A Practical Guide to Setting Up Molecular Dynamics Simulations for Cyclic Peptides

This article provides a comprehensive, step-by-step guide for researchers and drug development professionals to set up and run molecular dynamics (MD) simulations for cyclic peptides.

A Practical Guide to Setting Up Molecular Dynamics Simulations for Cyclic Peptides

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive, step-by-step guide for researchers and drug development professionals to set up and run molecular dynamics (MD) simulations for cyclic peptides. Covering everything from fundamental concepts and system preparation with explicit solvent to advanced enhanced sampling techniques and result validation, this guide addresses key challenges in simulating these complex molecules. Readers will learn how to select appropriate force fields, implement methods like GaMD and REMD for efficient conformational sampling, troubleshoot common issues, and correlate simulation data with experimental observables like membrane permeability and LogD to advance therapeutic design.

Understanding Cyclic Peptides and Why They Challenge Conventional MD

The Unique Conformational Landscape of Cyclic Peptides

Cyclic peptides are an emerging therapeutic modality that combine the advantages of small molecules and biologics. Their conformational rigidity, target specificity, protease resistance, and potential for membrane permeability make them attractive for drug development, particularly for disrupting intracellular protein-protein interactions [1]. However, their circular structure creates a unique conformational landscape that is challenging to characterize and predict. Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations have become an indispensable tool for studying these landscapes in solution, providing atomic-level insights that complement experimental data [2] [3]. This Application Note provides a structured framework for employing MD simulations in cyclic peptide research, detailing force field selection, enhanced sampling protocols, and analytical approaches to accurately capture their conformational ensembles.

Force Field Performance and Selection

The accuracy of MD simulations is critically dependent on the force field. A recent benchmark study evaluated seven state-of-the-art force fields against NMR data for 12 cyclic peptides (6 pentapeptides, 4 hexapeptides, and 2 heptapeptides) [3]. The performance was measured by the ability of simulations to recapitulate experimental NMR-derived structural information.

Table 1: Performance of Force Fields for Cyclic Peptide Simulations

| Force Field + Solvent Model | Number of Cyclic Peptides with NMR Data Recapitulated | Performance Rating |

|---|---|---|

| RSFF2 + TIP3P | 10/12 | Excellent |

| RSFF2C + TIP3P | 10/12 | Excellent |

| Amber14SB + TIP3P | 10/12 | Excellent |

| Amber19SB + OPC | 8/12 | Good |

| OPLS-AA/M + TIP4P | 5/12 | Moderate |

| Amber03 + TIP3P | 5/12 | Moderate |

| Amber14SBonlysc + GB-neck2 (Implicit) | 5/12 | Moderate |

The data indicates that RSFF2+TIP3P, RSFF2C+TIP3P, and Amber14SB+TIP3P demonstrate the best and similar performance, successfully reproducing NMR data for 10 out of 12 benchmark peptides [3]. The use of explicit solvent models is generally recommended, as implicit solvent models (e.g., GB-neck2) showed inferior performance in this assessment.

Experimental Protocols for MD Simulation

System Preparation and Equilibration

A robust protocol for initializing cyclic peptide systems is crucial for simulation stability and convergence [3].

- Initial Structure Construction: Build a linear all-glycine peptide with random (ϕ, ψ) dihedrals using molecular visualization software (e.g., Chimera). Perform head-to-tail cyclization between the N- and C-termini, followed by energy minimization. Finally, mutate the glycine residues to the desired sequence.

- Convergence Verification: Generate at least two different initial conformations (S1 and S2) with a backbone RMSD ≥ 1.2 Å. Perform parallel simulations starting from these structures to monitor convergence.

- Solvation and Neutralization: Solvate the peptide in a box of explicit water molecules (e.g., TIP3P), maintaining a minimum distance of 1.0 nm between the peptide and the box edge. Add counterions (Na⺠or Clâ») to neutralize the system charge.

- Energy Minimization and Equilibration:

- Minimize the energy of the solvated system using the steepest descent algorithm.

- Equilibrate in the NVT ensemble for 50 ps, restraining heavy atoms of the peptide with a force constant of 1000 kJ·molâ»Â¹Â·nmâ»Â².

- Equilibrate in the NPT ensemble for 50 ps with the same restraints.

- Perform subsequent NVT and NPT simulations for 100 ps each without any restraints.

Enhanced Sampling with Bias-Exchange Metadynamics (BE-META)

For efficient sampling of cyclic peptide conformational space, Bias-Exchange Metadynamics (BE-META) is highly effective [3].

- Collective Variables (CVs): For a cyclic peptide of n residues, define 2n biased replicas. Each replica biases a pair of dihedral angles: n replicas bias the (ϕ~i~, ψ~i~) pairs, and the other n replicas bias the (ψ~i~, ϕ~i+1~) pairs.

- Production Simulation: Run the BE-META production simulation in the NPT ensemble. Apply a LINCS constraint algorithm only to bonds involving hydrogen atoms. Use a time step of 2 fs.

- Analysis: The resulting trajectories can be used to reweight and construct the free-energy landscape of the peptide, providing populations for various conformations.

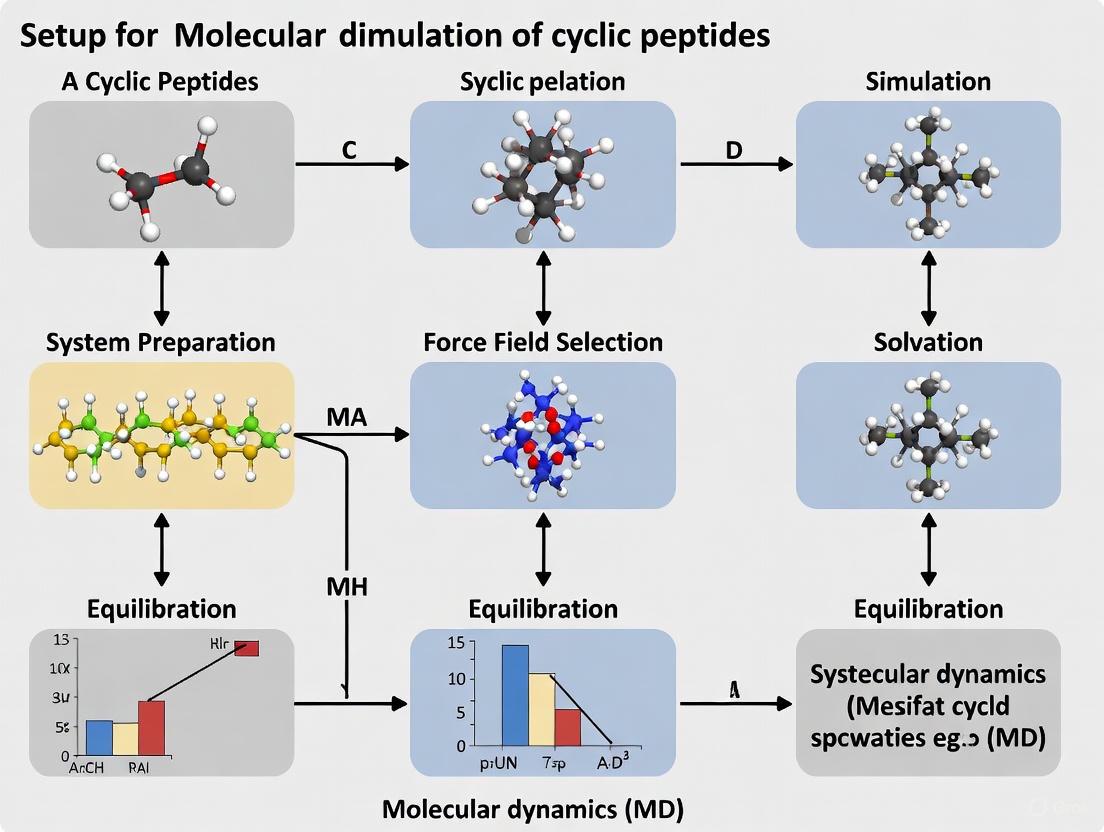

Figure 1: System setup and equilibration workflow.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Software and Force Fields for Cyclic Peptide Simulations

| Tool/Reagent | Type | Primary Function | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| GROMACS [2] [3] | Software | High-performance MD simulation engine. | Highly optimized for explicit solvent simulations on CPUs and GPUs. |

| AMBER [3] | Software | Suite for MD simulations and analysis. | Includes tools for system building (tleap) and analysis (cpptraj, ptraj). |

| PLUMED [3] | Plugin | Enhanced sampling and free-energy calculations. | Essential for implementing BE-META; interfaces with GROMACS/AMBER. |

| RSFF2 [2] [3] | Force Field | Residue-specific force field for peptides. | Top performer for cyclic peptide conformational ensembles. |

| Amber14SB [3] | Force Field | General protein force field. | Robust and well-tested; excellent performance for cyclic peptides. |

| Chimera [3] | Software | Molecular visualization and analysis. | Used for initial model building, cyclization, and visualization. |

| BE-META [3] | Method | Enhanced sampling algorithm. | Efficiently explores conformational space of cyclic peptides. |

| REMD [2] | Method | Enhanced sampling algorithm. | Useful for overcoming energy barriers; implemented in GROMACS. |

| 3-Chloro-5-(p-tolyl)-1,2,4-triazine | 3-Chloro-5-(p-tolyl)-1,2,4-triazine|CAS 1368414-41-8 | 3-Chloro-5-(p-tolyl)-1,2,4-triazine is a key building block for synthesizing diverse 1,2,4-triazine derivatives. This reagent is For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. | Bench Chemicals |

| 4-Methyl-5-nitropicolinaldehyde | 4-Methyl-5-nitropicolinaldehyde, CAS:5832-38-2, MF:C7H6N2O3, MW:166.13 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Integrating Simulation with Broader Research Goals

