Beyond the Peak: A Comprehensive Guide to What Radial Distribution Function (RDF) Can Analyze in Materials Science and Drug Development

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a complete guide to the analytical power of the Radial Distribution Function (RDF).

Beyond the Peak: A Comprehensive Guide to What Radial Distribution Function (RDF) Can Analyze in Materials Science and Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a complete guide to the analytical power of the Radial Distribution Function (RDF). It covers foundational principles, from defining RDF as a measure of atomic and molecular spatial probability to its interpretation in gases, liquids, and solids. The piece delves into advanced computational methodologies, including spectral Monte Carlo techniques and Kirkwood-Buff theory, for applications ranging from solvation structure analysis to coarse-grained force-field calibration. It also addresses critical challenges like spatial uncertainty in atom probe tomography data and offers strategies for validation against experimental results, positioning RDF as an indispensable tool for unraveling atomic-scale structure-property relationships.

The RDF Blueprint: Decoding Atomic and Molecular Order in Matter

The Radial Distribution Function (RDF), denoted as g(r), is a cornerstone of statistical mechanics and materials characterization, providing a quantitative description of the probability of finding a particle at a distance r from a reference particle relative to what would be expected from a completely random (ideal gas) distribution [1] [2]. This function serves as a powerful bridge between microscopic atomic arrangements and macroscopic observable properties, making it indispensable for researching disordered systems that lack long-range order, such as liquids, glasses, and amorphous solids [3]. Unlike diffraction techniques that are most sensitive to crystalline materials with long-range periodic order, the RDF is an ideal metric for characterizing local structure, making it particularly valuable for studying complex nanomaterials, biological molecules in solution, and the development of novel pharmaceutical compounds [4] [3].

Within the context of a broader thesis, the RDF provides an essential toolkit for answering fundamental research questions about atomic-scale organization in systems where traditional crystallographic approaches fall short. It enables researchers to quantify short-range order in high-entropy alloys [5], determine ion coordination environments in battery materials [4], validate molecular dynamics simulations against experimental data [6], and derive thermodynamic properties through the Kirkwood-Buff solution theory [1] [7]. This technical guide explores the fundamental definitions, computational methodologies, and practical applications of RDF analysis across diverse scientific domains.

Mathematical Foundation and Physical Interpretation

Formal Statistical Mechanical Definition

In the canonical ensemble (constant NVT), the RDF finds its rigorous foundation in statistical mechanics. For a system of N particles in volume V at temperature T, the normalized pair distribution function is defined as [1] [6]:

g(râ‚, râ‚‚) = [ Ïâ½Â²â¾(râ‚, râ‚‚) ] / [ Ïâ½Â¹â¾(râ‚) Ïâ½Â¹â¾(râ‚‚) ]

where Ïâ½Â¹â¾(r) is the one-particle density function, and Ïâ½Â²â¾(râ‚, râ‚‚) is the two-particle density function, which is proportional to the probability of finding a specific pair of particles at positions râ‚ and râ‚‚ [1]. For a homogeneous, isotropic system of spherical particles, this simplifies to a function that depends only on the scalar separation r = |râ‚‚ - râ‚|, yielding the standard radial distribution function g(r) [6].

The computational expression for g(r) in molecular simulations is given by [8]:

$$ g{AB}(r) = \frac{1}{\langle\rhoB\rangle{local}} \frac{1}{NA} \sum{i \in A}^{NA} \sum{j \in B}^{NB} \frac{\delta(r_{ij} - r)}{4\pi r^2} $$

where ⟨ÏB⟩{local} represents the average particle density of type B, and the double summation counts pairs of particles between groups A and B separated by distance r [8].

Probability and Local Density Interpretation

Physically, the RDF can be understood through two complementary interpretations. The probability interpretation defines g(r) in terms of the probability dn(r) of finding a particle in a spherical shell of thickness dr at distance r from a reference particle [2] [9]:

dn(r) = Ïg(r)4Ï€r²dr

where Ï is the bulk number density [9]. This relationship makes the RDF computationally straightforward to determine by calculating distances between all particle pairs, binning them into a histogram, and normalizing with respect to an ideal gas [1].

The local density interpretation defines g(r) as the ratio of the local density at distance r from a reference particle to the bulk density [7]:

g(r) = Ï(r)/Ï

where Ï(r) is the local density at distance r, and Ï is the bulk density [2] [7]. This interpretation reveals that g(r) = 1 indicates random distribution (local density equals bulk density), g(r) > 1 indicates enhanced probability (as found in coordination shells), and g(r) < 1 indicates depleted probability (as found in excluded regions between shells) [2].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of RDFs for Different States of Matter

| State of Matter | First Peak Position | First Peak Sharpness | Long-Range Behavior | Coordination Number |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Solids | Discrete values of σ, √2σ, √3σ | Very sharp, well-defined | Persistent oscillations | Defined by crystal structure |

| Liquids | ~σ | Sharpest peak, then decaying | Rapid decay to g(r)=1 | ~12 for simple liquids, 4-5 for H-bonding |

| Gases | >σ (if present) | Broad, poorly defined | Rapid decay to g(r)=1 | Not well-defined |

RDFs Across Different States of Matter

Characteristic RDF Signatures

The radial distribution function exhibits distinct characteristics for different states of matter, providing a fingerprint of material organization. Crystalline solids display discrete, sharp peaks at specific distances corresponding to their lattice geometry (e.g., at σ, √2σ, √3σ for simple cubic lattices), with these oscillations persisting to long range due to their regular, periodic structures [2]. The RDF of gases is relatively simple, with g(r) = 0 for r < σ (due to hard-sphere repulsion), a single broad coordination sphere where g(r) > 1 for σ < r < 2σ, and rapid decay to g(r) = 1 beyond this distance, reflecting the absence of long-range correlations in dilute systems [2].

Liquid systems represent a particularly important application of RDF analysis. They exhibit a characteristic pattern with g(r) = 0 at very short distances (due to repulsive forces), a sharp first peak at approximately the molecular diameter (σ) corresponding to the first coordination shell, followed by diminishing oscillations that eventually decay to the bulk density (g(r) = 1) at large distances [2]. This pattern reflects the short-range order but long-range disorder that defines the liquid state, with the RDF providing crucial information about packing efficiency and intermolecular interactions.

Coordination Number Calculation

A fundamental derivative of the RDF is the coordination number, which quantifies how many neighbors a particle has within a specific distance. The average number of particles of type j around a central particle of type i within a distance r' is obtained by integrating the RDF [2] [3]:

n(r') = 4Ï€Ï∫₀ʳ' g(r)r²dr

In practice, the coordination number for a specific coordination shell is calculated by integrating up to the first minimum after a peak in the RDF [2] [3]. For simple liquids composed of spherical particles that can be approximated as hard spheres, the coordination number is typically approximately 12, reflecting the most efficient way to fill space [2]. However, liquids with specific directional interactions like hydrogen bonding (e.g., water) exhibit much lower coordination numbers (typically 4-5 in the first sphere) due to the constraints of maximizing these specific interactions, resulting in more energetic but less efficient packing [2].

Experimental and Computational Determination

Experimental Measurement Techniques

The radial distribution function can be determined experimentally through several scattering techniques, with the common principle being that the RDF can be derived from the Fourier transform of the structure factor S(Q) obtained from scattering experiments [1] [3]. X-ray diffraction is commonly used for studying atomic arrangements in materials, while neutron scattering is particularly valuable for studying light elements and magnetic materials [4]. Electron diffraction can also provide RDFs for nanoscale regions [3].

A prominent application of experimental RDF analysis appears in the characterization of lignin-based carbon composites (LBCCs) for sustainable energy storage devices. In this context, RDFs derived from synchrotron X-ray and neutron scattering have been used to develop quantitative processing-structure-property-performance relationships, revealing that carbonization of lignin produces a heterogeneous two-phase composite of nanoscale graphitic domains embedded in a matrix of randomly oriented amorphous graphene fragments [4]. The HDRDF (Hierarchical Decomposition of the Radial Distribution Function) modeling method has been successfully applied to determine crystalline and amorphous particle shapes and sizes, component volume fractions, and densities for LBCCs synthesized from various lignin feedstocks [4].

