Benchmarking Force Fields for Accurate Transport Properties: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Research

Accurately predicting transport properties like diffusion, viscosity, and conductivity is critical for biomedical applications, from drug delivery to electrolyte design.

Benchmarking Force Fields for Accurate Transport Properties: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Research

Abstract

Accurately predicting transport properties like diffusion, viscosity, and conductivity is critical for biomedical applications, from drug delivery to electrolyte design. However, the choice of force field significantly impacts the reliability of molecular dynamics simulations. This article provides a comprehensive framework for benchmarking classical and machine-learned force fields. We explore foundational concepts, methodological applications for complex fluids and polymers, strategies to overcome common pathologies, and rigorous validation protocols. By synthesizing the latest advances, this guide empowers researchers to select, optimize, and validate force fields for trustworthy predictions of dynamic properties in biological and materials systems.

The Critical Role of Force Fields in Predicting Transport Properties

Why Transport Properties Are Pivotal for Biomedical and Materials Applications

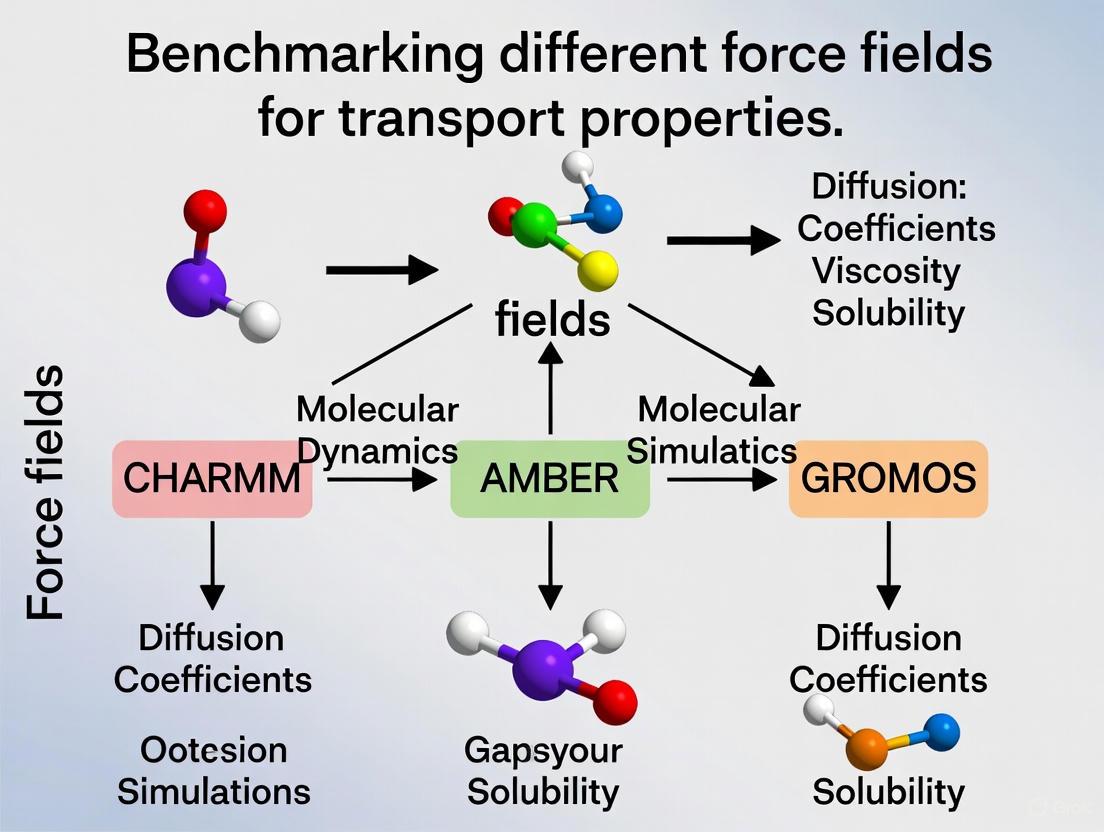

Transport properties—such as viscosity, diffusivity, and electrical conductivity—are critical performance metrics in molecular dynamics (MD) simulations. For researchers in biomedicine and materials science, accurately predicting these properties is essential for designing effective drugs, catalysts, and functional materials. This guide benchmarks the performance of different molecular force fields in predicting key transport properties, providing a foundation for selecting the right model for your research.

Force Fields and Transport Properties

Molecular dynamics simulations rely on force fields—empirical mathematical models that calculate the potential energy of a system of atoms. The accuracy of these simulations in predicting real-world behavior depends entirely on the quality of the force field used. While many force fields accurately predict structural properties, correctly capturing dynamic transport properties presents a greater challenge [1] [2].

The Critical Role of Transport Properties

- Drug Design: Molecular diffusivity and membrane permeability influence drug absorption and distribution.

- Biomolecular Function: Ion conductivity and transport rates are crucial for understanding ion channel proteins and nucleic acid behavior [3].

- Materials Performance: Viscosity and electrical conductivity determine the efficiency of lubricants, batteries, and catalysts [1] [2].

- Process Optimization: Accurate transport properties enable reliable simulation of industrial processes like steelmaking and glass manufacturing [2].

Comparative Performance of Force Fields

The table below summarizes the performance of various force fields across different applications and transport properties:

Table 1: Force Field Performance Across Applications

| Application Domain | Force Fields Compared | Key Transport Properties | Performance Summary |

|---|---|---|---|

| β-Peptides & Biomolecules | CHARMM, Amber, GROMOS [4] | Structural stability, oligomer formation | CHARMM reproduced experimental structures accurately in all monomeric simulations and correctly described all oligomeric examples [4]. |

| Lubricants & Long-Chain Molecules | L-OPLS-AA (all-atom) vs. united-atom [1] | Shear viscosity, diffusion | All-atom L-OPLS-AA accurately predicted viscosity; united-atom models significantly under-predicted viscosity (by ~50% for C16 molecules) [1]. |

| Oxide Melts & Materials | Matsui, Guillot, Bouhadja [2] | Self-diffusion coefficients, electrical conductivity | Bouhadja's force field showed best agreement with experimental activation energies and robust transferability [2]. |

| Liquid Membranes | GAFF, OPLS-AA/CM1A, CHARMM36, COMPASS [5] | Shear viscosity, diffusion, interfacial tension | CHARMM36 and COMPASS provided accurate density and viscosity; GAFF and OPLS-AA overestimated viscosity by 60-130% [5]. |

| Machine Learning Force Fields | CHGNet, M3GNet, MACE, MatterSim, SevenNet, Orb [6] | Structural stability, mechanical properties | Orb and MatterSim demonstrated strongest robustness (100% simulation completion), while CHGNet and M3GNet suffered >85% failure rates [6]. |

Specialized Performance Insights

Table 2: Detailed Force Field Performance Metrics

| Force Field | System Type | Key Strengths | Documented Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| CHARMM | β-peptides [4], liquid membranes [5] | Accurate structural reproduction, good viscosity prediction | Requires specific extensions for non-natural peptidomimetics [4]. |

| L-OPLS-AA (all-atom) | Lubricants (n-hexadecane) [1] | Excellent viscosity prediction, accurate friction behavior | Higher computational cost than united-atom models [1]. |

| Bouhadja BMH Potential | Oxide melts (CaO-Al₂O₃-SiO₂) [2] | Best dynamic property prediction, good transferability | Less accurate for certain structural features compared to Matsui [2]. |

| Machine Learning (Orb, MatterSim) | Universal materials [6] | Broad chemical coverage, good simulation stability | Systematic density errors >2%, performance correlates with training data representation [6]. |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Viscosity Calculation Protocol

For lubricant simulations [1]:

- System Setup: Construct a box of 130 n-hexadecane molecules with periodic boundary conditions

- Simulation Parameters: Use velocity-Verlet integration with 1.0 fs timestep, constrain fast-moving bonds with SHAKE algorithm

- Equilibrium Phase: Conduct equilibrium MD (EMD) simulations at target temperatures and pressures

- Viscosity Calculation: Apply Green-Kubo formula to stress tensor autocorrelation functions: η = (V/kBT) ∫₀∞ ⟨Pαβ(t) · Pαβ(0)⟩dt where V is volume, T is temperature, and Pαβ are off-diagonal elements of the pressure tensor

Ion Transport Validation

For Mg²⺠ion models in biological systems [3]:

- System Preparation: Simulate single Mg²⺠ion in ~1000 water molecules using AMBER14

- Validation Metrics:

- Radial distribution functions (RDF) compared to experimental Mg²âº-O distances

- Solvation free energy calculation using thermodynamic integration

- Water exchange rate from coordinated shell using transition state theory

- Diffusion constants from mean-squared displacement calculations

- Force Field Forms: Compare standard 12-6 Lennard-Jones potentials versus 12-6-4 potentials with charge-induced dipole term

