} = \frac{kB T \xi}{6 \pi \eta L} ] where ( kB ) is Boltzmann's constant, ( T ) is temperature, ( \eta ) is shear viscosity, ( L ) is the box length, and ( \xi ) is a constant (2.837297 for cubic boxes).

5. How is the finite-size correction for binary MS diffusivities derived? The correction for binary MS diffusivities is an extension of the YH correction, incorporating the thermodynamic factor. It is given by [1] [17]: [ Ä{MS}^{\infty} = Ä{MS}^{MD} + \Gamma \frac{kB T \xi}{6 \pi \eta L} ] Here, ( Ä{MS}^{\infty} ) is the MS diffusivity at the thermodynamic limit, ( Ä_{MS}^{MD} ) is the value obtained from MD simulation, and ( \Gamma ) is the thermodynamic factor. This shows that the non-ideality of the mixture strongly influences the magnitude of the finite-size effect.

6. Does the system size affect the shear viscosity computed from MD? No, studies have shown that the shear viscosity (( \eta )) of the system, required for the YH correction, is independent of the system size. Therefore, it can be reliably computed from a single system size without correction [1].

7. For which types of mixtures are finite-size effects most critical? Finite-size effects are particularly pronounced for non-ideal mixtures and those close to demixing. The more non-ideal the mixture (i.e., the further the thermodynamic factor ( \Gamma ) deviates from 1), the larger the required correction for the MS diffusivity will be [1].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Corrected MS Diffusivity is Much Larger than the Simulated Value

Problem: After applying the finite-size correction, the value of ( Ä{MS}^{\infty} ) is significantly larger than ( Ä{MS}^{MD} ), or even negative.

Solutions:

- Check the Thermodynamic Factor: This problem often occurs for highly non-ideal mixtures, especially those near phase separation (demixing). Verify the calculation of the thermodynamic factor ( \Gamma ), as it amplifies the correction term. A small or negative ( \Gamma ) can lead to a very large correction [1].

- Verify System Homogeneity: Ensure the mixture is homogeneous and stable under the simulated conditions. The correction formalism assumes a homogeneous phase [1].

- Increase System Size: If the correction is implausibly large, perform simulations with a larger number of molecules (N). The finite-size effect diminishes as system size increases, and results from larger systems are more reliable [1] [22].

Issue 2: Large Uncertainty in Corrected Diffusion Coefficients

Problem: The final corrected diffusivity has high statistical uncertainty.

Solutions:

- Increase Sampling: Perform a larger number of independent simulation runs. The study on ternary molecular mixtures, for instance, used 100 independent simulations to achieve low statistical uncertainties [17].

- Check Viscosity Calculation: Ensure the shear viscosity ( \eta ) is computed with high precision, as it appears in the correction term. Use long simulation runs and multiple independent components of the stress tensor for averaging [1].

- Validate Self-Diffusion Correction: First, verify that the YH correction properly extrapolates the self-diffusion coefficients of all components to the thermodynamic limit. This is a prerequisite for the MS correction [17].

Issue 3: How to Handle Finite-Size Effects in Multicomponent Mixtures

Problem: The user is simulating a ternary or higher-order mixture and needs to correct mutual diffusivities.

Solutions:

- Apply the Generalized Matrix Formulation: For multicomponent systems, the finite-size effects on the Fick diffusion matrix are such that only the diagonal elements require correction. The generalized correction involves the Yeh-Hummer term and the matrix of thermodynamic factors [17].

- Eigenvalue Analysis: It has been shown that the finite-size effects on the matrix of Fick diffusivities are confined to its eigenvalues. The eigenvector matrix is independent of system size. This insight can be used for reliable extrapolation [17].

- Consult Recent Reviews: Refer to comprehensive reviews on finite-size effects for the latest generalized protocols for ternary and quaternary mixtures [22].

The table below summarizes the essential formulas for finite-size corrections in binary systems.

Table 1: Finite-size correction formulas for diffusion coefficients in binary systems.

| Diffusion Coefficient | Finite-Size Value from MD | Correction Formula (for Thermodynamic Limit) | Key Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Self-Diffusivity (( D_{i,self} )) | ( D_{i,self}^{MD} ) | ( D{i,self}^{\infty} = D{i,self}^{MD} + \dfrac{k_B T \xi}{6 \pi \eta L} ) [1] | ( \eta ): Shear viscosity( L ): Box length( \xi ): Constant (2.837) |

| Maxwell-Stefan Diffusivity (( Ä_{MS} )) | ( Ä_{MS}^{MD} ) | ( Ä{MS}^{\infty} = Ä{MS}^{MD} + \Gamma \dfrac{k_B T \xi}{6 \pi \eta L} ) [1] [17] | ( \Gamma ): Thermodynamic factor |

| Fick Diffusivity (( D_{Fick} )) | ( D_{Fick}^{MD} ) | ( D{Fick}^{\infty} = D{Fick}^{MD} + \dfrac{k_B T \xi}{6 \pi \eta L} ) [17] | Derived from ( D{Fick} = \Gamma \times Ä{MS} ) |

Experimental Protocol: Correcting MS Diffusivity in a Binary Mixture

Below is a detailed step-by-step methodology for obtaining a finite-size corrected Maxwell-Stefan diffusion coefficient from Molecular Dynamics simulations.

