Calculating Diffusion Coefficients with ReaxFF MD: A Comprehensive Tutorial from Fundamentals to Advanced Applications

This tutorial provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and scientists on calculating diffusion coefficients using ReaxFF molecular dynamics.

Calculating Diffusion Coefficients with ReaxFF MD: A Comprehensive Tutorial from Fundamentals to Advanced Applications

Abstract

This tutorial provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and scientists on calculating diffusion coefficients using ReaxFF molecular dynamics. Covering foundational concepts, step-by-step methodologies, troubleshooting of common issues, and validation techniques, this resource bridges theoretical knowledge with practical application. Using a Li-ion battery cathode material as a primary case study, we demonstrate the complete workflow from system preparation and simulated annealing to Mean Squared Displacement and Velocity Autocorrelation Function analysis. The content also addresses critical aspects like finite-size effects, parameterization challenges, and temperature extrapolation via the Arrhenius equation, equipping computational researchers with the essential skills to accurately simulate mass transport in complex reactive systems.

Understanding ReaxFF Fundamentals and Diffusion Theory for Reactive Systems

ReaxFF is a powerful computational engine for modeling chemical reactions with atomistic potentials based on the reactive force field approach. It represents a significant advancement in molecular simulation by bridging the gap between quantum mechanical accuracy and classical computational efficiency. Developed by Prof. Adri van Duin and coworkers, ReaxFF has been modernized, parallelized, and greatly optimized by SCM, making it suitable for large-scale simulations of complex reactive systems [1].

Unlike traditional force fields that require predefined connectivity between atoms—thus precluding simulations of reactive events—ReaxFF employs a bond-order formalism where bond order is empirically calculated from interatomic distances. This approach allows for continuous bond formation and breaking during simulations, enabling the study of chemical reactions without the prohibitive computational cost of quantum mechanical methods [2] [3]. The force field describes reactive events through a bond-order formalism, treating electronic interactions driving chemical bonding implicitly, which allows the method to simulate reaction chemistry without explicit QM consideration [2].

The ReaxFF potential energy is calculated as a sum of various contributions [2]:

[E{\text{system}} = E{\text{bond}} + E{\text{over}} + E{\text{angle}} + E{\text{tors}} + E{\text{vdWaals}} + E{\text{Coulomb}} + E{\text{Specific}}]

This comprehensive energy description enables ReaxFF to accurately model both covalent and electrostatic interactions for a diverse range of materials, making it particularly valuable for studying complex processes in materials science, catalysis, and energy storage systems.

Theoretical Framework and Methodology

Bond-Order Formalism

The foundational concept of ReaxFF is its bond-order formalism, which enables the dynamic formation and breaking of chemical bonds during simulations. The bond order between atoms i and j is calculated directly from interatomic distance using the empirical formula [2]:

[ BO{ij} = BO{ij}^\sigma + BO{ij}^\pi + BO{ij}^{\pi\pi} = \exp\left[p{bo1}\left(\frac{r{ij}}{ro^\sigma}\right)^{p{bo2}}\right] + \exp\left[p{bo3}\left(\frac{r{ij}}{ro^\pi}\right)^{p{bo4}}\right] + \exp\left[p{bo5}\left(\frac{r{ij}}{ro^{\pi\pi}}\right)^{p{bo6}}\right] ]

Where BO is the bond order between atoms i and j, rij is interatomic distance, ro terms are equilibrium bond lengths, and p_bo terms are empirical parameters. This equation is continuous, containing no discontinuities through transitions between σ, π, and ππ bond character, which yields a differentiable potential energy surface required for the calculation of interatomic forces [2].

Energy Contributions

ReaxFF incorporates multiple energy contributions to accurately describe molecular interactions:

- Bond Energy (E_bond): A continuous function of interatomic distance that describes the energy associated with forming bonds between atoms.

- Overcoordination Penalty (E_over): Prevents over-coordination of atoms based on atomic valence rules.

- Angle Strain (E_angle): Energy associated with three-body valence angle strain.

- Torsional Strain (E_tors): Energy associated with four-body torsional angle strain.

- Non-bonded Interactions (EvdWaals and ECoulomb): Electrostatic and dispersive contributions calculated between all atoms, regardless of connectivity.

- System Specific Terms (E_Specific): Additional terms for specific systems, such as lone-pair, conjugation, hydrogen binding, and C2 corrections [2].

Force Field Parameterization

ReaxFF requires extensive parameterization to cover the relevant chemical phase space. Parameters are typically trained against quantum mechanical data, often using density functional theory (DFT) calculations. The complexity of the ReaxFF functional form necessitates comprehensive training sets covering bond and angle stretches, activation and reaction energies, equation of state, surface energies, and other relevant properties [3].

Table 1: Key Components of ReaxFF Methodology

| Component | Description | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Bond Order | Calculated from interatomic distances | Determines bond strength and formation/breaking |

| Charge Equilibration | Updated at each step | Describes electrostatic interactions |

| Energy Contributions | Multiple terms (bond, angle, torsion, etc.) | Captures various chemical interactions |

| Parameterization | Trained against QM data | Ensures accuracy for specific chemical systems |

Application Note: Lithium-Ion Diffusion in Battery Materials

Background and Significance

The study of lithium-ion diffusion in electrode materials is crucial for developing advanced batteries with improved performance and faster charging capabilities. ReaxFF enables researchers to simulate these processes at atomistic levels, providing insights that guide material design and optimization. This application note focuses on calculating diffusion coefficients of lithium ions in a Liâ‚€.â‚„S cathode material, following methodologies originally described in the publication "ReaxFF molecular dynamics simulations on lithiated sulfur cathode materials" [4].

Computational Workflow

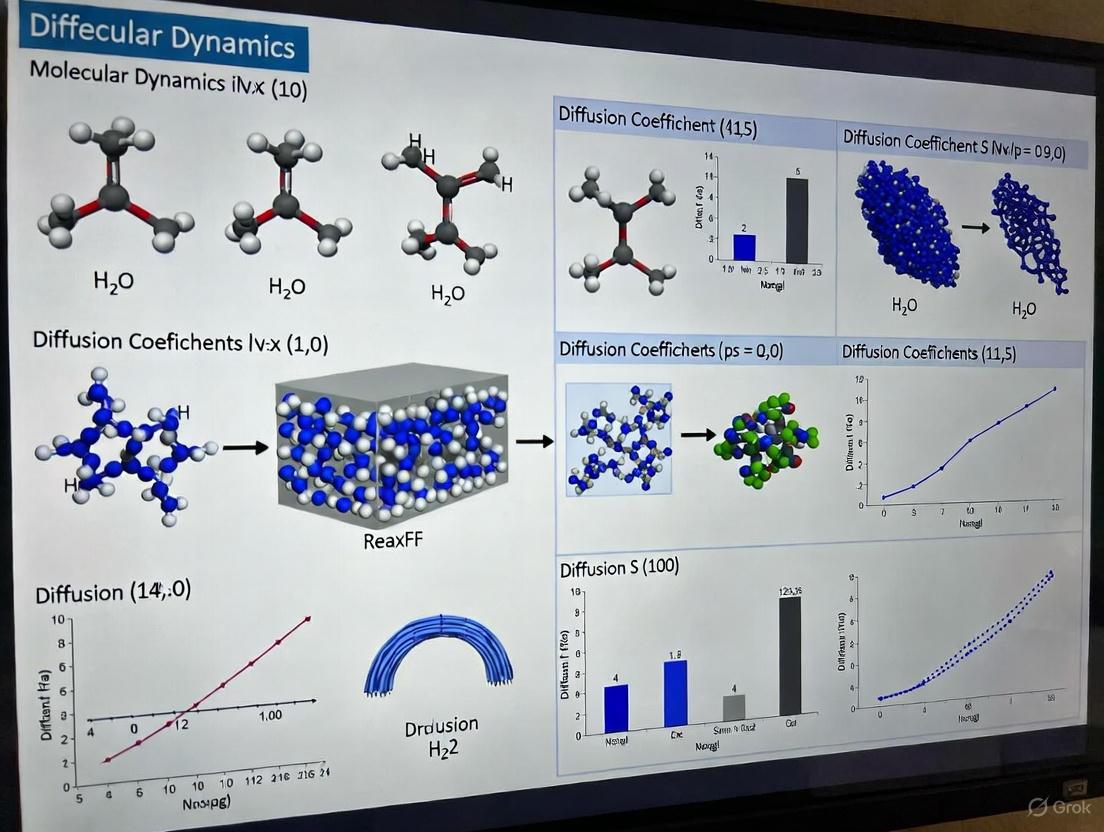

The complete protocol for simulating lithium-ion diffusion coefficients involves multiple stages, from system preparation to data analysis. The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive workflow:

Diagram 1: ReaxFF workflow for diffusion coefficient calculation

Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Components

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for ReaxFF Diffusion Studies

| Component | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| AMS Software Suite | Molecular dynamics simulation platform | Provides ReaxFF engine integrated with analysis tools |

| LiS.ff Force Field | Parameter set for Li-S systems | Specifically parameterized for lithium-sulfur interactions |

| CIF Structure File | Initial crystal structure | α-Sulfur crystal as starting point for system construction |

| Grand Canonical Monte Carlo (GCMC) | Alternative to random insertion | More physically realistic insertion of Li atoms (optional) |

| AMSmovie | Trajectory visualization and analysis | Enables MSD and VACF calculations from MD trajectories |

| 1,8-Octanediol | 1,8-Octanediol, CAS:629-41-4, MF:C8H18O2, MW:146.23 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Kaempferol 3-gentiobioside | Kaempferol 3-gentiobioside, CAS:22149-35-5, MF:C27H30O16, MW:610.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Experimental Protocols

System Preparation and Equilibration

Importing Crystal Structure and Inserting Lithium Atoms

- Open a new AMSinput window and switch to the ReaxFF engine.

