Bridging the Gap: A Comprehensive Framework for Validating Molecular Dynamics Diffusion Coefficients with Experimental Data

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and scientists on the critical process of validating molecular dynamics (MD) simulations against experimental diffusion data.

Bridging the Gap: A Comprehensive Framework for Validating Molecular Dynamics Diffusion Coefficients with Experimental Data

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and scientists on the critical process of validating molecular dynamics (MD) simulations against experimental diffusion data. It explores the foundational importance of accurate diffusion coefficients across fields, from battery material science to drug development. The content details state-of-the-art methodological approaches, including novel experimental techniques like the Surface Concentration Potential Response (SCPR) method and advanced MD analysis. It systematically addresses common pitfalls and optimization strategies for both simulation and experiment, emphasizing the impact of analysis protocols on result uncertainty. Finally, the article presents robust validation frameworks and comparative analyses, showcasing successful integrations of MD with techniques like tracer diffusion and machine learning. This resource is designed to enhance the reliability of diffusion data, thereby accelerating innovation in material design and pharmaceutical development.

Why Validation Matters: The Critical Role of Diffusion Coefficients in Material and Pharmaceutical Science

Diffusion coefficients serve as a critical quantitative bridge between microscopic molecular motion and macroscopic performance in fields as diverse as electrochemistry and pharmaceutical science. In lithium-ion batteries, the solid-state diffusion coefficient of Li+ ions directly governs charge/discharge rates and power density, while in drug delivery systems, the diffusion coefficient of therapeutic molecules through carrier materials determines release kinetics and therapeutic efficacy. Accurate determination of this parameter is therefore essential for optimizing material design and system performance across these domains.

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations have emerged as a powerful computational tool for predicting diffusion coefficients from first principles, providing atomistic insights often inaccessible to experimental techniques alone. However, the validation of MD-predicted diffusion coefficients against reliable experimental data remains a fundamental challenge, requiring sophisticated measurement approaches and cross-method verification. This comparison guide examines state-of-the-art methodologies for diffusion coefficient determination across battery and pharmaceutical applications, providing researchers with a framework for selecting appropriate techniques and validating computational predictions.

Diffusion in Battery Systems: Measurement and Validation

Experimental Techniques for Determining Solid-State Diffusion Coefficients

Table 1: Comparison of Experimental Techniques for Battery Diffusion Coefficient Measurement

| Technique | Principle | Measured Parameter | Typical Duration | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GITT [1] [2] | Applies short current pulses followed by relaxation to equilibrium | Chemical diffusion coefficient (Ds) | 8-100x longer than typical galvanostatic cycle [1] | Does not effectively separate solid from liquid diffusion contributions [2] |

| PITT [3] | Applies potential steps and monitors current decay | Chemical diffusion coefficient (Ds) | Varies with system | Requires sophisticated interpretation models |

| ICI Method [1] | Introduces transient current interruptions during constant-current cycling | Diffusion coefficient (D) | <15% of GITT time [1] | Requires linear regression of potential vs. √t data |

| DRT Method [2] | Deconvolves EIS data to separate processes by time constant | Solid diffusion coefficient | Relatively fast | Requires comprehensive physico-chemical model for interpretation [2] |

| EIS [2] | Measures impedance across frequency spectrum | Warburg coefficient related to diffusion | Moderate | Spectrum interpretation can be ambiguous |

Galvanostatic Intermittent Titration Technique (GITT)

The GITT method remains the most widely applied technique for determining Li+ diffusion coefficients in insertion electrode materials. The technique alternates between constant-current pulses and relaxation periods until equilibrium potential is reached. The diffusion coefficient is calculated using the following equation [2]:

$$ D{s,GITT} = \frac{4L^2}{\pi\Delta t}\left(\frac{\Delta Es}{\Delta E_t}\right)^2 $$

Where L is the diffusion length, Δt is the current pulse duration, ΔEs is the change in equilibrium potential, and ΔEt is the overpotential caused by dynamic processes.

Recent research has revealed significant limitations in traditional GITT analysis. The method assumes planar particle geometry, uniform particle size distribution, and neglects contributions from liquid diffusion and porous electrode structure [2]. Comparative studies show that GITT typically underestimates solid diffusion coefficients as it cannot effectively separate solid diffusion contributions from liquid diffusion processes [2].

Intermittent Current Interruption (ICI) Method

The ICI method has emerged as an efficient alternative to GITT, introducing short current pauses (typically 1-10 seconds) during constant-current cycling. The voltage response during current pauses is analyzed according to [1]:

$$ \Delta E(\Delta t) = E(\Delta t) - E_I = -IR - Ik\sqrt{\Delta t} $$

Where R is internal resistance and k is the diffusion resistance coefficient. The ICI method can characterize the same range of states of charge in less than 15% of the time required by GITT, significantly accelerating parameter determination [1]. Validation studies demonstrate excellent agreement between ICI and GITT results where semi-infinite diffusion conditions apply [1].

Distribution of Relaxation Times (DRT) Method

The DRT method deconvolves electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) data to separate overlapping processes based on their characteristic time constants. This approach enables more effective separation of solid diffusion from other processes compared to GITT. Recent advancements have developed comprehensive physico-chemical models for interpreting DRT spectra, allowing more accurate determination of solid diffusion coefficients without the liquid diffusion interference that plagues GITT measurements [2].

Experimental Workflow for Battery Diffusion Coefficient Measurement

Molecular Dynamics Approaches for Battery Materials

Molecular dynamics simulations provide a computational approach for predicting diffusion coefficients from atomic-scale principles. Recent MD studies of battery materials have achieved improved accuracy through longer simulation times and careful monitoring of sub-diffusive dynamics [4].

Table 2: MD-Calculated Diffusion Coefficients for Battery Materials (300K) [5]

| Material | Crystal Structure | MD Diffusion Coefficient (m²/s) | Activation Energy (eV) |

|---|---|---|---|

| LiFePOâ‚„ | Olivine | 9.18 × 10â»Â¹Â¹ | 0.34 |

| LLZO | Garnet | 4.00 × 10â»Â¹Â² | 0.35 |

| NASICON | NASICON | 6.77 × 10â»Â¹Â¹ | 0.31 |

MD simulations of LiFePOâ‚„, LLZO, and NASICON structures reveal significant differences in ionic mobility between crystal structures, with NASICON exhibiting the highest diffusion coefficient [5]. The accuracy of MD predictions varies substantially between materials, with LLZO showing a 2-order-of-magnitude deviation from experimental values, highlighting the need for careful validation [5].

Advanced machine learning approaches are now being integrated with MD simulations to improve prediction accuracy. Symbolic regression frameworks can derive analytical expressions connecting diffusion coefficients to macroscopic properties like temperature and density, potentially bypassing computationally expensive MD simulations for routine predictions [6]. These ML models can achieve remarkable accuracy, with reported R² values up to 0.996 when trained on comprehensive MD datasets [5].

Diffusion in Drug Delivery Systems: Methodologies and Applications

Experimental Determination of Drug Diffusion Coefficients

Table 3: Experimental Methods for Drug Diffusion Coefficient Measurement

| Method | Principle | Typical Applications | Detection Method | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FTIR Spectroscopy [7] | Monitors drug concentration via IR absorption | Artificial mucus, hydrogel systems | Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy | Fast, non-invasive, suitable for complex media |

| Fluorescence-Based [8] | Tracks fluorescent particle penetration | Soft hydrogels, tissue engineering | Fluorescence intensity measurements | Simple, adaptable to different hydrogel stiffnesses |

| Vapour Sorption Analysis [4] | Measures uptake/release kinetics | Polymeric medical devices | Mass change measurements | Validates MD predictions for drug-polymer systems |

| CFD-ML Hybrid [9] | Solves mass transfer equations in 3D domain | Controlled release formulations | Machine learning prediction | Enables 3D concentration distribution modeling |

FTIR Spectroscopy Method

The FTIR approach couples spectroscopic measurement with Fickian diffusion principles to determine drug diffusivities through biological barriers like artificial mucus. In this method, the drug solution is placed in contact with an artificial mucus layer, and FTIR spectra are collected at constant intervals to monitor quantitative changes in peaks corresponding to specific drug functional groups [7].

Peak height changes are correlated to concentration via Beer's Law, and Fick's 2nd Law of Diffusion is applied with Crank's trigonometric series solution for a planar semi-infinite sheet. Using this approach, researchers determined diffusivity coefficients of D = 6.56 × 10â»â¶ cm²/s for theophylline and D = 4.66 × 10â»â¶ cm²/s for albuterol through artificial mucus [7]. This coupled experimental-computational approach provides a fast, non-invasive methodology for rapidly assessing drug diffusion profiles through complex biological media.