Connection to de novo Design

Accurate MD simulations are a critical validation step in de novo cyclic peptide design pipelines. Physics-based design tools, such as CyclicChamp, can generate candidate peptides with 15–24 residues [1]. Subsequent microsecond-length MD simulations are used to assess the kinetic and thermodynamic stability of these designs, identifying promising candidates for experimental testing [1]. Furthermore, MD-generated structural ensembles can be used to train machine learning models like StrEAMM, which can then predict ensembles for new sequences in seconds instead of days [4].

Machine Learning and Deep Learning Approaches

Deep learning methods like AfCycDesign have been adapted from AlphaFold2 for cyclic peptide structure prediction and design [5]. These tools can rapidly generate and score large libraries of cyclic peptide scaffolds. However, they are currently limited to canonical L-amino acids and their accuracy may be constrained by the limited training data available for macrocycles [1] [5]. Therefore, MD simulations remain the gold standard for modeling peptides containing D-amino acids or non-canonical residues and for predicting complete structural ensembles, including for poorly-structured, "chameleonic" peptides that may be crucial for membrane permeability [4].

Figure 2: MD simulation role in cyclic peptide research.

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation has become an indispensable tool for studying cyclic peptides, which are promising therapeutic candidates due to their ability to modulate protein-protein interactions. However, their computational characterization faces three fundamental challenges: ring strain that restricts conformational sampling, the existence of multiple solution conformations, and significant solvent interactions that dictate structural preferences. This Application Note details protocols and solutions for addressing these challenges in MD simulations, providing researchers with practical methodologies for obtaining accurate solution structural ensembles.

Key Challenges in Cyclic Peptide Simulations

Ring Strain and Conformational Sampling

The closed topology of cyclic peptides introduces significant ring strain that creates high energy barriers between conformations. This leads to several computational challenges:

- Slow dynamics with extended correlation times compared to linear peptides

- Kinetic trapping in local energy minima during simulation

- Insufficient sampling with conventional MD (cMD) on typical timescales

These limitations necessitate enhanced sampling methods to achieve adequate conformational exploration [6]. Table 1 compares the performance of various sampling methods for cyclic peptide systems.

Table 1: Performance of Enhanced Sampling Methods for Cyclic Peptides

| System | Method | # Replicas | Length/Replica | Convergence Assessment | Converged? | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cyclo-(PSIDV) | cMD | 1 | 1 µs | N/A | No | [6] |

| Cyclo-(PSIDV) | aMD | 1 | 1 µs | N/A | N/A | [6] |

| 20 cyclic peptides | REMD | 24-32 | 100-200 ns | Block analysis | Yes | [6] |

| Cyclo-(YNPFEEGG) | REMD | 51-59 | 300 ns | Independent trajectories | Mixed | [6] |

| Cyclo-(YNPFEEGG) | BE-META | 18 | 300 ns | Independent trajectories | Yes | [6] |

| Cyclosporin A | CoCo-MD | 10 | 2 ns | Ensemble diversity | 9822 confs | [6] |

Multiple Conformational States

Most cyclic peptides exist as ensembles of multiple conformations in solution rather than single structures. Experimental characterization, particularly by NMR spectroscopy, is challenging because it provides time- and ensemble-averaged data that are difficult to deconvolute [6]. This multiplicity has functional significance, as chameleonic properties may enable membrane permeability by adopting different conformations in various environments [7]. Computational methods must therefore capture complete structural ensembles rather than identifying single low-energy states.

Solvent Interactions

Explicit solvent modeling is particularly important for cyclic peptides due to their:

- High solvent exposure of backbone polar groups

- Bridged water molecules that can be caged within peptide structures

- Direct hydrogen bonding with solvent that dictates conformational preferences

Implicit solvent models often fail to capture these specific peptide-water interactions, leading to inaccurate structural predictions [6].

Computational Protocols

Enhanced Sampling Methods

Replica Exchange Molecular Dynamics (REMD)

REMD is particularly effective for cyclic peptides as it facilitates escape from local minima. The following protocol implements REMD using GROMACS:

REMD Workflow for Cyclic Peptides

Key Parameters:

- Temperature distribution: Use 24-59 replicas exponentially spaced between 300-500K

- Exchange attempts: Every 1-2 ps

- Simulation length: 100-300 ns per replica

- Force field: AMBERff99SB with RSFF2 modification or CHARMM36 with CMAP corrections [2] [6]

Convergence Assessment:

- Perform block analysis of backbone RMSD

- Compare two independent simulations

- Monitor replica exchange rates (target: 20-30%)

- Calculate ensemble diversity metrics [6]

Bias-Exchange Metadynamics (BE-META)

BE-META accelerates transitions along specific collective variables (CVs) relevant to cyclic peptides:

Protocol:

- Define CVs: Backbone dihedrals, radius of gyration, principal components

- Set bias parameters: Height=0.1-0.5 kJ/mol, width=CV fluctuations, deposition=1 ps

- Exchange attempts: Every 500 steps between CVs

- Simulation length: 100-250 ns per replica with 12-18 replicas [6]

Convergence: Monitor CV distributions and free energy surface evolution

Force Field Selection and Modification

Standard protein force fields require modifications for cyclic peptides:

Table 2: Force Field Recommendations for Cyclic Peptides

| Force Field | Modification | Advantages | Limitations | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMBERff99SB | RSFF2 (Residue-specific) | Improved backbone dihedral sampling | Parameterization required | [2] [6] |

| OPLS-AA/L | RSFF1 | Better side-chain rotamers | Limited testing | [2] |

| CHARMM36 | CMAP | Good secondary structure balance | May over-stabilize helices | [6] |

| General Amber | GAFF | Compatible with non-natural amino acids | Limited peptide validation | [6] |

Residue-Specific Force Fields (RSFF) incorporate amino acid-specific corrections derived from protein coil libraries, significantly improving conformational sampling for cyclic peptides [2].

Trajectory Analysis and Validation

Clustering and Ensemble Characterization

Ensemble Analysis Workflow

Clustering Protocol:

- Feature selection: Backbone dihedrals or heavy atom coordinates

- Dimensionality reduction: PCA or t-SNE for visualization

- Clustering algorithm: Density-based (DBSCAN) or k-means++

- Cluster validation: Silhouette score, convergence between replicates

RING-PyMOL Integration: Use RING-PyMOL plugin to analyze residue interaction networks across clusters and identify correlated contacts that explain structural heterogeneity [8].

Experimental Validation

Compare computational ensembles with experimental data:

- NMR chemical shifts: Calculate using SHIFTX2 or SPARTA+

- J-couplings: Compare^3JHN-HA with experimental values

- NOEs: Calculate expected NOE patterns from ensembles

- RMSD: Target ≤1.5 Å for well-structured peptides, higher for flexible systems

Advanced Applications

Machine Learning Accelerated Predictions

The StrEAMM method combines MD simulations with machine learning to predict structural ensembles in seconds rather than days of computation:

Workflow:

- Run MD simulations for basis-set cyclic peptides (100-500 sequences)

- Train neural networks on (sequence → ensemble) mapping

- Predict ensembles for new sequences in seconds [7]

Performance: Achieves MD-quality predictions with seven-order-of-magnitude speed improvement while maintaining accuracy [7].

