Benchmarking the GAFF Force Field: A Practical Guide for Predicting Molecular Diffusion in Drug Development

Accurate prediction of molecular diffusion coefficients is critical for modeling drug solubility, membrane permeability, and binding kinetics.

Benchmarking the GAFF Force Field: A Practical Guide for Predicting Molecular Diffusion in Drug Development

Abstract

Accurate prediction of molecular diffusion coefficients is critical for modeling drug solubility, membrane permeability, and binding kinetics. This article provides a comprehensive evaluation of the General AMBER Force Field (GAFF) for simulating diffusion, offering foundational knowledge, methodological protocols, and troubleshooting guidance. We explore GAFF's performance across diverse molecular systems—from small drug-like compounds to polymers—and present a rigorous validation against experimental data and other common force fields. Designed for researchers and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes current best practices to enhance the reliability of molecular dynamics simulations in biomedical research.

Understanding GAFF: Principles and Relevance for Diffusion Modeling

Core Philosophy of the General AMBER Force Field

The General AMBER Force Field (GAFF) is an academically developed force field designed to enable molecular simulations of a broad spectrum of organic molecules, with a primary application in computer-aided drug design (CADD) for studying receptor-ligand interactions [1]. Its core philosophy is to provide a general set of atom types and parameters that are compatible with the AMBER family of biomolecular force fields used for proteins, nucleic acids, and carbohydrates, thereby allowing seamless simulations of drugs and small molecule ligands in conjunction with biological macromolecules [2]. GAFF parameters cover virtually all molecules composed of the key elements found in organic and pharmaceutical chemistry: C, N, O, H, S, P, F, Cl, Br, and I [2].

A defining characteristic of GAFF's philosophy is its parameterization strategy. Unlike specialized biomolecular force fields, GAFF aims for transferability across diverse chemical space. Its parameters, particularly for van der Waals interactions and bonded terms, were initially calibrated against experimental data for pure liquid properties, such as density and heat of vaporization, ensuring a solid foundation for describing bulk molecular behavior [3] [1]. The force field employs a fixed-point charge model, and its intended level of accuracy, in terms of molecular geometry and energies, is considered on par with or better than other general force fields like MMFF94 [2]. This robust and generalist design makes GAFF a widely adopted tool, cited thousands of times in the scientific literature [1].

Performance Assessment: Diffusion Coefficients

The performance of a force field is critically assessed by its ability to reproduce experimental observables, with diffusion coefficients (D) being a key dynamic property. Research has systematically evaluated GAFF's performance in predicting diffusion coefficients across various systems, revealing both its strengths and limitations [3].

Quantitative Performance of GAFF

The table below summarizes the quantitative performance of GAFF in predicting diffusion coefficients for different types of systems, as reported in a foundational study [3].

Table 1: Performance of GAFF in Predicting Diffusion Coefficients for Various Systems

| System Category | Number of Systems Tested | Performance Metrics | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|

| Organic Solutes in Aqueous Solution | 5 | AUE = 0.137 ×10â»âµ cm²sâ»Â¹RMSE = 0.171 ×10â»âµ cm²sâ»Â¹ | Well-predicted absolute values [3]. |

| Proteins in Aqueous Solution | 4 | R² = 0.996 | Excellent correlation with experimental data [3]. |

| Organic Solutes in Non-Aqueous Solutions | 9 | R² = 0.834 | Good correlation with experimental data [3]. |

| Organic Solvents | 8 | R² = 0.784 | Good correlation with experimental data [3]. |

These results demonstrate that while GAFF can predict absolute diffusion coefficients accurately for some systems like aqueous organic solutes, it excels in capturing relative trends and correlations across diverse systems, including proteins and organic solvents. This indicates that GAFF is highly reliable for comparative studies.

Challenges in Transport Property Prediction

Despite its successes, accurately predicting transport properties, including self-diffusion coefficients and shear viscosity, remains a challenge for GAFF and other classical force fields. A recent 2025 study on tri-n-butyl phosphate (TBP) highlighted that while thermodynamic properties like mass density and heat of vaporization can be accurately predicted, transport properties are systematically under-predicted [4]. For instance, the best prediction for TBP's self-diffusion coefficient still deviated by -17.4% from the experimental value, a trend observed across both non-polarized and more complex polarized force fields [4]. This indicates a general area for future improvement in force field parameterization.

Methodological Protocols for Diffusion Coefficient Calculation

A critical aspect of obtaining reliable diffusion data from simulations is the use of robust and efficient protocols.

Theoretical Foundation

In molecular dynamics simulations, the diffusion coefficient (D) is most commonly calculated using the Einstein relation, which relates D to the mean squared displacement (MSD) of particles over time [3]:

$$ \langle | \vec{r}(t) - \vec{r}(0) |^2 \rangle = 2nDt $$

Here, ( \langle | \vec{r}(t) - \vec{r}(0) |^2 \rangle ) is the MSD, n is the dimensionality (typically 3 for 3D simulations), t is time, and D is the diffusion coefficient. The slope of a linear fit of the MSD versus time plot yields the diffusion coefficient (D = slope / (2n)) [3]. Alternatively, the Green-Kubo relation, which integrates the velocity autocorrelation function, can be used and is theoretically equivalent to the Einstein approach [3].

An Efficient Sampling Strategy

A significant challenge in calculating diffusion coefficients for solutes at infinite dilution is the poor convergence from single, long MD trajectories due to limited sampling [3]. To address this, an efficient sampling strategy has been proposed and validated for GAFF simulations [3].

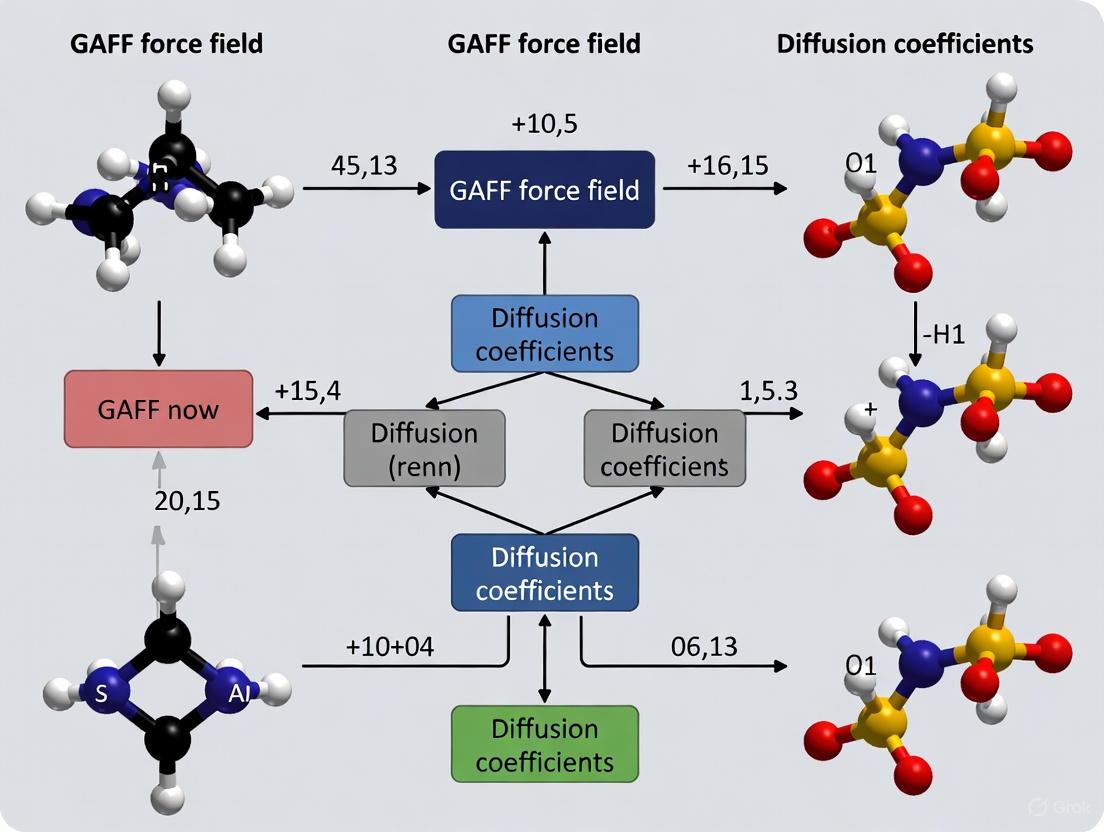

The workflow below illustrates this multi-trajectory approach for robust calculation of diffusion coefficients:

Diagram 1: Multi-trajectory sampling workflow for calculating diffusion coefficients.

This strategy involves running multiple short, independent MD simulations (or multiple copies of the solute in one box) instead of one extremely long simulation [3]. The MSDs collected from each simulation are then averaged, and this averaged MSD is used for the linear fit to calculate D. This method has been shown to be efficient and reliable for predicting diffusion coefficients of solutes at infinite dilution, overcoming the convergence problems inherent in single-trajectory approaches [3].