Computational Determination Methods

In computational modeling, RDFs are directly calculated from atomic positions by constructing a histogram of pair distances. The process involves [3]:

- Choosing a central atom as reference

- For each value of r, constructing a spherical shell of radius r and width dr

- Counting the number of atoms within each spherical shell

- Normalizing by the bulk density and shell volume

- Repeating and averaging over all atoms and multiple time steps

For molecular dynamics simulations, tools like gmx rdf in GROMACS implement this algorithm by dividing the system into spherical slices from r to r+dr and creating histograms rather than dealing directly with delta functions [8]. The analysis program rdfshg provides another computational approach with various parameters for controlling the RDF calculation, including rcut (the maximum distance to compute g(r)), nbin (number of bins for histogram resolution), and options for handling periodic boundary conditions [3].

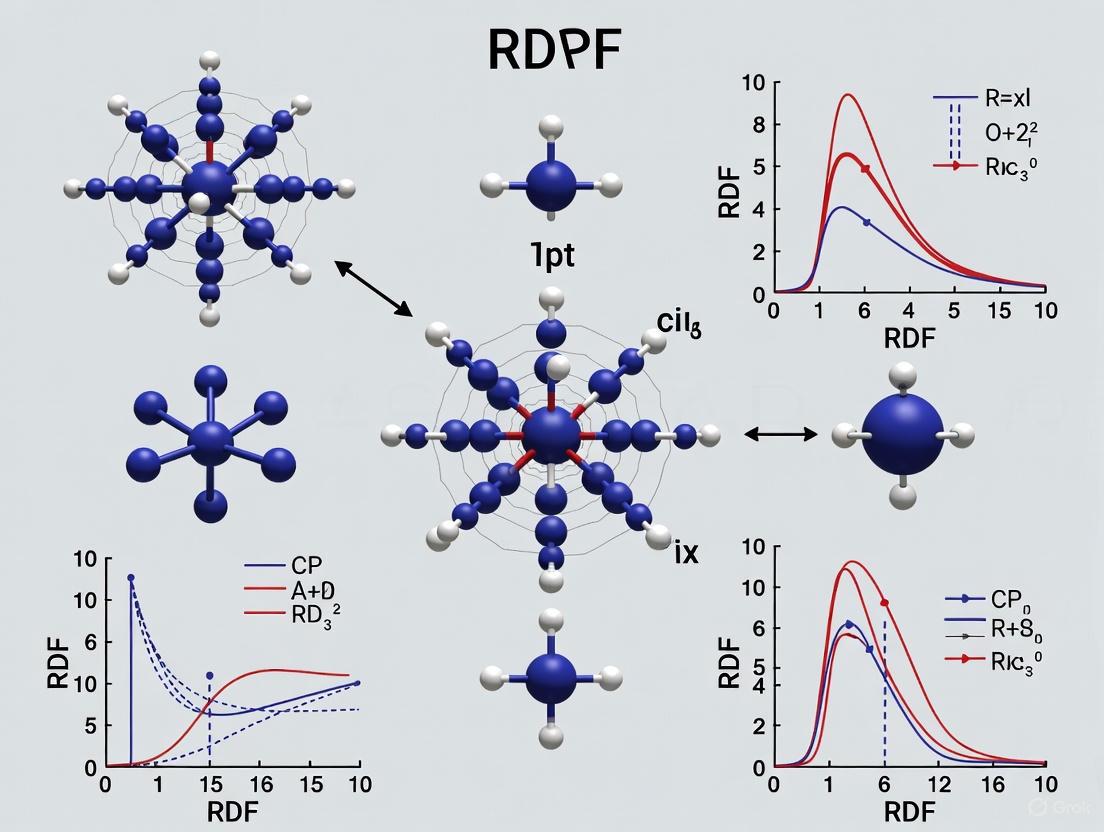

Diagram 1: Computational workflow for calculating radial distribution functions from atomic coordinate data, showing the iterative process of pair distance calculation, histogram binning, and final normalization.

Table 2: Key Parameters for RDF Calculation in Computational Tools

| Parameter | Typical Setting | Function | Implementation in rdfshg |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cutoff (rc/rcut) | Half of box length | Maximum distance for RDF calculation | rcut parameter |

| Number of Bins (nbin) | 400-500 | Resolution of RDF histogram | nbin parameter |

| Sampling Stride | 100-1000 MC steps | Frequency of RDF sampling | Specified in rdflist |

| Smoothing Parameter | 0 (no smoothing) to 2+ | Reduces noise in RDF | ismooth parameter |

| Central Atom Type | Specific atom type | Defines reference particles | iatom parameter |

| Neighbor Atom Type | Specific atom type | Defines neighbor particles | jatom parameter |

Advanced Applications and Extension

Multicomponent Systems and Partial RDFs

For systems containing multiple chemical species, the RDF analysis extends to partial radial distribution functions g_{αβ}(r), which describe the density probability for an atom of species α to have a neighbor of species β at distance r [5] [9]. An N-component material requires an N×N matrix of pairwise RDFs, of which N(N+1)/2 are unique due to symmetry [5]. For example, a binary alloy like Ni₃Al has three unique partial RDFs: Ni-Ni, Al-Al, and Ni-Al [5].

The generalized multicomponent short-range order (GM-SRO) method utilizes a shell-based counting of atoms in three-dimensional radial distances similar to RDF construction, providing quantitative measures of elemental clustering (positive GM-SRO) or ordering (negative GM-SRO) in complex alloys [5]. However, limitations in spatial resolution of experimental techniques like atom probe tomography (APT) can affect the accurate determination of these parameters, with detection of atomic ordering subject to an upper limit of spatial uncertainty described by Gaussian distributions with standard deviation of approximately 1.3 Ã… [5].

Thermodynamic Connections and Kirkwood-Buff Theory

The RDF provides a crucial connection to thermodynamics through the Kirkwood-Buff integral, which for a given radius r is defined as [7]:

G_{ij} = 4π∫(g_{ij} - 1)r²dr

This integral forms the basis of Kirkwood-Buff solution theory, which links the microscopic details of molecular distributions to macroscopic thermodynamic properties [1] [7]. The RDF can be inverted to predict potential energy functions using the Ornstein-Zernike equation or structure-optimized potential refinement [1].

Another fundamental relationship exists between the RDF and the potential of mean force (PMF), which is defined as the reversible work required to bring two particles from infinite separation to distance r [6]. The PMF can be directly obtained from the RDF using the relation [6]:

βW(r) = -ln g(r) + ln g(∞)

where β = 1/kT, and g(∞) approaches 1 for homogeneous systems [6]. This relationship provides deep physical insight into the effective interactions between particles in condensed phases.

Diagram 2: Relationship between the radial distribution function and derived quantities, showing how g(r) connects to both structural metrics and thermodynamic properties through mathematical transformations.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Computational Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for RDF Analysis

| Tool/Reagent | Function/Role | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Synchrotron X-ray Source | High-intensity radiation for scattering experiments | Experimental RDF determination from LBCCs [4] |

| Neutron Scattering Facility | Probe for light elements and magnetic materials | Complementary RDF measurements [4] |

| Atom Probe Tomography (APT) | 3D atomic coordinate mapping with elemental identification | Local structure analysis in complex alloys [5] |

| GROMACS gmx rdf | Molecular dynamics analysis tool | RDF calculation from simulation trajectories [8] |

| rdfshg | Specialized RDF analysis code with coordination number | Advanced structural analysis [3] |

| DLMONTE | Monte Carlo simulation package | RDF sampling in canonical ensemble [6] |

| HDRDF Modeling | Hierarchical decomposition method | Local structure analysis of complex nanomaterials [4] |

| Silane, triethoxy(3-iodopropyl)- | Silane, triethoxy(3-iodopropyl)-, CAS:57483-09-7, MF:C9H21IO3Si, MW:332.25 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 2,3-Dibromo-5,6-diphenylpyrazine | 2,3-Dibromo-5,6-diphenylpyrazine, CAS:75163-71-2, MF:C16H10Br2N2, MW:390.07 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The radial distribution function represents a fundamental bridge between the microscopic world of atomic arrangements and macroscopic observable properties, providing a versatile tool for characterizing local structure across diverse systems from simple liquids to complex multicomponent alloys and sustainable energy materials. Through its dual interpretation as both a probability measure and a local density descriptor, the RDF enables researchers to quantify short-range order, determine coordination environments, validate computational models, and connect structural features to thermodynamic behavior. As experimental techniques advance with improved spatial resolution and computational methods become increasingly sophisticated, the application of RDF analysis continues to expand, offering deeper insights into the structural underpinnings of material properties and facilitating the development of novel materials with tailored characteristics for pharmaceutical, energy, and technological applications.