Fluorescence-Based Method in Hydrogels

For drug delivery and tissue engineering applications, a simple fluorescence-based method has been developed to determine diffusion coefficients in soft hydrogels. This approach uses fluorescence intensity measurements from a microplate reader to determine concentrations of diffusing particles at different penetration distances in agarose hydrogels [8].

The method involves analyzing diffusion behavior of fluorescent particles with different molecular weights (e.g., fluorescein, mNeonGreen, and fluorophore-labeled bovine serum albumin) through hydrogels of varying stiffness (0.05-0.2% agarose). Diffusion coefficients are obtained by fitting experimental data to a one-dimensional diffusion model, with results showing good agreement with literature values [8]. The approach demonstrates sensitivity to variations in diffusion conditions, enabling study of solute-hydrogel interactions relevant to controlled release systems.

Computational Prediction of Drug Diffusion

Molecular Dynamics Simulations

Atomistic MD simulations have been successfully applied to predict diffusion coefficients in model drug delivery systems, representing a dramatic improvement in accuracy compared to previous simulation predictions. Key advancements include the use of microsecond-scale simulations and identification of metrics for monitoring sub-diffusive dynamics, which previously led to dramatic over-prediction of diffusion coefficients [4].

Successful MD approaches have identified relationships between diffusion and fast dynamics in slowly diffusing systems, potentially serving as a means to more rapidly predict diffusion coefficients without requiring full equilibrium simulations [4]. These advances provide essential insights for utilizing atomistic MD to predict diffusion coefficients of small to medium-sized molecules in condensed soft matter systems relevant to pharmaceutical applications.

Hybrid CFD-Machine Learning Approaches

Innovative hybrid approaches combine computational fluid dynamics (CFD) with machine learning to predict drug diffusion in three-dimensional spaces. These methods solve mass transfer equations including diffusion in a 3D domain, then use the generated data (over 22,000 coordinate-concentration data points) to train ML models including ν-Support Vector Regression (ν-SVR), Kernel Ridge Regression (KRR), and Multi Linear Regression (MLR) [9].

Hyperparameter optimization using the Bacterial Foraging Optimization (BFO) algorithm has demonstrated exceptional performance, with ν-SVR achieving an R² score of 0.99777, significantly outperforming other regression models [9]. This hybrid approach enables accurate prediction of 3D concentration distributions, which is crucial for optimizing controlled release formulations without requiring extensive experimental measurements.

Drug Diffusion Coefficient Determination Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Diffusion Studies

| Material/Reagent | Function/Application | Field | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| LiNiâ‚€.₈Mnâ‚€.â‚Coâ‚€.â‚Oâ‚‚ (NMC811) | Cathode material for diffusion studies | Battery Research | High energy density, well-characterized Li+ diffusion |

| LiFePOâ‚„ | Olivine cathode material | Battery Research | Safety, stability, moderate diffusion coefficient |

| NASICON (Na₃Zrâ‚‚Siâ‚‚POâ‚â‚‚) | Solid electrolyte material | Battery Research | High ionic conductivity, 3D diffusion pathways |

| LLZO (Li₇La₃Zrâ‚‚Oâ‚â‚‚) | Garnet-type solid electrolyte | Battery Research | High Li+ conductivity, stability against Li metal |

| Artificial Mucus | Biomimetic barrier for drug diffusion | Pharmaceutical Research | Replicates physiological diffusion barriers |

| Agarose Hydrogels | Tunable matrix for diffusion studies | Pharmaceutical Research | Controlled stiffness (0.05-0.2%), biocompatible |

| Theophylline | Model bronchodilator drug | Pharmaceutical Research | Standard compound for diffusion methodology validation |

| Albuterol | β2-adrenergic receptor agonist | Pharmaceutical Research | Representative asthma medication for permeation studies |

| Fluorescein | Fluorescent tracer molecule | Pharmaceutical Research | Small molecular weight model compound |

| mNeonGreen | Fluorescent protein | Pharmaceutical Research | Medium molecular weight protein tracer |

| Bovine Serum Albumin | Model protein drug | Pharmaceutical Research | Large molecular weight protein for diffusion studies |

| 15-Aminopentadecanoic acid | 15-Aminopentadecanoic Acid|CAS 17437-21-7 | Bench Chemicals | |

| N-(5-hydroxypentyl)maleimide | N-(5-hydroxypentyl)maleimide, MF:C9H13NO3, MW:183.20 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

The accurate determination of diffusion coefficients represents a critical challenge with significant implications for both battery performance and drug efficacy. Experimental techniques ranging from electrochemically-based methods (GITT, PITT, ICI) for batteries to spectroscopy and fluorescence-based approaches for pharmaceuticals each present unique advantages and limitations. Molecular dynamics simulations offer powerful computational alternatives but require careful validation against experimental data, particularly through monitoring of sub-diffusive dynamics and simulation duration adequacy.

Emerging approaches combining machine learning with both computational and experimental methods show exceptional promise for accelerating diffusion coefficient prediction while maintaining physical consistency. Symbolic regression can derive physically interpretable equations connecting macroscopic properties to diffusion coefficients [6], while hybrid CFD-ML approaches enable rapid prediction of 3D concentration distributions in drug delivery systems [9]. The integration of these advanced computational methods with robust experimental validation provides a pathway toward more reliable diffusion coefficient determination across multiple domains, ultimately enhancing our ability to design optimized materials for energy storage and pharmaceutical applications.

In the field of molecular dynamics (MD) simulation, a significant validation crisis exists regarding the calculation of diffusion coefficients, where researchers frequently encounter orders-of-magnitude discrepancies in reported values. These inconsistencies present substantial challenges for scientists relying on computational predictions, particularly in pharmaceutical development where diffusion properties inform drug delivery mechanisms and bioavailability predictions. The crisis stems from methodological variations, computational artifacts, and validation gaps between simulated and experimental results. This guide objectively compares predominant methodologies for calculating self-diffusion coefficients, provides supporting experimental validation data, and details protocols for improving consistency in MD diffusion research.

Comparative Analysis of MD Diffusion Coefficient Methodologies

Molecular dynamics simulations calculate self-diffusion coefficients (D) primarily through three approaches: traditional Mean Squared Displacement (MSD) analysis, novel physical models, and emerging machine learning methods. Each methodology offers distinct advantages and limitations in accuracy, computational demand, and physical interpretability, contributing to the varying reliability of reported diffusion coefficients across scientific literature.

Table 1: Comparison of Primary Methodologies for Diffusion Coefficient Calculation in MD Simulations

| Methodology | Theoretical Basis | Reported Accuracy | Computational Demand | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional MSD-t Model | Einstein-Smoluchowski relation via MSD slope analysis | Varies significantly with simulation parameters | Moderate to High (requires long trajectories) | Sensitive to finite-size effects, statistical noise in MSD fitting [10] [11] |

| Characteristic Length-Velocity Model | Product of characteristic length (L) and diffusion velocity (V): D = L × V | 8.18% average deviation from experimental data [10] | Moderate (requires velocity statistics) | Newer method with limited validation across diverse systems [10] |

| Symbolic Regression (ML) | Machine-derived equations based on macroscopic parameters (T, Ï, H) | R² > 0.96 for most fluids [6] | Low (once trained) | Requires extensive training data; limited interpretability [6] |

| SLUSCHI Automated Workflow | First-principles MD with automated MSD analysis | Quantitative trends for inaccessible experimental conditions [11] | Very High (AIMD required) | Computationally intensive; limited to smaller systems [11] |

Quantitative Validation Against Experimental Data

Comprehensive validation studies demonstrate how each methodology performs against experimental diffusion coefficients across diverse systems. Researchers tested the characteristic length-velocity model in 35 systems with wide pressure and concentration variations, including 12 liquid systems and 23 gas/organic vapor systems [10]. The total average relative deviation of predicted values with respect to experimental results was 8.18%, indicating the model's objective and rational basis [10]. Similarly, symbolic regression approaches achieved coefficients of determination (R²) higher than 0.98 for most molecular fluids, with average absolute deviations (AAD) below 0.5 for the reduced self-diffusion coefficient [6].

Table 2: Experimental Validation Results Across Methodologies and Systems

| Validated System | Methodology | Experimental Reference | Reported Deviation | Validation Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liquid Systems (12 total) | Characteristic Length-Velocity Model | Literature values | 8.18% average relative deviation [10] | Wide concentration range |

| Gas & Organic Vapor Systems (23 total) | Characteristic Length-Velocity Model | Literature values | 8.18% average relative deviation [10] | Wide pressure range |

| Hâ‚‚/CHâ‚„ in Water | MD with Experimental Validation | Experimental solubility/diffusivity measurements | Mutual validation [12] | 294-374 K, 5.3-300 bar |

| Nine Molecular Fluids (Bulk) | Symbolic Regression | MD simulation database | R² > 0.98, AAD < 0.5 [6] | Reduced temperature and density parameters |

| Al-Cu Liquid Alloys | SLUSCHI Automated Workflow | First-principles benchmark | Quantitative trends [11] | High-temperature liquid states |

Detailed Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Characteristic Length-Velocity Model Implementation

The characteristic length-velocity model proposes that the diffusion coefficient can be described as the product of characteristic length (L) and diffusion velocity (V), according to the equation D = L × V [10]. This approach endows Fick's law diffusion coefficient with a clearer physical meaning compared to traditional definitions.