Designing Larger Cyclic Peptides

For cyclic peptides beyond 15 residues, traditional sampling becomes prohibitive. The CyclicChamp pipeline addresses this challenge:

Key Innovations:

- Converts cyclic constraint into error function for optimization

- Uses simulated annealing to search low-energy backbone space

- Enables design of 15-24 residue cyclic peptides [1]

Validation: Microsecond MD simulations and replica exchange MD confirm kinetic and thermodynamic stability of designs [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Cyclic Peptide Research

| Tool | Application | Key Features | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| GROMACS | MD Simulation | REMD implementation, GPU acceleration | [2] [9] |

| RING-PyMOL | Trajectory Analysis | Residue interaction networks, clustering | [8] |

| StrEAMM | Ensemble Prediction | ML-accelerated ensemble prediction | [7] |

| CyclicChamp | Peptide Design | Heuristic search for large macrocycles | [1] |

| Rosetta | Peptide Design | GenKIC cyclization, sequence design | [6] [1] |

| CPMP | Permeability Prediction | MAT-based membrane permeability | [10] |

| 4-(Methylthio)phenylacetyl chloride | 4-(Methylthio)phenylacetyl Chloride|RUO|Supplier | 4-(Methylthio)phenylacetyl chloride is a synthetic building block for research. This product is for Research Use Only and is not intended for personal use. | Bench Chemicals |

| N'-(4-Aminophenyl)benzohydrazide | N'-(4-Aminophenyl)benzohydrazide, CAS:63402-27-7, MF:C13H13N3O, MW:227.26 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Accurate simulation of cyclic peptides requires addressing ring strain with enhanced sampling methods, capturing multiple conformational states through ensemble approaches, and explicitly modeling solvent interactions. The protocols described herein provide researchers with robust methodologies for overcoming these challenges and obtaining biologically relevant structural ensembles. As computational power increases and methods like machine learning acceleration mature, MD simulations will play an increasingly central role in the rational design of cyclic peptide therapeutics.

Why Explicit Solvent Models are Non-Negotiable

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation has become an indispensable tool for studying the structure, dynamics, and function of cyclic peptides, which are emerging as promising therapeutic candidates due to their ability to target challenging protein interfaces. The accuracy of these simulations critically depends on how molecular interactions are modeled, with solvent representation being perhaps the most important factor. While implicit solvent models offer computational efficiency by approximating water as a continuous dielectric medium, explicit solvent models treat water molecules as individual entities, capturing specific and directional peptide-water interactions at the molecular level. For cyclic peptides, whose conformational behavior and biological activity are often dictated by a delicate balance of intramolecular and solvent-mediated forces, explicit solvent modeling is not merely an option but a fundamental requirement for obtaining physiologically relevant results.

The non-negotiable nature of explicit solvents stems from several critical factors. Cyclic peptides frequently display many solvent-exposed backbone carbonyl and amide groups, and their structural ensembles are strongly influenced by peptide-water interactions that must be described at the molecular level [4]. Water molecules can form bridging hydrogen bonds between peptide atoms, become caged within peptide structures, and create microenvironments that stabilize specific conformations—all phenomena that implicit models cannot capture. Furthermore, the chameleonic properties of some cyclic peptides, where their ability to adopt multiple conformations is essential for membrane permeability and biological function, are intimately tied to solvent interactions [4]. This application note establishes why explicit solvent models are essential for meaningful MD simulations of cyclic peptides and provides practical protocols for their implementation.

Quantitative Comparison: Explicit vs. Implicit Solvent Models

Table 1: Key Differences Between Explicit and Implicit Solvent Models for Cyclic Peptide Simulations

| Feature | Explicit Solvent | Implicit Solvent (GB/SA) |

|---|---|---|

| Solvent Representation | Individual water molecules (e.g., TIP3P, TIP4P) [11] | Continuum dielectric medium [11] |

| Specific Hydrogen Bonding | Directly captures specific peptide-water H-bonds [4] | Approximated via effective dielectric response |

| Solvent Caging/Bridging | Models caged water molecules and water bridges [4] | Cannot capture discrete water mediation |

| Conformational Sampling | Essential for accurate ensembles of poorly-structured peptides [4] | Often fails for flexible, solvent-exposed peptides |

| Computational Cost | High (~70-90% of computation on water) [11] | Low (enables faster sampling) |

| Recommended Use Case | Final production simulations and validation [2] [11] | Initial conformational sampling or screening |

The quantitative requirements for achieving reliable statistics in explicit solvent simulations further underscore their sophisticated treatment of solvent effects. For instance, reproducing Raman Optical Activity (ROA) spectra of a cyclic dipeptide required averaging over a substantial number of independent MD snapshots—approximately 40 snapshots for middle-frequency regions and more than 120 snapshots for the highly solvent-sensitive amide I band region [12]. This demonstrates how explicit solvent models capture the dynamic interplay between peptide conformation and aqueous environment, which is particularly crucial for spectroscopic properties and solvent-exposed motifs.

Practical Consequences: How Solvent Models Impact Research Outcomes

Conformational Sampling and Population Distributions

The choice of solvent model directly influences the predicted structural ensembles of cyclic peptides. Well-structured cyclic peptides that predominantly populate a single conformation may sometimes be studied with simpler models, but the majority of cyclic peptides adopt multiple conformations in solution [4]. For these "poorly-structured" or "chameleonic" peptides, explicit solvent is essential because their functional properties often depend on the equilibrium between different conformations. The ability to adopt multiple conformations can be essential for biological properties, including the high cell membrane permeability observed in some therapeutic cyclic peptides [4]. Implicit models typically fail to predict the correct populations of these conformational states because they miss the discrete, directional nature of water-peptide interactions that tip the energetic balance between similar structures.

Binding Mechanisms and Molecular Recognition

Explicit solvent simulations have revealed how solvent interactions dictate binding mechanisms. In studies of cyclic β-hairpin ligands designed to disrupt the MDM2-p53 interaction, massively parallel explicit-solvent MD simulations revealed a conformational selection mechanism where the solution-state preorganization of the ligands determined their binding affinities [13]. Markov State Model analysis of over 3 milliseconds of aggregate trajectory data showed a striking relationship between the relative preorganization of each ligand in solution and its affinity for MDM2, with entropy loss upon binding being the main factor influencing affinity [13]. Such insights would be impossible with implicit solvent models, which cannot capture the detailed dehydration processes and water-mediated interactions that accompany binding.

Force Field Dependencies and Sampling Limitations

It is important to note that explicit solvent simulations still face challenges related to force field accuracy and sampling completeness. Protein force fields contain parameters for bonded interactions (bond lengths, angles, dihedral angles) and non-bonded interactions (van der Waals and electrostatics), and recent improvements have focused particularly on refining backbone and side-chain dihedral-angle terms to fit quantum mechanics calculations or NMR observables [11]. These force fields are continuously being improved (AMBER, CHARMM, OPLS-AA), and their performance is best evaluated with explicit solvents [11]. Enhanced sampling methods like replica-exchange MD (REMD) have become popular for cyclic peptide simulations because they facilitate better conformational exploration [2], but they remain computationally demanding when combined with explicit solvent models.

Experimental Protocols: Implementing Explicit Solvent Simulations

Protocol 1: Standard Explicit Solvent MD for Cyclic Peptides

Table 2: System Setup and Simulation Parameters for Explicit Solvent MD

| Parameter | Specification | Purpose/Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Force Field | AMBERff99SB, CHARMM36, OPLS-AA with recent dihedral corrections [11] | Balanced protein/water interactions |

| Water Model | TIP3P or TIP4P [11] | Compatible with force field; reproduces water properties |

| System Setup | Solvate in truncated octahedron or rectangular box with ≥10 Å padding from solute | Minimizes artificial periodicity effects |

| Neutralization | Add counterions (Na+/Cl-) to physiological concentration (0.15 M) | Models physiological ionic strength |

| Energy Minimization | Steepest descent followed by conjugate gradient | Removes bad contacts and high-energy configurations |

| Equilibration | Gradual warming from 0 K to target temperature (e.g., 300 K) with position restraints on solute | Allows solvent to relax around peptide |

| Production MD | 50-500 ns (system-dependent) with 2-fs time step | Generates trajectory for analysis |

This protocol provides a foundation for routine explicit solvent simulations of cyclic peptides. After system setup, energy minimization should be performed until the maximum force is below a reasonable threshold (typically 1000 kJ/mol/nm). Equilibration then proceeds in stages: first with strong position restraints on the peptide while the solvent relaxes, then with gradually reduced restraints. During production simulation, temperature and pressure coupling are maintained using algorithms like Nosé-Hoover thermostat and Parrinello-Rahman barostat to simulate NPT conditions. Long-range electrostatics are typically handled with Particle Mesh Ewald methods, which are essential for accurate forces in periodic systems.

Protocol 2: Enhanced Sampling with Replica-Exchange MD (REMD)

For more challenging cyclic peptides with complex energy landscapes, enhanced sampling is necessary. Replica-exchange molecular dynamics (REMD) has become the most popular enhanced sampling method for ab initio folding studies because it efficiently utilizes parallel computing resources [11]. The following protocol is adapted from Gromacs implementations for cyclic peptides [2]:

- System Preparation: Prepare the explicit solvent system as in Protocol 1, ensuring identical configuration across all replicas.

