Accurate Error Estimation and Statistical Analysis of Diffusion Coefficients: A Guide for Biomedical Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the accurate estimation and statistical analysis of diffusion coefficients.

Accurate Error Estimation and Statistical Analysis of Diffusion Coefficients: A Guide for Biomedical Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the accurate estimation and statistical analysis of diffusion coefficients. It covers foundational principles, from Fickian diffusion to the Einstein relation, and explores diverse methodological approaches, including molecular dynamics simulations, Taylor dispersion, and ATR-FTIR. A strong emphasis is placed on troubleshooting common errors in statistical analysis and data fitting, such as those arising from MSD analysis and model misspecification. Finally, the article presents a framework for the validation and comparative analysis of diffusion data across different experimental and computational techniques, highlighting applications in critical areas like drug delivery and medical diagnostics. The goal is to empower scientists to produce more reliable and reproducible diffusion data for biomedical applications.

Core Principles: Understanding Diffusion and the Critical Role of Error

Your Questions Answered

This guide addresses common challenges researchers face when determining diffusion coefficients, with a special focus on statistical best practices for robust error estimation.

FAQ 1: What is the most reliable method to calculate a diffusion coefficient from a molecular dynamics (MD) simulation?

The most common and recommended method is the Mean Squared Displacement (MSD) approach [1] [2]. For a three-dimensional, isotropic system, the diffusion coefficient D is calculated from the slope of the MSD plot at long time intervals using the Einstein relation:

$$MSD(t) = \langle [\mathbf{r}(t) - \mathbf{r}(0)]^2 \rangle = 6Dt$$

Therefore,

$$D = \frac{1}{6} \times \text{slope}(MSD)$$ [1] [2]

- Best Practice: Ensure your simulation is long enough that the MSD plot is linear in the diffusive regime. At short times, motion may be ballistic (MSD ~ t²), and other sub-diffusive regimes may exist before normal diffusion (MSD ~ t) is observed [2].

- Alternative Method: The Velocity Autocorrelation Function (VACF) is another valid technique [1] [2]: $$D = \frac{1}{3} \int_{0}^{\infty} \langle \mathbf{v}(0) \cdot \mathbf{v}(t) \rangle dt$$

FAQ 2: Why is my MSD plot not a perfect straight line, and how does this affect error estimation?

An MSD plot is never a perfect straight line because it is derived from finite simulation data with inherent statistical noise [3]. Using simple Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regression on MSD data is problematic because the data points are serially correlated and heteroscedastic (having unequal variances) [3]. This leads to:

- Statistical Inefficiency: The estimate of D has a larger-than-necessary statistical uncertainty [3].

- Underestimated Uncertainty: The standard error calculated by OLS significantly underestimates the true uncertainty in D [3], which can cause overconfidence in the result.

FAQ 3: What advanced statistical methods provide better error estimates for diffusion coefficients?

To overcome the limitations of OLS, use regression methods that account for the true correlation structure of the MSD data.

- Generalized Least-Squares (GLS) and Bayesian Regression: These methods use the full covariance matrix of the MSD, which describes the correlations between data points and their changing variances [3]. This leads to estimates of D that are statistically more efficient (have smaller uncertainty) and provide a more accurate estimate of the statistical error [3].

- Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE): This is another powerful optimization method that determines the set of parameters (like D) that make the observed data most probable [4]. It performs exceptionally well, particularly with short trajectories or when localization errors are significant, and is known to determine the correct distribution of diffusion coefficients [4].

FAQ 4: How do I correct for finite-size effects in my simulation box?

The diffusion coefficient measured in a simulation with Periodic Boundary Conditions (DPBC) is influenced by hydrodynamic interactions with periodic images. You can apply a correction to estimate the value for an infinite system [2]:

$$D{\text{corrected}} = D{\text{PBC}} + \frac{2.84 k_{B}T}{6 \pi \eta L}$$

Where kB is Boltzmann's constant, T is temperature, η is the shear viscosity of the solvent, and L is the length of the cubic simulation box [2].

Experimental Protocols for Robust Diffusion Estimation

The following workflow outlines the key steps for calculating and statistically validating a diffusion coefficient from an MD trajectory, integrating the FAQ solutions.

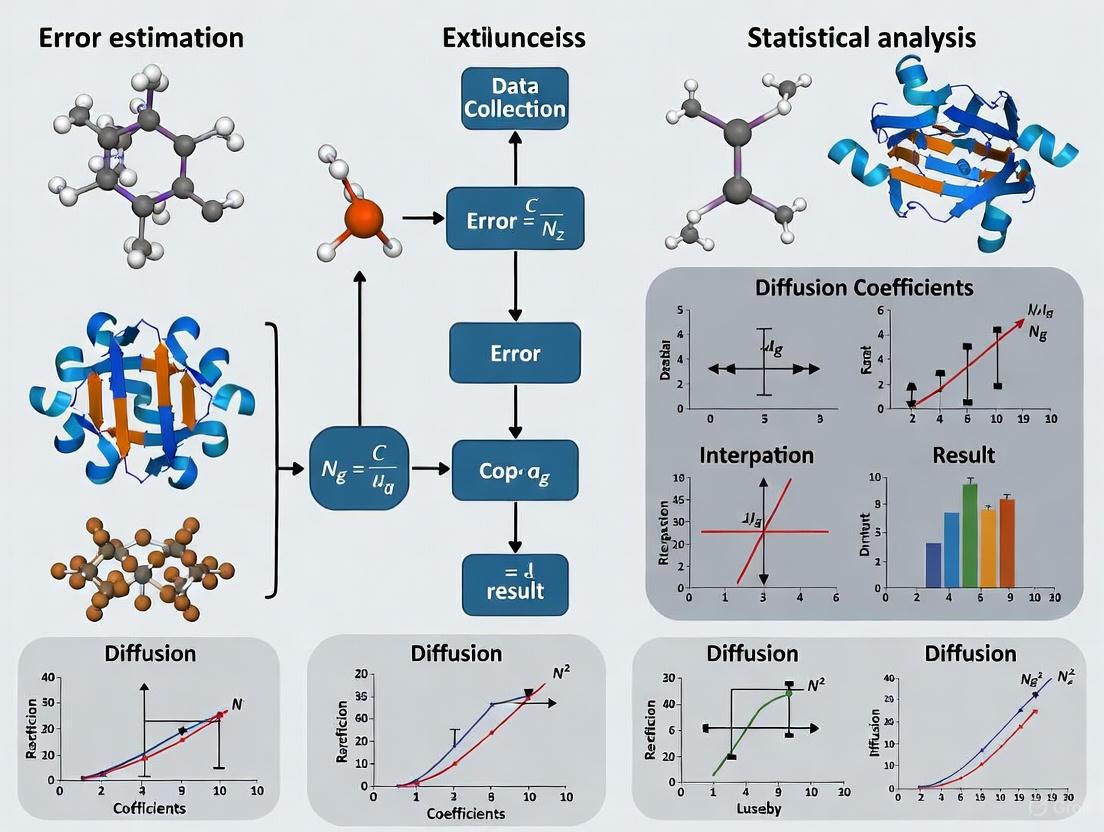

Diagram: Workflow for Estimating Diffusion Coefficients.

Step 1: Compute the MSD Calculate the MSD from your trajectory by averaging over all particles and multiple time origins [3] [2]. The general 3D formula is: $$MSD(t) = \langle | \mathbf{r}(t') - \mathbf{r}(t' + t) |^2 \rangle$$ where the angle brackets denote an average over all particles and time origins t' [2].

Step 2: Inspect the MSD and Identify the Diffusive Regime Plot the MSD against time. Do not fit the entire curve. Identify the long-time linear region where normal diffusion occurs and use this for fitting [2].

Step 3: Check for Normal Diffusion Before proceeding, it is crucial to verify that the system exhibits normal diffusion. Use a statistical test, such as a Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, to check if the observed dynamics are consistent with normal diffusion or if they are anomalous [5].

Step 4: Fit the MSD with an Appropriate Algorithm Fit the linear portion of the MSD curve to obtain the slope and thus the diffusion coefficient. The choice of fitting method directly impacts the reliability of your error estimate [3] [4].

