A Comprehensive Guide to Trajectory Analysis Tools for Mean Squared Displacement in Biomedical Research

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive overview of Mean Squared Displacement (MSD) analysis for single-particle trajectories.

A Comprehensive Guide to Trajectory Analysis Tools for Mean Squared Displacement in Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive overview of Mean Squared Displacement (MSD) analysis for single-particle trajectories. It covers foundational principles, from defining MSD and its derivation for Brownian motion to its role in distinguishing diffusion modes. The guide explores practical methodologies through dedicated software tools like MDAnalysis, @msdanalyzer, and TRAVIS, and addresses critical troubleshooting aspects such as managing localization error and short trajectories. Furthermore, it examines advanced validation frameworks, including the AnDi Challenge benchmarks, and the growing impact of machine learning for classifying complex motion patterns, offering a complete resource for implementing robust MSD analysis in live-cell imaging and drug development.

Understanding MSD: The Fundamental Metric for Analyzing Particle Motion

Mean Squared Displacement

Core Concept and Definition

Mean Squared Displacement (MSD) is a fundamental metric in statistical mechanics and trajectory analysis that quantifies the average squared distance a particle travels from its starting point over time [1]. It measures the spatial extent of random motion and represents the portion of a system "explored" by a random walker [1]. In the context of single-particle tracking (SPT) and molecular dynamics, MSD analysis provides crucial insights into diffusion coefficients, transport mechanisms, and the nature of particle motion [2].

The MSD for a particle in n-dimensional space is defined as the average of the squared displacement magnitudes over all particles in a system or over multiple time intervals for a single trajectory [1]. For a single trajectory with discrete time points, the time-averaged MSD is commonly calculated as:

[MSD(\tau = n\Delta t) = \frac{1}{N-n}\sum{i=1}^{N-n} |\vec{r}(t{i+n}) - \vec{r}(t_i)|^2]

where (\vec{r}(t)) is the particle's position at time (t), (\Delta t) is the time between frames, (N) is the total number of points in the trajectory, and (\tau = n\Delta t) is the time lag [1] [2]. For continuous time series, the formulation becomes:

[\overline{\delta^2(\Delta)} = \frac{1}{T-\Delta}\int_0^{T-\Delta} [r(t+\Delta) - r(t)]^2 dt]

where (T) is the total trajectory length [1].

Table 1: Fundamental MSD Formulas Across Different Scenarios

| Scenario | MSD Formula | Parameters |

|---|---|---|

| General Definition (nD) | (MSD = \langle |\mathbf{x}(t) - \mathbf{x_0}|^2 \rangle) | (\mathbf{x}(t)): position at time (t); (\mathbf{x_0}): reference position [1] |

| Brownian Motion (1D) | (\langle (x(t)-x_0)^2 \rangle = 2Dt) | (D): diffusion coefficient; (t): time [1] |

| Brownian Motion (nD) | (MSD = 2nDt) | (n): dimensions; (D): diffusion coefficient; (t): time [1] |

| Anomalous Diffusion | (MSD(\tau) = 2\nu D_\alpha \tau^\alpha) | (\nu): dimensions; (D_\alpha): generalized coefficient; (\alpha): anomalous exponent [2] |

Interpretation of Motion Types from MSD Profiles

The functional form of the MSD curve reveals the underlying nature of particle motion, enabling researchers to classify diffusion behavior and identify physical constraints or active transport mechanisms [2] [3].

Linear MSD (Brownian Diffusion): When MSD increases linearly with time lag ((\text{MSD} \propto \tau)), the particle undergoes simple Brownian motion—aimless, random wandering without directional bias or confinement [3]. The slope of the MSD curve is proportional to the diffusion coefficient ((D)) through the relationship (\frac{d(MSD)}{dt} \propto 2nD), where (n) is the number of dimensions [4].

Superlinear MSD (Directed Motion): When the MSD curve follows an increasing slope (typically (\text{MSD} \propto \tau^2)), the particle exhibits directed or active motion with a constant velocity component, often due to external forces or molecular motors [2] [3]. This behavior indicates systematic displacement superimposed on random diffusion.

Plateauing MSD (Constrained Motion): When the MSD curve plateaus at longer time lags, the particle's motion is spatially constrained [3]. The square root of the plateau height (minus measurement error) estimates the size of the confinement region [3], such as a membrane domain or organelle boundary.

Anomalous Diffusion: When MSD follows a power law (\text{MSD} \propto \tau^\alpha), the motion is classified as anomalous [2]. The anomalous exponent ((\alpha)) distinguishes subdiffusion ((\alpha < 1)), often caused by crowding or binding events, from superdiffusion ((\alpha > 1)), which may indicate active transport [2].

Table 2: Characterizing Motion Types through MSD Analysis

| Motion Type | MSD Trend | Mathematical Form | Physical Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Immobile | Constant near zero | (MSD \approx 4\sigma^2) | Particle is stationary or tightly bound [2] |

| Brownian Diffusion | Linear | (MSD = 4D\tau) (2D) | Free, random motion in homogeneous environment [3] |

| Anomalous Subdiffusion | Power law ((\alpha < 1)) | (MSD = 4D_\alpha\tau^\alpha) | Hindered motion in crowded media [2] |

| Anomalous Superdiffusion | Power law ((\alpha > 1)) | (MSD = 4D_\alpha\tau^\alpha) | Active transport with directional bias [2] |

| Directed Motion | Quadratic | (MSD = v^2\tau^2 + 4D\tau) | Constant drift with velocity (v) plus diffusion [2] |

| Confined Motion | Plateau | (MSD \approx R_c^2) | Motion restricted within radius (R_c) [3] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Single-Particle Tracking (SPT) MSD Protocol

Purpose: To extract quantitative diffusion parameters and classify motion types from individual particle trajectories in biological systems, such as membrane receptors or intracellular vesicles [2].

Workflow:

- Sample Preparation and Imaging

- Fluorescently label molecules or particles of interest (e.g., quantum dots, organic dyes, GFP-tagged proteins)

- Acquire time-lapse images with appropriate temporal resolution ((\Delta t)) to capture motion dynamics

- Ensure optimal signal-to-noise ratio to minimize localization errors [5]

Trajectory Reconstruction

- Identify particle positions in each frame using localization algorithms (e.g., Gaussian fitting)

- Link positions across frames to reconstruct trajectories

- Filter trajectories based on minimum length (typically >10 points) and tracking quality [2]

MSD Calculation

- For each trajectory, compute MSD for all available time lags using the formula: [MSD(n\Delta t) = \frac{1}{N-n}\sum_{i=1}^{N-n} [x(i+n) - x(i)]^2 + [y(i+n) - y(i)]^2]

- For 2D data (common in microscopy), include both x and y coordinates [2]

MSD Curve Fitting and Parameter Extraction

- Plot MSD versus time lag ((\tau))

- Identify the linear region for Brownian motion, typically at short to intermediate time lags

- Fit appropriate model to extract parameters:

- For Brownian motion: Linear fit to obtain (D = \frac{slope}{4}) (2D) or (D = \frac{slope}{6}) (3D)

- For anomalous diffusion: Power law fit (MSD = K\alpha\tau^\alpha) to obtain (\alpha) and (D\alpha) [2]

- Use optimal number of MSD points in fitting to balance precision and accuracy [5]

Molecular Dynamics (MD) MSD Protocol

Purpose: To compute self-diffusivity from molecular dynamics simulations of liquids, polymers, or biological macromolecules [6].

Workflow:

- Trajectory Generation

- Perform MD simulation with periodic boundary conditions

- Save particle coordinates at regular intervals

- Use unwrapped coordinates (correct for periodic boundary crossings) [6]

MSD Computation

- For each particle species of interest, calculate MSD using Einstein formula: [MSD(t) = \langle |\vec{r}i(t) - \vec{r}i(0)|^2 \rangle] where angle brackets denote averaging over all particles and time origins [7] [6]

- Implement efficient algorithms (e.g., FFT-based) for long trajectories to reduce O(N²) computational cost [6]

Diffusion Coefficient Extraction

Quantitative Data Analysis and Practical Considerations

Key Experimental Parameters and Their Effects

Table 3: Critical Experimental Parameters in MSD Analysis

| Parameter | Effect on MSD | Optimization Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Localization Uncertainty (σ) | Positive offset: (MSD(\tau) = 4D\tau + 4\sigma^2) [5] | Increase signal-to-noise ratio; more photons per frame [5] |

| Finite Camera Exposure (tE) | Negative offset: (MSD(\tau) = 4D\tau - 8DR\Delta t) [8] | Use shorter exposure; motion blur correction [5] |

| Trajectory Length (N) | Statistical precision; longer trajectories reduce uncertainty [5] | Aim for N > 10 points; balance with photobleaching [2] |

| Temporal Resolution (Δt) | Capturing relevant dynamics; too slow misses fast diffusion [2] | Match to expected diffusion speed (D); DΔt ~ pixel size² [5] |

| Reduced Localization Error (x = σ²/DΔt) | Determines optimal MSD points for fitting [5] | When x ≪ 1, use first 2 points; when x ≫ 1, use more points [5] |

Advanced MSD Applications and Methodologies

Anomalous Diffusion Analysis: For non-Brownian motion, fit MSD to general power law (MSD(\tau) = K_\alpha\tau^\alpha) using log-log plot where α is the slope [2]. Classification thresholds: α ≈ 1 (Brownian), α < 0.75 (subdiffusive), α > 1.25 (superdiffusive) [2].