Protocol Implementation:

- System Preparation: Construct molecular systems with appropriate force field parameters and initial configurations matching experimental conditions of pressure and concentration [10].

- Molecular Dynamics Simulation: Perform production MD runs using ensembles appropriate to the system (NVT, NPT) with sufficient equilibration period.

- Trajectory Analysis: Calculate the statistical average diffusion velocity and characteristic length of molecules using analysis scripts applied to trajectory data [10].

- Diffusion Coefficient Calculation: Determine D directly using the product of the obtained characteristic length and diffusion velocity values.

- Validation: Compare calculated diffusion coefficients with experimental values from literature using relative deviation analysis [10].

This methodology demonstrates particular advantage in its straightforward conceptual foundation and reduced sensitivity to trajectory length compared to traditional MSD approaches [10].

Traditional MSD-Based Diffusion Calculation

The mean squared displacement (MSD) method remains the most widespread approach for calculating diffusion coefficients from MD simulations, based on the Einstein-Smoluchowski relation of Brownian motion theory [11].

Protocol Implementation:

- Trajectory Production: Run sufficiently long MD simulations to achieve normal diffusive regime, typically requiring hundreds of picoseconds to nanoseconds depending on system [11].

- Unwrapped Coordinates: Process trajectories to maintain unwrapped coordinates that account for periodic boundary crossings [11].

- MSD Calculation: For each species α, compute MSDα(t) = (1/Nα)Σ⟨|rᵢ(t₀+t) - rᵢ(t₀)|²⟩ averaged over all time origins (t₀) [11].

- Linear Regression: Fit the linear portion of the MSD versus time curve, excluding initial ballistic regime and late-time noisy regions [10].

- Diffusion Coefficient Extraction: Calculate Dα = (1/(2d)) × (d(MSD)/dt), where d=3 for three-dimensional systems [11].

- Error Estimation: Employ block averaging techniques to quantify statistical uncertainties in the calculated diffusivities [11].

The SLUSCHI automated workflow implements this methodology with robust error estimation through block averaging, generating diagnostic plots including MSD curves, running slopes, and velocity autocorrelations to identify proper diffusive regimes [11].

Symbolic Regression Machine Learning Approach

Symbolic regression (SR) represents an emerging machine learning methodology that discovers mathematical expressions to fit simulation data without presuming predetermined functional forms [6].

Protocol Implementation:

- Training Data Generation: Perform MD simulations across varied state points (temperature, density) for each molecular fluid of interest to create comprehensive training datasets [6].

- Reduced Parameter Calculation: Convert physical parameters to reduced units (T, Ï, D*) using molecular scaling factors (ε, σ, m) [6].

- Symbolic Regression Training: Implement genetic programming algorithms to explore mathematical expression space, correlating reduced self-diffusion coefficients with macroscopic parameters [6].

- Expression Selection: Apply multi-stage selection considering accuracy (R², AAD), complexity, and recurrence across random seeds to identify optimal expressions [6].

- Validation: Evaluate derived expressions against withheld validation data using statistical measures including coefficient of determination (R²) and average absolute deviation (AAD) [6].

For bulk fluids, the derived SR expressions typically take the form DSR = αâ‚T^α₂Ï*^(α₃ - α₄), with parameters αᵢ varying for each molecular fluid, reflecting the physically consistent inverse relationship with density and proportional relationship with temperature [6].

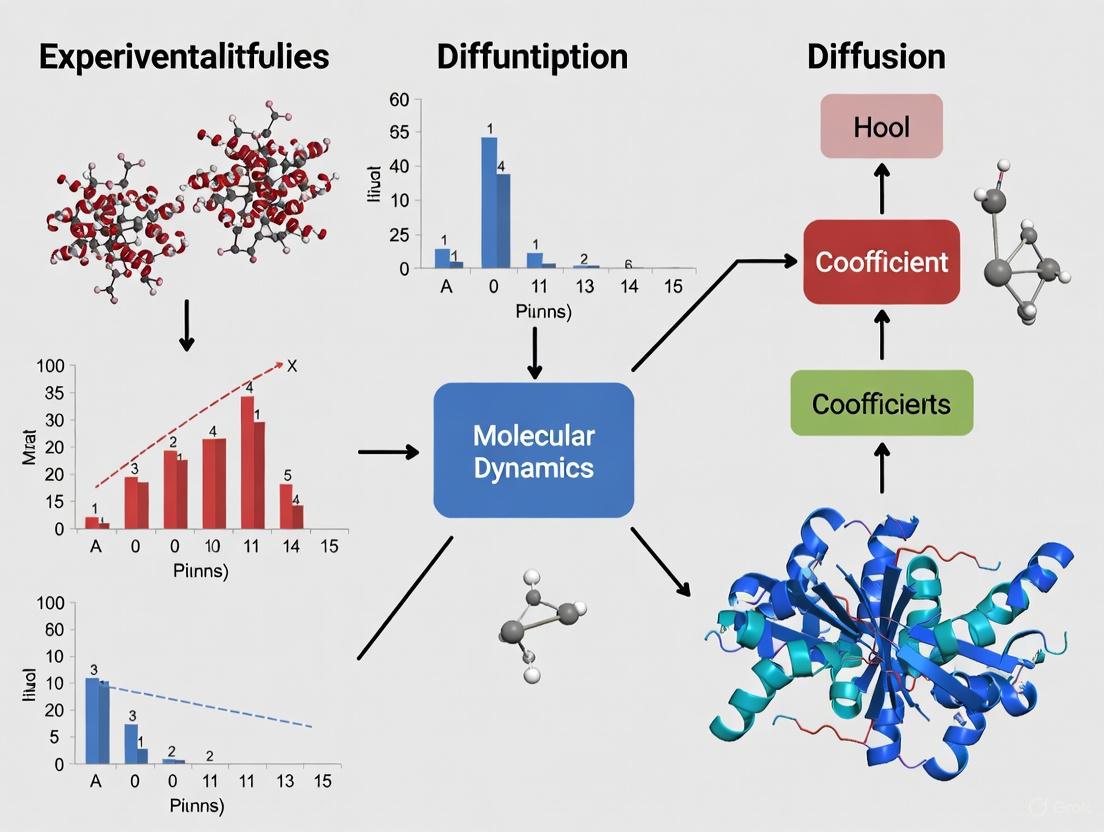

Visualization of Methodological Relationships and Workflows

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for MD Diffusion Coefficient Validation

| Tool/Solution | Function | Implementation Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Dynamics Engines | Performs numerical integration of equations of motion for molecular systems | VASP (for AIMD), LAMMPS, GROMACS, AMBER [11] |

| Trajectory Analysis Tools | Processes MD trajectories to compute diffusion coefficients and related properties | SLUSCHI-Diffusion module, VASPKIT, custom Python/Perl scripts [10] [11] |

| Validation Datasets | Provides experimental reference values for method calibration | Literature diffusion coefficients for standard systems (water, organic liquids, gases) [10] [12] |

| Symbolic Regression Frameworks | Derives mathematical expressions connecting macroscopic parameters to diffusion coefficients | Genetic programming algorithms implementing SR [6] |

| Error Quantification Methods | Estimates statistical uncertainties in calculated diffusivities | Block averaging techniques, windowed linear fits [11] |

| Force Field Parameter Sets | Defines interatomic potentials for specific molecular systems | Lennard-Jones parameters, AMBER force fields, CHARMM parameters [6] |

| Bis-PEG7-t-butyl ester | Bis-PEG7-t-butyl ester, CAS:439114-17-7, MF:C26H50O11, MW:538.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 1,3,5-Triiodo-2-methoxybenzene | 1,3,5-Triiodo-2-methoxybenzene, CAS:63238-41-5, MF:C7H5I3O, MW:485.83 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The validation crisis in MD diffusion coefficients stems from methodological diversity and insufficient standardization rather than intrinsic failures in physical models. The characteristic length-velocity model demonstrates that simple physical interpretations can achieve respectable 8.18% average deviation from experimental values [10], while symbolic regression approaches offer promising alternatives with R² values exceeding 0.96 for most fluids [6]. Automated workflows like SLUSCHI provide robust, reproducible computational protocols with built-in error estimation [11]. For researchers addressing this validation crisis, we recommend: (1) implementing multiple methodological approaches for cross-validation, (2) adhering to detailed computational protocols with sufficient sampling, (3) utilizing automated analysis tools with error quantification, and (4) establishing standardized validation against reference experimental systems. Through methodological rigor and comprehensive validation, the field can progressively resolve the orders-of-magnitude discrepancies that currently challenge computational predictions of diffusion coefficients.