Membrane System Characterization

For liquid membrane simulations [5]:

- Property Calculations:

- Density: NPT ensemble simulations at 243-333K

- Shear Viscosity: Equilibrium MD with Green-Kubo method

- Interfacial Tension: Liquid-liquid interface simulations using mechanical pressure tensor

- Partition Coefficients: Free energy calculations for ethanol in DIPE+Ethanol+Water systems

- Validation: Compare all calculated properties against experimental measurements

Decision Framework for Force Field Selection

The diagram below illustrates the systematic process for selecting an appropriate force field based on your research system and target properties:

Table 3: Key Computational Tools and Resources for Transport Property Studies

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| GROMACS [4] | High-performance MD simulation engine | Impartial force field comparison using same algorithms [4] |

| LAMMPS [1] | Molecular dynamics simulator | Lubricant and materials simulations [1] |

| AMBER [3] | Biomolecular simulation package | Mg²⺠ion validation studies [3] |

| Green-Kubo Method [1] | Calculate transport properties from EMD | Viscosity calculation for n-hexadecane [1] |

| Mean-Squared Displacement (MSD) [7] | Determine diffusion coefficients | Particle mobility in various systems [7] |

| UniFFBench [6] | ML force field benchmarking framework | Evaluate UMLFFs against experimental data [6] |

No single force field excels universally across all systems and transport properties. Classical force fields like CHARMM and all-atom L-OPLS-AA provide reliable performance for specific biomolecular and liquid systems, while specialized potentials like Bouhadja's BMH potential offer advantages for oxide melts. Emerging machine learning force fields show promise for universal application but require careful validation against experimental transport properties.

For research prioritizing transport properties, validation against experimental viscosity, diffusion, or conductivity data is essential—excellent performance on structural benchmarks does not guarantee accurate dynamic property prediction [1] [6]. The force field selection must balance computational efficiency with the specific accuracy requirements of your biomedical or materials application.

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations serve as a cornerstone of atomistic-scale analysis across numerous disciplines, including materials science, drug development, and biochemistry [8]. These computational methods allow researchers to observe the time-dependent behavior of atomic and molecular systems, providing insights that are often difficult or impossible to obtain experimentally. The central dilemma in MD simulations revolves around the choice between computational accuracy and system size/timescale. On one end of the spectrum, ab initio molecular dynamics (AIMD) provides high accuracy by computing electronic structure from first principles, while classical molecular dynamics (CMD) sacrifices quantum mechanical precision to access dramatically larger systems and longer timescales [2]. This fundamental trade-off between scale and accuracy forms the critical decision point for researchers selecting computational approaches for specific scientific questions. The emergence of machine-learning molecular dynamics (MLMD) has further complicated this landscape, offering a potential middle ground with near-ab initio accuracy and improved computational efficiency [8]. Understanding the precise capabilities, limitations, and appropriate applications of each method is essential for advancing computational research across scientific domains.

Theoretical Foundations and Force Fields

The divergence between classical and ab initio MD approaches originates in their fundamentally different treatment of atomic interactions. Ab initio MD relies on quantum mechanical calculations, typically using density functional theory (DFT), to compute interatomic forces by explicitly solving for electronic structure at each simulation step [9]. This parameter-free approach naturally captures complex quantum effects, including chemical bond formation and breaking, charge transfer, and electronic polarization. In contrast, classical MD employs empirically parameterized force fields—mathematical functions that approximate the potential energy surface of a system using pre-defined terms for bond stretching, angle bending, torsional rotations, and non-bonded interactions [1]. These force fields are typically optimized to reproduce either experimental data or results from higher-level quantum calculations for specific classes of compounds [10].

The computational frameworks for these methods reflect their different theoretical foundations. CMD simulations predominantly utilize highly optimized packages like LAMMPS that can efficiently evaluate simple analytical functions across millions of atoms [1] [10]. AIMD implementations, such as those in CP2K or Quantum ESPRESSO, focus instead on solving the electronic structure problem with sufficient accuracy while managing the substantially greater computational load [2]. The recently developed MLMD approaches, including DeePMD-kit and Allegro, represent a hybrid strategy—using neural networks trained on quantum mechanical data to create force fields that retain much of the accuracy of AIMD while approaching the computational efficiency of CMD [8] [11].

Experimental Benchmarking Methodologies

Robust benchmarking is essential for validating both classical force fields and ab initio methods. The protocols differ according to the intended application domain and the fundamental limitations of each approach.

For classical force field validation, the typical workflow involves:

- System Preparation: Constructing initial atomic configurations using tools like Packmol, with careful attention to representative system sizes that minimize finite-size effects while remaining computationally tractable [10].

- Equilibration: Performing extended sampling under appropriate thermodynamic ensembles (NPT for density equilibration, NVT for production runs) while monitoring convergence through energy and density fluctuations [10].

- Property Calculation: Computing structural properties (radial distribution functions, coordination numbers), thermodynamic properties (density, heat capacity), and transport properties (viscosity, diffusion coefficients) from production trajectories [2] [1].

- Experimental Comparison: Validating simulation results against experimental measurements across a range of conditions to assess transferability beyond parameterization domains [10].

For ab initio and MLMD validation, the focus shifts toward accuracy assessment:

- Quantum Mechanical Reference: Generating high-quality reference data using well-converged DFT calculations or higher-level quantum chemical methods [12].

- Property Accuracy: Comparing energy, force, and property predictions against quantum mechanical benchmarks, with particular attention to subtle effects like van der Waals interactions and transition states [8].

- Performance Metrics: Evaluating computational efficiency through time-to-solution metrics (e.g., nanoseconds per day) and parallel scaling characteristics on high-performance computing architectures [11].

Figure 1: MD Method Selection Workflow. This decision tree illustrates the key factors driving the choice between molecular dynamics approaches, highlighting the central trade-off between accuracy and scale.

Performance Comparison: Accuracy, Scale, and Computational Efficiency

Quantitative Performance Metrics

The practical implications of the methodological differences between classical, ab initio, and machine-learning MD approaches become evident when examining specific performance metrics across multiple dimensions. The tables below summarize key comparative data for these methods.

Table 1: Time and Power Consumption Comparison of MD Methods

| Method | Time Consumption (ηt, second/step/atom) | Power Consumption (ηp, Watt) | Typical System Size | Typical Time Scale |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ab Initio MD (AIMD) | 10-3–100 | 106–107 (CPU/GPU) [8] | 100-1,000 atoms [2] | Picoseconds [11] |

| Machine-Learning MD (MLMD) | 10-6–10-3 | 104–105 (CPU/GPU) [8] | 105–107 atoms [11] | Nanoseconds [11] |

| Classical MD (CMD) | 10-9–10-6 | 103–104 (CPU/GPU) [8] | 106–109 atoms [2] | Nanoseconds to microseconds [1] |

| Special-Purpose MDPU | ~10-9 (vs. AIMD) [8] | ~103–104 [8] | Not specified | Not specified |

Table 2: Accuracy Comparison Across MD Methods for Various Systems

| System | Method | Energy Error (εe, meV/atom) | Force Error (εf, meV/Å) | Experimental Agreement |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Au | MLMD (MDPU) | 85.35 | 173.20 | Accurate under shock compression [8] |

| Cu | MLMD (MDPU) | 1.84 | 16.44 | Accurate strain-stress curve [8] |

| Hâ‚‚O | MLMD (MDPU) | 7.62 | 148.24 | Accurate radial distribution function [8] |

| CaO-Al₂O₃-SiO₂ | CMD (Bouhadja FF) | Not specified | Not specified | Good for dynamics, fair for structure [2] |

| CaO-Al₂O₃-SiO₂ | CMD (Matsui FF) | Not specified | Not specified | Good for structure, poor for dynamics [2] |

| n-hexadecane | CMD (L-OPLS-AA) | Not specified | Not specified | Accurate density/viscosity [1] |

| PDMS | CMD (Huang FF) | Not specified | Not specified | Good thermodynamic properties [10] |

Table 3: Recent Performance Advances in Neural Network MD (as of 2024)

| Software | System | # Atoms | Hardware | Performance (ns/day) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DeePMD-kit (optimized) | Cu | 0.5M | 576K cores, Fugaku | 149 [11] |

| DeePMD-kit (optimized) | Hâ‚‚O | 0.5M | 576K cores, Fugaku | 68.5 [11] |

| DeePMD-kit (baseline) | Cu | 2.1M | 218.8K cores, Fugaku | 4.7 [11] |

| Allegro | Ag | 1M | 128 A100 GPUs | 49.4 [11] |

| SNAP ML-IAP | C | 1B | 27.3K GPUs, Summit | 1.03 [11] |

The performance data reveals several critical patterns. First, the computational efficiency gap between methods spans multiple orders of magnitude, with classical MD exceeding ab initio MD in speed by approximately 10³-10⹠times depending on the specific implementation and hardware [8]. This efficiency comes at the cost of parameterization dependence—classical force fields must be carefully selected and validated for specific systems and conditions, as their accuracy varies significantly across different chemical environments [2] [1]. The emergence of specialized hardware like the MD Processing Unit (MDPU) promises to further reshape this landscape, potentially reducing time and power consumption by approximately 10³ times compared to state-of-the-art MLMD based on CPU/GPU [8].