Step 5: Apply Finite-Size Correction Use the Yeh-Hummer correction formula [2] provided in FAQ 4 to adjust your calculated D for the finite size of your simulation box.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Computational Tools for Diffusion Coefficient Research

| Tool / Reagent | Function / Purpose | Key Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| kinisi (Python package) | Implements Bayesian regression for estimating D from MSD with accurate uncertainty [3]. | The preferred tool to avoid underestimated errors from OLS fitting. Uses a parametrized covariance model. |

| Generalized Least-Squares (GLS) | A statistically efficient regression method that accounts for correlations in MSD data [3]. | Provides a point estimate equal to the Bayesian mean. Requires a model for the MSD covariance matrix. |

| Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE) | Estimates parameters by maximizing the probability of the observed trajectory [4]. | Superior to MSD-analysis for short trajectories or large localization errors. |

| Finite-Size Correction | Analytical formula to correct for system size effects in PBC simulations [2]. | Essential for obtaining the macroscopic diffusion coefficient from finite-sized simulations. |

| 3,3'-Difluorobenzaldazine | 3,3'-Difluorobenzaldazine, CAS:1049983-12-1; 15332-10-2, MF:C14H10F2N2, MW:244.245 | Chemical Reagent |

| 1,4-Butanediol mononitrate-d8 | 1,4-Butanediol mononitrate-d8, CAS:1261398-94-0, MF:C4H9NO4, MW:143.168 | Chemical Reagent |

Table: Comparison of Diffusion Coefficient Estimation Methods

| Method | Statistical Efficiency | Uncertainty Estimation | Key Assumptions Met? | Recommended Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) | Low | Significantly underestimates true uncertainty [3] | No (assumes independent, identically distributed data) [3] | Not recommended for final analysis. |

| Weighted Least Squares (WLS) | Moderate (better than OLS) | Still underestimates uncertainty [3] | No (accounts for heteroscedasticity but not correlation) [3] | A moderate improvement over OLS. |

| Generalized Least-Squares (GLS) | High (theoretically maximal) [3] | Accurate when correct covariance is used [3] | Yes (accounts for both heteroscedasticity and correlation) [3] | Optimal choice when accurate covariance matrix is known. |

| Bayesian Regression | High (theoretically maximal) [3] | Accurate (provides full posterior distribution) [3] | Yes (accounts for both heteroscedasticity and correlation) [3] | Optimal for reliable estimation and uncertainty quantification from a single trajectory. |

| Maximum Likelihood (MLE) | High (asymptotically optimal) [4] | Accurate [4] | Handles localization error and motion blur | Best for single-particle tracking with experimental noise [4]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the primary sources of uncertainty when determining diffusion coefficients from through-diffusion experiments?

The estimation of diffusion parameters (effective diffusion coefficient De, porosity ε, and adsorption coefficient KD) is affected by several experimental biases. Key sources of uncertainty include [6]:

- The presence of filters and tubing: Filters holding the clay sample in place and connecting tubing create dead volumes that can distort the estimation of diffusive fluxes and sample porosity.

- Sampling events: The periodic sampling of the low-concentration reservoir to measure tracer accumulation alters the concentration gradient across the diffusion cell, which is the fundamental driver of diffusion.

- O-ring and filter setups: The physical setup for delivering solutions to the clay packing can introduce unexpected errors in the applied concentration boundary conditions. A consistent numerical modeling approach that simultaneously accounts for all these factors, rather than treating them in isolation, is recommended for accurate parameter estimation [6].

Q2: How can I improve the accuracy of anomalous diffusion exponent (α) estimates from short single-particle trajectories?

For short trajectories, two major sources of error are significant statistical variance and systematic bias [7].

- For Variance: Employ ensemble-based estimation. By analyzing a collection of multiple particle trajectories collectively, you can characterize the method-specific noise and use this information to perform a shrinkage correction, which optimally combines information from individual trajectories with ensemble statistics.

- For Bias: Use time–ensemble averaged mean squared displacement (TEA-MSD). This approach provides a more reliable and length-invariant method for characterizing diffusion behavior, enabling accurate correction of systematic bias in the ensemble mean, particularly for normal and super-diffusive regimes [7].

Q3: What is the difference between "real-world uncertainty" and "statistical uncertainty"?

These terms reflect different scopes of what "uncertainty" means [8]:

- Statistical Uncertainty is a narrow, technically defined concept focused on repeatability. It answers the question: "If I repeated the data collection process many times, how much would my results vary just by chance?" It is often quantified by measures like the standard error.

- Real-World Uncertainty is a broader concept encompassing all "unknowns." This includes statistical uncertainty but also factors like measurement errors, unaccounted-for model simplifications, and systemic biases. A statistical margin of error often understates the total real-world uncertainty [8].

Q4: What framework can help ensure I've considered all major types of model-related uncertainty?

A useful "sources of uncertainty" framework breaks model-related uncertainty into four key areas [9]:

- Response Variable: Uncertainty in the primary variable you are trying to explain or predict (e.g., measurement error).

- Explanatory Variables: Uncertainty in the predictor variables (e.g., measurement error, missing data).

- Parameter Estimates: Uncertainty in the model's parameter values (e.g., standard errors, confidence intervals).

- Model Structure: Uncertainty about the model's mathematical form itself (e.g., whether a relationship is linear or non-linear). An audit of scientific papers showed that while no field fully considers all sources, this framework provides a checklist to improve the completeness of uncertainty reporting [9].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Inconsistent Diffusion Parameters Across Replicate Experiments

Potential Cause: Uncorrected Experimental Biases. The raw data from your through-diffusion experiments may be influenced by the physical setup of your apparatus, leading to a flawed estimation of De and ε [6].

Solution: Implement a Comprehensive Numerical Model.

- Action: Use a reactive transport code (e.g., CrunchClay with its CrunchEase interface) to model the entire experimental system directly, rather than just converting data into diffusive fluxes.

- Protocol:

- Model the Full Geometry: Explicitly include the dimensions and properties of the filters, tubing, and O-rings in your numerical model.

- Simulate Sampling Events: Model the actual process of sampling from the low-concentration reservoir, which changes its volume and concentration over time.

- Direct Data Fitting: Fit the model parameters directly to the measured (radio)tracer concentrations in the source and reservoir, rather than to the calculated fluxes. This approach more accurately accounts for the impact of the experimental biases on the final results [6].

Issue 2: High Variance and Bias in Anomalous Diffusion Exponents from Short Trajectories

Potential Cause: Inherent Statistical Limitations of Short Time Series. The variance of the exponent estimate α is inversely proportional to the trajectory length T: Var[α] ∠1/T. For very short trajectories, this variance becomes substantial. Furthermore, finite-length effects can introduce systematic bias [7].

Solution: Apply Ensemble-Based Correction Methods.

- Action: Leverage information from multiple trajectories to correct estimates from individual ones.

- Protocol for Variance Correction [7]:

- Calculate the estimated exponent α̂i for each trajectory i in your ensemble using your chosen method (e.g., TA-MSD).

- Compute the ensemble mean (μ̄α) and total observed variance (σ̂²total).

- Estimate the variance of your estimation method (σ²TAMSD) using a known relationship (e.g., for TA-MSD with specific lags, σ²TAMSD ≈ 0.9216/T).

- The corrected estimate for a trajectory can be derived by optimally combining the individual estimate with the ensemble mean, based on the relative magnitudes of the method variance and the true ensemble variance.

Protocol for Bias Correction [7]:

- Use the Time-Ensemble Averaged MSD (TEA-MSD), which averages displacement data across both time and multiple trajectories. This provides a more robust and less biased characterization of the diffusion process for short trajectories compared to single-trajectory TA-MSD.

The tables below summarize key quantitative data on measurement performance and uncertainty from the search results.

Table 1: Multi-Institution Performance of Apparent Diffusion Coefficient (ADC) Measurements in a Phantom Study [10]

| Performance Metric | Result | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Mean ADC Bias | < 0.01 × 10-3 mm²/s (0.81%) | Average difference between measured and ground-truth ADC. |

| Isocentre ADC Error Estimate | 1.43% | Error estimate at the center of the measurement. |

| Short-Term Repeatability | < 0.01 × 10-3 mm²/s (1%) | Intra-scanner variability over a short time. |

| Reproducibility | 0.07 × 10-3 mm²/s (9%) | Inter-scanner variability across multiple institutions. |

Table 2: Uncertainty Framework for Model-Related Uncertainty [9]

| Source of Uncertainty | Element in a Model | Examples of Uncertainty |

|---|---|---|

| Response Variable | The focal variable being explained/predicted. | Measurement or observation error. |

| Explanatory Variables | Variables used to explain the response. | Measurement error, missing data. |

| Parameter Estimates | Estimated model parameters (e.g., intercept, slope). | Standard errors, confidence intervals. |

| Model Structure | The mathematical form of the model itself. | Choice of a linear vs. a non-linear model. |

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol 1: Deriving Diffusion Parameters from Through-Diffusion Experiments

This protocol details the methodology for interpreting through-diffusion data to determine De, ε, and KD, while correcting for experimental biases [6].