Hidden Markov Models: Identify transitions between different diffusion states within single trajectories that may be masked in ensemble MSD analysis [2].

Machine Learning Approaches: Classify motion types using trajectory features beyond MSD, such as angles, velocities, and occupation times, particularly valuable for short, noisy trajectories [2].

Computational Implementation

Essential Algorithms and Code Considerations

MSD Calculation Methods:

- Simple windowed algorithm: Direct implementation of MSD formula with O(N²) scaling

- FFT-based algorithm: Improved O(N log N) scaling for long trajectories [6]

Critical Implementation Details:

- Use unwrapped coordinates when periodic boundary conditions are present [6]

- For MD simulations, apply nojump correction to account for periodic boundary crossings [6] [4]

- Average over all possible time origins to maximize statistical precision [1]

Data Fitting and Error Analysis

Optimal MSD Points Selection: The number of MSD points (p) to use for diffusion coefficient fitting significantly impacts estimate quality [5]. The optimal p depends on:

- Localization uncertainty (σ)

- Diffusion coefficient (D)

- Time step (Δt)

- Trajectory length (N) [5]

Error Estimation:

- Bootstrap resampling for confidence intervals [4]

- Consider finite-size effects in molecular simulations [6]

- Account for heteroscedasticity (changing variance) in MSD points [5]

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Tool/Reagent | Function/Application | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Fluorescent Labels | Particle tracking in biological systems | Organic dyes (e.g., Cy3, Alexa Fluor); Quantum Dots; GFP-fusion proteins [2] |

| MDAnalysis | MD trajectory analysis | Python library; EinsteinMSD class; FFT-accelerated computation [6] |

| tidynamics | Efficient MSD calculation | Fast FFT-based algorithm; required by MDAnalysis for optimized performance [6] |

| Unwrapped Trajectories | Correct MSD calculation | GROMACS: gmx trjconv -pbc nojump; essential for periodic systems [6] |

| Bootstrapping | Error estimation | Resampling method for confidence intervals on D and α [4] |

| iMSD | Image-based MSD | Alternative to SPT; analyzes dynamics directly from image correlations [9] |

| BF738735 | BF738735, MF:C21H19FN4O3S, MW:426.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Cephaeline | Cephaeline, CAS:483-17-0; 5853-29-2, MF:C28H38N2O4, MW:466.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The Mean Squared Displacement (MSD) is a fundamental metric in the study of particle dynamics and random walks, serving as the most common measure of the spatial extent of random motion. In the context of Brownian motion, the Einstein relation provides a foundational connection between the observed MSD and the underlying diffusion coefficient, forming a cornerstone of molecular-kinetic theory. This relation has proven indispensable across diverse fields, from biophysics and environmental engineering to materials science and drug development, where it is used to determine if particle spreading occurs via pure diffusion or is influenced by advective forces [1].

For researchers engaged in trajectory analysis, the MSD offers a powerful tool for quantifying the portion of a system "explored" by a random walker. Its prominence extends to the Debye-Waller factor in solid-state physics and the Langevin equation describing Brownian particle diffusion [1]. This protocol details the theoretical foundation, computational implementation, and analytical frameworks for applying the Einstein relation to derive MSD for Brownian motion, with specific consideration to trajectory analysis applications in pharmaceutical and materials research.

Theoretical Foundation

The Einstein Relation and MSD

The mean squared displacement quantifies the deviation of a particle's position from a reference position over time. For a single particle, the MSD in one dimension is defined as the ensemble average:

[ \text{MSD} \equiv \left\langle \left( x(t) - x_0 \right)^2 \right\rangle ]

where (x(t)) is the particle's position at time (t) and (x_0) is its reference position at time zero [1]. For practical applications with multiple particles, the MSD is calculated as:

[ \text{MSD} = \frac{1}{N} \sum_{i=1}^{N} \left| \mathbf{x}^{(i)}(t) - \mathbf{x}^{(i)}(0) \right|^2 ]

where (N) represents the number of particles and (\mathbf{x}^{(i)}(t)) denotes the position of particle (i) at time (t) [1].

The profound connection between MSD and the diffusion coefficient (D) is established through the Einstein relation, which for one-dimensional Brownian motion states:

[ \left\langle \left( x(t) - x_0 \right)^2 \right\rangle = 2Dt ]

This relationship demonstrates that the MSD grows linearly with time in simple diffusion processes [1]. For higher dimensions, this relationship generalizes to:

[ \text{MSD} = 2nDt ]

where (n) represents the number of dimensions [1]. This linear time dependence forms the theoretical basis for extracting diffusion coefficients from experimental or simulation trajectory data.

Table 1: Key Theoretical Relationships for MSD and Diffusion

| Concept | Mathematical Expression | Parameters | Application Context | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MSD Definition | (\text{MSD} \equiv \left\langle \left( x(t) - x_0 \right)^2 \right\rangle) | (x(t)): position at time (t); (x_0): reference position | Fundamental definition for single particle trajectory analysis | ||

| MSD for Multiple Particles | (\frac{1}{N} \sum_{i=1}^{N} \left | \mathbf{x}^{(i)}(t) - \mathbf{x}^{(i)}(0) \right | ^2) | (N): number of particles; (\mathbf{x}^{(i)}(t)): position of particle (i) at time (t) | Experimental analysis of particle ensembles |

| Einstein Relation (1D) | (\left\langle \left( x(t) - x_0 \right)^2 \right\rangle = 2Dt) | (D): diffusion coefficient; (t): time | Determining diffusivity from trajectory data in one dimension | ||

| Einstein Relation (nD) | (\text{MSD} = 2nDt) | (n): dimensionality; (D): diffusion coefficient; (t): time | Determining diffusivity from trajectory data in multiple dimensions | ||

| Diffusion Coefficient Definition | (D = \frac{1}{2d} \lim_{t \to \infty} \frac{d}{dt} \text{MSD}(t)) | (d): dimensionality; MSD(t): mean squared displacement function | Operational definition for calculating (D) from MSD data |

Mathematical Derivation for Brownian Motion

The probability density function (p(x,t|x_0)) for a Brownian particle in one dimension satisfies the diffusion equation:

[ \frac{\partial p(x,t|x0)}{\partial t} = D \frac{\partial^2 p(x,t|x0)}{\partial x^2} ]

with initial condition (p(x,t=0|x0) = \delta(x-x0)) [1]. The solution is a Gaussian distribution:

[ P(x,t) = \frac{1}{\sqrt{4\pi Dt}} \exp \left( -\frac{(x-x_0)^2}{4Dt} \right) ]

which spreads with a full width at half maximum (FWHM) proportional to (\sqrt{t}) [1].

To derive the MSD, we utilize the moment-generating function approach. The characteristic function is defined as:

[ G(k) = \langle e^{ikx} \rangle \equiv \int e^{ikx} P(x,t|x_0) dx ]

For the Gaussian distribution, this evaluates to:

[ G(k) = \exp(ikx_0 - k^2 Dt) ]

The cumulants (\kappa_m) are obtained from the expansion:

[ \ln(G(k)) = \sum{m=1}^{\infty} \frac{(ik)^m}{m!} \kappam ]

yielding (\kappa1 = x0) and (\kappa_2 = 2Dt) [1]. The MSD is then calculated as:

[ \langle (x(t) - x0)^2 \rangle = \kappa2 = 2Dt ]

This confirms the linear relationship between MSD and time that characterizes normal diffusion [1].

Computational and Experimental Protocols

Trajectory Analysis Framework

In single particle tracking (SPT) experiments, displacements are defined for different time intervals between positions (time lags or lag times). For a trajectory sampled at discrete time points (1\Delta t, 2\Delta t, \ldots, N\Delta t), the MSD can be calculated for various time lags using the expression:

[ \overline{\delta^2(n)} = \frac{1}{N-n} \sum{i=1}^{N-n} \left( \vec{r}{i+n} - \vec{r}_i \right)^2, \qquad n = 1, \ldots, N-1 ]

where (\vec{r}_i) denotes the position at time step (i), and (n) represents the lag time in units of the time step [1].

For continuous time series, the MSD is computed as:

[ \overline{\delta^2(\Delta)} = \frac{1}{T-\Delta} \int_0^{T-\Delta} [r(t+\Delta) - r(t)]^2 dt ]

where (T) is the total observation time and (\Delta) is the lag time [1]. Proper implementation requires careful consideration of statistical precision and trajectory length.

MSD Analysis Workflow for Diffusion Coefficient Calculation

Practical Implementation Guidelines

For accurate MSD computation, several critical implementation factors must be addressed. First, when working with simulation data, unwrapped coordinates must be used rather than wrapped coordinates that have been folded back into the primary simulation cell through periodic boundary conditions [6]. This ensures that actual particle displacements are measured rather than artificial movements due to boundary wrapping.