Objective: To compute the Maxwell-Stefan diffusion coefficient for a binary mixture at the thermodynamic limit.

Required Reagents & Computational Tools: Table 2: Essential research reagents and computational solutions for MD-based diffusion calculations.

| Item | Function / Description |

|---|---|

| MD Software (e.g., LAMMPS) | Open-source software package used to perform the molecular dynamics simulations [17]. |

| Force Field Parameters | Set of potentials and constants defining intermolecular and intramolecular interactions. |

| Configuration Builder (e.g., PACKMOL) | Tool for generating initial molecular configurations for the simulation box [17]. |

| Shear Viscosity (( \eta )) | Transport property of the fluid, computed from the autocorrelation of the off-diagonal components of the stress tensor [1]. |

| Thermodynamic Factor (( \Gamma )) | Measure of the non-ideality of the mixture, computable from Kirkwood-Buff integrals or activity coefficient models [1] [24]. |

Workflow Diagram

The following diagram visualizes the sequence of key stages in the correction process.

Step-by-Step Instructions:

System Preparation: Define the binary mixture of interest (components A and B). Create initial simulation boxes containing different total numbers of molecules (N), for example, N=250, 500, 1000, and 2000, using a tool like PACKMOL [17]. Ensure the composition is the same across all system sizes.

MD Simulation Setup: Use software like LAMMPS to perform Equilibrium Molecular Dynamics (EMD) simulations.

- Employ appropriate force fields and periodic boundary conditions.

- Use a time step of 1-2 fs for molecular systems.

- Ensure simulations are long enough (e.g., >50-100 ns) for good statistical averaging of transport properties.

- Perform multiple independent simulation runs (e.g., 100) for each system size to reduce statistical uncertainty [17].

Property Calculation:

- Maxwell-Stefan Diffusivity (( Ä_{MS}^{MD} )): Compute via the Onsager coefficients using the Einstein formulation based on the cross-correlation of molecular displacements [1].

- Shear Viscosity (( \eta )): Calculate from the autocorrelation function of the off-diagonal elements of the stress tensor (eq 3 in [1]). This property is system-size independent.

- Thermodynamic Factor (( \Gamma )): Determine for the binary mixture. This can be obtained from activity coefficient models (e.g., Wilson, NRTL, UNIQUAC) or, more rigorously, from MD simulations using Kirkwood-Buff integrals [24].

Application of Finite-Size Correction:

- For each system size, calculate the box length ( L ) from the simulation box volume (( L = V^{1/3} )).

- Apply the correction formula for MS diffusivity: [ Ä{MS}^{\infty} = Ä{MS}^{MD} + \Gamma \frac{k_B T \xi}{6 \pi \eta L} ]

- Use the constant ( \xi = 2.837297 ) for a cubic simulation box [1].

Validation and Extrapolation:

- Plot the computed ( Ä{MS}^{MD} ) and the corrected ( Ä{MS}^{\infty} ) against ( 1/L ).

- The values of ( Ä_{MS}^{\infty} ) for different system sizes should cluster closely together, validating that the correction successfully removes the system-size dependency. The result is a reliable MS diffusion coefficient at the thermodynamic limit.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What are the primary sources of error when determining diffusion coefficients in multicomponent systems? Research indicates that several factors introduce error into diffusion coefficient measurements. For MRI-derived Apparent Diffusion Coefficient (ADC) values, lower ADC values consistently show increased error and lower signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) [25]. In molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, the uncertainty of a computed diffusion coefficient depends not only on the input simulation data but also on the specific statistical estimator and data processing decisions used during analysis [2]. Furthermore, all simulation-derived diffusivities exhibit system-size dependence, requiring appropriate finite-size corrections for quantitative comparison with experimental data [17].

2. How do finite-size effects impact computed diffusion coefficients in molecular simulations?

Finite-size effects significantly impact diffusivities computed from Equilibrium Molecular Dynamics (EMD). Self-diffusivities scale linearly with the inverse of the simulation box length [17]. For mutual diffusion coefficients in multicomponent mixtures, only the diagonal elements of the Fick matrix show system-size dependency and can be corrected using the Yeh and Hummer (YH) term: D_corrected = D_MD + (k_B * T * ξ) / (6 * π * η * L), where k_B is Boltzmann's constant, T is temperature, η is shear viscosity, L is box length, and ξ is a constant depending on box shape (ξ = 2.837297 for cubic boxes) [17]. All Maxwell–Stefan diffusivities also depend on system size, with the required correction depending on the matrix of thermodynamic factors [17].