1. Experimental Setup:

- A clay sample of thickness Ls and cross-sectional area A is packed into a diffusion cell.

- A high-concentration reservoir with tracer concentration c0 is maintained on one side.

- A low-concentration reservoir is kept near zero by periodic replacement and sampling.

2. Data Collection:

- Over time tn, sample the low-concentration reservoir, measuring the tracer concentration cL(tn) and volume VL(tn) at each interval.

- Calculate the cumulated amount of tracer Q(tn) in the low-concentration reservoir: Q(tn) = Σ cL(tn) VL(tn) [6].

- The experimental tracer diffusive flux Fexp(tn) is evaluated using a numerical derivative (e.g., backward difference): Fexp(tn) = [Q(tn) - Q(tn-1)] / [(tn - tn-1) A] [6].

3. Numerical Interpretation with Bias Correction:

- Instead of directly fitting an ideal model to Fexp, use a reactive transport code to create a digital twin of the experiment.

- The model should incorporate the geometry of filters, tubing volumes, and simulate reservoir volume changes during sampling events.

- The model solves Fick's second law, often in a form simplified for homogeneous media [6]:

∂c/∂t = [D<sub>e</sub> / (ε + Ï<sub>d</sub>K<sub>D</sub>)] * (∂²c/∂x²) - Model parameters (De, ε, KD) are optimized by fitting the model's output directly to the measured reservoir concentration data, thereby accounting for biases in the system.

The following workflow diagrams the process of estimating parameters while accounting for different uncertainty sources.

Diagram 1: Through-diffusion parameter estimation workflow.

Protocol 2: Ensemble-Based Estimation of Anomalous Diffusion Exponents

This protocol is designed for analyzing single-particle tracking (SPT) data to estimate the anomalous diffusion exponent α for cases where trajectories are short, a common scenario in live-cell imaging [7].

1. Data Preprocessing:

- Obtain a set of M two-dimensional particle trajectories, each of length T coordinates: (X(t), Y(t)).

2. Single-Trajectory Exponent Estimation (TA-MSD Method):

- For each trajectory i, compute the Time-Averaged Mean Squared Displacement (TA-MSD) for a range of lag times Ï„ [7]:

TA-MSD(τ) = (1/(T-τ)) * Σ [ (X(t+τ) - X(t))² + (Y(t+τ) - Y(t))² ](sum from t=1 to t=T-τ) - Perform a linear regression of

log(TA-MSD(τ))againstlog(τ). - The slope of this regression line is the estimate for the anomalous diffusion exponent, α̂i, for trajectory i.

3. Ensemble-Based Correction:

- Calculate Ensemble Statistics: Compute the mean (μ̄α) and total variance (σ̂²total) of all α̂i estimates.

- Apply Variance Correction: Use the known relationship between estimation variance and trajectory length for your method (e.g., for TA-MSD, Var[α̂] ≈ 0.9216 / T for lags {1,2,3,4}) to refine the individual estimates by shrinking them toward the ensemble mean.

- Apply Bias Correction: For a more robust estimate of the ensemble's true α, calculate the Time-Ensemble Averaged MSD (TEA-MSD), which averages displacement data across all trajectories and time points, and then perform the log-log regression on this consolidated dataset.

The following flowchart visualizes this ensemble-based correction methodology.

Diagram 2: Ensemble-based correction workflow for anomalous diffusion analysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Tools for Diffusion Experimentation

| Item | Function / Relevance |

|---|---|

| Room-Temperature DWI Phantom | A standardized object containing a reference material with a known ground-truth Apparent Diffusion Coefficient (ADC). It is used for quality assurance and multi-scanner validation studies without the complexity of an ice-water setup [10]. |

| MR-Readable Thermometer | Critical for accurately measuring the temperature of a phantom or sample during diffusion experiments. Enables correction of measured ADC values to their ground-truth values based on temperature-dependent diffusion properties [10]. |

| Reactive Transport Code (e.g., CrunchClay) | A numerical software platform that models the coupled processes of chemical reaction and transport (e.g., diffusion) in porous media. Essential for implementing advanced interpretation models that correct for experimental biases [6]. |

| Graphical User Interface (e.g., CrunchEase) | A tool that automates the creation of input files, running of simulations, and extraction of results for complex models. Makes advanced reactive transport modeling accessible to experimentalists without a deep background in computational science [6]. |

| Fractional Brownian Motion (fBm) Simulator | A computational tool to generate synthetic trajectories of anomalous diffusion. Used for method validation, testing the performance of estimation algorithms, and training machine learning models under controlled conditions [7]. |

| Ethyl 5-methyl-1H-pyrazole-3-carboxylate | Ethyl 5-methyl-1H-pyrazole-3-carboxylate, CAS:886495-75-6, MF:C7H10N2O2, MW:154.17 g/mol |

| D(+)-Galactosamine hydrochloride | D(+)-Galactosamine hydrochloride, CAS:1886979-58-3, MF:C6H14ClNO5, MW:215.63 g/mol |

The Importance of Accurate Diffusion Data in Drug Development and Biomaterial Design

Your Troubleshooting Guide for Diffusion Data Challenges

This guide addresses common experimental issues in diffusion coefficient estimation, providing targeted solutions to enhance the reliability of your data in drug and biomaterials research.

Problem: High Uncertainty in Estimated Diffusion Coefficients from MD Simulations

- Question: "My molecular dynamics (MD) simulations produce mean squared displacement (MSD) data with significant noise, leading to high uncertainty in my diffusion coefficient (D*). How can I obtain a more reliable and statistically efficient estimate?"

- Solution: Replace Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regression with a method that accounts for the statistical nature of MSD data.

- Root Cause: MSD data points are serially correlated (each point depends on the previous one) and heteroscedastic (their variance changes over time). OLS assumes data points are independent and identically distributed, violating these assumptions and leading to inefficient estimates and a significant underestimation of the statistical uncertainty [3].

- Recommended Protocol: Employ Bayesian regression or Generalized Least Squares (GLS) using an analytically derived covariance matrix, Σ, which models the correlations and changing variances in the MSD data [3].

- Procedure:

- Calculate the observed MSD from your trajectory.

- Parametrize a model covariance matrix, Σ′, from your observed data. This matrix approximates the true covariance structure of an equivalent system of freely diffusing particles.

- Use this covariance matrix in a Bayesian regression framework to sample the posterior distribution of linear models (m = 6Dt + c) that fit the MSD data.

- The mean of the posterior distribution for D provides a statistically efficient point estimate, and the spread of the distribution accurately quantifies its uncertainty [3].

- Tools: This method is implemented in the open-source Python package

kinisi[3].

Problem: Weak Signal and Fluorescence Interference in Experimental Diffusion Measurements

- Question: "When measuring molecular diffusion in biological tissues or hydrogels using Raman spectroscopy, the signal is weak and overwhelmed by background fluorescence and autofluorescence. How can I improve the signal-to-noise ratio?"

- Solution: Utilize Stimulated Raman Scattering (SRS) microscopy instead of spontaneous Raman spectroscopy [11].

- Root Cause: Spontaneous Raman scattering is an inherently weak process, where only 1 in 10⸠photons is inelastically scattered. In complex, biological samples, this weak signal is often obscured by a strong fluorescent background [11].

- Recommended Protocol: SRS employs two pulsed lasers (a pump and a Stokes beam) that coherently excite molecular vibrations. This process amplifies the Raman signal by several orders of magnitude and is inherently free from fluorescence interference [11].

- Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Use a model compound with a distinct Raman signature in a silent region of the spectrum. A robust choice is deuterated glucose (d7-glucose), as its C-D stretching vibration is spectrally isolated from native C-H vibrations [11].

- Data Acquisition: Construct a sample holder (e.g., a thin glass cuvette) containing your hydrogel or tissue slice. Add the deuterated glucose solution on top and use the SRS system to monitor the C-D band intensity over time and space [11].

- Data Analysis: The SRS signal is proportional to the concentration of the probe molecule. By measuring the spatiotemporal concentration profile, you can calculate the diffusion coefficient, even in highly scattering samples like tissues [11].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

How can I generate data for drug discovery when experimental diffusion data is sparse or missing?

Answer: Diffusion models, a class of generative artificial intelligence, can create high-quality synthetic data to address data sparsity.

- Application: A novel diffusion GNN model called Syngand can generate synthetic ligand and pharmacokinetic data end-to-end [12].

- Methodology: These models learn the underlying distribution of existing, sparse datasets. Researchers can then sample from this learned distribution to generate novel, synthetic data points that span multiple datasets, enabling the exploration of research questions that would otherwise be limited by data availability [12].