The accurate determination of diffusion coefficients is a cornerstone of materials science research, particularly in the development of energy storage systems and the characterization of new materials. The validation of molecular dynamics (MD) simulated diffusion data against experimental measurements is a critical step in ensuring model accuracy. This process is fraught with challenges, primarily centered on selecting appropriate experimental methods and accounting for interfacial phenomena that complicate data interpretation. Two dominant model paradigms—linear and radial diffusion—offer distinct approaches for characterizing mass transport, each with unique advantages and limitations. Furthermore, the open-circuit potential (OCP), a key parameter in many electrochemical methods, introduces nonlinearity that can significantly impact the accuracy of derived diffusion coefficients if not properly managed. This guide provides an objective comparison of these key challenges, supported by experimental data and detailed protocols, to inform researchers and drug development professionals in their experimental design and data validation workflows.

Diffusion Model Comparison: Linear vs. Radial

Fundamental Principles and Applications

Linear diffusion models characterize mass transport along a single spatial dimension and are most applicable to systems with planar electrodes or well-defined one-dimensional pathways. These models are mathematically straightforward, based on Fick's laws of diffusion, and are widely employed in electrochemical techniques for determining solid-state diffusion coefficients [13]. The galvanostatic intermittent titration technique (GITT), for instance, operates on the principle of linear diffusion under semi-infinite conditions, deriving diffusion coefficients from voltage transients during constant-current pulses [13].

Radial diffusion models describe mass transport originating from or converging to a central point, creating spherical concentration gradients. This model is particularly relevant for systems with nano-particle impacts, porous electrodes with complex tortuosity, or any scenario where diffusion occurs around microscopic structures with high curvature [14]. The Bayesian inference framework applied to Van Allen radiation belt data demonstrates how radial diffusion parameters can be probabilistically determined when boundary conditions are uncertain [15].

Comparative Analysis of Model Characteristics

Table 1: Comparison of Linear and Radial Diffusion Model Characteristics

| Characteristic | Linear Diffusion Models | Radial Diffusion Models |

|---|---|---|

| Mathematical Foundation | Fick's second law in one dimension [13] | Fick's second law in spherical coordinates [15] |

| Spatial Dependence | ∠√(Dt) (where D is diffusion coefficient, t is time) [13] | Complex time dependence with radial terms [15] |

| Experimental Applications | GITT, ICI method for battery materials [13] | Nano-impact experiments, porous systems [14] |

| Boundary Conditions | Defined planar boundaries | Spherical or radial boundaries |

| Computational Complexity | Generally lower | Often higher, may require Bayesian inference [15] |

| Parameter Uncertainty | Typically point estimates | Probabilistic estimates with confidence intervals [15] |

Implications for MD Diffusion Coefficient Validation

The choice between linear and radial diffusion models profoundly impacts the validation of MD-simulated diffusion coefficients. For layered materials or intercalation compounds with well-defined diffusion channels, linear models often provide satisfactory agreement with experimental data [13] [16]. However, for nanoparticle systems or porous composites where diffusion occurs in multiple dimensions with complex boundary conditions, radial models may offer more physically realistic validation benchmarks [14]. The Bayesian approach to radial diffusion parameter estimation is particularly valuable as it provides uncertainty quantification—a crucial feature when assessing the statistical significance of discrepancies between simulation and experiment [15].

Open-Circuit Potential Nonlinearity: Challenges and Solutions

Fundamental Nature of OCP Nonlinearity

The open-circuit potential represents the equilibrium electrode potential in the absence of external current, established by quasi-equilibrated electrode reactions at the material interface [17]. OCP nonlinearity arises from the complex, non-ideal behavior of electrochemical interfaces, where the potential exhibits a logarithmic dependence on ion concentration according to the Nernst equation, but deviates due to activity coefficients, mixed potentials, and surface adsorption phenomena [17].

This nonlinearity introduces significant challenges in diffusion coefficient determination, as most electrochemical methods assume a linear relationship between concentration and potential when deriving diffusion parameters from voltage transients. The potential of zero charge (PZC), a specific OCP point where the electrode surface exhibits no net charge, serves as an important reference for understanding these nonlinearities [14]. At potentials different from the PZC, the electrochemical interface becomes charged, creating a double layer that complicates the interpretation of diffusion-limited processes.

Impact on Diffusion Coefficient Measurements

Nonlinear OCP behavior introduces systematic errors in diffusion coefficient measurements through several mechanisms:

Concentration-Potential Relationship: Techniques like GITT require accurate determination of dE/dx (potential versus composition) for calculating diffusion coefficients. OCP nonlinearity makes this derivative concentration-dependent, violating the assumption of linear thermodynamics [13] [17].

Relaxation Time Artifacts: In intermittent techniques, the assumption that OCP stabilizes indicates equilibrium is complicated by slow interfacial processes that continue even after the bulk diffusion has equilibrated, leading to overestimation of relaxation times and underestimation of diffusion coefficients [13].

Potential-Dependent Diffusion: The diffusion coefficient itself may become potential-dependent in systems with strong electron-ion correlations, creating a coupling between OCP nonlinearity and transport properties [17].

Table 2: Experimental OCP and Diffusion Coefficient Data for Various Material Systems

| Material System | PZC Value | Diffusion Coefficient (m²/s) | Measurement Technique | Impact of OCP Nonlinearity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Graphene Nanoplatelets | -0.14 ± 0.03 V vs. SCE [14] | 2.0 ± 0.8 × 10â»Â¹Â³ [14] | Nano-impact chronoamperometry | Electron transfer direction changes at PZC [14] |

| LiNiâ‚€.₈Mnâ‚€.â‚Coâ‚€.â‚Oâ‚‚ (NMC811) | Varies with state of charge [13] | Dependent on lithiation level [13] | GITT/ICI Method | OCP slope approximation affects accuracy [13] |

| Pd/C in Aqueous Media | Est. from H₂/H₃O⺠equilibrium [17] | Not specified | Kinetic analysis | OCP stabilizes cationic species, lowering activation barriers [17] |

Methodological Approaches to Mitigate OCP Nonlinearity

Several experimental strategies can minimize the impact of OCP nonlinearity on diffusion measurements:

Intermittent Current Interruption (ICI) Method: This approach circumvents long relaxation times by approximating the OCP slope using the iR-corrected pseudo-OCP measured at low C-rates, significantly reducing experimental time while maintaining accuracy [13].

Potential of Zero Charge Determination: Nano-impact experiments can simultaneously determine both PZC and diffusion coefficient, providing a critical reference point for interpreting potential-dependent phenomena [14].

Controlled Potential Windows: Operating electrochemical measurements within limited potential ranges where OCP exhibits more linear behavior can reduce nonlinearity effects, though this may restrict the accessible composition range.

Nonlinear Fitting Approaches: Implementing regression methods that explicitly account for the nonlinear OCP profile through higher-order terms or piecewise approximations can improve parameter estimation [13].

Experimental Protocols for Diffusion Coefficient Determination

Galvanostatic Intermittent Titration Technique (GITT)

Principle: GITT applies short constant-current pulses followed by long relaxation periods to achieve equilibrium. The diffusion coefficient is derived from the voltage transient during the current pulse and the change in equilibrium potential [13].

Step-by-Step Protocol:

- Apply a constant current pulse for a duration where semi-infinite diffusion conditions hold (typically 5-40 seconds for battery materials) [13].

- Switch off current and allow the system to relax until the voltage becomes invariant (may require >1 hour for full equilibrium) [13].

- Record the voltage response throughout both current and relaxation phases.

- Calculate the diffusion coefficient using the equation:

D = (4/πτ) * (Vₘ/A)² * (ΔEₛ/ΔEₜ)²

Where τ is current pulse duration, Vₘ is molar volume, A is surface area, ΔEₛ is steady-state voltage change, and ΔEₜ is voltage change during constant current pulse [13].

- Repeat across multiple states of charge to characterize composition dependence.

Advantages and Limitations:

- Advantages: Well-established theoretical foundation, direct measurement, applicability to various materials.

- Limitations: Extremely time-consuming, sensitive to OCP nonlinearity, requires accurate knowledge of material geometry [13].

Intermittent Current Interruption (ICI) Method

Principle: ICI introduces brief current pauses (typically 1-10 seconds) during constant-current cycling, enabling continuous monitoring of internal resistance and diffusion resistance coefficient [13].

Step-by-Step Protocol:

- During constant-current cycling (e.g., C/10 rate for battery materials), introduce regular short current interruptions (e.g., 10 seconds every 300 seconds) [13].

- Measure the potential change (ΔE) versus square root of step time (√Δt) during each current pause.

- Perform linear regression of ΔE against √Δt to extract intercept (internal resistance, R) and slope (diffusion resistance coefficient, k) [13].