- Import the crystal structure: Select File → Import Coordinates and choose the CIF file for α-Sulfur.

- Insert lithium atoms:

- Click on Edit → Builder

- Tick "Use number of molecules"

- Set SMILES code to

[Li](including brackets) - Set N mols to 51 for Liâ‚€.â‚„S composition

- Click "Generate Molecules" and then "Close" [4]

Geometry Optimization with Lattice Relaxation

- Set calculation type: In the main panel, select Task → Geometry Optimization

- Select force field: Click on the folder next to Force Field and select LiS.ff

- Configure lattice optimization:

- Go to Details → Geometry Optimization

- Tick the "Optimize lattice" checkbox

- Run the calculation:

- Save the file with an appropriate name (e.g., "LiS_optimization")

- Select File → Run

- Update the structure in AMSinput when prompted [4]

Creating Amorphous Structure via Simulated Annealing

Amorphous structures are created using a molecular dynamics simulation with specific temperature cycling:

Set up molecular dynamics:

- Select Task → Molecular Dynamics

- Set the number of steps to 30000

- Click next to Task: Molecular Dynamics for detailed settings

Configure temperature profile:

- Click next to Thermostat for thermostat details

- Add a new Berendsen thermostat

- In Temperature(s), set:

300 300 1600 300 - In Duration(s), set:

5000 20000 5000 - Set damping constant to 100 fs [4]

Execute simulated annealing:

- Save file as "LiSsimulatedannealing"

- Run the calculation

- Update structure when completed

This protocol creates the following temperature profile:

- Steps 0-5000: Constant temperature at 300 K

- Steps 5000-25000: Linear heating from 300 K to 1600 K

- Steps 25000-30000: Rapid cooling from 1600 K to 300 K [4]

Production Simulation for Diffusion Analysis

Configure molecular dynamics:

- Select Task → Molecular Dynamics

- Set number of steps to 110000 (10000 equilibration + 100000 production)

- Set Sample frequency to 5 (records positions and velocities every 5 steps)

- Time step: 0.25 fs (default)

Set thermostat conditions:

- Thermostat Type: Berendsen

- Temperature: 1600 K

- Clear the Duration field

- Damping constant: 100 fs [4]

Run production simulation:

- Save as "LiSMD1600K"

- Execute calculation

- Monitor progress in AMSMovie and AMStail

Data Analysis Methodologies

Mean Squared Displacement (MSD) Approach

The MSD method is the recommended approach for calculating diffusion coefficients:

- Open the trajectory in AMSMovie

- Access MSD analysis:

- Select MD Properties → MSD

- In Steps, set 2000 - 22001 (exclude equilibration)

- Set Atoms to Li (select lithium atoms only)

- Set Max MSD Frame to 5000 (corresponding to 5000 × 1.25 fs = 6250 fs)

- Generate MSD: Click "Generate MSD" to calculate the mean squared displacement [4]

The diffusion coefficient is calculated from the slope of the MSD plot:

[ MSD(t) = \langle [\textbf{r}(0) - \textbf{r}(t)]^2 \rangle ]

[ D = \frac{\textrm{slope(MSD)}}{6} ]

The MSD should show a straight line, indicating normal diffusion behavior. If the MSD line is not straight, longer simulation times are needed to gather better statistics [4].

Velocity Autocorrelation Function (VACF) Method

The VACF approach provides an alternative method for diffusion coefficient calculation:

- Open trajectory in AMSMovie

- Access autocorrelation analysis:

- Select MD Properties → Autocorrelation function

- In Steps, set 2000 - 22001

- Select Property → Diffusion Coefficient (D)

- Set Atoms to Li

- Set Max ACF Step to 5000

- Generate ACF: Click "Generate ACF" to calculate the velocity autocorrelation function [4]

The diffusion coefficient is obtained through integration of the VACF:

[ D = \frac{1}{3} \int{t=0}^{t=t{max}} \langle \textbf{v}(0) \cdot \textbf{v}(t) \rangle \rm{d}t ]

The bottom plot shows the integral of the VACF divided by 3 (diffusion coefficient), which should converge to a horizontal line for sufficiently long times [4].

Quantitative Results and Method Comparison

Table 3: Diffusion Coefficient Results for Liâ‚€.â‚„S at 1600K

| Method | Diffusion Coefficient (m²/s) | Convergence Behavior | Computational Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| MSD | 3.09 × 10â»â¸ | Should be perfectly horizontal | Requires straight MSD line for validity |

| VACF | 3.02 × 10â»â¸ | Should converge for large times | Requires small sampling frequency |

| Agreement | Excellent (≈2% difference) | Both methods show proper convergence | MSD recommended for larger systems |

Temperature Extrapolation using Arrhenius Relationship

For practical applications, diffusion coefficients at lower temperatures can be estimated through Arrhenius extrapolation:

- Calculate D(T) at multiple temperatures: Perform production simulations at minimum four different temperatures (e.g., 600 K, 800 K, 1200 K, 1600 K)

- Construct Arrhenius plot: Plot ln(D(T)) against 1/T

- Extract activation parameters: [ D(T) = D0 \exp{(-Ea / k{B}T)} ] [ \ln{D(T)} = \ln{D0} - \frac{Ea}{k{B}}\cdot\frac{1}{T} ] Where Dâ‚€ is the pre-exponential factor and E_a is the activation energy [4]

This approach enables estimation of room-temperature diffusion coefficients that would otherwise require prohibitively long simulation times due to reduced atomic mobility.

Technical Considerations and Best Practices

Finite-Size Effects and System Preparation

A critical consideration in ReaxFF diffusion studies is the management of finite-size effects:

- System size dependence: Diffusion coefficients depend on supercell size unless the supercell is very large

- Extrapolation procedure: Perform simulations for progressively larger supercells and extrapolate to the "infinite supercell" limit

- Validation: Compare results from different system sizes to assess convergence [4]

Sampling and Statistical Accuracy

- Trajectory length: Ensure sufficient sampling time for meaningful statistics

- Equilibration exclusion: Exclude initial equilibration phase from analysis (e.g., first 2000 steps in the tutorial example)

- Convergence monitoring: Check that MSD and VACF plots show proper convergence behavior

- Multiple independent runs: Consider running multiple simulations with different initial random seeds for better statistics

Advanced Applications and Extensions

The ReaxFF methodology continues to evolve with several advanced capabilities:

- eReaxFF: Explicit treatment of electrons enabling simulation of redox reactions

- Acceleration techniques: Various methods for extending timescales, including collective variable-driven hyperdynamics

- Reactive Monte Carlo: Grand Canonical Monte Carlo (GCMC) for improved system construction

- Parameter optimization: Tools for refining force fields or building new ReaxFF parameter sets [5]

The protocols outlined in this application note for lithium-ion diffusion in sulfur cathodes can be adapted to study diffusion in various material systems, including other battery chemistries, polymer electrolytes, and catalytic systems.

Theoretical Basis of Diffusion Coefficients in Molecular Dynamics

The diffusion coefficient (D) is a critical transport property that quantifies the rate of particle movement through a material. In molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, calculating accurate diffusion coefficients is essential for researching and optimizing processes across numerous fields, including battery design, carbon sequestration, and drug development [6] [7]. MD simulations provide a robust computational framework that bridges microscopic particle motion with macroscopic transport properties, offering insights that are often challenging to obtain experimentally [6]. This article details the theoretical foundations, primary calculation methodologies, and practical protocols for determining diffusion coefficients, with a specific focus on applications within ReaxFF molecular dynamics simulations.