- Utility: This synthetically generated data has been shown to improve the performance of downstream prediction tasks, such as regression models for properties like solubility (AqSolDB) and toxicity (LD50, hERG) [12].

My molecule's diffusion in biological tissue doesn't follow classical Fickian laws. What does this mean?

Answer: Observing non-Fickian or anomalous diffusion often indicates more complex, biologically relevant transport mechanisms.

- Interpretation: While mass transport within simple hydrogel matrices may follow Fickian diffusion, diffusion within tissues is often more complex due to interactions with cellular structures, binding events, and the heterogeneous nature of the extracellular matrix [11].

- Investigation Path: Use advanced diffusion measurement techniques like SRS (see above) to accurately characterize these complex profiles. Then, model the data using more sophisticated frameworks beyond the simple Einstein relation to gain insights into the specific transport barriers and mechanisms at play [11].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents & Computational Tools

This table details key materials and software essential for advanced diffusion studies.

| Item Name | Function/Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Deuterated Glucose (d7-glucose) | A model small molecule for tracing diffusion in biomaterials and tissues using SRS [11]. | C-D bond provides a distinct Raman signature in a spectrally "silent" region, free from interference [11]. |

| Stimulated Raman Scattering (SRS) Microscope | Measures molecular diffusion in highly scattering or fluorescent samples (e.g., tissues, hydrogels) [11]. | Amplifies Raman signals; eliminates fluorescence background; provides high-contrast, real-time chemical imaging [11]. |

kinisi Python Package |

Accurately estimates self-diffusion coefficients (D*) and their uncertainties from MD simulation trajectories [3]. | Implements Bayesian regression with a model covariance matrix for high statistical efficiency from a single simulation [3]. |

| Syngand Model | A diffusion-based generative model that creates synthetic ligand and pharmacokinetic data [12]. | Addresses data sparsity in AI-based drug discovery by generating data for multi-dataset research questions [12]. |

| N-Valeryl-D-glucosamine | N-Valeryl-D-glucosamine, MF:C11H21NO6, MW:263.29 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Burnettramic acid A aglycone | Burnettramic acid A aglycone, MF:C35H61NO7, MW:607.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Experimental & Statistical Workflows

The following diagrams outline core methodologies for obtaining accurate diffusion data.

SRS Diffusion Measurement

Bayesian D* Estimation

FAQs on Fundamental Concepts

1.1 What is the fundamental difference between MSD and ADC?

The Mean Squared Displacement (MSD) and Apparent Diffusion Coefficient (ADC) are related but distinct metrics for quantifying particle motion. The MSD is a direct measure of the deviation of a particle's position over time, representing the spatial extent of its random motion. It is calculated as the average of the squared distance a particle travels over a given time lag [13]. In contrast, the ADC is a derived parameter that represents the measured diffusion coefficient in a voxel or region of interest, reflecting the average mobility of water molecules as influenced by the local tissue microenvironment and experimental conditions [14]. The ADC is essentially the diffusion coefficient calculated from MRI measurements, and it is "apparent" because it is influenced by numerous biophysical factors and experimental setups, unlike the theoretical diffusion coefficient of pure water [14].

1.2 In what types of experiments should I use MSD versus ADC?

Your choice of metric depends on your imaging modality and experimental goal.

- Use MSD primarily in Single Particle Tracking (SPT) experiments. These are typically optical microscopy techniques (e.g., interferometric scattering microscopy) where you follow the trajectory of individual particles, such as molecules in a cell membrane, over time [15]. MSD analysis is applied to the reconstructed particle path.

- Use ADC in Diffusion Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) studies. This is the standard metric for quantifying water diffusion in clinical and biological research MRI. It provides a voxel-averaged measure of water mobility, which is sensitive to tissue cellularity, microstructure, and integrity [16] [14] [17].

1.3 My ADC values are inconsistent across repeated scans. What are the common sources of this variability?

Inconsistent ADC measurements are a well-documented challenge, often stemming from both technical and biological factors [18].

- Scanner-related Factors: Significant variations in ADC values can occur between different MRI scanner manufacturers, models, and even across scanners of the same model. Instabilities in the gradient system or the reference voltage can also lead to fluctuations [19] [18].

- Sequence and Protocol Choices: The selection of b-values (the diffusion-weighting parameters) greatly influences the ADC. Using a 2-point method (e.g., b=0, b=800 s/mm²) is common but can be less consistent than a multi-point b-value technique [18]. The imaging sequence itself (e.g., single-shot echo-planar imaging vs. turbo spin echo) can also introduce variability [18].

- Sample Environment: Temperature variations can affect both the diffusion of water molecules and the performance of electronic components in the scanner, leading to ADC drift [19]. Fat suppression techniques in bone marrow imaging have also been shown to yield significantly different ADC values [16].

Troubleshooting Guides

Troubleshooting MSD Measurements in Single Particle Tracking

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Erroneously detected subdiffusion or overestimated diffusion coefficients [15]. | Localization uncertainty is overlooked, especially problematic at short time lags where particle displacement is comparable to the error [15]. | Use an analysis pipeline that explicitly accounts for localization error, such as the Apparent Diffusion Coefficient (ADC) analysis in the TRAIT2D software [15]. |

| Spurious results at short time ranges [15]. | Motion blurring inherent in SPT due to particle movement during frame acquisition [15]. | Ensure your analysis method corrects for motion blur. Select an appropriate number of data points for MSD fitting, as relying on very first points can be misleading [15]. |

| Inability to track particles accurately at high framerates. | Conventional tracking algorithms may not be optimized for long, uninterrupted, high-speed trajectories [15]. | Employ tracking algorithms designed for high sampling rates that favor strong spatial and temporal connections between consecutive frames [15]. |

Experimental Protocol for Robust MSD Analysis:

- Data Acquisition: Acquire particle trajectories using a high-speed microscopy technique (e.g., iSCAT) [15].

- Particle Localization: Identify particle positions with sub-pixel precision using an algorithm like the radial symmetry centre approach [15].

- Trajectory Linking: Construct trajectories using a linking algorithm suitable for high-frame-rate data [15].

- MSD Calculation: Compute the MSD for each trajectory using the formula:

MSD(n∙Δt) = 1/(N-n) ∙ Σ [r((i+n)∙Δt) - r(i∙Δt)]², wherer(t)is the position at timet,Δtis the time between frames, andnis the time lag index [13]. - Model Fitting: Fit the MSD plot to an appropriate diffusion model (e.g., Brownian, confined). Use statistical model selection to identify the best model and be cautious of over-interpreting short-time-lag data [15].

Troubleshooting ADC Measurements in Diffusion MRI

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Fluctuating ADC readings, even with a stable phantom [19] [18]. | System noise from electromagnetic interference, power supply noise, or crosstalk [19]. | Use decoupling capacitors near the ADC's power supply pins. Employ a stable, precision external reference voltage source instead of the scanner's internal reference [19] [18]. |

| Significant differences in ADC values between scanners or sites [18]. | Lack of protocol standardization, including different b-values, sequences, and scanners [18]. | Implement standardized, multicenter imaging protocols. Use a liquid isotropic phantom for cross-calibration and quality assurance across all scanners [18]. |

| ADC values that drift over time or with changes in ambient temperature [19]. | Temperature variations affecting the sample and scanner electronics [19]. | Use components with low temperature coefficients. Monitor scanner room temperature. For longitudinal studies, schedule scans at a consistent time of day. |

| Clipped or low-resolution ADC measurements [19]. | Mismatch between the input signal's range and the ADC's input range [19]. | Use signal conditioning circuits to scale the input signal to match the ADC's input range optimally. |

| Incorrect signal representation or aliasing artifacts [19]. | Insufficient sampling rate violating the Nyquist theorem [19]. | Increase the sampling rate to at least 2.5 times the highest frequency in the input signal. Use an anti-aliasing filter. |

Experimental Protocol for Robust ADC Measurement in MRI:

- Phantom Calibration: For multicenter studies or longitudinal quality control, use a standardized liquid isotropic phantom to assess reproducibility across MRI systems [18].

- Sequence Selection: Consider using a Turbo Spin Echo (TSE) sequence over single-shot Echo-Planar Imaging (ssEPI) if possible, as TSE has been shown to yield more homogeneous ADC values [18].

- b-value Selection: Employ a multi-point b-value technique (e.g., b=0, 50, 500, 1000, 1500 s/mm²) instead of a 2-point method for more consistent and accurate ADC fitting [18].