- Derive the diffusion coefficient using the relationship between the diffusion resistance coefficient and the Warburg element from electrochemical impedance spectroscopy.

- Approximate the OCP slope using the iR-corrected pseudo-OCP to avoid long relaxation steps.

Advantages and Limitations:

- Advantages: Requires less than 15% of GITT experimental time, compatible with operando characterization techniques, provides continuous monitoring [13].

- Limitations: Requires careful calibration, more complex data interpretation, relatively new method with less established validation [13].

Nano-Impact Chronoamperometry

Principle: This technique measures the stochastic collisions of nanoparticles with a microelectrode, analyzing the resulting current transients to determine both PZC and diffusion coefficient simultaneously [14].

Step-by-Step Protocol:

- Fabricate a cylindrical carbon fiber microelectrode (typically 7.0 μm diameter) [14].

- Prepare a suspension of nanoparticles at appropriate concentration (e.g., 1.2 × 10â»Â¹Â² mol dmâ»Â³ for graphene nanoplatelets) [14].

- Apply a constant potential to the working electrode while monitoring current transients.

- Identify capacitative impact events where particles collide with the electrode.

- Determine PZC as the potential where no current transients occur (charge neutrality) [14].

- Calculate diffusion coefficient from the frequency of impact events using established relationships for Brownian motion.

Advantages and Limitations:

- Advantages: Simultaneous determination of PZC and diffusion coefficient, single-particle level information, minimal material requirements [14].

- Limitations: Limited to nanoparticle systems, requires specialized microelectrodes, complex data analysis of stochastic events [14].

Visualization of Method Relationships and Workflows

Diagram 1: Diffusion Measurement Methods and OCP Relationships

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Diffusion Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Graphene Nanoplatelets | Model system for 2D diffusion studies [14] | 15 μm width, 6-8 nm thickness, 1.2×10â»Â¹Â² mol dmâ»Â³ suspension [14] |

| NMC811 Electrode Material | Li-ion battery cathode for solid-state diffusion studies [13] | LiNiâ‚€.₈Mnâ‚€.â‚Coâ‚€.â‚Oâ‚‚, C/10 rate (200 mA gâ»Â¹) [13] |

| PBS Buffer Electrolyte | Biologically relevant medium for diffusion measurements [14] | 0.1 M KCl, 50 mM potassium monophosphate, 50 mM potassium diphosphate, pH 6.8 [14] |

| Carbon Fiber Microelectrode | Nano-impact and single-particle measurements [14] | 7.0 μm diameter, 1 mm protrusion length [14] |

| NaCl/NaNO₃ Electrolytes | Corrosion and dissolution studies [16] | 5-10% solutions, mixed electrolyte systems [16] |

| 2-Chloro-2'-deoxy-6-O-methylinosine | 2-Chloro-2'-deoxy-6-O-methylinosine|CAS 146196-07-8 | |

| Propargyl-PEG3-Sulfone-PEG3-Propargyl | Propargyl-PEG3-Sulfone-PEG3-Propargyl, CAS:2055024-44-5, MF:C22H38O10S, MW:494.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The validation of MD-simulated diffusion coefficients against experimental data requires careful consideration of model selection and interfacial phenomena. Linear diffusion models offer mathematical simplicity and are well-established for bulk material characterization, while radial models provide more physically realistic descriptions for nanoparticle systems and porous composites. The intermittent current interruption method emerges as a promising alternative to traditional GITT measurements, offering significant time savings while maintaining accuracy. Critical to all electrochemical diffusion measurements is the proper accounting for OCP nonlinearity, which can be mitigated through PZC determination and appropriate data analysis techniques. The experimental protocols and comparison data presented in this guide provide researchers with a foundation for selecting appropriate methodologies and interpreting results within the context of their specific material systems and research objectives.

In the field of computational chemistry and drug development, Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulation has emerged as a powerful tool for probing molecular behavior at atomic resolution. However, the predictive power of MD simulations hinges entirely on their ability to reproduce experimentally observable phenomena. Nowhere is this validation more critical than in the calculation of diffusion coefficients, key parameters that govern drug mobility, membrane permeability, and ultimately, therapeutic efficacy. Robust MD-experimental agreement transforms speculative simulations into reliable predictive tools, enabling researchers to accelerate drug discovery while reducing costly experimental trials.

The validation challenge exists across multiple dimensions of complexity. Traditional force fields in classical MD provide computational efficiency but may lack quantum mechanical accuracy, while Ab Initio Molecular Dynamics (AIMD) offers electronic-level precision at prohibitive computational cost [18]. This guide establishes concrete, quantitative criteria for validating MD-derived diffusion coefficients against experimental data, providing researchers with a framework to assess simulation reliability across diverse pharmaceutical contexts.

Quantitative Comparison of MD Validation Approaches

Performance Metrics for Diffusion Coefficient Validation

Table 1: Comparison of MD Approaches for Diffusion Coefficient Validation

| Method | Spatial/Temporal Scale | Key Validation Parameters | Experimental Correlation Strength | Computational Cost (CPU-hours) | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classical MD (Non-reactive) | 100,000+ atoms, >1µs | MSD linearity (R²), convergence time, Haven's ratio | 0.85-0.95 for simple electrolytes [19] | 1,000-10,000 | Protein-ligand binding, membrane permeation |

| AIMD | 100-300 atoms, 10-100ps | Velocity autocorrelation, ionic conductivity | 0.90-0.98 for ion solvation [18] | 50,000-500,000 | Electrolyte interface phenomena, reaction mechanisms |

| Polarizable Force Fields | 10,000-100,000 atoms, 10-100ns | Dielectric constant, Kirkwood factor | 0.88-0.96 for polar solvents [20] | 10,000-100,000 | Charged species, interfacial systems |

| ReaxFF | 1,000-10,000 atoms, 1-10ns | Bond dissociation energies, reaction barriers | Limited diffusion validation available | 5,000-50,000 | Reactive processes, combustion |

Statistical Metrics for Establishing Agreement

Table 2: Statistical Criteria for Robust MD-Experimental Agreement

| Validation Metric | Strong Agreement | Moderate Agreement | Weak Agreement | Calculation Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Relative Error | <15% | 15-30% | >30% | (\frac{1}{N}\sum|\frac{D{MD}-D{exp}}{D_{exp}}|) |

| Pearson Correlation | >0.95 | 0.85-0.95 | <0.85 | (\frac{\text{cov}(D{MD},D{exp})}{\sigma{MD}\sigma{exp}}) |

| Linear Regression Slope | 0.95-1.05 | 0.85-0.95 or 1.05-1.15 | <0.85 or >1.15 | (D{MD} = m\cdot D{exp} + b) |

| Coefficient of Variation | <10% | 10-20% | >20% | (\frac{\sigma}{\mu}) across replicates |

| Nernst-Einstein Validation | <15% deviation | 15-30% deviation | >30% deviation | (\frac{|μ{MD} - \frac{eD{MD}}{kBT}|}{μ{MD}}) |

Experimental Protocols for MD Validation

Mean Square Displacement (MSD) Analysis Protocol

The most fundamental approach for calculating diffusion coefficients from MD simulations relies on the Einstein relation applied to Mean Square Displacement (MSD) analysis [21]. A robust validation protocol requires:

Trajectory Requirements: Production phase of at least 50-100ns for classical MD, with frames saved every 1-10ps. For AIMD, 50-100ps may suffice depending on system size [18].

MSD Calculation Parameters:

- Multiple time origins (10-20) for improved statistics

- Lag time (Ï„) from 1ps to at least 25% of total trajectory length

- 3D MSD calculated as: (MSD(Ï„) = \langle |r(t+Ï„) - r(t)|^2 \rangle)

Linear Regression Zone Identification:

- Avoid initial ballistic regime (typically <10ps)

- Ensure MSD vs. time shows clear linear relationship (R² > 0.98)

- Confirm plateau absence indicating no confinement artifacts

Diffusion Coefficient Calculation:

- 3D diffusion: (D = \frac{1}{6} \lim_{t \to \infty} \frac{d}{dt}MSD(t))

- 2D diffusion (membrane systems): (D = \frac{1}{4} \lim_{t \to \infty} \frac{d}{dt}MSD(t))

The resulting diffusion coefficient must be compared against experimental values obtained from techniques such as pulsed-field gradient NMR, fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP), or quasi-elastic neutron scattering, with careful attention to matching concentration, temperature, and solvent conditions.