Theoretical Foundations

At the heart of diffusion coefficient calculations in MD lies the Einstein relation, which connects the random, microscopic motion of particles to a macroscopic diffusivity value [6]. This relation is operationalized through the calculation of the Mean Squared Displacement (MSD), defined as the average squared distance a particle travels over time:

[MSD(t) = \langle [\textbf{r}(0) - \textbf{r}(t)]^2 \rangle]

where (\textbf{r}(0)) and (\textbf{r}(t)) are the particle's position vectors at time zero and time (t), respectively, and the angle brackets denote an average over all particles and time origins. For a particle undergoing normal diffusion, the MSD increases linearly with time. The slope of this linear relationship is directly proportional to the self-diffusion coefficient (D), which, in three dimensions, is given by:

[D = \frac{\textrm{slope(MSD)}}{6}]

An alternative, mathematically equivalent approach involves the Velocity Autocorrelation Function (VACF). The VACF measures how a particle's velocity at one time is correlated with its velocity at a later time. The diffusion coefficient is obtained from the integral of the VACF:

[D = \frac{1}{3} \int{t=0}^{t=t{max}} \langle \textbf{v}(0) \cdot \textbf{v}(t) \rangle \rm{d}t]

Where (\textbf{v}(t)) is the velocity vector at time (t). The MSD method is generally recommended for its straightforward implementation and robustness, whereas the VACF method can provide additional dynamical insights but may require higher data sampling rates [4].

Calculation Methodologies: MSD vs. VACF

The two primary methods for calculating diffusion coefficients from MD trajectories each have distinct advantages and considerations, as summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Comparison of Methods for Calculating Diffusion Coefficients from MD Simulations

| Feature | Mean Squared Displacement (MSD) | Velocity Autocorrelation Function (VACF) |

|---|---|---|

| Theoretical Basis | Einstein relation [6] | Green-Kubo relation [6] |

| Recommended Use | Primary, recommended method [4] | Complementary method offering dynamical insights |

| Key Output | Plot of MSD vs. time | Plot of VACF, its integral, and power spectrum |

| Convergence | (D) is derived from the slope of the linear portion of the MSD curve. | (D) is derived from the plateau of the integrated VACF curve. |

| Sampling Requirement | Lower sampling frequency is acceptable, leading to smaller trajectory files [4] | Requires a high sampling frequency (small time steps between saved velocities) [4] |

| Computational Note | The slope must be taken from the diffusive regime, after the initial ballistic motion. | The integral should converge for large enough (t_{max}). |

Practical Protocols for ReaxFF-MD

This section provides a detailed step-by-step protocol for calculating the diffusion coefficient of Lithium ions in an amorphous Li(_0.4)S cathode material using ReaxFF, as based on a established tutorial [4].

System Preparation and Equilibration

- Structure Import and Construction: Begin by importing the crystal structure of the host material (e.g., a Sulfur crystal from a CIF file). Use the builder functionality in your MD software (e.g., AMSinput) to insert the diffusing species (e.g., 51 Li atoms) randomly into the structure. For more thermodynamically representative structures, consider using Grand Canonical Monte Carlo (GCMC) methods [4].

- Geometry Optimization: Relax the initial structure by performing a geometry optimization with lattice relaxation. This crucial step minimizes high-energy atomic clashes and finds a stable starting configuration. Use an appropriate force field (e.g.,

LiS.fffor a Li-S system) [4]. - Simulated Annealing for Amorphous Systems: To generate amorphous structures, perform a simulated annealing MD simulation.

- Temperature Profile:

- Step 0-5,000: Hold at 300 K.

- Step 5,000-25,000: Ramp temperature from 300 K to 1600 K.

- Step 25,000-30,000: Rapidly cool down from 1600 K to 300 K.

- Thermostat: Use a Berendsen thermostat with a damping constant of 100 fs [4].

- Temperature Profile:

- Final Optimization: After annealing, perform a second geometry optimization, including lattice relaxation, to obtain the final equilibrated amorphous structure for production MD runs.

Production MD Simulation

- Simulation Setup: Configure an MD simulation at the target temperature (e.g., 1600 K for high-temperature studies).

- Task: Molecular Dynamics.

- Total Steps: 110,000 (including 10,000 steps for equilibration).

- Thermostat: Berendsen thermostat at the target temperature with a damping constant of 100 fs.

- Sample Frequency: Set to 5 (saving atomic positions and velocities every 5 steps). With a typical time step of 0.25 fs, this yields a trajectory output every 1.25 fs [4].

- Execution: Run the simulation and monitor properties like temperature for stability.

Diffusion Coefficient Analysis

Via MSD (Recommended):

- Load the production trajectory into an analysis tool (e.g., AMSmovie).

- Select the relevant atoms (e.g., Li).

- Calculate the MSD, setting the analysis to start after the equilibration period (e.g., from step 2,000).

- Set a "Max MSD Frame" (e.g., 5,000) to analyze a sufficiently long time window (6,250 fs in this case).

- The software will generate an MSD plot and a corresponding plot for (D), calculated as the slope of the MSD divided by 6. A constant (D) value indicates convergence [4].

Via VACF:

- In the analysis tool, select the "Autocorrelation function" for the production phase of the trajectory.

- Set the property to "Diffusion Coefficient (D)" and select the relevant atoms.

- The tool will plot the VACF, its power spectrum, and the integral of the VACF divided by 3 (which is (D)). The value of (D) is taken from the plateau of this integral for large times [4].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the complete protocol from system setup to analysis.

Diagram 1: Complete workflow for calculating diffusion coefficients in battery cathode materials.

Essential Considerations and Best Practices

Addressing Computational Artifacts

Obtaining physically meaningful diffusion coefficients requires careful consideration of several computational factors.

- Finite-Size Effects: The calculated diffusion coefficient is sensitive to the size of the simulation cell. To mitigate this, perform simulations for progressively larger supercells and extrapolate the calculated (D) values to the "infinite supercell" limit [4].

- Ballistic vs. Diffusive Regime: At very short timescales, particle motion is ballistic (MSD (\propto t^2)), not diffusive. The linear slope used to calculate (D) must be taken from the subsequent diffusive regime (MSD (\propto t)). Running a sufficiently long simulation is necessary to capture this [6].

- Force Field Selection and Parameterization: The choice of force field is critical. Standard force fields may not accurately capture the solid nature and mass transport properties of all materials. For instance, a reparameterization of ReaxFF for Lithium Fluoride (LiF) was necessary to correct the diffusivity of lithium ions by two orders of magnitude at room temperature, making the prediction realistic [8]. Always validate your force field for the specific system and property of interest.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for ReaxFF-MD Diffusion Studies

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| ReaxFF Force Field | A reactive force field using bond-order and charge equilibration to model chemical reactions. | Simulating electrolyte decomposition and Li-ion diffusion in batteries [8]. |

| AMSinput / AMSmovie | Software for setting up MD simulations and analyzing trajectories. | Importing structures, building systems, and calculating MSD/VACF [4]. |

| Python Libraries (ASE, PyMatgen) | Libraries for automating and orchestrating atomistic simulations. | Managing simulation workflows and facilitating force field reparameterization [8]. |

| Berendsen Thermostat | An algorithm to control the simulation temperature by weakly coupling the system to a heat bath. | Maintaining temperature during equilibration and production MD runs [4]. |

Extrapolation to Experimental Conditions

Directly calculating (D) at low temperatures (e.g., room temperature) can be computationally prohibitive due to slow dynamics. A common strategy is to use the Arrhenius equation to extrapolate from higher-temperature simulations:

[D(T) = D0 \exp{(-Ea / k_{B}T)}]

where (D0) is the pre-exponential factor, (Ea) is the activation energy, (kB) is the Boltzmann constant, and (T) is the temperature. By calculating (D) for at least four different elevated temperatures (e.g., 600 K, 800 K, 1200 K, 1600 K) and plotting (\ln{(D(T))}) against (1/T), one can determine (Ea) and (D_0) from the slope and intercept, allowing for the estimation of (D) at lower, experimentally relevant temperatures [4]. The diagram below illustrates this analytical workflow.

Diagram 2: Workflow for extrapolating diffusion coefficients using Arrhenius behavior.

Molecular dynamics simulations, particularly using reactive force fields like ReaxFF, provide a powerful tool for determining diffusion coefficients atomistically. The MSD method offers a robust and recommended pathway for calculating (D), while the VACF method serves as a valuable complementary approach. The accuracy of these calculations hinges on careful system preparation, including equilibration and annealing, and a thorough understanding of computational limitations such as finite-size effects and force field applicability. By adhering to the detailed protocols outlined herein and leveraging strategies like Arrhenius extrapolation, researchers can reliably simulate and predict diffusion coefficients, thereby enabling advances in material design and optimization for energy storage and other critical technologies.

Application Notes

The ReaxFF reactive force-field is a powerful computational tool for modeling complex, dynamic chemical processes across diverse material systems, bridging the gap between quantum mechanical accuracy and classical molecular dynamics scale. By employing a bond-order formalism, ReaxFF enables the simulation of reactive events, making it uniquely suited for investigating phenomena in battery materials, combustion chemistry, and biomolecular transport where bond formation and breaking are central [2]. Its functional form describes the system energy through a combination of bond-order-dependent and bond-order-independent terms, allowing for the simulation of reactive interfaces between solid, liquid, and gas phases [2].