- ADC Calculation: The ADC is calculated per voxel by fitting the signal decay across different b-values to the equation:

S_b = S_0 * exp(-b * ADC), whereS_bis the signal intensity with diffusion weightingb, andS_0is the signal without diffusion weighting [14].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Liquid Isotropic Phantom | A standardized reference material used to calibrate MRI scanners, assess the reproducibility of ADC measurements across different platforms and sites, and control for variables not present in living tissue [18]. |

| Fat Suppression Pre-pulses (STIR, SSRF) | Techniques used in MRI to suppress the signal from fat tissue, which is crucial for obtaining accurate ADC measurements of water diffusion in tissues like bone marrow. Different techniques can yield different ADC values [16]. |

| Decoupling Capacitors | Passive electronic components placed near the power supply pins of ADC units to filter out high-frequency noise, ensuring a clean power source and reducing fluctuating readings [19]. |

| Anti-aliasing Filter | A low-pass filter applied before the ADC sampling process to attenuate signal frequencies higher than half the sampling rate, preventing aliasing artifacts and incorrect signal representation [19]. |

| TRAIT2D Software | An open-source Python library for tracking and analyzing single particle trajectories. It provides localization-error-aware analysis pipelines for calculating MSD and ADC, and includes simulation tools [15]. |

Workflow Visualization

MSD Analysis Workflow

ADC Measurement Workflow

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the practical difference between the variance and the covariance?

Variance measures how much a single random variable spreads out from its own mean. In contrast, covariance measures how two variables change together; a positive value indicates they tend to move in the same direction, while a negative value suggests they move in opposite directions [20]. In the context of estimating a diffusion coefficient, you might calculate the variance of repeated measurements at a single time point. You would examine covariance to understand if the measurement error at one time point is related to the error at another.

2. How is a variance-covariance matrix estimated from my experimental data?

For a dataset with p variables and n independent observations, the unbiased estimate for the variance-covariance matrix Q is calculated using the formula [20]:

Q = 1/(n-1) * Σ (x_i - x̄)(x_i - x̄)^T

where x_i is the i-th observation vector and x̄ is the sample mean vector. The factor n-1 (Bessel's correction) ensures the estimate is unbiased. For diffusion data, each variable might represent the measured particle position at a different time, and this matrix would quantify the variability and co-variability of these positions across time.

3. My statistical software reports a confidence interval. What is the correct interpretation?

A 95% confidence interval means that if you were to repeat the entire data collection and interval calculation process many times, approximately 95% of the calculated intervals would contain the true population parameter [21]. It is incorrect to say there is a 95% probability that a specific calculated interval contains the true value; the true value is fixed, and the interval either contains it or it does not [21]. For example, a 95% CI for a diffusion coefficient means that the method used to create the interval is reliable 95% of the time over the long run.

4. When should I use a prediction interval instead of a confidence interval?

Use a confidence interval to estimate an unknown population parameter, like a true mean diffusion coefficient. Use a prediction interval to express the uncertainty in predicting a future single observation [21]. A confidence interval for a diffusion coefficient estimates the true coefficient itself, while a prediction interval would bracket where you expect the next measured coefficient from a new experiment to fall.

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: High Variance in Estimated Diffusion Coefficients

Problem: Calculated diffusion coefficients from replicate experiments show high variance, making the results unreliable.

Diagnosis: This often stems from uncontrolled environmental factors or measurement system noise.

Solution:

- Step 1: Control Experimental Conditions. Ensure temperature, solvent viscosity, and sample purity are consistent across all replicates. Uncontrolled fluctuations directly contribute to observed variance.

- Step 2: Calibrate Instrumentation. Verify the calibration of all measurement equipment (e.g., microscopes, light scatterers). High instrument noise inflates variance.

- Step 3: Increase Sample Size. If the inherent variability is high, a larger number of experimental replicates (

n) will lead to a more precise estimate of the mean, as the standard error decreases with the square root ofn[21].

Issue 2: Interpreting the Variance-Covariance Matrix Output

Problem: A statistical package has produced a variance-covariance matrix, but you are unsure how to interpret its values.

Diagnosis: The diagonal and off-diagonal elements have distinct meanings.

Solution:

- Step 1: Read the Diagonals. The diagonal elements are the variances of each individual parameter estimate. A large value indicates high uncertainty for that specific parameter.

- Step 2: Read the Off-Diagonals. The off-diagonal elements are the covariances between two parameter estimates. A large absolute value (positive or negative) indicates that the errors in estimating those two parameters are related.

- Step 3: Check for Correlation. High covariance can sometimes make a model numerically unstable. If two parameters have a very high covariance, it may suggest they are not both independently needed in your model.

Issue 3: Confidence Interval is Too Wide

Problem: The calculated confidence interval for your parameter of interest (e.g., a mean) is too broad to be useful for drawing conclusions.

Diagnosis: The interval width is driven by the variability in the data and the sample size.

Solution:

- Step 1: Investigate Sources of Variability. Analyze your experimental process for sources of excessive noise. The solution to Issue 1 may also help here.

- Step 2: Increase Sample Size. This is the most direct way to narrow a confidence interval. The width of the interval is proportional to

1/√n[21]. Doubling your sample size reduces the interval width by about 30%. - Step 3: Check for Outliers. Examine your data for anomalous points that could be artificially inflating the measured variance. Use diagnostic plots or robust statistical methods if outliers are present [20].

Essential Formulas and Data

Key Formulas for Error Estimation

Table 1: Core formulas for variance, covariance, and confidence intervals.

| Concept | Formula | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Variance (s²) | s² = Σ(xi - x̄)² / (n - 1) [22] [20] |

Measures the average squared deviation from the mean. Unbiased estimator of population variance. |

| Sample Covariance | Cov(X,Y) = Σ(xi - x̄)(yi - ȳ) / (n - 1) [20] |

Measures the direction of the linear relationship between two variables. |

| 95% CI for Mean (μ) | x̄ ± t*(s / √n) [21] |

Provides a range of plausible values for the population mean. t* is the critical value from the t-distribution with n-1 degrees of freedom. |

| Variance-Covariance Matrix (Sample Estimate) | Q = 1/(n-1) * Σ (xi - x̄)(xi - x̄)^T [20] |

A square matrix where diagonals are variances and off-diagonals are covariances. |

Statistical Software Toolkit

Table 2: Common statistical software packages and their applications in research.

| Software | Primary Users | Key Features & Highlights | Potential Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| SPSS | Social Sciences, Health Sciences, Marketing [23] | Intuitive menu-driven interface; easy data handling and missing data management [23]. | Absence of some robust regression methods; limited complex data merging [23]. |

| Stata | Economics, Political Science, Public Health [23] | Powerful for panel, survey, and time-series data; strong data management; integrates matrix programming [23]. | Limited graph flexibility; only one dataset in memory at a time [23]. |

| SAS | Financial Services, Government, Life Sciences [23] | Handles extremely large datasets; powerful for data management; many specialized components [23]. | Graphics can be cumbersome; steep learning curve for new users [23]. |

| R | Data Science, Bioinformatics, Finance [23] | Vast array of statistical packages; high-quality, customizable graphics (e.g., ggplot2); free and open-source [23]. | Command-line driven, requiring programming knowledge; steeper initial learning curve [23]. |

| (1R,2S,3R)-Aprepitant | (1R,2S,3R)-Aprepitant, CAS:221350-96-5, MF:C23H21F7N4O3, MW:534.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| (Tyr0)-C-peptide (human) | (Tyr0)-C-peptide (human), MF:C138H220N36O50, MW:3183.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Experimental Protocol: Estimating a Diffusion Coefficient and its Confidence Interval

Objective: To determine the diffusion coefficient (D) of a fluorescently labeled molecule in a solution and report its value with a 95% confidence interval.

1. Materials and Reagents

- Purified Molecule of Interest: The analyte whose diffusion is being measured.

- Fluorescent Label: A stable, bright fluorophore that does not alter the molecule's hydrodynamic properties.

- Imaging Buffer: A chemically defined buffer to maintain pH and ionic strength.

- Coverslip Chamber: A sample holder for microscopy.

- Confocal Microscope or Light Scattering Instrument: Equipment capable of tracking particle movement.

2. Methodology

- Step 1: Sample Preparation. Dilute the labeled molecule to an appropriate concentration in the imaging buffer to minimize particle interaction. Load the sample into the imaging chamber.

- Step 2: Data Acquisition. Using a single-particle tracking or dynamic light scattering protocol, record the trajectories or intensity fluctuations of the molecules. Ensure data is collected for a sufficient duration to capture the diffusion behavior. Repeat this process for a minimum of

n = 30independent experimental replicates. - Step 3: Calculate Diffusion Coefficients. For each replicate

i, fit the mean squared displacement (MSD) to the relationMSD(Ï„) = 4D_i Ï„(for 2D diffusion) to obtain an estimate of the diffusion coefficientD_ifor that replicate. - Step 4: Statistical Summary. Calculate the sample mean (

DÌ„) and sample standard deviation (s) of thenestimated diffusion coefficients. - Step 5: Construct Confidence Interval. Using

D̄,s, andn, calculate the 95% confidence interval asD̄ ± t*(s / √n), wheret*is the critical value from a t-distribution withn-1degrees of freedom [21].