Linking RDF to Thermodynamics and Material Properties

The term RDF presents a unique convergence in scientific computing, representing two distinct but potentially interconnected concepts: the Resource Description Framework, a semantic web standard for data integration, and the Radial Distribution Function, a cornerstone of statistical mechanics. This guide explores the innovative linkage between these domains, demonstrating how semantic web technologies can organize and interrogate complex thermodynamic and material data. Such integration is increasingly vital for managing the vast, multi-scale data generated in modern materials science and drug development, enabling researchers to uncover deeper relationships between atomic-scale interactions and macroscopic material behavior.

The application of semantic web technologies to materials research represents a paradigm shift from traditional, siloed data management toward a FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable) data ecosystem. [10] By expressing material characteristics, experimental conditions, and computational results using RDF, researchers can create a richly interconnected knowledge graph that captures complex relationships and enables sophisticated, federated queries across distributed data sources. This approach is particularly powerful for thermodynamic properties derived from radial distribution functions, as it preserves the contextual information essential for reproducibility and knowledge discovery.

Core Concepts: RDF and Thermodynamics

Resource Description Framework (RDF) in Scientific Context

The Resource Description Framework is a directed graph-based data model for representing information about resources on the web. [11] Its fundamental structure is the triple, consisting of a subject, predicate, and object, which together form a semantic statement about relationships. For example, in a materials science context, a triple might state "MaterialX hasthermalconductivity 150W/mK", creating a machine-readable assertion about a material property. [12] [11]

RDF utilizes Uniform Resource Identifiers (URIs) to uniquely identify entities and relationships, enabling precise disambiguation of scientific concepts across different databases and research domains. [11] This capability is enhanced by ontologies like the Web Ontology Language (OWL), which provide formal definitions and constraints for domain concepts, allowing for logical reasoning and consistency checking across distributed data sources. [13] [12] The SPARQL query language enables researchers to extract complex patterns from these interconnected datasets, asking sophisticated questions that span multiple data sources and conceptual domains. [12]

Radial Distribution Function (RDF) in Thermodynamics

In statistical mechanics, the radial distribution function (also abbreviated RDF) describes how the density of particles varies as a function of distance from a reference particle. [14] Mathematically, it is defined as:

$$g(r) = \frac{{\rho(r)}}{{\rho_{bulk}}}$$

Where $\rho(r)$ is the particle density at distance $r$ from the reference particle, and $\rho_{bulk}$ is the average bulk density. [14] This function provides fundamental insights into the molecular structure of materials, revealing short-range order, solvation shells, and phase transitions that directly determine thermodynamic properties. [14]

The RDF serves as a bridge between microscopic interactions and macroscopic thermodynamic properties. Through statistical mechanical relationships, integrals of the RDF can be used to calculate key thermodynamic properties including: [14]

- Internal energy from particle-particle interactions

- Pressure via the virial equation of state

- Chemical potentials and activity coefficients

- Compressibility through integral equation theories

Table 1: Thermodynamic Properties Calculable from Radial Distribution Functions

| Property | Theoretical Relationship | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Internal Energy | $U = 2\pi N\rho\int_{0}^{\infty} g(r)u(r)r^2 dr$ | Energy of Lennard-Jones fluids [14] |

| Pressure | $\frac{P}{\rho kT} = 1 - \frac{2\pi\rho}{3kT}\int_{0}^{\infty} g(r)\frac{du(r)}{dr}r^3 dr$ | Equation of state development [15] |

| Chemical Potential | $\mu = kT\ln(\rho\Lambda^3) + 2\pi\rho\int{0}^{1}\int{0}^{\infty} g(r,\xi)u(r)r^2 drd\xi$ | Solvation thermodynamics [15] |

| Compressibility | $kT\left(\frac{\partial\rho}{\partial P}\right)T = 1 + 4\pi\rho\int{0}^{\infty} [g(r) - 1]r^2 dr$ | Phase behavior prediction [15] |

Integrating Semantic and Scientific RDFs: Methodological Approaches

RDF-based Knowledge Representation for Thermodynamic Data

The integration of thermodynamic data using semantic RDF begins with the development of domain-specific ontologies that formally define concepts, relationships, and constraints. For radial distribution function data, this includes defining classes such as "SimulationSystem", "InteractionPotential", "ThermodynamicState", and "RDFCalculation", with precise relationships between them. [12] [10]

A practical implementation involves creating RDF representations of molecular simulation workflows, where each step—from force field parameterization to RDF calculation and thermodynamic property derivation—is captured as interconnected triples. This approach enables researchers to trace the provenance of calculated properties back to fundamental simulation parameters, ensuring reproducibility and facilitating data reuse. [10] For example, the eNanoMapper ontology provides a framework for representing nanomaterial characteristics and their interactions with biological systems, which can be extended to encompass thermodynamic properties derived from RDF analysis. [10]

Diagram 1: RDF knowledge graph for thermodynamic data (76 characters)

Experimental and Computational Protocols

Molecular Dynamics Simulation for RDF Calculation

Objective: To compute the radial distribution function of a Lennard-Jones fluid and derive thermodynamic properties. [14]

Methodology:

- System Preparation:

- Initialize N particles (typically 500-10,000) in a cubic simulation box with periodic boundary conditions

- Set initial positions on a lattice and assign random velocities according to the Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution at target temperature

Force Field Parameterization:

- Implement Lennard-Jones potential: $U(r) = 4\epsilon\left[\left(\frac{\sigma}{r}\right)^{12} - \left(\frac{\sigma}{r}\right)^6\right]$

- Apply appropriate truncation and long-range corrections (e.g., Ewald summation for electrostatic interactions if present)

Equilibration Phase:

- Run simulation in NVT ensemble using thermostat (e.g., Nosé-Hoover) for 10,000-100,000 steps

- Monitor potential energy and temperature for stability

- Apply barostat if running in NPT ensemble to achieve target density

Production Phase:

- Continue simulation for 100,000-1,000,000 steps with trajectory sampling every 100-1000 steps

- Compute RDF during simulation using histogram method: $$g(r) = \frac{\langle \Delta N(r, r+\Delta r) \rangle}{4\pi r^2 \Delta r \rho}$$

- Ensure adequate sampling by running until RDF profile stabilizes

Thermodynamic Property Calculation:

- Compute internal energy from RDF and potential function

- Calculate pressure using virial theorem

- Derive chemical potentials using thermodynamic integration or test particle insertion

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for RDF Studies

| Item | Function | Example Implementation |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Dynamics Engine | Core simulation platform | LAMMPS, GROMACS, HOOMD-blue [14] |

| Force Fields | Define interatomic interactions | Lennard-Jones, CHARMM, AMBER [14] |

| Thermostats/Barostats | Control ensemble conditions | Nosé-Hoover, Berendsen, Parrinello-Rahman [14] |

| Trajectory Analysis Tools | Compute RDF from simulation data | MDAnalysis, VMD, custom scripts [14] |

| RDF Visualization Software | Visualize molecular structure | OVITO, VMD, Matplotlib [14] |

| Semantic Annotation Tools | Add ontological metadata | Protégé, RDFLib, Apache Jena [12] [10] |

Semantic Annotation of RDF Data

Objective: To create FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable) representations of radial distribution function data using semantic web technologies. [10]

Methodology:

- Ontology Selection and Development:

- Identify relevant existing ontologies (ChEBI, SIO, ENM)

- Extend ontologies with domain-specific terms for thermodynamic concepts

- Define relationships between simulation parameters and calculated properties

RDF Generation:

- Create URIs for each simulation system and component

- Express simulation parameters as RDF triples using appropriate predicates

- Link calculated RDF profiles to their thermodynamic derivatives

- Capture provenance information linking results to computational methods

Data Integration:

- Use OWL sameAs and equivalentProperty to align with external datasets

- Implement SPARQL endpoints for querying the knowledge graph

- Enable federated queries across multiple RDF sources

Application:

- Execute complex queries linking material composition to structural and thermodynamic properties

- Discover relationships across different simulation studies

- Enable meta-analysis of RDF-based thermodynamic predictions

Case Studies and Applications

Nanomaterial Characterization and Safety Assessment

The application of semantic RDF to organize and interrogate nanomaterial data demonstrates the power of this integrated approach. In a recent study, researchers created an RDF-based knowledge base for engineered nanomaterials (ENMs), capturing their physicochemical properties and biological interactions. [10] This included linking material characteristics to adverse outcome pathways (AOPs) through molecular initiating events, enabling sophisticated queries about potential nanomaterial hazards.

By representing 83 unique ENMs with their properties and effects in RDF, researchers could perform federated SPARQL queries that connected material characteristics to biological outcomes through shared ontological annotations. [10] This approach allowed for the systematic exploration of relationships between nanomaterial properties (size, shape, surface chemistry) and their interactions with biological systems, demonstrating how semantic technologies can enhance the prediction of material behavior and toxicity.