Battery Materials

In lithium-ion battery (LIB) research, ReaxFF is instrumental in studying the formation, composition, and properties of the solid-electrolyte interphase (SEI), a critical passivation layer that forms on anode surfaces. The SEI governs battery performance, cycle life, and safety, but its reactive and multiscale nature makes it difficult to study experimentally [8]. ReaxFF molecular dynamics (MD) simulations have provided insights into the layering of organic and inorganic SEI components resulting from electrolyte decomposition on lithium metal and graphite anodes [8]. A key focus of recent development has been enhancing force fields for specific SEI components like Lithium Fluoride (LiF), which is known to improve cycling stability due to its high ion transport and electronic insulation properties [8]. Furthermore, ReaxFF can be used to compute lithium ion diffusion coefficients within electrode materials, a critical parameter for battery performance, typically through analysis of the mean squared displacement (MSD) from MD trajectories [4].

Combustion Systems

ReaxFF enables the detailed study of complex reaction pathways and kinetics in combustion processes at the atomic scale. It has been successfully applied to simulate the combustion of hydrocarbons, such as methane, revealing the consumption of reactants and the production of species like Hâ‚‚O and COâ‚‚ [9]. The force field's transferability across phases allows it to model the interaction of gaseous oxidizers with solid or liquid fuels. Recent studies have extended this capability to more complex systems, such as the hydrothermal gasification of polystyrene microplastics, elucidating the crucial roles of temperature and water content in syngas production and reaction mechanisms [10]. Similarly, ReaxFF MD simulations have been used to investigate the sintering and oxidation characteristics of aluminum nanoparticles (ANPs), providing molecular-level understanding of how hydrocarbon coatings can modulate reactivity and improve combustion performance [11].

Biomolecular Transport

Modeling biomolecular transport presents a significant challenge for reactive force fields. While ReaxFF's formal framework could, in principle, be applied to complex biological molecules, the available literature and parameterizations are predominantly focused on materials science, battery research, and combustion chemistry. The primary challenge lies in the lack of specific, optimized force field parameters for key biological elements and complex molecular interactions. Current research, as identified, does not provide specific application notes for this sub-topic, indicating a potential area for future ReaxFF development.

Table 1: Key Application Areas of ReaxFF MD Simulations

| Application Area | System of Interest | ReaxFF's Role | Key Insights |

|---|---|---|---|

| Battery Materials | Li-ion batteries (Anodes, SEI) | Models electrolyte reduction and SEI formation & properties [8]. | Revealed layered SEI structure; LiF-rich SEI improves stability [8]. |

| Combustion Systems | Hydrocarbons (e.g., Methane), Energetic materials (e.g., ANPs) | Uncovers detailed reaction pathways and kinetics under extreme conditions [9] [10] [11]. | Identified reaction products (Hâ‚‚O, COâ‚‚); showed coating controls ANP reactivity [9] [11]. |

| Biomolecular Transport | Not specified in search results | Potential to model reactive processes in biomolecules. | Lacks specific parameterization and application data in current literature. |

Experimental Protocols

The following protocols provide detailed methodologies for setting up and analyzing ReaxFF MD simulations for computing diffusion coefficients in battery materials and for studying combustion reactions.

Protocol 1: Calculating Diffusion Coefficients in Battery Electrode Materials

This protocol outlines the procedure for computing the diffusion coefficient (D) of lithium ions in a model cathode material (e.g., Li~0.4~S) using ReaxFF MD, based on a documented tutorial [4].

Workflow Overview:

Materials and Setup:

- Software: AMS software suite (including AMSinput, AMSmovie, AMSjobs) [4].

- Force Field: An appropriate ReaxFF parameter file (e.g.,

LiS.fffor lithium-sulfur systems) [4]. - Initial Structure: A crystallographic information file (.cif) for the base cathode material.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

System Preparation:

- Import the cathode material's CIF file into AMSinput.

- Use the Builder tool to insert the required number of Li atoms (e.g., 51 Li atoms for Li~0.4~S) randomly into the structure using the SMILES code

[Li][4]. - Set the calculation Task to Geometry Optimization.

- Select the relevant force field (e.g.,

LiS.ff). - In the Details → Geometry Optimization panel, tick Optimize lattice.

- Run the calculation and update the AMSinput structure upon completion [4].

Creating an Amorphous Structure (Simulated Annealing):

- Change the Task to Molecular Dynamics.

- Set the number of steps (e.g., 30,000) and the Thermostat to Berendsen.

- Configure a temperature profile for annealing:

- Temperature(s):

300 300 1600 300K - Duration(s):

5000 20000 5000steps

- Temperature(s):

- Run the simulation and update the structure upon completion [4].

- Perform a final Geometry Optimization with Optimize lattice checked to relax the annealed structure [4].

Production MD Simulation:

- Set the Task to Molecular Dynamics.

- Set the Number of steps (e.g., 110,000 for equilibration + production).

- Set the Sample frequency (e.g., 5) to write trajectory data regularly.

- Configure the Thermostat (e.g., Berendsen) for a constant target temperature (e.g., 1600 K).

- Run the production MD simulation [4].

Data Analysis - Diffusion Coefficient:

- Via Mean Squared Displacement (MSD - Recommended):

- Open the trajectory in AMSmovie.

- Select MD Properties → MSD.

- Set the Atoms to

Li. - Adjust the Steps and Max MSD Frame to select a stable, linear region of the MSD plot.

- Click Generate MSD. The software will perform a linear fit.

- Calculate ( D = \frac{\text{slope(MSD)}}{6} ) [4].

- Via Velocity Autocorrelation Function (VACF):

- In AMSmovie, select MD Properties → Autocorrelation function.

- Set Property to

Diffusion Coefficient (D)and Atoms toLi. - Click Generate ACF. The value of D is obtained from the plateau in the bottom plot (integral of VACF divided by 3) [4].

- Via Mean Squared Displacement (MSD - Recommended):

Troubleshooting and Validation:

- Finite-Size Effects: The calculated diffusion coefficient is sensitive to supercell size. For accurate results, perform simulations for progressively larger supercells and extrapolate to the "infinite supercell" limit [4].

- Statistical Accuracy: Ensure the MSD plot shows a clear linear regime. A curved or noisy MSD indicates the need for a longer simulation to gather better statistics [4].

- Convergence Check: The diffusion coefficient (D) curve derived from the VACF integral should become horizontal (converge) for large times [4].

Protocol 2: Simulating a Combustion Reaction

This protocol describes how to set up and analyze a ReaxFF MD simulation for a gas-phase combustion reaction, using a methane (CHâ‚„) and oxygen (Oâ‚‚) mixture as an example [9].

Workflow Overview:

Materials and Setup:

- Software: AMS software suite [9].

- Force Field: A force field parameterized for combustion (e.g.,

CHO.fffor hydrocarbon oxidation) [9]. - System: A mixture of fuel and oxidizer (e.g., CHâ‚„ and Oâ‚‚).

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Build the Reactant Mixture:

- In AMSinput, set Periodicity to

Bulk. - Open the Builder (Edit → Builder).

- Set the Density (e.g., 1.163 g/cm³ for a high-density, fast simulation).

- Set the Approximate number of atoms (e.g., 500).

- Tick Use mole fractions.

- Add rows for the fuel and oxidizer. Specify them using SMILES codes or searches (e.g.,

CHâ‚„andOâ‚‚) and set their mole fractions (e.g., a 1:2.5 ratio for CHâ‚„:Oâ‚‚). - Click Generate Molecules and then Close [9].

- In AMSinput, set Periodicity to

Configure the MD Simulation:

- Select the appropriate Force Field (e.g.,

CHO.ff). - Set the Task to Molecular Dynamics.

- In the MD settings, set the Number of steps (e.g., 30,000).

- Configure the Thermostat:

- Select NHC (Nose-Hoover Chain) for better sampling.

- Set a high Temperature (e.g., 3500 K to accelerate reactions).

- Set a Damping constant (e.g., 100 fs) [9].

- Select the appropriate Force Field (e.g.,

Run and Monitor the Simulation:

- Run the calculation. The simulation can be monitored in real-time.

- Open AMSmovie (SCM → Movie) to visualize the trajectory as it runs.

- Use MD Properties → Temperature and MD Properties → Conserved Energy to monitor thermodynamic stability [9].

Analyze Reaction Products:

- In AMSmovie, use MD Properties → Molecules… to open the molecule analysis dialog.

- This dialog lists all molecule types detected during the simulation. To refresh the list for a running job, close and reopen the dialog.

- Select the checkboxes for key reactants and products (e.g., CHâ‚„, Oâ‚‚, Hâ‚‚O, COâ‚‚) to plot their counts over time.

- Use the visualization tools in conjunction with the molecule plot: click on a data point in the plot to jump to that frame in the trajectory and visually inspect the corresponding molecular species [9].

Troubleshooting and Validation:

- Lack of Reaction: If no reactions occur within the simulated timeframe, consider increasing the temperature (though this reduces physical realism) or the simulation length.