Computationally, the direct calculation of MSD using a "windowed" approach exhibits (N^2) scaling with respect to trajectory length, which can become prohibitive for long trajectories. Implementation of a Fast Fourier Transform (FFT)-based algorithm reduces this to (N \log(N)) scaling, significantly improving computational efficiency [6]. The tidynamics Python package provides such an implementation for trajectory analysis.

When applying the Einstein relation to extract diffusion coefficients, it is crucial to identify the appropriate linear regime of the MSD plot. The initial ballistic regime at short time scales and the poorly averaged region at long time scales should be excluded from the linear fit [6]. A log-log plot of MSD versus time can help identify the true diffusive regime, which appears as a region with slope of 1.

Table 2: Computational Parameters for MSD Analysis

| Parameter | Considerations | Impact on Results | Recommended Practices |

|---|---|---|---|

| Trajectory Length | Statistical precision improves with longer trajectories | Shorter trajectories increase uncertainty in diffusion coefficient | Aim for trajectories where particle moves several times its size |

| Time Step | Too large: aliasing; Too small: correlated positions | Affects identification of diffusive regime | Choose to resolve relevant motion timescales |

| Number of Particles | Ensemble averaging improves statistics | Fewer particles increase statistical uncertainty | Use multiple trajectories when possible for better statistics |

| Lag Time Range | Short times: ballistic regime; Long times: poor statistics | Incorrect range biases diffusion coefficient | Identify linear regime through log-log analysis |

| Coordinate Handling | Wrapped vs. unwrapped coordinates | Critical for simulations with periodic boundaries | Always use unwrapped coordinates for displacement calculation |

| Algorithm Selection | Direct (O(N²)) vs. FFT (O(N log N)) | Computational efficiency for long trajectories | Use FFT-based algorithm for large datasets |

Statistical uncertainty quantification is essential for reliable diffusion coefficient estimation. Block averaging techniques can provide error estimates by dividing trajectories into multiple blocks and computing the variance of diffusion coefficients across blocks [10]. For molecular dynamics simulations, studies have shown that the velocity autocorrelation function (VACF) and MSD methods produce equivalent mean values with similar levels of statistical errors, providing validation through multiple approaches [11].

Data Analysis and Interpretation

Extracting Diffusion Coefficients

The self-diffusivity (D) is obtained from the MSD through the relation:

[ D = \frac{1}{2d} \lim_{t \to \infty} \frac{d}{dt} \text{MSD}(t) ]

where (d) is the dimensionality [6]. In practice, this limit is evaluated by fitting a linear model to the MSD curve in the diffusive regime:

[ \text{MSD}(t) = 2dD \cdot t + C ]

where (C) is a constant. The slope is determined through linear regression, and the diffusion coefficient is calculated as (D = \text{slope} / (2d)) [6].

For example, in a 3D system, the relationship becomes (\text{MSD}(t) = 6D \cdot t), and thus (D = \text{slope} / 6) [6]. The linear segment used for fitting should be carefully selected to exclude both the short-time ballistic regime where particles move with approximately constant velocity (MSD (\propto t^2)) and the long-time region where statistical noise dominates due to insufficient averaging.

Interpreting MSD Curves for Diffusion Coefficient Extraction

Advanced Considerations

Beyond simple diffusion, MSD analysis can reveal more complex transport phenomena. In many biological and soft matter systems, anomalous diffusion is observed where:

[ \text{MSD}(t) \propto t^\alpha ]

with (\alpha < 1) (subdiffusion) common in crowded environments like cells, and (\alpha > 1) (superdiffusion) occurring in active transport processes [12]. The exponent (\alpha) provides insight into the nature of the molecular environment and transport mechanisms.

For systems exhibiting aging phenomena, where dynamics slow down over time, a generalized Einstein relation may be necessary. In such cases, both damping and temperature may decrease with time in power-law forms, requiring modified analysis approaches [12]. This is particularly relevant in glassy systems, granular materials, and complex fluids where traditional equilibrium assumptions break down.

In molecular dynamics simulations, finite-size effects can influence calculated diffusion coefficients. System size corrections, such as those proposed by Yeh and Hummer, may be necessary for accurate results when using periodic boundary conditions [6]. Additionally, the statistical precision of diffusion coefficients can be quantified through analysis of the variance in MSD estimates, with errors typically decreasing as (T^{-1/2}) where (T) is trajectory length [11].

Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Solutions

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Dynamics Engines | VASP, GROMACS, LAMMPS | Generate atomic trajectories through MD simulation | First-principles diffusion calculations from AIMD [10] |

| Trajectory Analysis Libraries | MDAnalysis, tidynamics | Compute MSD and related metrics from trajectory data | Efficient MSD calculation with FFT acceleration [6] |

| Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials | GeNNIP4MD, DP-GEN | Enable accurate MD simulation of complex systems | Diffusion in alloys and complex materials [13] |

| Specialized Analysis Packages | VASPKIT, SLUSCHI-Diffusion | Automated parsing of MD outputs and MSD calculation | High-throughput diffusion screening [10] |

| Uncertainty Quantification Frameworks | Block averaging methods, ANOVA | Statistical error estimation for diffusion coefficients | Reliability assessment of computed diffusivities [11] |

The Einstein relation connecting MSD to diffusion coefficients provides a powerful foundation for analyzing particle dynamics across diverse scientific domains. For researchers in drug development and materials science, proper implementation of MSD analysis requires careful attention to trajectory preprocessing, appropriate algorithm selection, identification of linear diffusive regimes, and rigorous uncertainty quantification. The protocols outlined herein offer a robust framework for extracting reliable diffusion parameters from experimental and computational trajectory data, enabling insights into transport phenomena in systems ranging from simple fluids to complex biological environments. As trajectory analysis methodologies continue to advance, particularly through machine learning approaches and enhanced computational efficiency, the Einstein relation remains an essential tool in the quantitative analysis of stochastic processes.

Mean Squared Displacement (MSD) analysis serves as a cornerstone technique in the quantitative assessment of particle motion, providing critical insights into diffusion characteristics, directed transport, and confinement phenomena across diverse scientific domains. In statistical mechanics, MSD measures the deviation of a particle's position from a reference point over time, effectively quantifying the spatial extent of random motion and the portion of a system explored by a random walker [1]. This measure has become indispensable in biophysics and environmental engineering for determining whether particle spreading results primarily from diffusion or involves additional advective forces [1]. The fundamental definition of MSD for an ensemble of N particles at time t is expressed as MSD ≡ ⟨|x(t) - xâ‚€|²⟩ = (1/N)∑|xâ½â±â¾(t) - xâ½â±â¾(0)|², where xâ½â±â¾(0) represents the reference position for each particle i [1].

The power of MSD analysis extends beyond simple diffusion measurement, enabling researchers to classify different modes of motion through the relationship MSD(τ) = Γ·τᵅ, where the exponent α serves as a critical indicator of motion type [14]. When α = 1, particles undergo normal Brownian diffusion; α > 1 indicates superdiffusive motion consistent with directed transport; and α < 1 signifies subdiffusive behavior characteristic of confined movement [14] [4]. This mathematical framework provides researchers with a powerful tool for interpreting the underlying physical mechanisms governing particle dynamics in complex environments, from cellular interiors to synthetic materials.

Theoretical Foundations of MSD

Mathematical Formalism and Key Equations

The theoretical underpinnings of MSD analysis derive from the fundamental principles of Brownian motion, where the probability density function (PDF) for a particle's position follows a diffusion equation. In one dimension, this relationship is described by ∂p(x,t|x₀)/∂t = D∂²p(x,t|x₀)/∂x², with the initial condition p(x,t=0|x₀) = δ(x-x₀) [1]. The solution yields the familiar Gaussian distribution P(x,t) = (1/√(4πDt))exp(-(x-x₀)²/(4Dt)), which demonstrates that the distribution width increases proportionally to √t [1]. From this foundation, the MSD is defined as ⟨(x(t)-x₀)²⟩, which simplifies to 2Dt for one-dimensional Brownian motion [1].

For n-dimensional Euclidean space, the probability distribution becomes the product of fundamental solutions in each variable: P(x,t) = P(xâ‚,t)P(xâ‚‚,t)...P(xâ‚™,t) = 1/√((4Ï€Dt)â¿)exp(-x·x/(4Dt)) [1]. Consequently, the MSD in n dimensions becomes the sum of individual coordinate displacements: MSD = ⟨(xâ‚(t)-xâ‚(0))²⟩ + ⟨(xâ‚‚(t)-xâ‚‚(0))²⟩ + ⋯ + ⟨(xâ‚™(t)-xâ‚™(0))²⟩ = 2nDt [1]. This mathematical formalism establishes the fundamental relationship between MSD and diffusion coefficients across spatial dimensions.

MSD Computation Methods

In practical applications, MSD can be computed using different averaging approaches, each with distinct advantages. The ensemble-average MSD calculates displacement from initial positions: ⟨x²(t)⟩ = ⟨(x(t) - x(0))²⟩ [4]. Alternatively, the time-averaged MSD measures displacement over all possible time lags Ï„: x²(Ï„) = (1/(T-Ï„))∫₀ᵀâ»Ï„(x(t+Ï„)-x(t))²dt, where T represents the total trajectory length [1] [4]. For experimental single-particle tracking (SPT) data with discrete time points, this becomes δ²(n) = (1/(N-n))∑(r⃗ᵢ₊ₙ - r⃗ᵢ)² for n=1,...,N-1, where N denotes the number of frames and Δt is the time between frames [1].

