Accurate Transport Property Prediction: A Practical Guide to Force Field Selection and Validation

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework for selecting, applying, and validating molecular force fields to achieve accurate predictions of transport properties.

Accurate Transport Property Prediction: A Practical Guide to Force Field Selection and Validation

Abstract

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework for selecting, applying, and validating molecular force fields to achieve accurate predictions of transport properties. Covering foundational principles, methodological applications, troubleshooting strategies, and rigorous validation techniques, it synthesizes current best practices from recent scientific literature. The guidance addresses critical challenges in computational modeling, from balancing accuracy with computational cost to leveraging machine learning for force field optimization, ultimately aiming to enhance the reliability of simulations for drug discovery and materials design.

Understanding Force Field Fundamentals for Transport Properties

The Critical Role of Force Field Selection in Predicting Diffusion and Viscosity

Key Findings from Recent Studies

The table below summarizes findings from recent investigations into how different force fields perform in predicting the transport properties of various liquid systems [1] [2] [3].

| System Studied | Force Fields Compared | Key Performance Findings on Transport Properties |

|---|---|---|

| Diisopropyl Ether (DIPE) Liquid Membranes [1] | GAFF, OPLS-AA/CM1A, CHARMM36, COMPASS | CHARMM36: Most accurate for density & viscosity.GAFF/OPLS-AA: Overestimate density (3-5%) and significantly overestimate viscosity (60-130%).COMPASS: Accurate for density and viscosity. |

| Pure 1-Alkanols (Methanol to 1-Hexanol) [3] | OPLS-AA, TraPPE-UA | TraPPE-UA: Better for self-diffusion coefficients.OPLS-AA: Performs well for shear viscosity but weaker for self-diffusion, especially at low temperatures. |

| CaO-Al(2)O(3)-SiO(_2) Oxide Melts [2] | Matsui, Guillot, Bouhadja | Bouhadja's FF: Best agreement with experimental activation energies and dynamics.Matsui/Guillot FF: Accurately reproduce densities and structural features. |

Troubleshooting Guide: FAQs on Force Fields and Transport Properties

Q1: My MD simulations consistently overestimate the shear viscosity of an organic solvent. What could be the cause?

This is a common issue with certain force fields. A recent study on diisopropyl ether (DIPE) found that the GAFF and OPLS-AA/CM1A force fields overestimated experimental shear viscosity values by 60-130% [1]. The underlying cause is often an imbalance in the parameterization of the force field, where the non-bonded interactions (van der Waals and electrostatic) are too attractive, leading to excessive friction and resistance to flow. To troubleshoot:

- Validate with Density: First, check if your force field accurately reproduces the system's density. An accurate density is a necessary, but not sufficient, condition for accurate transport properties [1].

- Benchmark Force Fields: Compare results from multiple force fields. The solution identified in the DIPE study was to switch to the CHARMM36 force field, which provided excellent agreement with experimental viscosity data [1].

Q2: Which calculation method is more reliable for self-diffusion coefficients: Green-Kubo or Einstein/MSD?

The choice of method can impact your results. Research on 1-alkanols indicates that for self-diffusion coefficients, the Mean Squared Displacement (MSD) method (from the Einstein relation) is generally more accurate and reliable than the Green-Kubo method, which integrates the velocity autocorrelation function [3]. The MSD approach is less susceptible to noise and converges more efficiently for this property. Conversely, for shear viscosity, the Green-Kubo method (which integrates the stress autocorrelation function) is often slightly more accurate, though it requires longer simulation times to achieve good convergence [3].

Q3: How transferable are force fields outside their original parameterization range?

Force field transferability is a significant challenge. A benchmark study on oxide melts demonstrated that performance can vary widely [2]. For example, while Matsui's force field was developed for crystals, it can reproduce some structural features of melts. However, for dynamic properties like self-diffusion and conductivity, Bouhadja's force field showed superior transferability across a wide range of compositions and temperatures, outperforming others that were not specifically optimized for melt dynamics [2]. It is critical to consult recent literature benchmarking force fields for your specific class of materials and properties.

Q4: Why is it important to validate force fields with both thermodynamic and transport properties?

Validating with both types of properties ensures the model is robust and physically realistic. A force field might be parameterized to reproduce thermodynamic data like density with high accuracy. However, as seen with GAFF and OPLS-AA for DIPE, a good density prediction does not guarantee accurate dynamics [1]. Viscosity and diffusion coefficients are sensitive to the free energy landscape and energy barriers between molecular configurations. A force field that accurately captures both structure (density) and kinetics (viscosity/diffusion) provides much greater confidence for predictive simulations of processes like ion transport through membranes [1].

Experimental Protocols for Force Field Benchmarking

This section provides a detailed methodology for benchmarking force fields against experimental transport properties, based on protocols used in the cited research.

Protocol 1: Calculating Shear Viscosity using the Green-Kubo Formalism

The shear viscosity ((\eta)) can be calculated from the integral of the stress autocorrelation function [3].

- System Setup: Build a cubic simulation cell containing a sufficient number of molecules (e.g., 3375 molecules was used for DIPE [1]) to minimize size effects. Energy-minimize the system and equilibrate in the NPT ensemble at the target temperature and pressure to obtain the correct experimental density.

- Production Run: Perform a long production run in the NVE or NVT ensemble. Ensure the simulation is long enough for the stress autocorrelation function to decay to zero.

- Data Collection: During the production run, output the components of the pressure tensor ((P{xy}(t)), (P{xz}(t)), (P_{yz}(t)), and the off-diagonal components of the stress tensor) at every time step or at frequent intervals.

- Analysis:

- Calculate the shear stress autocorrelation function (SACF): ( \langle P{\alpha\beta}(t) \cdot P{\alpha\beta}(0) \rangle ) where (\alpha\beta) represents the xy, xz, yz, xx-yy, and zz-(xx+yy)/2 components.

- Average over all independent components to improve statistics.

- Compute the shear viscosity by integrating the SACF: ( \eta = \frac{V}{kB T} \int0^\infty \langle P{\alpha\beta}(t) \cdot P{\alpha\beta}(0) \rangle \, dt ) where (V) is the volume, (k_B) is Boltzmann's constant, and (T) is the temperature.

Protocol 2: Calculating Self-Diffusion Coefficients using the Einstein Relation

The self-diffusion coefficient ((D)) is calculated from the linear growth of the mean-squared displacement (MSD) [3].

- System Setup and Equilibration: Follow the same steps as in Protocol 1.

- Production Run: Perform a production run in the NVT ensemble. Ensure the total simulation time is several times longer than the characteristic diffusion time of the molecules.

- Data Collection: Output the atomic coordinates every few time steps to have sufficient time resolution for the MSD calculation.

- Analysis:

- Calculate the MSD for the center of mass of each molecule of the same type: ( \text{MSD}(t) = \langle | \vec{r}i(t0 + t) - \vec{r}i(t0) |^2 \rangle ) where the angle brackets denote averaging over all molecules of the same type and over all time origins ((t0)).

- The self-diffusion coefficient is obtained from the slope of the MSD in the diffusive regime: ( D = \frac{1}{2d} \lim{t \to \infty} \frac{d}{dt} \text{MSD}(t) ) where (d) is the dimensionality (3 for bulk systems). In practice, (D) is calculated as ( \frac{1}{6} \times ) slope of the MSD vs. time plot.