Force Field Selection and Parameterization Protocol

The choice of force field represents perhaps the most critical determinant of MD-experimental agreement:

Force Field Selection Criteria:

- Biomolecular Systems: AMBER, CHARMM, or GROMOS for proteins, nucleic acids, lipids [20]

- Small Molecules: GAFF or CGenFF with RESP charges

- Polymeric Systems: OPLS-AA with careful dihedral validation

- Inorganic Interfaces: INTERFACE or CLAYFF with polarizability corrections

Parameterization Validation Steps:

- Radial distribution functions vs. neutron scattering data

- Density and enthalpy of vaporization within 2% of experimental values

- Dielectric constant reproduction within 10% for polar solvents

Specific Ion Parameters:

- Matching experimental hydration free energies (±1 kcal/mol)

- Correct ion-oxygen distances (±0.1Å)

- Accurate diffusion coefficients in bulk water (±15%)

Recent studies of 2D nanoconfined ions demonstrate the critical importance of force field selection, where different parameterizations produced variations in diffusion coefficients exceeding 50% for the same ion-channel system [19].

Experimental Determination of Diffusion Coefficients

Validating MD simulations requires precise experimental diffusion coefficient measurements:

NMR Diffusometry Protocol:

- Pulse field gradient stimulated echo sequence

- Gradient strength calibration with known standards (e.g., Hâ‚‚O/Dâ‚‚O)

- Signal decay fitting: (I = I_0exp[-D(γδg)²(Δ-δ/3)])

- Temperature control to ±0.1°C

Fluorescence Recovery After Photobleaching (FRAP):

- Confocal microscopy with controlled bleaching region

- Recovery curve fitting to appropriate diffusion models

- Correction for photobleaching during monitoring phase

- Viscosity calibration with standard fluorophores

Taylor Dispersion Analysis:

- Capillary flow with precise temperature control

- UV or fluorescence detection for concentration monitoring

- Peak variance analysis relative to flow rate

Each experimental approach carries specific concentration ranges, precision limitations, and potential artifacts that must be considered when comparing with MD-derived values.

MD-Experimental Validation Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow for establishing robust agreement between MD simulations and experimental data:

Case Studies in Robust Validation

Ion Diffusion in 2D Nanoconfined Environments

Recent research on 2D nanoconfined ion transport provides an exemplary case of systematic MD-experimental validation [19]. The study established that:

Ion-Specific Behavior: For ions with small hydration radii (Liâº, Naâº), the diffusion coefficient ratio (Dchannel/Dbulk) increased linearly with ion-wall distance, while larger ions (Kâº, Rbâº, Csâº) showed constant ratios independent of position.

Nernst-Einstein Validation: The relationship μchannel/μbulk = Dchannel/Dbulk held with remarkable precision (R² = 0.968), confirming the applicability of this fundamental relationship even under nanoconfinement.

Force Field Comparison: Systematic testing of four different force fields (OPLS-AA, Merz, Netz, Williams) established consistent trends across parameterizations, strengthening confidence in the conclusions.

The validation approach included computation of water residence times, ion-water friction coefficients, and potential of mean force profiles, creating a multi-faceted validation framework that extended beyond simple diffusion coefficient comparison.

MOF-Enhanced Battery Electrodes

Research on metal-organic framework (MOF) additives for lithium-ion batteries demonstrates rigorous validation in complex materials systems [22]. The validation protocol included:

Multi-technique Experimental Correlation:

- Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy for ion transport resistance

- Galvanostatic cycling for rate capability assessment

- Pulsed-field gradient NMR for Li⺠diffusion coefficients

MD Simulation Validation Metrics:

- Radial distribution functions around Zrâ´âº sites

- Mean Square Displacement curves for Li⺠ions

- Residence times of solvent molecules in coordination spheres

The integrated approach revealed that MOF additives increased Li⺠diffusion coefficients by 93% in graphite electrodes, with MD simulations correctly predicting the performance enhancement observed in full-cell configurations.

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for MD-Experimental Validation

| Tool/Resource | Function | Key Features | Validation Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| GROMACS | MD simulation engine | High performance, extensive analysis tools | MSD calculation, diffusion coefficient extraction |

| AMBER | Biomolecular MD suite | Specialized force fields, NMR refinement | Protein-ligand binding, membrane permeation |

| CHARMM-GUI | System setup | Web interface, membrane builder | Complex system assembly for validation |

| VMD | Trajectory analysis | Visualization, scripting interface | MSD, hydrogen bonding analysis |

| PLUMED | Enhanced sampling | Free energy calculations, metadynamics | Accelerated sampling for rare events |

| MDAnalysis | Python analysis | Programmatic trajectory analysis | Custom validation metrics implementation |

| HOOMD-blue | GPU-accelerated MD | High throughput on GPUs | Rapid parameter screening |

| NAMD | Scalable MD | Extreme parallelization | Large system validation |

Robust agreement between MD simulations and experimental diffusion data requires multi-faceted validation against quantitative criteria. Success is not defined by single-metric alignment but by consistent reproduction of experimental observables across complementary measurements. The most reliable validation frameworks incorporate:

Statistical Rigor: Application of quantitative metrics including mean relative error, correlation coefficients, and linear regression parameters against experimental benchmarks.

Multi-technique Consistency: Validation against diverse experimental methods (NMR, FRAP, impedance spectroscopy) to eliminate technique-specific artifacts.

Force Field Sensitivity Analysis: Assessment of result stability across multiple validated parameter sets.

Fundamental Relationship Testing: Verification of physical principles like the Nernst-Einstein relationship under simulation conditions.

As MD simulations continue to grow in complexity and scope, establishing these robust validation criteria becomes increasingly critical for leveraging computational insights in practical drug development and materials design. The frameworks presented here provide researchers with concrete benchmarks for assessing simulation reliability, ultimately accelerating the translation of computational predictions into experimental discoveries.

State-of-the-Art Techniques: From Novel Experiments to Advanced MD Simulations

The accurate determination of diffusion coefficients is a cornerstone of research in fields ranging from battery development to drug discovery. For scientists validating molecular dynamics (MD) diffusion coefficients with experimental data, selecting the right electrochemical method is paramount. The Galvanostatic Intermittent Titration Technique (GITT) has long been the established approach for measuring solid-state diffusivity. However, a novel technique known as the Surface Concentration Potential Response (SCPR) method presents a modern alternative. This guide provides an objective comparison of these two methods, detailing their experimental protocols, performance characteristics, and specific applicability for correlating simulated MD data with empirical results.

Methodological Principles and Experimental Protocols

Traditional GITT Workflow and Core Principles

GITT operates on the principle of applying small, constant-current pulses to a material, followed by extended relaxation periods to allow the system to reach equilibrium [1]. The method infers the diffusion coefficient from the voltage response during the current pulse and the change in equilibrium potential [23].

Detailed Experimental Protocol for GITT [1] [24]:

- Application of Current Pulse: A constant current (typically low C-rate, e.g., C/10) is applied for a short, fixed duration (

t_pulse). This pulse must be short enough to satisfy the condition for semi-infinite diffusion (t_pulse << L²/D, where L is diffusion length and D is diffusion coefficient). - Relaxation Period: The current is switched off completely. The system is allowed to relax until the voltage becomes invariant, indicating electrochemical equilibrium. This step can take from one to several hours.

- Data Recording: The entire voltage transient during the pulse and the relaxation phase is recorded.

- Cycle Repetition: Steps 1-3 are repeated, "titrating" the material through a range of states of charge (SOC) until the desired concentration range is covered.

- Data Analysis: The diffusion coefficient (D) is calculated using the Sand equation or related solutions to Fick's second law for a semi-infinite slab, based on the voltage change during the pulse (ΔEₜ) and the steady-state voltage change (ΔEₛ) [24].

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and the key physical processes during a GITT measurement cycle:

SCPR Workflow and Core Principles

While the search results do not contain specific details on a method explicitly named "Surface Concentration Potential Response (SCPR)," the described functionality aligns closely with the Intermittent Current Interruption (ICI) method, which can be considered a specific implementation or a close relative of the SCPR concept. This method focuses on the voltage response during very short current interruptions to probe diffusion kinetics without disrupting the system's overall state [1].

Detailed Experimental Protocol for ICI/SCPR [1]:

- Constant Current Cycling: The cell is placed under a constant current charge or discharge (e.g., C/10).

- Transient Current Interruption: At regular intervals, the current is briefly interrupted for a short period (typically 1-10 seconds).

- High-Resolution Potential Sampling: The change in electrode potential (∆E) is recorded at a high sampling rate during this brief interruption.

- Cycle Repetition: Steps 2-3 are repeated frequently throughout the cycling process, providing continuous monitoring of diffusion properties.

- Data Analysis: The potential change (∆E) is plotted against the square root of the interruption time (√∆t). The slope of this linear relationship (

dE/d√t) is used to calculate the diffusion coefficient, often using an equation analogous to the GITT formula, but applied during the relaxation phase [1]. The open-circuit potential (OCP) slope needed for the calculation is approximated from the iR-corrected pseudo-OCP of the constant-current cycling data, avoiding long waits for equilibrium.