- Temperature Selection: Choose a temperature distribution (typically 8-64 replicas) spanning from the target temperature (e.g., 300 K) to a sufficiently high temperature (e.g., 500 K) where conformational transitions occur rapidly. Temperature spacing should provide ~20% exchange probability between adjacent replicas.

- Parallel Equilibration: Equilibrate each replica independently at its assigned temperature using the same procedure as Protocol 1.

- REMD Production: Run parallel MD simulations with attempted exchanges between neighboring temperatures at regular intervals (e.g., every 1-2 ps). Exchanges are accepted or rejected based on the Metropolis criterion to maintain detailed balance.

- Trajectory Analysis: Recombine trajectories using weighted histogram analysis method (WHAM) or similar approaches to compute thermodynamic properties at the temperature of interest.

REMD is particularly valuable for predicting complete structural ensembles of cyclic peptides, including both well-structured and poorly-structured variants [4]. This method allows conformations to overcome energy barriers at high temperatures while maintaining proper Boltzmann sampling at the target temperature through the exchange process.

Visualization of Methodologies and Workflows

Table 3: Key Software Tools for Explicit Solvent Cyclic Peptide Simulations

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function | Application in Cyclic Peptide Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| GROMACS [2] [11] | MD Software | High-performance MD simulations | Production MD and REMD simulations with explicit solvent |

| AMBER [11] | MD Software | Biomolecular simulation suite | Force field development and explicit solvent MD |

| CHARMM [11] | MD Software | Biomolecular simulation | All-atom explicit solvent simulations |

| StrEAMM [4] | Machine Learning | Structural ensemble prediction | Predicts MD-quality ensembles without new simulations |

| CPMP [10] | Deep Learning | Membrane permeability prediction | Predicts permeability from structure using MAT framework |

| OpenMM [11] | MD Library | GPU-accelerated simulations | High-throughput explicit solvent simulations |

Beyond the core simulation software, several specialized computational tools have emerged that leverage explicit solvent simulations for cyclic peptide research. The StrEAMM (Structural Ensembles Achieved by Molecular Dynamics and Machine Learning) method uses MD simulation results to train machine learning models that can predict structural ensembles for new cyclic peptide sequences in seconds rather than days [4]. Similarly, the CPMP (Cyclic Peptide Membrane Permeability) model employs a Molecular Attention Transformer based on molecular graph structures and atomic relationships that were initially informed by explicit solvent understanding [10]. These tools represent the next generation of computational methods that build upon insights gained from explicit solvent simulations.

The evidence from multiple research domains consistently demonstrates that explicit solvent models are non-negotiable for meaningful MD simulations of cyclic peptides. While implicit solvents retain value for specific applications like initial conformational sampling or high-throughput screening, they cannot capture the essential physics of peptide-water interactions that govern cyclic peptide behavior. The directional hydrogen bonding, discrete water bridging, and solvent caging effects that explicit models provide are indispensable for predicting accurate structural ensembles, binding mechanisms, and spectroscopic properties.

As computational resources continue to grow and methods like machine learning accelerate structural prediction, the role of explicit solvent simulations will only become more central. They provide the fundamental reference data for training faster predictive models and the validation benchmark for new computational approaches. For researchers pursuing cyclic peptide therapeutics, investing the computational resources in explicit solvent simulations is not merely a technical choice but a scientific necessity for obtaining reliable, physiologically relevant results that can guide experimental design and decision-making.

Relating Solution Ensembles to Biological Function and Permeability

For cyclic peptides, which are promising therapeutic candidates for modulating intracellular protein-protein interactions, the dynamic ensemble of conformations they adopt in solution (their solution ensemble) is a critical determinant of their biological function and membrane permeability [6]. Unlike small molecules or structured proteins, cyclic peptides are highly flexible, frequently populating multiple conformational states in equilibrium. The composition of this ensemble dictates both their ability to bind biological targets with high affinity and specificity, and their capacity to passively cross cell membranes to reach intracellular sites of action [14] [15]. A profound challenge in de novo cyclic peptide design is the inability of traditional structural biology techniques, such as X-ray crystallography and standard NMR spectroscopy, to adequately resolve these multiple, interconverting solution states [6]. Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, particularly when enhanced sampling methods are employed, have emerged as a powerful computational microscope, capable of characterizing these elusive conformational landscapes and relating them directly to experimental observables like permeability coefficients and binding affinities [6] [11]. This application note details protocols for applying MD simulations to uncover the links between cyclic peptide sequence, solution ensemble, and biological activity, providing a foundation for their rational design.

The Critical Link Between Conformational Dynamics and Permeability

The conformational plasticity of cyclic peptides is central to the hypothesized mechanism of passive membrane permeability. Many cyclic peptides exhibit chameleonic properties, allowing them to modulate their three-dimensional structure to adapt to different environments [15]. A peptide may preferentially adopt a more polar, solvent-exposed conformation in an aqueous extracellular environment, while shifting its ensemble toward compact, hydrophobic states with internal hydrogen bonds (H-bonds) to minimize the exposure of polar backbone groups within the lipid bilayer [14]. The ability to sample these permeable-active conformations, even transiently in water, is a key prerequisite for membrane crossing.

Molecular dynamics simulations provide the means to quantify these features by sampling the free energy landscape of the peptide. Key metrics that can be derived from simulation trajectories and correlated with experimental permeability include:

- Solvent-Accessible Surface Area (SASA): A measure of molecular exposure, particularly for polar and non-polar groups.

- Number of Internal Hydrogen Bonds: A hallmark of compact, closed conformations that shield polar atoms.

- Radius of Hydration (Râ‚€): An indicator of molecular volume and compactness.

- Principal Component Analysis (PCA) Modes: The dominant collective motions that define the transitions between conformational states.

The free energy difference of a peptide between aqueous and membrane-mimetic environments (e.g., octanol) serves as a computational proxy for its measured permeability, as demonstrated in GaMD studies of lariat peptides [14].

Computational Methods for Sampling Cyclic Peptide Ensembles

Accurately capturing the conformational ensemble of a cyclic peptide requires overcoming significant energy barriers associated with ring strain and cis-trans peptide bond isomerization. Conventional MD (cMD) simulations often fail to adequately explore this complex landscape within practical timeframes. The table below summarizes enhanced sampling methods particularly suited for cyclic peptide studies.

Table 1: Enhanced Sampling Methods for Cyclic Peptide Simulations

| Method | Key Principle | Advantages for Cyclic Peptides | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Replica-Exchange MD (REMD) [6] [2] | Multiple copies (replicas) run at different temperatures; periodic swapping allows escape from local minima. | Excellent for broad exploration of conformational space; efficient on parallel architectures. | Resource-intensive (many replicas); choice of temperature range is critical. |

| Gaussian Accelerated MD (GaMD) [14] | Adds a harmonic boost potential to the system's energy landscape, smoothing energy barriers. | No need to predefine reaction coordinates; provides a un-biased potential for reweighting. | Requires careful tuning of boost potential parameters for accurate reweighting. |

| Bias-Exchange Metadynamics (BE-META) [6] | History-dependent bias potentials are added along multiple collective variables (CVs) to discourage revisiting states. | Efficiently samples complex transitions dependent on multiple variables (e.g., multiple torsions). | Selection of optimal CVs requires prior knowledge of the system. |

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for connecting simulation methodologies with the analysis of solution ensembles and their functional outcomes.

Diagram 1: Workflow for connecting simulation, ensemble analysis, and functional properties.

Force Field and Solvation Considerations

The choice of force field and solvent model is paramount for generating physically meaningful ensembles. Best practices include:

- Force Fields: Modern, refined protein force fields such as CHARMM36, AMBER ff99SB-ILDN, and OPLS-AA are recommended, with some studies suggesting residue-specific modifications (RSFF) can improve accuracy for peptides [2] [16] [11].

- Solvent Model: Explicit solvent models (e.g., TIP3P, TIP4P) are strongly preferred over implicit models for cyclic peptides. Explicit water is crucial for modeling specific water-peptide interactions, such as bridging hydrogen bonds or water molecules caged within the peptide ring, which can significantly stabilize certain conformations [6] [11].

Protocol: GaMD for Permeability Prediction

This protocol outlines the use of Gaussian Accelerated MD (GaMD) to sample cyclic peptide conformations in different solvents to predict membrane permeability, based on the methodology of Kelly et al. and subsequent GaMD studies [14].

System Setup

- Initial Structure Generation: Generate an initial 3D structure of the cyclic peptide. For lariat or other non-standard peptides, ensure force field parameters for unusual linkages (e.g., depsipeptide bonds) are properly parameterized using tools like the FFTK plugin in VMD.