Drug Discovery and Development

In pharmaceutical research, the integration of chemical, biological, and clinical data using RDF technologies has created new opportunities for knowledge discovery. The DisGeNET-RDF resource makes available knowledge on the genetic basis of human diseases in the Semantic Web, representing gene-disease associations and their provenance as machine-processable resources. [16] This enables researchers to explore complex relationships between chemical structures, protein targets, disease mechanisms, and clinical outcomes through federated queries.

The REDESIGN framework exemplifies the application of RDF technologies to precision medicine analytics, utilizing "flexible" ontology-enabled datasets of curated signal transduction pathways to uncover differential pathway mechanisms at the gene-to-gene level. [17] This approach moves beyond traditional pathway analysis methods by incorporating biological isomorphism through RDF predicates like "sameAs" and "contains", enabling more biologically relevant comparisons between pathway states in different disease conditions. [17]

Diagram 2: RDF workflow for drug development (57 characters)

Advanced Materials Design

The integration of RDF-based data management with molecular simulation and characterization has accelerated the design of advanced materials. Researchers have applied semantic technologies to capture structure-property relationships in diverse material systems, from metal-organic frameworks for gas storage to polymer composites with tailored mechanical properties.

In these applications, the radial distribution function serves as a critical bridge between atomic-scale structure and macroscopic material performance. By semantically annotating RDF profiles and their associated thermodynamic derivatives, researchers can build predictive models that connect chemical composition, processing conditions, and final material properties. This approach is particularly valuable for high-throughput computational screening, where semantic technologies enable efficient organization and retrieval of thousands of simulation results.

Implementation Considerations

Technical Infrastructure

Successful implementation of RDF-based approaches for thermodynamic and material properties requires careful consideration of technical infrastructure. Triplestores—specialized databases for RDF data—vary in their performance characteristics, with native stores (e.g., RDF4J, TDB) often outperforming non-native implementations for complex queries. [18] The choice between disk-based and in-memory storage involves trade-offs between query performance, data persistence, and scalability, with in-memory solutions offering faster query response but limited by available RAM. [18]

Serialization formats for RDF data include Turtle (human-readable), JSON-LD (web-friendly), and RDF/XML (standardized but verbose), each with distinct advantages for different use cases. [11] For large-scale molecular simulation data, a hybrid approach often works best, with metadata and derived properties stored as RDF while large trajectory files remain in specialized binary formats.

Data Modeling Challenges

Representing thermodynamic concepts and material properties in RDF requires careful data modeling to balance expressivity with computational efficiency. Key considerations include:

- Temporal and spatial scales: Integrating data from quantum calculations (picometers, femtoseconds) to continuum models (meters, seconds)

- Uncertainty representation: Capturing measurement errors, simulation artifacts, and theoretical approximations

- Multi-scale relationships: Connecting atomic RDFs to mesoscale structure and macroscopic properties

- Provenance tracking: Maintaining links between derived properties and their computational or experimental origins

Effective data modeling often employs a modular ontology architecture, with core upper-level ontologies (e.g., SIO—SemanticScience Integrated Ontology) extended with domain-specific extensions for materials science and thermodynamics. [10]

The integration of Resource Description Framework technologies with radial distribution function analysis represents a powerful convergence of data science and physical science that is transforming materials research and drug development. As both fields continue to evolve, several emerging trends promise to further enhance this synergy:

The development of domain-specific ontologies for materials science and thermodynamics continues to mature, with efforts like the NanoParticle Ontology (NPO) and eNanoMapper ontology providing increasingly comprehensive frameworks for representing nanomaterial characteristics and their biological interactions. [10] These ontological resources, combined with growing adoption of FAIR data principles, are creating a more interconnected ecosystem for materials knowledge.

Advances in knowledge graph embeddings and graph neural networks are enabling new approaches to predictive materials design, where patterns in semantically enriched RDF data can suggest novel material compositions with desired properties. Similarly, the integration of automated reasoning with molecular simulation allows for more intelligent exploration of chemical space, focusing computational resources on promising regions identified through semantic pattern recognition.

In conclusion, the linkage between semantic and scientific RDFs creates a powerful framework for addressing complex challenges in thermodynamics and material properties research. By enabling sophisticated integration and interrogation of diverse data sources, these technologies accelerate the discovery and design of new materials with tailored properties for applications ranging from energy storage to targeted therapeutics. As implementation best practices continue to develop and computational infrastructure matures, this integrated approach promises to become increasingly central to advanced materials research and development.

The Radial Distribution Function (RDF), denoted as g(r), is a fundamental statistical measure in condensed matter physics and materials science that defines the probability of finding a particle at a distance r from a reference particle, relative to what would be expected for a perfectly random distribution at the same density [2]. This function provides a powerful link between the microscopic arrangement of atoms or molecules and the macroscopic thermodynamic properties of a material [19]. By analyzing g(r), researchers can quantify the local structure and degree of order within a system, making it an indispensable tool for investigating gases, liquids, and solids across scientific disciplines, including drug development where understanding molecular interactions is critical.

The RDF is formally defined through the relationship g(r) = Ï(r)/Ï_bulk, where Ï(r) is the local density at distance r, and Ï_bulk is the average bulk density of the system [2]. In practical terms, for a simulation or experiment, it can be computed as g(r) ≈ dn_r/(4Ï€r²dr·Ï), where dn_r represents the number of particles in a spherical shell of thickness dr at distance r [2]. The resulting RDF profile serves as a structural fingerprint that reveals characteristic features of short-range, intermediate, and sometimes long-range order, providing critical insights for researchers analyzing molecular interactions in pharmaceutical compounds or novel material systems.

Core Principles of RDF Analysis

The radial distribution function serves as a direct bridge between the microscopic world of atomic and molecular interactions and the macroscopic observable properties of materials. Its calculation and interpretation rely on several foundational principles that enable researchers to extract meaningful structural information from different states of matter.

Mathematical Foundation

The RDF is fundamentally a measure of conditional probability. For a multicomponent system containing N different elements, the complete structural description requires an N×N matrix of pairwise RDFs [5]. Due to symmetry, only N(N+1)/2 of these pairwise functions are unique. For example, in a binary alloy like Ni₃Al, three unique RDFs exist: Ni-Ni, Al-Al, and Ni-Al [5]. Each pairwise RDF describes the spatial correlation between different atomic species, providing a comprehensive picture of the local chemical environment. In experimental techniques like X-ray or neutron diffraction, a total RDF is observed which represents a weighted combination of these pairwise component RDFs based on the relative scattering strengths of the constituent elements [5].

Connecting RDF to Material Properties

The radial distribution function directly influences numerous macroscopic material properties through statistical mechanics relationships. The RDF enables the calculation of thermodynamic properties like energy and pressure through spatial integration of pair potentials [19]. For drug development professionals, this is particularly valuable for understanding how molecular packing affects solubility, stability, and bioavailability of pharmaceutical compounds. The coordination number, obtained by integrating g(r) to the first minimum, indicates how many nearest neighbors surround a central particle [2]. This parameter profoundly impacts properties like density, diffusion rates, and mechanical behavior. Additionally, the RDF provides the essential structural information needed to compute scattering patterns for direct comparison with X-ray diffraction experiments, validating computational models against experimental data [19] [5].

Comparative RDF Analysis Across States of Matter

The radial distribution function exhibits distinctly different characteristics for gases, liquids, and solids, reflecting their underlying structural organization. The following table summarizes the key RDF features for the three primary states of matter:

Table 1: Characteristic RDF Profiles for Different States of Matter

| State | Structural Order | RDF Profile Characteristics | Coordination Sphere | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gases [2] | No long or short-range order | • g(r) = 0 for r < σ (excluded volume)• Single coordination sphere• Rapid decay to g(r) = 1 beyond several molecular diameters | Weak coordination sphere that rapidly decays to bulk density | Molecules are widely separated with kinetic energy dominating over attractive forces |

| Liquids [2] | Short-range order only | • Sharp first peak at ~σ• Subsequent damped oscillations• Convergence to g(r) = 1 at large r | First coordination sphere is most distinct; subsequent spheres become progressively weaker | Represents a compromise between random thermal motion and intermolecular attractions |

| Solids [2] | Long-range periodic order | • Discrete, well-defined peaks at specific ratios of σ• No decay in amplitude with increasing distance• Peaks at σ, √2σ, √3σ, etc., for crystal lattices | Multiple sharp coordination spheres extending to long range | Molecules fluctuate near fixed lattice positions with highly specific structure |

RDF of Gases

In the gaseous state, molecules are widely separated with kinetic energy dominating over intermolecular attractive forces [20]. The RDF reflects this disordered state with a simple profile: g(r) = 0 at very short distances (r < σ) due to hard-core repulsion between molecules, followed by a single coordination sphere where g(r) > 1 in the region slightly larger than the molecular diameter (σ < r < 2σ), before rapidly decaying to the bulk density value (g(r) = 1) at larger separations [2]. This simple profile indicates the absence of any persistent structural organization beyond the immediate exclusion zone created by molecular repulsion.