Table 1: MSD Computation Methods and Their Characteristics

| Method | Formula | Applications | Advantages/Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ensemble-Average MSD | ⟨x²(t)⟩ = ⟨(x(t) - x(0))²⟩ | Systems with multiple simultaneous trajectories | Provides population statistics; Limited by number of trajectories |

| Time-Averaged MSD | x²(Ï„) = (1/(T-Ï„))∫₀ᵀâ»Ï„(x(t+Ï„)-x(t))²dt | Long single-particle trajectories | Improved statistics from single trajectory; Requires ergodicity |

| Windowed MSD | δ²(n) = (1/(N-n))∑(r⃗ᵢ₊ₙ - r⃗ᵢ)² | Single-particle tracking with discrete time points | Maximizes samples for all lag times; Computationally intensive |

The computational implementation of MSD analysis requires careful consideration of algorithms and memory requirements. While a straightforward "windowed" approach exhibits O(N²) scaling with trajectory length, Fast Fourier Transform (FFT)-based algorithms can reduce this to O(N log N) scaling [6]. However, these computational efficiencies require specialized packages and careful handling of trajectory data, particularly ensuring coordinates follow an unwrapped convention where particles crossing periodic boundaries are not artificially returned to the primary simulation cell [6].

Classifying Motion Modes Through MSD Signatures

Characteristic MSD Profiles for Different Motion Types

The temporal evolution of MSD provides distinctive signatures that enable classification of motion modes, with the exponent α in the relationship MSD(τ) = Kᵅτᵅ serving as the primary diagnostic parameter [14] [4]. Normal Brownian motion exhibits linear MSD growth with α = 1, where the slope is directly proportional to the diffusion coefficient as MSD = 2nDτ for n dimensions [1] [4]. This linear relationship reflects the random, memoryless nature of Brownian motion and represents the baseline against which anomalous diffusion is identified.

Directed motion with a constant velocity component produces superdiffusive behavior characterized by α > 1, specifically MSD(τ) = 4Dτ + v²τ² for two-dimensional motion with drift velocity v [14]. The quadratic term dominates at longer time scales, creating an upward-curving MSD profile that distinguishes active transport from passive diffusion. Conversely, confined motion exhibits subdiffusive characteristics with α < 1, eventually plateauing as particles explore their restricted environment [14] [15]. The confinement radius R directly influences this plateau value, with MSD approaching a constant proportional to R² at long time scales.

Table 2: Characteristic MSD Signatures for Different Motion Types

| Motion Type | MSD Equation | Exponent (α) | Physical Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Normal Diffusion | MSD(Ï„) = 2nDÏ„ | 1 | Random thermal motion in homogeneous environment |

| Subdiffusion (Confined) | MSD(τ) ≈ Kᵅτᵅ (α<1), plateaus at ~R² | <1 | Motion restricted by structural barriers or binding |

| Superdiffusion (Directed) | MSD(τ) = 4Dτ + v²τ² (2D) | >1 | Active transport with directional component |

| Anomalous Diffusion | MSD(τ) = Kᵅτᵅ | ≠1 | Complex environments with memory effects or crowding |

Advanced Classification Using Hidden Variable Models

While MSD curve analysis provides initial motion classification, advanced methods incorporating hidden variable models offer enhanced discrimination capabilities, particularly for complex biological environments. The aTrack tool exemplifies this approach, using a probabilistic framework that accounts for localization error, true particle positions, and anomalous parameters such as potential well centers for confined motion or velocity vectors for directed motion [14]. This model employs analytical recurrence formulas to efficiently compute likelihoods for different motion categories, enabling robust statistical comparisons through likelihood ratio tests [14].

The classification certainty in these advanced methods depends critically on track length and the strength of the anomalous parameter [14]. For confined motion, significance increases with both track length and confinement factor, while for directed motion, significance grows with track length and velocity magnitude [14]. These relationships highlight the importance of experimental design and data quality in accurately classifying motion modes, with longer trajectories providing substantially improved classification reliability, particularly for weakly confined or slowly driven systems.

Experimental Protocols for MSD Analysis

Sample Preparation and Data Acquisition

Proper sample preparation and data acquisition form the foundation for reliable MSD analysis. For intracellular tracking, fluorescent probes such as quantum dots, colloidal gold particles, or fluorescently labeled proteins must be introduced to the cellular environment with minimal disruption to native functions [15]. Nerve growth factor-quantum dot (NGF-QD) probes represent one effective approach, prepared using biotin-streptavidin conjugation and incubated with cultured cells under physiological conditions [15]. For synthetic systems, fluorescent beads or labeled molecules dispersed in the medium of interest provide suitable probes for tracking experiments.

Image acquisition should utilize high-sensitivity cameras (e.g., electron-multiplied charge-coupled devices) on inverted microscopes with high-numerical-aperture objectives (e.g., 100×, 1.4 NA) [15]. A typical acquisition rate of 16.7 frames/second provides sufficient temporal resolution for many intracellular processes, though this should be optimized based on expected particle velocities [15]. For sufficient statistical power, aim to capture trajectories with at least 50-100 steps, recognizing that classification certainty improves significantly with longer tracks [14]. Maintain consistent focus and environmental control throughout acquisition to minimize experimental artifacts.

Trajectory Reconstruction and Preprocessing

Trajectory reconstruction begins with identifying particle positions in each frame using algorithms that determine centroid positions with sub-pixel accuracy [15]. Customized versions of publicly available MATLAB scripts implementing established methods can effectively link positions into trajectories [15]. The resulting trajectories r⃗(t) = [x(t), y(t)] form the raw data for subsequent analysis [1]. Position measurement uncertainty σₘ can be estimated using the correlation between adjacent displacements: σₘ² = -⟨ΔxᵢΔxᵢ₊â‚⟩, typically ranging from ±20 nm to ±50 nm for quality trajectories [15].

Critical preprocessing involves ensuring coordinates follow an unwrapped convention, where particles crossing periodic boundaries are not artificially wrapped back into the primary simulation cell [6]. Various simulation packages provide utilities for this conversion (e.g., in GROMACS, use gmx trjconv with the -pbc nojump flag) [6]. For confined motion analysis, additional preprocessing may involve identifying trajectory segments that remain within specific cellular compartments or regions of interest based on additional labeling or morphological information.

MSD Calculation and Motion Classification Protocol

The step-by-step protocol for MSD calculation and motion classification proceeds as follows:

Data Preparation: Load trajectory data, ensuring coordinates represent unwrapped positions. For molecular dynamics trajectories, use appropriate tools to remove periodic boundary effects [6].

MSD Calculation: Compute the time-averaged MSD for each trajectory using the discrete formula δ²(n) = (1/(N-n))∑(r⃗ᵢ₊ₙ - r⃗ᵢ)² for n = 1,...,N-1, where N is the trajectory length [1]. For better statistics, use FFT-based algorithms when possible [6].

Power Law Fitting: Fit the MSD curve to the equation MSD(τ) = Γ·τᵅ over an appropriate time lag range. The linear region typically represents the diffusive regime, avoiding both ballistic motion at short times and poorly averaged regions at long times [6] [4].

Motion Classification: Categorize motion based on the exponent α: α ≈ 1 indicates normal diffusion; α < 1 suggests confined motion; α > 1 implies directed motion [14] [4].

Parameter Extraction: For normal diffusion, calculate the diffusion coefficient D from the slope of the linear MSD region using D = (1/(2n))·d(MSD)/dt, where n is the dimensionality [6] [4]. For directed motion, extract velocity from the quadratic coefficient. For confined motion, determine the confinement radius from the MSD plateau value.

Statistical Validation: Use hidden variable models like aTrack for likelihood ratio tests to statistically validate motion classification, particularly for ambiguous cases [14]. Compare the maximum likelihood assuming Brownian diffusion (null hypothesis) versus confined or directed motion (alternative hypotheses) [14].

Experimental Reagents for Single-Particle Tracking

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for SPT and MSD Analysis

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Fluorescent Probes | Quantum dots (NGF-QDs), colloidal gold particles, fluorescent beads, single fluorescent molecules | Visualizing particle motion with high photon yield and photostability |

| Bioconjugation Tools | Biotin-streptavidin systems, NHS-ester chemistry, click chemistry | Attaching fluorescent probes to proteins or molecules of interest |

| Cell Culture Materials | PC12 cells, appropriate growth media, extracellular matrix components | Maintaining physiological environments for intracellular tracking |

| Imaging Reagents | Immersion oil, fluorescent calibration standards, oxygen scavenging systems | Optimizing and maintaining image quality during acquisition |

Computational Tools and Software Packages

Effective MSD analysis requires specialized computational tools that implement the algorithms discussed previously. MDAnalysis provides a robust Python package for analyzing molecular dynamics trajectories, including the EinsteinMSD class for calculating MSD with either standard or FFT-based algorithms [6]. This tool requires trajectory data in unwrapped format and offers flexibility in selecting spatial dimensions for MSD computation (xyz, xy, x, y, z, etc.) [6].