- Solvation: Solvate the peptide in two separate systems:

- Aqueous Environment: Use a periodic water box (e.g., TIP3P) with a minimum 10 Ã… buffer between the peptide and box edge.

- Membrane-Mimetic Environment: Use a periodic box of octanol (e.g., using the CGENFF force field) [14].

- Energy Minimization and Equilibration:

- Minimize the system for 5,000-7,500 steps to remove steric clashes.

- Equilibrate in the NPT ensemble (1 atm, 310 K) for at least 100 ps to stabilize system density.

GaMD Production Simulation

- Conventional MD Run: First, run a short (e.g., 10 ns) conventional MD simulation in the NVT ensemble (310 K). This data is used by the GaMD algorithm to calculate the statistics of the potential energy for applying the boost potential.

- GaMD Parameters: Configure the GaMD simulation for "dual-boost" mode, applying boost potentials to both the total potential energy and the dihedral energy. The threshold energy (E) and harmonic force constant (k) should be set according to the GaMD implementation guidelines (e.g., in NAMD 2.14+) to ensure a Gaussian distribution of the boost potential for accurate reweighting [14].

- Production Sampling: Run the GaMD production simulation for a sufficient duration (e.g., 40-250 ns per system, as used in recent studies [14]) to achieve convergence in the sampled conformational space.

Trajectory Analysis and Permeability Estimation

- Cluster Analysis: Use clustering algorithms (e.g., K-means) on the backbone heavy atom RMSD to identify the predominant conformational families in each solvent [14].

- Calculate Key Metrics: For each cluster, compute:

- Backbone and total SASA.

- Number of internal hydrogen bonds.

- Radius of hydration (Râ‚€), found by fitting the average cluster conformation to the smallest enclosing sphere.

- Construct Free Energy Landscapes: Reweight the simulation data using the GaMD boost potential to compute the potential of mean force (PMF) along relevant collective variables, such as principal components or RMSD.

- Estimate Permeability: The permeability (P) can be estimated using an adapted form of the Stokes-Einstein and solubility-diffusion equations, integrating the PMF and diffusion coefficient across the solvent boundary [14]:

1/P = R = ∫ [exp(βW(z)) / D(z)] dzwhere R is resistivity, β is 1/KBT, W(z) is the PMF, and D(z) is the diffusion coefficient.

Protocol: Machine Learning for Permeability Prediction

As a complementary high-throughput approach, machine learning (ML) models can predict permeability directly from peptide sequence or structure. The following table summarizes the performance of top-performing ML models based on a recent benchmark [15].

Table 2: Performance of Selected ML Models on Cyclic Peptide Permeability Prediction (PAMPA Assay Data)

| Model | Molecular Representation | Key Performance (Regression R² on Test Set) | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| DMPNN [15] | Molecular Graph | ~0.67 (Random Split) | Consistently top performer; directly models atomic interactions. |

| MAT [10] | Molecular Graph + Attention | 0.67 (PAMPA) | Attention mechanism captures long-range atom interactions. |

| Random Forest [15] | Molecular Fingerprints | Comparable to advanced models | Simplicity, robustness, and low computational cost. |

| Support Vector Regression [10] | Molecular Fingerprints | Lower than graph-based models | Effective for simpler feature sets. |

ML Model Implementation Workflow

- Data Curation: Obtain a curated dataset of cyclic peptides with experimental permeability values, such as the CycPeptMPDB [10] [15]. Preprocess SMILES strings and handle missing data.

- Feature Generation: Convert the peptide into a machine-readable format. Common representations include:

- Molecular Graphs: Atoms as nodes, bonds as edges, used as input for DMPNN or MAT.

- Molecular Fingerprints: Fixed-length bit vectors representing structural features, used for Random Forest or SVR.

- Model Training and Validation:

- Split data into training, validation, and test sets. Use scaffold splitting (grouping by molecular core) for a more rigorous assessment of generalizability to novel chemotypes [15].

- Train the model on the training set, using the validation set for hyperparameter tuning.

- Evaluate final performance on the held-out test set using metrics like R² (regression) or AUC-ROC (classification).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Software

Table 3: Key Computational Tools for Cyclic Peptide Ensemble Studies

| Tool Name | Type/Category | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| GROMACS [16] | MD Simulation Software | High-performance engine for running cMD and REMD simulations. |

| NAMD [14] | MD Simulation Software | Highly scalable MD engine with implementations of enhanced sampling methods like GaMD. |

| VMD [14] | Molecular Visualization & Analysis | System setup, trajectory visualization, and calculation of geometric properties (e.g., SASA, H-bonds). |

| CHARMM36 [14] | Molecular Force Field | Empirical energy function parameters for proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids. |

| AMBER ff99SB-ILDN [16] | Molecular Force Field | A widely used force field for proteins, known for good balance in modeling folded and disordered states. |

| CycPeptMPDB [15] | Database | Curated repository of cyclic peptide sequences and experimental permeability data for training ML models. |

| RDKit [15] | Cheminformatics Library | Generation of molecular fingerprints, scaffolds, and other descriptors from SMILES strings. |

| CPMP [10] | Web Tool / Model | Pre-trained MAT model for predicting cyclic peptide membrane permeability from SMILES. |

| CYCLOPS [17] | Web Tool | User-friendly simulator (CYCLOpeptide Permeability Simulator) for predicting membrane permeability. |

| p-Azidomethylphenyltrimethoxysilane | p-Azidomethylphenyltrimethoxysilane, CAS:83315-74-6, MF:C10H15N3O3Si, MW:253.33 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Thiophene-2-ethylamine HCl salt | Thiophene-2-ethylamine HCl salt, CAS:86188-24-1, MF:C6H10ClNS, MW:163.67 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Integrating molecular dynamics simulations and machine learning provides a powerful, multi-faceted framework for elucidating the relationship between the dynamic solution ensembles of cyclic peptides and their biological function and permeability. Enhanced sampling MD methods like GaMD and REMD offer a physics-based approach to reveal the conformational landscapes and chameleonic properties that underpin passive diffusion across membranes. Simultaneously, machine learning models, particularly those based on graph neural networks, enable rapid, high-throughput screening for permeable candidates. By adopting the protocols and tools outlined in this application note, researchers can accelerate the rational design of cyclic peptides, transforming them from challenging targets into viable therapeutics for intracellular applications.

A Step-by-Step MD Setup Protocol: From Structure to Production Run

Initial Structure Generation and Cyclization

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations have become an indispensable tool for studying cyclic peptides, which are promising therapeutic agents due to their conformational rigidity, binding specificity, and proteolytic resistance. A critical first step in any MD study is the generation of accurate initial structures and the proper implementation of cyclization constraints. This protocol details computational and experimental methodologies for creating realistic cyclic peptide structures suitable for subsequent simulation and analysis. The conformational behavior of cyclic peptides in solution is fundamentally governed by their cyclized structure, making proper initial setup essential for obtaining physiologically relevant results [9] [2].

The content is structured within a broader framework for establishing MD simulations of cyclic peptides, addressing the key initial phases of structure generation and cyclization that fundamentally influence all subsequent computational analysis. These protocols are designed for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals engaged in rational peptide therapeutic design.

Computational Structure Generation Methods

Computational methods for generating cyclic peptide structures have evolved significantly, with both physics-based and machine learning approaches now available. The choice of method depends on peptide size, presence of non-canonical amino acids, and desired structural features.

Physics-Based De Novo Design

Physics-based approaches remain valuable for their ability to handle diverse chemical spaces, including non-canonical and D-amino acids. These methods utilize force fields and sampling algorithms to explore conformational space.

Table 1: Physics-Based Computational Methods for Cyclic Peptide Structure Generation

| Method/Software | Key Algorithm | Peptide Size Range | Special Features | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CyclicChamp | Simulated annealing with cyclic constraints | 7-24 residues | Handles mixed chirality; No disulfide bonds required | De novo design of stable macrocycles [1] [18] |

| Rosetta | Generalized Kinematic Closure (GenKIC) | 7-13 residues (standard); Up to 26 residues (with disulfides) | Monte Carlo sequence design; Mixed L/D-amino acids | Small cyclic peptide design [1] |

| Replica-Exchange MD (REMD) | Parallel sampling at multiple temperatures | Varies | Enhanced conformational sampling | Solution structure determination [9] [19] |

For peptides larger than 13 residues, the CyclicChamp pipeline provides a robust approach. The algorithm converts cyclic constraints into an error function and employs simulated annealing to search for low-energy peptide backbones while maintaining peptide closure. This method addresses the high-dimensionality challenge that large macrocycle designs encounter, making conformational sampling tractable for 15- to 24-residue cyclic peptides without additional cross-links or symmetry requirements [1].