3. What matrix approaches are used to relate different diffusion coefficient frameworks for multicomponent mixtures?

The relationship between Fick and Maxwell–Stefan diffusivities is governed by matrix equations. For an n-component mixture, the matrix of Fick diffusivities [DFick] is related to the Maxwell–Stefan diffusivities [ÄMS] and the matrix of thermodynamic factors [Γ] through the equation: [D_Fick] = [B]^{-1}[Γ], where [B] is a matrix whose elements are defined in terms of the mole fractions and Maxwell–Stefan diffusivities [17]. Specifically, the diagonal and off-diagonal elements of [B] are given by:

B_ii = x_i / Ä_in + Σ_{k≠i} (x_k / Ä_ik)for i = 1 to n-1B_ij = -x_i (1/Ä_ij - 1/Ä_in)for i ≠j wherex_iare mole fractions andÄ_ijare Maxwell–Stefan diffusivities [17].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Inconsistent ADC Measurements Across Multiple Scanners

Issue: Quantitative ADC measurements show significant variability when performed across different MRI scanners, field strengths, and orientations.

Solution:

- Standardized Phantom Use: Implement a comprehensive quality assurance program using NIST-traceable diffusion phantoms scanned across all institutional scanners [25].

- Orientation Awareness: Avoid sagittal acquisition orientations, which consistently show higher coefficient-of-variation (CoV) across reference ADC values [25].

- Error Anticipation: Account for increased error magnitude at lower ADC values, which is directly related to lower SNR [25].

- Scanner Matching: Utilize quality assurance data to develop advanced scheduling systems that match patients to similarly performing MRI scanners for longitudinal studies [25].

Problem: Significant Finite-Size Effects in Simulated Diffusion Coefficients

Issue: Computed diffusion coefficients from molecular dynamics simulations show strong dependence on simulated system size, preventing direct comparison with experimental values.

Solution:

- Apply YH Correction: Implement the generalized finite-size correction for multicomponent mutual diffusivities. For Fick diffusivities, only the diagonal elements require correction using the YH term [17].

- Eigenvalue Analysis: Perform eigenvalue analysis of the finite-size effects of the matrix of Fick diffusivities. The eigenvector matrix does not depend on simulation box size, while eigenvalues (describing diffusion speed) do require correction [17].

- System Size Validation: Conduct simulations with varying system sizes (e.g., 250, 500, 1000, 2000 molecules) to verify the linear scaling with 1/L and ensure correction validity [17].

- MS Diffusivity Correction: Apply the appropriate finite-size correction to all Maxwell–Stefan diffusivities, which depends on the matrix of thermodynamic factors [17].

Problem: Poor Predictive Power of Mode-Coupling Theory for Binary Mixtures

Issue: Standard mode-coupling theory (MCT) fails to accurately predict the glassy dynamics of binary mixtures, showing discrepancies with simulation results.

Solution:

- Implement Multi-component GMCT: Apply the hierarchical framework of generalized mode-coupling theory (GMCT) extended to multi-component systems [26].

- Hierarchical Improvement: Utilize progressively higher levels of the GMCT hierarchy, as each additional level gradually improves predictive power beyond the previous limit [26].

- Structure Factor Input: Rely on static structure factors S(k) as the sole input for the theory, as all predicted differences in dynamics between systems are encoded in their static structure factors [26].

Quantitative Data Tables

Table 1: ADC Measurement Error Analysis Across Scanner Fleet

| ADC Value Range | Orientation | Coefficient of Variation (CoV) | Error Range | Primary Factor |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower ADC | Sagittal | Highest CoV | Largest Error | Low SNR |

| Lower ADC | Axial/Other | Increased CoV | Large Error | Low SNR |

| Higher ADC | Sagittal | Moderate CoV | Moderate Error | Orientation |

| Higher ADC | Axial/Other | Lowest CoV | Smallest Error | Reference Standard |

Data compiled from multi-scanner study using NIST-traceable phantoms across 23 MRI scanners [25].

Table 2: Finite-Size Correction Factors for Diffusion Coefficients

| Diffusion Coefficient Type | System Size Dependence | Correction Formula | Required Input Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Self-Diffusivity | Scales with 1/L | D_self∞ = D_self_MD + (k_B*T*ξ)/(6*π*η*L) |

η (viscosity), L (box length) |

| Fick Diffusivity (Binary) | Scales with 1/L | D_Fick∞ = D_Fick_MD + (k_B*T*ξ)/(6*π*η*L) |

η, L, Γ (thermodynamic factor) |