The aTrack software represents a specialized tool for classifying track behaviors and extracting parameters for particles undergoing Brownian, confined, or directed motion [14]. This package uses hidden variable models and analytical recurrence formulas to efficiently compute likelihoods for different motion categories, providing statistical confidence in classification [14]. For custom analyses, the msd.py script from LLC-Membranes implements both ensemble-averaged and time-averaged MSD calculations, with options for bootstrap error estimation and power law fitting [4].

Additional specialized tools include tidynamics for FFT-accelerated MSD calculations and various MATLAB implementations of single-particle tracking algorithms publicly available from university research groups [15]. These computational resources collectively enable researchers to progress from raw trajectory data to quantitatively classified motion modes with statistical validation.

Applications in Drug Development and Biological Research

MSD analysis provides critical insights in drug development by quantifying how therapeutic compounds affect intracellular trafficking, membrane dynamics, and molecular interactions. By characterizing the transition between diffusion, directed motion, and confinement, researchers can identify how drug treatments alter fundamental cellular processes. For instance, MSD analysis can reveal how cancer therapeutics affect motor-driven transport of organelles or how membrane receptor dynamics change in response to targeted therapies.

In neurological drug development, MSD analysis of nerve growth factor (NGF) trafficking provides insights into axonal transport mechanisms and their impairment in neurodegenerative diseases [15]. The ability to distinguish between normal diffusion, subdiffusive behavior indicating cytoskeletal interactions, and directed motion along microtubules enables researchers to identify specific points of intervention for therapeutic compounds. Similarly, in immunology, MSD analysis of T-cell receptor dynamics on membrane surfaces informs the development of immunomodulatory drugs.

The application of advanced classification tools like aTrack enables biosensing applications where particle motion serves as a reporter for specific molecular interactions or environmental properties [14]. By detecting confined motion indicative of binding events or directed motion suggesting active transport, these approaches can identify specific biochemical interactions relevant to drug mechanisms. Furthermore, characterizing confinement parameters provides insights into the nanostructure of cellular environments, potentially revealing how drug treatments alter subcellular organization.

MSD analysis represents a powerful framework for interpreting particle motion modes, transforming raw trajectory data into quantitative insights about diffusion, directed transport, and confinement. The characteristic temporal evolution of MSD provides distinct signatures for different motion types, while advanced statistical approaches using hidden variable models enable robust classification even in complex biological environments. Following standardized protocols for data acquisition, trajectory processing, and MSD calculation ensures reliable, reproducible results across experimental systems.

As trajectory analysis continues to evolve, MSD remains a fundamental tool for researchers investigating dynamics from molecular to cellular scales. In drug development specifically, the ability to quantitatively classify motion modes provides critical insights into therapeutic mechanisms and cellular responses. By implementing the principles and protocols outlined in this article, researchers can leverage MSD analysis to advance understanding of complex biological systems and develop more effective therapeutic interventions.

The analysis of particle trajectories via Mean Squared Displacement (MSD) is a cornerstone technique in biophysics and materials science, providing critical insights into the dynamic behavior of molecules, nanoparticles, and other entities in complex environments. This protocol focuses on the precise extraction of two fundamental parameters: the diffusion coefficient (D), which quantifies the mobility of a particle, and the anomalous exponent (α), which characterizes the nature of the diffusion process. Within the broader context of trajectory analysis tools for MSD research, accurately determining these parameters is essential for researchers and drug development professionals studying phenomena such as drug delivery mechanisms, intracellular transport, and membrane dynamics. The following sections provide a detailed framework for performing this analysis, from theoretical foundations to practical implementation and troubleshooting.

Theoretical Foundation

The movement of a particle is typically characterized by its Mean Squared Displacement, which describes the average squared distance a particle travels over time. For normal Brownian motion in an unrestricted, homogeneous medium, the MSD increases linearly with time. However, in complex environments like those found inside living cells or within polymeric materials, diffusion often becomes "anomalous," following a non-linear power-law relationship [2].

The fundamental equation governing this behavior is: [ \text{MSD}(\tau) = 2d D \tau^{\alpha} ] where:

- (\tau) is the lag time (the time interval over which displacement is measured)

- (d) is the dimensionality of the trajectory (e.g., 2 for 2D data, 3 for 3D data)

- (D) is the generalized diffusion coefficient (with units m²/sᵅ)

- (\alpha) is the anomalous exponent [16] [2]

The anomalous exponent reveals crucial information about the mode of particle motion, which can be classified as follows:

Table 1: Classification of Diffusion Modes by Anomalous Exponent

| Anomalous Exponent (α) | Diffusion Mode | Physical Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| α = 1 | Normal/Brownian | Unrestricted, random motion in a homogeneous environment |

| α < 1 | Subdiffusive | Movement impeded by obstacles, binding events, or crowding |

| α > 1 | Superdiffusive | Directed motion with active transport components |

The diffusion coefficient D provides a measure of mobility independent of the specific diffusion mode, with higher values indicating faster particle movement. In experimental single-particle tracking (SPT) data, the time-averaged MSD (TA-MSD) is commonly calculated for individual trajectories, providing an estimate of the expected MSD behavior [2].

Experimental Protocols

Prerequisites and Data Requirements

Accurate parameter extraction requires high-quality trajectory data. The following reagents and computational tools are essential for successful implementation:

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for MSD Analysis

| Item | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| Single-Particle Tracking Software | Tools like TrackMate (Fiji), Icy, or custom MATLAB/Python trackers for reconstructing particle trajectories from microscopy image sequences [17] |

| Unwrapped Trajectories | Particle coordinates that have not been corrected for periodic boundary conditions (e.g., using gmx trjconv -pbc nojump in GROMACS for simulation data) [18] |

| MSD Analysis Software | Specialized tools such as @msdanalyzer (MATLAB class), MDAnalysis.analysis.msd (Python), or custom scripts implementing FFT-based algorithms [18] [17] |

| Trajectory Data | Time-series of particle positions with consistent temporal sampling (Δt); optimal lengths of 100-1000 frames depending on required precision [19] |

Core Protocol: Extracting D and α from Trajectories

Step 1: Calculate the Time-Averaged Mean Squared Displacement (TA-MSD) For a single trajectory with N positions recorded at constant time intervals Δt, the TA-MSD is computed for multiple lag times τ (where τ = nΔt, with n = 1, 2, 3, ..., N-1) using the formula [19]: [ \text{TA-MSD}(\tau) = \frac{1}{N-\tau} \sum{i=1}^{N-\tau} \left[ (\vec{r}(ti + \tau) - \vec{r}(ti))^2 \right] ] where (\vec{r}(ti)) represents the particle's position vector at time (ti). For two-dimensional data (common in microscopy), this expands to: [ \text{TA-MSD}(\tau) = \frac{1}{N-\tau} \sum{i=1}^{N-\tau} \left[ (x{i+\tau} - xi)^2 + (y{i+\tau} - yi)^2 \right] ]

Step 2: Transform to Log-Log Space The power-law relationship between MSD and time becomes linear in log-log space: [ \log(\text{TA-MSD}(\tau)) \approx \alpha \log(\tau) + \log(2dD) ] This transformation enables the use of linear regression to extract the parameters α and D [19].

Step 3: Perform Linear Regression Fit a straight line to the log(TA-MSD) versus log(Ï„) data using ordinary least squares regression: [ \log(\text{TA-MSD}(\tau)) = \alpha \cdot \log(\tau) + C ] where:

- The slope of the line provides the estimate for the anomalous exponent α

- The y-intercept (C) relates to the diffusion coefficient through (D = \frac{e^C}{2d})

Step 4: Calculate the Diffusion Coefficient Using the intercept (C) from the linear fit and the dimensionality (d), compute: [ D = \frac{e^C}{2d} ] Ensure proper unit conversion based on your spatial and temporal calibration.

The following workflow diagram illustrates the complete analytical process:

Protocol for Ensemble Analysis

When multiple trajectories are available (a common scenario in experimental studies), ensemble approaches significantly improve parameter estimation accuracy, particularly for short trajectories [19].

Step 1: Calculate Ensemble-Averaged MSD For M trajectories, compute the time-ensemble averaged MSD (TEA-MSD): [ \text{TEA-MSD}(\tau) = \frac{1}{M} \sum{j=1}^{M} \text{TA-MSD}j(\tau) ]

Step 2: Apply Log-Log Transformation and Linear Regression Follow the same procedure as for single trajectories, but using the TEA-MSD values: [ \log(\text{TEA-MSD}(\tau)) \approx \alpha \cdot \log(\tau) + C ]

Step 3: Correct Individual Trajectory Estimates Use the ensemble statistics to refine estimates from individual trajectories through variance-based shrinkage correction [19]: [ \alpha{\text{corrected}} = w \cdot \alpha{\text{individual}} + (1-w) \cdot \alpha_{\text{ensemble}} ] where the weight (w) depends on trajectory length and the known variance characteristics of the estimator.

Critical Considerations and Troubleshooting

Common Experimental Challenges

Finite-Trajectory Effects Short trajectories lead to significant statistical uncertainty in parameter estimates. The variance of the estimated anomalous exponent is inversely proportional to trajectory length T [19]: [ \text{Var}[\hat{\alpha}] \propto \frac{1}{T} ] For trajectories shorter than 20-30 points, consider ensemble methods or specialized correction approaches [19].