The following diagram illustrates the core computational workflow for generating cyclic peptide structures:

Machine Learning Approaches

Recent advances in machine learning have produced specialized tools for cyclic peptide structure prediction and design:

- AfCycDesign: Encodes cyclic backbone constraints into amino acid relative position matrices using AlphaFold architecture, effective for 7-13 residue peptides [1]

- RFpeptides: Uses RFdiffusion for backbone generation and ProteinMPNN for sequence design, capable of generating binders of 13-16 residues [1]

- HighFold: Predicts macrocycles with disulfide bonds for peptides of 12-39 residues [1]

A significant limitation of current ML approaches is their reliance on training data containing only canonical L-amino acids, making them less suitable for designing peptides with D-amino acids or non-canonical residues [1]. For such applications, physics-based methods remain preferable.

Experimental Cyclization Strategies

Experimental cyclization methods provide both synthetic templates for simulation and validation pathways for computationally designed peptides. These techniques can be categorized by the type of linkage formed and the resulting structural constraints.

Cyclization Methodologies

Table 2: Experimental Cyclization Strategies for Peptide Macrocyclization

| Method Category | Specific Approach | Linkage Formed | Key Features | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Head-to-Tail | Lactam formation | Amide bond | Mimics natural backbone; Common in natural products | Pre-organization required; Epimerization risk [20] |

| Native Chemical Ligation (NCL) | Amide bond | Chemoselective; Aqueous conditions; No side chain protection | Requires N-terminal Cysteine [20] [21] | |

| Side Chain-to-Side Chain | Disulfide formation | Disulfide bond | Reversible; Native to many proteins | redox-sensitive [21] |

| Ring-closing metathesis | Carbon-carbon bond | Stable; Conformational constraint | Requires unnatural amino acids [20] | |

| Stapled peptides | Various | Stabilizes secondary structures | Requires special synthetic approaches [20] | |

| Head/Tail-to-Side Chain | Thiazolidine formation | Thiazolidine ring | Chemoselective | Ring contraction mechanism [20] |

The following workflow outlines key experimental cyclization processes and their relationship to computational structure preparation:

Practical Implementation Considerations

Successful experimental cyclization requires addressing several practical challenges:

- Pre-organization: Incorporation of turn-inducing elements like proline, D-amino acids, or N-methylation to favor cyclization-prone conformations [20]

- Coupling reagents: Careful selection to minimize epimerization (e.g., PyBOP for cyclomarin C; HATU/Oxyma Pure for teixobactin) [20]

- Pseudo-dilution effects: Using solid-phase supports to favor intramolecular reactions over intermolecular oligomerization [20]

- Chemoselective approaches: Native chemical ligation and similar methods that avoid protecting groups and are compatible with aqueous conditions [20]

For head-to-tail cyclization of peptides shorter than seven residues, particular care is needed to prevent cyclodimerization and C-terminal epimerization [20].

MD Simulation Setup for Cyclic Peptides

Initial Structure Preparation

Proper preparation of cyclic peptide structures is essential for successful MD simulations. The protocol varies based on the cyclization method:

For computationally generated structures:

- Extract lowest energy conformation from design pipeline

- Ensure proper bond lengths and angles at the cyclization site

- Confirm closure through distance measurements between connecting atoms

For experimentally derived structures:

- Implement appropriate distance constraints for the cyclization type

- Apply proper atom types and parameters for non-native linkages

- For disulfide bonds, verify proper chirality and geometry

Specialized Simulation Techniques

Enhanced sampling methods are particularly valuable for cyclic peptides due to their conformational complexity:

- Replica-Exchange MD (REMD): Implemented in GROMACS, this method allows parallel sampling at multiple temperatures, enhancing conformational exploration [9] [2]

- Residue-specific force fields: Specialized force fields that account for the unique conformational preferences of amino acids in cyclic contexts [9] [2]

- Clustering analysis: Identification of representative conformations from simulation trajectories to characterize the structural ensemble [9]

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Tools for Cyclic Peptide Research

| Category | Specific Tool/Reagent | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Simulation Software | GROMACS | MD simulation engine | REMD implementation for enhanced sampling [9] [2] |

| Rosetta | Protein structure prediction & design | GenKIC for cyclic conformation sampling [1] | |

| CyclicChamp | De novo cyclic peptide design | Specialized for 15-24 residue macrocycles [1] [18] | |

| Coupling Reagents | HATU/Oxyma Pure/HOAt/DIEA | Amide bond formation | Used for teixobactin cyclization [20] |

| PyBOP | Amide bond formation | Applied in cyclomarin C synthesis [20] | |

| Chemical Tools | Tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP) | Disulfide reduction | Used in NCL for cyclic peptide formation [20] |

| Methyldiaminobenzoyl (MeDbz) linker | Solid-phase support | Enables on-resin NCL for head-to-tail cyclization [20] |

The generation of accurate initial structures and proper implementation of cyclization constraints form the critical foundation for successful MD simulations of cyclic peptides. Computational methods like CyclicChamp have expanded the accessible size range for de novo design up to 24 residues, while experimental techniques such as native chemical ligation provide robust synthetic routes for model validation. The integration of these approaches enables researchers to create realistic cyclic peptide models that faithfully represent their solution behavior, supporting the rational design of novel therapeutic agents targeting challenging protein-protein interactions. As computational power increases and algorithms refine, the synergy between in silico design and experimental synthesis will continue to accelerate the development of cyclic peptide therapeutics.

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation has emerged as an indispensable tool for studying the structural ensembles and biological activities of cyclic peptides, which are promising therapeutic candidates capable of targeting protein-protein interactions [19]. The accuracy of these simulations is profoundly dependent on the molecular mechanics force field employed—the mathematical function and parameters that describe the potential energy of a molecular system [3]. Unlike linear peptides and proteins, cyclic peptides present unique challenges for force fields due to their constrained geometries, diverse non-canonical sequences, and complex conformational dynamics in solution [4]. An inappropriate force field selection can lead to inaccurate structural predictions, potentially misdirecting experimental validation and drug development efforts. This application note provides a critical evaluation of contemporary force field performance for cyclic peptide simulations and establishes detailed protocols for researchers embarking on computational studies of these pharmaceutically relevant molecules.

Performance Assessment: Quantitative Comparison of Force Fields

Performance Against NMR Data for Canonical Cyclic Peptides

Systematic evaluation of force field performance against experimental nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) data provides the most reliable metric for assessing accuracy in simulating cyclic peptide structural ensembles. A recent benchmark study evaluated seven state-of-the-art force fields against NMR-derived structural information for 12 benchmark cyclic peptides (6 cyclic pentapeptides, 4 cyclic hexapeptides, and 2 cyclic heptapeptides) in aqueous solution [3].

Table 1: Force Field Performance for Cyclic Peptides Against NMR Data

| Force Field + Solvent Model | Peptides Matching NMR Data | Performance Rating | Recommended Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| RSFF2 + TIP3P | 10/12 | Excellent | General purpose; well-structured peptides |

| RSFF2C + TIP3P | 10/12 | Excellent | General purpose; broad conformational sampling |

| Amber14SB + TIP3P | 10/12 | Excellent | General purpose; compatibility with Amber tools |

| Amber19SB + OPC | 8/12 | Good | Newer Amber variant; membrane permeability studies |

| OPLS-AA/M + TIP4P | 5/12 | Moderate | Cross-validation; specific peptide classes |

| Amber03 + TIP3P | 5/12 | Moderate | Legacy systems comparison |

| Amber14SBonlysc + GB-neck2 | 5/12 | Moderate | Implicit solvent requirements; rapid screening |

The data reveals a clear performance hierarchy, with RSFF2+TIP3P, RSFF2C+TIP3P, and Amber14SB+TIP3P demonstrating superior capability in recapitulating experimental observations [3]. These three force fields successfully reproduced NMR-derived structural information for 10 out of the 12 benchmark cyclic peptides. The study also highlighted the critical importance of solvent model pairing, with TIP3P emerging as the preferred water model for cyclic peptide simulations.

Special Considerations for Non-Canonical and Hybrid Peptides

While standard force fields perform well for conventional cyclic peptides, their accuracy diminishes for systems containing non-proteinogenic elements. A systematic assessment of eight widely used force fields (from AMBER, OPLS, CHARMM, and GROMOS families) against 79 NMR observables for cyclic α/β-peptides containing β-amino acids revealed significant limitations [22]. Most investigated force fields displayed good agreement with experimental ^3J(HN,Hα) coupling constants for α-amino acid residues, but showed poor agreement for NMR observables directly related to β-amino acids [22]. This performance deficit highlights the need for careful force field selection and potential parameterization when working with hybrid cyclic peptides containing non-canonical amino acids.