Visualizations

Statistical Analysis Workflow

Relationship Between Sample Size and Confidence Interval

From Theory to Practice: Methods for Estimating Diffusion Coefficients

Troubleshooting Guide: Common MD Simulation Errors

Frequently Encountered Errors in GROMACS

Q: What does the error "Out of memory when allocating" mean and how can I resolve it?

A: This error occurs when the program cannot assign the required memory for the calculation [24]. Solutions include:

- Reducing the number of atoms selected for analysis.

- Processing a shorter trajectory length.

- Verifying unit consistency (e.g., confusion between Ångström and nm can create a system 10³ times larger than intended) [24].

- Using a computer with more memory [24].

Q: How should I address "Residue 'XXX' not found in residue topology database" from pdb2gmx?

A: This means your selected force field lacks parameters for residue 'XXX' [24]. To resolve this:

- Verify the residue name in your PDB file matches the name in the force field's residue database.

- If no database entry exists, you cannot use pdb2gmx and must:

- Parameterize the residue yourself.

- Find a topology file for the molecule and include it in your topology.

- Use a different force field with parameters for this residue [24].

Q: What causes "Found a second [defaults] directive" in grompp and how do I fix it?

A: This error occurs when the [defaults] directive appears more than once in your topology or force field files [24]. To fix it:

- Locate and comment out or delete the duplicate

[defaults]section in the secondary file. - Avoid mixing force fields, as this often causes the issue [24].

Q: What is the correct way to include position restraints for multiple molecules?

A: Position restraint files must be included immediately after their corresponding [moleculetype] block [24].

Correct Implementation:

Common Mistakes in MD Simulation Setup

Q: What are critical checks before starting a production MD simulation?

A: Before launching your simulation, always [25]:

- Check 1: Match temperature and pressure coupling parameters to those used in your NVT and NPT equilibration steps.

- Check 2: Use the auto-fill input path feature when building upon a previous equilibration to prevent manual path errors.

- Check 3: Tune advanced parameters (via the "All..." button) for custom constraints or force settings.

- Check 4: Save your configuration and consider exporting parameter sets for version control.

Q: Why is structure preparation so important and what should I check?

A: Simulation quality depends directly on your starting structure [26]. Proper preparation involves checking for:

- Missing atoms or residues.

- Steric clashes and unrealistic geometries.

- Correct protonation states at your simulation pH.

- Appropriate tautomers [26]. Use tools like pdbfixer or H++ to assist with preparation [26].

Q: How do I choose an appropriate time step?

A: An inappropriate timestep is a common mistake [26].

- A too large timestep causes numerical instability, unrealistic atom movement, and simulation failure.

- A too small timestep wastes computational resources without improving accuracy [26]. Balance accuracy and efficiency by considering your force field, bonded constraints, atomic masses, and use of virtual sites [26].

Q: How can I avoid artefacts from Periodic Boundary Conditions (PBC)?

A: PBCs can cause molecules to appear split across box boundaries [26]. To prevent analysis errors:

- Use built-in correction tools before analysis (e.g.,

gmx trjconvin GROMACS with the-pbc nojumpflag orcpptrajin AMBER) [26] [27]. - Always make molecules "whole" before calculating metrics like RMSD, hydrogen bonds, or distances [26].

Troubleshooting Guide: MSD Analysis for Diffusion Coefficients

Common Problems in MSD Analysis

Q: My MSD values are orders of magnitude too large. What is the most likely cause?

A: This often indicates a unit mismatch between the coordinate units in your trajectory and the expected units of the MSD analysis tool [28]. Verify the units of your input data (e.g., nm vs. μm) and apply consistent scaling. Ensure your trajectory is in unwrapped coordinates to avoid artificial suppression of diffusion from periodic boundary wrapping [27].

Q: How many MSD points should I use to fit the diffusion coefficient D?

A: The optimal number of MSD points (p_min) for fitting is critical and depends on the reduced localization error x = σ²/DΔt (where σ is localization uncertainty, D is diffusion coefficient, and Δt is frame duration) [29].

- When

x << 1(small localization error), use the first two MSD points. - When

x >> 1(significant localization error), a larger number of points is needed [29]. The optimal numberp_mindepends on bothxandN(total trajectory points) and can be determined theoretically [29].

Q: What defines a reliable MSD curve for calculating diffusivity?

A: A reliable MSD curve should have a linear segment at intermediate time lags [27]. Exclude:

- Short time lags: May exhibit ballistic, non-diffusive motion.

- Long time lags: Suffer from poor averaging and increased statistical error [29] [27]. Use a log-log plot to identify the linear region, which should have a slope of 1 [27].

Q: Why are replicate simulations important for MSD analysis?

A: A single trajectory may not represent the system's full thermodynamic behavior or may be trapped in a local minimum [26]. Multiple replicates:

- Provide better statistical sampling of conformational space.

- Increase confidence in observed behaviors and calculated diffusion coefficients.

- Help distinguish true diffusion from artifacts or rare events [26].

Important: When combining MSDs from multiple replicates, average the MSDs themselves (combined_msds = np.concatenate(...)) rather than concatenating trajectory coordinates, which creates artificial jumps [27].

Quantitative Data for MSD Analysis

Table 1: Key Parameters for Optimal MSD Fitting [29]

| Parameter | Symbol | Effect on MSD Analysis | Practical Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reduced Localization Error | x = σ²/DΔt |

Determines the optimal number of MSD points for fitting. | Use theoretical expression to find p_min based on your x and N. |

| Localization Uncertainty | σ |

Increases variance of initial MSD points. | Dominates error when x >> 1. Calculate from PSF and photon count [29]. |

| Trajectory Length | N |

Longer trajectories improve averaging. | For small N, p_min may be as large as N. |

| Frame Duration | Δt |

Shorter intervals better capture motion. | Affects x. Balance with signal-to-noise. |

Table 2: MSD Fitting Guidelines for Diffusion Coefficient Calculation [29] [27]

| Condition | Optimal Number of Fitting Points | Fitting Method | Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

Small Localization Error (x << 1) |

First 2 points | Unweighted least squares | Reliable estimate of D. |

Significant Localization Error (x >> 1) |

p_min (theoretically determined) |

Unweighted or weighted least squares | Requires more points for reliable D. |

| General Case | Linear portion of MSD curve | Linear regression on MSD ~ 2dDÏ„ |

Slope gives 2dD, where d is dimensionality. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: System Preparation and Equilibration for MD

- Structure Preparation: Obtain initial coordinates (e.g., from PDB). Check for missing atoms/residues, assign correct protonation states, and correct steric clashes using tools like pdbfixer [26].

- Topology Generation: Use

pdb2gmxor similar to generate topology within your chosen force field. Ensure all residues are recognized [24]. - System Assembly: Solvate the protein in an appropriate water box and add ions to neutralize the system and achieve desired concentration.

- Energy Minimization: Use steepest descent or conjugate gradient minimisation to remove bad contacts and relax the system [26].

- Equilibration:

- NVT Equilibration: Equilibrate the system at constant temperature (e.g., 300 K) using a thermostat (e.g., Berendsen, Nosé-Hoover).

- NPT Equilibration: Further equilibrate at constant pressure (e.g., 1 bar) using a barostat (e.g., Parrinello-Rahman). Verify stabilization of temperature, pressure, density, and potential energy before proceeding to production [25] [26].

Protocol 2: Calculating Diffusion Coefficient from MSD

- Trajectory Requirement: Ensure your trajectory is in unwrapped coordinates (use

gmx trjconv -pbc nojumpfor GROMACS) [27]. - Compute MSD: Calculate the ensemble-averaged MSD using the Einstein formula. For efficient computation, use an FFT-based algorithm if available [27].

MSD = msd.EinsteinMSD(u, select='all', msd_type='xyz', fft=True) - Identify Linear Region: Plot MSD vs. lag time (Ï„) on a log-log plot. Identify the intermediate time-lag region where the slope is approximately 1 [27].

- Fit MSD to Einstein Relation: Within the linear region, perform a linear fit:

MSD(Ï„) = 2dDÏ„, wheredis the dimensionality [27].linear_model = linregress(lagtimes[start_index:end_index], msd[start_index:end_index]) - Calculate D: Extract the slope and compute the diffusion coefficient:

D = slope / (2 * d)[27]. - Repeat and Average: Perform this analysis on multiple independent simulation replicates and average the results for a statistically robust measurement [26] [27].