Localization Error Measurement uncertainty in particle position creates a constant offset in the MSD at short time lags, leading to systematic underestimation of α. The effect can be modeled as: [ \text{MSD}(\tau) = 2dD\tau^{\alpha} + 2\sigma^2 ] where (\sigma^2) is the localization variance. To minimize this effect, exclude the first few lag times from the linear regression or use specialized fitting models that incorporate the error term explicitly.

Optimal Lag Time Selection The number of lag times (Ï„) used in the linear regression significantly impacts parameter accuracy. Using too many lag times increases statistical uncertainty, while using too few reduces sensitivity. As a practical guideline:

- Use approximately Ï„_max = N/10 to N/4, where N is trajectory length

- For very short trajectories (N < 20), limit to Ï„_max = 4-5

- Consistently apply the same lag time selection across all analyses for comparative studies

Validation and Quality Control

Linearity Assessment Before accepting parameter estimates, validate the linearity of the log(MSD) versus log(τ) relationship by calculating the coefficient of determination (R²). Values below 0.9 typically indicate poor fit quality, potentially due to:

- Mixed diffusion modes within a single trajectory

- Insufficient trajectory length

- Significant localization errors

Statistical Uncertainty Quantification For rigorous reporting, calculate confidence intervals for estimated parameters using: [ \text{SE}(\hat{\alpha}) = \sqrt{\frac{1}{T \sum_{\tau=1}^{K} (\log(\tau) - \overline{\log(\tau)})^2}} ] where K is the number of lag times used in the regression [19].

The following decision diagram guides troubleshooting common issues:

Data Presentation Standards

Parameter Reporting

When publishing results obtained through these protocols, include the following essential information:

Table 3: Essential Parameters for Reporting MSD Analysis Results

| Parameter | Description | Example Value |

|---|---|---|

| Trajectory Count (M) | Number of trajectories analyzed | 145 |

| Mean Trajectory Length (N) | Average number of points per trajectory | 42.5 ± 18.2 |

| Lag Time Range | Specific Ï„ values used in regression | Ï„ = 1-10 frames |

| Anomalous Exponent (α) | Mean ± standard error across ensemble | 0.76 ± 0.04 |

| Diffusion Coefficient (D) | Geometric mean with 95% confidence interval | 0.42 [0.38-0.47] μm²/sᵅ |

| Fit Quality (R²) | Average coefficient of determination | 0.94 |

Advanced Applications

For complex systems exhibiting heterogeneous populations of D and α values, recent methodological advances enable the resolution of underlying parameter distributions. The joint distribution (p(\hat{\alpha}, \hat{D})) of estimated parameters can be modeled as [16]: [ p(\hat{\alpha}, \hat{D}) = \int{0}^{2} d\alpha \int{0}^{\infty} dD \, p(\hat{\alpha}, \hat{D}|\alpha,D) p(\alpha,D) ] where (p(\hat{\alpha}, \hat{D}|\alpha,D)) is a transfer function characterizing estimation uncertainty. This approach is particularly valuable for identifying distinct subpopulations in heterogeneous systems like biological membranes or polymer composites.

The precise extraction of diffusion coefficients and anomalous exponents from particle trajectories provides fundamental insights into the physical properties of complex systems. The protocols outlined here establish a robust framework for this analysis, emphasizing the importance of proper data preprocessing, appropriate lag time selection, and rigorous statistical validation. For researchers in drug development, these methods enable the characterization of therapeutic nanoparticle mobility in biological environments, the study of membrane protein dynamics, and the assessment of macromolecular crowding effects. By implementing these standardized protocols and addressing common experimental challenges through the provided troubleshooting guidelines, researchers can generate reliable, reproducible parameters that effectively describe diffusive behavior across diverse experimental systems.

The Critical Role of MSD in Single-Particle Tracking (SPT) Studies

The Mean Squared Displacement (MSD) analysis serves as a cornerstone technique in the quantitative interpretation of single-particle tracking (SPT) data. It transforms raw trajectory coordinates into meaningful parameters that describe the nature and characteristics of particle motion [2]. In biological research and drug development, SPT enables the investigation of molecular dynamics at the single-molecule level, providing insights into heterogeneous processes that are often obscured in ensemble-averaged measurements [20] [21]. The MSD function quantitatively describes the spatial exploration of a particle over time, making it an indispensable tool for classifying motion types and extracting critical biophysical parameters.

The fundamental principle of MSD analysis lies in its ability to quantify the average squared distance a particle travels over specific time intervals, thereby revealing the statistical properties of its motion [2]. This analysis is particularly valuable in live-cell imaging studies, where it helps researchers decipher complex diffusion behaviors resulting from interactions with cellular components, confinement in organelles, or active transport processes [20] [22]. The application of MSD analysis spans diverse fields including virology (tracking viral entry pathways), membrane biology (studying receptor dynamics), and cytoplasmic transport (characterizing rheological properties) [22] [23].

Theoretical Foundations of MSD Analysis

Mathematical Formalism

For a single trajectory represented as a time series of positions ( \vec{x}0, \vec{x}1, \ldots, \vec{x}_N ) sampled at time intervals ( \Delta t ), the most common form of MSD calculation is the time-averaged MSD (T-MSD). It is computed directly from an individual trajectory using the formula:

[ \text{T-MSD}(n\Delta t) = \frac{1}{N - n + 1} \sum{i=0}^{N-n} \left| \vec{x}{i+n} - \vec{x}_{i} \right|^2 ]

where ( n ) is the time lag index, ( N ) is the total number of positions in the trajectory, and ( \left| \vec{x}{i+n} - \vec{x}{i} \right|^2 ) represents the squared displacement between frames separated by ( n ) steps [2] [21]. This approach is particularly valuable for detecting heterogeneity in motion behavior within single trajectories.

For analysis of multiple trajectories, the ensemble-averaged MSD can be calculated by averaging displacements across all particles at each time lag, while the time- and ensemble-averaged MSD (TEAMSD) combines both approaches to improve statistical reliability [2].

MSD Profiles for Motion Type Classification

The functional form of the MSD curve reveals fundamental information about the mode of particle motion. For Brownian (normal) diffusion in two dimensions, the MSD increases linearly with time lag:

[ \text{MSD}(\tau) = 4D\tau ]

where ( D ) is the diffusion coefficient and ( \tau ) is the time lag [2]. Different motion mechanisms produce characteristic MSD profiles that serve as fingerprints for classification:

- Confined diffusion: The MSD curve reaches a plateau at longer time scales, reflecting the finite space accessible to the particle.

- Directed motion: The MSD exhibits a parabolic curvature due to a persistent velocity component.

- Anomalous diffusion: The MSD follows a power-law scaling ( \text{MSD}(\tau) = 4D_\alpha \tau^\alpha ) where the anomalous exponent ( \alpha ) quantifies deviation from normal diffusion (( \alpha < 1 ) for subdiffusion, ( \alpha > 1 ) for superdiffusion) [2].

The table below summarizes the characteristic MSD profiles for different diffusion types:

Table 1: Characteristic MSD profiles for different diffusion types

| Motion Type | MSD Profile | Anomalous Exponent (α) | Physical Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Normal Diffusion | (\text{MSD}(\tau) = 4D\tau) | α ≈ 1 | Unhindered random motion in a homogeneous environment |

| Subdiffusion | (\text{MSD}(\tau) = 4D_\alpha\tau^\alpha) | α < 1 | Motion hindered by obstacles, crowding, or temporary binding |

| Superdiffusion | (\text{MSD}(\tau) = 4D_\alpha\tau^\alpha) | α > 1 | Active transport or motion with directional persistence |

| Confined Diffusion | (\text{MSD}(\tau) = R_c^2(1 - A\exp(-B\tau))) | Apparent α → 0 at long τ | Motion restricted to a limited domain or compartment |

| Directed Motion | (\text{MSD}(\tau) = 4D\tau + (v\tau)^2) | N/A | Combination of diffusion and active transport with velocity v |

Experimental Considerations and Corrections

In practical applications, the measured MSD is influenced by experimental artifacts that require correction for accurate parameter estimation. The complete model for normal diffusion incorporating these factors becomes:

[ \text{MSD}(\tau) = 4D\tau + 4(\sigma^2 - 2RD\Delta t) ]

where ( \sigma ) represents the localization error due to photon-counting noise, and ( R ) is the motion blur coefficient accounting for movement during camera exposure [21]. The value of ( R ) ranges from 0 (no motion blur) to 1/4, with ( R = 1/6 ) typically used when exposure time equals the frame interval [21].

Table 2: Key experimental parameters affecting MSD analysis

| Parameter | Impact on MSD | Typical Values | Correction Strategies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Localization Error (σ) | Adds constant offset to MSD | 10-50 nm, depending on SNR | Incorporate in fitting model [21] |

| Motion Blur Coefficient (R) | Reduces MSD intercept | 0-0.25 (typically 1/6) | Include in diffusion model [21] |

| Trajectory Length | Affects statistical reliability | Optimal: >100 points; Minimum: 10 points [24] | Use appropriate fitting range (typically ¼-½ of track length) |

| Time Resolution (Δt) | Limits shortest observable dynamics | 1-100 ms for biological SPT | Match to expected diffusion timescales |

Experimental Protocols for MSD Analysis

Protocol 1: Basic MSD Calculation and Diffusion Coefficient Estimation

This protocol outlines the standard procedure for calculating MSD and extracting diffusion parameters from single-particle trajectories, suitable for initial characterization of particle motion.