Parameterization and the Scientist's Toolkit

The practical application of GAFF requires specific tools and reagents to generate the necessary input files for molecular dynamics simulations.

The Parameterization Workflow

The standard protocol for parameterizing a small molecule ligand for use with GAFF involves several key steps and software tools, primarily within the AMBER tools ecosystem [5]. The following diagram outlines this workflow, from an initial molecular structure to a fully parameterized molecule ready for simulation.

Diagram 2: Ligand parameterization workflow using AMBER tools.

Research Reagent Solutions

The table below details the essential "research reagents" — the key software tools and parameters — required to implement the GAFF force field for molecular simulations.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for GAFF Simulations

| Tool / Parameter | Category | Function and Description |

|---|---|---|

| ANTECHAMBER | Software Module | An automated tool for quickly generating topology files for small molecules. It assigns GAFF atom types and calculates partial charges [5]. |

| AM1-BCC | Charge Model | A fast, semi-empirical method for calculating atomic partial charges, designed to approximate the HF/6-31G* RESP charges without expensive QM calculations [1] [5]. |

| GAFF2 Dat File | Force Field Parameters | The parameter file (e.g., gaff2.dat) containing the core force field terms—bond, angle, dihedral, and non-bonded parameters—for GAFF2 atom types [5]. |

| parmchk2 | Software Module | Checks the .mol2 file for bonds, angles, and dihedrals with missing force field parameters and generates a .frcmod file with suggested values, often by analogy to existing parameters [5]. |

| LEaP | Software Module | The AMBER module that integrates the .mol2 and .frcmod files with the GAFF parameters to create the final, simulation-ready topology (.prmtop) and coordinate (.inpcrd) files [5]. |

| 3-Hydroxyphenazepam | 3-Hydroxyphenazepam | |

| 1-Methylindole | 1-Methylindole|High-Purity Reagent for Research | 1-Methylindole for advanced research in hydrogen storage, pharmaceutical intermediates, and chemical synthesis. This product is for research use only (RUO). |

Advanced Topics and Future Directions

The Critical Role of Partial Charges

The assignment of partial atomic charges is a crucial step in GAFF parameterization, significantly influencing the accuracy of properties like solvation free energy and, by extension, binding affinity predictions [1]. While GAFF was originally developed with RESP charges derived from quantum mechanics (QM), the AM1-BCC method is widely used in practice for its efficiency and good performance [1]. Recent research focuses on refining these charge models. For example, the development of the ABCG2 model, a new set of AM1-BCC parameters optimized for GAFF2, has demonstrated a substantial improvement in predicting hydration free energies (reducing the mean unsigned error from 1.03 kcal/mol to 0.37 kcal/mol) and solvation free energies in various organic solvents [1]. This highlights an ongoing effort to enhance GAFF's transferability across different dielectric environments.

Specialized Force Fields and GAFF's Role

While GAFF is a powerful general-purpose force field, specific research areas with unique molecular structures, such as mycobacterial membranes, require specialized parameter sets. This has led to the development of dedicated force fields like BLipidFF, which uses a modular QM-based parameterization strategy for complex bacterial lipids [6]. These specialized force fields often build upon the philosophy and frameworks of general force fields like GAFF. For instance, BLipidFF adopts bond and angle parameters from GAFF where appropriate but performs higher-level torsion parameter optimization and charge derivation to capture the specific physics of the target molecules [6]. This trend shows how GAFF serves as a foundation upon which more specialized, high-accuracy models are constructed.

The core philosophy of the General AMBER Force Field is to provide a transferable, computationally accessible, and broadly applicable parameter set for organic molecules, ensuring compatibility with the well-established AMBER biomolecular force fields. Its performance in predicting dynamic properties like diffusion coefficients is robust for identifying trends and correlations across a wide range of systems, though absolute prediction of transport properties remains a challenge. The continued evolution of its associated tools, particularly in charge model development, and its role as a foundation for more specialized force fields, ensure that GAFF will remain a cornerstone tool for computational researchers in drug development and molecular science.

The Critical Link Between Force Field Accuracy and Diffusion Coefficients

In drug development and materials science, accurately predicting molecular diffusion is critical for understanding phenomena ranging from cellular uptake to solvent extraction processes. Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations serve as a powerful tool for probing these molecular-level interactions, but their predictive accuracy hinges entirely on the empirical potential functions, or force fields, that govern atomic interactions. The General AMBER Force Field (GAFF) is widely used for simulating small organic molecules and drug-like compounds. This Application Note examines the critical link between GAFF's parametrization and its accuracy in predicting diffusion coefficients, providing a structured framework for researchers to validate and optimize force field performance for transport property calculations.

Comparative Performance of Force Fields

Extensive benchmarking studies reveal how different force fields, including GAFF, reproduce experimental diffusion data across various molecular systems. The table below summarizes key performance comparisons:

Table 1: Force Field Performance for Diffusion Coefficient Prediction

| Force Field | System Studied | Performance for Diffusion | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| GAFF | Polyethylene glycol (PEG) oligomers | Excellent agreement with experimental data [7] | For PEG tetramer: density within 5%, diffusion coefficient within 5%, viscosity within 10% of experimental values [7] |

| OPLS | Polyethylene glycol (PEG) oligomers | Significant deviations from experimental data [7] | Deviations exceeding 80% for diffusion coefficient and 400% for viscosity for PEG tetramer [7] |

| GAFF | Urea crystals and aqueous solutions | Good overall performance after charge optimization [8] | Specific urea charge-optimized GAFF version identified as one of the two best-performing force fields [8] |

| OPLS-AA | Ethanol and protic solutes | Overestimation of diffusivities [9] | Required reparameterization of oxygen diameter from 0.312 nm to 0.306 nm to improve accuracy [9] |

| Polarized vs Non-polarized | Tri-n-butyl phosphate (TBP) | Systematic underpredictions for all models [4] | Best prediction for self-diffusion coefficient still deviated -17.4% from experimental values [4] |

The performance variations stem from fundamental parametrization differences. For instance, in PEG oligomers, GAFF's superior performance is attributed to its balanced parametrization of partial charges and dihedral angles that more accurately capture the molecular flexibility and intermolecular interactions governing diffusion [7]. The significant OPLS deviations for the same system highlight how seemingly small parametrization differences can dramatically impact transport property predictions.

Experimental Protocols for Force Field Validation

Workflow for Diffusion Coefficient Calculation

The following diagram illustrates the standardized protocol for calculating and validating diffusion coefficients using MD simulations:

Protocol Implementation Details

System Preparation:

- Molecular Structure: Obtain initial coordinates from crystal structures or quantum chemical geometry optimization. For urea simulations, the crystal structure provides a reliable starting point [8].

- Force Field Parametrization: Assign parameters using GAFF. Pay particular attention to partial charge derivation methods (AM1-BCC, RESP) as these significantly impact diffusion predictions. Charge-optimized versions of GAFF showed markedly improved performance for urea systems [8].

Simulation Parameters:

- Ensemble Selection: Use NPT ensemble for equilibration to maintain constant number of particles, pressure, and temperature, ensuring proper density.

- Temperature and Pressure Control: Employ standard thermostats (e.g., Nosé-Hoover) and barostats (e.g., Parrinello-Rahman) with coupling constants appropriate for organic molecular systems.

- Integration Time Step: Use 1-2 fs time steps with constraints on bonds involving hydrogen atoms.

- Simulation Duration: Conduct production runs long enough to obtain reliable mean-squared displacement (MSD) statistics (typically 50-100 ns for small molecules).

Diffusion Coefficient Calculation:

- Trajectory Processing: Remove center-of-mass motion and correct for periodic boundary effects.

- Mean-Squared Displacement: Calculate MSD from particle trajectories using the equation: ⟨r²(t)⟩ = (1/N)Σᵢ[rᵢ(t) - rᵢ(0)]², where N is the number of particles, and rᵢ(t) is the position of particle i at time t.

- Einstein Relation: Determine the diffusion coefficient (D) from the slope of the MSD versus time plot: D = (1/6) × lim(t→∞) d⟨r²(t)⟩/dt.

Validation Metrics:

- Quantitative Comparison: Compute percentage deviations from experimental diffusion coefficients: % Deviation = 100% × (Dcalculated - Dexperimental)/D_experimental.

- Statistical Analysis: Assess reproducibility across multiple simulation replicates and different initial conditions.