Quantitative Data from Key Studies

Table 1: Density and Viscosity Performance for Diisopropyl Ether (DIPE) [1] Performance is quantified as the average deviation from experimental data across a temperature range of 243–333 K.

| Force Field | Density Deviation | Viscosity Deviation |

|---|---|---|

| CHARMM36 | Quite accurate | Quite accurate |

| COMPASS | Quite accurate | Quite accurate |

| GAFF | Overestimated by ~3-5% | Overestimated by ~60-130% |

| OPLS-AA/CM1A | Overestimated by ~3-5% | Overestimated by ~60-130% |

Table 2: Performance for 1-Alkanol Transport Properties [3] Summary of the relative performance of two force fields across multiple 1-alkanols (Methanol to 1-Hexanol).

| Force Field | Self-Diffusion Coefficient | Shear Viscosity |

|---|---|---|

| TraPPE-UA | Better accuracy | -- |

| OPLS-AA | Weaker, especially at low temps | Good performance |

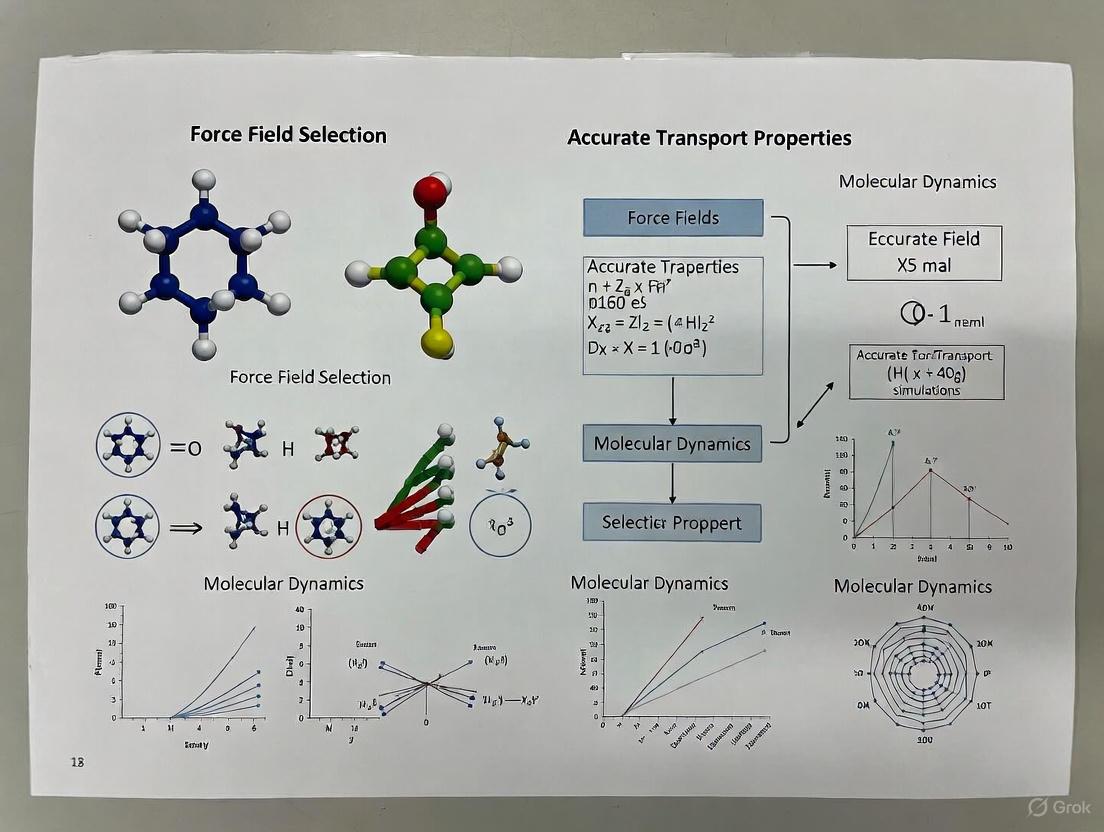

Workflow for Force Field Selection and Validation

The following diagram outlines a systematic workflow for selecting and validating a force field for transport property prediction, based on the best practices identified in the research.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Key Software and Analysis Tools for MD of Transport Properties

| Tool / Component | Function / Description |

|---|---|

| MD Software (GROMACS, LAMMPS, NAMD) | High-performance molecular dynamics packages used to run the simulations. They integrate equations of motion and calculate forces and energies [1] [2] [3]. |

| Force Field Parameter Files (e.g., CHARMM36, GAFF, OPLS-AA) | Files containing the specific parameters (bond lengths, angles, dihedrals, non-bonded interactions) that define the potential energy surface for the system [1] [3]. |

| Green-Kubo Analysis Script | Custom scripts (e.g., in Python) used to post-process the stress autocorrelation function and compute shear viscosity via integration [3]. |

| MSD Analysis Tool | Tools integrated within MD software or standalone scripts to calculate the Mean-Squared Displacement from trajectory data and derive the self-diffusion coefficient [3]. |

| System Builder (Packmol, Moltemplate) | Utilities to create initial configurations of complex molecular systems, such as liquid mixtures or interfaces, for simulation setup [1]. |

| Cinatrin C3 | Cinatrin C3, MF:C18H30O8, MW:374.4 g/mol |

| RMC-3943 | RMC-3943, MF:C18H22Cl2N6S, MW:425.4 g/mol |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

General Principles and Method Selection

Q1: What is the fundamental difference in how Classical MD (CMD) and Ab Initio MD (AIMD) calculate forces? A1: The core difference lies in the treatment of atomic interactions. Classical MD uses pre-defined empirical force fields—mathematical functions with fitted parameters—to calculate forces between atoms [2] [4]. In contrast, Ab Initio MD (also known as first-principles MD) calculates forces on-the-fly by solving the electronic structure of the system, typically using Density Functional Theory (DFT), without relying on empirical parameters [2] [5].

Q2: For a project focused on predicting transport properties like diffusion or viscosity, which method should I choose? A2: The choice involves a direct trade-off between system size/time scale and quantum mechanical accuracy.

- Classical MD is the practical choice for simulating large systems (thousands to millions of atoms) and long time scales (nanoseconds to microseconds) required to observe transport phenomena like diffusion and viscosity [2] [6]. However, its accuracy is entirely dependent on the quality of the force field [2] [7].

- AIMD provides a more rigorous, quantum-mechanically accurate description of bond breaking and formation [4]. However, its extreme computational cost restricts it to small systems (<200-500 atoms) and short timescales (tens of picoseconds), making it unsuitable for directly simulating most bulk transport properties but excellent for validating force fields or studying chemical reactions [2] [5].

Q3: What are Machine Learning Force Fields (MLFFs) and how do they fit into this landscape? A3: Machine Learning Force Fields are a transformative hybrid approach. They are trained on data generated from AIMD simulations, enabling them to achieve near ab initio accuracy while maintaining a computational cost closer to that of Classical MD [8] [5] [9]. They can be 41 times faster than other ML potentials for comparable accuracy and several orders of magnitude faster than DFT, making them a powerful tool for accurate simulations of larger systems [9] [10].

Force Field Selection and Validation

Q4: I am using a general-purpose force field (e.g., OPLS-AA, GAFF) for a novel polymer. What are the key limitations? A4: General-purpose force fields are often poor at describing the torsional potentials along the backbones of conjugated polymers due to delocalized electrons [11]. They may incorrectly predict energy barriers and equilibrium dihedral angles, leading to inaccurate chain conformations and morphologies that critically impact charge transport properties [11]. Reparameterization of backbone dihedrals using ab initio calculations is often necessary [11].

Q5: How can I assess the accuracy and transferability of a force field for my specific material system? A5: A robust validation protocol is essential.

- Benchmark against AIMD or experimental data: Compare key structural properties from your CMD simulations, such as density, radial distribution functions (RDFs), and coordination numbers, against available AIMD data or experimental measurements [2] [6].

- Check dynamic properties: Validate self-diffusion coefficients, viscosity, or electrical conductivity against experimental data, as a force field accurate for structure may not be accurate for dynamics [2] [6].

- Use ensemble methods: Run multiple replicas of your simulation to quantify the uncertainty and ensure your results are reproducible, accounting for the chaotic nature of MD [7].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Poor Agreement with Experimental Transport Properties

Problem: Your CMD simulation of an oxide melt predicts diffusion coefficients or electrical conductivity that are an order of magnitude different from experimental values.

Diagnosis and Solution:

| Step | Action | Technical Details |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Verify Force Field Transferability | The force field may be parameterized for a different composition or temperature. Systematically benchmark its performance for your specific conditions [2]. |

| 2 | Check Force Field Formulation | Compare your results with other published force fields. For CaO-Al2O3-SiO2 melts, Bouhadja's force field was found superior for dynamics over Matsui's or Guillot's [2]. |

| 3 | Validate Underlying Structure | Ensure the force field correctly reproduces local structure (e.g., Al-O and Ca-O coordination numbers) against AIMD data. Incorrect structure leads to incorrect dynamics [2]. |

| 4 | Consider Advanced Methods | If classical FFs fail, use a MLFF trained on AIMD data of your system for a more accurate description of potential energy surfaces [9] [10]. |

Issue 2: Unphysical System Behavior or Simulation Collapse

Problem: The simulation becomes unstable, with energies diverging or bonds breaking unrealistically.

Diagnosis and Solution:

| Step | Action | Technical Details |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Inspect Dihedral Potentials | For conjugated polymers, this is a common issue. Re-parameterize backbone dihedrals (φ1, φ2, φ3) by fitting the FF torsional profile to an ab initio scan, as shown for PCDTBT [11]. |

| 2 | Verify Partial Atomic Charges | Ensure charges are derived to represent a long polymer chain and different conformations, not just an isolated monomer [11]. |

| 3 | Check for Missing Parameters | For non-standard molecules (e.g., with Si-O bonds in OPLS-AA), manually assign or optimize missing parameters (e.g., partial charges) using QEq or DFT methods [6]. |

Issue 3: High Uncertainty in Free Energy Calculations

Problem: Binding free energy estimates from MD simulations have large error bars, making them unreliable for decision-making in drug discovery.