- Identifying Products: The automatic molecule identification may sometimes group atoms incorrectly. Cross-referencing with the visualizer is crucial for validation.

The Scientist's Toolkit

This section details key resources and materials required for conducting ReaxFF MD simulations in the discussed application areas.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for ReaxFF Simulations

| Item Name | Function / Description | Example / Specification |

|---|---|---|

| ReaxFF Force Field Parameter File | Contains all empirical parameters defining atomic interactions for a specific set of elements. It is the core of the simulation. | CHO.ff (for hydrocarbon oxidation) [9], LiS.ff (for lithium-sulfur systems) [4]. |

| Initial Coordinate File | Defines the starting atomic positions and, for crystalline materials, the unit cell. | Crystallographic Information File (.cif) [4], XYZ file [4], or PDB file. |

| Molecular Builder Tool | Software component for constructing complex molecular systems, inserting species, and creating mixtures. | AMSinput Builder [4] [9]. |

| Trajectory Analysis & Visualization Software | Essential for visualizing simulation progress, analyzing results, and calculating properties like MSD, VACF, and molecule counts. | AMSmovie [4] [9]. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | ReaxFF MD simulations are computationally intensive and typically require parallel computing resources to run in a reasonable time. | A cluster with multiple CPU cores and sufficient RAM [9]. |

| Dotmp | Dotmp, CAS:91987-74-5, MF:C12H32N4O12P4, MW:548.30 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Hexanoic anhydride | Hexanoic anhydride, CAS:2051-49-2, MF:C12H22O3, MW:214.30 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The Reactive Force-Field (ReaxFF) interatomic potential is a powerful computational tool for exploring, developing and optimizing material properties, bridging the gap between highly accurate but computationally expensive quantum mechanical (QM) methods and efficient but non-reactive classical potentials [2]. ReaxFF achieves this by employing a bond-order formalism that allows for dynamic bond formation and breaking, enabling the simulation of chemical reactions without the prohibitive computational cost of QM methods [2]. This capability makes ReaxFF particularly valuable for studying complex reactive processes in materials science, including the diffusion of species through various phases, which is a central theme in molecular dynamics diffusion research [2] [4].

The fundamental strength of ReaxFF lies in its transferability across different phases—an oxygen atom is treated with the same mathematical formalism whether it is in the gas phase as O₂, in the liquid phase within an H₂O molecule, or incorporated in a solid oxide [2]. This transferability, coupled with its ability to handle reactive events, makes it ideally suited for investigating diffusion phenomena in complex, multi-phase systems where chemical reactions and mass transport are interconnected.

The Bond-Order Formalism

At the heart of the ReaxFF method is its bond-order formalism, which implicitly describes chemical bonding without expensive QM calculations [2]. Unlike traditional force fields that require predefined connectivity, ReaxFF calculates bond order (BO) directly and continuously from interatomic distances using an empirical formula:

[BO{ij} = BO{ij}^\sigma + BO{ij}^\pi + BO{ij}^{\pi\pi} = \exp\left[p{bo1}\left(\frac{r{ij}}{r0^\sigma}\right)^{p{bo2}}\right] + \exp\left[p{bo1}\left(\frac{r{ij}}{r0^\pi}\right)^{p{bo4}}\right] + \exp\left[p{bo1}\left(\frac{r{ij}}{r0^{\pi\pi}}\right)^{p{bo6}}\right]]

In this formulation, BOᵢⱼ represents the total bond order between atoms i and j, which is the sum of σ, π, and ππ components [2]. The rᵢⱼ term is the interatomic distance, r₀ terms represent equilibrium bond lengths for different bond types, and pbo terms are empirical parameters. This continuous, distance-dependent calculation of bond order allows ReaxFF to naturally handle bond formation, dissociation, and transitions between single, double, and triple bonds without introducing discontinuities in the potential energy surface [2].

This approach provides a differentiable potential energy surface essential for calculating interatomic forces during molecular dynamics simulations [2]. The bond order is typically calculated within a covalent range of approximately 5 Ã…ngstroms, which is sufficient to capture even the weakest covalent interactions for most elements [2].

Comprehensive Energy Contributions

The ReaxFF potential energy is described as a sum of various energy contributions that collectively determine the system's behavior [2]:

[E{system} = E{bond} + E{over} + E{angle} + E{tors} + E{vdWaals} + E{Coulomb} + E{Specific}]

The following table summarizes these key energy terms and their physical significance in the ReaxFF potential:

Table 1: Energy Contributions in the ReaxFF Potential

| Energy Term | Symbol | Description | Physical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bond Energy | Ebond | Energy associated with bond formation/breaking | Describes covalent interactions through bond-order formalism |

| Overcoordination Penalty | Eover | Energy penalty preventing atom overcoordination | Based on atomic valence rules; prevents unrealistic bonding |

| Angle Strain | Eangle | Three-body valence angle strain energy | Maintains proper molecular geometry |

| Torsional Strain | Etors | Four-body torsional angle strain energy | Governs rotational barriers around bonds |

| van der Waals | EvdWaals | Dispersive interactions | Calculated between all atom pairs regardless of connectivity |

| Coulomb | ECoulomb | Electrostatic interactions | Calculated between all atoms using charge equilibration |

| Specific Terms | ESpecific | System-specific corrections | Includes lone-pair, conjugation, hydrogen binding corrections |

These energy terms can be conceptually divided into bond-order-dependent contributions (Ebond, Eover, Eangle, Etors) and bond-order-independent contributions (EvdWaals, ECoulomb) [2]. The non-bonded interactions, EvdWaals and ECoulomb, are calculated between all atoms irrespective of connectivity, which is crucial for properly describing intermolecular interactions in diffusion processes [2].

The ESpecific term represents system-specific corrections that are not generally included unless required to capture properties particular to the system of interest, such as lone-pair interactions, conjugation effects, hydrogen binding, and Câ‚‚ corrections [2].

Computational Protocols for Diffusion Studies

The calculation of diffusion coefficients using ReaxFF molecular dynamics involves several well-defined steps, from system preparation to production simulations and analysis. The following workflow outlines the key stages in a typical diffusion study:

System Preparation and Equilibration Protocol

Structure Import and Initial Optimization:

- Begin by importing the initial crystal structure, typically from a CIF file [4].

- Perform geometry optimization including lattice relaxation using an appropriate ReaxFF force field [4].

- For battery materials like LixS, use the Builder functionality to insert mobile ions (e.g., Li-atoms) randomly into the structure [4].

- Optimize the structure again with lattice relaxation to accommodate the inserted species [4].

Creating Amorphous Systems by Simulated Annealing:

- For materials that require modeling in amorphous states, implement a simulated annealing protocol [4]:

- Perform Molecular Dynamics with the following temperature profile:

- From start until step 5000: Maintain constant temperature at 300 K

- From step 5000 to step 25000: Heat linearly from 300 K to 1600 K

- From step 25000 to step 30000: Cool rapidly from 1600 K to 300 K [4]

- Use a Berendsen thermostat with a damping constant of 100 fs [4]

- Follow annealing with final geometry optimization including lattice relaxation [4]

- Perform Molecular Dynamics with the following temperature profile:

Production Simulation and Analysis Protocol

Production MD Simulation Setup:

- Configure Molecular Dynamics for production run:

- The time between trajectory points will be: samplefrequency × timestep = 5 × 0.25 fs = 1.25 fs [4]

Diffusion Coefficient Calculation Methods:

Two primary methods are used to compute diffusion coefficients from MD trajectories:

Method 1: Mean Squared Displacement (MSD) - Recommended

- Calculate MSD using the formula: [MSD(t) = \langle [\textbf{r}(0) - \textbf{r}(t)]^2 \rangle]

- Compute diffusion coefficient as: [D = \frac{\textrm{slope(MSD)}}{6}]

- In practice:

- Set analysis for appropriate steps (e.g., 2000-22001)

- Select diffusing atoms (e.g., Li)

- Set maximum MSD frame to 5000 (corresponding to 5000×1.25 fs = 6250 fs) [4]

- The diffusion coefficient is determined from the linear region of the MSD vs. time plot [4]

Method 2: Velocity Autocorrelation Function (VACF)

- Calculate VACF and integrate to obtain diffusion coefficient: [D = \frac{1}{3} \int{t=0}^{t=t{max}} \langle \textbf{v}(0) \cdot \textbf{v}(t) \rangle \rm{d}t]

- This method requires higher sampling frequency (smaller interval between saved frames) [4]

Extrapolation to Lower Temperatures:

- Calculate diffusion coefficients at multiple elevated temperatures (e.g., 600 K, 800 K, 1200 K, 1600 K) [4]

- Use Arrhenius equation for extrapolation: [D(T) = D0 \exp{(-Ea / k{B}T)}] [\ln{D(T)} = \ln{D0} - \frac{Ea}{k{B}}\cdot\frac{1}{T}]