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools for Force Field Development and Validation

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function in Force Field Research |

|---|---|---|

| MD Simulation Packages | GROMACS [10], LAMMPS [7], AMBER [8] | Engine for running molecular dynamics simulations and calculating trajectories |

| Force Field Parametrization | GAFF [8] [7], GAFF2 [10], OPLS-AA [9] | Provides empirical parameters governing molecular interactions |

| Quantum Chemistry Software | Gaussian [6] [11], Multiwfn [6] | Calculates reference data for force field parametrization (e.g., RESP charges) |

| Analysis Tools | Built-in analysis suites, VMD, MDAnalysis | Processes MD trajectories to extract diffusion coefficients and other properties |

| Validation Metrics | Experimental diffusion databases, Thermodynamic property databases | Provides benchmark data for force field validation and refinement |

Advanced Parametrization Strategies

Charge Optimization Techniques

The assignment of partial atomic charges represents a critical step in force field parametrization with profound implications for diffusion coefficient accuracy:

RESP Charges: The Restricted Electrostatic Potential method, derived from quantum mechanical calculations, provides superior charge distributions compared to simpler automated methods. In bacterial membrane lipid simulations, RESP charges calculated at the B3LYP/def2TZVP level enabled accurate prediction of lateral diffusion coefficients matching experimental FRAP measurements [6].

Charge Validation: Implement a multi-conformer approach for charge derivation by calculating RESP charges for multiple molecular conformations and using averaged values to enhance transferability across different molecular environments [6].

Targeted Parameter Refinement

When standard GAFF parametrization yields unsatisfactory diffusion predictions, targeted refinement of specific parameters may be necessary:

Lennard-Jones Optimization: For ethanol systems using OPLS-AA, refining the oxygen atom diameter from 0.312 nm to 0.306 nm significantly improved diffusion coefficients for protic solutes, reducing deviations from >25% to <5% [9].

Torsional Parameter Refinement: In highly symmetric host-guest systems, minute adjustments to torsional potentials involving key functional groups (e.g., phenoxyacetic moieties) can dramatically impact binding affinity predictions by altering host flexibility and guest accessibility [10].

The accurate prediction of diffusion coefficients using GAFF depends critically on thoughtful parametrization and systematic validation. While GAFF demonstrates excellent performance for many organic molecular systems, including PEG oligomers and properly parametrized urea systems, its accuracy diminishes for specific molecular classes requiring targeted parameter optimization. Researchers should implement the standardized validation protocols outlined herein, paying particular attention to charge derivation methods and empirical parameter refinement when diffusion predictions deviate from experimental benchmarks. As force field development continues advancing, with emerging approaches explicitly incorporating polarization effects, the fundamental link between parametrization choices and transport property accuracy remains essential for reliable molecular simulations in pharmaceutical and materials research.

Key Molecular Interactions Governing Diffusion in GAFF

The accurate prediction of diffusion coefficients is paramount for advancing research in drug design, chemical engineering, and materials science, as diffusion governs critical processes from protein aggregation to mass transfer in industrial applications [3]. Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations serve as an essential tool for investigating these processes at an atomic level. The predictive accuracy of MD, however, is fundamentally reliant on the potential energy functions, or force fields, employed to model atomic interactions [6]. The General AMBER Force Field (GAFF) is widely used for studying small organic molecules and their interactions with biomolecular systems [8] [3]. This application note, framed within a broader thesis evaluating GAFF's performance, details the key molecular interactions governing diffusion coefficients and provides validated protocols for their calculation. We focus on the interplay between van der Waals interactions, electrostatic forces, and bonded parameters, and their collective impact on predicting dynamic properties.

Quantitative Performance of GAFF for Diffusion Coefficients

Evaluations of GAFF reveal a nuanced performance in predicting diffusion coefficients, with high accuracy for certain systems and notable deviations for others. The force field's performance is often benchmarked against other common force fields like OPLS-AA, CHARMM36, and COMPASS.

Table 1: Performance of GAFF for Diffusion Coefficients in Different Systems

| System Category | Performance Summary | Quantitative Deviation | Comparative Force Field Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Organic Solutes in Aqueous Solution | Well-predicted [3] | AUE: 0.137 ×10â»âµ cm²sâ»Â¹; RMSE: 0.171 ×10â»âµ cm²sâ»Â¹ [3] | Not provided in source |

| Pure Organic Solvents | Good correlation with experiment [3] | R² = 0.784 (8 solvents) [3] | Not provided in source |

| Proteins in Aqueous Solution | Excellent correlation [3] | R² = 0.996 (4 proteins) [3] | Not provided in source |

| Organic Compounds in Non-Aqueous Solutions | Good correlation [3] | R² = 0.834 (9 compounds) [3] | Not provided in source |

| Diisopropyl Ether (DIPE) Liquid Membranes | Overestimates density and viscosity [12] | Density: +3-5%; Viscosity: +60-130% [12] | CHARMM36 & COMPASS more accurate [12] |

A study assessing GAFF for 17 solvents, various organic compounds, and proteins found that while absolute values for some systems may be challenging to predict, the force field achieves strong correlations with experimental diffusion data across diverse environments [3]. This suggests GAFF reliably captures the relative trends and physical chemistry underlying diffusion processes. However, its performance can be system-dependent. For instance, in modeling liquid membranes of diisopropyl ether (DIPE), GAFF overestimated both density and shear viscosity, a finding that underscores the importance of force field validation for specific application domains [12].

Molecular Interactions Governing Diffusion in GAFF

The diffusion coefficient, calculated from the mean squared displacement (MSD) via the Einstein relation (( \langle |\vec{r} - \vec{r_0}|^2 \rangle = 2nDt )), is a macroscopic observable that emerges from the ensemble of microscopic molecular interactions parameterized within the force field [3]. In GAFF, these interactions are primarily governed by a combination of non-bonded and bonded terms.

Non-Bonded Interactions

- Van der Waals (Lennard-Jones) Interactions: These interactions, parameterized for atom types in GAFF, critically influence molecular packing and friction. The Lennard-Jones parameters (equilibrium distance σ and well depth ε) dictate the excluded volume and the energy required to separate molecules during diffusion. Inaccurate LJ parameters can lead to significant errors in bulk properties like density and viscosity, as seen in the DIPE study, which directly impacts the predicted diffusion rates [12].

- Electrostatic Interactions: Partial atomic charges, often derived using the AM1-BCC method in GAFF, determine the strength of intermolecular hydrogen bonding and dipole-dipole interactions [8]. For protic solutes and solvents, these interactions are crucial. Force field variants with re-optimized charges (e.g., using RESP fits for specific molecules like urea) have demonstrated improved performance, highlighting the sensitivity of diffusion to electrostatic representation [8] [9]. Strong, directional hydrogen bonds can transiently "trap" molecules, reducing their diffusion coefficient, and must be accurately captured.

Bonded Terms and Parametrization Sensitivity

While non-bonded interactions are dominant, bonded terms—especially torsion potentials—can indirectly influence diffusion by affecting molecular conformation and flexibility. Seemingly small differences in torsion parameterization can produce systematic structural effects with a significant impact on calculated properties [10]. For example, in highly symmetric host molecules, tiny errors in a single symmetry-related torsional potential can be amplified, altering the host's cavity geometry and its interaction with guest molecules, thereby affecting binding affinities and the correlated diffusion of complexes [10].

Experimental Protocol for Calculating Diffusion Coefficients

This protocol details the steps for calculating the diffusion coefficient of a solute at infinite dilution in a solvent using GAFF and molecular dynamics simulations.

System Setup

- Force Field Selection and Parameterization:

- Obtain GAFF parameters (Lennard-Jones, bonds, angles, torsions) for the solute and solvent molecules using tools like

Antechamber[8]. - Assign partial atomic charges to the solute. The AM1-BCC method is the default and is recommended for broad compatibility with GAFF [8]. For specific applications, consider deriving charges using the RESP method based on HF/6-31G* electrostatic potentials for potentially improved accuracy [8].

- Obtain GAFF parameters (Lennard-Jones, bonds, angles, torsions) for the solute and solvent molecules using tools like

- Solvation and Neutralization:

- Place a single solute molecule in the center of a simulation box.

- Solvate the system with an appropriate number of solvent molecules (e.g., TIP3P water model). The box size should be large enough to ensure the solute does not interact with its own periodic images. A minimum distance of 12-15 Ã… between the solute and the box edge is a typical starting point [10].

- For charged solutes, add a sufficient number of counter-ions (e.g., Na⺠or Clâ») to neutralize the system. The placement of explicit ions is preferred over a uniform neutralizing plasma to more realistically model the ionic strength [10].

Simulation Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the complete workflow for calculating diffusion coefficients.

Data Analysis

- Trajectory Processing: Ensure the MD trajectory is "unwrapped" to account for molecules crossing periodic boundaries, which is essential for a correct MSD calculation [3].

- Mean Squared Displacement (MSD) Calculation:

- From the production trajectory, calculate the MSD of the solute's center of mass. The MSD is defined as ( \langle |\vec{r}(t) - \vec{r}(0)|^2 \rangle ), where the angle brackets denote an average over all possible time origins [3].

- For a single solute molecule, improve sampling by averaging MSDs from multiple, independent short simulations if one long simulation provides poor statistics [3].