Diagnosis and Solution:

| Step | Action | Technical Details |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Implement Ensemble Simulations | Run a large number of concurrent replicas (e.g., 50-100) with different initial random seeds. This is fundamental for quantifying random (aleatoric) error in chaotic MD systems [7]. |

| 2 | Use Robust Statistical Analysis | From the ensemble of replicas, calculate reliable statistics (mean, standard deviation, confidence intervals) for your quantity of interest (e.g., free energy of binding) [7]. |

| 3 | Control Systematic Errors | Use an explicit solvent model and a modern, validated force field (e.g., OPLS5 with explicit polarizability) to minimize systematic bias in the protein-ligand model [7] [10]. |

Quantitative Data Comparison

The table below summarizes key benchmarks for different force fields and methods, highlighting the trade-off between computational cost and accuracy.

Table 1: Benchmarking of Computational Methods for Material Properties

| Material System | Method / Force Field | Key Properties Validated | Accuracy vs. Experiment/AIMD | Computational Note |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CaO-Al2O3-SiO2 Melts [2] | Bouhadja et al. BMH Potential | Density, Structure, Self-diffusion, Electrical Conductivity | Best agreement with AIMD for structure & exp. for transport | Suitable for ns-scale MD of transport properties. |

| Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) [6] | Huang et al. (Class II) | Density, Heat Capacity, Viscosity, Thermal Conductivity | Good across thermodynamics & transport | Specifically parametrized for PDMS. |

| Cu7PS6 Superionic Conductor [9] | Neuroevolution Potential (NEP) | Phonon DOS, Radial Distribution Functions | High accuracy vs. DFT | 41x faster than Moment Tensor Potential (MTP). |

| Various Proteins [5] | AI2BMD (MLFF) | Protein Energy, Atomic Forces, 3J Couplings, Folding | Matches DFT accuracy, aligns with NMR data | Several orders magnitude faster than DFT for >10,000 atoms. |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Protocol 1: Workflow for Force Field Selection and Validation

This workflow provides a systematic approach for researchers to select and validate a force field for predicting accurate transport properties.

Protocol 2: Ab Initio Parameterization of Torsional Potentials

This protocol details the methodology for reparameterizing torsional angles in a polymer force field to achieve quantum-mechanical accuracy, as applied to PCDTBT [11].

Detailed Methodology:

- Model System Preparation: Create a simplified moiety from the polymer's repeat unit. Remove side chains and saturate bonds with hydrogen atoms.

- Quantum Chemical Optimization: Perform a full geometry optimization using Density Functional Theory (DFT). A long-range corrected functional like LC-ωPBE with a 6-31G(d,p) basis set is recommended for improved torsion barrier heights [11].

- Torsional Potential Scan: Using the optimized structure, perform a series of constrained partial geometry optimizations. Fix the dihedral angle of interest (φ) in increments (e.g., 5°), allowing all other degrees of freedom to relax. Record the single-point energy at each step to generate the ab initio torsional profile, EAI(φ).

- Force Field Optimization: Calculate the force field energy profile, EFF(φ), which includes contributions from all terms except the target dihedral. The optimal dihedral potential is then V(φ) = EAI(φ) - EFF(φ). Fit the torsional parameters (Vn, n, γ) in the force field to reproduce this V(φ) profile.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Software and Force Field Resources for Atomistic Simulation

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| LAMMPS [6] | MD Engine | General-purpose molecular dynamics simulator | Highly scalable; supports classical, reactive (ReaxFF), and ML potentials. |

| VASP [9] | Ab Initio Code | Electronic structure calculations (DFT) | Generates reference data for force field training and validation. |

| Desmond [10] | MD Engine | High-performance MD for biomolecules and materials | GPU acceleration; integrated with MLFFs and the OPLS force field suite. |

| OPLS5 [10] | Force Field | Classical force field for biomolecules and materials | Incorporates explicit polarizability via Drude oscillators for improved accuracy. |

| MPNICE [10] | Machine Learning FF | MLFF for near-DFT accuracy | Pre-trained models for 89 elements; includes explicit long-range electrostatics. |

| Moment Tensor Potential (MTP) [12] [9] | Machine Learning FF | MLFF for materials science | High data efficiency; often used with active learning for alloy properties. |

| GAFF/GAFF2 [11] | Force Field | General Amber Force Field for organic molecules | Common starting point for organic/polymer systems, often requires reparameterization. |

| LY433771 | LY433771, MF:C22H24N2O4, MW:380.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| UniPR500 | UniPR500, MF:C36H51N3O4, MW:589.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

To assist you in your project, here are practical steps you can take to find the necessary information:

- Consult Specialized Scientific Literature: The most reliable information on force field formulations, their impact on dynamic property prediction, and detailed methodologies is found in academic papers and textbooks. I recommend searching platforms like Google Scholar, PubMed, and arXiv using terms from your title, such as "force field formulations structural dynamic property prediction" and "accurate transport properties".

- Leverage Professional Software Documentation: The documentation and user forums for major molecular dynamics simulation packages (such as GROMACS, AMBER, CHARMM, or OpenMM) are excellent resources. They often contain detailed tutorials, troubleshooting sections, and discussions on force field selection and parameterization that directly address the issues your FAQ would cover.

- Refine Your Search Strategy: For future searches, using highly specific phrases like "GAFF vs. OPLS force field comparison for diffusion coefficients" or "best practices for calculating viscosity with molecular dynamics" will yield more relevant technical results than broader terms.

I hope these suggestions help you find the high-quality technical data needed for your project. If you are able to locate specific force field datasets or parameters, I would be glad to help you format them into clear tables or analyze the information.

Identifying Common Pitfalls in Force Field Transferability Across Systems

For researchers in materials science and drug development, molecular dynamics (MD) simulations are indispensable for predicting material behavior and drug interactions. The accuracy of these simulations hinges on the force field—the mathematical model describing atomic interactions. However, a force field developed for one system often fails when transferred to another, leading to non-physical results and erroneous conclusions. This guide addresses common pitfalls in force field transferability and provides protocols for ensuring reliability, particularly for calculating transport properties.

FAQs and Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ 1: Why does my simulation produce inaccurate transport properties, even with a well-established force field?

Answer: Even force fields with excellent reputations may be parametrized using limited datasets, often focusing on thermodynamic properties (e.g., density and energy) at specific conditions. Their performance can degrade for dynamic properties like viscosity and thermal conductivity, especially when applied to systems or state points outside their original parametrization range.

- Root Cause: The force field may not capture the correct balance of energetic and entropic contributions that govern mass and heat transport. For instance, a force field parametrized only for room-temperature density may fail at predicting high-temperature viscosity.

- Solution: Always consult literature for benchmark studies that specifically validate the force field for the transport properties you intend to calculate. If none exist, plan to validate against any available experimental data for your system [6].

FAQ 2: Can I combine two different force fields to simulate a novel composite or interface?

Answer: This is a high-risk practice. Simply combining force fields developed independently often leads to unphysical interface behavior because the cross-term interactions (e.g., between atom A from force field X and atom B from force field Y) are not properly parametrized.

- Root Cause: Force fields are self-consistent frameworks. The non-bonded parameters (van der Waals, charges) in one force field are tuned to work with its own internal bonded terms and other non-bonded parameters. Mixing them breaks this internal consistency [13].

- Solution: Seek out a unified force field already validated for your combined material system. If unavailable, use specialized cross-term parameters published for that specific combination, or be prepared for a significant parametrization and validation effort [13].

FAQ 3: Why does my simulation crash or behave erratically after I import a new molecule?

Answer: This is often a setup issue, not a force field physics issue. The software may have misassigned atom types, bond orders, or partial charges during the import and perception stage.

- Root Cause: Molecular editing software can sometimes misidentify atom types or bonding environments, especially for non-organic elements or complex coordination compounds. Incorrect atom types lead to missing or wildly inaccurate parameters, causing simulation instability [14].

- Solution: Meticulously check the perceived molecular topology (bonds, angles, dihedrals) and assigned atom types in your simulation software before running the simulation. Tools like SAMSON provide visual feedback on assigned parameters, which should be verified [14].