Materials and Reagents:

- Trajectory data (x,y,(z) coordinates over time)

- Computational software (MATLAB, Python, or specialized tools like DiffusionLab)

- Custom scripts or built-in functions for MSD calculation

Procedure:

- Trajectory Pre-processing: Import trajectory data, ensuring consistent time intervals between frames. Filter out trajectories shorter than 10 frames, as these provide insufficient data points for reliable MSD analysis [24].

- MSD Calculation: For each trajectory, compute the time-averaged MSD using the standard algorithm:

- Fitting Range Selection: Determine the appropriate number of MSD points for fitting. For trajectories longer than 100 frames, use the first 10 time increments; for shorter trajectories, use approximately one-quarter of the track length [24].

- Model Fitting: Fit the MSD curve to the appropriate model based on the observed profile:

- For normal diffusion: Fit MSD(Ï„) = 4DÏ„ + C to the initial linear region

- For anomalous diffusion: Fit MSD(τ) = 4Dατα + C to the initial region where C incorporates localization error and motion blur effects.

- Parameter Extraction: Extract the diffusion coefficient (D) or anomalous exponent (α) from the fitted parameters. Apply error thresholds for quality control (typically ±0.05 μm²/s for D, ±0.15 for α) [24].

- Validation: Plot MSD curves with confidence intervals when possible. For heterogeneous samples, classify trajectories into subpopulations based on their diffusion characteristics before ensemble averaging.

Troubleshooting Tips:

- Non-linear MSD curves at short time lags may indicate significant localization error.

- MSD curves that decrease at long time lags suggest insufficient trajectory length or statistical artifacts.

- For particles with multiple diffusion states, consider segmentation approaches before MSD analysis.

Protocol 2: Motion Type Classification via MSD Profile Analysis

This protocol describes a systematic approach for classifying particle motion types through quantitative analysis of MSD profiles, enabling identification of heterogeneous behaviors in complex biological environments.

Materials and Reagents:

- Trajectory dataset with minimal drift artifacts

- MSD analysis software with curve-fitting capabilities (Custom scripts, DiffusionLab, or DeepSPT)

- Statistical analysis toolkit for population analysis

Procedure:

- Trajectory Quality Control: Apply stringent filters to ensure data quality:

- Exclude trajectories with fewer than 20 localization points

- Remove trajectories showing apparent drift not attributable to biological motion

- Verify localization precision through stationary particle measurements

- MSD Calculation: Compute MSD curves for all qualified trajectories using the standard method outlined in Protocol 1.

- Model Selection and Fitting: Fit each MSD curve to multiple diffusion models:

- Linear model (normal diffusion): MSD(Ï„) = 4DÏ„

- Power-law model (anomalous diffusion): MSD(τ) = 4Dατα

- Confined diffusion model: MSD(τ) = Rc²[1 - A1exp(-4A2τ/Rc²)]

- Directed motion model: MSD(τ) = 4Dτ + (vτ)²

- Model Selection: Use statistical criteria (e.g., adjusted R², Akaike Information Criterion) to identify the best-fitting model for each trajectory.

- Classification Thresholding: Apply established thresholds to categorize motion types:

- Immobile: D < 0.01 μm²/s

- Brownian: D ≥ 0.01 μm²/s and 0.75 ≤ α ≤ 1.25

- Subdiffusive: D ≥ 0.01 μm²/s and α < 0.75

- Superdiffusive: D ≥ 0.01 μm²/s and α > 1.25 [2]

- Population Analysis: Calculate the proportion of trajectories in each motion class and compute average diffusion parameters for each population separately.

- Visualization: Generate scatter plots of D versus α to visually assess population heterogeneity, or create histograms of diffusion parameters.

Advanced Applications:

- For trajectories exhibiting multiple motion states, apply changepoint detection algorithms to segment trajectories before MSD analysis.

- Implement machine learning classifiers (random forests, neural networks) for automated motion type recognition when large training datasets are available [2] [22].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the complete MSD-based analysis pipeline for motion type classification:

Advanced Applications in Drug Development and Biological Research

Cytoplasmic Diffusion Studies Using Genetically Encoded Nanoparticles

MSD analysis has proven invaluable for characterizing intracellular environments through the tracking of genetically encoded multimeric nanoparticles (GEMs). These 40-nm particles serve as probes for cytoplasmic rheology, mimicking the size of ribosomes and large protein complexes [23]. Recent studies employing inducible expression systems have revealed that measured GEM diffusivity increases as expression levels decrease, highlighting how molecular crowding influences nanoparticle mobility [23]. Through careful MSD analysis corrected for localization errors, researchers have quantified how cytoplasmic viscosity and architecture impact the diffusion of drug-sized particles, providing critical insights for nanomedicine design and intracellular delivery strategies.

The power-law relationship between MSD and time lag (( \text{MSD}(\tau) = 4D_\alpha\tau^\alpha )) has been particularly useful for distinguishing between different cytoplasmic compartments and physiological states. By applying MSD analysis to GEM trajectories, researchers have identified subdiffusive behavior (( \alpha < 1 )) as a common characteristic of cytoplasmic transport, arising from both crowding effects and transient binding interactions [23]. These findings directly inform drug development by elucidating the physical barriers that therapeutic nanoparticles encounter inside cells.

Viral Entry Pathway Mapping

Deep learning frameworks like DeepSPT have integrated MSD analysis with pattern recognition to map viral entry pathways in live cells [22]. By segmenting single-particle trajectories based on diffusional behavior changes detected through MSD profiles, researchers have automatically identified critical infection events such as endosomal escape with F1 scores exceeding 80% [22]. The MSD analysis enables discrimination between free diffusion in the cytosol (( \alpha \approx 1 )), confined motion within endosomes (( \alpha \approx 0 )), and directed transport along cytoskeletal elements.

This application demonstrates how MSD-derived parameters serve as inputs for machine learning classifiers that predict biological states from diffusion characteristics alone. The approach has successfully identified endosomal organelles, clathrin-coated pits, and vesicles with high accuracy, significantly accelerating the analysis of viral infection mechanisms that would otherwise require weeks of manual annotation [22]. For antiviral drug development, this MSD-based profiling offers a rapid screening platform for compounds that alter viral entry pathways.

Membrane Receptor Dynamics and Drug Targeting

SPT combined with MSD analysis has revealed heterogeneous diffusion of membrane receptors, distinguishing between transient confinement in nanodomains, free diffusion, and cytoskeleton-directed motion [2]. These motion characteristics reflect specific molecular interactions that can be modulated by drug candidates. For example, GABA_B receptor dynamics classified through MSD analysis have revealed how receptor activation and dimerization states influence diffusion patterns [2].

The following diagram illustrates how different biological structures and interactions produce characteristic MSD profiles:

Computational Tools for MSD Analysis

The growing sophistication of SPT studies has spurred development of specialized software tools implementing MSD analysis with various enhancements. The table below summarizes key available platforms:

Table 3: Software tools for MSD analysis in single-particle tracking studies

| Tool Name | Primary Features | MSD Implementation | Specialized Capabilities | Accessibility |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DiffusionLab | GUI-based trajectory classification | T-MSD with motion blur correction | Feature-based machine learning classification | Standalone application [21] |

| DeepSPT | Deep learning framework | Integrated in segmentation module | Temporal behavior segmentation, diffusional fingerprinting | Python package, standalone executable [22] |

| u-track | MATLAB-based tracking suite | MSD calculation and fitting | Robust trajectory reconstruction in crowded environments | MATLAB package [24] |

| BNP-Track 2.0 | Physics-inspired Bayesian framework | Posterior sampling of diffusion parameters | Handles low SNR conditions, quantifies uncertainty | Open source [25] |

| MDAnalysis | Python MD trajectory analysis | MSD for various dimensions | Integrates with Python scientific stack | Python library [26] |

| AMS Trajectory Analysis | Molecular dynamics utilities | MSD for ionic conductivity | Specialized for material science applications | Commercial suite [27] |

Selection Guidelines

Choosing the appropriate MSD analysis tool depends on specific research requirements:

- For biological SPT with heterogeneous motion: DiffusionLab or DeepSPT provide specialized classification capabilities

- For low signal-to-noise conditions: BNP-Track 2.0 offers robust Bayesian inference [25]

- For integration with custom pipelines: MDAnalysis or MDTraj provide programmable interfaces [26]

- For beginner-friendly analysis: DiffusionLab offers graphical interface without coding requirements [21]