- Diffusion Coefficient Estimation:

- Plot the MSD as a function of time. In the diffusive regime (typically after an initial ballistic regime), the MSD will be linear with time.

- Perform a linear least-squares fit to the MSD curve in the diffusive regime (e.g., from 1 ns to the end of the simulation).

- Calculate the diffusion coefficient ( D ) using the Einstein relation for 3-dimensional diffusion: ( D = \frac{1}{6} \times \text{slope} ).

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Item Name | Function/Brief Explanation |

|---|---|

| GAFF & GAFF2 | The core force fields providing parameters for small organic molecules; GAFF2 includes updated bonded and non-bonded terms [8]. |

| AM1-BCC Charge Model | A efficient and widely used method for deriving partial atomic charges, compatible with GAFF [8]. |

| RESP Charge Model | An alternative charge model based on HF/6-31G* electrostatic potentials; can offer improved accuracy for specific molecules [8]. |

| TIP3P Water Model | A common 3-site water model used for solvating systems in GAFF simulations [8]. |

| Antechamber | A tool for automatically generating GAFF force field parameters and charges for organic molecules [8]. |

| Particle Mesh Ewald (PME) | The standard method for handling long-range electrostatic interactions under periodic boundary conditions [10]. |

Common Drug-like Molecules Successfully Modeled with GAFF

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations are a pivotal tool in computational drug discovery, providing atomistic-level insights into the dynamical behaviors and physical properties of molecular systems [13]. The accuracy of these simulations fundamentally relies on the force field—a mathematical model that describes the potential energy surface of a system [14]. Among the available force fields, the Generalized AMBER Force Field (GAFF) has been widely adopted for modeling small drug-like molecules due to its design for broad applicability across organic and pharmaceutical compounds [8] [14].

This Application Note collates evidence of GAFF's successful application in modeling common drug-like molecules, with a specific focus on its performance in predicting diffusion coefficients and related solution properties. We provide validated protocols and resources to assist researchers in employing GAFF for accurate molecular simulations.

Extensive validation studies demonstrate that GAFF performs robustly in predicting thermodynamic and transport properties for a wide range of drug-like molecules. The table below summarizes key quantitative data on its performance.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of GAFF for Drug-like Molecules

| Property Measured | System / Molecule Type | Level of Agreement with Experiment | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Osmotic Coefficients [15] | 16 diverse drug-like molecules | Good agreement for most molecules | GAFF, CGenFF, and OPLS-AA produced satisfactory results, while PRODRGFF often performed poorly. |

| Absolute Hydration Free Energy (HFE) [14] | >600 molecules (FreeSolv dataset) | Generally accurate, with specific functional group errors | GAFF and CGenFF are generally equally accurate. GAFF under-solubilizes nitro-groups and over-solubilizes carboxyl groups. |

| Crystal & Solution Properties [8] | Urea | Good overall reproduction | A charge-optimized GAFF variant was one of the two best-performing force fields for urea crystallization studies. |

| Diffusion Coefficients [16] | Small organics and drug-like molecules in water | Recovered empirical Wilke–Chang correlation | GAFF-based MD can be used to compute diffusion coefficients, validating its use for transport properties. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Calculating Diffusion Coefficients

Accurate calculation of diffusion coefficients using GAFF requires careful system setup and simulation control. The following protocol is adapted from established methodologies [17] [16].

1. System Setup and Parameterization

- Force Field Assignment: Assign GAFF parameters (bond, angle, torsion, van der Waals) to the solute (drug-like molecule). The AM1-BCC charge model is recommended for generating partial atomic charges [8] [14].

- Solvation: Solvate the single solute molecule in a cubic box of explicit water molecules. The TIP3P water model is a common and compatible choice [8] [14].

- Box Size: Ensure a minimum distance of 14 Ã… between the solute and the box edge in all directions to avoid periodicity artifacts [14]. This typically results in a box side length of approximately 40 Ã… for a single small molecule.

- Neutralization and Ionic Strength: Add ions (e.g., Naâº, Clâ») to neutralize the system's net charge and to match the experimental ionic strength (e.g., 0.2 M for PBS buffer) [10]. The number of ions

nfor a target ionic strength in a cubic box of side-lengthL(in Å) can be estimated using the formula provided in search results:Ionic Strength (M) ≈ n / (2 * 1661 ų/M * L³)[10].

2. Simulation Parameters

- Periodic Boundary Conditions (PBC): Apply PBC in all three dimensions.

- Electrostatic Treatment: Use the Particle Mesh Ewald (PME) method for long-range electrostatics [10].

- Van der Waals Treatment: Set a cutoff between 10-12 Ã… for non-bonded interactions [14].

- Temperature and Pressure Control: Use a thermostat (e.g., Nosé-Hoover) to maintain temperature at 300 K and a barostat (e.g., Parrinello-Rahman) to maintain pressure at 1 bar.

- Integration Time Step: Use a 1-2 fs time step, with constraints applied to bonds involving hydrogen atoms.

3. Production Simulation and Analysis

- Equilibration: Equilibrate the system first in the NVT ensemble, followed by the NPT ensemble, until system properties (density, potential energy) are stable.

- Production Run: Perform a long production MD simulation (typically 10-100 ns, depending on solute size and diffusivity) in the NPT ensemble.

- Trajectory Analysis: Calculate the self-diffusion coefficient

Dfrom the production trajectory using the Einstein relation, which relates the mean squared displacement (MSD) of the solute to time:⟨r²(τ)⟩ = 6Dτwhere⟨r²(τ)⟩is the ensemble-averaged MSD over time intervalτ. The diffusion coefficientDis obtained from the slope of the linear region of the MSD vs. time plot [16].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the key stages of this protocol:

Protocol for Validating with Hydration Free Energy (HFE) Calculation

Hydration Free Energy is a critical property for validating force field performance for drug-like molecules [14]. The following alchemical free energy protocol can be implemented in software packages like CHARMM/OpenMM.

1. System Setup

- Prepare the solute molecule with GAFF parameters and AM1-BCC charges.

- Create two simulation systems: one with the solute in a vacuum (gas phase) and another with the solute solvated in a TIP3P water box (aqueous phase).

2. Alchemical Transformation

- Use a thermodynamic cycle to annihilate the solute's non-bonded interactions (both electrostatic and van der Waals) in both the vacuum and aqueous phases.

- Employ a hybrid Hamiltonian

H(λ) = λHâ‚€ + (1-λ)Hâ‚, whereHâ‚€andHâ‚are the Hamiltonians of the fully interacting and non-interacting states, respectively. The coupling parameterλis varied from 0 to 1 in multiple steps (e.g., 12-20 λ windows) [14].

3. Free Energy Calculation

- Run simulations at each λ window in both phases.

- Calculate the free energy difference for annihilation in vacuum (ΔGvac) and in solvent (ΔGsolvent) using methods such as the Multistate Bennett Acceptance Ratio (MBAR) or Thermodynamic Integration (TI).

- Compute the absolute HFE using the formula:

ΔG_hydr = ΔG_vac - ΔG_solvent[14].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for GAFF Simulations

| Tool / Reagent | Function / Description | Example Use in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| GAFF & GAFF2 | General small molecule force field providing parameters for bonds, angles, torsions, and van der Waals interactions. | Primary force field for parameterizing the drug-like molecule [8] [14]. |

| AM1-BCC Charge Model | A rapid charge model that reproduces HF/6-31G* electrostatic potentials. | Default method for assigning partial atomic charges in GAFF [8] [14]. |

| TIP3P Water Model | A 3-site transferable intermolecular potential water model. | Standard solvent for solvating the system in GAFF simulations [8] [14]. |

| Particle Mesh Ewald (PME) | An algorithm for efficient computation of long-range electrostatic interactions under PBC. | Treatment of electrostatics during MD simulation to achieve accuracy [10]. |

| Alchemical Free Energy Tools | Software modules (e.g., CHARMM/BLOCK, OpenMM) for performing non-physical transformation calculations. | Calculating Hydration Free Energies for force field validation [14]. |

| Mean Squared Displacement (MSD) Analyzer | A standard trajectory analysis tool included in packages like GROMACS and MDAnalysis. | Calculating the diffusion coefficient from the production MD trajectory [16]. |

| 3-Butyn-1-OL | 3-Butyn-1-ol|97% Purity|CAS 927-74-2 | |

| Stearyl Stearate | Stearyl Stearate, CAS:2778-96-3, MF:C36H72O2, MW:537.0 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The Generalized AMBER Force Field (GAFF) has proven to be a reliable and accurate tool for modeling a wide spectrum of drug-like molecules. Validation against experimental data for osmotic coefficients, hydration free energies, and diffusion coefficients confirms its robustness for molecular dynamics simulations in drug discovery. The detailed protocols and resources provided in this note equip researchers with the methodologies to effectively leverage GAFF for predicting key physicochemical properties, including diffusion, thereby supporting more accurate and insightful computational analyses.