Force Field Accuracy and Transferability

The accuracy of classical MD simulations is intrinsically linked to the quality and transferability of the employed force fields. Recent benchmarking studies reveal substantial variations in performance across different force fields and material systems. For CaO-Al₂O₃-SiO₂ melts, Bouhadja's force field demonstrates superior performance in capturing melt dynamics and conductivity trends, while Matsui's force field provides more accurate structural predictions [2]. Similarly, for organic systems, all-atom force fields like L-OPLS-AA significantly outperform united-atom variants in predicting viscosity and structural properties of long-chain molecules like n-hexadecane [1].

The transferability of force fields beyond their parameterization domain remains a persistent challenge. In polysiloxane systems, force fields specifically parameterized for PDMS (e.g., Huang's model) generally outperform general-purpose force fields like OPLS-AA and Dreiding in predicting thermodynamic and transport properties [10]. This underscores the importance of domain-specific parameterization and the limitations of transferable force fields for applications requiring quantitative accuracy.

Application Guidelines: Selecting the Appropriate Method

Problem-Method Alignment

Choosing the appropriate MD method requires careful consideration of the specific scientific question, accuracy requirements, and available computational resources. The following guidelines emerge from the performance benchmarking:

Ab Initio MD is recommended for:

- Studying chemical reactions with bond formation/breaking [8]

- Investigating electronic properties and charge transfer phenomena [9]

- Systems where no reliable classical force fields exist [12]

- Generating reference data for force field parameterization [10]

Classical MD is preferred for:

- Large-scale systems (>100,000 atoms) requiring statistical sampling [2]

- Processes requiring microsecond timescales or longer [1]

- Calculating transport properties like viscosity and diffusion [10]

- Systems with well-parameterized, validated force fields [1]

Machine-Learning MD is optimal for:

- Applications requiring near-ab initio accuracy at larger scales [11]

- Systems where AIMD is too costly but CMD is insufficiently accurate [8]

- Complex processes involving both structural dynamics and electronic effects [11]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Solutions

Table 4: Essential Software and Computational Tools for Molecular Dynamics Research

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function | Applicable Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| LAMMPS | Software Package | High-performance MD simulation with extensive force field support [1] [10] | CMD, MLMD |

| DeePMD-kit | Software Package | Neural network MD with ab initio accuracy [11] | MLMD |

| CP2K | Software Package | Ab initio MD using DFT [8] | AIMD |

| Quantum ESPRESSO | Software Package | Open-source suite for ab initio calculations [8] | AIMD |

| Packmol | Tool | Initial configuration generation for MD simulations [10] | All methods |

| COMPASS | Force Field | Class II force field for various materials including siloxanes [10] | CMD |

| OPLS-AA | Force Field | All-atom force field for organic liquids [1] [10] | CMD |

| MDPU | Hardware | Special-purpose processor for MD simulations [8] | All methods |

| L-Alanine isopropyl ester | L-Alanine isopropyl ester, MF:C6H13NO2, MW:131.17 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Antibacterial agent 199 | Antibacterial agent 199, MF:C37H48N6O8, MW:704.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

The evolving landscape of molecular dynamics simulations continues to offer researchers an expanding array of computational tools, each with characteristic strengths and limitations. The fundamental trade-off between spatial/temporal scale and quantum mechanical accuracy remains, but the boundaries are continually being pushed forward through methodological innovations. Machine-learning approaches are particularly promising, already demonstrating the ability to simulate systems of millions of atoms with ab initio accuracy at unprecedented timescales—reaching 149 nanoseconds per day for copper systems on advanced supercomputing architectures [11]. Special-purpose hardware like the MDPU suggests a pathway to further dramatic efficiency improvements, potentially reducing time and power consumption by orders of magnitude compared to current CPU/GPU-based approaches [8].

For researchers, the critical imperative remains the careful matching of method to scientific question, with explicit consideration of accuracy requirements, system size, timescale needs, and available computational resources. As force field development continues to advance—with more sophisticated parameterization approaches and better understanding of transferability limitations—classical MD will maintain its essential role for large-scale and long-timescale simulations. Simultaneously, the ongoing integration of machine learning with traditional quantum mechanical approaches promises to further blur the lines between accuracy and efficiency, potentially making ab initio quality simulations accessible for increasingly complex systems and phenomena relevant to drug development, materials design, and fundamental scientific discovery.

The accurate prediction of transport properties—diffusion, viscosity, and ionic conductivity—is fundamental to advancements in materials science, drug development, and energy storage technologies. These dynamic properties govern processes ranging from ion transport through biological membranes to the flow behavior of industrial melts and electrolytes. Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations have emerged as a powerful tool for investigating these properties at the atomistic level, but their predictive accuracy depends entirely on the underlying empirical force fields that describe interatomic interactions. Force fields are mathematical representations of the potential energy surface that determine how atoms interact, making them the foundational component of any classical MD simulation. The challenge researchers face is that numerous force fields exist, each with different parameterization strategies, functional forms, and applicability domains, leading to significant variations in their predictive performance for transport properties.

This guide provides a comprehensive benchmarking analysis of popular force fields across diverse chemical systems, presenting quantitative performance data and detailed methodological protocols. As force field selection critically influences simulation outcomes, systematic comparison enables researchers to make informed choices specific to their systems of interest. Recent studies have demonstrated that force field transferability—the ability to perform accurately outside original parameterization ranges—remains a significant challenge, particularly for dynamic properties that require longer simulation timescales. Furthermore, the emergence of machine learning force fields promises to bridge the accuracy gap between classical MD and quantum-mechanical methods while maintaining computational feasibility for larger systems. By objectively comparing force field performance across multiple chemical domains and providing standardized assessment methodologies, this guide serves as an essential resource for researchers requiring reliable transport property predictions.

Performance Comparison of Force Fields Across Systems

The accuracy of force fields varies significantly across different chemical systems and target properties. The tables below summarize quantitative performance data from recent benchmarking studies.

Oxide Melts (CaO-Al₂O₃-SiO₂ System)

Table 1: Force field performance for structural and transport properties of oxide melts [2] [13]

| Force Field | Density Prediction | Si–O Coordination | Al–O Coordination | Self-Diffusion Coefficients | Electrical Conductivity | Transferability Assessment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Matsui | Accurate across compositions | Excellent agreement with AIMD | Less accurate vs. AIMD | Moderate accuracy | Underestimates experimental values | Limited beyond original parameterization |

| Guillot | Accurate across compositions | Excellent agreement with AIMD | Less accurate vs. AIMD | Moderate accuracy | Underestimates experimental values | Limited beyond original parameterization |

| Bouhadja | Slightly less accurate | Good agreement with AIMD | Best agreement with AIMD | Best agreement with experiments | Best agreement with experiments | Excellent transferability |

Organic Liquids and Membranes

Table 2: Force field performance for diisopropyl ether (DIPE) and related systems [5]

| Force Field | Density Deviation | Viscosity Deviation | Interfacial Tension | Mutual Solubility | Partition Coefficients | Recommended Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GAFF | +3% to +5% | +60% to +130% | Not assessed | Not assessed | Not assessed | Not recommended for transport properties |

| OPLS-AA/CM1A | +3% to +5% | +60% to +130% | Not assessed | Not assessed | Not assessed | Not recommended for transport properties |

| COMPASS | <±1% | <±15% | Good agreement with experiments | Reasonable prediction | Good agreement with experiments | Acceptable for membrane systems |

| CHARMM36 | <±1% | <±15% | Best agreement with experiments | Best prediction | Best agreement with experiments | Recommended for liquid membranes |

Biological Nanopores

Table 3: Force field comparison for ionic and electroosmotic flows in biological nanopores [14]

| Force Field | Cation-Anion Selectivity | Electroosmotic Flow Direction | Flow Magnitude | Ion Conductivity | Viscosity | Consistency Across Systems |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CHARMM36 (+TIP3P) | Coherent across force fields | Coherent across force fields | Quantitative differences | Varies significantly | Varies significantly | Good for wider pores |

| Amber-ff14SB (+TIP3P) | Coherent across force fields | Coherent across force fields | Quantitative differences | Varies significantly | Varies significantly | Good for wider pores |

| Amber-ff19SB (+OPC) | Coherent across force fields | Coherent across force fields | Quantitative differences | Varies significantly | Varies significantly | Significant differences in narrow pores |

Experimental Protocols for Force Field Benchmarking

Standardized Workflow for Transport Property Calculation

Property-Specific Methodologies

Diffusion Coefficient Calculations

Self-diffusion coefficients are typically calculated using the Einstein relation from mean squared displacement (MSD) data [2]. The standard protocol involves:

- Production MD: Run extended NVT simulations (typically 1-10 ns depending on system size and temperature) after thorough equilibration.