RDF of Liquids

Liquids represent a compromise between the random thermal motion of gases and the structured organization of solids. Liquid RDFs typically display a sharp first peak at approximately the molecular diameter (σ), indicating the first coordination shell where molecules are most likely to be found [2]. This is followed by several progressively weaker and broader peaks representing second, third, and higher coordination shells. The damped oscillatory pattern eventually converges to the bulk density (g(r) = 1) at larger distances, demonstrating the loss of long-range order characteristic of liquids [2]. The coordination number, calculated by integrating 4Ï€r²Ïg(r) to the first minimum, typically reaches approximately 12 for simple liquids exhibiting optimal packing of hard spheres, but can be significantly lower (4-5 for water) for liquids with strong directional interactions like hydrogen bonding [2].

RDF of Solids

In crystalline solids, atoms or molecules oscillate around fixed lattice positions in a highly periodic arrangement [2]. This long-range order manifests in the RDF as a series of sharp, discrete peaks at well-defined distances corresponding to the crystal lattice geometry [2]. For simple cubic structures, these peaks occur at distances of σ, √2σ, √3σ, and so forth, reflecting the specific coordination shells of the crystal structure [2]. Unlike liquids, the peak amplitudes in solid RDFs do not decay with increasing distance, maintaining their intensity throughout the crystal lattice. This persistent long-range order makes solids particularly suited for RDF analysis, as the resulting profile provides a definitive fingerprint of the specific crystal structure.

Experimental and Computational Methodologies

Calculating accurate radial distribution functions requires careful implementation of either experimental or computational protocols. The following diagram illustrates the general workflow for RDF determination from molecular simulations:

RDF Calculation Workflow from Molecular Simulations

Traditional Histogram-Based Methods

The conventional approach for computing RDFs from molecular simulations involves binning pair separations into histograms. This method calculates g(r) by counting the number of particle pairs dn(r) found at distances between r and r + Δr, then normalizing by the volume of the spherical shell and the bulk density [2] [19]. The mathematical implementation follows:

- Distance Calculation: Compute all pairwise distances between particles in the system: r_ij = |r_i - r_j| for i ≠j

- Bin Assignment: For each distance r_ij, determine the appropriate bin k such that k·Δr ≤ r_ij < (k+1)·Δr

- Histogram Accumulation: Increment the count in bin k for each distance

- Normalization: Normalize the histogram using the formula: g(r_k) = [N(r_k, r_k+Δr) / N_total] / [4Ï€r_k²Δr·Ï] where N_total is the total number of particles, and Ï is the bulk number density

While straightforward to implement, this histogram-based approach suffers from inherent subjectivity in bin-size selection, high statistical uncertainty, and slow convergence rates [19]. The arbitrary choice of bin size represents a trade-off between resolution and noise, with smaller bins revealing more detailed features but requiring substantially more data to achieve acceptable signal-to-noise ratios.

Advanced Spectral Monte Carlo (SMC) Approach

To address limitations of histogram methods, the Spectral Monte Carlo (SMC) approach expresses the RDF as an analytical series expansion using orthogonal basis functions [19]. This advanced methodology offers reduced subjectivity, lower noise, and faster convergence compared to traditional binning:

- Functional Expansion: Express g(r) as g_M(r) = Σ_{j=0}^M a_j φ_j(r) where φ_j(r) are orthogonal basis functions defined on the domain [0, r_c], a_j are coefficients to be determined, and M is a mode cutoff [19]

- Coefficient Determination: Compute coefficients using Monte Carlo quadrature estimates: a_j ≈ Ä_j = N(r_c)/n_pairs · Σ_{k=1}^{n_pairs} φ_j(r_k)/(4Ï€r_k²Ï) where r_k is the k-th pair separation, n_pairs is the total number of such separations, and N(r_c) is the expected number of particles in a sphere of radius r_c [19]

- Basis Function Selection: Choose appropriate orthogonal basis functions (e.g., Legendre polynomials, cosines) that ensure smooth, well-behaved reconstructions of the RDF

- Convergence Assessment: Employ Sobolev norms to objectively evaluate RDF quality by quantifying fluctuations, providing a more appropriate metric than traditional sum-of-squares measures [19]

The SMC method provides particular advantages for applications requiring differentiation of the RDF, such as coarse-grained force-field calibration through iterative Boltzmann inversion, where smooth, analytical representations are essential [19].

Experimental Determination Techniques

Experimentally, RDFs can be derived from several advanced characterization techniques:

- Atom Probe Tomography (APT): This technique provides three-dimensional elemental mapping with near-atomic resolution (~0.1-0.5 nm), allowing direct calculation of pairwise RDFs from spatial coordinates of millions of atoms [5]. However, limitations include data sparsity (only ~â…“ of atoms are typically resolved) and spatial uncertainty that can obscure atomic ordering signals [5]

- X-ray and Neutron Diffraction: These scattering techniques provide total RDFs weighted by the relative scattering strengths of constituent elements, which can be compared with computational predictions to validate models [5]

- Generalized Multicomponent Short-Range Order (GM-SRO) Analysis: A shell-based counting method similar to RDF construction that quantifies elemental clustering (positive GM-SRO) or ordering (negative GM-SRO) in complex multicomponent systems [5]

Each experimental approach carries specific limitations regarding spatial resolution, element sensitivity, and data interpretation constraints that must be considered when comparing with computational RDFs.

Essential Research Tools and Reagents

Table 2: Essential Research Tools for RDF Analysis

| Tool/Technique | Primary Function | Key Applications in RDF Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Dynamics (MD) Software (e.g., LAMMPS [5]) | Simulates particle trajectories using classical force fields | Generates atomic coordinates for RDF calculation from computational models |

| Spectral Monte Carlo (SMC) Algorithms [19] | Computes RDFs via orthogonal function expansion rather than histograms | Provides smoother, more objective RDFs with faster convergence; ideal for force-field calibration |

| Atom Probe Tomography (APT) [5] | Determines 3D spatial coordinates and elemental identities of atoms | Enables experimental RDF calculation for complex alloys and materials |

| Iterative Boltzmann Inversion (IBI) [19] | Calibrates coarse-grained force fields to match target RDFs | Derives effective potentials for molecular simulations using RDFs as target data |

| Fractional Cumulative RDF (FCRDF) [5] | Transforms standard RDF to enhance visibility of local compositions | Improves analysis of short to medium-range ordering in complex structures |

Research Applications and Case Studies

Radial distribution function analysis provides critical insights across multiple research domains, from fundamental materials science to applied pharmaceutical development.

Characterizing Atomic Ordering in Complex Alloys

In high-entropy alloys (HEAs) composed of five or more elements in near-equimolar ratios, RDF analysis helps resolve fundamental questions about atomic distributions. Researchers have applied pairwise RDF analysis to APT data sets for the six-component Alâ‚.₃CoCrCuFeNi alloy to visualize elemental segregation and short-range ordering [5]. By computing the complete matrix of pairwise RDFs (Ni-Ni, Al-Al, Co-Co, Cr-Cr, Fe-Fe, Cu-Cu, and all cross correlations), scientists can quantify the tendency for specific element pairs to cluster or avoid each other in the complex crystalline environment. This information is crucial for understanding the unique mechanical properties and stability of HEAs, as local chemical ordering significantly influences dislocation motion and strengthening mechanisms.

Force-Field Development via Iterative Boltzmann Inversion

RDFs play a central role in developing accurate coarse-grained (CG) models for molecular simulations through iterative Boltzmann inversion (IBI). This approach uses the relationship:

U_{i+1}(r) = U_i(r) + k_BT ln[g_i(r)/g_target(r)]

where U_i(r) is the potential at iteration i, k_BT is the thermal energy, g_i(r) is the RDF from a CG simulation using forces derived from U_i(r), and g_target(r) is the target RDF [19]. The success of this methodology heavily depends on obtaining accurate, low-noise RDFs from reference simulations, making advanced methods like SMC particularly valuable for this application [19]. The differentiable analytical form of SMC-generated RDFs facilitates the potential optimization process, enabling more robust and efficient force-field development for complex molecular systems, including those relevant to pharmaceutical applications.