Practical Protocols: Setting Up GAFF Simulations for Diffusion

Workflow for Parameterizing Small Molecules with GAFF

Molecular mechanics force fields are fundamental to computational chemistry, enabling the simulation of biomolecular systems and drug-like molecules at a scale that would be prohibitively expensive with quantum mechanical methods [18]. The General AMBER Force Field (GAFF) is a widely used general force field designed for small organic molecules. However, its performance and accuracy are intrinsically tied to the quality of its parameterization [19]. In the context of researching diffusion coefficients, an improperly parameterized molecule can lead to systematic errors in predicted dynamic properties [3]. This application note details a structured workflow for parameterizing small molecules with GAFF, providing protocols to help researchers obtain reliable parameters for subsequent molecular dynamics simulations, with a specific focus on applications involving diffusion.

The Parameterization Workflow

A robust parameterization workflow is essential for generating accurate and transferable parameters. The following diagram outlines the key stages, from initial structure preparation to final validation.

Structure Preparation and Geometry Optimization

The initial stage involves preparing a high-quality input structure, as this serves as the foundation for all subsequent parameter derivation.

- Initial Structure Generation: Obtain a 3D molecular structure from a database (e.g., PubChem) or use a molecular builder tool like Avogadro or ChemDraw.

- Geometry Optimization: Perform a quantum mechanical (QM) geometry optimization at an appropriate level of theory (e.g., HF/6-31G* or B3LYP/6-31G*) to relax the structure to its equilibrium geometry. This step is crucial for obtaining accurate starting bond lengths and angles [19]. The optimized structure should be saved in a format such as MOL2 or PDB.

Assignment of Partial Charges

Electrostatic interactions are primarily governed by partial atomic charges. The charge model must be consistent with the force field.

- Recommended Method: Use the AM1-BCC (Austin Model 1 with Bond Charge Corrections) method. This is a fast, semi-empirical approach that is the de facto standard for assigning charges with GAFF in high-throughput studies [20].

- Alternative for Higher Accuracy: For improved accuracy in solvation free energy calculations, the ABCG2 charge model can be used with GAFF2. This adjusted BCC model has demonstrated a mean unsigned error (MUE) of only 0.37 kcal/mol for hydration free energies [20].

- Toolkit: The

antechambertool, part of the AMBER suite, can automatically assign GAFF atom types and AM1-BCC charges.

Assignment of Bonded Parameters

Bonded parameters (bonds, angles, dihedrals) are assigned based on GAFF's atom types.

- Automated Atom Typing: Use

antechamberto assign GAFF atom types to each atom in the molecule based on its local chemical environment [21]. Theparmchk2tool is then used to generate force field parameters for any missing bonds, angles, or dihedrals by analogy to existing parameters. - Limitation of Indirect Perception: Be aware that GAFF uses indirect chemical perception, where parameters are assigned via atom types. This can sometimes lead to a proliferation of parameters and difficulty in recognizing chemically equivalent interactions [21]. For example, carbon atoms in identical chemical environments may be assigned different atom types to account for different bond orders in the connectivity [21].

Specific Dihedral Refinement

Standard dihedral parameters may not capture complex electronic effects, necessitating targeted refinement.

- Identify Problematic Torsions: For torsions central to molecular flexibility (e.g., in drug-like molecules or around furanose rings), compare the conformational energy profile from GAFF against a QM benchmark (e.g., DFT calculations) [19].

- Refinement Protocol:

- Perform a QM torsion scan, rotating the dihedral angle in steps.

- Calculate the single-point energy at each step.

- In the molecular dynamics engine, adjust the torsional force constants (

pk) and phase offsets (phase) in the dihedral term to reproduce the QM energy profile as closely as possible [19].

- Advanced Tools: Consider using modern tools like ParametrizANI, which leverages machine learning (TorchANI) to perform dihedral parametrization with DFT-level accuracy more efficiently [22].

Quantitative Performance of GAFF

The table below summarizes the performance of GAFF in key validation tests, highlighting both its general utility and specific areas where improvement is often needed.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of GAFF in Key Validation Tests

| Validation Metric | GAFF Performance Result | Comparative Context | Key Finding / Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conformational Energy Correlation | MM Energy = 0.731 × QM Energy (R² = 0.864) [19] | A refined parameter set (sugar_mod) achieved a near 1:1 correlation (0.973 × QM) [19] |

GAFF tends to systematically underestimate QM energies; targeted reparameterization is highly effective. |

| Hydration Free Energy (HFE) | Original AM1-BCC shows systematic errors for some functional groups (e.g., alcohols) [20] [21] | The updated ABCG2 model with GAFF2 reduced MUE to 0.37 kcal/mol [20] | The choice of charge model is critical for accurate solvation properties. |

| Diffusion Coefficient (D) Prediction | Good correlation (R² = 0.834) for organic solutes in non-aqueous solutions [3] | AUE of 0.137 ×10â»âµ cm²/s for organic solutes in aqueous solution [3] | GAFF is suitable for predicting relative diffusion trends, though absolute values may require careful validation. |

| Geometric Differences (TFD) | 268,830 difference flags vs. SMIRNOFF99Frosst [18] | MMFF94/MMFF94S pair had only 10,048 flags, indicating high similarity [18] | Different force fields can yield significantly different optimized geometries for the same molecule. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Software

The following table lists key software tools and resources essential for implementing the GAFF parameterization workflow.

Table 2: Essential Software Tools for GAFF Parameterization

| Tool / Resource Name | Primary Function | Role in the Workflow |

|---|---|---|

AMBER Tools Suite (esp. antechamber, parmchk2) |

Automates GAFF atom typing, charge assignment, and parameter file generation [3]. | The core toolkit for steps 2 and 3 of the workflow, generating the initial molecular topology file. |

| ParametrizANI | Performs dihedral parametrization using machine learning models for DFT-level accuracy [22]. | A research-friendly tool for the dihedral refinement step (4), significantly speeding up the process. |

| GAFF Force Field | Provides the foundational set of bonded and non-bonded parameters for small organic molecules [20]. | The source of the initial parameters. Its performance is the baseline against which refinements are measured. |

| Quantum Chemistry Software (e.g., Gaussian, ORCA) | Performs geometry optimization and torsion scans to generate high-quality reference data [19]. | Critical for the structure preparation (1) and dihedral refinement (4) stages to ensure physical accuracy. |

| Checkmol | Identifies functional groups within a molecule [18]. | Useful for analyzing and categorizing molecules, especially when identifying problematic chemistries. |

| Phenylfluorone | Phenylfluorone, CAS:975-17-7, MF:C19H12O5, MW:320.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Vinyl decanoate | Vinyl decanoate, CAS:4704-31-8, MF:C12H22O2, MW:198.30 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

A Case Study: Parameterizing Fluorinated Nucleosides

Parameterizing molecules with complex electronic effects, such as fluorinated nucleosides, showcases the necessity of this workflow.

- The Challenge: The gauche effect and anomeric effect in fluorinated furanose rings dramatically influence sugar pucker conformation, which in turn affects biological activity. Standard GAFF parameters failed to reproduce QM-derived pseudorotation energy profiles [19].

- Application of the Workflow:

- Structure & Optimization: Model systems of mono- and di-fluorinated furanose rings were built and optimized with QM.

- Charge Assignment: IpolQ charges, derived to be consistent with the TIP3P water model and protein force fields, were used instead of standard charges [19].

- Parameter Refinement: Torsional parameters related to the furanose ring were optimized to reproduce QM umbrella sampling data. This created a refined parameter set (

sugar_mod).

- Outcome: The refined parameters transformed the relationship between MM and QM energies from

gaff = 0.731 × QMtosugar_mod = 0.973 × QM, and significantly improved the agreement with experimental NMR sugar pucker probabilities [19]. This was critical for understanding the structure-activity relationship of fluorinated Sal-AMS analogs as tuberculosis inhibitors.

A systematic approach to parameterizing small molecules with GAFF is not merely a procedural formality but a critical step in ensuring the reliability of subsequent molecular simulations. This is especially true for sensitive properties like diffusion coefficients. The workflow presented herein—encompassing careful structure preparation, charge assignment, and targeted dihedral refinement—provides a robust framework for researchers. By leveraging modern toolkits and validating against quantum mechanical and experimental data, scientists can overcome known limitations of the general force field, thereby enhancing the predictive power of their computational studies in drug development and materials science.

Calculating Self-Diffusion and Tracer Diffusion Coefficients

The accurate calculation of diffusion coefficients is a cornerstone of research in pharmaceuticals, materials science, and chemical engineering. For researchers investigating molecular transport in drug development, predicting how compounds diffuse through biological fluids or solvent systems is essential for understanding drug release, permeability, and bioavailability. Within this context, molecular dynamics (MD) simulations have emerged as a powerful computational tool that provides atomic-level insights into diffusion processes, complementing experimental approaches.