- Create Arrhenius plot of ln(D(T)) against 1/T to determine activation energy (Ea) and pre-exponential factor (D0) [4]

- Extrapolate to predict diffusion coefficients at lower temperatures inaccessible to direct MD simulation [4]

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Successful implementation of ReaxFF diffusion studies requires careful selection of force fields and computational tools. The following table details key "research reagent solutions" essential for these simulations:

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for ReaxFF Diffusion Studies

| Tool/Reagent | Type | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| CHO.ff | Force Field | Describes hydrocarbon oxidation | Part of combustion branch; parameters from Chenoweth et al. [12] |

| CuCl-Hâ‚‚O.ff | Force Field | Models aqueous chloride/copper chloride | Part of water branch; for aqueous systems [12] |

| FeOCHCl.ff | Force Field | Simulates iron-oxyhydroxide systems | Contains Fe/O/C/H/Cl parameters; water branch [12] |

| LiS.ff | Force Field | Specific for lithium-sulfur systems | Used in battery material diffusion studies [4] |

| AMSinput | Software | Graphical interface for simulation setup | Provides Builder functionality for system construction [4] |

| LAMMPS | Software | Open-source MD engine | Supports ReaxFF implementation [2] |

| PuReMD | Software | Purdue Reactive MD code | Optimized for ReaxFF simulations [2] |

| AMSmovie | Analysis Tool | Visualization and analysis of MD trajectories | Calculates MSD, VACF, diffusion coefficients [4] |

Critical Implementation Considerations

Force Field Selection: ReaxFF parameters are typically divided into two major branches: the combustion branch and the aqueous (water) branch [12]. The primary difference lies in the O/H parameters, where the combustion branch focuses on accurately describing water as a gas-phase molecule, while the water branch targets aqueous chemistry [12]. Selection should be based on the specific system and phase conditions being studied.

Finite-Size Effects:

- Diffusion coefficients calculated from MD simulations exhibit finite-size effects dependent on supercell size [4]

- For accurate results, perform simulations with progressively larger supercells

- Extrapolate calculated diffusion coefficients to the "infinite supercell" limit [4]

Convergence Criteria:

- For MSD analysis: The slope of MSD vs. time should be linear in the diffusion regime [4]

- For VACF analysis: The integral of VACF divided by 3 should converge to a constant value [4]

- If these criteria are not met, longer simulations are required to gather better statistics [4]

Advanced Applications and Recent Developments

Recent advancements in ReaxFF have expanded its applications to complex bimetallic systems relevant to catalysis and energy materials. For instance, parameters have been developed for MnMOx (M = Cu, Fe, Ni) bimetallic transition-metal oxides, enabling the study of toluene adsorption and degradation on catalyst surfaces [13]. The development process for these force fields involves:

- Training against DFT data and experimental results

- Geometry optimization using multiple temperature regimes (1 K, 300 K, 500 K)

- Validation through comparison of ReaxFF-obtained geometries with crystallographic data [13]

While ReaxFF has proven successful in numerous applications, recent developments in neural network potentials (NNPs) like EMFF-2025 offer promising alternatives that may achieve higher accuracy while maintaining computational efficiency for C, H, N, O-based systems [14]. However, ReaxFF remains a robust and widely-used method for simulating reactive processes, particularly for complex multi-element systems and diffusion studies where chemical reactivity and mass transport are coupled.

Within the broader context of ReaxFF molecular dynamics (MD) tutorial research, particularly for calculating material properties like diffusion coefficients in battery materials, a robust system preparation workflow is a critical first step [4]. The accuracy of subsequent MD simulations hinges on the quality of the initial structural model and its careful relaxation to a stable, low-energy configuration. This protocol details the comprehensive procedure for preparing an atomistic system, using a lithiated sulfur cathode (Li~0.4~S) as a representative example, from the initial import of a crystal structure to the final relaxed structure ready for production MD simulations [4]. The methodology is adapted from established ReaxFF research on lithiated sulfur cathode materials [4] [15].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Software

The following table catalogues the key computational "reagents" and tools required to execute the system preparation workflow.

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents and Software Solutions

| Item | Function in the Workflow | Specific Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| CIF File | Provides the initial, experimentally determined crystal structure of the host material. | Alpha-sulfur (S~8~) structure from a crystallographic database [4] [15]. |

| ReaxFF Force Field | An empirical potential that describes interatomic interactions, enabling modeling of bond breaking and formation. | LiS.ff parameter set, trained for lithium-sulfur systems [4] [15]. |

| MD Software Package | The simulation engine that performs energy calculations, geometry optimization, and molecular dynamics. | Amsterdam Modeling Suite (AMS) with ReaxFF module [4] [5]; other options include LAMMPS [2]. |

| Builder/Visualization Tool | Used for manipulating atomic structures (e.g., inserting atoms, building supercells) and visualizing results. | AMSinput builder [4]; OVITO for trajectory analysis [16]. |

| Bimoclomol | Bimoclomol | Bimoclomol is a heat shock protein co-inducer that activates HSF1 for research on neuroprotection, cytoprotection, and lysosomal function. For Research Use Only. Not for human use. |

| Iliparcil | Iliparcil, CAS:137214-72-3, MF:C16H18O6S, MW:338.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The entire system preparation process, from initial CIF import to a finalized structure, can be visualized as a sequential workflow. The following diagram outlines the key stages and decision points.

Diagram 1: The overall system preparation workflow for ReaxFF simulations.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Phase 1: Initial Structure Import and System Generation

Objective: To acquire a starting crystal structure and generate the desired chemical system, such as Li~x~S.

Importing the CIF File:

Generating the Li~0.4~S System:

- Access the builder functionality (

Edit → Builder) [4]. - In the builder menu, select to use a specific number of molecules.

- In the

SMILES or xyz-filefield, enter[Li]to represent a single lithium atom. - Set the number of molecules (

N mols) to the required quantity (e.g., 51 Li atoms for a specific S structure) and clickGenerate Molecules[4]. The Li atoms will be randomly inserted into the sulfur structure. - Alternative Advanced Method: For a more thermodynamically realistic distribution, Grand Canonical Monte Carlo (GCMC) can be used instead of random insertion to introduce lithium atoms [4] [15].

- Access the builder functionality (

Phase 2: Structure Relaxation and Equilibration

Objective: To relax the generated system's geometry and lattice, relieving any steric clashes or high-energy configurations introduced during the building process.

- Initial Geometry and Lattice Optimization:

- In the main panel of your input utility, set the

TasktoGeometry Optimization[4]. - Select the appropriate ReaxFF force field (e.g.,

LiS.ff) [4]. - Navigate to the

Details → Geometry Optimizationpanel and enable theOptimize latticecheckbox. This allows the simulation cell's size and shape to change during minimization [4]. - Save and run the calculation. Upon completion, update the structure in the input utility with the optimized coordinates [4].

- In the main panel of your input utility, set the

Phase 3: Creating Amorphous Structures (Optional)

Objective: To generate an amorphous phase of the material through a simulated annealing process, which may be more representative of certain experimental conditions.

Setting Up Simulated Annealing:

- Change the

TasktoMolecular Dynamics[4]. - In the MD details, set the number of steps (e.g., 30,000 for a short demonstration) [4].

- Configure the temperature profile (thermostat) to achieve annealing [4]:

- Add a Berendsen thermostat.

- Set

Temperature(s)to300 300 1600 300(in Kelvin). - Set

Duration(s)for these regimes to5000 20000 5000(in steps). - This profile holds at 300 K, ramps to 1600 K, then rapidly quenches back to 300 K.

- Run the simulation and update the input structure with the final coordinates from the trajectory [4].

- Change the

Relaxing the Amorphous System:

- Perform a final

Geometry Optimization(withOptimize latticeenabled) on the annealed structure to relax it into a low-energy amorphous configuration [4].

- Perform a final

Quantitative Parameters for Simulation Setup

The tables below summarize critical numerical parameters for the key simulation steps in this workflow.

Table 2: Molecular Dynamics Parameters for Simulated Annealing

| Parameter | Value | Purpose / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Total Steps | 30,000 [4] | Defines the total simulation length. |

| Temperature Regime | 300 K → 1600 K → 300 K [4] | Heats the crystal to induce disorder, then rapidly cools to "freeze" in the amorphous state. |

| Damping Constant | 100 fs [4] | Controls the strength of coupling to the thermostat. |

Table 3: Energy Minimization Settings

| Parameter | Setting | Purpose / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Task | Geometry Optimization [4] | To find the nearest local energy minimum. |

| Lattice Optimization | Enabled [4] | Crucial for relieving internal pressure and allowing volume changes upon lithiation. |

| Force Field | System-specific (e.g., LiS.ff) [4] |

Must be parameterized for all elements and interactions in the system. |

This application note has provided a detailed, step-by-step protocol for preparing complex material systems for ReaxFF molecular dynamics studies. By meticulously following the stages of CIF import, system generation, structure relaxation, and optional amorphization, researchers can create robust and reliable initial conditions. This rigorous approach to system preparation lays the essential groundwork for obtaining physically meaningful results in subsequent analyses, such as the calculation of ion diffusion coefficients in energy storage materials [4]. The principles outlined here, while demonstrated for a Li-S battery material, are broadly transferable to other classes of materials investigated with reactive force fields.