Analyzing Molecular Interactions in Drug Development

While not explicitly covered in the search results, the principles of RDF analysis directly extend to pharmaceutical research, where understanding molecular packing and interactions is crucial for predicting drug solubility, stability, and formulation behavior. RDFs can characterize:

- Hydrogen-bonding patterns between active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) and excipients

- Solvation shells around drug molecules in different solvent environments

- Molecular packing in amorphous solid dispersions

- Aggregate formation in protein therapeutics

These applications demonstrate the versatility of RDF analysis across multiple scientific disciplines and its growing importance in rational materials and drug design.

Radial distribution function analysis provides a powerful, versatile framework for quantifying structural relationships across different states of matter. The characteristic RDF profiles of gases, liquids, and solids directly reflect their underlying physical organization, from the complete disorder of gases to the short-range order of liquids and long-range periodicity of crystalline solids. Advanced computational methods like Spectral Monte Carlo quadrature offer significant improvements over traditional histogram-based approaches, reducing subjectivity and noise while providing analytically tractable representations essential for force-field development. Coupled with experimental techniques like atom probe tomography, RDF analysis continues to deliver fundamental insights into atomic-scale structure-property relationships across diverse scientific fields, from metallurgy to pharmaceutical development. As computational power grows and experimental resolution improves, RDF methodology will undoubtedly remain an essential component of the materials characterization toolkit, enabling deeper understanding of complex molecular systems and guiding the rational design of novel materials with tailored properties.

Understanding Partial RDFs in Multi-Component Systems and Alloys

The radial distribution function (RDF) serves as a fundamental statistical measure for characterizing atomic-scale structure in condensed matter. In multi-component systems and alloys, partial RDFs provide unparalleled insights into the local chemical environments, short-range ordering, and architectural patterns that govern material properties. This technical guide explores the analytical power of partial RDFs through contemporary research applications, detailing methodological protocols and computational approaches for extracting architectural information from complex alloy systems.

In materials science, the radial distribution function (RDF), denoted as g(r), quantitatively describes how the density of atoms varies as a function of distance from a reference atom [21]. For multi-component systems containing N different elements, the structural description becomes significantly more complex, requiring an N×N matrix of pairwise partial RDFs [5]. Each partial RDF, gâ‚Õ¢(r), specifically describes the probability of finding an atom of type B at a distance r from an atom of type A, normalized by the average density of B atoms [5]. This elemental resolution enables researchers to deconvolute the complex atomic arrangements in technologically important materials such as high-entropy alloys, core-shell nanoparticles, and metallic glasses.

The analytical power of partial RDFs lies in their ability to reveal local chemical ordering phenomena that are obscured in total RDFs obtained from conventional diffraction techniques. As noted in research on PtCu bimetallic nanoparticles, "the local atomic structure should be very sensitive toward nanoparticle architecture" [22]. For instance, in a perfect core-shell structure, one would expect specific coordination number relationships: around core atoms, the sum of coordination numbers would approximate bulk values, while around shell atoms, the total coordination would be less than bulk due to surface effects [22].

Analytical Capabilities of Partial RDFs

Detecting Atomic-Scale Architecture

Partial RDFs provide distinct signatures that enable researchers to discriminate between different architectural models in multi-component systems. In bimetallic nanoparticles, the relationships between coordination numbers and interatomic distances derived from partial RDFs can distinguish between core-shell, inverted core-shell, and solid solution architectures [22]. For example, researchers investigating PtCu nanoparticles demonstrated that "the relation of RDF to one of the possible nanoparticle architectures can be performed using supervised machine learning (ML) algorithms" [22], highlighting the sophisticated analytical applications now possible with RDF data.

Quantifying Short-Range Ordering

In complex concentrated alloys and high-entropy systems, partial RDFs enable quantification of short-range ordering (SRO) parameters. The Generalized Multicomponent Short-Range Order (GM-SRO) method utilizes "a shell-based counting of atoms in a three-dimensional radial distances" similar to RDF construction [5]. Positive GM-SRO values indicate clustering of particular atomic species, while negative values suggest preferential ordering between different elements [5]. This analytical approach has proven particularly valuable for understanding the atomic-scale structure of high-entropy alloys where local chemical fluctuations significantly influence mechanical properties.

Characterizing Bond-Length Variations

Partial RDFs reveal subtle bond-length variations that reflect chemical interactions between constituent elements. In Nb-doped CuZr metallic glasses, researchers discovered "a remarkable bond shortening in the Zr-Nb pair, which was about 0.2 Ã… shorter than its corresponding Goldschmidt value" despite the positive heat of mixing between these elements [23]. Such unexpected structural features, detectable only through partial RDF analysis, provide crucial insights for understanding the enhanced glass-forming ability in multicomponent alloys.

Table 1: Key Structural Information Derivable from Partial RDF Analysis

| Parameter | Structural Significance | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Peak Position | Average bond length between atomic pairs | Detection of bond shortening in Zr-Nb pairs in metallic glasses [23] |

| Peak Area | Coordination numbers of specific atomic pairs | Distinguishing core-shell vs. solid solution architectures in nanoparticles [22] |

| Peak Width | Structural disorder and thermal vibrations | Assessing spatial uncertainty in atom probe tomography data [5] |

| Peak Splitting | Presence of multiple distinct bonding environments | Identifying chemical heterogeneity in high-entropy alloys [5] |

Experimental and Computational Methodologies

Experimental Techniques for RDF Determination

Extended X-ray Absorption Fine Structure (EXAFS)

EXAFS spectroscopy provides element-specific partial RDFs with exceptional chemical resolution. The technique "provides outstanding elemental resolution: the type of central atom (X-ray absorber) is precisely defined, and the types of surrounding atoms are determined with conventional error in atomic number Z±2" [22]. However, EXAFS-derived RDFs are typically limited to short-range correlations (R ≲ 5 Å) due to the finite mean free path of photoelectrons [22]. The experimental protocol involves measuring X-ray absorption spectra above elemental absorption edges, followed by background subtraction, Fourier transformation, and fitting with theoretical models to extract partial RDF parameters.

Atom Probe Tomography (APT)

Atom probe tomography enables three-dimensional mapping of atomic positions and identities, from which partial RDFs can be directly calculated [5]. APT "provide a three-dimensional (3D) element mapping allowing scientists to map out the local chemical nature of complex alloys" with high spatial resolution (∼0.1–0.3 nm in depth and 0.3–0.5 nm laterally) and chemical sensitivity (∼10 ppm) [5]. The methodology involves specimen preparation via focused ion beam, field evaporation under ultra-high vacuum, and time-of-flight mass spectrometry for elemental identification. However, APT data suffers from limitations including "data sparsity (only about one third of atoms are spatially resolved) and noise (uncertainty in the atomic coordinates on the order)" which complicate RDF interpretation [5].

Total Scattering with Pair Distribution Function Analysis

Total scattering experiments, utilizing X-rays or neutrons, provide the total structure function S(Q), which can be Fourier transformed to obtain the total PDF (G(r)) [23]. For multi-component systems, the total PDF represents a weighted sum of all partial PDFs, with weights determined by the scattering strengths and concentrations of constituent elements [5]. The experimental workflow involves collecting scattering data to high momentum transfer values, applying corrections for background, absorption, and multiple scattering, followed by Fourier transformation to real space.

Computational Approaches for RDF Analysis

Molecular Dynamics Simulations

Classical molecular dynamics simulations generate atomic trajectories from which partial RDFs can be directly computed [22]. The methodology involves defining interatomic potentials, integrating equations of motion under appropriate thermodynamic conditions, and analyzing the resulting trajectories to calculate gâ‚Õ¢(r) = (Nâ‚NÕ¢)â»Â¹âŸ¨Î£áµ¢Î£{j≠i}δ(r - rᵢ₠+ r{jÕ¢})⟩, where Nâ‚ and NÕ¢ are the numbers of atoms of types A and B, and the angle brackets denote ensemble averaging. MD-derived RDFs provide a connection between interatomic potentials and resulting structural features, enabling hypothesis testing for atomic-scale structure.

Reverse Monte Carlo (RMC) Modeling

RMC simulation represents a powerful approach for refining atomic structural models against multiple experimental datasets simultaneously. As implemented in studies of CuZrNb metallic glasses, RMC "simulated experimental data do not include that of Nb K-edge EXAFS, we still can get reliable structural information because EXAFS is an element-specific method available for measuring the surroundings of each kind of atoms" [23]. The algorithm iteratively adjusts atomic positions to minimize the difference between calculated and experimental data, typically including total scattering data and multiple EXAFS spectra, thereby generating structural models consistent with all available experimental constraints.