The performance of MD simulations critically depends on the force fields that describe interatomic interactions. Within the ecosystem of available force fields, the General AMBER Force Field (GAFF) provides broad coverage for organic molecules, making it particularly relevant for pharmaceutical applications. This application note details protocols for calculating self-diffusion coefficients (which measure the intrinsic motion of particles within a pure substance) and tracer diffusion coefficients (which describe the motion of a dilute solute within a solvent), with specific attention to methodologies that ensure accuracy and computational efficiency.

Theoretical Background

Defining Diffusion Coefficients

Self-diffusion coefficient ((D{11})) quantifies the translational motion of a particle in a pure substance at equilibrium. It reflects the intrinsic mobility of molecules due to thermal motion in the absence of concentration gradients. In contrast, tracer diffusion coefficient ((D{12})) describes the mobility of a dilute solute (the tracer) within a solvent. In the limit where the solute concentration approaches zero, (D{11}) represents the tracer diffusion coefficient of solute 1, and (D{22}) is the binary diffusion coefficient of solute 2 in the pure solvent [23].

These coefficients are fundamentally connected to Fick's laws of diffusion. While Fick's first law establishes that the diffusive flux is proportional to the concentration gradient, the physical meaning of the diffusion coefficient in Fick's law has been reinterpreted in recent work as the product of a characteristic length and diffusion velocity: (Di = Vi \times L_i) [24].

Molecular Dynamics Fundamentals

In MD simulations, diffusion coefficients are typically calculated from particle trajectories using the Einstein relation, which connects the mean squared displacement (MSD) of particles over time to the diffusion coefficient:

[ D = \frac{1}{2d} \lim_{t \to \infty} \frac{d}{dt} \langle | \mathbf{r}(t) - \mathbf{r}(0) |^2 \rangle ]

where (d) is the dimensionality, and (\langle \cdots \rangle) denotes the ensemble average. For reliable results, the MSD must be computed in the normal diffusion regime, excluding initial ballistic and eventual anomalous diffusion phases [24].

Table 1: Key Diffusion Coefficient Types and Their Applications

| Diffusion Coefficient Type | Symbol | Definition | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Self-diffusion | (D_{11}) | Motion of particles in a pure substance | Characterizing solvent mobility, reference measurements |

| Tracer diffusion | (D_{12}) | Motion of dilute solute in solvent | Drug diffusion in biological fluids, extraction processes |

| Binary diffusion | (D_{22}) | Mutual diffusion in binary systems | Modeling separation processes, environmental transport |

Computational Methods and Protocols

Force Field Selection and Parametrization

The accuracy of diffusion coefficients calculated via MD simulations depends critically on the chosen force field. While GAFF provides broad organic molecule coverage, its performance for diffusion properties should be validated against experimental data or higher-level calculations. Recent research indicates that careful parametrization of specific interaction sites can significantly improve accuracy.

For instance, in OPLS-AA simulations of ethanol, recalculating the oxygen atom diameter (σOH) from 0.312 nm to 0.306 nm substantially improved agreement with experimental tracer diffusivities of protic solutes like quercetin and gallic acid, reducing average absolute relative deviations (AARD) to 3.71-4.59% compared to >25% with the original parameter [9]. This demonstrates that specific force field parameters may require optimization for accurate transport property prediction, a consideration equally relevant to GAFF applications.

Specialized force fields continue to emerge for specific biological systems. For example, BLipidFF was recently developed for mycobacterial membrane lipids, incorporating quantum mechanics-derived parameters that better capture membrane rigidity and diffusion rates compared to general force fields [6]. Such developments highlight the ongoing evolution of force fields for biologically relevant systems.

MD Simulation Protocol for Diffusion Coefficients

The following protocol provides a generalized framework for calculating diffusion coefficients using MD simulations, adaptable to various biomolecular systems relevant to drug development.

Figure 1: MD simulation workflow for calculating diffusion coefficients

System Setup and Equilibration

Solvation: Place the solute (for tracer diffusion) or pure substance (for self-diffusion) in an appropriate periodic box with sufficient solvent molecules to eliminate artificial periodicity effects. For tracer diffusion, maintain dilute conditions (typically <5% mole fraction) [25].

Energy Minimization: Use steepest descent or conjugate gradient algorithms to remove steric clashes and bad contacts, ensuring initial system stability.

Equilibration: Perform sequential equilibration in the NVT (constant Number, Volume, Temperature) and NPT (constant Number, Pressure, Temperature) ensembles to reach experimental density and proper thermodynamic conditions. For organic liquids like ethanol, typical equilibration times range from 1-5 ns at 303-333 K [9] [25].

Production Run and Analysis

Trajectory Production: Conduct extended production runs (typically 10-100 ns, depending on system size and diffusion rates) with appropriate thermostats (e.g., Nosé-Hoover) and barostats (e.g., Parrinello-Rahman). Save trajectories at frequent intervals (0.1-10 ps) for adequate resolution of molecular motion.

MSD Calculation: Compute the MSD from particle coordinates using the Einstein relation. Ensure analysis occurs in the normal diffusion regime by verifying linear MSD versus time behavior [24].

Statistical Accuracy: Repeat calculations with different initial conditions or use block averaging to estimate statistical uncertainties. For tracer diffusion in ethanol, typical uncertainties range from 1.5-9% when properly converged [25].

Machine Learning and Alternative Approaches

Recent advances incorporate machine learning (ML) methods to predict diffusion coefficients from macroscopic properties, bypassing computationally expensive MD simulations. Symbolic regression, a ML technique that discovers mathematical relationships from data, has derived simple expressions for self-diffusion coefficients of various molecular fluids:

[ D^* = \alpha1 T^{*\alpha2} \rho^{*\alpha3} - \alpha4 ]

where (D^), (T^), and (\rho^) are reduced diffusion coefficient, temperature, and density, respectively, and (\alpha_i) are fluid-specific parameters [26]. For confined systems, the channel width ((H^)) becomes an additional parameter. These approaches achieve accuracy comparable to MD (AAD ~8%) while significantly reducing computational cost [26].

Table 2: Comparison of Diffusion Coefficient Calculation Methods

| Method | Key Features | Accuracy | Computational Cost | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classical MD (Einstein) | Atomistic detail, direct from trajectories | AARD 3-12% [9] [25] | High (system-dependent) | Force field dependence, sampling limitations |

| Machine Learning (SR) | Macroscopic parameters, simple expressions | AAD ~8% [26] | Low (after training) | Training data requirement, transferability |

| New D = V×L Model | Characteristic length × velocity | ARD 8.18% [24] | Moderate | Limited validation across diverse systems |

Experimental Validation Methods

Computational predictions require experimental validation. Several techniques exist for measuring diffusion coefficients, each with advantages and limitations.

Taylor Dispersion Method

This method involves injecting a solute pulse into solvent flowing through a capillary tube. The spreading of the solute band at the outlet is measured and related to the diffusion coefficient through the solution of the dispersion equation. This technique is widely used for liquid-phase diffusion measurements [27].

Fluorescence Recovery After Photobleaching (FRAP)

FRAP measures lateral diffusion in membranes or confined systems by photobleaching a fluorescent region and monitoring fluorescence recovery as unbleached molecules diffuse in. This technique validated the lateral diffusion coefficient of α-mycolic acid in recent mycobacterial membrane studies [6].

Direct Concentration Profiling

A novel method directly measures the spatial concentration profile during diffusion in a chamber. By fitting the experimental profile to the analytical solution of Fick's second law, the diffusion coefficient is obtained with approximately 3% uncertainty, requiring no prior knowledge of solute or solvent properties [27].

Table 3: Experimental Techniques for Diffusion Coefficient Measurement

| Technique | Principle | Applicable Systems | Key Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|

| Taylor Dispersion | Band broadening in capillary flow | Liquids, solutions | Calibrated flow system, detection method |

| FRAP | Fluorescence recovery after photobleaching | Membranes, confined systems | Fluorescent tracer, confocal microscopy |

| Direct Profiling | Spatial concentration evolution | Liquid solutions | Optical access, concentration detection |

| Dynamic Light Scattering | Light intensity fluctuations from particle motion | Colloids, nanoparticles | Spherical particles, transparent solutions |

Application Notes for Drug Development

For pharmaceutical researchers applying these methods, several practical considerations emerge:

Force Field Performance: When using GAFF for drug-like molecules in solution, validate against available experimental data for similar compounds. Partial charge derivation methods (e.g., RESP) significantly impact diffusion prediction accuracy [6].

Solvent Selection: Ethanol is a common pharmaceutical solvent whose diffusion properties have been extensively simulated. Recent work demonstrates that OPLS-AA accurately captures tracer diffusivities of ketones and aldehydes in ethanol (AARD 6.30-12.18%), with improvement to 1.52-5.16% after temperature-based correction [25].