- Trajectory Analysis: Calculate MSD for each atom type using

MSD = ⟨|r(t) - r(0)|²⟩where r(t) is the position at time t. - Linear Regression: Fit the MSD curve in the diffusive regime (typically after initial ballistic motion) using

MSD = 6Dt + C, where D is the self-diffusion coefficient. - Averaging: Average results over multiple time origins and all atoms of the same type to improve statistics.

For ionic systems, both cation and anion diffusion coefficients should be calculated separately, as their relationship determines overall conductivity [15].

Viscosity Calculations

Shear viscosity is most accurately calculated using the Green-Kubo formalism, which relates viscosity to the integral of the stress autocorrelation function [5]:

- Stress Tensor Collection: During production MD, save the full pressure tensor (including off-diagonal components) at high frequency (every 1-10 fs).

- Autocorrelation Calculation: Compute the autocorrelation function of the pressure tensor elements:

C(t) = ⟨P_ab(t)P_ab(0)⟩where a and b denote Cartesian components. - Integration: Calculate viscosity from

η = (V/kBT) ∫ C(t) dtwhere V is volume, kB is Boltzmann's constant, and T is temperature. - Averaging: Average results over all independent off-diagonal components (xy, xz, yz) and multiple time origins.

For complex systems, running multiple independent replicas is recommended to obtain reliable error estimates.

Ionic Conductivity Calculations

Ionic conductivity can be computed via two primary approaches [2] [15]:

A. Einstein-Based Approach:

- Calculate the mean squared displacement of the collective ion displacement vector.

- Apply the relationship

σ = (e²/6VkBT) * d/dt ⟨[∑ z_i (r_i(t) - r_i(0))]²⟩where zi is the ion charge and ri is its position. - This approach naturally includes the effect of ion-ion correlations.

B. Green-Kubo Approach:

- Calculate the current autocorrelation function:

C(t) = ⟨J(t) · J(0)⟩whereJ(t) = ∑ z_i v_i(t)is the total current. - Integrate to obtain conductivity:

σ = (1/3VkBT) ∫ C(t) dt. - This method is particularly sensitive to statistical quality and requires long simulation times.

The Nernst-Einstein approximation, which neglects ion correlations, often overestimates conductivity and should be used with caution, particularly in confined systems [15].

Emerging Methods: Neural Network Force Fields

Traditional force fields show limitations in transferability and accuracy, particularly for complex charged fluids and systems with significant electronic polarization effects. Neural network force fields (NNFF) have emerged as promising alternatives that combine near-quantum accuracy with classical MD efficiency [16] [15].

NNFF Performance Advantages

Recent studies demonstrate that NNFFs successfully address pathological deficiencies in classical force field simulations:

- Improved Dynamic Properties: NeuralIL, a neural network potential for ionic liquids, correctly predicts transport properties where classical non-polarizable force fields fail, accurately capturing hydrogen bonding dynamics and proton transfer reactions [16].

- Accurate Confined System Modeling: For aqueous NaCl in graphene slit pores, NNFFs reveal that ionic conductivity decreases under nanoconfinement, a trend governed by changes in both ion self-diffusion and dynamic ion-ion correlations [15].

- Electronic Effects: NNFFs naturally capture polarization and charge transfer effects without explicit parameterization, overcoming a fundamental limitation of fixed-charge force fields [16].

Implementation Workflow for NNFFs

Table 4: Key computational tools for force field benchmarking studies

| Resource Category | Specific Tools | Primary Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| MD Simulation Engines | LAMMPS, GROMACS, NAMD | Molecular dynamics trajectory generation | LAMMPS preferred for materials science; GROMACS for biomolecules [17] [18] |

| Force Field Libraries | CHARMM, AMBER, OPLS, GAFF, COMPASS | Parameter sets for different molecule classes | CHARMM36 shows good performance for organic membranes [5] |

| Quantum Chemistry Codes | VASP, Quantum ESPRESSO, ABACUS | Reference calculations for training NNFFs | Essential for generating training data [17] |

| Workflow Management | APEX, Dflow, Pyiron | Automated property calculation workflows | APEX enables high-throughput screening [17] |

| Analysis Tools | Pymatgen, VASPKIT, PLUMED | Trajectory analysis and enhanced sampling | Critical for extracting transport properties [17] [18] |

| Visualization Software | VMD, OVITO, MayaVi | Molecular structure and property visualization | Important for qualitative assessment and figure generation |

This comparison guide demonstrates that force field selection profoundly impacts the accuracy of transport property predictions in molecular dynamics simulations. For oxide melt systems, Bouhadja's force field outperforms alternatives for dynamic properties, while in organic membrane systems, CHARMM36 and COMPASS provide superior performance for ether-based liquids. In biological nanopores, significant variations exist between force fields, particularly under tight confinement.

The emergence of machine learning force fields represents a paradigm shift, offering quantum-chemical accuracy while maintaining computational feasibility for large systems. As these methods continue to mature, they promise to resolve longstanding challenges in simulating complex charged fluids and confined systems. However, traditional empirical force fields remain valuable for many applications, particularly when selected based on comprehensive benchmarking studies like those presented here.

Future directions in the field include the development of standardized benchmarking protocols, increased integration of automated workflow platforms like APEX, and continued refinement of neural network potentials through active learning approaches. By carefully selecting force fields based on their validated performance for specific systems and properties, researchers can significantly enhance the reliability of their molecular simulations for predicting diffusion, viscosity, and ionic conductivity.

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations serve as a cornerstone tool for investigating the structural and transport properties of complex molecular systems across chemistry, materials science, and biology. The predictive accuracy of these simulations is critically dependent on the quality of the empirical force fields that describe interatomic interactions. This guide provides a systematic comparison of force field performance for three distinct classes of materials—polymers, ionic liquids, and biological nanopores—focusing specifically on their ability to reproduce experimental transport properties. Accurate modeling of these properties is essential for applications ranging from industrial polymer processing and electrochemical device design to single-molecule sensing.

Force Field Benchmarking for Polymers

Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) as a Model System

Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) is a widely used silicon-based polymer recognized for its unique thermal stability, viscoelasticity, and biocompatibility. Its properties present a rigorous test for force field parameterization, requiring accurate modeling of flexible siloxane backbones and diverse intermolecular interactions.

Table 1: Comparison of Force Fields for Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS)

| Force Field | Type | Key Features / Parametrization Basis | Performance on Thermodynamic Properties (Density, Heat Capacity) | Performance on Transport Properties (Viscosity, Thermal Conductivity) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OPLS-AA | All-Atom (AA) | Class I; universal force field for organic liquids; partial charges recalculated for PDMS [10]. | Moderate accuracy [10]. | Significant discrepancies common [10]. |

| Dreiding | All-Atom (AA) | Class I; universal force field; includes H-bond interactions [10]. | Moderate accuracy [10]. | Significant discrepancies common [10]. |

| COMPASS | All-Atom (AA) | Class II; universal force field; includes specific parametrization for siloxane environments [10]. | Good agreement with experimental density and heat capacity [10]. | Varies; generally more reliable than Class I FFs [10]. |

| Huang's Model | All-Atom (AA) | Class II; specifically parametrized for PDMS using bottom-up (QM) and top-down (experimental) data [10]. | Excellent agreement with experimental data [10]. | Superior performance in predicting viscosity and thermal conductivity [10]. |

| Frischknecht (UA) | United-Atom (UA) | Hybrid Class I/II; specifically parametrized for PDMS; faster computation [10]. | Good agreement with structural and pressure properties [10]. | Good performance reported [10]. |

Experimental Protocols for Polymer Force Field Validation

The benchmarking of PDMS force fields involves well-defined computational and experimental procedures to assess a wide range of properties [10].

- System Preparation: Initial configurations are created by randomly placing multiple PDMS polymer chains (e.g., 20 chains of 30 monomers each) in a simulation box using tools like Packmol to mimic the liquid state.

- Equilibration Protocol: The system is first energy-minimized. It is then equilibrated in the isothermal-isobaric (NPT) ensemble at the target temperature (e.g., 300 K) and pressure (1 atm) until the density and total energy converge to stable values. This ensures the system has reached a realistic equilibrium state.

- Production Simulation: Following equilibration, a production run is performed in the canonical (NVT) or microcanonical (NVE) ensemble to generate trajectory data for property calculation.

- Property Calculation:

- Density: Directly measured from the average simulation box volume during the NPT ensemble.

- Self-Diffusion Coefficient: Calculated from the mean-squared displacement of polymer chains using the Einstein relation.

- Viscosity: Computed using the Green-Kubo relation, which integrates the autocorrelation function of the off-diagonal elements of the pressure tensor, or via non-equilibrium MD methods.