Machine Learning Applications

Supervised machine learning algorithms enable automated classification of nanoparticle architectures based on partial RDF data [22]. The methodology involves generating synthetic RDF datasets from molecular dynamics simulations of different structural models, training classification algorithms (e.g., support vector machines, random forests, or neural networks) on these synthetic data, and applying the trained models to experimental RDFs for architectural identification. This approach demonstrates how "the relation of RDF to one of the possible nanoparticle architectures can be performed using supervised machine learning (ML) algorithms" [22].

Figure 1: Integrated workflow for partial RDF analysis combining experimental and computational approaches.

Case Studies in Alloy Systems

PtCu Bimetallic Nanoparticles

Research on carbon-supported PtCu nanoparticles demonstrates the sensitivity of partial RDFs to architectural features in bimetallic systems [22]. Through combined EXAFS analysis and molecular dynamics simulations, researchers established that "the ultimate sensitivity of radial distribution functions to architecture" enables discrimination between core-shell, gradient, and solid solution structures [22]. The coordination numbers derived from partial RDFs provided critical evidence of architectural features, with Pt-rich shells exhibiting reduced total coordination numbers compared to bulk values due to surface effects.

High-Entropy Alloys

In the six-component Alâ‚.₃CoCrCuFeNi high-entropy alloy, partial RDF analysis facilitated visualization of "elemental segregation at the nanoscale, though unambiguous identification of atomic ordering at the Ã…ngstrom (nearest-neighbor) scale remains a goal" [5]. The study implemented a Fractional Cumulative Radial Distribution Function (FCRDF) approach, which "allows for greater visibility of local compositions at short range in the structure" [5]. This computational innovation enhanced the detection of local chemical ordering in complex concentrated alloys.

Metallic Glasses

Partial RDF analysis of CuZrNb metallic glasses revealed that "strong interaction between Nb and Zr atoms leads to a shortened pair distance" and that "fraction of the icosahedral-like local structures increases with Nb addition" [23]. These structural insights, obtained through RMC modeling of EXAFS and diffraction data, explained the enhanced glass-forming ability associated with minor Nb additions. The research further discovered that "Nb atoms are apt to be separated with each other" in compositions with maximum glass-forming ability, highlighting the importance of solute distribution in metallic glass formation [23].

Table 2: Representative Partial RDF Findings in Alloy Systems

| Material System | Analytical Technique | Key Structural Finding | Impact on Properties |

|---|---|---|---|

| PtCu Nanoparticles | Pt L₃- and Cu K-EXAFS [22] | Architecture-dependent coordination numbers | Enhanced oxygen reduction reaction activity [22] |

| CuZrNb Metallic Glass | EXAFS + RMC [23] | Shortened Zr-Nb bonds (0.2 Ã… shorter than expected) | Enhanced glass-forming ability [23] |

| Alâ‚.₃CoCrCuFeNi HEA | APT + FCRDF [5] | Elemental segregation at nanoscale | Fundamental understanding of SRO in HEAs [5] |

| Ni₃Al | APT + FCRDF [5] | Detection limit of spatial uncertainty (1.3 Å standard deviation) | Methodology development for atomic ordering detection [5] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Partial RDF Analysis

| Reagent/Tool | Function/Application | Technical Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Synchrotron Radiation Source | High-brightness X-rays for EXAFS and total scattering | Energy tunability for element-specific spectroscopy [23] |

| Atom Probe Tomograph | 3D atomic-scale mapping of composition and structure | Spatial resolution: 0.1-0.3 nm depth, 0.3-0.5 nm lateral [5] |

| Molecular Dynamics Codes | Generate atomic trajectories for RDF calculation | LAMMPS, GROMACS, or custom codes with appropriate potentials [22] |

| RMCProfile Software | Reverse Monte Carlo modeling of experimental data | Simultaneous refinement of multiple datasets (XRD, EXAFS) [23] |

| High-Purity Metal Precursors | Synthesis of alloy nanoparticles and bulk samples | ≥99.99% purity for controlled composition and structure [22] |

| Methyl 4-amino-3-phenylbutanoate | Methyl 4-amino-3-phenylbutanoate, CAS:84872-79-7, MF:C11H15NO2, MW:193.24 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| (3-Phenyl-2-propen-1-YL)propylamine | (3-Phenyl-2-propen-1-YL)propylamine | Research-grade (3-Phenyl-2-propen-1-YL)propylamine hydrochloride. Explore its applications in neuroscience and medicinal chemistry. This product is For Research Use Only (RUO). Not for human or veterinary use. |

Advanced Analytical Framework

Fractional Cumulative RDF (FCRDF)

The Fractional Cumulative Radial Distribution Function represents an innovative computational approach that enhances visibility of local compositional variations. The FCRDF is derived from traditional partial RDFs through integration and normalization procedures that "allow for greater visibility of local compositions from short to medium range in the structure" [5]. This methodology has proven particularly valuable for analyzing APT data sets where spatial uncertainty complicates conventional RDF interpretation.

Handling Spatial Uncertainty in Experimental Data

A critical consideration in partial RDF analysis, particularly from techniques like APT, is the spatial uncertainty inherent in experimental measurements. Research on Ni₃Al established that "the ability to observe a signal of atomic ordering consistent with the known L1₂ crystal structure is heavily dependent on spatial uncertainty, irrespective of abundance" [5]. The study quantified that "detection of atomic ordering is subject to an upper limit of spatial uncertainty of atoms described with Gaussian distributions with a standard deviation of 1.3 Å" [5], providing important guidance for experimental design and data interpretation.

Figure 2: Impact of spatial uncertainty on atomic ordering detection in partial RDF analysis.

Partial radial distribution functions provide an indispensable analytical framework for elucidating atomic-scale structure in multi-component systems and alloys. Through advanced experimental techniques including EXAFS spectroscopy and atom probe tomography, combined with computational methods such as molecular dynamics and Reverse Monte Carlo simulations, researchers can extract detailed information about chemical ordering, local coordination environments, and nanoscale architectural features. The continuing development of methodologies like Fractional Cumulative RDFs and machine learning classification promises to further enhance the analytical power of partial RDFs for understanding structure-property relationships in complex material systems.

The Significance of Coordination Numbers from RDF Integrals

The Radial Distribution Function (RDF), denoted as g(r), is a fundamental statistical measure that defines the probability of finding a particle at a distance r from another tagged particle. This function provides a crucial link between the microscopic details of atomic and molecular arrangements and macroscopic thermodynamic properties, serving as a powerful tool for characterizing material and liquid structures [2] [19]. In the context of drug development, the RDF effectively analyzes solvation structures by revealing solute-solvent interactions and the size and shape of solvation shells around drug molecules [24].

The coordination number, derived through integration of the RDF, quantifies the average number of nearest neighbors surrounding a central atom or molecule. This parameter offers profound insights into packing efficiency, bonding environments, and local ordering in systems ranging from simple liquids to complex biological molecules [2]. The calculation of coordination numbers from RDF integrals thus represents a critical analytical technique across scientific disciplines, providing a quantitative basis for understanding structural relationships that dictate material performance and drug behavior.

Theoretical Foundations of RDF Analysis

Mathematical Definition of the Radial Distribution Function

The radial distribution function g(r) defines the ratio between the local density at a distance r from a reference particle and the bulk density of the system. Mathematically, this relationship is expressed as:

[ g(r) = \frac{dnr}{dVr \cdot \rho} \approx \frac{dn_r}{4\pi r^2 dr \cdot \rho} ]

where (dnr) represents the number of particles in a spherical shell of thickness (dr) at distance (r), (dVr \approx 4\pi r^2 dr) is the volume of this spherical shell, and (\rho) is the bulk number density of the system [2].

The local density (\rho(r)) can be calculated from the RDF using the equation:

[ \rho(r) = \rho^{bulk} g(r) ]

This formulation allows researchers to quantify how molecular organization deviates from random distribution, revealing the structural order within the system [2].

Relating RDF to Coordination Numbers

The coordination number (CN), representing the average number of particles within a specific distance from a central particle, is obtained by integrating the RDF over a defined spatial range. For a one-component fluid, the coordination number between two species i and j is calculated as:

[ CN{ij} = 4 \pi \rhoj \int{r1}^{r2} r^2 g{ij}(r) dr ]

where (\rhoj) is the average number density of species j, and the integration limits (r1) to (r_2) typically span from 0 to the first minimum of the RDF [25]. This integral effectively sums the number of neighboring particles within a spherical shell defined by the chosen distance boundaries.