Choosing Appropriate Force Fields for Your Chemical System

In atomistic simulations, a force field is a set of parameters and equations used to compute forces between atoms and molecules, enabling the prediction of material behavior and properties. The Reactive Force Field (ReaxFF) method represents a significant advancement in molecular simulation techniques, bridging the gap between highly accurate but computationally expensive quantum mechanics (QM) methods and efficient but non-reactive classical force fields. Developed by Adri van Duin and colleagues, ReaxFF has become a powerful computational tool for exploring, developing, and optimizing material properties across diverse research domains [2] [17].

Unlike classical force fields that rely on predefined connectivity between atoms, ReaxFF employs a bond-order formalism that dynamically describes chemical bonding without expensive QM calculations. This innovative approach allows ReaxFF to simulate reactive events—the making and breaking of chemical bonds—during molecular dynamics simulations, while maintaining computational efficiency for large-scale systems [2]. The method has demonstrated remarkable transferability across the periodic table, with parameters available for elements ranging from hydrocarbons to transition metals and complex material systems.

The total energy in ReaxFF is partitioned into several components that collectively describe the complex interactions within chemical systems:

[ E{\text{system}} = E{\text{bond}} + E{\text{over}} + E{\text{angle}} + E{\text{tors}} + E{\text{vdWaals}} + E{\text{Coulomb}} + E{\text{Specific}} ]

Where (E{\text{bond}}) represents bond energy, (E{\text{over}}) is an energy penalty for over-coordination, (E{\text{angle}}) and (E{\text{tors}}) describe angle and torsion strain, (E{\text{vdWaals}}) and (E{\text{Coulomb}}) account for non-bonded interactions, and (E_{\text{Specific}}) includes system-specific terms such as lone-pair energies and conjugation effects [2]. This comprehensive energy description enables ReaxFF to accurately model both covalent and electrostatic interactions for a diverse range of materials, making it particularly valuable for studying complex processes at interfaces between solid, liquid, and gas phases.

Key Considerations for Force Field Selection

Selecting an appropriate force field is critical for obtaining reliable simulation results in computational chemistry and materials science. The choice depends on multiple factors, including the chemical composition of your system, the processes you wish to study, and the required balance between computational efficiency and accuracy. For ReaxFF applications, several crucial considerations must guide your selection process to ensure meaningful and transferable results.

Elemental Composition and Compatibility

The most fundamental consideration in force field selection is ensuring coverage of all elements in your chemical system. ReaxFF parameters are typically developed for specific element sets, and using a force field that doesn't include all relevant elements can produce unrealistic results. Currently, two major branches of ReaxFF parameter sets exist: the combustion branch and the aqueous branch. The primary difference between these branches lies in their O/H parameters, with the combustion branch optimized for gas-phase water molecules and the aqueous branch targeted at aqueous chemistry and solution-phase systems [12]. This distinction is crucial when studying processes involving water or hydration.

Table 1: ReaxFF Branches and Their Applications

| Branch | Focus Area | Key Characteristics | Example Force Fields |

|---|---|---|---|

| Combustion | Gas-phase reactions, hydrocarbons, high-energy materials | Optimized for water as gas-phase molecule | CHO.ff, HE.ff, HCONSB.ff |

| Aqueous | Solution chemistry, biological interfaces, electrochemistry | Targeted at aqueous chemistry and hydration | AuCSOH.ff, CuCl-H2O.ff, FeOCHCl.ff |

Transferability and System-Specific Optimization

While ReaxFF offers broad transferability across different phases and chemical environments, its parameters are typically trained against specific training sets relevant to particular applications. This specialization means that a force field performing excellently in one domain may produce unsatisfactory results in another. For instance, the ReaxFF for H/C/O compounds developed for combustion chemistry may be inaccurate in describing the mechanical properties of graphite and diamond [18]. Therefore, it's essential to verify that your chosen force field has been validated for properties and systems similar to your research focus.

Recent advances in parameter optimization frameworks offer promising avenues for improving force field accuracy and transferability. Methods combining simulated annealing (SA) and particle swarm optimization (PSO) algorithms with concentrated attention mechanisms (CAM) have demonstrated faster and more accurate parameter optimization compared to traditional metaheuristic methods [18]. These approaches can be particularly valuable when existing force fields require refinement for specific systems or when developing entirely new parameter sets.

Research Context and Targeted Properties

Different research domains prioritize distinct material properties and processes, necessitating specialized force field parameterizations. For battery research, accurate description of ion diffusion and interfacial reactions is paramount, while combustion chemistry requires precise reaction barriers and bond dissociation energies. Biomaterials applications often demand accurate treatment of organic-inorganic interfaces and solvation effects. Understanding which properties were prioritized during a force field's development will guide appropriate selection.

Available ReaxFF Force Fields and Their Applications

The ReaxFF methodology has been parameterized for numerous chemical systems across various research domains. These parameterizations are continually refined and expanded to address new scientific challenges. Below, we summarize key ReaxFF force fields and their targeted applications to assist researchers in selecting appropriate parameters for their specific systems.

Table 2: Selected ReaxFF Force Fields and Their Applications

| Force Field | Elements | Branch | Primary Applications | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CHO.ff | C, H, O | Combustion | Hydrocarbon oxidation | Chenoweth et al., J. Phys. Chem. A 2008 |

| HCONSB.ff | H, C, O, N, S, B | Combustion | Soot formation, coal combustion | Castro-Marcano et al., Combust. Flame 2012 |

| AuCSOH.ff | Au, C, S, O, H | Water | Gold surfaces, nanoparticles, glycine solvation | Keith et al., Phys. Rev. B 2010 |

| CuCl-H2O.ff | Cu, Cl, H, O | Water | Aqueous chloride, copper chloride | Rahaman et al., J. Phys. Chem. A 2010 |

| FeOCHCl.ff | Fe, O, C, H, Cl | Water | Iron-oxyhydroxide systems | Aryanpour et al., J. Phys. Chem. A 2010 |

| HE.ff | C, H, O, N | Combustion | High-energy materials, RDX | Zhang et al., J. Phys. Chem. B 2009 |

| LiS.ff | Li, S | Specialized | Lithium-sulfur batteries | [Citation:1] |

The CHO.ff force field has been extensively applied to hydrocarbon oxidation systems, providing insights into combustion processes and reaction mechanisms. Meanwhile, the HCONSB.ff parameterization extends this capability to more complex systems involving sulfur and boron, making it valuable for studying soot formation and coal combustion. For electrochemical applications, specialized force fields like LiS.ff enable the study of lithium diffusion in battery cathode materials, allowing researchers to compute diffusion coefficients and understand ion transport mechanisms [4].

In the domain of materials science and nanotechnology, force fields such as AuCSOH.ff facilitate investigations of metal surfaces, nanoparticles, and their interactions with organic molecules. These parameterizations have been instrumental in understanding catalytic processes, material stability, and interface phenomena. Similarly, FeOCHCl.ff supports research on corrosion, mineralogy, and environmental chemistry by accurately describing iron-oxyhydroxide systems and their interactions with aqueous environments.

When a suitable force field doesn't exist for a particular system, researchers can request parameters from the ReaxFF development community or engage in parameter optimization projects. The van Duin group at Penn State University regularly collaborates with researchers worldwide to develop new parameter sets for emerging applications, with over 1,600 requests from six continents demonstrating the method's global impact [17].

Experimental Protocol: Calculating Diffusion Coefficients in Battery Materials

The calculation of diffusion coefficients represents a common application of ReaxFF in energy materials research, particularly for battery systems. This protocol outlines a detailed methodology for computing lithium-ion diffusion coefficients in cathode materials, based on established tutorials and publications [4] [19]. The workflow encompasses system preparation, molecular dynamics simulation, and multiple analysis techniques for diffusion coefficient determination.

Diagram 1: Workflow for calculating diffusion coefficients using ReaxFF molecular dynamics. The process involves system preparation through simulated annealing, production MD simulations, and multiple analysis pathways.