Diagrams and Workflows

MD Setup and Analysis Workflow

MSD Analysis for Diffusion Coefficient

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for MD Simulations

| Tool/Software | Primary Function | Key Application in Research |

|---|---|---|

| GROMACS | Molecular dynamics package | High-performance MD simulation engine for running production simulations [24]. |

| pdb2gmx | Topology generator | Creates molecular topologies from coordinate files, assigning force field parameters [24]. |

| grompp | Preprocessor | Processes topology and parameters to create a run input file [24]. |

| MDAnalysis | Trajectory analysis | Python library for analyzing MD trajectories, including MSD calculations [27]. |

| EinsteinMSD | MSD analysis | Specific class in MDAnalysis for computing mean squared displacement via Einstein relation [27]. |

| CHARMM36m | Force field | Optimized for proteins, provides parameters for bonded and non-bonded interactions [26]. |

| GAFF2 | Force field | General Amber Force Field for organic molecules and drug-like compounds [26]. |

| gmx trjconv | Trajectory processing | Corrects periodic boundary conditions and unwraps coordinates for accurate MSD analysis [26] [27]. |

| Aromadendrin 7-O-rhamnoside | Aromadendrin 7-O-rhamnoside, MF:C21H22O10, MW:434.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Methiothepin Mesylate | Methiothepin Mesylate, CAS:74611-28-2, MF:C21H28N2O3S3, MW:452.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Bayesian Regression for Optimal Estimation from MSD Data

Quantitative tracking of particle motion using live-cell imaging is a powerful approach for understanding the transport mechanisms of biological molecules, organelles, and cells. However, inferring complex stochastic motion models from single-particle trajectories presents significant challenges due to sampling limitations and inherent biological heterogeneity. Bayesian regression provides a powerful statistical framework for analyzing Mean Squared Displacement (MSD) data, enabling researchers to obtain optimal estimates of diffusion coefficients while rigorously quantifying uncertainty. This approach is particularly valuable in pharmaceutical development and biological research where understanding molecular mobility is crucial for drug mechanism studies and cellular process characterization.

Unlike traditional frequentist methods, Bayesian approaches formally incorporate prior knowledge and provide direct probability statements about parameters of interest, such as diffusion coefficients. This methodology allows researchers to continuously update their beliefs as new experimental data accumulates, creating a virtuous cycle of knowledge refinement in diffusion coefficients research. The Bayesian framework is especially suited for handling the complex error structures often encountered in MSD data analysis, including measurement errors, model inadequacies, and intrinsic stochasticity of biological systems.

Key Concepts and Theoretical Framework

Foundation of Bayesian Inference for MSD Data

The Bayesian approach to MSD-based analysis employs multiple-hypothesis testing of a general set of competing motion models based on particle mean-square displacements. This method automatically classifies particle motion while properly accounting for sampling limitations and correlated noise, appropriately penalizing model complexity according to Occam's Razor to avoid over-fitting. The core of Bayesian inference revolves around three fundamental components:

Prior Probability Distribution (P(θ)): Represents initial beliefs about parameters (e.g., diffusion coefficients) before observing current experimental data. Priors can be informative (based on previous studies or expert knowledge) or non-informative (minimally influential, allowing data to dominate conclusions) [30].

Likelihood (P(Data|θ)): Quantifies how probable the observed MSD data are, given particular values for the parameters θ. It represents the information contributed by the current experimental measurements [30].

Posterior Probability Distribution (P(θ|Data)): Represents updated beliefs about parameters after combining prior knowledge with experimental MSD data. This is calculated using Bayes' theorem: P(θ|Data) = [P(Data|θ) × P(θ)] / P(Data) [30].

Bayesian Workflow for MSD Analysis

The following diagram illustrates the systematic Bayesian framework for MSD data analysis:

Bayesian MSD Analysis Workflow

Research Reagent Solutions for MSD Experiments

Table 1: Essential research reagents and computational tools for Bayesian MSD analysis

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Bayesian Logistic Regression Model (BLRM) | Connects drug doses to side effect risks through logistic regression; starts with prior beliefs about dose safety and updates with new data [31]. | Phase I clinical trials testing new therapies for safety and dosing; adaptive trial designs that use all available information for dose adjustments. |

| Bayesian Age-Period-Cohort (BAPC) Models | Projects future disease burden trends using Bayesian framework with Integrated Nested Laplace Approximation (INLA) for efficient computation [32]. | Forecasting global burden of musculoskeletal disorders; modeling disease trends in postmenopausal women using Global Burden of Disease data. |

| Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) Algorithms | Enables sampling from posterior distributions without calculating marginal likelihoods directly; includes Metropolis-Hastings, Gibbs Sampling, and Hamiltonian Monte Carlo [30]. | Parameter estimation for complex diffusion models; uncertainty quantification in pharmaceutical process development and characterization. |

| Stan Modeling Platform | State-of-the-art platform for statistical modeling using Hamiltonian Monte Carlo (HMC) and No-U-Turn Sampler (NUTS) for efficient parameter space exploration [30]. | Building complex hierarchical models for MSD data; high-dimensional parameter estimation in biological diffusion studies. |

| Bayesian Finite Element Model Updating | Builds accurate numerical models for structural systems while quantifying associated model uncertainties in a Bayesian framework [33]. | Uncertainty quantification in model parameters; addressing modeling errors, parameter errors, and measurement errors in complex systems. |

| Power Prior Modeling | Formal methodology for incorporating historical data or external information into new trials using weighted prior distributions [34]. | Borrowing strength from previous MSD experiments; integrating historical control data in confirmatory clinical trials. |

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Model Selection and Validation Challenges

Table 2: Troubleshooting guide for Bayesian MSD analysis

| Problem | Potential Causes | Solutions | Preventive Measures |

|---|---|---|---|

| Poor MCMC Convergence | High autocorrelation between samples; inappropriate proposal distribution; insufficient burn-in period [30]. | Use Hamiltonian Monte Carlo (HMC) or NUTS algorithms; increase effective sample size; run multiple chains with different initial values. | Check trace plots and Gelman-Rubin statistic (R-hat); ensure R-hat < 1.05 for all parameters. |

| Overly Influential Priors | Too narrow prior distributions; strong subjective beliefs dominating likelihood [30]. | Conduct prior sensitivity analysis; use weakly informative priors; apply power priors with carefully chosen weights [34]. | Specify priors based on previous relevant studies; use domain expertise to justify prior choices. |

| Model Misspecification | Incorrect likelihood function; inappropriate motion model for biological process; missing covariates [35]. | Implement posterior predictive checks; compare multiple competing models using Bayes factors; use Bayesian model averaging. | Perform exploratory data analysis; consider multiple model structures (Brownian, anomalous diffusion, directed motion). |

| Inadequate Uncertainty Quantification | Ignoring model form errors; not accounting for measurement errors; underestimating parameter uncertainty [33]. | Use hierarchical Bayesian models; include error terms for measurement precision; employ Bayesian model updating techniques. | Classify uncertainty sources (aleatoric vs. epistemic); use robust likelihood formulations. |

| Computational Limitations | High-dimensional parameter spaces; complex likelihood functions; large datasets [36]. | Implement variational inference methods; use integrated nested Laplace approximations (INLA); employ surrogate modeling. | Start with simplified models; use efficient data structures; consider distributed computing approaches. |

Data Quality and Preprocessing Issues

Problem: Noisy MSD Trajectories Affecting Parameter Estimates

Experimental particle tracking data often contains substantial noise from various sources, including limited photon counts in fluorescence microscopy, thermal drift, and biological heterogeneity. This noise can significantly impact diffusion coefficient estimates and lead to misclassification of motion types.

Solution Protocol:

- Implement Bayesian Denoising: Apply Bayesian smoothing algorithms that incorporate prior knowledge about expected motion characteristics while accounting for measurement noise properties.

- Hierarchical Modeling: Use multi-level hierarchical models that separate measurement error from biological variability, allowing proper uncertainty propagation through the analysis.

- Model Comparison Framework: Employ systematic Bayesian approaches for multiple-hypothesis testing of competing motion models that automatically penalize model complexity to avoid overfitting [35].

- Validation with Simulations: Generate synthetic trajectories with known parameters using the posterior predictive distribution to verify that the analysis recovers true parameter values.