Confined Systems: For diffusion in confined environments (e.g., porous drug delivery systems), account for size effects. Studies show that diffusion coefficients increase with pore size, approaching bulk values beyond a critical width [26].

Essential Research Reagents and Tools

Table 4: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Diffusion Studies

| Reagent/Solution | Function/Application | Example Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Fluorescent microspheres | Experimental tracer validation | Polystyrene, r = 0.075 μm [27] |

| Matching density solvents | Prevents sedimentation in experiments | Dâ‚‚O-water mixtures [27] |

| GAFF Force Field | Organic molecule parametrization | AMBER-compatible, broad chemical coverage [6] |

| - RESP Charge Derivation | Partial charge calculation for molecules | B3LYP/def2TZVP level [6] |

| - Lennard-Jones Potential | Basic non-bonded interactions in MD | Standard combining rules [26] |

Calculating self-diffusion and tracer diffusion coefficients requires careful attention to methodological details across computational and experimental approaches. MD simulations with appropriate force fields like GAFF provide molecular insights but benefit from parameter optimization for specific systems. Emerging machine learning approaches offer computationally efficient alternatives with reasonable accuracy. For drug development applications, selection of appropriate validation methods and consideration of environmental factors such as confinement effects are essential for predicting molecular transport in biologically relevant systems.

In molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, the accuracy of predicted properties, such as diffusion coefficients, is profoundly influenced by the fundamental aspects of system setup. The choice of box size, the level of hydration, and the treatment of boundary conditions are not merely technical steps but are critical determinants of the physical realism of the simulation. Within the context of research utilizing the General AMBER Force Field (GAFF), these choices can significantly impact the calculated transport properties, solvation structure, and ultimately, the reliability of conclusions drawn for applications in drug development and materials science [8]. This note outlines validated protocols and evidence-based recommendations for configuring these parameters to ensure the faithful reproduction of experimental observables, particularly diffusion coefficients.

Core Principles and Parameter Selection

The Role of Boundary Conditions and Box Size

Modern MD simulations of condensed phases predominantly employ Periodic Boundary Conditions (PBC) with Lattice Sums (LS) and the Particle Mesh Ewald (PME) method for electrostatics. This PBC-LS/PME protocol has become the de facto standard for simulating biological systems [10]. Its primary function is to eliminate surface effects and model a bulk-like environment, but it introduces a finite system size that must be carefully managed.

For a cubic box with side length ( L ) (in Ã…), the nominal concentration is set by the box volume ( L^3 ). The simulation aims to mimic infinite dilution conditions, which is achieved when ( L ) is sufficiently large. A key criterion is that the local solvent density ( \rho(r) ) at a distance ( L/2 ) from any solute atom must approximate the bulk solvent density ( \rho ). When this condition is met, properties like hydration free energies become stable with respect to further increases in ( L ) [10].

A critical consideration for charged systems is the Effective Ionic Strength (EIS). For a system containing ( n ) ions of unitary charge in a cubic box of side ( L ) (Å), the ionic strength ( I ) (in M) is given by [10]: [ I = \frac{n}{2 \times 1661} \times \left( \frac{10}{L} \right)^3 ] where ( V_0 = 1661 ) ų is a standard conversion factor. This formula is essential for matching the experimental ionic strength conditions, a factor often overlooked in simulations of highly charged host-guest systems [10].

Force Field and Solvent Model Selection

The performance of GAFF is intrinsically linked to the accompanying solvent model and charge generation method. Recent developments have led to the ABCG2 charge model for GAFF2, which was optimized using a solvation free energy (SFE) strategy. This model has demonstrated a marked improvement, reducing the mean unsigned error (MUE) for hydration free energies (HFEs) of 442 neutral organic molecules from 1.03 kcal/mol (with the original AM1-BCC) to 0.37 kcal/mol [1]. This enhanced accuracy in modeling solvation is directly relevant for obtaining correct diffusion behavior.

The choice of water model also systematically influences the prediction of hydrophobic solvation. For instance, when combined with the TraPPE-UA force field for alkanes, four-site water models (TIP4P/2005, OPC) provide better estimates of hydration free energies compared to three-site models (SPC/E, OPC3) [28]. Furthermore, the standard Lorentz-Berthelot mixing rules can overestimate alkane-water attractions, leading to exaggerated hydration free energies; this can be corrected through specific reparameterization of the Lennard-Jones well-depth [28].

Table 1: Key Research Reagent Solutions for GAFF Simulations

| Reagent Category | Specific Name/Model | Function and Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| General Force Field | GAFF2 (Generalized AMBER Force Field 2) | Provides parameters for small organic molecules; updated bonded/nonbonded terms from GAFF [1]. |

| Charge Model | ABCG2 (Optimized AM1-BCC for GAFF2) | Fast, accurate charge assignment; significantly improves HFE prediction (MUE: 0.37 kcal/mol) [1]. |

| Water Models | TIP4P/2005, OPC (4-site)SPC/E, OPC3 (3-site) | TIP4P/2005 shows superior performance for hydrophobic solutes [28]. Model choice balances accuracy and computational cost. |

| Non-Polar Solute FF | HH-Alkane (reparameterized TraPPE-UA) | A reparameterized force field for alkanes with TIP4P/2005 that reproduces experimental hydration free energies [28]. |

Recommended Protocols for System Setup

Protocol 1: General System Setup for Neutral Organic Molecules

This protocol is designed for simulating small, neutral drug-like molecules to compute properties such as hydration free energy or diffusion coefficients [14] [1].

Workflow Overview:

Detailed Steps:

- Force Field Parameterization: Obtain GAFF2 parameters for the solute. Generate atomic partial charges using the ABCG2 model, which is optimized for GAFF2 and available through the ANTECHAMBER tool, to ensure accurate solvation thermodynamics [1].

- Solvation: Place a single solute molecule in the center of a cubic box. Solvate the system using a chosen water model (e.g., TIP4P/2005 for hydrophobic moieties). The box side length ( L ) should be chosen such that the minimum distance between any solute atom and its periodic image is at least 1.0 nm (10 Ã…). A larger margin of 1.2 to 1.4 nm (12-14 Ã…) is recommended to minimize spurious periodicity effects on the solute's correlated motion and diffusion [14].

- Neutralization and Ionic Strength: For charged solutes, add a sufficient number of counter-ions (e.g., Naâº/Clâ») to achieve a net neutral system. If simulating at a specific ionic strength (e.g., 0.15 M to mimic physiological conditions), use the EIS formula to calculate the number of ion pairs ( n ) required for a given box size ( L ) [10].

- Simulation Parameters:

- Electrostatics: Use the Particle Mesh Ewald (PME) method. Set the Coulomb cutoff (

rcoulomb) to match the VDW cutoff [10]. - Van der Waals: Use a cutoff scheme (e.g.,

cutoff-scheme = Verlet). Set the VDW cutoff (rvdw) to 1.2 nm. Avoid using a potential-shifted Lennard-Jones potential, as it can systematically alter hydration free energy estimates [28]. - Constraints: Apply constraints to all bonds involving hydrogen atoms (

constraints = h-bonds). - Thermostat and Barostat: Use a stochastic thermostat (e.g., Nosé-Hoover) and a semi-isotropic barostat (e.g., Parrinello-Rahman) for membrane systems or an isotropic barostat for solution simulations during NPT equilibration and production.

- Electrostatics: Use the Particle Mesh Ewald (PME) method. Set the Coulomb cutoff (

Protocol 2: Setup for Highly Charged Systems (Host-Guest Complexes)

Simulating highly charged macrocycles, such as those featured in the SAMPL challenges, requires special attention to neutralization methodology [10].

Workflow Overview:

Detailed Steps:

- Parameterization Scrutiny: For symmetric, highly charged hosts, meticulously check torsional parameter assignments. Seemingly minor differences, such as between GAFF and GAFF2 for a single torsional angle in a host's rim, can be systematically amplified, leading to significant errors in binding affinities and potentially affecting complex dynamics [10].

- Box Size and Neutralization:

- Use a cubic box with a minimum padding of 1.4 nm (14 Ã…) between the complex and box edges.

- Neutralization can be handled via two primary methods, which have been shown to yield well-correlated results for absolute dissociation free energies [10]:

- Explicit Ions: Add the necessary number of counter-ions to neutralize the total system charge. To match experimental buffer conditions (e.g., ~0.2 M), use the EIS formula to calculate and add the required number of salt ion pairs.

- Uniform Neutralizing Background: Rely on the uniform neutralizing plasma inherent to the Ewald summation method. This approach is computationally simpler for highly charged systems but may require finite-size corrections for absolute free energies.

- Consistency in Alchemical Simulations: When performing alchemical free energy calculations (e.g., for binding affinity), ensure the Effective Ionic Strength (EIS) is identical in both the bound (complex) and unbound (guest in solution) legs of the thermodynamic cycle. This requires adjusting the number of explicit ions if the box sizes between the two legs differ [10].