System Preparation and Equilibration

Step 1: Import Crystal Structure

- Begin by importing your cathode material's crystal structure from a CIF file into your molecular dynamics simulation package (e.g., AMSinput)

- For lithium-sulfur systems, the alpha sulfur crystal structure serves as an appropriate starting point [4]

Step 2: Generate Lithiated System

- Use builder functionality to insert lithium atoms into the crystal structure

- For Li~0.4~S, insert 51 Li-atoms into the sulfur system using SMILES code

[Li] - Alternatively, employ Grand Canonical Monte Carlo (GCMC) for more accurate lithiation [4]

Step 3: Geometry Optimization with Lattice Relaxation

- Perform geometry optimization including lattice relaxation using an appropriate force field (e.g., LiS.ff)

- Set task to "Geometry Optimization" and enable "Optimize lattice" option

- Monitor the cell volume increase (e.g., from 3300 ų to 4400 ų for Li~0.4~S) as an indicator of successful relaxation [4]

Step 4: Create Amorphous Structure via Simulated Annealing

- Set up a molecular dynamics simulation with 30000 steps

- Configure temperature profile:

- 0-5000 steps: Constant at 300 K

- 5000-25000 steps: Heating from 300 K to 1600 K

- 25000-30000 steps: Cooling from 1600 K to 300 K

- Use Berendsen thermostat with damping constant of 100 fs

- This annealing process creates amorphous structures relevant for battery materials [4]

Production Simulation and Analysis

Step 5: Set Up Production MD Simulation

- Configure molecular dynamics simulation at target temperature (e.g., 1600 K)

- Use 10000 equilibration steps followed by 100000 production steps

- Set sample frequency to 5 (writing positions and velocities every 5 steps)

- Use Berendsen thermostat at target temperature with damping constant of 100 fs [4]

Step 6: Calculate Diffusion Coefficient via Mean Squared Displacement (MSD)

- After simulation completion, analyze trajectory using MSD analysis

- Select appropriate time range (e.g., steps 2000-22001)

- Set atoms to Li and max MSD frame to 5000 (corresponding to 6250 fs)

- Generate MSD plot and determine diffusion coefficient using the relationship:

[ D = \frac{\text{slope(MSD)}}{6} ]

- Verify linearity of MSD plot; non-linear regions indicate insufficient simulation length [4]

Step 7: Alternative Method - Velocity Autocorrelation Function (VACF)

- As validation, compute diffusion coefficient through velocity autocorrelation function

- Use same trajectory and select "Diffusion Coefficient (D)" property

- Set atoms to Li and max ACF step to 5000

- Determine D from the plateau region of the integral of VACF divided by 3:

[ D = \frac{1}{3} \int{t=0}^{t=t{max}} \langle \textbf{v}(0) \cdot \textbf{v}(t) \rangle \rm{d}t ]

- Compare results with MSD method; values should be approximately equal [4]

Step 8: Extrapolate to Lower Temperatures Using Arrhenius Equation

- To estimate diffusion coefficients at experimentally relevant temperatures (e.g., 300 K), perform simulations at multiple temperatures (600 K, 800 K, 1200 K, 1600 K)

- Use Arrhenius relationship to determine activation energy and pre-exponential factor:

[ \ln{D(T)} = \ln{D0} - \frac{Ea}{k_{B}}\cdot\frac{1}{T} ]

- Plot (\ln{(D(T))}) against (1/T) and perform linear fit to extract parameters

- Extrapolate to lower temperatures using fitted Arrhenius equation [4]

Successful implementation of ReaxFF simulations requires both specialized software tools and carefully prepared chemical systems. The following table outlines key components of the computational researcher's toolkit for force field applications and diffusion coefficient calculations.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Resources

| Resource | Type | Function/Purpose | Example Sources/References |

|---|---|---|---|

| LiS.ff | Force Field Parameters | Describes Li-S interactions for battery simulations | [4] |

| CHO.ff | Force Field Parameters | Models hydrocarbon oxidation for combustion studies | [12] |

| AMS/ReaxFF | Software Package | Molecular dynamics simulation with ReaxFF implementation | SCM (www.scm.com) |

| LAMMPS | Software Package | Open-source MD code with ReaxFF support | Plimpton, J. Comp. Phys. (1995) |

| PuReMD | Software Package | Purdue Reactive Molecular Dynamics code | [2] |

| CIF Files | Structural Data | Initial crystal structures for simulation setup | [4] |

| DFT Reference Data | Training Data | Quantum mechanical data for force field validation | [18] [2] |

Specialized software packages form the foundation of ReaxFF simulations. The AMS/ReaxFF platform provides a user-friendly interface with dedicated tools for ReaxFF simulations, including built-in analysis capabilities for diffusion coefficients [4]. Alternatively, LAMMPS offers open-source molecular dynamics capabilities with ReaxFF integration, while PuReMD is specifically optimized for reactive force field simulations [2]. These packages enable researchers to set up, run, and analyze complex reactive simulations across diverse chemical systems.

Force field parameters represent the essential "reagents" in molecular simulations, determining the accuracy and applicability of the calculations. Parameters such as LiS.ff for lithium-sulfur battery systems or CHO.ff for combustion chemistry encode the specific interactions between elements [4] [12]. These parameter sets are typically developed through careful optimization against quantum mechanical reference data and experimental measurements when available. Researchers can obtain specialized force field parameters by requesting them from development groups or through collaborative projects [17].

Initial structural files in CIF format provide the starting configurations for simulations, while DFT reference data serves as the gold standard for force field validation and development [18] [2]. The availability of high-quality training data covering relevant chemical spaces is crucial for developing accurate and transferable force fields. Recent advances in parameter optimization frameworks that combine simulated annealing and particle swarm optimization algorithms have shown promising improvements in both the efficiency and accuracy of force field development [18].

The selection of appropriate force fields represents a critical step in molecular simulations that significantly influences the reliability and interpretability of computational results. For reactive systems requiring dynamic bond formation and cleavage, ReaxFF provides a powerful framework that balances computational efficiency with chemical accuracy. The methodology outlined in this application note—from force field selection to specialized protocols for diffusion coefficient calculation—offers researchers a structured approach for implementing ReaxFF in their investigations of complex chemical processes.

Future developments in ReaxFF methodology continue to expand its capabilities and applications. Ongoing research focuses on improving parameter optimization through advanced algorithms, enhancing transferability across broader chemical spaces, and integrating ReaxFF with other simulation techniques such as computational fluid dynamics [18] [17]. These advances will further establish ReaxFF as an indispensable tool in the computational researcher's toolkit, enabling increasingly accurate simulations of complex materials and processes across chemistry, materials science, and biological applications.

Step-by-Step Workflow: Calculating Diffusion Coefficients in Li-ion Battery Materials

The initial construction of a realistic atomistic model is a critical first step in molecular dynamics (MD) simulations of complex materials, such as those found in lithium-ion batteries. This application note details the protocols for building a Li~0.4~S cathode system, as used in ReaxFF MD simulations to compute lithium-ion diffusion coefficients. The procedures outlined herein—importing a crystal structure, manipulating it by inserting particles, and performing essential equilibration—form the foundation for subsequent simulated annealing and production MD runs. This framework is inspired by and adapted from established computational studies on lithiated sulfur cathode materials [4].

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists the essential computational "reagents" and their functions required to perform the system-building procedure.

Table 1: Essential Research Reagent Solutions and Software

| Item Name | Function/Description | Critical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| AMSinput | Graphical user interface for setting up calculations in the Amsterdam Modeling Suite [4]. | Used for all steps: importing coordinates, structure manipulation, and setting calculation parameters. |

| ReaxFF Force Field | Reactive force field to describe atomic interactions; enables modeling of bond formation and breaking [5] [2]. | The LiS.ff parameter file is used for geometry optimization and MD simulations [4]. |

| Crystal Structure File | Initial atomic configuration of the system. | Typically a Crystallographic Information File (.cif) for crystal structures like Sulfur(α) [4]. |

| Builder Tool | Integrated utility within AMSinput for inserting molecules or atoms into an existing structure [4]. | Used to randomly insert Lithium atoms into the Sulfur crystal framework. |

Protocol: System Generation and Equilibration

This section provides the detailed methodology for constructing and initially relaxing the Li~0.4~S system.

Importing the Sulfur(α) Crystal Structure

Objective: To load the initial crystal structure of the cathode material.

- Open a new AMSinput window.

- Select the ReaxFF engine.

- Import the crystal structure: File → Import Coordinates.

- In the file dialog, select and open the downloaded CIF file for the Sulfur(α) crystal [4].

Generating the Li~0.4~S System by Inserting Lithium Particles

Objective: To create the lithiated cathode material by randomly inserting Lithium atoms into the crystal lattice.

- Access the Builder: In AMSinput, navigate to Edit → Builder.

- Configure the insertion:

- Tick the checkbox for Use number of molecules.

- In the SMILES or xyz-file field, enter

[Li](the SMILES code for a single Lithium atom). - Set N mols to

51to achieve the desired Li~0.4~S stoichiometry.

- Execute the insertion: Click Generate Molecules. The Li atoms will be randomly placed into the simulation box.

- Close the Builder window once the operation is complete [4].

Equilibrating the System via Geometry Optimization

Objective: To relax the newly constructed, high-energy structure to a stable local minimum and allow the unit cell to adjust.

- Set the calculation task: In the main AMSinput panel, select Task → Geometry Optimization.

- Select the force field: Click the folder icon next to Force Field and select the

LiS.fffile. - Enable lattice optimization:

- Go to Details → Geometry Optimization.