Parameterization Protocols for Novel Cyclic Peptides

Automated Parameterization Workflow

Novel cyclic peptides often contain chemical motifs not fully represented in standard force fields, necessitating additional parameterization. The General Automated Atomic Model Parameterization (GAAMP) method provides a robust framework for generating parameters compatible with biomolecular force fields using ab initio quantum mechanical (QM) target data [23].

Diagram 1: Automated parameterization workflow for novel cyclic peptides. Critical optimization steps (green) target electrostatic potential, water interactions, and dihedral parameters using QM reference data.

The GAAMP protocol combines information from both electrostatic potential (ESP) fitting and explicit water interaction energies to optimize atomic partial charges, providing more robustly accurate models than either approach alone [23]. Additionally, the method automatically identifies "soft" dihedrals with low energy barriers and parameterizes them using systematic one-dimensional dihedral scans from QM calculations.

System Setup and Equilibration Protocol

Proper system setup and equilibration are essential for generating physically realistic simulations of cyclic peptides. The following protocol, adapted from contemporary cyclic peptide simulation studies [3], ensures stable production dynamics:

Initial Structure Preparation:

- Build linear peptide with all glycine residues and random (ϕ, ψ) dihedrals using molecular visualization software (e.g., Chimera)

- Perform head-to-tail cyclization between N- and C-termini

- Conduct energy minimization in vacuum using steepest descent algorithm

- Mutate glycine residues to desired sequence

- Generate at least two distinct initial conformations (backbone RMSD ≥ 1.2 Å) to verify simulation convergence

Solvation and Equilibration:

- Solvate the cyclic peptide in a rectangular water box with minimum 1.0 nm distance between peptide and box walls

- Add counterions (Na⺠or Clâ») to neutralize system charge

- Energy minimization of solvated system (steepest descent algorithm)

- 50 ps NVT simulation with peptide heavy atoms restrained (1000 kJ·molâ»Â¹Â·nmâ»Â²)

- 50 ps NPT simulation with same restraints

- 100 ps NVT simulation without restraints

- 100 ps NPT simulation without restraints

Simulation Parameters:

- Temperature: 300 K (V-rescale thermostat, coupling constant 0.1 ps)

- Pressure: 1 bar (Parrinello-Rahman barostat, coupling constant 2.0 ps)

- Electrostatics: Particle Mesh Ewald (cutoff 1.0 nm)

- van der Waals: cutoff 1.0 nm with long-range dispersion correction

- Constraints: LINCS for all bonds (equilibration) or bonds involving hydrogens (production)

- Integration: Leapfrog algorithm with 2 fs time step

Advanced Sampling and Efficiency Enhancement

Enhanced Sampling Techniques

Conventional MD simulations often struggle to adequately sample the conformational landscape of cyclic peptides within practical computational timeframes. Enhanced sampling methods significantly improve conformational sampling efficiency:

Bias-Exchange Metadynamics (BE-META):

- Implement multiple replicas biasing different collective variables (CVs)

- For n-residue cyclic peptide, use 2n biased replicas

- n replicas bias 2D CVs (ϕᵢ, ψᵢ)

- n replicas bias 2D CVs (ψᵢ, ϕᵢ₊â‚)

- Regular exchange attempts between replicas to ensure proper sampling [3]

Gaussian Accelerated MD (GaMD):

- Adds a boost potential to system potential energy when below threshold energy E

- Enables "dual-boost" potential applied to both total potential and dihedral energies

- Allows accurate reweighting using cumulant expansion to recover original free energy landscape [24]

- Particularly effective for studying membrane permeability of cyclic peptides [24]

Simulation Acceleration Strategies

Two principal methods exist for increasing integration time steps beyond the standard 2 fs limit, significantly reducing computational cost for long timescale simulations:

Hydrogen Mass Repartitioning (HMR):

- Transfers 2-3 Da of mass from heavy atoms to bonded hydrogen atoms

- Allows time steps of 5-7 fs while maintaining simulation stability

- Best suited for united atom force fields (e.g., GROMOS) due to challenges with methyl groups [25]

Hydrogen Isotope Exchange (HIE):

- Directly increases hydrogen atom mass (equivalent to deuteration)

- Avoids mass imbalance issues in HMR with multiple bonded hydrogens

- Allows time steps of 5-7 fs with excellent energy conservation [25]

Table 2: Acceleration Methods for Cyclic Peptide MD Simulations

| Method | Principle | Max Time Step | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HMR | Mass transfer from heavy atoms to hydrogens | 5-7 fs | Well-established; good stability | Problematic for methyl groups; non-physical |

| HIE | Direct mass increase of hydrogens | 5-7 fs | Conceptually simple; experimentally correspondable | Alters vibrational properties |

| GaMD | Boost potential enhances barrier crossing | 2-4 fs | No predefined CVs needed; excellent for permeability | Complex reweighting; parameter sensitivity |

Integration with Machine Learning Approaches

Recent advances combine MD simulations with machine learning (ML) to dramatically accelerate structural ensemble prediction for cyclic peptides. The StrEAMM (Structural Ensembles Achieved by Molecular Dynamics and Machine Learning) method uses MD simulation results for several hundred cyclic pentapeptides to train ML models that can predict structural ensembles for entire sequence spaces [4].

Diagram 2: Integration of molecular dynamics with machine learning for rapid prediction of cyclic peptide structural ensembles. The StrEAMM approach achieves a seven-order-of-magnitude speed improvement over conventional MD [4].

The StrEAMM approach represents cyclic peptide conformations using structural digits that categorize (ϕ, ψ) space into 10 distinct regions (B, Π, Γ, Λ, Z, β, π, γ, λ, ζ), enabling efficient structural encoding for machine learning applications [4]. This methodology provides MD-quality predictions of structural ensembles in seconds rather than days, revolutionizing high-throughput cyclic peptide screening.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Cyclic Peptide Research

| Tool Category | Specific Software/Package | Primary Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Simulation Engines | GROMACS, NAMD, AMBER | MD simulation execution | GROMACS recommended for speed; AMBER for integrated workflows |

| Enhanced Sampling | PLUMED | Advanced sampling algorithms | Essential for BE-META; community CV library available |

| Force Fields | RSFF2, Amber14SB, CHARMM36 | Molecular mechanics parameters | RSFF2 recommended for cyclic peptides; CHARMM36 for membranes |

| Parameterization | GAAMP, Antechamber, CGenFF | Novel molecule parameterization | GAAMP for QM-optimized parameters; Antechamber for GAFF |

| Analysis | MDAnalysis, LOOS, VMD | Trajectory analysis and visualization | MDAnalysis for programmatic analysis; VMD for visualization |

| Machine Learning | StrEAMM Models | Rapid ensemble prediction | Seconds vs days for MD; trained on pentapeptide data |

| (r)-1-Phenylethanesulfonic acid | (r)-1-Phenylethanesulfonic acid, CAS:86963-40-8, MF:C8H10O3S, MW:186.23 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| 2-Ethoxynaphthalene-1-carboxamide | 2-Ethoxynaphthalene-1-carboxamide|High-Quality Research Chemical | 2-Ethoxynaphthalene-1-carboxamide for Research Use Only (RUO). Explore its potential as a building block in medicinal chemistry and anticoagulant research. | Bench Chemicals |

Based on comprehensive performance assessments and methodological developments, we recommend the following best practices for force field selection and parameterization in cyclic peptide research:

For general-purpose cyclic peptide simulations, prioritize RSFF2+TIP3P, RSFF2C+TIP3P, or Amber14SB+TIP3P based on their demonstrated superior performance against NMR experimental data [3].

For membrane permeability studies, consider GaMD simulations with CHARMM36 in both aqueous and membrane-mimetic environments (e.g., octanol) to capture environment-dependent conformational preferences [24].

For high-throughput screening, implement the StrEAMM framework to predict structural ensembles for large sequence spaces, using limited MD simulations for validation [4].

For cyclic peptides containing non-canonical elements, employ automated parameterization tools (GAAMP) with QM target data to ensure accurate representation of novel chemical motifs [23].

For enhanced sampling, utilize BE-META with biasing of backbone dihedrals to efficiently explore the constrained conformational landscape of cyclic peptides [3].

As force fields continue to evolve and computational methodologies advance, the integration of physical simulations with machine learning approaches promises to further accelerate the rational design of cyclic peptide therapeutics.

In molecular dynamics (MD) simulations of cyclic peptides, the accurate representation of the solvent and ionic environment is not merely a technical step but a fundamental determinant of success. Cyclic peptides, with their constrained geometry and diverse conformational behaviors, are highly sensitive to their electrostatic and hydrophobic environment [7] [1]. The choices made during system building—whether to model water molecules explicitly or implicitly, and how to neutralize and ionize the system—directly impact the stability of the simulation, the accuracy of the conformational sampling, and the biological relevance of the results [26] [27]. This guide outlines best practices for solvation and ionization, framed within the context of cyclic peptide research for drug development.