Table 2: Summary of Key System Setup Parameters and Recommendations

| Parameter | Neutral Organic Molecules | Highly Charged Systems | Rationale and Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Box Shape | Cubic | Cubic | Standard choice for isotropic solutions. |

| Minimum Box Padding | 1.0 - 1.2 nm | ≥ 1.4 nm | Larger padding minimizes finite-size effects on diffusion and periodicity artifacts for charged systems [14] [10]. |

| Boundary Conditions | PBC with PME | PBC with PME | Standard for bulk simulations. "Tinfoil" (zero dipole) conditions are implied [10]. |

| Electrostatics | PME | PME | Handles long-range interactions accurately. |

| VDW Cutoff | 1.2 nm | 1.2 nm | Common balance of accuracy and speed. Avoid potential shifting [28]. |

| Neutralization Method | Explicit ions | Explicit ions or Uniform Background | For charged systems, both methods can be valid, but explicit ions more directly control ionic strength [10]. |

| Ionic Strength Control | Via EIS formula ( I = \frac{n}{2V} ) | Via EIS formula ( I = \frac{n}{2V} ) | Critical for matching experimental conditions and ensuring consistency in free energy cycles [10]. |

A meticulously designed system setup is a prerequisite for obtaining reliable diffusion coefficients and other dynamic properties from MD simulations using the GAFF force field. The protocols outlined herein emphasize the importance of appropriate box sizing, the selection of advanced charge models like ABCG2, and the careful treatment of boundary conditions and ionic strength. Adhering to these evidence-based recommendations will enhance the physical realism of simulations and the credibility of research findings, thereby supporting more robust decision-making in scientific and drug development endeavors.

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation is a powerful computational tool for investigating the thermophysical properties of materials at the molecular level, providing insights crucial for pharmaceutical, biomedical, and materials science applications. [7] The accuracy of these simulations heavily depends on the force field selected to describe atomic interactions. For polyethylene glycol (PEG) and its oligomers—versatile polymers with extensive applications in drug delivery, cosmetic products, and industrial manufacturing—selecting an appropriate force field is particularly critical. [7] This case study evaluates the performance of the General AMBER Force Field (GAFF) in simulating PEG oligomers, with a specific focus on its capability to predict diffusion coefficients and other key thermophysical properties. We frame this assessment within a broader thesis on GAFF's reliability for transport property research, providing structured quantitative data, detailed protocols, and practical guidance for researchers.

Performance Benchmarking: GAFF vs. Experimental Data

The GAFF force field demonstrates exceptional accuracy in reproducing experimental thermophysical properties of PEG oligomers, significantly outperforming alternative models.

Table 1: Comparison of GAFF Performance with Experimental Data for a PEG Tetramer at 328 K

| Property | GAFF Result | Experimental Data | Agreement | OPLS Force Field Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Density | Calculated value | Reference value | Within 5% | Not specified |

| Self-diffusion Coefficient | Calculated value | Reference value | Within 5% | >80% deviation |

| Shear Viscosity | Calculated value | Reference value | Within 10% | >400% deviation |

For a PEG tetramer, GAFF reproduces experimental data within 5% for density, 5% for the diffusion coefficient, and 10% for the viscosity. [7] In contrast, the OPLS force field exhibits significant deviations exceeding 80% for the diffusion coefficient and 400% for the viscosity. [7] This remarkable accuracy makes GAFF particularly suitable for investigating diffusion phenomena in PEG-based systems, which is crucial for understanding drug release kinetics, polymer electrolyte behavior, and transport mechanisms in biological environments.

The superior performance of GAFF is attributed to its accurate parameterization of partial charge distributions and dihedral angles, which significantly impact the structural behavior and dynamics of PEG oligomers. [7] The partial atomic charges in GAFF for the ether (–CH2–O–) and hydroxyl (–O–H) groups create an electrostatic profile that closely matches the molecular polarization in real PEG systems, leading to more realistic chain packing and intermolecular interactions that directly influence diffusion rates. [7]

Experimental Protocol for PEG Oligomer Simulations

System Setup and Initialization

- Molecular Structure Construction: Build all-atom models of PEG oligomers (n = 2–7) using chemical drawing software or molecular builder tools. The chemical structure is H–[O–CH2–CH2]n–OH. [7]

- Force Field Assignment: Apply GAFF parameters using tools such as Antechamber or similar utilities compatible with AMBER-based force fields. The potential function includes bond stretching, angle bending, proper dihedrals, and non-bonded interactions. [7]

- Partial Charge Assignment: Utilize the default GAFF atomic partial charges, which have been optimized for accurate electrostatic representation: [7]

- Ether oxygen (–CH2–O–): -0.34 e

- Ether carbon (–CH2–O–): 0.05 e

- Ether hydrogen (–CH2–O–): 0.09 e

- Hydroxyl oxygen (–O–H): -0.65 e

- Hydroxyl hydrogen (–O–H): 0.42 e

- Simulation Box Preparation: Pack multiple PEG oligomer molecules into a cubic simulation box using packing software such as PACKMOL, targeting experimental densities where available. [29]

Simulation Parameters

- Software: Employ the LAMMPS (Large-scale Atomic/Molecular Massively Parallel Simulator) code for production MD simulations. [7] [30]

- Temperature Control: Maintain the system at 328 K, which represents a mid-range temperature with abundant experimental data for validation. [7]

- Non-bonded Interactions: Apply the standard GAFF combination rules for Lennard-Jones parameters: σij = (σiσj)^1/2 and εij = (εiεj)^1/2. [7] Use fudge factors of 0.5 for 1–4 non-bonded interactions and 1.0 for all other pairs. [7]

- Electrostatics: Employ particle-particle particle-mesh (PPPM) methods for long-range electrostatic interactions with a cutoff of 10-12 Ã… for short-range interactions.

Property Calculation Methods

Diffusion Coefficients: Calculate self-diffusion coefficients using the Einstein relation from mean-squared displacement (MSD) data: [7]

Equation 1: ( D = \frac{1}{6N} \lim{t \to \infty} \frac{d}{dt} \sum{i=1}^{N} \langle | \mathbf{r}i(t) - \mathbf{r}i(0) |^2 \rangle )

Where D is the diffusion coefficient, N is the number of molecules, ri(t) is the position of molecule i at time t, and the angle brackets denote ensemble averaging.

- Shear Viscosity: Compute using the Green-Kubo relation integrating the stress autocorrelation function or via non-equilibrium MD methods. [7]

- Thermal Conductivity: Determine using the Green-Kubo approach based on heat current autocorrelation functions.

- Structural Properties: Analyze radial distribution functions, end-to-end distances, and radius of gyration from trajectory data to understand chain packing and conformation.

Figure 1: MD Simulation Workflow for PEG Oligomers. The diagram outlines the key stages in molecular dynamics simulations of polyethylene glycol oligomers using the GAFF force field, from initial system setup through production runs and analysis.

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools for PEG Oligomer Simulations

| Tool Category | Specific Resources | Application in PEG Research |

|---|---|---|

| Simulation Software | LAMMPS [7] [30], AMBER, GROMACS | Molecular dynamics engines for running simulations |

| Parameterization Tools | Antechamber [29], Gaussian [7] | Force field assignment and charge parameterization |

| System Preparation | PACKMOL [29] | Initial simulation box setup and packing |

| Quantum Chemistry | Gaussian 09 [7], DFT/B3LYP/6-311+G(d,p) | Electronic structure calculations for charge derivation |

| Analysis Tools | MDTraj, VMD, Python/R scripts | Trajectory analysis and property calculation |

| Force Fields | GAFF [7], OPLS [29], Modified AMBER-compatible [31] | Molecular interaction potentials |

Advanced Applications and Implementation Considerations

Charge Modification Strategies

While standard GAFF charges yield excellent results, further refinement is possible through charge reparameterization:

- DFT Calculations: Perform density functional theory (DFT) calculations using the B3LYP hybrid functional with the 6-311+G(d,p) basis set to derive alternative atomic charges. [7]

- Charge Models: Compare multiple charge models including CM5, Hirshfeld, Mulliken, and ESP (electrostatic potential) for optimal property reproduction. [7]

- RESP Implementation: Apply the Restrained Electrostatic Potential (RESP) method for charge fitting, which has shown improved performance for poly(ethylene oxide) systems in dielectric constant calculations. [29]

Specialized Application Protocols

Drug Delivery Nanoparticle Characterization: For PEGylated nanodiamonds or other drug delivery systems, focus on structural properties of the PEG coating rather than bulk diffusion. Simulate PEG chains grafted onto nanoparticle surfaces with varying grafting densities (25-100 chains) and molecular weights (PEG500, PEG1000). [30] Analyze chain extension, surface coverage, and protein resistance properties rather than diffusion coefficients.