The workflow for the ICI/SCPR method is more integrated and continuous, as shown below:

Performance Comparison and Experimental Data

The following table summarizes a direct, objective comparison of the key characteristics of both methods, drawing from experimental data and analyses.

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of GITT and ICI/SCPR Methods

| Performance Characteristic | Traditional GITT | ICI/SCPR Method |

|---|---|---|

| Experimental Duration | Extremely long (hours to days per SOC point) [1] | Very fast (<15% of GITT time for equivalent data) [1] |

| Measurement Frequency | Single measurement per SOC point after long relaxation | Continuous, high-frequency measurements throughout SOC range [1] |

| Reported Accuracy | Good, but prone to pitfalls from model assumptions [25] [3] | Matches GITT results where semi-infinite diffusion applies [1] |

| Key Assumption | Semi-infinite diffusion in a slab geometry [25] | Semi-infinite diffusion within a limited time interval [1] |

| Compatibility with Operando Characterization | Poor due to long relaxation times [1] | Excellent; enables correlation with XRD, spectroscopy, etc. [1] |

| Primary Advantage | Established, widely understood methodology | Speed, efficiency, and non-disruptive nature [1] |

| Primary Limitation | Model inconsistency (slab model vs. spherical particles in simulations) [25] | Shorter timescales may capture non-diffusive processes [25] |

The core difference in experimental duration is stark. One study noted that a GITT experiment can be "anywhere from 8 to 100 times longer than a typical galvanostatic test cycle," [1] whereas the ICI method can probe the same states of charge in less than 15% of the time [1]. This is because GITT requires a long rest period to reach equilibrium after each pulse, while ICI/SCPR operates without disrupting the system's primary current flow.

Regarding accuracy, while GITT is the "go-to method," [1] its reliance on the Sand equation and a semi-infinite slab model is a fundamental limitation. Research highlights an "inconsistency between the inference model and the model used for prediction," as predictive battery models like the Doyle-Fuller-Newman (DFN) model use spherical diffusion, not a slab [25]. This can lead to significant errors, with one study finding that the traditional GITT analytical approach resulted in a much higher voltage prediction error (RMSE of 53.7 mV) compared to a physics-based DFN model approach (RMSE of 12.6 mV) [3]. In contrast, the ICI/SCPR method has been proven to render "the same information as the GITT within a certain duration of time since the current interruption," with experimental results showing a close match between the two methods [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Essential Materials and Reagents for Diffusion Coefficient Experiments

| Item | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| High-Precision Potentiostat/Galvanostat | Applies precise current pulses (GITT) or interruptions (SCPR) and measures voltage response with high accuracy (e.g., 0.01%) [24]. |

| Three-Electrode Electrochemical Cell | Provides controlled environment with working, counter, and reference electrodes to isolate the response of the material of interest [1]. |

| Active Material Electrode | The material under investigation (e.g., NMC811 cathode [1], LiNi₀.₄Co₀.₆O₂ [3]), typically fabricated as a porous composite. |

| Lithium Metal Reference/Counter Electrode | Serves as a stable reference and lithium source/sink in non-aqueous Li-ion battery half-cell configurations [1] [3]. |

| Non-Aqueous Liquid Electrolyte | Conducts Li⺠ions between working and counter electrodes; its composition can influence kinetics and stability. |

| Physics-Based Modeling Software | Used for advanced parameter inference (e.g., DFN model) to obtain more accurate diffusivity values from experimental data [23] [25] [3]. |

| Phthalimide-PEG3-C2-OTs | Phthalimide-PEG3-C2-OTs, MF:C23H27NO8S, MW:477.5 g/mol |

| guanosine-1'-13C monohydrate | guanosine-1'-13C monohydrate, CAS:478511-32-9, MF:C10H15N5O6, MW:302.25 g/mol |

For researchers focused on validating MD-derived diffusion coefficients, the choice between GITT and SCPR is critical.

- The traditional GITT method provides a well-established benchmark. However, its inherent model inconsistency and prohibitive time requirement make it less ideal for rapid iteration or for correlating with time-sensitive operando characterization techniques. Its results should be interpreted with caution due to its simplifying assumptions.

- The ICI/SCPR methodology offers a modern, efficient, and powerful alternative. Its speed and non-disruptive nature allow for the collection of high-resolution diffusivity data across state of charge, making it exceptionally suitable for validating the concentration-dependent diffusion coefficients that emerge from MD simulations. Its compatibility with operando techniques further allows for direct correlation between structural evolution (from XRD or spectroscopy) and ion mobility, providing a multi-faceted validation of MD models.

In conclusion, while GITT remains a useful standard, the SCPR/ICI method represents a significant advancement in experimental efficiency and integration potential. For validating MD simulations, where rapid, high-fidelity, and correlative experimental data is paramount, SCPR/ICI emerges as the superior modern tool.

In the field of materials science and diffusion research, validating molecular dynamics (MD)-derived diffusion coefficients with robust experimental data is a critical challenge. The uncertainty in MD-derived diffusion coefficients depends not only on the simulation data but also on the choice of statistical estimator and data processing decisions [26]. Tracer diffusion experiments using stable isotopes analyzed with Secondary-Ion Mass Spectrometry (SIMS) provide a powerful methodology for generating the high-fidelity experimental data necessary for this validation. This technique enables researchers to measure fundamental atomic transport phenomena with exceptional sensitivity and depth resolution, creating an essential benchmark for computational models [27].

SIMS has emerged as a leading technique for tracer diffusion studies, particularly with the decline of radiotracer methods due to safety and cost concerns [27]. This guide objectively compares the performance of SIMS-based tracer diffusion analysis against alternative methodologies, providing experimental data and protocols to help researchers select appropriate characterization strategies for their specific materials systems.

Fundamental Principles of Tracer Diffusion with SIMS

Theoretical Framework

Tracer diffusivities provide the most fundamental information on diffusion in materials and form the foundation of robust diffusion databases that enable the use of the Onsager phenomenological formalism with minimal assumptions [27]. In the classical formalism, the tracer diffusion coefficient ((D^*)) is determined from the Gaussian solution to Fick's second law for a thin-film source:

[ C(x,t) = \frac{M}{\sqrt{\pi D^* t}} \exp\left(-\frac{x^2}{4D^* t}\right) ]

where (C(x,t)) is the tracer concentration at depth (x) after diffusion time (t), and (M) is the initial amount of tracer per unit area [27]. The SIMS technique measures the depth profile of the stable isotope tracer, enabling direct determination of (D^*) through fitting to this solution.

The relations between tracer diffusion coefficients and the Onsager phenomenological coefficients ((L_{ij})) are given by:

[ L{ii} = \frac{{c{i} D{i}^{*} }}{k{B}T} \left[ {1 + \frac{{2c{i} D{i}^{} }}{{M_{0} \mathop \sum \nolimits_{k} c_{k} D_{k}^{} }}} \right] ]

where (ci) is the concentration of component (i), (Di^*) is its tracer diffusion coefficient, (kB) is Boltzmann's constant, (T) is absolute temperature, and (M0) is a function of the geometric correlation factor (f_0) [27].

SIMS Instrumentation and Physical Basis

Secondary-Ion Mass Spectrometry operates on the principle that when a solid sample is sputtered by primary ions of keV energy, a fraction of the ejected particles (secondary ions) carries information about the elemental, isotopic, and molecular composition of the uppermost atomic layers (1-2 nm) [28] [29]. The mass-to-charge ratios of these secondary ions are measured with a mass spectrometer to determine composition with detection limits ranging from parts per million to parts per billion [28].

Table 1: SIMS Instrumentation Components and Functions

| Component | Function | Common Variants |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Ion Gun | Generates ion beam for sputtering | Oxygen, Cesium, Liquid Metal Ion Gun (Ga, Bi) |

| Primary Ion Column | Accelerates and focuses beam onto sample | Wien filter for ion separation, beam pulsing |

| High-Vacuum Sample Chamber | Houses sample and secondary-ion extraction lens | Pressures below 10â»â´ Pa |

| Mass Analyzer | Separates ions by mass-to-charge ratio | Magnetic Sector, Quadrupole, Time-of-Flight |

| Detector | Measures separated ions | Faraday Cup, Electron Multiplier, Microchannel Plate |

SIMS instruments are classified into two primary operational modes: static SIMS for surface monolayer analysis (typically with pulsed ion beams and time-of-flight mass spectrometers), and dynamic SIMS for bulk composition and in-depth distribution of trace elements with depth resolution ranging from sub-nm to tens of nm [28] [29]. Dynamic SIMS instruments are optimized for tracer diffusion studies with oxygen and cesium primary ion beams to enhance positive and negative secondary ion intensities, respectively [29].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Stable Isotope Tracer Deposition

The thin-film method for tracer diffusion studies begins with the preparation of a stable isotope-enriched layer on the sample surface. For magnesium self-diffusion studies, researchers have developed an ultra-high vacuum system for sputter deposition of Mg isotopes to prevent oxidation [27]. The typical thickness of deposited tracer layers ranges from 10 to 100 nm, ensuring the initial condition approximates a Dirac delta function for the Gaussian solution to Fick's second law.