Solvation Methods: Explicit vs. Implicit Solvent Models

The first major decision in building a simulation system is selecting a solvation model. The two primary approaches, explicit and implicit solvation, offer a trade-off between computational efficiency and physical detail. The table below provides a comparative overview.

Table 1: Comparison of Explicit and Implicit Solvation Models for MD Simulations

| Feature | Explicit Solvent | Implicit Solvent (Continuum) |

|---|---|---|

| Physical Representation | Discrete water molecules (e.g., TIP3P, TIP4P) surrounding the solute [11] | Solvent represented as a continuous medium with a dielectric constant [28] |

| Computational Cost | High (most computational resources spent on water) [11] | Low (dramatically faster than explicit solvent) [26] [28] |

| Sampling Speed | Slower conformational exploration due to solvent viscosity [28] | Faster exploration due to absence of viscous drag [26] |

| Solvation Free Energy | Not directly calculated; emerges from interactions | Directly estimated, e.g., via Generalized Born (GB) or Poisson-Boltzmann (PB) models [28] |

| Treatment of Hydrophobic Effect | Naturally emerges from water-water and water-solute interactions | Must be added empirically, often via a Solvent Accessible Surface Area (SASA) term [28] |

| Ionic Effects | Added explicitly as discrete ions [27] | Modeled via the Poisson-Boltzmann equation [28] |

| Ideal Use Cases | Final validation, studying specific solvent interactions, refining structures [7] [1] | High-throughput screening, initial conformational sampling, long time-scale folding studies [26] [11] |

For cyclic peptides, which often adopt multiple conformations in solution, the choice is particularly nuanced [7]. Explicit solvent simulations are considered the gold standard for producing physically accurate dynamics and are crucial for final validation of designs [1]. However, the computational efficiency of implicit solvent models like the Generalized Born (GB) model makes them invaluable for large-scale conformational sampling and high-throughput screening in early-stage projects [26] [11]. A common strategy is to use implicit solvent for extensive sampling and then refine promising structures or characterize their dynamics using explicit solvent simulations.

The Generalized Born Model and Its Augmentations

The Generalized Born (GB) model is a popular implicit solvent approximation due to its favorable balance of speed and accuracy. It models electrostatic solvation energy using the following functional form [28]: [ Gs = -\frac{1}{8\pi\epsilon0}\left(1-\frac{1}{\epsilon}\right)\sum{i,j}^{N}\frac{qi qj}{f{GB}} ] where ( f{GB} = \sqrt{r{ij}^2 + a{ij}^2e^{-D}} ) and ( a{ij} = \sqrt{ai aj} ).

This model is often augmented with a hydrophobic solvent accessible surface area (SA) term to account for the non-polar contribution to solvation, creating a GBSA model [28]. This combination has been successfully used in protein dynamics, modeling, and design [26].

Ionization Protocols: Neutralization and Achieving Physiological Conditions

Proper ionization is essential for achieving correct electrostatic interactions and mimicking the biological environment. This process involves two main steps.

System Neutralization

The first and mandatory step is to neutralize the total charge of the solute (e.g., a cyclic peptide). A net charge in a periodic system can lead to unphysical calculations of electrostatic energy [27]. Counter-ions, such as Na+ for negatively charged solutes or Cl- for positively charged ones, are added to bring the total system charge to zero. It is recommended to place ions according to the electrostatic potential of the macromolecule before solvation, as this is more physically realistic and requires less equilibration than random placement [27].

Adding Physiological Salt Concentrations

After neutralization, additional ions are added to mimic a specific salt concentration, such as a physiological 150 mM NaCl solution. The number of ion pairs needed can be estimated using the formula [27]: [ N{Ions} = 0.0187 \cdot [Molarity] \cdot N{WaterMol} ] where ( N_{WaterMol} ) is the number of water molecules in the simulation box. For more accurate concentrations that account for electrostatic screening effects, tools like the SLTCAP server can be used [27].

Table 2: Ion Addition Strategies and Best Practices

| Step | Description | Best Practice / Formula | Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Neutralization | Add counter-ions to balance the solute's charge. | Place ions based on electrostatic potential. | Corrects for net charge, avoids unphysical electrostatics and long equilibration [29] [27]. |

| 2. Salination | Add ion pairs (e.g., Na+/Cl-) to achieve target concentration. | ( N{Ions} = 0.0187 \cdot [Molarity] \cdot N{WaterMol} ) [27] | Mimics the ionic strength of a biological environment, which affects conformation and dynamics [27]. |

Practical Protocols for System Setup

Protocol 1: Explicit Solvent Setup with AMBER

This protocol is ideal for production simulations and final validation of cyclic peptide structures [30] [27].

- Initial Preparation: Obtain the initial cyclic peptide structure from PDB or computational modeling. Ensure the terminal amide bond is correctly formed.

- Load Force Field and Solute: In the

tleapmodule of AMBER, load the appropriate force field (e.g.,leaprc.protein.ff19SB) and your cyclic peptide structure [27]. - Neutralize the System: Use the

addionscommand to add the necessary counter-ions to bring the net charge to zero. Pre-placing ions based on electrostatic potential is recommended [27]. - Solvation: Place the neutralized solute into a solvent box. A cubic or octahedral box with a minimum distance of 10-15 Ã… between the solute and the box edge is standard to prevent artificial self-interactions [27].

- Add Salt: Introduce additional ion pairs to achieve physiological concentration (e.g., 150 mM). The

addionsrandcommand can be used for this purpose, which replaces random water molecules with ions [27]. - Generate Topology and Coordinates: Output the final topology and coordinate files for the simulation.

Protocol 2: Implicit Solvent Setup for Enhanced Sampling

This protocol is suitable for replica-exchange MD (REMD) or high-throughput conformational sampling of cyclic peptides [2] [11].

- Select an Implicit Solvent Model: Choose a model such as the Generalized Born (GB) with a suitable parameter set (e.g., GBNP, GBSW, GBMV) [26]. The choice should be compatible with your force field.

- Incorporate Non-Polar Effects: Augment the GB model with a surface area (SA) term to account for the hydrophobic effect. This creates a GBSA model, which provides a more complete description of solvation [28].

- Configure the MD Engine: In your MD software (e.g., AMBER, GROMACS), set the parameters to use the implicit solvent model instead of explicit water. This typically involves specifying the GB method and its associated parameters in the configuration file.

- Run Enhanced Sampling Simulation: With the reduced computational cost, employ methods like REMD to achieve broad conformational sampling, which is crucial for cyclic peptides that may have multiple low-energy states [2] [7].

The following workflow diagram summarizes the decision process and key steps for building a solvated and ionized system for cyclic peptide MD simulations.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Cyclic Peptide MD Simulations

| Tool / Resource | Function | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| AMBER | A suite of biomolecular simulation programs [30] | Includes tleap for system building, sander/pmemd for simulation, and supports both explicit and implicit solvent [30] [27]. |

| GROMACS | High-performance MD simulation package [2] | Known for its speed; can be used with AMBER force fields and topology files for cyclic peptide simulations [27]. |

| CHARMM | MD simulation and analysis program [26] | Often used with implicit solvent (GB) models for protein folding and decoy discrimination studies [26]. |

| OPC Water Model | A 4-point explicit water model [27] | Provides a highly accurate representation of water properties for explicit solvent simulations [27]. |

| Generalized Born (GB) Models | A class of implicit solvent models [26] [28] | Models like GBNP, GBMV2 are optimized for use with specific force fields (e.g., CHARMM, AMBER) [26]. |

| SLTCAP Server | An online calculation tool [27] | Calculates the number of ions needed for a target concentration, correcting for electrostatic screening effects [27]. |

Meticulous construction of the solvation and ionization environment is a prerequisite for obtaining reliable and biologically relevant insights from MD simulations of cyclic peptides. The choice between explicit and implicit solvent should be guided by the specific research objective, whether it is ultimate accuracy or computational efficiency. Adhering to the established protocols of neutralization and salination ensures electrostatic stability and physiological relevance. By integrating these best practices, researchers can build robust simulation systems that provide a solid foundation for understanding the structure, dynamics, and function of cyclic peptides in drug discovery pipelines.

In molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, the equilibration phase is a preparatory period where the macromolecular system and its surrounding solvent undergo relaxation before reaching a stationary state suitable for data collection [31]. This stage is particularly critical for cyclic peptide research, as these molecules often adopt multiple conformations in solution, and their structural ensembles are key to understanding their biological activity and membrane permeability [4] [32]. A properly equilibrated system ensures that the subsequent production phase samples from a thermodynamically representative ensemble, thereby providing reliable insights into cyclic peptide behavior.