Experimental Protocols for Bayesian MSD Analysis

Comprehensive Protocol for Diffusion Coefficient Estimation

The following diagram outlines the complete experimental workflow for Bayesian MSD analysis:

MSD Experimental Analysis Pipeline

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Experimental Design and Data Collection

- Acquire particle tracking data with appropriate temporal and spatial resolution

- Record relevant experimental conditions (temperature, buffer composition, cell type)

- Collect sufficient trajectories for statistical power (typically 50-100 per condition)

Bayesian Model Specification

- Define prior distributions for diffusion coefficients based on literature or pilot studies

- Specify likelihood function accounting for measurement noise and motion type

- Consider multiple competing models (Brownian motion, anomalous diffusion, directed transport)

Computational Implementation

- Implement MCMC sampling using platforms like Stan, Nimble, or PyMC

- Run multiple chains with dispersed starting values

- Monitor convergence using Gelman-Rubin statistics (R-hat) and effective sample size

Posterior Analysis and Validation

- Extract posterior distributions for parameters of interest

- Calculate credible intervals for diffusion coefficients

- Perform posterior predictive checks to assess model adequacy

- Compare models using Bayes factors or information criteria

Protocol for Uncertainty Quantification in MSD Analysis

Objective: Properly characterize and quantify different sources of uncertainty in MSD-based diffusion coefficient estimates.

Procedure:

Classify Uncertainty Sources:

- Aleatoric uncertainty: Intrinsic randomness in particle motion

- Epistemic uncertainty: Limited knowledge about model parameters

- Model form uncertainty: Potential misspecification of physical models

- Measurement uncertainty: Experimental noise in trajectory tracking [33]

Implement Hierarchical Bayesian Models:

- Separate particle-level variability from population-level trends

- Include random effects for biological replicates

- Account for measurement precision using error-in-variables models

Bayesian Model Averaging:

- Compute posterior model probabilities for competing motion models

- Weight parameter estimates by model probabilities

- Obtain robust diffusion estimates that account for model uncertainty

Advanced Bayesian Techniques for MSD Data

Bayesian Model Selection Framework

The Bayesian approach provides a natural framework for comparing multiple competing models of particle motion. By computing posterior model probabilities, researchers can objectively select the simplest model that adequately explains the observed MSD data, following the principle of Occam's Razor. This systematic approach to multiple-hypothesis testing automatically penalizes model complexity to avoid overfitting, which is particularly important when analyzing complex motion patterns from single-particle trajectories [35].

The model evidence, also known as the marginal likelihood, serves as a key quantity for Bayesian model comparison. This integral averages the likelihood function over the prior distribution of parameters, automatically incorporating a penalty for model complexity. For MSD data analysis, this approach enables researchers to distinguish between different modes of motion, such as Brownian diffusion, confined motion, directed transport, or anomalous diffusion, based on probabilistic reasoning rather than arbitrary thresholding.

Incorporating Prior Knowledge in Pharmaceutical Applications

In drug development contexts, Bayesian methods formally incorporate existing knowledge into clinical trial design, analysis, and decision-making. The Bayesian Logistic Regression Model (BLRM) exemplifies this approach by combining prior beliefs about dose safety with real-time patient data to guide dose selection in Phase I trials [31]. This methodology creates a feedback loop where each patient's experience informs safer and more effective doses for subsequent participants, maximizing the efficiency of clinical development while maintaining patient safety.

The Bayesian framework is particularly valuable for dose escalation studies, where prior information about compound toxicity and pharmacokinetics can be formally incorporated using informative prior distributions. This approach allows for more efficient trial designs with smaller sample sizes while maintaining rigorous safety standards, addressing ethical imperatives to expose the fewest patients to potentially ineffective or unsafe treatment regimens [37].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: How does Bayesian analysis of MSD data differ from traditional least-squares fitting?

A1: Bayesian methods provide several advantages over traditional least-squares approaches:

- They quantify uncertainty in parameter estimates using credible intervals rather than just point estimates

- They formally incorporate prior knowledge through prior distributions

- They enable direct probability statements about parameters (e.g., "There is a 95% probability that the diffusion coefficient lies between X and Y")

- They automatically penalize model complexity through the marginal likelihood, reducing overfitting

- They handle hierarchical data structures naturally, accounting for both within-trajectory and between-trajectory variability [30] [35]

Q2: What are the computational requirements for Bayesian MSD analysis?

A2: Bayesian analysis typically requires more computational resources than traditional methods:

- MCMC sampling may require thousands of iterations for convergence

- Complex models with many parameters benefit from parallel computing

- Memory requirements scale with dataset size and model complexity

- Efficient implementations using platforms like Stan, Nimble, or PyMC can significantly reduce computation time

- For very large datasets, variational inference methods provide faster approximations to the posterior [30] [36]

Q3: How should I choose prior distributions for diffusion coefficient analysis?

A3: Prior selection should be guided by:

- Previous studies on similar systems

- Physical constraints (diffusion coefficients must be positive)

- Pilot experiments or preliminary data

- Sensitivity analysis to assess prior influence

- For exploratory analyses, use weakly informative priors that regularize estimates without strongly influencing results

- Document and justify all prior choices in your methodology [30] [34]

Q4: How can I validate my Bayesian MSD model?

A4: Comprehensive model validation includes:

- Posterior predictive checks: simulating new data from the posterior and comparing to observed data

- Cross-validation: assessing model performance on held-out data

- Convergence diagnostics: ensuring MCMC chains have properly explored the posterior

- Residual analysis: checking for systematic patterns in model errors

- Comparison with alternative models using Bayes factors or information criteria

- Recovery studies: testing whether the model can recover known parameters from simulated data [35] [33]

Q5: Can Bayesian methods handle heterogeneous populations in single-particle tracking?

A5: Yes, Bayesian methods are particularly well-suited for heterogeneous populations:

- Finite mixture models can identify subpopulations with different diffusion characteristics

- Hierarchical models naturally account for both within-group and between-group variability

- Nonparametric Bayesian methods automatically infer the number of subpopulations from the data

- Model comparison techniques help determine whether multiple populations are justified by the data

- These approaches provide a more realistic representation of biological systems where heterogeneity is common [35]

FAQs: Core Principles and Data Interpretation

Q1: What is the fundamental principle behind Taylor Dispersion Analysis? Taylor Dispersion Analysis (TDA) is a technique for determining the diffusion coefficients of molecules in solution. It is based on the dispersion of a narrow solute plug injected into a carrier solvent flowing under laminar (Poiseuille) conditions within a capillary. The parabolic velocity profile of the flow causes solute molecules at the center to move faster than those near the walls. This, combined with radial diffusion of the molecules, leads to the axial dispersion of the solute plug. The extent of this dispersion, which can be quantified by the temporal variance of the resulting concentration profile (Taylorgram), is inversely related to the solute's diffusion coefficient. From the diffusion coefficient (D), the hydrodynamic radius (Rh) can be calculated using the Stokes-Einstein equation [38] [39].

Q2: For a polydisperse sample, what does the calculated hydrodynamic radius represent? For a polydisperse sample or mixture, a single fit to the Taylorgram provides a weighted average diffusion coefficient, and thus a weighted average hydrodynamic radius. For mass-sensitive detectors (like UV/Vis absorbance), this average is a mass-based average [39]. Studies have shown that for a monomodal sample with relatively low polydispersity, this average is typically very close to the weight-average diffusion coefficient (Dw). However, for highly polydisperse or bimodal samples, the value can differ significantly from other averages, such as the z-average obtained from Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) [40].

Q3: What are the key advantages of TDA compared to other sizing techniques? TDA offers several distinct advantages [39] [41]:

- Absence of Calibration: The method is absolute and does not require calibration standards for size determination.

- Insensitivity to Dust: Measurements are performed in a capillary, making the technique insensitive to dust particles; sample filtration is typically not required.

- Minimal Sample Consumption: Very small sample volumes (a few nanoliters) are injected.

- Wide Size Range: Effective for hydrodynamic radii from approximately 0.2 nm to 300 nm.

- No Bias Towards Large Species: Provides a mass-based distribution, avoiding the intensity-based bias of DLS which can overemphasize large aggregates.

- Fast Analysis: Experiments are typically rapid.

Q4: How does TDA handle and quantify sample aggregation? In a monodisperse sample, the Taylorgram is a symmetrical Gaussian peak. The presence of aggregates leads to a deviation from this Gaussian shape because the Taylorgram becomes a sum of the Gaussian profiles of the individual species (e.g., monomer, dimer, aggregate). The broader peak width indicates the presence of larger, slower-diffusing species [38] [39]. Advanced data processing methods, such as Constrained Regularized Linear Inversion (CRLI), can be used to deconvolute the experimental Taylorgram and extract the probability density function of the diffusion coefficients, thereby quantifying the relative proportions of the different populations in the sample [39].

Troubleshooting Guides