- Thermal Conductivity: Determined using the Green-Kubo approach by integrating the heat current autocorrelation function.

Figure 1: Workflow for benchmarking polymer force fields through molecular dynamics simulations.

Force Field Benchmarking for Ionic Liquids

All-Atom and Coarse-Grained Challenges

Ionic liquids (ILs) are salts in the liquid state at room temperature, characterized by complex nanostructures arising from Coulombic, hydrogen-bonding, and van der Waals interactions. Their high viscosity and compositional diversity make force field development challenging [19] [20].

Table 2: Comparison of All-Atom Force Fields for Ionic Liquids ([C4mim][BF4])

| Force Field | Type | Density (kg/m³) at 298 K | Cation Diffusion (10â»Â¹Â¹ m²/s) at 343 K | Key Features / Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OPLS-based | All-Atom | 1178 [19] | 7.3 [19] | Original version; often requires charge scaling for accurate dynamics [19]. |

| 0.8*OPLS | All-Atom | 1150 [19] | 43.1 [19] | Refined OPLS with 0.8 charge scaling factor; improves dynamics [19]. |

| SAPT-based | All-Atom | 1180 [19] | 1.1 [19] | Parametrized from Symmetry-Adapted Perturbation Theory calculations [19]. |

| CL&P | All-Atom | 1154 [19] | 1.19 [19] | Specifically developed for ILs [19]. |

| AMOEBA-IL | Polarizable All-Atom | 1229 (at 313 K) [19] | 2.9 [19] | Includes polarization effects via induced atomic dipoles [19]. |

| APPLE&P | All-Atom | 1193 [19] | 1.01 [19] | Known for good accuracy across various ILs and properties [19]. |

| Experimental Data | --- | ~1170 [19] | ~40.0 [19] | Reference values for validation [19]. |

Advanced Modeling Techniques for Ionic Liquids

Given the computational cost of AA models for large systems, coarse-grained (CG) models are often employed. Furthermore, incorporating polarization is critical for an accurate description of IL properties [19].

- Coarse-Grained (CG) Models: CG models, such as those based on the MARTINI framework, group multiple atoms into a single interaction site. This dramatically increases computational efficiency and allows access to larger spatial and temporal scales. Parameterization can follow a "top-down" approach (fitting to macroscopic experimental data) or a "bottom-up" approach (matching statistics from AA simulations, e.g., using Inverse Boltzmann Inversion or force-matching) [19].

- Polarizable Models: The polar nature of ILs means that the electronic environment of an ion is significantly influenced by its neighbors. Polarizable force fields account for this by using methods like the Drude oscillator model or induced dipoles, which lead to more accurate predictions of dynamic properties like diffusion and conductivity compared to fixed-charge models [19].

- Machine Learning Potentials: Emerging as a powerful tool, ML potentials can approach quantum-level accuracy while retaining computational efficiency comparable to classical force fields. They can be trained on data from Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations and experimental observables to correct known inaccuracies of the underlying quantum method [21].

Force Field Benchmarking for Biological Nanopores

Proteins in Hybrid Ordered-Disordered Systems

Biological nanopores are protein channels that facilitate transport across cell membranes. They are prime targets for MD simulation due to their application in single-molecule sensing, including DNA sequencing and protein analysis. Accurate simulation of these systems is challenging as they often contain both well-structured domains and intrinsically disordered regions (IDRs) with highly diverse dynamics [22] [23].

- Structured vs. Disordered Regions: Traditional force fields like Amber99SB-ILDN and CHARMM22/27 were primarily optimized for folded, globular proteins. When applied to IDRs, they often produce overly compact structures that do not match experimental data from techniques like NMR and SAXS, a problem linked partly to the water model used (e.g., TIP3P) [22] [24].

- Improved Force Fields and Water Models: Modern force fields such as CHARMM36m and combinations like Amber99SB-ILDN with the TIP4P-D water model have shown significant improvement. The TIP4P-D water model, in particular, was found to prevent artificial structural collapse in IDRs and yield more realistic NMR relaxation properties [22].

- Validation with NMR Relaxation: NMR relaxation parameters (Râ‚, Râ‚‚, and NOE) are highly sensitive to ps-ns timescale dynamics and are therefore a critical benchmark for force field performance on hybrid proteins. Accurate prediction of these parameters is a stringent test of a force field's ability to capture the dynamics of both ordered and disordered regions [22].

Table 3: Performance of Force Fields for Proteins with Structured and Disordered Regions

| Force Field & Water Model Combination | Performance on Structured Domains | Performance on Disordered Regions | Ability to Retain Transient Helical Motifs | Overall Recommendation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A99/TIP3P | Good [22] | Poor (artificial collapse) [22] | Variable [22] | Not recommended for IDPs/hybrids [22]. |

| A99/TIP4P-D | Good [22] | Good (improved expansion) [22] | Improved [22] | Recommended [22]. |

| C22*/TIP3P | Good [22] | Poor to Moderate [22] | Variable [22] | Not recommended [22]. |

| C22*/TIP4P-D | Good [22] | Good [22] | Good [22] | Recommended [22]. |

| C36m/TIP3P | Good [22] | Moderate [22] | Best [22] | Good, but water model matters [22]. |

| C36m/TIP4P-D | Good [22] | Good [22] | Best [22] | Highly Recommended [22]. |

Experimental Protocols for Nanopore Force Field Validation

Benchmarking force fields for biological nanopores and hybrid proteins relies heavily on comparing simulation outputs with high-resolution experimental data [22].

- System Setup: The protein of interest is solvated in a water box (e.g., a rhombic dodecahedron) with a minimum distance between the protein and box edge (e.g., 2 nm). The system is neutralized with counterions, and salt concentration is adjusted to match experimental conditions (e.g., 100 mM NaCl). Periodic boundary conditions are applied.

- Simulation Parameters: Simulations are typically performed using a 2 fs time step with bonds involving hydrogen atoms constrained. Long-range electrostatics are treated with particle mesh Ewald (PME). Temperature and pressure are controlled using coupling algorithms (e.g., Nosé-Hoover, Parrinello-Rahman).

- Equilibration and Production: The system undergoes step-wise energy minimization and equilibration first with positional restraints on protein heavy atoms (to relax solvent and ions), and then without restraints. A production simulation of microsecond duration is typically required to adequately sample the conformations of disordered regions.

- Validation against Experimental Data:

- Small-Angle X-ray Scattering (SAXS): The theoretical scattering profile is calculated from the MD trajectory and compared to experimental data, with the radius of gyration (Rg) being a key parameter.

- NMR Spectroscopy: A multitude of NMR observables can be predicted and compared:

- Chemical Shifts: Calculated directly from trajectory structures using empirical predictors like SHIFTX/SPARTA+.

- Residual Dipolar Couplings (RDCs): Calculated from the average orientation of bond vectors relative to a global alignment tensor.

- Paramagnetic Relaxation Enhancement (PRE): Calculated from the distance between a paramagnetic label and nuclear spins.

- Relaxation Rates (Râ‚, Râ‚‚) and NOE: Calculated from the autocorrelation function of bond vector fluctuations (e.g., N-H vector), providing insight into picosecond-to-nanosecond dynamics.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Key Reagents and Computational Tools for Force Field Benchmarking

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Purpose | Example Systems / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| CHARMM36m | All-atom force field for proteins. | Particularly good for proteins with disordered regions and membrane proteins like nanopores [22]. |

| Amber99SB-ILDN | All-atom force field for proteins. | Often used as a base; performance improved with better water models [22]. |

| TIP4P-D | Water model. | Corrects for deficiencies in TIP3P; reduces collapse in intrinsically disordered proteins [22]. |

| Huang's PDMS FF | All-atom, class II force field for polymers. | Specifically parametrized for polydimethylsiloxane; shows superior performance [10]. |

| APPLE&P | Force field for ionic liquids. | Known for its general accuracy and reliability across various IL properties [19]. |

| LAMMPS | Molecular dynamics simulation package. | Widely used for polymers, inorganic systems, and coarse-grained models [10]. |

| GROMACS | Molecular dynamics simulation package. | Very common in the academic community for biomolecular simulations [22]. |

| Packmol | Software for building initial configurations. | Used to pack polymer chains or molecules into simulation boxes [10]. |

| 18-carboxy dinor Leukotriene B4 | 18-carboxy dinor Leukotriene B4 | Research Biomarker | 18-carboxy dinor Leukotriene B4: A key LTB4 metabolite biomarker for inflammation & immunology research. For Research Use Only. Not for human use. |

| 1-Palmitoyl-d9-2-hydroxy-sn-glycero-3-PE | 1-Palmitoyl-d9-2-hydroxy-sn-glycero-3-PE|Lysophospholipid | 1-Palmitoyl-d9-2-hydroxy-sn-glycero-3-PE, a deuterated lysophosphatidylethanolamine internal standard. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

Figure 2: The iterative cycle of force field validation, where simulation predictions are constantly compared against experimental benchmarks.