Recent benchmarks from the AnDi (Anomalous Diffusion) Challenge indicate that machine learning approaches consistently outperform traditional MSD fitting for classification tasks, particularly for short trajectories and heterogeneous motion patterns [20] [22]. However, MSD analysis remains valuable for its intuitive interpretation and model-based parameter estimation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Essential research reagents and materials for SPT-MSDA studies

| Category | Specific Examples | Function in SPT Studies |

|---|---|---|

| Fluorescent Labels | Organic dyes (Cy3, Alexa Fluor), Quantum dots, Genetically encoded fluoroproteins (Sapphire, GFP) | Particle visualization and tracking; different labels offer trade-offs between brightness, photostability, and size |

| Expression Systems | Constitutive promoters (CMV), Inducible systems (Tet-On), Genetically encoded multimers (GEMs) | Controlled expression of tagged proteins or nanoparticle probes; inducible systems optimize particle density [23] |

| Cell Culture Reagents | Cell lines (U2OS, HEK293), Culture media, Transfection reagents (lipofectamine, PEI) | Cellular environment for SPT experiments; consistent cell health crucial for reproducible diffusion measurements |

| Imaging Buffers | Oxygen scavenging systems, Triplet state quenchers, Antioxidants | Prolong fluorophore longevity and maintain tracking duration; critical for obtaining sufficient trajectory lengths |

| Fixed Samples | Paraformaldehyde, Glutaraldehyde, Mounting media | Sample preservation for control experiments and calibration; enables validation of dynamic measurements |

| Calibration Standards | Fluorescent beads, Fixed labeled samples, DNA origami structures | System calibration and localization error quantification; essential for accurate MSD parameter estimation |

| Software Platforms | DiffusionLab, DeepSPT, u-track, Custom MATLAB/Python scripts | Trajectory reconstruction, MSD calculation, and diffusion analysis; enable quantitative interpretation of raw data [22] [21] [24] |

| (S)-Setastine | (S)-Setastine, MF:C22H28ClNO, MW:357.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Antifungal agent 123 | Antifungal agent 123, MF:C21H20N4O3, MW:376.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

MSD analysis remains a fundamental methodology in single-particle tracking studies, providing a direct link between experimental trajectories and underlying biophysical mechanisms. While traditional MSD fitting continues to offer intuitive model-based parameter estimation, emerging approaches integrate MSD-derived features with machine learning classifiers for enhanced detection of heterogeneous motion states [2] [22]. The ongoing development of specialized computational tools has made sophisticated MSD analysis increasingly accessible to non-specialists, accelerating applications in drug development and biological discovery.

For researchers implementing MSD analysis, careful attention to experimental artifacts—particularly localization error, motion blur, and trajectory length constraints—is essential for accurate parameter estimation [21]. The integration of MSD with complementary analysis methods, including hidden Markov models and machine learning classifiers, represents the current state-of-the-art for extracting maximal information from complex single-particle trajectories [2] [22]. As SPT technologies continue to advance in spatial and temporal resolution, MSD analysis will maintain its critical role in translating trajectory data into biological insight.

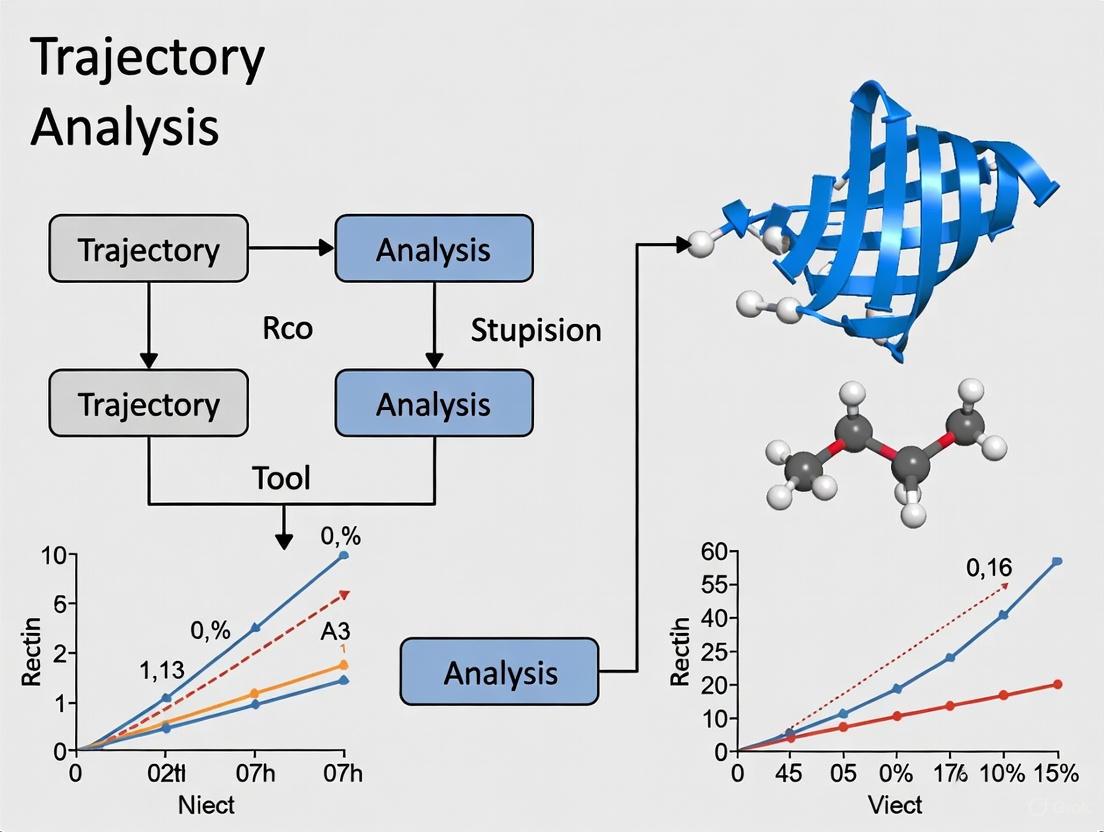

A Practical Toolkit: Software and Methods for Effective MSD Analysis

Mean Squared Displacement (MSD) analysis is a fundamental technique used across various scientific fields, from colloidal studies and biophysics to molecular dynamics simulations, to characterize the motion of particles. The core principle of MSD is to quantify the average squared distance a particle travels over a specific time lag, providing crucial insights into the mode and parameters of its displacement. According to Einstein's theory for particles undergoing Brownian motion, the MSD shows a linear increase with time, described by the relation MSD = 2dDÏ„, where d is the dimensionality, D is the diffusion coefficient, and Ï„ is the lag time [18] [17]. This linear relationship serves as a benchmark for identifying pure diffusive motion. Deviations from this linearity indicate other motion types: a concave, saturating curve suggests confined movement where the particle is bound or impeded, while a convex, faster-than-linear increase indicates directed or transported motion with an active component [17] [2]. The MSD curve is therefore a powerful diagnostic tool, helping researchers determine whether a particle is freely diffusing, transported, or bound.

The analysis of single-particle trajectories has become increasingly important in life sciences, particularly in live-cell single-molecule imaging, where it can reveal heterogeneities and transient interactions of biomolecules [2] [28]. However, traditional MSD analysis faces challenges, including measurement uncertainties, short trajectory lengths, and environmental heterogeneities that can mask the true nature of motion [2]. To address these challenges and automate the analysis, several software platforms have been developed. This application note provides a detailed overview of three popular tools—MDAnalysis, @msdanalyzer, and TRAVIS—summarizing their capabilities, providing protocols for their use, and offering guidance for selecting the appropriate platform for different research scenarios in MSD analysis.

The following sections and tables provide a detailed comparison of the three MSD analysis platforms, highlighting their core features, technical specifications, and analytical capabilities.

Platform Origins and Core Features

MDAnalysis is a Python library specifically designed for the analysis of molecular dynamics (MD) simulations. Its EinsteinMSD class implements the calculation of MSDs, requiring input trajectories to be in an unwrapped convention (also known as "no-jump") to avoid artificial inflation of displacements when particles cross periodic boundaries [18] [29]. It supports both a standard "windowed" algorithm and a faster Fast Fourier Transform (FFT)-based algorithm (fft=True) provided by the tidynamics package, which improves computational scaling from O(N²) to O(N log N) for long trajectories [18] [29].

@msdanalyzer is a MATLAB per-value class designed for the analysis of particle trajectories, commonly from single-particle tracking experiments in fields like biophysics and colloidal studies [17] [30]. It is agnostic to the trajectory source and can handle tracks that do not start simultaneously, have different lengths, contain gaps (missing detections), or have non-uniform time sampling [17] [30]. A key strength is its integrated suite of tools for drift correction, which is a major source of error in experimental particle tracking [17].

TRAVIS (Trajectory Analyzer and Visualizer) is a free, open-source C++ command-line program for analyzing and visualizing trajectories from molecular dynamics and Monte Carlo simulations [31] [32]. It is a comprehensive suite that includes MSD calculation among its vast array of over 60 different analysis functions, such as radial distribution functions (RDF), spatial distribution functions (SDF), and vibrational spectra [31] [32]. Unlike the other two, TRAVIS was primarily designed for bulk analysis of reactive and non-reactive molecular systems.

Table 1: Core Platform Specifications and System Requirements

| Feature | MDAnalysis | @msdanalyzer | TRAVIS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Programming Language | Python | MATLAB | C++ |

| Primary Application Domain | Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations | Single-Particle Tracking (SPT) | Molecular Dynamics/Monte Carlo |

| License | Lesser GNU Public License v2.1+ | N/A (Freeware) | GNU GPL |