Troubleshooting Guide: Force Field Transferability

| Symptom | Likely Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Corrective Actions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inaccurate densities | Force field poorly describes cohesive energy or packing. | 1. Calculate equilibrium density at multiple T/P points.2. Compare with experimental data. | Switch to a force field with validated liquid-state properties or re-parametrize non-bonded terms [6]. |

| Transport properties (e.g., viscosity) deviate from experiment | Force field parametrized for structure, not dynamics. | 1. Simulate viscosity/ diffusivity.2. Compare with experimental transport data. | Use a force field benchmarked for dynamics; ensure correct friction/dissipation in your thermostat/barostat [6]. |

| Unphysical bond stretching or system explosion | Missing parameters, incorrect atom typing, or overlapping atoms. | 1. Check simulation log for "missing parameters" errors.2. Visually inspect initial structure for clashes. | Verify all atom types and bonds are correctly assigned. Use a energy minimization and slow heating protocol [14]. |

| Poor reproduction of target material's structure | Force field functional form is too simple to capture key physics. | 1. Compare radial distribution functions with ab initio or experimental data. | Move from a Class I (simple pair potentials) to a Class II (complex, angle-dependent) force field if appropriate for your material [6]. |

Experimental Protocol: Force Field Benchmarking for Transport Properties

This protocol provides a methodology for rigorously evaluating a force field's ability to predict key properties, based on a comprehensive benchmark study of polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) force fields [6].

1. Objective To systematically evaluate the precision and transferability of candidate force fields by comparing MD simulation results against experimental data for thermodynamic and transport properties.

2. Materials and Computational Methods

2.1. Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Protocol |

|---|---|

| Simulation Software (LAMMPS) | The molecular dynamics engine used to perform all simulations [6]. |

| Force Fields (e.g., OPLS-AA, COMPASS) | The interatomic potentials being evaluated and compared [6]. |

| System Builder (Packmol) | Software used to create the initial configuration of polymer chains in a simulation box [6]. |

| Parameterization Tool (Moltemplate) | Helps generate topology and force field parameters for the simulation input [6]. |

2.2. Workflow Overview The following diagram outlines the key stages of the force field benchmarking workflow.

3. Step-by-Step Procedure

Step 1: Force Field Selection Select a range of force fields for evaluation. These should include [6]:

- General-purpose universal force fields (e.g., OPLS-AA, COMPASS, Dreiding).

- Specialized force fields parametrized specifically for your material of interest.

Step 2: System Generation

- Use a tool like Packmol to create the initial system [6].

- Build a simulation box containing multiple polymer chains to avoid finite-size effects.

- The initial configuration is often set at a higher pressure (e.g., 100 atm) to force chains into a liquid-phase configuration [6].

Step 3: System Equilibration

- Gradually reduce the pressure to the target value (e.g., 1 atm) while maintaining temperature (e.g., 300 K).

- Equilibrate under an isothermal-isobaric (NPT) ensemble until the system density converges and the total energy fluctuates around a stable value [6].

- Typical Duration: ~1-10 ns, depending on system size and complexity.

Step 4: Production Simulation

- Using the equilibrated structure from Step 3, run a production simulation under the same NPT ensemble to collect trajectory data for analysis.

- For transport properties, a microcanonical (NVE) ensemble may be required after equilibration [6].

Step 5: Property Calculation & Analysis Calculate the following key properties from the production trajectory and compare them against experimental data:

- Thermodynamic Properties: Density, specific heat capacity, isothermal compressibility.

- Transport Properties: Viscosity (e.g., via Green-Kubo relation), thermal conductivity, diffusion coefficients.

4. Expected Outcomes and Interpretation The benchmark will reveal significant variations in performance between different force fields. Table 1 summarizes hypothetical results based on a PDMS benchmarking study [6].

- Table 1: Example Force Field Benchmarking Results for PDMS Properties (Data inspired by [6])

| Force Field | Type | Density (g/cm³) | Specific Heat (J/g·K) | Viscosity (cP) | Thermal Conductivity (W/m·K) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experiment | - | ~0.97 | ~1.6 | ~100 | ~0.15 |

| OPLS-AA | All-Atom / General | 1.02 | 1.5 | 50 | 0.18 |

| COMPASS | All-Atom / General | 0.96 | 1.7 | 130 | 0.16 |

| Huang-2024 | All-Atom / Specific | 0.97 | 1.6 | 105 | 0.15 |

| UA-Frischknecht | United-Atom / Specific | 0.98 | 1.7 | 90 | 0.14 |

Interpretation:

- The specialized Huang-2024 force field shows the best overall agreement with experiment across both thermodynamic and transport properties.

- The general-purpose OPLS-AA force field shows significant deviations in viscosity, indicating potential limitations for dynamics simulations.

- The choice of force field directly impacts the results, underscoring the need for systematic benchmarking.

The transferability of force fields is a fundamental challenge in atomistic simulations. To ensure reliable results for your research on transport properties, adhere to the following practices:

- Benchmark Systematically: Never assume a force field is accurate for your specific application. Always run controlled benchmark simulations against known experimental data before beginning production runs on novel systems [13] [6].

- Select the Right Tool: Prioritize force fields that have been specifically developed and validated for the class of materials and the specific properties you are studying. Do not rely solely on general-purpose force fields without validation [6].

- Document and Archive: For reproducibility, meticulously document the exact version and source of the force field parameters used in your publications. The community is moving towards archiving potential files with manuscripts to ensure full traceability [13].

- Inspect the Setup: A significant fraction of "force field problems" are actually setup errors. Always verify atom types, charges, and bond assignments in your initial configuration before launching lengthy simulations [14].

Methodological Approaches and Practical Application Guidelines

Selecting Optimal Force Field Combinations for Biomolecular Systems

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the most critical factor when choosing a force field for simulating proteins or other biomolecules? The most critical factor is the specific biomolecular system and property you are investigating. No single force field is universally superior. For simulating folded proteins, additive all-atom force fields like AMBER, CHARMM, and OPLS-AA are standard choices, refined over decades for this purpose [15]. However, for processes involving chemical reactions, bond breaking, or charge transfer, you may need a reactive or polarizable force field [15] [16]. Always consult recent benchmarking studies for systems similar to yours.

My simulations of ligand binding are not agreeing with experimental affinity data. What could be wrong? Inaccuracies can arise from several sources in the force field combination:

- Inconsistent Ligand Parameters: The parameters for the small molecule ligand may have been developed asynchronously or be incompatible with the protein force field [15]. Ensure ligand parameters are derived using a method consistent with the protein force field (e.g., using the same charge model and atom typing rules).

- Lack of Polarization: Standard additive force fields use fixed atomic charges, which cannot account for electronic polarization effects in the binding site, potentially misrepresenting electrostatic interactions [15] [17].

- Inadequate Treatment of Entropy and Solvation: End-point methods like MM/GBSA used to calculate binding affinities contain crude approximations, such as the neglect of conformational entropy and the treatment of water molecules in the binding site [18].

How can I efficiently assign parameters to a novel drug-like molecule or a post-translationally modified amino acid? Traditional manual atom-typing is labor-intensive. Two modern approaches are:

- Automated Parameterization Tools: Software like

SwissParamand theCHARMM General Force Field (CGenFF)program can automatically generate topology and parameters for a wide range of small molecules, providing a solid starting point [19]. - Environment-Specific Parameterization: For greater accuracy, you can derive charges and Lennard-Jones parameters directly from quantum mechanical (QM) calculations of your specific molecule. This approach naturally includes polarization effects and ensures consistency between the protein and ligand parameters [17].

What are the key differences between classical, polarizable, and machine learning force fields? Table 1: Comparison of Major Force Field Types

| Force Field Type | Functional Form | Key Advantages | Key Limitations | Best for... |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classical Additive (e.g., AMBER, CHARMM) [15] | Fixed point charges, harmonic bonds, Lennard-Jones potentials. | Fast, highly optimized, extensive validation for standard biomolecules. | Cannot model chemical reactions; lacks polarization effects. | Routine simulation of proteins, DNA, ligand binding (with FEP/MM-PBSA). |

| Polarizable (e.g., Drude) [15] | Inducible dipoles or fluctuating charges. | More accurate electrostatics, responds to changing environments. | 2-5x more computationally expensive than additive FFs; parameterization is complex. | Systems where electronic polarization is critical (e.g., membranes, ion channels). |

| Machine Learning (ML) [15] [20] | Neural networks trained on QM data. | QM-level accuracy; can model complex potential energy surfaces. | Computationally intensive for training; requires large QM datasets; risk of instability in long MD [20]. | High-accuracy studies of reaction mechanisms and properties where QM is too slow. |

Are machine learning force fields ready to replace classical force fields for biomolecular simulations? Not yet for routine use. While Universal MLFFs (UMLFFs) promise QM-level accuracy across the periodic table, a significant "reality gap" exists. They are often trained on DFT data and can fail when confronted with the complexity of experimental systems, sometimes leading to unstable simulations [20]. Classical force fields, despite their approximations, are more robust for large-scale biomolecular dynamics. MLFFs are currently best used as a powerful supplement for specific, high-accuracy applications [15].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Inaccurate Prediction of Bulk Material Properties (e.g., Density, Elastic Modulus)

This is common when simulating non-biological polymers or complex materials like polyamide membranes [19].