The benchmarking studies reviewed in this guide consistently demonstrate that the choice of force field is profoundly system-dependent and critically influences the accuracy of predicted transport and structural properties. Key findings indicate that system-specific force fields (e.g., Huang's for PDMS, APPLE&P for ILs) generally outperform universal models. For complex biological systems like hybrid proteins with disordered regions, the combination of a modern force field (CHARMM36m) with an appropriate water model (TIP4P-D) is essential. Furthermore, incorporating polarization effects for ionic liquids and using advanced machine-learning potentials trained on both quantum mechanical and experimental data represent the forefront of achieving higher accuracy across all classes of materials. As the field progresses, systematic validation against a broad set of experimental data remains the gold standard for evaluating and developing trustworthy force fields for molecular simulations.

In computational chemistry and materials science, force fields are fundamental for molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, enabling the prediction of properties and behaviors at the atomic scale. However, the selection of a force field is not a neutral decision; it is a critical parameter that can fundamentally alter the outcome of a simulation. This guide provides a systematic, objective comparison of various force fields, benchmarking their performance primarily on transport properties—such as diffusion and viscosity—which are highly sensitive to the underlying potential energy surface. Supported by quantitative data and detailed experimental protocols, this analysis aims to equip researchers with the evidence needed to select the most appropriate model for their specific systems, particularly in materials science and drug development contexts.

Force Field Performance at a Glance

The table below summarizes the performance of several prominent force fields across different material systems and key properties, highlighting the specific nature of their discrepancies.

| Force Field | Material System | Key Performance Findings | Magnitude of Discrepancy | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GAFF | Diisopropyl Ether (DIPE) Liquid Membrane | Overestimated density and shear viscosity. | Density: +3-5%Viscosity: +60-130% | [5] |

| OPLS-AA/CM1A | Diisopropyl Ether (DIPE) Liquid Membrane | Overestimated density and shear viscosity. | Density: +3-5%Viscosity: +60-130% | [5] |

| CHARMM36 | Diisopropyl Ether (DIPE) Liquid Membrane | Accurate density and viscosity; recommended for ether-based membranes. | Accurate density & viscosity | [5] |

| COMPASS | Diisopropyl Ether (DIPE) Liquid Membrane | Quite accurate density and viscosity. | Accurate density & viscosity | [5] |

| ff99SB | Alanine Peptides (Ala3, Ala5) in Water | Excellent agreement with NMR data; performance depends on water model. | Accurate NMR observables | [25] |

| MACE Scratch | Cr-doped Sb₂Te₃ (2D Material) | Catastrophic failure predicting migration barrier; poor extrapolation. | Overestimated barrier by >4 eV | [26] |

| MACE Foundation | Cr-doped Sb₂Te₃ (2D Material) | Qualitatively plausible but quantitatively inaccurate barrier. | Overestimated barrier by ~0.7 eV | [26] |

| MACE Fine-Tuned | Cr-doped Sb₂Te₃ (2D Material) | Dramatically improved barrier prediction after specialization. | Accurate barrier prediction | [26] |

Quantitative Discrepancies in Key Properties

Density and Shear Viscosity

For liquid membranes, thermodynamic and transport properties are critical. A comparison of four all-atom force fields for modeling diisopropyl ether (DIPE) revealed significant differences in predicting density and shear viscosity [5].

- GAFF & OPLS-AA/CM1A: Both overestimated the density of DIPE across a temperature range of 243–333 K by 3-5% and, more dramatically, the shear viscosity by 60-130% [5].

- CHARMM36 & COMPASS: These force fields yielded quite accurate values for both density and viscosity, with CHARMM36 emerging as the most suitable for modeling ether-based liquid membranes, especially for subsequent studies on ion transport [5].

Kinetic Migration Barriers

Beyond equilibrium properties, force fields can show starkly different performances when predicting kinetic barriers, which are governed by high-energy, rarely sampled states.

- In a study on Cr-intercalated Sb₂Te₃, a specialist MACE model trained from scratch on 20,000 configurations catastrophically failed, overestimating a key migration energy barrier by over 4 eV compared to the DFT-calculated barrier of 0.34 eV. This highlights a classic failure of extrapolation [26].

- A generalist MACE foundation model performed better, capturing the correct shape of the energy pathway but still overestimating the barrier by approximately 0.7 eV, a significant error that could alter conclusions about reaction rates [26].

- Fine-tuning the foundation model with a small amount (5%) of targeted, task-specific data resulted in a dramatic improvement, demonstrating that the choice of training strategy is as crucial as the choice of force field architecture itself [26].

NMR Observables and Secondary Structure

For biomolecular systems, agreement with Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) data is a key benchmark.

- The ff99SB force field has shown excellent agreement with experimental NMR order parameters and residual dipolar couplings for proteins like ubiquitin [25].

- However, its performance on short polyalanine peptides (Ala₃ and Ala₅) is more nuanced. When evaluated using J-coupling constants, the force field, in combination with the TIP4P-Ew water model, ranks among the best available, though its ensemble shows a slight shift away from favored polyproline II (PPII) conformations towards more β-like conformations [25].

- This case also underscores the impact of ancillary choices; the water model (TIP3P vs. TIP4P-Ew) and the selection of Karplus parameters for converting dihedral angles to J-couplings can measurably affect the agreement with experiment [25].

Experimental Protocols for Benchmarking

To ensure reproducible and meaningful comparisons, researchers should adhere to detailed experimental protocols. The following methodologies are adapted from the studies cited in this guide.

Molecular Dynamics for Transport Properties

Objective: To calculate the equilibrium density and shear viscosity of a liquid (e.g., Diisopropyl Ether) across a temperature range [5].

- System Preparation: Construct initial configurations (e.g., 64 cubic unit cells with 3375 DIPE molecules for density calculations). For viscosity, use multiple independent cells to improve statistics [5].

- Simulation Details:

- Software: GROMACS, LAMMPS, or similar MD packages.

- Ensemble: Use the NpT ensemble for density calculations to allow volume change. For shear viscosity, the NVT ensemble is typically used.

- Thermostat/Barostat: Employ a Nosé-Hoover thermostat and barostat for reliable temperature and pressure control.

- Integration Time Step: 1-2 fs.

- Production Run: After thorough energy minimization and equilibration, run production simulations for a sufficient duration (e.g., >50 ns) to achieve converged properties.

- Property Calculation:

- Density: Calculate directly as the average mass per volume over the production trajectory.

- Shear Viscosity: Compute using the Green-Kubo relation, which integrates the stress autocorrelation function, or via the non-equilibrium Einstein-Haddock method.

NMR Observable Validation

Objective: To validate a biomolecular force field by comparing simulated NMR observables, such as J-coupling constants, against experimental data [25].

- System Setup:

- Peptide Solvation: Solvate the peptide (e.g., Alaâ‚…) in a water box (e.g., TIP3P, TIP4P-Ew) with a minimum distance between the peptide and box edge.

- Ion Addition: Add ions to neutralize the system's charge.

- Simulation Details:

- Enhanced Sampling: For small, floppy peptides, use replica-exchange molecular dynamics (REMD) to achieve adequate conformational sampling.

- Simulation Length: Run simulations for a sufficient time per replica (e.g., 50 ns/replica) to ensure convergence of the conformational ensemble.

- Data Analysis:

- Trajectory Analysis: From the simulation trajectory, extract a large ensemble of backbone dihedral angles (ϕ, ψ).

- J-Coupling Calculation: Convert the dihedral angles into J-coupling constants using empirical Karplus equations (e.g., DFT1, DFT2, or "Original" parameter sets) [25].

- Validation Metric: Calculate a χ² value that quantifies the sum of deviations between each calculated J-coupling constant and its experimental value, normalized by assumed systematic error [25].

Migration Barrier Calculation

Objective: To evaluate a force field's ability to predict energy barriers for atomic migration, a stringent test of its extrapolation capability [26].

- Reference Data Generation:

- Use Density Functional Theory (DFT) to calculate the minimum energy pathway (MEP) for the migration event using the Nudged Elastic Band (NEB) method. This serves as the ground truth.

- Force Field Evaluation:

- Single-Point Energy Calculation: Using the fixed geometric images from the DFT-NEB trajectory, perform single-point energy calculations with the machine-learned or classical force field.

- Decoupling Energetics from Relaxation: This step isolates the model's accuracy in representing the potential energy surface from its structural relaxation behavior [26].

- Analysis:

- Compare the energy profile and the predicted migration barrier (Eâ‚) from the force field directly against the DFT reference.

Visualizing Benchmarking Relationships and Workflows

Force Field Benchmarking Framework

This diagram illustrates the logical framework and primary relationships involved in a systematic force field benchmarking study, connecting material systems with the properties used for evaluation.