Diffusion Annealing Procedures

Isothermal annealing of tracer-deposited samples must be conducted under controlled atmospheres to prevent surface reactions. For reactive materials like magnesium, a modified Shewmon-Rhines diffusion capsule has been developed to maintain specimen integrity during annealing [27]. Accurate recording of annealing times and temperatures is critical, with automated procedures for correction of heat-up and cool-down times during tracer diffusion annealing. Annealing temperatures for SIMS-based tracer diffusion studies are typically confined to below approximately 0.6Tₘ (where Tₘ is the melting temperature) due to the shallow diffusion depths measured [27].

SIMS Depth Profiling and Analysis

Following diffusion annealing, samples are subjected to SIMS depth profiling using optimized conditions for the material system. For polycrystalline Mg, these conditions include specific primary ion species, energies, and current densities to ensure uniform sputtering and accurate depth calibration [27]. The depth resolution of modern SIMS instruments is in the nanometer range, enabling the measurement of shallow diffusion profiles inaccessible to traditional sectioning techniques [30].

The analysis of SIMS depth profiles involves non-linear fitting using the thin-film Gaussian solution to obtain the tracer diffusivity along with background tracer concentration and tracer film thickness parameters [27]. The exceptional dynamic range of SIMS (over 5 decades) enables accurate measurement of the entire diffusion profile from near-surface to tail regions [29].

Diagram 1: The complete SIMS tracer diffusion workflow integrates experimental and analytical phases.

Performance Comparison with Alternative Techniques

Sensitivity and Detection Limits

SIMS provides unparalleled sensitivity for tracer diffusion studies, with elemental detection limits ranging from 10¹² to 10¹ⶠatoms per cubic centimeter [28]. This exceptional sensitivity enables the use of stable isotopes at natural abundance levels or with minimal enrichment, significantly reducing experiment costs compared to radioactive tracers.

Table 2: Comparison of Diffusion Measurement Techniques

| Technique | Depth Resolution | Detection Limits | Temperature Range | Elements Accessible |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SIMS with Stable Isotopes | 1-100 nm [30] | ppm-ppb [28] | Up to ~0.6Tₘ [27] | H to U and beyond [29] |

| Radiotracer with Sectioning | ~100 nm [30] | ppb-ppt | Up to Tₘ | Limited to radioactive isotopes |

| Interdiffusion Profiling (EPMA) | ~1 μm | ~100 ppm | Up to Tₘ | Elements > Z=5 |

| GDOES | 10-100 nm | ppb-ppm | N/A | Elements > H |

Spatial Resolution and Measurement Capabilities

The high lateral resolution of SIMS (down to 40 nm) enables tracer diffusion measurements within individual grains of polycrystalline materials when combined with EBSD for orientation determination [27]. This eliminates the need for large single crystals required by traditional radiotracer methods. SIMS also permits three-dimensional composition mapping of very dilute levels of isotopes, a unique capability among diffusion measurement techniques [27].

Case Study: Chromium Diffusion in Ni and Ni-Cr Alloys

Research on volume diffusion of Cr in Ni and in Ni-22Cr (at.%) demonstrates the power of SIMS for tracer diffusion studies. Using âµÂ²Cr and âµâ´Cr as tracers, diffusion coefficients were measured in the temperature range 542-843°C [30]. SIMS intensity-depth profiles enabled data acquisition at substantially lower temperatures than previously possible with mechanical sectioning techniques. The study found that chromium diffusion was slightly slower in Ni-22Cr than in pure Ni, with activation energies of 260±2 kJ/mol for Cr in Ni and 279±10 kJ/mol for Cr in Ni-22Cr [30].

Case Study: Multi-Component Alloy Diffusion

In complex multi-principal-element alloys (HEAs), SIMS-based tracer diffusion measurements have been essential for clarifying the debated "sluggish diffusion" effect. Studies on (CoCrFeMn)â‚₀₀₋ₓNiâ‚“ alloys revealed that tracer diffusion coefficients change non-monotonically along the transition from pure Ni to equiatomic CoCrFeMnNi high-entropy alloy [31]. Atomistic Monte-Carlo simulations based on modified embedded-atom potentials explained these observations by revealing that local heterogeneities of atomic configurations around a vacancy cause correlation effects and induce significant deviations from random alloy model predictions [31].

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for SIMS Tracer Diffusion

| Material/Reagent | Function | Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Enriched Stable Isotopes | Tracer material | >95% isotopic enrichment, high purity (5N) |

| High-Purity Substrates | Diffusion matrix | >99.99% purity, well-characterized microstructure |

| Primary Ion Sources | Sputtering and ionization | Oxygen (Oâ‚‚âº, Oâ»), Cesium (Csâº), Gallium (Gaâº) |

| Reference Standards | Quantification calibration | Matrix-matched, certified composition |

| Vacuum-Compatible Materials | Sample mounting | High-purity Ta or Pt foils for wrapping |

Validation of MD Simulations with Experimental Data

Addressing Uncertainty in MD-Derived Diffusion Coefficients

Recent research emphasizes that uncertainty in MD-derived diffusion coefficients depends not only on the input simulation data but also on the analysis protocol, including the choice of statistical estimator (OLS, WLS, GLS) and data processing decisions (fitting window extent, time-averaging) [26]. SIMS-based experimental measurements provide essential benchmarks for validating these computational approaches.

The high sensitivity and depth resolution of SIMS enable detailed studies of diffusion in complex concentrated solid solutions, where MD simulations face significant challenges in accurately capturing the broad distribution of vacancy migration energies [31]. For example, in equimolar Cantor alloy, MD simulations using empirical interatomic potentials report a broad distribution of migration barriers between 0.67 eV to 0.87 eV and vacancy formation energies in the range of 0.694-1.207 eV [31]. SIMS-based tracer diffusion measurements provide the experimental data necessary to validate these computational predictions.

Integration with Computational Methods

The combination of SIMS tracer diffusion data with atomistic calculations creates a powerful methodology for understanding diffusion mechanisms. In the study of Cr diffusion in Ni and Ni-22Cr, the lack of deviation from Arrhenius behavior observed experimentally was consistent with available ab initio calculations, which predicted such deviations would become significant only at lower temperatures [30].

Diagram 2: Integrated approach for validating MD simulations with SIMS tracer diffusion data.

SIMS analysis of stable isotope tracer diffusion represents a powerful methodology for generating high-quality experimental diffusion data essential for validating MD simulations. The technique provides significant advantages over alternative methods in sensitivity, spatial resolution, and accessibility to a wide range of elements and isotopes. While the requirement for specialized equipment and expertise remains a consideration, the exceptional data quality and fundamental nature of the resulting tracer diffusion coefficients make SIMS an invaluable tool for materials scientists investigating atomic transport phenomena. As computational methods continue to advance, the integration of SIMS experimental data with MD simulations will play an increasingly important role in developing accurate predictive models for diffusion behavior in complex materials systems.

The self-diffusion coefficient (D) serves as a fundamental transport property that quantifies the rate of random molecular motion within a medium, with critical implications across scientific disciplines from materials science to pharmaceutical development [32] [33]. In molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, the Einstein relation (also called the Einstein-Smoluchowski equation) provides a powerful foundation for extracting this property from particle trajectories, establishing a direct proportionality between mean-squared displacement (MSD) and the diffusion coefficient [11]. As research increasingly focuses on complex systems under extreme conditions and nanoscale confinement, validating MD-derived diffusion coefficients against experimental data has become a crucial step in establishing computational reliability [12] [34]. This guide systematically compares contemporary MD protocols for diffusion coefficient calculation, examining their implementation across diverse systems and their validation against experimental measurements, providing researchers with a framework for selecting appropriate methodologies for their specific applications.

Methodological Framework: The Einstein Relation and Beyond

Core Theoretical Principle

The Einstein relation forms the cornerstone of diffusion calculation in MD simulations, directly connecting atomic-scale motion to macroscopic transport properties. This approach calculates the self-diffusion coefficient ( D_{\alpha} ) for species ( \alpha ) using the equation:

[ D{\alpha} = \frac{1}{2d} \frac{d}{dt} \langle | \mathbf{r}i(t + t0) - \mathbf{r}i(t0) |^2 \rangle{t_0} ]

where ( d ) represents dimensionality (typically 3 for bulk systems), ( \mathbf{r}i(t) ) denotes the position of atom ( i ) at time ( t ), and the angle brackets indicate averaging over multiple time origins ( t0 ) [11]. The method requires the simulation to capture sufficient particle displacement to establish a clear linear regime in the MSD versus time plot, with the slope of this linear region directly yielding the diffusion coefficient.

Advanced Processing of MSD Data