Table 2: Force Field Performance for Polyamide Membrane Properties [19]

| Force Field | Dry Density | Hydrated Density | Young's Modulus | Water Permeability | Overall Recommendation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCFF | Good | Good (with PCFF water) | Good | Accurate prediction | Recommended |

| CVFF | Accurate | Accurate (with TIP3P) | Accurate | Accurate prediction | Recommended |

| SwissParam | Accurate | Accurate (with TIP3P) | Accurate | Accurate prediction | Recommended |

| CGenFF | Accurate | Less Accurate | Accurate | Less Accurate | Good for mechanical properties |

| GAFF | Less Accurate | Less Accurate | Less Accurate | Less Accurate | Not recommended for this system |

| DREIDING | Less Accurate | Less Accurate | Less Accurate | Less Accurate | Not recommended |

Diagnosis Steps:

- Validate System Composition: Ensure the chemical composition (e.g., O/N ratio for polyamides) of your simulated system matches that of the experimental material you are trying to replicate [19].

- Benchmark Multiple FFs: As shown in Table 2, force field performance is system-specific. Test multiple force fields (e.g., PCFF, CVFF, SwissParam) known to be developed for polymers or organic systems [19].

- Check Water Model Compatibility: The choice of water model (TIP3P, TIP4P, etc.) can significantly impact the predicted properties of hydrated systems. Use the water model recommended for or consistent with your chosen force field [19].

Solution: Select a force field that has been benchmarked against experimental data for your specific material. For polyamide membranes, CVFF and SwissParam delivered accurate predictions for both structural and functional properties [19].

Problem: Unstable Molecular Dynamics Simulations or Unphysical Results

Simulations crash, atoms fly apart, or the structure denatures unexpectedly.

Diagnosis Steps:

- Check Ligand and Cofactor Parameters: This is the most common culprit. Incorrectly assigned atom types, charges, or bonded terms for non-standard residues will cause instabilities.

- Review Protonation States: Ensure all residues (especially His, Asp, Glu) and ligand functional groups are in the correct protonation state for your simulated pH.

- Inspect for Atom clashes: Before dynamics, always perform thorough energy minimization to relieve any bad contacts in the initial structure.

- Consider MLFF Limitations: If using a Machine Learning Force Field, be aware that instability is a known issue. One study found failure rates exceeding 85% for some UMLFFs on complex mineral structures, and stability did not always correlate with low error metrics [20].

Solution:

Follow a rigorous parameterization protocol for non-standard molecules. Use tools like GAFF or CGenFF with manual validation. For MLFFs, start with well-defined systems that are well-represented in the model's training data and always validate against a short, classical MD simulation [17] [20].

Problem: Poor Correlation in Relative Binding Affinity Calculations

Your free energy calculations (e.g., FEP, MM/GBSA) fail to rank a congeneric series of ligands correctly.

Diagnosis Steps:

- Identify the Source of Error: Determine if the error stems from the force field itself or the sampling methodology.

- Test the 1A- vs 3A-MM/GBSA Approach: The standard "one-average" (1A) approach, which uses only the complex trajectory, can be problematic. It ignores the conformational change of the receptor and ligand upon binding. Try the more rigorous "three-average" (3A) approach, which uses separate simulations for the complex, receptor, and ligand, though it is more computationally expensive and can have higher uncertainty [18].

- Verify Entropy Treatment: The entropy term in MM/GBSA (often calculated via normal-mode analysis) is a major approximation and can be a significant source of error [18].

Solution:

- For MM/GBSA, ensure sufficient sampling of the bound and unbound states. Consider using the "three-average" (3A) approach if feasible and be cautious of over-interpreting absolute binding energies. Focus on relative trends [18].

- For higher accuracy, use alchemical perturbation methods (FEP) with a modern, well-validated force field. The accuracy of FEP is inherently limited by the force field's accuracy [15].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function | Example Tools / Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Automated Force Field Parameterization | Generates topology and parameters for small molecules and ligands, ensuring compatibility with a specific biomolecular force field. | SwissParam [19], CHARMM General Force Field (CGenFF) [19], Antechamber (for GAFF). |

| Quantum Chemistry Software | Provides reference data for deriving environment-specific atomic charges and Lennard-Jones parameters, improving accuracy for novel molecules [17]. | Q-Chem [16], Gaussian [16], CP2K [16]. |

| Linear-Scaling DFT | Enables quantum mechanical calculations on large systems (thousands of atoms), making direct parameterization of protein-ligand complexes feasible [17]. | TeraChem [17] |

| Binding Affinity Calculation | End-point methods to estimate binding free energies, offering a balance between speed and theoretical rigor compared to docking scores [18]. | MM/GBSA, MM/PBSA (as implemented in Flare [21] or AMBER). |

| Force Field Benchmarking Datasets | Provides experimental data for validating and comparing the performance of different force fields on real-world systems. | UniFFBench [20] (for materials), community benchmarks for proteins/nucleic acids. |

| Esterastin | Esterastin, MF:C28H46N2O6, MW:506.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Handelin | Handelin, CAS:62687-22-3, MF:C32H40O8, MW:552.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Workflow for Force Field Selection

This diagram outlines a logical workflow for selecting and validating a force field, based on the system type and research goal.

Establishing Robust Equilibration Protocols for Reliable Dynamics

Welcome to the Technical Support Center

This resource provides troubleshooting guides and frequently asked questions (FAQs) to support researchers in establishing robust equilibration protocols for molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, with a specific focus on obtaining reliable transport properties through appropriate force field selection.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: Why is my equilibration protocol failing to reproduce experimental transport properties, even with extended simulation time? A: The issue likely stems from the force field itself, not just the simulation time. Empirical force fields are often parameterized for specific properties or compositional ranges and may not be transferable. For accurate dynamics in CaO-Al₂O₃-SiO₂ melts, benchmarking has shown that Bouhadja's force field outperforms others like Matsui's and Guillot's in reproducing experimental activation energies and transport trends [2].

Q: How can I prevent contamination that leads to high background or non-specific binding in my assay? A: ELISA kits and other sensitive assays are vulnerable to contamination from concentrated analyte sources. Key precautions include [22]:

- Workspace Separation: Do not perform assays in areas where concentrated cell culture media or sera are used.

- Equipment Hygiene: Clean all work surfaces and pipettes before use. Use pipette tips with aerosol barrier filters.

- Sample Handling: Avoid talking or breathing over uncovered microtiter plates. Consider using a laminar flow hood. Do not return unused substrate to the stock bottle.

Q: What is the best curve-fitting method for my immunoassay data? A: Linear regression is generally not recommended for immunoassay data, including HCP ELISAs, as the dose response is rarely perfectly linear. Forcing a linear fit can introduce inaccuracies, especially at the curve extremes. We strongly recommend using Point-to-Point, Cubic Spline, or 4-Parameter curve-fitting routines for the most accurate results [22].

Q: My node in a Graphviz diagram has a fillcolor defined, but it is not appearing. What is wrong?

A: For a fillcolor to be visible, the style=filled attribute must also be set for the node [23]. Without this, the fill color will not be applied.

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: High Background (Non-Specific Binding) in ELISA

- Problem: Elevated background absorbances in the zero standard.

- Investigation & Solution:

- Check Washing Technique: Incomplete washing can cause carryover of unbound reagent. Review and follow the recommended washing procedure in the kit insert without over-washing [22].

- Investigate Contamination: Contamination of kit reagents or substrate by concentrated analyte sources can cause high background. Refer to the "Avoiding Contamination" guidelines above [22].

- Inspect Substrate: For alkaline phosphatase-based ELISAs using PNPP, substrate contamination can be a cause. If contaminated, order a replacement [22].

Issue 2: Inaccurate Sample Dilution and Recovery

- Problem: Under-recovery of the true analyte level upon sample dilution.

- Investigation & Solution:

- Validate Diluent: Always use the assay-specific diluent recommended by the kit manufacturer, as its formulation matches the kit standards and minimizes dilutional artifacts [22].

- Perform Control Experiments:

Issue 3: Force Field Selection for Transport Properties

- Problem: Self-diffusion coefficients and electrical conductivity from simulations do not match experimental data.