Force Field Selection Logic

This workflow guides researchers through the critical decision-making process of selecting and applying a force field, highlighting the potential for discrepancies and mitigation strategies.

The Scientist's Toolkit

This section details essential computational reagents and resources used in force field benchmarking studies.

Research Reagent Solutions

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function | Key Application in Benchmarking |

|---|---|---|---|

| CHARMM36 | Classical Force Field | Models biomolecules and organic liquids. | Accurate prediction of density and viscosity for ether-based liquid membranes [5]. |

| GAFF | Classical Force Field | General model for organic molecules. | Serves as a baseline; often shows deviations in transport properties [5]. |

| ff99SB | Classical Force Field | Specialized for protein simulations. | Validation against NMR observables for peptides and proteins [25]. |

| MACE | Machine-Learning Force Field | Architecture for high-dimensional neural network potentials. | Benchmarking specialist vs. generalist models for solid-state materials [26]. |

| Nudged Elastic Band | Computational Algorithm | Finds minimum energy paths and transition states. | Probing kinetic migration barriers to test force field extrapolation [26]. |

| Green-Kubo Formalism | Mathematical Relation | Calculates transport properties from equilibrium MD. | Computing shear viscosity from stress autocorrelation functions [5]. |

| Karplus Equations | Empirical Relation | Converts dihedral angles to NMR J-couplings. | Validating conformational ensembles from biomolecular simulations [25]. |

| UniFFBench | Benchmarking Framework | Evaluates force fields against experimental data. | Systematic testing of universal MLFFs on mineral structures [27]. |

| 1,2-Dioleoyl-3-linoleoyl-rac-glycerol | 1,2-Dioleoyl-3-linoleoyl-rac-glycerol, MF:C57H102O6, MW:883.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| 11-Dehydroxyisomogroside V | 11-Dehydroxyisomogroside V, MF:C60H102O29, MW:1287.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Methodologies for Benchmarking Force Fields Across Material Systems

The development of high-performance solid polymer electrolytes (SPEs) is pivotal for advancing safe, energy-dense batteries. Understanding the intricate relationship between molecular structure, ion transport mechanisms, and macroscopic properties represents a fundamental challenge in this field. Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations have emerged as a powerful tool for probing these structure-transport relationships at the molecular level, enabling computational screening and design of novel materials. However, the accuracy of these simulations critically depends on the choice of force fields and simulation methodologies. This guide establishes a comprehensive benchmarking framework for evaluating classical force fields in predicting lithium-ion transport properties, providing researchers with standardized protocols for assessing simulation accuracy against experimental data. The framework addresses key aspects including force field parameterization, convergence criteria, and the impact of dynamic bonding phenomena on transport mechanisms.

Force Field Benchmarking: Methodologies and Protocols

Force Field Parameterization and Charge Scaling

Accurate force field parameterization is foundational for reliable MD simulations of polymer electrolytes. A critical finding across multiple studies is that non-polarizable force fields systematically overestimate ion-polymer binding energies when using formal ion charges, necessitating empirical charge scaling to achieve agreement with experimental diffusivity measurements.

Charge Scaling Protocol: For lithium ions (Liâº), systematic parameter optimization against first-principles quantum-mechanical calculations justifies a charge scaling factor of approximately 0.79 for the OPLS force field applied to Liâº-TFSIâ»-PEO systems [28]. This scaling factor emerges consistently across different Liâº:EO ratios (1:10 and 1:20) and temperatures (300-373 K), demonstrating transferability within poly(ethylene oxide)-based electrolytes [28]. The parameter optimization process employs force-matching techniques that iteratively refine parameters to minimize the difference between force field forces and reference quantum-mechanical forces, typically achieving objective functions of 10-12% upon convergence [28].

Van der Waals Parameter Optimization: Concurrent optimization of Lennard-Jones parameters for Li-O (PEO) and Li-O (TFSIâ») interactions is essential, with optimized values of σ~2.40-2.42 Ã… and ε~0.05-0.06 kcal/mol for Li-O(PEO) and σ~2.31-2.33 Ã… and ε~0.07 kcal/mol for Li-O(TFSIâ») [28]. These refined parameters complement charge scaling to accurately capture ion coordination and dynamics.

Table 1: Optimized Force Field Parameters for Liâº-TFSIâ»-PEO Systems

| Parameter | Original OPLS | Optimized Value | Convergence Objective |

|---|---|---|---|

| Li⺠Charge Scaling | 1.0 | 0.79 | 10.7-10.9% |

| σ Li-O(PEO) (Å) | 2.48 | 2.40-2.42 | 10.7-10.9% |

| ε Li-O(PEO) (kcal/mol) | 0.05 | 0.05-0.06 | 10.7-10.9% |

| σ Li-O(TFSIâ») (Ã…) | 2.51 | 2.31-2.33 | 10.7-10.9% |

| ε Li-O(TFSIâ») (kcal/mol) | 0.06 | 0.07 | 10.7-10.9% |

Simulation Convergence and Time Scales

MD simulations of polymer electrolytes require careful attention to convergence, as ion transport in these viscoelastic materials occurs over extended time scales. Benchmarking studies indicate that simulations spanning several hundreds of nanoseconds are necessary to approach the diffusive regime for Liâº, even at elevated temperatures [28]. The convergence of transport properties should be systematically evaluated by monitoring the mean-squared displacement (MSD) of ions as a function of simulation time, ensuring linear behavior indicative of diffusive transport.

The diffusion coefficient (D) is calculated from the linear portion of the MSD versus time plot using the Einstein relation: $$D = \frac{1}{6Nt} \left\langle \sum{i=1}^{N} [ri(t) - r_i(0)]^2 \right\rangle$$ where N is the number of ions, ráµ¢(t) is the position of ion i at time t, and the angle brackets denote ensemble averaging [29]. Statistical uncertainty should be quantified through block averaging or multiple independent simulations.

Dynamic Bonding and Novel Transport Mechanisms

Beyond conventional PEO-based electrolytes, recent research has uncovered unique ion transport mechanisms in dynamic covalent adaptable networks (CANs). These systems exhibit fundamentally different structure-transport relationships compared to static polymer networks.

In CANs featuring dynamic disulfide bonds, bond exchange reactions create temporary "corridors" for lithium-ion movement through reversible bond breaking and reformation [29]. This dynamic bonding transforms blocked pathways into reversible gates that open and close, enhancing ion mobility up to 2.8-fold in dense networks without altering overall pore distribution [29]. Simulation protocols for these systems require specialized reactive force fields capable of modeling bond exchange events with user-defined exchange probabilities (P_exchange) that control the frequency of dynamic bond exchange [29].

Quantitative Benchmarking Data

Force Field Performance Comparison

Systematic benchmarking across 19 polymer electrolytes reveals the capabilities and limitations of Class 1 force fields in predicting transport properties [30]. The accuracy of diffusion coefficient predictions varies significantly with force field parameterization, with charge-scaled force fields providing substantial improvements over unscaled counterparts.

Table 2: Force Field Performance in Predicting Li⺠Diffusivity

| Force Field Type | Li⺠Diffusion Coefficient | Deviation from Experiment | Optimal Application Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unscaled OPLS (~1.0e) | Underestimated by ~1 order of magnitude | >80% error | Not recommended for quantitative predictions |

| Charge-Scaled OPLS (~0.79e) | Slight underestimation | 20-30% error | Liâº:EO ratios 1:10 to 1:20; 300-373 K |

| Polarizable Force Fields | Closest to experimental values | <15% error | When computational resources permit |

Structure-Transport Relationships Across Polymer Chemistries

The benchmarking framework enables comparative analysis of transport properties across diverse polymer chemistries, revealing clear structure-property relationships.

Table 3: Performance Metrics of Selected Polymer Electrolytes

| Polymer Electrolyte | Ionic Conductivity | Li⺠Transference Number | Activation Energy | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PEO (benchmark) | ~1 mS cmâ»Â¹ at 353 K | ~0.2 | ~8 kJ/mol | [31] |

| ZAF-PEO Composite | 1.37 mS cmâ»Â¹ at 333 K | 0.56 | Not reported | [32] |

| Dynamic CANs (disulfide) | Up to 2.8× enhancement vs static | Not reported | Reduced in dense networks | [29] |

| High-Conductivity Generative Designs | >0.506 mS cmâ»Â¹ (top 5%) | Varies | Varies by chemistry | [31] |

The incorporation of zinc-adeninate frameworks (ZAF) into PEO demonstrates how additional hopping sites from carbonyl and hydrogen-bonding functionalities enhance both ionic conductivity (1.37 mS cmâ»Â¹ at 60°C) and lithium-ion transfer number (0.56) [32]. This represents a significant improvement over conventional PEO, which typically exhibits transference numbers of approximately 0.2 [31].