Table 1: Characteristic RDF Features and Coordination Numbers for Different States of Matter

| State of Matter | RDF Characteristics | Typical Coordination Number | Structural Information |

|---|---|---|---|

| Solids | Sharp, discrete peaks at specific distances [2] | Well-defined integer values (e.g., 12 for FCC) [2] | Long-range periodic order, exact atomic positions |

| Liquids | Damped oscillatory pattern with reducing peak amplitudes [2] | ~12 for simple liquids (e.g., argon) [2] | Short-range order, dynamic coordination spheres |

| Gases | Single coordination sphere rapidly decaying to g(r)=1 [2] | Minimal coordination | No long-range structure, random molecular distribution |

| Complex Liquids (e.g., water) | Sharper first peak at shorter distances [2] | 4-5 for water [2] | Directional bonding (hydrogen bonding) dictates packing |

Computational Methodologies for RDF Determination

Traditional Histogram-Based Approaches

Conventional methods for computing RDFs from molecular dynamics simulations rely on binning pair separations into histograms. This approach involves:

- Distance Calculation: Computing distances between all relevant particle pairs across simulation frames

- Bin Assignment: Sorting these distances into discrete bins of predetermined width

- Normalization: Normalizing bin counts by the expected number of particles in each shell volume for an ideal gas [19] [26]

The MDAnalysis package in Python implements this methodology through its InterRDF class, which calculates the RDF (g_{ab}(r)) between two groups of atoms a and b using the formula:

[ g{ab}(r) = (N{a} N{b})^{-1} \sum{i=1}^{Na} \sum{j=1}^{Nb} \langle \delta(|\mathbf{r}i - \mathbf{r}_j| - r) \rangle ]

where (Na) and (Nb) represent the number of atoms in each group, and the delta function counts pairs at specific separations [26].

Advanced Spectral Monte Carlo Methods

Despite four decades of research, histogram-based approaches remain standard despite significant limitations, including subjectivity in bin-size selection, high uncertainty, and slow convergence [19]. To address these issues, Spectral Monte Carlo (SMC) methods have been developed as a superior alternative.

The SMC approach expresses g(r) as an analytical series expansion:

[ g(r) \approx gM(r) = \sum{j=0}^{M} aj \phij(r) ]

where (\phij(r)) are orthogonal basis functions defined on the domain ([0, rc]), and the coefficients (a_j) are determined via Monte Carlo quadrature estimates [19]. This method offers:

- Reduced subjectivity through objective basis functions

- Significantly decreased noise in g(r)

- Faster convergence requiring fewer pair separations

- Differentiable formulas for g(r), enabling direct force-field calibration

SMC has demonstrated orders of magnitude improvement in efficiency compared to histogram-based methods, particularly benefiting applications like iterative Boltzmann inversion for coarse-grained force-field parameterization [19].

Figure 1: Computational workflow for deriving coordination numbers from molecular dynamics simulations, comparing traditional and advanced methods.

Experimental Protocols for RDF Determination

X-ray Diffraction for Structural Validation

Radial distribution functions obtained from X-ray diffraction data provide experimental validation for computational models. In studies of amorphous silicon and germanium, RDF analysis confirms tetrahedral coordination with first coordination numbers of 4 and second coordination numbers of 12, as found in crystalline phases [24]. The experimental protocol involves:

- Data Collection: Using powder X-ray diffraction to collect scattering intensity data across a range of angles

- Background Correction: Subtracting instrumental background and Compton scattering

- Normalization: Applying appropriate normalization procedures to account for sample absorption and polarization

- Fourier Transformation: Converting scattering data to real space via Fourier transformation to obtain the RDF

- Peak Analysis: Identifying peak positions and integrating areas to determine coordination numbers and bond distances [24]

This approach has proven particularly valuable in characterizing disordered materials like high-entropy alloys, where it helps identify deviations from ideal crystalline ordering [5].

Atom Probe Tomography for Local Structure Analysis

Atom probe tomography (APT) has emerged as a powerful technique for probing local atomic arrangements in complex alloys. The experimental workflow includes:

- Sample Preparation: Creating needle-shaped specimens with tip radii < 100 nm using focused ion beam milling

- Data Acquisition: Applying high voltage or laser pulses to field-evaporate ions from the specimen tip

- Position Detection: Recording the hit positions of ions on a delay-line detector with spatial resolution of 0.1-0.3 nm in depth and 0.3-0.5 nm laterally

- Mass-to-Charge Identification: Using time-of-flight mass spectrometry to identify elemental composition

- RDF Calculation: Generating pairwise RDFs from the 3D atomic coordinates [5]

Despite challenges including data sparsity (only ~⅓ of atoms are detected) and spatial uncertainty, APT can detect short-range ordering in materials like Ni₃Al with known L1₂ crystal structure, provided spatial uncertainty remains below 1.3 Å standard deviation [5].

Table 2: Comparison of Experimental Techniques for RDF Determination

| Technique | Spatial Resolution | Key Applications | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| X-ray Diffraction | ~1-2 Ã… (indirect) [24] | Bulk structure of crystalline and amorphous materials [24] | Provides spatially averaged information only [5] |

| Atom Probe Tomography | 0.1-0.3 nm depth, 0.3-0.5 nm lateral [5] | Local chemical ordering in complex alloys [5] | Data sparsity, spatial uncertainty, limited to conductive materials [5] |

| Neutron Scattering | ~1 Ã… | Light element detection, magnetic materials | Limited accessibility, requires large sample volumes |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational and Experimental Tools for RDF Analysis

| Tool/Reagent | Function/Role | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| GROMACS | Molecular dynamics simulation package with g_rdf utility [24] | Generating trajectory data for RDF calculation from MD simulations |

| MDAnalysis | Python library for analyzing MD simulation trajectories [26] | RDF calculation with customizable bin sizes and range parameters |

| Xmgrace | Graphing tool for visualizing RDF plots from g_rdf output [24] | Data visualization and integration of RDF peaks |

| LAMMPS | Large-scale Atomic/Molecular Massively Parallel Simulator [5] | MD simulations of complex systems including HEAs |

| Spectral Monte Carlo Code | Custom MATLAB scripts for SMC RDF calculation [19] | Advanced RDF computation with reduced noise and faster convergence |

| 2-(Aminooxy)-2-methylpropanoic acid | 2-(Aminooxy)-2-methylpropanoic Acid Supplier | High-purity 2-(Aminooxy)-2-methylpropanoic acid for RUO. Explore its role as a building block for bioorthogonal chemistry and protein labeling. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| 2-methylquinoline-6-sulfonic acid | 2-Methylquinoline-6-sulfonic Acid|CAS 93805-05-1 | 2-Methylquinoline-6-sulfonic acid is a key synthon for pharmaceuticals and material science. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

Applications in Materials Science and Drug Development

Characterizing Complex Alloys and Disordered Materials

RDF analysis with coordination number determination has proven invaluable in understanding the atomic-scale structure of complex materials. In high-entropy alloys (HEAs) containing five or more elements in roughly equal proportions, RDFs help identify short-range ordering and local compositional fluctuations that significantly impact mechanical properties [5]. For MCM-41 wall structures, RDF analysis between Si and O atoms revealed non-uniform coordination states distinct from the perfect tetrahedral coordination in MFI-type silicalite, demonstrating the method's sensitivity to local structural environments [24].

The development of Fractional Cumulative Radial Distribution Function (FCRDF) analysis has further enhanced our ability to visualize local compositions from short to medium range in complex structures. This approach has been successfully applied to both synthetic and experimental APT data sets for Ni₃Al and Alâ‚.₃CoCrCuFeNi, enabling researchers to correlate atomic ordering with material properties [5].

Solvation Structure Analysis in Pharmaceutical Research

In drug development, RDF analysis provides critical insights into solvation structures that influence drug solubility and formulation. The RDF between drug and solvent molecules reveals:

- Solvation Shell Structure: Identification of distinct solvation shells through characteristic peaks in g(r)

- Interaction Strengths: Peak intensities indicating the probability of finding solvent molecules at specific distances

- Coordination Environments: Integration of RDF peaks to determine how many solvent molecules typically surround a drug molecule in solution [24]

These analyses help pharmaceutical scientists understand how drug molecules interact with their solvent environment, guiding the selection of appropriate solvents and excipients for formulation development.

Ionic Liquid and Gas Absorption Studies