- Investigation & Solution:

- Benchmark Force Fields: Systematically benchmark the performance of different force fields against key properties. The table below summarizes a benchmark study for CaO-Al₂O₃-SiO₂ melts [2].

- Select an Appropriate Force Field: For dynamics and transport properties, Bouhadja's force field has been identified as the most physically accurate and reliable choice, showing better agreement with experimental activation energies and ab initio MD predictions for Al-O and Ca-O bonding [2].

| Force Field | Original Parameterization For | Performance on Structural Properties (Density, Bond Lengths) | Performance on Transport Properties (Diffusion, Conductivity) | Transferability Beyond Original Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bouhadja et al. | High-temperature liquid phase | Good agreement with AIMD for Al-O and Ca-O bonding | Best agreement with experimental activation energies and trends | Robust |

| Matsui et al. | CMAS crystals | Accurate for densities and Si-O tetrahedral environments | Less accurate for dynamics | Limited |

| Guillot & Sator | High-temperature liquid phase | Accurate for densities and Si-O tetrahedral environments | Less accurate for dynamics | Limited |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Benchmarking a Force Field for Molten Oxides

Objective: To evaluate the accuracy and transferability of an empirical force field for predicting the structural and transport properties of CaO-Al₂O₃-SiO₂ melts.

Methodology [2]:

- System Setup: Create simulation cells for ten different melt compositions across a temperature range of 1400-1600 °C.

- Simulation Run: Perform classical MD simulations using the force fields under investigation (e.g., Bouhadja, Matsui, Guillot).

- Data Collection:

- Structural Properties: Calculate density, distribution of bond lengths, and coordination numbers.

- Transport Properties: Calculate self-diffusion coefficients and electrical conductivity using the Einstein relation, accounting for cross-correlations between ions for accurate conductivity prediction.

- Validation: Compare MD predictions against:

- Available experimental data.

- CALPHAD-based density models.

- Ab initio MD (AIMD) simulations for structural properties.

Protocol 2: Validating a Custom Sample Diluent for Impurity Assays

Objective: To ensure a custom diluent provides accurate results without matrix interference in sensitive ELISAs.

Methodology [22]:

- Background Check: Assay the proposed diluent alone as an unknown sample. The measured absorbance should not be significantly above or below the absorbance of the kit's zero standard.

- Spike-and-Recovery:

- Spike a known amount of the pure analyte into the proposed diluent at several concentrations across the assay's analytical range.

- Calculate the percentage recovery of the known analyte.

- Acceptance Criteria: The diluent is deemed acceptable if recovery falls within 95-105%. The diluent should be a neutral pH buffer containing a carrier protein (e.g., BSA) to prevent adsorptive losses and should not contain sodium azide or significant detergent [22].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Assay-Specific Diluent | A buffer matrix-matched to the kit's standards; used to dilute samples to minimize matrix effects and dilutional artifacts in immunoassays [22]. |

| Aerosol Barrier Pipette Tips | Disposable tips with an internal filter; prevent aerosol contamination from reaching and contaminating the pipette shaft when handling concentrated analyte samples [22]. |

| Carrier Protein (e.g., BSA) | A protein added to dilution buffers; blocks non-specific binding sites on tubes and plates, preventing adsorptive losses of the analyte which is critical at low (ng/mL) concentrations [22]. |

| Bouhadja's Force Field | An empirical Born-Mayer-Huggins potential; identified as the most reliable for simulating transport phenomena (self-diffusion, electrical conductivity) in CaO-Al₂O₃-SiO₂ melts [2]. |

| Lorotomidate | Lorotomidate, CAS:2093287-60-4, MF:C14H15FN2O2, MW:262.28 g/mol |

| Lturm 36 | Lturm 36, MF:C22H18N2O3, MW:358.4 g/mol |

Workflow Visualizations

Force Field Benchmarking Workflow

Assay Troubleshooting Logic

System Size and Morphological Considerations for Property Convergence

Troubleshooting Guides

Troubleshooting Guide 1: Inaccurate Bulk Property Predictions

Issue: Simulated bulk properties (e.g., density, dielectric constant) do not converge with experimental values, even when using a force field parameterized to match them.

Diagnosis & Solution:

| Probable Cause | Diagnostic Checks | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Insufficient System Size | - Calculate property vs. simulation box size.- Check for significant fluctuations in property time-series. | Increase system size until the target property converges to a stable value [24]. |

| Inadequate Sampling | - Run multiple independent simulations.- Check if statistical error overlaps with deviation from experiment. | Extend simulation time and employ enhanced sampling techniques for better phase-space coverage [24]. |

| High Morphological Complexity | - Analyze pore-size distribution and tortuosity.- Compute Minkowski functionals. | Use larger, more representative samples that capture structural heterogeneities [25]. |

| Force Field Limitations | - Compare results across multiple force fields (e.g., TIP3P, SPC, SPC/ε).- Perform information-theoretic analysis on clusters. | Select a force field with superior electronic structure representation, such as SPC/ε, which shows better entropy-information balance [24]. |

Troubleshooting Guide 2: Poor Transferability from Clusters to Bulk

Issue: Properties calculated from small molecular clusters do not scale consistently to bulk phase properties.

Diagnosis & Solution:

| Probable Cause | Diagnostic Checks | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Missing Critical Cluster Size | - Analyze target property as a function of cluster size (e.g., 1M, 3M, 5M...11M). | Include larger clusters (e.g., 9M, 11M) in the analysis to observe convergence toward bulk-like behavior [24]. |

| Improper Force Field for Intended Scale | - Evaluate information-theoretic descriptors (Shannon entropy, Fisher information) across cluster sizes. | Choose a force field like SPC/ε, which demonstrates optimal scaling behavior and superior electronic structure representation in clusters [24]. |

| Over-reliance on Single Geometry | - Test the force field on a diverse set of cluster configurations. | Ensure sampling covers a representative range of cluster geometries and hydrogen-bonding networks [24]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the minimum system size required for my transport property simulations? There is no universal minimum size. System size must be determined through a convergence test where the target property (e.g., permeability, conductivity) is calculated for progressively larger systems until the value stabilizes within an acceptable statistical error [25]. For molecular clusters, studies often analyze a series (e.g., 1, 3, 5, 7, 9, 11 molecules) to capture scaling behavior [24].

FAQ 2: How does morphological complexity affect my simulation results? Complex morphologies, characterized by features like low porosity, high tortuosity, and geometric heterogeneities, can significantly impact transport properties. Two samples with identical porosity can have vastly different permeability and conductivity due to differences in pore-shape and connectivity. This is why using 3D structural data is critical for accurate predictions [25].

FAQ 3: My force field was parameterized for bulk water, but it performs poorly in my confined system. Why? Standard force fields parameterized for bulk properties may not capture the altered physics in nanoconfined environments. The SPC/ε model, which includes an empirical self-polarization correction, has shown improved performance in such heterogeneous environments compared to models like TIP3P [24].

FAQ 4: Are there computational tools to help select the most appropriate force field? Yes, beyond comparing standard bulk properties, information-theoretic analysis provides a powerful tool. By calculating measures like Shannon entropy and Fisher–Shannon complexity on molecular clusters, you can evaluate a force field's ability to represent electronic structure and predict its transferability to bulk phases [24].

FAQ 5: Where can I find reliable 3D structural data for complex porous media? Public repositories like the Digital Rocks Portal (DRP) host peer-reviewed, diverse samples from various materials (rocks, catalysts, soils, etc.). Large datasets like DRP-372 provide standardized 3D geometries and simulated transport properties for method validation and development [25].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Table 1: Information-Theoretic Analysis of Water Model Clusters

This table summarizes the methodology for evaluating force field performance using water clusters of increasing size [24].

| Step | Procedure | Key Parameters | Output/Metric |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. System Preparation | Generate cluster geometries containing 1, 3, 5, 7, 9, and 11 water molecules. | Cluster sizes (1M to 11M), Force fields (TIP3P, SPC, SPC/ε) | 3D molecular cluster configurations. |

| 2. Electronic Structure Calculation | Compute electronic probability densities for each cluster using density functional theory. | DFT method, Basis set | Electronic densities in position and momentum space. |

| 3. Descriptor Calculation | Calculate five fundamental information-theoretic descriptors from the electronic densities. | Shannon entropy, Fisher information, Disequilibrium, LMC complexity, Fisher-Shannon complexity | Quantitative measures of delocalization, localization, and structural sophistication. |

| 4. Statistical Validation | Perform Shapiro-Wilk normality tests and Student's t-tests on the calculated descriptors. | p-value, Statistical significance | Robust discrimination between the performance of different force fields. |

| 5. Correlation with Bulk Properties | Compare the scaling behavior of descriptors with known experimental bulk properties (density, dielectric constant). | Convergence behavior, Scaling patterns | Establishes transferability from clusters to bulk phase. |