Experimental and Computational Workflows

Molecular Dynamics Simulation Protocol

Standardized MD protocols enable reproducible benchmarking across different research groups and polymer systems:

System Preparation:

- Construct polymer chains with specified molecular weights (typically below entanglement MW ~2000 g/mol for PEO)

- Incorporate salt species at target Liâº:EO ratios (e.g., 1:10 to 1:20)

- Employ periodic boundary conditions in all dimensions

- Utilize energy minimization (steepest descent/conjugate gradient) prior to production runs

Equilibration Protocol:

- NPT equilibration using Parrinello-Rahman barostat (1 bar) and V-rescale thermostat (target temperature)

- Minimum 100 ns equilibration for sufficient chain relaxation

- Monitor convergence of energy, density, and structural properties

Production Simulation:

- Extended simulations (several hundred nanoseconds) to ensure diffusive regime

- Time steps of 1-2 fs for atomistic simulations, 10 fs for coarse-grained

- Trajectory saving intervals of 10-100 ps for subsequent analysis

Analysis Methods:

- Mean-squared displacement calculations for diffusion coefficients

- Radial distribution functions for ion coordination environments

- Van Hove correlation functions for collective ion behavior

- Pore size distribution analysis using tools like PoreBlazer [29]

Reactive Simulation for Dynamic Networks

For CANs with dynamic bonds, specialized reactive MD protocols are required:

Reactive Framework: Implement reactive MD tools like PolySMart built on Martini 3 force field for coarse-grained simulations [29]

Bond Exchange Algorithm:

- Identify disulfide groups within cutoff distance (typically 0.412 nm)

- Generate list of eligible bond pairs for exchange

- Apply exchange probability (P_exchange) to randomly select bonds for exchange

- Update topology information following exchange events

Multi-scale Validation:

- Reverse mapping from coarse-grained to atomistic representations

- Validation of structural and diffusional properties across scales

- Comparison with experimental measurements when available

Visualization of Methodologies and Relationships

Force Field Optimization Workflow

Ion Transport Mechanisms in Dynamic Networks

Research Reagent Solutions Toolkit

Table 4: Essential Computational Tools for Polymer Electrolyte Benchmarking

| Tool/Software | Primary Function | Application Context | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| GROMACS | Molecular Dynamics Engine | Production MD simulations of polymer electrolytes | Optimized for biomolecular/polymer systems, free energy calculations |

| PolySMart | Reactive MD Framework | Modeling dynamic covalent bonds in CANs | Python package for polymerization and crosslinking reactions |

| PoreBlazer v4.0 | Pore Structure Analysis | Quantifying pore size distribution in polymer networks | Calculates PLD, MPD, and PSD parameters |

| OPLS-AA | Force Field | Classical MD with optimized Li⺠parameters | Transferable parameters for organic molecules and polymers |

| Martini 3 | Coarse-Grained Force Field | Large-scale and long-time simulations | Compatible with reactive MD schemes |

| Cimigenoside (Standard) | Cimigenoside (Standard), MF:C35H56O9, MW:620.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| L,L-Dityrosine Hydrochloride | L,L-Dityrosine Hydrochloride, MF:C18H22Cl2N2O6, MW:433.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

This benchmarking framework establishes standardized methodologies for evaluating force field performance in predicting structure-transport relationships of polymer electrolytes. The critical importance of charge scaling (approximately 0.79 for Liâº) and optimized van der Waals parameters emerges as a consistent finding across multiple studies, with charge-scaled force fields improving agreement with experimental diffusivity by approximately one order of magnitude compared to unscaled force fields. Beyond conventional electrolytes, the framework accommodates emerging materials including dynamic covalent adaptable networks, which exhibit unique transport mechanisms mediated by reversible bond exchange. The integration of computational screening approaches with generative machine learning models presents a promising direction for accelerating the discovery of novel polymer electrolytes with enhanced ionic conductivity and mechanical properties. As the field advances, this benchmarking framework provides a foundation for rigorous, reproducible evaluation of simulation methodologies across diverse polymer chemistries and transport phenomena.

Simulating Ionic Liquids and Complex Charged Fluids with Neural Network Force Fields

The accurate simulation of ionic liquids and other complex charged fluids is pivotal for advancing technologies in energy storage, drug development, and materials science. Traditional molecular dynamics (MD) simulations relying on classical, parameterized force fields (FFs) have long struggled to balance computational efficiency with quantum mechanical accuracy, particularly in describing transport properties, polarization effects, and reactive processes [33] [34]. The emergence of machine learning force fields (MLFFs) marks a transformative development, offering the potential to perform large-scale molecular dynamics simulations with density functional theory (DFT) level accuracy [35] [36]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of current neural network force field (NNFF) methodologies, evaluating their performance against classical and ab initio alternatives. We focus on benchmarking their capabilities for predicting key properties—such as viscosity, ionic conductivity, and diffusion—within a broader thesis on computational transport properties research, providing researchers with the data and protocols needed to select appropriate tools for their specific applications.

Neural network force fields represent a paradigm shift from traditional FF design. Instead of using predefined mathematical forms with fitted parameters, NNFFs learn the complex relationship between atomic configurations and energies/forces directly from quantum mechanical data [34]. Several distinct architectural approaches have been developed:

- Bayesian-Based MLFFs: As applied to imidazolium-based ionic liquids, these methods successfully accelerate MD simulation while matching the accuracy of first-principles calculations for atomic forces, structures, and vibrational behaviors. They enable property prediction across extended scales of temperature and concentration [33].

- Deep Potential (DP) Schemes: Frameworks like the EMFF-2025 model for energetic materials demonstrate exceptional capabilities in modeling complex reactive chemical processes and large-scale system simulations, achieving DFT-level accuracy for both mechanical properties and chemical reactivity [35].

- Committee Neural Networks: Implemented in tools like NeuralIL, this approach uses multiple networks to estimate prediction uncertainty and can be iteratively refined with configurations from ML-MD simulations to significantly improve force prediction accuracy [34].

- Equivariant Architectures: Models such as Egret-1, based on the MACE architecture, incorporate physical symmetries (rotation, translation, permutation) directly into the network design, enhancing accuracy for organic and biomolecular systems [37].

Table 1: Key Neural Network Force Field Architectures for Charged Fluids

| Architecture | Key Features | Representative Models | Target Systems |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bayesian MLFF | Accelerated calculation with uncertainty quantification | Bayesian-based MLFF [33] | Imidazolium-based ILs |

| Deep Potential | Scalable for large systems and reactive processes | EMFF-2025, DP-CHNO-2024 [35] | Energetic materials, CHNO systems |

| Committee Networks | Error estimation through network ensembles | NeuralIL [34] | Pure ILs, IL-salt mixtures |

| Equivariant Graph NN | Built-in physical symmetries | Egret-1 (MACE) [37] | Bioorganic molecules |

| Gaussian Approximation | Smooth Overlap of Atomic Position descriptors | GAP [36] | Molecular liquid mixtures |

A critical challenge in applying NNFFs to molecular liquids is the separation of scale between intense intramolecular interactions and subtle intermolecular forces. As demonstrated in studies of EC:EMC binary solvents—key components of Li-ion batteries—NNFFs must simultaneously capture both interaction types to correctly predict thermodynamic properties like density [36]. Iterative training protocols that continuously refine the training dataset have proven essential for developing stable and accurate potentials for these systems.

Performance Benchmarking: Quantitative Comparisons

Accuracy Against Quantum Chemical Methods

NNFFs demonstrate remarkable accuracy approaching their DFT training data. The EMFF-2025 model for energetic materials exhibits mean absolute errors (MAE) predominantly within ±0.1 eV/atom for energy predictions and ±2 eV/Å for force calculations [35]. Similarly, NeuralIL replicates molecular structures of ionic liquids with bond lengths close to both OPLS-AA and DFT values, while significantly improving the prediction of weak hydrogen bond dynamics that are often poorly described by classical fixed-charge FFs [34].

Transport Property Prediction

Transport properties like viscosity and ionic conductivity present particular challenges for classical FFs, which often underpredict diffusion coefficients and conductivity due to inadequate treatment of polarization effects [34] [38]. NNFFs substantially improve upon these limitations:

Table 2: Performance Comparison for Imidazolium-Based Ionic Liquid [C4mim][BF4] at ~300K

| Method Type | Specific Model | D+ (10â»Â¹Â¹ m²/s) | D- (10â»Â¹Â¹ m²/s) | Viscosity (mPa·s) | Conductivity (S/m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classical FF | OPLS-AA [19] | 7.3 | 6.6 | - | - |

| Polarizable FF | AMOEBA-IL [19] | 2.9 | 0.67 | - | - |

| Scaled-Charge FF | 0.8*OPLS [19] | 43.1 | 42.9 | - | - |

| Machine Learning | ML Potential [19] | 48.58 | 35.49 | - | - |

| Experimental | - | 8.0-40.0 [19] | 8.2-47.6 [19] | - | 0.295 [19] |