Table 2: Key Water Model Parameters for Simulation

Geometric and interaction parameters for three widely used rigid water models [24].

| Water Model | rOH (Å) | θ H-O-H (°) | qH (e) | qO (e) | σOO (Å) | εOO/kB (K) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TIP3P | 0.9572 | 104.52 | +0.417 | -0.834 | 3.1506 | 76.54 |

| SPC | 1.0 | 109.45 | +0.410 | -0.820 | 3.1660 | 78.20 |

| SPC/ε | 1.0 | 109.45 | +0.445 | -0.890 | 3.1785 | 84.90 |

Workflow Visualization

Workflow for Force Field Evaluation via System Size Convergence

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Essential Materials for Force Field Evaluation and Transport Property Simulation

| Item/Resource | Function/Benefit |

|---|---|

| Rigid Water Models (TIP3P, SPC, SPC/ε) | Computationally efficient potentials for simulating aqueous systems; SPC/ε is optimized for accurate dielectric constant [24]. |

| Digital Rocks Portal (DRP) Datasets | Provides peer-reviewed, diverse 3D geometric data of porous media for realistic simulation benchmarks [25]. |

| Lattice-Boltzmann Simulation Codes | Efficient numerical method for simulating fluid flow and transport in complex 3D geometries [25]. |

| Information-Theoretic Analysis Software | Calculates descriptors (Shannon Entropy, Fisher Information) to quantify force field performance beyond bulk properties [24]. |

| Molecular Dynamics Software (e.g., GROMACS, NAMD) | Software suites to perform the dynamics simulations using the selected force fields [24]. |

| Enactin Ia | Enactin Ia, MF:C20H38N2O6, MW:402.5 g/mol |

| Cdk7-IN-30 | Cdk7-IN-30, MF:C21H28ClN5O3S, MW:466.0 g/mol |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

General Principles and Applicability

What types of problems are suitable for alchemical free energy calculations?

Alchemical free energy calculations are particularly useful for predicting free energy differences associated with molecular transfer processes. Common applications include [26]:

- Relative binding free energies: Estimating differences in binding affinity between related small molecules to a biomolecular target.

- Absolute binding free energies: Computing the binding affinity of a single ligand to its receptor.

- Solvation free energies: Determining the free energy of transferring a molecule from gas phase to solvent.

- Partition coefficients: Predicting how molecules distribute between different environments, such as octanol-water partition coefficients (log P).

- Protein mutations: Assessing the impact of side-chain mutations on binding affinity or protein stability.

When should I consider alternative methods to alchemical free energy calculations?

Alchemical methods may be unsuitable for [26]:

- Systems with multiple distinct binding modes that aren't adequately sampled during simulation time.

- Covalent inhibitors where special protocols are required.

- Transformations involving large structural changes that introduce significant sampling challenges.

- When highly accurate force field parameters are unavailable for the chemical species of interest.

Force Field Selection and System Preparation

How does force field selection impact the accuracy of transport property predictions?

Force field selection critically determines the accuracy of computed properties in alchemical calculations. Traditional force fields parameterized solely on pure liquid properties (densities and enthalpies of vaporization) often show systematic errors when predicting mixture properties or phase behavior [27]. For accurate transport properties, consider:

- Force fields trained on mixture data: These better capture A-B interactions crucial for solute-solvent behavior [27].

- Polarizable force fields: Models like AMOEBA or ByteFF-Pol can better represent electronic response to different environments [28].

- Validation against experimental data: Always validate your chosen force field against available experimental data for similar systems.

What are the key considerations for preparing my system for alchemical simulations?

Proper system preparation is essential for robust results [26] [29]:

- Initial structures: Generate physically realistic starting configurations, potentially using docking for ligand-receptor systems.

- Solvation: Ensure adequate solvation with appropriate water models and ion concentrations to neutralize system charge.

- Equilibration: Perform thorough equilibration of both solute and solvent degrees of freedom before production simulations.

- Parameterization: Use consistent parameter sources for all molecules, with special attention to partial charges and torsion parameters.

Execution and Analysis

What are the best practices for running and analyzing alchemical free energy calculations?

Follow these guidelines to ensure reliable results [26] [29]:

- Sampling: Run sufficiently long simulations to achieve adequate sampling of all relevant conformational states.

- State spacing: Choose intermediate λ values carefully to ensure sufficient overlap between adjacent states.

- Analysis method: Use statistically optimal estimators like MBAR or BAR rather than simple methods like TI or FEP.

- Error analysis: Always report statistical uncertainties using methods like block analysis or bootstrap resampling.

- Convergence assessment: Monitor convergence through multiple measures, including forward/reverse comparisons and decorrelation times.

How can I troubleshoot a free energy calculation that shows poor convergence?

Common issues and solutions include [26]:

- Insufficient sampling: Increase simulation time at each λ state, particularly where energy variances are high.

- Poor λ spacing: Add intermediate states in regions where the free energy change is rapid.

- Inadequate equilibration: Extend equilibration time, particularly for slow degrees of freedom.

- Force field issues: Validate your force field on simpler systems with known experimental values.

Troubleshooting Common Issues

Sampling and Convergence Problems

Table 1: Troubleshooting Sampling and Convergence Issues

| Problem Symptom | Potential Causes | Diagnostic Steps | Solutions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Large statistical uncertainties | Insufficient sampling, poor overlap between states | Check energy variance across λ states; Monitor autocorrelation times | Increase simulation length; Add intermediate λ states |

| Hysteresis between forward and reverse transformations | Slow degrees of freedom not adequately sampled | Compare order parameters in different directions; Identify slow conformational changes | Enhance sampling of slow modes; Use Hamiltonian replica exchange |

| Discontinuous free energy changes between λ windows | Too few intermediate states | Calculate overlap statistics between adjacent states | Insert additional λ states in problematic regions |

| Failure to converge with increased simulation time | Insufficient phase space exploration | Check for trapped conformational states; Monitor multiple replicas | Implement enhanced sampling techniques; Extend equilibration |

Force Field and Parameterization Issues

Table 2: Troubleshooting Force Field and Parameterization Problems

| Problem Symptom | Potential Causes | Diagnostic Steps | Solutions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Systematic deviation from experimental trends | Poor force field parameters | Validate on known experimental data for similar compounds | Switch to better-validated force fields; Retrain parameters |

| Unphysical molecular configurations | Incorrect torsion parameters or van der Waals radii | Visualize simulation trajectories; Check for atomic clashes | Verify parameter assignment; Use multiple parameter sources |

| Poor agreement with specific mixture properties | Inadequate A-B interaction parameters | Compare simulated vs. experimental mixture properties | Use force fields trained on mixture data [27] |

| Excessive polarization effects | Missing polarization in fixed-charge force fields | Compare to polarizable force field results | Implement explicit polarization models [28] |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Standard Protocol for Relative Binding Free Energy Calculations

The following diagram illustrates a complete workflow for relative binding free energy calculations:

Alchemical Free Energy Calculation Workflow

Detailed Protocol Steps:

System Preparation

- Obtain initial coordinates for protein and ligands

- Parameterize ligands using consistent force field rules

- Solvate systems in appropriate water model with ion concentrations to neutralize charge

- Generate both complex (protein-ligand) and solvent-only systems

Equilibration Protocol

- Energy minimization (steepest descent, then conjugate gradient)

- Gradual heating to target temperature (e.g., 100 ps from 0K to 300K)

- NPT equilibration to achieve correct density (typically 1-5 ns)

- Monitor equilibration through stability of potential energy, density, and RMSD

λ Pathway Setup

- Define 12-24 intermediate states between end states

- Use closer spacing where non-linearities are expected (appearance/disappearance of atoms)

- For relative transformations, consider using a common reference state

Production Simulations

- Run simulations at each λ state (typically 1-10 ns per window)

- Use Hamiltonian replica exchange if available to enhance sampling

- Save coordinates and energies at appropriate intervals for analysis

Analysis and Validation

- Compute free energy difference using MBAR or BAR

- Estimate statistical uncertainties using block averaging or bootstrap methods

- Validate through consistency checks (forward vs. reverse transformations)

- Compare with experimental data when available

Force Field Validation Protocol

Table 3: Force Field Validation Metrics for Transport Properties

| Validation Property | Calculation Method | Target Accuracy | Physical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Liquid density | NPT simulation | < 2% error | Molecular volume and repulsive interactions |

| Enthalpy of vaporization | Liquid and gas phase simulations | < 3% error | Cohesive energy density |

| Enthalpy of mixing | Binary mixture simulations | < 10% error | A-B cross-interactions [27] |

| Diffusion coefficients | Mean squared displacement | < 20% error | Molecular mobility and friction |

| Solvation free energy | Alchemical transformation | < 1 kcal/mol error | Solute-solvent interactions |

| Dielectric constant | Dipole fluctuation analysis | < 15% error | Electronic polarization response |

The Scientist's Toolkit

Essential Software and Analysis Tools

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for Alchemical Calculations

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Simulation Engines | OpenMM, GROMACS, NAMD, AMBER | Molecular dynamics propagation | OpenMM offers GPU acceleration; GROMACS is widely used |

| Setup Tools | tleap, CHARMM-GUI, PACKMOL | System preparation and solvation | CHARMM-GUI provides web-based setup |

| Force Fields | CHARMM, AMBER, OPLS, GAFF, OpenFF | Molecular mechanics parameters | OpenFF provides regularly updated parameters |

| Analysis Packages | pymbar, alchemical-analysis, MDTraj | Free energy estimation and trajectory analysis | pymbar implements MBAR statistical method |

| Visualization | VMD, PyMol, Chimera | Trajectory inspection and rendering | Essential for debugging system setup |

| Enhanced Sampling | PLUMED, WESTPA | Advanced sampling algorithms | Implements metadynamics, replica exchange |

| Nsd-IN-4 | Nsd-IN-4, MF:C17H12ClFN2O2, MW:330.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| c-Myc inhibitor 15 | c-Myc inhibitor 15, MF:C27H31N5O2, MW:457.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Force Field Selection Guide

The following diagram illustrates the decision process for selecting appropriate force fields:

Force Field Selection Decision Tree

Implementing QM/MM and Polarizable Force Fields for Enhanced Accuracy

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the main types of polarizable force fields available for QM/MM simulations, and when should I use each?

Polarizable force fields significantly enhance simulation accuracy by allowing the MM region to respond to the electronic structure of the QM region. The three primary schemes are [30]:

- Shell Model: Best for simulating ionic materials. It splits polarizable MM centers into a core and a valence shell to model polarizable electrons.

- Charge-on-Spring/Drude Oscillator Model: Used with GROMOS (COS) or CHARMM (Drude) force fields. A massless point charge is attached to a polarizable MM atom.

- Polarised-Boundary RC(D) Model: Adjusts MM point charges on QM/MM boundary atoms via charge equilibration methods. It should only be used with RC or RCD schemes.

Q2: I am setting up a QM/MM calculation with the DRF method. How do I correctly define the regions?

For a DRF (Discrete Reaction Field) calculation, you must correctly partition your system. Using AMSinput software as an example [31]:

- Use the

Regionspanel to define at least two regions (e.g.,SoluteandSolvent). - Select your QM molecule and assign it as the

Soluteregion. - Select all other atoms (e.g., solvent molecules) and assign them as the

Solventregion. - In the

DIM/QMpanel, select 'DRF' as the method. - Check the 'QM part' for the

Soluteregion and the 'DIM part' for theSolventregion. The atomic charges for the DRF region can be computed using methods like MDC-Q charges [31].

Q3: During a geometry optimization with a reactive force field like ReaxFF, I encounter convergence issues. What could be the cause?

Convergence issues in ReaxFF geometry optimizations are often caused by discontinuities in the energy derivative. This is frequently related to the BondOrderCutoff parameter [32]. When the bond order of an atom pair crosses this cutoff value between optimization steps, the forces can change abruptly, breaking convergence. To improve stability, you can [32]:

- Decrease the

BondOrderCutoffvalue (e.g., below the default of 0.001). - Use the 2013 formula for torsion angles by setting

Engine ReaxFF%Torsionsto2013. - Enable bond order tapering with

Engine ReaxFF%TaperBO.

Q4: My pdb2gmx run fails with "Residue 'XXX' not found in residue topology database." How can I fix this?

This common error means the force field you selected does not contain a definition for the residue 'XXX' in its database. Your options are [33]:

- Check for naming issues: The residue name in your coordinate file might not match the name in the force field's database. Rename the residue in your file if necessary.

- Use a different force field: A different force field might have parameters for your molecule.

- Find or create a topology: You cannot use

pdb2gmxfor arbitrary molecules without a database entry. You must find a pre-existing topology file (.itp) for your molecule or parameterize it yourself, which is an advanced task [33].

Q5: How can I ensure my molecular dynamics simulation results are statistically significant?

Accurate error estimation is crucial for reliable results. A robust approach involves running multiple independent simulations [34]:

- Run many (e.g., k=100) independent MD simulations from different initial conditions.

- For each simulation, calculate the average of your quantity of interest (e.g.,

bar{x}_i), discarding an initial portion for equilibration. - The final estimate is the mean of these averages:

frac{1}{k} sum_{i=1}^{k} bar{x}_i. - To account for correlations within a single trajectory, use block-averaging for each simulation to get an error estimate

delta bar{x}_ifor each. - The overall error can then be calculated as

frac{1}{k} sqrt{sum_{i=1}^k (delta bar{x}_i)^2}[34].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Force Field Selection for Oxidic Melt Transport Properties

Problem: Inaccurate prediction of dynamic properties like self-diffusion coefficients and electrical conductivity in CaO–Al₂O₃–SiO₂ melts.

Explanation: Not all force fields are created equal. Some are parameterized for crystalline or glassy states at room temperature and perform poorly for high-temperature melts and transport properties [2].

Solution: A systematic benchmark of three common force fields reveals key differences in performance [2]:

| Force Field | Original Parameterization For | Best for Structural Properties (Density, Bond Lengths) | Best for Dynamic Properties (Diffusion, Conductivity) | Transferability Beyond Original Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Matsui | Crystals (CMAS system) | Good | Poor | Limited |

| Guillot | High-temperature liquid phase | Good | Moderate | Moderate |

| Bouhadja | Molten state | Good for Al–O, Ca–O bonding | Best | Best |

Recommendation: For simulating transport phenomena in molten oxides, Bouhadja's force field is identified as the most physically accurate and reliable choice [2].

Issue 2: Polarizable QM/MM Setup and Convergence

Problem: QM/MM simulation with a polarizable force field fails to converge or produces unphysical results.

Explanation: Convergence in polarizable QM/MM requires self-consistency between the QM electron density and the polarized MM region. Incorrect parameters can prevent this or lead to a "polarization catastrophe" [30] [32].

Solution: Follow these steps for the Drude/COS model in ChemShell [30]:

- Verify Parameters: Ensure the polarizability (

a_pol) and massless charge parameters are correct. For the Drude model, the charge isq = sqrt(a_pol * k_d), wherek_dis the harmonic spring constant from the CHARMM force field. - Check Cut-offs: For the COS model, set

polcos_rcutl,polcos_rcutf, andpolcos_epsrfto match the accompanying GROMOS96 MM calculation. For the Drude model, set cut-off parameters in the CHARMM parameter file to a very large value to avoid truncating long-range interactions. - Adjust Convergence Controls: If the calculation does not converge, tighten the tolerance criteria and increase the maximum cycles.

polcos_toler_energy: Convergence criteria for QM energy change.polcos_maxdx: Maximum allowed change in the position of the massless charge.polcos_maxcycle: Maximum number of outer (QM/MM) iterations.polcos_inmaxcycle: Maximum number of inner (MM polarization) iterations [30].

- Avoid Catastrophe: For electronegativity equalization method (EEM) parameters, ensure the

etaandgammaparameters satisfyeta > 7.2*gammato avoid a polarization catastrophe at short interatomic distances [32].

Issue 3: System Equilibration for Complex Polymers

Problem: Achieving a well-equilibrated structure for complex ion exchange polymers (e.g., Nafion) is computationally expensive and time-consuming using conventional methods.

Explanation: Traditional annealing methods, which cycle temperature over a wide range (e.g., 300 K to 1000 K) over many cycles, are computationally intensive and can be inefficient for large systems [35].

Solution: A novel, robust equilibration algorithm for polymers like PFSA (Nafion) has been demonstrated to be significantly faster [35]:

- Efficiency Gain: The proposed method is ~200% more efficient than conventional annealing and ~600% more efficient than a "lean" NVT/NPT method.

- Morphological Insight: For Nafion, using 14 or 16 polymer chains in the model significantly reduces variation and error in calculated diffusion coefficients of water and hydronium ions, even at high hydration levels. This provides a morphologically and computationally robust threshold for accurate property prediction [35].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Materials